Lockdown Zine / July 2020

Special edition Lockdown Zine issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring original writing, photography and illustration produced in the months of UK lockdown, 2020.

Special edition Lockdown Zine issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring original writing, photography and illustration produced in the months of UK lockdown, 2020.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

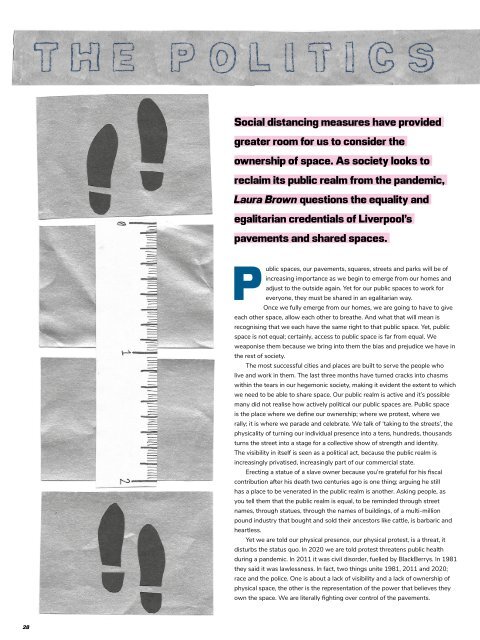

Social distancing measures have provided<br />

greater room for us to consider the<br />

ownership of space. As society looks to<br />

reclaim its public realm from the pandemic,<br />

Laura Brown questions the equality and<br />

egalitarian credentials of Liverpool’s<br />

pavements and shared spaces.<br />

Public spaces, our pavements, squares, streets and parks will be of<br />

increasing importance as we begin to emerge from our homes and<br />

adjust to the outside again. Yet for our public spaces to work for<br />

everyone, they must be shared in an egalitarian way.<br />

Once we fully emerge from our homes, we are going to have to give<br />

each other space, allow each other to breathe. And what that will mean is<br />

recognising that we each have the same right to that public space. Yet, public<br />

space is not equal; certainly, access to public space is far from equal. We<br />

weaponise them because we bring into them the bias and prejudice we have in<br />

the rest of society.<br />

The most successful cities and places are built to serve the people who<br />

live and work in them. The last three months have turned cracks into chasms<br />

within the tears in our hegemonic society, making it evident the extent to which<br />

we need to be able to share space. Our public realm is active and it’s possible<br />

many did not realise how actively political our public spaces are. Public space<br />

is the place where we define our ownership; where we protest, where we<br />

rally; it is where we parade and celebrate. We talk of ‘taking to the streets’, the<br />

physicality of turning our individual presence into a tens, hundreds, thousands<br />

turns the street into a stage for a collective show of strength and identity.<br />

The visibility in itself is seen as a political act, because the public realm is<br />

increasingly privatised, increasingly part of our commercial state.<br />

Erecting a statue of a slave owner because you’re grateful for his fiscal<br />

contribution after his death two centuries ago is one thing; arguing he still<br />

has a place to be venerated in the public realm is another. Asking people, as<br />

you tell them that the public realm is equal, to be reminded through street<br />

names, through statues, through the names of buildings, of a multi-million<br />

pound industry that bought and sold their ancestors like cattle, is barbaric and<br />

heartless.<br />

Yet we are told our physical presence, our physical protest, is a threat, it<br />

disturbs the status quo. In <strong>2020</strong> we are told protest threatens public health<br />

during a pandemic. In 2011 it was civil disorder, fuelled by BlackBerrys. In 1981<br />

they said it was lawlessness. In fact, two things unite 1981, 2011 and <strong>2020</strong>;<br />

race and the police. One is about a lack of visibility and a lack of ownership of<br />

physical space, the other is the representation of the power that believes they<br />

own the space. We are literally fighting over control of the pavements.<br />

28