Michael Leonard extract

Chapter two of Peter Owen's upcoming title, Michael Leonard: Painter and Illustrator

Chapter two of Peter Owen's upcoming title, Michael Leonard: Painter and Illustrator

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Chapter Two<br />

Early Work

Like many artists before him <strong>Michael</strong> spent<br />

the early years of his career searching for an<br />

individual voice and a personal style. Among the<br />

few works that survived the drastic cull when he<br />

moved from Egerton Gardens to his present flat<br />

were some beautiful harbingers of what was to<br />

come. <strong>Michael</strong>’s interest at this time in trying to<br />

create dense and expressive surface textures was<br />

not something that continued into his mature<br />

work. On the other hand, his experiments in<br />

stylization and the abstraction of form were to<br />

pay rich dividends.

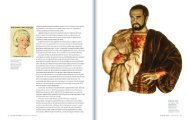

The earliest images to appear on <strong>Michael</strong>’s website were Three Disciples<br />

and Lazarus from 1959. Both were executed in the relatively conventional<br />

combination of India ink, wash and gouache and had a restrained and<br />

delicate palette of silvery blue and grey. Each exhibited the high viewpoint<br />

and flattened space that would later be found in many of <strong>Michael</strong>’s<br />

illustrations. The Three Disciples were arranged in an arc with powerful<br />

diagonals created by the dark staves on which the disciples were leaning. The<br />

image of Lazarus was dominated by a spiralling winding sheet that in its wild<br />

gyrations anticipated the trailing kite tail in Flying a Kite: Brompton Oratory<br />

and the exploding wrapping paper of Charlie’s Parcel and which led eventually<br />

to Afternoon of the Kites. For these figures <strong>Michael</strong> used dancers from a West<br />

End show as models. He said he liked working with them because they were<br />

passive and biddable. ‘When I am in director’s mode I can be formidable and<br />

have to be obeyed.’<br />

In Three Disciples and Lazarus, despite <strong>Michael</strong>’s growing interest in design,<br />

the figures were relatively naturalistic and remained largely untouched<br />

by the drive towards stylization. This came into play more powerfully in<br />

the illustrations for Homer’s Odyssey. In these he was aiming for something<br />

more primitive and archaic. The extreme simplification of musculature was<br />

borrowed, appropriately enough, from ancient Greek vases. We see him trying<br />

out two different approaches for two versions of Ajax with the Dead Achilles,<br />

one more radically simplified than the other. His depiction of the climactic<br />

Battle in the Hall, in which Ulysses returns to slaughter the suitors of his wife<br />

Penelope, was primitive, brutal and violent and his warriors both stylized<br />

and exaggeratedly masculine.<br />

At this point in his career <strong>Michael</strong> was obsessed with Classical Greece.<br />

We can see this in his design for a plate with a galloping centaur and attendant<br />

satyr and in his three lino-cuts of Jason, Medea and Hercules which were<br />

created separately and then united as a triptych. It is surprising perhaps there<br />

weren’t more of these, as the technique is admirably well suited to this kind of<br />

primitivism, but at this period <strong>Michael</strong> was trying out every possible medium.<br />

Anatomical exaggeration was taken to the extreme in the two versions of The<br />

Victor, one executed on a reddish background and the other – which <strong>Michael</strong><br />

feels is the more successful of the two – on gold. In both cases the contours of<br />

the figures were outlined in white rather than black.<br />

This experimental side of <strong>Michael</strong>’s art is very much in evidence in works<br />

based on mythological themes and painted on hardboard panels, using highly<br />

unconventional mixed-media techniques. In the brooding Jocasta and Oedipus,<br />

which stylistically remains a one-off experiment, he describes himself as<br />

‘trying to find his way into a style’.<br />

Three Disciples, 1959,<br />

gouache on card<br />

chapter two: early work 29

<strong>Michael</strong> relishes<br />

the challenges that<br />

illustration offers and<br />

the stretching of his<br />

powers of invention<br />

Icarus and the Minotaur are mythological figures with whom <strong>Michael</strong><br />

strongly identifies. He was dissatisfied with his first version of the Minotaur,<br />

The Minotaur in the Maze, finding the body too slender and the head too small,<br />

although he liked it enough to retain it when destroying many other works of<br />

this period. He describes his Minotaur as a fugitive fleeing from an imaginary<br />

assailant. It is painted coarsely on cardboard using emulsion house paint<br />

with India ink rubbed into its textured surface. The subject engaged <strong>Michael</strong><br />

sufficiently to inspire a poem to go with the image. It had several verses; this<br />

is the first:<br />

Within the antrum of a dark estate<br />

Beholden to the screw-thread of the way<br />

He walks attended by a surrogate<br />

Of one ripped howling out of Parsiphae.<br />

In one image <strong>Michael</strong> has Icarus flying across the white disk of the sun.<br />

In another Icarus is already beginning to disintegrate into bone and ashes.<br />

This was achieved by pressing strips of cloth into wet emulsion on hardboard,<br />

waiting until it was dry, then rubbing India ink into the textured grooves.<br />

A related technique that he used at this time was to press Kleenex tissues<br />

into Unibond glue. We see this in the highly abstracted image of three women’s<br />

faces (The Women). The faces are given geometric form rather in the style of a<br />

well-known sculptor of the day, Lynn Chadwick. <strong>Michael</strong> uses the term tachiste<br />

in relation to these images, explaining that they embody the perhaps fanciful<br />

idea that even blind people could experience them through touch. He used<br />

similar methods in three portraits in varying techniques of the Canadian<br />

Shakespearian actor Leo Ciceri, who famously made a career out of playing<br />

kings and princes.<br />

<strong>Michael</strong> was particularly happy with the portrait he made of his close friend<br />

Desmond Heeley in which abstract image and likeness were perfectly aligned,<br />

and with the intensity of the subject’s gaze magnificently caught.<br />

The tendency towards abstraction reached a conclusion in a triptych of<br />

hieratic heads, The King, The Queen and The Prince and some nudes based on the<br />

photographs of Eadweard Muybridge. The Queen was perhaps the most austere<br />

of these images. The Prince and The King were enriched with heavily stylized<br />

and textured crowns that doubled as the battlements of ancient citadels.<br />

The Eadweard Muybridge photographs of human and animal locomotion<br />

were reissued by Dover Publications in 1955 in time to provide useful source<br />

material for some of <strong>Michael</strong>’s early work. We have two scenes of textured and<br />

stylized wrestlers and one of the back of a male nude. All were derived from<br />

28 michael leonard painter and illustrator

Muybridge’s photographs. These are <strong>Michael</strong>’s most abstract works, and at first<br />

glance and without knowledge of the photographic source material they could<br />

easily be taken for fully abstract works.<br />

Throughout the 1960s <strong>Michael</strong> continued to experiment endlessly until<br />

a moment of epiphany occurred, in which his portrait of Roger Coleman<br />

sent him off in a different direction and he decided to abandon surface<br />

textures altogether.<br />

The Minotaur in the<br />

Maze, 1960s, India<br />

ink and house paint,<br />

66.8 × 50.8 cm<br />

chap ter two e arly work 29

Zipkin, Jerome, 100<br />

Zydower, Astrid, 7, 13, 83–4, 85,<br />

102, 178<br />

30 michael leonard painter and illus tr ator