Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

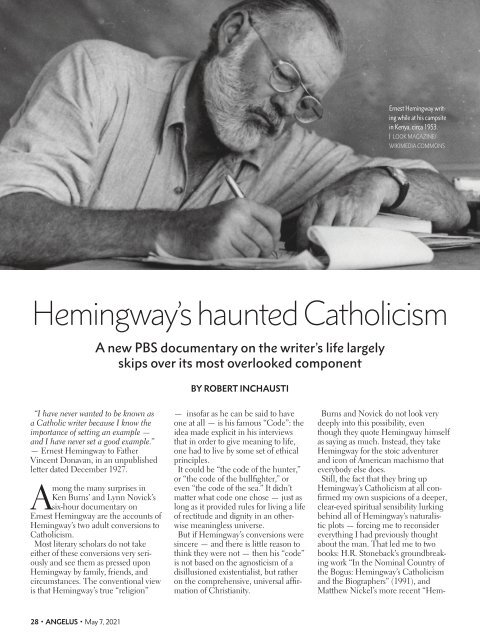

Ernest Hemingway writing<br />

while at his campsite<br />

in Kenya, circa 1953.<br />

| LOOK MAGAZINE/<br />

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS<br />

Hemingway’s haunted Catholicism<br />

A new PBS documentary on the writer’s life largely<br />

skips over its most overlooked component<br />

BY ROBERT INCHAUSTI<br />

“I have never wanted to be known as<br />

a Catholic writer because I know the<br />

importance of setting an example —<br />

and I have never set a good example.”<br />

— Ernest Hemingway to Father<br />

Vincent Donavan, in an unpublished<br />

letter dated December 1927.<br />

Among the many surprises in<br />

Ken Burns’ and Lynn <strong>No</strong>vick’s<br />

six-hour documentary on<br />

Ernest Hemingway are the accounts of<br />

Hemingway’s two adult conversions to<br />

Catholicism.<br />

Most literary scholars do not take<br />

either of these conversions very seriously<br />

and see them as pressed upon<br />

Hemingway by family, friends, and<br />

circumstances. The conventional view<br />

is that Hemingway’s true “religion”<br />

— insofar as he can be said to have<br />

one at all — is his famous “Code”: the<br />

idea made explicit in his interviews<br />

that in order to give meaning to life,<br />

one had to live by some set of ethical<br />

principles.<br />

It could be “the code of the hunter,”<br />

or “the code of the bullfighter,” or<br />

even “the code of the sea.” It didn’t<br />

matter what code one chose — just as<br />

long as it provided rules for living a life<br />

of rectitude and dignity in an otherwise<br />

meaningless universe.<br />

But if Hemingway’s conversions were<br />

sincere — and there is little reason to<br />

think they were not — then his “code”<br />

is not based on the agnosticism of a<br />

disillusioned existentialist, but rather<br />

on the comprehensive, universal affirmation<br />

of Christianity.<br />

Burns and <strong>No</strong>vick do not look very<br />

deeply into this possibility, even<br />

though they quote Hemingway himself<br />

as saying as much. Instead, they take<br />

Hemingway for the stoic adventurer<br />

and icon of American machismo that<br />

everybody else does.<br />

Still, the fact that they bring up<br />

Hemingway’s Catholicism at all confirmed<br />

my own suspicions of a deeper,<br />

clear-eyed spiritual sensibility lurking<br />

behind all of Hemingway’s naturalistic<br />

plots — forcing me to reconsider<br />

everything I had previously thought<br />

about the man. That led me to two<br />

books: H.R. Stoneback’s groundbreaking<br />

work “In the <strong>No</strong>minal Country of<br />

the Bogus: Hemingway’s Catholicism<br />

and the Biographers” (1991), and<br />

Matthew Nickel’s more recent “Hem-<br />

28 • ANGELUS • <strong>May</strong> 7, <strong>2021</strong>