You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

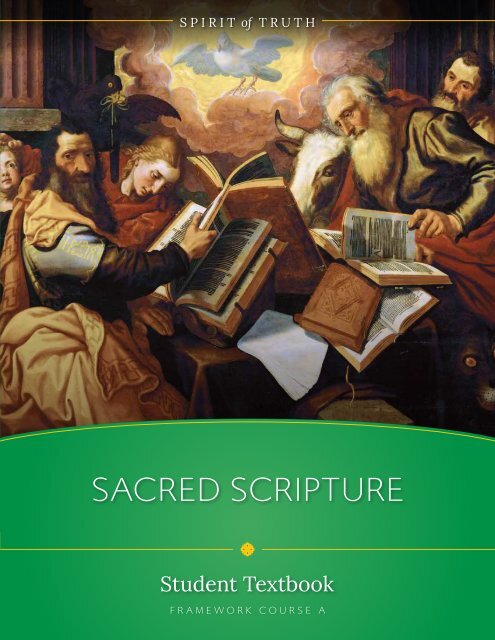

SPIRIT of TRUTH<br />

SACRED SCRIPTURE<br />

Student Textbook<br />

FRAMEWORK COURSE A

SPIRIT of TRUTH<br />

SACRED<br />

SCRIPTURE<br />

Student Textbook<br />

FRAMEWORK COURSE A

About Sophia Institute for Teachers<br />

Sophia Institute for Teachers was launched in 2013 by Sophia Institute to renew and rebuild Catholic<br />

culture through service to Catholic education. With the goal of nurturing the spiritual, moral, and cultural<br />

life of souls, and an abiding respect for the role and work of teachers, we strive to provide materials and<br />

programs that are at once enlightening to the mind and ennobling to the heart; faithful and complete, as<br />

well as useful and practical.<br />

Sophia Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded in 1983.<br />

Excerpts from the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition, © 1994,<br />

1997, 2000 by Libreria Editrice Vaticana–United States Catholic Conference, Washington, D.C. All rights<br />

reserved.<br />

Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986,<br />

1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C., and are used by permission of the copyright<br />

owner. All rights reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without<br />

permission in writing from the copyright owner.<br />

Unless otherwise noted, images in this book are in the public domain. We thank all copyright holders for<br />

their permission to use their material in this publication. Every attempt was made to secure permission to<br />

repr<strong>int</strong> any protected material in this publication. Any omissions or errors were un<strong>int</strong>entional, and we will<br />

make adjustments immediately upon request.<br />

© 2020 by Sophia Institute for Teachers.<br />

All rights reserved. Portions of this publication may be photocopied and/or reproduced within the<br />

schools which purchased it for educational use only. Written permission must be secured from the<br />

publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book outside the school which purchased it in any medium.<br />

This text is pending review for conformity by the Subcommittee on the Catechism, United States<br />

Conference of Catholic Bishops.<br />

Pr<strong>int</strong>ed in the United States of America<br />

Design by Perceptions Design Studio<br />

Cover image: The Four Evangelists, Pieter Aertsen (1560–1565).<br />

Art History Museum, Vienne / Alamy stock photo.<br />

Spirit of Truth: Sacred Scripture Student Textbook<br />

ISBN: 978-1-622827-800<br />

First pr<strong>int</strong>ing

Contents<br />

Acknowledgments................................................................................................................................. ii<br />

Unit 1: Divine Revelation: God Speaks to Us .............................................................2<br />

Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission .............................................................................4<br />

Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred Scripture ...........................................................20<br />

Chapter 3: The Interpretation and Life of Sacred Scripture in the Church.........................................36<br />

Unit 2: The Early World and the Patriarchs................................................................54<br />

Chapter 4: Creation and the Fall........................................................................................................56<br />

Chapter 5: Cain and Abel to the Tower of Babel ................................................................................78<br />

Chapter 6: The Patriarchs .................................................................................................................94<br />

Unit 3: God’s People Become a Nation.................................................................... 112<br />

Chapter 7: The Exodus..................................................................................................................... 114<br />

Chapter 8: Joshua, Judges, and Ruth..............................................................................................136<br />

Unit 4: Rise and Fall of the Kingdoms......................................................................156<br />

Chapter 9: Samuel, Saul, and David ...............................................................................................158<br />

Chapter 10: Solomon and the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah .........................................................178<br />

Chapter 11: Exile, Return, and Revolt .............................................................................................196<br />

Unit 5: Wisdom and Prophecy...................................................................................212<br />

Chapter 12: The Wisdom Books ......................................................................................................214<br />

Chapter 13: The Prophets ...............................................................................................................232<br />

Unit 6: The Gospels and the Life of Christ...............................................................252<br />

Chapter 14: The Gospels ................................................................................................................254<br />

Chapter 15: The Early Life of Christ ................................................................................................276<br />

Chapter 16: Jesus’ Public Ministry ...................................................................................................292<br />

Chapter 17: The Paschal Mystery ...................................................................................................314<br />

Unit 7: The Early Church............................................................................................332<br />

Chapter 18: The Book of Acts...........................................................................................................334<br />

Chapter 19: The Epistles..................................................................................................................354<br />

Chapter 20: The Book of Revelation ...............................................................................................376<br />

Glossary............................................................................................................................................394<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers<br />

i

Acknowledgments<br />

Spirit of Truth High School Edition follows the basic scope and sequence of the Doctrinal Elements of<br />

a Curriculum Framework set forth by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. This course<br />

corresponds to Elective Course A: Sacred Scripture.<br />

Authors<br />

Joseph Breslin<br />

Courtney Brown<br />

Emily Stimpson Chapman<br />

Michael Gutzwiller<br />

Emma Hegarty<br />

Anna Maria Mendell<br />

Victoria Nelson<br />

Aidan O’Connor<br />

Ethan O’Connor<br />

Catherine Petrie<br />

Amy Roberts<br />

Ryan Schwartz<br />

Andrew Swafford<br />

Michael Verlander<br />

Janet Wigoff<br />

Editors<br />

Veronica Burchard<br />

Emily Stimpson Chapman<br />

Mike Gutzwiller<br />

Anna Maria Mendell<br />

Ethan O’Connor<br />

Catechetical Consultant<br />

Michel Therrien, S.T.L., S.T.D.<br />

Copyeditors and Proofreaders<br />

Laura Bement<br />

Janelle Gergen<br />

Anna Maria Mendell<br />

Design<br />

Perceptions Design Studio<br />

Amherst, NH<br />

ii<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

A special thanks<br />

In grateful recognition of Lawrence Joseph<br />

and Lynn Marie Blanford.<br />

The chapter readings in this textbook were developed in partnership<br />

by Sophia Institute and Emmaus Road Publishing, an initiative of the<br />

St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology.<br />

The St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology is a non-profit research<br />

and educational institute that promotes life-transforming Scripture<br />

study in the Catholic tradition. The Center serves clergy and laity,<br />

students and scholars, with research and study tools — from books<br />

and publications to multimedia and online programming.<br />

Sophia Institute is particularly grateful to Dr. Scott Hahn, Ken<br />

Baldwin, and Chris Erickson for their generosity and contributions to<br />

this textbook. We value their friendship and are grateful for all they<br />

do to help people encounter Christ through Scripture and engage in<br />

the work of catechesis and evangelization.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers<br />

1

UNIT 1<br />

Divine Revelation:<br />

God Speaks to Us

Unit 1<br />

3<br />

Every book, in some way, has the power to change us. Some<br />

are inspiring, others teach us. Some even harm us. But no<br />

book can change us as much as Sacred Scripture.<br />

St. Paul explained, “All Scripture is inspired by God and is<br />

useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training<br />

in righteousness, so that one who belongs to God may be competent,<br />

equipped for every good work” (2 Tim. 3:16–17).<br />

There are, of course, plenty of other books out there that<br />

will teach us, correct us, and train us in “righteousness”—that is,<br />

help us to become good and just people. But not one of those<br />

other books will do it so well as Sacred Scripture, because none<br />

of them are the inspired Word of God. Moreover, none of those<br />

books brings us <strong>int</strong>o a direct, personal encounter with the Word<br />

of God made flesh: Jesus Christ.<br />

Nothing else we ever read will be as important as Sacred<br />

Scripture. For this reason, it is so important that we read it correctly.<br />

The Holy Bible is not like other books. If we just pick it up<br />

and try reading it cover to cover, from beginning to end, it is easy<br />

to get confused, lose the thread of the biblical “plot,” or even<br />

miss the po<strong>int</strong> of it all entirely.<br />

This unit will give you the tools that will enable you to see the<br />

po<strong>int</strong>. Some of the most fundamental questions about the Holy<br />

Bible will be answered: What is Scripture? Why do we have the<br />

Bible? How is it inspired by God? Why should we read it? How<br />

should we <strong>int</strong>erpret it? Why does it matter to me?<br />

As the answers to these questions emerge, you will learn to<br />

navigate Scripture with greater confidence and knowledge. You<br />

will also see the scope of Salvation History—God’s saving work<br />

in time—and understand your place in that history. Most importantly,<br />

you will have the opportunity to grow closer to Jesus by<br />

spending time prayerfully contemplating God’s Word.<br />

In This Unit<br />

■ Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and its Transmission<br />

■ Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred<br />

Scripture<br />

■ Chapter 3: The Interpretation and Life of Sacred<br />

Scripture in the Church

Chapter 1<br />

Divine Revelation<br />

and Its Transmission

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

5<br />

Chapter Overview<br />

God, as a loving Father and Creator, wants all of humanity to know Him; He desires to be<br />

in relationship with every human person. Revelation is God’s way of showing Himself to<br />

us through the natural world and divine action. We can come to know truths about God by<br />

observing the magnificence and beauty of the world, but that is only the beginning. All of<br />

Salvation History shares the true story of God gradually revealing Himself and His plan for<br />

humanity’s goodness over time. Ultimately, God chose to become human so we could see<br />

His love and mercy firsthand in His Cross and Resurrection. Following Christ’s Resurrection,<br />

God has continued to reveal His love for humanity through His disciples. Jesus instructed<br />

the Apostles to continue His work by proclaiming the Good News to all, and we can<br />

find these truths of the Faith in Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition.<br />

In this chapter you will learn that…<br />

■ Divine revelation is God’s communication of Himself to us by which He reveals the mystery of His divine plan.<br />

■ Human beings are made members of God’s family through covenants, which are sacred and permanent<br />

bonds of family relationship.<br />

■ There are six major covenants in Salvation History, and each one brings mankind <strong>int</strong>o a more <strong>int</strong>imate and<br />

loving relationship with God.<br />

■ The two sources of divine revelation are Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture, which share a common<br />

source, God Himself, and together form one Deposit of Faith.<br />

■ The Deposit of Faith is <strong>int</strong>erpreted by the Magisterium, who guards and protects the truths of the Faith and<br />

cannot err in matters of faith and morals.<br />

Bible Basics<br />

Connections to the Catechism<br />

I praise you because you remember me in everything and hold<br />

fast to the traditions, just as I handed them on to you.<br />

1 CORINTHIANS 11:2<br />

“Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them<br />

in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the holy Spirit,<br />

teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And<br />

behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age.”<br />

MATTHEW 28:19–20<br />

CCC 50 (pgs. 6, 7)<br />

CCC 51 (pg. 7)<br />

CCC 52 (pg. 9)<br />

CCC 53 (pg. 7)<br />

CCC 65 (pg. 10)<br />

CCC 77 (pg. 11)<br />

CCC 78 (pg. 13)<br />

CCC 80 (pg. 13)<br />

CCC 81 (pg. 13)<br />

CCC 82 (pg. 13)<br />

CCC 85 (pg. 14)<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

6 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Natural Revelation (n.):<br />

God’s communication of<br />

Himself to us through the<br />

created order.<br />

God first uses the natural<br />

world as a way to reveal<br />

Himself to us.<br />

The Revelation of God<br />

The natural world bears the mark of its Creator, much like a book is written<br />

in the voice of its author or a pa<strong>int</strong>ing displays the brushstrokes of its<br />

artist. Signs of God’s goodness and love, His power and majesty, and His<br />

providence and care are everywhere. By simply contemplating the world<br />

around us, we can come to know a great deal about God; evidence of who<br />

He is and how He loves us is in every sunset and mounta<strong>int</strong>op, as well as<br />

every flower and grain of wheat. The Catechism of the Catholic Church<br />

tells us, “By natural reason man can know God with certa<strong>int</strong>y, on the<br />

basis of his works” (50). That is to say, just as we can read a book and<br />

know with certa<strong>int</strong>y that it was written by an author or look at a pa<strong>int</strong>ing<br />

and know without a doubt that it was composed by an artist, we can look<br />

at the world around us and know its Creator, God Himself. Further, just as<br />

we can know something about an author or artist by their works, so too can<br />

we know something about God by what He has made. We call this most<br />

basic form of revelation natural revelation.<br />

While the natural world reveals much about God to us, it does not reveal<br />

everything. There are some truths about who God is and what His plan<br />

is for us that we cannot perceive by our own power. Nature is not enough.<br />

For some truths, more is needed. Again, think of a book and its author:<br />

Paradise landscape with the Creation of the animals by Workshop of Jan Brueghel the Younger (17th century).<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

7<br />

while we can know for certain that the book was indeed written by an author<br />

and is not a collection of words that randomly assembled itself <strong>int</strong>o a book,<br />

and we can even gain insight <strong>int</strong>o the author herself and what she wanted<br />

to communicate by her work, we cannot know many other things about her.<br />

We cannot know her motivation for writing, her influences, her likes and<br />

dislikes, and especially, who she is beyond what she has made. In order to<br />

know these things about the author, we would have to meet her, and she<br />

would have to reveal these things about herself.<br />

The same is true regarding God. The Catechism continues, “there is<br />

another order of knowledge, which man cannot possibly arrive at by<br />

his own powers: the order of divine Revelation. Through an utterly<br />

free decision, God has revealed himself and given himself to man. … It<br />

pleased God, in his goodness and wisdom, to reveal himself and to<br />

make known the mystery of his will” (50–51). In order for us to know<br />

Him more fully, He had to reveal Himself to us. We call God’s revelation of<br />

Himself divine revelation. Through divine revelation, God makes Himself<br />

known and reveals His plan for us.<br />

God did not simply reveal all of Himself and His divine plan at once,<br />

however, and expect humanity immediately to see and understand everything.<br />

God, who is the divine teacher, prepared us to receive the fullness<br />

of His self-revelation gradually and in stages, and in words and deeds:<br />

“The divine plan of Revelation is realized simultaneously ‘by deeds<br />

and words which are <strong>int</strong>rinsically bound up with each other’ and shed<br />

light on each another. It involves a specific divine pedagogy: God<br />

communicates himself to man gradually. He prepares him to welcome<br />

by stages the supernatural Revelation that is to culminate in the person<br />

and mission of the incarnate Word, Jesus Christ” (CCC 53). The<br />

realization of God’s divine pedagogy, or teaching method, in human history<br />

is called Salvation History.<br />

Covenant<br />

Salvation History is the true story of God’s love and mercy revealed to<br />

us throughout human history, culminating in the Incarnation of His Son,<br />

Jesus Christ, and in His Death and Resurrection, which won for us salvation<br />

from sin and death. Salvation History is, in a sense, the “plot” of<br />

Sacred Scripture.<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Divine Revelation (n.):<br />

God’s communication<br />

of Himself, by which He<br />

makes known the mystery<br />

of His divine plan by<br />

deeds and words over<br />

time, and most fully by<br />

sending His Son, Jesus<br />

Christ.<br />

Divine Pedagogy (n.):<br />

The teaching method<br />

of God, who is the<br />

divine teacher, by which<br />

He revealed Himself<br />

gradually and in stages<br />

and by words and deeds.<br />

Sacred Scripture (n.):<br />

The written record of<br />

God’s revelation of<br />

Himself contained in the<br />

Old and New Testaments.<br />

It was composed by<br />

human authors inspired<br />

by the Holy Spirit. The<br />

Bible. The Word of God.<br />

Covenant (n.): A sacred<br />

permanent bond of<br />

family relationship. God<br />

entered <strong>int</strong>o a series<br />

of covenants with His<br />

People throughout<br />

Salvation History to invite<br />

us to be part of His divine<br />

family and to prepare us<br />

gradually and in stages,<br />

and in words and deeds,<br />

to receive the gift of<br />

salvation.<br />

This plot unfolds through a series of covenants with mankind. A covenant<br />

is a sacred and permanent bond of kinship, or family relationship,<br />

entered <strong>int</strong>o by two or more people. More than a simple contract involving<br />

goods and services, a covenant involves a gift of self between persons.<br />

The two human covenants we are most familiar with are marriage and<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

8 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Mediator (n.): The<br />

person whom God chose<br />

to represent all those<br />

entering <strong>int</strong>o a covenant<br />

with Him. Adam, Noah,<br />

Abraham, Moses, David,<br />

and Jesus Christ are<br />

the mediators of the<br />

six primary covenants<br />

throughout Salvation<br />

History.<br />

Covenantal Sign (n.): An<br />

external representation<br />

of the <strong>int</strong>erior reality<br />

occurring within a<br />

covenant. Every covenant<br />

included a sign taken<br />

from human experience<br />

to represent the depth<br />

of God’s love and mercy<br />

present at the heart of the<br />

covenant.<br />

First, God<br />

entered each<br />

covenant with<br />

a mediator, or<br />

human person<br />

who stood in for<br />

everyone else<br />

who was part of<br />

the covenant.<br />

adoption. Through the marriage covenant, one man and one woman who<br />

are members of different families become united in a new family. Their<br />

union is permanent and requires the total self-gift of each person. Adoption,<br />

a supremely loving response to a tragedy such as death or abandonment,<br />

makes a child a member of a family <strong>int</strong>o which they were not born. In a<br />

similar way, human beings are made members of God’s family through<br />

covenants. We are adopted <strong>int</strong>o the family of God — His supremely loving<br />

response to the tragedy of our sin.<br />

Generally speaking, covenants were quite common in ancient societies.<br />

They were typically made with a solemn oath and sealed through a sacred<br />

ritual and meal. Likewise, covenants always came with terms (often called<br />

the covenant law). People would enter <strong>int</strong>o covenant with one another, but<br />

only under certain conditions. In biblical times, if those conditions were not<br />

met, a grave consequence (death, for example) followed. If the conditions<br />

were fulfilled, blessing followed.<br />

An Overview of Salvation History<br />

There are six major covenants God entered <strong>int</strong>o with His people throughout<br />

Salvation History. The stories of five of these covenants are found in<br />

the Old Testament, and the story of the sixth and final covenant is found<br />

in the New Testament. The covenants have a number of common characteristics<br />

we can identify to help us better understand each one. First, God<br />

entered each covenant with a mediator, or human person who stood in<br />

for everyone else who was part of the covenant. Second, each covenant<br />

contained a covenantal sign, or outward representation of God’s love for<br />

His people at the heart of each covenant. Third, each covenant contained<br />

a promise made by God to His people. Fourth, and finally, each covenant<br />

grew progressively larger in the number of people that were incorporated<br />

<strong>int</strong>o God’s family through it. These characteristics will help guide our deeper<br />

discussion of each covenant of Salvation History.<br />

God first revealed Himself to Adam (and Eve), making a covenant with<br />

him and all of creation, with the Sabbath as a sign. After the Fall of Man,<br />

God promised to send a Savior to redeem the human race from sin. God<br />

continued His self-revelation with Noah, establishing a covenant through<br />

him, in which He promised never again to destroy the human race by flood,<br />

with the rainbow as a sign of His promise. Next, God entered a covenant<br />

with Abraham, promising him the Promised Land and great blessings to<br />

the world through Abraham’s descendants. The sign of this covenant was<br />

circumcision. Centuries later, God freed His Chosen People from slavery in<br />

Egypt through Moses and established them as a nation in a new covenant<br />

with Him at Mt. Sinai. He promised them, again, the Promised Land and<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

9<br />

made the sign of this covenant the Law. Then, God established the final<br />

covenant of the Old Testament with David, ruler of the Kingdom of Israel,<br />

promising that his descendants would sit upon an everlasting throne.<br />

Finally, in the fullness of time, God established a New Covenant, in<br />

which He fulfilled all of the promises of the Old Covenant and saved His<br />

people from sin. The Incarnation of His Son, Jesus Christ, marked the<br />

definitive stage of divine revelation: the Word became flesh. In Jesus, God<br />

has most perfectly shown Himself to us. As Jesus Himself tells us, through<br />

Him, we know God: “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John<br />

14:9). Likewise, through Jesus, we have access to God and can share<br />

in His divine life as His adopted sons and daughters: “God … wants to<br />

communicate his own divine life to the men he freely created, in order<br />

to adopt them as his sons in his only-begotten Son. By revealing<br />

himself God wishes to make them capable of responding to him,<br />

and of knowing him and of loving him far beyond their own natural<br />

capacity” (CCC 52). Through Jesus’ physical presence among us, His<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Incarnation (n.): The<br />

fact that the Son of God<br />

assumed human nature<br />

and became man in<br />

order to accomplish our<br />

salvation. Jesus Christ,<br />

the Son of God, the<br />

second Person of the<br />

Trinity, is both true God<br />

and true man.<br />

Adoration of the Shepherds by Gerard van Honthorst (ca. 1622).<br />

God has most perfectly<br />

revealed Himself through<br />

the Incarnation of His Son,<br />

Jesus Christ.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

10 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Paschal Mystery<br />

(n.): Christ’s work of<br />

redemption accomplished<br />

by His Passion, Death,<br />

Resurrection, and<br />

Ascension.<br />

Great Commission<br />

(n.): The final words of<br />

Christ to His Apostles<br />

before His Ascension<br />

<strong>int</strong>o Heaven, found in<br />

Matthew 28:18–20. In<br />

these words, Christ gave<br />

His Apostles, and thereby<br />

the Church, the mission of<br />

evangelization — making<br />

disciples of all the nations.<br />

Gospel (n.): One of the<br />

first four books of the New<br />

Testament. They are the<br />

heart of the Scriptures<br />

and proclaim the Good<br />

News of salvation won for<br />

us by the Passion, Death,<br />

and Resurrection of Jesus<br />

Christ. The Gospels are<br />

our primary source of<br />

knowledge of life of Jesus<br />

Christ. The word “Gospel”<br />

means “Good News.”<br />

Martyr (n.): A person<br />

who is killed for bearing<br />

witness to his faith.<br />

words and deeds, His signs and wonders, and, above all, through His<br />

Paschal Mystery — His suffering, Death, Resurrection, Ascension — and<br />

sending of the Holy Spirit, Jesus made God known to the world. Jesus, the<br />

Word of God, is God’s final word on Himself. “In him he has said everything;<br />

there will be no other word than this one” (CCC 65).<br />

As God’s relationship with His people progressed, more and more people<br />

were invited <strong>int</strong>o His covenant family. From the original couple (Adam<br />

and Eve), to a faithful family (Noah and his wife, and his sons and their<br />

wives), to a holy tribe (Abraham and his tribe), to a chosen nation (Moses<br />

and the Israelites), to a royal kingdom (David and the Kingdom of Israel),<br />

and culminating in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, God drew<br />

the entire human race to Himself. The goal of God’s whole plan of revelation<br />

— the end of the whole sweep of Salvation History — was to bring us<br />

<strong>int</strong>o the closest, most loving, most <strong>int</strong>imate relationship possible with Him.<br />

In other words, Salvation History, in its deepest essence, is a love story,<br />

one between God and all of us, His Chosen People.<br />

The Transmission of Divine Revelation<br />

When the Son of God assumed a human nature, He made the truth of who He<br />

was known through both His words and deeds. He told parables, preached<br />

sermons on mounta<strong>int</strong>ops, and answered the questions of Jewish leaders.<br />

He also multiplied loaves and fish, healed the sick, and even resurrected the<br />

dead. Then, after His own Resurrection, shortly before He returned to the<br />

Father in Heaven and sent the Holy Spirit to us, He told His Apostles to do as<br />

he had done: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing<br />

them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the holy Spirit,<br />

teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold,<br />

I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Matt. 28:19–20).<br />

This final command of the Lord before His Ascension <strong>int</strong>o Heaven is<br />

known as the Great Commission. After Pentecost, the Apostles, filled with<br />

the Holy Spirit, responded to this commission by transmitting the Gospel in<br />

three ways: orally, through their example, and in writing.<br />

So, as Jesus did, they preached the Gospel: they proclaimed the Good<br />

News of God’s love for us in Jesus Christ. Also, like Jesus, what they<br />

preached was accompanied by various deeds: administering Baptisms,<br />

hearing confessions, celebrating the Eucharist, and performing miracles,<br />

such as healing the sick and raising the dead. For nearly all of the Apostles<br />

those deeds also included martyrdom (CCC 2473); the Apostles bore witness<br />

to the truth of who Jesus was through their willingness to sacrifice<br />

their lives for that truth. Finally, to ensure that what they had received was<br />

handed down faithfully to future generations, the Apostles fulfilled Jesus’<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

11<br />

commission by writing it down “under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit” (Dei<br />

Verbum 7). These are the writings that make up the New Testament.<br />

It is important to note that the portion of the apostolic preaching that<br />

was written down did not exhaust the content of the Gospel, nor did it render<br />

their preaching obsolete. Rather, the written word complemented the<br />

preached Gospel, allowing the Gospel to be transmitted faithfully as the<br />

first generation passed and the Church spread throughout the world.<br />

Writing down what they preached was not the only way the Apostles<br />

ensured their work would continue after they were gone. They also appo<strong>int</strong>ed<br />

successors — ano<strong>int</strong>ing and laying hands on men — and transferred to<br />

them the authority which had been given to them by Christ Himself. These<br />

successors, or bishops, would serve the Body of Christ as the original<br />

Apostles did and with the same authority: through teaching, preaching, administering<br />

the Sacraments, and ensuring that the needs of the Church’s<br />

most vulnerable members — the poor, the sick, widows, orphans, the unborn,<br />

and the elderly — were met. The successors to the Apostles in turn<br />

had the power to ordain successors of their own, so the Gospel could be<br />

proclaimed in word and deed to every new generation. This process, which<br />

we call apostolic succession, was explained by the early Church Father<br />

St. Irenaeus, who wrote: “In order that the full and living Gospel might<br />

always be preserved in the Church the apostles left bishops as their<br />

successors. They gave them their own position of teaching authority”<br />

(CCC 77).<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Bishops (n.): A successor<br />

to the Apostles who has<br />

received the fullness of<br />

the Sacrament of Holy<br />

Orders. He is the leader<br />

of a particular church, or<br />

diocese, entrusted to him.<br />

Apostolic Succession<br />

(n.): The handing on<br />

of apostolic preaching<br />

and authority from<br />

the Apostles to their<br />

successors, the bishops,<br />

through the laying on of<br />

hands as a permanent<br />

office in the Church.<br />

Christ ordained Peter<br />

and the Apostles as the<br />

first bishops so that they<br />

could transmit the Gospel<br />

through speech, by<br />

example, and in writing.<br />

The Sacrament of Ordination (Christ presenting the Keys to Sa<strong>int</strong> Peter) by Nicolas Poussin (ca. 1636–1640).<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

12 Sacred Scripture<br />

Lives of Faith<br />

St. Paul<br />

Sacred Scripture reveals that God uses the most<br />

unlikely people to accomplish His will. In the case<br />

of St. Paul the Apostle, God made a hated enemy<br />

of the early Christian community <strong>int</strong>o its greatest<br />

evangelist.<br />

Paul, a faithful Jewish man and scholar, was<br />

convinced that the Church was a perversion of his<br />

tradition. He despised Christians and was zealous<br />

in his persecution of them. While heading toward<br />

Damascus, planning to put any Christians<br />

he might find in chains, Paul experienced a vision<br />

of the risen Christ, who said to him, “Why are you<br />

persecuting me?” When Paul asked who was<br />

speaking to him, the voice replied, “I am Jesus,<br />

whom you are persecuting” (Acts 9:4–5). This encounter<br />

with Christ instantly converted Paul and<br />

set him on a path of healing, reconciliation, and<br />

tireless evangelization.<br />

Paul was a master at evangelizing. He could<br />

turn any circumstance <strong>int</strong>o an opportunity for<br />

sharing the Gospel message, and he often had<br />

to think on his feet. He proclaimed Jesus among<br />

both Jews and Gentiles alike. The Gentiles were<br />

pagans, and their way of thinking was radically<br />

different from that of the Jews and the early<br />

Christians. They believed in many gods, and<br />

they did not have what we know now as the Old<br />

Testament to serve as a foundation for their understanding<br />

of God. How could Paul proclaim<br />

the God of Israel and His Son, Jesus, to people<br />

who did not have the necessary context to understand<br />

it?<br />

One story perfectly illustrates Paul’s ability to<br />

understand his audience and bring them to a new<br />

understanding of the world. In Athens, Greece,<br />

he noticed a number of pagan<br />

shrines dedicated to<br />

various gods of the ancient<br />

world. Among them was one<br />

peculiar altar, and he used<br />

that observation as the cornerstone<br />

of his teaching:<br />

You Athenians, I see that<br />

in every respect you are<br />

very religious. For as I<br />

walked around looking<br />

carefully at your shrines,<br />

I even discovered an<br />

altar inscribed, “To an<br />

Unknown God.” What therefore you unknowingly<br />

worship, I proclaim to you. The<br />

God who made the world and all that is<br />

in it, the Lord of heaven and earth, does<br />

not dwell in sanctuaries made by human<br />

hands, nor is he served by human hands<br />

because he needs anything. Rather it is<br />

he who gives to everyone life and breath<br />

and everything. (Acts 17:22–25)<br />

Paul even quoted from the Greek poets so<br />

his audience might hear the message of the God<br />

of Israel and His Son, Jesus, with a more open<br />

heart.<br />

Paul traveled the world establishing churches,<br />

and the New Testament preserves several of<br />

his letters. They reveal a man eager to win the<br />

hearts of people to Jesus. He was concerned with<br />

the everyday life of people he met, he was confident<br />

that Jesus could transform their lives, and<br />

he used whatever images or ideas he could to<br />

communicate the truth to them.<br />

Paul traveled<br />

the world<br />

establishing<br />

churches.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

13<br />

The Unity of Scripture and Tradition<br />

There are two distinct modes of transmission of divine revelation: Sacred<br />

Tradition and Sacred Scripture. The word tradition comes from the Latin<br />

word tradere, which means “to hand over.” Thus, the Catechism explains<br />

of the handing on of the Gospel message, “this living transmission, accomplished<br />

in the Holy Spirit, is called Tradition, since it is distinct<br />

from Sacred Scripture, though closely connected to it” (78). In other<br />

words, Sacred Tradition encompasses the handing on, in time, of all the<br />

Apostles had received from Jesus’ teaching and example, as well as all<br />

the knowledge they had received from the Holy Spirit. In short, it is the<br />

entirety of the Church’s doctrine, life, and worship passed down from bishop<br />

to bishop and from age to age. Sacred Scripture, or the Bible, is “the<br />

speech of God as it is put down in writing under the breath of the Holy<br />

Spirit” (CCC 81). It is the written record of God’s revelation of Himself in<br />

Salvation History. Sacred Tradition, then, is the Word of God handed on<br />

and proclaimed.<br />

Both Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition share a common source:<br />

God Himself. The Catechism elaborates: “Sacred Tradition and Sacred<br />

Scripture, then, are bound closely together and communicate one<br />

with the other. For both of them, flowing out from the same divine<br />

well-spring, come together in some fashion to form one thing, and<br />

move towards the same goal” (80). Both Sacred Tradition and Sacred<br />

Scripture make “present and fruitful in the Church the mystery of<br />

Christ” (CCC 80), though in different and complementary ways. Together,<br />

“Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture form one sacred deposit of the word<br />

of God, committed to the Church” (Dei Verbum 10). This Deposit of Faith<br />

contains in whole all that has been divinely revealed to us. Thus, the Church<br />

“does not derive her certa<strong>int</strong>y about all revealed truths from the holy<br />

Scriptures alone. Both Scripture and Tradition must be accepted and<br />

honored with equal sentiments of devotion and reverence” (CCC 82).<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Tradition (n.): The<br />

handing on of customs<br />

or beliefs. From the Latin<br />

word tradere, meaning “to<br />

hand over” or “deliver.”<br />

Sacred Tradition (n.):<br />

The living transmission of<br />

the Gospel message in<br />

the Church.<br />

Deposit of Faith (n.):<br />

The full content of divine<br />

revelation communicated<br />

by Christ, contained in<br />

Sacred Scripture and<br />

Sacred Tradition, handed<br />

on in the Church from<br />

the time of the Apostles,<br />

and from which the<br />

Magisterium draws all that<br />

it proposes for belief as<br />

being divinely revealed.<br />

Although some may believe that Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition<br />

are at odds with each other, or that Sacred Scripture is more important<br />

than Sacred Tradition, these beliefs are false. First, because Scripture and<br />

Tradition share the same source, they cannot be opposed to each other.<br />

Truth never contradicts itself. Second, and more fundamentally, Sacred<br />

Scripture is part of Sacred Tradition; it is the part that was written down.<br />

Sacred Tradition existed before any of the New Testament was written.<br />

During the first years of the early Church, the Apostles proclaimed the<br />

Gospel solely through words and deeds. Moreover, Sacred Tradition assures<br />

us of Scripture’s authenticity — that the books of the Holy Bible are<br />

truly inspired by God.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

14 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Magisterium (n.): The<br />

living teaching authority<br />

of the Catholic Church<br />

whose task it is to give<br />

authentic <strong>int</strong>erpretation<br />

of the Word of God<br />

found in Scripture and<br />

Tradition, and to ensure<br />

the faithfulness of the<br />

Church to the teachings<br />

of the Apostles in matters<br />

of faith and morals. This<br />

authority is exercised by<br />

all of the world’s bishops<br />

in union with the pope,<br />

and by the pope alone<br />

when he defines infallibly<br />

a doctrine of faith or<br />

morals.<br />

Infallibility (n.):<br />

The charism of being<br />

infalliable (incapable of<br />

error) in matters of faith<br />

and morals.<br />

God, in His<br />

divine wisdom,<br />

has entrusted<br />

to His Church<br />

His revelation<br />

of Himself and<br />

His plan for<br />

salvation.<br />

Scripture, in turn, attests to the importance of Sacred Tradition. St.<br />

Paul writes, “Take as your norm the sound words that you heard from<br />

me. … Guard this rich trust with the help of the holy Spirit that dwells<br />

within us” (2 Tim. 1:13–14). He goes on to advise, “what you heard<br />

from me through many witnesses entrust to faithful people who will<br />

have the ability to teach others as well” (2 Tim. 2:2).<br />

The Magisterium<br />

The task of <strong>int</strong>erpreting the Deposit of Faith contained in both Sacred<br />

Scripture and Sacred Tradition belongs to the living teaching office of the<br />

Church alone, which is known as the Magisterium (from the Latin word<br />

magister, which means “teacher”). This authority is exercised in the name<br />

of Jesus Christ and “has been entrusted to the bishops in communion<br />

with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome” (CCC 85), who is the<br />

pope. Guided by the Holy Spirit, when the bishops, together in union with<br />

pope, teach definitively in matters of faith and morals, they are given the<br />

charism of infallibility, or being free from error. The Magisterium, however,<br />

is not above the Word of God, nor is it a source of revelation. Rather, it<br />

serves the Word of God by listening to it devotedly, guarding it, teaching<br />

and <strong>int</strong>erpreting it, and explaining it to each new generation, always with<br />

the help of the Holy Spirit.<br />

Sacred Tradition, Sacred Scripture, and the Magisterium “in accord<br />

with God’s most wise design, are so linked and joined together that one<br />

cannot stand without the others, and that all together and each in its own<br />

way under the action of the one Holy Spirit contribute effectively to the<br />

salvation of souls” (Dei Verbum 10). That is to say, God, in His divine wisdom,<br />

has entrusted to His Church His revelation of Himself and His plan for<br />

salvation in such a way that we can be confident that what the Church proposes<br />

for belief is true. This truth is drawn from the Deposit of Faith, given<br />

to the Church by Jesus Himself and handed on whole and <strong>int</strong>act through<br />

the centuries. And the authentic <strong>int</strong>erpretation of His Word is found in the<br />

Catholic Church. This divine design ensures that God’s loving and merciful<br />

invitation to be in a relationship with Him and to receive the gift of salvation<br />

is faithfully made to us all.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

15<br />

?<br />

Why do Catholics believe in things that<br />

are not found in the Bible?<br />

Everyone believes religious truths that<br />

are not found in the Bible. Protestants,<br />

for example, believe in the canon of<br />

Scripture — the list of books believed to<br />

be inspired by the Holy Spirit — but that<br />

list is not found anywhere in the Bible. So<br />

why do they hold certain books to be sacred?<br />

Because of Tradition.<br />

Remember, not everything Jesus said<br />

and did was written down. And even what<br />

was written down was not written down<br />

until decades after His Death. By that<br />

po<strong>int</strong>, the Church was already growing<br />

and spreading across the Roman Empire<br />

and beyond thanks to the preaching,<br />

teaching, and witness of the Apostles.<br />

These men handed on what they received<br />

from Jesus, and they expected<br />

their successors to do likewise.<br />

Three times St. Paul included this<br />

very sentiment in his letters, writing, “I<br />

praise you because you remember<br />

me in everything and hold fast to the<br />

traditions, just as I handed them on to<br />

you” (1 Cor. 11:2); “Therefore, brothers,<br />

stand firm and hold fast to the<br />

traditions that you were taught, either<br />

by an oral statement or by a letter of<br />

ours” (2 Thess. 2:15); and “We instruct<br />

you, brothers, in the name of [our]<br />

Lord Jesus Christ, to shun any brother<br />

who conducts himself in a disorderly<br />

way and not according to the tradition<br />

they received from us” (2 Thess. 3:6).<br />

So Scripture itself tells us to hold fast<br />

to traditions, which have been handed<br />

down by word of mouth. It tells us to believe<br />

and live certain teachings that are<br />

not included in Sacred Scripture. This,<br />

in large part, is because Scripture itself<br />

is part of Sacred Tradition. The reason<br />

we know which books are inspired by<br />

the Holy Spirit is because the Apostles<br />

and their successors handed down that<br />

knowledge from generation to generation<br />

until the Church decided it was prudent to<br />

officially compile it in a canon.<br />

All Catholic beliefs, however, are<br />

supported by the Bible. Certain words or<br />

prayers or teachings may not be mentioned<br />

explicitly, but all are mentioned at<br />

least implicitly. Sacred Scripture supports<br />

Sacred Tradition, just as Sacred Tradition<br />

supports Sacred Scripture.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

16 Sacred Scripture<br />

The Truth Is…<br />

Humanity failed to keep the promises made in the covenants with God — but<br />

God never failed on His end. In each of the covenants, God offered His people<br />

love, mercy, and protection, asking that they in return stay loyal to Him and<br />

turn away from sin. To this day, humanity yields to the temptation of the Devil<br />

and rejects God when we break His covenant of love. Yet God continues to<br />

remain faithful to the promises He made to us. God keeps loving us no matter<br />

how many times we hurt him. God keeps loving us even when we turn and walk<br />

away from Him. God’s love never fails, and He desires for us to return to His<br />

merciful embrace. It has been true for the entirety of Salvation History — just<br />

take a look!<br />

In the Old Testament, Israel failed so many times; we could even sympathize<br />

with God if He had given up and walked away. Yet He kept reaching<br />

out and revealing His heart to humanity. The Israelites built a golden calf and<br />

started worshiping it instead of God, yet He forgave them. King David committed<br />

adultery and murder, yet God forgave him. Even in His greatest act of love,<br />

when God sent His only Son <strong>int</strong>o the world, humanity rejected Him and brutally<br />

murdered Him. Each of us rejects God in this same way when we choose to<br />

sin, to turn our backs on Him. Jesus was nailed to the Cross because of our<br />

sins. And just as He forgave the Israelites and King David, so He forgives you.<br />

Jesus could have walked away from the suffering and death He underwent, but<br />

He willingly chose to die for us because He loves us. He waits for us with open<br />

arms every time we drift away. The narrative of Salvation History is not some<br />

distant fairytale — it is our story.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

17<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Focus and Reflection Questions<br />

1 What can we know about God from the use of reason?<br />

2 Why did God choose to reveal Himself to us?<br />

3 In what way did God prepare us to receive the fullness of His divine revelation? What is the<br />

process of this preparation called?<br />

4 What is Salvation History? How does it unfold?<br />

5 What is a covenant? What is involved in a covenant? How were they typically made in the<br />

ancient world?<br />

6 What are the six major covenants of Salvation History?<br />

7 What is the definitive stage of divine revelation? Why?<br />

8 How did Jesus make God known to the world?<br />

9 What is the Great Commission? How did the Apostles respond to it?<br />

10 What is apostolic succession? Who are the successors of the Apostles?<br />

11 What are Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture, and how are they related to one another?<br />

12 What is the Magisterium, and what is its responsibility?<br />

13 In what way is the Magisterium infallible?<br />

14 Why do Catholics believe things about the Faith that are not in the Bible?<br />

15 How did St. Paul evangelize to the Athenians? How can you apply his missionary approach in<br />

your own life?<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

18<br />

Sacred Scripture<br />

Straight to the Source<br />

ADDITIONAL READINGS FROM PRIMARY SOURCES<br />

For chapter 1, the primary source reading for this chapter will look in close detail at the official and dogmatic<br />

teaching of the Catholic Church regarding divine revelation found in the Vatican II document Dei Verbum. You<br />

will read all of Dei Verbum in this course.<br />

Dei Verbum 2, 5–6, The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation,<br />

November 18, 1968<br />

2. In His goodness and wisdom God chose to reveal Himself and to make known to us the hidden purpose<br />

of His will (see Eph. 1:9) by which through Christ, the Word made flesh, man might in the Holy<br />

Spirit have access to the Father and come to share in the divine nature (see Eph. 2:18; 2 Peter 1:4).<br />

Through this revelation, therefore, the invisible God (see Col. 1;15, 1 Tim. 1:17) out of the abundance<br />

of His love speaks to men as friends (see Ex. 33:11; John 15:14–15) and lives among them (see Bar.<br />

3:38), so that He may invite and take them <strong>int</strong>o fellowship with Himself. This plan of revelation is realized<br />

by deeds and words having an inner unity: the deeds wrought by God in the history of salvation<br />

manifest and confirm the teaching and realities signified by the words, while the words proclaim the<br />

deeds and clarify the mystery contained in them. By this revelation then, the deepest truth about God<br />

and the salvation of man shines out for our sake in Christ, who is both the mediator and the fullness of<br />

all revelation.<br />

5. “The obedience of faith” (Rom. 16:26; see 1:5; 2 Cor 10:5–6) “is to be given to God who reveals, an<br />

obedience by which man commits his whole self freely to God, offering the full submission of <strong>int</strong>ellect<br />

and will to God who reveals,” and freely assenting to the truth revealed by Him. To make this act of<br />

faith, the grace of God and the <strong>int</strong>erior help of the Holy Spirit must precede and assist, moving the heart<br />

and turning it to God, opening the eyes of the mind and giving “joy and ease to everyone in assenting<br />

to the truth and believing it.” To bring about an ever deeper understanding of revelation the same Holy<br />

Spirit constantly brings faith to completion by His gifts.<br />

6. Through divine revelation, God chose to show forth and communicate Himself and the eternal decisions<br />

of His will regarding the salvation of men. That is to say, He chose to share with them those divine<br />

treasures which totally transcend the understanding of the human mind.<br />

As a sacred synod has affirmed, God, the beginning and end of all things, can be known with certa<strong>int</strong>y<br />

from created reality by the light of human reason (see Rom. 1:20); but teaches that it is through His<br />

revelation that those religious truths which are by their nature accessible to human reason can be<br />

known by all men with ease, with solid certitude and with no trace of error, even in this present state<br />

of the human race.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 1: Divine Revelation and Its Transmission<br />

19<br />

Straight to the Source<br />

ADDITIONAL READINGS FROM PRIMARY SOURCES<br />

Focus Questions<br />

1 What does God do in His goodness and wisdom?<br />

2 Why does God speak to men as friends and live among us?<br />

3 How is God’s plan of revelation realized?<br />

4 What is the relationship between God’s words and deeds?<br />

5 Who is the mediator and fullness of all revelation?<br />

6 What is the Obedience of Faith? What is needed to make it?<br />

7 What did God choose to do?<br />

8 How can God be known with certa<strong>int</strong>y?<br />

9 What does God’s divine revelation reveal to us?<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Chapter 2<br />

The Inspiration<br />

and Structure of<br />

Sacred Scripture

Unit 1, Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred Scripture<br />

21<br />

Chapter Overview<br />

God is the author of every word in Scripture, but He also chose to use human authors<br />

to record the history of salvation. The Holy Spirit “breathed” <strong>int</strong>o the words of the Bible,<br />

making Scripture God’s living Word. The human authors worked with this inspiration from<br />

God and used their own talents and abilities to write the books included in the canon of the<br />

Bible. The canon, or collection of texts in Scripture, is comprised of 73 books, beginning<br />

with Genesis and ending with Revelation. Divided <strong>int</strong>o two main sections, the Old<br />

Testament and the New Testament, the books of the Bible present one connected story.<br />

Utilizing a variety of literary styles, the epic narrative of God’s love for His people is<br />

recounted through histories, prophesies, poetry, epistles, songs, and parables.<br />

In this chapter you will learn that…<br />

■ All Scripture is inspired by God.<br />

■ The authorship of Scripture is both fully the work of man and fully the work of God.<br />

■ Because Scripture is the living Word of God, we can be assured it is true and free from all error.<br />

■ The Old and New Testaments work together to give us a complete picture of Salvation History.<br />

■ Both the Old and New Testaments contain a wide variety of writing styles, or literary forms.<br />

Bible Basics<br />

All Scripture is inspired by God and is useful for<br />

teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training<br />

in righteousness.<br />

2 TIMOTHY 3:16<br />

Then he took the bread, said the blessing, broke it,<br />

and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which<br />

will be given for you; do this in memory of me.” And<br />

likewise the cup after they had eaten, saying, “This<br />

cup is the new covenant in my blood, which will be<br />

shed for you.”<br />

LUKE 22:19–20<br />

Connections to the Catechism<br />

CCC 105 (pg. 22)<br />

CCC 106 (pg. 22)<br />

CCC 107 (pg. 23)<br />

CCC 129 (pg. 24)<br />

CCC Glossary (pg. 24)<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

22 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Ruah (n.): Hebrew word<br />

meaning “breath” or<br />

“spirit.”<br />

Inerrant (adj.): Without<br />

error. Scripture is inerrant:<br />

it teaches without error<br />

the truth God wanted<br />

known for the sake of our<br />

salvation.<br />

These sacred<br />

writers were<br />

true authors<br />

and not puppets<br />

taking dictation<br />

from God.<br />

The Authors of Sacred Scripture<br />

All of Scripture is inspired by God. This truth means God moved through the<br />

human authors of Scripture to write what He wanted committed to writing for<br />

the sake of our salvation. Practically, this means that each book of the Bible<br />

has, in effect, two authors: a divine author and a human author. First and<br />

foremost, God is the primary author of Scripture. The Catechism states<br />

with no uncerta<strong>int</strong>y that “the books of the Old and the New Testaments,<br />

whole and entire, with all their parts … written under the inspiration<br />

of the Holy Spirit … have God as their author and have been handed<br />

on as such to the Church herself” (105). The truth expressed by the<br />

Catechism was shared by St. Paul, who wrote, “All Scripture is inspired<br />

by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and<br />

for training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16). The Greek word St. Paul<br />

used for inspired is theopneustos, literally “God-breathed.” We read about<br />

God’s Spirit at the beginning of creation and that God breathed His breath<br />

of life <strong>int</strong>o Adam to give him life. The Hebrew word for “spirit” and “breath”<br />

used in both instances is the same, ruah. Just as God’s Spirit was present<br />

at the creation of all things and was breathed <strong>int</strong>o Adam at his origin, so too<br />

is God’s Spirit breathed <strong>int</strong>o the Scriptures, making them the living Word<br />

of God. God, therefore, is the primary author of Scripture, as He really and<br />

truly speaks to us in the Word.<br />

At the same time, the human authors of the books of Scriptures are<br />

still true authors. The Catechism continues: “To compose the sacred<br />

books, God chose certain men who, all the while he employed them<br />

in this task, made full use of their own faculties and powers so that,<br />

though he acted in them and by them, it was as true authors that<br />

they consigned to writing whatever he wanted written, and no more”<br />

(106). While God did not put physical pen to paper to write the Scriptures,<br />

He wrote through the human authors of Scripture. These sacred writers<br />

were true authors and not puppets taking dictation from God. They wrote<br />

using their own powers and abilities, and chose the different writing styles,<br />

languages, and details in each story. In this way both God and the human<br />

authors are true authors of Scripture.<br />

The Inerrancy of Scripture<br />

Because God is the author of Scripture, we can be sure of its inerrancy,<br />

or that what it teaches is free from all error. This conclusion follows from<br />

our understanding of the very nature of God. God, after all, is all good, the<br />

fount of all holiness, and the source of truth. Obviously, the source of all<br />

truth cannot teach something that is wrong; truth cannot contradict truth.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred Scripture<br />

23<br />

The Catechism explains regarding Scripture’s inerrancy: “Since<br />

therefore all that the inspired authors or sacred writers affirm should<br />

be regarded as affirmed by the Holy Spirit, we must acknowledge that<br />

the books of Scripture firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that<br />

truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided<br />

to the Sacred Scriptures” (107). In other words, we can be 100 percent<br />

certain that Scripture contains the truth we need to know for the sake of<br />

our salvation. While some parts of the Bible may be <strong>int</strong>ended to be read<br />

as factual or historical record, and other parts as poetry or metaphor, everything<br />

in the Bible communicates to us some truth God wanted known<br />

in order for us to get to Heaven. Because Scripture is the living Word of<br />

God, we can always be assured that what God has spoken to us in His<br />

Word is true and free from all error. If we come across what seems to be<br />

a contradiction in the Scriptural text, it may be that we are <strong>int</strong>erpreting it<br />

wrong, have translated it wrong, or simply do not know enough to make a<br />

well-formed judgment.<br />

Since Scripture ultimately<br />

comes from God, we<br />

cannot doubt its truth and<br />

freedom from error.<br />

The Inspiration of Sa<strong>int</strong> Matthew by Caravaggio (1602).<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

24 Sacred Scripture<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Old Testament (n.): The<br />

46 books of the Bible<br />

that record the history of<br />

salvation from creation<br />

through the old covenant<br />

with Israel in preparation<br />

for the appearance of<br />

Christ as Savior of the<br />

World.<br />

New Testament (n.):<br />

The 27 books of the Bible<br />

written by the sacred<br />

authors in apostolic times<br />

that have Jesus Christ,<br />

the incarnate Son of God,<br />

as their central theme.<br />

Typology (n.): The study<br />

of how persons, events,<br />

or things in the Old<br />

Testament prefigured the<br />

fulfillment of God’s plan<br />

in the Person of Christ.<br />

The earlier thing is called<br />

a type.<br />

As an old saying<br />

put it, the New<br />

Testament lies<br />

hidden in the<br />

Old and the Old<br />

Testament is<br />

unveiled in the<br />

New.<br />

CCC 129<br />

The Structure of Sacred Scripture<br />

Before we can discuss certain principles for <strong>int</strong>erpreting Scripture, it is<br />

helpful to first have a better understanding of its structure. The Bible (which<br />

comes from the Latin word biblia, meaning “books” or “scrolls”) is a collection<br />

of many different types of books written over the course of thousands<br />

of years. Some of those books are histories; others are letters, songs,<br />

prophecies, wisdom literature, and more. Each book has to be <strong>int</strong>erpreted<br />

both on its own terms (as a work of history, prophecy, wisdom literature,<br />

and so forth) and in the context of the whole Bible.<br />

The Bible is arranged <strong>int</strong>o two parts: The Old Testament and the New<br />

Testament. The Old Testament contains the Jewish Scriptures and is focused<br />

on God’s work with humanity in general and the Jewish people in<br />

particular, from the creation of the world until a couple centuries before the<br />

birth of Jesus Christ. The New Testament focuses on the life and ministry<br />

of Jesus Christ and the history of the early Church. It contains the Gospels,<br />

the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles, and the Book of Revelation. The 27<br />

books of the New Testament are authoritative for Christian life and faith.<br />

Like Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition, the Old and New<br />

Testaments work together to give us a complete picture of Salvation<br />

History. Both are essential to understanding how God has worked in time<br />

to redeem us and make us holy. Each testament helps us understand<br />

the other; each sheds light on the other. They are, the Church teaches,<br />

mutually <strong>int</strong>erpreting, with the meaning of the New Testament concealed<br />

in the Old and the meaning of the Old Testament revealed and fulfilled in<br />

the New.<br />

The Church often refers to this way of reading Scripture as “typology.”<br />

In other words, by reading Scripture through a lens of typology, we are able<br />

to discern the “persons, events, or things in the Old Testament which<br />

prefigured … the fulfillment of God’s plan in the person of Christ”<br />

(glossary of the CCC). The Church has always used this way of reading<br />

the Scriptures to understand God’s saving plan. The Catechism explains:<br />

“Christians therefore read the Old Testament in the light of Christ crucified<br />

and risen …[and] the New Testament has to be read in the light<br />

of the Old. Early Christian catechesis made constant use of the Old<br />

Testament. As an old saying put it, the New Testament lies hidden in<br />

the Old and the Old Testament is unveiled in the New” (129).<br />

Both the Old and New Testaments contain different writing styles, or<br />

literary forms.<br />

■ Narrative: Narratives tell a story in a straightforward way, recounting<br />

some event or story of an important person in Israel’s history.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred Scripture<br />

25<br />

Law and Gospel by Lucas Cranach (16th century).<br />

■ Law: The Law, mostly contained in the first five books of the Bible,<br />

called the Pentateuch, are writings that communicate how to best love<br />

God and each other. The Law is necessary to free us from sin and<br />

direct us toward the ultimate goodness, who is God.<br />

The Old and New<br />

Testaments shed light on<br />

each other and give us a<br />

full account of Salvation<br />

History.<br />

■ Prophecy: The prophetic writings of the Bible foretold the consequences<br />

of Israel’s current course of action and called them to repentance<br />

and right worship of God. Prophetic writings also warn us today<br />

of similar actions and consequences in our own lives and call us to turn<br />

away from sin and pursue holiness. These writings would also tell of<br />

the fulfillment of God’s promises to His people and of His loving care<br />

for them.<br />

■ Poetry: The poetic writings of the Bible use metaphorical and artistic<br />

language to communicate basic truths about God and human nature.<br />

Although they typically do not rhyme, they follow a certain rhythm and<br />

meter and employ characteristic literary devices such as parallelism<br />

and repetition.<br />

■ Wisdom/proverbs: Wisdom literature comments on the human condition<br />

using learned, quotable sayings. These often offer advice for a<br />

wide range of topics and situations.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

26 Sacred Scripture<br />

The Church has declared<br />

and defended the full<br />

canon of Scripture<br />

as divinely inspired.<br />

<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Canon (n.): The official<br />

list of inspired books<br />

that appear in the Bible.<br />

The Catholic canon of<br />

Scripture includes 46 Old<br />

Testament books and 27<br />

New Testament books.<br />

St. Matthew and the Angel by Guido Reni (ca. 1635–1640).<br />

■ Parable: Parables are short stories that communicate layers of truth.<br />

Jesus often used parables to teach His disciples.<br />

■ Genealogy: Genealogies record family ancestries and reveal important<br />

family connections between individuals in the Bible.<br />

■ Epistle/letter: The epistles are letters written by St. Paul and other<br />

Apostles to early Christian communities and individuals to encourage<br />

them in their faith. They offer advice and teaching that often apply to<br />

our situations today.<br />

■ Apocalyptic: Apocalyptic writings communicate truths about God and<br />

our salvation through visions, often including strange imagery and<br />

symbolism.<br />

The Canon of Sacred Scripture<br />

The official list of inspired books in Sacred Scripture is called the canon of<br />

Scripture. The books of sacred Scripture delineated by the Church Fathers<br />

and defined at the Council of Trent includes 46 books of the Old Testament<br />

and 27 books of the New Testament.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

Unit 1, Chapter 2: The Inspiration and Structure of Sacred Scripture<br />

27<br />

Old Testament Canon<br />

Pentateuch<br />

New Testament Canon<br />

Gospels<br />

Genesis<br />

Exodus<br />

Leviticus<br />

Historical Books<br />

Joshua<br />

Judges<br />

Ruth<br />

1 & 2 Samuel<br />

1 & 2 Kings<br />

1 & 2 Chronicles<br />

Wisdom Books<br />

Job<br />

Psalms<br />

Proverbs<br />

Ecclesiastes<br />

Prophetic Books<br />

Major Prophets:<br />

Isaiah<br />

Jeremiah<br />

Lamentations*<br />

Baruch*†<br />

Ezekiel<br />

Daniel†<br />

*Included after Jeremiah<br />

†Deuterocanonical Book<br />

Numbers<br />

Deuteronomy<br />

Ezra<br />

Nehemiah<br />

Tobit†<br />

Judith†<br />

Esther†<br />

1 & 2 Maccabees†<br />

Song of Songs<br />

Wisdom†<br />

Sirach†<br />

Minor Prophets:<br />

Hosea<br />

Joel<br />

Amos<br />

Obadiah<br />

Jonah<br />

Micah<br />

Nahum<br />

Habakkuk<br />

Zephaniah<br />

Haggai<br />

Zechariah<br />

Malachi<br />

Matthew<br />

Mark<br />

Luke<br />

John<br />

Acts of the Apostles*<br />

Pauline Epistles<br />

Romans<br />

1 & 2 Cor<strong>int</strong>hians<br />

Galatians<br />

Ephesians<br />

Philippians<br />

Colossians<br />

1 & 2 Thessalonians<br />

1 & 2 Timothy†<br />

Titus†<br />

Philemon†<br />

Hebrews**<br />

Catholic Letters<br />

James<br />

1 & 2 Peter<br />

1, 2, & 3 John<br />

Jude<br />

Revelation*<br />

*These are each in a category of<br />

their own.<br />

**The authorship of this letter,<br />

although not its divine inspiration, is<br />

disputed.<br />

†These are also known as the<br />

Pastoral Letters.<br />

© Sophia Institute for Teachers

28 Sacred Scripture<br />

Lives of Faith<br />

St. Josemaria Escriva<br />

“Before God, who is eternal, you are much more a<br />

child than, before you, the tiniest toddler. And besides<br />

being a child, you are a child of God — Don’t<br />

forget it.”<br />

St. Josemaria Escriva is one of the most<br />

quotable sa<strong>int</strong>s. His books The Way, Furrow, and<br />

The Forge are filled with short sayings that ring<br />

true long after they are read. His unique views on<br />

Christian spirituality came from the crucible of a<br />

difficult life.<br />

In 1902, Josemaria was born in Spain to loving<br />

and hard-working parents. His father was<br />

once a successful business owner, but the business<br />

failed, and he was left to serve as a clerk<br />

in the clothing store he once owned. Josemaria’s<br />

family also experienced the tragedy of three of his<br />

siblings passing away in the span of three years.<br />

He discovered his vocation early on in life<br />

when he began to ask who God was and what it<br />

really meant to serve Him. Though young, he took<br />

on added prayers and penances as he tried to<br />

discern the will of God. As he was preparing to become<br />

a priest, tragedy struck the family when his<br />

father passed away, leaving Josemaria to support<br />

his mother and his surviving siblings. Upon his ordination,<br />

he immersed himself <strong>int</strong>o his priesthood<br />

and lived at the service of others. Of the priesthood<br />

he said, “A priest should love the young and<br />

the old, the poor and the rich, the sick and the<br />

children. He should prepare himself well to celebrate<br />

Mass. He should welcome and take care of<br />

souls one by one, like a shepherd who knows his<br />

flock and calls each sheep by name. We priests<br />

do not have rights. I like to<br />

think of myself as a servant<br />

of all, and in this title I take<br />

pride.”<br />

St. Josemaria is perhaps<br />

best known for founding<br />

the organization Opus Dei,<br />

which offers religious formation<br />

for laymen, priests,<br />

and religious to live lives of<br />

holiness no matter their situation.<br />

He explained Opus<br />

Dei to Time magazine in<br />

this way: “Opus Dei aims to<br />

encourage people of every<br />

sector of society to desire<br />

holiness in the midst of the world. In other words,<br />

Opus Dei proposes to help ordinary citizens like<br />

yourself to lead a fully Christian life, without modifying<br />

their normal way of life, their daily work, their<br />

aspirations and ambitions.”<br />

Going on, he said, “Opus Dei is not <strong>int</strong>erested<br />

in vows or promises. It asks its members to make<br />

an effort to practice human and Christian virtues,<br />