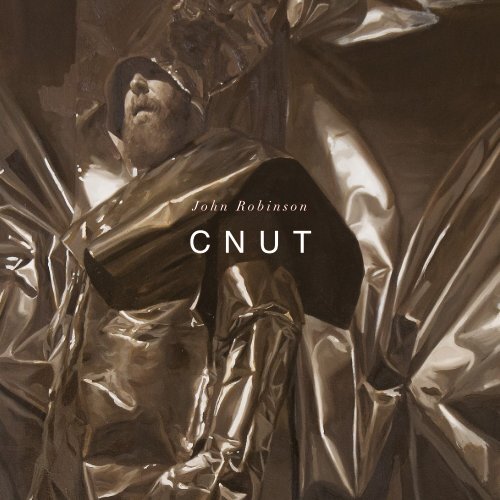

John Robinson 'CNUT'

Fully illustrated online catalogue of the solo exhibition 'CNUT' by John Robinson at Anima Mundi, St. Ives

Fully illustrated online catalogue of the solo exhibition 'CNUT' by John Robinson at Anima Mundi, St. Ives

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>John</strong> <strong>Robinson</strong><br />

CNUT

“When he was at the height of his ascendancy, he<br />

ordered his chair to be placed on the sea-shore<br />

as the tide was coming in. Then he said to the<br />

rising tide, “You are subject to me, as the land on<br />

which I am sitting is mine, and no one has resisted<br />

my overlordship with impunity. I command you,<br />

therefore, not to rise on to my land, nor to presume<br />

to wet the clothing or limbs of your master.” But the<br />

sea came up as usual, and disrespectfully drenched<br />

the king’s feet and shins. So jumping back, the king<br />

cried, “Let all the world know that the power of<br />

kings is empty and worthless, and there is no king<br />

worthy of the name save Him by whose will heaven,<br />

earth and the sea obey eternal laws.”<br />

Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon,<br />

‘Historia Anglorum (History of the English People)’<br />

(c. 1154)

4

5

<strong>John</strong> <strong>Robinson</strong>’s technical prowess could be<br />

seen to be shared with the pantheon of<br />

great masters of the 17th and 18th centuries<br />

including artists such as Diego Velazquez<br />

and Francisco Goya with a developing focus<br />

on self portraiture adopted by the likes of<br />

Rembrandt Van Rijn or more recently Frida<br />

Kahlo. However <strong>Robinson</strong>’s figurative yet often<br />

absurd works offer a contemporary subversion<br />

of the rich tradition of self portraiture.<br />

<strong>Robinson</strong>’s process often involves private<br />

performance, seasoned with personal, cultural<br />

and socio-political symbolism, which is<br />

recorded in the shed in his garden, then a still<br />

is taken from the video of these actions, which<br />

is then developed and exquisitely rendered,<br />

usually in oil paint on canvas. The final process<br />

imbues the subject with an intangible emotive<br />

quality that only the gesture of painting can<br />

imply, made all the more remarkable by the<br />

fact that perhaps only two or three colours<br />

are dexterously used to create his vision. For<br />

<strong>Robinson</strong> these paintings embrace personal<br />

concern, disclosure and catharsis, for the<br />

voyeur the experience appears both elaborately<br />

grandiose and awkwardly revealing.<br />

It is widely accepted that the function and<br />

aim of a portrait, be it of other or of self, is<br />

to reveal or expose often elusive aspects of<br />

the subject. The notion of ‘exposure’ in these<br />

paintings, is notably ambiguous and<br />

psychologically complex, embodying a duality<br />

that represents both continuity and departure<br />

from the great tradition. This duality is well<br />

highlighted by Fernando Pessoa who once wrote<br />

“Masquerades disclose the reality of souls.<br />

As long as no one sees who we are, we can<br />

tell the most intimate details of our life. I<br />

sometimes muse over this sketch of a story<br />

about a man afflicted by one of those personal<br />

tragedies born of extreme shyness who one<br />

day, while wearing a mask I don’t know where,<br />

told another mask all the most personal, most<br />

secret, most unthinkable things that could<br />

be told about his tragic and serene life. And<br />

since no outward detail would give him away,<br />

he having disguised even his voice, and since<br />

he didn’t take careful note of whoever had<br />

listened to him, he could enjoy the ample<br />

sensation of knowing that somewhere in the<br />

world there was someone who knew him as not<br />

even his closest and finest friend did. When he<br />

walked down the street he would ask himself<br />

if this person, or that one, or that person over<br />

there might not be the one to whom he’d once,<br />

wearing a mask, told his most private life. Thus<br />

would be born in him a new interest in each<br />

person, since each person might be his only,<br />

unknown confidant.”<br />

As Picasso once stated, to be often re-quoted,<br />

‘Art is a lie that makes us realize truth’- a<br />

mask worn provides the protection so that the<br />

truth can then be told perhaps. So what is the<br />

truth? Who are we? We live in a ‘selfie’ ravaged<br />

world of hide and seek, where the ubiquitous<br />

manipulated self represented image fills the<br />

cloud and airwaves. A world contorting a pout<br />

to the mirror which is turned for each and<br />

everyone to see. Is this what a vision of self<br />

looks like? Friedrich Nietzsche wrote “One’s<br />

own self is well hidden from one’s own self;<br />

of all mines of treasure, one’s own is the last<br />

to be dug up.” So who is <strong>John</strong> <strong>Robinson</strong>?<br />

4

Perhaps <strong>John</strong> doesn’t quite know. He, and we<br />

through his paintings, see exposed glimpses<br />

through a process of excavation, through<br />

layers of mystery and concealment.<br />

To return to the pervasive ‘Selfie’. I assume<br />

I am not alone in finding the viewing of<br />

them often more than a little ridiculous and<br />

occasionally quite troubling (especially on<br />

societal mass). Perhaps I’m just confused by<br />

them. Do they represent a narcissistic side<br />

of our character? With apps to make the skin<br />

clearer and eyes bigger, are we looking at a<br />

delusion of grandeur? Or conversely are we<br />

looking at a quieter and more communicative<br />

need to connect, to be witnessed, a vulnerable<br />

state, tainted with self doubt and perhaps, in<br />

more extreme cases, self loathing?<br />

‘CNUT’, the title of the exhibition makes<br />

reference to one of <strong>Robinson</strong>’s paintings titled<br />

‘Knig Cnut’, a bizarre and grandiose portrait,<br />

where artist absurdly postures as a parody<br />

King and self appointed ruler of his kingdom.<br />

When speaking with <strong>John</strong>, the person as<br />

opposed to the performer, there are seemingly<br />

no hubristic delusions, instead humility and<br />

a little doubt, occasionally give way to more<br />

crushing spasms of self deprecation. In the<br />

emphatically titled painting ‘Allegory of Brexit<br />

(Knives and Balloons / I Hate Myself and I<br />

Want to Die)’, we see in the foreground, the<br />

larger than life protagonist in confident pose<br />

despite the deeply concerning maelstrom of<br />

vulnerability, violence and fragility implied by<br />

the rest of the painted activity. <strong>John</strong> then points<br />

out, lingering in the background, in his words<br />

not mine ‘the fat, bald, cunt lost and loitering’.<br />

The often resplendent theatricality of the<br />

presented situations, barely mask the more<br />

prosaic ‘kitchen sink’ vulnerability of each<br />

painting. Charles Dicken’s once stated that<br />

“There are only two styles of portrait painting;<br />

the serious and the smirk.” <strong>Robinson</strong>’s<br />

works often leave the viewer in a limbo of<br />

doubt as to whether to laugh or to cry, at<br />

seemingly simultaneously absurdly comic and<br />

psychologically revealing studies in to the<br />

human condition. You get the feeling either<br />

would be fine and welcomed by <strong>John</strong>. Much<br />

less ambiguous however, in its emotional<br />

intent or resultant message, one epic painting<br />

references the ‘Triumph of Death’ by Pieter<br />

Bruegel painted in 1562. Made in response<br />

to the growing panic surrounding the Covid<br />

pandemic, <strong>Robinson</strong> lost his father to the<br />

disease midway through the making of<br />

the work drenching it with personal and<br />

universal pertinence.<br />

To search and then to understand oneself is so<br />

continually elusive and ephemeral, so perhaps<br />

it is no wonder that genuine connection with<br />

an ‘other’, in a day and age when the avatar<br />

often stands in front of the our ‘real’ more<br />

shadowy entity, feels more and more difficult<br />

and urgent. Carl Jung wrote that “The meeting<br />

of two personalities is like the contact of two<br />

chemical substances: if there is any reaction,<br />

both are transformed.” By <strong>John</strong> allowing us in<br />

to his guarded world in such an unguarded<br />

way, I hope that he and we can ‘feel’ our<br />

way forwards.<br />

Joseph Clarke, 2021<br />

5

Knig Cnut<br />

oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm<br />

6

7

8

Buddha Beard<br />

oil on canvas, 45 x 40 cm<br />

9

8 of Cups<br />

oil on canvas, 50 x 40 cm<br />

10

11

12

Me and Death in the Woods<br />

oil on canvas, 45 x 40 cm<br />

13

Hombo<br />

oil on canvas, 75 x 60 cm<br />

14

15

16

Dear Gustav Nose Woods<br />

oil on canvas, 45 x 40 cm<br />

17

Kazimir’s Birthday<br />

oil on canvas, 45 x 50 cm<br />

18

19

20

Ovals and Plant<br />

oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm<br />

21

Cuckold with Flowers<br />

oil on paper on canvas, 60 x 40 cm<br />

22

23

24

Hermit with Flowers<br />

oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm<br />

25

All My Friends / Goodnight Elizabeth<br />

oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm<br />

26

27

28

Pirate<br />

oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm<br />

29

The Landlord<br />

oil on canvas, 45 x 40 cm<br />

30

31

32

Cocksmoker<br />

oil on canvas, 50 x 40 cm<br />

33

Don’t Worry Im Perfectly Safe<br />

oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm<br />

34

35

36

The Reflecting God<br />

oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm<br />

37

Survivor<br />

oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm<br />

38

39

40

Survivor<br />

oil on canvas, 100 x 150 cm<br />

41

Survivor Portrait<br />

oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm<br />

42

43

44

Survivor 2020<br />

oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm<br />

45

Allegory of Brexit (Knives and Balloons / I Hate Myself and I want to Die)<br />

oil on canvas, 160 x 120 cm<br />

46

47

48

The Triumph of Death (for Phil <strong>Robinson</strong>)<br />

oil on canvas, 160 x 200 cm<br />

49

<strong>John</strong> <strong>Robinson</strong> was born in Worcester, UK where<br />

he still resides. He studied Fine Art at Falmouth<br />

College of Arts, spending most of the time whilst<br />

there skipping tutorials to travel to Plymouth<br />

to be taught by the notorious and idiosyncratic<br />

painter Robert Lenkiewicz. <strong>Robinson</strong> was awarded<br />

the Richard Ford Scholarship by the Royal<br />

Academy of Arts and spent a summer as artist in<br />

residence at the Prado Museum, Madrid absorbing<br />

the works of Velazquez and Goya. He stayed in<br />

Madrid for a further decade broken by a year at<br />

Central Saint Martins on a Masters degree in fine<br />

art. He later developed his duel use of ‘painting’<br />

as revelation and disguise; ‘self portrait as<br />

(other…)’. He has won the Peter Spicer Award for<br />

Excellence in Creative Arts (First Place), Richard<br />

Ford Award for Painting, Royal Academy, London<br />

(First Place), South Square Trust Scholarship for<br />

MA study at Byam Shaw School of Art, Central<br />

Saint Martins, London, Alfa Romeo Award Art<br />

(‘Best of show nominee’)Madrid, Spain, Premio<br />

de Pintura Focus-Abengoa, Seville, Spain<br />

(Winner) and the Hauser and Wirth Prize, Hauser<br />

and Wirth Somerset UK (First Prize). <strong>Robinson</strong><br />

has widely exhibited his work internationally.<br />

Works are held in notable collections including<br />

University of the Arts London permanent<br />

collection, Nicolas & Maxinne Leslau Collection,<br />

Focus-Abengoa Foundation in Seville, Coldwell<br />

Banker in Madrid, Falmouth College of Arts<br />

Library, Museo del Ferrocarril in Madrid, Stedlijk<br />

Museum in Amsterdam, Wellcome Collection in<br />

London and the British Council Collection. He<br />

is managed by Stjarna Arts. ‘CNUT’ is his debut<br />

solo exhibition at Anima Mundi.<br />

50

Published by Anima Mundi to coincide with <strong>John</strong> <strong>Robinson</strong> ‘CNUT’<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or<br />

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers<br />

Anima Mundi . Street-an-Pol . St. Ives . Cornwall . +44 (0)1736 793121 . mail@animamundigallery.com . www.animamundigallery.com