You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

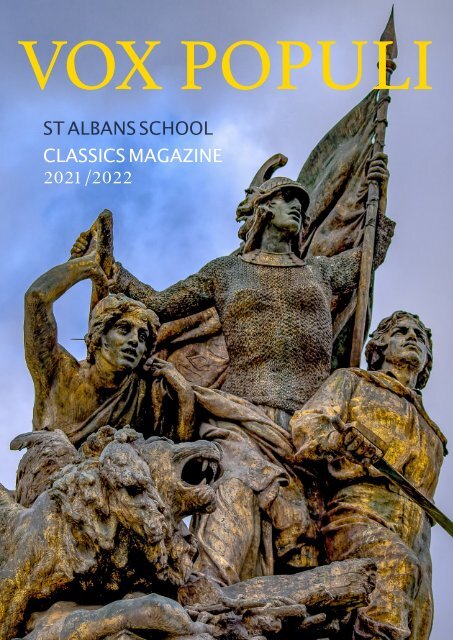

<strong>VOX</strong> <strong>POPULI</strong><br />

ST ALBANS SCHOOL<br />

CLASSICS MAGAZINE<br />

2021/<strong>2022</strong>

CONTENTS<br />

Editorial .............................................................................................5<br />

A Contemporary Retelling of Ovid’s Metamorphoses ..........................6<br />

It’s not the worst thing about the speech, but......................................8<br />

Acceptance in Iliad. 24 .......................................................................10<br />

Second Form Latin Trip ......................................................................14<br />

Latin Lessons at St Albans School ......................................................15<br />

Ancient Languages: the Empire(s) Strikes Back..................................16<br />

Ancient Architecture ..........................................................................18<br />

Should We Cancel the Romans?..........................................................20<br />

The Origins of Theatre........................................................................21<br />

A Tragic Triumvirate: Tragedy in Ancient Greece ................................24<br />

Aeschylus...........................................................................................25<br />

Sophocles ..........................................................................................26<br />

Euripides............................................................................................27<br />

Agriculture in the Roman World ..........................................................28<br />

Art in Ancient Greece .........................................................................30<br />

Rome before the Romans: The Tale of the Etruscans ..........................34<br />

Nero ...................................................................................................36<br />

Introducing Comparative Philology: Dr Tom McConnell ......................38<br />

National Gallery Trip Review...............................................................40<br />

‘A View from the Bridge’ and the Use of Chorus in Modern Tragedy ...42<br />

Alcibiades, the Boris Johnson of Ancient Athens? .............................46<br />

The Colosseum...................................................................................48<br />

Latin and Modern Languages..............................................................50

Editorial<br />

When deciding on a theme for this edition of vox populi, our initial idea<br />

was Drama. As the year progressed, however, it soon became clear that<br />

the sheer variety of activities and topics explored by the Classics<br />

Department meant that there would be far more to talk about. With the<br />

pandemic restrictions being eased, the Hylocomian Society has seen a<br />

resurgence, with a number of interesting lectures. Likewise, the Lower<br />

Sixth Form have been involved in researching and producing<br />

presentations independently, on any subject of their choice.<br />

With this in mind, it became clear that not only would we be able to cover<br />

Drama, but a wealth of additional content too. Therefore, rather than<br />

honing in on one specific focus, this edition instead highlights the sheer<br />

breadth of the Classical World - the vastness of which, we hope, we have<br />

achieved in conveying. Indeed, there is something here for everyone.<br />

From politics to architecture; theatre to agriculture; literature to linguistics,<br />

there are few stones left unturned. It is therefore with great pleasure that I<br />

invite you to explore the array of topics presented here, and I hope that, of<br />

the many articles contained herein, you find something that interests you.<br />

I would like to thank all those who have played a hand in the creation of<br />

this publication. Firstly, to the students and staff who have contributed<br />

articles throughout the year. Of course, I would also like to thank my fellow<br />

editors in the Lower Sixth Form, whose support has proven valuable<br />

indeed. Chiefly, however, I would like to extend special thanks to Mrs<br />

Ginsburg, the Head of the Classics Department, whose organisation and<br />

drive ensured this publication saw the light of day.<br />

Conrad, Lower Sixth Form<br />

~4~ ~5~

A Contemporary Retelling of Ovid’s<br />

Metamorphoses<br />

Jealous wives, vengeful lovers,<br />

scorned husbands and those<br />

manipulated by more powerful<br />

people- is this an episode of the Real<br />

Housewives of Beverly Hills or<br />

possibly the front page of the Daily<br />

Mail? Neither, these are tales,<br />

immortalised by the Roman poet,<br />

Ovid, in his epic poem the<br />

Metamorphoses; but there is a twist,<br />

each story involves a transformation<br />

from one physical state to another and<br />

in each tale, the protagonists are gods,<br />

and their victims are mortals.<br />

This fantastic production was set in the<br />

intimate Sam Wanamaker Playhouse,<br />

where the 50-strong audience were<br />

entertained by 4 actors, using 100<br />

props and buckets of fantastical<br />

creativity, from a burning chariot of fire<br />

to shape-shifting animals.<br />

Jupiter was portrayed as an arrogant<br />

louche god, dressed in a white suit,<br />

topped off with mirrored shades, in<br />

love with his power and greatness; his<br />

wife, Juno, his regal opposite was a<br />

powerhouse of sharp-tailoring armed<br />

with a bitter tongue with which she<br />

harangued her preternaturally<br />

unfaithful husband. His conquests<br />

were dealt with more viscerally,<br />

whether or not they willingly<br />

succumbed to his physical overtures.<br />

The production shed a contemporary<br />

light on the question of consent and<br />

the coercion of a weaker individual by<br />

someone wielding power.<br />

The modern question of gender and<br />

identity was humorously covered in<br />

the retelling of the story of Tiresias.<br />

Tiresias, born a man, who then lived as<br />

a woman is brought into a dispute by<br />

the constantly warring Jupiter and<br />

Juno, demanding an answer to the<br />

question- who is sex more pleasurable<br />

for- a man or a woman? Juno is<br />

mightily displeased with his answer<br />

that women experience the greater<br />

pleasure, punishing him with<br />

blindness. Jupiter, in a stroke of<br />

humorous sport, thanks him for his<br />

support by giving him the gift of<br />

prophecy, providing the oxymoron of<br />

a bind seer.<br />

The insecurities of the gods was<br />

illustrated by the tale of Arachne,<br />

metamorphosed into an arachnid, by<br />

Minerva, who can’t take a joke that<br />

pokes fun at her lifestyle and her talent<br />

with weaving. It turns out that immortal<br />

power and exemplary talent does not<br />

lead to personal confidence and<br />

happiness.<br />

The gods were displayed more<br />

favourably in the story of Philemon<br />

and Baucis, who, in a modern retelling<br />

of Noah and the Flood, are rewarded<br />

for their goodness, contrasting with<br />

the evil of their fellow man, by dying<br />

simultaneously, so that neither should<br />

suffer the pain of living without the<br />

other. Their transformation into trees<br />

was a sensitive reworking of the theme<br />

of metamorphosis that links each of<br />

Ovid’s tales.<br />

This production was uncomfortable in<br />

its portrayal of sexual abuse, physical<br />

violence, washed down with<br />

bucketfuls of gore, vitriol and<br />

uncomfortable themes- all entirely as<br />

Ovid intended. The shock factor was<br />

how prevalent these themes still are<br />

today.<br />

Mrs V Ginsburg<br />

~6~ ~7~

It’s not the worst thing about the<br />

speech, but..<br />

How did such a brilliant Classicist make the mistake of using this quote, which so<br />

thoroughly undermines the argument of his speech? The only way I can<br />

understand it is that it was wilful blindness – he let his prejudice overwhelm his<br />

intellect. Luckily, we can read the Aeneid for ourselves in all its deep humanity.<br />

Mr M Davies<br />

2018 saw a grim 50th anniversary –<br />

that of the notorious “Rivers of Blood”<br />

speech, seen as the most extreme<br />

expression of racism ever to be made<br />

in this country by a previously<br />

mainstream politician. Enoch Powell, a<br />

former Conservative minister, said in<br />

it: “We must be mad, literally mad, as a<br />

nation to be permitting the annual<br />

inflow of some 50,000 [immigrants]. …<br />

In this country in 15 or 20 years' time<br />

the black man will have the whip hand<br />

over the white man.”<br />

The title of the speech comes from a<br />

sentence in which Powell says: “as I<br />

look ahead, I am filled with<br />

foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to<br />

see ‘the River Tiber foaming with<br />

much blood’”.<br />

Enoch Powell had been a professional<br />

Classics scholar before entering<br />

parliament. He was so brilliant that he<br />

was appointed a Professor of Greek<br />

when he was only 25. His books on<br />

Herodotus are still used.<br />

It is surprising, then, that he made a<br />

reference that seems so ignorant. The<br />

quote that he makes is from Virgil’s<br />

Roman epic the Aeneid (it is in Book 6,<br />

line 87). But it is not a Roman that<br />

speaks these words – it is the Sibyl, a<br />

prophetess of Greek origin. And the<br />

context of the words in the Aeneid as<br />

a whole makes them an odd choice, to<br />

say the least, to quote in a speech that<br />

was anti-immigration, as a warning of<br />

the violence that immigration would<br />

allegedly cause.<br />

description that follows him around,<br />

“dutiful” (pius). The Trojans that he<br />

leads are also refugees, described<br />

when first mentioned as “the remnants<br />

left by the Greeks … driven around<br />

every sea by the Fates”. They, like<br />

many others, have become refugees<br />

because of the destruction of their<br />

home in war. The founder of the<br />

glorious Roman nation and his men<br />

were immigrants to Italy.<br />

The Sibyl foresees “the River Tiber<br />

foaming with much blood” because<br />

Aeneas will fight with the Latins of<br />

Latium (modern Lazio). But, far from<br />

sending the message that immigration<br />

inevitably leads to violence, the poem<br />

shows us that this fighting was<br />

completely unnecessary and<br />

avoidable. King Latinus was happy to<br />

give the Trojans a place to settle in<br />

Latium and to marry his daughter<br />

Lavinia to Prince Aeneas. It is only<br />

because of the interference of the<br />

goddess Juno, who hates the Trojans,<br />

that war breaks out. At the end of the<br />

war, the Trojans settle in Latium and<br />

Aeneas marries Lavinia. This was<br />

always fated to happen, and all the<br />

bloodshed has achieved literally<br />

nothing. And, while the poem ends<br />

with the end of the war, it is full of<br />

reminders that, far from destroying<br />

Italy, the descendants of these<br />

immigrant Trojans will lead it to<br />

unheard-of wealth and glory.<br />

Aeneas, the hero of the book, is a<br />

refugee (profugus) – we are told this<br />

about him in the second line of the<br />

poem, before we are told his name<br />

and long before we meet the other<br />

~8~ ~9~

Acceptance in Iliad. 24<br />

Although Homer’s final book of his<br />

Iliad fixes into a neat ring-like<br />

structure, reflecting the beginning of<br />

the poem, it equally serves as an<br />

independent text within a greater<br />

holistic skeleton. Indeed, Colin<br />

Macleod believed that the book<br />

specifically defined the tragic nuances<br />

of the poem. Although I will not be<br />

able to give appropriate justice to the<br />

book’s deep sincerity, I hope to show<br />

its existential significances, which seek<br />

to explain the human condition and<br />

the necessity of endurance amongst<br />

the inevitable suffering embedded in<br />

life.<br />

Notwithstanding the futile<br />

protestations of his wife, the Trojan<br />

elder Priam sets out to ransom the<br />

mutilated corpse of his favourite son,<br />

Hector, from the best warrior of the<br />

Greeks, Achilles. Immediately, Priam’s<br />

lack of self-worth is apparent: despite<br />

the evident threat from the Greek<br />

warriors, he values the salvation of his<br />

son’s body more than his own and,<br />

therefore, is willing to risk his life. On<br />

his way, he is accosted by an<br />

anonymous young traveller (unknown<br />

to Priam, it is the god, Hermes), who<br />

leads the elderly man through the<br />

camp similarly to a young son guiding<br />

his old father. The primary function of<br />

this event, in my opinion, is to prepare<br />

the audience (as it would have been in<br />

eighth-century oral performances) for<br />

the importance of the father-son<br />

relationship, which is the premiss of<br />

Priam’s demands as he enters Achilles’<br />

hut.<br />

Priam’s supplication of Achilles reveals<br />

his desperation and accentuates his<br />

lack of self-worth: he is willing to yield<br />

completely to his son’s murderer for<br />

the sake of this ransom. By alluding to<br />

Peleus, Achilles’ father, Priam vibrates<br />

the heartstrings of the Greek as both<br />

characters join in their profuse<br />

lamentations for their deceased<br />

relatives. Here, one sees a more<br />

humane side to Achilles’ personality:<br />

he banishes his leonine pugnacity,<br />

acknowledges his impending death,<br />

and commends Priam’s audacity, while<br />

empathising with the old man’s<br />

situation. Both are struck by<br />

admiration and pity as they gaze into<br />

each other’s eyes: in an emphatic<br />

moment, and it is just a moment, Priam<br />

forgets that Achilles killed his son and<br />

Achilles forgets that Priam has<br />

orchestrated a ten-year war against<br />

the Greeks. Instead, they perceive<br />

each other as vulnerable mortals, who<br />

are forever punished by the capricious<br />

machinations of the Gods and, more<br />

specifically, their lot cast upon them at<br />

birth.<br />

Amongst the pity, which embodies<br />

this meeting, Homer grants Achilles a<br />

philosophical voice, as if the poet<br />

incarnates into his literary successors,<br />

Plato and Aristotle. Within the poem’s<br />

very claustrophobic setting, the bard<br />

provides a cosmological reading for<br />

this scene. He describes the myth, like<br />

Pandora’s box, of two jars in Zeus’s<br />

palace, one with ills and the other with<br />

both ills and blessings. Scholars have<br />

been universally divided by this<br />

conundrum, varying from Nietzsche’s<br />

nihilistic opinion that hope is the<br />

greatest evil to West’s more optimistic<br />

viewpoint that the hope is separate<br />

from the evil and, therefore, acts as a<br />

positive force for good. In my opinion,<br />

Homer wishes to prove, through the<br />

mouth of his reformed protagonist,<br />

that suffering is an inevitable course of<br />

life. Even if one’s life is filled with<br />

blessings and utmost joy, the ill of<br />

death, which looms over all helpless<br />

mortals, renders this happiness to an<br />

inevitable end.<br />

Despite their grief, Achilles<br />

encourages Priam to eat, citing the<br />

myth of Niobe, who ate after the<br />

slaughter of her children owing to her<br />

hubris. This has a three-fold<br />

significance: firstly, it adds an<br />

articulate edge to Achilles’ persona,<br />

almost meta-poetically elevating the<br />

son of Peleus to the form of the poet.<br />

This proffers more gravitas to his<br />

speech and, as such, its contents.<br />

Secondly, it confirms Achilles’ return to<br />

humanity as he provides customary<br />

food and drink to a guest, albeit a foe.<br />

Thirdly, and most importantly, it<br />

teaches one the value of<br />

perseverance: the presence of grief<br />

should not distract one from the<br />

necessities of survival and endurance.<br />

On the contrary, one should learn to<br />

live with these emotions, comprehend<br />

one’s inability to contain a world<br />

pervaded with uncontrollable forces,<br />

and accept that suffering, injustice,<br />

and inequality are inescapable<br />

courses of life.<br />

However, ultimately, the most<br />

profound element of this book is its<br />

brevity: the scene is a short hiatus<br />

from the trauma of war, where<br />

partialities are absolved, and the<br />

meaning of life can be perceived<br />

objectively. Indeed, ironically, and<br />

rather poignantly, it is the hope that a<br />

resolution between the sides will be<br />

formed, which encapsulates the<br />

tragedy within the text. After twelve<br />

days of mourning, the fighting will<br />

resume, Priam will be slaughtered in<br />

his palace, Troy will be consumed by<br />

fire and, crucially, Achilles will meet his<br />

premature end. The death of the<br />

Greek hero, the quasi-philosopher of<br />

Iliad. 24, proves the inescapability of<br />

one’s fate; his conscious decision to<br />

choose an early but glorious death,<br />

outlined earlier in the poem, shows<br />

that he accepts this inevitability. He<br />

accepts that a short but heroic life is<br />

better than a long but insignificant<br />

one.<br />

Iliad. 24 offers a pause for reflection<br />

where, amongst the acrimony of war,<br />

sufferer and sufferer can unite in their<br />

grief, caused by divine will and human<br />

pride. I believe that Iliad. 24 teaches<br />

one that complete happiness is<br />

unattainable; in fact, I would argue<br />

that such a disposition indicates one’s<br />

obliviousness to the harsh realities of<br />

existence. Instead, by learning to<br />

accept the fickle tendencies of a<br />

mortal life, to value those cherished<br />

friendships and relationships, and to<br />

endure those inevitable hardships will<br />

facilitate a life of self-contentment.<br />

Achilles and Priam provide an<br />

exemplum of this acceptance: they are<br />

aware of these existential injustices<br />

and, in a didactic way, teach us to live<br />

our lives to the full before we<br />

ourselves succumb to death.<br />

Mr E Baker<br />

~10~ ~11~

Second Form Latin Trip<br />

Latin Lessons at St Albans School<br />

The week beginning the 29th November, the Second Form were very privileged<br />

to be able to visit our local museum, in the park. Being only a five-minute walk<br />

away from school, it was very easy to get there!<br />

Once we arrived, we enjoyed a very in-depth handling session with various real<br />

and replica Roman artefacts, found in the park. We learned the history of what<br />

they were used for and where they had been found. This was extremely<br />

interesting as we were able to get a better understanding of what people used<br />

for everyday jobs in ancient Verulamium.<br />

After this, we had the chance to roam around the museum, looking at other<br />

artefacts and learning the history of the culture and life in ancient Verulamium.<br />

Next, we left the museum and crossed the road into the Gorhambury estate.<br />

There, we walked around a Roman theatre that is still in use today and saw where<br />

shops, houses and markets would have been.<br />

Then, we walked into the park to see a<br />

replica of a Roman Hypocaust. Here we<br />

could also see a large mosaic. This<br />

helped us imagine what would go into<br />

building an ancient Roman house.<br />

Before returning to school, we walked<br />

to the Roman wall ruins at the edge of<br />

the park. We learned that it was once a<br />

grand wall that went all the way<br />

around Verulamium to protect the<br />

citizens.<br />

We all thoroughly enjoyed the trip<br />

and are very grateful for the<br />

opportunity to learn about the<br />

historic grounds our school was<br />

built on and all of the culture that<br />

surrounded it.<br />

Only people who haven’t tried the wonderful language of Latin can ever say this<br />

isn't great to learn, fun to write in and intellectually astounding. I myself have tried<br />

this ancient language and recognized so many different etymologies, or word<br />

origins. The joy of finding out the English word ‘venue’ comes from ‘veno’,<br />

meaning ‘I walk’ is immense – it is incredible to finally know where words come<br />

from. An ambulance might amble up the street, or you might claim the clamorous<br />

people were exclaiming things. You might say learning a dead language is<br />

ridiculous, but that’s Latin for ‘laugh’. Even people who don’t like Latin can’t help<br />

speaking it!<br />

The grammar rules are simple to remember, and people who know French,<br />

Spanish or Italian will find this an excellent way to practice their skills and Latin is<br />

known, thanks to a US study, known to increase your grade in Maths, English,<br />

Science, etc. Over 60% of words in the English dictionary come from an Ancient<br />

Greek or Latin word - usually Latin.<br />

"I hope that even if you remember not a single word of mine, you remember those<br />

of Seneca, another of those old Romans I met when I fled down the Classics<br />

corridor, in retreat from career ladders, in search of ancient wisdom," quoted JK<br />

Rowling after receiving her honorary degree.<br />

As you can see, there is no reason not to love Latin. The teachers are great, and<br />

the language is engrossing - from Latin grossus meaning large in Latin. We get<br />

grocer - someone who sells large amounts of things - and French gros, meaning<br />

large from it. The word is related to grease.<br />

I end with some Latin words:<br />

dico 'vale' ad omnes homines qui in futuro Latinorum amatores erunt. spero te<br />

bene esse.<br />

In other words, bye!<br />

Parth, First Form<br />

Jamie, Second Form<br />

~14~ ~15~

Ancient Languages: the Empire(s)<br />

Strikes Back<br />

The linguistic benefits of learning<br />

Latin and Greek.<br />

As I work towards my end of course<br />

GCSE examinations in Latin, Greek<br />

and French, I have been reflecting on<br />

my enjoyment of the privilege of<br />

being able to learn a number of<br />

languages during my time at the<br />

school so far. I have studied Spanish<br />

and German prior to GCSE and have<br />

dabbled in Punic, the ancient<br />

Carthaginian language. Throughout<br />

my studies, I have noticed the benefits<br />

of learning Latin and Greek, not only<br />

for the pleasure they bring in their<br />

own right in facilitating my access to<br />

the literature and culture of the<br />

ancient world but also in their<br />

influence on my wider modern<br />

language learning and experience.<br />

The most obvious point of connection<br />

is that both Latin and Greek, unlike<br />

English, are inflected languages,<br />

which provides a mental shortcut to<br />

the grammatical structures of other<br />

modern languages with those shared<br />

structures. Having developed an<br />

understanding of the nominative,<br />

vocative, accusative, genitive, dative<br />

and ablative cases first in Latin<br />

provided a sound foundation for<br />

understanding the technicalities of<br />

working with a shorter list of cases in<br />

constructing sentences in German.<br />

Moreover, common elements of<br />

vocabulary or roots of vocabulary<br />

have made it easier to process the<br />

rigours of extensive vocabulary lists in<br />

Latin, Greek and French. An obvious<br />

example is the connection between<br />

the Latin ‘frater’ and the French ‘frère,’<br />

meaning ‘brother.’ It might be argued<br />

that the similarities could become<br />

confusing but actually it’s very useful<br />

as it allows you to work out the<br />

meanings of more complex unknown<br />

French vocabulary from Latin roots.<br />

A further element of studying ancient<br />

languages that I have found helpful is<br />

the prevalence of dialect in the Greek<br />

literature we have studied to date.<br />

Herodotus’ Histories and Homer’s Iliad<br />

are both written in dialects which are<br />

subtly different from the Attic Greek<br />

with which we began, at the start of<br />

the course. This is useful for<br />

developing an understanding of how<br />

languages can sound when spoken<br />

slightly differently and that nuance<br />

enhances our consideration of dialect<br />

in literature across the whole<br />

curriculum.<br />

Studying Classical languages has also<br />

broadened my horizons in terms of<br />

the geographical range of languages<br />

which sit under the umbrella of<br />

Classics. Traditionally thought of as<br />

Latin and Greek, ancient languages<br />

also include Sanskrit, Oscan and<br />

Hittite, to name but a few. An<br />

awareness of a wider linguistic<br />

perspective is important for<br />

understanding that the classical world<br />

does not begin and end in Europe<br />

and helps us to unpick some of our<br />

more problematic cultural<br />

assumptions about ‘western’<br />

civilisation and its interaction with<br />

other cultures. Particularly interesting<br />

for me has been an unexpected<br />

introduction to Punic, the language of<br />

the ancient Carthaginians from North<br />

Africa. Rome’s traditional enemy<br />

leaves little trace of its language, much<br />

to my frustration. When I tried to<br />

research Hannibal’s mother tongue, I<br />

found that, aside from a few Punic<br />

inscriptions, our best evidence for the<br />

language lies in a few lines of the<br />

Roman author Plautus’ play, The Little<br />

Carthaginian. The details of what is<br />

preserved are fascinating but the<br />

paucity of evidence for the language<br />

is a sobering reminder of the extent to<br />

which our cultural heritage is<br />

determined by what the powerful<br />

choose to preserve and pass on.<br />

Finally, I have benefitted from using<br />

my classical languages to understand<br />

better the role of verbal elements in<br />

constructing cultural nuance. By this I<br />

mean that it is sometimes the case that<br />

a Latin or Greek word may have a<br />

meaning which cannot be translated<br />

by a direct equivalent in English. An<br />

example of this is the Greek word<br />

‘aischros;’ it can mean ‘shameful,’<br />

disgraceful,’ or ‘ugly,’ depending on its<br />

context. Furthermore, it is a very<br />

specific word culturally as it has<br />

connotations of feeling shame in front<br />

of one’s peers, which is markedly<br />

different from, for example, a Christian<br />

sense of shame which is often<br />

described as an internal emotion,<br />

strongly related to guilt. These<br />

interesting words lead to an instinctive<br />

grasp of meaning within culture on<br />

encountering them regularly, although<br />

this can also result in some frustration<br />

when rendering them into Englishyou<br />

know what it means but you can’t<br />

find the word!<br />

All in all, the study of ancient and<br />

modern languages together is a<br />

powerful combination, not just in<br />

terms of supporting the achievement<br />

of competence in both but also in<br />

drawing out wider benefits and<br />

complexities both linguistically and<br />

culturally. It helps us to gain greater<br />

insight into our touch-points and<br />

differences with other cultures, which<br />

surely leads us to better<br />

understanding and empathy.<br />

Jonathan, Fifth Form<br />

~16~ ~17~

Ancient Architecture<br />

As part of the Lower Sixth Form ’Symposia', I decided to deliver an amusing talk<br />

on the architectural achievements of the Roman Empire, looking at a range of<br />

structures – everything from roads to bath-houses and even amphitheatres.<br />

Hoping to make it a memorable talk, I decided the best way to begin was with a<br />

nod to the classic Monty Python ‘what have the Romans ever done for us’ scene<br />

from The Life of Brian, by beginning with the first thing the Romans did for us –<br />

the aqueducts. Designed to provide a quick and easy way to move water from<br />

one place to another, it was powered by gravity: pulling water down a gradual<br />

slope from source to city. They were among the most important Roman structures<br />

– and, for me, also among the most impressive. Never mind the temples, the<br />

aqueducts are where it’s at!<br />

I then moved on to one of the Roman constructions most relevant in today’s<br />

world. The roads, like you would expect today, were well-built and wellmaintained.<br />

After all, an empire with no transport links can’t function too well.<br />

Taking advantage of advanced construction methods and featuring drainage<br />

similar to that of today’s, they’re another example of just how ahead of their time<br />

the Romans were.<br />

The baths were next on my agenda, as I discussed the rooms in which a typical<br />

Roman would socialise and relax after work, school or whatever else a citizen may<br />

get up to. I also discussed the marvels of the hypocaust – the underfloor heating<br />

system for the baths (and the wealthy). Fortunately, today’s central heating is<br />

nowhere near as taxing for the person operating it – we use a boiler and<br />

thermostat, instead of a furnace and a slave!<br />

Entertainment was just as important for the Romans as bathing, so naturally I also<br />

discussed the theatres and amphitheatres, while trying to keep my audience<br />

amused. Architecturally similar yet very different, it’s astounding how massive<br />

these structures are, and how so many still stand today. Remember, there were no<br />

power tools or tower cranes back then- all built by hand! A common theme<br />

between them was the use of the arch, an Etruscan invention that the Romans<br />

exploited endlessly for their own benefit.<br />

The fact that so many Roman constructions are left, and are in such good<br />

condition, just emphasises how good they were at building things. There’s even<br />

some of it on our doorstep at the Verulamium ruins. I can only recommend going<br />

to look at some Roman structures for yourself; take them in, and just imagine<br />

what it would have been like to be there when they were first built.<br />

Alex, Lower Sixth Form<br />

~18~ ~19~

Should We Cancel the Romans?<br />

The Origins of Theatre<br />

In a recent Classic Symposium, I<br />

delivered a talk on feminism, or the<br />

lack of, in Roman society. I talked<br />

about the expectations and limited<br />

roles, and concluded that they had a<br />

long way to go. During my talk, I<br />

discussed the protests against the<br />

Oppican Law, a unique and inspiring<br />

demonstration by the women of Rome<br />

that truly shows the power of a shared<br />

belief, as well as the historic epitaph of<br />

Claudia, “she made wool, she kept her<br />

house”. Roman society, while<br />

technologically advanced, had very<br />

strict gender roles and views that<br />

cannot be considered progressive by<br />

any modern standards. Women could<br />

make their own legal and financial<br />

decisions, or even vote. But should be<br />

‘cancel’ the Romans, stop reading their<br />

literature and studying their<br />

language?<br />

Roman society was at a high level of<br />

technological advancements, and by<br />

the late empire had a developed<br />

society. Yet, it still did not have equal<br />

rights and opportunities. By modern<br />

standards, any society that<br />

disenfranchises women is seen as oldfashioned<br />

and undemocratic. Yet the<br />

Romans, at least the Roman Republic,<br />

sought to call itself a representative<br />

democracy, despite not representing<br />

half of its population. If a celebrity<br />

expounded the view that a ‘good’<br />

woman must obey the paterfamilias<br />

(patriarch) of her family, their Twitter<br />

account would likely be deleted within<br />

the hour. So why do we not use the<br />

same philosophy with our forebears?<br />

It is important to note that Roman<br />

women still had some rights, for<br />

example the right to divorce. However,<br />

their societal model is not one we<br />

should be copying in the modern day.<br />

Instead, we should learn from their<br />

mistakes, and strive to make a better<br />

society. The only outcome of<br />

cancelling the Romans would be to<br />

lose hundreds of years of knowledge<br />

and experience, that could inform a<br />

greater future for all. Our current<br />

global society has a long way to go<br />

itself, and the only way to move<br />

forwards is to accept what has<br />

happened before.<br />

In summary, I do not believe we<br />

should cancel the Romans. While they<br />

had some backdated ideas, their<br />

stances on race and marriage and<br />

many other issues were parallel to or<br />

ahead our own. The Romans even<br />

realised the perils of monarchy, while<br />

we live under a Queen. The Roman<br />

Empire is a source of knowledge, but<br />

also a reference point to see just how<br />

developed we are in the 21st Century,<br />

and how far we have to go. The<br />

Romans should not be idolised, but<br />

neither should they be cancelled.<br />

Oliver, Lower Sixth Form<br />

Did you know that drama comes from<br />

the Greek word δράω meaning ‘I do’<br />

and theatre comes from θέατρον<br />

literally meaning ‘a place for viewing’?<br />

Well now you do, I’m guessing you<br />

can deduct that theatre started in<br />

Ancient Greece. More specifically in<br />

Athens sometime in the 6th Century<br />

BC. According to Aristotle, who was<br />

one of most respected Ancient Greek<br />

philosophers, noted that the very first<br />

forms of theatre were seen at festivals<br />

honouring Dionysus. Dionysus is the<br />

Greek god of fruitfulness, wine, and<br />

fertility to name a few, and in short<br />

resembled all that was majestic and<br />

charming about Ancient Greek culture<br />

at the time. At these festivals there was<br />

music and poetry readings and public<br />

speaking and from a combination of<br />

these things, theatre was formed.<br />

These earliest signs of drama came<br />

under three genres: One is comedy.<br />

Comedy actually originated from<br />

music, as well as festivals or mirth and<br />

phallic rituals, and because of this<br />

comedy wasn’t taken very seriously by<br />

most people at the time, looked at as<br />

an imitation of the ridiculous, but<br />

drama practitioners and enthusiasts,<br />

such as Aristotle, tried to teach it in<br />

such a way that it could be respected<br />

and professionalised. Next is tragedy,<br />

which originated from these dancedrama<br />

performances known as<br />

dithyrambs. Masks would almost<br />

always be used in tragedies to show<br />

different emotions more clearly to a<br />

large audience. An example of an<br />

Ancient Greek tragedy would be<br />

Medea by Euripides. The third is a<br />

Satyr play which to my surprise has<br />

nothing to do with satire. These<br />

involved mixing the two previous<br />

genres by using the structure and<br />

characters of a tragedy while adopting<br />

an happy atmosphere and a<br />

background. A satyr is actually a<br />

mythological spirit and in satyr plays<br />

there would be a chorus of satyrs<br />

miming and moving around in a<br />

comedic way.<br />

Theatre spread into Roman culture by<br />

about the 4th century BC, after the<br />

Etruscans came to Rome and gave<br />

performances to the people. The<br />

Romans developed western theatre,<br />

encouraging a higher quality of<br />

literature for the stage as well as street<br />

drama festivals.<br />

Ed, Lower Sixth Form<br />

~20~ ~21~

A Tragic Triumvirate: Tragedy in<br />

Ancient Greece<br />

Aeschylus<br />

To this very day, tragedy is associated<br />

with some of the greatest theatrical<br />

works in literary history. From<br />

Shakespeare to Ibsen, Chekhov to<br />

Marlowe, the genre has been firmly<br />

established as one of the most<br />

influential in theatre. The word tragedy<br />

itself is derived from Ancient Greek,<br />

and likely comes from the words for<br />

“goat-song” (τράγος (goat) + ᾠδή<br />

(song)). However, there are other<br />

suggestions that it comes from other<br />

origins, linked to, among others, beer<br />

and adolescent voice changes. That is<br />

not the only unresolved question<br />

either, as there is no one, decisive<br />

origin for tragedy. However, what is<br />

clear is that it emerged as a result of<br />

various influences of the time. For<br />

example, tragic stories often involved<br />

tropes commonly found in epic and<br />

lyric poetry. Similarly, the meter of<br />

tragedies was often iambic tetrameter,<br />

which arose in part due to the poems<br />

of Solon, a prominent Athenian<br />

statesman. Aristotle stated in the<br />

Poetics that tragedy began as an<br />

improvisation “by those who led off<br />

the dithyramb” – hymns in honour of<br />

Dionysus. Gradually, this began to<br />

develop into tragedy in a form closer<br />

what we would recognise, with the<br />

development of a few key features.<br />

Namely, the combining of spoken<br />

verse with the choral song, the<br />

growing interaction between actors,<br />

and the decrease in importance of the<br />

chorus. This resulted in the earliest<br />

form of drama we, in the modern day,<br />

would perhaps recognise, and was<br />

shaped further still by the figures to<br />

follow.<br />

Following articles all by Conrad,<br />

Lower Sixth Form<br />

Aeschylus was born in Eleusis,<br />

about 18km northwest of Athens, in<br />

around 525/524 BC, into a wealthy<br />

family. He is often described as the<br />

father of tragedy and wrote<br />

approximately seventy to ninety<br />

plays in his life, of which only seven<br />

survive. His first play was<br />

performed in 499 BC. One of the<br />

foremost influences on his life, and<br />

indeed his work, was his military<br />

service. In 490 BC he took part in<br />

the Persian Wars, where he fought<br />

in the Battle of Marathon. After this,<br />

he won his first victory at the<br />

Dionysia festival in the year 484 BC,<br />

symbolic of his growing<br />

prominence as a dramatist. Four<br />

years later he was again called back<br />

into military service, this time to<br />

fight against Xerxes I. He fought in<br />

the Battles of Salamis and Plataea,<br />

of the two Salamis would feature<br />

prominently in his oldest surviving<br />

play, ‘The Persians’. This play was<br />

performed in 472 BC, again at the<br />

Dionysia, where it won first prize<br />

once more. By 473 BC, his chief<br />

rival, Phrynichus, had died, leaving<br />

him with little significant<br />

competition. He would proceed to<br />

win almost every competition he<br />

attended at the Dionysia festival.<br />

One lesser-known fact about him is<br />

that he was actually a member of a<br />

cult of Demeter, the Eleusinian<br />

Mysteries, some of whose secrets<br />

he revealed on stage. This resulted<br />

in, according to some accounts, him<br />

being publicly attacked with stones.<br />

What is certain is that this event<br />

resulted in him going to trial, where<br />

he was eventually acquitted, in<br />

large part due to his military history.<br />

In 458 BC he went to Sicily, where<br />

he would remain until his death in<br />

456/455 BC.<br />

His works established the<br />

foundation of tragedies at the time;<br />

he introduced trilogies, which were<br />

3 plays in sequence - as you might<br />

imagine – which were usually<br />

followed by a satyr play. He also<br />

implemented a second actor, which<br />

allowed conflicts between<br />

characters to be performed on<br />

stage. Content wise, his plays were<br />

often strictly morale and religious in<br />

nature, as was typical of the time.<br />

“It is in the character of very few men to<br />

honour without envy a friend who has<br />

prospered”<br />

“From a small seed a mighty trunk may grow”<br />

“Wisdom comes through suffering”<br />

“His resolve is not to seem, but to be, the best”<br />

~24~ ~25~

Sophocles<br />

Euripides<br />

Sophocles was born in around<br />

497/496 BC in Colonus, Attica, into<br />

a wealthy family. He wrote over 120<br />

plays, although unfortunately only<br />

seven have survived in complete<br />

form. He was the most successful<br />

playwright of his time in terms of<br />

competition success: he competed<br />

in thirty competitions throughout<br />

his life, of which he won twentyfour,<br />

and came second in all the<br />

rest. In comparison, Aeschylus only<br />

won thirteen competitions, and the<br />

person coming up next, Euripides,<br />

only won five, with one of those<br />

five being posthumous. His first<br />

major artistic success came in 468<br />

BC, where he beat Aeschylus at the<br />

Dionysia, to win first prize. In 443<br />

BC he acted as one of the treasurers<br />

of Athena, where he helped<br />

manage money in Athens upon the<br />

ascendancy of Pericles. In 441 BC<br />

he was elected as one of ten<br />

generals of Athens and participated<br />

in the Athenian campaign against<br />

Samos. Most surprisingly for the<br />

time, Sophocles lived to the ripe<br />

age of 90/91, finally dying in the<br />

winter of 406/405 BC.<br />

His innovations in the field of<br />

tragedy were also incredibly<br />

significant: he pioneered scenery<br />

and the use of scenes, the lack of<br />

which seems practically unthinkable<br />

in modern theatre. He also<br />

introduced a third actor, which<br />

allowed for more focus on character<br />

development and conflict; a<br />

development which also served to<br />

reduce the importance of the chorus<br />

in explaining the plot. However, he<br />

did also increase the number of<br />

chorus members to fifteen.<br />

Euripides was born in 480 BC in<br />

Salamis, about 16km west of<br />

Athens. Over the course of his life<br />

he wrote around 92-95 plays, of<br />

which around 18, potentially 19<br />

(the authorship of Rhesus being<br />

suspect) have survived. This is far<br />

more than Aeschylus and<br />

Sophocles, partly because as their<br />

popularity declined, his rose. His<br />

works were therefore produced in<br />

greater quantities. It is perhaps<br />

surprising therefore that he<br />

received far fewer victories than the<br />

others – as mentioned earlier he<br />

received only five, one of which one<br />

was awarded posthumously. His<br />

personal life was unenviable. He<br />

married twice, however both of his<br />

wives were unfaithful and the<br />

marriages ended up as disasters.<br />

This led to him becoming a societal<br />

recluse, living in a narrow cave<br />

approximately 47 metres deep on<br />

Salamis, aptly named the Cave of<br />

Euripides. Throughout his life, the<br />

conflict between Athens and Sparta<br />

took centre-stage, however he died<br />

in 406 BC at the age of 74, not<br />

living to see the ultimate defeat of<br />

Athens in 404 BC.<br />

His contributions to tragedy are<br />

vast, and for the time, revolutionary.<br />

He put a focus on realism, with an<br />

emphasis on characters’<br />

psychological insecurities, rather<br />

than the resolute heroes of prior<br />

works. He also introduced the ‘deus<br />

ex machina’ concept, turned the<br />

prologue into a monologue giving<br />

the story’s background, and<br />

diminished the choir’s importance<br />

in favour of using characters to<br />

progress the plot.<br />

“Fear? What has a man to do with fear?<br />

Chance rules our lives, and the future is<br />

all unknown. Best live as we may, from<br />

day to day.”<br />

“Tomorrow is tomorrow. Future cares<br />

have future cures, and must mind today.”<br />

“You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an<br />

idea”<br />

“To never have been born may be the<br />

greatest boon of all.”<br />

“I would rather die on my feet than live<br />

on my knees.”<br />

“Stronger than lover's love is lover's<br />

hate. Incurable, in each, the wounds they<br />

make.”<br />

“Talk sense to a fool and he calls you<br />

foolish.”<br />

“Of all creatures that can feel and<br />

think, we women are the worst treated<br />

things alive.”<br />

~26~ ~27~

Agriculture in the Roman World<br />

The biggest industry we rely on in the<br />

modern world but one which we<br />

sometimes take for granted in our day<br />

to day lives is agriculture. Farmers<br />

spend every day tending to their<br />

livestock or out in the fields looking<br />

after their crops which we then go on<br />

to eat. These methods haven’t just<br />

jumped out of thin air. We can go back<br />

two thousand years to see the roots of<br />

some of today’s farming practices.<br />

For example, today we use big<br />

machines such as tractors and forage<br />

harvesters. Tractors pull big ploughs,<br />

cultivators and trailers to get the<br />

harvest in. Farmers can be out 18<br />

hours a day in a tractor, sometimes<br />

even more when weather is an issue.<br />

Technology is at the forefront of<br />

today’s big arable and dairy farms,<br />

with GPS and automatic steering in<br />

big tractors and combine harvesters.<br />

Robots are used to milk vast herds of<br />

cows. But the Romans did it very<br />

differently.<br />

The Roman’s farmed both livestock<br />

and crops. They farmed cereal crops<br />

wheat, barley and legumes such as<br />

chickpeas and alfalfa (used as animal<br />

feed). Other crops such as turnips and<br />

radishes were also grown by the<br />

Romans, with olives, grapes and fruit<br />

trees, suited to the Mediterranean<br />

climate, being grown. Livestock such<br />

as cattle and pigs were fattened for<br />

meat, and sheep were kept for wool.<br />

Roman holdings were often as little as<br />

one and a half acres, with most farms<br />

relying on hand tools to prepare fields<br />

for crops. These included pickaxes<br />

and hoes with bronze or iron edges.<br />

However, larger farms with vineyards<br />

of olives or grapes could take up areas<br />

of up to 150 acres, since farmers were<br />

encouraged to produce large<br />

quantities of these expensive crops for<br />

oil and wine, rather than producing<br />

cereal crops in excess. Ox were used<br />

to pull ploughs and carts on these<br />

larger farms, rather than exclusively<br />

using hand tools.<br />

To prepare fields for planting seeds, a<br />

plough would be pulled along by an<br />

ox, with someone following behind<br />

with a pickaxe in order to break up any<br />

lumps of soil in the row left behind.<br />

Someone would then drop seeds into<br />

the row by hand. This process would<br />

be done two or three times a year for<br />

land which would grow wheat or other<br />

cereal crops. After this, dung would be<br />

spread by hand after the second time<br />

the field was ploughed. Water would<br />

then be added for the dung to rot<br />

down quickly.<br />

A system called the crop-and-fallow<br />

system, where a field would only have<br />

a crop grown and harvested in it every<br />

other year, was used. In the year where<br />

the field would lie fallow, the field<br />

would be ploughed in order to control<br />

weeds which commonly grow in<br />

cereal ground. For crops to grow well,<br />

trenches would be dug in wet ground,<br />

to improve the drainage of the soil in<br />

order for it to remain fertile so crops<br />

could have high yields. The Romans<br />

judged the quality of the soil based on<br />

its colour, taste, smell and texture. This<br />

would determine its suitability for<br />

growing certain crops.<br />

Harvest was carried out using a sickle,<br />

a curved metal tool for cutting the<br />

plants. There were different methods<br />

of obtaining the crop from the plant.<br />

Sometimes only the ear of the plant<br />

was cut off for cereal crops, the part<br />

containing the grains. The straw would<br />

then be cut later. Similarly to today,<br />

they also cut the whole plant and then<br />

threshed the grain. In Gaul, they used<br />

a tool called a reaper, pulled through<br />

the crop by an ox, cutting the ears of<br />

the plants as it went. A simple process<br />

was used to thresh the grains from the<br />

plants: animals walked over the<br />

harvested plants, crushing the ears<br />

and removing the grains. Grass and<br />

alfalfa were also harvested for hay to<br />

feed livestock using a sickle by cutting<br />

the whole plant.<br />

While these methods may seem farfetched<br />

in terms of modern farming,<br />

these were crucial for the<br />

developments we have seen today.<br />

The basic premises behind how the<br />

tools are used can be seen on a much<br />

larger scale today. Our sustainable,<br />

environmentally friendly British farms<br />

would be far from where they are now<br />

without the Romans.<br />

Andrew, Lower Sixth Form<br />

~28~ ~29~

Art in Ancient Greece<br />

expression of creativity rather than something functional or mundane.<br />

Ioan, Lower Sixth Form<br />

The Geometric Age took place from<br />

around 700-900 BC, and some early<br />

examples of pottery survive from this<br />

era. Work from this era is defined by<br />

geometric and linear patterns, with<br />

repeating motifs. The designs were<br />

very simplistic, as the Geometric Era is<br />

considered to be the ‘dark age’ of<br />

Ancient Greek history. Therefore, little<br />

outside influence from different<br />

cultures affected the art made in<br />

Ancient Greece, which was commonly<br />

basic and functional. Near the end of<br />

this era, signs of change could be<br />

seen through the first depictions of<br />

people in pottery. In their infancy,<br />

these images were generally simplistic<br />

and abstract, with few facial features<br />

and lines used to represent hair. As<br />

the Greeks began to interact with<br />

more diverse cultures, these<br />

depictions would become more<br />

complex and varied.<br />

The Archaic Age took place between<br />

around 800-480 BC. During this time<br />

the Greek population significantly<br />

increased as the empire expanded,<br />

and this change was reflected in the<br />

more varied art forms present during<br />

the archaic age. Greek trade in Egypt<br />

led to the introduction of kouros<br />

figures, which were life-size human<br />

sculptures commonly used as burial<br />

markers. Some Greek kouros figures<br />

corresponded exactly to idealised<br />

Egyptian rules about the proportion of<br />

human figures, showing how outside<br />

influence from different cultures<br />

helped Ancient Greek art to develop.<br />

Later in the Archaic Age, a cultural<br />

boom in Athens led to the<br />

development of red figure pottery, a<br />

technique which allowed more<br />

complex images to be depicted on<br />

vases. Art now became more focused<br />

on the depiction of the human body, a<br />

trend which would continue<br />

throughout Ancient Greece.<br />

From around 500 bc until around 350<br />

bc, the Classical Age brought about a<br />

shift in the purpose of art. Sculptures<br />

now focused on portraying a highly<br />

realistic image of the ideal human<br />

body. In addition, as the art of<br />

sculpture became more refined,<br />

people were portrayed in more<br />

naturalistic and athletic poses,<br />

whereas the upright stature of the<br />

kouros sculptures went out of fashion.<br />

From around 450 Bc, artists in Ancient<br />

Greece began to depict public figures<br />

such as politicians for the first time,<br />

showing how far art forms had<br />

progressed, as artists were now able<br />

to produce realistic imitations of reallife<br />

people.<br />

The Hellenistic Age saw the rise of<br />

realism in art. From around 320 to 30<br />

bc, the focus of art in Ancient Greece<br />

shifted towards realistic depictions of<br />

what the artist could see, rather than<br />

idealistic interpretations. Because of<br />

this, everyday people started to<br />

appear in sculptures and other<br />

artwork. At this stage, the Greek<br />

empire had reached its peak under<br />

Alexander the Great, meaning that<br />

Greece became an epicentre of<br />

culture. Artists became known in their<br />

own right for the first time and were<br />

able to extend their talents. Largescale<br />

sculptures depicting battle<br />

scenes and mythical stories became<br />

popular, as artists tried to capture<br />

emotions of passion through their<br />

work. In this age, art became closer to<br />

what we think of it today; an<br />

~30~ ~31~

Rome before the Romans: The<br />

Tale of the Etruscans<br />

Every civilisation starts somewhere.<br />

From new to old, every society starts<br />

off small, but with time learns to grow<br />

and adapt to new conditions with new<br />

enemies and new friends. Such was<br />

also the story of one of the influential<br />

societies in history – the Romans. For<br />

them, this meant expanding from their<br />

base in ancient Latium, eventually<br />

conquering the Italian peninsula, and<br />

further the Mediterranean. However,<br />

the Romans were not the first society<br />

in Italy – an older people had<br />

established a wide presence,<br />

stretching from the Po Valley to<br />

Naples, despite being cultural and<br />

linguistic unintelligibles. Such a tale<br />

was the tale of the Etruscans.<br />

The Etruscans are believed to have<br />

first properly established themselves<br />

as a permanent society around 900BC,<br />

remaining until 500BC with the<br />

growing Roman Republic taking<br />

centre stage instead. Naturally, if the<br />

origins of the Romans are explored, so<br />

must the Etruscans’. Turning to Greek<br />

and Roman authors given the lack of<br />

longer texts in Etruscan itself, most<br />

agreed that the ancestors of the<br />

Etruscans migrated from an area<br />

nearby Greece or western Turkey<br />

today. Regardless of the migratory<br />

route, the Etruscans remained in Italy,<br />

where the earliest Etruscan culture –<br />

the Villanovan culture – developed,<br />

beginning in 900BC. Characterised by<br />

advances it made in metalwork on the<br />

peninsula, the use of idiosyncratic<br />

double-cone shaped urns for the<br />

cremated and rectangular housing,<br />

the culture served as the basis of early<br />

Etruscan society.<br />

Not dissimilar from other cultures,<br />

however, Etruscan society utilised a<br />

general societal structure, with the<br />

government as the central authority<br />

with the overarching power.<br />

Accordingly, it often presented itself<br />

as such, with sub-roles such as<br />

magistrates furthering its political<br />

position, although the responsibilities<br />

of the varying types of magistrates are<br />

unclear. In part, such a system<br />

influenced the foundations of Rome as<br />

a state later on. Similarly, a strong<br />

military accompanied the established<br />

government. Continuing long military<br />

tradition, Etruscan warfare involved<br />

summer campaigns, raiding of<br />

neighbouring areas, attempts to gain<br />

territory and fighting piracy. Soldiers<br />

were held in high regard, with enemy<br />

ransoms often paid for by families.<br />

Unsurprisingly, family in ancient<br />

Etruria also tended towards the ideals<br />

of aristocracy and status, like the<br />

counterpart Roman concept of gens.<br />

Concurrently, despite encouraging a<br />

misunderstanding of Etruscan women<br />

by Greeks, nudity in art incentivised<br />

some to move away from feminine<br />

expectations, an uncommon<br />

development for an ancient society.<br />

Another binding factor of<br />

communities is religion, an aspect of<br />

culture the Etruscans were also<br />

invested in. As firm believers in<br />

immanent polytheism, the prevailing<br />

belief held was that everything visible<br />

in the world simply represented a<br />

form of manifested divine power,<br />

where such power was held by deities<br />

who were able to influence events in<br />

the human world. A complex<br />

viewpoint, figures Tages and Vegoia<br />

would act as initiators in guiding one<br />

to understand and work with said<br />

deities, while three other levels of<br />

deities formed the remainder of the<br />

religious hierarchy: earthy concepts<br />

like Catha (the sun), above whom were<br />

figures such as Tinia (the sky), as well<br />

as the third, foreign element of<br />

borrowed gods from Greek and early<br />

Roman mythology such as familiar<br />

Aritimi (Artemis) or Menrva (Minerva),<br />

reiterating the level of contact with<br />

nearby cultures Etruscan society<br />

experienced despite an isolated<br />

beginning.<br />

A final aspect of Etruscan uniqueness<br />

is also identifiable in the language. As<br />

opposed to the Indo-European nature<br />

of the surrounding Italic languages<br />

and Ancient Greek, Etruscan is<br />

classified as a language isolate,<br />

whereby no other known language<br />

resembles it enough as to form any<br />

greater family or relationship. On the<br />

contrary, a Tyrsenian linguistic family<br />

has been proposed in light of alleged<br />

similarities with the other regional<br />

languages of Raetic and Lemnian,<br />

though such a proposal has not<br />

gained widespread support.<br />

Nevertheless, with Italy acting as the<br />

main hub for use of the language, a<br />

distinct Etruscan script was developed<br />

based on the Euboean Greek<br />

alphabet, an important historical event<br />

given the Latin alphabet’s later<br />

descent from the Etruscan.<br />

Notwithstanding, Etruscan retains<br />

complicated syntactic features such as<br />

agglutination, as well as an unusual<br />

adjective system, leading to its<br />

incomplete decipherment, in part due<br />

to the loss of major Etruscan literary<br />

texts. Despite this, the linguistic<br />

influence of Etruscan is still visible<br />

today, with several words in English<br />

ultimately deriving from the language<br />

such as person, belt, or military itself,<br />

in addition to several hundred words<br />

in Latin in a similar way.<br />

In conclusion, Etruscan society did not<br />

reach the height of power and riches<br />

the later Roman Republic saw, but its<br />

historical importance as Rome’s nearqualified<br />

predecessor cannot be<br />

disputed, despite attempts by<br />

pseudo-theological Roman authors in<br />

constructing a glorified Trojan origin<br />

myth. Such an importance is still felt in<br />

the English language today, with the<br />

question not being whether the<br />

Etruscans should be remembered, but<br />

rather how they are to be<br />

remembered.<br />

Elion, Lower Sixth Form<br />

~34~ ~35~

Nero<br />

On the 11th of October, pupils<br />

ranging from the Fourth to Sixth form<br />

had the opportunity to visit a<br />

fascinating exhibition of Nero at The<br />

British Museum, which gave an<br />

informative look into the life of this<br />

controversial Emperor and challenged<br />

our preconceived ideas of him. Was<br />

this the emperor who murdered his<br />

own mother, kicked his wife to death<br />

during pregnancy and thought himself<br />

the greatest artist and performer? Or<br />

was this the emperor who built<br />

numerous buildings for the welfare<br />

and entertainment of the people, gave<br />

refuge within his private gardens to<br />

ordinary Roman citizens during the<br />

great fire and who was so loved by the<br />

people that, even decades after his<br />

unbelieved suicide, numerous false<br />

Nero’s appeared who each gained a<br />

massive popular following? While the<br />

exhibition did not give a definitive<br />

answer, it drew upon the latest<br />

research and depicted Nero as a<br />

populist in the changing times of<br />

Rome.<br />

Since Nero was decreed damnatio<br />

memoriae (meaning that the<br />

government condemned the memory<br />

and all traces of him), many statues<br />

and depictions of him had been<br />

altered or destroyed. However, the<br />

exhibition provided a rare chance to<br />

observe some of the few remaining<br />

statues and replicas of them. One<br />

particularly important statue depicts<br />

Nero as a young boy, 13, showing all<br />

the promise of a responsible and<br />

handsome man. Since Nero came to<br />

the throne at the age of 16, the statue<br />

really emphasises the heavy burden<br />

that this young child must have had,<br />

but also his immense potential.<br />

Following on from Nero's youth, there<br />

were a multitude of statues showing<br />

Agrippina, his mother and wife of the<br />

previous emperor Claudius, made in<br />

many different precious materials such<br />

as bassanite black stone. Agrippina<br />

was said to have murdered Claudius<br />

with a bowl of poisoned mushrooms<br />

to allow Nero to become emperor. It is<br />

widely believed that she held massive<br />

influence and control over Nero,<br />

eventually leading him to resent and<br />

then kill her.<br />

Leading away from the royal statues,<br />

the exhibition contained paintings of<br />

the theatre, a dominant aspect of<br />

Nero's life, as well as silver treasures<br />

from Moregine and decorations from<br />

Nero's own palaces.<br />

Students finished the day by spending<br />

some quality time in Trafalgar Square<br />

and enjoying the paintings in The<br />

National Gallery, some of which were<br />

heavily inspired by classical<br />

architecture and literature. In all, it was<br />

a very enjoyable and informative day<br />

from which we all gained an insight<br />

into those ancient times and that<br />

notorious emperor, Nero.<br />

Seb, Fifth Form<br />

~36~ ~37~

Introducing Comparative Philology:<br />

Dr Tom McConnell<br />

Earlier this year, the Hylocomian Society was proud to welcome back to St Albans<br />

Dr Tom McConnell as a guest speaker, our first in-person speaker after many<br />

months of Teams and Zoom based events.<br />

Dr McConnell is no stranger to the school, having been taught by Mrs Ginsburg,<br />

Mr Rowland and Mr Davies before embarking on his academic career. He began<br />

his journey after leaving the School by completing his degree in Classics at the<br />

University of Exeter before doing his Masters and researching his DPhil at the<br />

University of Oxford. He currently lectures at Oriel College and for the Classics<br />

Faculty.<br />

He gave us an introduction to the fascinating topic of comparative philology,<br />

beginning with an explanation of the complex family tree of Indo-European<br />

languages. Just as we are familiar with the modern Romance languages (French,<br />

Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian and Catalan) being derived from Latin,<br />

many languages, ancient and modern, widely spoken and more obscure, can be<br />

traced back to their common ancestor, Proto Indo-European. The family tree is<br />

represented in geographical terms and ranges from the Celtic languages<br />

including Old Irish, Welsh and Breton, to Tocharian, the most easterly of the<br />

family, originating in China. Dr McConnell described how a study of ancient and<br />

modern languages allows us to understand two key facets; morphology, or how<br />

languages are formed, especially their cases, and phonology which focuses on<br />

the sound of languages. When morphology and phonology correlate with<br />

meaning, it gives us the tools to reconstruct earlier languages.<br />

From this point we focused on how a smaller set of languages might be<br />

compared to understand its antecedents, which demonstrates how languages<br />

interrelate into a family tree. Everyday words in modern English, German and<br />

Dutch can be set side by side to deduce how their commonalities might point to<br />

moments of earlier development. For example, the English ‘water,’ the German<br />

‘Wasser’ and the Dutch ‘water’ are clearly similar and suggest a correspondence<br />

between the English ‘t,’ the German ‘ss’ and the Dutch ‘t.’ Analysis suggests the<br />

Proto-West-Germanic language which preceded these used ‘t’ for that consonant.<br />

This method can be developed further to understand how the ancient languages<br />

of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and modern English can be used to reconstruct their<br />

ultimate ancestor, Proto-Indo European. An example of this is the word ‘brother,’<br />

which is b’ratar in Sanskrit, ‘frater’ in Greek, ‘frater’ in Latin and may be<br />

reconstructed in a simplified way to be ‘b’rater’ in Proto-Indo European. We know<br />

that these commonalities are not chance alone since, if we apply the same<br />

method to Romance languages, we reconstruct Late Vernacular Latin.<br />

Dr McConnell’s lecture shed light on the fascinating reasons behind some of the<br />

similarities we often notice when learning Latin and Greek but, perhaps even<br />

more interestingly, it raised questions which are as yet unanswered, for example<br />

the placement of the Minoan and Mycenaean scripts, Linear A and Linear B: there<br />

are still many linguistic mysteries to be explored.<br />

Jonathan, Fifth Form<br />

Image Credit: Minna Sundberg<br />

~38~ ~39~

National Gallery Trip Review<br />

Figure 1<br />

After the engaging trip to the British<br />

Museum, where twenty-one Classics<br />

students discovered more about the<br />

life of Emperor Nero, we travelled to<br />

the National Gallery to view some of<br />

the most beautiful and historic<br />

paintings by the Renaissance and<br />

Baroque artists: Titian and Rubens.<br />

With about an hour to look at the<br />

great array of paintings, there were a<br />

few which were especially interesting,<br />

whilst also linking to the Roman era.<br />

For example, The Death of Actaeon by<br />

Titian [Figure 1] is inspired by<br />

Metamorphoses by Ovid. This was one<br />

of Titian’s paintings in which he<br />

produced large-scale mythological<br />

works for Prince Philip of Spain. In this<br />

painting, Actaeon is shown in the<br />

process of his transformation into a<br />

stag; he has a human body but a<br />

stag’s head. Titian makes this type of<br />

painting even more unusual in Italian<br />

art when he shows Actaeon being torn<br />

to death by his own hounds. This is<br />

thought to be one of Titian’s final<br />

works, as he was still working on it in<br />

his mid-eighties.<br />

Aurora abducting Cephalus by<br />

Rubens [Figure 2] is also particularly<br />

fascinating and represents another<br />

book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses:<br />

Aurora and Cephalus, in book 7. Both<br />

the painting and the poem describe<br />

the enthusiasm and desire of Aurora,<br />

the goddess of the dawn, and<br />

Cephalus to go away with each other.<br />

Rubens successfully portrays this<br />

eagerness of Cephalus and Aurora<br />

with their outstretched arms. However,<br />

in Book 7 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses,<br />

Cephalus remains faithful to his wife<br />

Procris, and does not leave with<br />

Aurora. A striking aspect in this<br />

painting is the way in which Rubens<br />

has depicted Aurora as a very human<br />

goddess, thanks to the sturdy legs and<br />

strong, powerful arms. Interestingly,<br />

this painting was influenced by the<br />

other painting discussed above, The<br />

Death of Actaeon. The specific link<br />

between the two paintings is the way<br />

in which both artists painted humanlike<br />

features. Rubens was greatly<br />

influenced by the human form of<br />

Diana, the goddess of the hunt, in<br />

Titian’s The Death of Actaeon, and so<br />

painted Aurora in a similar style.<br />

To conclude, the Hylocomian trip to<br />

the National Gallery in October was an<br />

engaging experience. We had the<br />

great opportunity to learn more about<br />

the Roman era through Titian’s and<br />

Rubens’ remarkable and beautiful<br />

paintings. This extra knowledge and<br />

context have both inspired and<br />

helped all of us with our Classics<br />

studies.<br />

Peter, Fifth Form<br />

Figure 2<br />

~40~<br />

~41~

‘A View from the Bridge’ and the<br />

Use of Chorus in Modern Tragedy<br />

When we think of tragedy, we tend to<br />

think of Aristotle’s definitions of Greek<br />

Classical tragedy, set out in his Poetics.<br />

While many subsequent plays might<br />

be considered tragic in terms of their<br />

plot, when American dramatist Arthur<br />

Miller wrote A View from the Bridge,<br />

he consciously modelled his play on<br />

the Classical Greek models. His tragic<br />

hero, however, is not a significant<br />

figure, but a lowly, ordinary working<br />

man. Eddie Carbone is a docker<br />

unloading ships in New York. In his<br />

‘clean, sparse, homely’ apartment he<br />

enjoys a cosy, loving family life; the<br />

opening of the play’s action gives little<br />

indication of the tragedy to come.<br />

However, the audience is already<br />

aware, because Miller uses a Chorus.<br />

The ancient Greek playwrights used a<br />

Chorus, a group of actors who danced<br />

and sang, interpreting the action,<br />

guiding the audience’s response,<br />

filling in parts of the story and reacting<br />

to events on stage. A View from the<br />

Bridge is not a musical – there is no<br />

group of singers and dancers. Instead,<br />