Merdeka by Chris Moorhouse sampler

Merdeka (Indonesian; Malaysian): ‘independent’ or ‘free’. ‘Merdeka’ became Indonesia’s national battle-cry and salute during its fight for independence from the Dutch Empire in the 1940s. Indonesia: a state formed of over 17,000 islands, Indonesia was under Dutch control for nearly 200 years until it declared independence in 1945 under President Sukarno. This is the previously untold story of Tom Atkinson – soldier, political speech writer, farmer, hotelier and publisher. At the core of Indonesia’s fight for independence in the 1940s, Tom contributed to the release of Indonesia from centuries of colonial oppression. After being stationed in Indonesia during WWII in the RAF, he founded the Indonesian Information bulletin and was later President Sukarno’s speech writer for over a decade. Both a political commentary and a love story, Merdeka casts a new light on the formation of a nation, following Tom through the Second World War to his time in post-war Indonesia, then his return to the UK.

Merdeka (Indonesian; Malaysian): ‘independent’ or ‘free’. ‘Merdeka’ became Indonesia’s national battle-cry and salute during its fight for independence from the Dutch Empire in the 1940s.

Indonesia: a state formed of over 17,000 islands, Indonesia was under Dutch control for nearly 200 years until it declared independence in 1945 under President Sukarno.

This is the previously untold story of Tom Atkinson – soldier, political speech writer, farmer, hotelier and publisher. At the core of Indonesia’s fight for independence in the 1940s, Tom contributed to the release of Indonesia from centuries of colonial oppression. After being stationed in Indonesia during WWII in the RAF, he founded the Indonesian Information bulletin and was later President Sukarno’s speech writer for over a decade.

Both a political commentary and a love story, Merdeka casts a new light on the formation of a nation, following Tom through the Second World War to his time in post-war Indonesia, then his return to the UK.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

chris moorhouse is a Yorkshire man <strong>by</strong> birth. After gaining a chemistry<br />

degree, he worked as an analytical chemist for ten years then in the computer<br />

industry before moving to Ayr, Scotland, in 1999 and working in a bookshop.<br />

Currently living in Bicester, Oxfordshire, <strong>Chris</strong> is helping to educate his two<br />

young grandsons to be book lovers.

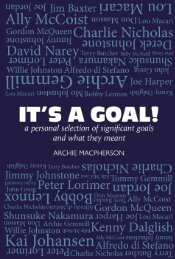

<strong>Merdeka</strong><br />

One Man’s Fight to Free a Nation<br />

from Colonial Oppression<br />

CHRIS MOORHOUSE

First Published 2019<br />

isbn: 978-1-910745-88-5<br />

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the<br />

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.<br />

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine<br />

pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.<br />

Printed and bound <strong>by</strong> Ashford Colour Press, Gosport<br />

Typeset in 11 point Sabon <strong>by</strong> Lapiz<br />

© <strong>Chris</strong> <strong>Moorhouse</strong> 2019

Dedicated to Rene Atkinson

Contents<br />

Acknowledgements9<br />

Timeline11<br />

Introduction15<br />

Part 1 The Johan van Oldenbarneveldt 1944–517<br />

Part 2 Batavia: Dutch East Indies 1945–6 58<br />

Part 3 Indonesian Office, London 1946–53 140<br />

Part 4 Jakarta, Indonesia 1953–60 169<br />

Part 5 Ardnamurchan Peninsula, Scotland 1960–9 186<br />

Part 6 Washington 1973–80 200<br />

Part 7 Pembrokeshire and The Good Life 1970–80 220<br />

Part 8 Barr, Scotland and Luath Press 1980–2000 231<br />

Part 9 Napiers 1988– 255<br />

Part 10 Alloway and Retirement 2000–2017 261<br />

Appendices265<br />

7

Acknowledgements<br />

with grateful thanks to Jan McHale for her help and encouragement.<br />

Thank you to Alice Latchford for her helpful suggestions, and to Gavin<br />

MacDougall at Luath Press for giving me the opportunity to publish this<br />

biography of two remarkable people. Thanks also to my wife, Anthea, for<br />

always being there to support me.<br />

9

Timeline<br />

1922 30 August 1922 Tom Atkinson born in Consett,<br />

County Durham<br />

11 October 1922 Rene Box born in Finchley<br />

1936 Tom Atkinson, at age 14, went to<br />

Spain to enlist in the international<br />

brigade but was sent home as he was<br />

too young to fight in the Spanish<br />

Civil War<br />

1939–45 28 July 1941 Tom Atkinson enlists into the RAF<br />

13 July 1943 Rene Box enlists into the WAAF<br />

7 June 1944 Tom Atkinson lands on Normandy<br />

beach as part of D-Day invasion<br />

12 December 1944 Tom Atkinson and Rene Box board<br />

the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt<br />

bound for India<br />

17 August 1945 Indonesia declares independence<br />

13 October 1945 Tom Atkinson arrives in Batavia<br />

1946–53 5 August 1946 Tom Atkinson demobbed from RAF<br />

23 January 1947 Rene Box demobbed from WAAF<br />

25 March 1947 The Linggadjati Agreement is signed<br />

April 1947<br />

Tom Atkinson marries Rene Box in<br />

Finchley<br />

1947 Subandrio arrives in uk as<br />

Representative of Republic of<br />

Indonesia<br />

1947 Tom and Rene Atkinson move to<br />

London to help run Indonesian Office<br />

1949 Netherlands Government agrees to<br />

transfer state control of Indonesia to<br />

the local government<br />

11

merdeka<br />

1950 Rene Atkinson starts work for<br />

Eastern World<br />

1950 Indonesian Embassy opens in<br />

London and Subandrio becomes<br />

Indonesian Ambassador to uk<br />

27 September 1950 The Republic of Indonesia joins the<br />

United Nations<br />

1952–60 1952 Tom and Rene Atkinson move to<br />

Jakarta<br />

April 1955 Bandung Conference<br />

May 1956 Tom accompanies President Sukarno<br />

on a state visit to the United States;<br />

a trip which included Sukarno’s<br />

famous speech in San Francisco,<br />

written <strong>by</strong> Tom<br />

1960–9 Tom and Rene Atkinson run hotel in<br />

Ardnamurchan peninsula, Scotland<br />

1962 Tom accompanies President Sukarno<br />

to the United Nations 17th General<br />

Assembly<br />

1965 Future president Suharto overthrows<br />

President Sukarno<br />

1969–80 1969 Tom and Rene Atkinson sell hotel<br />

and move to Bexleyheath<br />

1970 Tom and Rene Atkinson move to<br />

Pembrokeshire<br />

21 June 1971 Sukarno dies<br />

1973–80 Tom Atkinson working for Diamantidi<br />

1980–2000 1980 Tom and Rene Atkinson move to<br />

Barr, Scotland<br />

12

timeline<br />

1981 Tom and Rene Atkinson start Luath<br />

Press<br />

1982 Year of Living Dangerously film<br />

released<br />

1990 Napiers reopens in Edinburgh<br />

1995 Tom and Rene Atkinson invited to<br />

Indonesian 50th year celebrations at<br />

London Embassy and in Jakarta<br />

1997 Tom and Rene Atkinson retire from<br />

Luath Press<br />

21 May 1997 Suharto resigns the presidency<br />

2000– 2000 Tom and Rene Atkinson move to<br />

Alloway<br />

26 June 2007 Tom Atkinson dies<br />

4 August 2017 Rene Atkinson dies<br />

13

Introduction<br />

i first met tom atkinson in 2003 when I was working for Ottakar’s<br />

bookshop in Ayr. I helped Tom launch his latest book, Napiers History of<br />

Herbal Healing, Ancient and Modern. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until after his<br />

death, whilst talking with his widow, Rene, that I realised what a remarkable<br />

life Tom had lived and how deeply he had been involved in helping Indonesia<br />

gain independence from the Dutch.<br />

Tom, a member of an RAF Commando Unit, first landed in Indonesia<br />

in 1945 as part of a British occupying force designed to help the Dutch regain<br />

colonial control of what they called the Dutch East Indies. Tom contacted<br />

the leaders of the Indonesian fight for independence. Having just fought in<br />

the Second World War to ensure freedom, and risking court martial, Tom<br />

felt it was his duty to help the Indonesian People. This he did, <strong>by</strong> helping<br />

to broadcast to the world what was happening in Indonesia. This helped<br />

change world opinion and, thus, forced the Dutch to eventually agree to<br />

independence.<br />

After demob, Tom worked for the Indonesian Government, firstly in<br />

their Embassy in London and then in Indonesia. Whilst living and working<br />

in Jakarta, he travelled the world with President Sukarno and, for nearly ten<br />

years, wrote all the speeches that Sukarno gave in the English language.<br />

At this point, I realised just how instrumental Tom was in helping<br />

Indonesia gain independence, which was generally unknown outside of his<br />

family and close friends. That a British man was so important to the growth<br />

of a new country on the other side of the world is information that should,<br />

I believe, be in the public domain.<br />

My view was strengthened when Rene mentioned that, after Indonesia,<br />

she and Tom had run a hotel in the Ardnamurchan peninsula in northern<br />

Scotland, had lived ‘the good life’ in Wales, and founded Luath Press. It<br />

had also become obvious that any writing about Tom Atkinson’s life had to<br />

include Rene. Their deep, and long lasting, love was a driving force behind<br />

this story.<br />

15

merdeka<br />

As it was not possible to talk with Tom, my information had to come<br />

from other sources.<br />

A series of interviews with Rene Atkinson gave the broad outline of their<br />

life, together with much detail about certain parts.<br />

Tom was an avid letter writer and, whilst separated from Rene, wrote<br />

multi-page letters almost every day. A large part of these letters describes<br />

Tom’s love for Rene, and discusses their future life together. But Tom also<br />

wrote down in detail what he was doing, what his thought processes were,<br />

and who he was meeting with. Thus, much of the detail about Tom’s life<br />

comes from within these hundreds of letters.<br />

Tom also left copies of several audio tapes. One is an interview <strong>by</strong> an<br />

Indonesian journalist working for the BBC and covers Tom’s time in Indonesia.<br />

Tom produced a few tapes for Professor Tim Lindsey at the University of<br />

Melbourne also detailing his involvement with Indonesia.<br />

Whilst I would have loved to interview Tom, I do believe most of the<br />

relevant details of Tom and Rene’s life are included in this book. It is a<br />

truly remarkable story of two amazing people. I feel privileged to have<br />

known them.<br />

16

Part 1<br />

The Johan van Oldenbarneveldt<br />

1944–5<br />

corporal tom atkinson had never seen a large ship up close until he<br />

marched along a Liverpool quay on 12 December 1944. The ship moored<br />

there, one of many such large ships, was called the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt.<br />

Tom was part of a contingent of 4,000 men and 200 WAAFs who were<br />

destined to set sail, in convoy, for the Far East. Soon after embarking on<br />

the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt, Tom felt the vibrations as the main engines<br />

fired up in preparation for sailing. Almost immediately, there was a loud<br />

bang, later discovered to be caused <strong>by</strong> a blown piston in the main engines,<br />

and the engines stopped. Repairs started, but the men and the WAAFs were<br />

kept on-board ship until she eventually sailed – alone, as the convoy was<br />

long gone – on 21 December 1944, bound for Bombay.<br />

[NOTE: The convoy was most likely OS.98/KMS.72, which departed<br />

Liverpool on 13 December 1944 and consisted of 48 merchant ships, and<br />

three escort vessels.]<br />

The forthcoming voyage was destined to change the course of Tom’s life<br />

in ways he could never have imagined.<br />

Tom and his best friends, Peter Humphries and Alan ‘Mac’ McQuillan,<br />

were part of the RAF Commando Force, their unit being designated 3210 SC.<br />

The journey on the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt was almost certainly the<br />

most important voyage of Tom’s life. It was on board that he met the woman<br />

who was to become his wife and lifelong companion.<br />

One of the 200 WAAFs on board the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt<br />

was 22-year-old Rene Box. Rene, who came from East Finchley, was the<br />

daughter of William John Edwin Box, a shoe shop owner, and Ada Box, née<br />

Mew. Rene had two older brothers who were determined that Rene should<br />

have the education they never did.<br />

17

merdeka<br />

Rene’s eldest brother, William Thomas, unenamoured with life working<br />

in a shoe shop, had enlisted in the army. At the outbreak of the Second<br />

World War, William was in the Grenadier Guards, Second Battalion, with<br />

service number 2614268.<br />

Rene had been evacuated at the outbreak of war, and whilst evacuated<br />

she learnt that William had been killed near Caen as part of the Dunkirk<br />

withdrawal. On hearing this devastating news, Rene went home to Finchley<br />

and obtained work in a telephone exchange in the centre of London. She<br />

became more than a little bored with this lifestyle and joined the WAAFs<br />

on 13 July 1943. Rene was given different postings until volunteers were<br />

required to go abroad, whence she gratefully accepted this opportunity.<br />

It was fate that put Rene on the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt in Liverpool<br />

in December 1946.<br />

Mac remembers the meeting between the three friends and Rene:<br />

It was the first all-RAF personnel troop ship to leave England. There<br />

was nobody else, only air force people on it. About 4,000 men<br />

and 200 WAAFs. It did cause a few problems. The WAAF officers<br />

did have problems keeping them in order – there was a patrol<br />

most evenings – they used to walk around the ship and look<br />

under the lifeboats to see if they were moving. That is dead right.<br />

We played chess and music to keep the boredom at bay.<br />

Seasickness wasn’t quite so bad as it was a bigger boat than the<br />

landing craft. Mind you when we went through the Bay of Biscay<br />

there were 14 people on our table and only seven of us were<br />

eating anything. We still did rations for 14 and the seven of us<br />

that were eating ate double.<br />

The men were billeted in all parts of the boat. We didn’t<br />

have hammocks like most of them, well I didn’t have a<br />

hammock anyhow.<br />

When we were on the Johan van Oldenbarneveldt was when<br />

Tom met Rene. We met three WAAFs one of whom was Rene,<br />

and I can’t remember the names of the other two, fortunately.<br />

Of course, they got off at Colombo and we went back up from<br />

Colombo to Bombay.<br />

Rene remembers the voyage and meeting Tom:<br />

18

the johan van oldenbarneveldt<br />

I volunteered to go to India. We embarked onto the troop ship<br />

in Liverpool in December. Troops were allowed on deck, to mix<br />

at certain times of the day. Boys were down below in the hold<br />

with hammocks, and the girls were billeted in the cabins that had<br />

been converted, six bunks to a cabin. The women were privileged<br />

as we ate in the dining room, and the men had some mess room<br />

somewhere. We met on deck. There were certain hours of the day<br />

when music was broadcast on the Tannoys. We were allowed<br />

to mix, boys and girls, on a particular deck at that time. You<br />

couldn’t just wander over all the decks during the day and meet<br />

up with the boys. It wasn’t allowed.<br />

I met Tom under a Tannoy listening to classical music – The<br />

Thieving Magpie <strong>by</strong> Rossini. On deck, we got chatting. Tom<br />

and his mate were busy playing chess, and I suppose I was just<br />

watching them as we milled around on the deck with nothing to<br />

do. Finally, they said, ‘come and join us, do you want to learn<br />

how to play chess?’ And really, I can’t say it was love at first sight,<br />

but that’s where Tom and I first met, and at least got interested in<br />

each other. He was going to India and so was I.<br />

We continued to meet, during the intervals we were allowed<br />

to get together, for the two weeks of the voyage. Half way across<br />

the powers that be decided the war was really getting to an end<br />

and they didn’t need WAAFs in India. The boys would carry on to<br />

India and they would throw us WAAFs off in Sri Lanka – Ceylon<br />

as it was then called. This was devastating to Tom and I. Good<br />

Lord, we have to part. I went to Colombo as a wireless operator.<br />

Tom went onto India, to Calcutta, Bombay and all those places.<br />

For the next few months Rene and Tom’s relationship blossomed through<br />

their letters. Tom was writing to Rene almost every day with letters of five, six<br />

or even more pages. The overriding theme of all his letters was how deeply<br />

he had fallen in love with Rene, how much she meant to him and how it had<br />

changed his whole attitude to life. This is apparent from a letter Tom wrote<br />

to Rene only a couple of days after the separation, on 15 January 1945 from<br />

Bombay, an extract of which is shown below:<br />

Did I ever tell you that you are the most wonderful girl in the<br />

world and that I love you to distraction?<br />

19

merdeka<br />

Until we left the ship I spent most of my time sitting where<br />

we had so often sat, and re-living all the anxieties and ecstasies<br />

of those too few days. How I longed for you! Memories are very<br />

beautiful things, but I think that I would, then have willingly<br />

exchanged them all for one more glorious hour with you, so that<br />

I could have felt once more the wonder of your nearness.<br />

Since you left me, (oh sorrowful day!), I have been acutely<br />

miserable and only the thought that you would be just as miserable<br />

as myself has made life bearable. You see, I feel so sorry for you<br />

that I forget to feel sorry for myself.<br />

Love me always, darling, as I love you, so that our life together<br />

can be one eternal dream of peace and exquisite happiness.<br />

I have just written home and told them the news. I would love<br />

to be at home when they receive the letter so that I could enjoy<br />

their amazement. Contrary to my usual rule, I re-read the letter<br />

and I found that it was a terrible jumble of quite unconnected<br />

sentences with no sort of order behind them at all – this one is<br />

probably the same. However, it is a fair indication of how I feel<br />

and my present mental condition. It’s all your fault.<br />

This country far surpasses anything I had ever visualised.<br />

I can’t possibly begin to talk about it in this letter now and in<br />

any case, I have found it impossible so far to look at it in any<br />

reasonable sort of light. I am just watching and wondering and<br />

impressing upon my mind the broad outlines.<br />

One of the most amazing things is the capacity which<br />

everyone of us has straight away developed for fruit. So far today<br />

I have consumed fourteen oranges and eleven bananas! And Nick<br />

and Pete have done just the same. So long as the money lasts we<br />

intend to carry on in the same way because probably all too soon<br />

we shan’t be able to get any more.<br />

On 16 March 1945, only a few weeks after separation, Tom was<br />

writing to Rene:<br />

There were three letters from you today, and all of them so very<br />

lovely that I fell in love with you all over again. Not that there<br />

20

the johan van oldenbarneveldt<br />

is anything odd about that, of course, it happens every day, but<br />

somehow it seemed very special today. Possibly it was because<br />

I was looking forward to your letters so much that when they came<br />

they just released the floodgates of my love. There was something<br />

peculiar about it, something that has never happened quite the<br />

same before. I have told you before that when I read your letters<br />

you seem to be close beside me, but today you were actually in the<br />

tent sitting on the bed beside me, you ran your fingers through my<br />

hair and said, quite distinctly, ‘Tom darling, you see I’ve come to<br />

you.’ Just what it was I don’t know, and I certainly don’t wish to<br />

analyse it, otherwise I shall find myself attributing it to the sun or<br />

too much tiffin. No, something happened today, something very<br />

special and wonderful, and for the first time in my young life<br />

I don’t want a rational explanation of it. I know very little about<br />

telepathy, but maybe in the words of the lion tamer who lost his<br />

head to his pet exhibit, ‘There is something in it.’<br />

You have had this feeling twice, and (it may be important)<br />

you described one of them in a letter which I was holding when<br />

it happened.<br />

Whatever it is, I certainly hope that it happens again.<br />

Then four days later, on 20 March 1945, Tom finished a letter to Rene with<br />

the words:<br />

There has been quite a time lag between these last sentences. The<br />

char wallah has been around and of course, there had to be<br />

the usual natter over the char. Consequently, I have rather lost the<br />

thread of what I was talking about.<br />

But there is certainly one subject about which I can never<br />

lose the thread. That subject, of course, is you and me. You know<br />

the poem which begins: ‘If I should sit <strong>by</strong> some tarn in the hills,<br />

using its ink as the spirit wills, to write of earths creatures, its live<br />

willed things?’<br />

The poet said that he could exhaust the tarn writing of the<br />

wonders of the earth. I know that I could exhaust the tarn in<br />

writing about you, my dearest, for, compared with the complexity<br />

21

merdeka<br />

of all the wonders you have shown to me, earths treasures are<br />

simple and easy.<br />

You are the living incarnation of everything which I love and<br />

treasure, and without you now, life would be just not worth living.<br />

Everything about you haunts me all the time; your beautiful<br />

and trustful face, your faint-scented hair, your speaking hands,<br />

your warm soft body.<br />

You have given me your love and taken mine and we belong<br />

to each other now and for always, for the love which we both give<br />

is complete and embraces every part of our lives.<br />

Goodnight, Rene, and bless you, my darling.<br />

[NOTE: The poem is The Scribe <strong>by</strong> Walter De La Mare.]<br />

In his letters, as well as his love for Rene, Tom also described in detail<br />

his contacts with the Indian people in general, and the Indian Communist<br />

Party. He also expounded on his theories of Socialism, Religion, and the arts.<br />

At some time during this exchange of letters, Tom and Rene were talking<br />

about getting married, starting a family, and generally planning their life<br />

together. Rene wrote to her parents to tell them she had fallen in love and<br />

considered herself engaged to a wonderful boy she had met on the troopship.<br />

Her father’s comment was that she must have been ‘moonstruck on deck’<br />

and didn’t take it too seriously.<br />

***<br />

Tom was born in Consett, County Durham, on 30 August 1922. His early<br />

life was uneventful until, in 1936, at the age of 14, Tom ran away from<br />

school and travelled to Spain to fight in their Civil War. On arriving in Spain,<br />

he was immediately sent home after being told he was too young to fight.<br />

Tom was furious, but had no choice but to return home to Consett.<br />

The significance of the Spanish Civil War to Tom, and the strong ideals<br />

that he must have felt to go there and fight, indeed, his beliefs that it was<br />

essential so to do, are highlighted in his criticism of the film For Whom<br />

22

the johan van oldenbarneveldt<br />

the Bell Tolls detailed in a letter to his sister, Ada, and his brother-in-law,<br />

George, dated 5 December 1943 (Appendix 1).<br />

Rene recalls his life after returning from Spain:<br />

Tom at the age of 14 left school to go to Spain to fight. I don’t<br />

know how he got there but there were plenty of left wing people<br />

who would have helped him. He must have travelled with a group<br />

of like-minded people. In Scotland and places like Durham, Tom<br />

was in Durham at the time, there were plenty of people meeting<br />

up to travel together. All over the country there were people<br />

wanting to do the same, getting together to organise for the trip.<br />

When he got to Spain they sent him home, telling him he was<br />

too young.<br />

Tom was born a communist I think. Not influenced directly<br />

<strong>by</strong> his family, but <strong>by</strong> being born into a working-class family in a<br />

mining area. It wasn’t difficult to think that way I suppose. Tom<br />

really didn’t have the education he should have had, because he<br />

scuttled away to Spain.<br />

Between returning from Spain and the outbreak of the Second<br />

World War Tom worked in a shop in Consett. His father had been<br />

a village policeman in Cockfield and the surrounding area, and<br />

when he retired he got a very posh semi-detached, bay-windowed<br />

house at the end of a miners’ row in Consett. At that time, the<br />

main source of employment had moved away from the pits to<br />

the Iron Company. Tom worked in a grocery shop called Walter<br />

Wilsons, learning how to wrap the bacon, and slice the cheese,<br />

and everything else, until he enlisted into the RAF.<br />

Tom also became active in politics, and had become a member of the<br />

North-East section of the Communist Party (CP) of Great Britain. He was<br />

involved in its organisation, but focussed on disseminating its ideas <strong>by</strong><br />

writing numerous articles.<br />

World War Two gave Tom, like most young men of his age, the opportunity<br />

not only to demonstrate their patriotism but also the opportunity to escape<br />

the drudgery of life in a mining village and see more of the world. Having<br />

tried to fight fascism in Spain, he was obviously not going to hesitate to do<br />

so for his homeland.<br />

23

merdeka<br />

Tom joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) on 28 July 1941. After initial<br />

training, he trained to be a Wireless Mechanic at Bolton Technical College. As<br />

a sprog (a young, new, inexperienced airman), his first posting was, strangely<br />

enough, to RAF Ouston near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, which was not too far<br />

from his home of Consett. Tom had specialised in working on VHF (Very<br />

High Frequency) radio and other equipment used in ground-to-aeroplane<br />

communication. In addition, he had to learn to strip, repair, service, and put<br />

back together various types of aeroplane.<br />

Eventually, Tom found that working in the comfortable environment of<br />

the Wireless Workshop had started to become boring. The war appeared to be<br />

going on and he was nowhere near seeing any action. When the opportunity<br />

came to volunteer for something new and exciting, he jumped at it.<br />

By 1942, there were sufficient military and political leaders realising the<br />

mistakes that Britain had made during the early years of the war, whence the<br />

commanders were still very much entrenched in the tactics of the First World<br />

War. Eventually, the lessons of the highly efficient German forces, and in<br />

particular the tactics of the Blitzkrieg, were being learnt. One of these lessons<br />

was the close co-operation between the various forces – the Army, Air Force,<br />

and Navy – which was still an anathema to the individual services. The<br />

response of the Air Force was to form the Servicing Commando Unit (SCU).<br />

It was eventually realised that British Forces would have to invade<br />

and occupy mainland Europe to win the war, and, hence, there was a<br />

requirement to equip and service airfields near the battlefronts. Until this<br />

time, the mechanics of the RAF were exactly that – they were trained to<br />

service aircrafts and not as fighting troops. The German tactic of Blitzkrieg<br />

had shown the huge advantage of air support for forward troops and, to<br />

achieve this, runways had to be near the battle lines. Hence, the SCU was<br />

formed to train elite mechanics to fight at a special operations level and<br />

be near the vanguard of any invasion or major battle. Tom immediately<br />

volunteered for the SCU and shortly after was posted to RAF Coltishall to<br />

join the newly formed 3210 SC.<br />

It was at Coltishall that Tom met Peter Humphries who was to become<br />

his closest friend for the rest of the war and thereafter.<br />

The initial training for Tom’s Unit took place at an RAF base just north of<br />

the village of Zeals in Wiltshire. From opening in 1942 until August 1943,<br />

Zeals was used as a base for Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire<br />

fighter planes. In August 1943, the base was transferred to the United States<br />

Air Force.<br />

24

committed to publishing well written books worth reading<br />

luath press takes its name from Robert Burns, whose little collie<br />

Luath (Gael., swift or nimble) tripped up Jean Armour at a wedding<br />

and gave him the chance to speak to the woman who was to be his wife<br />

and the abiding love of his life. Burns called one of the ‘Twa Dogs’<br />

Luath after Cuchullin’s hunting dog in Ossian’s Fingal.<br />

Luath Press was established in 1981 in the heart of<br />

Burns country, and is now based a few steps up<br />

the road from Burns’ first lodgings on<br />

Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Luath offers you<br />

distinctive writing with a hint of<br />

unexpected pleasures.<br />

Most bookshops in the uk, the us, Canada,<br />

Australia, New Zealand and parts of Europe,<br />

either carry our books in stock or can order them<br />

for you. To order direct from us, please send a £sterling<br />

cheque, postal order, international money order or your<br />

credit card details (number, address of cardholder and<br />

expiry date) to us at the address below. Please add post<br />

and packing as follows: uk – £1.00 per delivery address;<br />

overseas surface mail – £2.50 per delivery address; overseas airmail –<br />

£3.50 for the first book to each delivery address, plus £1.00 for each<br />

additional book <strong>by</strong> airmail to the same address. If your order is a gift,<br />

we will happily enclose your card or message at no extra charge.<br />

543/2 Castlehill<br />

The Royal Mile<br />

Edinburgh EH1 2ND<br />

Scotland<br />

Telephone: +44 (0)131 225 4326 (24 hours)<br />

email: sales@luath. co.uk<br />

Website: www. luath.co.uk