A Utopia Like Any Other by Dominic Hinde sampler

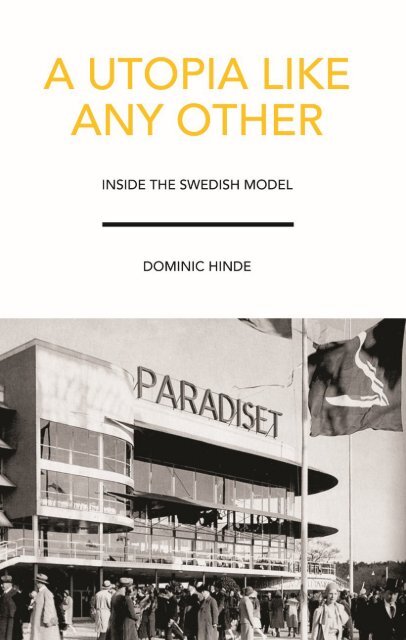

Does a utopia really exist within northern Europe? Do we have anything to learn from it if it does? And what makes a nation worthy of admiration, anyway? Since the ’30s, when the world was wowed by the Stockholm Exhibition, to most people Sweden has meant clean lines, good public housing, and a Social Democratic government. More recently the Swedes have been lauded for their environmental credentials, their aspirational free schools, and their hardy economy. But what’s the truth of the Swedish model? Is modern Sweden really that much better than rest of Europe? In this insightful exploration of where Sweden has been, where it’s going, and what the rest of us can learn from its journey, journalist Dominic Hinde explores the truth behind the myth of a Swedish Utopia. In his quest for answers he travels the length of the country and further, enjoying July sunshine on the island of Gotland with the cream of Swedish politics for ‘Almedalan Week’, venturing into the Arctic Circle to visit a town about to be swallowed up by the very mine it exists to serve, and even taking a trip to Shanghai to take in the suburban Chinese interpretation of Scandinavia, ‘Sweden Town’, a Nordic city in miniature in the smog of China’s largest city.

Does a utopia really exist within northern Europe?

Do we have anything to learn from it if it does?

And what makes a nation worthy of admiration, anyway?

Since the ’30s, when the world was wowed by the Stockholm Exhibition, to most people Sweden has meant clean lines, good public housing, and a Social Democratic government. More recently the Swedes have been lauded for their environmental credentials, their aspirational free schools, and their hardy economy. But what’s the truth of the Swedish model? Is modern Sweden really that much better than rest of Europe?

In this insightful exploration of where Sweden has been, where it’s going, and what the rest of us can learn from its journey, journalist Dominic Hinde explores the truth behind the myth of a Swedish Utopia. In his quest for answers he travels the length of the country and further, enjoying July sunshine on the island of Gotland with the cream of Swedish politics for ‘Almedalan Week’, venturing into the Arctic Circle to visit a town about to be swallowed up by the very mine it exists to serve, and even taking a trip to Shanghai to take in the suburban Chinese interpretation of Scandinavia, ‘Sweden Town’, a Nordic city in miniature in the smog of China’s largest city.

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

dominic hinde is a journalist and academic based in Edinburgh.<br />

He has studied and worked on and in Scandinavia and Sweden<br />

for a decade, including writing a phd on Swedish politics at the<br />

University of Edinburgh and a period as a visiting researcher at<br />

Sweden’s Uppsala University. In his journalistic career <strong>Hinde</strong> has<br />

reported from Scandinavia, Germany, the us, South America and<br />

Scotland as a freelance foreign correspondent for The Scotsman,<br />

Washington Times, usa Today and others. He has also worked<br />

for Danish Public Broadcasting and as a culture columnist for the<br />

Swedish news magazine Flamman. In addition to journalism,<br />

<strong>Hinde</strong> also translates plays and novels from the Scandinavian<br />

languages into English and has taught on Scandinavian culture<br />

and politics at both the University of Edinburgh and University<br />

College London. A <strong>Utopia</strong> <strong>Like</strong> <strong>Any</strong> <strong>Other</strong> is his first full book.

A <strong>Utopia</strong> <strong>Like</strong><br />

<strong>Any</strong> <strong>Other</strong><br />

Inside the Swedish model<br />

DOMINIC HINDE<br />

Luath Press Limited<br />

EDINBURGH<br />

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2016<br />

isbn: 978-1-910745-32-8<br />

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from<br />

low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emissions manner<br />

from renewable forests.<br />

Printed and bound <strong>by</strong><br />

Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow<br />

Typeset in 11 point Sabon <strong>by</strong><br />

3btype.com<br />

Image 1 sourced from Wikimedia <strong>by</strong> Self-taken, published under the<br />

terms of the gnu Free Documentation License<br />

Image 10 sourced from Wikimedia and photographed By Jordgubbe<br />

Image 6 sourced from Wikimedia and photographed <strong>by</strong> Tage Olsin,<br />

own work<br />

Images 15 and 16 photographed <strong>by</strong> Gigi Chang<br />

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the<br />

Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988 has been asserted.<br />

© <strong>Dominic</strong> <strong>Hinde</strong> 2016

Contents<br />

Foreword 7<br />

Introduction 9<br />

chapter one Everybody’s <strong>Utopia</strong> 13<br />

chapter two<br />

A Workers’ <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

How Sweden made work pay 22<br />

chapter three Democratic <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

Sweden’s diverse democracy 34<br />

chapter four A Feminist <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

How Sweden is halfway to equality 47<br />

chapter five<br />

chapter six<br />

Svennotopia<br />

The struggle for Swedishness 66<br />

Ecotopia<br />

A sustainable country in a dirty world 88<br />

chapter seven Cultural <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

How Sweden became a cultural powerhouse 106<br />

chapter eight Metropia<br />

How Sweden built its homes for people 122<br />

chapter nine<br />

chapter ten<br />

A Moderate <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

The new Swedish model 134<br />

A <strong>Utopia</strong> <strong>Like</strong> <strong>Any</strong> <strong>Other</strong><br />

How Sweden’s future is everyone’s future 147<br />

Recommended reading 159<br />

5

Foreword<br />

in the minds of anyone on the progressive side of the<br />

political spectrum, Scandinavia is always something we talk<br />

about in fond terms. Compared with a country like the uk<br />

there is much about Scandinavian politics that appears attractive,<br />

from the way it organises its democracy to its record on<br />

equality and, in the case of Sweden, a pro-active but independent<br />

foreign policy. It’s natural then that many in<br />

Scotland, and especially those of us who don’t believe that<br />

our future must forever be as part of the uk, see much to<br />

draw from as we imagine how we might run our affairs, or<br />

our position in the international community.<br />

It is very easy to use Scandinavia as a political tool, and<br />

Labour, the Scottish National Party and the Conservatives<br />

have all at different times tried to market a supposedly<br />

Nordic style of politics. Usually this approach takes advantage<br />

of the fact that, though many of us have heard about the<br />

social and economic success of the Nordic countries, few are<br />

familiar enough to do much other than cherry pick what is<br />

presented to us, often only cosmetically. When Scotland<br />

regained its Parliament in 1999 there were for example positive<br />

noises made about embracing a deliberative, multi-party<br />

approach to how we govern. It is fair to say that while a few<br />

of these ideas were realised, many were not. When pushed,<br />

none of the governing parties in Scotland or the rest of the<br />

uk have been prepared to make the shift to that more open<br />

style of politics, and although my colleagues and I have<br />

sought to introduce fairer, Nordic-inspired tax policies we<br />

have generally met with resistance. It’s often repeated, and<br />

hard to deny, that we cannot have Scandinavian levels of<br />

investment in society with American levels of taxation, but<br />

7

a utopia like any other<br />

political salesmanship has achieved a deferral of the moment<br />

when the choice must be made. It can’t put it off forever.<br />

Throughout the 20th century the Nordic countries became<br />

a model for other European left wing movements to follow,<br />

but today we find ourselves in very different circumstances<br />

to the postwar years in either the uk or across the North Sea.<br />

Few would even try to argue that building the ethnically homogenous<br />

society of 20th century Scandinavia was desirable, or<br />

even possible. But a movement of normal people pushing for<br />

social changes similar to those that forged the Scandinavian<br />

welfare states? That seems absolutely within reach.<br />

The challenge now, for politicians in Scandinavia and<br />

elsewhere, is to build a more social and more democratic<br />

society fit for the future. Perhaps at times we’re guilty of too<br />

rosy, even utopian, a view of Scandinavia. But a politics of<br />

social equity, environmental responsibility and democratic<br />

accountability is both a future worth pursuing and absolutely<br />

possible.<br />

Patrick Harvie<br />

8

Introduction<br />

this is a book about Sweden, but also about the changing<br />

world at large. It is not supposed to be a political manifesto,<br />

but neither is it devoid of politics. The book is a combination<br />

of foreign reporting, academic writing and extra material<br />

collected along the way, combined to tell a story about the<br />

Swedish model, a term familiar to a lot of people without it<br />

ever being fully elaborated upon. The period covered <strong>by</strong> the<br />

book was a time of political uncertainty and transition in<br />

Sweden, with new pressures and old problems resurfacing as<br />

part of the wider upheavals taking place across Europe. This<br />

is why this book goes well beyond contemporary Sweden; to<br />

suburban Scotland, urban China, and back to the makings<br />

of modern Scandinavia and the rise of European Social<br />

Democracy in the 1930s.<br />

The idea of producing a book first came about on a train<br />

trip from Gothenburg to Stockholm in the September of 2014.<br />

It was just after the chaos of Scottish independence referendum<br />

and the Swedish general election, a time when seemingly<br />

everyone was an expert on the Nordic countries and<br />

when ‘Swedish-style’ was the adjective of choice amongst<br />

politicians in Edinburgh looking to sell the independence<br />

project to a sometimes sceptical public. Rolling slowly through<br />

the small towns of central Sweden, in some ways idyllic but<br />

in others deeply troubled, there are many reminders that it is<br />

a far more complex country than it is often portrayed as being.<br />

This was rammed home to me in the autumn of 2015<br />

when a translated quote from a newspaper article I had<br />

written was lifted without attribution or context; it started<br />

popping up all over the internet in click-bait about how<br />

Sweden was going to become carbon neutral, the reality of<br />

9

a utopia like any other<br />

which was more complicated than most of the reporting on<br />

it would admit. Similarly, around the same time another piece<br />

did the rounds claiming that everyone in Sweden was going<br />

to work six hour days – the real story of that particular policy<br />

and how it happened is dealt with in the pages of this book<br />

– but it was something most readers were perfectly happy to<br />

believe and commented on approvingly. Shortly after, I was<br />

sat on a panel at a uk book festival where one of the other<br />

participants declared ‘the values of the Swedish people mean<br />

that all their services are publicly owned’. It was both terrifyingly<br />

essentialist (the person in question was a relatively<br />

prominent left-wing activist) and wholly untrue. It was met<br />

with nods of agreement from an audience happy to hear that<br />

somewhere there was a place better than where they were.<br />

This phenomenon, the desire to make Sweden whatever<br />

people want it to be, is everywhere and is hard to resist. As a<br />

freelance correspondent the two most bankable pitches for<br />

foreign media are to find something that shows how Sweden<br />

is miles ahead of everybody else or to report on the disintegration<br />

of a once perfect society. Often when we talk about<br />

Sweden abroad we are not interested in the country at all,<br />

but in the apparent deficiencies of ourselves and where we<br />

happen to live. On numerous occasions I have been told <strong>by</strong><br />

editors when pitching material from Scandinavia, ‘great, but<br />

this doesn’t really fit with our audience’. Telling a good story<br />

and telling the real story are not always the same thing.<br />

In the year in which most of the things that make up this<br />

book were written I travelled the country from top to bottom,<br />

visiting new places and revisiting old ones. Everywhere you<br />

go in Sweden you cannot escape the legacy of the Social<br />

Democratic movement that built the country into what it is<br />

today; it is pervasive even amongst those who are ideologically<br />

opposed to left-wing politics. The people featured within<br />

10

introduction<br />

its pages are all real, though some have had their names<br />

changed as they did not know they were going to be written<br />

about when interviewed. It is in these people’s everyday lives<br />

that the real politics exists, and where the realities and<br />

complexities of Sweden and its much admired model can be<br />

found.<br />

Reading the book it will be obvious where I have taken a<br />

lot of inspiration from, and I could not have written it without<br />

the first class Swedish journalism of both Po Tidholm and<br />

Niklas Orrenius as a guide, as well as the welfare work of<br />

Irene Wennemo. On a more direct level I have benefited from<br />

the help and inside knowledge of a raft of former colleagues<br />

in Uppsala. I am grateful to my friend and colleague Gigi<br />

Chang for her help in Shanghai, and to Lotte at Luath in<br />

Edinburgh for her assistance in putting the book together.<br />

I also owe a great amount to the late Helena Forsås Scott,<br />

Professor of Swedish and Gender Studies at ucl in London,<br />

who sadly passed away during its writing and who made a<br />

lasting impression on me and many others.<br />

There is so much about Sweden not mentioned here that<br />

deserves coverage, and some things which are best told on<br />

the tv or radio instead of on paper. Whatever happens to<br />

Sweden in the future, and however it ends up being reported,<br />

it is country that it pays to keep an eye on.<br />

Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm<br />

August 2015<br />

11

chapter one<br />

Everybody’s <strong>Utopia</strong><br />

I think we should look to countries like Denmark,<br />

like Sweden, and Norway and learn from what they<br />

have accomplished for their working people.<br />

bernie sanders<br />

it is late morning on a grey Wednesday lunchtime in the<br />

small town of Coatbridge, just to the east of Glasgow in<br />

suburban Scotland. On the high street it looks like any other<br />

day of the week; a few people mill around in the entrance to<br />

the concrete shopping centre as a man sells packs of socks from<br />

a temporary stall under the awning of a closed shop. The only<br />

places doing solid business are the asda supermarket and the<br />

turf-green illuminated Celtic fc club store directly opposite.<br />

This is not just a normal Wednesday though. Tomorrow<br />

morning Scotland is due to go to the polls to decide whether<br />

or not it should become an independent country, leaving<br />

Britain for a new life as small Northern European nation.<br />

Coatbridge is typical of the former industrial towns that ring<br />

Scotland’s largest city, and until now the closest it has come<br />

to Scandinavia are the replica shirts in the Celtic club store<br />

bearing the name of Sweden striker Henrik Larsson. Kungen,<br />

or the King as Larsson was known to his English-speaking<br />

fans, is a legend in Glasgow’s eastern suburbs. Part of Celtic<br />

mythology, he did Sweden’s reputation no damage during his<br />

Scottish stay before taking his considerable talents on to<br />

Barcelona and Manchester United.<br />

In Larsson’s footsteps comes a Scandinavian film crew,<br />

trying to find out what Scottish people think not only about<br />

13

a utopia like any other<br />

independence, but also their potential new place in a reorganised<br />

continent alongside their Scandinavian neighbours.<br />

The region has loomed large in the campaign, with meeting<br />

rooms around the country filled with talk of Nordic prosperity<br />

and new northern horizons for the North Atlantic country.<br />

In response, members of the anti-independence campaign<br />

appeared on television with scare stories of 80 per cent tax<br />

rates and dystopian state controls, arguing with proindependence<br />

voices that talked of political cooperation,<br />

Nordic peacekeeping and a cultural revival that would make<br />

Scotland as chic as the rest of the North Atlantic.<br />

In a high concrete tower block overlooking Coatbridge<br />

town centre the tv crew knock on doors looking for<br />

interviewees. People are either not home or not interested.<br />

Eventually though they find someone prepared to talk to<br />

them, a former taxi-driver turned council cleaner mopping<br />

the lino-furnished landings between floors, ten stories up in<br />

the granite grey of the Scottish morning. The tv anchor, an<br />

experienced half Swedish, half Danish woman used to trawling<br />

Europe for stories, jumps in with her initial question after<br />

some encouragement.<br />

‘Hi there, we’re filming for a Nordic television programme<br />

about the referendum and wondered if you wanted to talk<br />

about how you will vote tomorrow,’ she says with a persistent<br />

friendliness. The interviewee looks up from his mop. After<br />

some pushing he finally agrees to be filmed, and the arrival of<br />

two Swedish speaking crew gives him further encouragement.<br />

‘I think I’ll vote Yes,’ he says with some consideration.<br />

‘People are talking about it being more equal, more like<br />

Norway and Sweden and those countries.’<br />

The reporter nods away, indicating he should say more.<br />

‘It would be for the kids. You’ve got a pretty good<br />

impression of how they do things, and if Scotland could be<br />

14

everybody’s utopia<br />

more like that then it seems a good chance.’ <strong>Like</strong> many voters<br />

in Scotland, he has been reached <strong>by</strong> the ubiquitous proindependence<br />

narrative of a nation reborn as a leading light<br />

of Northern Europe. The governing Scottish National Party<br />

have been talking about a North Atlantic ‘arc of prosperity’<br />

and civic groups have been eagerly importing speakers from<br />

all over Northern Europe to talk about the country’s potential<br />

path, packing community meetings and articulating a<br />

different country from the one most Scots live in. The details<br />

however are sketchy, and the motivations range from<br />

environ mental awareness and education to gender equality<br />

and economic success. Whatever the substance, the effect is<br />

unambiguous – Scandinavia is there to be copied and admired.<br />

Brand Scandinavia has a worldwide reach far beyond<br />

Scotland’s central belt though, from members of the European<br />

left wanting to build their own social democracies to<br />

the Chinese middle class paying for mass produced designer<br />

furniture at ikea stores in Beijing, or American tv executives<br />

snapping up the rights to Nordic drama. In Scotland’s case<br />

brand Scandinavia means reinventing the country as a better<br />

version of itself along the lines of an imagined north. It is a<br />

composite vision in which Scotland could have Danish wind<br />

and Norwegian oil, Icelandic fishing and Swedish industry.<br />

For many voters in Scotland’s independence referendum<br />

their Scandinavian neighbours offered a glimpse of a more<br />

radical, less granite-grey future. In the same vein, England<br />

has been sold Swedish free schools, France has embraced le<br />

modèle suédois in its sex work policy and Democratic presidential<br />

hopeful Bernie Sanders has singled out Sweden and<br />

its neighbours as a blueprint for a new America. Neither is<br />

this love of the Nordic a new phenomenon. The Nordic<br />

countries, and Sweden in particular, have always attracted a<br />

special kind of attention from utopian dreamers. In 1796<br />

15

a utopia like any other<br />

Mary Wollstonecraft, the English feminist and political<br />

philosopher, wrote a travel diary based on her time in Scandinavia<br />

in which the region was used as a canvas for what a<br />

radical and more egalitarian Britain might look like. The<br />

book sold well and unleashed a small wave of idealistic<br />

Nordic romanticism in the people around Wollstonecraft,<br />

exploiting the fact that few had first-hand experience of the<br />

places she visited<br />

More than a century later, a then largely unknown American<br />

journalist called Marquis Childs pitched up in Stockholm.<br />

His stay would result in a work that came to shape many<br />

people’s views of what internationally became known as the<br />

Swedish Model. Sweden: The Middle Way was a bestseller in<br />

the English-speaking world upon its publication, portraying<br />

a harmonious society in which big business had been made<br />

to bow to the will of the people and enlightened Social<br />

Democratic government had led the country on a pragmatic<br />

path between the twin perils of Anglo-Saxon capitalism and<br />

European totalitarianism. Including audiences with senior<br />

politicians and the working man, The Middle Way offered a<br />

glowing appraisal of Sweden’s path from poverty to cohesive<br />

market socialism that was the polar opposite of the depression-scarred<br />

’30s United States Childs had left behind.<br />

Childs’ Sweden was populated <strong>by</strong> altruistic planners and<br />

modest politicians working for a common good in welldesigned<br />

houses and bright factories. Touring cooperative flour<br />

mills and interviewing the Prime Minister, his trip through a<br />

picturebook Sweden which combined cosy tradition with clean,<br />

modern market socialism left its mark on the British and<br />

American public. Eighty years on the narrative is remarkably<br />

similar, even if the world around has changed beyond all<br />

recognition.<br />

Despite his enthusiasm for Sweden’s political project Childs<br />

16

everybody’s utopia<br />

was not an economist and never set out to write about Sweden’s<br />

burgeoning social democracy. He had originally travelled to<br />

Stockholm to attend a housing expo but returned having<br />

discovered what seemed to be a perfect society in the making.<br />

In the cultural essentialism of the pre-war years he was able<br />

to describe Swedes as a model race imbued with ‘certain<br />

basic characteristics – patience, intelligence, perseverance,<br />

courage’, and a democracy which ‘sprang from something<br />

inherent in the nature of the people.’ At the same time as the<br />

Swedish model was painted as an example for others to<br />

follow, Swedes were granted an exceptional position in an<br />

idealised pastoral socialism straight from the pages of a<br />

propaganda pamphlet.<br />

The expo that Childs set out to cover was also anything<br />

but typical of the country it was in. Staged with considerable<br />

effort on the part of its organisers, the Stockholm Exhibition<br />

of 1930 was intended as an exercise in aspiration and utopian<br />

modernism that had yet to reach out beyond Sweden’s cities.<br />

Allan Pred, an American geographer who became one of the<br />

most nuanced commentators of Sweden’s global image,<br />

summarised the entire Stockholm Exhibition as nothing less<br />

than an elaborate attempt to market Sweden abroad.<br />

Different pavilions at the exhibition documented Swedish<br />

achievements and Swedish Ambitions in technology and the<br />

arts. One of the main drivers behind the entire project was<br />

Gunnar Asplund, who was to become synonymous with the<br />

clean and bright image of modern Sweden. In fact at the<br />

centre of the Stockholm exhibition was an Asplund-designed<br />

restaurant with the word Paradiset – Swedish for paradise –<br />

emblazoned on its front. As long as the temporary exhibition<br />

lasted it offered a glimpse of Swedish utopia made real, with<br />

politics meeting design and culture in an alluring crystalline<br />

vision of a forward-looking, clean, and altogether better world.<br />

17

a utopia like any other<br />

Three decades later, another journalist landed in Stockholm<br />

to find out about the modern Swedish miracle that<br />

Childs had uncovered. David Frost is better known to the<br />

wider world as the man who would engineer an interview<br />

with the disgraced Richard Nixon after the Watergate scandal,<br />

but in 1969 he conducted a seminal televised interrogation<br />

of a young and intellectually sharp Swedish politician, in<br />

search of answers about the country’s model society. The man<br />

in the chair opposite Frost was Olof Palme, Sweden’s Social<br />

Democratic Education Minister and Prime Minister in waiting.<br />

As head of government he would help to cement Sweden’s<br />

political reputation internationally through his defence of<br />

the Swedish model from the pressures of American economic<br />

imperialism and Soviet expansionism alike. A consummate<br />

statesman, Palme has since become faded, a symbol of the<br />

golden years of Sweden’s social democratic settlement. In the<br />

minimal surroundings of a Stockholm tv studio and seated<br />

on two leather armchairs designed <strong>by</strong> Le Corbusier, Frost<br />

probed Palme about the Swedish way. In the days beforehand<br />

the domestic press had promised an epic battle between<br />

the two heavyweights, but the visiting interviewer was met<br />

<strong>by</strong> a disarmingly cool and assured opponent. Frost’s challenging<br />

and provocative style demanded that Palme represent<br />

not just himself but the entire Swedish nation, from foreign<br />

policy to social reform. Defending opposition to the Vietnam<br />

War and being coy about his leader ship ambitions, Palme<br />

calmly attacked the Anglo-Saxon political model and threw<br />

Frost’s questions back at him.<br />

‘If you could look at one place and say “David, that’s the<br />

real Sweden,” where would you tell me to look?’ began Frost<br />

in his trademark laid-back style.<br />

‘I can’t,’ came the politician’s reply. ‘To a foreigner this is<br />

might seem a small and dull country, but to me it is a country<br />

18

everybody’s utopia<br />

with infinite variety… there is not any one particular place<br />

that is Sweden.’ Unhappy with the answer, Frost probed again,<br />

‘What is the essence of being Swedish?’<br />

‘We are often pictured as a country that has solved its<br />

problems,’ replied Palme after some consideration. ‘There<br />

are a great amount of unsolved problems in this country, and<br />

to solve these problems we need a sense of community.’<br />

Palme’s answer revealed one of the core characteristics of the<br />

Swedish model – the nation state as political project. The<br />

community that Palme hinted at was the People’s Home, or<br />

folkhem, an understanding of the interdependence of people<br />

within the country where the nation was seen as a single<br />

family. A political undertaking synonymous with a nationality,<br />

it had been introduced <strong>by</strong> former Prime Minister Per Albin<br />

Hansson, a man Marquis Childs had encountered on his visit<br />

to 1930s Stockholm. As Gunnar Asplund and his architectural<br />

contemporaries tried to build homes for people, the Swedish<br />

Social Democratic Party tried to build a single home for<br />

everyone in which all could flourish.<br />

Despite his claims to represent the working man, Palme<br />

was as typical of the average Swede as Asplund’s pavilion<br />

marked ‘paradise’ was of the everyday lives of most people.<br />

Born into an aristocratic family and able to travel widely, he<br />

was an intellectual rather than a union man with a moral<br />

gravitas that won him plaudits around the world. Raised in<br />

the wealthy Östermalm district of Stockholm and educated at<br />

elite schools in Sweden and the us, his polished English tones<br />

mirrored his similarly refined Swedish. With his abandonment<br />

of privilege and his modest family house in Stockholm’s<br />

western suburbs, he embodied a vision of a new classless<br />

society. It was a vision he took with him around the world.<br />

Where Wollstonecraft, Childs and Frost led many have<br />

followed. The idea of a golden middle way to be copied has<br />

19

a utopia like any other<br />

become rhetorical currency amongst the European left and<br />

even some Liberals and Conservatives. The British sociologist<br />

Anthony Giddens used the concept extensively to describe a<br />

new kind of social democratic society, and it was in turn used<br />

<strong>by</strong> Tony Blair and Bill Clinton in their own political projects<br />

of the 1990s to promote an inclusive and cohesive vision of<br />

a society where all could succeed and thrive.<br />

Neither is this admiration without foundation; from the<br />

1960s to the 1980s Sweden had the lowest levels of inequality<br />

in the developed world <strong>by</strong> a considerable degree. When<br />

the celebrity French economist Thomas Piketty released his<br />

bestselling critique of global inequality, Capital in the 21st<br />

Century, he used the country as a case study, showing how<br />

Sweden had succeeded where others seemed to have failed. 1<br />

Piketty compared it to France, Britain and the us as an<br />

example of how different countries had evolved and managed<br />

their economies, with Sweden going further than any other<br />

developed country in reducing the huge disparities between<br />

wealth and poverty that existed in Europe at the beginning<br />

of the 20th century during the Belle Époque.<br />

Together with its longstanding reputation for economic<br />

egalitarianism, in time the Swedish model developed to<br />

encompass gender equality and environmental responsibility<br />

on the global stage. Sweden itself meanwhile has wholeheartedly<br />

embraced the view that it is something special.<br />

This fusion, or confusion, of culture and politics is produced<br />

and reproduced worldwide across the media, from internet<br />

listicles on modern Swedish fathers to bestselling recipe<br />

books and conventions for fans of Swedish culture. In many<br />

cases the country is reduced to a lifestyle choice with vague<br />

connotations towards what the people buying it want to<br />

believe in and what Sweden itself wants people to believe.<br />

1 See graph on page 62.<br />

20

everybody’s utopia<br />

The statistics though speak for themselves. Sweden is<br />

ranked fourth in the world for gender equality <strong>by</strong> the World<br />

Economic Forum and has been declared the world’s most<br />

sustainable country <strong>by</strong> one green investment monitor, also<br />

holding a high place in the Yale University global environmental<br />

performance rankings. It also regularly features in the<br />

top-ten on the Human Development Index, a un-backed ranking<br />

of countries which collates wealth, education, opportunity<br />

and life expectancy. This creates a complex picture in which<br />

Sweden is often presented as a vision of future society devoid<br />

of the problems which beset the rest of the world, or <strong>by</strong> its<br />

detractors as something far more sinister. Yet somewhere behind<br />

these international rankings, national branding campaigns<br />

and the utopian dreaming exists a real country occupied <strong>by</strong><br />

real people; safe and clean and green and modern. Where, in<br />

the words of David Frost, is the real Sweden, and where is<br />

the line between utopian fiction and reality? What is the<br />

Swedish model, who are the people who live in it, and moreover,<br />

what is it good for?<br />

21

Luath Press Limited<br />

committed to publishing well written books worth reading<br />

luath press takes its name from Robert Burns, whose little collie Luath (Gael.,<br />

swift or nimble) tripped up Jean Armour at a wedding and gave him the chance to<br />

speak to the woman who was to be his wife and the abiding love of his life.<br />

Burns called one of ‘The Twa Dogs’ Luath after Cuchullin’s<br />

hunting dog in Ossian’s Fingal. Luath Press was established<br />

in 1981 in the heart of Burns country, and now resides<br />

a few steps up the road from Burns’ first lodgings on<br />

Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.<br />

Luath offers you distinctive writing with a hint of<br />

unexpected pleasures.<br />

Most bookshops in the uk, the us, Canada, Australia,<br />

New Zealand and parts of Europe either carry our books<br />

in stock or can order them for you. To order direct from<br />

us, please send a £sterling cheque, postal order, international<br />

money order or your credit card details (number, address of<br />

cardholder and expiry date) to us at the address below. Please add<br />

post and packing as follows: uk – £1.00 per delivery address; overseas<br />

surface mail – £2.50 per delivery address; overseas airmail –<br />

£3.50 for the first book to each delivery address, plus £1.00 for each<br />

additional book <strong>by</strong> airmail to the same address. If your order is a gift, we will happily<br />

enclose your card or message at no extra charge.<br />

Luath Press Limited<br />

543/2 Castlehill<br />

The Royal Mile<br />

Edinburgh EH1 2ND<br />

Scotland<br />

Telephone: 0131 225 4326 (24 hours)<br />

email: sales@luath.co.uk<br />

Website: www.luath.co.uk<br />

ILLUSTRATION: IAN KELLAS