A KORA OF KORAS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Rewalsar

Type to enter text

Going Round in Circles

In the foothills of the Himalayas lies a sacred lake called Tso Pema; a jewel

sitting in a mountain bowl of hills. Above the lake is a large,150ft high, goldengilded,

brightly painted statue of Padmasambhava, his eyes wide open expressing

fierceness, compassion and delight. 1 Beneath his paradoxical gaze walk Tibetans

of all ages, moving clockwise round the waters night and day.

I arrived at four in the morning after an overnight bus from Delhi. It was early

spring, still cold, dark and quiet. From the Tibetan monasteries and small lanes

that surround the lake, monks and lay people streamed out onto the path that

circles the water, many of them holding a spinning prayer wheel 2 in their right

hand or fingering a mala of beads. Most looked straight ahead, absorbed in

practice, atoning for past deeds, accumulating merit for the future, reciting a

mantra, 3 a prayered description of Reality revealed over a thousand years ago,

attuning themselves to its meaning of the always, already Reality of Liberation,

sounding its purifying vibration through their bodies and out into the world; they

were engaged in a Kora, a circumnambulation of a sacred place, they were going

round in circles.

Video on Koras

T

Type to enter text

he concept of the prayer wheel is a physical manifestation of “Turning the

wheel of the Dharma,” which describes the Teachings of the Buddha.

“Those who set up a place for worship should use their knowledge to propagate the Dharma to

common people, should there be any man or woman who is illiterate and unable to read the sutra,

they should then set up the prayer wheel to facilitate those illiterate to chant the sutra, and the

effect is the same as reading the sutra” . . . Tibetan texts also say that the practice of turning the

Wheel was taught by the Indian Buddhist masters, Tilopa and Naropa, as well as the Tibetan

masters Marpa and Milarepa.

- Wikipedia

Om Mani Padme Hum 4

(Om the Jewel in the Lotus)

The Padmasambhava Mantra 4

Om Ah Hum Vajra Guru Padma Siddhi Hung

Padmasambhava

Type to enter text

Padmasambhava is known as ‘Guru Rimpoche’ or ‘Precious Teacher’ and is

called the ‘second Buddha.’ The birth of Padmasambhava was prophesied by the

Buddha:

“When the Buddha was about to pass away at Kushinagara, and his disciples were

weeping. He spoke to them about his next manifestation in what is today called

the Nirvana Sutra: “The world being transitory and death inevitable for all living

things, the time for my departure has come. But weep not; for eight years after my

parinirvana (release from karmic rebirth), my manifestation will be born in a lotus.

Due to this manifestation’s deep connections with all sentient beings in the

Dharma-ending age, countless beings will benefit from his immense Dharma

promulgating activities. He will be called Padmasambhava and by him the

Esoteric Doctrine will be established.”

Padmasambhava visited Rewalsar before bringing Indian, Tantric (esoteric)

Buddhism to the high plateau of Tibet in the 8th century5 and the story of what

happened there is symbolic of the work of his life and the underlying principles of

Tantric Tibetan Buddhism; ‘This isn't the crop-haired monastic Tibetan

Buddhism of sacred vows we're familiar with, instead it's one practiced by yogis

and dreadlocked shamanistic wanderers, people in their houses, and those situated

outside of the monasteries.’ Let me tell you that story:

Mandaravya

Type to enter text

Once upon a time in Rewalsar, Padmasambhava met Mandaravya, a woman

who was destined to be his consort6 in this life. Mandaravya was an intelligent,

beautiful young woman who had previously refused all her suitors and eventually

took a vow of celibacy intending to devote her life to spiritual practice. Her father,

King Shastradhara, was not happy about her refusal to marry, for kings upheld

the customs of the world and it was through marriage that strong and necessary

bonds were established amongst the hill tribes.

Many local kings and princes sought Mandaravya’s hand in marriage but she was

determined to devote her life to spiritual practice. Finally, her father made it

known to all suitors that his daughter would not marry but instead become a

celibate nun and he built her a refuge where only women were allowed, a place

where she could live apart from the world. But seeds of ancient karmas no longer

remembered were about to bring great changes to her life.

For several years, Mandaravya persisted in spiritual practice until one day an

extremely handsome, wandering, wild-eyed, long-haired, Pakistani yogi7 from the

mountainous region of the Swat Valley, passed below her windows; it was

Padmasambhava who from a distance beyond the sight of human eyes could see

the future8 and had been spontaneously drawn to Mandaravya as his consort in

this life.

Yabyum

Type ‘Fated’ to encounters enter text occur for all of us, but rarely between those destined for such

epoch-making work, 9 for both Padmasambhava and Mandaravya were to play a

central role in bringing ‘Tantric Tibetan Buddhism’ 10 to the ‘Himalayan regions

of India and Tibet.

So deep was the karmic attraction of Mandaravya for Padmasambhava that

merely glimpsing him as he passed below her window awakened previously

unknown memories and a revolution in her heart’s desiring; overwhelmingly

distracted, she abandoned her celibate renunciation and sent one of her women

attendants to invite this extraordinary man into her castle-refuge where before

only women had been allowed.

They were drawn to each other, not merely with emotional-sexual attraction,

(although these interests were not excluded) and re-engaged their many-lifetimeslong

11 relationship that expressed the essence of Tantra; a philosophy and

realization of Reality in which everything is woven 12 together; nirvana and

samsara, liberation and bondage, male and female energies complementing each

other; emotionally, sexually and physically, nothing denied or excluded. Indeed,

Tantric Tibetan Buddhist imagery is often represented as a man and woman in

ecstatic sexual embrace; the feminine offering her life-nourishing energies to feed

the masculine and the male husbanding, protecting and supporting the female;

they do not seek to avoid or escape each other as in many of the ascetic spiritual

traditions of India; rather they complete each other like all apparent opposites do.

Type to enter text

In the highest teaching of Tantra, 13 ‘There is neither one God or many gods,

there is only God or in Buddhist terminology - Reality;’ there is nothing greater

than or other than this undivided Reality and thus nothing to turn away from.

Tantra embodies this paradoxical understanding of life and religion in which the

goal of liberation is not different than what is always and already the case.

When Mandaravya’s father was told a man’s voice was heard within her rooms

and that his daughter had invited a wandering yogi into her chambers, he was

enraged by the transgression of her public vows of renunciation and the violation

of his daughter by what he thought was a common, low-born man. Because of

this he would lose face amongst the kings and princes he had discouraged from

seeking his daughter’s hand in marriage and he himself would become a

laughingstock.

So the king sent his soldiers to seize them; Mandaravya was placed in a deep pit to

punish her and Padmasambhava was bound to a stake fixed in a pyre of wood

soaked in mustard oil which was then set alight. After the flames leapt up, king

Shastradhara, left for his residence and the fire continued to burn for a whole

week, filling the air with clouds of black smoke

Type to enter text

When the king returned to see his daughter and what remained of the yogi, he

found a young man of eighteen embracing Mandaravya in his arms, sitting on a

lotus blossom floating in the middle of what was now a small lake.

Padmasambhava and Mandaravya

Astonished by this miraculous sight, the King

fell to his knees, realizing his utter failure to

appreciate the profound attainment and

siddhis 14 of this wild yogi or honor the

attraction of his daughter to this great being.

The king, ashamed of his actions, vowed to

adopt the Tantric teachings of the Buddha and

gave his daughter, Mandaravya, as consort to

Padmasambhava. This is the story of how Tso

Pema, or ‘Lotus Lake’ came to exist, the same

lake around which I and many Tibetans were

walking that cold, early March morning.

epoch-making work, for both Padmasambhava

and Mandaravya were to play a central role in

bringing ‘Tantric Tibetan Buddhism’ to the

Himalayan regions of India and Tibet.

Type to enter text

Whether these events actually occurred or this is but one amongst the many

‘myths’ that have come down to us from the ancient world it is impossible to know.

Over a thousand years have passed since this is said to have happened. In his

study and experience of psychology and world mythology, Carl Jung found myth

to be a unique language and way of describing reality in ancient civilizations. He

wrote:

“The mythic image is not to be taken literally and concretely 15 as it would be in

the belief-system of a particular religion, nor is it to be dismissed as ‘mere

illusion,’ as often happens in scientific circles. Instead, we must approach myth

symbolically as revealed eternal 'truths' about . . . existence. ‘Once upon a time’

does not mean once in history but refers to events that occur in eternal time,

always and everywhere.”

- Myth and Psyche, CG Jung Institute

One could say that the story of how Tso Pema lake came to exist and the

miraculous events surrounding it, express the principles and philosophy of

Tibetan Buddhist Tantra, presage Padmasambhava’s life and work in Tibet as a

Tantric Buddhist master, and offer a mythic description of Tantric Tibetan

Buddhism.

Ulm Cathedral (tallest cathedral in Europe)

Type to enter text

The Center of the World

Whole cultures orbit round one or another mythical idea or story. The ancient

legends tell of great heroes, gods, teachers, avatars, holy objects, events and

places . . . but what myth lies at the center of our world today? Actually, there is a

way we can tell . . .

As if we were instructed to do so, human beings have always built the tallest

building in their towns or cities as a symbol of the dominant theme or myth of

their culture. In ancient times, the tallest building was always a temple, church,

mosque or cathedral; glorifying a supreme, intelligent and dominant principle or

what we today call - ‘God.’

Over time in the west, as religion became less and less important, political

buildings became the tallest structures in town,16 embodying ideals of social

organization and the rights of man and woman; but now in 21st century cities all

around our planet, the buildings that rise above all the others are technological

wonders, owned and named after corporations and dedicated to one or another

business or financial enterprise.17 These ‘tallest buildings’ embody the idea or

‘myth’ of fulfillment through technology and business that touches every aspect of

our lives; we spin round the ideas they embody like planets round the sun.

The Scarab Beetle rolls the ball of the sun across the sky

Type to enter text

The Sun is God

Once upon a time the sun was worshipped as ‘God,’ the tremendous,

absolutely essential power and it was this brilliant, radiant, golden star; not money,

business or politics that was thought and felt to be the supreme power on which all

life depends. The sun was the obvious ‘Truth’ or ‘God’ to the greatest civilizations

of the ancient world and still is in many of what we call ‘primitive cultures’ to this

day.

Type to enter text

Sunrise New Mexico desert

Type to enter text

In 1933, the psychologist Carl Jung came to America and visited the Pueblo

Indians of New Mexico. One early morning as the sky began to lighten above the

vast silence of the New Mexican desert, Jung and an old Pueblo Indian man,

Ochwiay Biano, climbed up onto the roof of an adobe kiva. Jung wrote about

what happened in his biography, ‘Memories, Dreams and Reflections’:

"As I sat with Ochwiay Biano on the roof, the blazing sun rising higher and

higher, he said, pointing to the sun, “Is not he who moves there our father? How

can anyone say differently?

How can there be another god? Nothing can be without the sun.”

His excitement, which was already perceptible, mounted still higher; he struggled

for words, and exclaimed at last, “What would a man do alone in the mountains?

He cannot even build his fire without him.” I asked him whether he did not think

the sun might be a fiery ball shaped by an invisible god. My question did not even

arouse astonishment, let alone anger.”

“Obviously it touched nothing within him; he did not even think my question

stupid. It merely left him cold, I had the feeling that I had come upon an

insurmountable wall. Although no one can help feeling the tremendous impress

of the sun, it was a novel and deeply affecting experience for me to see these

mature, dignified men in the grip of an overmastering emotion when they spoke

of it.” - Carl Jung

The mother of the World

Type to enter text

Very few people in our modern, ‘westernized’ culture feel an ‘overmastering

emotion’ for the sun, even if we know how essential it is to our existence. Instead

we are rational, scientific and transactional18 about it, an attitude we bring to all

of life, as we take the great mystery and power of our natural world for granted.

Forgetting our small place in the web of life, we lack humility and consider

ourselves free from any debt or obligations regarding our own life or what we

must do here. If we consider it at all, we think of “God’ as a loving, male (in the

western countries), anthropomorphic judge who stands distant and apart, not as

that power and intelligence that surrounds and pervades us,; we worship a ‘God’

we imagine in heaven, not a ‘God’ incarnate as nature, a God we see, feel, fear,

love and are utterly dependent upon and are obviously and intimately related to;

for we have lost our ‘spiritual’ connection to nature.

Nature is the great Feminine and we no longer refer to Her as God. We have

forgotten that Laws of Nature define our lives; we believe we have ‘conquered’

Nature with science and technology and now attempt to control and exploit Her.

We have forgotten she is our mother on whom we are dependent and although

protective, she is also horribly destructive with rules and limits about how far we

can go.

Type Is it surprising to enter text our world is disturbed by ever-increasing, human-caused disruption

of our ecos?19 Nature reacts to our aggressive violations and disturbances with

increased heating of the earth and oceans, melting of the polar ice caps, sea-level

rise, coastal flooding, more extreme weather, more frequent volcanoes and

earthquakes, not to mention diabetes, Alzheimer’s, obesity, cancer and heart

disease and these are the names of only a few of the more obvious symptoms of

Her reactions.

In ancient times, when the world was seen as the living body of God or the gods,

symptoms and events of disruption in the natural world were considered omens

of great significance and individuals would have dreams regarding them. Such

things would be taken seriously, for God (or the Gods) were disturbed, and

remorse, repentance, sacrifice and change of actions were needed; but today we

hardly even notice.

Connection and obligation to the elemental forces of the world used to be the

foundational principle of 'religion,’ a religion that did not need to be believed in,

only observed and participated in.

Type to enter text

Because of their more primitive level of technology,20 ancient civilizations were

not as insulated from nature as we are in the 21st century and had more obvious

dependencies on elemental forces. In the ancient world and amongst low-tech

cultures today (like the Hopi), it was and is an undeniable fact that human life is

dependent on the sun and people expressed their gratitude in ritual and sacrifice

or what we have come to call . . . ‘religion.’ Whole cultures felt their obligation

for the sun’s overwhelming generosity, and gifting and rituals of sacrifice were

engaged to give back as much or even more than had been received. Sacrifice was

and is the principle at the heart of each and every religion; sacrifice stood at the

center of the ancient world and great temples were constructed that honored and

provided a place for such sacrifice to occur.

Today, rather than sacrifice, the principle of ‘accumulation’ and ‘control’

characterize our world view. Even what we refer to as ‘religious prayers’ are

performed primarily for getting something; but in ancient times sacrifice was

practiced to give something back to the giver. The articles of sacrifice used to be

animals, blood or money, but in the great religions of the Vedic culture,

Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the ancient principle of sacrifice was

re-defined by their great god-men. These beings clarified the meaning of what

sacrifice meant and in doing so gave rise to what has become the great religions of

today.

Jesus Was a Sacrifice, Not a Survivor

“Jesus of Nazareth has become a universal archetypal figure in the minds of all

mankind. But he has thereby become more a part of conventional mind and

meaning than a servant of the Real. Unfortunately, he has become identified with

personal or egoic survival rather than perfect sacrifice of self, mind, life, emotion,

and body.

“Paul the Apostle said that if Jesus did not survive his death, then belief in him

and his Teaching is fruitless. Therefore, the bodily and personal survival of Jesus

became the traditional foundation of Christian belief and practice. But Paul's

conception is false. The Truth and the Law of sacrifice are not verified by or

dependent upon the knowable survival or immortality of any man, including

Jesus. The Truth of the Teaching of Jesus, itself an extension of the Teaching of

the ancients, did not at all depend on his survival, or, more specifically, knowledge,

on the part of others, of his survival. If it did depend on his personal or

conventional soul-survival of death, or the knowledge of such on the part of

others, he could not have taught anything of ultimate significance during his

lifetime, and all Teaching before his time would have been inherently false. But

Jesus himself specifically denied both possibilities.The Teaching of Jesus is

essentially the ancient Teaching of the Way of Sacrifice.

The cave where the body of Jesus was laid after his crucifixion

Type

“He, like

to enter

others,

text

taught that the sacrifice that is essential is not cultic or external to

the individual, but it is necessarily a moral and personal sacrifice made through

love. It is the sacrifice of all that is oneself, and all that one possesses, into forms

of loving and compassionate participation with others, and into the absolute

Mystery of the Reality and Divine Person wherein we all arise and change and

ultimately disappear. Therefore, the proof of his Teaching is not in the

independent or knowable survival of anything or anyone, but in the enlightened,

free, and moral happiness of those who live the sacrifice while alive and even at

death.

“We cannot cling to the survival of anyone, or even ourselves. This clinging has

for centuries agonized would-be believers, who tried to be certain of the survival

of Jesus and themselves. Truly, Jesus did not survive in the independent form that

persisted while he lived, nor does anyone possess certain knowledge of the history

of Jesus after his death. All reports are simply expressions of the mystical

presumptions and archetypal mental structures of those who make the reports.

And neither will we survive the process of universal dissolution everywhere

displayed. Jesus sacrificed himself. He gave himself up in loving service to others

and in ultimate love to Real God. All who do this become what they meditate

upon. They are Translated beyond this self or independent body-mind into a

hidden Destiny in the Mystery or Intensity that includes and precedes all beings,

things, and worlds.”

- Adi Da Samraj

Type to enter text

Jesus and the Widow’s Mite

I t is written in the New Testament:

“And He (Jesus) sat down over against the treasury (of the temple in Jerusalem), a

nd beheld how the multitude cast money into the treasury: and many that were

rich cast in much. And there came a poor widow, and she cast in two mites, which

make a farthing. And He called unto Him His disciples, and said unto them,

Verily I say unto you, This poor widow cast in more than all them which are

casting into the treasury; for they all did cast in of their superfluity; but she of her

want did cast in all that she had, even all her living.”

- Mark 12:41-44

Jesus clarified the true, real and necessary sacrifice; it was not the amount of

money or other symbols of wealth (animals, grains, blood), it was not the sacrifice

of our excess, but the sacrifice of ‘our want’, the sacrifice of ‘all our living.’ He

points to sacrifice not merely as an action, but an understanding, a condition, a

state of living and ultimately a Realization in which ‘all we have,’ our very ‘self,’ is

truly always and already sacrificed to, or sublimed in the living God.

Type to enter text

Yagya

The philosophy, practice and principle of the oldest religious culture in the

world is found in ancient India and may be summed up by the word ‘Yagya’ or

‘sacrifice.’ In the Vedic culture there are said to be five debts that we all must

repay—to the celestial gods, to the sages, to our ancestors, to other humans, and

to all living beings. Yagya, often interpreted as a Vedic sacrifice, is typically done

with the help of priests in which offerings are made to various deities to nourish

and repay our debts to them so they are satisfied and in turn assist us in achieving

our goals and desires in life. It is Yagya that is said to lead to Yoga, the auspicious

state of harmony and unity with God, gods and all beings and elements, both

here and hereafter.

In the Vedic world Yagya was the panacea of all human problems from martial

discord to snakebites. However the understanding of Yagya was interpreted

differently for people in various stages of life.20 For those who had left the city or

village and lived in the forest, devoting their whole life to Liberation, their

summary of a radical understanding of yagya is recorded in the Upanishads. For

them, the many Yagyas of animals, grains, money and fruit were not capable of

being performed and a more principled understanding of Yagya took their place;

abandoning the many different sacrifices ritually performed by householders,

Type to enter text

the Upanishads seized on the essence of sacrifice and spoke of the sacrifice of ‘self ’

or our false identification as an individual and it was said that this sacrifice alone is

what leads to release from all suffering and Liberation.

Lord Krishna in the final chapter of the Bhagavad-Gita, after laying out all the

different paths and practices of Yoga (karma yoga, gnana yoga and bhakti yoga)

and Dharma says: “Abandon all Dharmas (varieties of religious practice) and

surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear.”

There are many ways to interpret this instruction; from the more common

abandonment of lower desires to devote oneself to God (whoever and whatever

that is), to the transcendence of self and attention itself and the Realization there is

only God. In the varying understandings of this verse lie the origination of not only

the vast number of the religious traditions of India, but of the whole world.

Sacrifice is the fundamental principle of life but is engaged and understood

differently by diverse people in different stages of life and distinct states of

consciousness or Realization.

Ultimately, the yagya or what is sacrificed becomes more and more comprehensive

and all-inclusive as we move from gross to subtle in the sacrifice of our physical,

psychological and spiritual desires, to our very self and everything whatsoever and

altogether; this is the principle of the yagya of our life.

KORAS

There are still places on earth like Tso Pema Lake where people sense an

incomprehensible meaning and power far greater than their own and every one

of these places is a religious site where the living relationship to ‘God’ is honored.

There the mystery of life stands evident and people walk in circles around it, these

‘circlings’ are called a ‘Kora,’ and ‘Kora’ is the central theme of this book.

Over a million people circumnambulate Arunachala on Guru Purnima,

the full moon celebration of the Guru in July

Video of the Kora/ Pradkashina of Arunachala

Koras Around the World

I lived for several years in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, where every day, hundreds

of people walk round the holy mountain, Arunachala, as they have done for

thousands of years. On certain full moon nights close to a million people of all ages,

arrive in buses packed full of devotees. They circumnambulate this holy mountain in

a wave of humanity, packed shoulder to shoulder, nearly all of them barefoot in

respect, filling the road around the mountain in a moving sea of humanity.

Orange robed sadhus line the sides of the road and lepers brought in specially for the

occasion, beg from the pilgrims, holding out their hand or a cup for rupees in an

ancient opportunity given to giver and receiver to exchange the energy of life with

each other.

On these special nights, much of the 14km-long road round the mountain is lined

with small makeshift stalls filled with various products, or merchandise which is spread

out on the ground on plastic tarps next to just-for-the-day tents and small stands

offering sweets, coconut water, rice, dal, puris, samosas, parathas, religious paintings

of the deities, statues of the gods, books and pamphlets, chairs, hammocks, mats,

baskets and blankets.

Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi

The ashram of Ramana Maharshi, one of the greatest sages of the 20th

century, lies just outside the town of Tiruvannamalai on the site of an old

graveyard at the foot of the holy mountain. Ramana spent nearly his entire life on

or around Arunachala. Devotees walk around his maha-samadhi22 site inside a

temple-hall built over the spot where his body was buried.23

Beautiful, compassionate and extraordinarily simple in the way he lived and

brilliant, insightful, profound and sometimes humorous in his teaching, Ramana

was not a teacher of acquired wisdom, he was a Maharishi, a great Realizer, an

embodiment of what he taught who only after realization found confirmation of

what he had realized in books.

The Maharshi realized or had become one with Reality or what is called the state

of non-duality or Advaita,24 and was and is considered a divine incarnation.

Towards the end of his life before he passed away from cancer, a devotee,

overwhelmed by the thought of his Master’s dying began to cry. Ramana looked

at the man with great compassion and remarked, “Where could I go? I am always

here.” Such is the paradoxical confession of Advaita, absolute non-difference

from the world.

Mount Kailash as seen from lake Manasrovar

Mount Kailash- the Center of the World

There is the great Kora of Mount Kailash on the Tibetan Plateau, one of the

highest and most desolate places in the world. It is a mountain that represents the

center of the universe for the Hindu, Buddhist and Bon traditions.

Pilgrims circumnambulate Kailash on a path that takes days to complete,

beginning at 15,000ft and walking over passes that rise to 18,720 ft.

Some take weeks to perform the kora, prostrating themselves fully on the ground

with every step, using leather knee pads and hand protectors for an arduous act

said to erase lifetimes of sins.

From the slopes of Kailash flow the major rivers of India, including the Indus

(from which ‘India’ got its name), the Sutlej, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra

(the only ‘male’ river that flows from the high Himalaya). Two of these rivers (the

Indus and Brahmaputra) embrace the western and eastern borders of India

respectively and their headwaters are found close to each other on this holy

mountain.

The Indus and the Brahmaputra flow in opposite directions, one going east (the

Indus) and one to the west (the Brahmaputra), each eventually piercing the

Himalayas in massive canyons which rise up over 17,000ft in immensities (the

Indus gorge is the deepest in the world) that dwarf the Grand Canyon in size.

Video of Circumambulation (Kora) of the Kaaba

The Circumnambulation of the Kaaba in Mecca

There is a circumnambulation of the sacred black stone of Islam, the Kaaba in

Mecca, which is engaged by millions of pilgrims, a circling that is different from

most others as it proceeds in a counter-clockwise direction.

There are many Koras and these are but a few and in each of them people circle

and return to the place they started, never leaving the great, circular and everwheeling

path of life.

Approach to the Rohtang Pass from the Kullu Valley in Himachal Pradesh

How Buddhism Came to Tibet

During the years I lived above Old Manali in the foothills of the Himalayas,

we took a Jeep over the Rohtang Pass25 which rises at the head of the Kullu valley

of India and climbs up onto the high Tibetan Plateau and Ladakh.

We traveled across the high desert of the Ladakhi plateau to Leh, the ancient

Tibetan trading city of the Silk Road that once stretched from China to Europe,

driving over several 17,500 ft passes, some of the highest in the world.

We visited ancient Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, for Ladakh is all that remains

of Tibet that has not been occupied by the Chinese.

The very first Tibetan Buddhist monastery built in Ladakh is called Samye and it

still stands today near the banks of the Brahmaputra river. It owes its construction

to the same Padmasambhava who appeared in Rewalsar and whose story in

Rewalsar we have already heard.

How Samye monastery came to be built holds a fascinating part of the story of

Padmasambhava and offers insight into understanding Tibetan Tantric

Buddhism.

Trisong Duetsen

In the eighth century, Trisong Duetsen, the Tibetan king wanted to establish the

Buddha Dharma in Tibet and began to build a Buddhist temple and monastery.

After months of clearing and leveling the area, hundreds of workmen labored to

set the large foundation stones for the outer walls.

After this work had been finished, everyone left the building site to perform a

blessing ceremony and rest before beginning to raise the walls. When they

returned the next day, the huge stones they had set deep in the earth had been

dug up and were scattered around the site. Disturbed but determined, they again

reset the large stones, but the next morning their work had again been destroyed.

The king and his workmen realized that powerful spirit-entities were destroying

the work on the monastery because these deities were opposed to the introduction

of the new religion of Buddhism to their country.

Trisong Duetsen met with his advisors and they decided to ask the great Buddhist

scholar, Santarakshita of Nalanda University26 to come to Tibet; they all thought

that with Santarakshita’s vast knowledge of the scriptures he would be able to

help them. An offering of gold was assembled and a group of men set out on the

arduous months-long journey down from the high Tibetan plateau to the plains

of India where they hoped to find Santarakshita.

Tibetan Demons

They crossed huge stretches of barren country, high, snow-covered passes and

many dangerous and fast flowing rivers until they eventually came to the green,

forested slopes of the southern Himalayas and descended down onto the hot

lowland plains and Bihar.

Nalanda University was the most famous Buddhist school of intellectual-religious

learning in ancient India, and Santarakshita was the head teacher there.

After receiving the offering of gold from Trisong Duetsen on behalf of the school

and hearing the request of the Tibetan king that he come to Tibet and help

establish a Buddhist monastery, Santarakshita agreed to leave India for the long

and arduous journey up to the Tibetan plateau.

Months later after arriving in Tibet he was brought to the building site at Samye.

When Santarakshita saw for himself the huge scale of what had occurred on the

building site, he realized that to overcome these powerful, local spirit-deities who

were opposing the building of the monastery, his sutra-based scriptural knowledge

and practice of non-violence was insufficient. He felt the Tibetans needed

someone possessed of super-natural powers (siddhis) and capable of using

extremely forceful actions and even weapons against powerful , harmful and

violent beings.27

Chenrezi, a cosmic form of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

Santarakshita advised King Trisong Duetsen to send for the great Tantric

Buddhist master, Padmasambhava, as only he could subdue the Tibetan demons

and demi-gods and this is the how and why Padmasambhava eventually came to

Tibet where in a years-long series of dramatic and often violent struggles he

successfully overcame the local demi-gods and bound them by vows to protect the

Buddha Dharma.

Padmasambhava did not preach non-violence to the local deities of Tibet; he met

them head-on and engaged them in battle, with ‘fierce compassion.’ This

paradoxical attitude is the expression you often see on the face of

Padmasambhava and hear about in the tales of his various encounters, which are

recited to this day all over Tibet and have become part of the teachings of

Tibetan Tantric Buddhism.

In the many Tibetan stories of men, gods and animals we begin to understand

the teachings of Tantric Tibetan Buddhism; for here all of life is embraced and

dealt with, nothing is dismissed, renounced or turned away from, unlike the

Hinayana Buddhist tradition of south-east Asia, which tends to turn away from

the world and strife; neither is there the embrace of another state of existence or

some higher realm which occurs in the Mahayana traditions; rather, in Tibetan

Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana, there is non-preference for any category of

existence whatsoever.

“By passion the world is bound, by passion too it is released”

An example of this ‘non-preference of the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition is called-

“The Skillful Means of Reversals”

‘The Skillful Means of Reversals’

“Those things by which evil men are bound, others turn into means and gain thereby release from

the bonds of existence. By passion the world is bound, by passion too it is released, but by

heretical Buddhists this practice of reversals is not known.”

- Hevajra Tantra

Monk in cave

Yama and Yamantaka

There is a dramatic and very well known story in the Tibetan Buddhist

tradition that dramatizes the embrace of typically shunned forms of acting and

the ‘practice of reversals’:

A monk was told by his teacher that if he meditated and engaged in mantra and

prayer continuously for 50 years, he would achieve enlightenment. So the monk

found a remote cave, arranged for a local person to bring him food and meager

supplies every few months and then proceeded to unceasingly meditate, pray and

chant mantras in that cave.

After 49 years, 11 months and 29 days, on the very eve of his goal of 50 years of

practice and his promised enlightenment, two thieves entered the front of his cave

with a stolen bull. The thieves did not notice the holy man sitting in the back of

the cave and they talked between themselves about the best way to escape the

people pursuing them and they decided to kill the bull. The monk heard what

they were about to do and in his highly sensitive state was filled with compassion

for the bull and cried out from the darkness of the cave for them to stop. The

thieves were surprised and scared but quickly recovered when they saw the

weapon-less hermit.

Yamantaka

Relieved of their fear, they decided to behead the bull in front of the monk and

since they wanted no witnesses, told him they would then behead him as well. The

monk begged to be allowed to live through the night, pleading to be spared for

but a few more hours so he could attain his long sought-for enlightenment after 50

years of practice.

But ignoring his pleas, they cut off the head of the bull with a knife and then

dragged the monk from his wooden meditation box and cut off his head as well.

In his nearly-enlightened fury, the now beheaded monk did not die but flew into a

deadly rage. He took the bull's head, placed it on his shoulders and then killed the

two thieves, drinking their blood from cups made of their skulls. Infuriated by the

ignorant, stupid and pitiless state of human beings, the monk had transformed

into Yama, the god of Death, and he decided to kill absolutely everyone.

This bull-headed demon of death then left the cave and began to roam about the

Tibetan countryside killing everyone he met. The people feared for their lives and

prayed to the Buddha-bodhisattva Manjushri, who took up their cause. Manjushri

is the Buddha of wisdom and to deal with Yama or death, Manjushri transformed

himself into Yamantaka, the ‘killer of death;’ a being similar in appearance to

Yama but ten times more deadly and powerful and went to war with death

himself.

Manjushri, the Buddha of wisdom - Yamantaka is his wrathful manifestation

As they fought, every direction in which Yama turned, he found infinite versions

of himself - Manjushri in his form of Yamantaka. Eventually, Yamantaka

defeated Yama and turned him into a protector of Buddhism. We often see

pictures of Yamantaka and Yama in the iconography of Tibetan Buddhism and

their story offers a dramatic example of the practice of reversals.

Manjushri

Kukurippa with his dog

Kukkuripa, the Mahasiddha with his Dog

K ukkuripa was a Mahasiddha28 who lived in India. He became interested

in Tantric Buddhist practice and chose the path of renunciation. He lived alone

deep within the forest, eating fruits, nuts, and wild yams, drinking water from a

nearby stream.

One day he found a small black dog, a female puppy, starving and lice-ridden,

hiding in the bushes. For months, he lovingly fed and nursed the dog and took

care of her. The two stayed together and Kukkuripa eventually found a cave

where he could meditate in peace. When he went out for food, the dog would stay

and guard the cave.

After 12 years had passed in this way, the gods of the Thirty-three sensual

heavens took note of Kukkuripa's accomplishments and invited him to their

heavens. He accepted and while there he was given many pleasurable things, such

as great feasts, exquisite music and all in beautiful surroundings.

Kukurippa with his dog

Kukkuripa lingered in heaven for what seemed many years, yet one day, he

thought of the small dog he had left starving alone in his cave. He called out to

the Gods, “Let us all descend now to the land of Jambudvipa (India).”And when

they asked ‘Why? He told them of the dog which must even now be dying without

water and food.

They replied, “Ah, even though you have practiced for so long, you are still

attached to a dog.”

But the thought of the dog’s suffering of thirst and starvation, its pains and terror

regarding dying, the rotting of its body and its bones turning to dust, would not

be dispelled from his mind.

Eventually, he looked down from the heavens and saw that his dog had become

thin, sad, and terribly hungry and he decided that he would return to the cave.

Vajrayogini

When Kukkuripa returned to his forest cave, the dog he had left behind ran up to

him. Both master and dog were extremely happy, and Kukkuripa picked up the

black she-dog, held it in his lap and caressed it. As he did so, the dog became the

Vajrayogini, radiant in the full bloom of youth, splendid with all the major and

minor auspicious marks.

This Wisdom Dakini told him that he (Kukkuripa) had learned there are greater

things than renunciation or the pleasure of the God realm. She said:

“The pure and free expanse of Liberation is not reached

by the contrived path of rejecting the world.

The changeless radiance of Great Compassion

Is not reached by the fabricated path of clinging to good qualities,

You are free from concepts. You sleep in an outhouse, consort with bitches,

are without possessions; play no instruments, and parrot no prayers or scriptures.”

With this instruction the Vajrayogini helped grant Kukkuripa realization and he

returned to the city of Kapilavastu, where he lived a long life

for the benefit of others.

Wheel of Life

The Wheel of Life

A representation of the nature of life is pictured in the Wheel of Life and the

origin of this image can be traced back to the Buddha:

King Bimbishara was the ruler of north India at the time of the Buddha and he

had been given an extremely beautiful and tremendously expensive gift by a

neighboring king. It was the custom to offer in return to the giver another gift,

something of equal or greater value, but King Bimbasara was unable to find

anything that could match the beauty, distinction, expense and refinement of this

particular gift. Since King Bimbasara was a follower of the Buddha, he decided to

ask him how to reciprocate such a seemingly priceless gift.

Buddha is said to have sat down and drawn out ‘The Wheel of Life’ and given it

to Bimbishara, saying that the understanding of this image was worth more than

any other gift that could be created and would be a most suitable gift for the King

to give in return.

The Wheel of Life is a summary of our existence. It ‘paints a picture’ of Reality

and according to the Buddha the perception and understanding of Reality was

the very best of gifts and this is why this picture is painted at the door of every

Tibetan Buddhist monastery.

Buddha thought it essential for human beings to get a true picture of the world

they live in (remember his hesitation about teaching) and herein lies a

fundamental difference between Buddhism and other religions in the world: the

original teachings and practice of the Buddha are realistic, based on what can be

observed, whereas every other religion in the world, in one way or another is

idealistic and based on something one needs to believe in, imagine or attain.

Every one of the great religions (Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam) asks you

to believe in or imagine something; Jesus, Krishna, Mohammed, the Divine

source of the Torah, the Bible, the Koran or Vedas, some God, heaven or hell.

Buddha not only did not ask for belief, he specifically advised against it; instead of

belief, Buddha asked a person to examine their own life and the nature of life

itself. In his last words spoken to the monks around him when he was dying he

said:

“Behold, O’ monks, this is my last advice to you. Salvation does not come from the sight of me. It

demands strenuous effort and practice. All component (put together and without self-essence)

things in the world are changlng. They are not lasting.

So work hard and seek your own salvation.”

The ‘salvation’ he refers to is release from the ‘terrible’ truth of change, old age,

illness and death. Buddha taught that such changes do not apply to the ‘self ’ or

‘Self,’ not because the ‘self ’ or ‘Self,’ can attain to some kind of heaven, but

because there is no individual self.

While it may be comforting to believe this and many people certainly do,

according to the Buddha, such belief is insufficient; this Truth must be Realized

and the very first step is the hearing or real seeing of the First Noble Truth: ‘Life

is Dukkha’ (suffering). Therefore and paradoxically, to realize that life is suffering

is one of the greatest of blessings.

The original teachings of the Buddha are not idealistic, they are not about how

things should or are supposed to be; his teachings are primarily about how things

are and he does not ask a person to believe in this . . . Buddha asks people to

observe the nature of life of which the Wheel of Life is a summary. Based on such

felt understanding there may come, in stages and ultimately all at once, an

awakening, what he called ‘Nirvana,’ a cessation and release from the wheel of life

and suffering; but this can only be Realized, not merely believed in.

This is why the ‘Wheel of Life’ was the ‘priceless gift’ that Buddha presented to

King Bimbisara and how it came to be placed at the entrance to every Tibetan

Buddhist monastery.

Without the first step of realizing everything is impermanent and infused with

suffering we would necessarily approach spiritual life idealistically and according

to the Buddha, improperly. Without such understanding, one would enter into

spiritual life seeking to drown ourself in some ultimate pleasure or restrict

ourselves by asceticism; whether we seek to protect our self with doubt or belief,

we will still be driven by desire or hope, unconsciously bound to the wheel of life

and thus merely duplicating the circling pattern shown in the Wheel of Life.

Ladakh has some of the oldest Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the world. At

the entrance of every monastery on the right-hand wall is painted an image

called the ‘Wheel of Life,’ a comprehensive summary of Buddha’s teaching in

picture form made for a predominantly illiterate people.

The Wheel of Life illustrates the co-dependently (one thing always depending on

another) arising, inevitable, always and only temporary, ever alternating,

‘good,’ ‘bad,’ pleasurable and painful karmas of birth and death, youth and old

age, disease and health, heaven and hell.

The Wheel illustrates the karmas (actions and destinies) of men, gods, demi-gods,

demons and animals, portraying the path of every sentient being who is bound

upon this wheel.

After Buddha was enlightened underneath the Bodhi tree, he thought he was not

going to teach as what he had to say was not capable of being understood nor of

interest to others.

Seeing his hesitation, the gods implored him to teach if only for the sake of the

few who might be prepared and to help others see the truth of Reality and it was

only at their urging that Buddha acquiesced and began his teaching mission to

‘Turn the Wheel of the Dharma.’

His very first teachings were, “The Four Noble Truths’ and the very first ‘Truth,’ -

‘Life is Dukkha (suffering).’ Suffering was inevitable and inherent in this world

and without awakening to this Truth,29 why would anyone ever be interested in

the teaching of freedom from suffering. If one was not clear that they were

absolutely going to die and lose everything and everyone, they would be primarily

motivated to seek pleasure and/or fulfill their various desires. Buddha did not

teach something called, ‘Buddhism,’ for the sake of any kind of fulfillment, rather

he said that people must first discover and understand the ‘Truth’ of life is

inevitable suffering; because only then, impressed with the suffering nature of

existence, would they be moved to practice the Way.

“This Dharma I have realized is profound, hard to see and difficult to understand, full of peace

and sublime, unattainable by mere reasoning, subtle and capable of being experienced only by the

wise . . . But this generation delights in worldliness (attachment), takes delight in worldliness,

rejoices in worldliness. It is hard for such people to see this truth, namely, inevitable conditionality

(everything includes its opposite) and co-dependent origination (nothing has a self-nature) and it

is hard to see the truth, namely; that the stilling of all desires, the relinquishing of all

attachments, the destruction of craving, dispassion and cessation is Nirvana. If I were to teach

the Dharma, others would not understand me, and that would be wearying and troublesome

- Buddha in the Pali Canon

Kisagotami brings her dead child to the Buddha

Kisagotami

There is a story in the Pali Canon about a woman by the name of Kisagotami,

who went through this process of awakening to the inherent suffering of life. She

had come to the Buddha in a state of desperation, carrying her dead child in her

arms.

Once long ago, in the time of Gautama Buddha, when he was speaking with monks and nuns under a

Bodhi tree, there was suddenly a disturbance in the back of the small group assembled. There appeared a

young woman, Kisagotami by name,

weeping and distressed and carrying a small baby in her arms.

Kisagotami was desperate. She was seeking for medicine that could restore her dead child to life. She believed

that the Buddha would know the cure for her lifeless child.

She strode directly into the assembly and approached

to where the Buddha sat.

She said, “Oh Lord Buddha, you are considered an Avatar, an incarnation of God, with miraculous

powers. Please, I pray you, help me.”

The Buddha asked her, "What is it you need help with?”

"My child, this one that I carry in my arms, has died,”

cried the young woman.

“Please, bring him back to life.”

A small gasp went through the assembly,

as the people heard what she had requested.

They had seen many miracles around the Buddha,

but his Teaching was one of Understanding and Realization,

not of miraculous cures or powers.

The Buddha sat quietly for a little while and then spoke:

“Bring me some mustard seed

from a house in which no one has died.”

Kisagotami thought that the Buddha would make use

of the mustard seed

and restore her child to life.

She was overjoyed at the simplicity of the task.

“I shall do as you ask,” she replied.

Then, taking her dead child with her, she

hurried off to the village to seek the mustard seed.

Now, in India,

mustard seed is one of the most common of things.

It is like salt or sugar in a home in the West today.

Kisagotami went up to the first house she saw and,

bowing at the door to the lady who stood there, asked,

“Do you have any mustard seed?”

The lady of the house noticed the urgency of the young woman’s request and went to fetch the

mustard seed immediately.

She brought it back and gave it to Kisagotami.

“Here my child. May it give you respite from all that ails you.”

Kisagotami hardly thanked her, so excited was she to receive the mustard seed. But, as she hurried

off back to the Buddha, she remembered the last part of his instructions to her: “. . . from a

house in which no one has died.” She needed to bring the seeds from a house in which there had

been no death. She had forgotten to ask!

Kisagotami turned around and went back to the woman, who still stood at her doorway.

“Please,” Kisagotami said,

“Has anyone ever died in your house?”

“Oh yes my child.

Only last year my Father died. But why do you ask?”

“Oh, I cannot take your mustard seed,” Kisagotami said. And she poured the mustard seeds back

into the woman's hands and hurried off to the next house.

There, Kisagotami again asked for mustard seed. Again, the mustard seed was brought to her by

the mistress of the house and again Kisagotami asked, “Has anyone ever died in your house?”

“Yes, my daughter died here two years ago.”

At the next house she heard,

“Yes, I lost my husband only this year.”

At the next house the woman said,

“Our maidservant died only last week.”

Again and again, Kisagotami received similar answers,

for in every household there had been death.

Kisagotami had thought she was the only person

who had lost a loved one.

Now she realized that death comes to all beings

and the dead are more plentiful than the living.

Finally, she accepted the death of her own child.

Later that evening, she cremated her baby by the river.

The next day she returned to the Buddha. He asked her,

“Have you brought the mustard seed?”

“No,” she replied and told him what had happened.

The Buddha then spoke to her on the transient and temporary

nature of all things.

Her mind became clear and her heart came to rest.

After she heard his Teaching,

Kisagotami decided to become a “practitioner of the Way.”

Buddha was once asked, “How are you different from other beings?” He

responded, “I was disturbed by old age, disease and death. That is what made me

seek for liberation; others were not so disturbed.”

To recognize not just one’s own person or personal fate, but the nature of this

whole world is suffering (like Kisagotami) makes one a ‘stream-enterer’ (sotapanna),

one who has ‘heard the teaching.’ A sotapanna has entered into the stream of

religious understanding29 and only on this basis begins to practice the Buddha

Dharma and walk the ‘liberating’ path of life.

Buddha was once asked, ‘For the sake of awakening and practicing the Dharma;

is it better to be born in the heaven realm, the hell realm, or the earth realm?’

Buddha replied,

“In the hell realm, the suffering is so intense and the pain so overwhelming that

the focus of one’s existence is avoiding more pain and one either tries to numb

oneself or escape the overwhelmingly painful conditions. Because of such

circumstances, beings in hell have little interest in the Dharma and do not practice

the way.

“In the heaven realm of the demi-gods, the length of life is so long and the

pleasures available so exquisite that beings who live there forget their situation will

ever come to an end and are therefore not interested in the Dharma or practice

of the way.

“It is only in the earth realm of human beings, ( a realm that is becoming more and more hellish)

the world that lies between the hell and heaven realms and combines both of their qualities, that a

person might become truly interested in the Dharma and practice of the way. In the human realm

of earth there exists the inevitable alternation of pleasure and pain and in that more balanced

circumstance one may awaken to the Buddha Dharma and practice of the Way. Therefore the

earth realm of human beings is the best realm to be born in to practice the Dharma and awaken

beyond suffering.”

Shakyamuni Buddha

Some Final Words

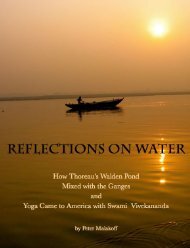

This has been a brief Kora of Koras, a consideration of some of the many

Koras of holy and sacred places all over the world. I originally wrote this as an

introduction for an Australian tour group that had come to Rewalsar and needed

some introduction to Tibetan Tantric Buddhism and the rest of our tour. It is

intended as an introduction to some of the universal principles of religion which

are often hidden in the millions of gods in India. It is a consideration of what we

are always circling.

It seems to me that we are all, already and always performing a primeval Kora,

the Kora of our sense of self; that is our highest building, our most sacred place.

However, in the highest teachings of Vedanta, our identification with ‘self ’ is the

denial of the Reality of ‘only God;’ and paradoxically, that ‘self ’ is the essential,

most necessary and most rarely performed of sacrifices.

Since this is only an introduction and not an in-depth consideration, I beg your

pardon and hope that the wheel of life turns well for you and everyone, but let us

remember that we are bound to a wheel that goes round in circles, what once was

up, inevitably will be down, what once was born will inevitably die, whatever we

once grasped, we must one day loose and what once was happy, will another day

taste of suffering, for this is the wheel of our lives.

So, why would I ‘wish you well’ if everything is always changing? Why would I

wish you well if as Buddha said that, ‘suffering is inevitable,’ indeed, that

‘suffering is the very nature of life itself.’ Why? Because he also added that all

suffering is not necessary.

We are on a boat floating down the river of life; a river filled with beauty, fear,

calm waters and rock-strewn rapids; we can merely float along, taking it as it

comes or we may seize the rudder and avoid this or that whirlpool, channel, rock

or waterfall.

Anyone who has gotten older knows that life is not completely under their control,

but we must not forget that it is also true we can avoid much of the suffering that

is not yet here.

May we use our intelligence to understand the laws of life, may we use our feeling

sense to discriminate between right and wrong, may we take refuge in the

company of good friends and teachers, may we seize the rudder of our boat and

direct our intention and use our will to live the best life we can for others and

ourselves; more than that we cannot do.

- Peter Malakoff

‘The winds of grace are always blowing;

we just need to put up our sails.’ - Brahmananda Saraswati

Footnotes

1 Fierce Compassion or wrathful compassion is representative of the nature of

Padmasambhava, his teaching and his actions.

2 “The concept of the prayer wheel is a physical manifestation of the phrase "turning the

wheel of Dharma," which describes the Path the Buddha taught. “Should there be any man or

woman who is illiterate and unable to read the sutra, they should then set up the prayer wheel

to help those who are illiterate to chant the sutra, and the effect is the same as reading the

sutra” . . . “Tibetan texts also say that the practice was taught by the Indian Buddhist masters,

Tilopa and Naropa, as well as the Tibetan masters Marpa and Milarepa.” - Wikipedia

3 Om Mani Padme Hum (Om the Jewel in the Lotus)

Across Northern India, Nepal and Tibet, you’ll often see this beloved mantra etched in stone.

Different schools of Buddhism offer a different interpretation of this mantra. One of my

favorites is that in the flowing, ever-changing world of the lotus - Padme, a symbol of beauty that

is rooted in the mud and blooms above the waters, is the never-changing mane or radiant

wisdom of Reality.

The Dalai Lama said, the meaning of this mantra is “great and vast” because all the teachings

of Buddha are wrapped up in this one phrase.

It is said that even the simple act of gazing upon the mantra will bring about the same

benevolent effects. Prayer wheels of various sizes, also called mani, are used for the meditation

of Om Mani Padme Hum as well.

Buddhist practitioners spin these large prayer wheels or small hand wheels while meditating

upon or chanting the mantra, simultaneously receiving its many blessings.

Tibetan Buddhists believe that each time a prayer wheel makes a complete rotation, it is

equivalent to the merit gained from completing a year-long retreat.

Mani Stones

4 Om Ah Hum Vajra Guru Padma Siddhi Hum

The three syllables Oṃ Āḥ Hūṃ have no conceptual meaning. They’re symbolic, and have

symbolic meanings.

Oṃ Āḥ Hūṃ Meaning

Oṃ is often regarded as being the primeval sound, and in fact the sound-symbol of reality

itself. It represents the universal principle of enlightenment. You can read about Om in more

detail on the page about the Om Shanti mantra.

Āḥ, in traditional explanations, is usually said to be connected with speech (more about that in

a moment) but in Sanskrit “ah” is a verb meaning “to express , signify ; to call (by name).” So it

suggests evoking, or calling forth, the manifestation of enlightenment.

Hūṃ is often thought of as representing the manifestation of enlightenment in the individual

human being. This may be a complete coincidence, but hum is similar to the first person

singular “aham,” which means of course “I.”

Often these three syllables are associated with body, speech, and mind respectively (i.e. the

whole of one’s being). So there’s a suggestion that we are saluting the qualities that

Padmasambhava represents with all of our hearts (and minds, and bodies).

The Final Hūṃ

Many Buddhist mantras start with Oṃ and end with Hūṃ.

One way you can think of this is that Oṃ represents the abstract principle of enlightenment, or

the potential for awakening that exists in the world and in our minds. Hūṃ on the other hand

represents our individual selves (hūṃ may be an ancient and non-standard equivalent of ahaṃ,

which is the Pali and Sanskrit word for “I” (the first person singular pronoun). The middle part

of the mantra is the invocation that connects us, as individuals, with enlightenment. In other

words we’re inviting enlightenment to transform us.

In this case it’s the qualities of Padmasambhava (as “the thunderbolt teacher” and the “lotus

realized one”) that are our bridge to enlightenment.

Vajra Guru Padma Siddhi Meaning

Vajra means thunderbolt, and represents the energy of the enlightened mind. It can also mean

diamond. The implication is that the diamond/thunderbolt can cut through anything. The

diamond is the indestructible object, while the thunderbolt is the unstoppable force. The vajra

also stands for compassion. While it may seem odd to have such a “masculine” object

representing compassion, this makes sense in esoteric Buddhism because compassion is active,

and therefore aligned with this masculine symbol. (The term “masculine” does not of course

imply that compassion is limited to males!)

Guru, of course, means a wise teacher. It comes from a root word, garu, which means “weighty.”

So you can think of the guru as one who is a weighty teacher. Padmasambhava is so highly

regarded in Tibetan Buddhism that he is often referred to as the second Buddha.

Padma means lotus, calling to mind the purity of the enlightened mind, because the lotus flower,

although growing in muddy water, is completely stainless. In the same way the enlightened

mind is surrounded by the greed, hatred, and delusion that is found in the world, and yet

remains untouched by it. The lotus therefore represents wisdom. Again, while westerners would

tend to assume that the flower represents compassion, the receptive nature of the flower gives it

a “feminine” status in esoteric Buddhism, and to the lotus is aligned with the “feminine” quality

of wisdom. And once again, there is no implication that wisdom is in any way limited to those

who are female. The words masculine and feminine here are used in a technical sense that’s

completely unrelated to biology.

And Siddhi means accomplishment or supernatural powers, suggesting the way in which those

who are enlightened can act wisely, but in ways that we can’t necessarily understand.

Padmasambhava is a magical figure, and in his biography there are many miracles and tussles

with supernatural beings.

- Wildmind Meditation

Dhanakosha, in the kingdom of Oddiyana. While some scholars locate this kingdom in the

Swat Valley area of modern-day Pakistan, a case on literary, archaeological, and

iconographical grounds can be made for placing it in the present-day state of Odisha in

India. - Wikipedia

5 Padmasambhava's teaching of Tantric Buddhism spread across not only Tibet but, north

India, Nepal and Bhutan beginning in the 8th century

6 Padmasambhava had two primary consorts in this life. One was Mandaravya and the other,

Yeshe Tsogyal. "According to hagiographies, Mandāravya was a wise, virtuous, and beautiful

princess, born to a royal couple in Zahor, northeastern India, amidst extraordinary signs. Her

father was an incarnation of the Buddha's father Śuddhodana, and her mother was a ḍākinī.

Mandāravyā was an incarnation of the female Buddha Paṇḍāravāsinī, the consort of Amitābha

Buddha. - The Treasury of Lives

7 Padmasambhava was born in what is today modern day Afghanistan but used to be part of

ancient India, called in Tibetan Ogyen or Oddiyana

8 Padmasambhava gave many prophecies about the future. Perhaps his most well known is:

“When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels, The people of Tibet will be scattered like

ants across the world And the Dharma will come to the land of the red man.”

9 This refers to the karmas of previous lifetimes.

10 Tibetan Tantric Buddhism differs from classical Buddhism taught by the Buddha and some

of these differences as well as ‘Tantra’ itself will be made more clear in the stories told here.

11 In addition to the relationship of Padmasmbhava and Mandaravya, her father, King

Arashadharhad, was Buddha’s father in his last life and Mandaravya had been Buddha’s

mother.

12 One of the meanings of ‘Tantra’ is ‘weaving’ or ‘woven.’

13 Dzogchen is considered to be the highest and most definitive path of liberation in Tibetan

Buddhism.

14 ‘Siddhis’ are material, paranormal, supernatural, or otherwise magical powers, abilities, and

attainments that are the products of advancement through sadhanas or religious practices,

meditation and yoga.

15 Carl Jung explored the myths of the world and found their interpretation to be based on

eternal archetypal principles, not actual historical occurrences. Joseph Campbell wrote many

books on this subject such as, The Power of Myth, The Hero with a Thousand Faces and

Oriental Mythology.

16 In Washington D.C., a city dedicated to ‘politics,’ there is no building taller than the

Washington monument There are very few exceptions to this principle of the tallest building in

town representing the dominant theme of a culture.

17 Technology has created a huge and revolutionary phenomena in our world today. It has

brought about tremendous changes regarding religion, politics and business, but it too has its

liability. As Buckminster Fuller once said, ‘We now live in a time where because of technology

and its ability to accomplish so much more, using less and less materials and input of energy,

mankind will bring about a utopia on earth or destroy ourselves in oblivion.’

18 Solar power is good for the ecosystem of our world but it is engaged with on a

‘transactional’ or business-like basis. The sun is a power source, not the supreme giver of life

itself.

19 ’ecos’ is from the Greek word for, ‘household’

20 There were four ‘stages of life’ defined in the Vedic culture of ancient India and each of

them had distinct obligations, rules and debts to be paid. They are: 1) Brahmacharya- the

student stage of life when one would submit ones life to a teacher and learn about life through

study and service. 2) Grihastya- the householder stage of life in which one would make a living,

marry and have children; the grihastyas were the support of all the other stages. 3)

Vanaprastya- the now aging man and wife would leave their family duties and retire to the

‘Vana’ or forest and devote their time to religious practice and pilgrimage 4) Sanyas, or the

renunciation and shaking off of all obligations.

21 Technology is a huge and revolutionary phenomena in our world today. It has brought

about tremendous changes regarding religion, the support of all the other stages. 3)

Vanaprastya- the now aging man and wife would leave their family duties and retire to the

‘Vana’ or forest and devote their time to religious practice and 4) Sanyas, or the renunciation

and shaking off of all obligations.

22 ’Samadhi’ is the balanced (sama) state of vision (dhi) - vision directed neither inwardly or

outwardly. ‘Maha’ or ‘Great’ samadhi refers to the death of an enlightened being who is always

and already in this state of being.

23 Enlightened beings are usually buried, not cremated, as their body is thought to radiate the

essence of their state after death.

24 ‘ Advaita’ means ‘not two’ and is often referred to as ‘non-duality’ and is often associated

with ‘Advaita Vedanta.’ It is The paradoxical, not graspable by the mind, Realization of nonseparateness:

‘Neither one God or many gods; Only God.’

25 ‘Rohtang’ means ‘pile of corpses,’ attesting to the many people who died on this high pass in

the many storms that would suddenly arise. The Rohtang was a well traveled pass that travelers

on the Silk Road would use to come down off the Tibetan plateau to Delhi and the plains of

India.

26 Nalanda was a large Buddhist monastery and school located in the kingdom of Magadha or

modern day Bihar. At its peak, the school attracted scholars and students from near and far with

some traveling from Tibet, China, Korea and Central Asia. -Wikipedia

27 There are terrible descriptions of rituals for smashing and killing and doing all sorts of

horrible things with sharp weapons. Some scriptures say that these are supposed to be kept

secret because they could be completely misunderstood as meaning some horrible act, and that

practitioners would actually go out and kill people.

28 For Mahasiddhas, the cremation ground or other ‘horrible’ places are not merely a

hermitage; Mahasiddhas can also be discovered or revealed in completely terrifying mundane

environments where practitioners find themselves desperate and depressed, where conventional

worldly aspirations have become devastated by grim reality. This is demonstrated in the sacred

biographies of the great Mahasiddhas of the Vajrayāna tradition. Tilopa attained realization as

a grinder of sesame seeds and a procurer for a prominent prostitute. Sarvabhakṣha was an

extremely obese glutton, Gorakṣha was a cowherd in remote climes, Taṅtepa was addicted to

gambling, and Kumbharipa was a destitute potter. These circumstances were called charnel

grounds because they were despised in Indian society and the Mahasiddhas were viewed as

failures and marginal and defiled beings. - Wikipedia

29 The first moment of attainment is termed the path of stream-enterer (sotāpatti-magga). The

person who experiences it is called a stream-enterer (sotāpanna). The sotāpanna is said to attain

an intuitive grasp of the Dharma and unshakable confidence in the Buddha, Dharma, and

Sangha. The sotapanna is said to have "opened the eye of the Dharma because they have

realized that whatever arises will cease (impermanence).

- Wikipedia