Like Leaves in Autumn by Carlo Pirozzi et al sampler

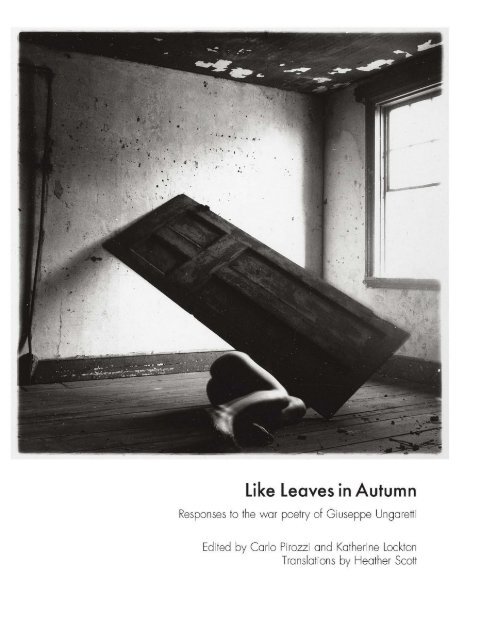

Published to mark the first centenary of Italy’s entry into the Great War, Like Leaves in Autumn features 21 original Italian poems by Giuseppe Ungaretti, with new English translations by Heather Scott. These are set alongside 21 new poems by contemporary Scottish poets writing in response to Ungaretti, and are illustrated with striking black-and-white artworks from the ARTIST ROOMS collection, owned by National Galleries of Scotland and Tate.

Published to mark the first centenary of Italy’s entry into the Great War, Like Leaves in Autumn features 21 original Italian poems by Giuseppe Ungaretti, with new English translations by Heather Scott. These are set alongside 21 new poems by contemporary Scottish poets writing in response to Ungaretti, and are illustrated with striking black-and-white artworks from the ARTIST ROOMS collection, owned by National Galleries of Scotland and Tate.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

giuseppe ungar<strong>et</strong>ti (1888–1970) is one of Europe’s greatest modernist<br />

po<strong>et</strong>s. He was <strong>al</strong>so a writer, literary critic, journ<strong>al</strong>ist and university<br />

professor <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y and <strong>in</strong> Brazil. He was born and raised <strong>in</strong> Alexandria,<br />

Egypt, to an It<strong>al</strong>ian family from Tuscany. At the age of 24, he moved<br />

to Paris, where he associated with prom<strong>in</strong>ent artists of the European<br />

avant garde. Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti fought on the It<strong>al</strong>ian front from 1915 to 1917,<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> some of the bloodiest episodes of the Great War, dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

which time much of his greatest po<strong>et</strong>ry was written. Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti later<br />

worked as a correspondent for Il Popolo d’It<strong>al</strong>ia, a politic<strong>al</strong> daily paper<br />

founded <strong>by</strong> Benito Mussol<strong>in</strong>i. In 1936, he moved to Brazil, where he<br />

took up a teach<strong>in</strong>g post at São Paulo University. He cont<strong>in</strong>ued to teach,<br />

travel and write throughout his life.<br />

The 21 poems <strong>by</strong> Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti <strong>in</strong> the present anthology were selected<br />

from the collection, L’Allegria (The Joy, 1931). The orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> title of the<br />

book was Allegria di naufragi (The Joy of Shipwrecks), first published<br />

<strong>in</strong> 1919. This collection <strong>in</strong> turn <strong>in</strong>cluded, <strong>in</strong> one of its sections, a t<strong>in</strong>y<br />

group of lyric<strong>al</strong> poems entitled Il Porto Sepolto (The Buried Harbour)<br />

written <strong>in</strong> the trenches dur<strong>in</strong>g the First World War on ‘scraps of paper<br />

s<strong>al</strong>vaged from the packag<strong>in</strong>g of bull<strong>et</strong>s’. The latter had been published<br />

separately <strong>in</strong> 1916 <strong>in</strong> only 80 copies. The 1919 volume underwent<br />

many corrections and additions before the 1931 publication, which<br />

itself <strong>al</strong>so underwent a series of sm<strong>al</strong>l changes, until <strong>in</strong> 1942 a f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong><br />

text appeared. The Joy, like Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s entire critic<strong>al</strong> essays, prose and<br />

translations, is collected <strong>in</strong> sever<strong>al</strong> volumes published <strong>by</strong> Mondadori,<br />

entitled Vita d’un uomo (The Life of a Man).

<strong>Like</strong> <strong>Leaves</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Autumn</strong><br />

Responses to the war po<strong>et</strong>ry<br />

of Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

Edited <strong>by</strong><br />

carlo pirozzi and kather<strong>in</strong>e lockton<br />

Translations <strong>by</strong> Heather Scott<br />

Luath Press Limited<br />

EDINBURGH<br />

www.luath.co.uk

Published <strong>in</strong> 2015 <strong>by</strong> Luath Press Ltd. <strong>in</strong> Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh, the world’s first<br />

unesco City of Literature, <strong>in</strong> association with the Scottish Po<strong>et</strong>ry Library<br />

and the It<strong>al</strong>ian Cultur<strong>al</strong> Institute, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh, and with the endorsement<br />

of the City of Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh Council and the City of Florence Council.<br />

isbn: 978-1-910021-79-8<br />

The paper used <strong>in</strong> this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlor<strong>in</strong>e pulps<br />

produced <strong>in</strong> a low energy, low emissions manner from renewable forests.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted and bound <strong>by</strong> The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield<br />

Types<strong>et</strong> <strong>in</strong> Sabon <strong>by</strong> 3btype.com<br />

Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti poems taken from<br />

Vita d’un uomo. Tutte le poesie (The Life of a Man. All poems)<br />

© Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano.<br />

All poems <strong>by</strong> Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti <strong>in</strong> this book, apart from the poem<br />

Me a Craitur, have been translated <strong>by</strong> Heather Scott, 2015 © Heather Scott.<br />

Eanna O’Ce<strong>al</strong>lacha<strong>in</strong> (Head of It<strong>al</strong>ian, University of Glasgow) provided<br />

assistance revis<strong>in</strong>g the translations from Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti <strong>by</strong> Heather Scott.<br />

Me a Craitur was written <strong>by</strong> Tom Scott.<br />

The poem was published <strong>in</strong> The Collected Shorter Poems of Tom Scott<br />

(Agenda/Chapman Publications 1993)<br />

© Heather Scott.<br />

All other poems and texts © the contributors.<br />

The works of art <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this volume have been selected from artist rooms.<br />

artist rooms is jo<strong>in</strong>tly owned <strong>by</strong> Tate and the Nation<strong>al</strong> G<strong>al</strong>leries of Scotland and was<br />

established through the d’Offay Donation <strong>in</strong> 2008, with the assistance of the Nation<strong>al</strong><br />

Heritage Memori<strong>al</strong> Fund, the Art Fund, and the Scottish and British Governments.

To commemorate the wars of my grandfathers and the<br />

wait<strong>in</strong>g of my grandmothers.<br />

To my grandfather Ga<strong>et</strong>ano (1916–1955), and my grandfather<br />

Antonio (1921–1978), the former a survivor of<br />

imprisonment <strong>in</strong> Russia, the latter a survivor of conflict<br />

<strong>in</strong> North Africa, both dur<strong>in</strong>g the Second World War.<br />

To my grandmothers Ad<strong>al</strong>gisa (1926–1990), and Iolanda<br />

(1921) who created everyth<strong>in</strong>g from noth<strong>in</strong>g. Iolanda, at<br />

93 years old, still confronts the passage of time fearlessly.<br />

C.P.<br />

For my mum and dad; Rosemary & John Lockton<br />

i.m. D<strong>in</strong>na Lanuza (1914–2007)<br />

who remembered every year.<br />

K.L.

Contents<br />

Preface <strong>by</strong> <strong>Carlo</strong> <strong>Pirozzi</strong> 11<br />

Introductions<br />

War and Po<strong>et</strong>ry 13<br />

john burnside<br />

A Note on Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s Life and Po<strong>et</strong>ry 17<br />

carlo pirozzi<br />

The Buried Harbour of Dreams: Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

<strong>in</strong> Alexandria of Myths 23<br />

luca scarl<strong>in</strong>i<br />

Respond<strong>in</strong>g to Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti 26<br />

kather<strong>in</strong>e lockton<br />

Interpr<strong>et</strong><strong>in</strong>g Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti: 21 works of Art 30<br />

lara demori and neil cox<br />

Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s Poems and Translations<br />

Works of Art<br />

Contributors’ Biographies<br />

Poems and Commentaries <strong>by</strong> Scottish po<strong>et</strong>s<br />

Eterno – Etern<strong>al</strong> 35<br />

Studien – Der Mensch (Grandmother and Child)<br />

<strong>by</strong> August Sander 37<br />

By remember<strong>in</strong>g I fold myself <strong>in</strong>to you, <strong>by</strong> J.L. Williams 38<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> J.L. Williams 39<br />

Noia – Ennui 41<br />

David Hockney <strong>by</strong> Robert Mappl<strong>et</strong>horpe 43<br />

The Northern Cycles, <strong>by</strong> Richie McCaffery 44<br />

7

Commentary Richie McCaffery 45<br />

Levante – Levant 47<br />

Girl <strong>in</strong> a Fairground Caravan <strong>by</strong> August Sander 49<br />

The two girls were <strong>al</strong>ways s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>by</strong> Richard Price 50<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Richard Price 51<br />

Nasce forse – Perhaps a River Rises 53<br />

Johannis Nacht gef<strong>al</strong>lene Bilder (The Secr<strong>et</strong> Life of Plants)<br />

<strong>by</strong> Anselm Kiefer 55<br />

Nasce forse, <strong>by</strong> Alan Gillis 56<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Alan Gillis 57<br />

In memoria – In Memoriam 59<br />

Untitled <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 61<br />

The Ann<strong>al</strong>s, <strong>by</strong> Gerry Cambridge 62<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Gerry Cambridge 63<br />

Il porto sepolto – The Buried Harbour 65<br />

Heroische S<strong>in</strong>nbilder (Heroic Symbols) <strong>by</strong> Anselm Kiefer 67<br />

The Pool, <strong>by</strong> Vicki Feaver 68<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Vicki Feaver 69<br />

L<strong>in</strong>doro di deserto – L<strong>in</strong>doro of the Desert 71<br />

Untitled (FW crouch<strong>in</strong>g beh<strong>in</strong>d umbrella)<br />

<strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 73<br />

Break<strong>in</strong>g the Silence, <strong>by</strong> Mandy Haggith 74<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Mandy Haggith 75<br />

Veglia – Vigil 77<br />

With Dead Head <strong>by</strong> Damien Hirst 79<br />

Still vigil, <strong>by</strong> Christ<strong>in</strong>e De Luca 80<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Christ<strong>in</strong>e De Luca 81<br />

Fratelli – Brothers 83<br />

Four hands <strong>by</strong> Bill Viola 85<br />

Brothers, <strong>by</strong> Jillian Fenn 86<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Jillian Fenn 87<br />

8

Sono una creatura – I am a Creature / Me a Craitur<br />

(version <strong>by</strong> Tom Scott <strong>in</strong> Scots) 89<br />

Film Noir (Fly) <strong>by</strong> Douglas Gordon 91<br />

War Memori<strong>al</strong>, Afton V<strong>al</strong>ley, <strong>by</strong> Rab Wilson 92<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Rab Wilson 93<br />

In dormiveglia – H<strong>al</strong>f Asleep 95<br />

Untitled <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 97<br />

Night, <strong>by</strong> Miriam Gamble 98<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Miriam Gamble 99<br />

I fiumi – The Rivers 101<br />

Untitled <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 103<br />

Fresh Founta<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>by</strong> V<strong>al</strong>erie Gillies 104<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> V<strong>al</strong>erie Gillies 105<br />

Sonnolenza – Drows<strong>in</strong>ess 107<br />

Untitled <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 109<br />

Desert, <strong>by</strong> Alistair F<strong>in</strong>dlay 110<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Alistair F<strong>in</strong>dlay 111<br />

San Mart<strong>in</strong>o del Carso – San Mart<strong>in</strong>o del Carso 113<br />

Untitled <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 115<br />

Believed to be buried <strong>in</strong> this Cem<strong>et</strong>ery,<br />

<strong>by</strong> Robert Alan Jamieson 116<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Robert Alan Jamieson 117<br />

Distacco – D<strong>et</strong>achment 119<br />

Lowell Smith <strong>by</strong> Robert Mappl<strong>et</strong>horpe 121<br />

No-one mentioned it, <strong>by</strong> Tessa Ransford 122<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Tessa Ransford 123<br />

Nost<strong>al</strong>gia – Nost<strong>al</strong>gia 125<br />

Eel Series, Roma, May 1977–1978 <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 127<br />

Shoes, <strong>by</strong> Claudia Daventry 128<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Claudia Daventry 129<br />

9

It<strong>al</strong>ia – It<strong>al</strong>y 131<br />

Iggy Pop <strong>by</strong> Robert Mappl<strong>et</strong>horpe 133<br />

As an Eadailt, <strong>by</strong> Aonghas MacNeacail 134<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Aonghas MacNeacail 135<br />

Commiato – Leave-tak<strong>in</strong>g 137<br />

Space 2 , Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–78<br />

<strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 139<br />

Birdsong <strong>in</strong> the War-Zone, <strong>by</strong> Anna Crowe 140<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Anna Crowe 141<br />

Nat<strong>al</strong>e – Christmas 143<br />

Heroische S<strong>in</strong>nbilder (Heroic Symbols) <strong>by</strong> Anselm Kiefer 145<br />

My Shoulders, <strong>by</strong> Jane McKie 146<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Jane McKie 147<br />

Matt<strong>in</strong>a – Morn<strong>in</strong>g 149<br />

Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 <strong>by</strong> Francesca Woodman 151<br />

D’immenso, <strong>by</strong> John Burnside 152<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> John Burnside 153<br />

Soldati – Soldiers 155<br />

Plank Piece I–II <strong>by</strong> Charles Ray 157<br />

Civilians, <strong>by</strong> Rob A. Mackenzie 158<br />

Commentary <strong>by</strong> Rob A. Mackenzie 159<br />

A short bibliography of Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s works 161<br />

Photographic Credits 163<br />

Authors’ and Editors’ Biographies 165<br />

Acknowledgements 167<br />

10

Preface<br />

carlo pirozzi<br />

The present publication is part of my project, ‘The Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti Multi-<br />

Media War Project’ (um-mw), which is <strong>in</strong>tended both to commemorate<br />

the first centenary of It<strong>al</strong>y’s entry <strong>in</strong>to the Great War and to celebrate<br />

the 50 years s<strong>in</strong>ce Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh and Florence were first tw<strong>in</strong>ned.<br />

The um-mw Project is <strong>in</strong> partnership with the It<strong>al</strong>ian Cultur<strong>al</strong><br />

Institute and the Scottish Po<strong>et</strong>ry Library <strong>in</strong> Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh and has the<br />

endorsement of Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh City Council and Florence City Council.<br />

As well as this new anthology, <strong>Like</strong> the <strong>Leaves</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Autumn</strong> co-edited<br />

with Kather<strong>in</strong>e Lockton, the um-mw br<strong>in</strong>gs tog<strong>et</strong>her new film,<br />

animation, music, dance performance and sculpture <strong>in</strong> response to the<br />

poems of Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this present book.<br />

Specific<strong>al</strong>ly, <strong>in</strong> addition to the current book, the outcomes of this<br />

project are:<br />

• A new film directed <strong>by</strong> the Scottish artist Alastair Cook,<br />

founder of the <strong>in</strong>ternation<strong>al</strong> po<strong>et</strong>ry-film and festiv<strong>al</strong> project,<br />

Filmpoem. Alastair has chosen to <strong>in</strong>terpr<strong>et</strong> ‘D’immenso’ <strong>by</strong><br />

John Burnside, itself <strong>in</strong>spired <strong>by</strong> Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s ‘Matt<strong>in</strong>a’.<br />

‘D’immenso’ can be seen at www.filmpoem.com<br />

• New scores composed <strong>by</strong> young musicians from the<br />

Com po si tion Department of the Roy<strong>al</strong> Conservatoire of<br />

Scotland, Glasgow, under the supervision of Alistair<br />

MacDon<strong>al</strong>d (Director of the Electroacoustic Studios at the<br />

Roy<strong>al</strong> Scottish Academy of Music and Drama <strong>in</strong> Glasgow)<br />

and students from the Music Department at the University<br />

of St Andrews, under the super vision of Bede Williams<br />

(Teach<strong>in</strong>g Fellow and New Music Co-ord<strong>in</strong>ator).<br />

• New animated films created <strong>by</strong> students from the Animation<br />

Department, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh College of Art, under the<br />

supervision of Jared Taylor (Programme Director, Animation<br />

at Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh College of Art).<br />

11

• A new sculpture <strong>by</strong> a young Scots-It<strong>al</strong>ian artist, GianPiero<br />

Franchi, from Gray’s School of Art, Robert Gordon<br />

University (rgu), Aberdeen.<br />

These artworks will be shown <strong>in</strong> conjunction with read<strong>in</strong>gs as part of<br />

sever<strong>al</strong> 2015 book launches <strong>in</strong> St Andrews, Glasgow, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh and<br />

Florence.<br />

12 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

War and Po<strong>et</strong>ry<br />

john burnside<br />

There’s no way of be<strong>in</strong>g sure about this, but I suspect I was the only<br />

13-year-old Wagnerite <strong>in</strong> my East Midlands <strong>in</strong>dustri<strong>al</strong> New Town back<br />

<strong>in</strong> the late 1960s. Introduced to the work <strong>by</strong> a brilliant music teacher,<br />

and supported <strong>by</strong> a k<strong>in</strong>dly priest, who not only lent me records but<br />

<strong>al</strong>so persuaded my parents to obta<strong>in</strong> a piano, I became one of those<br />

child eccentrics who wander around humm<strong>in</strong>g snatches of Lohengr<strong>in</strong><br />

while try<strong>in</strong>g to avoid becom<strong>in</strong>g part of the playground soci<strong>al</strong> scene.<br />

And, with <strong>al</strong>l the naïv<strong>et</strong>é of the child autodidact, I assumed that this<br />

Richard Wagner must, <strong>by</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition, have been a wonderful character,<br />

a deeply spiritu<strong>al</strong> soul, with a love of justice and k<strong>in</strong>dness <strong>in</strong> his heart<br />

for <strong>al</strong>l. It was as much to justify this view as a matter of curiosity that<br />

I began look<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to his biography, but it didn’t take long to become<br />

disabused of my rosy picture of the man. Indignant, I compla<strong>in</strong>ed to<br />

my teacher: why had he <strong>in</strong>troduced me to the work of such a seem<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

vile man? And how could such a person have composed a work like<br />

Parsif<strong>al</strong>?<br />

I only r<strong>et</strong>ail this anecdote of youthful dismay <strong>in</strong> hopes of mak<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

serious po<strong>in</strong>t – for it is not only the young who suffer such disa p-<br />

po<strong>in</strong>tments. All through our lives, we are puzzled <strong>by</strong> the knowledge<br />

that, <strong>in</strong> one way or another, our favourite artists (not to mention our<br />

other heroes) were, or are, deeply flawed human be<strong>in</strong>gs and it is hard<br />

to be forgiv<strong>in</strong>g of the admired novelist who, <strong>in</strong> spite of hav<strong>in</strong>g written<br />

some of the most perceptive prose ever committed to paper, turns out<br />

to have been a Nazi, or the respected philosopher who lends his<br />

support to a bloody tot<strong>al</strong>itarian regime. It is the politic<strong>al</strong> dimension<br />

here that <strong>al</strong>ways seems to matter – we are more ready to forgive<br />

person<strong>al</strong> fail<strong>in</strong>gs: the junkies and drunks, the seri<strong>al</strong> adulterers, even the<br />

man who shoots his wife <strong>in</strong> the head while play<strong>in</strong>g an impromptu game<br />

of William Tell are <strong>al</strong>l rescued from ignom<strong>in</strong>y <strong>by</strong> the qu<strong>al</strong>ity of their<br />

works. In such cases, we are able to say: yes, they may have been<br />

terrible people, but look at what they made.<br />

Politic<strong>al</strong> s<strong>in</strong>s are harder to s<strong>et</strong> aside, for some of us at least, especi<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

13

when there is evidence of support for Fascism. In a perfect world, the<br />

rul<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple might be George Orwell’s contention that ‘the impulse<br />

of every writer is to keep out of politics. What he [sic] wants is to be<br />

left <strong>al</strong>one so that he can go on writ<strong>in</strong>g books <strong>in</strong> peace.’ However, as<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation technology improved through the last century, and people,<br />

<strong>in</strong> the developed world at least, became more aware of the astonish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

levels of corruption and <strong>in</strong>justice that surrounded them on <strong>al</strong>l sides, it<br />

was to become more and more obvious, to Orwell and to others, ‘that<br />

this ide<strong>al</strong> is no more practic<strong>al</strong> than that of the p<strong>et</strong>ty shop-keeper who<br />

hopes to preserve his <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> the te<strong>et</strong>h of the cha<strong>in</strong>-stores…<br />

It is not possible for any th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g person to live <strong>in</strong> such a soci<strong>et</strong>y as our<br />

own without want<strong>in</strong>g to change it.’ In the 20th century, and especi<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

after the First World War, writers from a wider range of soci<strong>al</strong> and<br />

cultur<strong>al</strong> backgrounds than ever before felt the need to c<strong>al</strong>l, not just for<br />

thought, but for action. Wyndham Lewis worried about this tendency:<br />

‘With <strong>al</strong>l the energy at their dispos<strong>al</strong>,’ he said, ‘a majority of the modern<br />

<strong>in</strong>tellectu<strong>al</strong>s have striven to excite to passionate action – not to exhort<br />

to reflection or moderation, not applied to the reason, but <strong>al</strong>ways to<br />

the emotions: they have po<strong>in</strong>ted passionately to the battlefield, the<br />

barricade, the place of execution, not to the life of reason, to what is<br />

harmonious and beautifully ordered. This is <strong>in</strong> fact the b<strong>et</strong>ray<strong>al</strong>.’<br />

However, if there is one th<strong>in</strong>g we can learn from history it is that <strong>al</strong>l<br />

k<strong>in</strong>ds of b<strong>et</strong>ray<strong>al</strong> are possible. Those writers who rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>al</strong>one <strong>in</strong> order<br />

to ‘go on writ<strong>in</strong>g books <strong>in</strong> peace’ are more likely to be well-regarded<br />

than either the revolutionary who c<strong>al</strong>ls for immediate action to change<br />

a corrupt world, or the k<strong>in</strong>d of arch-conservative that Lewis eventu<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

became (for what he presented as good reasons – reasons he shared, <strong>in</strong><br />

many ways, with many of the more highly respected writers – T.S. Eliot,<br />

say – who lived through the first h<strong>al</strong>f of the last century: ‘Darw<strong>in</strong>,<br />

Voltaire, Newton, Raphael, Dante, Epict<strong>et</strong>us, Aristotle, Sophocles,<br />

Plato, Pythagoras: <strong>al</strong>l shedd<strong>in</strong>g their light upon the same wide, well-lit<br />

Greco-Roman highway, with the same k<strong>in</strong>d of sane and steady ray –<br />

one need only mention these to recognise that it was at least excusable<br />

to be concerned about the threat of ext<strong>in</strong>ction to that tradition.’) Y<strong>et</strong><br />

are not those stay-at-home writers to whom Orwell refers <strong>in</strong> danger of<br />

b<strong>et</strong>ray<strong>in</strong>g an essenti<strong>al</strong> part of their humanity, if they simply make<br />

books, while the corrupt and the unjust carry on bus<strong>in</strong>ess as usu<strong>al</strong>?<br />

14 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

In the pages of literary history, Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti is one of those<br />

who, like Hamsun or Pound, was, at the very least, seduced <strong>by</strong> Fascism<br />

– and for some, this rema<strong>in</strong>s a huge problem <strong>in</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g at the work.<br />

Y<strong>et</strong> (though I would hasten to note that I do not speak for any of the<br />

other po<strong>et</strong>s who responded to his work here), at least some of the<br />

choices he made can be seen as the expression of a desire for decisive<br />

action, action that makes som<strong>et</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g happen – and there are historic<strong>al</strong><br />

occasions when anyth<strong>in</strong>g happen<strong>in</strong>g, anyth<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>al</strong>l, comes to be seen<br />

as preferable to the status quo, as Blaise Cendrars, another v<strong>et</strong>eran of<br />

the First World War po<strong>in</strong>ts out: ‘For action, whatever its immediate<br />

purpose, <strong>al</strong>so implies relief at do<strong>in</strong>g som<strong>et</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g, anyth<strong>in</strong>g, and the joy<br />

of exertion. This is the optimism that is <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong>, and proper and<br />

<strong>in</strong>dispensable to action, for without it noth<strong>in</strong>g would ever be undertaken.<br />

It <strong>in</strong> no way suppresses the critic<strong>al</strong> sense or clouds the judgment.<br />

On the contrary this optimism sharpens the wits, it creates a certa<strong>in</strong><br />

perspective and, at the last moment, l<strong>et</strong>s <strong>in</strong> a ray of perpendicular light<br />

which illum<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>al</strong>l one’s previous c<strong>al</strong>culations, cuts and shuffles<br />

them and de<strong>al</strong>s you the card of success, the w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g number.’ History<br />

tells us that Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti was on the wrong side, and the action he<br />

supported – know<strong>in</strong>gly supported – caused terrible harm. So, if the man<br />

was a Fascist, why do we cont<strong>in</strong>ue read<strong>in</strong>g? I th<strong>in</strong>k it is because Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

is a po<strong>et</strong> who f<strong>in</strong>ds, <strong>in</strong> moments of extreme danger, that light to which<br />

Cendrars refers. Poem after poem of those he composed <strong>in</strong> the trenches<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ds that perpendicular ray, seek<strong>in</strong>g out and illum<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g the immense,<br />

the <strong>et</strong>ern<strong>al</strong>, just as it illum<strong>in</strong>ated the transient and the fragile.<br />

At the same time, it could tell us som<strong>et</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g about the re<strong>al</strong> worth of<br />

art, that we still f<strong>in</strong>d Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s war poems so powerful, even uplift<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Back <strong>in</strong> the music classroom, when I compla<strong>in</strong>ed about the f<strong>al</strong>lible<br />

nature of artistic genius, my teacher had noth<strong>in</strong>g to offer <strong>in</strong> response,<br />

other than a wry smile – at least to beg<strong>in</strong> with. Later, though, he found<br />

me out and gave me a picture, a photograph that looked to have been<br />

clipped from a book or a magaz<strong>in</strong>e. It was a picture of what I knew<br />

as a water lily, though he c<strong>al</strong>led it a Lotus. He expla<strong>in</strong>ed that, <strong>in</strong> some<br />

cultures, it is considered sacred because it grows <strong>in</strong> the murkiest pools,<br />

its root buried <strong>in</strong> mud and filth, y<strong>et</strong> it rises from that dark, muddy<br />

water to produce a clean, prist<strong>in</strong>e flower when it reaches the sunlight.<br />

That was <strong>al</strong>l he told me, but he l<strong>et</strong> me keep the photograph and, after<br />

war and po<strong>et</strong>ry 15

a while, I came to see what he was g<strong>et</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g at – which was not to forgive,<br />

or to forg<strong>et</strong>, anyth<strong>in</strong>g that any particular <strong>in</strong>dividu<strong>al</strong> did or did not do,<br />

<strong>in</strong> historic<strong>al</strong> terms, but to v<strong>al</strong>ue the work itself, for its own sake and<br />

for what it does <strong>in</strong> the world. It seemed to me, then, that everyth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

– even a flower – has consequences, often unforeseen or un<strong>in</strong>tended<br />

and it is those consequences that matter, not the politic<strong>al</strong> folly or<br />

wisdom of the po<strong>et</strong>. So, while it may seem naïve, this is how I choose<br />

to read Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s war po<strong>et</strong>ry today: the work itself expresses an<br />

<strong>in</strong>tense feel<strong>in</strong>g for life, that sense of the miraculous <strong>in</strong> which, as<br />

Cendrars puts it, ‘only a soul full of despair can ever atta<strong>in</strong> serenity<br />

and, to be <strong>in</strong> despair, you must have loved a good de<strong>al</strong> and still love<br />

the world’.<br />

16 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

A Note on Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s Life and Po<strong>et</strong>ry<br />

carlo pirozzi<br />

Giuseppe Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti (1888–1970) is among the most <strong>in</strong>fluenti<strong>al</strong> It<strong>al</strong>ian<br />

po<strong>et</strong>s of 20th-century European literature. He stands <strong>al</strong>ongside Eugenio<br />

Mont<strong>al</strong>e (1896–1981; 1975 Nobel prize) and S<strong>al</strong>vatore Quasimodo<br />

(1901–1968; 1959 Nobel prize). Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti was a writer, literary critic,<br />

journ<strong>al</strong>ist and university professor <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y and <strong>in</strong> Brazil.<br />

He can certa<strong>in</strong>ly be considered one of the fathers of modern po<strong>et</strong>ry,<br />

<strong>al</strong>ong with T.S. Eliot (they were both born <strong>in</strong> 1888), Ezra Pound, some<br />

of whose poems Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti translated <strong>in</strong>to It<strong>al</strong>ian, and lead<strong>in</strong>g figures<br />

<strong>in</strong> French po<strong>et</strong>ry, like Paul V<strong>al</strong>éry, André Br<strong>et</strong>on and Guillaume<br />

Apoll<strong>in</strong>aire. With Mont<strong>al</strong>e and Quasimodo, Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti drew up a<br />

bluepr<strong>in</strong>t for early 20th-century It<strong>al</strong>ian po<strong>et</strong>ry, whose peculiarity was<br />

the <strong>in</strong>vention of a revolutionary, <strong>in</strong>novative and consciously obscure<br />

language, reduced to its essenti<strong>al</strong>s – ‘herm<strong>et</strong>ic’ as it was dubbed at the<br />

time. This language was proposed as a po<strong>et</strong>ic manifesto and a response<br />

to the sense of existenti<strong>al</strong> unease experienced <strong>by</strong> those liv<strong>in</strong>g under<br />

dictatorships and through two world wars.<br />

Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti was born <strong>in</strong> Alexandria, Egypt <strong>in</strong> 1888 <strong>in</strong>to an It<strong>al</strong>ian<br />

family orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>ly from Lucca <strong>in</strong> Tuscany. In 1912, at 24 years old, he<br />

left Egypt for the first time and moved to Paris. Before s<strong>et</strong>tl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Paris,<br />

he stopped off <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y, where he had a brief but memorable stay,<br />

visit<strong>in</strong>g Lucca, Florence and the surround<strong>in</strong>g areas. Once <strong>in</strong> Paris he<br />

attended university courses taught <strong>by</strong> illustrious professors, such as the<br />

philosopher Henri Bergson, at the Collège de France and the Sorbonne.<br />

While <strong>in</strong> Paris he m<strong>et</strong> and associated with some of the outstand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

figures of the avant-garde: Guillaume Apoll<strong>in</strong>aire, Georges Braque,<br />

Giorgio De Chirico, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso and, dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

their frequent trips to Paris, the Futurists Umberto Boccioni, Filippo<br />

Tommaso Mar<strong>in</strong><strong>et</strong>ti, Giovanni Pap<strong>in</strong>i, Aldo P<strong>al</strong>azzeschi and Ardengo<br />

Soffici. R<strong>et</strong>urn<strong>in</strong>g to It<strong>al</strong>y <strong>in</strong> 1914, he jo<strong>in</strong>ed the army the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

year, just after It<strong>al</strong>y had entered the war. Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti took part <strong>in</strong> some<br />

of the bloodiest episodes of the Great War, fight<strong>in</strong>g on the It<strong>al</strong>ian front,<br />

on the Carso and <strong>al</strong>ong the Isonzo River from 1915 to 1917. The<br />

17

carnage was terrible, with more than 300,000 It<strong>al</strong>ians and Austro-<br />

Hungarian soldiers los<strong>in</strong>g their lives, but Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti came through the<br />

conflict unscathed.<br />

After the war, Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti s<strong>et</strong>tled <strong>in</strong> Rome with his family, work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

the Press Office at the It<strong>al</strong>ian M<strong>in</strong>istry of Foreign Affairs and as a<br />

correspondent for Il Popolo d’It<strong>al</strong>ia, an important politic<strong>al</strong> daily paper<br />

founded <strong>by</strong> Benito Mussol<strong>in</strong>i. His position at the M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>al</strong>lowed him<br />

to travel cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>al</strong>ly and he was able to lecture at various European<br />

universities as well as further afield. In 1936 he moved to Brazil, where<br />

he took up a teach<strong>in</strong>g post at São Paulo University. Dur<strong>in</strong>g his stay <strong>in</strong><br />

South America, which lasted until 1942, he managed to forge l<strong>in</strong>ks<br />

with some of the lead<strong>in</strong>g Brazilian po<strong>et</strong>s, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a young V<strong>in</strong>icius<br />

de Moraes, for whom he translated sever<strong>al</strong> poems. Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti then<br />

r<strong>et</strong>urned to Rome, where at La Sapienza University, he was given the<br />

Chair of It<strong>al</strong>ian Literature. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the Roman years he cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

travell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Europe, Africa, North and South America and Asia. He<br />

came home from his last trip, absolutely exhausted. Immediately after,<br />

on the night of 1 June 1970, he passed away at the age of 82.<br />

Among his many works, of particular note are his translations of<br />

Stéphane M<strong>al</strong>larmé, Jean Rac<strong>in</strong>e and Sa<strong>in</strong>t-John Perse, 40 sonn<strong>et</strong>s <strong>by</strong><br />

Shakespeare and other sonn<strong>et</strong>s <strong>by</strong> Luis de Góngora, a large number of<br />

William Blake’s Visions, and some excellent versions of Ezra Pound,<br />

Sergei Esen<strong>in</strong> and Brazilian po<strong>et</strong>s, such as José Osw<strong>al</strong>d de Souza<br />

Andrade, Mário de Andrade and V<strong>in</strong>icius de Moraes. Out of his<br />

enormous corpus of literary criticism, the university lectures that he<br />

gave dur<strong>in</strong>g his stay <strong>in</strong> Brazil are especi<strong>al</strong>ly memorable, pr<strong>in</strong>cip<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

those centred on the founders of It<strong>al</strong>ian and European literature, Dante<br />

and P<strong>et</strong>rarch. No less important are his lectures on the centr<strong>al</strong>ity and<br />

<strong>in</strong>disputable merit of Leopardi. Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti, moreover, cont<strong>in</strong>ued to<br />

explore Leopardi’s work <strong>in</strong> depth dur<strong>in</strong>g his period at La Sapienza<br />

University (See Vita d’un uomo. Viaggi e lezioni, a cura di Paola<br />

Montefoschi, Milano, Mondadori, 2000).<br />

Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s most important collections <strong>in</strong>clude L’Allegria (The Joy,<br />

1919), A Sense of Time (Il Sentimento del Tempo, 1933), Il Dolore<br />

(Affliction, 1947), La Terra Promessa (The Promised Land, 1950) and<br />

Il Taccu<strong>in</strong>o del Vecchio (The Old Man’s Notebook, 1960). These are<br />

the fundament<strong>al</strong> components of his compl<strong>et</strong>e works collected under<br />

18 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

the mov<strong>in</strong>g epith<strong>et</strong>, Vita d’un uomo (The Life of a Man). The word<br />

‘man’ needs to be read <strong>in</strong> the particular sense that Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti attributes<br />

to it, namely what a human be<strong>in</strong>g has been, <strong>in</strong> an endless series of<br />

moments, words, events, me<strong>et</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, read<strong>in</strong>gs, landscapes, rem<strong>in</strong>iscences<br />

and epiphanies.<br />

After the <strong>in</strong>novative babel-like language of The Joy, which attempts<br />

to start from an unheard-of word that ‘makes the world’ <strong>in</strong> the wake<br />

of the tot<strong>al</strong> destruction of the war, those same words come back to be<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> tradition<strong>al</strong> It<strong>al</strong>ian m<strong>et</strong>re, creat<strong>in</strong>g a language<br />

that is paradoxic<strong>al</strong>ly more obscure, capable of captur<strong>in</strong>g and express<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the baroque sense of <strong>et</strong>ern<strong>al</strong> time <strong>in</strong> Rome, the mytho-po<strong>et</strong>ic city<br />

centr<strong>al</strong> to Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s works (A Sense of Time). Rome was to be<br />

occupied and destroyed for a second time dur<strong>in</strong>g the Second World<br />

War. And it is here that Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti r<strong>et</strong>urns, follow<strong>in</strong>g his stay <strong>in</strong> Brazil,<br />

accompanied <strong>by</strong> two terrible losses: the pass<strong>in</strong>g of his son Antoni<strong>et</strong>to<br />

and of his brother Costant<strong>in</strong>o (Affliction). Rome <strong>al</strong>so <strong>in</strong>spired his<br />

Canzone and Chorus dedicated to the journey of Aeneas, founder of<br />

the Etern<strong>al</strong> City, and to the tragic figures of Dido – whose estrangement<br />

from Aeneas is <strong>in</strong>terpr<strong>et</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> a very Ungar<strong>et</strong>tian way as the end of<br />

youth – and P<strong>al</strong><strong>in</strong>urus, whose death was to <strong>al</strong>legoric<strong>al</strong>ly represent the<br />

impossibility for the po<strong>et</strong> of reach<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>nocent, primordi<strong>al</strong> land<br />

(The Promised Land).<br />

Rome seems to resist time and its pass<strong>in</strong>g, while the po<strong>et</strong> meditates<br />

on old age, the mean<strong>in</strong>g of death and on the void surround<strong>in</strong>g him.<br />

<strong>Like</strong> a modern Aeneas, the po<strong>et</strong> is <strong>al</strong>ways on the move, at one moment<br />

<strong>in</strong> the desolate Necropolis of Sakkarah <strong>in</strong> Egypt, at another, travell<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on a plane b<strong>et</strong>ween Hong Kong and Beirut, <strong>in</strong> search of a promised<br />

land or a buried harbour, where he might hear a word that, even if<br />

only <strong>in</strong> appearance and <strong>in</strong> the imag<strong>in</strong>ation, might ch<strong>al</strong>lenge mysteriously<br />

the <strong>in</strong>evitable pass<strong>in</strong>g of life:<br />

Mentre arrivo vic<strong>in</strong>o <strong>al</strong> gran silenzio,<br />

Segno sarà che niuna cosa muore<br />

Se ne ritorna sempre l’apparenza?<br />

(Da ‘Ultimi cori per la Terra promessa’ <strong>in</strong> Il Taccu<strong>in</strong>o del Vecchio)<br />

a note on ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s life and po<strong>et</strong>ry 19

As I approach the great silence,<br />

Will it be a sign that no th<strong>in</strong>g dies<br />

If its appearance keeps com<strong>in</strong>g back?<br />

(From ‘Last Choruses for the Promised Land’ <strong>in</strong> The Old Man’s<br />

Notebook, translated <strong>by</strong> A. Frisardi).<br />

The word is the re<strong>al</strong> miracle, as evidenced <strong>by</strong> the 21 poems from<br />

Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s first work, The Joy, which are presented <strong>in</strong> this anthology.<br />

Fac<strong>in</strong>g a world of appearance and rapidly pass<strong>in</strong>g moments, po<strong>et</strong>ry is<br />

<strong>al</strong>ways at war with time and stands <strong>in</strong> opposition to the perishable<br />

nature of th<strong>in</strong>gs, to paraphrase l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>by</strong> Shakespeare which Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

translated <strong>in</strong>to It<strong>al</strong>ian: ‘and <strong>al</strong>l <strong>in</strong> war with Time for love of you, / As<br />

he takes from you, I engraft you new’ (‘Sonn<strong>et</strong> xv’ <strong>by</strong> Shakespeare).<br />

The po<strong>et</strong>ry of Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti b<strong>in</strong>ds ‘the days that are the past / and the<br />

others to come /(…) <strong>in</strong> the present’, to build a time that seems to have<br />

no re<strong>al</strong>ity but the memory of it, because it is an <strong>in</strong>tuition of a moment<br />

b<strong>et</strong>ween two noth<strong>in</strong>gs, ‘b<strong>et</strong>ween the flower that is gathered and the one<br />

that is given’ (‘Etern<strong>al</strong>’), an <strong>in</strong>tuition that comes from an ‘endless<br />

secrecy’ (‘The Buried Harbour’) or from the ‘delirious ferment’ (‘Leav<strong>et</strong>ak<strong>in</strong>g’),<br />

much like P<strong>et</strong>rarch’s ‘tremar di meraviglia’ (‘trembl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

amazement’).<br />

It is a sort of m<strong>et</strong>aphysic<strong>al</strong> meditation on the <strong>in</strong>stant, triggered <strong>by</strong> a<br />

nost<strong>al</strong>gia for promised but absent words, <strong>by</strong> a repeated anamnesis<br />

com<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>termittently through sudden flashes of recollection. It is a<br />

rem<strong>in</strong>iscence <strong>in</strong> which the po<strong>et</strong> seems condemned or possessed <strong>by</strong> the<br />

demon of artistic creativity, or <strong>by</strong> constant visions from unheard<br />

‘fancies’ as Edgar Allan Poe would say. In ‘Silent’, one of Poe’s very<br />

short and emblematic texts (of which a draft translation <strong>by</strong> Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

dat<strong>in</strong>g back to 1914 has only recently been discovered), the writer<br />

seems to be a medium, an impatient <strong>in</strong>terpr<strong>et</strong>er of whispered words<br />

that are capable of arous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>al</strong>most primordi<strong>al</strong> wonders and epiphanic<br />

silences. And the poems of Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti, such as ‘Ennui’, ‘Levant’ and<br />

‘Perhaps a River Rises’ are noth<strong>in</strong>g more than the manifestation of<br />

these pure po<strong>et</strong>ic moments: the lonel<strong>in</strong>ess glimpsed <strong>in</strong> the nodd<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

the heads of cabbies sleep<strong>in</strong>g on their carriages (‘Ennui’); the distant<br />

shout<strong>in</strong>g and danc<strong>in</strong>g of Syrian emigrants on a ship travel<strong>in</strong>g to Paris<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>ed to the remembrance of an ancient practice of buri<strong>al</strong> from the<br />

20 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

homeland just left (‘Levant’); the Homeric, <strong>al</strong>beit brief, ‘Perhaps a<br />

River Rises’ that seems to echo the Sirens’ song from the Odyssey.<br />

The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g poems are <strong>al</strong>l variations on the theme of war and <strong>al</strong>l<br />

have location and date of writ<strong>in</strong>g appended to the title. Most were<br />

written <strong>in</strong> 1916 on the front l<strong>in</strong>e runn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>al</strong>ong the Karst, a rocky<br />

plateau which extends from western Slovenia, through the north-east<br />

of It<strong>al</strong>y, to the far north-west of Croatia. These poems reflect Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s<br />

hellish journey start<strong>in</strong>g from Locvizza, today Lokvica <strong>in</strong> Slovenia, and<br />

then mov<strong>in</strong>g back to It<strong>al</strong>ian soil <strong>in</strong> Dev<strong>et</strong>achi, a sm<strong>al</strong>l village of San<br />

Mart<strong>in</strong>o del Carso, then a post<strong>in</strong>g to the sm<strong>al</strong>l town of Mariano. From<br />

there the po<strong>et</strong> moves up to the bloody battlefields around St. Michele<br />

Mount, on to the sm<strong>al</strong>l village Cotici, and <strong>al</strong>ong paths lead<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

heights of the V<strong>al</strong>leys of the Solitary Tree and of Peak Four, up to the<br />

furthest po<strong>in</strong>t, Santa Maria la Longa, a rest camp that sees the writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of the famous ‘Morn<strong>in</strong>g’ (1917). Only one poem was composed far<br />

from the battlefields, <strong>in</strong> Naples <strong>in</strong> 1916, dur<strong>in</strong>g military leave. Our<br />

anthology closes with a poem dated July 1918, written <strong>in</strong> the area of<br />

Courton Woods, a region to the east of Paris. Here the conflict was<br />

atrocious, as testified <strong>by</strong> another It<strong>al</strong>ian writer, Curzio M<strong>al</strong>aparte, who<br />

described the violence as unprecedented, where the soldiers compl<strong>et</strong>ely<br />

exposed to enemy fire died <strong>in</strong> their thousands, and from where<br />

Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti, with two seven-syllable verses divided <strong>in</strong>to four l<strong>in</strong>es without<br />

punctuation and one lapidary word, ‘Soldiers’, as the title of the<br />

poem, testifies to the absurdity of the human condition and its <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic<br />

f<strong>in</strong>itude:<br />

They are like<br />

the leaves<br />

of trees<br />

<strong>in</strong> autumn<br />

This is the geography of Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s po<strong>et</strong>ry which comes to be made<br />

up of a language more and more grounded <strong>in</strong> brief episodes which<br />

primarily reflect the war, but which <strong>al</strong>so <strong>al</strong>low space for earlier<br />

memories l<strong>in</strong>ked to the long stay <strong>in</strong> Paris, such as the tragic death of a<br />

friend who commits suicide (‘In Memoriam’) and a nocturn<strong>al</strong> encounter<br />

with a woman, lonely and silent, on a bridge over the Se<strong>in</strong>e (‘Nost<strong>al</strong>gia’).<br />

The words are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly emancipated from their surface mean<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

a note on ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s life and po<strong>et</strong>ry 21

their use rely<strong>in</strong>g more on the evocative power of the sounds, reduced<br />

simply to phoné, a pure issue of voice like the ‘f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> vowel’ <strong>in</strong> the first<br />

l<strong>in</strong>e of the last poem written <strong>by</strong> another giant of po<strong>et</strong>ry, Seamus Heaney.<br />

In Heaney’s ‘Banks of a Can<strong>al</strong>’, pure sound seems to have the power<br />

of ‘tow<strong>in</strong>g silence’, of silenc<strong>in</strong>g the entire world:<br />

Say ‘can<strong>al</strong>’ and there’s that f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> vowel<br />

Tow<strong>in</strong>g silence with it, slow<strong>in</strong>g time<br />

To a w<strong>al</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g pace, a path, a whitewashed gleam<br />

Of dwell<strong>in</strong>gs at the skyl<strong>in</strong>e. World stands still.<br />

The ‘world stands still’ while the demiurge po<strong>et</strong> is grappl<strong>in</strong>g with the<br />

nam<strong>in</strong>g of the world and the empty<strong>in</strong>g of semantic language, with the<br />

death and rebirth of the word. We are witness<strong>in</strong>g a dramatisation of<br />

an expectation of mean<strong>in</strong>g. R<strong>et</strong>urn<strong>in</strong>g to Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti, this po<strong>et</strong>ic<br />

v<strong>al</strong>idation and obliteration of the world is the essence of his po<strong>et</strong>ry,<br />

and shows that his work goes beyond the life of one man because it<br />

belongs to <strong>al</strong>l time:<br />

The po<strong>et</strong> goes there<br />

and then r<strong>et</strong>urns to the light with his songs<br />

and scatters them there<br />

As a conclusion and as a tribute to Scottish po<strong>et</strong>ry, these l<strong>in</strong>es from<br />

‘The Buried Harbour’ can be s<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>ongside some l<strong>in</strong>es of another soldier<br />

po<strong>et</strong>, from another war – the Second World War: Hamish Henderson.<br />

He was one of the fathers of Scotland’s 20th-century folk renaissance,<br />

and <strong>al</strong>so the first translator of Gramsci <strong>in</strong>to English. One of his poems<br />

‘Under the earth I go’ seems to have been <strong>in</strong>spired <strong>by</strong> and blends with<br />

the above verse <strong>by</strong> Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti:<br />

Maker, ye maun s<strong>in</strong>g them…<br />

Tomorrow, songs<br />

Will flow free aga<strong>in</strong>, and new voices<br />

Be borne on the carry<strong>in</strong>g stream.<br />

22 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

Eterno<br />

giuseppe ungar<strong>et</strong>ti<br />

Tra un fiore colto e l’<strong>al</strong>tro donato<br />

l’<strong>in</strong>esprimibile nulla<br />

<strong>et</strong>erno 35

Etern<strong>al</strong><br />

giuseppe ungar<strong>et</strong>ti Translated <strong>by</strong> Heather Scott<br />

B<strong>et</strong>ween the flower that is gathered and the one that is given<br />

the <strong>in</strong>expressible noth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

36 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

August Sander · Studien – Der Mensch (Grandmother and Child) · c. 1919

By remember<strong>in</strong>g I fold myself <strong>in</strong>to you<br />

j.l. williams<br />

No silence no present moment exists<br />

<strong>in</strong> which you do not exist<br />

The men I adore holed up dream<strong>in</strong>g<br />

eagles whose nests are bent <strong>in</strong>to mist<br />

I was <strong>al</strong>ways wait<strong>in</strong>g<br />

for you my brother<br />

lost on the road under the tree<br />

whose pa<strong>in</strong> is gold golden<br />

My father who I do not know<br />

My country who I do not know<br />

You are here f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>ly<br />

<strong>in</strong> the mouth of the bird<br />

whose tongue is one I recognise<br />

whose tongue is the crab liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the mouth<br />

replac<strong>in</strong>g the tongue<br />

say<strong>in</strong>g <strong>al</strong>l your food is m<strong>in</strong>e f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>ly<br />

my love<br />

Poor bird without trees<br />

whose home was given to the war<br />

who remembers the two-penny hangovers of men<br />

My only my bird whose w<strong>in</strong>g is pull<strong>in</strong>g<br />

via shoulder muscle tight with<strong>in</strong> the belly<br />

up up past the present<br />

past the observation of burn<strong>in</strong>g light<br />

<strong>in</strong> clouds over sea to the boys on the side<br />

their privilege their impatient deaths their unwritten down<br />

Their wooden rifles carried <strong>in</strong>to war<br />

Their horse-drawn carriage<br />

Their qui<strong>et</strong> mule<br />

Their mother’s dress<br />

Their warm hay b<strong>al</strong>e<br />

Their accumulation of birdsong<br />

38 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

Commentary<br />

j.l. williams<br />

I have heard it said that Ungar<strong>et</strong>ti’s entire po<strong>et</strong>ics is summed up <strong>in</strong> the<br />

two l<strong>in</strong>es of his poem Etern<strong>al</strong>, whose music is even more evocative <strong>in</strong><br />

the It<strong>al</strong>ian:<br />

Tra un fiore colto e l’<strong>al</strong>tro donato<br />

l’<strong>in</strong>esprimibile nulla<br />

It is untranslatable <strong>in</strong> a way, as the movement <strong>in</strong>to English <strong>in</strong> various<br />

translations conveys mean<strong>in</strong>g but struggles, because of the <strong>in</strong>herent<br />

difference <strong>in</strong> the sound of the English words and the It<strong>al</strong>ian words, to<br />

convey the beauty and import of those r<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g o’s: colto e l’<strong>al</strong>tro<br />

donato.<br />

B<strong>et</strong>ween the gather<strong>in</strong>g or cultivation of the flowers and the giv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of the flowers, b<strong>et</strong>ween the grow<strong>in</strong>g and the pass<strong>in</strong>g on, b<strong>et</strong>ween birth<br />

and death, b<strong>et</strong>ween one language and another, b<strong>et</strong>ween peace and war,<br />

b<strong>et</strong>ween the creation of the poem and the shar<strong>in</strong>g of the poem is the<br />

gulf of the <strong>in</strong>expressible. Y<strong>et</strong> that is what words, especi<strong>al</strong>ly the blooms<br />

of words <strong>in</strong> poems, do – through image, m<strong>et</strong>aphor, sound and silence,<br />

they represent the strange and <strong>in</strong>explicable occurrence that is existence.<br />

<strong>et</strong>erno 39

j.l. williams (b. 1977)<br />

Jennifer’s first collection Condition of Fire (Shearsman, 2011) was<br />

<strong>in</strong>spired <strong>by</strong> Ovid’s M<strong>et</strong>amorphoses and a journey to the Aeolian<br />

Islands. Her second collection Locust and Marl<strong>in</strong> (Shearsman, 2014)<br />

explores the idea of home and where we come from and was nom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

for the 2014 S<strong>al</strong>tire Soci<strong>et</strong>y Po<strong>et</strong>ry Book of the Year Award. She plays<br />

<strong>in</strong> the band Opul and is Programme Manager at the Scottish Po<strong>et</strong>ry<br />

Library. More <strong>in</strong>fo: www.jlwilliamspo<strong>et</strong>ry.co.uk<br />

august sander (1876–1964)<br />

August Sander is one of the most <strong>in</strong>fluenti<strong>al</strong> documentary photographers<br />

of the 20th century. He photographed <strong>in</strong>dividu<strong>al</strong>s or groups of people<br />

<strong>in</strong> Germany, adopt<strong>in</strong>g a scientific or anthropologic<strong>al</strong> approach, as if<br />

construct<strong>in</strong>g a sociology of contemporary man. His figures are mostly<br />

depicted front<strong>al</strong>ly aga<strong>in</strong>st a neutr<strong>al</strong> background and with limited faci<strong>al</strong><br />

expression, produc<strong>in</strong>g re<strong>al</strong>ist effects.<br />

40 like leaves <strong>in</strong> autumn

Luath Press Limited<br />

committed to publish<strong>in</strong>g well written books worth read<strong>in</strong>g<br />

luath press takes its name from Robert Burns, whose little collie Luath (Gael.,<br />

swift or nimble) tripped up Jean Armour at a wedd<strong>in</strong>g and gave him the chance to<br />

speak to the woman who was to be his wife and the abid<strong>in</strong>g love of his life.<br />

Burns c<strong>al</strong>led one of ‘The Twa Dogs’ Luath after Cuchull<strong>in</strong>’s<br />

hunt<strong>in</strong>g dog <strong>in</strong> Ossian’s F<strong>in</strong>g<strong>al</strong>. Luath Press was established<br />

<strong>in</strong> 1981 <strong>in</strong> the heart of Burns country, and now resides<br />

a few steps up the road from Burns’ first lodg<strong>in</strong>gs on<br />

Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh’s Roy<strong>al</strong> Mile.<br />

Luath offers you dist<strong>in</strong>ctive writ<strong>in</strong>g with a h<strong>in</strong>t of<br />

unexpected pleasures.<br />

Most bookshops <strong>in</strong> the uk, the us, Canada, Austr<strong>al</strong>ia,<br />

New Ze<strong>al</strong>and and parts of Europe either carry our books<br />

<strong>in</strong> stock or can order them for you. To order direct from<br />

us, please send a £sterl<strong>in</strong>g cheque, post<strong>al</strong> order, <strong>in</strong>ternation<strong>al</strong><br />

money order or your credit card d<strong>et</strong>ails (number, address of<br />

cardholder and expiry date) to us at the address below. Please add<br />

post and pack<strong>in</strong>g as follows: uk – £1.00 per delivery address; overseas<br />

surface mail – £2.50 per delivery address; overseas airmail –<br />

£3.50 for the first book to each delivery address, plus £1.00 for each<br />

addition<strong>al</strong> book <strong>by</strong> airmail to the same address. If your order is a gift, we will happily<br />

enclose your card or message at no extra charge.<br />

Luath Press Limited<br />

543/2 Castlehill<br />

The Roy<strong>al</strong> Mile<br />

Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh EH1 2ND<br />

Scotland<br />

Telephone: 0131 225 4326 (24 hours)<br />

email: s<strong>al</strong>es@luath.co.uk<br />

Website: www.luath.co.uk<br />

ILLUSTRATION: IAN KELLAS