Angelus News | January 26, 2024 | Vol. 9 No. 2

On the cover: High school student Atticus Maldonado smiles between classes at St. Pius X-St. Matthias Academy in Downey. On Page 10, Angelus contributor Steve Lowery has the incredible story of how Maldonado’s school community rallied behind him in prayer — and why his unlikely recovery from a rare cancer may not even be the story’s biggest miracle.

On the cover: High school student Atticus Maldonado smiles between classes at St. Pius X-St. Matthias Academy in Downey. On Page 10, Angelus contributor Steve Lowery has the incredible story of how Maldonado’s school community rallied behind him in prayer — and why his unlikely recovery from a rare cancer may not even be the story’s biggest miracle.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Bella is cared for by Godwin’s kindly<br />

assistant Max (Ramy Youssef), who<br />

with Godwin’s permission, bordering<br />

on insistence, proposes marriage. But<br />

even childlike Bella recognizes it is<br />

“God’s” attempt to keep her at home<br />

away from a wider world which he<br />

fears and she longs for.<br />

(While allowing for curiosity, I think<br />

the film overestimates a child’s mind<br />

for new experience. Children are<br />

natural reactionaries; ask them to<br />

sample new food other than chicken<br />

fingers and they’ll respond with all the<br />

liberality of a Russian czar.)<br />

With his permission she instead<br />

runs off with Duncan Wedderburn<br />

(Mark Ruffalo). A caddish lawyer (at<br />

the risk of sounding redundant) he<br />

takes advantage of Bella’s naiveté and<br />

whisks her off on a lover’s holiday.<br />

Bella’s accelerated mental progression<br />

now finds her in the thick of adolescence,<br />

so if Duncan uses her, she is<br />

an enthusiastic accomplice.<br />

But we are back again to the great<br />

divide of provocation and interest. In<br />

the longest stretch of the film we are<br />

shown in great detail the particulars<br />

of Bella’s sexual awakening, sequences<br />

that most readers of this magazine<br />

would find lewd and indecent.<br />

But throughout all this extracurricular<br />

activity my eyes averted from the<br />

screen not from prudishness but boredom.<br />

Sexuality is indeed part of growing<br />

up, but it isn’t the skeleton key of<br />

adulthood. Lanthimos takes Bella into<br />

the wider world, but his focus on this<br />

one aspect of her person shrinks it.<br />

She wants to see the pyramids, but she<br />

must settle for the ceiling.<br />

It even puts him at odds with his own<br />

thesis. Bella is an Edenic creature, her<br />

innocence putting her at odds with<br />

a fallen society. It would certainly<br />

explain her comfort with nudity. She<br />

eats sloppily, dances merrily, and lacks<br />

the patience for innuendo in polite<br />

conversation. Most importantly, she<br />

doesn’t fathom the absurd strictures<br />

her society places on women, and<br />

like most children ignores what she<br />

doesn’t understand.<br />

But Lanthimos groups her freewheeling<br />

sexual liberation in with<br />

her burgeoning feminism, a pairing<br />

that fell out of fashion somewhere<br />

between Rocky II and Rocky IV. It’s<br />

a retrograde feminism, not respecting<br />

women in all their baffling facets but<br />

to the extent to which they please the<br />

drooling patriarchy.<br />

In fairness, the film recognizes the<br />

abuses. For all his talk of spurning<br />

convention, Duncan grows more<br />

possessive the wider Bella’s perspective<br />

expands. He says he wants to show<br />

her the world, but we realize along<br />

with her that a narcissist thinks the<br />

world ends at his sightline. He tricks<br />

her onto a cruise ship where she can’t<br />

leave him, but that is only prolonging<br />

the inevitable. Rid of his dead weight,<br />

she later takes up a brief residency<br />

in a brothel, a rose-colored vignette<br />

on sex work where her sex positivity<br />

goes over like gangbusters. After her<br />

adventures she finally returns and is<br />

reconciled to her fiancé and “God,”<br />

her wild oats sufficiently sown.<br />

Perhaps as a Catholic I should<br />

endorse such a tidy resolution, but<br />

I have never found myself more<br />

offended at a film coming full circle.<br />

It meant all its provocations were for<br />

nothing, even its postures of defiance<br />

ultimately subjugated to conventional<br />

mores. What we watched for the last<br />

two hours was not a young woman<br />

bucking the absurdities of our society,<br />

but a sorority girl on a gap year<br />

abroad.<br />

In other words, “Poor Things” is<br />

about controlled rebellion, the cinematic<br />

equivalent of Woodstock hippies<br />

who went on to work for weapon<br />

manufacturers. I have more genuine<br />

respect for sticking to a principle, even<br />

in violation of my own, than dabbling<br />

in revolution only to embrace the cog.<br />

God can forgive any sins, but I can’t<br />

forgive you for wasting my time.<br />

Editor’s note: “Poor Things” is rated R<br />

for strong and pervasive sexual content,<br />

graphic nudity, disturbing material,<br />

gore, and language.<br />

Joseph Joyce is a screenwriter and freelance<br />

critic based in Sherman Oaks.<br />

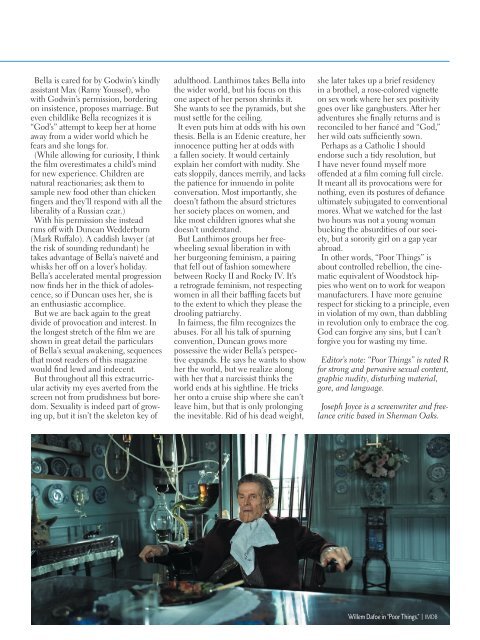

Willem Dafoe in “Poor Things.” | IMDB