Iolkos and Pagasai: Two New Thessalian Mints* - Royal Numismatic ...

Iolkos and Pagasai: Two New Thessalian Mints* - Royal Numismatic ...

Iolkos and Pagasai: Two New Thessalian Mints* - Royal Numismatic ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong>:<br />

<strong>Two</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Thessalian</strong> Mints *<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

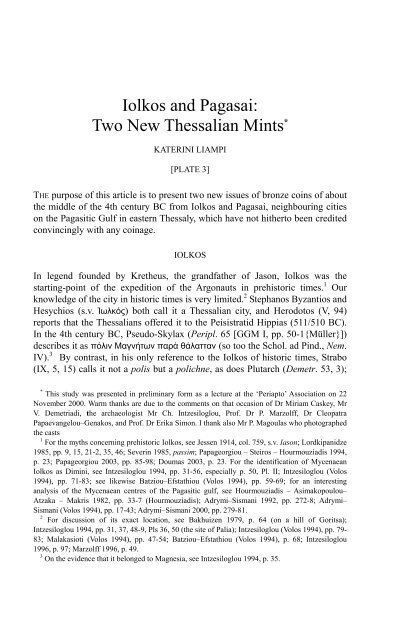

[PLATE 3]<br />

THE purpose of this article is to present two new issues of bronze coins of about<br />

the middle of the 4th century BC from <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong>, neighbouring cities<br />

on the Pagasitic Gulf in eastern Thessaly, which have not hitherto been credited<br />

convincingly with any coinage.<br />

IOLKOS<br />

In legend founded by Kretheus, the gr<strong>and</strong>father of Jason, <strong>Iolkos</strong> was the<br />

starting-point of the expedition of the Argonauts in prehistoric times. 1 Our<br />

knowledge of the city in historic times is very limited. 2 Stephanos Byzantios <strong>and</strong><br />

Hesychios (s.v. ������) both call it a <strong>Thessalian</strong> city, <strong>and</strong> Herodotos (V, 94)<br />

reports that the <strong>Thessalian</strong>s offered it to the Peisistratid Hippias (511/510 BC).<br />

In the 4th century BC, Pseudo-Skylax (Peripl. 65 [GGM I, pp. 50-1{Müller}])<br />

describes it as������������������������������(so too the Schol. ad Pind., Nem.<br />

IV). 3 By contrast, in his only reference to the <strong>Iolkos</strong> of historic times, Strabo<br />

(IX, 5, 15) calls it not a polis but a polichne, as does Plutarch (Demetr. 53, 3);<br />

* This study was presented in preliminary form as a lecture at the ‘Periapto’ Association on 22<br />

November 2000. Warm thanks are due to the comments on that occasion of Dr Miriam Caskey, Mr<br />

V. Demetriadi, the archaeologist Mr Ch. Intzesiloglou, Prof. Dr P. Marzolff, Dr Cleopatra<br />

Papaevangelou–Genakos, <strong>and</strong> Prof. Dr Erika Simon. I thank also Mr P. Magoulas who photographed<br />

the casts<br />

1 For the myths concerning prehistoric <strong>Iolkos</strong>, see Jessen 1914, col. 759, s.v. Iason; Lordkipanidze<br />

1985, pp. 9, 15, 21-2, 35, 46; Severin 1985, passim; Papageorgiou – Steiros – Hourmouziadis 1994,<br />

p. 23; Papageorgiou 2003, pp. 85-98; Doumas 2003, p. 23. For the identification of Mycenaean<br />

<strong>Iolkos</strong> as Dimini, see Intzesiloglou 1994, pp. 31-56, especially p. 50, Pl. II; Intzesiloglou (Volos<br />

1994), pp. 71-83; see likewise Batziou–Efstathiou (Volos 1994), pp. 59-69; for an interesting<br />

analysis of the Mycenaean centres of the Pagasitic gulf, see Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–<br />

Atzaka – Makris 1982, pp. 33-7 (Hourmouziadis); Adrymi–Sismani 1992, pp. 272-8; Adrymi–<br />

Sismani (Volos 1994), pp. 17-43; Adrymi–Sismani 2000, pp. 279-81.<br />

2 For discussion of its exact location, see Bakhuizen 1979, p. 64 (on a hill of Goritsa);<br />

Intzesiloglou 1994, pp. 31, 37, 48-9, Pls 36, 50 (the site of Palia); Intzesiloglou (Volos 1994), pp. 79-<br />

83; Malakasioti (Volos 1994), pp. 47-54; Batziou–Efstathiou (Volos 1994), p. 68; Intzesiloglou<br />

1996, p. 97; Marzolff 1996, p. 49.<br />

3 On the evidence that it belonged to Magnesia, see Intzesiloglou 1994, p. 35.

24<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

but Strabo is here describing the group of villages <strong>and</strong> small cities which were<br />

synoecized to form the new city of Demetrias, <strong>and</strong> probably uses the word<br />

polichnai loosely to cover them all.<br />

The Magnetes 4 were subject to the tyrants of Pherai, except for a short period<br />

after 363 BC when they came under the Boiotians. We shall see that Philip II<br />

later placed the region under his control. Around 294/293 BC, Demetrios<br />

Poliorketes founded Demetrias, 5 which became the royal Macedonian<br />

residence 6 <strong>and</strong> a naval station (Strabo IX, 5, 15). The inhabitants of the cities or<br />

settlements which had joined the synoecism formed demes within the new city.<br />

Thus the demos of the Iolkians occurs in a decree of the 3rd century BC. 7 A<br />

stone with two inscriptions from the period of Antigonos Gonatas appears to<br />

show that the heroes of the cities that joined in the synoecism of Demetrias were<br />

worshipped there. 8 Thereafter, the sources make no further reference to <strong>Iolkos</strong>,<br />

apart from an occasion in 169 BC when Eumenes II <strong>and</strong> the Romans camped<br />

there in order to attack Demetrias (Livy XLIV, 12, 8 <strong>and</strong> 13, 5).<br />

Until recently coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> were unknown, but a few years ago I was<br />

fortunate enough to see five bronze coins in a private collection in Germany<br />

with the legend ���������as follows.<br />

Obv. Head of Iolkian Artemis r. with hair in a low krobylos <strong>and</strong> a quiver at her<br />

neck. She wears pendent earrings <strong>and</strong> a necklace. Border of dots.<br />

Rev. �������. Prow of Argo l. with apotropaic eye <strong>and</strong> schematised waves<br />

below, like pellets. On stem-post, an oak branch (?). AE, 12 mm. All coins are<br />

illustrated on Pl. 3.<br />

Die-Axis (h) Wt. (g)<br />

1. O1/R1 a. 09 1.53 Private collection (found in Thessaly).<br />

On the obverse there is an oblique incision in the hair.<br />

b. 12 2.26 Private collection (found in Thessaly).<br />

c. 12 2.19 Private collection.<br />

On the obverse of 1b <strong>and</strong> 1c there is a small die-break in front of the forehead,<br />

<strong>and</strong> on 1c a small diagonal break in front of the mouth.<br />

2. O2/R1 a. 06 1.68 Private collection (found in Thessaly).<br />

b. 01 2.53 Private collection (found near Larisa).<br />

4 For the history of Magnesia, see Stählin 1928, cols 464-7, s.v. Magnesia (1).<br />

5 Marzolff 1980, pp. 24-35 (with sources <strong>and</strong> bibliography); Cohen 1995, pp. 111-4.<br />

6 For the development <strong>and</strong> building phases of the new city, see Marzolff 1992, pp. 337-48;<br />

Marzolff 1994, pp. 57-70; Marzolff 1996, p. 51; Marzolff (Mainz am Rhein 1996), pp. 148-63. See<br />

also Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–Atzaka – Makris 1982, pp. 40-2 (Hourmouziadis).<br />

7 Intzesiloglou 1996, pp. 97-100 (graph 1), with discussion of the administrative organisation of<br />

Demetrias under Macedonian rule. <strong>Two</strong> citizens of Demetrias are recorded with the demotic Iolkios:�<br />

������������������(IG IX 2, 1109, l. 6), <strong>and</strong>����������������������������(Helly 1971, pp. 555-9).<br />

8 Leschhorn 1984, pp. 264-7, with references.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 25<br />

A die-flaw resembling a small globule on the only known reverse die occurs in<br />

the upper left field of all the coins.<br />

The two obverse dies appear to be more or less contemporary since they are<br />

clearly by the same h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the reverse die with which they are coupled shows<br />

the same degree of wear with both. The flans of all the coins are very thick,<br />

resembling those of other <strong>Thessalian</strong> coins dated to the first half <strong>and</strong> middle of<br />

the 4th century BC. The die-axes are irregular <strong>and</strong> some of the coins are poorly<br />

centred. The diameter of all coins is consistent <strong>and</strong> does not exceed 12 mm.<br />

With an average weight of 2.03g our coins seem to be chalkoi, denomination C<br />

in the analysis of Papaevangelou-Genakos <strong>and</strong> the smallest bronze minted in<br />

Thessaly. 9<br />

The letters of the legend are not particularly revealing for dating purposes, but<br />

are consistent with the Ionian alphabet of the 4th century BC, having, for<br />

example, a fairly large omega. The ethnic������������������� is known from the<br />

written sources (Stephanos Byzantios, s.v.��������� <strong>and</strong> also from inscriptions. 10<br />

The head of Artemis has a bulbous eye with thick eyelashes set at an angle <strong>and</strong><br />

a markedly arched eyebrow, a low forehead, an almost triangular jutting chin,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a flat cheek. As we shall see, it bears some similarity to the head of Apollo<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong>os on the coins of <strong>Pagasai</strong>. For dating purposes the most important<br />

feature is the hair, which is in the so-called melon style. This style appeared<br />

shortly before the middle of the 4th century BC, reached its peak of popularity<br />

during the 3rd century BC, but continued in use sporadically in sculpture,<br />

figurines, <strong>and</strong> coins. The style appears on the head of Ennodia on coins of<br />

Pherai issued under the tyrant Alex<strong>and</strong>er (369-358 BC) <strong>and</strong> in the name of the<br />

city in the second quarter of the 4th century BC, 11 <strong>and</strong> on the head of Artemis on<br />

the coins of Ekkarra. 12 In addition to these <strong>Thessalian</strong> mints, a similar style<br />

appears on the head of Artemis on coins of Orthagoreia 13 <strong>and</strong> of Philip II, both<br />

dated by Le Rider to around 342/341-329/328 BC, 14 <strong>and</strong> on the head of Artemis<br />

on the silver coinage of the Scythian king Ateas 15 during the second half of the<br />

4th century BC under the influence of the coins of Philip II. There are many<br />

parallels in sculpture <strong>and</strong> figurines. 16 Note in particular a grave relief from Agria<br />

9<br />

Papaevangelou–Genakos 2004, p. 47.<br />

10<br />

IG IX 2, 1109, l. 6.<br />

11<br />

Wartenberg 1994, pp. 151-6, Pl. 159, no. 15 (Alex<strong>and</strong>er); no. 8 (Pherae).<br />

12 Liampi 1998, pp. 417-39.<br />

13 Gaebler 1935, pp. 92-3, nos 1-3, Pl. 18, nos 21-3.<br />

14 Le Rider 1977, pp. 395-6, Pl. 43, nos 504-11 (Amphipolis II, B).<br />

15 SNG BM (Black Sea) 200; for a better preserved example, see <strong>Numismatic</strong>a Genevensis 1 (A.<br />

Baron, Geneva, 27/11/2000), no. 76.<br />

16 For example a Bear from Brauron (Themelis (-), p. 70, fig. 16 b), <strong>and</strong> a terracotta female<br />

figurine found in a grave near Nea Anchialos in Thessaly (Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–Atzaka<br />

– Makris 1982, p. 65, fig. 35 (Hourmouziadis)).

26<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

in the Iolkitis of the last quarter of the 4th century BC, on which the deceased<br />

young woman is shown with melon hair style <strong>and</strong> flat krobylos. 17<br />

The head of Artemis on the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> thus suits a 4th century BC date. In<br />

hairstyle <strong>and</strong> modelling it bears little relation to the head of Artemis on the<br />

obverse of the silver coins of Demetrias with prow reverse issued, according to<br />

Furtwängler, around 287-285/284 BC, several years after the foundation, 18 or to<br />

the head on the contemporary bronzes of Demetrias, 19 <strong>and</strong> still less to the head<br />

on the coins of Demetrias at the beginning of the 2nd century BC. 20<br />

The Artemis depicted on the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> is undoubtedly the important local<br />

divinity Artemis Iolkia. 21 This is the only known representation of the goddess<br />

from <strong>Iolkos</strong> itself before it joined in the synoecism which formed Demetrias.<br />

Papachatzis believes that she is a Mycenaean divinity probably worshipped as a<br />

goddess of childbirth rather than of the hunt, 22 but the quiver at her neck on the<br />

coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong>, as we shall see, on the Imperial coins of the Magnetes<br />

shows that she is the huntress. The modern church of the Hagioi Theodoroi at<br />

Palia (<strong>Iolkos</strong>) in Volos may occupy the site of her temple. 23 Inscriptions from<br />

Demetrias mention the goddess, her priestess 24 <strong>and</strong> her peripteral temple, whose<br />

foundations were discovered in the sacred agora of the Macedonian city, south<br />

of the palace. 25 The goddess is mentioned in Hellenistic inscriptions as a<br />

member of a triad with Apollo Koropaios <strong>and</strong> Zeus Akraios, by whose names<br />

the Magnetes swore their oaths. 26<br />

Artemis Iolkia <strong>and</strong> her cult statue were discussed by Franke <strong>and</strong> Schultz in<br />

two important works. Franke published a bronze coin struck by the Magnetes<br />

under Severus Alex<strong>and</strong>er (AD 222-235), with on the reverse an enthroned<br />

female figure with a sceptre (?) <strong>and</strong> phiale or pomegranate (?), identified as<br />

Artemis by the legend ������. He argued that the depiction was a copy of a<br />

17 Biesantz 1965, pp. 12, 131, no. K16, Pl. 21.<br />

18 Boston 872; McClean Collection 4567; Furtwängler 1990, p. 307, Emission A, Pl. 3.<br />

19 Rogers 1932, p. 73, no. 206, fig. 87, differs stylistically from coins of Demetrias recovered in<br />

excavations at Demetrias (see Furtwängler 1990, pp. 124-8, 317, Pls 25, 35-6), <strong>and</strong> I have strong<br />

reservations about its attribution.<br />

20 BMC (Thessaly to Aetolia), p. 18, no. 1, Pl. 3, no. 1 (wrongly dated to the period after the<br />

founding of the city); Furtwängler 1990, pp. 308-10, Emission B, Pl. 4.<br />

21 Drexler 1890-4, col. 290, s.v. Iolkia; Adler 1916, col. 1850, s.v. Iolkia; Stählin 1916, cols 1853-<br />

4, s.v�����������������; Stählin – Meyer – Heidner 1934, p. 187.<br />

22 Papachatzis 1984, pp. 148-9.<br />

23 Stählin 1924, p. 65; Arvanitopoulos 1928, p. 105, fig. 112; Marzolff 1996, p. 49; the possibility<br />

is also mentioned by Hourmouziadis in Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–Atzaka – Makris 1982, p.<br />

98.<br />

24 IG IX 2, 1109, l. 55 (goddess); IG IX 2, 1122 (priestess).<br />

25 Marzolff 1976, pp. 47-58 (with earlier bibliography); Marzolff 1996, p. 56; Batziou–Efstathiou<br />

1996, p. 18. An inscription from Cletor, IG V 2, 367, col. IV, l. 45, refers to her sanctuary at<br />

Demetrias.<br />

26 IG IX 2, 1109, l. 54-5.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 27<br />

sculptural type, probably of the 4th/3rd century BC. 27 Schultz took the argument<br />

further, 28 using another coin of the Magnetes with a portrait of Julia Domna (AD<br />

211-217) on the obverse, <strong>and</strong> on the reverse an enthroned female figure. Rogers<br />

had read the reverse legend as ���������� ������ ���, 29 but Schultz<br />

corrected it to� ������� ������� <strong>and</strong> noted an enthroned female figure with a<br />

fuller version of the legend,� �������� ������� ��������, on coins of the<br />

Magnetes under Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161). This figure holds a flower (?) in<br />

one h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> an arrow in the other, <strong>and</strong> has a quiver at her shoulder. The minor<br />

differences in attributes do not undermine the hypothesis that a single statue lies<br />

behind these representations of Artemis Iolkia, as Schultz rightly notes. 30<br />

The warship prow on the reverse of the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> is rendered in<br />

considerable detail 31 <strong>and</strong> their good state of preservation allows us to discern the<br />

deck, the stem-post, the beak, the ram <strong>and</strong> the apotropaic eye. This prow differs<br />

from those depicted at other mints in the area, namely Thebes in Phthiotis 32<br />

(though a few dies show a similarity in the depiction of the stem-post 33 ), <strong>and</strong><br />

Demetrias (see nn. 18-20). The prow with slightly curving stem-post on several<br />

silver issues of the Magnetes in the 2nd century BC bears some resemblance,<br />

although there the waves on the keel are more skilfully drawn. 34 Nor does the<br />

prow on the bronze coins of Demetrios Poliorketes attributed to the northern<br />

region bear much resemblance. 35 The prow emblem, ���������, found on the<br />

seals of Demetrias is very different from the prow on the Iolkian coins (see<br />

below).<br />

Was the prow on the reverse of the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> simply a warship, or was it<br />

the Argo? The prow on the coins of Demetrias, both those issued a few years<br />

after the synoecism (287-285/284 BC; see nn. 18-19) <strong>and</strong> those struck around<br />

192/191 BC (see n. 20), has nothing to identify it as the Argo. Before 168 BC<br />

the silver <strong>and</strong> bronze coins issued by the Koinon of the Magnetes (see n. 34) had<br />

the same types as the coins of Demetrias, but with the legend ��������. After<br />

168/167 BC, when the Second Koinon of the Magnetes was established, its<br />

drachms depicted Artemis on the prow, 36 identified as Artemis ��������,<br />

27 Franke 1967, pp. 62-4, figs 1-3 (with sources <strong>and</strong> bibliography). See also the discussion in Kron<br />

– Furtwängler 1983, p. 168 (with n. 66) (Furtwängler).<br />

28 Schultz 1975, pp. 14-6, figs 1-6.<br />

29 Rogers 1932, pp. 118-9, no. 370, fig. 190.<br />

30 Schultz 1975, p. 16. See also Kahil – Icard 1984, p. 671, no. 657, s.v. Artemis.<br />

31 For the parts of the prow, see Svoronos 1914, pp. 81-152; Höckmann 1985, pp. 154-5; Morello<br />

1998, pp. 28-9, 38, 93-4.<br />

32 BMC (Thessaly to Aetolia), p. 50, no. 1, Pl. 11, no. 3; Rogers 1932, pp. 174-5, nos 550-1, figs<br />

306-8.<br />

33<br />

Winterthur 1723.<br />

34<br />

BMC (Thessaly to Aetolia), p. 34, no. 1, Pl. 7, no. 2; Furtwängler 1990, pp. 310-5, Emission C–<br />

F, Pls 5, 7-8.<br />

35<br />

<strong>New</strong>ell 1927, Pl. 17, nos 15, 19 (in the Hellespont region).<br />

36<br />

Furtwängler 1990, pp. 312-6, Emission D-G, Pls 7-8.

28<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

protectress of ships 37 (Apoll. Rhod., Argon. I, 570, in connection with the<br />

expedition of the Argonauts), rather than Iolkia. This prow seems to have no<br />

specific historical or political significance, <strong>and</strong> seems thus to be analogous to<br />

the Apollo-on-prow type of the coins of Antigonos Doson: the significance was<br />

purely cultic, for ships <strong>and</strong> fleets always had protecting divinities. 38 The reverse<br />

type of the bronzes of the Magnetes is again the prow, but without the figure of<br />

Artemis. Thus it appears that the prow on the coins of Demetrias <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Magnetes was not that of the Argo but simply a ship that symbolised the<br />

importance of the port of Demetrias. During Imperial times the Magnetes issued<br />

coins that clearly depict the Argo, for on these the ship’s name is written<br />

����. 39 The representation is considered 40 to be different from those on the<br />

Hellenistic coins of the Magnetes because the entire ship is depicted together<br />

with the oarsmen. The Argo is also depicted in Imperial times on the bronze<br />

coins of Sidon; these bear the legend ��������, 41 identifying the crew, the<br />

Argonauts.<br />

Similarly, during the Hellenistic period the clay sealings of Demetrias<br />

sometimes depict a prow, on which occasionally st<strong>and</strong>s a helmeted nude warrior<br />

holding a round shield <strong>and</strong> a spear or sword. 42 The latter has been identified as<br />

the oikistes-archegetes, Demetrios Poliorketes, founder of Demetrias, where he<br />

was buried <strong>and</strong> worshipped as a hero until the power of Macedon was broken. 43<br />

Furtwängler is doubtless correct in supposing that it is the public seal of<br />

Demetrias. 44 The new excavations of the north wing of the palace at Demetrias<br />

have brought to light the marble base of a dedication carved in the form of a<br />

prow. 45 Clearly this does not refer to the Argo, but symbolises the Macedonian<br />

fleet, which was based at Demetrias, if it is not a direct reference to Demetrios<br />

Poliorketes himself.<br />

In contrast, the prow on the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> can hardly have been intended to<br />

symbolise a fleet. Neighbouring <strong>Pagasai</strong> was the harbour of Pherai under the<br />

37 Kron – Furtwängler 1983, p. 168 (Furtwängler); Moustaka 1983, p. 35.<br />

38 For the coins of Antigonos Doson, see SNG München (Makedonien: Könige) 1121-3; for related<br />

discussion, see Kron – Furtwängler 1983, pp. 165-7 (Furtwängler) <strong>and</strong> Moustaka 1983, p. 35.<br />

39 Rogers 1932, pp. 119-20, nos 373-4, fig. 191 (Alex<strong>and</strong>er Severus); p. 120, no. 375, fig. 193<br />

(Maximinus); p. 122, no. 379, fig. 196 (Gordian III); pp. 122-3, no. 380, figs 197-8 (Trebonianus<br />

Gallus); p. 123, no. 380, fig. 199 (Valerian Senior); p. 123, no. 381 (Gallienus). See also Voegtli<br />

1977, p. 136.<br />

40 Kron – Furtwängler 1983, p. 168 (Furtwängler); Moustaka 1983, p. 35.<br />

41 BMC (Phoenicia) p. 196, no. 309, Pl. 25, no. 7; p. 199, no. 322 (Alex<strong>and</strong>er Severus); ibid., p.<br />

cxv (with n. 2) reports a coin of Soaimias with the legend ARG[O] in Berlin; Blatter 1984, pp. 591-<br />

9, no. 8, s.v. Argonautai. See also Voegtli 1977, p. 137.<br />

42 Kron – Furtwängler 1983, pp. 147-68, Pls 1-9; see especially Pl. 2, 3c-e.<br />

43 Kron – Furtwängler 1983, pp. 149-51, 162-3 (Kron), where it is clear that there was in Greek art<br />

a tradition of depicting the founders of cities on the prow of a ship; Leschhorn 1984, p. 266.<br />

44 Kron – Furtwängler 1983, p. 149 (Furtwängler).<br />

45 Batziou–Efstathiou 2000, p. 299, figs 13-4.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 29<br />

Pheraian tyrants <strong>and</strong> under Philip II (see below), <strong>and</strong>, whereas the sources refer<br />

constantly to the harbour of <strong>Pagasai</strong>, they never mention one at <strong>Iolkos</strong>. <strong>Iolkos</strong> is<br />

unlikely to have developed her own harbour to rival that of <strong>Pagasai</strong> or to have<br />

acquired a fleet. The prow will therefore have been a symbol of the city rather<br />

than of a fleet, <strong>and</strong> as such will surely have been that of the Argo. Note also that<br />

the prow on the coins bears a clear resemblance, right down to details, to the<br />

prow of the Argo depicted on an Archaic metope (c.570 BC) at Delphi which<br />

was reused as building material in the later Treasury of the Sikyonians, although<br />

it is in fragmentary condition <strong>and</strong> the stem-post is missing. 46 Whether the<br />

Iolkians had any connection with the Archaic metope at Delphi, or had a similar<br />

monument in their own city is not known.<br />

Finally, it should be noted that the slightly curving stem-post on the prow of<br />

the <strong>Iolkos</strong> coins has a decorative element at the top, which bears no resemblance<br />

to the goose’s head or fillet that occur on other stem-posts (see Pl. 3, 1c). 47 I<br />

suggest that it may be a schematised branch with a leaf, for Apollonios Rhodios<br />

(Argon. I, 526-7; IV, 582-3) records that Athena attached to the prow of the Argo<br />

a piece of wood cut from an oak in the sacred forest of Dodona, which could<br />

speak <strong>and</strong> forecast the future: ������������������������������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������� 48 The word ������ refers to the keel<br />

of the ship, where the oak wood was placed. Apollodoros, Biblioth. I, IX, 16,<br />

likewise reports that Athena attached the oak wood to the prow: ����� ��� ����<br />

������� ���������� ������ ������� ������ ���� ���������� �����. So too the<br />

Orphics (Argon. 266-8; similar information in 1155-7): ��� ����� �������������<br />

��������� ������ �������� ��� ��� ����������� ������ ����� ���� �������� �� ���������<br />

����������. If the decoration on the stem-post is a branch, the prow must be that<br />

of the �������� ���� (Orph., Argon. 244). A column krater of 470-460 BC<br />

depicts a female head on the stem-post of the Argo, which Richter believed was<br />

reminiscent of the sacred wood that pronounced oracles; she thought the scene<br />

was inspired by Aischylos (fr. 8). 49<br />

There thus seems little doubt that the prow on our coins was that of the Argo.<br />

One might compare the prow of the Samaina on silver (469-440/439 <strong>and</strong> 398-<br />

365 BC) <strong>and</strong> bronze (412-405 <strong>and</strong> 390-190 BC) coins of Samos. 50 This has been<br />

interpreted as the ���������, or emblem, of the city, like the ship’s prow on the<br />

coins of other cities, for example Apollonia Pontica. 51<br />

46 Marcadé – Croissant 1991, pp. 42-4, fig. 8c; see also Blatter 1984, p. 593, no. 2, s.v.<br />

Argonautai; Basch 1987, p. 240, figs 501-3, especially 502.<br />

47<br />

Basch 1987, p. 428, fig. 928 (goose’s head); Blatter 1984, p. 594, no. 10, s.v. Argonautai (fillet).<br />

48<br />

Papachatzis (1984, p. 145) interprets the oak bough as evidence that the local inhabitants<br />

practised magic before the appearance of Medea.<br />

49<br />

Richter 1935, pp. 182-4, figs 1-2; see also Hammond – Moon 1978, p. 377, fig. 7.<br />

50<br />

Barron 1966, Pl. 9, nos 33-4; Pl. 16, nos 1-6; Pl. 22, nos 1-7; Pl. 27, nos 1-2; Pl. 31, nos 7, 11.<br />

51 Stankov 1996, pp. 23-8.

30<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

As we have seen, the head of Artemis on the Iolkian coins has parallels with<br />

female heads in sculpture <strong>and</strong> especially on coins datable to the middle of the<br />

4th century BC <strong>and</strong> onwards, while their flans are similar to those of other<br />

<strong>Thessalian</strong> coins from before <strong>and</strong> around the middle of the 4th century BC. The<br />

foundation of Demetrias in 294/293 BC provides a terminus ante quem. It thus<br />

seems reasonable to date the Iolkian coins to around the middle or second half<br />

of the fourth century. The principal political event for the cities of the Pagasitic<br />

gulf in this period was, as we shall see, the overthrow of the tyrants of Pherai by<br />

Philip II, after which the cities became autonomous. This would be a plausible,<br />

if unprovable, occasion for <strong>Iolkos</strong> to issue her own coins. The choice of types,<br />

Artemis Iolkia <strong>and</strong> the prow of the Argo, emphasises the cult of the most<br />

important local divinity <strong>and</strong> the famous expedition that sailed from <strong>Iolkos</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

would serve to express the independence of the Iolkians. 52<br />

PAGASAI<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong> is connected with the expedition of the Argonauts. According to Strabo<br />

IX, 5, 15, its name derived either ����������������������������, since the Argo<br />

was built there, or from its abundant springs. 53 In the 4th century, Pseudo-<br />

Skylax (Peripl. 64 [GGM I, pp. 50-1], {Müller}) refers to Classical <strong>Pagasai</strong> 54 as<br />

a ����� <strong>and</strong> ������������. Strabo IX, 5, 15, describes <strong>Pagasai</strong> as a polichne when<br />

it took part in the synoecism of Demetrias, but, as we have seen above, he seems<br />

to use this word indiscriminately when referring to the various settlements, big<br />

<strong>and</strong> small, which made up the synoecism. Pliny, NH IV, 29, states that <strong>Pagasai</strong><br />

was renamed Demetrias.<br />

The history of <strong>Pagasai</strong> is covered more fully than that of <strong>Iolkos</strong> in the ancient<br />

sources. 55 Xerxes sailed to it with his fleet before the battle of Salamis, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Greek fleet stayed in its harbour immediately after the battle (Herodotos VII,<br />

193; Plutarch, Them. XX, 1). In the middle of the 5th century BC, Hermippos<br />

52 The theme was of course familiar. Larisa, for example, depicted Jason’s s<strong>and</strong>al on its earliest<br />

coins of Persian <strong>and</strong> Aiginetan weight; his head in a petasos also occurs on some issues: Herrmann<br />

1925, pp. 3-4, Pl. 1, nos 1-5; p. 9, Pl. 1, no. 6; p. 21, Pl. 2, nos 5-6.<br />

53 For further suggestions concerning the etymology, see Arvanitopoulos 1928, pp. 15, 71-2;<br />

Meyer 1942, cols 2297-9, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>. For discussion of the location of <strong>Pagasai</strong> in the Mycenaean<br />

period, see Stählin 1924, pp. 66-8; Stählin 1928, cols 470-1, s.v. Magnesia (1); Meyer 1942, cols<br />

2299-2304, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>; Batziou–Efstathiou 1992, pp. 279-85; Batziou–Efstathiou (Volos 1994),<br />

pp. 59-69; Intzesiloglou 1994, pp. 42-5.<br />

54 For discussion on the location of Classical <strong>Pagasai</strong>, see Batziou–Efstathiou 1996, pp. 11-2<br />

(northern part of Demetrias); Intzesiloglou 1994, pp. 32-3, 43-5, 49-50, Pl. II (Nees Pagases);<br />

Intzesiloglou 1996, p. 97; Marzolff 1996, pp. 47-9, fig. 1 (Soros); for the Archaic sanctuary of Soros,<br />

perhaps of that of Apollo <strong>Pagasai</strong>os, <strong>and</strong> the finds, see Bakhuizen (1987), p. 323. See also<br />

Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–Atzaka – Makris 1982, p. 99 (Hourmouziadis); Di Salvatore<br />

1994, pp. 115-6; Reinders 2003, p. 19.<br />

55 Meyer 1942, col. 2307-9, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 31<br />

reports (Athenaios, Deipnos. I, 27 f. Hermippos [Comicorum Atticorum<br />

Fragmenta I {Kock}, 63, l. 19]) that it had an extensive slave trade, which<br />

continued during the 4th century in Thessaly. The harbour of <strong>Pagasai</strong> certainly<br />

h<strong>and</strong>led import-export trade (Athenaios, Deipnos. III, 112b; Plutarch, Apophth.<br />

Reg. 17E, Epaminondas). Xenophon, Hell. V, 4, 56, reports that in 377 BC the<br />

Thebans, hit by a crop failure, sent two triremes to <strong>Pagasai</strong> to buy grain to the<br />

value of ten talents of silver. In 373 BC on his way to Thrace with the Athenian<br />

fleet, Timotheos stopped at the harbour of <strong>Pagasai</strong> where he met Jason the tyrant<br />

of Pherai. 56 Polyainos (Strat. VI, 1, 6; VI, 2, 1) notes the subservience of <strong>Pagasai</strong><br />

to Pherai, 57 particularly to the tyrants Jason <strong>and</strong> Alex<strong>and</strong>er, <strong>and</strong> tells us that<br />

Jason, who lived in Pherai, was poor, while his brother Meriones, who lived in<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong> <strong>and</strong> derived money from the port, was rich; in his absence, Jason stole<br />

20 talents of silver from him. 58 Alex<strong>and</strong>er of Pherai had a close connection with<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong> since members of his family, <strong>and</strong> sometimes he himself, stayed there<br />

(Polyainos, Strat. VI, 1, 6). The home port of his fleet was <strong>Pagasai</strong>, which he<br />

fortified with strong walls (Polyainos, Strat. VI, 2, 1; Theopompos FGrHist 115<br />

F352). 59 He was worshipped there as founder <strong>and</strong> the cult was transferred to<br />

Demetrias. 60<br />

The situation changed when Philip II of Macedon entered the region, at the<br />

request of the Aleuadai of Larisa, to confront the Pheraian tyrants in 354/353<br />

BC, <strong>and</strong> captured <strong>Pagasai</strong>. 61 Ten years later Pherai finally fell to Philip, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

cities of Magnesia achieved their independence (Diod. XVI, 69, 8; Demosth.<br />

XIX, 260; Hegesippos in Demosth. VII, 32; Demosth. VIII, 59). 62 Demosthenes<br />

(I, 22) adds that Philip held on to the harbour taxes from <strong>Pagasai</strong>, which<br />

obviously gave him a significant income. 63 On the basis of Demosthenes <strong>and</strong><br />

56<br />

Sprawski 1999, p. 90.<br />

57<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong> was identified variously as a <strong>Thessalian</strong> city (Pseudo-Skyl., Peripl. 64 [GGM I, pp. 50-<br />

1 {Müller}]; Etym. Magn. 646, 39), as Phthiotian (Ptolem. III, 13, 17) <strong>and</strong> as Magnesian (Apoll.<br />

Rhod., Argon. I, 238). Theopompos (FGrHist 115 F53) (Harpokration, s.v.� �������) knows it as�<br />

��������� ������� shortly before the middle of the 4th century BC, information repeated by Strabo<br />

(IX, 5, 15), Eustathios (ad Hom., Il. II, 711) <strong>and</strong> Photios (Lexicon, s.v. �������).<br />

58<br />

Sprawski 1999, pp. 51-2.<br />

59<br />

Arvanitopoulos 1928, pp. 78, 80 (with n. 1) suggests that the slave trade required a walled city<br />

in order to prevent escapes.<br />

60<br />

Leschhorn 1984, p. 267.<br />

61<br />

Sordi 1958, pp. 243-60; for the problems concerning the capture of <strong>Pagasai</strong>, see pp. 355-7;<br />

Hammond – Griffith 1979, pp. 259-64, 267-81, 285-95 (Griffith). For the course of events, see<br />

Demosth. I, 9; 12-13; Diod. XVI, 34, 4-5; 35, 1-3 <strong>and</strong> 3-6; 31, 6; 37, 3; 38, 1: here the toponym<br />

������� in the manuscripts must surely be corrected to <strong>Pagasai</strong> - see Martin 1981, pp. 191, 193-5,<br />

197-8; Di Salvatore 1981-2, pp. 35-7.<br />

62<br />

Sordi 1958, pp. 275-93; Hammond – Griffith 1979, pp. 523-44 (Griffith); Di Salvatore 1981-2,<br />

pp. 30-4 (with earlier bibliography). Martin 1981, pp. 188-201, argues that Pherai fell after the<br />

capture of <strong>Pagasai</strong>; see also Di Salvatore 1981-2, pp. 34-48. Griffith argues that Pherai was captured<br />

before <strong>Pagasai</strong>: Hammond – Griffith 1979, p. 278.<br />

63<br />

Sprawski 1999, pp. 54, 112.

32<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

other sources, Bakhuizen 64 argues that when Philip took <strong>Pagasai</strong>, he gave it to<br />

the Magnetes until 344 BC; then, in response to a request from the <strong>Thessalian</strong>s,<br />

he gave them the city because of the importance of its harbour.<br />

In 341 or 340, the politician Kallias of Chalkis 65 in alliance with Athens seized<br />

all the cities of the Pagasitic gulf, among them presumably <strong>Pagasai</strong><br />

(Demosthenes, Epist. [Philipp.] XII, 5). This was, however, a temporary<br />

situation. <strong>Two</strong> inscriptions, one from Delphi (c.325 BC) <strong>and</strong> one from Argos<br />

(time of Alex<strong>and</strong>er III), make it clear that <strong>Pagasai</strong> was an independent city from<br />

354/353 to 294/293 BC; in both the inhabitants are referred to as Pagasitans. 66<br />

After the synoecism of <strong>Pagasai</strong> into Demetrias, the Pagasitans shared the<br />

fortunes of Demetrias, as is evident from inscriptions of the Koinon of the<br />

Magnetes that refer to Aitolion son of Demetrius with his demotic as a<br />

Pagasitan. 67<br />

In 1794 Eckhel 68 described an autonomous coin with the legend ����������<br />

within a wreath of ivy leaves. He referred to Goltz, who was the first to attribute<br />

the coin to <strong>Pagasai</strong> (with an engraved illustration) <strong>and</strong> who was followed by<br />

Gessner <strong>and</strong> Bentinck, while Sestini attributed it to Parion. 69 Eckhel also<br />

suspected that it was issued by Parion. No other specimen has been recorded,<br />

<strong>and</strong> if the coin is not one of Goltz’s many fantasies, 70 it may perhaps belong to<br />

Paros: there is no reason to give it to either <strong>Pagasai</strong> or Parion.<br />

We now have a unique bronze coin whose ethnic puts its attribution beyond<br />

doubt:<br />

Obv. Laureate head of Apollo <strong>Pagasai</strong>os three quarter facing r. Border of dots.<br />

Rev. ���������������. Seven-stringed lyre. Pl. 3, 3.<br />

Die-Axis (h) Wt. (g)<br />

1. 05 2.34 Private Collection, <strong>New</strong> York; found near Volos.<br />

With a diameter of 13mm <strong>and</strong> weight of 2.34g, the coin is comparable to those<br />

of <strong>Iolkos</strong>, <strong>and</strong> is probably likewise a chalkous. Like the Iolkian coins, it has a<br />

thick flan. The letters of the ethnic, like those on the coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong>, seem to be<br />

4th century BC in date, though it is impossible to be more precise. The ethnics<br />

recorded elsewhere for the citizens of <strong>Pagasai</strong> are ����������� ����������<br />

��������� (poetic), the possessive ��������������, <strong>and</strong> ���������. 71 The<br />

Pagasites that corresponds to the legend of the coin is known as an ethnic in<br />

64 Bakhuizen 1987, pp. 320-1, 324-5.<br />

65 Meyer 1942, col. 2308, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>; Hammond – Griffith 1979, pp. 593-5 (Griffith).<br />

66 Bousquet 1988, pp. 183-4 (with n. 11); IG IV, 617, l. 4.<br />

67 IG IX 2, 1100, l. 4-5; IG IX 2, 1109, l. 4.<br />

68<br />

Eckhel 1794, p. 146.<br />

69<br />

Goltz 1708, p. 116 (Nomismata Insularum Graeciae, Pl. 21); Gessner 1738, Pl. 49, no. 19;<br />

Sestini 1779, p. 28, no. 23; Bentinck 1787, p. 1006.<br />

70<br />

See for example Masson 1991, pp. 60-5. I owe this reference to Richard Ashton.<br />

71<br />

Meyer 1942, col. 2298, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>. For the characterisation of Jason <strong>and</strong> Apollo as <strong>Pagasai</strong>os<br />

<strong>and</strong> Artemis as Pagasitis, see also Kruse 1942, col. 2309, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>os.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 33<br />

Classical <strong>and</strong> later sources, including an inscription of the Koinon of the<br />

Magnetes, where, as we have seen, Pagasites is used as a demotic. 72 The same<br />

epithet is given to Apollo by Hesychios (s.v. ���������).<br />

The head on the obverse, which has a modest beauty, is not large; the face is<br />

long <strong>and</strong> delicately worked, without plastic mass. It is framed by hair rendered<br />

on the right as a solid mass, on the left as wavy ringlets. The neck is short; the<br />

eyes are narrow, <strong>and</strong> the eyeballs drawn in linear fashion. The lips, rendered as<br />

parallel lines, enclose a small mouth. These features occur also on the head of<br />

Artemis Iolkia on the bronzes of <strong>Iolkos</strong>.<br />

Chronologically the head is datable near the middle of the 4th century BC <strong>and</strong><br />

recalls the heads on coins of the cities of Magnesia: the Maenad on the bronzes<br />

of Eurea, 73 <strong>and</strong> the eponymous nymph on the coins of Meliboia. 74 There is<br />

some, but less, similarity with the heads on other <strong>Thessalian</strong> coins: the nymph of<br />

Larisa, 75 the Hera of the Gomphoi, 76 the hero (Gyrton?) of Gyrton, 77 the Athena<br />

of Pharsalos, 78 a nymph at Skotoussa, 79 the Lapith Mopsos on the bronzes of<br />

Mopsion, 80 the Hera on the bronzes of Perrhaiboi, 81 <strong>and</strong> the nymph Boura (?) on<br />

an obol of Atrax. 82 There is also a correspondence with a silver coin of Pherai<br />

(350 BC) <strong>and</strong> with its bronzes of the 4th century BC. 83 One may also make<br />

stylistic comparisons with the Apollo on coins from mints outside Thessaly,<br />

such as Amphipolis, 84 Philip II 85 <strong>and</strong> Rhodes. 86 The stylistic congruence of the<br />

head with the general artistic climate of the time is also clear from parallels with<br />

72 Meyer 1942, col. 2298, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>; IG IX 2, 1100, l. 4-5; IG IX 2, 1109, l. 4.<br />

73 Rogers 1932, pp. 74-5, nos 210-1a, fig. 89; Warren 1961, p. 1, Pl. 1, 1 (with a discussion as to<br />

whether Eurea belonged to Magnesia).<br />

74 Rogers 1932, p. 128, no. 390, fig. 204 (1st half of 4th cent. BC); Warren 1961, pp. 1-3, figs 4<br />

(silver), 6 (bronze).<br />

75<br />

Herrmann 1925, p. 41, Pl. 5, nos 4-14 (Group VII, Series A); p. 45, Pl. 7, nos 6-8 (Group VII,<br />

Series M). According to the redating proposed by Martin 1983, pp. 1-34, especially p. 33, this series<br />

belongs to the so-called last phase, dated conventionally between 375-320 BC. Lorber 2000, pp. 8-<br />

12, 14, Pl. 3 (Late II) dates her Late Phase to the period beginning with the interference of Philip II<br />

in the affairs of Thessaly.<br />

76<br />

Rogers 1932, p. 76, no. 214, fig. 92 (2nd half of 4th cent. BC).<br />

77<br />

Rogers 1932, p. 81, no. 229, figs 104-5 (2nd half of 4th cent. BC).<br />

78<br />

Lavva 2001, Pl. 16, nos 354-5. The high chronology proposed by the author, c.424-405/404 BC,<br />

is not convincing. The coins in question belong to the 4th century BC.<br />

79<br />

Rogers 1932, p. 172, no. 543, fig. 300 (1st half of 4th cent. BC).<br />

80<br />

Rogers 1932, pp. 135-6, no. 412, fig. 221 (1st half of 4th cent. BC).<br />

81<br />

Rogers 1932, pp. 143-4, no. 438, fig. 238 (1st half of 4th cent. BC).<br />

82<br />

Demetriadi 2000, pp. 47-8, Pl. 6, no. 1.<br />

83<br />

Moustaka 1983, p. 110, no. 67, Pl. 10 (silver). For the bronze, see Rogers 1932, p. 163, no. 511,<br />

fig. 277.<br />

84<br />

Lorber 1990, Pl. 12, fig. 56 (Type L, c.359/358 BC); Pl. 30, nos 65e-f (370/369 BC).<br />

85<br />

Le Rider 1977, pp. 395-6, Pl. 43, nos 504-6 (Amphipolis II, B).<br />

86 Ashton 2001, nos 100-3 (c.385-late 340s BC).

34<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

the coins of Morgantina of the time of Timoleon 87 <strong>and</strong> of Pixodaros, satrap of<br />

Caria. 88<br />

The laurel-wreath rules out the identification of the head as the hero-founder<br />

Pagasos, said to have been one of the Hyperboreans (Paus. I, 5, 8), but it <strong>and</strong> the<br />

seven-stringed lyre on the reverse strongly suggest Apollo, presumably the local<br />

Apollo <strong>Pagasai</strong>os (Etym. Magn. 646, 39) or Pagasites (Hesych., s.v.<br />

���������). 89 Herakleides Pontikos (Schol. ad Hes., Sc. 70= 137, fr. III<br />

{Tresp}) <strong>and</strong> the Scholia to Apollonios Rhodios (Argon. I, 238) both refer to a<br />

sanctuary of Apollo <strong>Pagasai</strong>os, while the poet himself mentions the god’s altar,<br />

which was built by the Argonauts before their expedition <strong>and</strong> on which they<br />

sacrificed (Argon. I, 359-60, 402-47). Hesiod (Sc. 70) refers to the grove of<br />

Apollo <strong>Pagasai</strong>os where his altar stood. Arvanitopoulos believes that Apollo<br />

<strong>Pagasai</strong>os was also honoured in <strong>Pagasai</strong> in Archaic times with other epithets, all<br />

mentioned by Apollonios Rhodios (Argon. I, 359, 404, 966, 1186). 90 He regards<br />

Apollo Koropaios as a late form of <strong>Pagasai</strong>os. 91 The lyre on the reverse is<br />

connected with Apollo in his role as Kitharoidos, <strong>and</strong>, either full figure or head,<br />

he is depicted on <strong>Thessalian</strong> coins as Kitharoidos or Mousagetes, attesting the<br />

musical tradition of the region during Classical <strong>and</strong> Imperial times. 92<br />

The coinage of <strong>Pagasai</strong> was modest, to judge from the single known coin,<br />

although more pieces may well turn up in future excavations. Its terminus ante<br />

quem is the foundation of Demetrias, after which <strong>Pagasai</strong> soon declined into a<br />

village. The terminus post quem is likely to be 354/353 BC, when the city was<br />

liberated by Philip II, after his ejection of the Pheraian tyrants. As we have seen,<br />

a date around the middle of the 4th century BC is also suggested by stylistic<br />

criteria. Scholars such as Beloch, Arvanitopoulos, Stählin <strong>and</strong> Bousquet 93 have<br />

remarked on the lack of Pagasitan coinage, although it was an economically<br />

powerful polis. I suggest that the Pheraian tyrants had drained the city of its<br />

wealth <strong>and</strong> inhibited the issue of coinage.<br />

It is difficult to determine whether these small issues of <strong>Pagasai</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Iolkos</strong><br />

should be dated immediately after the capture of <strong>Pagasai</strong> in 354/353 BC or after<br />

Pherai came finally into the h<strong>and</strong>s of Philip II in 344/343 BC. The head of<br />

Artemis Iolkia supports the lower chronology because of the striking stylistic<br />

87<br />

SNG Ashmolean 1857.<br />

88<br />

Weber 6608.<br />

89<br />

Kruse 1942, col. 2309, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>os; Moustaka 1983, p. 36.<br />

90<br />

Arvanitopoulos 1928, p. 77.<br />

91<br />

IG IX 2, 1109, l. 9-10. Arvanitopoulos (1928, p. 76) believes that the oracle of the god,<br />

established by Trophonios, was transferred to Korope, a more peaceful <strong>and</strong> suitable spot for oracles.<br />

92<br />

Moustaka 1983, pp. 36-8; Moustaka 1997, pp. 89-93; for the Imperial period, see Franke 1992,<br />

pp. 370-5, Pl. 81.<br />

93 Beloch 1911, p. 443; Stählin 1924, p. 67; Arvanitopoulos 1928, p. 79; Bousquet 1988, p. 184<br />

(with n. 11). Beloch 1914, p. 82, describes <strong>Pagasai</strong> as the ‘Haupthafen von Thessalien’ <strong>and</strong> a<br />

‘blühende H<strong>and</strong>elsstadt’.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 35<br />

parallels with the coins of Orthagoreia <strong>and</strong> of Philip II. They are unlikely to be<br />

commemorative coinages, which were normally struck in precious metal,<br />

though the discovery of silver coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong> in the future cannot of<br />

course be ruled out. <strong>Iolkos</strong> is not recorded in the ancient sources as being<br />

directly involved in the events surrounding the capture of Pherai <strong>and</strong> the<br />

overthrow of its tyrants, but it is clear that its fortunes depended on Pherai, for<br />

they were neighbours, <strong>and</strong> the fact that <strong>Iolkos</strong> participated in the synoecism of<br />

Demetrias suggests a direct connection with Pherai.<br />

In corroboration of our conclusions about <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong>, note that in an<br />

important article Warren 94 argues convincingly that some other Magnesian<br />

cities, Eurea, Eurymenai, Rhizous <strong>and</strong> Meliboia, issued stylistically <strong>and</strong><br />

technically similar coins with the common motif of a bunch of grapes; she dates<br />

them to the middle of the 4th century BC, specifically to immediately after the<br />

first incursion of Philip II into Thessaly.<br />

None of the other settlements or small towns near <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong> are<br />

known to have issued coins after the interventions of Philip II, 95 presumably<br />

because few if any of them were cities. The coins of <strong>Iolkos</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pagasai</strong> show<br />

that they were cities in the Classical sense of the word. Cities that issue coins<br />

generally meet certain basic conditions: they must be independent, their market<br />

must work well <strong>and</strong> they must be fortified. 96 The ancient sources <strong>and</strong><br />

archaeology have established that both cities satisfied the first <strong>and</strong> third<br />

conditions, while their coinages, apparently brief though they were, suggest that<br />

they satisfied the second as well.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Adler 1916, s.v. Iolkia A. Adler, in RE IX, 2 (Stuttgart 1916), col. 1850, s.v. Iolkia.<br />

Adrymi–Sismani 1992 V. Adrymi–Sismani, ��������������������������������, in �����������������<br />

���� ���� ������� ��������� ���� ������ ���� ����� ��������� �������� (Athens<br />

1992), pp. 272-8.<br />

Adrymi–Sismani (Volos 1994)<br />

V. Adrymi–Sismani, ���������������������������������������������������<br />

�����������������, in ���������������������������������������������������<br />

��������� ��������������������������������������������� (Volos 1994),<br />

pp. 17-43.<br />

Adrymi–Sismani 2000 V. Adrymi–Sismani, ����������������������������������������, in ��������<br />

���� ��������� ������������ ���� ��������� ��������� ���� ������� ����<br />

��������� ���� ����� ��������� �������� ���� ������������� � � � �������������<br />

����������������������� 1998 (Volos 2000), pp. 279-91.<br />

94 Warren 1961, pp. 1-5.<br />

95 A little to the south, Halos issued coins in the 4th <strong>and</strong> 3rd centuries: Reinders 1988, pp. 164-6,<br />

236-9, 240-1 (Groups A–B, Helle); pp. 241-5 (Groups C–D, Phrixos); pp. 246-51, figs Series 1-21;<br />

Reinders 2003, pp. 143, 322.<br />

96 Sakellariou 1989, p. 492.

36<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

Arvanitopoulos 1928 A. Arvanitopoulos, �������� ������� ������������ �� �������� (Athens<br />

1928).<br />

Ashton 2001 R.H.J. Ashton, ‘The Coinage of Rhodes 408-c.190 BC’, in A. Meadows –<br />

K. Shipton (eds), Money <strong>and</strong> its Uses in the Ancient Greek World (Oxford<br />

2001), pp. 79-115.<br />

Bakhuizen 1979 S.C. Bakhuizen, ‘Goritsa, A Survey’, in La Thessalie. Actes de la Table–<br />

Ronde, 21-24 Juillet 1975, Lyon (Lyon 1979), pp. 63-4.<br />

Bakhuizen 1987 S.C. Bakhuizen, ‘Magnesia unter makedonischer Suzeränität’, in<br />

Demetrias V (Bonn 1987), pp. 319-38.<br />

Barron 1966 J.P. Barron, The Silver Coins of Samos (London 1966).<br />

Basch 1987 L. Basch, Le Musée imaginaire de la marine antique (Athens 1987).<br />

Batziou–Efstathiou 1992 A. Batziou–Efstathiou, ���������� ������������ � �������� ����� ���������<br />

�������� ���� ��������� �����������, in �������� ��������� ���� ���� �������<br />

��������������������������������������������� (Athens 1992), pp. 279-<br />

85.<br />

Batziou–Efstathiou (Volos 1994)<br />

A. Batziou–Efstathiou, �������������� ���� ���������� ������������<br />

���������������������������������������������������� in �����������������<br />

���� �������� ���� ���� ������� ������� ��������� �������������� ������������<br />

������������������� (Volos 1994), pp. 59-69.<br />

Batziou–Efstathiou 1996 A. Batziou–Efstathiou, ������������������������������������������������,<br />

in E. Kontaxi (ed.), ������� ������������ �� ��������� ���� ����� �������<br />

����������������������������������� (Volos 1996), pp. 11-43.<br />

Batziou–Efstathiou 2000 A. Batziou–Efstathiou, ���������� ���� ��������� ������������ ����������,<br />

in ������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������������������������� � ��������������<br />

����������������������� 1998 (Volos 2000), pp. 293-300.<br />

Beloch 1911 K.J. Beloch, ‘Zur Karte von Griechenl<strong>and</strong>’, Klio 11 (1911), pp. 442-5.<br />

Beloch 1914 K.J. Beloch, Griechische Geschichte II. 1 (Strasbourg 1914).<br />

Bentinck 1787 D. de Bentinck, Catalogue d’une collection de medailles antiques II<br />

(Amsterdam 1787).<br />

Biesantz 1965 H. Biesantz, Die thessalischen Grabreliefs. Studien zur nordgriechischen<br />

Kunst (Mainz am Rhein 1965).<br />

Blatter 1984, s.v. Argonautai<br />

R. Blatter, in LIMC II (Zurich–Munich 1984), pp. 591-9, s.v. Argonautai.<br />

Boston A. Baldwin Brett, Catalogue of Greek Coins. Museum of Fine Arts,<br />

Boston (Boston 1955).<br />

Bousquet 1988 J. Bousquet, Études sur les comptes de Delphes (BEFAR 267; Paris<br />

1988).<br />

BMC (Thessaly to Aetolia)<br />

P. Gardner, A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum.<br />

Catalogue of Greek Coins Thessaly to Aetolia (London 1883).<br />

BMC (Phoenicia) G.F. Hill, A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum.<br />

Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Phoenicia (London 1910).<br />

Cohen 1995 G.M. Cohen, The Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Isl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> Asia<br />

Minor (Berkeley–Los Angeles–Oxford 1995).<br />

Demetriadi 2000 V. Demetriadi, ‘Some <strong>New</strong> Fractions from Central <strong>and</strong> Southern Greece’,<br />

in S. Mani Hurter – C. Arnold–Biucchi (eds), Pour Denyse.<br />

Divertissements Numismatiques (Bern 2000), pp. 47-57.<br />

Di Salvatore 1981-2 M. Di Salvatore, La citta tessala di Fere in epoca classica (unpubl.<br />

Thesis, Milan 1981-2), pp. 97-154 (Ch. 3: ��������������������������������

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 37<br />

������������������������������������������������������������������ 24<br />

(1993), pp. 30-48 [trans. K. Desli–Apostolaki]).<br />

Di Salvatore 1994 M. Di Salvatore, ‘Ricerche sul territorio di Pherai. Insediamenti, difese,<br />

vie e confini’, in La Thessalie. Quinze années de recherches<br />

archéologiques, 1975-1990. Bilans et perspectives. Actes du colloque<br />

international Lyon, 17-22 avril 1990, Vol. B (Athens 1994), pp. 93-124.<br />

Doumas 2003 Chr. Doumas, ��������������������������������, in Proceedings of the 7th<br />

Forum for the Debate on the Mediterranean Maritime Heritage.<br />

Mediterranean Sea Routes. Athens, 1-2 November 2000 (Athens 2003),<br />

pp. 21-31.<br />

Drexler 1890-4 W. Drexler, in Roscher Lexikon II, 1 (Leipzig 1890-4), col. 290, s.v.<br />

Iolkia.<br />

Eckhel 1794 J.H. Eckhel, Doctrina Numorum Veterum �, II (Vienna 1794).<br />

Franke 1967 P.R. Franke, ����������������, AA 82 (1967), pp. 62-4.<br />

Franke 1992 P.R. Franke, �����������������������������, in �������������������������<br />

������� ��������� ���� ������ ���� ����� ��������� �������� (Athens 1992),<br />

pp. 370-5.<br />

Furtwängler 1990 A. Furtwängler, Demetrias. Eine makedonische Gründung im Netz<br />

H<strong>and</strong>els- und Geldpolitik (unpubl. habilitation, Saarbrücken 1990).<br />

Gaebler 1935 H. Gaebler, Die Antiken Münzen Nord–Griechenl<strong>and</strong>s III, 2 (Berlin<br />

1935).<br />

Gessner 1738 J.J. Gessner, Numismata regum Macedoniae (Zurich 1738).<br />

Goltz 1708 H. Goltz, De re nummaria antiqua opera quae extant universa, III, L.<br />

Nonnii, Commentarius in Huberti Goltzii Graeciam (Antwerp 1708).<br />

Nomismata Insularum Graeciae, Pl. XXI.<br />

Hammond – Moon 1978 N.G.L. Hammond – W.G. Moon, ‘Illustrations of Early Tragedy at<br />

Athens’, AJA 82 (1978), pp. 377-88.<br />

Hammond – Griffith 1979 N.G.L. Hammond – G.T. Griffith, A History of Macedonia II (Oxford<br />

1979).<br />

Helly 1971 Br. Helly, ‘Décrets de Démétrias pour des juges étrangers’, BCH 95<br />

(1971), pp. 543-59.<br />

Herrmann 1925 F. Herrmann, ‘Die Silbermünzen von Larissa in Thessalien’, ZfN 35<br />

(1925), pp. 1-69.<br />

Höckmann 1985 O. Höckmann, Antike Seefahrt (Munich 1985).<br />

Hourmouziadis – Asimakopoulou–Atzaka – Makris 1982<br />

G. Hourmouziadis – P. Asimakopoulou–Atzaka – K.A. Makris,<br />

Magnesia. The Story of a Civilization (Athens 1982).<br />

Jessen 1914 O. Jessen, in RE IX, 1 (Stuttgart 1914), cols 759-71, s.v. Iason.<br />

Intzesiloglou 1994 Ch. Intzesiloglou, ���������� ����������� ���� ��������� ���� ������� ����<br />

������, in La Thessalie. Quinze années de recherches archéologiques,<br />

1975-1990. Bilans et perspectives. Actes du colloque international Lyon,<br />

17-22 avril 1990, Vol. B (Athens 1994), pp. 31-56.<br />

Intzesiloglou (Volos 1994)<br />

Ch. Intzesiloglou, �����������������������������������������������������,<br />

in �������� ��������� ���� �������� ���� ���� ������� ������� ���������<br />

���������������������������������������� 1993 (Volos 1994), pp. 71-83.<br />

Intzesiloglou 1996 Ch. Intzesiloglou, �������������������������������������������������������<br />

���������������������������������������������������������, in E. Kontaxi<br />

(ed.), ������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

��������� 1994 (Volos 1996), pp. 91-111.

38<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

Kahil – Icard 1984 L. Kahil – N. Icard, in LIMC II (Zurich–Munich 1984), p. 671, s.v.<br />

Artemis.<br />

Kron – Furtwängler 1983 U. Kron – A. Furtwängler, ‘Demetrios Poliorketes, Demetrias und die<br />

Magneten. Zum Bedeutungsw<strong>and</strong>el von Siegel– und Münzbild einer<br />

Stadt’, in ANCIENT MACEDONIA III. Papers read at the third<br />

International Symposium held in Thessaloniki September 21-25, 1977<br />

(Thessaloniki 1983), pp. 147-68.<br />

Kruse 1942 B. Kruse, in RE XVIII, 2 (Stuttgart 1942), col. 2309, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>os.<br />

Lavva 2001 S. Lavva, Die Münzprägung von Pharsalos (Saarbrücken 2001).<br />

Le Rider 1977 G. Le Rider, Le monnayage d’ argent et d’ or de Philippe II frappée en<br />

Macédoine de 359 à 294 (Paris 1977).<br />

Leschhorn 1984 W. Leschhorn, Gründer der Stadt. Studien zu einem politisch–religiösen<br />

Phänomen der griechischen Geschichte (Palingenesia XX; Stuttgart<br />

1984).<br />

Liampi 1998 K. Liampi, ‘Ekkarra, eine Stadt der Achaia Phthiotis: ihre Lage nach den<br />

numismatischen Zeugnissen’ in U. Peter (ed.), Stephanos Nomismatikos.<br />

Edith Schönert–Geiss zum 65. Geburtstag (Griechisches Münzwerk;<br />

Berlin 1998), pp. 417-39.<br />

Lorber 1990 C.C. Lorber, Amphipolis. The Civic Coinage in Silver <strong>and</strong> Gold (Los<br />

Angeles 1990).<br />

Lorber 2000 C.C. Lorber, ‘A Hoard of Facing Head Larissa Drachms’, RSN 79 (2000),<br />

pp. 7-15.<br />

Lordkipanidze 1985 O. Lordkipanidze, Das alte Kolchis und seine Beziehungen zur<br />

griechischen Welt vom 6. zum 4. Jh. v. Chr. (Xenia. Konstanzer<br />

Althistorische Vorträge und Forschungen 14; Konstanz 1985).<br />

Malakasioti (Volos 1994) Z. Malakasioti, ��������� ��������� ���� ���� ������� ������ ���� ������ ����<br />

������, in ������������������������������������������������������������<br />

���������������������������������������� 1993 (Volos 1994), pp. 47-54.<br />

Marcadé – Croissant 1991 J. Marcadé – Fr. Croissant, ‘La sculpture en pierre’, in Guide de Delphes.<br />

Le Musée (Athens 1991), pp. 42-4.<br />

Martin 1981 T.R. Martin, ‘Diodorus on Philip II <strong>and</strong> Thessaly in the 350s BC’, CPh 76<br />

(1981), pp. 188-201.<br />

Martin 1983 T.R. Martin, ‘The Chronology of the Fourth–Century BC Facing–Head<br />

Silver Coinage of Larissa’, ANSMN 28 (1983), pp. 1-34.<br />

Marzolff 1976 P. Marzolff, ‘Untersuchungen auf der “Heiligen Agora”’, in V. Milojcic –<br />

D. Theocharis (eds), Demetrias I (Bonn 1976), pp. 47-58.<br />

Marzolff 1980 P. Marzolff, in V. Milojcic – D. Theocharis (eds), Demetrias und seine<br />

Halbinsel. Demetrias III (Bonn 1980).<br />

Marzolff 1992 P. Marzolff, ‘Zur Stadtbaugeschichte von Demetrias’, in �����������������<br />

���� ���� ������� ��������� ���� ������ ���� ����� ��������� �������� (Athens<br />

1992), pp. 337-48.<br />

Marzolff 1994 P. Marzolff, ‘Développement urbanistique de Démétrias’, in La Thessalie.<br />

Quinze années de recherches archéologiques 1975-1990. Bilans et<br />

perspectives. Actes du Colloque International Lyon, 17-22 Avril 1990,<br />

Vol. B (Athens 1994), pp. 57-70.<br />

Marzolff (Mainz am Rhein 1996)<br />

P. Marzolff, ‘Der Palast von Demetrias’, in W. Hoepfner – G. Br<strong>and</strong>s<br />

(eds), Basileia. Die Paläste der hellenistischen Könige. Internationales<br />

Symposion in Berlin vom 16.12.1992 bis 20.12.1992 (Mainz am Rhein<br />

1996), pp. 148-63.

IOLKOS AND PAGASAI 39<br />

Marzolff 1996 P. Marzolff, ���������������������������������������������������������������<br />

��������� ���� ������������, in E. Kontaxi (ed.) ������� ������������ ��<br />

��������� ���� ����� ������� ��������� ��������� �� ��������� 1994 (Volos<br />

1996), pp. 47-72.<br />

Masson 1991 O. Masson, ‘Notes de numismatique chypriote IX-X’, RN 1991, pp. 60-<br />

70.<br />

McClean Collection S.W. Grose, Fitzwilliam Museum. Catalogue of the McClean Collection<br />

of Greek Coins, II. The Greek Mainl<strong>and</strong>, the Aegean Isl<strong>and</strong>s, Crete<br />

(Cambridge 1926).<br />

Meyer 1942 E. Meyer, in RE XVIII, 2 (Stuttgart 1942), cols 2297-309, s.v. <strong>Pagasai</strong>.<br />

Morello 1998 A. Morello, Prora Navis. Il potere marittimo di Roma nella monetazione<br />

della Republica. Navi e navigazione nell´ antichità (Formia 1998).<br />

Moustaka 1983 A. Moustaka, Kulte und Mythen auf thessalischen Münzen (Würzburg<br />

1983).<br />

Moustaka 1997 A. Moustaka, ����������������, in K.A. Sheedy – Ch. Papageorgiadou–<br />

Banis (eds), <strong>Numismatic</strong> Archaeology. Archaeological <strong>Numismatic</strong>s.<br />

Proceedings of an International Conference held to Honour Dr. M<strong>and</strong>o<br />

Oeconomides in Athens 1995 (Oxbow Monograph 75; Oxford 1997), pp.<br />

86-95.<br />

<strong>New</strong>ell 1927 E.T. <strong>New</strong>ell, The Coinages of Demetrius Poliorcetes (London 1927).<br />

Papachatzis 1984 N.D. Papachatzis, ������� ���� ������������ ��������� ���� �����������<br />

����������, AE 1984, pp. 130-50.<br />

Papaevangelou – Genakos 2004<br />

Cl. �. Papaevangelou – Genakos, ‘Metrological Aspects of the <strong>Thessalian</strong><br />

Bronze Coinages: The Case of Phalanna’, in ������ 7. Coins in the<br />

<strong>Thessalian</strong> Region. Mints, Circulation, Iconography, History Ancient,<br />

Byzantine, Modern. Proceedings of the Third Scientific Meeting, Volos,<br />

24-27 May 2001 (Athens 2004), pp. 33-50.<br />

Papageorgiou – Steiros – Hourmouziadis 1994<br />

S. Papageorgiou – S. Steiros – G. Hourmouziadis, ��������� ��������<br />

��������������� ���������������� ���������� ���� ��������� ���� �����������<br />

����� ������� ���������, in La Thessalie. Quinze années de recherches<br />

archéologiques 1975-1990. Bilans et perspectives. Actes du Colloque<br />

International Lyon, 17-22 Avril 1990, Vol. A (Athens 1994), pp. 21-8.<br />

Papageorgiou 2003 D. Papageorgiou, ���� �������������� ���� ��� ���������� ������� ����<br />

�������������������, in A. Vlachopoulou – K. Birtacha (eds) ������������<br />

�������������������������������������������� (Athens 2003), pp. 85-98.<br />

Reinders 1988 H.R. Reinders, <strong>New</strong> Halos. A Hellenistic Town in Thessalia, Greece<br />

(Utrecht 1988).<br />

Reinders 2003 H.R. Reinders, ‘Coins’, in H.R. Reinders – W. Prummel (eds) Housing in<br />

<strong>New</strong> Halos, a Hellenistic Town in Thessaly, Greece (Lisse 2003).<br />

Richter 1935 G.M.A. Richter, ‘Jason <strong>and</strong> the Golden Fleece’, AJA 39 (1935), pp. 182-<br />

4.<br />

Rogers 1932 E. Rogers, The Copper Coinage of Thessaly (London 1932).<br />

Sakellariou 1989 M.B. Sakellariou, The Polis–State. Definition <strong>and</strong> Origin<br />

(MELETEMATA 4; Athens 1989).<br />

Schultz 1975 S. Schultz, ‘Bemerkungen zur Artemis Iolkia’, SB 25 (1975), pp. 14-6.<br />

Sestini 1779 D. Sestini, Lettere e Dissertazioni <strong>Numismatic</strong>he sopra alcune medaglie<br />

rare della Collezione Ainslieana III (Livorno 1779).<br />

Severin 1985 T. Severin, The Jason Voyage. The Quest for the Golden Fleece (London<br />

1985).

40<br />

KATERINI LIAMPI<br />

Sordi 1958 M. Sordi, La lega tessala fino ad Alex<strong>and</strong>ro Magno (Roma 1958).<br />

Sprawski 1999 S. Sprawski, Jason of Pherae. A Study on History of Thessaly in Years<br />

431-370 BC (Electrum 3; Cracow 1999).<br />

Stählin 1916 F. Stählin, in RE IX, 2 (Stuttgart 1916), cols 1850-5, s.v. ����������������<br />

Stählin 1924 F. Stählin, Das hellenische Thessalien (Stuttgart 1924, repr. Amsterdam<br />

1967).<br />

Stählin 1928 F. Stählin, in RE XIV, 1 (Stuttgart 1928), cols 459-71, s.v. Magnesia (1).<br />

Stählin – Meyer – Heidner 1934<br />

F. Stählin – E. Meyer – A. Heidner, <strong>Pagasai</strong> und Demetrias (Berlin–<br />

Leipzig 1934).<br />

Stankov 1996 M. Stankov, ‘Eine unedierte Münze aus Apollonia Pontica mit Prora’,<br />

MÖNG 36.2 (1996), pp. 23-8.<br />

Svoronos 1914 J.N. Svoronos, ‘Stylides, ancres hierae, aphlasta, stoloi, acrostolia,<br />

embola, proembola et totems marins’, JIAN 16 (1914), pp. 81-152.<br />

SNG Ashmolean SNG Vol. V Ashmolean Museum Oxford Part II: Italy, Lucania<br />

(Thurium)–Bruttium, Sicily, Carthage (C.H.V. Sutherl<strong>and</strong>) (London<br />

1969).<br />

SNG BM (Black Sea) SNG Vol. IX The British Museum. Part 1: The Black Sea (M.J. Price)<br />

(Oxford 1993).<br />

SNG München (Makedonien: Könige)<br />

SNG Staatliche Münzsammlung München 1./11. Heft Makedonien:<br />

Könige Nr. 1-1228 (K. Liampi) (Munich 2001).<br />

Themelis (-) P. Themelis, Brauron. Guide to the Site <strong>and</strong> Museum (-).<br />

Voegtli 1977 H. Voegtli, Bilder der Heldenepen in der kaiserzeitlichen griechischen<br />

�ünzprägung (Basel 1977).<br />

Warren 1961 J.A.W. Warren, ‘<strong>Two</strong> Notes on <strong>Thessalian</strong> Coins’, NC 1961, pp. 1-5.<br />

Wartenberg 1994 U. Wartenberg, ‘The History <strong>and</strong> Coinage of Alex<strong>and</strong>er of Pherae’, in<br />

�������, Vol. II. ��������� ��� ���������� �������������������������<br />

����������������������� 1992 (Athens 1994), pp. 151-6.<br />

Weber L. Forrer, The Weber Collection Vol. II Greek Coins. Macedon–Thrace–<br />

Thessaly. North Western, Central <strong>and</strong> Southern Greece (London 1924).<br />

Winterthur H. Bloesch, Griechische Münzen in Winterthur, 1. Spanien, Gallien,<br />

Italien, Moesien, Dakien, Sarmatien, Thrakien, Makedonien, Hellas,<br />

Inseln (Winterthur 1987).

1a 1b 1c 2a 2b<br />

3<br />

1c<br />

(enlarged)<br />

2a (enlarged)<br />

3<br />

(enlarged)<br />

LIAMPI, IOLKOS AND PAGASAI<br />

PLATE 3