Adherence to Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Bundle and ...

Adherence to Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Bundle and ...

Adherence to Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Bundle and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PAPER<br />

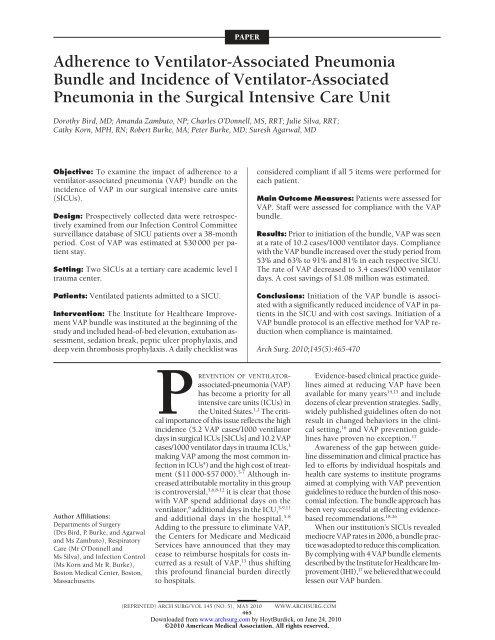

<strong>Adherence</strong> <strong>to</strong> Ventila<strong>to</strong>r-<strong>Associated</strong> <strong>Pneumonia</strong><br />

<strong>Bundle</strong> <strong>and</strong> Incidence of Ventila<strong>to</strong>r-<strong>Associated</strong><br />

<strong>Pneumonia</strong> in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit<br />

Dorothy Bird, MD; Am<strong>and</strong>a Zambu<strong>to</strong>, NP; Charles O’Donnell, MS, RRT; Julie Silva, RRT;<br />

Cathy Korn, MPH, RN; Robert Burke, MA; Peter Burke, MD; Suresh Agarwal, MD<br />

Objective: To examine the impact of adherence <strong>to</strong> a<br />

ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia (VAP) bundle on the<br />

incidence of VAP in our surgical intensive care units<br />

(SICUs).<br />

Design: Prospectively collected data were retrospectively<br />

examined from our Infection Control Committee<br />

surveillance database of SICU patients over a 38-month<br />

period. Cost of VAP was estimated at $30 000 per patient<br />

stay.<br />

Setting: Two SICUs at a tertiary care academic level I<br />

trauma center.<br />

Patients: Ventilated patients admitted <strong>to</strong> a SICU.<br />

Intervention: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement<br />

VAP bundle was instituted at the beginning of the<br />

study <strong>and</strong> included head-of-bed elevation, extubation assessment,<br />

sedation break, peptic ulcer prophylaxis, <strong>and</strong><br />

deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. A daily checklist was<br />

Author Affiliations:<br />

Departments of Surgery<br />

(Drs Bird, P. Burke, <strong>and</strong> Agarwal<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ms Zambu<strong>to</strong>), Respira<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

Care (Mr O’Donnell <strong>and</strong><br />

Ms Silva), <strong>and</strong> Infection Control<br />

(Ms Korn <strong>and</strong> Mr R. Burke),<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Medical Center, Bos<strong>to</strong>n,<br />

Massachusetts.<br />

PREVENTION OF VENTILATORassociated-pneumonia<br />

(VAP)<br />

has become a priority for all<br />

intensive care units (ICUs) in<br />

the United States. 1,2 The critical<br />

importance of this issue reflects the high<br />

incidence (5.2 VAP cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r<br />

days in surgical ICUs [SICUs] <strong>and</strong> 10.2 VAP<br />

cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days in trauma ICUs, 3<br />

making VAP among the most common infection<br />

in ICUs 4 ) <strong>and</strong> the high cost of treatment<br />

($11 000-$57 000). 5-7 Although increased<br />

attributable mortality in this group<br />

is controversial, 5,6,8-12 it is clear that those<br />

with VAP spend additional days on the<br />

ventila<strong>to</strong>r, 6 additional days in the ICU, 5-9,11<br />

<strong>and</strong> additional days in the hospital. 5-8<br />

Adding <strong>to</strong> the pressure <strong>to</strong> eliminate VAP,<br />

the Centers for Medicare <strong>and</strong> Medicaid<br />

Services have announced that they may<br />

cease <strong>to</strong> reimburse hospitals for costs incurred<br />

as a result of VAP, 13 thus shifting<br />

this profound financial burden directly<br />

<strong>to</strong> hospitals.<br />

considered compliant if all 5 items were performed for<br />

each patient.<br />

Main Outcome Measures: Patients were assessed for<br />

VAP. Staff were assessed for compliance with the VAP<br />

bundle.<br />

Results: Prior <strong>to</strong> initiation of the bundle, VAP was seen<br />

at a rate of 10.2 cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days. Compliance<br />

with the VAP bundle increased over the study period from<br />

53% <strong>and</strong> 63% <strong>to</strong> 91% <strong>and</strong> 81% in each respective SICU.<br />

The rate of VAP decreased <strong>to</strong> 3.4 cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r<br />

days. A cost savings of $1.08 million was estimated.<br />

Conclusions: Initiation of the VAP bundle is associated<br />

with a significantly reduced incidence of VAP in patients<br />

in the SICU <strong>and</strong> with cost savings. Initiation of a<br />

VAP bundle pro<strong>to</strong>col is an effective method for VAP reduction<br />

when compliance is maintained.<br />

Arch Surg. 2010;145(5):465-470<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

465<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines<br />

aimed at reducing VAP have been<br />

available for many years 14,15 <strong>and</strong> include<br />

dozens of clear prevention strategies. Sadly,<br />

widely published guidelines often do not<br />

result in changed behaviors in the clinical<br />

setting, 16 <strong>and</strong> VAP prevention guidelines<br />

have proven no exception. 17<br />

Awareness of the gap between guideline<br />

dissemination <strong>and</strong> clinical practice has<br />

led <strong>to</strong> efforts by individual hospitals <strong>and</strong><br />

health care systems <strong>to</strong> institute programs<br />

aimed at complying with VAP prevention<br />

guidelines <strong>to</strong> reduce the burden of this nosocomial<br />

infection. The bundle approach has<br />

been very successful at effecting evidencebased<br />

recommendations. 18-26<br />

When our institution’s SICUs revealed<br />

mediocre VAP rates in 2006, a bundle practicewasadopted<strong>to</strong>reducethiscomplication.<br />

By complying with 4 VAP bundle elements<br />

describedbytheInstituteforHealthcareImprovement(IHI),<br />

17 webelievedthatwecould<br />

lessen our VAP burden.

Compliance, %<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

TICU<br />

SICU<br />

2007 2008 2009<br />

Year<br />

Figure 1. Summary of <strong>to</strong>tal ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia bundle<br />

compliance in 2 surgical intensive care units (SICUs) between January 1,<br />

2007, <strong>and</strong> April 30, 2009. TICU indicates trauma intensive care unit.<br />

METHODS<br />

SETTING<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Medical Center is a 626-bed urban academic tertiary care<br />

center with a level I trauma designation. Our 2 SICUs include<br />

a closed 12-bed trauma/general surgery ICU (TICU) <strong>and</strong> an open<br />

16-bed surgical ICU where patients are admitted from general<br />

<strong>and</strong> subspecialty surgery services (SICU). Combined, our ICUs<br />

admit approximately 1600 critically ill patients annually.<br />

Daily assessment of bundle goals <strong>and</strong> order entry were performed<br />

by a multidisciplinary team including physicians, nurse<br />

practitioners, bedside SICU nurses, <strong>and</strong> pharmacists. Bedside SICU<br />

nurses were responsible for head-of-bed (HOB) elevation <strong>and</strong> for<br />

providing daily sedation breaks based on the Riker score.<br />

DESIGN<br />

Our VAP bundle initiative was assessed through retrospective<br />

review of prospectively collected data from infection control<br />

<strong>and</strong> trauma databases. The study period began March 1, 2006,<br />

when data on VAP incidence were collected prior <strong>to</strong> bundle initiation<br />

<strong>and</strong> includes data collected through May 31, 2009.<br />

The VAP bundle program began Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 1, 2006. Compliance<br />

data were collected from then until May 31, 2009, a 31month<br />

period. Data were grouped by fiscal <strong>and</strong> calendar years.<br />

This study was performed using public databases <strong>and</strong> did<br />

not require institutional review board approval.<br />

VAP BUNDLE<br />

The VAP bundle adopted at our institution differed from the<br />

IHI bundle in that we teased apart “daily sedation vacations <strong>and</strong><br />

assessment of readiness <strong>to</strong> extubate” in<strong>to</strong> 2 individual components.<br />

Our bundle components were as follows: (1) HOB elevation<br />

greater than 30°, (2) daily sedation break, (3) daily assessment<br />

for extubation, (4) peptic ulcer prophylaxis, <strong>and</strong> (5)<br />

deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.<br />

Compliance was assessed twice daily by the respira<strong>to</strong>ry care<br />

service, who entered data in<strong>to</strong> an electronic database. Compliance<br />

was recorded as yes or no for each bundle item. The entire<br />

bundle was considered compliant only if all 5 items were<br />

compliant. A bundle was considered noncompliant if any item<br />

was not performed, even if that item was contraindicated. The<br />

only exception was contraindication <strong>to</strong> deep vein thrombosis<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

466<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

prophylaxis in patients with head injury; the bundle was still<br />

considered compliant in this case.<br />

Compliance data were summarized on a weekly basis. These<br />

data were reviewed monthly by a multidisciplinary team including<br />

intensive care nursing managers who supplied feedback<br />

<strong>to</strong> the SICU nursing staff.<br />

OUTCOME MEASURES<br />

The primary outcome measure was the relationship between<br />

VAP bundle compliance <strong>and</strong> VAP incidence. Cases of VAP were<br />

identified by the infection control team during routine daily<br />

surveillance rounds through the ICUs using Centers for Disease<br />

Control <strong>and</strong> Prevention criteria. 27 All suspected VAP cases<br />

were reviewed thoroughly, including individual radiographs by<br />

the infection control team of nurses <strong>and</strong> physicians before a<br />

VAP diagnosis was confirmed. The members of the infection<br />

control team did not change during the study period.<br />

RatesofVAPweredefinedasthenumberofVAPcasesper1000<br />

ventila<strong>to</strong>r days. Ventila<strong>to</strong>r days were counted daily by the infection<br />

control team. A ventila<strong>to</strong>r day was defined as a calendar day<br />

for which the patient was charged for mechanical ventilation.<br />

A secondary outcome of interest was the cost savings resulting<br />

from the VAP bundle program. At our institution, the<br />

cost <strong>to</strong> treat a VAP case was estimated <strong>to</strong> be $30 000 based on<br />

average costs documented in the literature. 5-7<br />

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS<br />

Differences in VAP rates were compared using the � 2 test. Summary<br />

statistics are provided as annual VAP rate (VAP cases per<br />

1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days) with P value. Annual percentage of compliance<br />

was compared via 95% confidence intervals.<br />

RESULTS<br />

COMPLIANCE MEASURES<br />

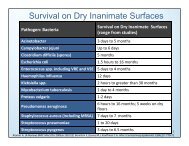

Total bundle compliance increased every year in both<br />

SICUs throughout the study (Figure 1), from 53% <strong>to</strong><br />

91% in the TICU <strong>and</strong> from 63% <strong>to</strong> 81% in the SICU. The<br />

TICU showed the greatest increase in <strong>to</strong>tal compliance.<br />

Both ICUs showed greater improvement in overall compliance<br />

between the first <strong>and</strong> second years of the study<br />

than between the second <strong>and</strong> third years of the study.<br />

Individual bundle items also showed improvement during<br />

the study period (Table). The HOB elevation <strong>and</strong> deep<br />

vein thrombosis prophylaxis bundle elements were initially<br />

the most deficient, but they improved greatly by<br />

the end of the study. Compliance with peptic ulcer prophylaxis,<br />

sedation break, <strong>and</strong> assessment for extubation<br />

were initially excellent <strong>and</strong> remained at or higher than<br />

92% throughout the study.<br />

VAP MEASURES<br />

The overall VAP rates in our 2 ICUs were similar prior<br />

<strong>to</strong> the bundle program (Figure 2) <strong>and</strong> were comparable<br />

<strong>to</strong> the 50th percentile reported by the 2004 National<br />

Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System 28 for<br />

SICUs <strong>and</strong> TICUs.<br />

The incidence of VAP decreased in each ICU during<br />

the study period. The TICU had a greater <strong>and</strong> more statistically<br />

significant reduction in VAP compared with the

Table. Ventila<strong>to</strong>r-<strong>Associated</strong> <strong>Pneumonia</strong> <strong>Bundle</strong> Compliance<br />

SICU, which only approached statistical significance. The<br />

VAP incidence at the SICU increased slightly during the<br />

first year of the VAP bundle program but showed the greatest<br />

decrease during the second year. The TICU saw the<br />

greatest decrease in VAP during the third study year.<br />

Combined VAP rates decreased during the study period<br />

<strong>and</strong> were statistically significant in 2008 <strong>and</strong> 2009<br />

(Figure 2). This suggests a 67% risk reduction by the end<br />

of the study period.<br />

COST ANALYSIS<br />

The combined VAP incidence in our ICUs was 10.2 VAP<br />

cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days at the beginning of the study<br />

period. At that rate, 36 additional VAP cases would have<br />

been acquired by our patients during the study without<br />

the bundle. At an estimated expense of $30 000 (±$20 000)/<br />

VAP case, $1 080 000 ($360 000-$1 800 000) was saved<br />

as a result of VAP prevention.<br />

COMMENT<br />

Our data show a correlation between VAP bundle compliance<br />

<strong>and</strong> reduction in VAP incidence. This effect was<br />

seen across 2 separate SICUs at our institution, it was sustained<br />

for 3 years, <strong>and</strong> it saw our VAP incidence decrease<br />

between the 10th <strong>and</strong> 25th national percentiles for<br />

SICUs <strong>and</strong> TICUs by the end of the study period. Prior<br />

<strong>to</strong> initiation of the VAP bundle, the VAP incidence was<br />

slightly higher at the TICU than at the SICU. We attribute<br />

this <strong>to</strong> the trauma population treated at the TICU<br />

<strong>and</strong> their higher risk of VAP. Overall compliance was proportional<br />

<strong>to</strong> the decrease in the VAP rate. The TICU experienced<br />

a higher level of compliance <strong>and</strong> a lower VAP<br />

rate at the end of 3 years than the SICU. This was likely<br />

because the VAP bundle project was initiated by TICU<br />

staff, although this does not explain why the first year<br />

saw better compliance at the SICU.<br />

Of the individual bundle elements, compliance with<br />

HOB elevation had the greatest impact on VAP reduction.<br />

Compliance with HOB elevation was initially very<br />

low in both ICUs but had the greatest improvement during<br />

the study period. Deep vein thrombolysis prophylaxis<br />

compliance, also initially poor, improved but does<br />

not contribute <strong>to</strong> VAP reduction. Other bundle elements<br />

had excellent compliance throughout the study<br />

Mean Compliance, % (95% CI)<br />

2007 2008 2009<br />

<strong>Bundle</strong> Item<br />

SICU TICU SICU TICU SICU TICU<br />

DVT prophylaxis 83 (77-88) 78 (73-84) 96 (94-98) 98 (97-99) 96 (91-100) 100 (100)<br />

HOB elevation 77 (73-82) 65 (57-72) 84 (80-89) 90 (86-93) 85 (77-94) 99 (98-100)<br />

Peptic ulcer prophylaxis 98 (96-99) 99 (98-100) 99 (98-100) 98 (97-99) 100 (99-100) 100 (99-100)<br />

Sedation break 98 (97-99) 97 (96-99) 97 (96-98) 99 (98-100) 95 (89-100) 98 (95-100)<br />

Assessment for extubation 96 (94-98) 92 (87-97) 97 (95-98) 97 (96-99) 99 (98-100) 94 (88-99)<br />

Total bundle compliance 63 (57-69) 53 (46-60) 78 (73-83) 85 (82-89) 81 (72-90) 91 (85-97)<br />

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HOB, head-of-bed; SICU, surgical intensive care unit; TICU, trauma intensive care unit.<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

467<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

Annual VAP Cases/1000 Ventila<strong>to</strong>r Days, No.<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

2006 2007 2008 2009<br />

Year<br />

Total<br />

TICU<br />

SICU<br />

Figure 2. Summary of annual ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia (VAP) cases<br />

in 2 surgical intensive care units (SICUs) between March 1, 2006, <strong>and</strong> April<br />

30, 2009. TICU indicates trauma intensive care unit. *P=.01; †P=.06; <strong>and</strong><br />

‡P=.004.<br />

period. Head-of-bed elevation was the single element associated<br />

with reducing VAP risk that improved during<br />

the study period.<br />

Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of nosocomial<br />

pneumonia have been published <strong>and</strong> revised by<br />

the Centers for Disease Control <strong>and</strong> Prevention since the<br />

1980s. 13,14,29,30 Since the publication of these guidelines,<br />

a decrease in the VAP rate has been appreciated by the<br />

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. The<br />

SICU VAP rate was 25 VAP cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days<br />

in 1987 <strong>and</strong> decreased <strong>to</strong> 15 by 1991, 31 <strong>to</strong> 9.3 by 2004, 28<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> 5.2 in 2006. 3<br />

Manangan et al 31 described compliance data obtained<br />

in 1995 via mailed self-report surveys regarding<br />

recommendations for management of ventila<strong>to</strong>r equipment.<br />

This group found that compliance with timing of<br />

breathing circuit change (category 1A recommendation)<br />

had increased from 65% <strong>to</strong> 98% <strong>and</strong> that compliance<br />

with routine changing of the hygroscopic condenser-humidifiers<br />

or heat-moisture exchangers<br />

(category 1B recommendation) increased from 62% <strong>to</strong><br />

93% since guideline publication. Most other recommended<br />

practices were not as well heeded or showed<br />

little change in behavior.<br />

In 1999, Cabana et al 16 reviewed 76 studies that examined<br />

guideline compliance <strong>and</strong> concluded that al-<br />

∗<br />

†<br />

‡<br />

∗

though the guidelines are widely distributed, they have<br />

only a small impact on changing physician practice. Rello<br />

et al 17 confirmed this disappointing reality for VAP guidelines<br />

as well. In this international study, critical care physicians<br />

deemed “opinion leaders” in the field of VAP were<br />

surveyed about evidence-based guidelines described by<br />

Kollef. 14 Rello <strong>and</strong> colleagues discovered a 25.2% noncompliance<br />

rate for recommended guidelines; noncompliance<br />

rates of 41.3% <strong>and</strong> 35.7% were seen for grade A<br />

<strong>and</strong> B recommendations, respectively. While Rello <strong>and</strong><br />

colleagues found “disagreement with interpretation of reported<br />

trials” 17 <strong>and</strong> “lack of resources” 17 <strong>to</strong> be the main<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>rs for noncompliance, Cabana <strong>and</strong> colleagues reported<br />

“lack of awareness, lack of familiarity, lack of selfefficacy,<br />

lack of outcome expectance, <strong>and</strong> inertia of previous<br />

practice” 16 as important barriers <strong>to</strong> implementing<br />

guidelines.<br />

Acknowledgment of widespread guideline noncompliance<br />

led <strong>to</strong> speculation by Sinuff et al 32 in<strong>to</strong> methods for<br />

improving knowledge translation relevant <strong>to</strong> VAP prevention<br />

in ICUs. This group suggested that a multifaceted approach<br />

would yield the greatest success. An active educational<br />

strategy combined with reminders, audit, <strong>and</strong><br />

feedback led by a guidance implementation team was recommended<br />

for further study. Craven 4 similarly advised that<br />

a cure for poor compliance with VAP guidelines should involve<br />

a multidisciplinary team that sets prevention benchmarks,<br />

establishes goals <strong>and</strong> timelines, <strong>and</strong> provides education,<br />

training, audits, <strong>and</strong> feedback.<br />

An enormous amount of effort has been spent overcoming<br />

barriers <strong>to</strong> guideline implementation. The earliest<br />

programs aimed at reducing VAP by complying with<br />

established recommendations were described in the mid-<br />

1990s.<br />

Kelleghan et al 33 described a 1989 quality improvement<br />

project at Kaiser Permanente in California that was<br />

modeled after the principles of continuous quality improvement<br />

described by W. Edwards Deming, PhD. This<br />

is among the earliest attempts at reducing VAP incidence<br />

by enforcing existent infection control <strong>and</strong> prevention<br />

guidelines. With a multipronged approach, a multidisciplinary<br />

infection prevention team established a<br />

checklist of respira<strong>to</strong>ry guidelines for staff, addressed barriers<br />

<strong>to</strong> compliance, instituted a h<strong>and</strong>-washing surveillance<br />

program, held educational seminars, began prospective<br />

VAP surveillance, <strong>and</strong> gave compliance feedback.<br />

This institution had a 57% reduction in VAP in 1 year,<br />

estimating 15 VAP cases prevented, 3 lives saved, <strong>and</strong><br />

$105 000 in cost savings.<br />

Joiner et al 34 described similar efforts in Ohio in 1992.<br />

Also borrowing from continuous quality improvement<br />

theory, which stipulates that outcome improvement stems<br />

from change in process, a multidisciplinary quality improvement<br />

team compared the institution’s process of ventila<strong>to</strong>r<br />

care management with evidence-based best-care<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> created a pro<strong>to</strong>col <strong>to</strong> eliminate the gap between<br />

current <strong>and</strong> best care. The VAP <strong>and</strong> process evaluation<br />

data were collected <strong>and</strong> reviewed monthly, <strong>and</strong> areas<br />

for improvement were addressed. This institution also<br />

saw a dramatic decrease in VAP incidence, from 26 <strong>to</strong><br />

16 VAP cases/1000 ventila<strong>to</strong>r days, saving approximately<br />

$126 000 over 3 years.<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

468<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

The VAP bundle concept grew from the IHI’s 100 000<br />

Lives Campaign <strong>to</strong> reduce VAP incidence. 1 The bundle is<br />

a “small set of evidence-based interventions for patients on<br />

mechanical ventilation.” 18 Created in 2002, the IHIdefined<br />

bundle included 4 elements: HOB elevation, daily<br />

sedation vacation, peptic ulcer prophylaxis, <strong>and</strong> deep vein<br />

thrombosis prophylaxis. Clinical evidence supports that<br />

each item reduces patient mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity 18 <strong>and</strong><br />

that patients on mechanical ventilation should receive these<br />

things, despite the fact that only HOB elevation <strong>and</strong> sedation<br />

vacation reduce VAP risk.<br />

In 2005, Resar et al 19 described the IHI Impact Network’s<br />

experience implementing the IHI VAP bundle at<br />

61 hospitals. The ICUs achieving greater than 95% compliance<br />

saw a 59% reduction in VAP rates. Resar <strong>and</strong> colleagues<br />

emphasized that while bundle use may improve<br />

clinical outcomes, its use would also improve process reliability.<br />

They speculated further that the multidisciplinary<br />

teams, daily goal-setting, <strong>and</strong> increased attention<br />

<strong>to</strong> detail stimulated by the bundle importantly<br />

contributed <strong>to</strong> improved clinical outcomes.<br />

Cocanour et al 21 described VAP bundle use in their<br />

Hous<strong>to</strong>n, Texas, TICU. On discovery of high VAP incidence,<br />

a bundle program that included elements of the<br />

IHI VAP bundle in addition <strong>to</strong> several other precautions<br />

was initiated. The initial improvements in VAP incidence<br />

were modest <strong>and</strong> unsustained. When a computerized<br />

audit <strong>to</strong>ol was implemented <strong>to</strong> calculate weekly<br />

bundle compliance data, the VAP rate decreased below<br />

the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System’s<br />

25th percentile <strong>and</strong> was sustained for the remaining<br />

months of the study. This result reveals the importance<br />

of process quality evaluation <strong>and</strong> feedback in<br />

improving clinical outcome when using a bundle.<br />

A similar experience was described by Hawe et al 20 in<br />

Scotl<strong>and</strong>. They implemented a similar VAP bundle by displaying<br />

copies of the pro<strong>to</strong>col at every ICU bedside. Compliance,<br />

assessed only periodically, was dismal during this<br />

passive implementation phase <strong>and</strong> no VAP reduction was<br />

seen. An active implementation phase that included educational<br />

workshops, compliance reporting, addressing barriers<br />

<strong>to</strong> delivery, <strong>and</strong> discussion of bundle adherence on<br />

daily multidisciplinary rounds was initiated. Compliance<br />

improved from 0% <strong>to</strong> 54% <strong>and</strong> VAP rates decreased<br />

dramatically from 19.17 <strong>to</strong> 7.5 VAP cases/1000<br />

ventila<strong>to</strong>r days. Here, the education, feedback, <strong>and</strong> daily<br />

goal-setting were key <strong>to</strong> clinical success.<br />

Zaydfudim et al 25 made compliance feedback the keys<strong>to</strong>ne<br />

of their VAP bundle program in Nashville, Tennessee.<br />

When implementation of a bundle program with<br />

intermittent compliance moni<strong>to</strong>ring failed <strong>to</strong> reduce VAP<br />

incidence, a real-time VAP bundle compliance dashboard<br />

was installed on every SICU computer moni<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

Daily compliance reports were reviewed by multidisciplinary<br />

rounding teams <strong>and</strong> by physician <strong>and</strong> nursing leaders.<br />

Real-time compliance feedback resulted in an increase<br />

in <strong>to</strong>tal bundle compliance from approximately<br />

20% <strong>to</strong> about 90% over 1 year. Compliance with individual<br />

bundle items increased in every parameter during<br />

the study period, <strong>and</strong> overall VAP rates improved.<br />

We attribute the success of our VAP bundle program<br />

<strong>to</strong> several of the fac<strong>to</strong>rs described earlier. First, we used

a concise, well-established bundle described by the IHI 17,25<br />

where each component has a well-documented impact on<br />

morbidity. 18 Numerous other ICUs in the United States have<br />

had success in decreasing VAP incidence using the IHI<br />

bundle. 17 Second, our comprehensive approach <strong>to</strong> bundle<br />

implementation <strong>and</strong> its incorporation <strong>to</strong> daily rounds <strong>and</strong><br />

goal-setting contributed <strong>to</strong> our success. 18 Daily multidisciplinary<br />

rounds with a checklist by a team including nurses,<br />

pharmacists, <strong>and</strong> physicians ensured that bundleappropriate<br />

orders were entered <strong>and</strong> completed. Our system<br />

of regular audit <strong>and</strong> feedback may have made the greatest<br />

impact on bundle compliance. The VAP compliance <strong>and</strong><br />

incidence data were reviewed weekly, monthly, <strong>and</strong> quarterly.<br />

Weekly data were summarized in an electronic newsletter<br />

that included days since last VAP. Quarterly VAP data<br />

were posted in several locations throughout the hospitals<br />

<strong>and</strong> the ICUs. Nursing supervisors who attended monthly<br />

meetings discussed compliance data, comparing current <strong>and</strong><br />

prior performance, <strong>and</strong> provided feedback <strong>to</strong> the ICU nursing<br />

staff. Presumably once the trend in reduced VAP incidence<br />

became apparent with improved bundle compliance,<br />

the staff became even more motivated <strong>to</strong> improve<br />

performance. These same feedback <strong>and</strong> reminder mechanisms<br />

continue presently.<br />

Strengths of our study include the large number of patients<br />

(approximately 4000) treated in our SICUs over<br />

2 1 ⁄2 years. The similar results achieved at both SICUs underscore<br />

the validity of our results. Another important<br />

strength is the measurement of our primary outcome (VAP<br />

incidence) by an experienced, unchanging infection control<br />

team.<br />

Among the weaknesses of this study, we did not compare<br />

our SICU populations between units or years. It is<br />

possible that healthier patients with fewer risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs for<br />

VAP were admitted in 2009 than in 2006. We did not<br />

account for contraindications <strong>to</strong> VAP bundle items when<br />

scoring compliance. This may have led <strong>to</strong> underestimation<br />

of actual guideline compliance. Finally, the greatest<br />

weakness of our study is that it does not account for<br />

other ongoing programs at out institution aimed at reducing<br />

nosocomial infections, including a h<strong>and</strong>washing<br />

campaign, blood glucose control pro<strong>to</strong>cols, a<br />

chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash pro<strong>to</strong>col, <strong>and</strong> availability<br />

of an endotracheal tube that supports continuous<br />

aspiration of subglottic secretions. While we have<br />

documented improved compliance with h<strong>and</strong> washing,<br />

which may have had an impact on our VAP rates, compliance<br />

data are not available for the other interventions. Use<br />

of chlorhexidine mouthwash <strong>and</strong> of the endotracheal tube<br />

that supports continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions<br />

began in 2005 at our institution, 1 year prior <strong>to</strong> initiation<br />

of the bundle program.<br />

In summary, our study demonstrates the success of a<br />

VAP bundle in reducing the incidence of VAP <strong>and</strong> in cutting<br />

costs in 2 SICUs when excellent compliance is maintained.<br />

Compliance was achieved by incorporating the<br />

bundle in<strong>to</strong> daily multidisciplinary rounds <strong>and</strong> through<br />

regular audit <strong>and</strong> feedback. This is a simple, inexpensive,<br />

effective method of reducing VAP in the SICU.<br />

Accepted for Publication: November 12, 2009.<br />

Correspondence: Dorothy Bird, MD, Department of Sur-<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

469<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

gery, Bos<strong>to</strong>n Medical Center, 88 E New<strong>to</strong>n St, Bos<strong>to</strong>n,<br />

MA 02118 (dorothy.bird@bmc.org).<br />

Author Contributions: Study concept <strong>and</strong> design: Zambu<strong>to</strong>,<br />

O’Donnell, <strong>and</strong> Agarwal. Acquisition of data:<br />

O’Donnell, Silva, Korn, <strong>and</strong> R. Burke. Analysis <strong>and</strong> interpretation<br />

of data: Bird, O’Donnell, R. Burke, P. Burke, <strong>and</strong><br />

Agarwal. Drafting of the manuscript: Bird. Critical revision<br />

of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Bird,<br />

Zambu<strong>to</strong>, O’Donnell, Silva, Korn, R. Burke, P. Burke, <strong>and</strong><br />

Agarwal. Statistical analysis: Bird. Administrative, technical,<br />

<strong>and</strong> material support: Zambu<strong>to</strong>, O’Donnell, Silva, Korn,<br />

R. Burke, <strong>and</strong> Agarwal. Study supervision: P. Burke <strong>and</strong><br />

Agarwal.<br />

Financial Disclosure: None reported.<br />

Previous Presentation: This paper was presented at the<br />

90th Annual Meeting of the New Engl<strong>and</strong> Surgical Society;<br />

September 11, 2009; Newport, Rhode Isl<strong>and</strong>; <strong>and</strong><br />

is published after peer review <strong>and</strong> revision.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Berwick DM, Calkins DR, McCannon CJ, Hackbarth AD. The 100 000 Lives Campaign:<br />

setting a goal <strong>and</strong> a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA. 2006;<br />

295(3):324-327.<br />

2. Chinsky KD. Ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia: is there any gold in these st<strong>and</strong>ards?<br />

Chest. 2002;122(6):1883-1885.<br />

3. Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Andrus ML, et al; NHSN Facilities. National Healthcare<br />

Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2006, issued June 2007.<br />

Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(5):290-301.<br />

4. Craven DE. Preventing ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia in adults: sowing seeds<br />

of change. Chest. 2006;130(1):251-260.<br />

5. Warren DK, Shukla SJ, Olsen MA, et al. Outcome <strong>and</strong> attributable cost of ventila<strong>to</strong>rassociated<br />

pneumonia among intensive care unit patients in a suburban medical<br />

center. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1312-1317.<br />

6. Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, et al; VAP Outcomes Scientific Advisory Group.<br />

Epidemiology <strong>and</strong> outcomes of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia in a large US<br />

database. Chest. 2002;122(6):2115-2121.<br />

7. Cocanour CS, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Peninger M, et al. Cost of a ventila<strong>to</strong>rassociated<br />

pneumonia in a shock-trauma intensive care unit. Surg Infect (Larchmt).<br />

2005;6(1):65-72.<br />

8. Fagon JY, Chastre J, Hance AJ, Montravers P, Novara A, Gibert C. Nosocomial<br />

pneumonia in ventilated patients: a cohort study evaluating attributable mortality<br />

<strong>and</strong> hospital stay. Am J Med. 1993;94(3):281-288.<br />

9. Ibrahim EH, Tracy L, Hill C, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The occurrence of ventila<strong>to</strong>rassociated<br />

pneumonia in a community hospital: risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> clinical outcomes.<br />

Chest. 2001;120(2):555-561.<br />

10. Heyl<strong>and</strong> DK, Cook DJ, Griffith L, Keenan SP, Brun-Buisson C; Canadian Critical<br />

Trials Group. The attributable morbidity <strong>and</strong> mortality of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated<br />

pneumonia in the critically ill patient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159<br />

(4, pt 1):1249-1256.<br />

11. Rello J, Quintana E, Ausina V, et al. Incidence, etiology, <strong>and</strong> outcome of nosocomial<br />

pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest. 1991;100(2):<br />

439-444.<br />

12. Cook D. Ventila<strong>to</strong>r associated pneumonia: perspectives on the burden of illness.<br />

Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(suppl 1):S31-S37.<br />

13. Centers for Medicare <strong>and</strong> Medicaid Services. CMS proposes <strong>to</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> quality<br />

program for hospital inpatient services in FY 2009 [press release, April 14, 2008].<br />

http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=3041&intNum<br />

PerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=<br />

0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=1%2C+2%2C+3%2C+4<br />

%2C+5&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=false&cboOrder=date. Accessed<br />

August 13, 2009.<br />

14. Kollef MH. The prevention of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia. N Engl J Med.<br />

1999;340(8):627-634.<br />

15. Muscedere J, Dodek P, Keenan S, Fowler R, Cook D, Heyl<strong>and</strong> D; VAP Guidelines<br />

Committee <strong>and</strong> the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Comprehensive evidencebased<br />

clinical practice guidelines for ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia: prevention.<br />

J Crit Care. 2008;23(1):126-137.<br />

16. Cabana MD, R<strong>and</strong> CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice<br />

guidelines? a framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465.

17. Rello J, Lorente C, Bodi M, Diaz E, Ricart M, Kollef MH. Why do physicians not<br />

follow evidence-based guidelines for preventing ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia?<br />

a survey based on the opinions of an international panel of intensivists. Chest.<br />

2002;122(2):656-661.<br />

18. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Implement the ventila<strong>to</strong>r bundle. http://www<br />

.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/Changes/ImplementtheVentila<strong>to</strong>r<strong>Bundle</strong><br />

.htm. Accessed Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 8, 2009.<br />

19. Resar R, Pronovost P, Haraden C, Simmonds T, Rainey T, Nolan T. Using a bundle<br />

approach <strong>to</strong> improve ventila<strong>to</strong>r care processes <strong>and</strong> reduce ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated<br />

pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(5):243-248.<br />

20. Hawe CS, Ellis KS, Cairns CJ, Longmate A. Reduction of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated<br />

pneumonia: active vs passive guideline implementation. Intensive Care Med. 2009;<br />

35(7):1180-1186.<br />

21. Cocanour CS, Peninger M, Domonoske BD, et al. Decreasing ventila<strong>to</strong>rassociated<br />

pneumonia in a trauma ICU. J Trauma. 2006;61(1):122-130.<br />

22. Tolentino-DelosReyes AF, Ruppert SD, Shiao SY. Evidence-based practice: use<br />

of the ventila<strong>to</strong>r bundle <strong>to</strong> prevent ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia. AmJCrit<br />

Care. 2007;16(1):20-27.<br />

23. Lansford T, Moncure M, Carl<strong>to</strong>n E, et al. Efficacy of a pneumonia prevention pro<strong>to</strong>col<br />

in the reduction of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia in trauma patients. Surg<br />

Infect (Larchmt). 2007;8(5):505-510.<br />

24. Papadimos TJ, Hensley SJ, Duggan JM, et al. Implementation of the “FASTHUG”<br />

concept decreases the incidence of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia in a surgical<br />

intensive care unit. Patient Saf Surg. 2008;2:3.<br />

25. Zaydfudim V, Dossett LA, Starmer JM, et al. Implementation of a real-time compliance<br />

dashboard <strong>to</strong> help reduce SICU ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia with the<br />

ventila<strong>to</strong>r bundle. Arch Surg. 2009;144(7):656-662.<br />

26. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Raising the bar<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 5), MAY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM<br />

470<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archsurg.com by HoytBurdick, on June 24, 2010<br />

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.<br />

with bundles: treating patients with an all-or-nothing st<strong>and</strong>ard. Jt Comm Perspectives<br />

on Patient Saf. 2006;6(4):5-6.<br />

27. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health<br />

care-associated infection <strong>and</strong> criteria for specific types of infections in the acute<br />

care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(5):309-332.<br />

28. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections<br />

Surveillance (NNIS) System report, data summary from January 1992<br />

through June 2004, issued Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(8):<br />

470-485.<br />

29. Simmons BP, Wong ES. Guideline for prevention of nosocomial pneumonia. Am<br />

J Infect Control. 1983;11(6):230-244.<br />

30. Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Arden NH, Breiman RF, Butler JC, McNeil MM; Hospital<br />

Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Centers for Disease Control<br />

<strong>and</strong> Prevention. Guideline for prevention of nosocomial pneumonia. Am J Infect<br />

Control. 1994;22(4):247-292.<br />

31. Manangan LP, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Association between implementation of<br />

CDC recommendations <strong>and</strong> ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia at selected US<br />

hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28(3):222-227.<br />

32. Sinuff T, Muscedere J, Cook D, Dodek P, Heyl<strong>and</strong> D; Canadian Critical Care Trials<br />

Group. Ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia: improving outcomes through guideline<br />

implementation. J Crit Care. 2008;23(1):118-125.<br />

33. Kelleghan SI, Salemi C, Padilla S, et al. An effective continuous quality improvement<br />

approach <strong>to</strong> the prevention of ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia. AmJInfect<br />

Control. 1993;21(6):322-330.<br />

34. Joiner GA, Salisbury D, Bollin GE. Utilizing quality assurance as a <strong>to</strong>ol for reducing<br />

the risk of nosocomial ventila<strong>to</strong>r-associated pneumonia. Am J Med Qual. 1996;<br />

11(2):100-103.