contents - National Institute of Rural Development

contents - National Institute of Rural Development

contents - National Institute of Rural Development

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Vol. 31 April - June 2012 No. 2<br />

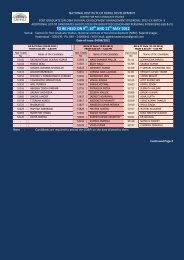

CONTENTS<br />

1. Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam<br />

– Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

139<br />

2. Institutional Arrangements for Farmland <strong>Development</strong> : The Case <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia<br />

– Abayineh Amare Woldeamanuel, Fekadu, Beyene Kenee<br />

151<br />

3. Employment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> Women In Sericulture - An Empirical Analysis<br />

– S. Lakshmanan<br />

163<br />

4. India’s Total Sanitation Campaign : Is it on the Right Track?<br />

Progress and Issues <strong>of</strong> TSC in Andhra Pradesh<br />

– M. Snehalatha, V. Anitha<br />

173<br />

5. Political Inclusion and Participation <strong>of</strong> Women in<br />

Local Governance : A Study in Karnataka<br />

– N. Sivanna, K.G. Gayathridevi<br />

193<br />

6. Risk Management and <strong>Rural</strong> Employment in Hill Farming -<br />

A Study <strong>of</strong> Mandi District <strong>of</strong> Himachal Pradesh<br />

– Vinod Kumar, R.K. Sharma , K.D. Sharma<br />

211<br />

7. Impact <strong>of</strong> Micro-finance on Poverty : A Study <strong>of</strong> Twenty<br />

Self-Help Groups in Nalbari District, Assam<br />

– Prasenjit Bujar Baruah<br />

223<br />

8. Capacity Building through Women Groups<br />

– Santhosh Kumar S.<br />

245

BOOK REVIEWS<br />

1. Social Relevance <strong>of</strong> Higher Learning Institutions<br />

by G. Palanithurai<br />

– Dr. S.M. Ilyas<br />

245<br />

2. Economic Liberalisation and Indian Agriculture : A District Level Study<br />

by Bhalla, G.S. and Gurmail Singh<br />

– Dr. V. Suresh Babu<br />

246<br />

3. Horticulture for Tribal <strong>Development</strong><br />

by R.N. Hegde and S.D. Suryawanshi<br />

– Dr. V. Suresh Babu<br />

247<br />

4. Women Empowerment through Literacy Campaign : Role <strong>of</strong> Social Work<br />

by Jaimon Varghese<br />

– Dr. G. Valentina<br />

248<br />

5. <strong>Development</strong> <strong>of</strong> Special Economic Zones in India<br />

Edited by M. Soundarapandian<br />

– Dr. C. Dheeraja<br />

249<br />

6. Bureaucracy and <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in Mizoram<br />

by Harendra Sinha<br />

– Pradip Kumar Nath<br />

251<br />

7. <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Administration in India<br />

by N.Sreeramulu<br />

– Dr. R. Murugesan<br />

253<br />

8. Land Policies for Inclusive Growth<br />

Edited by T. Haque<br />

– Dr. Ch. Radhika Rani<br />

254

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. (2) pp. 139 - 150<br />

NIRD, Hyderabad.<br />

FACTORS INFLUENCING WAGE<br />

STRUCTURE OF HANDLOOM<br />

WORKERS IN ASSAM<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Alin Borah Bortamuly,<br />

Kishor Goswami *<br />

The removal <strong>of</strong> import quota restriction for textile products opened up new<br />

avenues and challenges for the Indian handloom industry, which infused competition<br />

in recent years. As majority <strong>of</strong> the workers in the industry are women, who work mostly<br />

as weavers, reelers and helpers, such competition <strong>of</strong>ten influences the nature and<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> earnings <strong>of</strong> women workers. Therefore, the present study attempts to<br />

analyse the factors influencing the wage structure <strong>of</strong> the handloom industry from a<br />

gender perspective. It examines the wage differential with respect to gender as well<br />

as type <strong>of</strong> work the workers are entrusted with. The study is based on primary data<br />

collected from 300 respondents in 13 districts in Assam. Multiple regression technique<br />

is used to analyse the data. The results show that in case <strong>of</strong> contractual workers, there<br />

is no gender discrimination in wages, whereas it is found in case <strong>of</strong> monthly rated<br />

workers. Productivity <strong>of</strong> the workers is found to be significant both for monthly rated<br />

as well as contractual workers. Factors like education and experience do not have any<br />

significant influence on the wage structure <strong>of</strong> the workers in the handloom industry<br />

in Assam. Thus, the government machinery should address the gender wage<br />

discrimination for monthly rated weavers and reelers, and back up support facilities<br />

for contractual workers <strong>of</strong> the industry in the State. The present study greatly extends<br />

our understanding <strong>of</strong> the wage earnings scenario in Assam’s handloom sector from<br />

gender perspective.<br />

Introduction<br />

The removal <strong>of</strong> trade restrictions in<br />

textile sector from January 1, 2005 infused<br />

more competition among countries such as<br />

China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Sri Lanka and<br />

others. These countries were initially affected<br />

by Cotton Textile Agreement (CTA) and<br />

thereafter by the Multi- Fibre Agreement (MFA)<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1974 and the Agreement on Textile and<br />

Clothing (ATC) <strong>of</strong> 1994. However, removal <strong>of</strong><br />

such restrictions infused intense competition<br />

among the countries to expand their market<br />

share. As a result, the Indian handloom industry<br />

which is a part <strong>of</strong> the textile industry had to<br />

face severe competition. As majority <strong>of</strong> the<br />

workers in the industry are women, who work<br />

mostly as weavers, reelers, and helpers, such<br />

competition <strong>of</strong>ten influences the nature and<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> earnings <strong>of</strong> women workers more.<br />

The industry is beset with manifold problems<br />

such as obsolete technology, unorganised<br />

production system, low productivity,<br />

inadequate working capital, conventional<br />

* Department <strong>of</strong> Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> Technology, Kharagpur,<br />

West Bengal -721302, E-mail: kishor@hss.iitkgp.ernet.in

140 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

product range, weak marketing link, overall<br />

stagnation <strong>of</strong> production and sales, and above<br />

all competition from powerloom and mill<br />

sector (Sudalaimuthu and Devi, 2006). Women<br />

in the industry share enormous work burden<br />

with no commensurate compensation system.<br />

Their living and working conditions are a<br />

serious concern in many parts <strong>of</strong> India.<br />

Whenever the industry is in crisis, the burden<br />

<strong>of</strong> carrying through the crisis is mostly on<br />

women weavers. Such burdens increase their<br />

physical, psychological and social stress<br />

(Reddy, 2006). Women weavers have been the<br />

principal stabilisation force through years <strong>of</strong><br />

crises and problems for the handloom sector.<br />

The pattern <strong>of</strong> employment has seen a<br />

remarkable change worldwide after<br />

globalisation. For example, the employment<br />

in UK is increasingly taking a variety <strong>of</strong> work<br />

time, benefits and entitlements are put<br />

together for different groups <strong>of</strong> workers. The<br />

growth in sub-contracting and the<br />

rationalisation <strong>of</strong> ‘marginal’ activities by firms<br />

and public agencies produced a situation in<br />

which many workers, previously in secure jobs,<br />

now face regular employment on a more<br />

precarious contract labour basis (Allen and<br />

Henry, 2001). Standing (1992) referred to this<br />

trend as the growing ‘contractualisation’ <strong>of</strong><br />

employment. In a similar manner, in India too,<br />

there has been a clear indication <strong>of</strong> workforce<br />

restructuring in the handloom industry in the<br />

recent years. Analysing the textile and apparel<br />

industry in India, Ramaswamy (2008) found<br />

that those who were regular workers became<br />

contractual workers in a number <strong>of</strong> cases along<br />

with the new hires in the textile industry. In<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> wage differentials in Textile and<br />

Apparel, he found that the relative wage<br />

disparity in Textile and Apparel has not<br />

worsened in the years <strong>of</strong> greater global trade<br />

participation. There was improvement in<br />

relative position <strong>of</strong> female workers; male<br />

workers were getting the same wage rate as<br />

that in average urban informal sector industries.<br />

Other employment benefits have declined as<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

suggested by the growth <strong>of</strong> contractual labour.<br />

Thus, with the removal <strong>of</strong> quota restrictions,<br />

there is a considerable change in the job and<br />

wage pattern. Therefore, the present study<br />

attempts to analyse the factors influencing the<br />

wage structure <strong>of</strong> the handloom industry. It<br />

examines the wage differential with respect<br />

to gender as well as type <strong>of</strong> work the workers<br />

are entrusted with.<br />

Wage Differential and Factors Influencing<br />

Wage Structure<br />

Wage differential reflects discrimination<br />

as well as differences in productivity related<br />

factors such as education, training, and<br />

experience (Bonnie & Harrison, 2005). It may<br />

be the difference in wage between workers<br />

with different skills working in the same<br />

industry, or workers with similar skills working<br />

in different industries or regions. Wage<br />

differential with respect to gender means<br />

whether there is any difference in the wages<br />

<strong>of</strong> male and female workers with respect to<br />

the work they are entrusted with. The<br />

persistence <strong>of</strong> wage differentials between<br />

males and females can be postulated from a<br />

few theoretical standpoints involving both<br />

competitive and non-competitive settings<br />

within the labour market. Traditional human<br />

capital explanations <strong>of</strong> wage differentials<br />

involve two approaches based on free-market<br />

setting. One is the competitive case, where<br />

individual learnings are set according to the<br />

labour market supply and demand interaction<br />

under a flexible wage regime. In this case, the<br />

individual’s ability, skill acquisition,<br />

qualifications possessed, and productivity<br />

levels together influence earnings. Another<br />

approach under the competitive setting is the<br />

efficiency wage effect, where firm sets wages<br />

according to workers’ productivity and <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

common in capital intensive (relatively high<br />

technology) occupations, especially those<br />

involving high skilled labour force (Darity,<br />

1991; Dickens & Katz, 1987).

Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam ... 141<br />

Several studies are conducted<br />

considering the concept <strong>of</strong> gender wage<br />

differential at national and international levels.<br />

Norsworthy (2003) said that women typically<br />

earn lower wages than men for the same job.<br />

Similarly, Berik et al. (2004) found that<br />

competition from foreign trade in<br />

concentrated industries is positively associated<br />

with wage discrimination against women.<br />

Research on rural-urban gender wage gap<br />

shows that, in comparison to urban zones, rural<br />

areas have persistently lower incomes and<br />

higher unemployment and underemployment<br />

rates, especially for women (Stabler, 1999;<br />

Lichter and Costanzo, 1987). Most notably,<br />

women at the lower end <strong>of</strong> the income<br />

distribution suffer the highest degree <strong>of</strong><br />

discrimination (Gerry et al., 2004). Most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

studies which explain and measure the extent<br />

<strong>of</strong> Russia’s gender wage gap since transition<br />

were largely based on the Oaxaca- Blinder<br />

(1973) decomposition in which wage<br />

equations are estimated separately for men<br />

and women in order to allow for different<br />

gender rewards to a set <strong>of</strong> productive<br />

characteristics (Fairlie, 2003). The male –<br />

female wage differential is explained in terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the difference in average endowments<br />

evaluated at the male (female) pay structure<br />

and the difference in returns evaluated at the<br />

female (male) average endowment. Thus, in<br />

the absence <strong>of</strong> discrimination, men and<br />

women will have the same return for similar<br />

endowments, and hence the latter difference<br />

is interpreted as ‘discrimination’ (Gerry et. al.,<br />

2004).<br />

In an exceptional study conducted by<br />

Cobb-Clark and Tan (2011), it was found that<br />

non-cognitive skills have a substantial effect<br />

on the probability <strong>of</strong> employment in many,<br />

though not all, occupations in ways they differ<br />

by gender. Consequently, men and women<br />

with similar non-cognitive skills enter<br />

occupations at different rates. Women,<br />

however, have lower wages on average not<br />

because they work in different occupations<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

than men do, rather they earn less than their<br />

male colleagues employed in the same<br />

occupation. On balance, women’s noncognitive<br />

skills give them a slight wage<br />

advantage. Thus, gender wage gap in particular<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten attributed to gender segregation<br />

across occupations, industries or jobs (Blau and<br />

Kahn, 2000; Groshen, 1991; Mumford and<br />

Smith, 2007). This is because male jobs are<br />

generally associated with higher wages, better<br />

benefits, and more training opportunities.<br />

Occupational segregation may result in an<br />

overall gender wage gap, even if there is no<br />

wage disparity between men and women in<br />

the same occupation (Miller, 1994; Preston and<br />

Whitehouse, 2004; Robinson, 1998). Others<br />

however, argue that occupational segregation<br />

may be relatively unimportant for women’s<br />

wages (Baron and Cobb- Clark, 2010).<br />

Analysing the garment sector in West Bengal,<br />

Ganguly (2006) found that the female workers<br />

earn half the wage than that <strong>of</strong> male workers.<br />

However, analysing the impact <strong>of</strong> globalisation<br />

<strong>of</strong> silk industry in North East India, Goswami<br />

(2006) observed lower wage discrimination<br />

in handloom trade, since the works are mostly<br />

done on contractual basis.<br />

There are a host <strong>of</strong> literature on the<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> wage structure and its determining<br />

factors. Examining the determinants <strong>of</strong> urban<br />

wages in China, Appleton et al., (2005) found<br />

increased returns to education but a decrease<br />

in returns to experience. Based on the notion<br />

<strong>of</strong> efficiency wages, Harrison (2004) found a<br />

two-tier situation that explains why rural wage<br />

rates vary widely among workers and across<br />

regions. He used factors such as number <strong>of</strong><br />

dependents, tribal affiliation with the<br />

enterprise’s manager, sex, tenure, location,<br />

marital status, education, incentives, per capita<br />

cultivated land, season, land irrigation, price<br />

level, etc., in his study on wage discrimination<br />

in rural agricultural environment. Similarly,<br />

working on the important determinants <strong>of</strong><br />

wages in Russia’s transition economy, Ogloblin<br />

and Brock (2005) used factors like education,

142 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

experience, on the job training, tenure, etc.<br />

They also considered factors that help to<br />

capture the firm specific factors like industry,<br />

type <strong>of</strong> firm ownership, occupation, and size<br />

<strong>of</strong> the firm with two other variables like marital<br />

status and secondary employment. Richard<br />

(2007) mentioned that a lot <strong>of</strong> studies linking<br />

gender and labour markets were conducted<br />

in the developed world, whereas developing<br />

countries have very few empirical studies.<br />

Therefore, to examine the male- female wage<br />

determination and gender discrimination in<br />

Uganda, he used factors like age, monthly<br />

wages, education, marital status, urban<br />

residence, number <strong>of</strong> children, non-wage<br />

payment and regions. The results implied that<br />

education is particularly important for females<br />

in order to increase their earnings and thus<br />

has implications for poverty reduction efforts.<br />

The Handloom Industry and the<br />

Categories <strong>of</strong> Workers<br />

Centre <strong>of</strong> attention <strong>of</strong> the present study<br />

is the handloom industry in Assam. This is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the important States in the North-East (NE)<br />

India. The NE States together have the highest<br />

concentration <strong>of</strong> handlooms in the country.<br />

Over 53 per cent <strong>of</strong> the looms in the country<br />

and more than 50 per cent <strong>of</strong> the weavers<br />

belong to the North-Eastern States (Ministry<br />

<strong>of</strong> Textiles, 2010). The State contributes 99 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> Muga silk and 63 per cent <strong>of</strong> Eri silk in<br />

country’s total production <strong>of</strong> Muga and Eri,<br />

respectively (India Brand Equity Foundation,<br />

2010). The industry for generations has been<br />

the major source <strong>of</strong> additional income for the<br />

rural women <strong>of</strong> Assam. More than 60 per cent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the workers are women in the industry<br />

(Goswami, 2006).<br />

The present study categorises the<br />

workers into weavers, reelers, and helpers.<br />

Weavers here are either contractual or<br />

monthly. They normally use fly shuttle or throw<br />

shuttle in Assamese type <strong>of</strong> loom. Apart from<br />

them, there are two other types <strong>of</strong> workers,<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

namely reelers and helpers. Reelers are<br />

involved in reeling activities in the industry<br />

and are either contractual or monthly workers.<br />

Helpers are mostly monthly workers and their<br />

work is to assist the weavers. About one-third<br />

<strong>of</strong> Assam’s 1.2 million weavers are organised<br />

into about 3,744 societies registered under<br />

handloom cooperative societies (Assam<br />

Agricultural Competitiveness Project, 2008).<br />

Single loom household units are common in<br />

the State. Silk weaving is performed in almost<br />

all the districts in Assam. The major weaving<br />

districts <strong>of</strong> vanya (wild) silks are Kamrup (<strong>Rural</strong>),<br />

Nalbari, Udalguri, Baksa, Kokrajhar, Nagaon,<br />

Morigaon, Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Golaghat, and<br />

Mangaldoi. Products like silk, gamochas (towel),<br />

saris, mekhela-chadar, scarves, shawls,<br />

wrappers, etc., are produced for domestic as<br />

well as commercial purposes (Assam<br />

Agricultural Competitiveness Project, 2008).<br />

Sources <strong>of</strong> Data and Research Methodology<br />

The study used both primary and<br />

secondary data. Primary data <strong>of</strong> 300<br />

respondents producing handloom products<br />

were collected from 11 districts in Assam<br />

through uniformly designed structured<br />

interview schedule during June to October,<br />

2010. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were<br />

carried out to collect in-depth information and<br />

to cross-verify a few parameters. Secondary<br />

data were collected from different secondary<br />

sources such as Assam Khadi and Village<br />

Industries Board (AKVIB), Central Silk Board<br />

(CSB), Assam Apex Weavers Artisans<br />

Cooperative Federation Ltd (ARTFED),<br />

Directorate <strong>of</strong> Sericulture, Government <strong>of</strong><br />

Assam, and Block <strong>Development</strong> Offices.<br />

Respondent in the present study is<br />

considered as the unit <strong>of</strong> analysis. The districts,<br />

blocks, and villages were selected through<br />

purposive sampling depending upon intensity<br />

<strong>of</strong> workers and weaving activities. However,<br />

the respondents in the selected villages were<br />

identified through random sampling method.

Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam ... 143<br />

Multiple regression <strong>of</strong> the following log-linear<br />

form is used to study the influences <strong>of</strong><br />

different factors on the wage <strong>of</strong> the workers<br />

in the industry.<br />

LnW = lnA + β 1 lnX 1 + β 2 lnX 2 + β 3 lnX 3 + β 4 lnX 4<br />

+ β 5 lnX 5 + e i<br />

Where,<br />

W = Wage <strong>of</strong> the i th respondent (weavers or<br />

reelers or helpers),<br />

X 1 = Sex dummy <strong>of</strong> the i th respondent, 1 for<br />

male and 0 for female,<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

X 2 = Work experience <strong>of</strong> the i th respondent,<br />

X 3 = Productivity <strong>of</strong> the i th respondent in<br />

value terms,<br />

X 4 = Number <strong>of</strong> years the i th respondent<br />

spent in school,<br />

X 5 = Age <strong>of</strong> the i th respondent, and<br />

e i = Error term.<br />

The descriptive statistics <strong>of</strong> the factors used in<br />

the model are presented in Table 1.<br />

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics <strong>of</strong> the Factors Influencing Wage <strong>of</strong> Contractual Weavers,<br />

Monthly Weavers, Monthly Reelers and Helpers in Handloom Industry in Assam<br />

Average Values<br />

Factors Unit <strong>of</strong> Contractual Monthly Monthly Helpers<br />

Measurement Weavers Weavers Reelers (N = 38)<br />

(N = 151) (N = 55) (N = 13)<br />

Annual Rupees 24,978.81 29,827.27 8,744.74 12,092.31<br />

Income (7,695.75) (17,215.76) (6,471.80) (8,824.44)<br />

Sex 1 for male, 0.23 0.12 0.05 0.54<br />

Dummy 0 for female (0.42) (0.33) (0.22) (0.52)<br />

Work Years 8.12 11.98 12.5 8.07<br />

Experience (6.24) (7.53) (7.36) (8.65)<br />

Productivity Rupees/ 63.17 98.85 46.73 42.15<br />

Days (18.21) (62.46) (33.08) (30.17)<br />

Education Years 6.02 5.62 3.92 4.15<br />

(4.21) (3.52) (4.00) (3.65)<br />

Age Years 27.95 31.81 35.34 25.77<br />

(6.87) (8.44) (7.71) (13.15)<br />

Note: Figures in parentheses represent standard deviation.<br />

The productivity <strong>of</strong> a worker in the study<br />

is measured by the annual income <strong>of</strong> the<br />

workers generated from such activities divided<br />

by the number <strong>of</strong> productive days <strong>of</strong> the<br />

worker. The number <strong>of</strong> productive days is<br />

measured by daily working hours multiplied<br />

by the number <strong>of</strong> working days and divided<br />

by eight hours. Separate regression is run for<br />

the contractual weavers, monthly weavers,<br />

monthly reelers, and helpers. However,

144 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

because <strong>of</strong> poor number <strong>of</strong> responses (only<br />

13), our attempt to analyse the influence <strong>of</strong><br />

different factors on wage <strong>of</strong> the helpers is<br />

dropped. Although the number <strong>of</strong> respondents<br />

in the category <strong>of</strong> monthly rated reelers is only<br />

38, to throw some light in our analysis, we<br />

considered the category for further analysis.<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

The influence <strong>of</strong> different factors on<br />

wage structure <strong>of</strong> the contractual workers in<br />

In the handloom industry in Assam, wage<br />

<strong>of</strong> a contractual weaver does not depend on<br />

sex <strong>of</strong> the individual and sex dummy is found<br />

to be not significant in case <strong>of</strong> contractual<br />

weavers having a P value <strong>of</strong> 0.96. It is found in<br />

most <strong>of</strong> the cases during primary data collection<br />

that a male or a female weaver earns the same<br />

wage for the same kind <strong>of</strong> work, if the work is<br />

contractual. This finding is similar to the<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

the handloom industry in Assam is presented<br />

in Table 2. The sample size <strong>of</strong> the contractual<br />

weavers is 151. The influences <strong>of</strong> different<br />

factors on annual wage <strong>of</strong> the contractual<br />

weavers are estimated by using ordinary least<br />

square (OLS) technique. The value <strong>of</strong> F test in<br />

OLS estimation indicates that the model is<br />

significant at 1 per cent level with an F value<br />

<strong>of</strong> 26.19. The value <strong>of</strong> R 2 is 0.50, which reveals<br />

that the model explains 50 per cent <strong>of</strong> the<br />

variation in average annual wage <strong>of</strong> the<br />

contractual weavers.<br />

Table 2 : Factors Influencing the Wage <strong>of</strong> Contractual<br />

Weavers in Handloom Industry in Assam<br />

Explanatory Factors Coefficients Robust Standard Error t-Statistics P>|t| VIF<br />

Constant 7.256 0.460 15.78 0.000 —<br />

Sex Dummy 0.002 0.048 0.05 0.962 1.27<br />

Work Experience -0.001 0.025 -0.03 0.980 1.56<br />

Productivity 0 .768 0.075 10.28 0.000 1.02<br />

Education Level -0.093 0.018 -0.92 0.358 1.03<br />

Age -0.093 0.088 -1.06 0.292 1.36<br />

R20. 501<br />

Adjusted R2 0.484<br />

F Value (5, 145) 26.19<br />

Observations 151<br />

Durbin Watson 1.669<br />

Note: i) Dependent variable is annual wage <strong>of</strong> the contractual weavers.<br />

ii) 1%, 5% and 10% level <strong>of</strong> significance are considered.<br />

findings <strong>of</strong> Goswami (2006), who observed<br />

lower wage discrimination in the silk industry<br />

in Assam. On the other hand, work experience<br />

<strong>of</strong> a contractual weaver is found to be not<br />

significant having a P value <strong>of</strong> 0.98. This implies<br />

that the wage <strong>of</strong> a contractual weaver is less<br />

dependent on experience <strong>of</strong> the weaver. It<br />

means that, irrespective <strong>of</strong> the work<br />

experience <strong>of</strong> the weaver, his or her wages

Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam ... 145<br />

will depend mostly on the factors other than<br />

his or her work experience. A weaver who<br />

completes a stipulated amount <strong>of</strong> work in a<br />

given time gets more wage than an<br />

experienced weaver who does lesser work in<br />

the same time.<br />

The influence <strong>of</strong> productivity on wage<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> the contractual weavers is found<br />

to be significant at 1 per cent level with a P<br />

value <strong>of</strong> 0.000, which implies that, other<br />

factors keeping constant, 1 per cent increase<br />

in productivity leads to a 0.77 per cent increase<br />

in wages <strong>of</strong> the contractual weavers. It means<br />

that more the productivity <strong>of</strong> the worker, more<br />

will be the increment in the contractual<br />

weavers’ wages. In contrast, the influence <strong>of</strong><br />

education on the wage <strong>of</strong> the contractual<br />

weaver is not significant (P = 0.36). This implies<br />

that, whether the weaver is more qualified or<br />

less, he or she will earn the same wage for the<br />

same kind <strong>of</strong> work. As also found in FGDs, it is<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

the efficiency <strong>of</strong> the worker that matters in<br />

the handloom industry in Assam rather than<br />

his or her educational qualification. In other<br />

words, what matters is his or her capability to<br />

produce more in less time. Similarly, age <strong>of</strong><br />

the contractual weaver is also found to be not<br />

significant on the annual wage <strong>of</strong> the weaver.<br />

The VIFs (Variance Inflation Factor) <strong>of</strong> all the<br />

independent factors are less than 1.6. This<br />

implies that the multicollinearity problem<br />

among the factors is almost negligible in the<br />

above model.<br />

An attempt is also made to see the<br />

influences <strong>of</strong> the above mentioned factors on<br />

the wage structure <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

weavers. The sample size <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

weavers was 55. The influences <strong>of</strong> different<br />

factors on annual wage <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

weavers were estimated by using OLS<br />

technique. The model is significant at 1 per<br />

cent level with an F value <strong>of</strong> 17.14 (Table 3).<br />

Table 3: Factors Influencing the Wage <strong>of</strong> Monthly Rated Weavers<br />

in Handloom Industry in Assam<br />

Explanatory Factors Coefficients Robust Standard Error t-Statistics P>|t| VIF<br />

Constant 7.714 1.365 5.65 0.000 —<br />

Sex Dummy 0 .432 0.160 2.71 0.009 1.09<br />

Work Experience -0.085 0.099 0.86 0.393 1.75<br />

Productivity 0 .653 0.201 3.25 0.002 1.19<br />

Education Level -0.086 0.081 1.06 0.293 1.04<br />

Age -0.074 0.336 0.22 0.826 1.60<br />

R2 0.418<br />

Adjusted R2 0.359<br />

F Value (5, 49) 17.14<br />

Observations 55<br />

Durbin Watson 1.075<br />

Note : i) Dependent variable is annual wage <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated weavers.<br />

ii) 1%, 5% and 10% level <strong>of</strong> significance are considered.

146 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

The value <strong>of</strong> R 2 is 0.42, which reveals that the<br />

model explains 42 per cent <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

variation in average annual wage <strong>of</strong> the<br />

monthly rated weavers. It is found that the<br />

influence <strong>of</strong> the factor ‘sex’ on wage structure<br />

<strong>of</strong> the monthly rated weaver is found to be<br />

significant at 1 per cent level, which implies<br />

that, other factors keeping constant, if the<br />

respondent is a male, his average wage will<br />

be more by 0.43 per cent. It is found in FGDs<br />

that, if the weaver is hired on monthly basis,<br />

for the same kind <strong>of</strong> job, a female weaver earns<br />

relatively less than a male weaver. Since the<br />

females also have domestic chores apart from<br />

the weaving works, if given a choice, the<br />

owners are reluctant to hire them on the same<br />

monthly wage rate as that <strong>of</strong> male. Analysing<br />

the implications <strong>of</strong> the neo-liberal reforms on<br />

workers in the Indian garment industry in the<br />

era <strong>of</strong> post-multi-fibre arrangement, Ganguly<br />

(2006) also found that, in West Bengal, women<br />

workers are paid much lesser than male<br />

workers. Thus, in case <strong>of</strong> contractual weavers,<br />

it is found that a male or female weaver will<br />

earn the same wage for the same kind <strong>of</strong> work<br />

related to weaving. Whereas, in case <strong>of</strong><br />

monthly rated weaver, a female weaver will<br />

earn relatively less than a male weaver for the<br />

same nature <strong>of</strong> job.<br />

Analysing the influence <strong>of</strong> work<br />

experience on monthly rated weaver, it is<br />

found that the length <strong>of</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> monthly<br />

rated weavers has no bearing on their wage. It<br />

is found during FGDs that the owner fixes a<br />

standard wage for workers who have<br />

experience beyond a certain threshold level.<br />

Owners are indifferent towards experience<br />

beyond that level. Threshold level here means<br />

a minimum level <strong>of</strong> work experience that an<br />

owner looks for in a worker. It is mostly three<br />

years in the study area as observed in FGDs.<br />

These results are similar to the results found<br />

in case <strong>of</strong> contractual weavers, where work<br />

experience is also found to be not significant<br />

on the wage structure <strong>of</strong> the weaver.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

Looking at the influence <strong>of</strong> productivity<br />

on wage structure <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

weavers, it is found that the productivity has a<br />

positive influence on the wage and is<br />

significant at 1 per cent level <strong>of</strong> significance.<br />

This implies that, other factors keeping<br />

constant, 1 per cent increase in productivity<br />

leads to a 0.65 per cent increase in wages <strong>of</strong> a<br />

monthly rated weaver (Table 3). It means that<br />

more the productivity <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

weaver, more will be the increment in the<br />

monthly rated weaver’s wage. It is observed<br />

in the study area that the owners keep track<br />

<strong>of</strong> monthly productivity <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated<br />

workers based on their daily contribution to<br />

their output. This implies that, if an owner<br />

observes that a worker works for relatively<br />

more than a stipulated period per day (usually<br />

8 hours), then the owner prefers to reward<br />

him with an increment in his wages. The<br />

influence <strong>of</strong> productivity is very much similar<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> contractual weavers. Thus, the<br />

productivity <strong>of</strong> the workers is found to have a<br />

significant influence on the wages <strong>of</strong> both<br />

contractual as well as monthly rated weavers.<br />

Whether the weaver is contractual or monthly<br />

rated, an increase in productivity will bring<br />

about an increment in his or her wages. In<br />

contrast, the effect <strong>of</strong> education level on wage<br />

<strong>of</strong> the monthly rated weavers is not significant.<br />

Thus, it is found that the wages <strong>of</strong> both<br />

contractual and monthly rated weavers will not<br />

significantly depend on educational<br />

qualification <strong>of</strong> the weavers. The influence <strong>of</strong><br />

age <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated weaver on annual<br />

wage is also found to be not significant. Similar<br />

result was also found in case <strong>of</strong> contractual<br />

weavers. VIFs <strong>of</strong> all the independent variables<br />

are 1.75 or less. This implies that the<br />

multicollinearity problem among the factors<br />

is almost negligible in the above model.<br />

An attempt is also made to see the<br />

influence <strong>of</strong> the factors on wage <strong>of</strong> the<br />

monthly rated reelers. The sample size <strong>of</strong> the<br />

reelers in the study is 38. The influence <strong>of</strong>

Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam ... 147<br />

different factors on wage <strong>of</strong> the reelers was<br />

estimated by using OLS technique. The model<br />

is significant at 1 per cent level with an F value<br />

<strong>of</strong> 4.24 (Table 4). The value <strong>of</strong> R 2 is 0.53, which<br />

reveals that the model explains 53 per cent <strong>of</strong><br />

the variation in the annual average wage <strong>of</strong><br />

the reelers. It is found that the influence <strong>of</strong><br />

the factor sex on wage structure <strong>of</strong> the<br />

monthly rated reeler is not significant. It<br />

means that a male or female reeler will earn<br />

similar wage for a similar nature <strong>of</strong> work.<br />

Analysing the influence <strong>of</strong> work experience<br />

Table 4: Factors Influencing the Wage <strong>of</strong> Monthly Rated<br />

Reelers in Handloom Industry in Assam<br />

Explanatory Factors Coefficients Robust Standard Error t-Statistics P>|t| VIF<br />

Constant 6.773 0.881 7.69 0.000 —<br />

Sex Dummy 0.554 0.399 1.39 0.175 1.14<br />

Work Experience -0.042 0.085 -0.50 0.621 1.33<br />

Productivity 0.490 0.193 2.55 0.016 1.37<br />

Education Level 0.015 0.075 0.20 0.840 1.40<br />

Age 0.119 0.247 0.48 0.635 1.38<br />

R20.525 Adjusted R2 0.452<br />

F Value (5, 32) 4.24<br />

Observations 38<br />

Durbin Watson 1.212<br />

Note : i) Dependent variable is annual wage <strong>of</strong> the monthly rated reelers.<br />

ii) 1%, 5% and 10% level <strong>of</strong> significance are considered.<br />

Looking at the effect <strong>of</strong> productivity on<br />

wage structure <strong>of</strong> monthly rated reelers, it is<br />

found that productivity has a positive influence<br />

and is significant at 1 per cent level. This<br />

implies that, other factors keeping constant, 1<br />

per cent increase in productivity leads to a 0.49<br />

per cent increase in wage. It means that more<br />

the productivity <strong>of</strong> a reeler, more will be the<br />

increment in his or her wage. As it is observed<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

on wage <strong>of</strong> the reelers, it is found that the<br />

length <strong>of</strong> experience has no significant<br />

influence on wage <strong>of</strong> a reeler. The owners<br />

mostly fix a standard wage for reelers who have<br />

experience beyond a certain threshold level<br />

and they are indifferent towards experience<br />

beyond that level. Mentioned earlier, threshold<br />

level here means a minimum level <strong>of</strong> work<br />

experience that an owner looks for in a worker.<br />

This is mostly 3 years, as observed in the study<br />

area.<br />

in the study area, in case <strong>of</strong> reelers also owners<br />

keep a track on monthly productivity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

reelers based on their daily contribution to<br />

output. This implies that, if an owner observes<br />

a worker working for relatively more than a<br />

stipulated period per day (usually 8 hours), then<br />

the owner prefers to reward him with an<br />

increment in his wage. These results are very<br />

much similar to the results we found in case

148 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

<strong>of</strong> contractual as well as monthly rated<br />

weavers. Thus, the productivity <strong>of</strong> the reelers<br />

is found to have a significant effect on wages<br />

<strong>of</strong> the contractual weavers, monthly rated<br />

weavers as well as on wages <strong>of</strong> the reelers.<br />

The influence <strong>of</strong> the level <strong>of</strong> education on<br />

wage <strong>of</strong> a reeler is not significant. This implies<br />

that education does not have any significant<br />

effect on reelers’ wages. Thus, it is found that<br />

the wages <strong>of</strong> the contractual weavers,<br />

monthly weavers as well as reelers will not<br />

depend much on the number <strong>of</strong> years the<br />

worker spent in school. Reeler’s age is also<br />

found to have an insignificant influence on<br />

their annual wage. Similar results are found in<br />

case <strong>of</strong> contractual as well as monthly rated<br />

weavers. The VIFs <strong>of</strong> all the independent factors<br />

are 1.4 or less. This implies that the<br />

multicollinearity problem among the factors<br />

is almost negligible in the above model.<br />

From the results it is established that<br />

there is hardly any gender discrimination in<br />

case <strong>of</strong> contractual workers in Assam. The<br />

women contractual workers are capable <strong>of</strong><br />

earning more than their male counterparts, if<br />

they finish a particular work within a stipulated<br />

period <strong>of</strong> time. As observed in FGDs, few <strong>of</strong><br />

the contractual reelers are found in Palasbari<br />

(in Kamrup district <strong>of</strong> Assam), who are capable<br />

<strong>of</strong> earning more than the reelers engaged in<br />

the industries on monthly basis. These<br />

contractual workers are in a position to work<br />

Notes<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

for longer duration. It is also found in the FGDs<br />

that the employment pattern in the handloom<br />

industry in Assam has shifted from monthly<br />

rated system to contractual system during last<br />

15 years. Similar pattern was also found by<br />

Ramaswamy (2008) in his study on the Textile<br />

and Apparel industry at all India level. In<br />

comparison to contractual weavers, in case <strong>of</strong><br />

monthly rated weavers and monthly rated<br />

reelers, wage discrimination is found.<br />

Conclusions<br />

With the elimination <strong>of</strong> import quota<br />

restriction and expansion <strong>of</strong> trade, wage<br />

structure in the handloom industry in Assam<br />

has taken a contractual pattern. Among the<br />

factors such as age, productivity, sex,<br />

experience, and education, it is found that only<br />

the productivity <strong>of</strong> the workers influence<br />

wage structure <strong>of</strong> the contractual workers<br />

significantly. In contrast, in case <strong>of</strong> monthly<br />

rated weavers, along with productivity, gender<br />

(sex) <strong>of</strong> the respondents influence significantly<br />

on their wages. Gender wage disparity is found<br />

crucial for monthly rated weavers and reelers.<br />

Thus, government machinery should come out<br />

heavily on addressing the problems related to<br />

gender wage discrimination in monthly rated<br />

weavers and reelers, and back up support<br />

facilities for contractual workers <strong>of</strong> the industry<br />

in the State.<br />

1 Horizontal segregation refers to the distribution <strong>of</strong> women and men across occupations.<br />

Vertical segregation refers to the distribution <strong>of</strong> men and women in the job hierarchy in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> status and occupation (Randriamaro, 2005).<br />

References<br />

1. Allen, J. and N. Henry (2001), “Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society at Work: Labour and Employment in the Contract<br />

Service Industries”, Transactions <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> British Geographers, New Series, 22(2), 180-196.<br />

2. Assam Agricultural Competitiveness Project (2008), “Marketing Study <strong>of</strong> Muga and Eri Silk Industry in<br />

Assam”, Central Silk Board, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Textiles, Government <strong>of</strong> India.

Factors Influencing Wage Structure <strong>of</strong> Handloom Workers in Assam ... 149<br />

3. Appleton, S., L. Song, and Q. Xia (2005), “Has China Crossed the River? The Evolution <strong>of</strong> Wage Structure in<br />

Urban China during Reform and Retrenchment”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Comparative Economics, 33, 644-663.<br />

4. Baishya, P. (2005), The Silk Industry <strong>of</strong> Assam, Spectrum Publications, Guwahati, ISBN 81-87502-98-3.<br />

5. Baron, J. and D. Cobb- Clark (2010), “Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap in Private and<br />

Public Sector Employment: A Distributional Analysis Forthcoming in the Economic Record”, Economic<br />

Record, 86(273), 227-246.<br />

6. Berik G., Y. van der M. Rodgers, and J. E. Zveglich (2004), “International Trade and Gender Wage<br />

Discrimination: Evidence from East Asia”, Review <strong>of</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Economics, 8(2), 237–254.<br />

7. Blau, F.D., and L.M. Kahn, (2000), “Gender Differences in Pay”, The Journal <strong>of</strong> Economic Perspectives, 14, 75-<br />

99<br />

8. Bonnie, B. J. and F. E. Harrison (2005), “Incidence and Duration <strong>of</strong> Unemployment Spells: Implications for<br />

Male-Female Wage Differentials”, The Quarterly Review <strong>of</strong> Economics and Finance, 45, 824-847.<br />

9. Cobb- Clark, D.A and M. Tan (2011), “Noncognitive Skills, Occupational Attainment, and Relative Wages”,<br />

Labour Economics, 18, 1-13.<br />

10. Darity, W. (1991), “Efficiency Wage Theory: Critical Reflections on the Neo-Keynesian Theory <strong>of</strong><br />

Unemployment and Discrimination”, in New Approaches to Economic and Social Analyses <strong>of</strong><br />

Discrimination, R. Cornwall and P. Wunnava (Eds.), Westport, CT: Praeger, 39–54.<br />

11. Dickens, W. T., and L. F. Katz (1987), “Inter-Industry Wage Differences and Industry Characteristics”, in<br />

Unemployment and the Structure <strong>of</strong> Labour Markets, K. Lang and J.S. Leonard (Eds.), New York: Basil Blackwell<br />

Inc., 48–89.<br />

12. Fairlie, R.W. (2003), “An Extension <strong>of</strong> the Blinder- Oxaca Decomposition Technique to Logitand Probit<br />

Models”, Discussion Paper No. 843, Economic Growth Center, Yale University.<br />

13. Ganguly, R. (2006), “Neoliberal <strong>Development</strong> and its Implications for the Garment Industry and its Workers<br />

in India: A Case Study <strong>of</strong> West Bengal”, School <strong>of</strong> Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wollongong, Australia, NSW 2522.<br />

14. Gerry, C. J., B. Y. Kim and C. A Li (2004), “The Gender Wage Gap and Wage Arrears in Russia: Evidence from<br />

RLMS”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Population Economics, 17(2), 267-288.<br />

15. Goswami, K. (2006), “Impact <strong>of</strong> Globalization <strong>of</strong> Silk Industry in North East India: An Assessment from<br />

Gender Perspectives”, accessed on 15-05-2011 in http://faculty.washington.edu/karyiu/confer/<br />

beijing06/papers/goswami.pdf<br />

16. Groshen, E. (1991), “The Structure <strong>of</strong> the Female/Male Wage Differential”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Population Economics,<br />

26, 457-472.<br />

17. Harrison, F. E., (2004), “Analysis <strong>of</strong> Wage Formation Processes in <strong>Rural</strong> Agriculture”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Developing<br />

Areas, 38(1), 79-92.<br />

18. India Brand Equity Foundation (2010), “Assam”, accessed on 15-08-2011 in http://www.ibef.org/download/<br />

Assam_060710.pdf<br />

19. Lichter, D.T. and J.A Costanzo (1987) “Nonmetropolitan Underemployment and Labour Force<br />

Composition”, <strong>Rural</strong> Sociology, 52, 329-44.<br />

20. Miller, P. W. (1994), “Occupational Segregation and Wages in Australia”, Economic Letters, 45, 367-371.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012

150 Alin Borah Bortamuly, Kishor Goswami<br />

21. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Textiles (2010), “Accelerating Growth and <strong>Development</strong> <strong>of</strong> Textile Sector in the North Eastern<br />

Region”, Government <strong>of</strong> India, accessed on 15-05-2011 in http://www.pib.nic.in/archieve/ecssi/<br />

ecsii2010/Textile.pdf<br />

22. Mumford, K. and P. N. Smith (2007), “The Gender Earnings Gap in Britain : Including the Workplace”, The<br />

Manchester School, 75(60), 653-672.<br />

23. Norsworthy, K. L. (2003), “Understanding Violence against Women in Southeast Asia: A Group Approach<br />

in Social Justice Work”, International Journal for the Advancement <strong>of</strong> Counselling, 25 (2/3), 145-156.<br />

24. Ogloblin, C. and G. Brock (2005), “Wage Determination in Urban Russia : Underemployment and the Gender<br />

Differential”, Economic Systems, 29, 325-343.<br />

25. Oxaca R. (1973), “Male- Female wage Differentials in Urban Labour Markets”, International Economic Review,<br />

14(3), 693-709.<br />

26. Preston, A. and G. Whitehouse (2004), “Gender Differences in Occupation <strong>of</strong> Employment within Australia”,<br />

Australian Journal <strong>of</strong> Labour Economics, 7(3), 309-327.<br />

27. Ramaswamy, K. V. (2008), “Trade, Restructuring and Labour Study <strong>of</strong> Textile and Apparel Industry in India”,<br />

ISAS Working Paper No. 43, May.<br />

28. Reddy, N. (2006), “Women Handloom Weavers: Facing the Brunt”, Gender and Trade Policy, 1-7, accessed on<br />

15-04-2009 in http://www.boell-india.org/downloads/Micros<strong>of</strong>t_Word_-_HBF-DNR_presentation.pdf<br />

29. Richard, S. (2007), “Wage Determination and Gender Discrimination in Uganda”, Research Series No. 50,<br />

Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC), Makerere University Campus, Kampala, Uganda.<br />

30. Robinson, D. ( 1998), “Differences in Occupational Earnings by Sex”, International Labour Review, 137(1),<br />

3-32.<br />

31. Sinha, A., K. A. Siddiqui, P. Munjal, S. Subudhi (2003), “Impact <strong>of</strong> Globalization on Indian Women Workers:<br />

A Study with CGE Analysis”, <strong>National</strong> Council <strong>of</strong> Applied Economic Research (NCAER), accessed on 15-04-<br />

2008 in http://www.isst-india.org/PDF/A%20Study%20with%20CGE%20Analysis.pdf<br />

32. Stabler, J.C. (1999) “<strong>Rural</strong> America: A Challenge to Regional Scientists,” Annals <strong>of</strong> Regional Science, 33, 1-<br />

14.<br />

33. Standing, G. (1992), “Alternative Routes to Labour Flexibility”, in Pathways to Industrialization and<br />

Regional <strong>Development</strong>, M. Storper and A. J. Scott (eds), Rutledge, London and New York.<br />

34. Sudalaimuthu, S. and S. Devi (2006), “Handloom Industry in India”, accessed on 15-04-2009 in http://<br />

www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/1/10/handloom-industry-in-india1.asp<br />

35. Randriamaro, Z (2005), “Gender and Trade”, Overview Report, BRIDGE <strong>Development</strong> – Gender, Accessed<br />

on 15-04-2009 in www.bridge.ids.ac.uk/reports/CEP-Trade-OR.pdfSimilar<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. (2) pp. 151 - 162<br />

NIRD, Hyderabad.<br />

INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS<br />

FOR FARMLAND DEVELOPMENT :<br />

THE CASE OF ETHIOPIA<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Abayineh Amare Woldeamanuel*<br />

Fekadu Beyene Kenee**<br />

Land is an asset <strong>of</strong> enormous importance for billions <strong>of</strong> rural dwellers in the<br />

developing world. Increased land access for the poor can also bring direct benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

poverty alleviation, not least by contributing directly to increased household food<br />

security. In countries where agriculture is a main economic activity (e.g. Ethiopia),<br />

access to land is a fundamental means whereby the poor can ensure household food<br />

supplies and generate income. Therefore, this study aimed to sketch-out institutional<br />

arrangements to get access to farmland and to empirically examine institutional<br />

mechanisms to settle dispute arising from contracting farmland in Amigna district.<br />

The result revealed that land rental markets appeared to be the dominant<br />

institutional arrangement to get access to farmland next to Peasant Association<br />

allocated arrangement. This created breathing space for short-term land acquisition<br />

for landless and/or nearly landless farm households. Moreover, the dominant<br />

transactions took place among a neighbour followed by transfers between friends in<br />

the same peasant association, and relatives in the same peasant association. The<br />

foregoing discussion with key informants revealed that such transfers are informal<br />

and there are no formal rules and regulations to enforce land transfers to reduce high<br />

risk that may arise from these transactions. Regarding the mechanisms used by the<br />

sample respondents’ in order to resolve disputes, farmers claimed their rights through<br />

local elders, religious leaders, and local institutions. This may be due to the perception<br />

<strong>of</strong> legal uncertainty over landholdings particularly in the case <strong>of</strong> rental contracts,<br />

which existed informally. Therefore, policy and development interventions should<br />

give emphasis to improvement <strong>of</strong> such institutional arrangements that create venue<br />

for land access.<br />

Introduction<br />

Questions about land markets are central<br />

to development policy, as underlined recently<br />

in 2008 World <strong>Development</strong> Report. The policy<br />

immensely advocates liberal reform that<br />

attempted to fortify private markets (primarily<br />

* Jimma University, College <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>,<br />

P.O. Box. 307 Jimma, Ethiopia.<br />

** College <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, P.O.Box.161,<br />

Haramaya, Ethiopia.<br />

The authors thank Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education for financing the research work, special thanks to Amigna District<br />

Bureau <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong> for their generous cooperation during data collection,<br />

also thank Alemayehu Amare who was involved in organising and facilitating data collection in the<br />

household survey. Special thanks go to all households who responded to the questions.

152 Abayineh Amare Woldeamanuel, Fekadu Beyene Kenee<br />

via rentals) in a way that enhance efficiency<br />

and equity outcomes (World Bank, 2007).<br />

Over the past two decades a wave <strong>of</strong><br />

proposals for land tenure reform in many<br />

African countries raised questions about land<br />

markets as a means <strong>of</strong> allocating land that have<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ound political and economic implications<br />

(Toulmin and Quan, 2000). However, until late<br />

twentieth century, it was a perception <strong>of</strong> land<br />

as being relatively abundant due to low<br />

population densities in many parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

continent that influenced policy makers’ views<br />

to give little attention for land markets in<br />

development policy (Deninger and Feder,<br />

2001).<br />

Ethiopia is one <strong>of</strong> the largest countries in<br />

Africa both in terms <strong>of</strong> land area (1.1 million<br />

km 2 ) and population (about 74 million).<br />

Ethiopian economy is based mainly on<br />

agriculture which provides employment for 85<br />

per cent <strong>of</strong> the labour force and accounts for a<br />

little over 50 per cent <strong>of</strong> the GDP and about<br />

90 per cent <strong>of</strong> export revenue (CSA, 2007).<br />

Demeke (1999) and Belay and Manig (2004)<br />

noted that access to land is an important issue<br />

for the majority <strong>of</strong> Ethiopian people who, in<br />

one way or the other, depend on agricultural<br />

production for their income and subsistence.<br />

Similarly, FAO (2002) pointed out that in areas<br />

where other income opportunities are limited<br />

(for example, rural non-farm employment<br />

creation); access to land determines not only<br />

household level <strong>of</strong> living and livelihood, but<br />

also food security. The extent to which<br />

individuals and families are able to be food<br />

secure depends in large part on the<br />

opportunities they have to increase their<br />

access to assets such as land.<br />

However, as population grows, the<br />

pressure on land is increasing and<br />

opportunities <strong>of</strong> getting land for allocating to<br />

newly emerging households are quite limited<br />

since then. As a result <strong>of</strong> increasing population<br />

<strong>of</strong> young farmers who are <strong>of</strong>ten landless, there<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

will be unbalanced resource endowment<br />

(Bezabih et al., 2005). In Ethiopia, the average<br />

landholding is only about one hectare per<br />

household and the population growth rate is<br />

creating increasing pressure on land and other<br />

natural resources (CSA, 2007). Nevertheless,<br />

it is also felt that in area <strong>of</strong> no frequent land<br />

redistribution, there is a skewed landholding<br />

pattern that might have resulted in<br />

landlessness (Bruce, 1994; Hussein, 2001). The<br />

cumulative effect <strong>of</strong> skewed landholding<br />

pattern, heterogeneity in resource<br />

endowment, and uncertainties and limitations<br />

in credit and other markets leads to the<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> informal land transactions and<br />

the opportunities to trade and exchange factor<br />

endowments (Teklu, 2004; Freeman et al.,<br />

1996).<br />

In Ethiopia, land has been owned by the<br />

state since 1975. Following the 1975 land<br />

reform proclamation, the derge regime (1975-<br />

1991) prohibited both fixed cash rental and<br />

sharecropping tenancy relations. The current<br />

government lifted these restrictions (however,<br />

the duration and area <strong>of</strong> land supplied to the<br />

markets are limited) and at present there are<br />

different institutional arrangements in place<br />

that help to get access to farmland (Belay,<br />

2004; Yared, 1995).<br />

The objectives <strong>of</strong> the study were:<br />

* To explore institutional arrangements<br />

that facilitate access to farmland and<br />

* To examine institutional mechanisms to<br />

enforce rental contracts.<br />

Framework <strong>of</strong> Analysis<br />

This study was designed in the lines <strong>of</strong><br />

Institutional Analysis and <strong>Development</strong> (IAD)<br />

framework developed by Ostrom et al. (1994).<br />

The analysis consists <strong>of</strong> three major<br />

components such as initial conditions, action<br />

plan, and outcomes. The initial conditions, in<br />

this study context, refer to a set <strong>of</strong> issues where

Institutional Arrangements for Farmland <strong>Development</strong> : The Case <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia 153<br />

explanatory variables are emanating from.<br />

Action arena is influenced by a number <strong>of</strong><br />

exogenous variables, broadly categorised to<br />

be physical/material conditions, attributes <strong>of</strong><br />

the community/household, and rules that<br />

create incentives and constraints for certain<br />

actions (Ostrom et al., 1994). Based on Ostrom<br />

et al. (1994) components <strong>of</strong> initial condition<br />

are explained as follows;<br />

Physical/material conditions: Includes<br />

livestock ownership, landholding, and financial<br />

endowment that the households possess,<br />

mobilise, use and exchange with others. It also<br />

refers to the physical infrastructural<br />

development in the district that has an<br />

influence on the renting behaviour <strong>of</strong> the<br />

households.<br />

Community (household) attributes : The<br />

community/household broadly involved in the<br />

situation is another important variable. Several<br />

attributes <strong>of</strong> the community/household may<br />

influence the outcome <strong>of</strong> an action situation.<br />

These include demographic attributes such as<br />

education level, size <strong>of</strong> the household/<br />

community, and employment level.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

Rules –in-use (formal and informal rules<br />

or norms): Each action is influenced by sets <strong>of</strong><br />

rules-in –use. These are the rules actually used<br />

by the people to guide or govern their<br />

behaviour in repetitive activities (Ostrom,<br />

1992). Ostrom (1992) also noted that changing<br />

the working rules <strong>of</strong> an activity could result in<br />

changes to the outcome <strong>of</strong> the activity. In the<br />

context studied, it refers to any rules or norms<br />

in place that help to increase access to land.<br />

As configured in Figure 1, the framework<br />

considers the effects <strong>of</strong> all components in the<br />

initial condition on the action arena in which<br />

participation in informal land transactions is<br />

viewed as dependent variable. Therefore,<br />

assessing major reasons and degree <strong>of</strong><br />

influences <strong>of</strong> those variables on the initial<br />

conditions in the action arena is the central<br />

theme <strong>of</strong> this empirical analysis. In the action<br />

arena, the decisions <strong>of</strong> households to<br />

participate in informal land transactions is<br />

influenced by imperfection in credit market,<br />

heterogeneity in the distribution <strong>of</strong> initial<br />

wealth and specific human capital, and<br />

rationing <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>f-farm labour opportunities<br />

which are constituted in the initial conditions<br />

(Skoufias, 1995; Sadoulet et al., 2001).<br />

Figure 1: The Institutional Analysis and <strong>Development</strong> Framework<br />

Physical<br />

conditions<br />

Community/<br />

household<br />

attributes<br />

Rules in<br />

use<br />

Source: Based on Ostrom et al. (1994),modified.<br />

Action arena<br />

(participation in<br />

informal land<br />

transactions)<br />

Outcomes<br />

(improve<br />

access to<br />

land)

154 Abayineh Amare Woldeamanuel, Fekadu Beyene Kenee<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> areas are commonly affected by<br />

credit rationing. Asymmetric information’s<br />

together with dispersed location <strong>of</strong> potential<br />

clients as well as poor rural infrastructure make<br />

it very inconvenient for lending institutions to<br />

provide their services. As a result, farmers are<br />

left solely with their own capital, most <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

insufficient to cover all necessary investments<br />

connected with cultivation. Accordingly,<br />

farmers limited by financial constraints,<br />

notwithstanding their managerial abilities and<br />

others endowment in their possessions, can<br />

not engage in land market transaction<br />

(Sadoulet et al., 2001).<br />

To examine determinants <strong>of</strong> household<br />

participation in land rental markets, the range<br />

and diversity <strong>of</strong> assets at one’s own disposal<br />

need to be a point <strong>of</strong> concern. Thus, the<br />

decision <strong>of</strong> household to participate in these<br />

markets is influenced by skewed landholding<br />

pattern, imbalance livestock ownership, and<br />

in-proportional labour force <strong>of</strong> the household<br />

(Skoufias, 1995).<br />

Land transactions can play an important<br />

role for several reasons. First, it provides land<br />

access to those who are productive but own<br />

little or no land. Second they allow the<br />

exchange <strong>of</strong> land as the <strong>of</strong>f-farm economy<br />

develops. Third, they facilitate the use <strong>of</strong> land<br />

as collateral to access credit markets<br />

(Deininger et al., 2004). To benefit from these<br />

outcomes <strong>of</strong> land rental markets, the existing<br />

rules or norms must ensure security <strong>of</strong><br />

property rights. This is a prerequisite that<br />

determine willingness <strong>of</strong> individuals to enter<br />

the action arena (Deininger et al., 2004).<br />

However, in conditions where poor<br />

infrastructure development, lack <strong>of</strong> well<br />

enforced property rights, and poor institutional<br />

developments (credit market imperfection<br />

that deny smallholders insurance against<br />

shocks such as bad harvest or accident), land<br />

markets lead to distress sale (Belay, 2004;<br />

Deininger et al., 2004; Teklu, 2004). This is a<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

negative consequence where individuals<br />

come across after evaluating the outcomes <strong>of</strong><br />

action arena. As indicated in Figure 1, the<br />

result <strong>of</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> the outcomes will have<br />

an implicit or explicit implication on both<br />

action arena and initial condition.<br />

Methodological Approach<br />

The Study Site: This paper is based on<br />

evidence from four peasant associations in<br />

Amigna district in Arsi zone, which are<br />

characterised by informal land transactions<br />

that are predominant. It is located between<br />

7º45' – 8º07’ N latitude and 39º40' – 40 º 38’ E<br />

longitudes. The total geographical area <strong>of</strong> the<br />

district is about 134,372 ha with 21 per cent<br />

Weyna-dega, and 79 per cent Kola, and consists<br />

<strong>of</strong> 18 rural PAs and one urban PA (Addele)<br />

(ABOARD, 2009). It is located at about 260 km<br />

and 134 km far from Addis Ababa and Assela,<br />

respectively along the main road to the<br />

southeastern direction <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia. The altitude<br />

<strong>of</strong> the area ranges between 560 meters at the<br />

lowest to 2100 meters at the highest above<br />

mean sea level. The mean annual rainfall <strong>of</strong><br />

the district ranges between 900 mm and 1200<br />

mm with a mean temperature <strong>of</strong> 20 –250C.<br />

Central Statistical Authority (CSA) (2007)<br />

indicated that the total population <strong>of</strong> Amigna<br />

district in 2007 was 73224.<br />

Referring to land use pattern <strong>of</strong> the<br />

district, cultivated land constituted 23.62 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> the total area in the district. On the<br />

other hand, about 19 per cent <strong>of</strong> the district is<br />

covered with forest. Moreover, substantial part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the land in the district (6.86 per cent) comes<br />

under non-agricultural use (ABOARD, 2009).<br />

Sampling and Data Collection: The<br />

research design was based on a two-stage<br />

sampling procedure. In the first stage, among<br />

the 19 peasant associations found in the<br />

district, four PAs with similar agricultural<br />

production systems and fairly similar access<br />

to major road and urban centres were selected

Institutional Arrangements for Farmland <strong>Development</strong> : The Case <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia 155<br />

purposively based on information from<br />

ABOARD and other institutions found in district<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices. In the second stage, a total <strong>of</strong> 118<br />

sample households were selected randomly<br />

using probability proportional to sample size<br />

technique (Table 1).<br />

Table 1 : Number <strong>of</strong> Households and<br />

Sample Size by Peasant Associations<br />

Peasant Total number Sampled<br />

Associations <strong>of</strong> households households<br />

Bammo 621 34<br />

Gubbissa 449 25<br />

Medewelabu 667 36<br />

Dimma 412 23<br />

Grand total 2149 118<br />

Source: Own Survey, 2009.<br />

Data Analysis : An in-depth qualitative<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> selected cases was performed by<br />

looking into the specific factors that drive<br />

farmers into informal land transactions. A<br />

descriptive analysis was employed to analyse<br />

qualitative and quantitative data. The<br />

descriptive analysis such as frequency tables<br />

were used to determine institutional<br />

arrangements to get access to farmland in the<br />

study area.<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

Emerging Institutional Arrangements to<br />

Get Access to Farmland in the Study Area : Land<br />

transactions have long provided a mechanism<br />

for providing access 1 to land for those who<br />

seek it and thereby for enhancing land<br />

utilisation. There were three notable<br />

institutional arrangements to get access to<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Development</strong>, Vol. 31, No. 2, April - June : 2012<br />

farmland in the district such as administrativebased<br />

(PA allocated land and inherited land),<br />

re-emerging informal market 2 based, and<br />

informal non-market based arrangements.<br />

Majority <strong>of</strong> farm households had land through<br />

administrative based allocation (PA-land).<br />

Hence, it was the dominant institutional<br />

arrangement receiving largest share (78.1 per<br />

cent) <strong>of</strong> total land cultivated <strong>of</strong> sample<br />

respondents (Figure 2). Land rental transaction<br />

was widely practised in the district agriculture.<br />

Rented-in market was the preferred contract<br />

in the district with an average <strong>of</strong> 8.857 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> total cultivated area (Figure 2).<br />

The surface reading <strong>of</strong> the survey result<br />

also revealed that for farmers with no access<br />

or less access to rental markets and PA<br />

allocated land; there were also informal<br />

arrangements akin to the customary based<br />

systems in the district (e.g., inheritance, and<br />

borrowing). Inheritance was the second major<br />

means <strong>of</strong> acquiring land in the district as<br />

indicated by about 9 per cent <strong>of</strong> cultivated<br />

land <strong>of</strong> sample respondents (Figure 2).<br />

There were other means for land<br />

acquisition (0.72 per cent) that are particularly<br />

important for the growing ‘landless’ farmers<br />

who <strong>of</strong>ten seek land through the informal<br />

markets but constrained by lack <strong>of</strong> cash and<br />

equity capital such as oxen.<br />

They borrowed 3 land from their parents<br />

and close relatives. The foregoing discussion<br />

also revealed that the institution <strong>of</strong> marriage<br />

acts occasionally as a non-market device<br />

(borrowing) for getting access to land and pool<br />

labour, especially between landholder femaleheads<br />

and landless male labour. The remaining<br />

0.18 per cent <strong>of</strong> land was acquired through<br />

informal mortgaging.

156 Abayineh Amare Woldeamanuel, Fekadu Beyene Kenee<br />

Figure 2 : Share <strong>of</strong> Different Modes <strong>of</strong> Acquisition <strong>of</strong> Total Cultivated Farmland<br />

Source : Own Survey, 2009.<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> Land Rental Market Activity in<br />

the Study Area: From the 88 households<br />

interviewed, 35 households are involved in<br />

adjusting their operated farm size by rentingin<br />