Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Play through and download the games<br />

from <strong>Chess</strong><strong>Cafe</strong>.com in the DGT<br />

Game Viewer.<br />

The Complete<br />

DGT Product Line<br />

Fifty More Lessons<br />

Steve Goldberg<br />

<strong>50</strong> <strong>Ways</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Chess</strong>, by Steve Giddins, 2007 Gambit Public<strong>at</strong>ions Ltd, Figurine<br />

Algebraic Not<strong>at</strong>ion, Paperback, 175pp., $26.95<br />

This is an excellent follow-up <strong>to</strong> Giddins’ <strong>50</strong> Essential <strong>Chess</strong><br />

Lessons from Gambit, published in 2006. It does not include<br />

“the essential lessons” notes <strong>at</strong> the end of each game, as in<br />

the earlier book, but it does continue Giddins’ easy writing<br />

style th<strong>at</strong> emphasizes teaching major concepts with textual<br />

explan<strong>at</strong>ions r<strong>at</strong>her than via lengthy mind-numbing<br />

vari<strong>at</strong>ions. Giddins is a FIDE Master who understands the<br />

subtle elements th<strong>at</strong> separ<strong>at</strong>e class players from master<br />

players.<br />

Each game typically is spread over two or three pages, with a<br />

sufficient number of diagrams so th<strong>at</strong> most readers will be<br />

able <strong>to</strong> review the game notes without the need for a<br />

chessboard. It might still be advisable, however, <strong>to</strong> play over<br />

the games either on a physical board or using chess software.<br />

I found th<strong>at</strong> my <strong>Chess</strong>Base d<strong>at</strong>abase already contained many of the games from <strong>50</strong> <strong>Ways</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>Win</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Chess</strong>.<br />

The book is divided in<strong>to</strong> seven sections, each emphasizing a different fe<strong>at</strong>ure, as the Table of<br />

Contents shows:<br />

● Section 1: Attack and Defence<br />

● Games 1-8<br />

● Section 2: Opening Play<br />

● Games 9-12<br />

● Section 3: Structures<br />

● Games 13-28<br />

● Section 4: Them<strong>at</strong>ic Endings<br />

● Games 29-33<br />

● Section 5: Other Aspects of Str<strong>at</strong>egy<br />

● Games 34-43<br />

● Section 6: Endgame Themes<br />

● Games 44-48<br />

● Section 7: Psychology in Action<br />

● Games 49-<strong>50</strong><br />

More specifically, some of the issues Giddins covers include:

● The danger of a king trapped in the center<br />

● Opposite-side castling<br />

● Attacking weak color complexes<br />

● Exploiting weak opening play<br />

● Principle of two weaknesses<br />

● Pawn structure concepts<br />

● Endgame structures resulting from opening play<br />

● Exploiting the bishop-pair<br />

Game #6, from the Attack and Defense section, is Topalov-Kasparov, Euwe Memorial,<br />

Amsterdam 1995. It aptly demonstr<strong>at</strong>es Giddins’ lucid explan<strong>at</strong>ions (not all of his notes are<br />

shown):<br />

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.f3 Be7 8.g4 0-0 9.<br />

Qd2 a6 10.0-0-0<br />

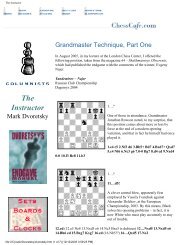

Via a Taimanov move-order, we have<br />

transposed in<strong>to</strong> a typical Najdorf/<br />

Scheveningen Sicilian position. White’s setup,<br />

with Be3, Qd2, 0-0-0 and f3, is known as<br />

the English Attack, having been developed<br />

by the English GMs Nunn, Chandler and<br />

Short during the 1980s. It is a very direct<br />

and n<strong>at</strong>ural plan. White castles queenside,<br />

and as is typical of such opposite-castling<br />

positions, he throws his kingside pawns up<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>at</strong>tack the enemy king. Black, meanwhile,<br />

uses his queenside pawns and the half-open<br />

c-file <strong>to</strong> counter<strong>at</strong>tack against White’s king.<br />

Vic<strong>to</strong>ry goes <strong>to</strong> he who manages <strong>to</strong><br />

prosecute his <strong>at</strong>tack the more vigorously, with gre<strong>at</strong> accuracy being demanded of both<br />

players.<br />

10…Nxd4<br />

Black wishes <strong>to</strong> play …b5, which is impossible <strong>at</strong> once because of the undefended<br />

knight on c6, hence this exchange. He could instead defend the knight by 10…Qc7,<br />

but it is not yet clear th<strong>at</strong> c7 is the best square for the black queen. Likewise,<br />

defending the knight by 10…Bd7?! would be <strong>to</strong>o passive, since the bishop is poorly<br />

placed on d7, being both inactive itself, and also depriving Black’s king’s knight of<br />

the retre<strong>at</strong>-square on d7.<br />

11.Bxd4 b5!<br />

Continuing with his active play on the<br />

queenside. Several previous games had seen<br />

Black preface this move with 11…Nd7, but<br />

Kasparov’s choice is more energetic. The<br />

point of 11…Nd7 is th<strong>at</strong> after Kasparov’s<br />

11…b5, White could now play 12.Bxf6.<br />

Clearly, it would be bad <strong>to</strong> play 12…gxf6?,<br />

exposing Black’s king, and after 12…Bxf6,<br />

White can win a pawn by 13.Qxd6.<br />

However, Kasparov appreci<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> Black<br />

would then have excellent compens<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

after 13…Qa5!. This type of pawn sacrifice<br />

is a common theme in the Sicilian, and

usually offers Black good counterplay. This<br />

particular version of it is especially good, as White would have serious problems<br />

meeting the thre<strong>at</strong>s of 14…Bxc3 and 14…b4, especially as 14.e5 is met by 14…Bg5+<br />

15.Kb1 b4, thre<strong>at</strong>ening 16…Rd8.<br />

12.Kb1<br />

As noted above, opposite-castling positions are usually all about a race between the<br />

opposing <strong>at</strong>tacks, with time being very much of the essence. For this reason, the textmove<br />

may appear a little slow, but it is usually necessary sooner or l<strong>at</strong>er. Black will<br />

follow up with some combin<strong>at</strong>ion of …b4 and …Qa5, after which the king move will<br />

generally be necessary <strong>to</strong> defend the a-pawn. In addition, once a black rook comes <strong>to</strong><br />

the c-file, the king will feel uncomfortable on c1.<br />

12…Bb7 13.h4 Rc8 14.g5 Nd7<br />

15.Rg1!?<br />

This is a critical moment. Both sides have<br />

deployed their forces logically and started<br />

their <strong>at</strong>tacks, and White must now decide<br />

how <strong>to</strong> continue. Clearly, White would like<br />

<strong>to</strong> play 15.h5, but this is impossible because<br />

the g5-pawn would hang, and hence the textmove.<br />

However, removing the rook from the<br />

h-file is not ideal, since in many lines, after a<br />

l<strong>at</strong>er h5 and g6, the h-file may well be<br />

opened. One typical idea for White here is<br />

the pawn sacrifice 15.g6, aiming <strong>to</strong> open<br />

lines quickly after 15…hxg6 16.h5, and if<br />

then 16…g5, 17.h6 gives White a winning <strong>at</strong>tack. In all likelihood, Black would not<br />

have captured on g6, but would have answered 15.g6 with 15…b4 16.gxh7+ Kh8.<br />

Allowing an enemy pawn <strong>to</strong> stand in front of one’s king like this is a standard<br />

defensive technique, which makes it rel<strong>at</strong>ively difficult for the <strong>at</strong>tacker <strong>to</strong> get <strong>at</strong> the<br />

black king. Even so, this may have been a better way for White <strong>to</strong> continue, since<br />

after the text-move, he soon loses the initi<strong>at</strong>ive.<br />

15…b4!<br />

Kasparov continues <strong>to</strong> prosecute his queenside play with the utmost vigour. Some<br />

earlier games had seen Black play 15…Ne5 followed by 16…Nc4. Kasparov’s plan is<br />

more straightforward, driving away the defending knight on c3. As well as furthering<br />

Black’s <strong>at</strong>tack on the white king, this has another point – <strong>to</strong> weaken White’s control<br />

of the d5-square. In such Sicilian positions, one of Black’s key str<strong>at</strong>egic ideas is <strong>to</strong><br />

achieve the break …d5 in favourable circumstances. As we shall see l<strong>at</strong>er in this<br />

game, such a break can release the potential energy of Black’s pieces, such as the<br />

bishop on e7, with gre<strong>at</strong> effect.<br />

16.Ne2 Ne5<br />

17.Rg3?!<br />

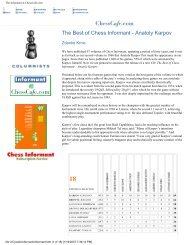

After this, Black’s initi<strong>at</strong>ive soon grows <strong>to</strong><br />

decisive proportions. Probably the best<br />

defence was 17.Bxe5 dxe5 18.Qxd8 Rfxd8,<br />

although in the resulting endgame, Black

would have a clear advantage, with his<br />

bishop-pair and control of the dark squares.<br />

17…Nc4 18.Qc1 e5!<br />

This structural change is very common in<br />

Sicilian positions. White’s pieces are in no<br />

position <strong>to</strong> exploit the weakened d5-square,<br />

and so Black is able <strong>to</strong> expand his central<br />

influence, without any downside.<br />

19.Bf2 a5<br />

It is very obvious th<strong>at</strong> White has been<br />

outplayed in the race between the two<br />

<strong>at</strong>tacks. His pieces are very awkwardly<br />

placed on the kingside, whereas Black’s<br />

position is a model of harmony. With this<br />

move, Black prepares <strong>to</strong> activ<strong>at</strong>e his lightsquared<br />

bishop along the f1-a6 diagonal, as well as setting up …a4 and …b3,<br />

breaking open White’s king position. White’s <strong>at</strong>tack on the kingside, meanwhile, is<br />

stymied.<br />

20.Bg2 Ba6 21.Re1<br />

21…Na3+ was a thre<strong>at</strong>.<br />

21…a4 22.Bh3 Rc6<br />

Now 23…b3 is thre<strong>at</strong>ened.<br />

23.Qd1<br />

23…d5!<br />

This classic central breakthrough decides m<strong>at</strong>ters in short order. Now all Black’s<br />

pieces spring in<strong>to</strong> action, and White’s back rank proves weak. Now 24.Qxd5? drops<br />

the queen after 24…Rd6 25.Qc5 Rd1+.

24.exd5 Rd6 25.f4<br />

25…Rxd5 26.Rd3<br />

The pressure down the open d-file is<br />

irresistible. 26.Qc1 loses <strong>to</strong> 26…Nd2+ 27.<br />

Ka1 Ne4 28.Rf3 Bxe2.<br />

26…Na3+!<br />

The final blow, demolishing White’s<br />

resistance.<br />

27.bxa3 Bxd3 28.cxd3 Rxd3 0-1<br />

The bishop on h3 is lost. A splendid example<br />

of how such a position can collapse if White<br />

loses the initi<strong>at</strong>ive. As Kasparov gleefully<br />

pointed out <strong>at</strong> the time, one unusual fe<strong>at</strong>ure<br />

of the game is th<strong>at</strong> Black’s queen never<br />

moved from its starting position on d8!<br />

There are fifty such games in this collection, each with something a little different <strong>to</strong><br />

contribute <strong>to</strong> the reader’s base of knowledge. In addition, each of the seven sections is<br />

introduced with illumin<strong>at</strong>ing comments. For example, in the Section 2 (“Opening Play”),<br />

Giddins clarifies th<strong>at</strong> “Many players make the mistake of thinking th<strong>at</strong> ‘knowing’ an opening<br />

just involves memorizing long sequences of moves, by rote. In reality, it is developing a<br />

deep understanding of the types of middlegame and endgame <strong>to</strong> which the opening leads,<br />

which is the key <strong>to</strong> successful play in any opening.” Giddins then presents a well-chosen<br />

game <strong>to</strong> drive home this point.<br />

<strong>50</strong> <strong>Ways</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Chess</strong> is another in a long line of Gambit books th<strong>at</strong> are ideally suited <strong>to</strong><br />

any class player. Giddins’ commentary is appropri<strong>at</strong>e for the lower-r<strong>at</strong>ed player who may<br />

simply want <strong>to</strong> know Why didn’t Black take the pawn?, and for the higher-r<strong>at</strong>ed player who<br />

wants <strong>to</strong> further refine his positional understanding. This is not an opening compendium, but<br />

the astute reader will deepen his appreci<strong>at</strong>ion for the various nuances of a number of<br />

openings, and more importantly, will better realize how specific openings lead <strong>to</strong> certain<br />

middlegame structures, and how these middlegame structures lead <strong>to</strong> recognizable endgame<br />

positions. Giddins even includes two games <strong>to</strong> illustr<strong>at</strong>e intangible but not uncommon<br />

psychological fac<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>at</strong> play.<br />

The <strong>at</strong>tractive cover and the clear print and diagrams are easy on the eyes, and Giddins’<br />

endless supply of insights and comfortable writing style makes this an excellent addition <strong>to</strong><br />

any player aspiring <strong>to</strong> gre<strong>at</strong>er heights.

Order <strong>50</strong> <strong>Ways</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Chess</strong><br />

by Steve Giddins<br />

[<strong>Chess</strong><strong>Cafe</strong> Home Page] [Book Review] [Columnists]<br />

[Endgame Study] [The Skittles Room] [Archives]<br />

[Links] [Online Books<strong>to</strong>re] [About <strong>Chess</strong><strong>Cafe</strong>.com] [Contact Us]<br />

© 2008 Cyber<strong>Cafe</strong>s, LLC. All Rights Reserved.<br />

"<strong>Chess</strong><strong>Cafe</strong>.com®" is a registered trademark of Russell Enterprises, Inc.