THE SOPRANO TROMBONE HOAX* - (ASU) Trombone Studio

THE SOPRANO TROMBONE HOAX* - (ASU) Trombone Studio

THE SOPRANO TROMBONE HOAX* - (ASU) Trombone Studio

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

138<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>SOPRANO</strong> <strong>TROMBONE</strong> HOAX *<br />

Howard Weiner<br />

The soprano or discant trombone is the stepchild of the trombone family. Developed<br />

late in comparison to the other trombones, it hardly found employment by composers of<br />

stature; only Johann Sebastian Bach called for a soprano trombone in three of his cantatas.<br />

By chance and through the absence of historical knowledge in following generations, however,<br />

Heinrich Schütz, Christoph Willibald Gluck, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were<br />

also brought into connection with this instrument. Thus, in the nineteenth and twentieth<br />

centuries various false “facts” concerning the soprano trombone have made the rounds. In<br />

concentrated form, they are to be found in Posaune, the eighth volume of Hans Kunitz’<br />

series Die Instrumentation, first published in 1959 by Breitkopf & Härtel. 1 Kunitz, however,<br />

did not content himself with a simple retelling of the usual legends, but added his own<br />

embellishments. In spite of the obvious source-historical problems in Kunitz’ book, other<br />

writers have apparently considered it to be credible, repeatedly employing it as a source for<br />

their own publications. More recently, additional works betraying Kunitz’ influence have<br />

appeared, including the article “Posaune” in the new MGG. 2 Besides pricking the bubble<br />

of Kunitz’ hoax, I will also present early references and sources that may help us form a<br />

new, more accurate picture of the soprano trombone.<br />

In attempting to verify Kunitz’ information, one is immediately confronted by a lack<br />

of source references. The reason for this is simple: Little of what Kunitz writes about the<br />

history of the trombone is based on historical fact. Let us take, for example, the very first<br />

sentence of his version of the soprano trombone’s “historical development”:<br />

The soprano trombone, also called discant trombone, has belonged to the<br />

trombone family from the very start, thus at least since the beginning of the<br />

sixteenth century. 3<br />

There is no evidence to support this assertion. Neither graphic depictions nor written<br />

descriptions of soprano trombones exist from the sixteenth century. Instruments as well<br />

as a dedicated repertoire are likewise completely lacking. But even where Kunitz’ source is<br />

evident, one has to be very careful:<br />

Since the beginning of the seventeenth century, one differentiated between<br />

the following types of trombone:<br />

1. <strong>Trombone</strong> Soprano = Soprano (Discant) <strong>Trombone</strong><br />

2. <strong>Trombone</strong> Alto also called Trombonino or Tromboncino = Alto <strong>Trombone</strong><br />

3. <strong>Trombone</strong> Tenore also called Gemeine Rechte Posaun or Tuba minor = Tenor<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong>

4. <strong>Trombone</strong> Basso also called <strong>Trombone</strong> grande or <strong>Trombone</strong> majore or Tuba<br />

major = Bass <strong>Trombone</strong>, Quart <strong>Trombone</strong>, Quint <strong>Trombone</strong><br />

5. <strong>Trombone</strong> doppio also called Oktavposaune or Tuba maxima = Contrabass<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> 4<br />

139<br />

Kunitz does not cite a source for this list, but the terminology points to Michael Praetorius’<br />

Syntagma Musicum, 5 this, of course, being the only early seventeenth-century source<br />

that provides such an itemization. The following table shows the similarities and, more<br />

importantly, the differences:<br />

Praetorius<br />

1. Alt oder Discant Posaun<br />

Trombino<br />

Trombetta picciola<br />

2. Gemeine rechte Posaun<br />

Tuba minor<br />

Trombetta<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> piccolo<br />

3. Quart-Posaun<br />

Trombon grande<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> majore<br />

Tuba major<br />

Quint-Posaun<br />

4. Octav-Posaun<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> doppio<br />

Tuba maxima<br />

la trombone all Ottava basso<br />

WEINER<br />

Kunitz<br />

1. <strong>Trombone</strong> Soprano<br />

Sopranposaune<br />

Diskantposaune<br />

2. <strong>Trombone</strong> Alto<br />

Trombonino<br />

Tromboncino<br />

Altposaune<br />

3. <strong>Trombone</strong> Tenore<br />

Gemeine Rechte Posaun<br />

Tuba minor<br />

Tenorposaune<br />

4. <strong>Trombone</strong> Basso<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> grande<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> majore<br />

Tuba major<br />

Baßposaune<br />

Quartposaune<br />

Quintposaune<br />

5. <strong>Trombone</strong> doppio<br />

Oktavposaune<br />

Tuba maxima<br />

Kontrabaßposaune<br />

As one can see, Kunitz’ designations for tenor, bass, and contrabass trombones are largely<br />

identical to those given by Praetorius. But something strange has happened with Praetorius’

140<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Alt oder Discant Posaun. The terms no longer agree, and one instrument has become two:<br />

The “alto or discant trombone” has become an “alto and a discant trombone.” In this manner,<br />

the four types of trombone specified by Praetorius become five in Kunitz.<br />

Since Kunitz is not the only one who has had trouble interpreting Praetorius correctly,<br />

it may be worthwhile to examine the original. On page 31 of the second volume of<br />

Syntagma Musicum, we read:<br />

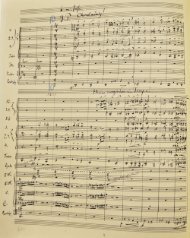

Posaun ... deren seynd viererley Arten oder Sorten [<strong>Trombone</strong>s ... of which<br />

there are four types or sorts] (Figure 1).<br />

Figure 1<br />

Michael Praetorius, Syntagma musicum II (Wolfenbüttel, 1619), p. 31.<br />

On page 20 a chart of ranges shows “a complete set”:<br />

Ein ganz Accort. Tromboni: Posaunen. 1. Sort: Octav Posaun. 2. Sort: Quart<br />

Pos[aun]. 3. Sort: Gemeine oder rechte Posaun. 4. Sort: Alt Pos[aun] (Figure 2)

And on page 13:<br />

WEINER<br />

Figure 2<br />

Praetorius, Syntagma musicum II, p. 20.<br />

Ein Accort od’ Stimmwerk von Instrumenten, helt in sich etliche unterschiedliche<br />

Sorten: Nemlich ... Viererley (Sorten / die) Posaunen: [A set or<br />

whole consort of instruments consists of various sorts: Namely ... sets with<br />

four sorts / the trombones:] Alt Posaun, Gemeine rechte Posaun, Quart<br />

Posaun, Octav Posaun (Figure 3).<br />

141

142<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Figure 3<br />

Praetorius, Syntagma musicum II, p. 13.

143<br />

It should also be noted that the “Theatrum Instrumentorum” appended to Syntagma Musicum<br />

II contains illustrations of only these four types of trombone. In short, the soprano<br />

trombone is neither mentioned nor depicted in Praetorius, and is also not to be found in<br />

any other source from the beginning of the seventeenth century. 6<br />

This, however, does not stop Kunitz from blaming Praetorius for the instrument’s lack<br />

of use:<br />

The soprano trombone, also called discant trombone, has belonged to the<br />

trombone family from the very start, thus at least since the beginning of the<br />

sixteenth century. After a relatively short time, however, it fell into a sort<br />

of “disrepute” among instrumentalists and, as a result, also in the specialist<br />

literature, something that has not been rectified to the present day. As early as<br />

1618 Praetorius declared that the soprano trombone was “insufficient in sound<br />

and technique.” And this judgement, which is found in such an important<br />

and authoritative work as his “Syntagma Musicum,” has been uncritically<br />

accepted throughout all the following centuries, and indeed, not only in the<br />

specialist literature, but also by composers and instrumentalists. 7<br />

And in another passage,<br />

WEINER<br />

The reason given by Praetorius, that the soprano trombone was not equal to the<br />

other trombones in sound and technique, cannot be considered correct. 8<br />

Apart from the fact that Praetorius was not talking about the soprano trombone at all,<br />

this interpretation is rather arbitrary. Actually, Praetorius’ original text reads quite a bit<br />

differently (Figure 1):<br />

Alto or discant trombone: ... with which a melody can be played very well<br />

and naturally, although the sound in such a small corpus is not as good as<br />

when the tenor trombone, with good embouchure and practice, is played<br />

in this high register. 9<br />

One will also search in vain for the “judgement” that the soprano trombone was “insufficient<br />

in sound and technique”—a “judgement” that Kunitz puts into Praetorius’ mouth.<br />

This quotation actually stems from Hermann Eichborn, and is found on page 23 of his<br />

book Die Trompete in alter und neuer Zeit, published in 1881. 10<br />

But Kunitz also identifies other guilty parties:<br />

The real reason for its infrequent use undoubtedly lay in the lack of ability<br />

and readiness on the part of musicians to occupy themselves with the<br />

instrument. 11

144<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Now the “truth” comes out! The musicians are the villains in this piece. They refused to play<br />

an instrument for which the composers had not written any music, an instrument that did<br />

not even exist for much of the period in question. “The indolence and insufficient technical<br />

ability” 12 of these musicians is hardly to be believed. And as if that were not enough,<br />

As the cornett, during the Renaissance technically improved, but still very<br />

mediocre in terms of sound quality, came more and more into use during<br />

the Baroque period, instrumentalists often made it easy for themselves and<br />

simply employed the cornett, with its easy-to-play fingering system, instead<br />

of the difficult-to-use soprano trombone. 13<br />

It apparently rankles Kunitz that another instrument occupies the position he would liked<br />

to see occupied by the soprano trombone:<br />

In those cases in which the cornett is employed as the highest voice of a closed<br />

trombone group, it is in fact a makeshift solution [italics original]. 14<br />

He even speaks of<br />

the vulgar, base, and dull sound of the primitive cornett. 15<br />

And when Kunitz refers to the cornett as an instrument that has been “declared unusable<br />

for art music,” as he does on page 798, one has only to turn back one page to determine<br />

that it was Kunitz himself who declared,<br />

In view of all this, the cornett cannot at all be considered an instrument<br />

appropriate for art music. 16<br />

We do not want or need to defend the honor of the cornett here. The relevant historical<br />

sources, not to mention present-day performers such as Bruce Dickey, Jean Tubéry, and<br />

William Dongois, give eloquent testimony as to the qualities and possibilities of this instrument.<br />

17 The cornett came upon the scene almost two hundred years before the soprano<br />

trombone, and was demonstrably required and employed as the highest voice of the “closed<br />

trombone group.” The cornett did not supplant the soprano trombone, nor did the soprano<br />

trombone supplant the cornett.<br />

Nevertheless, an instrument has to have something to play, so Kunitz attempts to<br />

conjure up a repertoire:<br />

The great masters, such as Schütz, Bach, Gluck, and Mozart employed the<br />

soprano trombone in the four-part trombone group usual at that time, and<br />

indeed until the end of the eighteenth century. 18

With this statement Kunitz calls up four of the most important composers of the seventeenth<br />

and eighteenth centuries as witnesses for his hoax.<br />

And<br />

WEINER<br />

The soprano trombone was initially a full-fledged member of the trombone<br />

group, as can be recognized from the works of Heinrich Schütz, in which<br />

the closed, four-part trombone group, made up of soprano, alto, tenor, and<br />

bass trombones, is to be found. 19<br />

As already stated ... the four-part group with the soprano trombone still<br />

predominated in the works of Heinrich Schütz. 20<br />

145<br />

But just how “predominant” is the “four-part trombone group” in the works of Heinrich<br />

Schütz? Schütz called for trombones in thirty-two works, of which nineteen have a threepart,<br />

and only seven a four-part trombone group. And none of these seven works require<br />

a four-part trombone group with soprano, alto, tenor, and bass trombones.<br />

For Kunitz, the combination of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass clefs is the “usual manner<br />

of notation” 21 for the “centuries-old, traditional, pure four-part trombone group.” 22 My<br />

research has turned up seventy-three four-part trombone groups in sixty-eight instrumental<br />

and vocal works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with a total of fifteen different<br />

clef combinations. The most frequent was the combination alto-tenor-tenor-bass, which<br />

appeared twenty-three times. Kunitz’ “usual manner of notation” did not turn up at all.<br />

It should be noted, by the way, that one cannot infer the intended instrument simply<br />

from the clef of the part. A part in alto clef, for instance, does not necessarily demand an alto<br />

trombone. Much more important is the tessitura. For example, although many of Schütz’<br />

“high” trombone parts are notated in alto clef, all but a few remain within the range given<br />

by Praetorius as normal for the tenor trombone—E - a’ (See Figure 2).<br />

An ensemble of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass trombones, notated in Kunitz’ “usual”<br />

clef combination, is found in three cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach: Ach Gott, vom Himmel<br />

sieh’ darein (BWV 2), Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis (BWV 21) and Aus tiefer Not schrei’<br />

ich zu dir (BWV 38). Strangely only Cantata 2 attracts Kunitz’ attention; Cantatas 21 and<br />

38 are simply ignored. Instead, Kunitz attempts to smuggle the cantatas Sehet, welch’ eine<br />

Liebe (BWV 64) and Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt (BWV 68) into the canon of works with<br />

soprano trombone, although the highest parts of these works are labeled cornettino and<br />

cornetto, respectively. Kunitz’ reason?<br />

Bach is to be considered one of the last representatives of the pure four-part<br />

trombone group, employing the real trombone family, reaching from the<br />

soprano to the bass instruments, whose usual notation: [soprano, alto, tenor,<br />

bass clefs] also predominates in his scores where he employs trombones, even<br />

when he sometimes ... labels the highest part with “cornetto.” 23

146<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Figure 4<br />

J.S. Bach, Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt (BWV 69), autograph parts, Corno (mvt. 1) and<br />

Cornetto (mvt. 5). (Leipzig, Bach-Archiv).

WEINER<br />

147<br />

If we apply Kunitz’ own criterion, however, we would automatically have to disqualify the<br />

highest part of Cantata 68 as a soprano trombone part. This autograph cornett part is not<br />

in soprano, but treble clef (Figure 4). The highest part of Cantata 64, labeled cornettino,<br />

also lacks a characteristic typical of a Bach trombone part: unlike all of Bach’s authenticated<br />

trombone parts, this one is not transposed. 24<br />

But why does Kunitz ignore Cantatas 21 and 38, even though both offer authentic<br />

soprano trombone parts?<br />

It should be noted that the “cornetto” parts in Bach’s cantatas were indeed<br />

written for the Stadtpfeifer cornett in those cases in which they support,<br />

with simple sustained tones, the cantus firmus of the choir, without organic<br />

relationship to the trombone parts. 25<br />

Accordingly, in Kunitz’ view the cornetto and soprano trombone parts with a cantus firmus<br />

or simple chorale melody are actually cornett parts, and the cornetto and cornettino parts<br />

with numerous fast notes are actually soprano trombone parts!<br />

In any case, especially at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the instrumentalists’<br />

arbitrary practice of simply substituting the cornett for the<br />

specified, but technically more difficult to control, soprano trombone had<br />

become so widespread that not only was a genius like Johann Sebastian Bach<br />

forced to make concessions in order to secure a performance of his cantatas,<br />

but at times the soprano trombone itself was designated as “cornetto.” 26<br />

These absurd assertions surely do not require comment. The last of these, however, comes<br />

up again in connection with Christoph Willibald Gluck:<br />

Thus Gluck too made use of the soprano trombone under the name Cornetto<br />

in the Italian version of the score of his Orpheus. 27<br />

Exceptionally, Kunitz cites a seemingly reliable source here, namely Hector Berlioz, who<br />

in his Grand Traité d’Instrumentation from 1843 did in fact state:<br />

Only Gluck, in the Italian score of Orfeo, wrote for the soprano trombone,<br />

under the name Cornetto. 28<br />

I must admit that I was rather astonished when I first read this. But Berlioz too was only<br />

human, and humans can err. In 1862, nineteen years after his treatise appeared, Berlioz<br />

published an essay about the 1859 production of Orfeo at the Théâtre Lyrique, in which<br />

he wrote,<br />

At the time in which Gluck wrote Orfeo for Vienna, a wind instrument

148<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

was in use that even today is employed in some churches in Germany to<br />

accompany the chorales, and is called the cornetto. It is made of wood, has<br />

a conical bore and is played with a mouthpiece of brass or horn similar to<br />

that of a trumpet.<br />

In the religious funeral ceremony held at Euridice’s grave, in the first act of<br />

Orfeo, Gluck combined the cornetto with three trombones to accompany<br />

the four parts of the choir. 29<br />

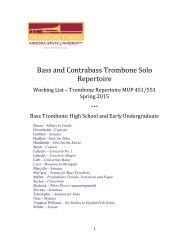

And the soprano trombone sneaked out the stage door. At first glance, Mozart’s Mass in C<br />

Minor, K. 427, would also seem to provide evidence for the use of the soprano trombone.<br />

But when Kunitz claims that Mozart “explicitly labeled the trombone parts as Posaune I<br />

- IV,” 30 he is again fantasizing. In his autograph score, Mozart signaled where the trombones<br />

were to play and pause by means of appropriate indications in the vocal parts. Only in the<br />

first movement, Kyrie, are there three such markings in the soprano part: in measure 6,<br />

tro: (Figures 5 and 6), in measure 27 Senz: trom:, and in measure 86 senz: tr:. According<br />

Figure 5<br />

W.A. Mozart, Mass in C Minor (K. 427), autograph score, fol. 1 r (Kyrie) (Staatsbibliothek<br />

zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv).

to the editors of the Neue Mozart Ausgabe,<br />

WEINER<br />

Figure 6<br />

Detail of Figure 5.<br />

All indications for the participation of the trombones in the Kyrie were<br />

added to the autograph by Mozart only at a later point in time. This can be<br />

discerned at numerous places by the placement of the respective annotations<br />

or through the superscription over already existing characters. It is possible<br />

that Mozart performed this process rather mechanically and did not take<br />

care how often and in which part he placed the entries. 31<br />

149<br />

There is, however, weighty evidence for Mozart’s actual intentions. In the Sanctus, for example,<br />

Mozart himself wrote the indications <strong>Trombone</strong> Imo, <strong>Trombone</strong> 2do, and <strong>Trombone</strong> 3tio,<br />

corresponding to the alto, tenor, and bass vocal parts, respectively (Figures 7 and 8). Figure<br />

9 shows a brace from the Hosanna, marked 3 Tromboni, this too in Mozart’s hand.<br />

And last but not least, we have the <strong>Trombone</strong> Imo part from the first performance of the<br />

Mass in Salzburg in 1783 (Figure 10). This part is in the hand of Salzburg court musician<br />

Felix Hofstätter, who frequently copied music for the Mozart family. As can be seen, this<br />

part too corresponds to the alto voice line. There is obviously no place here for a soprano<br />

trombone. 32

150<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Figure 7<br />

W.A. Mozart, Mass in C Minor (K. 427), autograph score, fol. 69 r (Sanctus).<br />

Figure 8<br />

Detail of Figure 7.

WEINER<br />

Figure 9<br />

W.A. Mozart, Mass in C Minor, K. 427, autograph score, fol. 70 v (detail of Hosanna)<br />

151<br />

With this we have uncovered the main points of the hoax and exposed Kunitz’ history<br />

of the soprano trombone as a fabrication. Under normal circumstances, one would<br />

certainly dismiss Kunitz’ book as a bizarre mixture of fantasy and fact (with the former<br />

greatly outweighing the latter) in the guise of a serious treatment of the trombone’s history<br />

and usage. Yet Kunitz has managed to become an important source of “knowledge”<br />

about the soprano trombone, offering twenty-two pages of information on this instrument<br />

to those willing to overlook some very obvious flaws. Given the almost complete lack of<br />

documentary evidence concerning the soprano trombone, it is perhaps not surprising that<br />

many scholars and players have been willing to take Kunitz’ information at face value. Be<br />

that as it may, by refuting the myths that until now have obscured our view of the soprano<br />

trombone, I hope to have created a much-needed tabula rasa as starting point for serious<br />

research into the instrument’ history. To this end, I should also like to offer the early references<br />

and sources that I came upon while researching the present article.<br />

The earliest piece of evidence is an actual instrument: A soprano trombone by Christian<br />

Kofahl, dated 1677, is the earliest known instrument of this type (Figure 11). 33

152<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Figure 10<br />

W.A. Mozart, Mass in C Minor (K. 427), <strong>Trombone</strong> I mo part of the original performance<br />

material, Salzburg, 1783. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Heilig Geist<br />

Kloster, Augsburg.)

WEINER<br />

Figure 11<br />

Soprano trombone by Christian Kofahl, Grabow (Germany), 1677 (Kremsmünster,<br />

Musikinstrumentenmuseum Schloss Kremsegg; photo by Lars Laubhold).<br />

153<br />

Several printed sources mention the soprano trombone. In his Abbildung der Gemein-<br />

Nützlichen Haupt-Stände (Regensburg, 1698), Christoff Weigel wrote that “the trombones<br />

are also made in various sizes, namely soprano, alto, tenor, bass, and quart trombones.” 34<br />

In a similar work, Johann Samuel Halle’s Werkstäte der heutigen Künste (Brandenburg and<br />

Leipzig, 1764), it is stated that “there are four trombones; soprano, alto, tenor, and quart<br />

or quint trombones.” 35 A third source comes from Norway: The Musikaliske Elementer by<br />

Johann Daniel Berlin was published in 1744 in Trondheim. In the chapter “On playing<br />

the cornett,” Berlin wrote,<br />

The cornett ... is generally used in loud and splendid music, and in accompaniment<br />

or together with trombones; it is employed on the highest part<br />

when there is no soprano trombone.<br />

§2. However, even in such a case [sic!], one still prefers the cornett to the<br />

soprano trombone, because the cornett can be played gracefully. 36<br />

Two manuscript sources from Leipzig are of interest to us here. Shortly after assuming<br />

the position of Thomaskantor in 1701, Johann Kuhnau submitted two inventories to<br />

the Leipzig town council, itemizing the music and instruments in the possession of the<br />

Thomasschule, the Thomaskirche, and the Nicolaikirche. In the second inventory, dated 22<br />

May 1702, he stated,

154<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Since the trombones are good church instruments, the ones here, however,<br />

very old and beat up and therefore not suitable to be used, it would be<br />

necessary to acquire new ones, and namely a pair of soprano trombones, in<br />

their stead. 37<br />

Later, another hand added, “ist geschehen” (“it has been done”). 38<br />

Almost seventy years later, on 2 August 1769, Johann Friedrich Doles, Bach’s pupil<br />

and successor as Thomaskantor (served 1756-1789), evaluated the playing of a candidate<br />

for the position of Stadtpfeifer:<br />

The 1st Kunstgeiger Pfaffe... 3) The simple chorale on the soprano, alto, tenor,<br />

and bass trombone (the last of which none of his colleagues plays better than<br />

he and his brother, and which requires good lungs) he played well. 39<br />

The earliest surviving works with soprano trombone parts also come from Leipzig, namely<br />

the three cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach mentioned above. The above-mentioned Doles<br />

wrote twenty-six so-called figurierte Choräle and a cantata that require four trombones, with<br />

a soprano trombone apparently doubling the chorale melody in the highest voice. 40<br />

Two Passions by Georg Philipp Telemann have soprano trombone parts, although<br />

not in their original versions. A St. John Passion from 1761 and a St. Mark Passion from<br />

1767 were adapted in 1793 and 1788, respectively, by Telemann’s grandson Georg Michael<br />

Telemann for performances in Riga, where he was employed as church music director. 41<br />

And finally, there is a sizable repertoire of wind music with parts for soprano trombone,<br />

which comes from the Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine or Moravian Brethren. In Europe and<br />

in America the Moravians frequently employed a four-part trombone group with soprano,<br />

alto, tenor, and bass trombones. Among the collections of music from the second half of<br />

the eighteenth century that have come down to us are two from the Moravian community<br />

in Zeist, Holland. The first is a chorale book in score with 169 chorales for trombone<br />

quartet; 42 the second, preserved in part books, contains twenty-nine pieces for trombone<br />

quartet. 43 In the holdings of the Moravian Music Foundation in Winston-Salem, North<br />

Carolina, there is a manuscript containing six sonatas for trombone quartet written by a<br />

composer named Cruse 44 (Figure 12) and a set of trombone chorale books dating from<br />

around 1790 45 (Figure 13). A similar set of trombone chorale books is also preserved in<br />

the Brethren’s House, Lititz, Pennsylvania. 46<br />

Thus the soprano trombone apparently first appeared during the last quarter of the<br />

seventeenth century and found its primary usage in the Protestant Church, where it occasionally<br />

strengthened the soprano voice in the chorales. Foremost in using the instrument<br />

in this manner were the Moravians, who also developed an appropriate instrumental<br />

repertoire. In this way, the soprano trombone has led a marginal, yet honorable existence<br />

since the eighteenth century—and certainly has not deserved to have false honors heaped<br />

upon it by Hans Kunitz.

WEINER<br />

Figure 12<br />

6 Sonaten auf Posaunen die Cruse (Winston-Salem, NC, Moravian Music Foundation,<br />

SCM 261, Salem Collegium Musicum collection).<br />

155

156<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Figure 13<br />

<strong>Trombone</strong> chorale book (1790s?), soprano trombone part (Winston-Salem, NC, Moravian<br />

Music Foundation, SCM 261, Salem Collegium Musicum collection).<br />

Howard Weiner is a free-lance musician residing in Freiburg, Germany. He studied trombone<br />

with Frank Crisafulli at Northwestern University and early music at the Schola Cantorum<br />

Basiliensis.<br />

NOTES<br />

* This article is a revised version of a paper read at Toronto 2000: Musical Intersections. A Germanlanguage<br />

version appeared in the Michaelsteiner Konferenzberichte 60 (Blankenburg: Stiftung Kloster<br />

Michaelstein, 2001), pp. 67-82.<br />

1 Hans Kunitz, Die Instrumentation: Ein Hand- und Lehrbuch, vol. 8, Posaune (Leipzig: Breitkopf &<br />

Härtel, 1959). See also Hans Kunitz, Instrumenten-Brevier (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1961,<br />

2/1971).<br />

2 Works that cite Kunitz include the books The <strong>Trombone</strong> by Robin Gregory (London: Faber and<br />

Faber, 1973) and the Handbuch der Musikinstrumentenkunde by Erich Valentin (Regensburg: Gustav<br />

Bosse Verlag, 1986), the articles “Le <strong>Trombone</strong> alto” by Benny Sluchin in Brass Bulletin 61 (1988),<br />

“Strumenti a Fiato” by Georg Karstädt in the encyclopedia La Musica (Turin: Unione Tipografico-<br />

Editrice Torinese, 1966), and “Posaune” by Christian Ahrens in the new MGG (in which Ahrens at<br />

least calls some of Kunitz’ assertions into question). The Lexikon Musikinstrumente, ed. Wolfgang<br />

Ruf (Mannheim: Meyers Lexikonverlag, 1991), Reclams Musikinstrumentenführer by Ermanno Briner<br />

(Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun., 1988), and Jörg Richter’s article “Die Diskantposaune” in Brass Bul-

WEINER<br />

157<br />

letin 62 (1988) do not mention Kunitz, but the connection is clearly discernible.<br />

3 Kunitz, Posaune, p. 794. “Die Sopranposaune, auch Diskantposaune genannt, gehört von Anfang<br />

an, also spätestens seit Beginn des 16. Jahrhunderts zur Familie der Posaunen.”<br />

4 Ibid., p. 588. “Seit Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts unterschied man folgende Arten ... der<br />

Posaune:”<br />

5 Michael Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum, vol. 2 (Wolfenbüttel, 1619; rpt. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1958),<br />

pp. 32-33.<br />

6 An inventory from 1613 does mention “Zwey kleine alt oder Discant posaune” (“two small alto<br />

or discant trombones” but from the context it is obvious that, as in Praetorius, alto trombones are<br />

meant. In a later inventory (1636) of the same collection these instruments are listed as “Zwey kleine<br />

discant Posaunen.” See Ernst Zulauf, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Landgräflich-Hessischen Hofkapelle<br />

zu Cassel bis auf die Zeit Moritz des Gelehrten (Ph.D. diss., Universität Leipzig, 1902), pp. 118, 134.<br />

See also Anthony C. Baines, “Two Cassel Inventories,” Galpin Society Journal 4 (1951): 33.<br />

7 Kunitz, Posaune, p. 794. “Die Sopranposaune, auch Diskantposaune genannt, gehört von Anfang<br />

an, also spätestens seit Beginn des 16. Jahrhunderts zur Familie der Posaunen. Sie ist jedoch bereits<br />

nach verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit sowohl bei den Instrumentalisten als auch demzufolge in der<br />

Fachliteratur in eine Art ‘Verruf’ gekommen, der bis auf den heutigen Tag nicht richtiggestellt<br />

worden ist. Schon Praetorius erklärt nämlich im Jahre 1618, daß die Sopranposaune ‘an Klang und<br />

Applikatur nicht genüge’ und dieses in einem so bedeutenden und maßgebenden Werke, wie es sein<br />

‘Syntagma musicum’ war, enthaltene Urteil ist durch alle folgenden Jahrhunderte hindurch kritiklos<br />

hingenommen worden, und zwar sowohl von der Fachliteratur als auch von den Komponisten<br />

und den Instrumentalisten.”<br />

8 Ibid., p. 589. “Die hierfür von Praetorius angegebene Begründung, daß die Sopranposaune den<br />

übrigen Posaunen an Klang und Technik nicht gleichgekommen sei, kann nicht als zutreffend<br />

angesehen werden.”<br />

9 Praetorius, Syntagma II, p. 31. “Alt oder Discant Posaun: ... mit welcher auch ein Discant gar wol<br />

und natürlich geblasen werden kan: Wiewol die Harmony in solchem kleinen Corpore nicht so gut,<br />

als wenn auff der rechten gemeinen Posaun, durch guten Ansatz und Übung, ein solche höhe kan<br />

erreichet werden.”<br />

10 Hermann Eichborn, Die Trompete in alter und neuer Zeit (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1881), p.<br />

23. “an Klang und Applikatur nicht genüge.”<br />

11 Kunitz, Posaune, p. 589. “Der wirkliche Grund für ihre seltenere Verwendung lag vielmehr<br />

zweifellos in der mangelnden Fähigkeit und Bereitschaft der Spieler, sich mit diesem Instrument<br />

zu befassen.”<br />

12 Ibid., p. 796 “die Indolenz und das mangelnde technische Können.”<br />

13 Ibid., p. 795. “Als nun der in der Renaissance technisch verbesserte, jedoch klanglich nach wie<br />

vor sehr minderwertige Zink (cornetto bzw. cornettino) in der Barockzeit immer mehr in Gebrauch<br />

kam, machten es sich die Instrumentalisten vielfach leicht und verwendeten an Stelle der schwer zu<br />

bedienenden Sopranposaune einfach den infolge seines Grifflochsystems leicht spielbaren Zink.”<br />

14 Ibid., p. 795. “In derartigen Fällen also, in denen der Zink als oberste Stimme eines geschlossenen<br />

Posaunensatzes eingesetzt ist, handelte es sich um eine Verlegenheitslösung.”<br />

15 Ibid., p. 795. “den rohen und unedlen, glanzlosen Klang des primativen Zinken.”<br />

16 Ibid., p. 797. “Nach alledem ist der Zink überhaupt nicht als ein der Kunstmusik zugehörendes<br />

Instrument anzusehen.”<br />

17 See for example Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle (Paris, 1636); Giovanni Maria Artusi, Delle<br />

Imperfettioni della Moderna Musica (Venice, 1600); Girolamo Dalla Casa, Il Vero Modo di Diminuir<br />

(Venice, 1584); Johann Mattheson, Das Neu-Eröffnete Orchestre (Hamburg, 1713); Johann Mattheson,

158<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Der Vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg, 1739); Roger North (ca. 1720), Roger North on Music,<br />

ed. John Wilson (London: Novello, 1959).<br />

18 Kunitz, Posaune, p. 794. “Die großen Meister wie z.B. Schütz, Bach, Gluck und Mozart setzten<br />

die Sopranposaune jedoch in dem damals, und zwar bis Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, üblichen vierstimmigen<br />

Posaunensatz ein.”<br />

19 Ibid., p. 589. “Die Sopranposaune [war] zunächst ein vollwertiges Mitglied der Posaunengruppe,<br />

wie z.B. aus den Werken von Heinrich Schütz zu erkennen ist, in denen der geschlossene, von Sopran-,<br />

Alt-, Tenor- und Baßposaune gebildete vierstimmige Posaunensatz zu finden ist.”<br />

20 Ibid. “Wie bereits dargelegt ... herrscht in den Werken von Heinrich Schütz noch der vierstimmige<br />

Satz mit der Sopranposaune vor.”<br />

21 Ibid., p. 797. “übliche Notierungsweise.”<br />

22 Ibid., p. 798. “den seit Jahrhunderten üblichen reinen vierstimmigen Posaunensatz.”<br />

23 Ibid., p. 797. “Bach [ist] als einer der letzten Vertreter des reinen vierstimmigen Posaunensatzes<br />

unter Verwendung der echten, vom Sopran- bis zum Baßinstrument reichenden Posaunenfamilie<br />

anzusehen, dessen übliche Notierungsweise: [Sopran-, Alt-, Tenor-, Baßschlüssel] auch seine Partituren<br />

beherrscht, wo er Posaunen verwendet, wenn er auch bisweilen ... die oberste Stimme mit<br />

‘Cornetto’ bezeichnet.”<br />

24 A whole-tone transposition was necessary to bring the trombones, which were in “choir pitch,”<br />

down to the “chamber pitch” of the woodwind and string instruments. This transposition is reflected<br />

in the surviving trombone parts as well as in the organ and some of the cornett parts of the original<br />

performing material.<br />

25 Ibid., p. 808. “Zu bemerken ist noch, daß die ‘Cornetto’ Stimmen in den Kantaten Bachs in denjenigen<br />

Fällen wohl tatsächlich nur für den Stadtpfeiffer-Zink geschrieben sind, in denen sie ohne<br />

satzmäßigen Zusammenhang mit den Stimmen der Posaunen mit einfachen, gehaltenen Tönen den<br />

Cantus firmus des Chores verstärken.”<br />

26 Ibid., p. 797. “Immerhin hatte besonders zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts die eigenmächtige Gepflogenheit<br />

der Instrumentalisten, einfach den Zink an Stelle der vorgeschriebenen, aber technisch<br />

schwieriger zu bewältigenden Sopranposaune zu verwenden, eine solche Verbreitung gefunden, daß<br />

sich nicht nur ein Genie wie Joh. Seb. Bach zu Konzessionen bereitfinden mußte, um eine Aufführung<br />

seiner Kantaten überhaupt zu ermöglichen, sondern daß man bisweilen sogar die Sopranposaune<br />

selbst als ‘Cornetto’ bezeichnete.”<br />

27 Ibid., p. 798. “So setzte auch Gluck in der italienischen Fassung der Partitur seines ‘Orpheus’ ...<br />

die Sopranposaune unter der Bezeichnung ‘Cornetto’ ein.”<br />

28 Hector Berlioz, Grand Traité d’Instrumentation et d’Orchestration modernes (Paris, 1843), p. 199. “Gluck<br />

seul, dans sa partition italienne d’Orfeo, a écrit le <strong>Trombone</strong> soprano sous le nom de Cornetto.”<br />

29 Hector Berlioz, “L’Orfée de Gluck,” A travers chants, Ètudes musicales, adorations, boutades et critiques<br />

(Paris 1862), pp. 110-11. “Il y avait, à l’époque où Gluck ècrivit l’Orfeo à Vienne, un instrument<br />

à vent dont on se sert encore aujourd’hui dans quelques églises d’Allemagne pour accompagner les<br />

chorals, et qu’il nomme cornetto. Il est en bois, percè de trous, et se joue avec une embouchure de<br />

cuivre on de corne semblable à l’embouchure de la trompette.<br />

Dans la cérémonie religieuse funèbre qui se fait autour de tombeau d’Eurydice, au premier acte<br />

d’Orfeo, Gluck adjoignit le cornetto aux trois trombones pour accompagner les quatre parties du<br />

choeur.”<br />

30 Kunitz, Posaune, p. 806. “die Posaunenstimmen ausdrücklich als Posaune I - IV bezeichnete.”<br />

31 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Messe in c (KV 427), ed. Monika Holl and Karl-Heinz Köhler, Neue<br />

Mozart Ausgabe I/1/1, vol. 5, (Kassel, Basel, etc. 1983), p. XVII. “Alle Bemerkungen zur Mitwirkung<br />

der Posaunen im Kyrie wurden von Mozart erst zu einem späteren Zeitpunkt in das Autograph

WEINER<br />

159<br />

nachgetragen, wie an mehreren Stellen durch die Plazierung der betreffenden Anmerkung oder durch<br />

das Darüberschreiben über bereits vorhandene Schriftzeichen zu erkennen ist. Es ist möglich, daß<br />

Mozart diesen Arbeitsgang mehr mechanisch ausführte und nicht so sehr darauf achtete, wie oft und<br />

in welchen Stimmen er Einträge anbrachte.”<br />

32 And Kunitz presumably would have resisted the temptation to designate his beloved soprano<br />

trombone as “<strong>Trombone</strong> nullo.”<br />

33 This instrument was recently purchased by the Trumpet Museum Schloss Kremsegg, Austria.<br />

See Lars Laubhold, “Sensation or Forgery? The 1677 Soprano <strong>Trombone</strong> of Christiann Kofahl,”<br />

Historic Brass Society Journal 12 (2000): 259-265. Anthony Baines (Brass Instruments: Their History<br />

and Development, [London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1976, 2/1978], p. 179), cites the soprano<br />

trombone made in 1733 by J.H. Eichentopf, Leipzig, as the oldest extant instrument of this type.<br />

This instrument, formerly in Breslau (Wroclaw), was apparently lost or destroyed during World War<br />

II, but is documented in the catalogue of the former Breslau collection (Schlesisches Museum für<br />

Kunstgewerbe und Altertümer, Führer und Katalog zur Sammlung alter Musikinstrumente, ed. Peter<br />

Epstein and Ernst Scheyer [Breslau: Verlag des Museums, 1932], p. 43). Sometimes falsely cited<br />

(based on the information in Lyndesay G. Langwill, An Index of Musical Wind Instrument Makers,<br />

[Edinburgh: Langwill, 5/1977], p. 93) as the oldest soprano trombone is an instrument from 1697<br />

by Johann Karl Kodisch, Nuremberg, now in Burgdorf Castle, Burgdorf, Switzerland; it is in fact<br />

a tenor trombone.<br />

34 Christoff Weigel, Abbildung der Gemein-Nützlichen Haupt-Stände (Regensburg 1698), p. 233.<br />

“Die Posaunen sind ebenfalls unterschiedlicher Gattung / als Discant- Alt- Tenor- Baß- und Quart-<br />

Posaunen.”<br />

35 Johann Samuel Halle, Werkstäte der heutigen Künste (Brandenburg and Leipzig 1764), p. 371.<br />

“Posaunen gibt es vier; Discant- Alt- Tenor und Quart- oder Quintposaune.”<br />

36 Johann Daniel Berlin, Musikaliske Elementer (Trondheim 1744). Cited in Petra Leonards, Edward<br />

H. Tarr, und Bjarne Volle, “Die Behandlung des Zinken in zwei norwegischen Quellen des 18. Jahrhunderts,”<br />

Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis, 5 (1981): 347-360, here 352.<br />

37 Cited in Arnold Schering, “Die alte Chorbibliothek der Thomasschule in Leipzig,” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft<br />

1 (1918/19): 275-288, here 280. “Die weil die <strong>Trombone</strong>n gute Kirchen Instrumente, die<br />

izo vorhanden aber ganz alt und zerbeugt sind, daher auch nicht wohl zum Gebrauch dienen, so wäre<br />

nöthig daß an deren Stadt andere neue, und zwar ein Paar Discant <strong>Trombone</strong>n angeschafft würden.”<br />

From references in the same document to “3 alte <strong>Trombone</strong>n, alß Alt, Tenor u. Baß <strong>Trombone</strong>,” and<br />

elsewhere in the same document to “3 alte <strong>Trombone</strong>n, nehmlich 2 Tenor und 1 Alt Trombon,” we<br />

can be reasonably certain that Kuhnau’s Discant <strong>Trombone</strong>n are instruments of soprano size.<br />

38 Ibid.<br />

39 Cited in Arnold Schering, “Die Leipziger Ratsmusik von 1650 bis 1775,” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft<br />

3 (1921): 17-53, here 45. “Der 1ste Kunstgeiger Pfaffe... 3) Den simplen Choral auf der<br />

Discant- Alt- Tenor- und Baß-Posaune, (welche letztere niemand unter seinen Collegen beßer als er<br />

und sein Bruder bläßt, und die eine gute Lunge erfordert), hat er gut geblasen.”<br />

40 According to Johann Adam Hiller (Wöchentliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend,<br />

Leipzig, 23 October 1769; rpt. Hildesheim and New York: Olms, 1970), “the chorale is sung<br />

in four parts by the choir to the ususal melody, and to support it the composer takes recourse to a<br />

choir of trombones.” (“Der Choral wird von dem Chore nach der gewöhnlichen Melodie vierstimmig<br />

gesungen, und zur Verstärkung desselben nimmt der Componist ein Chor Posaunen zu Hülfe.”)<br />

My efforts to obtain copies of works by Doles containing trombone parts have been unsuccessful;<br />

the holdings of the Thomasschule, including practically all of Doles’ autographs as well as his works<br />

with trombones, were presumably destroyed in December 1943 (personal communication from the

160<br />

HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL<br />

Bach-Archiv Leipzig, 15 November 2000). See also Helmut Banning, Johann Friedrich Doles, Leben<br />

und Werke (Diss. Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität Berlin, 1939), pp. 149 and 198-245.<br />

41 Both works are in the holdings of D-B: Johannes-Passion (Mus. ms. 21 705 — TVWV 5:46);<br />

Markus-Passion (Mus. ms. 21 707 — TVWV 5:52). See Georg Philipp Telemann: Autographe und<br />

Abschriften, ed. Joachim Jaenecke, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kultutbesitz, Kataloge der<br />

Musikabteilung I/7 (Munich: Henle 1993), pp. 140-143. I would like to thank Kantor Johannes<br />

Pausch, Hamburg, for calling my attention to the soprano trombone parts in these two works.<br />

42 See Klaus Winkler, “Die Anfänge der Bläsermusik bei der Herrnhuter Brüdergemeinde im 18.<br />

Jahrhundert,” Das Musikinstrument 43 (1994): 58-67.<br />

43 Rijksarchief Utrecht, Ms. Z 1157. This manuscript contains twenty-three numbered “sonatas,”<br />

six unnumbered pieces including God Save the King and Rule Brittania, as well as fragments of seven<br />

other pieces. A modern edition of the “sonatas” has been published as 23 Herrnhuter Sonaten, ed.<br />

Ben van den Bosch (Munich: Strube Verlag, 1988)<br />

44 6 Sonaten auf Posaunen die Cruse. Collections of the Moravian Music Foundation, Winston-Salem,<br />

NC, catalogue number SCM 261 (Salem Collegium Musicum collection). (Sonatas 4-6 are missing<br />

the soprano part.) See also Winkler, “Die Anfänge,” pp. 61 and 64. Modern edition of Sonata No.<br />

3, ed. Edward H. Tarr and Harry H. Hall (Cologne: Wolfgang G. Haas Verlag, 1997).<br />

45 Set of trombone partbooks, copied by Johann Friedrich Peter (1790s?). Collections of the Moravian<br />

Music Foundation, Winston-Salem, NC, catalogue number SB 14.<br />

46 Communication from Stewart Carter, 13 November 2000.