The New Bollywood: - silversalt pr

The New Bollywood: - silversalt pr

The New Bollywood: - silversalt pr

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 30<br />

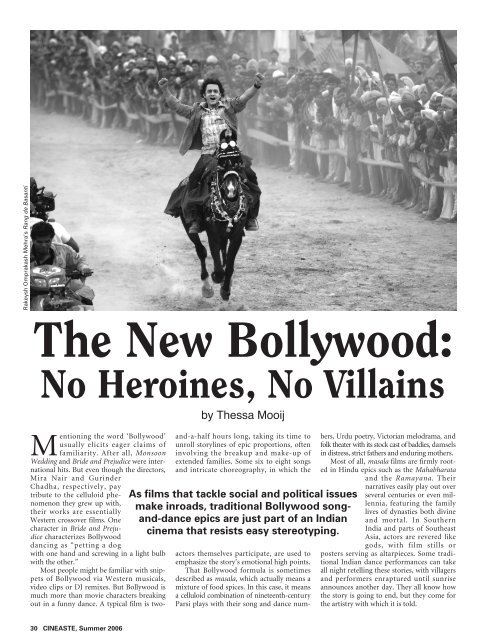

Rakeysh Om<strong>pr</strong>akash Mehra’s Rang de Basanti<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Bollywood</strong>:<br />

No Heroines, No Villains<br />

Mentioning the word ‘<strong>Bollywood</strong>’<br />

usually elicits eager claims of<br />

familiarity. After all, Monsoon<br />

Wedding and Bride and Prejudice were international<br />

hits. But even though the directors,<br />

Mira Nair and Gurinder<br />

Chadha, respectively, pay<br />

tribute to the celluloid phenomenon<br />

they grew up with,<br />

their works are essentially<br />

Western crossover films. One<br />

character in Bride and Prejudice<br />

characterizes <strong>Bollywood</strong><br />

dancing as “petting a dog<br />

with one hand and screwing in a light bulb<br />

with the other.”<br />

Most people might be familiar with snippets<br />

of <strong>Bollywood</strong> via Western musicals,<br />

video clips or DJ remixes. But <strong>Bollywood</strong> is<br />

much more than movie characters breaking<br />

out in a funny dance. A typical film is two-<br />

30 CINEASTE, Summer 2006<br />

by <strong>The</strong>ssa Mooij<br />

and-a-half hours long, taking its time to<br />

unroll storylines of epic <strong>pr</strong>oportions, often<br />

involving the breakup and make-up of<br />

extended families. Some six to eight songs<br />

and intricate choreography, in which the<br />

As films that tackle social and political issues<br />

make inroads, traditional <strong>Bollywood</strong> songand-dance<br />

epics are just part of an Indian<br />

cinema that resists easy stereotyping.<br />

actors themselves participate, are used to<br />

emphasize the story’s emotional high points.<br />

That <strong>Bollywood</strong> formula is sometimes<br />

described as masala, which actually means a<br />

mixture of food spices. In this case, it means<br />

a celluloid combination of nineteenth-century<br />

Parsi plays with their song and dance num-<br />

bers, Urdu poetry, Victorian melodrama, and<br />

folk theater with its stock cast of baddies, damsels<br />

in distress, strict fathers and enduring mothers.<br />

Most of all, masala films are firmly rooted<br />

in Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata<br />

and the Ramayana. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

narratives easily play out over<br />

several centuries or even millennia,<br />

featuring the family<br />

lives of dynasties both divine<br />

and mortal. In Southern<br />

India and parts of Southeast<br />

Asia, actors are revered like<br />

gods, with film stills or<br />

posters serving as altarpieces. Some traditional<br />

Indian dance performances can take<br />

all night retelling these stories, with villagers<br />

and performers enraptured until sunrise<br />

announces another day. <strong>The</strong>y all know how<br />

the story is going to end, but they come for<br />

the artistry with which it is told.

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 31<br />

This makes masala films an acquired<br />

taste for Westerners, who are used to seeing<br />

a ninety-minute feature about one <strong>pr</strong>otagonist<br />

chasing after his or her goal. Indian<br />

audiences would want to know what their<br />

parents are like, to whom they are married,<br />

and where their kids are. Seeing the <strong>pr</strong>otagonist<br />

deal with an overbearing bari ma<br />

(grandmother) or a corrupt cousin gives<br />

them crucial information about the <strong>pr</strong>otagonist’s<br />

morals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> film industry in Bombay is not fond<br />

of the moniker ‘<strong>Bollywood</strong>,’ even though<br />

they invented the word in the Eighties. In<br />

the nationalist Nineties it became a sign of<br />

weakness to suggest a connection with<br />

American blockbusters. Even the city itself<br />

was renamed Mumbai in a nationalist campaign,<br />

although many filmi people continue<br />

to call it by its old name. One politically correct<br />

alternative is ‘Indian cinema.’ That<br />

would leave no distinction between the<br />

musical blockbusters coming out of Bombay,<br />

films shot in any of India’s twenty-one<br />

languages such as Hindi, Bengali, Tamil or<br />

Telugu, and documentaries about social<br />

issues. <strong>The</strong> Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray,<br />

whose world film classics<br />

spawned what Indians call<br />

‘parallel’ (the equivalent of<br />

art-house) cinema, would<br />

fall in the same category as<br />

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s<br />

Hindi blockbuster Devdas.<br />

<strong>The</strong> other suggested<br />

moniker, ‘Hindi cinema,’ is<br />

also a bit of misnomer,<br />

since that would suggest,<br />

for instance, that Parineeta—a<br />

film made by a<br />

Bengali director and based<br />

on a Bengali novel, but<br />

financed out of Mumbai—<br />

is basically Hindi. And<br />

strictly speaking Mumbai<br />

culture is Marathi, not<br />

Hindi. Some Tamil films<br />

are based on the masala<br />

formula, but would that<br />

make them Hindi, too? To<br />

confuse things further,<br />

non-Hindi cities like Kolkata<br />

(the modern spelling<br />

of Calcutta) and Lahore in<br />

Pakistan have already been<br />

dubbed Kollywood and<br />

Lollywood respectively.<br />

Politically correct film people<br />

call it ‘Hindi cinema,’<br />

but the rest of the world<br />

calls it ‘<strong>Bollywood</strong>.’ <strong>The</strong><br />

film business is one of the<br />

country’s few industries<br />

where caste, religion or<br />

tribe truly does not matter,<br />

as long as you bring money<br />

or desired skills. In view of<br />

that mix, ‘masala film’ seems<br />

like a good com<strong>pr</strong>omise.<br />

Reflections from within the Industry<br />

Last June, the Mumbai industry descended<br />

upon the Dutch capital of Amsterdam.<br />

<strong>The</strong> International Indian Film Academy<br />

(IIFA) organizes its annual awards ceremonies<br />

abroad to <strong>pr</strong>omote Indian cinema<br />

on an international stage. Actors and<br />

actresses revered by billions in Asia, Africa,<br />

and Arab countries walked around amidst<br />

the clueless locals, chased only by their<br />

arduous Dutch fans of South Asian descent.<br />

One of <strong>Bollywood</strong>’s most <strong>pr</strong>ominent<br />

lyricists, Javed Akhtar, explained the difference<br />

between his films and those of the<br />

Dutch film <strong>pr</strong>ofessionals filling the room:<br />

“European films tend to deal with one emotion,<br />

or one <strong>pr</strong>oblem. You can see them as<br />

short stories; whereas, an Indian film is<br />

more like a novel. If you would make a film<br />

in India called It Happened One Night, people<br />

would feel cheated! <strong>The</strong>y want largerthan-life<br />

stories. Indian sagas have to have<br />

every emotion in the book. In our first talkie<br />

from 1933 there were fifty songs! <strong>The</strong>re was<br />

never any doubt that we wouldn’t use songs.<br />

As a lyricist, I write to an existing tune and I<br />

try to solve a narrative <strong>pr</strong>oblem in the con-<br />

Onir’s My Brother Nikhil is the first <strong>Bollywood</strong> film to deal with AIDS.<br />

tent of the lyrics. But I’m always dependent<br />

on whether a story is conducive to writing a<br />

song, whether it has certain sensibilities.”<br />

Perhaps even more so than other cinemas,<br />

masala films reflect changes in India’s<br />

society and politics. “You can analyze India<br />

from the films,” said Akhtar. “Art records<br />

hopes, fears, <strong>pr</strong>ide, and humiliation. Behind<br />

the glamor and the dances you can see our<br />

contemporary aspirations. In the Fifties,<br />

there was idealism and hope in politics and<br />

cinema. Prosperity seemed just around the<br />

corner, but since there was a socialist climate,<br />

rich people were the bad guys. In the Seventies<br />

there was a breakdown of our institutions,<br />

martial law, the rise of vigilantes and<br />

the angry young man. <strong>The</strong> Eighties saw a dip<br />

in politics, music, films, and art. <strong>The</strong> industrialization<br />

of the Seventies had led to the<br />

rise of a middle class that was different from<br />

the landed gentry. <strong>The</strong>y were the first generation<br />

to get educated on a massive scale.”<br />

During the rule of the Hindu BJP party<br />

from 1994 to 2004, masala films reached high<br />

levels of technical excellence, <strong>pr</strong>oviding picture-perfect<br />

visuals and soundtracks—but<br />

with storylines and attitudes reflecting the<br />

party’s conservative stance,<br />

emphasizing family values<br />

and religious patriotism.<br />

That decade <strong>pr</strong>oduced<br />

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge<br />

(1995), still shown in<br />

the Maratha Mandir <strong>The</strong>ater<br />

in Bombay, and recently<br />

<strong>pr</strong>onounced the<br />

longest running film in<br />

India. <strong>The</strong> film cemented<br />

the career of actor Shah<br />

Rukh Khan, now <strong>Bollywood</strong>’s<br />

most powerful player.<br />

He plays a London-based<br />

student who meets a fellow<br />

Indian Londoner on a train<br />

in Switzerland. After dropping<br />

his ladies’ man act,<br />

they must overcome her<br />

parents’ objections to the<br />

pairing. Only by returning<br />

to her native Punjab with<br />

its yellow mustard fields,<br />

and embracing the ways of<br />

the old country, are they<br />

fully accepted.<br />

<strong>The</strong> film was an instant<br />

hit because of its portrayal<br />

of hip young NRI’s (nonresident<br />

Indians), who also<br />

flocked to see the film all<br />

over the world. For the first<br />

time, British and American<br />

audiences of Indian descent<br />

who saw their lifestyles<br />

partly reflected in the<br />

film, turned out to be a<br />

force to be reckoned with.<br />

Actor Shah Rukh Khan,<br />

who <strong>pr</strong>eviously played psychotic<br />

bad guys, broke<br />

CINEASTE, Summer 2006 31

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 32<br />

Devdas<br />

through with his first role as a romantic hero<br />

with a naughty college-boy persona. <strong>The</strong><br />

packaging was slick, the <strong>pr</strong>oduction values<br />

high, but the message was retrogressive:<br />

return to the motherland and its family values.<br />

“Here’s what turns my stomach,” writes<br />

Indian journalist Jerry Pinto in Outlook India, a<br />

current-affairs weekly. “In all mainstream<br />

cinema…the hero must stand for us, so that<br />

we can vicariously live out our fantasies,<br />

winning the <strong>pr</strong>etty lady, beating up the<br />

goons, s<strong>pr</strong>itzing politicians with a machinegun.<br />

Now what fantasy is it where the hero<br />

says he won’t whisk off his heroine and marry<br />

her without his father-in-law’s permission?<br />

Where is the anarchic potential of love that<br />

was always celebrated in Hindi films?”<br />

<strong>The</strong> films Pinto refers to (Sujata, Bandhini,<br />

Pakeezah) were made in the Sixties, when<br />

violence started flaring up, and the early<br />

Seventies, when that violence led to martial<br />

law, and with it a subsequent loss of faith in<br />

institutions. Anarchy is a luxury few people<br />

can afford in real life. It is an ingredient of<br />

the dream factory. Viewers can revel in their<br />

heroes’ rejection of rejection.<br />

Indian Cinema Today<br />

Today’s India is experiencing a significant<br />

growth in the computer and services<br />

industries. With increasing numbers of city<br />

dwellers aspiring and reaching middle-class<br />

security, they are less interested in anarchy<br />

and more in stability. Women are joining<br />

the work force in ever-greater numbers.<br />

Thanks to cable TV and a newfound <strong>pr</strong>osperity,<br />

Indian tastes are changing. <strong>The</strong> classic<br />

masala flick tried to cater to an all-Indian<br />

audience. By casting a broad narrative net of<br />

32 CINEASTE, Summer 2006<br />

humor, melodrama, tears, and laughter—all<br />

s<strong>pr</strong>inkled with multicolored confetti—<strong>pr</strong>oducers<br />

wanted to catch both the older farmhand<br />

who saves up all week for a movie ticket<br />

and the young, wealthy urbanite.<br />

Multiplexes charging high ticket <strong>pr</strong>ices<br />

have s<strong>pr</strong>ung up in cities and towns, accessible<br />

only to the upper-middle classes. Less well-off<br />

viewers make do with soap operas that are<br />

challenging taboos even more than feature films<br />

are. In response to the changing sensibilities<br />

of urban, middle-class audiences, the more<br />

adventurous <strong>pr</strong>oducers are searching for<br />

something different. More film-school<br />

graduates are getting their first break in an<br />

industry where the big stars have typically<br />

passed on the baton to their children,<br />

regardless of their talent. <strong>The</strong>se educated<br />

first-time directors are bringing new stories<br />

to Bombay, or new ways of telling old stories.<br />

Some <strong>pr</strong>oducers are placing their bets on<br />

new talent outside the usual recruiting pool<br />

of acting dynasties such as the Bachchans<br />

and Kapoors. As a result, there have been a few<br />

films that seem to be breaking away from<br />

the formula, whether it’s in style, content, or<br />

<strong>pr</strong>oduction methods. Most of them—Black, My<br />

Brother Nikhil, Rang de Basanti, and Being<br />

Cyrus—have been shown in the U.S. through<br />

NRI-targeted distributors or art-house theaters<br />

like the ImaginAsian in <strong>New</strong> York.<br />

“A lot of the young generation directors<br />

are students from film schools,” explains<br />

Onir, director of My Brother Nikhil, who<br />

<strong>pr</strong>esented his film at the Asia Society in <strong>New</strong><br />

York last June. Born in Nepal, he is a graduate<br />

of comparative literature at Kolkata<br />

Jadavpur University and trained as a filmmaker<br />

in Berlin. After the <strong>New</strong> York screen-<br />

ing, he took his film to Germany, where he<br />

showed it at the annual ‘<strong>Bollywood</strong> &<br />

Beyond’ festival in Stuttgart. “<strong>The</strong>y do not<br />

belong to the ‘<strong>Bollywood</strong> dynasty,’” and<br />

hence the films are much more experimental.<br />

Since audiences are rejecting ninety percent<br />

of formula <strong>Bollywood</strong> films, filmmakers<br />

are looking at how to get audiences into<br />

the theaters with new ideas and treatments.<br />

British filmmaker and writer Nasreen<br />

Munni Kabir has played a major role in<br />

popularizing the genre through U.K.’s<br />

Channel Four documentaries and through<br />

several books. She has just completed two<br />

documentaries about the actor Shah Rukh<br />

Khan, <strong>The</strong> Inner/Outer World of Shah Rukh<br />

Khan, released on DVD by Eros Entertainment<br />

last September. According to Kabir,<br />

audiences in India are ready for a change. It<br />

seems that the days of anarchic love are<br />

numbered. “<strong>The</strong> characters are allowed to<br />

be more human today in films,” she says.<br />

“In the Fifties, which to me was <strong>Bollywood</strong>’s<br />

best period, they were more human too, but<br />

they had a different kind of morality. Now<br />

they have to do with the complexities of living in<br />

a modern India. Audiences are less bound to<br />

social rules. <strong>The</strong>y understand through their<br />

own living that life is a struggle. <strong>The</strong>re is scope for<br />

more complexity. I think that comes from<br />

watching Indian TV soaps; some of them<br />

talk about the difficulties of living with a<br />

mother-in-law, and so on. All these taboo<br />

areas of family relations are now examined.”<br />

In 1996, Canadian director Deepa<br />

Mehta’s Fire sparked riots in India because<br />

of the taboo subject matter of her film: the<br />

love between two women. <strong>The</strong>aters were<br />

stormed in <strong>pr</strong>otest against the film’s portrait<br />

of two lonely women finding solace in each<br />

other’s arms. <strong>The</strong> <strong>pr</strong>oducers of My Brother<br />

Nikhil, director Onir and main actor Sanjay<br />

Suri, weren’t going to take the same risk.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir film deals with the reaction of a young<br />

man’s family when they find out he has been<br />

infected with HIV.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir main concern was not to focus on<br />

Nikhil’s sexuality or even how he contracted<br />

the virus in the first place. Instead they<br />

focused on Nikhil’s environment—his partner,<br />

family, friends, colleagues, and authorities.<br />

<strong>The</strong> subject matter might suggest arthouse<br />

drama, but My Brother Nikhil aims at<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> audiences, with a mainstream<br />

cast (top actress Juhi Chawla and veteran<br />

Victor Bannerjee), a successful soundtrack,<br />

and an innovative marketing campaign by<br />

major distributor Yash Raj Films, in which<br />

young <strong>Bollywood</strong> stars ask the public: “I<br />

care for Nikhil—do you?” <strong>The</strong> film is one of<br />

the few commercial <strong>pr</strong>oductions to be<br />

financed independently.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> film starts with a message saying it’s<br />

not based on a true story,” explains Suri.<br />

“We had to put it there to pass the censor;<br />

they wanted us to avoid any kind of controversy<br />

coming from anywhere. <strong>The</strong> law we<br />

mention in the film [isolating HIV positive<br />

citizens] is really true, and the story did hap-

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 33<br />

pen. We put all our money in this—friends’<br />

money, insurance money, and savings. We<br />

could not afford any kind of controversy.<br />

We wanted the film to be released. We could<br />

have argued with the censor, but we<br />

couldn’t afford any kind of delay.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> film is a modest success in India—<br />

having been received positively by the mainstream<br />

media. It continues to be screened,<br />

and is also shown at AIDS awareness events<br />

in smaller towns or remote regions. Director<br />

Onir says some people bring their families<br />

to see the film in order to out themselves.<br />

But so far, the film has not been picked<br />

up by any of the <strong>Bollywood</strong> distributors in<br />

either the U.S. or the U.K., as NRI audiences<br />

are thought to be interested in nostalgic<br />

romances that reinforce their idea of the<br />

motherland they left behind—rather than in<br />

bold new <strong>pr</strong>oductions that highlight changes<br />

in that same motherland. “It’s a big <strong>pr</strong>oblem<br />

for us,” says Onir. “Mainstream <strong>Bollywood</strong><br />

distributors in the U.S. or U.K. are not willing<br />

to take risks and invest in advertising<br />

and <strong>pr</strong>omoting this kind of film. Because<br />

overseas audiences supposedly don’t want to<br />

see films like My Brother Nikhil, they don’t<br />

want to fund them. I think the second-generation<br />

NRI audiences would be interested<br />

in seeing a film like ours, but they don’t get<br />

an opportunity to do so. We need a little bit<br />

more support for changing India and changing<br />

Indian cinema from the usual singing<br />

and dancing around trees.”<br />

Some literary adaptations highlight the<br />

differences between classic <strong>Bollywood</strong> and<br />

filmmakers who are pushing against the<br />

boundaries. <strong>The</strong> blockbuster Devdas (2002)<br />

is based on a novel by the Calcutta author<br />

Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, whose literary<br />

classics from the early twentieth century<br />

inspired no less than forty screen adaptations.<br />

Devdas and his other works deal with<br />

weak Brahmin men whose upper caste<br />

stands in the way of happy marriages with<br />

their lower-caste childhood sweethearts.<br />

With a budget of $10 million, Devdas is the<br />

most expensive film ever made in India. A<br />

baroque fable with a distinctly unhappy<br />

ending, it features the world’s best-known<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> actors, Shah Rukh Khan and<br />

Aishwarya Ray (Bride and Prejudice).<br />

Devdas is masala at its most glorious. It<br />

takes visual vibrancy and sweeping emotions<br />

to the max, not an easy accomplishment in a<br />

genre that is already ruled by the motto<br />

‘more is more.’ <strong>The</strong> film has a highly polished<br />

look with sensually saturated colors,<br />

spellbinding choreography, and a memorable<br />

soundtrack. Partly cofinanced by French<br />

<strong>pr</strong>oducers, it <strong>pr</strong>emiered at Cannes and made<br />

$5 million in North America alone.<br />

Parineeta is another screen adaptation<br />

from a Chattopadhyay novel, but it is almost<br />

the polar opposite of Devdas. Its world <strong>pr</strong>emière<br />

took place in Amsterdam during the<br />

2005 IIFA Awards. Compared to Devdas,<br />

Parineeta is a study in restraint, apart from a<br />

hammed-up finale that feels tacked on.<br />

Overall, Parineeta is a refined piece of work<br />

by <strong>pr</strong>oducer Vidhu Vinodh Cho<strong>pr</strong>a, who<br />

has built his career making high quality features<br />

(Mission Kashmir, Munnabhai MBBS).<br />

Parineeta went on to screen in the highly<br />

selective Forum section of the International<br />

Berlin Film Festival. First-time feature director<br />

Pradeep Sarkar, a Kolkata native who<br />

has worked in advertising, shifted the story<br />

to 1962, a time of social unrest. Sarkar focuses on<br />

the family’s faded Bengali gentility, giving<br />

the women a mid-Sixties glamor similar to<br />

Wong Kar-wai’s vamps from In the Mood for<br />

Love and 2046—reminders that during that<br />

decade, Asia embraced pop culture, just like<br />

the rest of the world.<br />

After the <strong>pr</strong>emiere, Parineeta’s main<br />

actor Saif Ali Khan spoke about making the<br />

film: “My mother [actress Sharmila Tagore<br />

and great-granddaughter of Nobel-winning<br />

poet Rabindranath Tagore] sent me a text<br />

message to say she is really <strong>pr</strong>oud of this<br />

film. She’s never done that before. She’s<br />

Bengali and they’re quite touchy about their<br />

art. It’s the first time I’ve worked with a<br />

lighting person who created so many shadows,<br />

as opposed to light.”<br />

Comedy actor Khan was an unusual casting<br />

choice for the tortured soul of Shekhar,<br />

who gets stuck running the family business<br />

instead of following his heart. He yearns for<br />

a music career and the orphan girl he grew<br />

up with, but social mores stand in his way.<br />

Although mainly a love story, the film shows<br />

a family holding on to better days while<br />

Kolkata is burning. <strong>The</strong> film’s restraint<br />

makes it stand out from the usual masala<br />

fare. Producer Cho<strong>pr</strong>a’s risk in casting Khan<br />

has paid off. “In Hindi cinema we are very<br />

melodramatic. It’s all over the top. It’s very<br />

A scene from Homi Adajania’s black comedy, Being Cyrus.<br />

rare to see an actor who holds his own in a<br />

classic story. In the climactic moment he<br />

looks at his father and just walks away; I<br />

really don’t recall a Hindi actor who underplayed<br />

a role like that.”<br />

Underplaying has paid off for Saif Ali<br />

Khan, who is playing the role of Iago in an<br />

upcoming Indian screen version of Othello.<br />

In the past year, Khan has emerged as an<br />

actor of substance. After portraying yet<br />

another breezy playboy in Salaam Namaste<br />

(2005), he is surpassing his Parineeta performance<br />

in this year’s sur<strong>pr</strong>ise hit, Being<br />

Cyrus. Made by first-time director Homi<br />

Adajania and a handful of first-time <strong>pr</strong>oducers,<br />

this drama, drenched in black humor,<br />

was first screened in the U.S. to a sold-out<br />

crowd at <strong>New</strong> York’s South Asian Film Festival<br />

in December 2005. Three months later,<br />

the film was released worldwide by Eros<br />

International, a mainstream <strong>Bollywood</strong> distributor<br />

with an office in <strong>New</strong> Jersey. This is<br />

also India’s first ever English-language film.<br />

Having middle-class Bombay characters<br />

speak English doesn’t require a great stretch<br />

of the imagination. At the Parineeta <strong>pr</strong>ess<br />

conference, Saif Ali Khan, who was educated<br />

in England, became slightly uncomfortable<br />

when Dutch journalists of Indian descent<br />

started firing questions in Hindi at him.<br />

Khan plays Cyrus, a rootless drifter who<br />

ends up in a curious ménage à trois with a<br />

sculptor, who has exchanged pottery for<br />

industrial-strength pot, and his gaudy wife,<br />

whose libido goes into overdrive the minute she<br />

sees Cyrus standing on their doorstep. Cyrus<br />

manages to survive the disastrous dynamics<br />

in this particular household, but when he<br />

travels to Bombay to deal with the rest of the<br />

sculptor’s family, the plot takes a dark turn.<br />

CINEASTE, Summer 2006 33

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 34<br />

Diya Mirza (with umbrella) and Saif Ali Khan (with racing glasses)<br />

star in Pradeep Sarkar’s remake of Parineeta (A Married Woman).<br />

<strong>The</strong> sculptor’s older brother is abusing<br />

their ancient father, hoping to speed up the<br />

old man’s demise so he can inherit his Bombay<br />

building. Cyrus takes pity on the man<br />

and tries to help him, but ultimately, he<br />

pursues a plot of his own. Having grown up<br />

in foster homes and still bearing the visible<br />

scars of that experience, Cyrus’s demons<br />

come to chase him in this Bombay episode.<br />

Director Adajania clearly enjoys visualizing<br />

those demons in the form of flashbacks,<br />

using sound effects and bold stylistic choices<br />

that are unusual for <strong>Bollywood</strong>.<br />

Comic relief is <strong>pr</strong>ovided by veteran actor<br />

Boman Irani, a friend of the filmmaker’s<br />

father and undoubtedly one of the forces<br />

that gave the young director his first chance.<br />

His pomposity as the greedy older brother<br />

comes with a great deal of cursing in Parsi<br />

slang, which sent the audience in <strong>New</strong><br />

York’s ImaginAsian <strong>The</strong>ater howling with<br />

laughter. Since the film is not subtitled,<br />

non-Hindi speakers can only guess at the<br />

colorful content of Irani’s curses.<br />

By Western standards, this is a particularly<br />

well-made indie drama. By Bombay standards,<br />

however, it’s a watershed moment. India has<br />

<strong>pr</strong>oduced its fair share of world-class art-house<br />

cinema, but this film is special because it has<br />

been made in the <strong>Bollywood</strong> environment with<br />

big commercial stars, and it has been marketed<br />

through regular <strong>Bollywood</strong> channels. With a<br />

running time of ninety minutes, the film has no<br />

dance numbers or any other musical interludes,<br />

and the emotions are toned down, apart from<br />

the apparently hilarious Boman Irani. “If the<br />

film had been released five years ago, I would<br />

have said there’s no market for it in India,”<br />

said trade journalist Komal Nahta on the BBC<br />

radio show Film Café. “It’s not the usual<br />

Hindi film. But now there are a growing number<br />

of people who like to see such films, which is why<br />

the film had a reasonable start in Bombay.”<br />

34 CINEASTE, Summer 2006<br />

Like Hollywood, <strong>Bollywood</strong> is fond of<br />

hijacking material from successful films<br />

from all over the world, whether Hollywood,<br />

<strong>New</strong> York or Hong Kong. In Black<br />

(2005) director Sanjay Leela Bhansali magnified<br />

the painful suffering that was already<br />

<strong>pr</strong>esent in his <strong>pr</strong>evious blockbuster Devdas.<br />

Black is a songless, danceless film that is<br />

based on the play Aatam Vinjhe Paankh,<br />

which was inspired by William Gibson’s<br />

play about Helen Keller, <strong>The</strong> Miracle Worker.<br />

One of Bhansali’s <strong>pr</strong>evious films,<br />

Khamoshi, had dealt with the same <strong>pr</strong>oblems<br />

of deaf-mute people with no system to make<br />

sense of the world around them. Sadly,<br />

Khamoshi flopped as it may have been ahead<br />

of its time in 1996.<br />

<strong>New</strong> York’s ImaginAsian <strong>The</strong>ater <strong>pr</strong>esents<br />

U.S. <strong>pr</strong>emieres of many <strong>Bollywood</strong> films.<br />

In the last two years, revered veteran<br />

actor Amitabh Bachchan has reinvented<br />

himself from the angry young man to a<br />

patriarch with Hindu family values. In Black<br />

he plays against type as the drunk, washedup<br />

teacher. He tries to bring light to the<br />

deaf-blind-mute Michelle, who is a scared,<br />

violent girl, lashing out at everything she<br />

doesn’t know or understand. Actress Rani<br />

Mukherjee, who like many Indian actresses<br />

is often limited to playing the role of a girlfriend<br />

or wife, does an excellent job in portraying<br />

Michelle’s fear of the world around<br />

her. With her teacher’s help, Michelle ends<br />

up graduating from university and starts a<br />

clinic of her own.<br />

Like Devdas, the set designs are larger<br />

than life—a theatrically empty mansion,<br />

long shadows and dark-blue hues. Filled<br />

with Christian imagery, the film’s look is<br />

reminiscent of John Woo’s Hong Kong<br />

films, Bullet in the Head (1990) and Hardboiled<br />

(1992), in which Woo punctuates<br />

gory violence with moodily lit churches and<br />

white doves. Bhansali successfully externalizes<br />

Michelle’s panic, which she conquers,<br />

only to end up caring for her Alzheimer’safflicted<br />

teacher. Director Bhansali has taken<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong>’s <strong>pr</strong>eference for hautes émotions,<br />

but has swung the pendulum in the direction<br />

of despair, away from the usual ecstatic<br />

happiness displayed in typical masala films.<br />

His portrayal of Michelle’s panic is not<br />

merely psychological, the way it would be<br />

portrayed in Western realism, but is utterly<br />

cinematic—conveyed through set design,<br />

costumes and lighting. <strong>The</strong> film was more<br />

successful overseas than in India. Despite<br />

rave reviews and numerous awards, some<br />

rural audiences may have resisted this<br />

departure from the <strong>Bollywood</strong> dream factory.<br />

But Hollywood is paying attention.<br />

Bhansali is the first Indian director to have<br />

signed a <strong>pr</strong>oduction deal with a Hollywood<br />

studio, Sony Pictures Entertainment, to<br />

make a film in his own country and on his<br />

own terms. His Saawariya is not meant to be<br />

a potential crossover hit, but a full-blown<br />

Hindi <strong>pr</strong>oduction.<br />

As Bhansali’s work suggests, on a creative<br />

front, things are definitely changing on and<br />

off the soundstages of major studios. With<br />

the social democratic Congress Party having<br />

taken over the reign from the conservative<br />

BJP party, staunchly patriotic and conservative<br />

themes may be a thing of the past. All of<br />

the aforementioned films are cowritten by<br />

their directors and/or <strong>pr</strong>oducers respectively,<br />

so there seems to be room for directors’<br />

developing their own voice. It may be too<br />

early, however, to call it a <strong>New</strong> Wave, and<br />

historically, there have always been innovative<br />

directors within the industry.<br />

“It’s new and it’s not new,” says Nasreen<br />

Munni Kabir from her London office.<br />

“Black and Parineeta are remakes. <strong>The</strong>re is a<br />

tendency to look back. But younger filmmakers<br />

are looking for different subjects and<br />

their treatment of them is new. <strong>The</strong>y’re

30/Bolly<strong>The</strong>ssa 5/6/06 7:56 PM Page 35<br />

moving away from stereotypes,<br />

which is the most unusual thing.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no villain, or a heroine; the<br />

characterizations are changing.<br />

Every generation has to find its<br />

own language, and there’s a very<br />

healthy atmosphere. I expect a lot<br />

of movement in <strong>Bollywood</strong>. Every<br />

new film is redefining the genre.<br />

For me, the most interesting of<br />

recent films is Munnabhai because<br />

it continues the tradition of the<br />

working-class hero. His encounters<br />

with the middle classes are very<br />

funny.” <strong>The</strong> films Kabir cites are<br />

shorter (around two hours), contain<br />

less song and dance (although<br />

music remains a crucial component),<br />

and tap into the rich veins of<br />

psychological drama or social<br />

themes—sometimes subtly and sometimes<br />

not—than is usual for <strong>Bollywood</strong> <strong>pr</strong>oductions.<br />

Typically, length and form have <strong>pr</strong>evented<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> from making a big splash in<br />

the West, as other Asian genres have done.<br />

And, while <strong>Bollywood</strong> will never become<br />

‘parallel’ cinema—whose main auteurs<br />

Satyajit Ray, Mani Kaul, and Buddhadev<br />

Dasgupta are already revered in the West by<br />

festival <strong>pr</strong>ogrammers, critics, and scholars<br />

alike—the question remains as to whether it<br />

can open the door for new young filmmakers<br />

and help them find new audiences, both<br />

in India and abroad.<br />

This would be possible only if the industry—<strong>pr</strong>oduction,<br />

marketing, and distribution—is<br />

able to see the potential. “Producers<br />

need to find the guts to fund films that are<br />

not ‘<strong>pr</strong>ojects,’ a term used in <strong>Bollywood</strong> to<br />

refer to mainstream films with big casts<br />

composed of mainstream actors,” comments<br />

Onir from Germany, where he is <strong>pr</strong>esenting<br />

My Brother Nikhil in the country’s<br />

‘Beyond <strong>Bollywood</strong>’ festival in Stuttgart. “It<br />

has to come from a creative need to risk and<br />

invest in something new.”<br />

Gabriele Ammerman is a free-lance TV<br />

<strong>pr</strong>oducer from Germany who traveled to<br />

Amsterdam for the IIFA awards, hoping to<br />

make some <strong>Bollywood</strong> connections. After<br />

two major German channels, ARTE and<br />

RTL2, started showing <strong>Bollywood</strong> films last<br />

year, she has seen a surging interest in the<br />

genre, particularly among Germany’s Turkish<br />

population and German teenagers who<br />

consider <strong>Bollywood</strong> hip, thanks to the emergence<br />

of bhangra music and <strong>Bollywood</strong> club<br />

themes. Other Germans seem to ap<strong>pr</strong>eciate<br />

the dream world no longer offered by Hollywood<br />

or the European cinema.<br />

“Films like Veer-Zaara or Main Hoon Na<br />

may have a modern message thrown in, like<br />

a little feminism or the hope for peace<br />

between India and Pakistan, but still the<br />

masala recipe is the same as it was ten or<br />

twenty years ago,” Ammerman points out.<br />

“Black and Parineeta show how <strong>Bollywood</strong><br />

filmmakers are experimenting with different<br />

stories, settings and style. Right now they are<br />

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black, whose <strong>pr</strong>otagonist is blind,<br />

is an offbeat <strong>Bollywood</strong> film that has neither songs nor dance.<br />

not what <strong>Bollywood</strong> is known for here.<br />

Thanks to RTL2, Bhansali is by far the most<br />

popular <strong>Bollywood</strong> star in Germany. <strong>The</strong><br />

‘hardcore’ <strong>Bollywood</strong> lovers might be disappointed<br />

by a different kind of Hindi films;<br />

whereas, other people won’t watch the films<br />

if they think they’ll be seeing the usual <strong>Bollywood</strong><br />

flick with just too much schmaltz<br />

for their taste.”<br />

A few adventurous <strong>pr</strong>oducers and filmmakers<br />

seem to be breathing new life into<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> by making their own voices<br />

heard rather than sticking to the rules. But<br />

for real change to take effect, the industry<br />

needs to support them in terms of distribution,<br />

marketing, and exhibition. Making<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> a success in the West would<br />

require the London and <strong>New</strong> York-based<br />

Indian distributors to market to non-NRIs.<br />

“Unless international distributors pick up<br />

films for a wider audience, it will always<br />

remain for Indian audiences only,” says<br />

Kabir. “I went to see Stephen Chow’s Kung<br />

Fu Hustle, which is distributed by Columbia<br />

Tri-Star, and I can see why. It’s brilliantly<br />

made, very entertaining, and you don’t need<br />

to know the whole of Cantonese culture to<br />

follow the narrative. Indian films are definitely<br />

more complex in that way.”<br />

Gabriele Ammerman thinks classic <strong>Bollywood</strong><br />

stands a better chance in Germany<br />

than the newer, more adventurous films.<br />

“To get a wider German audience, the films<br />

would need to get some PR first, then a good<br />

translation or a dubbing. All this will cost<br />

money, and I can’t see anyone risking 200,000<br />

Euros to <strong>pr</strong>omote an unusual Hindi film here,<br />

without any guarantee of getting the money<br />

back. Only if the Indian film <strong>pr</strong>oducers invest in<br />

marketing and media relations, will their<br />

films have a chance on the Western market.”<br />

Lagaan <strong>pr</strong>oved that Western audiences<br />

were ready for a dose of Indian history,<br />

dance numbers and even an hour-long<br />

cricket match. Producer/actor Aamir Khan<br />

has recently followed this up with two other<br />

historically inspired roles as a rebel against<br />

British rule. He played a mutineer in last<br />

year’s <strong>The</strong> Rising, which collapsed under the<br />

weight of its historic <strong>pr</strong>etensions, leaving lit-<br />

tle room for character development<br />

and emotional plausibility.<br />

He played a similar role in this<br />

year’s highly successful Rang de<br />

Basanti, which shows that an audience<br />

exists for edgy drama with a<br />

political message. Khan plays an<br />

über-slacker and the ringleader of a<br />

group of fun-loving students who<br />

<strong>pr</strong>efer motor bikes and techno<br />

raves to attending classes. When a<br />

young British filmmaker wants<br />

them to play some of India’s first<br />

freedom fighters in her no-budget<br />

indie film, they slowly conquer<br />

their socio-political apathy. A personal<br />

tragedy fans the flames of<br />

their burgeoning indignation, and<br />

they take matters in their own<br />

hands. As this film and the Nineties<br />

hit DDLJ attests, young people in India and<br />

abroad wish to recognize themselves on<br />

screen, in films that take their lifestyle and<br />

concerns seriously.<br />

Although it has a few highly infectious<br />

and celebratory dance numbers, Rang de<br />

Basanti is not about extended families and<br />

big weddings. <strong>The</strong> marketing of this film has<br />

revolved around blogs and message boards,<br />

where star Aamir Khan chatted with fans,<br />

while the traditional media had to sit back<br />

and wait their turn for an interview slot.<br />

Some eager film pundits have already <strong>pr</strong>oclaimed<br />

Rang de Basanti ‘the Black of 2006,’<br />

but this was before Being Cyrus came out.<br />

“Rang de Basanti broke our attendance<br />

records,” says ImaginAsian theater <strong>pr</strong>ogrammer<br />

Dylan Marchetti. “We sold 4000<br />

tickets in three weeks and after a couple of<br />

screenings, there must have been some<br />

word-of-mouth buzz, because we started to<br />

see an increase in non-Indian visitors. It<br />

crossed over because it had an original story,<br />

not copied from Hollywood, plus a great<br />

soundtrack and a good cast.”<br />

It’s true that Rang de Basanti is closer to<br />

<strong>Bollywood</strong> with its emotional overdrive and<br />

colorful dance scenes. But any film about<br />

social issues had better pay extra attention to<br />

the emotional arc of its characters, and<br />

Being Cyrus with its dysfunctional individuals<br />

does a better job of keeping its viewers<br />

engaged, both emotionally and visually.<br />

India is a young country and is still<br />

defining itself. Should it give in to the lure of<br />

growing consumerism and other Western<br />

aspirations? Should it hold on to its homegrown<br />

values? But how to do that without<br />

regressing into conservative sloganeering?<br />

<strong>The</strong> Hindu conservatives may have retreated<br />

temporarily, but <strong>pr</strong>ide in the country’s independence<br />

is never far away.<br />

Perhaps it’s better not to look for this year’s<br />

Black, but to keep looking for the new talents<br />

who are slowly fighting their way through<br />

the <strong>Bollywood</strong> machine to get their vision<br />

on the big screen. After all, their films reflect<br />

a country that is expected to play a big role<br />

on the world stage of the new century. ■<br />

CINEASTE, Summer 2006 35