(DRAFT FOR REVIEW) - Global Forest Watch Canada

(DRAFT FOR REVIEW) - Global Forest Watch Canada

(DRAFT FOR REVIEW) - Global Forest Watch Canada

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

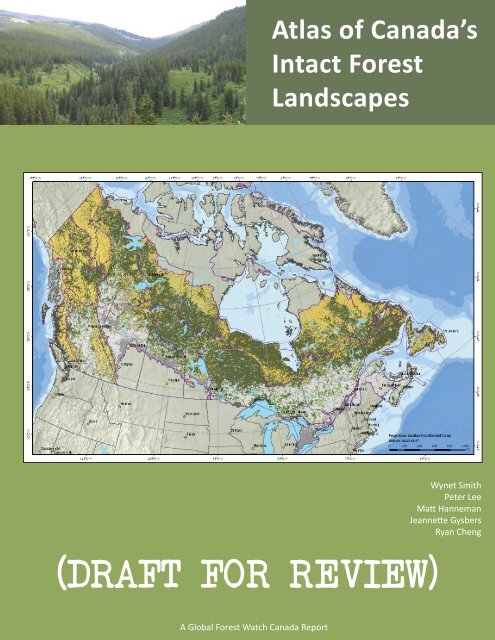

A <strong>Global</strong> A <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong> Report<br />

Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

Intact <strong>Forest</strong><br />

Landscapes<br />

(<strong>DRAFT</strong> <strong>FOR</strong> <strong>REVIEW</strong>)<br />

Wynet Smith<br />

Peter Lee<br />

Matt Hanneman<br />

Jeannette Gysbers<br />

Ryan Cheng

Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes<br />

By:<br />

Wynet Smith<br />

Peter Lee<br />

Matthew Hanneman<br />

Jeannette Gysbers<br />

Ryan Cheng<br />

Edmonton, Alberta, <strong>Canada</strong><br />

ISBN: ___<br />

©<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>, 2009<br />

Cover Design: Matt Hanneman, Peter Lee, Jeannette Gysbers<br />

Report Design and Layout: Jeannette Gysbers<br />

Map Design and Layout: Matt Hanneman<br />

Photos: All photos by <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>, unless otherwise noted<br />

Citation: Smith W, Lee PG, Hanneman M, Gysbers JD, Cheng R. 2009. Atlas of<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes. Edmonton, Alberta: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong><br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. 88 pp.

Dragonfly on maple leaves, Killarney Provincial Park, ON (06/2005)<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s forests are, for the most part, publicly owned.<br />

Canadians want to know about the state of the country’s<br />

forests. The Canadian Council of <strong>Forest</strong> Ministers<br />

recently reported that “Canadians are demanding more<br />

information, more options, more involvement in decision<br />

making, and more equitable sharing of benefits,” and that<br />

“policy makers, decision makers, and the public need tools<br />

to define and measure progress toward sustainable forest<br />

management.” The public expects open and transparent<br />

decision-making with respect to forest resources as well<br />

as an ability to participate in decisions being made about<br />

resource use. The demands for more information on<br />

forests in <strong>Canada</strong> indicate the general recognition of a<br />

growing need for a broad range of data on forests to<br />

improve forest policy and decision-making.<br />

Sustainable forest management, a policy priority of<br />

Canadian governments and the forest industry, is<br />

information-intensive and requires a broad range of<br />

timely, up-to-date information for landscape planning and<br />

management and for better monitoring, reporting, and<br />

verification. Sustainable forest management requires data<br />

Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong>. 00 . The state of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests<br />

00 – 00 : <strong>Forest</strong> industry competitiveness. Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong>,<br />

Canadian <strong>Forest</strong> Service, Ottawa. 79 pp.<br />

Canadian Council of <strong>Forest</strong> Ministers (CCFM). 00 . Criteria and<br />

indicators of sustainable forest management in <strong>Canada</strong>: national status<br />

00 . Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong>, Canadian <strong>Forest</strong> Service, Ottawa.<br />

Wang S. 00 . Managing <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests under a new social contract.<br />

The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : 8 – 90.<br />

World Commission on <strong>Forest</strong>s and Sustainable Development. 9.<br />

Our forests, our future. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.<br />

0 pp.<br />

Siry JP, Cubbage FW, Ahmed MR. 00 . Sustainable forest management:<br />

global trends and opportunities. <strong>Forest</strong> Policy and Economics<br />

7: – .<br />

Hickey GM, Innes JL, Kozak RA, Bull GQ, Vertinsky I. 00 .<br />

Monitoring and information reporting for sustainable forest management:<br />

an inter-jurisdictional comparison of soft law standards. <strong>Forest</strong><br />

Policy and Economics 9: 97– .<br />

Preface<br />

that extend beyond the scope of traditional government<br />

forestry departments and across the boundaries of<br />

provincial and territorial jurisdictions. An expanded<br />

information base requires a stakeholder approach and<br />

institutional reforms to facilitate partnerships7 and genuine<br />

collaboration8 amongst a range of actors, including<br />

9 0<br />

industry, government and researchers.<br />

Unfortunately, <strong>Canada</strong>’s ability to meet concerns and<br />

respond to commitments has often been hampered by<br />

outdated forest inventories and information systems.<br />

Dr. Richard R. Schneider pointed out in his 00 book on<br />

Alberta’s forests, Alternative Futures: Alberta’s Boreal <strong>Forest</strong>s<br />

at the Crossroads, “the public has had remarkably little<br />

access to information about these forests. Moreover, the<br />

information that does get widely disseminated comes from<br />

government and industry sources that generally convey<br />

the message that all is well.” There has also often been<br />

jurisdictional differences with regards to the availability<br />

of information about Canadian forests. Fortunately, data<br />

availability has recently improved, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong><br />

<strong>Canada</strong> has been a contributor to this improvement in<br />

forest information.<br />

For the past decade, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong> has<br />

worked to compile existing data and to also create new<br />

data on the state of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests to contribute to more<br />

sustainable forest management. We have created this atlas<br />

on <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes using data we have<br />

generated along with other available data and information.<br />

It is part of our national series of projects focused on<br />

intact forest landscapes and anthropogenic changes to our<br />

important forest ecosystems.<br />

7 Wang S. 00 . Managing <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests under a new social contract.<br />

The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : 8 – 90.<br />

8 Wang S. 00 . Wicked problems and metaforestry: is the era of<br />

management over? The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 78: 0 – 0.<br />

9 Yamasaki SH, Kneeshaw DD, Munson AD, Dorion F. 00 .<br />

Bridging boundaries among disciplines and institutions for effective<br />

implementation of criteria and indicators. The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle<br />

78: 87– 9 .<br />

0 Hickey GM. 00 . Regulatory approaches to monitoring sustainable<br />

forest management. International <strong>Forest</strong>ry Review :89–98.<br />

Gillis M, Omule AY, Brierly T. 00 . Monitoring <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests:<br />

the national forest inventory. The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : – .<br />

Schneider RR. 00 . Alternative Futures: Alberta’s Boreal <strong>Forest</strong>s<br />

at the Crossroads. Edmonton AB: Alberta Centre for Boreal Research.<br />

pp.<br />

13 Smith W, Lee P. 2007. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>: influencing<br />

forest policy with information. The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : 8 - 88.

<strong>Canada</strong>’s federal, provincial and territorial governments<br />

and industry hold more detailed data and information,<br />

but many key datasets are not made readily available<br />

to the public for proprietary reasons as well as other<br />

considerations. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>’s focus on<br />

using satellite imagery that is freely available from the<br />

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA),<br />

Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong> and other sources, allowed us to<br />

create consistent data (albeit at a coarse resolution), which<br />

has enabled us to map and evaluate intact forest landscapes<br />

and recent anthropogenic changes to <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest<br />

ecozones.<br />

Our atlas focuses on <strong>Canada</strong>’s last intact forest landscapes<br />

and examines some of their key conservation values,<br />

as well as key indicators of threats to their future<br />

conservation.<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong> has created this atlas to assist<br />

Canadians in their efforts to sustainably manage their<br />

important forest resources.<br />

Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), Liard River Hotsprings<br />

Provincial Park, BC (08/2006)

This project, and many of its data components, was funded<br />

by the Ivey Foundation, Limited Brands, Alberta Ecotrust,<br />

the EJLB Foundation, the International Boreal Conservation<br />

Campaign (through a contract with the Boreal Songbird<br />

Initiative), the Canadian Boreal Initiative, the Conservation<br />

Biology Institute, and an anonymous donor. Their<br />

support is gratefully acknowledged. In addition: through a<br />

contract with Environment <strong>Canada</strong>, we were able to map<br />

recent anthropogenic disturbances within large regions of<br />

woodland caribou range; and, through a contract with the<br />

International Institute for Sustainable Development, we<br />

were able to collect and analyze a variety of data.<br />

We thank the 00+ reviewers from across <strong>Canada</strong> who<br />

have provided comments on our intact forest landscape<br />

mapping, on our anthropogenic change mapping and on<br />

our recently published Atlas of Alberta (Parts I and II).<br />

These individuals, organizations and agencies are specifically<br />

acknowledged in the relevant publications available at<br />

www.globalforestwatch.ca.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We thank those whose valuable feedback and information<br />

contributed to improvements made during the development<br />

of this specific project:<br />

Anita De Wolfe, Francisca Olaya, David Bruinsma, Sina<br />

Sultani, and Robert Boraas provided assistance with analyzing<br />

satellite imagery for disturbances.<br />

Dr. Justina Ray (Wildlife Conservation Society <strong>Canada</strong>)<br />

provided much valuable advice and guidance throughout<br />

the preparation of this atlas. Dr. Fiona Schmiegelow, Dr.<br />

Charles Drever and Aran O’Carroll provided strategic<br />

advice. We are very grateful to the federal, provincial and<br />

territorial governments who made geospatial data available.<br />

The authors thank the suppliers of satellite and other imagery.<br />

The Landsat satellite images used in this work were<br />

obtained from NASA, the <strong>Global</strong> Land Cover Facility at<br />

the University of Maryland, Geogratis (Natural Resources<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>), Dr. Don Leckie (Pacific <strong>Forest</strong>ry Centre), and<br />

Landsat.org

1. Introduction ... 1<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Mapping <strong>Canada</strong>’s Changing Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape ... 1<br />

The importance of intact forest landscapes ... 2<br />

Technical notes on GFWC’s intact forest landscapes methodology and data ... 4<br />

Purpose and Structure of the Atlas ... 5<br />

2. Intact forest landscapes ... 6<br />

Overview ... 6<br />

Tree cover ... 8<br />

Regional analyses ... 10<br />

Ecozone analysis ... 10<br />

Provincial and territorial analysis ... 10<br />

Aboriginal treaties and settled land claims analysis ... 26<br />

Cumulative access in <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones ... 29<br />

Recent anthropogenic changes to <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest landscapes (1990-2001) ... 32<br />

Fragmentation as a result of recent anthropogenic change ... 36<br />

Recent anthropogenic changes (1990-2001) adjacent to intact forest landscape fragments ... 39<br />

3. The best of what’s left ... 41<br />

Soil organic carbon ... 42<br />

Net biome productivity ... 44<br />

Wetlands ... 46<br />

Lakes and rivers ... 48<br />

Potential old growth ... 50<br />

Species diversity ... 52<br />

Reptile and amphibian species ranges ... 52<br />

Bird species ranges ... 54<br />

Mammal species ranges ... 56<br />

Tree species ranges ... 58<br />

Woodland caribou ... 60<br />

Where is the best of what’s left? ... 62<br />

Protected areas ... 66<br />

4. Conclusion ... 69<br />

Glossary ... 70<br />

Appendix 1. Who is GFWC? ... 73<br />

Appendix 2. Methods ... 74<br />

A. Intact forest landscapes ... 74<br />

B. Cumulative access and recent anthropogenic change ... 76<br />

Appendix 3. Data ... 77<br />

A. List of Landsat images used in intact forest landscape mapping ... 77<br />

B. List of species (reptiles and amphibians, mammals, and birds) used in species diversity analysis ... 82

List of Maps<br />

Map 1. <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones of <strong>Canada</strong> ... 3<br />

Map 2. Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes of <strong>Canada</strong> ... 7<br />

Map 3. Tree Cover of <strong>Canada</strong> ... 8<br />

Map 4. Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes of <strong>Canada</strong>: Regional Map Index ... 12<br />

Map Sheet I ... 13<br />

Map Sheet II ... 14<br />

Map Sheet III ... 15<br />

Map Sheet IV ... 16<br />

Map Sheet V ... 17<br />

Map Sheet VI ... 18<br />

Map Sheet VII ... 19<br />

Map Sheet VIII ... 20<br />

Map Sheet IX ... 21<br />

Map Sheet X ... 22<br />

Map Sheet XI ... 23<br />

Map Sheet XII ... 24<br />

Map Sheet XIII ... 25<br />

Map 5. Aboriginal Treaties, Land Claims and Communities and Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes of <strong>Canada</strong> ... 27<br />

Map 6. Cumulative Anthropogenic Access in <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones ... 31<br />

Map 7. Anthropogenic Change (1900-2001) within <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones ... 33<br />

Map 8. Ecodistricts of <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones by Percent Anthropogenic Change (1900-2001) ... 34<br />

Map 9. Watersheds of <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones by Percent Anthropogenic Change (1900-2001) ... 35<br />

Map 10. Ecodistricts of <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones by Percent Fragmented as a Result of Recent Anthropogenic<br />

Change (1900-2001) ... 37<br />

Map 11. Watersheds of <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Ecozones by Percent Fragmented as a Result of Recent Anthropogenic<br />

Change (1900-2001) ... 38<br />

Map 12. Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes (5,000 to 50,000 ha) by Percent Anthropogenic Change (1990-2001)<br />

Occurring Within 20 Kilometres ... 40<br />

Map 13. Soil Organic Carbon Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 43<br />

Map 14. Net Biome Productivity Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 45<br />

Map 15. Wetlands Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 47<br />

Map 16. Lakes and rivers Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 49<br />

Map 17. Potential Old-growth Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 51<br />

Map 18. Reptile and Amphibian Species Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 53<br />

Map 19. Bird Species Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 55<br />

Map 20. Mammal Species Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 57<br />

Map 21. Tree Species Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 59<br />

Map 22. Caribou Occurrence Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 61<br />

Map 23. Example Analysis: Combined Conservation Value Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes ... 64<br />

Map 24. Example Analysis: Combined Conservation Value Within <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes<br />

(Protected Areas) ... 65<br />

Map 25. Protected Areas of <strong>Canada</strong> ... 67

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1. Example: satellite images and GFWC’s extracted changes ... 32<br />

List of Tables<br />

Table 1. <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes by size class ... 6<br />

Table 2. Intact forest landscape (IFL): treed and treeless area by ecozone ... 8<br />

Table 3. <strong>Forest</strong> ecozones: treed and treeless area ... 8<br />

Table 4. Intact forest landscapes by forest ecozone ... 10<br />

Table 5. Intact forest landscapes by province/territory ... 11<br />

Table 6. Intact forest landscapes by Aboriginal treaty ... 28<br />

Table 7. Cumulative access by forest ecozone ... 29<br />

Table 8. Cumulative access in forest ecozones by jurisdiction ... 29<br />

Table 9. Intact forest landscapes fragments adjacent to recent anthropogenic change (1900-2001) by<br />

province ... 39<br />

Table 10. Soil organic carbon content within intact forest landscapes ... 42<br />

Table 11. Net biome productivity of intact forest landscapes (2000-2003) ... 44<br />

Table 12. Wetlands within intact forest landscapes ... 46<br />

Table 13. Wetlands within intact forest landscapes by jurisdiction ... 46<br />

Table 14. Intact forest landscapes within watersheds of varying densities of lakes and major rivers ... 48<br />

Table 15. Potential old growth deciduous, mixed, and conifer forest areas within intact forest landscapes<br />

by jurisdiction ... 50<br />

Table 16. Number of common, endangered, threatened and vulnerable taxa used in species diversity<br />

analyses ... 52<br />

Table 17. Total intact forest landscape area covered by varying levels of reptile and amphibian species<br />

diversity ... 53<br />

Table 18. Total area covered by varying levels of bird species diversity ... 54<br />

Table 19. Total area covered by varying levels of mammal species diversity ... 56<br />

Table 20. Total area covered by varying levels of tree species diversity ... 58<br />

Table 21. Extent of woodland caribou occurrence in jurisdictions and intact forest landscapes ... 60<br />

Table 22a. The seven key Where is the Best of What’s Left? ecological values and their categorization and<br />

ranking ... 63<br />

Table 22b. Individual species diversity ranks that were combined for the species diversity ecological<br />

value ... 63<br />

Table 23. Total protected area (permanent and interim) by ecozone ... 68<br />

Table 24. Status of intact forest landscapes with regards to protected area status ... 68<br />

8 | Introduction

Mapping <strong>Canada</strong>’s Changing<br />

Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape<br />

Canadian forests are important both ecologically and<br />

economically as forests and other woodland cover<br />

percent, or 0 million hectares, of the country’s landmass.<br />

Map on page 9 illustrates the extent of <strong>Canada</strong>’s tree<br />

cover. <strong>Canada</strong> has fifteen ecozones, eleven of which are<br />

considered forest ecozones (see Map ). These eleven<br />

ecozones total just over 80 million hectares.<br />

As with other countries, <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecosystems are not<br />

static and have changed over time. These changes result<br />

from both human and non-human causes. As Canadians<br />

attempt to manage their forests for a range of values, more<br />

information on the amount and types of change to our<br />

forests is essential. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> focuses its efforts<br />

on the provision of spatial data and maps towards this end.<br />

During the past decade, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong><br />

(GFWC) has been mapping <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest landscapes.<br />

In 000, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong> and the World<br />

Resources Institute published <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong>s at a Crossroads:<br />

An Analysis in the Year 2000. This report mapped some<br />

basic indicators of the condition of, and change occurring<br />

in, <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests.<br />

In 00 , GFWC released the report <strong>Canada</strong>’s Large Intact<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes, which was based on an analysis of satellite<br />

imagery that mapped <strong>Canada</strong>’s remaining large intact forest<br />

landscapes, which we defined as areas of at least 50,000<br />

Agriculture and Agri-Foods <strong>Canada</strong>. 999. A National Ecological<br />

Framework for <strong>Canada</strong>. Available at: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/<br />

ecostrat/intro.html ( /0 / 009)<br />

See various reports on <strong>Canada</strong>’s ecozones, including: ( ) Statistics<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. 007. Human Activity and the Environment: Annual Statistics<br />

007 and 008. Catalogue no.: - 0 -XWE. Available at: http://<br />

www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/ - 0 -XIE/ 007000/part .htm<br />

( /0 / 009). ( ) Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong>. The State of <strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

<strong>Forest</strong>s (various annual reports, 99 - 008). Available at: http://<br />

bookstore.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/searchpubs_e.php?ResearchNetworkIDs=RN<br />

0 &PubLanguageID=PL ( /0 / 009).<br />

3 Smith W, Lee P. 2007. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>: influencing forest<br />

policy with information. The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : 8 - 88.<br />

Smith W, Lee P, eds. 000. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong>s at a Crossroads: An Assessment<br />

in the Year 000. Washington DC: World Resources Institute.<br />

Available at: http://www.globalforestwatch.ca/publications_and_maps.<br />

htm ( /0 / 009).<br />

1. Introduction<br />

Birch and conifer forest near Chibougamau, QC (10/2004)<br />

hectares ( 00 km ) within forest ecozones that contain<br />

forest and non-forest ecosystems minimally disturbed by<br />

human activity.<br />

Building upon this work, GFWC then released a report<br />

in 00 titled <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A First<br />

Approximation which mapped the first approximation of<br />

intact forest landscapes and forest fragments, that is, areas<br />

of forest less than 0,000 hectares in size. We used satellite<br />

imagery to map smaller areas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests that<br />

could be considered intact forest landscapes. These areas<br />

ranged from ,000 to 0,000 hectares ( 0- 00 km ) for the<br />

temperate forest ecozones and 0,000 to 0,000 hectares<br />

( 00- 00 km ) for the boreal and taiga ecozones.<br />

Since the completion of that report, GFWC received<br />

funding to refine this analysis and to map even smaller<br />

areas of potentially intact forest landscapes. This project,<br />

entitled “Where is the best of what’s left?” used satellite<br />

The intact forest landscape concept was advanced (and primarily<br />

originally funded) through the World Resources Institute, following<br />

definitions developed by Greenpeace Russia, Socio-Ecological Union<br />

International, and Biodiversity Conservation Center. A large intact forest<br />

landscape is defined by those groups as an area with the following characteristics:<br />

(i) it is situated within a forest zone; (ii) it is at least 0,000 ha;<br />

(iii) it contains a contiguous mosaic of natural ecosystems which may<br />

or may not be of different types; (iv) it is not broken or fragmented by<br />

infrastructure; (v) it does not display signs of significant transformation<br />

caused by human activity. There are a number of additional assumptions<br />

and decision rules that have been used in the actual mapping of large<br />

intact forest landscapes.<br />

GFWC | Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes| 1

imagery to map areas down to ,000 hectares ( 0 km ) for<br />

temperate forest ecozones and down to ,000 hectares ( 0<br />

km ) for boreal/taiga ecozones.<br />

GFWC’s newest dataset based on this work, “<strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A Second Approximation”<br />

( 009) provides a national perspective as well as forest<br />

ecozone and regional perspectives. This dataset was created<br />

by analyzing Landsat imagery from over multiple years,<br />

generally ranging from 988 to 00 , but up to 00 for<br />

some regional areas.<br />

GFWC has not previously published a comprehensive<br />

compilation of the results, nor analysis regarding how<br />

intact forest landscapes intersect with important ecological<br />

and social values that should be considered in sustainable<br />

forest management. That is one purpose of this Atlas, as<br />

discussed in more detail below.<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>’s rationale for our work is<br />

multifold:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

The pace and scale of human activity in <strong>Canada</strong> is<br />

significant. In fact, several governments in <strong>Canada</strong> are<br />

of the opinion that some major regions have “reached<br />

a tipping point;”<br />

Concern about the economic, environmental and social<br />

impacts of human use of forest regions is increasing in<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> and world-wide; 7<br />

Monitoring and understanding the locations,<br />

concentrations and rates of human use in forest<br />

ecozones in efficient and effective ways will serve<br />

to better inform sustainable forest management<br />

decision making; 8<br />

Previous and ongoing research on and monitoring of<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s remaining intact forest landscapes, albeit detailed<br />

and sophisticated in many cases, is incomplete, not publicly<br />

available, local in scale, or species- or sector-specific: there<br />

is a need to report on broader national perspectives.<br />

( ) Alberta Government. 008. Land-use Framework. Available at:<br />

http://www.landuse.alberta.ca/ ( /0 / 009). ( ) Nova Scotia Department<br />

of Natural Resources. 997. Towards Sustainable <strong>Forest</strong>ry: A<br />

Position Paper. Working Paper, 997-0 . Available at: http://www.gov.<br />

ns.ca/natr/publications/forpubs.htm ( /0 / 009).<br />

7 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Hassan R, Scholes R, Ash N,<br />

eds.). 00 . Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends,<br />

Volume , Chapter : <strong>Forest</strong> and Woodland Systems. Available at:<br />

http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document. 90.aspx.<br />

pdf ( /0 / 009).<br />

8 Gillis M, Omule AY, Brierly T. 00 . Monitoring <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests:<br />

the national forest inventory. The <strong>Forest</strong>ry Chronicle 8 : – .<br />

2 | Section 1. Introduction<br />

The importance of intact forest<br />

landscapes<br />

Fallen tree in cedar grove, BC (05/2006)<br />

Remaining tracts of relatively undisturbed, intact natural<br />

forest are important for several reasons:<br />

Conservation value. Small patches of undisturbed<br />

forest landscapes are an important component of<br />

conservation strategies, especially where they are the only<br />

option. 9 However, large patches of natural forest landscape<br />

provide sufficient area for natural ecological processes<br />

which shape the forest ecosystem and provide habitat<br />

for more species 0 and for far-ranging species, such as<br />

woodland caribou and grizzly bears.<br />

Ecosystem goods and services values. Intact<br />

forest landscapes provide a range of ecosystem services,<br />

such as water purification, climate regulation, and carbon<br />

storage.<br />

9 Smaller patches provide habitat for a wide range of species and<br />

are sometimes the only remaining forest landscapes in an ecological or<br />

administrative unit.<br />

0 Lindenmayer D, Fischer J. 00 . Habitat Fragmentation and Landscape<br />

Change: An Ecological and Conservation Synthesis. Washington:<br />

Island Press. 8 pp.<br />

Nogueran R with contributions by Bryant DA, Strittholt J, Kool J.<br />

00 . Low access forests and their level of protection in North America.<br />

Washington DC: World Resources Institute. pp. Available online<br />

at: http://pubs.wri.org/northamericalowaccessforests-pub- 7 .html<br />

( /0 / 009).<br />

Anielski M, Wilson S. 00 . Counting <strong>Canada</strong>’s Natural Capital:<br />

assessing the real value of <strong>Canada</strong>’s boreal ecosystems. A report of<br />

the Pembina Institute for Appropriate Development and the Canadian<br />

Boreal Initiative. 90 pp. Available online at: http://www.borealcanada.<br />

ca/research-cbi-reports-e.php (undergoing revision: /0 / 009).<br />

Map 1 - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

Terrestrial ecozones: Agriculture and Agri-Foods<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. 1999. A National Ecological Framework for<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. Available at: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/<br />

ecostrat/intro.html (10/09/2008).

Map 1.

Recreational, aesthetic, spiritual and heritage<br />

values. As human populations grow and natural forest<br />

is converted to other uses, remaining tracts of relatively<br />

undisturbed forest are increasingly valued for their natural<br />

heritage, spiritual values, and recreational/wilderness<br />

opportunities.<br />

Economic value. Subsidence economies, especially<br />

those involving Aboriginal peoples or tourism, depend on<br />

intact forest landscapes. Tourism, for example, is the<br />

world’s largest industry (and nature/heritage tourism is<br />

the fastest growing component of the tourism sector<br />

worldwide). Although economic information specific<br />

to tourism in forests is not available, expenditures in<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> do depend on sustaining forests’ natural capital.<br />

In the United States, the <strong>Forest</strong> Service has estimated<br />

that recreational activities in national forests contribute<br />

$ 0 billion annually to the GDP, that wild, roadless lands<br />

generate an average value of $ .87 per visitor day, and<br />

that the economic value of recreation on the million<br />

acres of roadless areas in US national forests totals $ 00<br />

million annually.<br />

It is important to map remaining intact forest landscapes<br />

within <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones in order to provide better<br />

information for balancing industry needs and values with<br />

the need for recognition of non-market values, many of<br />

which are associated with relatively undisturbed forests.<br />

Mapping forest fragments provides a baseline from which<br />

future assessments of changes to <strong>Canada</strong>’s remaining forest<br />

fragments can be made and from which further analysis<br />

can be performed to assist forest conservation planning<br />

and decision-making.<br />

Cheakamus Lake, BC (08/2005)<br />

World Travel and Tourism Council. 008. Progress and Priorities<br />

007/ 008. Available at: http://www.wttc.org/bin/pdf/original_pdf_<br />

file/finpp_2007.pdf (14/04/2009).<br />

Worbets B, Berdahl L. 00 . Western <strong>Canada</strong>’s natural capital:<br />

toward a new public policy framework. Available at: http://www.cwf.<br />

ca/V2/files/natcap.pdf (14/04/2009).<br />

Kreiger DJ. 00 . The Economics of <strong>Forest</strong> Ecosystem Services:<br />

A Review. Analysis for the Wilderness Society. Washington, DC. 0 pp.<br />

Available online at: http://wilderness.org/files/Economic-Value-of-<strong>Forest</strong>-Ecosystem-Services.pdf<br />

( /0 / 009).<br />

4 | Section 1. Introduction<br />

Technical notes on GFWC’s intact<br />

forest landscapes methodology<br />

and data<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>’s methodology for mapping intact<br />

forest landscapes involves excluding the following types of<br />

disturbances from potential intact forest landscapes:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Settlements;<br />

Infrastructure used for communication between<br />

settlements and industrial sites; or for industrial<br />

exploitation of natural resources (including roads,<br />

railways, navigable waterways, pipelines, trunk power<br />

transmission lines and other linear disturbances);<br />

Agricultural lands;<br />

Territories disturbed by economic activities during<br />

the last 0-70 years (logging, mining operation sites,<br />

abandoned agricultural lands, etc.);<br />

Artificially restored forests, or tree plantations, if their<br />

existence can be detected on Landsat satellite imagery.<br />

The ratio of forest and non-forest ecosystems within<br />

intact forest landscapes is not a factor in whether an area<br />

is defined as intact or non-intact. The key criteria are an<br />

absence of disturbed territories and infrastructure objects.<br />

Thus, intact forest landscapes may consist primarily of<br />

non-treed ecosystems that are minimally disturbed by<br />

human industrial activity (for example, treeless swamps<br />

or alpine and upper sub-alpine rocky areas in mountains<br />

that are fully surrounded by forest). The exception is<br />

large water bodies. Lakes larger than 0,000 hectares are<br />

excluded from the forest landscape data to avoid situations<br />

where intact forest landscapes are predominantly water.<br />

It should be noted that some human impacts are invisible<br />

from space, such as small forest roads and paths. Other<br />

smaller-scale impacts (including some selective logging)<br />

that occurred more than 0-70 years ago often become<br />

invisible on satellite imagery and indistinguishable from<br />

the natural dynamics of the forest. The maps of <strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

intact forests in Section are based primarily on the visual<br />

interpretation of 988- 00 Landsat images, and some<br />

imagery from the 00 - 00 period. Therefore, only more<br />

recent human impacts are recorded, which means that<br />

there is some overestimation of intact forest landscape<br />

areas despite the buffer exclusion zones applied to the<br />

disturbance layers that were used to create the intact forest<br />

landscape data.

There are some differences between maps and figures in<br />

this Atlas compared to the maps and figures published<br />

in 00 and 00 . 7 Besides the mapping of smaller<br />

intact forest landscapes, there are a few other factors. One<br />

important change in our work involved the use of different<br />

northern boundaries for the forest landscapes. For the<br />

00 analysis, GFWC used a globally derived treeline<br />

boundary. For the 00 and 009 analysis GFWC used<br />

the forest ecozone boundaries as the northern boundary.<br />

The million hectare difference in the total area of intact<br />

forest landscapes between the 00 data and the 009<br />

data is only partially explained ( 0 million hectares) by the<br />

mapping of smaller forest fragments. The majority, 9<br />

million hectares, is due to using a different map projection<br />

for the 009 area calculations. The 00 and 00 analyses<br />

used a standard Lambert Conformal Conic Projection.<br />

The new 009 dataset used the Albers Equal-Area conic<br />

projection, which is consistent with Statistics <strong>Canada</strong>,<br />

who have concluded that Albers is more appropriate for<br />

calculating land area. The remaining million hectare<br />

difference is due to a combination of factors, including<br />

using more detailed lake and island datasets as well as<br />

interpretation improvements (and differences due to using<br />

a different selection of Landsat imagery).<br />

For further details on our intact forest landscape mapping<br />

methodology, please see Appendix .<br />

Lee P, Aksenov D, Laestadius L, Nogueron R, Smith W. 00 .<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s large intact forest landscapes. Edmonton, Alberta: <strong>Global</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>. 8 pp.<br />

7 Lee P, Gysbers JD, Stanojevic Z. 00 . <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape<br />

Fragments: A FirstApproximation (A <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong><br />

Report). Edmonton, Alberta: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>. 97 pp..<br />

Purpose and Structure of the<br />

Atlas<br />

This atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forests is the direct result<br />

of <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>’s project to map the best<br />

remaining forest landscapes of <strong>Canada</strong>. The objective<br />

for this atlas is to provide visually compelling maps and<br />

information of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes as well as<br />

a selection of key indicators related to conservation values<br />

in these areas. The Atlas provides an update on what is<br />

happening to <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests and where to find the best<br />

of what’s left.<br />

Section 1 introduces <strong>Canada</strong>’s changing forests, intact<br />

forest landscapes and why they are important, and the<br />

purpose and structure of the Atlas.<br />

Section 2 of the Atlas describes the concepts of intact<br />

forest landscapes in more detail. It also contains maps and<br />

key facts about <strong>Canada</strong>’s forests and intact forests, at both<br />

national and regional/provincial levels.<br />

Section 3 looks at the “best of what’s left” in intact forest<br />

landscapes in terms of key ecological values. The intact<br />

forest landscapes are evaluated and mapped with overlays<br />

and analyses of key ecological values including soil organic<br />

carbon, wetlands, lakes and major rivers, old growth<br />

forests, species diversity, and key focal species. A final<br />

map combines all of these ecological values indicators and<br />

identifies potential key opportunities for sustainable forest<br />

management in <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

Section 4 provides an overview of the current state of<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s protected area network and how this network<br />

intersects with the distribution of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest<br />

landscapes.<br />

Section 5 concludes with a summary of the project and its<br />

major findings, implications of this work, lessons learned<br />

and future research recommendations.<br />

GFWC | Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes| 5

Overview<br />

This section provides a series of maps<br />

that illustrates both a national and<br />

regional perspective on the distribution of<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes, a map<br />

that shows the distribution of tree cover<br />

within intact forest landscapes, and the<br />

key results of our analysis.<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes, as<br />

mapped by GFWC, are located where<br />

there is the least amount of human<br />

impact. To highlight the inverse, this<br />

section also includes a map of cumulative<br />

access within <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones<br />

and maps of changes in <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest<br />

landscape between 990 and 00 .<br />

As well as providing analysis and maps in the context of<br />

jurisdictions and forest ecozones, some additional analysis<br />

and maps are provided in the context of ecodistricts in<br />

order to understand finer levels of distributions of intact<br />

forest landscapes and anthropogenice changes to forest<br />

landscapes. Ecodistricts are subdivisions of ecoregions,<br />

which in turn are subdivisions of ecozones and they are<br />

characterized by distinctive assemblages of landform,<br />

relief, surficial geologic material, soil, water bodies,<br />

vegetation, and land uses.<br />

Map illustrates the distribution of intact forest landscapes<br />

within <strong>Canada</strong>. GFWC’s analysis has identified 488 million<br />

hectares of intact forest landscape in <strong>Canada</strong> within the<br />

eleven forest ecozones. This represents 7 % of the total<br />

area of these ecozones.<br />

It is important to note that GFWC has mapped a range of<br />

intact forest landscapes in terms of size. GFWC defines a<br />

large intact forest landscape as any area of at least 0,000<br />

hectares ( 00 km ) within a forest ecozone that contains<br />

forest and non-forest land cover minimally disturbed<br />

by human economic activity. An intact forest landscape<br />

fragment is any area between ,000 to 0,000 hectares ( 0<br />

to 00 km ) in a temperate forest ecozone and between<br />

,000 and 0,000 hectares ( 0 to 00 km ) in a boreal/taiga<br />

forest ecozone.<br />

6 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Table 1. <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes by size class.<br />

Size class (ha)<br />

Number of Area (ha)<br />

intact forest Polygons of Islands<br />

landscape 1,000 ha and considered<br />

polygons larger intact<br />

Total area<br />

(ha)<br />

%<br />

Total<br />

area<br />

250,000 89 425,570,450 298,292 425,868,742 87.2<br />

Total 7,359 485,948,580 2,247,246 488,195,826 100.0<br />

Table provides statistics on the relative size of <strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

intact forest landscapes. A total of million hectares<br />

(87%) of all intact forest landscapes are 0,000 hectares<br />

or larger while another . million hectares are between<br />

0,000 and 00,000 hectares in size.<br />

There are . million hectares of ,000 to ,000 hectare<br />

intact forest landscape fragments and 7.9 million hectares<br />

of ,000 to 0,000 hectare intact forest landscape<br />

fragments in temperate forest ecozones.<br />

There are also just over 00,000 hectares of intact forest<br />

landscapes in islands smaller than ,000 hectares. Islands<br />

were considered a special case for identification because<br />

of their setting in an aquatic environment (marine and<br />

freshwater). There are also many islands of larger size<br />

that are considered part of the total area of intact forest<br />

landscapes.<br />

Map 2 - key data source:<br />

•<br />

Intact forest landscapes: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

2009. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A<br />

Second Approximation. Available at: http://www.<br />

globalforestwatch.ca/datawarehouse/datawarehouse.<br />

htm (15/05/2009).

Map 2.

Tree cover<br />

As shown in Map , <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones are not<br />

completely covered with forest (defined as tree cover of<br />

more than 0%), thus neither are intact forest landscapes.<br />

As evident in Table , approximately % of intact forest<br />

landscapes are actually forested.<br />

Six ecozones (Atlantic Maritime, Boreal<br />

Shield, Hudson Plains, the Montane<br />

Cordillera, Taiga Plains and Boreal<br />

Plains) have more than 0% forest<br />

cover within their intact forest. The<br />

Taiga Cordillera ecozone is the least<br />

forested with only 0% tree cover and<br />

the Mixed Wood Plains ecozone is the<br />

second least forested at %.<br />

GFWC’s analysis reveals that the overall<br />

percentage of tree cover in intact forest<br />

landscapes is almost the same as the<br />

overall percentage of tree cover in<br />

forest ecozones (see Tables and ).<br />

However, there are some exceptions:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Although the Mixed Wood Plains<br />

ecozone is only % tree covered<br />

in general, over % of its intact<br />

forest landscape area is treecovered.<br />

Both the Pacific Maritime and<br />

the Taiga Cordillera ecozones<br />

have high proportions of nontreed<br />

areas within intact forest<br />

landscapes compared to the other<br />

ecozones. The Pacific Maritime has<br />

just under 0% tree cover in intact<br />

The Spectrum Range in northern British Columbia (08/2006)<br />

8 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Table 2. Intact forest landscapes (IFL): treed and treeless area by ecozone.<br />

Ecozone<br />

Total IFL<br />

area (ha)<br />

Treed area<br />

(ha)<br />

Treeless area<br />

(ha)<br />

Percent<br />

treed<br />

Percent<br />

treeless<br />

Atlantic Maritime 1,836,928 1,704,961 131,967 92.2 7.2<br />

Boreal Cordillera 44,540,877 19,266,120 25,274,757 43.3 56.8<br />

Boreal Plains 27,517,456 19,062,822 8,454,634 69.3 30.7<br />

Boreal Shield 127,849,511 97,431,966 30,417,545 76.2 23.8<br />

Hudson Plains 36,797,505 24,819,293 11,978,212 67.5 32.6<br />

Mixed Wood Plains 175,258 116,555 58,703 66.5 33.5<br />

Montane Cordillera 26,672,966 13,806,738 12,866,228 51.8 48.2<br />

Pacific Maritime 14,380,619 4,287,111 10,093,508 29.8 70.2<br />

Taiga Cordillera 26,125,048 2,625,891 23,499,157 10.1 90.0<br />

Taiga Plains 48,124,275 29,926,595 18,197,680 62.2 37.8<br />

Taiga Shield 134,175,383 60,631,459 73,543,924 45.2 54.8<br />

Total 488,195,825 273,679,511 214,516,314 56.1 43.9<br />

Table 3. <strong>Forest</strong> ecozones: treed and treeless area.<br />

Ecozone<br />

Total area<br />

(ha)<br />

Treed area<br />

(ha)<br />

Treeless area Percent<br />

(ha) treed<br />

Percent<br />

treeless<br />

Atlantic Maritime 20,151,483 16,766,636 3,384,846 83.2 16.8<br />

Boreal Cordillera 47,071,039 20,782,040 26,289,000 44.2 55.9<br />

Boreal Plains 74,062,933 42,446,471 31,616,462 57.3 42.7<br />

Boreal Shield 188,640,692 146,991,133 41,649,559 77.9 22.1<br />

Hudson Plains 37,565,744 25,141,285 12,424,459 66.9 33.1<br />

Mixed Wood Plains 11,339,105 2,643,525 8,695,580 23.3 76.7<br />

Montane Cordillera 48,975,931 31,587,882 17,388,049 64.5 35.5<br />

Pacific Maritime 20,873,620 9,109,313 11,764,307 43.6 56.4<br />

Taiga Cordillera 26,695,320 2,766,180 23,929,140 10.4 89.6<br />

Taiga Plains 65,773,771 40,690,528 25,083,243 61.9 38.1<br />

Taiga Shield 139,314,737 61,444,990 77,869,747 44.1 55.9<br />

Total 680,464,374 400,372,056 280,092,319 58.8 41.2<br />

Map 3 - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

forest landscapes despite having % tree cover overall<br />

throughout the ecozone. The Taiga Cordillera has 0%<br />

tree cover throughout the entire ecozone and 0% tree<br />

cover in intact forest landscapes.<br />

Intact forest landscapes: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

2009. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A<br />

Second Approximation. Available at: http://www.<br />

globalforestwatch.ca/datawarehouse/datawarehouse.<br />

htm (15/05/2009).<br />

Tree canopy cover: DeFries R, Hansen M, Townshend<br />

JRG, Janetos AC, Loveland TR. 2000. 1 Kilometer<br />

Tree Cover Continuous Fields, 1.0, Department of<br />

Geography, University of Maryland, College Park,<br />

Maryland, 1992-1993. Available at: http://glcf.umiacs.<br />

umd.edu/data/treecover/ (14/04/2009).

Map 3.

Regional analyses<br />

The following pages present maps and analyses on an<br />

ecozone and a provincial basis. These results highlight the<br />

variation in area of intact forest landscapes (see Tables<br />

and ). The distribution of the intact forest landscapes are<br />

illustrated regionally in Map Sheets I-XIII; Map provides<br />

the regional index for these maps.<br />

Ecozone analysis<br />

The Boreal Cordillera, Taiga Cordillera, Taiga Shield and<br />

Hudson Plains are the most intact of the eleven forest<br />

ecozones, with each having over 9 % of their total land<br />

area in intact forest landscapes.<br />

The Boreal Shield, the largest forest ecozone in <strong>Canada</strong>, is<br />

8% intact. By contrast, the the Boreal Plains is only 7%<br />

( . million ha) intact.<br />

The four temperate forest ecozones (Atlantic Maritime,<br />

Mixed Wood Plains, Montane Cordillera and Pacific<br />

Maritime) account for just under 9% of the intact forest<br />

landscapes in <strong>Canada</strong>. However, given the relatively small<br />

areas of these ecozones, the proportion of intact forest<br />

landscapes is of more importance than the total area.<br />

The Mixed Wood Plains of southern Ontario and Québec<br />

is not only the smallest forest ecozone, it is also the least<br />

intact (see Map on page 7 and Map Sheet XI). It has no<br />

large intact forest landscapes and only %, or 7 , 8 ha,<br />

is made up of intact forest landscape fragments of ,000 to<br />

0,000 ha.<br />

The Atlantic Maritime Ecozone is the second least intact<br />

forest ecozone. Only 9% (or . 7 million ha) of its area<br />

Table 4. Intact forest landscapes (IFL) by forest ecozone.<br />

Ecozone<br />

Ecozone area<br />

(ha)<br />

10 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Total area of<br />

intact forest<br />

landscapes (ha)<br />

Ecozone:<br />

percent<br />

intact<br />

comprises intact forest landscapes (see Map and Map<br />

Sheet XIII), most of which (80%) is made up of intact<br />

forest landscape fragments versus large intact forest<br />

landscapes.<br />

Relative to the Mixed Wood Plains and Atlantic Maritime<br />

ecozones, the Montane Cordillera and Pacific Maritime<br />

ecozones retain a greater degree of intact forest landscapes<br />

( % and 9% respectively).<br />

Provincial and territorial analysis<br />

There is significant variation in the percentage of<br />

intact forest landscapes by jurisdiction in <strong>Canada</strong>. Four<br />

jurisdictions - Québec, Northwest Territories, Ontario and<br />

British Columbia - each contain over 0% of the total area<br />

of large intact forest landscapes. Together, they contain<br />

% of all of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes.<br />

Manitoba and the Yukon Territory each contain about<br />

9- 0% of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes. Thus, six<br />

jurisdictions contain approximately 80% of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact<br />

forest landscapes.<br />

Five other jurisdictions contain relatively little intact forest<br />

landscape. Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia each<br />

contain less than % while Nunavut has % and Alberta<br />

has %. Newfoundland and Labrador contains less than<br />

7% of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscapes.<br />

The territories have relatively high proportions of their<br />

forest ecozones in intact forest landscapes: the Yukon has<br />

9 % intact, the Northwest Territories has 87% intact and<br />

Nunavut has 00% intact. Together, the three territories<br />

account for almost 9% of the total intact<br />

forest landscapes in <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

Proportion<br />

of total IFL<br />

area (%)<br />

Atlantic Maritime 20,151,483 1,836,928 9.1 0.4<br />

Boreal Cordillera 47,071,039 44,540,876 94.6 9.1<br />

Boreal Plains 74,062,933 27,517,456 37.2 5.6<br />

Boreal Shield 188,640,692 127,849,511 67.8 26.2<br />

Hudson Plains 37,565,744 36,797,504 98 .0 7.5<br />

Mixed Wood Plains 11,339,105 175,258 1.5 >0.1<br />

Montane Cordillera 48,975,931 26,672,966 54.5 5.5<br />

Pacific Maritime 20,873,620 14,380,619 68.9 3.0<br />

Taiga Cordillera 26,695,320 26,125,048 97.9 5.4<br />

Taiga Plains 65,773,771 48,124,275 73.2 9.8<br />

Taiga Shield 139,314,737 134,175,383 96.3 27.5<br />

Total 680,464,374 488,195,825 71.7 100.0<br />

Alberta has almost 0 million ha of intact<br />

forest landscape, which represents 9% of<br />

its forest ecozone area. This percentage<br />

places Alberta in tenth place in terms of<br />

percent intactness compared to the other<br />

provinces and territories. Alberta’s 0<br />

million ha represents % of <strong>Canada</strong>’s total<br />

intact forest landscapes.<br />

British Columbia has 9 .7 million ha<br />

of land area within forest ecozones.<br />

Approximately 8 million ha are considered<br />

intact, of which 0 million ha are large

intact forest landscapes and 7.7 million ha are intact forest<br />

landscape fragments. British Columbia’s intact forest<br />

landscapes account for almost % of <strong>Canada</strong>’s total intact<br />

forest landscapes – the fourth highest percentage overall<br />

after Québec, the Northwest Territories and Ontario.<br />

British Columbia has the largest amount of intact forest<br />

landscape fragments of all provinces and territories.<br />

In Saskatchewan, of million ha of forest ecozone<br />

area are considered intact, which represents 7 % of the<br />

total forest ecozone area. The province has just over %<br />

of the total intact forest landscapes in <strong>Canada</strong>. Trees cover<br />

just over 77% of the large intact forest landscapes and<br />

almost 78% of the intact forest landscape fragments.<br />

Manitoba has .8 million ha (or<br />

8 %) of intact forest landscape<br />

area within its 7.9 million ha of<br />

forest ecozone.<br />

Ontario has . million ha of<br />

intact forest landscapes in its 98.9<br />

million ha of forest ecozone area<br />

(representing 7% of the total<br />

area). The province has the third<br />

highest percentage (almost 9%)<br />

of <strong>Canada</strong>’s intact forest landscape<br />

fragments, after British Columbia<br />

and Québec.<br />

Québec has the largest total area<br />

composed of forest ecozones:<br />

0. million ha in total. Of<br />

this area, 9 . million ha (70%)<br />

is composed of intact forest<br />

landscapes.<br />

East of Québec City, QC (10/2004)<br />

Prince Edward Island has only 9 ,000 ha of forest<br />

ecozone area, none of which is intact. New Brunswick<br />

has 7. million ha of forest ecozone area, of which only<br />

7,000 ha (or %) are intact. These provinces only<br />

contain intact forest landscape fragments; there are no<br />

large intact forest landscapes of at least 0,000 hectares.<br />

Nova Scotia fares slightly better than New Brunswick.<br />

It contains . million ha of forest ecozones of which<br />

9 ,000 ha (or 7%) are intact forest landscapes. Of this,<br />

7 ,000 ha (almost 7 %) are large intact forest landscapes<br />

while 9,000 ( %) are intact forest landscape fragments.<br />

Table 5. Intact forest landscapes by province/territory.<br />

Province<br />

<strong>Forest</strong><br />

ecozone area<br />

(ha)<br />

Intact forest<br />

landscape<br />

area (ha)<br />

Percent of<br />

forest ecozones<br />

covered by<br />

intact forest<br />

landscapes<br />

Proportion<br />

of total<br />

intact forest<br />

landscapes<br />

area (%)<br />

Alberta 50,672,649 19,974,967 39.4 4.1<br />

British Columbia 94,709,033 58,119,773 61.4 11.9<br />

Manitoba 57,883,340 46,764,179 80.8 9.6<br />

New Brunswick 7,299,874 257,178 3.5 0.1<br />

Newfoundland and<br />

Labrador<br />

39,022,812 33,620,392 86 .2 6.9<br />

Northwest Territories 95,539,825 83,556,502 87.5 17.1<br />

Nova Scotia 5,562,603 943,188 17.0 0.2<br />

Nunavut 10,786,309 10,744,947 99.6 2.2<br />

Ontario 98,953,976 66,372,280 67 .1 13.6<br />

Prince Edward Island 593,012 0 0 0<br />

Québec 130,430,760 91,374,828 70.1 18.7<br />

Saskatchewan 41,158,212 31,092,779 75.5 6.4<br />

Yukon Territory 47,851,969 45,371,883 94.8 9.3<br />

Total 680,464,374 488,195,825 71.2 100.0<br />

Map 4 & Map Sheets I-XIII - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Intact forest landscapes: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

2009. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A Second<br />

Approximation. Available at: http://www.globalforestwatch.<br />

ca/datawarehouse/datawarehouse.htm (15/05/2009).<br />

Land cover: Multi-temporal land cover maps of <strong>Canada</strong> using<br />

NOAA AVHRR 1-km data from 1985-2000. Available at: http://<br />

www.geogratis.ca/geogratis/en/download/thematic0.html<br />

(14/04/2009).<br />

Terrestrial ecozones: Agriculture and Agri-Foods <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

1999. A National Ecological Framework for <strong>Canada</strong>. Available<br />

at: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/ecostrat/intro.html<br />

(14/04/2009).<br />

GFWC | Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes| 11

Map 4.

Aboriginal treaties and settled land claims analysis<br />

Aboriginal people have rights and legal status concerning<br />

forested lands due to their historical presence in what<br />

is now <strong>Canada</strong>, and to the entrenchment of Aboriginal<br />

and treaty rights in the Constitution Act, 98 . However,<br />

although Aboriginal and treaty rights (including rights<br />

to fish, trap and hunt) were recognized in section 35 of<br />

the Constitution Act of 98 , these rights continue to be<br />

clarified and resolved today through negotiated treaties<br />

and court decisions. This situation exists in part because<br />

courts have declared that existing Aboriginal rights “must<br />

be interpreted flexibly so as to permit their evolution over<br />

time” (R v. Sparrow, [ 990] S.C.R. 07 ). The outcomes<br />

of these processes on Aboriginal rights, treaties, and land<br />

claims have the potential to change the way forests in<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> are owned and managed in the future.<br />

Map shows the locations of Aboriginal treaties and<br />

land claims in relation to the distribution of intact forest<br />

landscapes. Table (page 8) provides a summary of<br />

the area of intact forest landscape within each treaty. As<br />

the study area of GFWC’s project only covered the<br />

forest ecozones, the statistics do not refer to the complete<br />

coverage of land claim and treaty area in <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

Three historic treaty areas each have over 90% of their<br />

area covered by intact forest landscapes: Treaties ( 908),<br />

9 ( 9 9/ 0), and 0 ( 90 ). These three treaty areas<br />

Smith W. and P. Lee, eds. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong>s at a Crossroads: An Assessment<br />

in the Year 000. (World Resources Institute and <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>.) Victoria BC: Beacon Hill Communications Gp. Inc.<br />

Available at: http://www.globalforestwatch.ca ( /0 / 009).<br />

26 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Bird feather, SK (10/2005)<br />

comprise just over 0% of all the historic treaties and<br />

almost % of all the intact forest landscapes within all<br />

historic treaties.<br />

Six other historic treaties have 0% to 90% of their area<br />

covered by intact forest landscape: Treaties ( 87 ),<br />

( 87 ), ( 889), 8 ( 899), 9 ( 90 /0 ), ( 9 ). These<br />

six treaty areas comprise almost % of all the historic<br />

treaties and 0% of intact forest landscapes within all<br />

historic treaties.<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> has more than 7,0 7, hectares of modern<br />

settled land claims with Aboriginal people. Of these land<br />

claims, 7, 78,70 hectares – or % of the entire area<br />

– are composed of intact forest landscapes.<br />

Map 5 - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Intact forest landscapes: <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

2009. <strong>Canada</strong>’s <strong>Forest</strong> Landscape Fragments: A<br />

Second Approximation. Available at: http://www.<br />

globalforestwatch.ca/datawarehouse/datawarehouse.<br />

htm (15/05/2009).<br />

Land cover: Multi-temporal land cover maps of <strong>Canada</strong><br />

using NOAA AVHRR 1-km data from 1985-2000. Available<br />

at: http://www.geogratis.ca/geogratis/en/download/<br />

thematic0.html (14/04/2009).<br />

Aboriginal Treaties and Land Claims: <strong>Canada</strong> Centre for<br />

Cadastral Management, Geomatics <strong>Canada</strong>, Natural<br />

Resources <strong>Canada</strong>. 2008. National Framework <strong>Canada</strong><br />

Lands Administrative Boundaries Level 1. Available at:<br />

http://www.geogratis.ca/ (14/04/2009).

Map 5.

Table 6. Intact forest landscapes by Aboriginal treaty.<br />

Treaty name<br />

28 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Treaty area<br />

(ha)<br />

Intact forest<br />

landscapes<br />

(ha)<br />

Percent<br />

intact<br />

Treaty 1 1871 4,907,721 152,192 3.1<br />

Treaty 2 1871 8,747,873 1,184,207 13.5<br />

Treaty 3 1873 12,638,255 7,510,679 59.4<br />

Treaty 4 1874 19,306,653 1,025,279 5.3<br />

Treaty 5 1875 16,648,621 12,364,512 74.3<br />

Treaty 5 1908 34,177,287 32,470,547 95.0<br />

Treaty 6 1876 29,904,766 3,506,947 11.7<br />

Treaty 6 1889 3,252,415 2,486,204 76.4<br />

Treaty 7 1877 10,848,100 1,110,174 10.2<br />

Treaty 8 1899 84,875,431 51,548,905 60.7<br />

Treaty 9 1905/06 23,021,590 15,337,147 66.6<br />

Treaty 9 1929/30 35,658,471 35,415,555 99.3<br />

Treaty 10 1906 20,504,188 19,449,598 94.9<br />

Treaty 11 1921 97,839,956 67,901,986 69.4<br />

Peace and Friendship Treaties 12,681,597 1,176,727 9.3<br />

Manitoulin Island Treaty 1862 306,600 51,144 16.7<br />

Robinson-Huron 1850 6,327,792 2,672,369 42.2<br />

Robinson-Superior 1850 8,394,349 4,003,855 47.7<br />

Upper <strong>Canada</strong> Treaties 8,373,831 387,928 4.6<br />

Chekonein (Shonghees) 30 April 1850 3,311 0 0.0<br />

Chewhaytsum (Beecher Bay) 1 May 1850 6,508 12 0.2<br />

Chilcowitch (Songhees) 30 April 1850 1,371 13 0.9<br />

Kakyaakan (Beecher Bay) 1 May 1850 5,246 0 0.0<br />

Kosampson (Esquimalt) 30 April 1850 5,017 0 0.0<br />

North Saanich 11 February 1852 22,226 0 0.0<br />

Quakeolth (Kwakiutl) 8 February 1851 4,085 97 2.4<br />

Queackar (Kwakiutl) 8 February 1851 4,084 330 8.1<br />

Saalequun (Nanaimo, Nanoose) 23 December 1854 4,076 0 0.0<br />

Soke (Sook) 1 May 1850 32,380 440 1.4<br />

South Saanich (Malahat) 7 February 1852 4,959 0 0.0<br />

Swengwhung (Songhees) 30 April 1850 2,234 0 0.0<br />

Teechamitsa (Songhees) 29 April 1850 5,499 0 0.0<br />

Whyomilth (Songhees) 30 April 1850 5,067 0 0.0<br />

Williams Treaties 1923 4,845,873 1,163,369 24.0<br />

Total 1 443,367,433 260,920,216 58.8<br />

1 As the study area of GFWC’s project only covered the 11 forest ecozones, these statistics do not refer<br />

to the complete coverage of land claim and treaty area in <strong>Canada</strong>.

Cumulative access in <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones<br />

Powerlines near Saguenay, QC (10/2004)<br />

Cumulative access is the combined impact of industrial<br />

activities, which include, but are not limited to, roads,<br />

mines, clearcuts, wellsites, pipelines, transmission lines, and<br />

agricultural clearings.<br />

GFWC has analyzed the extent to which <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest<br />

ecozones have been impacted by human activities. GFWC’s<br />

cumulative access layer was compiled by analyzing Landsat<br />

(TM and ETM) satellite images for the period 988 to<br />

00 . All visible infrastructure and other human activities<br />

on the images were mapped and buffered by 00 metres.<br />

Map provides a national picture of the cumulative extent<br />

of access within <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones. Table 7 presents<br />

the area and percentage results of access by forest ecozone<br />

as well as nationally.<br />

The results indicate that just over percent of the total<br />

area of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones is accessed. From a<br />

Table 7. Cumulative access by forest ecozone.<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> ecozone<br />

Ecozone<br />

area (ha)<br />

Area of<br />

ecozone<br />

accessed<br />

(ha)<br />

Percent<br />

of<br />

ecozone<br />

accessed<br />

Atlantic Maritime 20,151,483 15,399,153 76.4<br />

Boreal Cordillera 47,071,039 2,236,683 4.8<br />

Boreal Plains 74,062,933 33,355,347 45.0<br />

Boreal Shield 188,640,692 45,948,003 24.4<br />

Hudson Plains 37,565,744 600,800 1.6<br />

Mixed Wood Plains 11,339,105 8,536,603 75.3<br />

Montane Cordillera 48,975,931 19,811,286 40.5<br />

Pacific Maritime 20,873,620 5,689,362 27.3<br />

Taiga Cordillera 26,695,320 499,065 1.9<br />

Taiga Plains 65,773,771 9,620,222 14.6<br />

Taiga Shield 139,314,737 3,915,278 2.8<br />

Total 680,464,374 145,611,802 21.4<br />

regional perspective, the most accessed are the eastern<br />

Atlantic Maritime and the Mixed Wood ecozones, with<br />

each being more than 7 % accessed. The Boreal Plains<br />

and the Montane Cordillera ecozones are also significantly<br />

accessed at % and 0%, respectively.<br />

The most northern and remote forest ecozones (the Boreal<br />

Cordillera, the Taiga Shield, the Taiga Cordillera and the<br />

Hudson Plains) each have less than % cumulative access.<br />

Table 8 provides statistics on the percentage of accessed<br />

forest ecozone by Province. Four jurisdictions – Alberta,<br />

British Columbia, Ontario and Québec – contain almost<br />

77% of <strong>Canada</strong>’s accessed forest ecozone area.<br />

The three maritime provinces (New Brunswick, Prince<br />

Edward Island and Nova Scotia) each have over 70% of<br />

their forest ecozones accessed. Alberta is the fourth most<br />

accessed province at 7%.<br />

Six jurisdictions – British Columbia, Ontario, Québec,<br />

Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Manitoba<br />

– each have between 0% and % of their forest ecozone<br />

area accessed. The Northwest Territories, Yukon and<br />

Nunavut each have less than % of their forest areas<br />

accessed.<br />

Table 8. Cumulative access in forest ecozones by jurisdiction.<br />

Province/territory<br />

Provincial/<br />

territorial<br />

forest<br />

ecozone area<br />

(ha)<br />

Area of<br />

forest<br />

ecozone<br />

accessed<br />

(ha)<br />

Percent<br />

of forest<br />

ecozone<br />

accessed<br />

New Brunswick 7,299,874 5,911,681 81.0<br />

Prince Edward<br />

Island<br />

593,012 437,852 73.8<br />

Nova Scotia 5,562,603 3,948,814 71.0<br />

Alberta 50,672,649 23,837,235 47.0<br />

British Columbia 94,709,033 31,385,860 33.1<br />

Ontario 98,953,976 25,727,265 26.0<br />

Québec 130,430,760 30,875,057 23.7<br />

Saskatchewan 41,158,212 6,730,055 16.4<br />

Newfoundland and<br />

Labrador<br />

39,022,812 4,512,746 11.6<br />

Manitoba 57,883,340 5,909,506 10.2<br />

Northwest<br />

Territories<br />

95,539,825 4,243,873 4.4<br />

Yukon 47,851,969 2,090,600 4.4<br />

Nunavut 10,786,309 1,258 0.0<br />

Total 680,464,374 145,611,802 21.4<br />

GFWC | Atlas of <strong>Canada</strong>’s Intact <strong>Forest</strong> Landscapes| 29

30 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

Map 6 - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Cumulative anthropogenic (primarily industrial) access<br />

dataset (“<strong>Canada</strong> Access- Combined”) created by <strong>Global</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong>. 2009. Available at: http://www.<br />

globalforestwatch.ca/datawarehouse/datawarehouse.<br />

htm (14/04/2009).<br />

Terrestrial ecozones: Agriculture and Agri-Foods <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

1999. A National Ecological Framework for <strong>Canada</strong>.<br />

Available at: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/ecostrat/<br />

intro.html (14/04/2009). (<strong>Forest</strong> ecozones are those<br />

11 terrestrial ecozones that have 15% or more forest<br />

cover and include: Atlantic Maritime, Mixed Wood<br />

Plains, Boreal Cordillera, Boreal Plains, Boreal Shield,<br />

Hudson Plains, Taiga Cordillera, Taiga Plains, Taiga Shield,<br />

Montane Cordillera, Pacific Maritime.)

Map 6.

Recent anthropogenic changes to <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest landscapes<br />

(1990-2001)<br />

As well as mapping and analyzing<br />

long term cumulative access due to<br />

human activities within <strong>Canada</strong>’s<br />

forest ecozones, GFWC has also<br />

mapped recent industrial-caused<br />

changes for a large study area, for<br />

which we measured the amount<br />

and rate of industrial change over<br />

time. GFWC selected a ,89 ,000<br />

km study area that covers %<br />

of <strong>Canada</strong>’s forest ecozones. This<br />

study area was selected as it is an<br />

“interface” zone, where major<br />

industrial activities are advancing<br />

into intact forest landscapes.<br />

GFWC employed a standard<br />

methodology to detect<br />

anthropogenic changes throughout<br />

these forested landscapes. Satellite images of earlier years<br />

(from the 98 to 99 period) were compared to more<br />

recent scenes (from the 000 to 00 period) to measure<br />

the changes to forest landscapes for an approximately -<br />

year period ( 990- 00 ).<br />

This study area includes portions of eight jurisdictions (British Columbia,<br />

Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec, Yukon and<br />

Northwest Territories) and portions of six forest ecozones (Montane<br />

Cordillera, Taiga Plains, Boreal Plains, Boreal Shield and Hudson Plains).<br />

32 | Section 2. Intact forest landscapes<br />

A<br />

Maps 7-9 - key data sources:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

B C<br />

Figure 1. Example: satellite images and GFWC’s extracted changes. (A) September 15, 1990;<br />

(B) September 16, 1999; (C) GFWC’s extracted changes. (Landsat images, Path 45/Row 22)<br />

Maps 7-9 show that within some jurisdictions and<br />

ecological units there is significant recent anthropogenic<br />

change. For example:<br />

• Alberta, Ontario and Québec have had more than<br />

a 0% change in a number of their ecodistricts<br />

(five, five and three, respectively) in the 12 year<br />

period within the study area.<br />

• Ontario has had eleven watersheds and Québec<br />

has had five watersheds more than 10% changed<br />

during the year period).<br />

Anthropogenic change data: unpublished 2008 <strong>Global</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> <strong>Canada</strong> data mapped from Landsat<br />

imagery - multi-spectral scanner.<br />

Watersheds (Fundamental Drainage Areas):<br />

Government of <strong>Canada</strong>, Natural Resources <strong>Canada</strong>,<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> Centre for Remote Sensing, The Atlas of<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. 2003. National Scale Frameworks Hydrology -<br />

Drainage Areas, <strong>Canada</strong>. Available at: http://geogratis.<br />

cgdi.gc.ca/download/frameworkdata/drainage_areas/<br />

(14/04/2009).<br />

Terrestrial ecozones: Agriculture and Agri-Foods<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. 1999. A National Ecological Framework for<br />

<strong>Canada</strong>. Available at: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/<br />

ecostrat/intro.html (14/04/2009).

Map 7.

Map 8.

Map 9.

Fragmentation as a result of recent anthropogenic change<br />

In addition to amount of change, fragmentation is an<br />

important measure of the impact of anthropogenic<br />

changes within ecological units. Fragmentation is the<br />

breaking up of a habitat, ecosystem or landscape into<br />

smaller, disconnected pieces. Although natural disturbances<br />

fragment the landscape, human activities are also agents of<br />

fragmentation. Examples of anthropogenic fragmentation<br />

include roads, cleared lands, urbanization and other human<br />

developments. Some conservationists identify habitat<br />