International government debt - UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 199

International government debt - UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 199

International government debt - UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 199

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

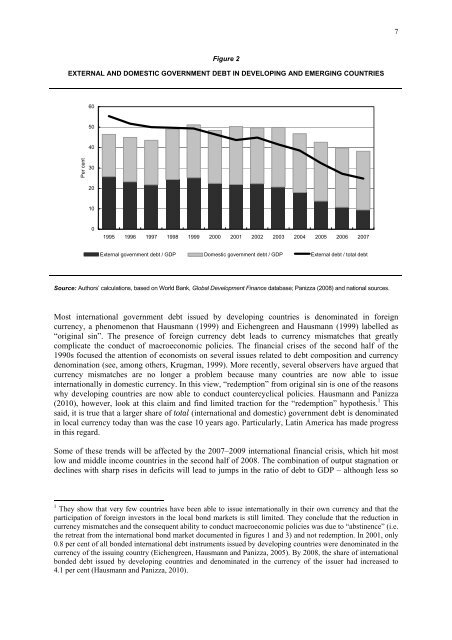

Figure 2<br />

EXTERNAL AND DOMESTIC GOVERNMENT DEBT IN DEVELOPING AND EMERGING COUNTRIES<br />

Per cent<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

<strong>199</strong>5 <strong>199</strong>6 <strong>199</strong>7 <strong>199</strong>8 <strong>199</strong>9 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007<br />

External <strong>government</strong> <strong>debt</strong> / GDP Domestic <strong>government</strong> <strong>debt</strong> / GDP External <strong>debt</strong> / total <strong>debt</strong><br />

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on World Bank, Global Development Finance database; Panizza (2008) and national sources.<br />

Most international <strong>government</strong> <strong>debt</strong> issued by developing countries is denominated in foreign<br />

currency, a phenomenon that Hausmann (<strong>199</strong>9) and Eichengreen and Hausmann (<strong>199</strong>9) labelled as<br />

“original sin”. The presence of foreign currency <strong>debt</strong> leads to currency mismatches that greatly<br />

complicate the conduct of macroeconomic policies. The financial crises of the second half of the<br />

<strong>199</strong>0s focused the attention of economists on several issues related to <strong>debt</strong> composition and currency<br />

denomination (see, among others, Krugman, <strong>199</strong>9). More recently, several observers have argued that<br />

currency mismatches are no longer a problem because many countries are now able to issue<br />

internationally in domestic currency. In this view, “redemption” from original sin is one of the reasons<br />

why developing countries are now able to conduct countercyclical policies. Hausmann and Panizza<br />

(2010), however, look at this claim and find limited traction for the “redemption” hypothesis. 1 This<br />

said, it is true that a larger share of total (international and domestic) <strong>government</strong> <strong>debt</strong> is denominated<br />

in local currency today than was the case 10 years ago. Particularly, Latin America has made progress<br />

in this regard.<br />

Some of these trends will be affected by the 2007–2009 international financial crisis, which hit most<br />

low and middle income countries in the second half of 2008. The combination of output stagnation or<br />

declines with sharp rises in deficits will lead to jumps in the ratio of <strong>debt</strong> to GDP – although less so<br />

1 They show that very few countries have been able to issue internationally in their own currency and that the<br />

participation of foreign investors in the local bond markets is still limited. They conclude that the reduction in<br />

currency mismatches and the consequent ability to conduct macroeconomic policies was due to “abstinence” (i.e.<br />

the retreat from the international bond market documented in figures 1 and 3) and not redemption. In 2001, only<br />

0.8 per cent of all bonded international <strong>debt</strong> instruments issued by developing countries were denominated in the<br />

currency of the issuing country (Eichengreen, Hausmann and Panizza, 2005). By 2008, the share of international<br />

bonded <strong>debt</strong> issued by developing countries and denominated in the currency of the issuer had increased to<br />

4.1 per cent (Hausmann and Panizza, 2010).<br />

7