THE WOUNDS OF WAR LIVING UWC AFTER UWC - UWC-USA

THE WOUNDS OF WAR LIVING UWC AFTER UWC - UWC-USA

THE WOUNDS OF WAR LIVING UWC AFTER UWC - UWC-USA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

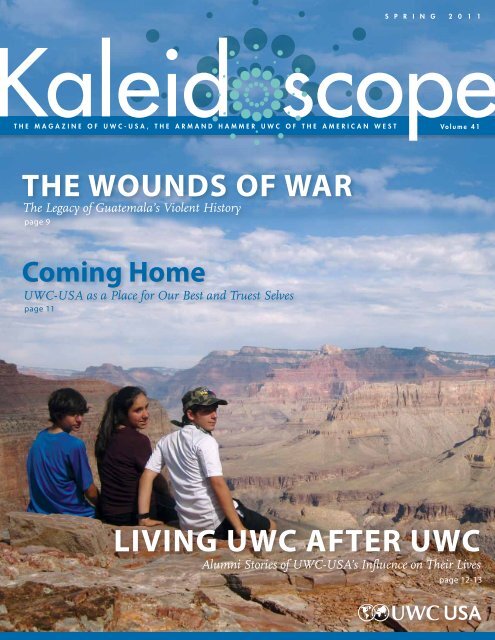

S P R I N G 2 0 1 1<br />

aleid scope<br />

<strong>THE</strong> MAGAZINE <strong>OF</strong> <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>, <strong>THE</strong> ARMAND HAMMER <strong>UWC</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> AMERICAN WEST<br />

Volume 41<br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>WOUNDS</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>WAR</strong><br />

The Legacy of Guatemala’s Violent History<br />

page 9<br />

Coming Home<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> as a Place for Our Best and Truest Selves<br />

page 11<br />

<strong>LIVING</strong> <strong>UWC</strong> <strong>AFTER</strong> <strong>UWC</strong><br />

Alumni Stories of <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>’s Influence on Their Lives<br />

page 12-13

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE:<br />

We’re almost 30! Somehow when we turned the calendar to 2011, the<br />

proximity to 2012, and the College’s 30th anniversary, became very real to<br />

me. This marker seems a good moment to update our alumni, parents,<br />

and friends on some key events in the life of our school.<br />

As I believe you all know, Peter Hamer-Hodges, who served the<br />

school from 1983 to 2010 and was our distinguished graduation speaker<br />

last May, departed for new adventures in his native UK. In many respects,<br />

he exemplifies the life of service and the commitment of many of our faculty. It is not surprising that,<br />

after long and distinguished tenures at <strong>UWC</strong>, other faculty members are also considering transitioning<br />

to new opportunities such as writing, consulting, or retirement. In recognition of their extraordinary<br />

service to students and the <strong>UWC</strong> movement, the board has created a transition fund to support longer<br />

serving faculty members as they move to the next chapters in their lives.<br />

There are cases where we will not be replacing these departing faculty members. In this era, when<br />

we are juggling the challenge of the loss of value of our endowment from its peak in 2008 and facing<br />

the anticipated loss of the Armand Hammer Trust in 2013, it is only responsible to contain costs wherever<br />

we can. Teachers who will remain on the faculty have indicated a willingness to take on additional<br />

responsibilities to make this possible. We will also seek to reduce non-teaching staff positions through<br />

attrition over time.<br />

What is important to me is that the giants who founded and shepherded this school and so many generations<br />

of students go on to their next phase in life with honor, support, and celebration. I want you to<br />

know we’re working to do exactly that. It’s also important that you know that we will be seeking to find the<br />

next generation of great faculty members who can influence lives, participate in our intensely experiential<br />

and residential program, and deliver high intellectual content in the classroom in vital and exciting ways.<br />

Know that as we do all of this, we do so with a clear eye on our mission and on the welfare of our<br />

students. Know that we are redoubling efforts, with considerable success and thanks to many of you,<br />

to raise more financial support. Know that we remain focused on everything central to our important<br />

purpose in the world.<br />

As always, please let us know if you have questions. In the meanwhile, be prepared to honor the<br />

pioneers and welcome the new adventurers.<br />

With warm best wishes from Montezuma,<br />

Lisa A. H. Darling<br />

President<br />

2<br />

CREDITS<br />

editor in chief<br />

Elizabeth Morse<br />

contributing editor<br />

Emily Withnall M<strong>UWC</strong>I ‘01<br />

designer<br />

Danielle Wollner<br />

contributors<br />

Abuubakar Ally ‘12<br />

Innocent Basso ’11<br />

Omar Yaxmehen Bello Chavolla ’11<br />

Gert Danielsen ’96<br />

Aminata Deme ’11<br />

Marie Dixon Frisch ’84<br />

Cassandra Doremus ’11<br />

Timothy J. Dougherty<br />

Rodrigo Erazo ’12<br />

Nofar Hamrany ’11<br />

Ali Jamoos ‘12<br />

Henrik Jenssen ’12<br />

Pedro Monque ’12<br />

Kevin Mazariegos Moralles ’11<br />

Natalia Bernal Restrepo ’05<br />

Julian Rios ‘12<br />

Kate Russell<br />

Jake Rutherford<br />

Arjan Stockhausen ’11<br />

Vichea Tan ’11<br />

Elizabeth Withnall<br />

Bereket Zekarias ’11<br />

contact<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong><br />

PO Box 248<br />

Montezuma, NM 87731<br />

<strong>USA</strong><br />

505-454-4200<br />

publications@uwc-usa.org<br />

Kaleidoscope is published biannually<br />

by the <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Development Office,<br />

for the purpose of keeping the extended<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> community connected.<br />

feedback<br />

Send an email to<br />

publications@uwc-usa.org,<br />

or post a comment online at<br />

www.uwc-usa.org/read.<br />

We look forward to hearing your<br />

comments and critiques!<br />

On the cover: <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> students at the<br />

Grand Canyon.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG<br />

Photo credit: Timothy J. Dougherty<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen

Photo credit: Jake Rutherford<br />

Alumni, parents, trustees, get-aways, employees, and friends have come<br />

together this year to help broaden and deepen philanthropic support for<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> and close the funding gap that the school will soon face.<br />

Led by the Annual-Fund<br />

Challenge Committee, a group<br />

of leaders who pooled funds<br />

used to match gifts from other<br />

supporters, the Challenge<br />

matches gifts from those who<br />

(1) become a Castle Club mem- Sebastien de Halleux ’96<br />

ber and (2) double their previous<br />

Annual-Fund gift.<br />

KC Kung ’87<br />

Challenge Committee members<br />

committed a combined<br />

total of $215,000 for the Challenge,<br />

and the response was<br />

strong. The Challenge was<br />

met in early February, thanks<br />

to the 132 people who made<br />

qualifying gifts.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> is very grateful Charles C. Wong ’84<br />

to the Challenge Committee<br />

Kenneth Yeung ’84<br />

SPRING 2011<br />

TABLE <strong>OF</strong> CONTENTS<br />

<strong>THE</strong> 2010-2011 ANNUAL-FUND CHALLENGE<br />

A Distinctly “HK” Alumni Event 2<br />

Opportunity 3<br />

Possession 4<br />

Backpack 5<br />

Grandmother 6<br />

A Lesson 7<br />

Writing the World 8<br />

The Wounds of War 9<br />

Music is a Conversation 10<br />

Coming Home 11<br />

Living <strong>UWC</strong> After <strong>UWC</strong> 12-13<br />

How I Became a Clown 14 -15<br />

Alumni Profiles 16 -17<br />

for inspiring scores of others to dramatically increase their support<br />

at a time when building our Annual Fund is essential to the school’s<br />

future. We are also extremely grateful for the generous donors who<br />

are stepping up to meet the<br />

Challenge. These gifts will<br />

help transition <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong><br />

to a more sustainable base<br />

of philanthropic support<br />

and strengthen the school to<br />

fulfill its mission for generations<br />

to come.<br />

If you haven’t made your<br />

Annual Fund gift yet, it’s not too<br />

late! The Annual Fund, which<br />

raises money for current-year<br />

operations, ends on May 31. Support<br />

it by making a gift online at<br />

www.uwc-usa.org/give or sending<br />

a check to <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Development<br />

Office, PO Box 248,<br />

Montezuma, NM 87731, <strong>USA</strong>.<br />

The Annual-Fund Challenge Committee<br />

Marc Blum, <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Trustee, Committee Chair<br />

Tom and Beverley McGuckin, current parents<br />

Benjamin Melkman ’98 and Alexa Melkman ’99<br />

Bill Moore, former <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Trustee and Capital Campaign Chair<br />

Michael Stern ’89, Distinguished Trustee<br />

James and Sarah Taylor, alumni parents and <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Trustees<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 1

A Distinctly “HK” Alumni Event<br />

Emily Withnall, M<strong>UWC</strong>I ’01<br />

Communications<br />

“How is <strong>UWC</strong> to remain relevant?”<br />

This was one of the many <strong>UWC</strong>-themed<br />

topics that came up during the Hong Kong<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> alumni barbeque, hosted by<br />

Charles Wong ’84 last October on Middle Island,<br />

Hong Kong.<br />

The answers to<br />

this question covered<br />

vast ground,<br />

but some of the<br />

first alumni from<br />

the 1980’s talked<br />

at length about<br />

the importance of<br />

having mainland<br />

Chinese students<br />

regularly represented<br />

at <strong>UWC</strong>-<br />

<strong>USA</strong>. While regular<br />

representation<br />

of mainland Chinese<br />

students remains<br />

a long-term<br />

ambition, they agreed that with China growing<br />

in economic importance, it will be essential to<br />

ensure this representation from China to anticipate<br />

and further support the ideals of peace,<br />

sustainability, and the bridging of cultures.<br />

Charles Wong ’84, Kenneth Yeung ’84, Annie<br />

Fung ’85, Fiona Siu ’86, and KC Kung ’87<br />

count among the senior group of Hong-Kong<br />

alumni very active in supporting and sustaining<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>, a group that has recently<br />

established the <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> Greater China<br />

2<br />

Photo courtesy of<br />

Timothy J. Dougherty<br />

While regular representation<br />

of mainland Chinese students<br />

remains a long-term ambition,<br />

they agreed that with<br />

China growing in economic<br />

importance, it will be essential<br />

to ensure this representation<br />

from China to anticipate and<br />

further support the ideals of<br />

peace, sustainability, and the<br />

bridging of cultures.<br />

Foundation to facilitate support of the school<br />

and scholarships for students attending the<br />

school. In addition, three of these graduates,<br />

Charles Wong, Kenneth Yeung, and KC Kung,<br />

have taken a leadership role in fund-raising<br />

for the school by<br />

becoming part<br />

of the Annual-<br />

Fund Challenge<br />

Committee for<br />

the 2010-11 school<br />

year. This committee,<br />

composed<br />

of alumni, parents,<br />

and friends,<br />

has pledged to<br />

match gifts to<br />

this year’s annual<br />

fund from donors<br />

who double their<br />

previous gifts and<br />

join the Castle<br />

Club. More information<br />

on the challenge can be found at<br />

www.uwc-usa.org/annualfundchallenge.<br />

This Hong Kong <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> alumni gathering<br />

was the second event Charles Wong has<br />

hosted for <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>. Charles’s dedication<br />

to <strong>UWC</strong> runs deep: “<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> was such a<br />

powerful and important part of my life that I<br />

am thrilled to be able to support the school<br />

and to help foster connections among my fellow<br />

graduates.”<br />

Charles Wong ’84 and his mother<br />

arrived in Hong Kong at the train<br />

terminal in Kowloon from mainland<br />

China when he was twelve years old.<br />

According to Charles, this was during<br />

a time when people from mainland<br />

China were seen in Hong Kong as<br />

coarse and ill-mannered. Charles was<br />

tormented in school but nevertheless<br />

excelled academically. In spite of his<br />

lack of familial connections, which<br />

were important and highly regarded<br />

in Hong Kong society, Charles was<br />

determined, against all odds, to go to<br />

the best school in Hong Kong.<br />

One day, he walked into an esteemed<br />

school and asked to see the<br />

headmaster. The headmaster happened<br />

to be standing near the receptionist,<br />

asked what he wanted, and<br />

brought him in to his office. The<br />

headmaster invited Charles to apply,<br />

and he was admitted. While he attended<br />

the school, Charles ran track,<br />

swam, and played the violin—things<br />

he still enjoys.<br />

Charles attended <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> because<br />

of the opportunity and adventure<br />

it offered. From <strong>UWC</strong>, he went<br />

to Pomona College and studied liberal<br />

arts. His first job was with General<br />

Electric. He eventually attended the<br />

Harvard’s Kennedy School, and during<br />

his summer breaks he interned for<br />

both McKinsey and Goldman Sachs.<br />

Charles left school early and started<br />

late so he could intern for eight weeks<br />

at each of these prestigious companies,<br />

and he remembers taking his<br />

end-of-year exams on an airplane and<br />

faxing them back to his professors.<br />

Charles is now CEO and Chairman<br />

of the Board at Global Flex Holdings<br />

as well as a Director of Chi Capital.<br />

Charles will be on campus in<br />

April to participate in Alumni Weekend,<br />

an annual event which brings inspiring<br />

alumni back to campus to interact<br />

with current students. He will<br />

be joined by diplomat Laura Taylor-<br />

Kale ’96, and conservationist Aurelio<br />

Ramos ’91.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

WHERE WE’RE FROM<br />

Opportunity<br />

Vichea Tan ’11<br />

Cambodia<br />

Working with AFESIP Cambodia (Acting for Women in Distressing<br />

Situations) last summer was the most wonderful experience I<br />

have ever had.<br />

People have equal rights and the same value but unfortunately<br />

some have been valued in terms of money. One of many problems<br />

we are facing in our society is human trafficking. In Cambodia,<br />

thousands of kids and women get into this problem every year.<br />

AFESIP is working very hard to<br />

rescue people who have been<br />

traded. Many of them are still<br />

young and have seriously suffered,<br />

which makes it very hard<br />

to go back and face the realities<br />

of our society.<br />

I spent five days working<br />

in the AFESIP center. We were not allowed to stay overnight<br />

because we were not familiar to the girls in the center. The first<br />

time I entered the center I felt we were feared, and I saw that<br />

there were some people who were trying to stay apart from our<br />

group. We tried to make ourselves familiar so that we could work<br />

with them well. We played some games, had a discussion about<br />

food, and created a music lesson. After a few days of effort I could<br />

feel the improvement by the way they interacted with us. Smiling<br />

I used to think that I had very little<br />

opportunity in my tiny world, but after I<br />

met these people, I knew I had been wrong.<br />

as they always do, they started to talk and were passionate in doing<br />

the activities.<br />

As it went on I started to learn about a 14-year-old girl who was rescued<br />

a few months before we went to the center. I was showing the girl how<br />

to play guitar and having conversation with her. While we were talking, I<br />

asked her where she came from. She suddenly turned quiet, bending her<br />

face down. I felt bad because I knew that I had done something wrong. At<br />

the end of the day, before we left the<br />

center, the girl came to me and gave<br />

me a piece of paper. She told me in<br />

the paper that she was also from the<br />

place where I came from. She has<br />

six younger brothers and sisters,<br />

but her mother died four years ago.<br />

She had been sold to be a prostitute<br />

before she was rescued and sent to the AFESIP center. “I am so glad that<br />

you all came and taught us a lot of things which make me really happy,”<br />

she wrote, “and I really hope I will have another chance to learn how to<br />

play guitar.” I was so touched by the letter.<br />

I used to think that I had very little opportunity in my tiny world,<br />

but after I met these people, I knew I had been wrong. After five days of<br />

working in the center, we learned a lot from each other. I left Siem Riep<br />

and returned home. I hoped that we made good memories for those girls.<br />

Photo courtesy of Vichea Tan<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 3

WHERE WE’RE FROM<br />

Julian Rios ’12<br />

Colombia<br />

Inspired by “Theme for English B,”<br />

by Langston Hughes<br />

FROM <strong>THE</strong> DEEP BOWELS <strong>OF</strong><br />

<strong>THE</strong> ROCK,<br />

From the sacred heart of the mountain,<br />

And from the wild arms of the<br />

torrential river,<br />

A voice like a sorrow is rising up to me.<br />

With the blood of my people in his hands<br />

And the burden of our eternal struggle<br />

in his shoulders<br />

My father Wiracocha through the wind<br />

my name is calling.<br />

My name and all the names,<br />

My name and the names of my brothers<br />

who died,<br />

My name that is the rose of my pacha.<br />

Although, I was born in a Spanish cradle,<br />

In my blood indigenous strength flows.<br />

The breath of my grandparents my<br />

secret embraces<br />

As one day from Mother Bachue a<br />

muisca people was born.<br />

4<br />

Possession<br />

Aminata Deme ’11<br />

Senegal<br />

Sometimes we can be blinded by a strong<br />

and irrefutable sense of belonging to and<br />

possessing our culture. Not only do we tend<br />

to defend our culture, but we also love to<br />

think of it or look at it as the most perfect,<br />

the most authentic.<br />

I believe there are times when we need to<br />

challenge our convictions about our own cultures,<br />

to accept and be open to the changes that<br />

might benefit our societies.<br />

Where I come from, some women are<br />

still oppressed for the sake of culture and<br />

tradition. I often think,<br />

“I could be one of those<br />

young women.” I am terrified<br />

by that thought.<br />

So much I would suffer,<br />

prisoner of a society<br />

with no mercy.<br />

As a woman in that<br />

culture, I would never<br />

dare claim my rights in<br />

my society. By the age of<br />

sixteen, I would already<br />

have been married by<br />

force to a fifty-year-old<br />

stranger. I would have<br />

no say. As a woman, my<br />

opinions would be neither<br />

heard nor valued, my<br />

choices would not be considered,<br />

and no escape<br />

would be possible. My<br />

life would be reduced to<br />

bearing children with no<br />

strength, feeding a family<br />

with no joy, forever being<br />

the subaltern in a society<br />

governed by men’s power.<br />

How excruciating can<br />

it be to undergo all this<br />

misery, having society<br />

trivialize it, with no ability<br />

to act upon it? The traditions<br />

and the community<br />

make it impossible for<br />

women to break free from<br />

forced marriages. Mothers<br />

and sisters can’t even help;<br />

they do not get involved in<br />

these decisions because<br />

they are women. Even women who have experienced<br />

similar situations often become so brainwashed<br />

that when their daughters and sisters<br />

suffer, and hope to be rescued, they lecture them<br />

about being better wives. How paradoxical!<br />

For so long, we have paid respect to ancient<br />

traditions that have ignored the rights of youth<br />

and children and oppress women in the grossest<br />

and most outrageous forms.<br />

It’s now the time to abolish all restrictive<br />

and backward cultural practices that hinder<br />

women’s and youth’s free will.<br />

Where I come from, some women are<br />

still oppressed for the sake of culture and<br />

tradition. I often think, “I could be one of<br />

those young women.” I am terrified by<br />

that thought.<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

Backpack<br />

Nofar Hamrany ’11<br />

Israel<br />

It was August 2003, the end of summer break. I actually wanted it<br />

to end. I was so excited to go and buy a new backpack, notebooks, colorful<br />

pens, and all the other school supplies that I needed. My mom took<br />

me to the shopping center in our town. The minute I got to the store I<br />

started looking at all the<br />

backpacks, trying on each<br />

that we were breathing. I just looked at the school supply store. The<br />

doors were broken, and all the backpacks had turned black. I couldn’t<br />

believe that I was standing there yesterday trying them on. That night<br />

on the news, they announced that twenty-nine people had been injured<br />

and two people had<br />

been killed.<br />

In the background I could see the paramedics and<br />

dozens of people crying and bleeding. And I knew all<br />

of them; they were all from my town.<br />

one of them. My mom<br />

told me to choose quickly,<br />

but I didn’t listen.<br />

After two hours, we<br />

went back home, and<br />

I ran to my room and<br />

started to put my notebooks in my new bag. My mom said I needed to<br />

sleep because it was late. I went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep. I stayed<br />

up all night thinking about school and being able to see my friends.<br />

The next morning I woke up and wanted to visit<br />

my friend. I called my mom at work to ask her. She<br />

sounded angry, and she told me not to leave the<br />

house. I asked her, “What’s wrong?” She didn’t answer<br />

but just kept saying, “Do not leave the house.”<br />

I was mad because I couldn’t visit my friend, and I<br />

was embarrassed to call her and tell her that I couldn’t<br />

come. I finally dialed the number, and she answered<br />

so fast that I didn’t even have the time to speak; she<br />

was already asking, “Are you OK? Where are you?”<br />

I said, “I’m in my house.”<br />

“Where are your parents?”<br />

“My mom is at work and I don’t know where my<br />

dad is. Why?”<br />

“You didn’t hear it?”<br />

I still didn’t know what she was talking about,<br />

but I understood that something bad had happened.<br />

She started to tell me that she heard a big “boom” an<br />

hour ago. She looked out her window, and she saw<br />

fire and a lot of smoke. There was a suicide-bomber<br />

attack in the shopping center in our town.<br />

I couldn’t believe it. I switched on the TV and saw<br />

it all over the news. I called my dad to make sure<br />

that he was ok, and then I started to call all the people<br />

I knew. When I finished calling all my friends<br />

and family to make sure that they were ok, I started<br />

watching the news. There were interviews of people<br />

who were there when it happened, and I recognized<br />

all of them. In the background I could see the paramedics<br />

and dozens of people crying and bleeding.<br />

And I knew all of them; they were all from my town.<br />

When my mom came back from work, we went<br />

to my aunt’s house. We drove past the shopping center,<br />

or rather what was left of it. The skies where still<br />

black from all the smoke, and the smell was still in<br />

the air. The smoky smell of fear blended in the air<br />

A few days after that,<br />

school started. I went<br />

on the first day with my<br />

new backpack, expecting<br />

everything to be normal<br />

again, but it wasn’t. For<br />

the first week we just talked about the terrorist attack and how it affected<br />

us. I was very excited to go to school, but after this attack I didn’t want to<br />

talk about it. I just wanted to forget it happened, but I couldn’t. I still can’t.<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 5

WHERE WE’RE FROM<br />

Grandmother<br />

Bereket Zekarias ’11<br />

Ethiopia<br />

She said she had lost eight of her children, was beaten by her husband<br />

every day, and had suffered most of her life. When she told me these<br />

things, all I could utter was, “Everything is for a reason,” but deep inside<br />

I inquired, “Why? Why does she have to<br />

go through all this injustice?”<br />

I call her Abeye; she is my grandmother,<br />

my guardian, and my second<br />

mom.<br />

“Don’t associate with boys; they are<br />

evil. Promise me to keep yourself away<br />

from them while you are in school.”<br />

I guess she doesn’t want me to go<br />

through the suffering she was forced<br />

to bear.<br />

“Getachew, Kebede, Belay, Ayele,<br />

Zenebe, Neway, Abebe, Zelalem. I got used to letting them go. Every time<br />

I got pregnant, I knew deep inside of me that I had to let go a person<br />

inside my womb. Your grandfather was no help; he said I had a curse<br />

which was responsible for the death of all of his children, but I never got<br />

the courage to tell him that they were my children too and that I carried<br />

them inside my womb for nine months anticipating seeing them alive.<br />

Your grandfather even brought his child from another woman and told<br />

me to raise the baby. I raised the baby like it was mine, first because I<br />

didn’t have a choice, and second because I needed a baby that was mine.”<br />

6<br />

She took a deep breath as if to let all the lamentation out. Her eyes<br />

are small, so very small that it’s amazing that she can see. I deduced<br />

that the smallness of her eyes came from crying all the time, or from<br />

When I feel depressed because I didn’t do well on a chemistry test<br />

or I didn’t do a good job on my class presentation, I immediately<br />

remember that I am an Ethiopian woman. What Ethiopian women<br />

do best is beat all the odds in life. To fight for better treatment<br />

and to fight for a happier and more fulfilled life is the battle of<br />

Ethiopian women every day.<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

the sunshine that was hidden from her while the whole world had the<br />

chance to see the sun.<br />

“God is good; he gave me your mother. I didn’t even name her<br />

because I didn’t want to be cheated again. When your mother was<br />

three months old, I went to church and begged God to make her live,<br />

and it worked.”<br />

She stopped to wipe away the tears that were rolling down her cheeks.<br />

She kissed the ground and said, “Thank you God for giving me an opportunity<br />

to have grandchildren. I can die now.”<br />

That was one of the saddest moments of my life, not only because I<br />

knew that my grandmother’s life was full of challenges but also because<br />

it took me forever to realize what she went through to protect me. Her<br />

gratitude struck me like a lightning bolt, because she is a woman who<br />

keeps thanking God though she has little reason to do so.<br />

When I asked what the happiest moment in her life was, she looked<br />

me in the eyes and said, “I have had a lot of happy moments, dear; we are<br />

responsible for creating our happy moments. Though my life was hard, I<br />

have had magnificent moments that make my life worth living. The nine<br />

times I gave birth to my children and when I saw their closed eyes and<br />

heard their crying for the first time, I thanked God because he gave me<br />

the opportunity to see these wonderful beings. The day you were born<br />

was also one of the happiest moments of my life. Promise me that you<br />

will study hard, promise me not to let others control you and take your<br />

rights from you.”<br />

I nodded, thinking “How does she do it? How can you be optimistic<br />

when life treats you so badly?” In the end I comprehended that my grandmother<br />

is one of a kind to hold this quality.<br />

My grandmother and all women in Ethiopia keep me going every<br />

day. When I feel depressed because I didn’t do well on a chemistry test<br />

or I didn’t do a good job on my class presentation, I immediately remember<br />

that I am an Ethiopian woman. What Ethiopian women do<br />

best is beat all the odds in life. To fight for better treatment and to fight<br />

for a happier and more fulfilled life is the battle of Ethiopian women<br />

every day. Luckily I don’t fight the same fight; I fight easy things. Maybe<br />

I can fight the battle for the ones who are too tired to do so.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

A Lesson<br />

Innocent Basso ’11<br />

Tanzania<br />

I grew up in a very strict Christian family. I was expected to do exactly<br />

as I was instructed without questioning. Failure to comply with<br />

these principles resulted in severe punishment from my parents. It is<br />

for this reason that I developed strong abidance to certain precepts in<br />

life. In addition, I always wanted to lead most of the activities I was involved<br />

in because I could not afford to see something done differently.<br />

Despite my strong attachment to the teachings of my parents, at<br />

one point I had to deviate from the set of formula and actually do what I<br />

personally thought was right. In my third year in<br />

a seminary, back home in Tanzania, I was elected<br />

the General Secretary of the Students’ Council.<br />

My job was to organize and coordinate different<br />

activities on campus. In one particular case, my<br />

classmates agreed not to do a job they were assigned.<br />

Considering the essential nature of the<br />

job, I informed the school administration about<br />

the situation, asking for assistance to make them<br />

do it. My action offended my classmates, and it<br />

was taken as an act of betrayal. Although I tried<br />

to explain myself, they ignored me and decided to<br />

teach me a lesson.<br />

My classmates excluded me from all class<br />

matters, and nobody was allowed to talk to me.<br />

Offensive comments against me were spread all<br />

over campus. I tried to ignore them, but the situation<br />

got worse. Some of them began to insult<br />

me verbally, and my personal belongings were<br />

vandalized.<br />

As the General Secretary, I could report them<br />

to the seminary’s administration. According to<br />

principles I grew up with, this is what was right<br />

to do. Nevertheless, this option would unnecessarily<br />

harm the student community because<br />

it would result in the expulsion of many of the<br />

students–even innocent ones. I believed that as<br />

a leader my primary goal was to assure a fruitful<br />

and enjoyable school experience for everyone;<br />

therefore, reporting them was not an option. I<br />

understood that anger was in control of my classmates.<br />

It was difficult for them to accept that I<br />

could “betray” my class and get away with it.<br />

During this time, the whole student community<br />

was watching me, waiting to see how<br />

I was going to handle the situation. I was confused.<br />

I did not like all the harassment I was<br />

subjected to, but all the same, I was not ready<br />

to lose members of our community. Luckily,<br />

an alumnus visited the seminary, and I did not<br />

hesitate to share my problems. He promised me<br />

that he would help. He talked to my classmates<br />

in a meeting that he did not let me attend, and successfully convinced<br />

them to retreat from their mission.<br />

I have become more flexible. I now know that there is always another<br />

way to do something. I learned about my weaknesses, and I have<br />

been made stronger. I appreciate the adventures that life has to give<br />

because they broaden my perception and make me a better person. I<br />

believe that what I learn from my experiences now are the tools for<br />

overcoming greater challenges in the future.<br />

I have become more flexible. I now know that there is<br />

always another way to do something. I learned about my<br />

weaknesses, and I have been made stronger.<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 7

WHERE WE’RE FROM<br />

Rodrigo Erazo ’12<br />

Ecuador<br />

Inspired by “Theme for English B,”<br />

by Langston Hughes<br />

“It’s going to be better.”<br />

I guess not…<br />

As I wake up at 4 am in “my” bed that I<br />

share with my 8 siblings<br />

As I take a shower with cold water, not<br />

really in a shower, but with a bowl from<br />

the kitchen<br />

As I put on the same clothes that I wear<br />

every day<br />

As I go to the kitchen just to realize there’s<br />

nothing to eat…<br />

I walk out of there to find a job, to bring<br />

something to eat to my home<br />

At least a couple of dollars in my pocket to<br />

buy some bread for my family<br />

nothing…<br />

Failure followed by failure… I’m tired of<br />

trying the same everyday<br />

I’m tired of watching my brothers going<br />

to bed with hunger<br />

I’m tired of watching my mother dealing<br />

with my drunken father<br />

I’m tired of being useless…<br />

My father is no longer<br />

At least my mother will wake up without<br />

bruises on her face<br />

And now off to the city, to find a<br />

better life<br />

I’ve been crying since my father died; even<br />

though he beat my mother<br />

I loved him…<br />

I’m reading what I wrote<br />

And I have a simple question:<br />

Is it going to be better?<br />

8<br />

Writing the World<br />

Omar Yaxmehen Bello Chavolla ’11<br />

Mexico<br />

Storms and earthquakes, special dishes<br />

and exotic flavors, the warmth of the sand and<br />

the cruel coldness of the hard rocks. Those<br />

were some of the images that vibrated in every<br />

surface of the dining room every night as my<br />

parents told me countless stories about things<br />

I never heard before. These and more of their<br />

words kept resonating in my head while I slowly<br />

returned to reality. I<br />

found myself staring<br />

at a blank piece<br />

of paper in front<br />

of me, a pen in my<br />

hand.<br />

These stories<br />

came to life for me<br />

in a way that was as<br />

real as the words I<br />

am writing. I write to live the unthinkable, to<br />

teleport myself to the endless scenarios the<br />

mind creates. I write because it keeps me alive,<br />

makes me feel that the world can be sketched<br />

beyond what can be seen with a simple glance.<br />

Ideas turned into motion, motion turned<br />

into ink, ink into capricious swirls that sank in<br />

the fibers of a corroded paper. The idea became<br />

the word, the word became the story. All those<br />

stories that were bound to be told resonated as<br />

echoes in my head; as the words flowed slowly<br />

throughout the years, the pile of paper next to<br />

my bed kept growing. I soon realized that the<br />

q Omar with co-year Ivana Marincic.<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

Storytelling was the way I<br />

found myself living in the<br />

1960s in that terrible storm<br />

that my father used to recall<br />

with angst…<br />

stories were for me more than a hobby; they<br />

were a lifestyle. I turned myself into a character<br />

and lived my life as a story that I tried to tell<br />

myself every day.<br />

Storytelling was the way I found myself<br />

living in the 1960s in that terrible storm that<br />

my father used to recall with angst, and the<br />

way I felt inside a building in inner Mexico<br />

City after the 1985<br />

earthquake in September,<br />

when my<br />

mother was helping<br />

to coordinate<br />

phone calls for the<br />

only telephones<br />

that were available<br />

near the disaster<br />

zone. It is amusing<br />

to look back on those stories about elves that<br />

my father used to tell me, remembering how<br />

they became for me as tangible as any other<br />

thing in this world. I soon realized that I wrote<br />

because I wanted the world to make sense, because<br />

words were the only way I could make<br />

the world real.<br />

And I am still sitting in front of a blank paper<br />

while thinking of all the stories that could<br />

possibly be written. Every bit I write makes me<br />

feel that the world makes more sense to me.<br />

Will it ever be completely clear? I hope not. I<br />

want to keep trying to figure it out.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

The Wounds of War<br />

Kevin Mazariegos Moralles ’11<br />

Guatemala<br />

I was born at the end of Guatemala’s civil war. My family suffered<br />

the cruelties of war for a long time. I was lucky to be just six-years-old<br />

when the Civil War ended.<br />

After a war, a country is never the same. Many things change. The<br />

people’s minds are full of fear and pain. The wounds of my nation are<br />

just starting to heal.<br />

My story is about living in Guatemala. Guatemala is a third-world<br />

country with one of the highest indexes of violence in the world.<br />

I remember the<br />

first time I was ever<br />

robbed. I was 14 years<br />

old. It was on a Saturday<br />

morning, and<br />

I was walking from<br />

my mom’s coffee<br />

shop toward my best<br />

friend’s house. Like<br />

every Saturday morning,<br />

the streets were<br />

crowded with people.<br />

I was passing though<br />

a parking lot when a<br />

little boy around 10<br />

years old came to me<br />

and asked for money.<br />

That day I was carrying<br />

a lot of money<br />

with me, but I didn’t<br />

give any to him. Suddenly<br />

he put his hand<br />

on his pocket at the<br />

same time he told me<br />

it was not a question.<br />

I was really lucky that<br />

the boy was afraid of<br />

me that time.<br />

Drug Trafficking is<br />

one of the major problems<br />

in Guatemala. I<br />

remember traveling<br />

with my mother and<br />

sister to a little village<br />

where my mom had a<br />

small business. It was<br />

noon, and we were<br />

going through a dirt<br />

track off the principal<br />

avenue. Suddenly one<br />

guy came out from a<br />

house just to the right<br />

of us. To our left there was a little workshop, and two guys were standing<br />

by a car. In just a second, the three of them pulled their guns out,<br />

and, like in the movies, my mom turned almost immediately around.<br />

She was nervous and really afraid. We left as quickly as possible. We<br />

heard the shots in the distance.<br />

They tell me the war is over. I don’t believe them. Each day people<br />

get massacred by violence. People live with fear. You turn, and something<br />

is happening. There is no way to escape. I live with fear.<br />

They tell me the war is over. I don’t believe them. Each day people get<br />

massacred by violence. People live with fear. You turn, and something is<br />

happening. There is no way to escape. I live with fear.<br />

q Chichicastenago, Guatemala, 1992. During the Guatemalan civil war, indigenous women sought out American clothing to avoid being<br />

identified and targeted.<br />

Photo credit: Elizabeth Withnall<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 9

WHO WE ARE BECOMING<br />

Music is a Conversation<br />

Pedro Monque ’12<br />

Venezuela<br />

One of the first things Markus Stockhausen said to my friends<br />

and me during our preparation to perform with him in concert was<br />

about expanding our window of musical appreciation. Markus is a<br />

renowned German musician with abilities in composing, directing,<br />

improvising, and performing trumpet solos. He initially came to<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> with the purpose of visiting his son Arjan, but in staying<br />

here for a week as an artist-in-residence, he profoundly changed many<br />

people in the school.<br />

Our music teacher Ron Maltais arranged a concert and practiced<br />

with all students interested in learning intuitive music with Markus.<br />

Intuitive music, as Markus likes to call it, is basically music improvisation—but<br />

with a special approach. I practiced for the concert with<br />

ten friends, plus Ron. The time we spent with Markus learning how<br />

to intuit music was both amazing and hard. In order to do a good job,<br />

there was a high amount of concentration, energy, and creativity needed.<br />

“Listen to the others all the time” and “Music is a conversation, and<br />

you should only talk when you have something to say” were some of the<br />

phrases Markus repeated often. One of the hardest parts for me was to<br />

start playing in an atonal way (not in any particular key). I think that we<br />

all felt that something wasn’t right the first time we did it.<br />

The week went fast. We were practicing a lot, developing new skills,<br />

and suddenly it was the concert day. The anxiety rose every second, but<br />

q Markus Stockhausen performing with <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> students.<br />

10<br />

Markus Stockhausen studied initially at the Cologne<br />

Musikhochschule and is as much at home in jazz as<br />

in contemporary and classical music. For about 25<br />

years, Markus collaborated closely with his father,<br />

the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. Markus’s son,<br />

Arjan, is a second-year student at <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.<br />

Markus kept himself very calm and confident. The whole point of intuitive<br />

music is to play what we feel in the moment and to make a musical<br />

conversation out of it. There were no scores, just instruments and<br />

enthusiasm. Before going on stage, we all meditated in a circle and tried<br />

to connect. It worked.<br />

The audience was waiting. We sat and started playing, trying to feel<br />

the music from inside. For two periods of 15 minutes each we played.<br />

The ending of the second period was very special because we were actually<br />

feeling each other’s music.<br />

At the end of our last improvisation, people started to clap intensely<br />

as we left the stage, and we experienced an adrenaline<br />

rush. It was hard to believe that we had reached that special state<br />

of symbiosis. Afterwards,<br />

Markus played with Kevin<br />

Zoernig, a jazz pianist, and<br />

Ralph Marquez, a drummer.<br />

The trio played some<br />

of Markus’s compositions.<br />

It was stunning. The last<br />

two pieces were played with<br />

Amir Shemesh ’11, Israel,<br />

who also added his great talent<br />

to the trio with a saxophone<br />

performance.<br />

Then the time was<br />

Photo credit: Arjan Stockhausen<br />

over. We all said goodbye to<br />

Markus. I felt proud of what<br />

we accomplished, but overall<br />

I felt immensely grateful for<br />

the experience of working<br />

with Markus, one of the best<br />

musicians I have ever met.<br />

I wouldn’t have had this opportunity<br />

anywhere else, and<br />

that week changed not only<br />

my musical perception, but<br />

everyone who was involved<br />

in this experience. We will<br />

never forget the time we<br />

shared with Markus Stockhausen<br />

and with each other.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

Coming Home<br />

Cassandra Doremus ’11<br />

<strong>USA</strong>-Nebraska<br />

Grit burns my eyes and dust coats my mouth. I am tired—no, I am<br />

exhausted. I am exhausted beyond any point I have ever reached in my<br />

eighteen years on this planet. I have spent the last fifteen hours on a<br />

bus, and all I want is sleep.<br />

It is pitch dark outside, and as we round that final<br />

bend, Montezuma Castle looms overhead, glowing<br />

in the night. Suddenly, we are all cheering. It has<br />

only been five days, and yet it has been a lifetime.<br />

In the last five days, I have seen both the best and the worst of humanity.<br />

I have seen small children running in the streets toward homes<br />

made of aluminum. I have seen a handful<br />

of men wander through the desert<br />

picking up the garbage left by desperate<br />

men and women in a race to find a<br />

means of survival. I have seen people<br />

meant to represent justice insult these<br />

same men and women. I have spent<br />

the last five days in Agua Prieta, Sonora,<br />

Mexico.<br />

I am on a bus with fourteen other<br />

people. Together, we have witnessed<br />

so much. I feel close to these students,<br />

though I hardly knew any of them a<br />

week ago. We represent twelve different<br />

countries across five continents.<br />

Each one of us is an individual—completely<br />

unique and different from every<br />

other. And yet, here we sit, waiting intently<br />

for the same thing: to round one<br />

more bend and see our home.<br />

The bus is somehow cold and stuffy<br />

at the same time. We’ve all been breathing<br />

each other’s air and smelling each<br />

other’s sweat for far too long. I, personally,<br />

have had a headache since we<br />

passed through Hatch, New Mexico—<br />

about five hours ago. My seat-mate has<br />

just woken up from his fourth nap of<br />

the day. His eyes are red from the strain<br />

of sleeping on a bus, and he’s continually<br />

rolling his shoulders to relieve the<br />

I-sat-in-a-strange-position-for-threehours<br />

neck cramp.<br />

It is pitch dark outside, and as we<br />

Photo credit: Kate Russell<br />

round that final bend, Montezuma<br />

Castle looms overhead, glowing in the night. Suddenly, we are all<br />

cheering. It has only been five days, and yet it has been a lifetime.<br />

We’ve been so far away from this place, and we’ve seen things I don’t<br />

think any of us were ready to see. We’ve only lived at <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> for<br />

two months but it is home now. <strong>UWC</strong>—it’s a place where<br />

two hundred students from every background imaginable<br />

have come together and formed something incredible.<br />

No matter where I come from, and no matter where<br />

I go from now on, I will always remember this moment.<br />

I will remember the luminous windows of the castle, the<br />

cheers of my peers, and the rumble of the bus as it makes<br />

its way up the hill. I know that I am a part of something<br />

bigger than myself here. No matter how much I struggle at<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>, I am surrounded by beautiful individuals, each with<br />

the potential to change the world. I will always remember this sensation,<br />

this feeling of coming home.<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 11

<strong>LIVING</strong> <strong>UWC</strong> <strong>AFTER</strong> <strong>UWC</strong><br />

Returning Home to Find My Path in Education<br />

Natalia Bernal Restrepo ’05<br />

Colombia<br />

When trying to describe my life after <strong>UWC</strong>,<br />

I immediately realize that there is definitely a<br />

before and an after. Before I was accepted to<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>, I always thought I would become a successful<br />

lawyer, or perhaps a doctor. But then<br />

my life was turned upside down. <strong>UWC</strong> challenged<br />

everything I believed in, and questioned<br />

all the choices I had made in my life, and the<br />

choices I thought about making.<br />

Photo courtesy of Natalia Restrepo<br />

p Natalia Bernal Restrepo<br />

I made a choice not very common among<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>ers. While all my <strong>UWC</strong> friends were applying<br />

for colleges, taking SATs, and writing<br />

admissions essays, I was booking my ticket<br />

home. At home, I enrolled in a Colombian university<br />

and started my studies in law school.<br />

But something just didn’t fit. I was away from<br />

my <strong>UWC</strong> community and felt as if I were living<br />

someone else’s life.<br />

I changed my career path and got my bachelors<br />

degree in Political Science at Universidad<br />

de los Andes. Still, I found very few challenges<br />

in that career, and the classes were not the same<br />

as the ones I had received at <strong>UWC</strong>. There was<br />

a void in my life which no class was able to fill.<br />

Upon graduation I thought I was headed for<br />

an NGO or an International Organization, so I<br />

started to seek my path there. I had remained<br />

very involved with <strong>UWC</strong> by working as Vice<br />

Chair for my national committee, but in living<br />

12<br />

away from the <strong>UWC</strong> environment it was hard<br />

to pinpoint what I missed about that part of my<br />

life. I had to return to my <strong>UWC</strong> experience to<br />

find guidance.<br />

I remembered my Satur-<br />

day afternoons at the Santa<br />

Fe’s Children Museum, tutoring<br />

some of the small children<br />

on campus, and helping<br />

my classmates<br />

with French, but<br />

most of all I remembered<br />

the<br />

huge respect and<br />

love I had for my<br />

teachers at <strong>UWC</strong>.<br />

Hence, I decided<br />

to pursue a path<br />

in education,<br />

thinking that<br />

perhaps I could<br />

make students<br />

feel the way my teachers made<br />

me feel at <strong>UWC</strong>.<br />

I began teaching as an intern<br />

at Colegio Santa María in Bogotá—the<br />

school I went to before<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>. I taught Social Studies<br />

to middle-school girls, and in<br />

two days I realized that this was<br />

what I wanted to<br />

do with my life. Children and<br />

teenagers need people who<br />

will guide them and who want<br />

to teach and bring out the best<br />

in them in the classroom environment.<br />

I fell in love with<br />

being in the classroom and<br />

having 30 girls in front of<br />

me, with reading their exam<br />

responses, and having them<br />

enjoy history and question<br />

their reality.<br />

I am now getting my<br />

masters in education and will<br />

hopefully continue to teach<br />

at my school. Maybe I will<br />

even work at a <strong>UWC</strong> at some<br />

point. But for now, I just want<br />

to bring to my classroom the<br />

cultural understanding and<br />

awareness that I got in the classes in New<br />

Mexico: the excellent writing skills provided<br />

by English teacher Anne Farrell, the fun I<br />

When trying to describe my life after<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>, I immediately realize that there<br />

is definitely a before and an after.<br />

Before I was accepted to <strong>UWC</strong>, I always<br />

thought I would become a successful<br />

lawyer, or perhaps a doctor. But then<br />

my life was turned upside down. <strong>UWC</strong><br />

challenged everything I believed in,<br />

and questioned all the choices I had<br />

made in my life, and the choices I<br />

thought about making.<br />

q Gert Danielsen<br />

had with French teacher Julie Ham, the great<br />

discussions with Spanish teacher Tom Curtis,<br />

the patience and understanding taught by<br />

Math teacher Shirleen Lanham, the learning<br />

by doing with Biology teacher Fernando Mejia,<br />

and most of all, the love and caring for all<br />

my students that I learned from Economics<br />

teacher Ravi Parashar.<br />

Photo courtesy of Gert Danielsen<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

True Colors<br />

Gert Danielsen ’96<br />

Norway<br />

When I left <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>, I wanted to work<br />

for the UN. Having arrived in New Mexico<br />

with a plan to study medicine, the microworld<br />

unfolding in Montezuma changed all<br />

that. Naively, I asked my adviser Anne Farrell<br />

to write me a reference for a job with the<br />

UN. Anne knew this would be impossible for<br />

an 18-year-old with no university studies, but<br />

she also knew the importance of encouragement.<br />

So she<br />

wrote the ref-<br />

erence, saying<br />

that I “would<br />

be an asset<br />

to the UN, if<br />

not now, then<br />

immediately<br />

after university.” Anne believed in me. I have<br />

now been with the UN for four years, and I<br />

am convinced it wouldn’t have happened<br />

without <strong>UWC</strong>.<br />

My career change from medicine to international<br />

relations is merely symbolic of what<br />

<strong>UWC</strong> did for me. <strong>UWC</strong> was all about finding<br />

myself, finding an environment which<br />

was inductive to a stronger identity. If you<br />

have been in a room of red and orange for a<br />

lifetime, how do you know that your passion<br />

really is blue, green, or yellow—colors you’ve<br />

never seen or you’ve been told do not exist?<br />

<strong>UWC</strong> does that to<br />

us—it exposes us<br />

to the colors out<br />

there, and we learn<br />

which ones we enjoy<br />

and which ones<br />

we don’t, which colors<br />

we feel are “us”<br />

and which ones<br />

are definitely not.<br />

I became a Latin<br />

America fan and a<br />

Spanish-speaker,<br />

a conflict resolution<br />

enthusiast, an<br />

environmentalist,<br />

a vegetarian, an<br />

openly gay man, a<br />

volunteer, and a relativist,<br />

embracing<br />

the diversity of our<br />

amazing world and respecting everything I<br />

didn’t like. In a room full of colors, it is easier<br />

to be different. No one really notices much:<br />

you become “normal,” common.<br />

Graduating in 1996, smitten by Aleyda<br />

McKiernan’s Spanish classes, the merengue<br />

show we did on Latin American and Caribbean<br />

Cultural Day, and my new Latino friends,<br />

I went home and literally looked up “Latin<br />

I have now been with the UN for four years,<br />

and I am convinced it wouldn’t have happened<br />

without <strong>UWC</strong>.<br />

America” in the pink pages of the phone book.<br />

A couple of months later I found myself in the<br />

Guatemalan forests working with the Norwegian<br />

NGO “Latin America Groups.” I studied<br />

International Relations and Spanish and volunteered<br />

in a conflict management program<br />

in Colombia. I taught Latin American dance<br />

and engaged in student councils and NGOs<br />

which promoted peace, social justice, human<br />

rights, and environmental consciousness. I<br />

worked with the Norwegian Peace Corps in<br />

South Africa, did my MA in International<br />

Relations and Conflict Resolution through<br />

a Rotary World Peace Fellowship in Buenos<br />

Aires, and conducted Empathy and Nonviolent<br />

Communication workshops. In 2006 I<br />

worked on the Norwegian Millennium Development<br />

Goals Campaign before—I guess<br />

I can say finally—I started working with the<br />

UN in South Africa, 10 years after Anne had<br />

written me that reference.<br />

As we speak, I am starting a new job with<br />

the UN in Yemen, where I will be working<br />

on democratic governance, human rights<br />

and gender equality. Studying Arabic and extremely<br />

sensitive to the cultural shifts I will<br />

be experiencing there, I am calm and feel<br />

prepared. <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> helped me adapt to, respect,<br />

learn from, and enjoy our diverse and<br />

fascinating world. I still carry many Norwegian<br />

colors—ethnically, socially, culturally,<br />

and politically. But like all of you, I am now so<br />

much more. <strong>UWC</strong> helped me bring out the<br />

true colors of my life.<br />

Ali Jamoos ‘12<br />

Palestine<br />

Inspired by “Theme for English B,”<br />

Langston Hughes<br />

I’m seventeen.<br />

Too young, some might say,<br />

But the truth: what I have seen<br />

Is more than most people have seen in a<br />

life time.<br />

What kind of human are you?<br />

You may ask.<br />

To tell the truth, nothing but the truth,<br />

I’m like any other Palestinian.<br />

We’re old men since the minute we<br />

are born.<br />

We have suffered, and gone through<br />

catastrophes<br />

Normal people won’t even dare to<br />

dream of.<br />

Like what? You may wonder.<br />

A life of a thirteen-year-old child in my<br />

country shall be the answer.<br />

Getting arrested when you are only 13,<br />

Thrown in a small dark cell for 5 days.<br />

For what?<br />

For throwing a stone at the occupant who<br />

violated the rights of his city,<br />

He was prohibited to see sun light for<br />

three months,<br />

To play with his friends, whom he<br />

misses, but nothing can be done.<br />

And now, do you still think that I’m<br />

too young?<br />

If you do,<br />

How about the little kid who has been<br />

through all that?<br />

What do you have to say to him?<br />

Tell me, because I can’t think of anything<br />

fair to say to him.<br />

Tell me, because I don’t know.<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 13

<strong>LIVING</strong> <strong>UWC</strong> <strong>AFTER</strong> <strong>UWC</strong><br />

How I Became A Clown<br />

Marie Dixon Frisch ’84, Jamaica<br />

Edited by Emily Withnall, Communications Coordinator<br />

I was born one.<br />

Folks think clowns are for kids, but I swear, adults need them a lot<br />

more. All my heroes and role models have been murdered or assassinated:<br />

Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Kennedy, and Lincoln. They<br />

stood up for the kind of change I want to achieve, and they died for it. I<br />

don’t particularly want to die yet. I have developed a way of working that’s<br />

less confrontational. I tickle and hint instead of blaring the truth out loud.<br />

In my youth, I was very straight-laced and proper. I always wanted<br />

things to work properly, and I hated lackluster performance. I was also<br />

not very tolerant of failure; it incited and challenged me to do better. Mostly,<br />

I minded my own business. But there came times when I couldn’t<br />

tolerate some situations, and I took action.<br />

Later, I hated the way people divided the world into developed and<br />

developing countries. Aren’t we all developing? As a medical student in<br />

Germany, I joined the student governments in Göttingen and Lübeck<br />

and set up seminars and workshops about medicine in the developing<br />

world. To me it meant the whole world, although other people might<br />

have interpreted the series differently. I also joined World University<br />

Service after participating in a training session and was chosen as a<br />

student board member.<br />

I did my doctoral thesis in Zurich on a nationwide health campaign<br />

that was a bit of a joke in the Swiss scientific community. But it fulfilled<br />

its purpose, and I learned about prevention and quality control. I moved<br />

on and set up a quality circle at a day clinic for children. I got a commendation<br />

and a raise for it. However, along with getting my doctor’s title,<br />

these were rare moments of professional pride as a doctor.<br />

As a physician, I kept to the principle of recording patient histories and<br />

chief complaints verbatim. They tell us to do that in med school. But people<br />

say funny things, and doctors often paraphrase patient histories to make<br />

them fit their diagnostic ruminatings and preconceptions. One woman,<br />

a psychiatric patient with diabetic complications, kept insisting her chief<br />

complaint was “the heat inside.” I had no clue what she meant. But I wrote<br />

it down. My consultant later said I couldn’t write that because who knew<br />

what “the heat inside” was? There was no such medical term. Which was<br />

my point exactly; it was the woman’s complaint. If we don’t accept that<br />

she knows her main complaint, who does? He thought I should have pri-<br />

14<br />

Marie Dixon Frisch attended Yale, then studied<br />

medicine in Göttingen and Lübeck, Germany,<br />

completing her doctorate at the University of Zürich<br />

in 1998. She retired from medicine in 2003 and<br />

later became a clown, writer, and English teacher.<br />

She now lives in Norway and plans to work as a<br />

communal clown in nursing homes, social and<br />

medical institutions, and prisons.<br />

oritised the referring physician’s problem with a diabetic control/management<br />

plan. I thought to myself, “It’s no wonder people don’t get healthy<br />

when we don’t even pay attention to what’s important to them.” The point<br />

was lost on him, but it remains forever etched in the woman’s docket. My<br />

tribute of respect to her. And to the truth of medical mysteries unsolved.<br />

I came to see myself more as a therapist than a doctor. The latter is a<br />

position of exaltation, the former one of service. A therapist is a servant.<br />

A doctor prescribes; a therapist accompanies, supports. I loved psychotherapy<br />

training and probably got more out of it than my clients did.<br />

I went on a Patch Adams healing tour of Russia, visiting prisons. The<br />

prison wardens got upset because they were afraid of losing control of their<br />

juvenile detainees as a result of the clowning. I defused the tension at one<br />

prison by handing the head lady a bar of melting Jamaican chocolate with<br />

a comment in bad Russian and an apologetic tone. It saved the moment.<br />

My clown has also manifested itself through political power. Returning<br />

to Jamaica in 2007, over twenty years after <strong>UWC</strong>, I was appalled<br />

by the state of the nation. With the support of a group of largely <strong>UWC</strong><br />

friends, I began a campaign to depose the government which had been<br />

in power too long. But the government was only symptomatic; I also did<br />

a lot of grassroots work to show people options and alternatives, working<br />

with environmental groups and the organic movement, as well as doing<br />

small-time clowning work.<br />

Then I threw a snowball, which had an avalanche effect. My snowball<br />

was suggesting people take the government to court over an environmen-<br />

p On Patch Adams’ Healing Tour of Russia 2003 where we almost got banned for inciting JOY amongst the inmates and disturbance amongst the guards. A mushy bar of p<br />

Jamaican chocolate softened the fronts.<br />

<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong> / WWW.<strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>.ORG

tal issue. It was done by others and they won the case—the Pear Tree<br />

Bottom Case. I doubt anyone besides a few select friends even realized I<br />

threw the snow ball. It was one of those clown actions you do and tiptoe<br />

away before the fall-out comes, giggling guiltily but gleefully all the way.<br />

In connection with the same political issues, I upstaged the reigning<br />

Prime Minister of Jamaica in her own court. I had asked for permission<br />

to stage a demonstration against the Pear Tree Bottom development, and<br />

permission was first delayed and then denied. But I had prepared all the<br />

protest materials, including some self-composed protest songs. Shortly<br />

after, I was asked to attend a meeting set up by PM Portia Simpson Miller<br />

for political and NGO activists from the region. The PM allowed herself to<br />

be an unthinkable 90 minutes late for the meeting; two or three hundred<br />

delegates who had travelled for hours to get there were waiting, and while<br />

we waited, I asked permission to lead the group in song. After ascertaining<br />

my identity (i.e., nobody), they shrugged their shoulders and agreed.<br />

I began with “We Shall Overcome.” They sang that readily enough.<br />

Then I delivered my protest songs, getting them to join in the choruses.<br />

The conference room rocked. And the tactic wasn’t lost on them. By the<br />

time the PM came, the hall was abuzz. Many of her supporters signed the<br />

petition I had taken along to prohibit the government’s planned exploitation<br />

of the Cockpit Country, the next endangered area on our list.<br />

After 9/11, my life fell apart. My first husband and I separated that<br />

week. I started to re-examine my life, exploring possibilities. I was working<br />

in child and adolescent psychiatry in Zurich at the time. I was really<br />

good at play therapy and resource activation, client rapport. I took a<br />

therapeutic magic course and, while there, made everyone laugh. In that<br />

moment I remembered my clown. I realized that the clown was my core,<br />

and the doctor and therapist were adjunct.<br />

I had always wanted to be a good doctor. I had loved our family doctor<br />

and wanted to emulate him. But the clown was never something I had to<br />

become. I was a clown. I am a clown.<br />

I moved out of hospitals and clinics and into the world because that’s<br />

where sickness begins and can be prevented. I don’t believe we’ve understood<br />

how life and health really work. I believe our medicine is clumsy<br />

at best. Healing comes from within, and much of what we do prolongs<br />

suffering instead of curing it. It became increasingly difficult to practice<br />

p Meddling with a motor. A bit like medicine. p Clowning around.<br />

medicine as prescribed by current standards, and giving it up was the<br />

best decision I’ve made. I had been feeling the conflict of interest acutely:<br />

being a doctor, I was dependent on other people’s suffering for my livelihood.<br />

As a clown, I am independent. I also am able to do low-level interventions<br />

that people don’t even recognize as therapeutic.<br />

My current job working as an English trainer for unemployed Germans<br />

manifested itself miraculously because I followed my heart and nose<br />

and feet. I was handed the job on a platter and grabbed it. I do mostly selfworth<br />

building, group and team building, fostering creativity and limitless<br />

thinking and encouraging participants to create a better future. They think<br />

I’m teaching them English. I make them do a lot, stretch them to capacity<br />

and beyond, but they don’t notice. They think it’s all just fun and games.<br />

I work as an undercover clown in different capacities and rarely do<br />

open clown gigs at the moment. An undercover clown uses the power of<br />

the moment; right action, pure intention and awareness are some of the<br />

guiding principles I strive for. So I can’t foretell what I will do until I see<br />

what needs to be done.<br />

My job is to scatter seeds and to move on, let the wind do with them<br />

as it will. I am good at validating others, clients, colleagues, and superiors<br />

alike; it makes no difference to me. Strangers, too: a smile, a shared moment<br />

of pleasure or suffering.<br />

Looking back, we sometimes catch a glimpse of the impact of what<br />

we have done. But I never have the feeling I can see the whole picture. It’s<br />

not my job to hang on. I always have to let go, let go joyfully and gratefully<br />

so things can take their course.<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE / SPRING 2011 15<br />

Photos c0urtesy of Marie Dixon Frisch

<strong>LIVING</strong> <strong>UWC</strong> <strong>AFTER</strong> <strong>UWC</strong><br />

Abuubakar Ally ’12<br />

Tanzania<br />

Inspired by “Theme for English B,”<br />

by Langston Hughes<br />

The instructor said<br />

Go home and write<br />

A page tonight<br />

And let that page come out of you—<br />

Then it will be true.<br />

I doubt if it’s that simple.<br />

I am seventeen, young, but old, born<br />

in Migo-Dar.<br />

I grew up there, went to school at Kino<br />

One hour drive from there. Then here<br />

To this college, amidst the canyons<br />

of Montezuma.<br />

Twenty-two hour flight.<br />

I am the oldest student in my class.<br />

The steps near the science building lead up<br />

to the castle<br />

Where I take the elevator, up to my room,<br />

sit down and write this page:<br />

It’s difficult to know what’s true for you or me<br />

At seventeen, my age. But I think I am what<br />

I believe, feel and consider,<br />

My life, I hear you, hear me, we two, talk on<br />

this page.<br />

I like to eat well, sleep well, hang out with<br />

friends, but how?<br />

I like to enjoy my life, with my mom,<br />

dad, siblings,<br />

But where are they?<br />

continued on page 17...<br />

Alumni Profiles<br />

Gio Bacareza ’89, Philippines, completed two<br />

engineering majors in the Philippines and<br />

went on to spend two years in Spain working<br />

for Telefonica. An inspirational letter from a<br />

high school teacher prompted Gio to return<br />

home to help with Philippine technology development.<br />

Gio spent three years with Microsoft,<br />

moving on to support start-ups by working for<br />

a local venture<br />

capitalist where<br />

he handled the selection<br />

of investments<br />

in locally<br />

developed technology.<br />

In 2006,<br />

Gio brought innovations<br />

from<br />

Chikka.com, one<br />

of his investee<br />

companies, to<br />

international markets in the US, Europe, and<br />

Latin America. In 2009, he pitched and sold<br />

the company to Smart Communications, the<br />

largest mobile operator in the Philippines. Gio<br />

now runs Smart’s Internet business. He says,<br />

“My vision is to provide internet for everyone<br />

in the country. I’ve always believed that technology<br />

is the great equalizer. It promotes opportunity<br />

and equal access to information and<br />

education. One of the projects I’m very excited<br />

about right now is providing internet to those<br />

who cannot afford basic telephones.”<br />

Gio also organizes rescue and relief efforts<br />

such as those needed during the Ketsana<br />

Typhoon flood in Sept 2009. He also helped<br />

organize the citizen election monitoring group<br />

during the Philippine general elections in<br />

2010. Of his experience at <strong>UWC</strong>-<strong>USA</strong>, Gio<br />

says “The fortunate chance gave me a sense of<br />

responsibility to be an instrument for change<br />

from which I have chosen my path and purpose<br />

in life.”<br />

Aurelio Ramos ’91, Colombia, earned a bachelor’s<br />

degree in Economics from Colombia’s Universidad<br />

de los Andes and a master’s degree in Environmental<br />

Economics and Natural Resources<br />

from the University of Maryland and the Universidad<br />

de los Andes. He has worked with the<br />

Andean Development Bank, the Biotrade Program<br />

of the United Nations Conference of Trade<br />

and Commerce, and the Humboldt Biological<br />

Research Institute. Aurelio began working with<br />