Twilight of a Neighborhood - North Carolina Humanities Council

Twilight of a Neighborhood - North Carolina Humanities Council

Twilight of a Neighborhood - North Carolina Humanities Council

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SUmmer • Fall 2010<br />

CROSSROADS<br />

A PublicAtion <strong>of</strong> the north cArolinA humAnities council<br />

<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Neighborhood</strong><br />

Sarah M. Judson, Department <strong>of</strong> History, University <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> at Asheville<br />

Driving DOwn South French Broad Avenue<br />

in Asheville, travelers see a sign that reads “Know<br />

our Past, grow our Future.” This message is strikingly<br />

relevant to many Asheville neighborhoods, but<br />

perhaps particularly to the predominantly African<br />

American “East End.”<br />

“<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood: Asheville’s East End,<br />

1970,” was a multi-faceted public humanities project<br />

funded in part by the north <strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong><br />

<strong>Council</strong>. it was organized around Andrea Clark’s<br />

powerful photographs which explore the community’s<br />

life before and after the impact <strong>of</strong> urban renewal<br />

there. The discussions and interviews <strong>of</strong> the “<strong>Twilight</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> a neighborhood” project revealed a wide array <strong>of</strong><br />

viewpoints that <strong>of</strong>ten contradicted each other and<br />

signaled that the history <strong>of</strong> urban renewal is complex<br />

and shaded. Among the factors that influenced<br />

responses were race, age, gender, and class. The<br />

project helped energize an emerging movement <strong>of</strong><br />

concerned Asheville citizens who believe that their<br />

culture and history will shape how they live in the<br />

present and define the future.<br />

Asheville was one <strong>of</strong> many cities across the United<br />

States that participated in urban renewal, part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

national effort during the 1950s through the 1970s<br />

to improve so-called blighted areas <strong>of</strong> cities. in<br />

theory, urban renewal would enhance the landscape<br />

<strong>of</strong> cities and provide displaced residents model<br />

housing. in practice, however, many rich and vibrant<br />

communities <strong>of</strong> color were flattened throughout the<br />

United States. replacing these neighborhoods were<br />

wide roadways, highways, and new multi-story buildings.<br />

residents, some <strong>of</strong> whom were homeowners,<br />

were either relegated to substandard public housing<br />

or forced to relocate elsewhere.<br />

Some scholars suggest that as many as 1,600<br />

African American neighborhoods were destroyed by<br />

urban renewal during three decades <strong>of</strong> public policy.<br />

Most African American neighborhoods in Asheville,<br />

many <strong>of</strong> which were over one hundred years old,<br />

were affected.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most significant outcomes <strong>of</strong> the programming<br />

was how relevant the East End experience<br />

was for residents <strong>of</strong> other neighborhoods. Urban<br />

renewal in Asheville took place over a broad cross<br />

section <strong>of</strong> the city and in a relatively short period <strong>of</strong><br />

time. As a result, urban renewal was a continuous<br />

experience for Asheville’s African American community<br />

for almost thirty years. Beginning with the<br />

Hill Street neighborhood in 1957 as the Cross-Town<br />

Expressway was built and moving on to Southside,<br />

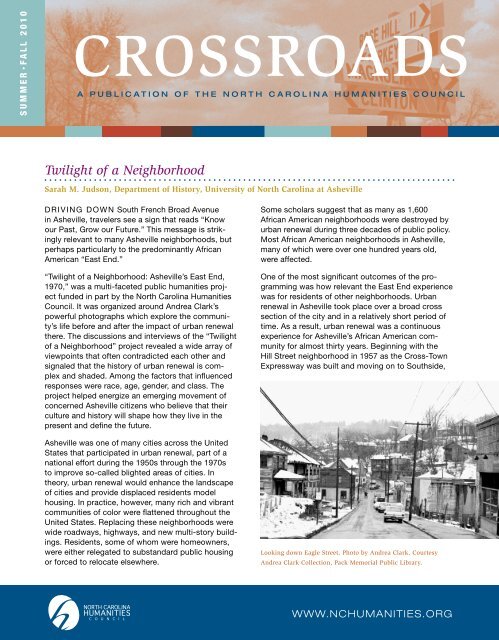

Looking down Eagle Street. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy<br />

Andrea Clark Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

www.nchumanities.org

Stumptown, Burton Street, and East End, the fabric<br />

<strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these historic African American communities<br />

was torn apart.<br />

Dr. Mindy Fullilove, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> clinical psychiatry<br />

and public health at Columbia University, defines this<br />

process as “root shock” in her groundbreaking Root<br />

Shock: How Tearing Up City <strong>Neighborhood</strong>s Hurts<br />

America and What We Can Do About It. root shock,<br />

according to Fullilove, is “the traumatic stress reaction<br />

to the loss <strong>of</strong> some or all <strong>of</strong> one’s emotional ecosystem.”<br />

This devastation <strong>of</strong> social networks, Fulliove<br />

explains, “is a pr<strong>of</strong>ound…upheaval that destroys the<br />

working model <strong>of</strong> the world that had existed in the<br />

individual’s head”; it results in a rupturing <strong>of</strong> individual<br />

and communal identity.<br />

As people looked at Clark’s photographs and<br />

attended programs, they voiced their experiences<br />

as a pr<strong>of</strong>ound sense <strong>of</strong> loss; they had a keen<br />

Vol. 14, Issue 1,<br />

s ummer/Fall 2010<br />

Guest Editor: Karen Loughmiller<br />

Managing Editor and Publisher:<br />

Harlan Joel Gradin, Associate<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Programs/Director <strong>of</strong><br />

Community Development, <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong><br />

<strong>Council</strong> Staff:<br />

Shelley J. Crisp<br />

Lynn Wright-Kernodle<br />

Genevieve Cole<br />

Darrell Stover<br />

Jennifer McCollum<br />

Donovan McKnight<br />

Carolyn Allen<br />

Anne Tubaugh<br />

Tim Wolfe<br />

Design:<br />

Kilpatrick Design<br />

www.kilpatrickdesign.com<br />

Founding Publication<br />

Team <strong>of</strong> Crossroads:<br />

Katherine Kubel<br />

Pat Arnow<br />

Mary Lee Kerr<br />

Lisa Yarger<br />

Harlan Joel Gradin<br />

IssN 1094-2351 ©2010<br />

addItIoNal resources<br />

Brunk, Robert S., ed., May We All Remember<br />

Well: A Journal <strong>of</strong> the History & Culture <strong>of</strong><br />

Western NC. Vol. 2. Asheville: Robert S.<br />

Brunk Auction Services, Inc., 1983.<br />

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How<br />

Tearing Up City <strong>Neighborhood</strong>s Hurts<br />

America and What We Can Do About It.<br />

New York: One World/Ballantyne, 2005.<br />

Hanchett, Thomas W. Sorting Out the New South<br />

City: Race, Class, and Urban Development<br />

in Charlotte, 1875–1975. Chapel Hill:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Press, 1998.<br />

Mosley-Edington, Helen. Angels Unaware:<br />

Asheville’s Women <strong>of</strong> Color. Asheville:<br />

Home Press, 1996.<br />

—.Visionaries: Asheville’s Women <strong>of</strong> Color.<br />

Asheville: Home Press, 2000.<br />

Neufeld, Rob, and Henry Neufeld. Asheville’s<br />

River Arts District (Images <strong>of</strong> America: <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Carolina</strong>). Charleston: Arcadia Publishing,<br />

2008.<br />

oNlINe collectIoNs aNd exhIbIts<br />

The Andrea Clark Photographic Collection. <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Carolina</strong> Collection, Pack Library, Buncombe<br />

County Public Libraries, Asheville, NC. www.<br />

buncombecounty.org/governing/depts/library/<br />

Gallery/andreaClark/default.htm.<br />

Asheville Housing Authority Records and<br />

Heritage <strong>of</strong> Black Highlanders Collection.<br />

D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> at Asheville.<br />

http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/mss/blackhigh/default_blackhigh.html.<br />

An Unmarked Trail: Stories <strong>of</strong> African Americans<br />

in Buncombe County from 1850–1950.<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> what the cost <strong>of</strong> urban progress<br />

meant for them.<br />

Southside resident robert Hardy poetically describes<br />

his own experience: “But the Land!…The community<br />

breakdown: family displacement and the loss <strong>of</strong> businesses,<br />

neighbors, continuity, sanguinity, customs,<br />

cultures, and social norms.” One tangible symbol <strong>of</strong><br />

this process was the change <strong>of</strong> the name <strong>of</strong> valley<br />

Street to South Charlotte Street after a relative <strong>of</strong> one<br />

<strong>of</strong> Asheville’s largest slave owners, Charlotte Patton.<br />

“<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood” alerted all <strong>of</strong> Asheville<br />

to the personal stories <strong>of</strong> how people experienced<br />

the past. Andrea Clark’s photographs capture the<br />

full spectrum <strong>of</strong> community life in Asheville’s East<br />

End in 1970. The images portray a neighborhood<br />

with bustling business and street life, gardens where<br />

people grew their own food, and sidewalks on which<br />

children played under the watchful eyes <strong>of</strong> elders.<br />

Digital Exhibit. Center for Diversity<br />

Education, University <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong><br />

at Asheville, 2008. www.diversityed.org/<br />

unmarked-trail.<br />

With All Deliberate Speed: School Desegregation<br />

in Buncombe County. Digital Exhibit. Center<br />

for Diversity Education, University <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Carolina</strong> at Asheville. www.diversityed.org/<br />

deliberate-speed.<br />

specIal thaNks<br />

This expanded edition <strong>of</strong> Crossroads has been<br />

made possible by contributions to the <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> <strong>Council</strong> from the following<br />

donors:<br />

• SF James and Diane M. Abbott<br />

• Rob Amberg and Leslie Stilwell<br />

• DeWayne Barton<br />

• Kenneth Betsalel and Heidi Kelley<br />

• Andrea Clark<br />

• Harlan Joel Gradin<br />

• Johnnie Robinson Grant<br />

• Harry Harrison<br />

• Buck Hinman<br />

• Holly Jones<br />

• Millie Jones<br />

• Karen Loughmiller<br />

• Mountain Housing Opportunities<br />

• Dwight and Dolly Mullen<br />

• Betsy Murray<br />

• Priscilla Ndiaye<br />

• Marc Rudow and Deborah Miles<br />

• James Samsel and Kim McGuire<br />

• Will Scarbrough<br />

• Ed Sheary<br />

• Stephens-Lee Alumni Association, Inc.<br />

• Jonathan Tambellini<br />

• UNC Asheville Center for Diversity Education<br />

• UNC Asheville Intercultural Center<br />

• Alexandra J. Vrtunski<br />

•<br />

Cindy Visnich Weeks

This neighborhood was home to Stephens-Lee High<br />

School, the only African American public high school<br />

in western north <strong>Carolina</strong>. To those who lived there,<br />

East End was not a blighted or slum area, though at<br />

the same time poor housing conditions characterized<br />

many <strong>of</strong> the structures. Housing codes were not<br />

enforced and city <strong>of</strong>ficials failed to address damage<br />

from storms and sewage.<br />

Beginning on page eight, there are maps that<br />

visually locate the African American neighborhoods<br />

<strong>of</strong> Asheville discussed in this issue <strong>of</strong> Crossroads.<br />

They were rendered by Betsy Murray, an archivist<br />

at Pack Memorial Public Library, and include the<br />

East End, Southside, Stumptown and Hill Street,<br />

and Burton Street.<br />

Today, the dispossession <strong>of</strong> neighborhoods continues<br />

to resonate with most <strong>of</strong> those who were displaced.<br />

Many residents interviewed for the “<strong>Twilight</strong>”<br />

project discussed the painful severing <strong>of</strong> neighborhood<br />

ties and the disorientation that arises from<br />

not really knowing that a place is yours.<br />

However, it is not accurate to say that all residents,<br />

including African Americans, responded with acute<br />

pain. One project interviewee observed, “[i]t’s easy<br />

to get misty-eyed about…all the great collegiality and<br />

social networks…in these poor neighborhoods but a<br />

lot <strong>of</strong> people that lived [there]…were happy to get out<br />

<strong>of</strong> them…the point is it was mixed.”<br />

For some, urban renewal promised to rebuild cities<br />

and create positive changes in areas that looked as<br />

if they needed help. That there could be different<br />

understandings <strong>of</strong> the outcome <strong>of</strong> urban renewal<br />

illustrates how multi-dimensional this process really<br />

was. One <strong>of</strong> the key city administrators <strong>of</strong> urban<br />

renewal during the 1970s was David Jones, executive<br />

director <strong>of</strong> the Asheville Housing Authority (AHA).<br />

in 2008 he told Urban News that his job was “removing<br />

all substandard housing conditions to make a<br />

more livable environment for people who cannot do<br />

for themselves.” He continued, “People say the next<br />

thing they knew was that they looked up and they<br />

saw the bulldozers, but that’s not true. All <strong>of</strong> these<br />

urban renewal projects were pretty complicated.”<br />

in the same vein, Ken Michalove, Asheville’s city<br />

manager in the 1970s, recalls that “the urban renewal<br />

projects, the Opportunity Corporation, and the Model<br />

Cities Program helped make Asheville a livable community<br />

and helped make us...a top city in the United<br />

States to live in.” The issue is perhaps not what policies<br />

were implemented, but the ways in which they<br />

were implemented.<br />

Elijah Morgan at the entrance to the Savoy Hotel, 35 S. Market<br />

Street. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy Andrea Clark Collection,<br />

Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

Ed Sheary, director <strong>of</strong> the Buncombe County Public<br />

Library, places in sharp relief the power <strong>of</strong> Clark’s<br />

photographs to force personal reassessment <strong>of</strong> this<br />

period. He writes, “i am a fifty-four-year-old white<br />

male Asheville native, who well remembers the East<br />

End and watched it being demolished in the name<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘urban renewal.’ i did not question the wisdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> tearing down and replacing substandard housing<br />

[until viewing]…Andrea Clark’s photographs….[Then]<br />

i saw the loss <strong>of</strong> neighborhood and all the human<br />

connections that entails.”<br />

right now, many residents from all over Asheville<br />

want to reclaim this history. There are efforts directed<br />

at renaming South Charlotte Street, creating a walking<br />

tour <strong>of</strong> the East End, and working to affect decisions<br />

about another road set to divide Burton Street.<br />

while the consequences <strong>of</strong> urban renewal may be<br />

difficult to dismantle, a renewed interest in this subject<br />

is sparking citizen engagement in determining<br />

the future.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 3

About “<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Neighborhood</strong>: Asheville’s East End, 1970”<br />

Harlan Joel Gradin<br />

in 2008, Buncombe County Public Libraries and<br />

partners, the Center for Diversity Education, and the<br />

Stephens-Lee Alumni Association, received planning,<br />

mini-, and large grants from the north <strong>Carolina</strong><br />

<strong>Humanities</strong> <strong>Council</strong> for the project “<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a<br />

neighborhood: Asheville’s East End, 1970,” which<br />

was fueled by the passion and vision <strong>of</strong> photographer<br />

Andrea Clark and project director Karen Loughmiller.<br />

Project team members included photographer rob<br />

Amberg, Stephens-Lee High School alumna Pat<br />

griffin, Sarah M. Judson <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> north<br />

<strong>Carolina</strong> Asheville, public historian and director <strong>of</strong> UnC<br />

Asheville’s Center for Diversity Education Deborah<br />

Miles, archivist Betsy Murray, community historian<br />

Henry robinson, and Buncombe County Public Library<br />

Director Ed Sheary. The project utilized Clark’s extraordinary<br />

photographs from 1970 to examine in depth<br />

the history and consequences <strong>of</strong> urban renewal. while<br />

the initial geographic focus was East End, the project<br />

grew beyond those parameters as participants<br />

shared stories about urban renewal disruptions across<br />

Asheville’s African American communities. A culminating<br />

weekend <strong>of</strong> related events was hosted by a large<br />

group <strong>of</strong> community partners including UnC Asheville,<br />

the YMi Cultural Center, the Urban News, A-B Technical<br />

Community College, among others.<br />

The East End had been a vibrant black community since<br />

the 1880s, although African American presence there<br />

dates back to the earliest times <strong>of</strong> slavery in western<br />

north <strong>Carolina</strong>. The neighborhood flourished through<br />

the first half <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century, perhaps even as<br />

the practices <strong>of</strong> urban renewal began in the city in the<br />

1950s. By 1978, urban renewal had razed much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

once strong family <strong>of</strong> neighbors.<br />

Fortunately, Andrea Clark had taken intimate portraits<br />

<strong>of</strong> local life in 1970, before the neighborhood disappeared.<br />

Few knew <strong>of</strong> this collection <strong>of</strong> photographs,<br />

until “<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood.” Project activities<br />

included an exhibit, expansion <strong>of</strong> recent research and<br />

gathering <strong>of</strong> oral histories, story-sharing sessions,<br />

book discussions, and public forums, as well as related<br />

programs including a class at UnC Asheville and the<br />

current examination <strong>of</strong> revitalization in Asheville.<br />

Today, there is serious discussion <strong>of</strong> urban revitalization<br />

in Asheville that likely will include many more<br />

voices than in the mid-1970s. One important result <strong>of</strong><br />

“<strong>Twilight</strong>,” Loughmiller observes, is the ongoing partnership<br />

that emerged from participants’ “struggles…<br />

[in] learning to work together.” She continues, “Projects<br />

4 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

Josie McCullough in the doorway <strong>of</strong> her home overlooking the busy<br />

intersection <strong>of</strong> Valley and Eagle Streets. Photo by Andrea Clark.<br />

Courtesy Andrea Clark Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

that allow collaborative experiences to happen can<br />

empower people in a very real way and give momentum<br />

to the effort to reclaim control <strong>of</strong> our lives and our<br />

communities. in today’s world, what could be more<br />

important?”<br />

A core notion <strong>of</strong> “<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood” is “root<br />

shock,” a term developed by urban scholar and psychiatrist<br />

Mindy Fullilove, the keynote speaker at the project’s<br />

conclusion in February 2009. in a recent note to project<br />

participants, Fulillove quoted the European urban visionary<br />

Michel Cantal-Dupart, who wrote that “the cities <strong>of</strong><br />

the future are cities that have a past and they must lean<br />

on that past to find the way to break barriers and to<br />

create the means <strong>of</strong> sustaining our children one hundred<br />

years from now.” The exciting, organic, and intentional<br />

group <strong>of</strong> citizens who now have practice voicing their<br />

history in the most public way are reclaiming their past<br />

to define their future; they plan to sustain their children<br />

one hundred years from now.

Andrea Clark, Photographer: The Family <strong>of</strong> Man/These Were My Roots<br />

Karen Loughmiller, West Asheville Branch Library<br />

AnDrEA CLArK’S East End photographs are<br />

stunning. They hold your attention. You look at one,<br />

walk away, come back to look again. And again.<br />

“what was she thinking about?” you wonder. in an<br />

interview with documentary photographer and friend<br />

rob Amberg, Clark mused, “i was really thinking<br />

about the family <strong>of</strong> man...about that photograph that<br />

transcends you.” Yes. You see it.<br />

But wonderful as the images are, Andrea Clark<br />

herself ensured that the questions they evoke in our<br />

minds were discussed publicly. Clark saw from the<br />

first that the East End photographs <strong>of</strong>fered a way into<br />

the true story <strong>of</strong> her new community and its collision<br />

with urban renewal. More than three decades later,<br />

Clark envisioned that a full accounting <strong>of</strong> community<br />

history on the issue <strong>of</strong> urban renewal was essential<br />

to reckoning with the past which might lead to reconciliation<br />

and healing for people and the city. Tirelessly<br />

encouraging participation, Clark was the mighty<br />

heart <strong>of</strong> the “<strong>Twilight</strong> <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood” project.<br />

Although her father was from Asheville, Clark was<br />

born and raised in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After<br />

studying nursing for a short time, Clark went to photography<br />

school. She says, “i was young, footloose,<br />

and curious about the Civil rights Movement in the<br />

South. And i wanted to reconnect with my father and<br />

his family. in 1968 i took a Pullman porter to Asheville,<br />

and moved in with my family on valley Street.”<br />

For Clark, her new home “was like a little hamlet,”<br />

and although “valley Street was one <strong>of</strong> the poorer<br />

sections <strong>of</strong> town…i loved the spirit <strong>of</strong> the community.<br />

Folks were sweet and friendly.…i felt very comfortable<br />

here…and when you walked up Beaucatcher<br />

Mountain at night with the beautiful view <strong>of</strong> the city<br />

lights, you were standing in a black neighborhood.”<br />

“i took my camera everywhere with me,” she told<br />

Amberg. “i always received a warm reception —<br />

i think it shows in the faces in the photographs.<br />

i learned about my father’s family. i found a sanctuary<br />

here and kept coming back. i felt these were<br />

my roots.”<br />

The photographs <strong>of</strong> Andrea Clark<br />

bring what was and what was lost<br />

into our complex present.<br />

—Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove<br />

Andrea Clark. Photo by Betsy<br />

Murray.<br />

Houses in East End. Photo<br />

by Andrea Clark. Courtesy<br />

Andrea Clark Collection,<br />

Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 5

The Patton Family<br />

AFriCAn<br />

AMEriCAnS helped<br />

create what we know<br />

today as home. The<br />

Courtesy uNC Asheville. labors <strong>of</strong> women and<br />

men helped build our<br />

land while the lives they led shaped the mountain<br />

culture. Other urban communities in South <strong>Carolina</strong><br />

and elsewhere have hosted archaeology projects to<br />

document these footprints <strong>of</strong> early builders and have<br />

gained economically, with increased tourism, from<br />

the treasures they discovered.<br />

A likely archeological site is the heart <strong>of</strong> old East<br />

End. By 1811, enslaved people, owned by James<br />

Patton, worked at the Eagle Hotel and lived within a<br />

short walk behind the current Public works Building.<br />

Further investigation would reveal the nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

relationship <strong>of</strong> the enslaved with other founders <strong>of</strong><br />

6 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

Henry Robinson, Community Historian<br />

ASHEviLLE’S EAST<br />

EnD was the probable<br />

site <strong>of</strong> dwellings <strong>of</strong><br />

James Patton’s family’s<br />

slaves prior to the<br />

Civil war. A Scots-irish<br />

immigrant who arrived<br />

in Asheville in 1811,<br />

EAGLE HOTEL LOCATION PATTON HOME WORKERS’ HOMES<br />

Patton and his descendants were instrumental in the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> tourism (hotels), roads, railroads, and<br />

other community initiatives. Prior to the Civil war, the<br />

Patton family ranked second in Buncombe County in<br />

number <strong>of</strong> slaves owned, after the woodfin family.<br />

And, it was in this area that newly-freed African<br />

Americans gathered during reconstruction to build<br />

an enduring community that would provide social,<br />

commercial, religious, and educational opportunities<br />

in a segregated society.<br />

The map shows the Patton family home and the<br />

location <strong>of</strong> the Eagle Hotel which they owned and<br />

staffed first with slaves and later with freed African<br />

Americans. Also indicated on the map is a group <strong>of</strong><br />

homes on valley Street constructed to house black<br />

laborers and their families. These homes became the<br />

nucleus <strong>of</strong> the East End.<br />

(L) Map <strong>of</strong> East End Asheville, 1891. Courtesy <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong><br />

Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library. (Above) Henry<br />

Robinson. Photo by Johnnie Grant, Urban News.<br />

Restoring a Voice: The Case for Urban<br />

Archaeology in Asheville’s East End<br />

Dwight Mullen, Department <strong>of</strong> Political Science, UNC Asheville<br />

what became Asheville. Quality <strong>of</strong> life issues also<br />

need substantiation. what did people who were<br />

owned by other people eat? what did they do with<br />

the little time they had to themselves? where specifically<br />

did they live? Many questions can be addressed<br />

through expertly directed mapping and excavation <strong>of</strong><br />

selected sites in the city.<br />

what lies beneath our feet in downtown Asheville<br />

is an important way to document the presence<br />

and contributions <strong>of</strong> African Americans in north<br />

<strong>Carolina</strong>’s mountains. The doorpost <strong>of</strong> a home or a<br />

cup held for drinking adds layers <strong>of</strong> connection and<br />

meaning to the past.<br />

we must not lose this opportunity to restore a voice<br />

about how our history was made and who made it.<br />

The knowledge we gain will inform how we live and<br />

will enrich the culture we make in the future.

Re-Storying Community: Lessons from African<br />

American Stories <strong>of</strong> Urban Renewal in Asheville<br />

Ken Betsalel, Department <strong>of</strong> Political Science, UNC Asheville, and Harry<br />

Harrison, Executive Director, YMI Cultural Center<br />

in THE SPring OF 2009 we co-taught a course<br />

on the impact <strong>of</strong> urban renewal on the lives <strong>of</strong> African<br />

Americans living in Asheville, north <strong>Carolina</strong>. One<br />

goal <strong>of</strong> the course was to restore a sense <strong>of</strong> community<br />

that had been lost due to urban renewal, while<br />

linking students to humanities-based perspectives<br />

on community-building. Each week students heard<br />

from community “story-holders” who experienced<br />

urban renewal first-hand. Community participants<br />

and students also took a tour <strong>of</strong> local urban renewal<br />

sites and studied photographs and maps that helped<br />

tell the story <strong>of</strong> urban renewal’s devastating impact<br />

on the cohesiveness <strong>of</strong> African American neighborhoods.<br />

Together we learned some valuable lessons.<br />

The first lesson was the importance <strong>of</strong> trust. without<br />

trust there is no community-building. The second lesson<br />

was the importance <strong>of</strong> “home place” in building<br />

a community. Holding our weekly sessions at the YMi<br />

Cultural Center, one <strong>of</strong> the oldest African American<br />

cultural centers in the country, gave a sense <strong>of</strong> security<br />

and validation, especially to community people<br />

as they shared with us.<br />

The third lesson is the importance <strong>of</strong> the story itself.<br />

while story telling sometimes opens up old wounds,<br />

(Sidney) Feldman’s Grocery, 91 Eagle Street. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy Andrea<br />

Clark Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

it also has the<br />

capacity to heal,<br />

as those who told<br />

their stories came<br />

to value their<br />

experience in new<br />

ways. More than Hattie M. Sinclair, 119 Valley Street, circa<br />

one participant 1968. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy<br />

told how, while it Andrea Clark Collection, Pack Memorial<br />

was painful to tell Public Library.<br />

<strong>of</strong> the past, they<br />

were thankful that others might find their stories useful<br />

in creating a better community for everyone.<br />

Finally, we learned the value <strong>of</strong> listening. Story telling<br />

gave everyone a chance to slow down and listen!<br />

The separation inflicted by urban<br />

renewal still haunts many people.<br />

—Johnnie Robinson Grant, East End Resident<br />

How Does One Begin<br />

to Tell the Story?<br />

Wanda Henry Coleman,<br />

Former East End Resident<br />

and First Director <strong>of</strong> the YMI<br />

Cultural Center<br />

How do you begin to frame the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> displacement <strong>of</strong> a raucous, “livingout-loud”<br />

neighborhood with all its color,<br />

tragedy, and comedy?<br />

When did we forfeit our safe havens, our<br />

ports in storm, and become, by default or<br />

absence, participants in the destruction<br />

<strong>of</strong> or radically negative altering <strong>of</strong> what<br />

should have been dear to us? We have to<br />

think about how and why this happened<br />

and account for ourselves.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 7

The following neighborhood maps show some <strong>of</strong> the hundreds <strong>of</strong> institutions that sustained community and were a<br />

source <strong>of</strong> pride and identity for over 100 years before urban renewal. Inspired by the communities their elders knew,<br />

neighborhood associations are now focusing on the three E’s — Economy, Environment, and Equity — as they lead<br />

the way to an economically and environmentally sustainable future for communities, including the safe and affordable<br />

housing that once had been promised and now must become a reality.<br />

EAST EnD<br />

17<br />

14<br />

10<br />

CHUrCHES<br />

1. Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church — 47 Eagle St.<br />

2. Sycamore Temple Church <strong>of</strong> god in Christ<br />

3. Tried Stone Baptist Church — 2 Sorrell St.<br />

4. St. Matthias Episcopal Church — 6 Dundee St.<br />

5. Cappadocia Holiness Church — 58 Max St.<br />

6. Calvary Presbyterian Church — 44 Circle St.<br />

7. nazareth First Baptist Church — 60 Hazzard St.<br />

8. St. James CME Church — 44 Hildebrand St.<br />

9. Hopkins Chapel AME Church — 321 College St.<br />

10. Berry Temple UMC — 334 College St.<br />

SCHOOLS<br />

11. Southeastern Business School — 93-99 valley St.<br />

12. Stephens-Lee High School/Catholic Hill High School<br />

— 31 gibbons St.<br />

13. Mountain St./Lucy Herring School — 36 Clemmons St.<br />

14. Allen High School — 331 College St.<br />

D<strong>of</strong>fers in Cherryville.<br />

Map by Betsy Murray, Archivist, Pack Memorial Public Library. Based on a 1950 map <strong>of</strong> Asheville. Locations are approximate.<br />

8 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

9<br />

13<br />

27<br />

8<br />

26<br />

25<br />

7<br />

6<br />

22<br />

12<br />

11<br />

5<br />

28<br />

1<br />

2<br />

15<br />

16<br />

18<br />

19<br />

4<br />

24<br />

23<br />

21<br />

20<br />

COMMUniTY OrgAniZATiOnS<br />

15. YMi Cultural Center/Soda Shop/Drugstore — 37 S.<br />

Market St.<br />

16. Market Street Branch Library — YMi Building<br />

17. Phyllis wheatley YwCA — 356-360 College St.<br />

BUSinESSES<br />

18. Savoy Hotel and Café — 33-35 S Market St.<br />

19. roland’s Jewelry — 29 S. Market St.<br />

20. Club Del Cardo — 38 S. Market St.<br />

21. ritz restaurant — 42 S. Market St.<br />

22. James Macon Barber Shop — 89 Eagle St.<br />

23. <strong>Carolina</strong> Tobacco Corp., warehouse (music) —<br />

Beaumont & valley Streets<br />

24. Self-Serve Laundromat — 138 valley St.<br />

25. Mr. Bud walker’s Store — Bottom <strong>of</strong> Mountain St.<br />

26. good value Store — Pine & Clemmons Streets<br />

27. Porter’s Store — 58 Pine St.<br />

28. Eagle Street Theater — 51 Eagle St.<br />

3

Stephens-Lee High School, c. 1968. Photo<br />

by Andrea Clark. Courtesy Andrea Clark<br />

Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

Stephens-Lee High School & the Stephens-<br />

Lee Alumni Association<br />

Pat Griffin, Past President, Stephens-Lee Alumni Association<br />

TO BLACKS OF EAST EnD and throughout Buncombe County,<br />

Stephens-Lee High School, 1924–1964, symbolized Black education,<br />

achievement, independence, and culture. As the only high school to<br />

accommodate African American students in Buncombe County and<br />

surrounding counties, it was known for its classical music programs,<br />

drama productions, and beginning in the late 1930s, its marching<br />

band. Character, intelligence, fidelity, endurance, and fortitude were<br />

instilled in us daily as we learned and built lasting friendships within<br />

the hallowed walls <strong>of</strong> the “Castle on the Hill.”<br />

During the integration crisis <strong>of</strong> 1962–1972 the decision was made to<br />

close the school. After the demolition <strong>of</strong> the building, an idea was born<br />

for an alumni association which would work to retain the rich heritage<br />

that emerged from the school. A group <strong>of</strong> former students and teachers<br />

started the movement. The first alumni reunion was held in 1991;<br />

1,000 alumni attended! Today the association meets monthly and<br />

collaborates with other programs to emphasize to youth the ideals <strong>of</strong><br />

dignity and self-help, the heart <strong>of</strong> the Stephens-Lee legacy.<br />

The East Is Rising!<br />

Sarah Williams, East End <strong>Neighborhood</strong> Association<br />

On JAnUArY 21, 2010, after five years <strong>of</strong> inactivity, residents <strong>of</strong><br />

the East End came together for the good <strong>of</strong> the neighborhood. Those<br />

early meetings led to the East End Future Quest, which are visioning<br />

sessions that push community members to think about how they<br />

could foster self-improvement. Discussion topics included:<br />

• Our shared vision <strong>of</strong> the community in five to ten years<br />

• Challenges to make our vision a reality<br />

• Strategies to meet these challenges<br />

• An action plan<br />

Future goals include capturing the neighborhood’s history through<br />

discussions with elderly residents; working to improve neighborhood<br />

parks; working with the city on land use issues and future plans;<br />

developing a newsletter; and organizing volunteers.<br />

L I F E I N<br />

E A S T E N D ,<br />

A S H E v I L L E ,<br />

c . 1950–70<br />

You know, we were very close. It’s like,<br />

they talk about the village, it takes a<br />

village to raise a child. Well, that’s what<br />

we had. That was one <strong>of</strong> the things that<br />

was so joyful.<br />

~Bennie Lake<br />

East End was a community, a<br />

neighborhood, self-contained….It had<br />

hair-dressers. There were grocery<br />

stores, funeral parlors, cab stands.<br />

Eagle Street had doctors’ and lawyers’<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices, dentists’ <strong>of</strong>fices, churches. You<br />

had theaters. We had swimming pools.<br />

You had barbershops and the Dew<br />

Drop Inn. Miss McQueen’s restaurant<br />

was across from YMI. Roland’s Jewelry<br />

and Chisholm’s sold everything.<br />

~Ralph Bowen<br />

There was a time when every black<br />

person who wanted to make a living<br />

could make a living. There were<br />

eateries all up and down Eagle Street,<br />

up on the mountain. There were clubs<br />

everywhere.<br />

~Talven “Sugarbody” Thompson<br />

During the 1950s, East End was a place<br />

where everybody knew everybody and<br />

every child was reared, mentored,<br />

disciplined, protected, and taught — not<br />

only by their parents but by neighbors<br />

as well. Children attended Sunday<br />

School and an afternoon training class,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten accompanied by their parents.<br />

There was a partnership between the<br />

local church and the home.<br />

~Dr. Charles Moseley, Pastor,<br />

Nazareth First Baptist Church<br />

My mom told me, “Let me tell you<br />

something. If somebody comes to you,<br />

they need a place to stay, bring them<br />

in. They need food, feed them. If they<br />

need clothes, put clothes on their back.<br />

Don’t deny it.”<br />

~Jene Blake<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 9

SOuTHSIDE<br />

28<br />

17<br />

CHUrCHES<br />

1. Bethel 7th Day Adventist Church — 51 Adams St.<br />

2. Beulah Chapel Holiness Church — 111 Black St.<br />

3. Church <strong>of</strong> god in Christ — 292 Southside Ave.<br />

4. new Bethel Baptist Church — 508 S. French<br />

Broad Ave.<br />

5. new Mount Olive Baptist Church — 148 Livingston St.<br />

6. St. John’s Church <strong>of</strong> god — 100 Southside Ave.<br />

7. St. Luke’s AME Zion Church — 40 Bartlett St.<br />

8. Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church —<br />

Corner <strong>of</strong> Livingston and Congress Streets<br />

9. worldwide Baptist Tabernacle Church —<br />

85 Choctaw St.<br />

SCHOOLS<br />

10. Asheland Ave. School (Closed 1949) —<br />

190 Asheland Ave.<br />

Phyllis wheatley YwCA moved here<br />

11. Livingston St. Elementary School — 133 Livingston St.<br />

12. School <strong>of</strong> St. Anthony <strong>of</strong> Padua — 56 walton St.<br />

13. Stewart’s School <strong>of</strong> Beauty Culture — 55 Bartlett St.<br />

14. South French Broad High School — 197 S. French<br />

Broad Ave.<br />

10 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

10<br />

24<br />

19<br />

22<br />

30<br />

7<br />

1<br />

13<br />

15 14<br />

16<br />

6<br />

COMMUniTY OrgAniZATiOnS<br />

15. YwCA — 195 S. French Broad Ave.<br />

16. Elks Club — 382 S. French Broad Ave.<br />

17. Asheville Colored Hospital — 185 Biltmore Ave.<br />

18. w.C. reid Community Center — 133 Livingston St.<br />

BUSinESSES<br />

19. The Southern news — 121 Southside Ave.<br />

20. James-Keys Hotel — 409 Southside Ave.<br />

21. Allen-Birchette Funeral Home — 350 Southside Ave.<br />

22. Conley’s Barber Shop — 187 Southside Ave.<br />

23. Fair grocery — 452 S. French Broad Ave.<br />

24. Sportsman Club — 105 Southside Ave.<br />

25. walton St. Park and Pool — End <strong>of</strong> Depot St.<br />

26. McMorris Amoco Service — 71 McDowell St.<br />

27. rabbit’s Tourist Court & restaurant —<br />

110 McDowell St.<br />

28. Jesse ray Funeral Home — 185 Biltmore Ave.<br />

29. Southland Drive-in — 127 McDowell St.<br />

30. Mae McCorkle’s Beauty Shop — 87 Blanton St.<br />

Map by Betsy Murray, Archivist, Pack Memorial Public Library. Based on a 1950 map <strong>of</strong> Asheville. Locations are approximate.<br />

9<br />

26<br />

27<br />

3<br />

29<br />

23<br />

21<br />

20<br />

8<br />

5<br />

11<br />

18<br />

2<br />

4<br />

12<br />

25

Southside/East Riverside: Lost — In the Name <strong>of</strong> Progress<br />

Priscilla Ndiaye, Former Resident and Researcher <strong>of</strong> Southside <strong>Neighborhood</strong><br />

BY THE TiME <strong>of</strong> urban renewal, Southside was the<br />

city’s premier black business district, surrounded by<br />

a large residential neighborhood. At over four hundred<br />

acres, the urban renewal project here was the<br />

largest in the southeastern United States. The scale<br />

<strong>of</strong> the devastation here was unmatched.<br />

“in the East riverside area,” said the [late] reverend<br />

wesley grant, “we have lost more than 1,100 homes,<br />

six beauty parlors, five barber shops, five filling stations,<br />

fourteen grocery stores, three laundromats,<br />

eight apartment houses, seven churches, three shoe<br />

shops, two cabinet shops, two auto body shops,<br />

one hotel, five funeral homes, one hospital, and<br />

three doctor’s <strong>of</strong>fices.”<br />

The reverend grant’s<br />

church still stands on<br />

Choctaw Street.<br />

Multiple perspectives,<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge, much<br />

confusion, and discouraged<br />

and bitter individuals<br />

are all entwined<br />

as spiders in a web:<br />

any way you touch it,<br />

it trembles.<br />

The L-A-N-D<br />

Priscilla Ndiaye. Photo<br />

courtesy Story Point Media.<br />

Robert Hardy, Southside <strong>Neighborhood</strong> Association<br />

Oh — But the Land — But the L-A-n-D! The community<br />

breakdown: the loss <strong>of</strong> businesses, neighbors,<br />

continuity, sanguinity, customs, culture, social norms,<br />

and family displacement.<br />

Can one truthfully say there were no benefits? no!<br />

However, the benefits received when contrasted<br />

are a disproportionate negative to that which<br />

was gained!<br />

For the most part, the landowners were either<br />

elderly and/or sick; more times than not the gains<br />

and homes were obscured and/or lost due to the<br />

eroded economic base and failing subsequent<br />

infrastructure. Purchased at a give-away price, these<br />

properties were resold for sums unattainable by the<br />

descendants <strong>of</strong> the original owners.<br />

One perspective on this transformation sees families<br />

uprooted, relocated, and scattered; a community<br />

destroyed; a vibrant entrepreneurial business world<br />

shut down; and history fragmented, altered, and lost.<br />

A very different perspective sees economic benefits<br />

for the whole city and better living conditions for<br />

neighborhood residents.<br />

Asheville’s formal<br />

history was being<br />

made while Asheville’s<br />

African American history<br />

was lost — in the<br />

name <strong>of</strong> progress. in<br />

2008, for the first time<br />

an effort was made<br />

to collect this history<br />

through discussions<br />

and interviews<br />

[funded] by the YMi<br />

[Cultural Center]<br />

and the “<strong>Twilight</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> a neighborhood”<br />

project.<br />

Dewitt Street c. 1960. (L) Louvenia<br />

Booker. Center-Conaria Booker.<br />

Courtesy <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Collection,<br />

Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

Southside c. 1968. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy Andrea Clark<br />

Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

The resulting “fiasco” which we are now living is perpetual<br />

poverty for the descendants and gentrification<br />

<strong>of</strong> their land.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 11

STumpTOwn<br />

AnD HIll STrEET<br />

CHUrCHES<br />

1. Hill St. Baptist Church — Hill and Buttrick Streets<br />

2. welfare Baptist Church — 27 Madison St.<br />

3. Church <strong>of</strong> god — 13 gray St.<br />

4. Elder Perkins’ Church — Morrow St.<br />

5. varick Chapel AME Zion Church — 80 Hill St.<br />

6. Church <strong>of</strong> god in Christ — 89 gudger St.<br />

7. Church <strong>of</strong> god — 5 roosevelt St.<br />

SCHOOLS<br />

8. Hill Street School — 118 Hill St.<br />

COMMUniTY OrgAniZATiOnS<br />

9. Stumptown neighborhood Center — Madison St.<br />

12 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

BUSinESSES<br />

10. Morrow St. Corner Store — Morrow St.<br />

11. Mr. Howard’s Sweet Shop — 86 gay St.<br />

12. Chatham Brothers grocery — 7 gray St.<br />

13. Torrence Hospital — 95 Hill St.<br />

14. reed’s Coal Company — 8 Buttrick St.<br />

15. Mrs. Bernice williams Beauty Shop — 21 gudger St.<br />

16. Oliver groce grocery — 12 Barfield Ave.<br />

17. Mrs. Edith Adams Beauty Shop — 157 Hill St.<br />

18. Mrs. ruby Sherrill Beauty Shop — 153 Hill St.<br />

19. Midget ice Cream Parlor — 73 gay St.<br />

Map by Betsy Murray, Archivist, Pack Memorial Public Library. Based on a 1950 map <strong>of</strong> Asheville. Locations are approximate.<br />

Shaded area indicates original boundaries <strong>of</strong> Stumptown neighborhood.<br />

7<br />

19<br />

10<br />

1<br />

17<br />

18<br />

12<br />

11<br />

8<br />

3<br />

4<br />

16<br />

9<br />

2<br />

14<br />

13<br />

5<br />

6<br />

15

Hill Street <strong>Neighborhood</strong> —<br />

First to Fall<br />

LOCATED nEAr downtown Asheville, the Hill<br />

Street neighborhood was home to African Americans<br />

as early as 1900. in the 1950s, the community<br />

included working-class families who owned their<br />

homes, small businesses, a school, and several<br />

churches. Former resident Daryl wasson recalls:<br />

“You had this nice little community. These were all<br />

nice homes. They were cared for. There was nothing<br />

slovenly about it.” in the mid-1950s, the city started<br />

work on the Cross-Town Expressway, Asheville’s<br />

first superhighway.<br />

Squarely in its path, Hill Street homes began to fall.<br />

wasson says, “My mother and i watched them build<br />

the highway. in 1957 the highway department came<br />

Stumptown: A Dramatic Disruption<br />

Mrs. Clara Jeter, President, Stumptown<br />

<strong>Neighborhood</strong> Association and Ms. Pat McAfee,<br />

Community Historian.<br />

Around 1880, a thirty-acre tract in Asheville, near<br />

riverside Cemetery, was cleared for black residential<br />

use. Called Stumptown, the area attracted many<br />

black families who came to Asheville in search <strong>of</strong><br />

work. They formed a dynamic social network, and<br />

created a good, respectable community <strong>of</strong> homes,<br />

families, neighbors, and friends.<br />

Stumptown residents found employment in riverside<br />

Cemetery, at nearby Battery Park Hotel, or with<br />

affluent whites on Montford Avenue. By the 1920s,<br />

Stumptown’s population exceeded two hundred<br />

families. Although there was much poverty, we had<br />

treasures money cannot buy — pride, dignity, and<br />

self-respect, and most <strong>of</strong> all, love.<br />

Urban renewal came as a total surprise to us. we<br />

heard bits and pieces about a new program that<br />

promised better living conditions. And then, remembers<br />

Mrs. Dorothy ware, one day “my parents got a<br />

letter warning them they had only a few months to<br />

find a new home.” Other residents got similar letters.<br />

where would we go? How would we get to work and<br />

church? if it’s urban renewal, why is eminent domain<br />

being exercised? what’s really going on here?<br />

(L) Building <strong>of</strong> Cross-town (E–W) Expressway, 1958. Courtesy<br />

Asheville Citizen-Times. (R) Daryl Wasson and friend, 6 Cross<br />

Street, Hill Street <strong>Neighborhood</strong>, c. 1958. Courtesy Daryl Wasson.<br />

and took out all the houses except for three on our<br />

street (Cross St.). They came through again in ’65,<br />

and they cleaned the place out completely in ’67.”<br />

Dr. Mary Frances Shuford in front <strong>of</strong> community center in<br />

Stumptown, 1967. Courtesy Asheville Citizen-Times.<br />

Stumptown residents experienced root shock repeatedly<br />

over the next two decades, as our homes were<br />

bulldozed to the ground, one by one, and the social<br />

order was broken. By the early 1970s little was left.<br />

Scattered, hurt, bitter, discouraged — we strove to<br />

build new hopes. in spite <strong>of</strong> the devastation, the<br />

strong values <strong>of</strong> our old community are visible in the<br />

successful lives <strong>of</strong> our young people. Stumptown<br />

lives on through them.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 13

15<br />

CHUrCHES<br />

1. new Hope Mt. Carmel Baptist Church —<br />

26 Mardell Circle<br />

2. Antioch Church <strong>of</strong> god in Christ — 176 Burton Ave.<br />

3. Moss Temple AME Zion Church — 2 Mardell Circle<br />

4. St. Paul’s Missionary Baptist Church —<br />

170 Fayetteville St.<br />

5. wilson’s Chapel Methodist Episcopal —<br />

103 Burton Ave.<br />

SCHOOLS<br />

6. Burton Street School — 134 Burton Ave.<br />

COMMUniTY OrgAniZATiOnS<br />

7. Burton Street Community Center — 3 Buffalo St.,<br />

134 Burton Ave.<br />

14 • NORtH CAROLiNA HuMANitiES COuNCiL<br />

12<br />

10<br />

13<br />

16<br />

2<br />

1<br />

11<br />

BurTOn STrEET<br />

BUSinESSES<br />

8. E. w. Pearson grocery and Blue note Club —<br />

3 Buffalo St.<br />

9. Dudley Coal and ice — Burton Ave.<br />

10. Herbert Friday Barber Shop — 212 Fayetteville St.<br />

11. T. Friday Barber Shop — 173 Fayetteville St.<br />

12. Jerolene rice Beauty Parlor — Edgar St.<br />

13. Emma Mickins Beauty Parlor — Edgar St.<br />

14. iola Byers Beauty Parlor — 3 ½ Buffalo St.<br />

15. Elam’s Farm — End <strong>of</strong> Buffalo St.<br />

16. Elam’s grocery — 57 Buffalo St.<br />

Map by Betsy Murray, Archivist, Pack Memorial Public Library. Based on a 1950 map <strong>of</strong> Asheville. Locations are approximate.<br />

4<br />

8<br />

3<br />

7<br />

14<br />

6<br />

5<br />

9<br />

Historic Agricultural Fair Founded<br />

In Western <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> in the early 20th century,<br />

African Americans could not participate in county<br />

agricultural fairs. Burton Street community leader E.W.<br />

Pearson changed all that in 1914 when he organized the<br />

first Buncombe County and District Colored Agricultural<br />

Fair, held at Pearson’s Park in the Burton Street<br />

neighborhood. The fair attracted thousands yearly,<br />

black and white, and ran annually through 1947.<br />

E.W. Pearson collecting eggs at his home on Buffalo St. Courtesy<br />

<strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.

Asheville’s Burton Street community lost streets and homes in 1965 when i-240 was built. the<br />

neighborhood has recently been threatened by an i-26 Connector Alternative known as Alternative<br />

3. this alternative would destroy a federal Weed and Seed neighborhood. A concerted effort by<br />

Asheville residents prompted the NCDOt to look for ways to reduce the impact <strong>of</strong> the connector<br />

on the neighborhood. Residents still await a final decision.<br />

Burton Street: Behind the Crack Curtain — Creating a Vision<br />

DeWayne Barton, Co-founder <strong>of</strong> Asheville Green Opportunity Corps<br />

DeWayne Barton, co-founder <strong>of</strong> Asheville<br />

Green Opportunity Corps, is one young<br />

leader in the Burton Street neighborhood<br />

trying to address recent problems, such<br />

as drugs and violence, that have emerged<br />

with community decline resulting from<br />

urban renewal. Seeing the history <strong>of</strong><br />

urban renewal from a new generation’s<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view, he writes <strong>of</strong> transforming the present by listening to<br />

the stories <strong>of</strong> his elders. Barton is standing with Safi Mahaba, both<br />

are Burton Street residents. Photo by Dan Leroy.<br />

THE THrEATS: Eager nASCAr drivers looking<br />

for dope boys with the checkered flag. And race<br />

walkers, picturing their favorite drug medal around<br />

their neck — leaving behind small, clear plastic bags,<br />

empty lighters, and forty-ounce bottles. The ice<br />

cream truck <strong>of</strong> violence rolls through slowly, daily<br />

bell sounds <strong>of</strong> twenty-twos and forty-fives. i’ve seen<br />

this self-destructive pattern before in DC and virginia<br />

— drugs, bulldozers, developers — not knowing<br />

the i-26 expansion was behind Burton Street’s<br />

crack curtain.<br />

THE rESPOnSE: Listening to the warning cries<br />

<strong>of</strong> ancestors from elders who remember land-grabs<br />

<strong>of</strong> the past. we are helping to bring together a team<br />

and creating a vision <strong>of</strong> the future we want, sweating,<br />

A New Vision Held by Many<br />

Sasha vrtunski, ACIP, Project Manager, Asheville Downtown Master Plan<br />

THE TwiLigHT PrOJECT brought much-needed<br />

attention to painful memories and experiences that had<br />

been left out <strong>of</strong> our common history. it cannot be coincidence<br />

that now we have a lot <strong>of</strong> energy — multiple<br />

groups and individuals — working towards improving<br />

the East End neighborhood area.<br />

There now seems to be a new vision held by many <strong>of</strong><br />

strengthening the bonds <strong>of</strong> neighborhood residents,<br />

stemming the tide <strong>of</strong> gentrification, and re-connecting<br />

East End with downtown through beneficial new development<br />

along the Charlotte/valley St. corridor.<br />

praying, and dreaming again, maintaining our consistency,<br />

saying good-bye to comfort zones.<br />

The stimulus begins with us. in our attempt to restore<br />

a community that supports sustainability, we will<br />

need to include everyone. Low wealth communities<br />

will sit at the table as equals with all other citizens <strong>of</strong><br />

the city. By creating our own sustainable plan for the<br />

neighborhood, we’re protecting our community from<br />

the double-edged sword <strong>of</strong> development. we’re creating<br />

community programming for seniors and youth.<br />

we’re creating greenspace and backyard gardens.<br />

we envision a community business incubator and a<br />

community school, encouraging neighbors to join in.<br />

Historic Burton Street Agricultural<br />

Fair revived<br />

In another effort to restore community, Burton Street<br />

resident Mrs. Vivian Conley is leading an attempt to<br />

revive Mr. Pearson’s Agricultural Fair. “I saw our history<br />

and the old ways and the sense <strong>of</strong> community slipping<br />

away,” she says. Focusing on the fair’s emphasis on<br />

community and sustainable living, residents held a<br />

one-day mini-fair on September 25, 2009, building<br />

toward a centennial celebration in a few years.<br />

recovery comes through<br />

reclaiming history,<br />

restoring esteem, and<br />

redefining one’s participation<br />

in weaving<br />

the future. East End Rendering from Asheville Downtown<br />

residents are becoming Master Plan by Goody Clancy. Courtesy<br />

players in the creation City <strong>of</strong> Asheville, <strong>North</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>.<br />

<strong>of</strong> the new Asheville<br />

Downtown Master Plan. They are making manifest<br />

the community’s dream <strong>of</strong> a renewed and vital neighborhood<br />

true to its historic promise.<br />

CROSSROADS • Summer/Fall 2010 • 15

CROSSROADS • VOL. 14 • iSSuE 1 • 2010<br />

A PublicAtion <strong>of</strong> the north cArolinA humAnities council<br />

James Macon Barber Shop, 89 Eagle Street. James “Big Barber”<br />

Macon, Jr. Photo by Andrea Clark. Courtesy Andrea Clark<br />

Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library.<br />

The north <strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> <strong>Council</strong> serves as an advocate for lifelong<br />

learning and thoughtful dialogue about all facets <strong>of</strong> human life. It facilitates<br />

the exploration and celebration <strong>of</strong> the many voices and stories <strong>of</strong> north<br />

<strong>Carolina</strong>’s cultures and heritage. The north <strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

is a statewide nonpr<strong>of</strong>it and affiliate <strong>of</strong> the national Endowment for the<br />

<strong>Humanities</strong>.<br />

122 north Elm Street, Suite 601, greensboro, nC 27401<br />

COmmUNITY reSOUrCeS<br />

East End/Valley Street<br />

neighborhood Association<br />

renee white, President<br />

reneew1107@yahoo.com<br />

Burton Street<br />

Community Association<br />

Dewayne Barton, President<br />

(828) 275-5305<br />

Southside neighborhood<br />

Association<br />

Mr. robert Hardy<br />

(828) 251-0485<br />

Stumptown<br />

neighborhood Association<br />

Mrs. Clara Jeter, President<br />

(828) 258-9474<br />

Stephens-lee<br />

Alumni Association<br />

PO Box 105<br />

Asheville, nC 28802<br />

YmI Cultural Center<br />

39 S. Market Street<br />

Asheville, nC 28801<br />

(828) 252-4614<br />

www.ymicc.org<br />

The urban news<br />

(828) 253-5585<br />

www.theurbannews.com<br />

Eagle/market Streets<br />

Development Corporation<br />

70 S. Market Street<br />

(828) 281-1227<br />

Asheville GO<br />

(Green Opportunities)<br />

(828) 398-4158<br />

Center for Diversity Education<br />

114A Highsmith Student Union<br />

University Drive<br />

Asheville, nC 28804<br />

(828) 250-5024<br />

mountain Housing<br />

Opportunities<br />

64 Clingman Ave., Suite 101<br />

Asheville, nC 28801<br />

(828) 254-4030<br />

info@mountainhousing.org<br />

pack memorial library<br />

north <strong>Carolina</strong> Collection<br />

(828) 250-4740<br />

www.buncombecounty.org<br />

D. Hiden ramsey library<br />

Special Collections unC<br />

Asheville<br />

(828) 251-6645<br />

www.lib.unca.edu/library<br />

City <strong>of</strong> Asheville Office <strong>of</strong><br />

Economic Development<br />

Downtown master plan<br />

Project Manager Sasha<br />

vrtunski<br />

(828) 232-4599<br />

Asheville Design Center<br />

8 College St.<br />

Asheville, nC 28801<br />

(828) 337-6927<br />

www.ashevilledesigncenter.org<br />

MANY STORIES, ONE PEOPLE<br />

www.nchumanities.org