PDF (5.6 Mb) - ENAC - EPFL

PDF (5.6 Mb) - ENAC - EPFL

PDF (5.6 Mb) - ENAC - EPFL

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Executive Summary<br />

Executive Summary<br />

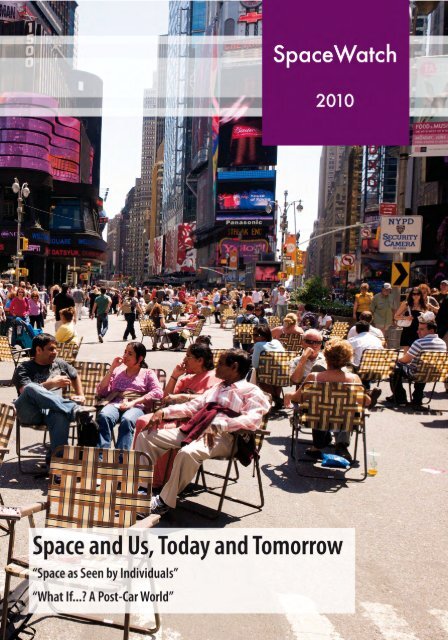

Mobility and places, that is, inhabited space, raises major political issues. With the<br />

ambitious title “Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow”, the SpaceWatch workshop 2010<br />

proposed to discuss the Swiss space in the form of a think tank, gathering together<br />

a panel of Swiss and European experts. The uniqueness of SpaceWatch resides in its<br />

total independence from political and institutional power. The think-tank allocates an<br />

unusually long time for reflexion and assumes the existence of controversies without<br />

asking the participants to produce an univocal conclusion at the end of the process.<br />

Two very strongly interrelated topics were retained for this edition in order to explore<br />

Swiss territorial issues. The first one, “Space as Seen by Individuals” is an invitation to<br />

tackle the way new players of space see their living environment. The second theme<br />

proposes a more hypothetic and provocative approach towards mobility, with the<br />

statement: “What if… ? A Post-Car World ?”. Setting the debate around concrete issues<br />

concerning the future of the territory not only enables an identification of emerging<br />

trends but also an analysis of the present state of mobility through the consideration<br />

of utopian schemes.<br />

This publication presents the main results of the workshop in the form of scientific<br />

statements and research questions, each topic being preceded by a collection<br />

of commented texts, which were used as background papers for the workshop. The<br />

phenomenon of urban sprawl and its correlation with individual motorized traffic is<br />

considered to be one of the most urgent issues to be resolved, and therefore must<br />

first be understood through research, notably from the angle of the actors of the territory.<br />

The workshop highlighted moreover that more knowledge transfer between<br />

research institutions and public bodies able to intervene in space, as well as between<br />

the linguistic regions of Switzerland are necessary. In addition, the scientist’s and the<br />

citizens’ roles as well as the notion of governance more generally need to be redefined.<br />

The model of sustainability proposed for the Swiss space can be summarized by<br />

the notion of urbanity, understood as the arrangement of density, diversity, public<br />

space and public mobility. At last, coherence between legal instruments and public<br />

policies must be improved. The second chapter tackles the question of the post-car<br />

city. Car culture, possible alternatives to the current mobility model, individualisation<br />

of public transport and the opposition between the car-city and the slow-city are<br />

addressed. In conclusion, the participants to the workshop take a critical look at the<br />

Swiss transportation policy.<br />

The Board of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH Board) has mandated<br />

four scientists to define the crucial research questions in the spatial sciences. In order<br />

to fulfil this mission, the four scientists created the Swiss Spatial Sciences Framework<br />

[1]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

(S3F). SpaceWatch 2010 is part of a coordinated event supported by S3F. As a member<br />

of the S3F steering committee, Prof. Jacques Lévy (<strong>EPFL</strong> - INTER, Laboratoire Chôros)<br />

directed the SpaceWatch Workshop as the contribution of <strong>EPFL</strong> to the Framework.<br />

Besides the four members of the steering committee, 10 internationally-known experts<br />

took part to the three-days workshop. A public debate drew 70 people on February<br />

10 th for the presentation of the conclusion to the discussions.<br />

www.s3f.ch http://spacewatch.epfl.ch<br />

[2]

I.<br />

Space and Us<br />

Today and Tommorrow

Table of Contents<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Foreword: a Discussion Kick-Off 6<br />

SpaceWatch 2010: Participants and Programme 10<br />

I. Territorial Awareness of Swiss and European Contexts 13<br />

1. Overview of Urban in Switzerland 14<br />

2. Switzerland and its Urban Scales 22<br />

3. Which Future is Best for Swiss Spatial Development? 34<br />

4. Regional Governance in Switzerland: Basel, Zurich and Leman Example 37<br />

Two Approaches to Address Swiss Space 43<br />

“Urbanity ” as a Concept for Swiss Spatial Development 43<br />

Time Management as a Tool for Swiss Spatial Development 50<br />

II. “Space as Seen by Individuals” 55<br />

1. Questions about Space from the Viewpoint of the Individual 56<br />

2. How Could we Put Ourselves into the Shoes of Swiss Urban Dwellers? 57<br />

3. Some Facts about Urban Sprawl and the Housing Model in Switzerland 59<br />

4. What are Citizens’ Views about Spatial Planning? 65<br />

5. Single-Detached Housing Market 68<br />

6. Dependency on Individual Motor Vehicles 71<br />

7. How Does one Cope with the Contradiction between the Dispersed Urban<br />

Development and the Desire for Densification? 77<br />

8. Why Thinking about a “CitizenSpace”? 99<br />

Statements and Questions on “Space as Seen by Individuals” from the<br />

SpaceWatch 2010 Workshop 108<br />

III. “What if … ? A Post-Car World ?” 113<br />

1. Imagine a City with no Cars 114<br />

2. De-Privatizing Vehicles 117<br />

3. New Transportation Policies 122<br />

4.New living, Work, Leisure, Practices 128<br />

5. “Disruptive“ Innovation 135<br />

6. Summary 136<br />

Statements and Questions on “The Hypothesis of a Post-Car World”<br />

from the SpaceWatch 2010 Workshop 142<br />

Participants Biographies 146<br />

Bibliography 150<br />

[5]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

[6]<br />

Foreword<br />

A Discussion Kick-Off<br />

Some short news from Switzerland: space is central in several major public debates.<br />

If we focus on mobility issues, we can see a very controversial public debate at the<br />

federal scale, about road and rail financing and pricing.<br />

About mobility, we are observing a fierce fight in Geneva on public and private transportation.<br />

The November 29th , 2009 referendum on the construction of a metropolitan<br />

railway called CEVA is a good example. ”Nous vivons ensemble, nous bougeons ensemble”<br />

(”We live together, we move together”), a pro-CEVA has proclaimed, but not<br />

everybody agrees on this and two populist movements UDC and MCG have gather<br />

a quarter of the Canton’s electorate thanks to tough mottos against the Annemasse<br />

“caillera” , that is the young mob coming from the French neighbouring area.<br />

An emerging debate is stirring the issue of whether or not the Swiss constitution<br />

guarantees an equal accessibility by car and public transportation, or, in another formulation,<br />

whether or not “liberalism” means free choice of the transport mode. The<br />

same day, a referendum in another canton, Obwald, had addressed the issue of a<br />

new “high quality” neighbourhood, some observers have called “gated community”<br />

or future ”ghetto for the rich people”.<br />

More generally, debates on urban models (for instance between that of ”gathered<br />

city” and that of ”sprawled and fragmented urban society”) immediately generate intense<br />

social and political arguments. Urban policies and territorial development have<br />

therefore currently become one of the most controversial issues on the Swiss political<br />

scene. As soon as issues such as agglomération policy, road pricing, or industrial<br />

brownfields are raised, the usual Swiss consensus vanishes. Many stakeholders and<br />

powerful lobbyists consider oil taxes on cars not as taxes but as a fee to maintain a<br />

good, the roads, that belong to them, as a shared good, common to all drivers. This<br />

is clearly at odds with another conception, seeing infrastructures as a public good,<br />

belonging to the society as a whole and that would be lent (or let) to users, supposed<br />

to pay, in return, a tax which goes down into the general public budget and, as such,<br />

entails no predetermined use.

Foreword<br />

Thus, mobility and places, that is inhabited space, raises major issues in politics and<br />

political philosophy. The current dilemma of whether to allow urban sprawl to continue<br />

or instead to face up to the challenges of dense and diverse urbanity illustrates<br />

the difficulty where our society remains hesitating on its choice between two or more<br />

incompatible approaches each of them supposed to make space liveable. The principles<br />

of spatial development appear to be trapped in a twilight zone, in which the<br />

experts’ informed but often-diverging views do not always coincide with ordinary<br />

citizens’ views that are themselves divided into opposite paradigms. As long as this<br />

confusion remains, spatial development will continue to be the Achilles’ heel of sustainable<br />

development, as we said in SpaceWatch 2008 report.<br />

SpaceWatch project approach – A scientific think tank on spatial development<br />

The main goal of SpaceWatch is to create a limited-access workshop, open to a small<br />

number of Swiss and foreign participants with practical as well as theoretical professional<br />

orientations. This scientific think tank on spatial development has been set<br />

up to be totally independent from any lobby or political power and to select people<br />

that would accept to develop free scientific thought on issues that may be highly<br />

controversial within social and political life. The uniqueness of SpaceWatch resides in<br />

the challenge of exploring a specific, and dangerous, area: the very meeting air-lock<br />

between two fields, that are supposed to be separated by their rationales: scientific<br />

construction of refutable statements and controversial debates on the public stage.<br />

This supposes a clear commitment from the participants and the acceptance that since<br />

we cannot completely eliminate the porosity between the scientist and the citizen,<br />

it is better to admit it and to explicit values and political choices that may underpin<br />

academic statements.<br />

A contribution to the Swiss Spatial Sciences Framework (S3F)<br />

The first edition of SpaceWatch (May 2008) generated 8 proposals, notably based on<br />

a substantial Swiss press review. Some of them were consensual, others, less, for instance<br />

on mobility. Background information of the first edition and the book “1m2 /second”<br />

containing the results of SpaceWatch 2008 are available on http://spacewatch.<br />

epfl.ch. The advantage of the trilogy of events (Zurich, Lausanne, Bern) being organized<br />

by the Swiss Spatial Sciences Framework (S3F) in 2009-10 is that they will combine<br />

two complementary working methodologies in order to provide a full response<br />

to the question posed by the ETH Board. As a matter of fact, the question the S3F<br />

Steering committee is supposed to fulfil the ETH Board’s expectations, and beyond,<br />

of the Swill Federal Parliament’s concerns, is: ”What are the crucial research questions<br />

concerning spatial sciences in Switzerland and in Europe?” The SpaceWatch concept<br />

is perfectly in line with this issue. That is why we decided to integrate the project<br />

into the S3F scheme and to use it as the second encounter of the S3F trilogy. The<br />

SpaceWatch project aims to take advantage of the critical spirit prevailing in the academic<br />

context. It has therefore gathered excellent specialists who keep off the Swiss<br />

political decision-making processes, but who are willing to play an important civic<br />

role in considering society’s needs in connection with inhabited space.<br />

[7]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

SpaceWatch 2010 - A three-day workshop concluded by a public debate<br />

The second edition of the SpaceWatch project, which has been organised with the<br />

collaboration of the <strong>EPFL</strong>’s Institute of Urban and Regional Sciences will focus on the<br />

interface between research supply and political demand, which was the very starting<br />

point for the S3F process.<br />

SpaceWatch aims at formulating statements concerning spatial development in Switzerland<br />

and Europe. On the one hand, the discussions will enable experts to formulate<br />

future research projects in the field of spatial sciences. On the other hand, in order<br />

to build a bridge between academic expertise and society, the workshop also led to<br />

more societal oriented recommendations. The SpaceWatch workshop provided an<br />

opportunity to develop proposals for strengthening and improving educational and<br />

research structures in this field.<br />

The programme for SpaceWatch 2010 features two specific topics, which are in the<br />

continuation of those raised at the 2008 event. These topics have been addressed<br />

during significantly long sessions of free discussion.<br />

The first one is “Space as Seen by Individuals”, followed by “What if...? A Post-Car World”.<br />

These two topics are strongly interrelated, since acting on the first one will produce<br />

changes in the other. This document provides a common information base regarding<br />

spatial development today in Switzerland, along with introductory materials on the<br />

two specific topics selected for discussion.<br />

This collection of articles has been derived from many sources and does by no means<br />

claim for exhaustiveness. It merely served to offer a few relevant and divergent reflections<br />

on the topics to be discussed during SpaceWatch workshop. Attention has been<br />

given to maintaining a balance between academic information and the social debate<br />

on spatial development. The articles, which are briefly commented along the file, may<br />

be drawn equally from the academic literature (e.g. reviews and books), from official<br />

documents and statistics, or from informal sources such as newspapers. Best-practice<br />

examples are also mentioned.<br />

Final statements of the workshop, which may be either consensual or controversial,<br />

have been briefly presented at a public event in the presence of the workshop participants<br />

on February 10th 2010. In case of controversy, the defenders were able to elaborate<br />

their views. We do prefer argued controversies to feeble, corny consensuses<br />

because we simply think they are better tools for knowledge-building and decision<br />

making.<br />

Spatial planning as a matter for society<br />

In social worlds, the distance between theory and practice is small. In urbanism, observation<br />

is a crucial part of action. Spatial planning was a matter for planners as spatial<br />

development is a matter for society with all its actors. In the ideal, spatial sciences<br />

and spatial engineering should be separated only by provisional differences of workstyle,<br />

rather than by fundamental disciplinary oppositions. In this prospect, we would<br />

modestly like to help scholars to participate in “hybrid forums”, which are based on<br />

[8]

Foreword<br />

the idea that everybody takes on one’s part, without confusion des genres and role<br />

mix. In such configurations, nobody is lead to anticipate too much, to interiorise too<br />

soon a future compromise. Doing so, we keep in mind both the efficiency of academic<br />

research and quality of the public debate.<br />

With this document, we hope to contribute efficiently to the general objectives of S3F<br />

and beyond to a better quality of both scientific achievements and public awareness<br />

on spatial issues.<br />

Jacques Lévy<br />

[9]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

SpaceWatch 2010: Participants and Programme<br />

Steering Committee of the Swiss Spatial Sciences Framework (S3F)<br />

The task of the S3F steering committee was to define major research aims for the future in the<br />

field of the spatial sciences in Switzerland, in both the national and the international contexts.<br />

Its purpose was to establish targeted and intensive networking of university, political/administrative,<br />

and private-enterprise bodies, as well as to achieve substantial improvements in university<br />

training courses. It had therefore to make a contribution to providing the essential and<br />

innovative stimuli needed for political bodies and for society in general in connection with the<br />

spatial sciences in Switzerland, notably through recommendations.<br />

[10]<br />

Prof. Dr. Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, ETH Zurich (head of the working group; Network<br />

City and Landscape / NSL)<br />

Prof. Dr. Jacques Lévy, <strong>EPFL</strong> (Institute of Urban and Regional Sciences / INTER)<br />

Prof. Dr. Bernd Scholl, ETH Zurich (NSL)<br />

Dr. Silvia Tobias, WSL<br />

The S3F independent scientific committee present at all events of S3F took part to the workshop<br />

discussion.<br />

Dr. Fran Tonkiss: urban and economic sociologist; London School of Economics and Political<br />

Science, Department of Sociology, United Kingdom<br />

Dr. Katharina Helming: landscape researcher / ecologist; Leibniz Centre for Agricultural<br />

Landscape Research (ZALF), directorate, Germany<br />

Prof. Michel Lussault: Geographer, President of the University of Lyon / Ecole normale supérieure<br />

de Lyon and Professor, France<br />

Prof. Bernardo Secchi: University IUAV of Venice, Faculty of Architecture, Italy<br />

Prof. Dr. Max van den Berg: Consultant and Advisor Spatial Planning, Croonen Adviseurs;<br />

former Professor for spatial planning at TU Utrecht, chief planner Randstad NL, former President<br />

of ISOCARP – International Society of City and Regional Planners, the Netherlands<br />

Experts for SpaceWatch 2010, Lausanne<br />

The experts present at the SpaceWatch workshop uniquely were present during the three days<br />

of reflexion and at the public debate.<br />

Dr. Xavier Comtesse, Avenir Suisse, Switzerland<br />

François Grether, Urbanist, Francois Grether Urbaniste, Paris, France<br />

Dr. Luca Pattaroni, Urban Sociology Laboratory, PhD in sociology, <strong>EPFL</strong> INTER LASUR, Switzerland<br />

Prof. Martin Schuler, Urban and Regional Planning Community, <strong>EPFL</strong> INTER CEAT, Switzerland<br />

Prof. Ola Söderström, Université de Neuchâtel, Institut de géographie, Switzerland

Public Debate 10 February 2010, 16.45 - 19.00<br />

Participants and Programme<br />

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne <strong>EPFL</strong><br />

Language: English and French<br />

Participants: academic and professional scholars, politicians, representative of public authorities<br />

and any interested person.<br />

Public presentation and discussion of the recommendations issued from the 3 days workshop in<br />

presence of S3F Scientific Committee, Lausanne Experts Group and S3F Steering Committee.<br />

The main goal of the symposia in Lausanne was to formulate scientific statements concerning<br />

spatial development in Switzerland and in Europe. As a result of this, the S3F scientific committee<br />

and experts invited for the Lausanne event drew up a list of recommendations, as well<br />

as proposals for research projects. Academic observations has been brought into the public<br />

debate through the public discussion organised at the end of the three days.<br />

Programme<br />

16:45 Welcome<br />

17:00 Opening by Prof. Giorgio Margaritondo, <strong>EPFL</strong> Vice president for academic affairs<br />

Presentation of the workshop’s results and debate<br />

Stakeholders: Dr Silvia Tobias, Prof., Michel Lussault, Ola Söderström and Jacques Lévy<br />

Animated by Richard Quincerot<br />

17:10 I Crucial research questions in spatial sciences<br />

17:35 II “Space as Seen by Individuals”<br />

18:00 III “What if...? A Post-Car World”<br />

18:25 IV Education and research structures<br />

18:50 Closing remarks and next steps by Maria Lezzi, ARE director<br />

19:00 Aperitif<br />

[11]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

1. Overview of Urban in Switzerland<br />

[14]<br />

[?]<br />

Is Switzerland rural? Urban? Peri-urban? Fully urban?<br />

Which place are qualified as “spaces“ in the study of urbanity in Switzerland?<br />

Before deepening the particular themes proposed in the two following chapters (II.<br />

“Space as Seen by Individuals”, III. “What If...? A Post-Car World”), this introduction<br />

presents recent information concerning current spatial development in Switzerland,<br />

and Europe more generally. A selection of maps accompanied by reproductions of<br />

relevant articles will notably tackle two major tendencies, which constitute the paradox<br />

of urban sprawl: the dispersion of urban settlement and the metropolisation<br />

process 1 .<br />

Let us start with a general overview of the Swiss urban context. Several maps collected<br />

here present the current state of urbanisation: land use, agglomerations and<br />

density of constructed space. Special importance is given to metropolitan areas. According<br />

to experts, Switzerland contains one to five metropolises, as the present selection<br />

of maps illustrates. Lastly, Switzerland’s position in Europe -politically not part<br />

of Europe while economically fully integrated into the European exchanges market-<br />

will be shortly discussed.<br />

Map by OFS: Ground use in Switzerland<br />

As a reminder, the entire Swiss housing and infrastructure space constitutes only<br />

about 7% of the territory 2 , while the remainder is covered by alpine territory, forest<br />

and water surfaces.<br />

Most of the country’s settlements are situated on the West-East Plateau on the north<br />

side of the Alpine chain and in the valleys of Valais and Ticino Cantons as the following<br />

map 3 indicates.<br />

1 Lévy, J. (Ed.) (2008) L’invention du Monde. Une géographie de la mondialisation, Paris, Presses<br />

de Sciences Po.<br />

2 Morgenthaler, B. & A. Grossenbacher (2009) Mémento statistique de la Suisse 2009, Neuchâtel,<br />

Office fédéral de la Statistique: 50.<br />

3 Office fédéral de la statistique (2004) Statistique de la superficie 1992/97. Neuchâtel, Office<br />

fédéral de la statistique.

Map by CEAT: Functions distribution<br />

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

This map 4 by CEAT laboratory shows the repartition between central, peri-rural and<br />

tourist regions. It illustrates how municipalities are losing or gaining density. While<br />

the densification process can be observed on the Geneva Lakeside in the newly built<br />

areas, industrial cities like Neuchâtel or cities in Jura, as well as rural villages, are losing<br />

inhabitants either because they are spreading out in the new suburban constructions<br />

or because of the “flight” of their inhabitants to other cities.<br />

The use of the adjective “rural” is nevertheless debatable. While the authors of this<br />

map consider this typology relevant to give an account of Swiss urbanisation, others 5<br />

would affirm that there is no longer any rural space in Switzerland. An argument for<br />

this is that the amount of commuters between countryside and city is increasing significantly.<br />

Official statistics also establish that “Les interdépendances entre la ville et<br />

la campagne, principalement en matière de mouvements pendulaires, augmentent de<br />

manière significative.” 6<br />

Map by OFS: Densification of built space between 1981 and 2005<br />

While certain regions are gaining density, others are getting emptier, as the following<br />

map 7 illustrates, only for the French speaking part of Switzerland. The most attractive<br />

poles of the considered area are the coast of Geneva Lake, especially the agglomeration<br />

of Geneva and the entire Vaud Canton. Areas losing density are the Jura mountain<br />

range and the regions of Bern and Fribourg.<br />

Is sw It z e r l a n d u r b a n o r r u r a l?<br />

The fact that 80% of the Swiss population today lives in urban areas (as opposed to<br />

rural areas) allows us to assume that the country is fully urban. This is the conclusion<br />

of a federal report 8 and that of two recent publications: ”Switzerland: An Urban<br />

Portrait”, by Studio Basel 20005 and “Le feu au lac – Vers une région métropolitaine<br />

lémanique” by Avenir Suisse 2006. Architects Pierre Feddersen and Richard Quincerot<br />

assume in “Le feu au lac” that the country is peri-urban and a tourist attraction but no<br />

longer rural and talk about a “metropolitan countryside” (campagne métropolitaine).<br />

4 Schuler, M., P. Dessemontet, & al. (2007). Atlas des mutations spatiales de la Suisse. Zurich, Editions<br />

Neue Zürcher Zeitung.<br />

5 Cf. Switzerland: Urban Portrait by ETH Studio Basel, page 178.<br />

6 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l'espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

7 Dessemontet, P., A. Jarne & M. Schuler (2009) "Suisse romande, les facettes d’une région affirmée",<br />

Forum des 100 - édition 2009: 28.<br />

8 Office fédéral du développement territorial (2006) Rapport 2005 sur le développement territorial,<br />

Berne, Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

[15]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Other authors maintain the distinction between urban and rural. C.E.A.T. research<br />

group 9 explains for example in its map focusing on the French-speaking part of the<br />

country (cf. page 22) that, while urban areas are getting denser, rural ones are sprawling.<br />

Disagreement exists about this urban/ rural distinction, but at least urbanity is now<br />

recognised by the highest Swiss authorities. It is only since the last revision of the<br />

Swiss Constitution in 1999 that cities and urban areas gained recognition in a federal<br />

document. Even though paragraph 3 was added to the old article dealing with municipalities,<br />

the urban process is now at least taken into account in the Constitution.<br />

A rural image still marks the Swiss state, which constitutes a major and tenacious<br />

obstacle to the metropolisation process.<br />

Article 50 of Swiss Constitution (1999) Section 3: Communes<br />

Art. 50<br />

1 The autonomy of the communes shall be guaranteed in accordance with cantonal law.<br />

2 The Confederation shall take account in its activities of the possible consequences for<br />

the communes.<br />

3 In doing so, it shall take account of the special position of the cities and urban areas as<br />

well as the mountain regions.<br />

Is sw It z e r l a n d a c o u n t r y o f c o m m u t e r s ?<br />

The quantity of commuters is another indicator to study the character of metropolitan<br />

cities. Yet Switzerland is witnessing an increasing amount of commuters 10<br />

, from<br />

greater distances. First inter-municipal, then inter-cantonal and then international, in<br />

the different bi- or tri- national metropolises which now exist. The graphics below 11<br />

also illustrate that most commuters are moving into the agglomeration.<br />

9 Dessemontet, P., A. Jarne, & al. (2009) "Suisse romande, les facettes d’une région affirmée", Forum<br />

des 100 - édition 2009: 28, Schuler, M., P. Dessemontet, and al. (2007). Atlas des mutations spatiales<br />

de la Suisse, Zurich, Editions Neue Zürcher Zeitung.<br />

10 Schuler, M., P. Dessemontet, & al. (2007) Atlas des mutations spatiales de la Suisse, Zurich, Editions<br />

Neue Zürcher Zeitung.<br />

11 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l'espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

[19]

Map by CEAT:<br />

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Commuter Movement between Swiss Agglomerations<br />

“La part des personnes actives dont le lieu de travail ne se situe pas dans la commune<br />

de domicile a passé de 41 pour cent en 1980 à 57 pour cent en 2000 en Suisse. Cette<br />

proportion est plus ou moins la même dans l’espace urbain et l’espace rural.”<br />

Figure 5 Commuters statistics 1990-2000 and dwelling repartition per<br />

housing type 2000, Swiss Federal Sensus, by ARE<br />

[21]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

2. Switzerland and its Urban Scales<br />

[22]<br />

[?]<br />

What is the right governance scale for metropolitan spaces in<br />

a federal system based on the brick of municipalities?<br />

How is it possible to fix cities’ borders for<br />

agglomerations that may be tri-national?<br />

Which role do Swiss cities have to play in the European network of<br />

cities, in a country economically integrated, but politically isolated?<br />

munIcIpalItIes a t Issue<br />

How can Switzerland fully integrate its urban scale?<br />

The municipalities' administrative entity is questioned in this article published by<br />

ETH Studio Basel 12 . Although forming a strong bases for Swiss federalism, municipalities<br />

do not seem to be the appropriate building blocks for the future. Switzerland<br />

differs from most of European countries through its tradition of the reconciliation<br />

of differences (linguistic, cultural, political, topographical) and its managerial habits<br />

regarding the borders between these differences. This tradition became such a Swiss<br />

speciality that today the country is no longer able to deal with real differences such<br />

as urban culture. “Finalement les Suisses ne veulent ni la nature ni la ville, mais un peu<br />

des deux et aucun en particulier.” 13<br />

According to Herzog and Meili, the strategy to adopt for Switzerland is not to concentrate<br />

on a unique pole, but to enforce the different existing poles. However, federalist<br />

and egalitarian tradition ensuring the same rights and opportunities for each location<br />

stands in the way of any process for change. “Le fédéralisme helvétique suisse agit<br />

à l’encontre d’une métropolisation dynamique”. 14<br />

Nevertheless, to achieve any change in municipalities, it would be necessary to set up<br />

a solidarity dynamic and to accept that some regions share the costs and benefits of<br />

strong and weak sectors with other regions. In order to effect a real change towards<br />

12 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Introduction. Basel, Birkhäuser<br />

- Verlag AG.<br />

13 Ibid.<br />

14 Ibid.

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

metropolisation, it would be necessary to set up a decision mechanism covering<br />

considerably larger spaces. The authors doubt the capacity of the Swiss to learn this<br />

solidarity, as well as to establish decision organs at a higher scale than the current<br />

one of the municipalities. This is however the case in the tri-national metropolitan<br />

region of Basel, as is mentioned by the authors themselves 15 . Since the publication<br />

of the book, the area of Zurich has also equipped itself with a new metropolitan government.<br />

[24]<br />

sw Is s a g g l o m e r a t Io n s<br />

In Switzerland, a settlement is considered to be a city of over 10 000 inhabitants 16<br />

while the official definition of an agglomeration in Switzerland according to the Federal<br />

office of territorial development (ARE) mentions 20 000 inhabitants 17 . The ARE<br />

specifies several conditions for municipalities adjacent to core cities to belong to the<br />

agglomeration:<br />

The above anamorphosis map by Chôros Laboratory (<strong>EPFL</strong>) 18 indicates the weight of<br />

Municipalities according to their population. The result differs a lot from the previous<br />

map and enables a new understanding of Swiss urban spaces. Switzerland today<br />

has five agglomerations: Zürich 19 (1 132 000 inhabitants), Geneva (503 600), Basel<br />

(489 000), Bern (346 000), Lausanne (317 000) and Lugano (56 000). According to the<br />

authors, Geneva and Lausanne are considered either as one single agglomeration or<br />

separately.<br />

It’s t Im e f o r t h e sw Is s me t r o p o l Is!<br />

The point here is not to decide the number of metropolitan areas in Switzerland, but<br />

rather to stress the reality of this urban phenomenon. Considering this new scale<br />

of reflection, the debate on the relevance of the municipality today deserves to be<br />

addressed.<br />

15 Three Cross-border Metropolitan Regions. Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An<br />

Urban Portrait, Introduction, Basel, Birkhäuser - Verlag AG.<br />

16 Office Fédéral de la statistique (2009) Nomenclatures - Agglomérations et villes isolées.<br />

17 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l'espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial. (Base definition in ARE Glossaire http://<br />

www.are.admin.ch)<br />

18 Schuler, M., P. Dessemontet, & al. (2007) Atlas des mutations spatiales de la Suisse, Zurich, Editions<br />

Neue Zürcher Zeitung.<br />

19 Morgenthaler, B. & Grossenbacher A. (2009) Mémeno statistique de la Suisse 2009, Neuchâtel,<br />

Office fédéral de la Statistqiue: 50, data 2007 and for Lugano, Avenir Suise (2005) La nouvelle<br />

Lugano, Baustelle Föderalismus, Blöchliger H. & Schneider M., Basel, NZZ Libro: 416.

ARE Agglomeration’s Definition<br />

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

L’agglomération est un ensemble d’au minimum 20 000 habitant-e-s, formé par la<br />

réunion des territoires de communes urbaines adjacentes. Elle se constitue d’une<br />

ville-centre et, suivant les cas, d’autres communes de la zone-centre, ainsi que d’autres<br />

communes qui ont un lien fonctionnel avec la ville-centre.<br />

Pour appartenir à une agglomération, les communes doivent remplir au moins trois des<br />

cinq conditions ci-après (compte tenu de valeurs seuils prédéfinies):<br />

- Lien de continuité avec la ville-centre de l’agglomération<br />

- Densité élevée de population et d’emplois<br />

- Évolution démographique supérieure à la moyenne<br />

- Secteur agricole peu développé<br />

- Interdépendance prononcée de pendulaires avec la ville-centre et, suivant les cas avec<br />

d’autres communes de la zone-centre. 1<br />

1 Office Fédéral de la Statistique (2009) Nomenclatures - Agglomérations et villes isolées.<br />

Switzerland: An Urban Portrait by ETH Studio Basel:<br />

The Municipality as a Basic Cell<br />

“The commune is the stem cell of Swiss urbanism” is one central theme of our book,<br />

although we are placing our bets more on increasing the existing urban potential than<br />

on outlining a number of these.<br />

Cities are not created equal; they differ from one another. Despite globalization, they are<br />

not becoming more similar but rather more autonomous. Now as ever, we are living on<br />

a planet that has different cultures, different people, different rhythms, different times,<br />

and specific forms of urbanism. In making this assertion we are contradicting many of<br />

the thinkers of our day, who increasingly negate concepts like reality or difference.” 1<br />

“Before we get into the commune itself, we should speak for a moment about difference<br />

as a feature of the urban. In our country, the commune is mainly responsible for<br />

difference. In principle, the question of difference is about the survival of identities in a<br />

situation of global urbanization.”<br />

“Such differences are both cause and effect of this country’s highly heterotopic structure<br />

(…). ” 2<br />

1 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Introduction. Basel, Birkhäuser<br />

- Verlag AG.<br />

2 Ibid.<br />

This second anamorphosis map by ETH Studio Basel 20 divides the Swiss territory into five<br />

categories: metropolitan regions, urban networks, quiet zones, alpine resorts and alpine<br />

brownfields. While agglomeration indicated on this map are practically the same as the<br />

20 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Introduction. Basel, Birkhäuser -<br />

Verlag AG.<br />

[25]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

ones identified by the Federal Statistics Office, the authors are aware of the controversial<br />

character of their other categories, especially concerning quiet zones and alpine<br />

resorts:<br />

[26]<br />

Map by ETH Studio Basel, Urban Switzerland Typology<br />

This map shows well that municipal, cantonal and even national borders are somewhat<br />

out of date, as metropolitan and urban networks form according to a logic<br />

that does not care about administrative borders. In ETH Studio's vision, there are two<br />

metropolises: Geneva-Lausanne, and Zurich, extending from Lake Constance to the<br />

Basel agglomeration, while Ticino is attached to the Italian metropolis of Milan. Several<br />

agglomerations are indeed transnational: Geneva, Basel, Ticino and cities around<br />

Lake Constance. All areas, except the pink and orange ones, are supposed to develop<br />

weakly in the future, or only through tourism, which of course is not easy for local<br />

governments to address. Lastly, the authors stress that the Swiss federalist system<br />

acts against a dynamic metropolisation process.<br />

The next map by Alain Thierstein 21 even suggests a Switzerland made of two metropolises:<br />

Geneva Lakeside and Zurich area, other metropolitan spaces being added to<br />

one of these two.<br />

“Le livre a été controversé à sa sortie. L’expression de “friche alpine” a notamment<br />

suscité de vives réactions et de vives critiques dans les régions concernées. Les auteurs<br />

constatent que de nombreuses régions alpines continuent de se dépeupler malgré les<br />

aides financières qui leur sont accordées, et ils souhaiteraient qu’il soit pris acte de<br />

cette réalité. L’expression de “friche alpine” a été employée pour provoquer le débat sur<br />

les enjeux que sont le devenir de l’agriculture, la capacité de réforme, les modèles de<br />

subventionnement et le tourisme.” 1<br />

1 Comment on http://www.nb.admin.ch<br />

sw It z e r l a n d – eu r o p e, InclusIon o r e x c l u s Io n?<br />

Do all these refusals to participate in international organisations make Switzerland a<br />

hole? With four linguistic regions, 23 cantons, six half-cantons, and 2768 communes<br />

(in 2005) is Switzerland an island? Those provocative questions by ETH Studio Basel<br />

sum up how the Swiss State avoids taking part in international or European political<br />

and economical structures. In the meanwhile, the Swiss economy is fully a part of the<br />

21 Thierstein, A., L. Glanzmann, & al. (2006) European Metropolitan Region Northern Switzerland:<br />

Driving Agents for Spatial Development and Governance Responses. The Polycentric Metropolis.<br />

Learning from mega-city in Europe, P. Hall and K. Pain, London, Earthscan, 172-179.

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

European exchange system and cities appear to be competitive according to several<br />

rankings, as outlined by the following quote from the Swiss Monitoring unit of urban<br />

space.<br />

Switzerland: An Urban Portrait by ETH Studio Basel:<br />

Agglomeration, Metropolises and Network of Cities<br />

“The most important criterion for demarcation is the coherence of the agglomeration<br />

areas that can be reached within an hour’s drive of Zurich’s city centre. One consideration<br />

is clearly the belief that only regions of this size can compete internationally. But there<br />

are still no detailed studies that could provide additional arguments for this thesis.<br />

Our analysis has identified three regions in Switzerland that fulfil the conditions for<br />

metropolitan regions, at least in part: Zurich, the bipolar Lake Geneva region, and the<br />

trinational region Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg.”<br />

“The three metropolitan regions of Switzerland have very different economic<br />

specializations, and correspondingly distinct positions and characteristics. Although<br />

there are many contacts and interconnections between them, strong synergies and<br />

complementarities are not evident. The dynamics of evolution in the three regions<br />

are different and do not appear to be synchronized. Even the regional constitution of<br />

the three areas is quite distinct. The criterion of strong and progressing specialization<br />

was another crucial factor in our decision to continue to regard the Zurich and Basel-<br />

Mulhouse-Freiburg regions as two separate entities. There are many connections between<br />

the two regions, and their commuter areas are increasingly growing together, with their<br />

edges starting to overlap. Nevertheless, the differences in culture and in economic and<br />

everyday orientation make them two clearly distinct units - even more so than either<br />

their topographical separation by the Jura mountain chain or their still pronounced<br />

tendency to distinguish between themselves.”<br />

“Networks of cities consist of converging small and medium-sized cities that lie outside<br />

metropolitan regions. They can take on very different forms and characteristics. The<br />

cities have strong economic, cultural, and social interconnections based on horizontal<br />

relationships.” 1<br />

1 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Introduction, Basel, Birkhäuser<br />

- Verlag AG.<br />

Spaces with more than 20 000 inhabitants are shown on the following map 22 . According<br />

to these categories, Switzerland has no city over five million people unlike London,<br />

Paris or Madrid. Zurich is the only million-strong agglomeration, and although<br />

we can observe an important concentration of cities with 250 000 to 1 million inhabitants,<br />

it is not even shown on this map. Compared with other European regions, a<br />

large number of Swiss cities between 50 000 and 250 000 are located very close to<br />

bigger urban poles.<br />

22 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l'espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

[28]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Figure 8 Two Swiss metropolitan regions, European metropolitan region Northern<br />

Switzerland, The polycentric metropolis, Thierstein, 2006<br />

[29]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

Switzerland: An Urban Portrait by ETH Studio Basel:<br />

Is Switzerland a Hole? Is Switzerland an Island?<br />

Switzerland has been a member of UNO only since 2002.<br />

Switzerland is not a member of NATO.<br />

Switzerland is not a member of the European Union.<br />

Switzerland is not part of the Euro Zone.<br />

Is Switzerland a hole? 1<br />

1 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Introduction. Basel, Birkhäuser<br />

- Verlag AG.<br />

“Les villes suisses forment un réseau dense de grands, moyens et petits centres, dont les<br />

fonctions principales se complètent partiellement.<br />

Les grandes agglomérations jouent un rôle essentiel de “portes sur le monde”. Elles<br />

remplissent de plus des fonctions spécifiques de centres de services pour les autres<br />

régions et pour les petits et moyens centres de leur aire d’influence respective.<br />

Dans les domaines fonctionnels qui requièrent une proximité géographique avec<br />

l’économie locale et avec les ménages privés (p. ex. fonction d’approvisionnement,<br />

administrations cantonales), les petites et les moyennes agglomérations jouent un rôle de<br />

centre important pour leurs aires d’influence respectives. Cet effet est particulièrement<br />

sensible dans les agglomérations de l’espace alpin, situées à une grande distance des plus<br />

grandes agglomérations (p. ex. Davos, Saint-Moritz).” 1<br />

1 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l’espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

Two models can be distinguished in Europe. On the one hand, there is a structure<br />

composed of very large cities like Madrid, London, Paris, and Munich, which work<br />

together, and on the other side a network of smaller cities which cooperate. The size<br />

of a city is not only measurable through the size of its administrative population. The<br />

weight of Zurich in the network of European cities, for example, probably benefits<br />

from all other Swiss cities. Each of them contributes with its specialisation (finance<br />

and NGO in Geneva, chemistry industry in Basel, tourism in Lucerne etc.). For some aspects,<br />

this gathering-together of cities is perhaps insufficient. A simple example is that<br />

there is no “Muji” shop 23 in Switzerland, while all the biggest cities in the world have<br />

one. Does Switzerland suffer from the overly-rapid expansion of its city networks?<br />

23 Japanese shop, only present in the biggest metropolises of the world<br />

[30]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

The monitoring of Swiss urban space performed by the Federal Office for Spatial Development<br />

(ARE) sums up the position of Switzerland in Europe from an economic<br />

point of view. ARE stresses Switzerland's innovative power, the amount of decision<br />

and control, availability of a qualified workforce, an efficient national and international<br />

transportation service and last but not least, a high quality of life and a wellpreserved<br />

environment. The metropolitan function of Switzerland's biggest cities is<br />

more important than what we can figure out from their population size. The report<br />

concludes that Zurich is comparable to the big motors of the world, such as Copenhagen,<br />

Dublin, Helsinki, Frankfort am Main, Dusseldorf, Florence, Hamburg and Cologne.<br />

Metropolitan Areas Comparison in Europe in 2003, ARE<br />

“Selon la définition du programme européen de recherche ESPON, les agglomérations<br />

suisses font partie d’un vaste réseau de villes européennes qui compte plus de 1500<br />

régions urbaines (appelées Functional Urban Areas; FUA) d’au moins 20 000 habitante-s<br />

(cf. Comparaison des aires métropolitaines). Les cinq plus grandes agglomérations<br />

suisses se rangent parmi les 200 premières de ce réseau. Zurich et Genève comptent<br />

parmi les 70 agglomérations européennes qui comptent au moins 750 000 habitant-e-s;<br />

elles occupent respectivement le 36e et le 67e rang dans ce classement. Bâle, Berne et<br />

Lausanne se retrouvent respectivement en 72e, 168e et 193e position.<br />

Toutefois, la concentration spatiale d’un grand nombre d’habitant-e-s ne constitue qu’un<br />

aspect du succès d’un espace métropolitain; parmi les autres facteurs, citons le potentiel<br />

économique et la force innovatrice, la forte densité de fonctions de décision et de<br />

contrôle, le réservoir de main d’oeuvre qualifiée, une desserte nationale et internationale<br />

performante, la qualité de vie élevée (y compris en termes de revenu et de pouvoir<br />

d’achat) et un environnement préservé. Quelle est la position des grands centres suisses<br />

à cet égard dans la comparaison européenne ?<br />

Zurich et Genève se situent parmi les dix meilleurs centres européens pour trois ou<br />

quatre des indices représentés, notamment en ce qui concerne le revenu brut en parité de<br />

pouvoir d’achat, le rayonnement comme centre financier, le nombre de sièges de groupes<br />

internationaux (Zurich), le nombre d’organisations internationales (Genève), le nombre<br />

de congrès (Genève) et la fonction de plaque tournante du trafic aérien international<br />

(Zurich). À quelques rares exceptions près (nombre des étudiant-e-s; dans le cas de<br />

Genève: également nombre d’habitant-e-s), les deux plus grandes agglomérations<br />

suisses se rangent dans le premier quart des 180 à 260 agglomérations considérées pour<br />

les analyses.<br />

L’agglomération bâloise, en sa qualité de centre pharmaceutique global, se retrouve en<br />

tête de classement quant à sa performance économique (valeur ajoutée par habitant-e)<br />

et au revenu par habitant-e. Elle se loge dans le premier ou le deuxième quart quant aux<br />

autres spécificités. Lausanne et Berne atteignent des positions qui se situent en majorité<br />

dans la moyenne.<br />

[31]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

Figure 9 Metropolitan areas comparison in Europe in 2003, ARE<br />

[32]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Plusieurs palmarès internationaux de villes, dont certains sont régulièrement actualisés<br />

et qui utilisent une palette d’indicateurs qui varient selon les objectifs, permettent<br />

d’évaluer la position générale des cinq grands centres suisses par rapport aux autres<br />

grandes régions urbaines européennes. Dans les palmarès qui utilisent un grand nombre<br />

de critères, l’agglomération zurichoise se range entre la 20e et la 30e position parmi les<br />

agglomérations européennes (cf. fig. 46). Zurich peut se mesurer à des régions urbaines<br />

telles que Copenhague, Dublin, Helsinki, Francfort-sur-le Main, Dusseldorf, Florence,<br />

Hambourg et Cologne. À certains égards, la situation de Genève est comparable.<br />

Dans le classement général des agglomérations européennes selon ESPON, la grande<br />

agglomération de Zurich compte même parmi les “moteurs européens” qui, en termes<br />

de fonctions caractéristiques d’une grande ville au niveau européen, jouent un rôle<br />

déterminant en Europe. En comparaison avec Zurich et Genève, les agglomérations de<br />

Bâle, Berne et Lausanne présentent moins de caractéristiques typiques d’une métropole.<br />

En considérant les critères utilisés dans le présent contexte, ces trois agglomérations se<br />

rangent entre le 50e et le 200e rang.” 1<br />

“En termes de population, les grandes agglomérations suisses figurent aux rangs 36<br />

(Zurich), 67 (Genève), 72 (Bâle), 168 (Berne) et 193 (Lausanne) sur un total de plus de<br />

1500 agglomérations en Europe.<br />

Dans la comparaison internationale, la fonction métropolitaine des grands centres<br />

suisses est plus affirmée que ne le laisse prévoir le nombre d’habitant-e-s.<br />

La grande agglomération de Zurich compte parmi les 16 espaces urbains que le<br />

programme de recherche européen ESPON qualifie de “moteurs européens”, c’est-à-dire<br />

parmi les centres qui jouent un rôle déterminant en Europe en termes de performance<br />

économique, de fonction de contrôle et de décision, de force innovatrice et de carrefour<br />

aérien international.” 2<br />

1 Meier, H. R. & J. Kuster (2009) Monitoring de l'espace urbain suisse - Analyses des villes et agglomérations,<br />

Office fédéral du développement territorial.<br />

2 Ibid.<br />

[33]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

3. Which Future is Best for Swiss Spatial Development?<br />

[34]<br />

[?]<br />

How is it possible to adapt the planning scale to<br />

territories, taking into account urbanity?<br />

How can town planning guarantee the best conditions for new<br />

spatial negotiations to ensure equality without egalitarianism?<br />

Differences: An urban potential<br />

Can governance scales transcend traditional borders<br />

such as municipal, cantonal or national?<br />

ETH Studio Basel is one of the authors who assume that Switzerland is now urban. The<br />

research group compares the Swiss territory to a big supermarket in which everyone<br />

(or those having the appropriate capital for it) moves to the most attractive supply for<br />

each kind of need. If everything is urban, it does not mean that space is homogenous,<br />

the authors stress. This differentiation of space constitutes the best potential for Switzerland,<br />

says ETH Studio Basel. For this reason, they suggest that instead of trying to<br />

reach equality among every region, their differences should be strengthened 24 .<br />

By synthesizing the history of the Swiss urbanisation process, ETH Studio Basel gives<br />

the following portrait of the current peri-uban context (see next page).<br />

Suggestions of guidelines from a symposium organised by Le<br />

Temps and the review Tracés<br />

The Forum 25 has been a good opportunity to discuss the existence of urban vs. rural<br />

spaces in Switzerland. Yvette Yaggi, Former mayor of Lausanne, expressed her regrets<br />

that in all recent planning analyses in Switzerland, its urban condition is missing from<br />

24 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Materials. Basel, Birkhäuser -<br />

Verlag AG.<br />

25 Symposium organised by Le Temps and the review Tracés (26.11.2006). Traduction by editors

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Switzerland: An Urban Portrait by ETH Studio Basel:<br />

Portrait of Peri-Urban Context<br />

“Networked, polycentric urban regions formed not only in the vicinity of the<br />

metropolitan centres but also around small and medium-sized cities. While many inner<br />

cities experienced a new economic and cultural upswing, with abandoned industrial<br />

complexes and their infrastructures becoming desirable locations for a variety of uses,<br />

there was a coincident development in which centrality was dispersed. In suburban<br />

belts and in undefined urban intermediary zones, new, diffuse centres formed, with<br />

extensive infrastructure, shopping centres, entertainment sites, and in some cases<br />

highly skilled jobs. These regions are dominated by a new form of urban mobility that<br />

is directed eccentrically and tangentially. In the meanwhile nearly all everyday activities<br />

are governed by it. On the edges of large agglomerations, a variety of urbanization<br />

forms can also be observed that are not adequately described by the concept of<br />

“periurbanisation.” Single-family homes, consumer facilities, industrial plants, and<br />

small businesses are settling around villages and towns, creating a dense network of<br />

restless movement between communes.” 1<br />

1 Nouveau paysage urbain, Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait,<br />

Materials. Basel, Birkhäuser - Verlag AG.<br />

symbolic maps, while the awareness of urbanity is necessary for reflection. Biel Mayor<br />

Hans Stöckli calls into question the idea that planning might change politics, because<br />

the results of the past few years show that it is not town planners nor politicians who<br />

made our country as it is today, but business and industry. This means that planners<br />

must try to recover some influence by means of politics. The fifteen participants to<br />

the debate organised by the two papers agreed with this affirmation. Switzerland<br />

has urbanised but without big cities, except Zürich, and in a heterogeneous way.<br />

The conclusions of this symposium are reproduced above, notably the need to find a<br />

larger governance and planning scale.<br />

- Democracy means that people have the same rights, not the same spaces. We should<br />

stop with territorial equality, thinking about space as autonomous territory of same<br />

value. Equity today must be measured through mobility, concludes Laurette Coen.<br />

- Transcend old territorial conceptions opposing rural and urban regions toward new<br />

negotiations spaces.<br />

- Transcend cantonal borders as well. According to Pierre Maudet, Geneva administrative<br />

council and president of the Swiss Western Council, the tax system, mobility, knowledge<br />

exchanges and energy should outline the new map for the negotiation entity, as it is<br />

done for agglomeration projects. 1<br />

1 Nouveau paysage urbain, Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait,<br />

Materials. Basel, Birkhäuser - Verlag AG.<br />

[35]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

SpaceWatch 2008 workshop made the same conclusion as this first bullet, while affirming<br />

in its eight final proposals “Ensure equality without egalitarianism”. “Fairness is the<br />

contemporary expression of equality. It is not about giving the same thing to everyone,<br />

but about ensuring equal opportunities for all”. 26 In the end, we must choose which<br />

form of urbanity we wish, among a vast field of possibilities. What Swiss planner Fred<br />

Wenger (Urbaplan office) says, is that after years of dictating what to do, the real<br />

expertise of planning is about how to organise the debate in order to decide what to<br />

do, which leads to the question of governance, tackled further in the document.<br />

26 Lévy, J. In Lévy, J. (Ed.) (2008) “1m 2 /second”, Territories of Debate in a direct Democracy, “Space:<br />

the Achilles’ heel of sustainable development? ”, Lausanne, <strong>EPFL</strong>-<strong>ENAC</strong>.<br />

[36]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

4. Regional Governance in Switzerland: Basel, Zurich<br />

and Leman example<br />

[?]<br />

Basel tri-national Metropolitan Region<br />

Are cross-borders conurbations taken into account in<br />

European policies and national legislations?<br />

Can the Basel Eurodistrict experience as a conurbation<br />

governed at a regional scale be reproduced in other<br />

contexts such as Geneva lake metropolitan region?<br />

Basel is one of the only exemplary practises in terms of regional scale governance in<br />

Switzerland. Several levels of cooperation exist in the region of Basel and the Rhine<br />

River. For example the tri-national Agglomeration of Basel (ATB) is comprised of 53<br />

communes and 600 000 habitants, the “trinationalen Eurodistricts Basel [TEB]” has<br />

about 800 000 people, and the Regio TriRhena, which corresponds to the metropolitan<br />

region -Bales Mulhouse Freiburg- counts 675 communes, and 2 261 710 habitants<br />

27 . Regio TriRhena has to deal with several obstructions such as railroads and<br />

cemeteries but manages to overcome them. 28<br />

Zürich Metropolitanraum<br />

Recently, the Metropolitankonferenz Zürich introduced a new regional political structure,<br />

“Metropolitanraum Zürich”. Gathering together representatives of 8 Cantons and<br />

65 cities and Communes, this new regional government constituted a private law<br />

association containing an executive power, a House of Cantons and a House of Cities.<br />

Besides these two categories, there are ten persons from the cities of Zürich, in charge<br />

of urban or regional development, tourism, transportation as well representatives<br />

from the Greater Zürich Area (economic lobby) and delegates from the Metropolitanraum<br />

Zürich Association itself.<br />

27 Diener, R., J. Herzog, & al. (2006) Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Materials. Basel, Birkhäuser -<br />

Verlag AG. And http://www.eurodistrictbasel.eu/<br />

28 Urbanisme, n°31, 2006, p.39.<br />

[37]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

The main objectives of the association are to develop the quality-of-living as well as<br />

international competitiveness. It works in four categories: living space, traffic, economy<br />

and society/culture. The area concerned by the Metropolitan space does not<br />

correspond to the Federal Statistical Office (FSO), because it includes the agglomeration<br />

of Lucerne which according to the official definition, does not touch Zürich. The<br />

whole area has 1.9 million inhabitants and 900 000 employments.<br />

[38]<br />

Basel Tri-National Metropolitan Region<br />

“Basel has one of the most developed regional and transnational governance system<br />

in Europe. Again several organs exist at different scales: die Deutsch-Französisch-<br />

Schweizerische Oberrheinkonferenz, die Hochrheinkommission, and RegioTriRhena,<br />

which also has got a council. The TriRhena Council is composed of maxium 75<br />

members, distributed between the 3 countries and counts two chambers. 1 “Cross-border”<br />

conurbations (more than 60 have been identified in Europe) form genuine living areas,<br />

laboratories for a European citizenship in the making. Extending into two or even three<br />

countries, their cross-border situation exacerbates the complexity of the problems faced<br />

by “national” conurbations, but also increases their potential for innovation. Until now<br />

they have been virtually ignored as specific entities by European policies and national<br />

legislations, contractualization and financing even though they call for an innovative<br />

approach to go beyond national boundaries (political, linguistic, institutional, legal,<br />

cultural). The EGTC project will work on the promotion of innovative governance<br />

tools in a panel of cross-border agglomerations by identifying the relevant public and<br />

private stakeholders, and how common diagnoses, strategies, organisation schemes are<br />

developed; in order to highlight best practices, define a common methodology, study how<br />

Structural Funds, public funding and legal tools, such as EGTC (European Grouping<br />

of Territorial Cooperation), could efficiently support cross-border conurbations, and<br />

elaborate recommendations towards public actors at different levels.” 2<br />

1 http://www.regiotrirhena.org<br />

2 European Programme for urban sustainable development, Expertising Governance for Transfrontier<br />

Conurbations.<br />

Lausanne West Side Project<br />

(Schéma Directeur de l’Ouest Lausannois, SDOL)<br />

The western part of Lausanne city (2 600 hectares) today has 65 000 inhabitants and<br />

35 000 jobs. Through this agglomeration project, several areas will replace old industrial<br />

brownfields. The objective is to accommodate around 30 to 40 000 new inhabitants<br />

and jobs. in Lausanne city (which translates to a 30% increase in population) in<br />

this area by 2020 29 . The team paid attention to the dialogue between actors: the City<br />

29 Widmer, A. & Christin J. (2008) Elever la ville. Le développement de l'Ouest lausannois, Avenir<br />

suisse.

Figure 10 Organigram of Basel Eurodistrict (ETB) 1<br />

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

1 "Die Funktionsweise des TEB-Vereins/ Le fonctionnement de l’association ETB", Un avenir à trois,<br />

strategy development ATB (2020) p 111-115.<br />

[39]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

of Lausanne and the Vaud Canton as well as 8 Communes taking part in the project.<br />

The second aspect of the projects is in developing major transportation infrastructures.<br />

Transportation infrastructure can create near-impermeable boundaries in the urban<br />

fabric30 . Politically, there is no new decisional level, but actors negotiate through<br />

a principle of “inter-communality”. Many practitioners mention that it is essential to<br />

decide very clearly who is controlling the process. This is also what the city of Bern is<br />

doing. Today, the project entered into the realisation phase, starting with operational<br />

studies.<br />

Seit dem Übergang zum Trinationalen Eurodistrict Basel im Jahre<br />

2007 hat sich die Satzung weiterentwickelt.<br />

Der TEB-Verein besteht seitdem aus folgenden Organen (vgl. Abb):<br />

Der Mitgliederversammlung, die alle Vereinsmitglieder umfasst (Insgesamt 62, davon<br />

29 aus der Schweiz, 18 aus Frankreich und 15 aus Deutschland).<br />

Dem Vorstand, der 24 politische Vertreter umfasst, darunter 8 deutsche, 8 französische<br />

und 8 Schweizer Mitglieder. Die Vorstandsmitglieder sind gewählte Vertreter der<br />

Gebietskörperschaften im Eurodistrict.<br />

Dem Districtsrat, der sich aus 15 deutschen, 15 französischen und 20 Schweizer<br />

Parlamentariern zusammensetzt. Die gewählten Vertreter im Districtsrat werden von<br />

den drei Ländern selbständig bestimmt.<br />

Den Fachlichen Koordinationsgruppen, die die Geschäftsstelle bei der Umsetzung ihrer<br />

Aufgaben unterstützen und die Abstimmung der Beschlussvorschläge des Vorstands<br />

koordinieren.<br />

Die Geschäftsstelle nimmt die verwaltungsmässigen und operativen Aufgaben des<br />

Eurodistricts wahr. Sie unterstützt und koordiniert die Experten- und Projektgruppen<br />

bei ihrer Tätigkeit.<br />

Experten- und Projektgruppen planen, überwachen und evaluieren auf der Basis<br />

von Projekt- bzw. Arbeitsaufträgen die Umsetzung der diversen Projekte in ihrem<br />

Zuständigkeitsbereich.<br />

Im Laufe der letzten zehn Jahre hat sich eine “gemeinsame Kooperationskultur”<br />

zwischen den Akteuren der trinationalen Zusammenarbeit durch regelmässige Treffen<br />

etabliert.<br />

Depuis 2007, les statuts ont évolué avec la transformation en<br />

Eurodistrict Trinational de Bâle.<br />

L’association ETB est composée désormais des organes suivants (cf. diagramme):<br />

Une assemblée qui réunit les représentants de tous les membres de l’association (62 au<br />

30 Della Casa, F. (2008) Elever la ville, Tokyo New-York, Bienne, Renens: Interview, Avenir suisse.<br />

Marianne Huguenin<br />

[40]

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

total dont 29 en Suisse, 18 en France et 15 en Allemagne).<br />

Le Comité Directeur qui comprend maintenant 24 représentants, huit membres<br />

allemands, huit membres suisses, et huit membres français. Les membres sont des élus<br />

des collectivités du périmètre de l’Eurodistrict.<br />

Un Conseil Consultatif, constitué de 15 membres allemands, 20 membres suisses et 15<br />

membres français. Les élus du Conseil Consultatif sont désignés dans chaque nation<br />

selon des règles qui leur sont propres. Le Conseil Consultatif correspond à l’ancienne<br />

Conférence d’Agglomération.<br />

Un Comité Technique de Coordination (CTC): Il soutient l’Administration dans la<br />

gestion des tâches qui lui sont confiées et assure un rôle de coordination préalable des<br />

décisions du Comité de Direction.<br />

Une administration : Elle exécute les missions opérationnelles et administratives de<br />

l’Eurodistrict. Elle assiste et coordonne les groupes d’experts et de projets dans leurs<br />

domaines de compétences.<br />

Des groupes d’experts et de travail : ils planifient, suivent et évaluent, pour le compte du<br />

Comité de Direction et de l’Assemblée des membres, la mise en œuvre des divers projets<br />

sur la base des missions attribuées dans leur domaine de compétence.<br />

Le système ATB et aujourd’hui de l’ETB relève d’une “culture commune de la<br />

coopération” qui s’est instituée progressivement entre les acteurs de la coopération, suite<br />

aux multiples réunions de travail de ces dix dernières années.<br />

“Les frontières qui traversent la Région métropolitaine lémanique ne tomberont pas<br />

magiquement devant des discours universalistes comme des murailles de Jéricho devant<br />

la volonté divine. Il faut accepter leur existence, reconnaître la souveraineté de chacun,<br />

cerner les problèmes, trouver un terrain d’entente et conclure des alliances pour la<br />

défense des intérêts communs.” 1<br />

“Le défi est de taille ; comment le relever à l’intérieur du corset très serré du fédéralisme ?<br />

Quelle forme donner au gouvernement des métropoles naissantes ?” 2<br />

Un territoire pertinent est “le plus petit espace au sein duquel les différentes fonctions<br />

d‘une société (économique, sociologique, politique, géographique et historique) peuvent<br />

faire système” 3<br />

“Genève doit-elle se tourner vers la France ou plutôt vers le Léman et la Suisse? Y-a-t-il<br />

une métropole lémanique?” 4<br />

1 Comtesse X. & Van der Peol C. (Eds.) (2006) Le feu au lac, Genève, Avenir Suisse, p.167<br />

2 Ibid, p.170.<br />

3 Lévy, J. (June 1996) "Espace et pouvoir en France: une utopie constitutionnelle", Pouvoirs Locaux<br />

29: 91-95.<br />

4 Diener, R., Herzog J., & al. (2006) Switzerland: An urban Portrait, Borders, communes : a brief<br />

history of the territory. Basel, Birkhäuser - Verlag AG.<br />

[41]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

[42]<br />

Governing Geneva Lake metropolitan region<br />

Relating the utopian tale of Lemanopolis, an entire region governed by a metropolitan<br />

government which takes place in 2025, Marc Comina states that we are still far<br />

from this utopia, even though “specialists agree that it would be the ideal solution.” According<br />

to him, it is legitimate to wonder if anyone is taking care of the future metropolis:<br />

Who is going to organise the rail and road networks in order to channel the flow<br />

of commuters, on the scale of the metropolis? Who is going to make sure that the<br />

area remains competitive internationally? Who will take responsibility for designing a<br />

strategy both global and coherent for a metropolitan agglomeration which will soon<br />

house 1.8 million inhabitants? The answer may seem a little provocative, but it is merely<br />

an observation: no one.<br />

According to Comina, we are touching the Gordian knot of Swiss federalism and of<br />

the country’s three layers of institutions (Confederation, Cantons and municipalities)<br />

that are made for a decentralised and rural society. In the 21 st century however,<br />

the greatest challenges we face are in agglomerations: noise, pollution, traffic jams,<br />

exorbitant costs for housing, insecurity; all these problems originate from the same<br />

irreversible phenomenon: urbanisation, which began several decades ago, and is beginning<br />

to deeply affect the balance which had traditionally existed in the Confederation.<br />

The Leman metropolis is invisible when one considers the urbanisation process and<br />

can appear a little messy, “Chacun, pour son compte, va ou il le désire, quitte à ne pas<br />

voir qu’il n’est pas le seul dans son cas.” 31 As the author leads us to understand, it exists<br />

nonetheless, when we consider the amount of commuters on the roads or in pu.blic<br />

transportation. The important point mentioned in this article is that borders are not<br />

going to disappear by themselves, and that overcoming them requires a lot of work.<br />

Lemanopolis<br />

“La population a tranché. A une majorité des deux tiers, les habitants de Lemanopolis ont<br />

accepté la construction d’un nouvel hôpital universitaire. Situé sur le territoire français,<br />

il sera financé à parts égales (33%) par a région Rhône-Alpes, le canton de Vaud et le<br />

canton de Genève. Face aux médias, le maire de Lemanopolis a parlé de “plébiscite” et de<br />

tournant historique”. En acceptant de partager les coûts d’un tel projet d’infrastructure<br />

(100 millions d’Euros), les citoyens ont lancé un signal très clair de confiance et de<br />

soutien au gouvernement franco-suisse récemment mise en place : “Nous sommes en<br />

train de réussi notre pari, qui est de faire de la frontière une ressource et non plus un<br />

handicap”, a ainsi conclu le maire.” 1<br />

1 Comtesse X. & Van der Peol C. (Eds.) (2006) Le feu au lac, Genève, Avenir Suisse, p.167.<br />

31 Comtesse X. & Van der Peol C. (Eds.) (2006) Le feu au lac, Genève, Avenir Suisse, p.167.

Territorial Awarness of Swiss and European Contexts<br />

Two Approaches to Address Swiss Space<br />

“Urbanity ” as a Concept for Swiss Spatial<br />

Development<br />

[?]<br />

How can urbanity be strengthened while Swiss urban attitudes are influenced<br />

by a “rejection culture” (density, height, masses, concentration…)?<br />

How can city planners and architects learn the concept of<br />

urbanity and apply it to Swiss spatial development?<br />

Does strengthening urbanity lead to overcoming political fragmentation<br />

and lack of regional governance in such regions as Lake Geneva ones?<br />

wh a t m a k e s u r b a n It y?<br />

Figure 11 Two models of urbanity by Jacques Lévy 1<br />

1 Lévy, J. (1999) Penser la ville. Le tournant géographique, Penser l’espace pour lire le monde, Belin.<br />

Paris: 241-244.<br />

Lévy, J. (Ed.) (2008) The City: Critical essays in human geography, Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing Limited.<br />

[43]

Space and Us, Today and Tomorrow<br />

Interview with Jacques Lévy<br />

Alliance about Density and Functional and Social Diversity<br />

“Vous définissez deux modèles d’urbanisation: celui d’Amsterdam ou ville compacte et celui<br />

de Johannesburg ou ville diffuse, étalée. Comment analysez-vous les relations entre ces deux<br />

modèles?<br />

Ces modèles sont à la fois symétriques, car tous deux présents dans les pratiques et les<br />

imaginaires urbains, et dissymétriques, dans la mesure où seul le modèle d’Amsterdam<br />

accepte et assume le principe d’urbanité. Ceux qui y adhèrent portent le projet de favoriser<br />

le maximum de diversité dans le minimum d’étendue, ce qui constitue le principe même<br />

de la ville. Inversement, les adeptes du modèle de Johannesburg tentent de profiter de<br />

certains avantages de la ville, tels que l’accessibilité à un grand nombre d’objets ou de<br />

services, tout en rejetant certaines de leurs conséquences, comme la coprésence avec<br />

toutes sortes d’altérités.<br />

Il se trouve qu’à présent ces deux modèles “tiennent la corde”. On peut dire dans<br />

l’ensemble que l’un est majoritaire et l’autre légitime. (…)<br />

En Europe, on constate surtout une extension de la ville diffuse?<br />

Pour les “démunis”, la cohabitation avec l’altérité est perçue comme insupportable parce<br />