Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 shows no beneficiary effects in ...

Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 shows no beneficiary effects in ...

Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 shows no beneficiary effects in ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

AEM Accepts, published onl<strong>in</strong>e ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t on 27 April 2012<br />

Appl. Environ. Microbiol. doi:10.1128/AEM.00395-12<br />

Copyright © 2012, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

<strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> <strong>shows</strong> <strong>no</strong> <strong>beneficiary</strong> <strong>effects</strong> <strong>in</strong> weaned<br />

pigs <strong>in</strong>fected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT 104.<br />

Susanne Kreuzer 1 *, Pawel Janczyk 2 * § , Jens Aßmus 1 , Michael F.G. Schmidt 3 , Gudrun A.<br />

Brockmann 1 , Karsten Nöckler 2<br />

1 Humboldt-Universität zu Berl<strong>in</strong>, Breed<strong>in</strong>g Biology and Molecular Genetics, Invalidenstr. 42,<br />

D-10115 Berl<strong>in</strong>, Germany<br />

2 Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Department of Biological Safety, Unit Molecular<br />

Diag<strong>no</strong>stics and Genetics, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berl<strong>in</strong>, Germany<br />

3 Freie Universität Berl<strong>in</strong>, Institut für Immu<strong>no</strong>logie und Molekularbiologie, Philippstr. 13,<br />

Berl<strong>in</strong>, Germany<br />

*These authors contributed equally to this work<br />

§ correspond<strong>in</strong>g author: pawel_janczyk@t-onl<strong>in</strong>e.de; pawel.janczyk@bfr.bund.de<br />

Runn<strong>in</strong>g title: Effects of E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplementation <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>fection model <strong>in</strong> piglets<br />

SK: Susanne.Kreuzer.1@agrar.hu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de<br />

PJ: pawel_janczyk@t-onl<strong>in</strong>e.de; pawel.janczyk@bfr.bund.de<br />

JA: Jens.Assmus@staff.hu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de<br />

MFGS: michael.schmidt3@fu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de<br />

GAB: gudrun.brockmann@agrar.hu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de<br />

KN: karsten.<strong>no</strong>eckler@bfr.bund.de<br />

1

25<br />

26<br />

27<br />

28<br />

29<br />

30<br />

31<br />

32<br />

33<br />

34<br />

35<br />

36<br />

37<br />

38<br />

39<br />

40<br />

41<br />

42<br />

43<br />

44<br />

45<br />

46<br />

47<br />

48<br />

49<br />

50<br />

Abstract<br />

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT 104 (S. Typhimurium) is the major pathogen<br />

for salmonellosis outbreaks <strong>in</strong> Europe. We tested if the probiotic bacterium <strong>Enterococcus</strong><br />

<strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> (E. <strong>faecium</strong>) can prevent or alleviate samonellosis. Therefore, piglets<br />

of the German Landrace breed that were treated with E. <strong>faecium</strong> (n=16) as a feed additive and<br />

untreated controls (n=16) were challenged with S. Typhimurium 10 days after wean<strong>in</strong>g. The<br />

presence of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> feces and selected organs as well as the immune response were<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigated. Piglets treated with E. <strong>faecium</strong> ga<strong>in</strong>ed less weight than control piglets (p=0.05).<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g of E. <strong>faecium</strong> had <strong>no</strong> effect on fecal shedd<strong>in</strong>g of salmonellae and resulted <strong>in</strong> higher<br />

abundance of the pathogen <strong>in</strong> tonsils of all challenged animals. The specific (anti-Salmonella<br />

IgG) and unspecific (haptoglob<strong>in</strong>) humoral immune responses as well as the cellular immune<br />

response (T helper cells, cytotoxic T cells, regulatory T cells, γδ T cells and B cells) <strong>in</strong> the<br />

lymph <strong>no</strong>des, Peyer’s patches of different segments of the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e (jejunal, ileo-cecal), the<br />

ileal papilla and <strong>in</strong> the blood were affected <strong>in</strong> the course of time after <strong>in</strong>fection (p

51<br />

52<br />

53<br />

54<br />

55<br />

56<br />

57<br />

58<br />

59<br />

60<br />

61<br />

62<br />

63<br />

64<br />

65<br />

66<br />

67<br />

68<br />

69<br />

70<br />

71<br />

72<br />

73<br />

74<br />

75<br />

76<br />

to the comb<strong>in</strong>ed feed were widely used to prevent <strong>in</strong>fection outbreaks <strong>in</strong> the herds. This led to<br />

development of bacterial resistance aga<strong>in</strong>st many antibiotics, and f<strong>in</strong>ally the EU banned their<br />

use <strong>in</strong> pig feed <strong>in</strong> 2006. S<strong>in</strong>ce then, much <strong>in</strong>terest has been raised on the potential use of<br />

alternatives such as probiotics, i.e. live microorganisms, which when adm<strong>in</strong>istered <strong>in</strong><br />

adequate amounts confer a health benefit to the host (5). Probiotics are believed to possess<br />

beneficial <strong>effects</strong> on the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract (GIT) of farm animals, especially the lactic acid-<br />

produc<strong>in</strong>g bacteria (LAB), and thus result <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased performance of piglets. Among the<br />

different mode of actions of the LAB, modulation of the mucosal and systemic immune<br />

systems are considered to play a major role e.g. <strong>in</strong> prophylaxis aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>in</strong>fections (15). The<br />

gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is the largest collection of lymphoid tissues <strong>in</strong> the<br />

body and is therefore an important first barrier aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al pathogens e.g. Salmonella sp.<br />

or Escherichia coli (7). It consists of organized tissues such as jejunal and ileo-cecal<br />

mesenterial lymph <strong>no</strong>des, Peyer’s patches and diffusely scattered <strong>in</strong>traepithelial lymphocytes<br />

(7), which are expected to respond to pathogen <strong>in</strong>fection.<br />

LAB, such as several stra<strong>in</strong>s of lactobacilli and some enterococci, are <strong>in</strong> the focus of research<br />

as they are traditionally used <strong>in</strong> a range of <strong>in</strong>dustrial food fermentations with a long history of<br />

safe use (16). Evidence was provided (14) that <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> (E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong>) reduces the Chlamydia sp. load of healthy piglets. Furthermore, experiments <strong>in</strong><br />

piglets fed with E. <strong>faecium</strong> have shown a reduction of diarrhea (22, 24). Those data suggested<br />

a potential beneficial effect of us<strong>in</strong>g E. <strong>faecium</strong> as probiotic to reduce <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases <strong>in</strong><br />

pigs. In contrast, (21) reported that E. <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> tended to <strong>in</strong>crease the shedd<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> feces and the numbers of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal organs after gastric<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istration of S. Typhimurium DT104 to wean<strong>in</strong>g piglets (crossbred German Landrace<br />

and Duroc).<br />

The aim of the present study was to test the probiotic effect of E. <strong>faecium</strong> on the immune<br />

response after <strong>in</strong>fection with salmonellae. To <strong>in</strong>vestigate whether the <strong>effects</strong> published<br />

3

77<br />

78<br />

79<br />

80<br />

81<br />

82<br />

83<br />

84<br />

85<br />

86<br />

87<br />

88<br />

89<br />

90<br />

91<br />

92<br />

93<br />

94<br />

95<br />

96<br />

97<br />

98<br />

99<br />

100<br />

101<br />

102<br />

previously (21) were <strong>in</strong>cidental or possibly race-specific, the present study was performed<br />

under a similar approach us<strong>in</strong>g the same S. Typhimurium and E. <strong>faecium</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> piglets of<br />

the pure German Landrace. In order to assess the activation of the adaptive systemic and<br />

mucosal immune systems, we determ<strong>in</strong>ed anti-Salmonella IgG as well as the levels of B and<br />

T lymphocyte subpopulations <strong>in</strong> the different tissues of the GALT. Additionally, the effect of<br />

the probiotic on the performance and feed <strong>in</strong>take was <strong>in</strong>vestigated.<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

Animals<br />

We used German Landrace piglets (N=32) of sows that were feed either a diet supplemented<br />

with a probiotic (P group) or a diet without supplementation (C group). The probiotic<br />

supplemented group conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> (E. <strong>faecium</strong>) as a<br />

probiotic additive, the control group was fed the same basic feed without E. <strong>faecium</strong>. Sows of<br />

the P group received E. <strong>faecium</strong> already for three weeks before parturition, and the piglets<br />

were offered the respective comb<strong>in</strong>ed feed with or without E. <strong>faecium</strong> from the age of 12 days<br />

on. Piglets of both feed<strong>in</strong>g groups (n=16 <strong>in</strong> both feed<strong>in</strong>g groups) were weaned at 28 days (d)<br />

of age and were then pair wise allocated to pens. The leftovers were collected daily and feed<br />

<strong>in</strong>take was recorded on dry matter basis. Water was provided via nipple dr<strong>in</strong>kers ad libitum.<br />

The pens’ floors and the feed<strong>in</strong>g troughs were cleaned thoroughly twice daily. After 10 days<br />

of adaptation (at the age of 38 days), all piglets were challenged with Salmonella enterica<br />

serovar Typhimurium DT104 (S. Typhimurium) by <strong>in</strong>tragastric application as described<br />

elsewhere (21). Six piglets from each group were sacrificed on d 2 post <strong>in</strong>fection (pi) and ten<br />

piglets on d28 pi.<br />

The experiment has been approved by the local authority (Landesamt für Gesundheit und<br />

Soziales, Berl<strong>in</strong>) under the ID: G0348/09.<br />

4

103<br />

104<br />

105<br />

106<br />

107<br />

108<br />

109<br />

110<br />

111<br />

112<br />

113<br />

114<br />

115<br />

116<br />

117<br />

118<br />

119<br />

120<br />

121<br />

122<br />

123<br />

124<br />

125<br />

126<br />

127<br />

128<br />

Sampl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

After <strong>in</strong>fection with S. Typhimurium, the follow<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ical and zootechnical parameters were<br />

recorded for all pigs: (i) general condition and fecal score (from 1 to 5, where 1=liquid and<br />

5=firm); (ii) rectal temperature and (iii) shedd<strong>in</strong>g of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> feces were determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

daily for 5 days pi and then once a week; (iv) prevalence of anti-Salmonella IgG <strong>in</strong> blood<br />

samples, which were obta<strong>in</strong>ed before <strong>in</strong>fection and then at weekly <strong>in</strong>tervals, (v) daily feed<br />

<strong>in</strong>take, and (vi) weekly body weight for calculation of the feed conversion ratio (kg feed / kg<br />

weight ga<strong>in</strong>).<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g necropsy, liver, spleen, palat<strong>in</strong>e tonsils, segments of mid-jejunum, ileum, cecum and<br />

ascendent colon (3 rd centripetal gyrus), jejunal and colonic mesenterial lymph <strong>no</strong>des, and<br />

muscle samples from the fore (Musculus triceps brachii) and h<strong>in</strong>d limbs (Musculus gluteus<br />

superficialis) were collected for cultivation of S. Typhimurium.<br />

For the characterization of the immune cells, mesenterial jejunal and ileo-cecal lymph <strong>no</strong>des<br />

as well as Peyer’s patches and ileal papilla were collected from six animals per group on d2<br />

and d28 pi.<br />

Bacterial stra<strong>in</strong>s<br />

The E. <strong>faecium</strong> stra<strong>in</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> is a commercial probiotic feed additive (Cylact<strong>in</strong> ® LBC<br />

ME10, DSM nutritional Products Ltd, Switzerland). It was provided <strong>in</strong> a microencapsulated<br />

form and mixed to the diets of sows, suckl<strong>in</strong>g and weaned piglets at concentrations of 1-5x10 9<br />

colony form<strong>in</strong>g units (CFU) / kg feed.<br />

For the <strong>in</strong>fection with S. Typhimurium, the stra<strong>in</strong> DT104 was chosen as it was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from<br />

a sw<strong>in</strong>e with sepsis (21) and was characterized by multiple resistance aga<strong>in</strong>st antibiotics<br />

(chloramphenicol, ciprofloxac<strong>in</strong>, tetracycl<strong>in</strong>e, florfenicol, ampicill<strong>in</strong>, sulfamethoxazole,<br />

colist<strong>in</strong>, streptomyc<strong>in</strong>, nalidixic acid). The resistance aga<strong>in</strong>st nalidixic acid was used for later<br />

selective cultivation of the stra<strong>in</strong> from the samples. The S. Typhimurium was cultured <strong>in</strong><br />

5

129<br />

130<br />

131<br />

132<br />

133<br />

134<br />

135<br />

136<br />

137<br />

138<br />

139<br />

140<br />

141<br />

142<br />

143<br />

144<br />

145<br />

146<br />

147<br />

148<br />

149<br />

150<br />

151<br />

152<br />

153<br />

154<br />

Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C for 20-22 hours to reach an optical density of 0.69 to 0.72,<br />

correspond<strong>in</strong>g with 2-3x10 9 CFU/mL, which was subsequently confirmed by plat<strong>in</strong>g. Each<br />

piglet was <strong>in</strong>fected with 7 ml of such culture broth (1.4-2.1x10 10 CFU <strong>in</strong> total).<br />

Quantitation of salmonellae<br />

The quantitative detection of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> feces was performed us<strong>in</strong>g a spiral plater<br />

(Whitley, Me<strong>in</strong>trup DWS, Germany) with a detection limit of 4x10 2 CFU/g. For each sample,<br />

50 µl from 5 dilutions were streaked onto 3 xylose-lys<strong>in</strong>e-deoxycholate agar plates<br />

supplemented with 50 µg/ml of NAL (XLD-NAL) and <strong>in</strong>cubated at 37°C for 20-24 h. For<br />

Quantitation of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal organs tissue samples were immersed <strong>in</strong> 95% etha<strong>no</strong>l,<br />

flamed, m<strong>in</strong>ced aseptically, and homogenized with BPW (1:10) <strong>in</strong> filter bags us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

stomacher for 2 m<strong>in</strong> at high speed. All samples were quantified for S. Typhimurium by<br />

plat<strong>in</strong>g of 100 µL of filtrates us<strong>in</strong>g a spiral plater. The detection limit was 2x10 2 CFU/g. In<br />

addition, 1 ml of the 10-fold dilution was streaked directly onto 3 XLD-NAL agar plates to<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease the detection limit to 10 CFU/g. Five hundred µl of blood collected <strong>in</strong> tubes<br />

conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g K-EDTA was streaked onto 3 XLD-NAL agar plates <strong>in</strong> order to test if there was<br />

bacteraemia after the challenge.<br />

The obta<strong>in</strong>ed colony numbers were transformed <strong>in</strong>to log CFU/g to obta<strong>in</strong> nearly <strong>no</strong>rmal<br />

distribution of trait values. Mean values and standard deviations are provided <strong>in</strong> the text.<br />

Isolation of immune cells<br />

Immune cells were characterized for six animals <strong>in</strong> the E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplemented group and<br />

the control group at d2 and d28 pi (Σ n=24). The dissected lymph <strong>no</strong>des were transferred <strong>in</strong>to<br />

15 ml tubes filled with 5 ml phosphate buffered sal<strong>in</strong>e conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 0.2% bov<strong>in</strong>e serum album<strong>in</strong><br />

(PBS/BSA 0.2 %). The Peyer’s Patches and the ileal papilla were put <strong>in</strong>to Hank's Buffered<br />

Salt Solution (HBSS). The <strong>in</strong>dividual tissue samples were pressed through a 70 μm Cell<br />

6

155<br />

156<br />

157<br />

158<br />

159<br />

160<br />

161<br />

162<br />

163<br />

164<br />

165<br />

166<br />

167<br />

168<br />

169<br />

170<br />

171<br />

172<br />

173<br />

174<br />

175<br />

176<br />

177<br />

178<br />

179<br />

180<br />

Stra<strong>in</strong>er (Becton Dick<strong>in</strong>son GmbH, Heidelberg). The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g cell suspensions conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

lymphocytes and peripheral blood mo<strong>no</strong>nuclear cells (PBMC) were further purified by<br />

centrifugation for 30 m<strong>in</strong> at 700g at 20°C <strong>in</strong> a ficoll gradient (Histopaque®-1077, Sigma-<br />

Aldrich Corporation). After f<strong>in</strong>al lysis of erythrocytes <strong>in</strong> Erylyse-Puffer pH 7.2–7.4<br />

(Morphisto GmbH) for 5 m<strong>in</strong> on ice, the immune cells were washed with 10 ml of PBS/BSA<br />

0.2 % and centrifuged for 15 m<strong>in</strong> at 390 g at 4°C.<br />

Flow cytometry<br />

Flow cytometry was performed with purified immune cells. The cells were sta<strong>in</strong>ed with<br />

primary anti-CD4 conjugates <strong>in</strong> a one step-<strong>in</strong>cubation. For each reaction, 1x10 6 cells were<br />

exposed to saturat<strong>in</strong>g concentrations of the antibodies <strong>in</strong> a volume of 30 µl of PBS for 30 m<strong>in</strong><br />

on ice <strong>in</strong> the darkness. Cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS, spun at 2500 g for 5 m<strong>in</strong>, and<br />

resuspended <strong>in</strong> 300 µl PBS. Immune cell antigens CD2, CD25, CD8β, TcR1 and IgM (Table<br />

1) were detected us<strong>in</strong>g unlabelled primary antibodies followed by wash<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>cubation<br />

with a fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody (Table 1). Table 1 displays the source of each<br />

antibody. Different lymphocyte subpopulations were designated by their phe<strong>no</strong>types<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to (18) (γδ T cells, B cells) and (8) (αβ T cells). Per sample, 40,000 lymphocytes<br />

were assayed by flow cytometry (FCM) us<strong>in</strong>g an BD FACSCaliburTM flow cytometer with<strong>in</strong><br />

the lymphocyte gate correspond<strong>in</strong>g to their forward light and sideward light scatter signals<br />

(Figure 1A). From these cells only liv<strong>in</strong>g ones, which were negative for the propidium iodide<br />

(PI) sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (0.5 µg/ml) were further analyzed (Figure 1B). T helper cells (Th), cytotoxic T<br />

cells (Tc) and regulatory T cells (Treg) were determ<strong>in</strong>ed by detection of the surface markers<br />

CD4, CD8β (Figure 1C) and CD25 (Figure 1D), respectively. For phe<strong>no</strong>typic analysis of γδ-<br />

TCR cells, a marker for the δ cha<strong>in</strong> and the surface marker CD2 were chosen <strong>in</strong> the same<br />

scheme as shown for CD4, CD8. Immature and mature naive B cells were identified by<br />

sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with the surface marker IgM.<br />

7

181<br />

182<br />

183<br />

184<br />

185<br />

186<br />

187<br />

188<br />

189<br />

190<br />

191<br />

192<br />

193<br />

194<br />

195<br />

196<br />

197<br />

198<br />

199<br />

200<br />

201<br />

202<br />

203<br />

204<br />

205<br />

206<br />

Serology<br />

Blood samples of all animals were collected from the cranial vena cava at d2 and d28 pi.<br />

Blood was <strong>in</strong>cubated at 37°C for 2 hours, centrifuged for 15 m<strong>in</strong> at 1400 g, and serum was<br />

collected and stored at -20°C until analysis.<br />

The presence of anti-Salmonella antibodies was tested with the Salmotype ® PIGSCREEN<br />

enzyme-l<strong>in</strong>ked immu<strong>no</strong>sorbent assay (ELISA) accord<strong>in</strong>g to the manufacturer’s <strong>in</strong>structions<br />

(Labordiag<strong>no</strong>stik Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany). The IgG levels were calculated us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

reference standard method and presented as percents of the optical density (OD%).<br />

Haptoglob<strong>in</strong> concentrations <strong>in</strong> the sera were analysed by use of the Pig Haptoglob<strong>in</strong> ELISA<br />

Test Kit (Life Diag<strong>no</strong>stics, West Chester, USA) follow<strong>in</strong>g the manufacturer’s <strong>in</strong>structions.<br />

The haptoglob<strong>in</strong> concentrations <strong>in</strong> sera were determ<strong>in</strong>ed by apply<strong>in</strong>g standard curves and<br />

calculated <strong>in</strong> mg/ml.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

Statistical analysis was performed us<strong>in</strong>g R 2.11.1 and SPSS 12.0.2. (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).<br />

For the phe<strong>no</strong>types of immune cells, we analyzed 6 samples per group (d pi x diet).The<br />

experiment had a statistical power level of 0.8 for an anticipated correlation (r²) between diet<br />

and phe<strong>no</strong>ytype of r² ≥ 0.35 and a p-value of 0.1. Alternatively, it had a power of 0.7 to detect<br />

<strong>effects</strong> with a p-value of 0.05. All data values higher than 2-times the <strong>in</strong>terquartiles range<br />

(IQR) below the 1st quartile and above the 3rd quartile were identified as outliers. Outliers<br />

had <strong>no</strong> significant <strong>effects</strong> on test statistics due to less than one percent of outliers <strong>in</strong> our data.<br />

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check raw data for <strong>no</strong>rmal distribution. S<strong>in</strong>ce raw data<br />

were <strong>no</strong>t <strong>no</strong>rmally distributed numbers of salmonellae were log-transformed.<br />

To test the <strong>effects</strong> of supplementation with E. <strong>faecium</strong> on the phe<strong>no</strong>types, we applied an<br />

analysis of variance (ANOVA) with E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplementation <strong>in</strong> the diet, days post<br />

8

207<br />

208<br />

209<br />

210<br />

211<br />

212<br />

213<br />

214<br />

215<br />

216<br />

217<br />

218<br />

219<br />

220<br />

221<br />

222<br />

223<br />

224<br />

225<br />

226<br />

227<br />

228<br />

229<br />

230<br />

231<br />

232<br />

<strong>in</strong>fection and sex as fixed <strong>effects</strong>. The follow<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>ear model was used to assess the variation<br />

(V) for every trait for each tissue:<br />

Vtrait = Vdiet group + Vdays post <strong>in</strong>fection + Vsex + residual error<br />

The amounts of S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> feces and organs were compared us<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>no</strong>n-<br />

parameteric Kruskal-Wallis test because salmonellae could <strong>no</strong>t be cont<strong>in</strong>uously detected <strong>in</strong> all<br />

samples. Differences were considered significant at p

233<br />

234<br />

235<br />

236<br />

237<br />

238<br />

239<br />

240<br />

241<br />

242<br />

243<br />

244<br />

245<br />

246<br />

247<br />

248<br />

249<br />

250<br />

251<br />

252<br />

253<br />

254<br />

255<br />

256<br />

257<br />

258<br />

case, constipation occurred and the faecal score was 5 (hard firm stool) until d4 pi, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

high water demand.<br />

Increased rectal body temperatures (≥40°C) were measured <strong>in</strong> three and two piglets on d1 pi<br />

and <strong>in</strong> seven and eight piglets on d2 pi <strong>in</strong> the C and P groups, respectively. On average,<br />

piglets <strong>in</strong> the C and P groups had elevated rectal temperatures for 1.8±1.0 and 0.9±1.4 days<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the first 7 days pi (p=0.13), and thereafter all piglets had a physiological temperature.<br />

Diarrhea was recorded at score 1 (watery) and 2 (mushy). Before <strong>in</strong>fection, diarrhea (score 1)<br />

was observed <strong>in</strong> one animal from the P group and <strong>in</strong> two control animals (score 2). At the day<br />

of <strong>in</strong>fection, <strong>no</strong> diarrhea was <strong>no</strong>ticed. One day pi, one control piglet had faeces of score 2. On<br />

d2 pi, watery or mushy diarrhea was observed <strong>in</strong> three and one C piglet; and <strong>in</strong> two and three<br />

piglets from the P group, respectively. Three days pi, additional two control and one P piglets<br />

developed diarrhea. The diarrhea lasted for one to two days without statistical differences<br />

between the treatment groups (p=0.442).<br />

Detection of Salmonella Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> feces and organs<br />

None of the animals shed salmonellae before challenge. One day pi, all animals shed S.<br />

Typhimurium, except one and two piglets from the C and P groups, respectively, which<br />

started to shed salmonellae on day two pi. Shedd<strong>in</strong>g of salmonellae lasted from 1 to 28 days,<br />

with levels of 4-8 log CFU per g feces. At the end of the trial, on d28 pi, S. Typhimurium was<br />

detected <strong>in</strong> feces from 1 pig from C (2.8 log CFU/g) and 3 pigs from P (0.9-3.0 log CFU/g)<br />

without significant differences between groups (Figure 2A).<br />

S. Typhimurium was detected <strong>in</strong> the wall of GIT (2.4-6.4 log CFU/g) and <strong>in</strong> mesenterial LN<br />

(2.5-3.1 log CFU/g) of all pigs on d2 pi. S. Typhimurium was also present on d2 pi <strong>in</strong> tonsils<br />

from one pig from C (2.8 log CFU/g) and 2 from P (2.1-3.7 log CFU/g); and on d28 pi <strong>in</strong> one<br />

C (5.7 log CFU/g) and <strong>in</strong> four pigs from P (1.2–5.9 log CFU/g). Sporadically S. Typhimurium<br />

could be also detected <strong>in</strong> liver and spleen on d2 pi. On d28 pi, S. Typhimurium was detected<br />

10

259<br />

260<br />

261<br />

262<br />

263<br />

264<br />

265<br />

266<br />

267<br />

268<br />

269<br />

270<br />

271<br />

272<br />

273<br />

274<br />

275<br />

276<br />

277<br />

278<br />

279<br />

280<br />

281<br />

282<br />

283<br />

284<br />

<strong>in</strong> the P group <strong>in</strong> the wall from ileum of 2 and <strong>in</strong> the wall from jejunum of 5 piglets. At this<br />

time, 3 piglets from C and 3 piglets from P had S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> the wall of cecum; 2<br />

piglets from C and one piglet from P <strong>in</strong> colon. No effect of the probiotic on the CFU numbers<br />

could be observed (Figure 2B, 2C). Furthermore, <strong>no</strong> salmonellae could be isolated from the<br />

blood show<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>no</strong> bacteraemia had occurred.<br />

Humoral immunity - anti-Salmonella IgG<br />

For all samples measured, the anti-Salmonella IgG titers were below the 20%-cut-off value<br />

(Figure 2D). Although low throughout, the levels of specific antibodies were significantly<br />

higher <strong>in</strong> E. <strong>faecium</strong> treated than <strong>in</strong> untreated piglets (p0.5). However,<br />

the high standard deviations of the mean IgG titers <strong>in</strong> both groups implicate high <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

variability <strong>in</strong> the immu<strong>no</strong>logical response to the S. Typhimurium challenge, which did <strong>no</strong>t<br />

correlate with the numbers of salmonellae shed <strong>in</strong> faeces.<br />

Acute phase prote<strong>in</strong> haptoglob<strong>in</strong> as part of <strong>in</strong>nate immunity<br />

At wean<strong>in</strong>g, haptoglob<strong>in</strong> concentrations <strong>in</strong> serum were 2.18±1.1 and 1.98±0.44 mg/ml <strong>in</strong> C<br />

and P, respectively. They rema<strong>in</strong>ed at the elevated level <strong>in</strong> C, and <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> P (p=0.048)<br />

one week later (Figure 2E). After the adaptation period, at the day of challenge the<br />

haptoglob<strong>in</strong> levels decreased (p

285<br />

286<br />

287<br />

288<br />

289<br />

290<br />

291<br />

292<br />

293<br />

294<br />

295<br />

296<br />

297<br />

298<br />

299<br />

300<br />

301<br />

302<br />

303<br />

304<br />

305<br />

306<br />

307<br />

308<br />

309<br />

310<br />

haptoglob<strong>in</strong> was slow and reached a significantly lower level only on d28 pi (p

311<br />

312<br />

313<br />

314<br />

315<br />

316<br />

317<br />

318<br />

319<br />

320<br />

321<br />

322<br />

323<br />

324<br />

325<br />

326<br />

327<br />

328<br />

329<br />

330<br />

331<br />

332<br />

333<br />

334<br />

335<br />

336<br />

In an ANOVA analysis over the whole test period, there were <strong>no</strong> significant <strong>effects</strong> <strong>in</strong> the<br />

tested immune cell populations between the probiotic treated group and the control group, and<br />

<strong>no</strong> <strong>effects</strong> between sexes.<br />

Discussion<br />

E. <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> has been widely approved as a probiotic feed supplement for use <strong>in</strong><br />

animals <strong>in</strong> the European Union. To obta<strong>in</strong> the approval for commercial use, a feed additive<br />

must possess at least one of the characteristics stated <strong>in</strong> Article 5 (3) of the Regulation No<br />

1831/2003 (2). When apply<strong>in</strong>g for approval of a bacterial stra<strong>in</strong> as a probiotic feed additive, it<br />

is therefore sufficient to show that a given stra<strong>in</strong> will “favourably affect animal production,<br />

performance or welfare, particularly by affect<strong>in</strong>g the gastro-<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al flora or digestibility of<br />

feed<strong>in</strong>g stuffs” (2). Studies to test the beneficial effect of E. <strong>faecium</strong> mostly focused on<br />

zootechnical parameters such as feed <strong>in</strong>take, daily weight ga<strong>in</strong>, and feed conversion ratio<br />

under commercial farm conditions, without focus on targeted <strong>in</strong>fection (11, 24).<br />

In the present study, we exam<strong>in</strong>ed the effect of E. <strong>faecium</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration with respect to the<br />

response to S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong> weaned piglets of the German Landrace breed. In our<br />

bacterial challenge trial, E. <strong>faecium</strong> fed piglets ga<strong>in</strong>ed even less weight than the untreated<br />

control animals. This <strong>shows</strong> that there are <strong>no</strong> positive <strong>effects</strong> of this probiotic on the pig’s<br />

bodily development <strong>in</strong> face of an <strong>in</strong>fection with S. Typhimurium. Similarly, the same<br />

probiotic (Cylact<strong>in</strong> ® ) reduced daily weight ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> un<strong>in</strong>fected piglets fed the probiotic <strong>in</strong> the<br />

same way, without further <strong>effects</strong> on feed conversion ratio (12, 22). In contrast, (24) reported<br />

improvement of daily weight ga<strong>in</strong> (17g/day) of unweaned piglets kept under farm conditions,<br />

fed the same probiotic stra<strong>in</strong> suspended <strong>in</strong> liquid or gel form. Therefore, it rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear if<br />

different form of application (liquid, microencapsulated; once or for several days) or other<br />

factors such as farm conditions, genetic background of the animals or gestation number could<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence the <strong>effects</strong> of the E. <strong>faecium</strong> on the body weight ga<strong>in</strong>.<br />

13

337<br />

338<br />

339<br />

340<br />

341<br />

342<br />

343<br />

344<br />

345<br />

346<br />

347<br />

348<br />

349<br />

350<br />

351<br />

352<br />

353<br />

354<br />

355<br />

356<br />

357<br />

358<br />

359<br />

360<br />

361<br />

In the present study, we <strong>in</strong>vestigated the effect of E. <strong>faecium</strong> as a probiotic on shedd<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

pathogen bacteria <strong>in</strong> a model challeng<strong>in</strong>g experiment with Salmonella enterica serovar<br />

Typhimurium DT104 <strong>in</strong>fection. The virulence of the S. Typhimurium stra<strong>in</strong> used for <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

could be confirmed <strong>in</strong> one <strong>in</strong>fected piglet. All others piglets developed mild cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs<br />

only. Nevertheless, colonization of the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract with S. Typhimurium occurred <strong>in</strong><br />

all pigs s<strong>in</strong>ce all of them shed salmonellae for at least two days after <strong>in</strong>fection. It is well<br />

k<strong>no</strong>wn that <strong>in</strong> the course of pathogenesis after salmonellae <strong>in</strong>fection, the wall of the<br />

gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract is actively <strong>in</strong>vaded by the pathogen us<strong>in</strong>g different mechanisms (9)<br />

before it multiplies and spreads to other organs through macrophages thereby reach<strong>in</strong>g other<br />

lymphatic organs such as the mesenterial lymph <strong>no</strong>des of the small and large <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e, the<br />

spleen and tonsils (6). In the present study we could <strong>no</strong>t observe any protective <strong>effects</strong> of E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong>, neither on cl<strong>in</strong>ical symptoms of salmonellosis, <strong>no</strong>r on S. Typhimurium shedd<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

distribution <strong>in</strong>to <strong>in</strong>ternal organs. This is <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with the results obta<strong>in</strong>ed from a similar<br />

experimental sett<strong>in</strong>g (21). In contrast, (1) reported a reduced number of shed S. Typhimurium<br />

without <strong>effects</strong> on the duration of the shedd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Large White x Landrace weaned piglets fed<br />

with a cocktail of five different probiotic stra<strong>in</strong>s of LAB. It is <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g that reports on the<br />

<strong>effects</strong> of probiotics on pathogen <strong>in</strong>fection often provide controversial results. We suspect that<br />

the reasons can be manifold. The choice of the pathogen, the way of <strong>in</strong>fection (oral once or<br />

for several days, <strong>in</strong>tragastric, “troyan model”), the <strong>in</strong>fection pressure and other controlled or<br />

uncontrollable experimental conditions as well as genetic predisposition could play a role <strong>in</strong><br />

yield<strong>in</strong>g variable effect of probiotics. We would like to emphasize for the present study, that<br />

the pens and feed<strong>in</strong>g troughs were cleaned thoroughly twice daily and that this rigorous<br />

hygienic regime <strong>in</strong> our experiment was obviously sufficient to reduce the number of<br />

pathogens <strong>in</strong> the environment and therefore to elim<strong>in</strong>ate or at least reduce the source of re-<br />

<strong>in</strong>fection. This could have an impact on the lack of differences between the two experimental<br />

14

362<br />

363<br />

364<br />

365<br />

366<br />

367<br />

368<br />

369<br />

370<br />

371<br />

372<br />

373<br />

374<br />

375<br />

376<br />

377<br />

378<br />

379<br />

380<br />

381<br />

382<br />

383<br />

384<br />

385<br />

386<br />

387<br />

groups. On the other hand, the control pigs coped very well and recovered from the <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

without any additional help which underl<strong>in</strong>es the importance of proper management.<br />

The present study confirms that feed<strong>in</strong>g E. <strong>faecium</strong> to piglets resulted <strong>in</strong> higher numbers of S.<br />

Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> tonsils, as reported previously (21). The higher abundance of salmonellae <strong>in</strong><br />

the tonsils last<strong>in</strong>g for at least 28 days after <strong>in</strong>fection could become a source for re-<strong>in</strong>fection of<br />

the pigs and thus be responsible for subcl<strong>in</strong>ical and chronic <strong>in</strong>fections of a pig herd.<br />

Furthermore, <strong>in</strong>fected tonsils could also be a potential source of contam<strong>in</strong>ation of meat at<br />

slaughter. From this perspective, our data would provide evidence aga<strong>in</strong>st the use of E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> as a probiotic feed supplement <strong>in</strong> pigs to prevent <strong>in</strong>fection of meat<br />

and thereby potentially humans via the slaughter house.<br />

Probiotics are considered to modulate the host’s immune system result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an improvement<br />

of protection aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>in</strong>fections (20). In the previous study (21) higher levels of serum IgM<br />

and IgA aga<strong>in</strong>st S. Typhimurium could be observed <strong>in</strong> the group fed E. <strong>faecium</strong> without any<br />

<strong>effects</strong> on serum anti-S. Typhimurium IgG. Also <strong>in</strong> the present study, E. <strong>faecium</strong> had <strong>no</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g effect on serum IgG after <strong>in</strong>fection. However, we found that the <strong>in</strong>crease of<br />

mo<strong>no</strong>meric cell surface bound IgM was more prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> the E. <strong>faecium</strong> treated group<br />

(p

388<br />

389<br />

390<br />

391<br />

392<br />

393<br />

394<br />

395<br />

396<br />

397<br />

398<br />

399<br />

400<br />

401<br />

402<br />

403<br />

404<br />

405<br />

406<br />

407<br />

408<br />

409<br />

410<br />

411<br />

412<br />

413<br />

magnitude than those <strong>in</strong> viral <strong>in</strong>fection studies <strong>in</strong> pigs (17). The level rema<strong>in</strong>ed elevated for a<br />

longer time <strong>in</strong> probiotic-fed pigs than <strong>in</strong> controls, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g either longer last<strong>in</strong>g synthesis<br />

and release of the acute phase prote<strong>in</strong>, or its slower degradation when E. <strong>faecium</strong> was <strong>in</strong> the<br />

diet. Thus, these data suggest that the <strong>no</strong>n-specific reaction of the immune system was<br />

activated for a longer time under the probiotic treatment. As we failed to f<strong>in</strong>d differences <strong>in</strong><br />

the relative cell count of B cells with cell surface bound mo<strong>no</strong>meric IgM between the E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong> supplemented and the control groups <strong>in</strong> GALT, we hypothesize that there was <strong>no</strong><br />

stimulation of the immune response aga<strong>in</strong>st S. Typhimurium by E. <strong>faecium</strong>. This is <strong>in</strong><br />

agreement with previous results obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Landrace x Duroc piglets (21). The same stra<strong>in</strong> of<br />

E. <strong>faecium</strong> that we fed to sows and piglets could reduce the rate of naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>fection with Chlamydia sp. <strong>in</strong> pigs (14). Consider<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>effects</strong> of E. <strong>faecium</strong> on <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

with salmonellae or chlamydiae <strong>in</strong> the previous studies (14, 21), the authors observed a<br />

reduction of the cytotoxic CD8 + subpopulation of <strong>in</strong>traepithelial and circulat<strong>in</strong>g lymphocytes<br />

and therefore discussed as possible mechanism that E. <strong>faecium</strong> activates the production and<br />

secretion of IgM and IgA, and the reduction of the CD8 + lymphocytes could be a result of<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al pathogen bound by the antibodes. In our study, the<br />

frequency of cytotoxic CD8 + T cells <strong>in</strong> tissues responsible for the removal of cells <strong>in</strong>fected by<br />

S. Typhimurium was lower <strong>in</strong> E. <strong>faecium</strong> treated pigs than <strong>in</strong> control animals. This is <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

with the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, that the frequency of salmonellae was also higher <strong>in</strong> tissues of the probiotic<br />

feed group. Otherwise, the proportion of circulat<strong>in</strong>g effector CD8 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes<br />

was enhanced <strong>in</strong> the peripher blood mo<strong>no</strong>nuclear cells <strong>in</strong> the E. <strong>faecium</strong> treated group two<br />

days post <strong>in</strong>fection. Therefore, one could assume an alternative mechanism caused by E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong>. Maybe E. <strong>faecium</strong> potentially <strong>in</strong>hibits efficient hom<strong>in</strong>g of the effector cytotoxic T<br />

cells. This would expla<strong>in</strong> the lower clearance of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> the E. <strong>faecium</strong> treated group.<br />

That goes with the assumption that E. <strong>faecium</strong> would enhance the IgM and IgA production<br />

and secretion, and therefore the stimulation of more naive T cells to differentiate <strong>in</strong>to<br />

16

414<br />

415<br />

416<br />

417<br />

418<br />

419<br />

420<br />

421<br />

422<br />

423<br />

424<br />

425<br />

426<br />

427<br />

428<br />

429<br />

430<br />

431<br />

432<br />

433<br />

434<br />

435<br />

436<br />

437<br />

438<br />

439<br />

circulat<strong>in</strong>g effector T cells. Although the assumptions of the possible mechanisms of the<br />

<strong>effects</strong> of an E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplementation on a S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong>fection made here are <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

with previous studies, one has to consider, that we did <strong>no</strong>t measure antigen-specific T or B<br />

cell response. Therefore the mechanism has to be elucidated <strong>in</strong> further research. However, the<br />

same pattern of low shedd<strong>in</strong>g of salmonellae <strong>in</strong> both groups suggests that this mechanism<br />

does <strong>no</strong>t result <strong>in</strong> an improved elim<strong>in</strong>ation of the pathogen from the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract of<br />

the piglets. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to previous published evidence (19, 23), we detected a high percentage<br />

of CD2 - γδ T cells <strong>in</strong> the peripheral blood with only few such cells accumulated <strong>in</strong> the<br />

lymphoid tissues of the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e. CD2 + γδ T cells were present <strong>in</strong> all exam<strong>in</strong>ed tissues and <strong>in</strong><br />

blood with a frequency of 1-2%. Neither the CD2 - γδ T cells <strong>no</strong>r the CD2 + γδ T cells showed<br />

a difference between the E. <strong>faecium</strong> and control group. Although the CD2 + γδ T cells, which<br />

are additionally express<strong>in</strong>g CD8αα, are believed to be potentially cytotoxic (18) and hence are<br />

able to clear salmonellae <strong>in</strong>fected cells, γδ T cells seemed to be <strong>no</strong> target of activation for E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong> derived signal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our salmonellae challenge experiment. The number of B cells <strong>in</strong><br />

ileal Peyer’s patches, and ileal papilla significantly (p

440<br />

441<br />

442<br />

443<br />

444<br />

445<br />

446<br />

447<br />

448<br />

449<br />

450<br />

451<br />

452<br />

453<br />

454<br />

455<br />

456<br />

457<br />

458<br />

459<br />

460<br />

461<br />

462<br />

Ack<strong>no</strong>wledgements<br />

The authors thank Dr. Robert Pieper, Freie Universität Berl<strong>in</strong>, for provid<strong>in</strong>g the piglets and<br />

En<strong>no</strong> Luge and the team of Dr. Stefanie Banneke from the Research Institute for Risk<br />

Assessment, Berl<strong>in</strong> for the excellent animal care and technical support dur<strong>in</strong>g the experiment.<br />

We further thank Prof. Klaus Osterrieder for permission to use his flow cytometer.<br />

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche<br />

Forschungsgeme<strong>in</strong>schaft, DFG) with<strong>in</strong> the Collaborative Research Group (SFB,<br />

Sonderforschungsbereich) 852/1 “Nutrition and <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al microbiota - host <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong> the<br />

pig”. The authors are solely responsible for the data and do <strong>no</strong>t represent any op<strong>in</strong>ion of<br />

neither the DFG <strong>no</strong>r other public or commercial entity.<br />

References<br />

1. Casey PG, Gard<strong>in</strong>er GE, Casey G, Bradshaw B, Lawlor PG, Lynch PB, Leonard FC,<br />

Stanton C, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Hill C. 2007. A five-stra<strong>in</strong> probiotic comb<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

reduces pathogen shedd<strong>in</strong>g and alleviates disease signs <strong>in</strong> pigs challenged with Salmonella<br />

enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1858-1863.<br />

2. Council Journal. 2003. Additives for use <strong>in</strong> animal nutrition. REGULATION (EC) No<br />

1831/2003. Official Journal of The European Parliament And The Council, L268/29.<br />

3. Denyer MS, Wileman TE, Stirl<strong>in</strong>g CM, Zuber B, Takamatsu HH. 2006. Perfor<strong>in</strong><br />

expression can def<strong>in</strong>e CD8 positive lymphocyte subsets <strong>in</strong> pigs allow<strong>in</strong>g phe<strong>no</strong>typic and<br />

functional analysis of natural killer, cytotoxic T, natural killer T and MHC un-restricted<br />

cytotoxic T-cells. Vet. Immu<strong>no</strong>l. Immu<strong>no</strong>pathol. 110:279-292.<br />

4. EFSA. 2010. The Community Summary Report on trends and sources of zoo<strong>no</strong>ses and<br />

zoo<strong>no</strong>tic agents and food-borne outbreaks <strong>in</strong> the European Union <strong>in</strong> 2008. EFSA Journal.<br />

18

463<br />

464<br />

465<br />

466<br />

467<br />

468<br />

469<br />

470<br />

471<br />

472<br />

473<br />

474<br />

475<br />

476<br />

477<br />

478<br />

479<br />

480<br />

481<br />

482<br />

483<br />

484<br />

485<br />

486<br />

5. FAO/WHO. 2001. Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics <strong>in</strong> Food <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. FAO/WHO.<br />

6. Fedorka-Cray PJ, Whipp SC, Isaacson RE, Nord N, Lager K. 1994. Transmission of<br />

Salmonella Typhimurium to sw<strong>in</strong>e. Vet. Microbiol. 41:333-344.<br />

7. Forchielli ML, Walker WA. 2005. The role of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and<br />

mucosal defence. Br. J. Nutr. 93(Suppl):S41-S48.<br />

8. Gerner W, Kaser T, Saalmuller A. 2009. Porc<strong>in</strong>e T lymphocytes and NK cells--an<br />

update. Dev. Comp. Immu<strong>no</strong>l. 33:310-320.<br />

9. Hallstrom K, McCormick BA. 2011. Salmonella <strong>in</strong>teraction with and passage through<br />

the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al mucosa: Through the lens of the organism. Front. Microbiol. 2:(Article88)1-<br />

10..<br />

10. Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A,<br />

Hoekstra RM. 2010. The global burden of <strong>no</strong>ntyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Cl<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Infect. Dis. 50:882-889.<br />

11. Männer KBK, Schneider D. 1991. Verbesserung der Gesundheit von Ferkeln und Sauen.<br />

Kraftfutter 5:227-231.<br />

12. Mart<strong>in</strong> L, Pieper R, Goodarzi-Boroojeni F, Vahjen W, Neumann K, Van Kessel A,<br />

Zentek J. 2011. Influence of <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> <strong>NCIMB</strong> <strong>10415</strong> on performance, small<br />

<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al morphology, gene expression and brush border enzyme activity <strong>in</strong> piglets, p 55.<br />

Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of the International Scientific Conference on Probiotics and Prebiotics<br />

IPC2011, Kosice, Slovakia, June 14th - 16th 2011.<br />

13. P<strong>in</strong>eiro C, P<strong>in</strong>eiro M, Morales J, Andres M, Lorenzo E, Pozo MD, Alava MA,<br />

Lampreave F. 2009. Pig-MAP and haptoglob<strong>in</strong> concentration reference values <strong>in</strong> sw<strong>in</strong>e<br />

from commercial farms. Vet. J. 179:78-84.<br />

19

487<br />

488<br />

489<br />

490<br />

491<br />

492<br />

493<br />

494<br />

495<br />

496<br />

497<br />

498<br />

499<br />

500<br />

501<br />

502<br />

503<br />

504<br />

505<br />

506<br />

507<br />

508<br />

509<br />

510<br />

511<br />

512<br />

14. Pollmann M, Nordhoff M, Pospischil A, Ted<strong>in</strong> K, Wieler LH. 2005. Effects of a<br />

probiotic stra<strong>in</strong> of <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> on the rate of natural chlamydia <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong><br />

sw<strong>in</strong>e. Infect. Immun. 73:4346-4353.<br />

15. Romeo J, Nova E, Waernberg J, Gomez-Mart<strong>in</strong>ez S, Diaz Ligia SE, Marcos A. 2010.<br />

Immu<strong>no</strong>modulatory effect of fibres, probiotics and synbiotics <strong>in</strong> different life-stages. Nutr.<br />

Hosp. 25:341-349.<br />

16. Saxel<strong>in</strong> M, Tynkkynen S, Mattila-Sandholm T, de Vos WM. 2005. Probiotic and other<br />

functional microbes: from markets to mechanisms. Curr. Op<strong>in</strong>. Biotech<strong>no</strong>l. 16:204-211.<br />

17. Segales J, P<strong>in</strong>eiro C, Lampreave F, Nofrarias M, Mateu E, Calsamiglia M, Andres<br />

M, Morales J, P<strong>in</strong>eiro M, Dom<strong>in</strong>go M. 2004. Haptoglob<strong>in</strong> and pig-major acute prote<strong>in</strong><br />

are <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> pigs with postwean<strong>in</strong>g multisystemic wast<strong>in</strong>g syndrome (PMWS). Vet.<br />

Res. 35:275-282.<br />

18. S<strong>in</strong>kora M, Butler JE, Holtmeier W, S<strong>in</strong>korova J. 2005. Lymphocyte development <strong>in</strong><br />

fetal piglets: facts and surprises. Vet. Immu<strong>no</strong>l. Immu<strong>no</strong>pathol. 108:177-184.<br />

19. S<strong>in</strong>kora M, S<strong>in</strong>kora J, Rehakova Z, Splichal I, Yang H, Parkhouse RM, Trebichavsk<br />

I. 1998. Prenatal ontogeny of lymphocyte subpopulations <strong>in</strong> pigs. Immu<strong>no</strong>l. 95:595-603.<br />

20. Soccol CR, de Souza Vandenberghe LP, Spier MR, Pedroni Medeiros AP,<br />

Yamaguishi CT, L<strong>in</strong>dner JDD, Pandey A, Thomaz-Soccol V. 2010. The potential of<br />

probiotics: a review. Food Tech<strong>no</strong>l. Biotech<strong>no</strong>l. 48:413-434.<br />

21. Szabo I, Wieler LH, Ted<strong>in</strong> K, Scharek-Ted<strong>in</strong>´L, Taras D, Hensel A, Appel B,<br />

Noeckler K. 2009. Influence of a probiotic stra<strong>in</strong> of <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> on Salmonella<br />

enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong> a porc<strong>in</strong>e animal <strong>in</strong>fection model.<br />

Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2621-2628.<br />

22. Taras D, Vahjen W, Macha M, Simon O. 2006. Performance, diarrhea <strong>in</strong>cidence, and<br />

occurrence of Escherichia coli virulence genes dur<strong>in</strong>g long-term adm<strong>in</strong>istration of a<br />

probiotic <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> stra<strong>in</strong> to sows and piglets. J. Anim. Sci.84:608-617.<br />

20

513<br />

514<br />

515<br />

516<br />

517<br />

518<br />

23. Yang H, Parkhouse RM. 1996. Phe<strong>no</strong>typic classification of porc<strong>in</strong>e lymphocyte<br />

subpopulations <strong>in</strong> blood and lymphoid tissues. Immu<strong>no</strong>l. 89:76-83.<br />

24. Zeyner A, Boldt E. 2006. Effects of a probiotic <strong>Enterococcus</strong> <strong>faecium</strong> stra<strong>in</strong><br />

supplemented from birth to wean<strong>in</strong>g on diarrhoea patterns and performance of piglets. J.<br />

Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 90:25-31.<br />

21

519<br />

520<br />

521<br />

522<br />

523<br />

524<br />

525<br />

526<br />

527<br />

528<br />

529<br />

530<br />

531<br />

532<br />

533<br />

534<br />

535<br />

536<br />

537<br />

538<br />

539<br />

540<br />

541<br />

542<br />

543<br />

544<br />

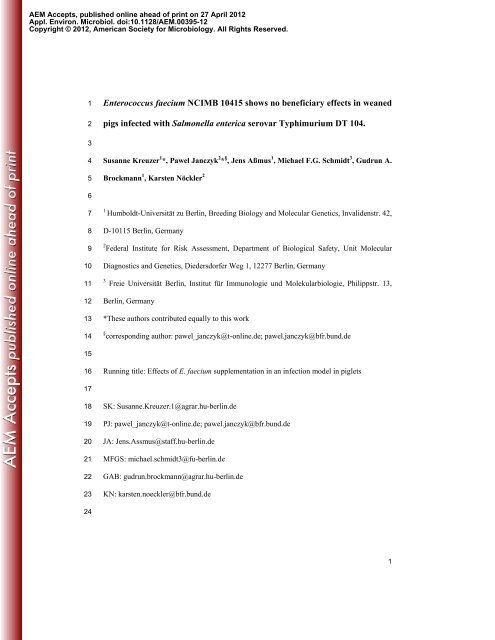

FIGURE 1 Gat<strong>in</strong>g and selection strategies of the flow cytometry data for the analyses of<br />

lymphocyte subpopulations<br />

The x and y axes show the <strong>in</strong>tensity of the light scatter or fluorescent signal. Framed cells<br />

populations <strong>in</strong> A were further analysed <strong>in</strong> B etc. A) Lymphocytes gated accord<strong>in</strong>g to their<br />

forward sideward light scatter signals. Circulated lymphocytes represent 40,000 cells. B) only<br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g PI negative cells were taken for analyses. C) Relative cell counts of liv<strong>in</strong>g lymphocyte<br />

subpopulations (CD8pos = cytotoxic T cells; CD4pos,CD8pos = pig specific double positive<br />

cells, CD4pos = T helper cells) detected with antibodies CD8β and CD4 were calculated. D)<br />

the relative number of CD25high cells of the CD4pos cells were calculated.<br />

FIGURE 2 Colonization of piglets with salmonellae and the reaction of their immune<br />

systems on the <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

Shedd<strong>in</strong>g of Salmonella Typhimurium <strong>in</strong> feces (A) and <strong>in</strong> organs either two (B) or 28 days<br />

(C), as well as serum anti-salmonella IgG titres (D) and haptoglob<strong>in</strong> concentration (E) after<br />

<strong>in</strong>tra-gastric S. Typhimurium <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong> groups of piglets that were either untreated controls<br />

(open squares - C) or treated with E. <strong>faecium</strong> (gray squares - P). Colony form<strong>in</strong>g units (CFU)<br />

per gram feces were log transformed to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>no</strong>rmal distribution. Box-Whisker plots<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate the median (horizontal l<strong>in</strong>es), the lower and upper quartiles (lower and upper borders<br />

of the boxes); m<strong>in</strong>imum and maximum as well as the outliers (mild - open circles; extreme -<br />

asterix) are presented.<br />

FIGURE 3 Relative cell counts to the liv<strong>in</strong>g lymphocyte population of αβ T cells<br />

A) CD8β pos (cytotoxic T cells), B) CD8β and CD4 pos cells and D) CD4 pos (T helper cells)<br />

<strong>in</strong> peripher blood mo<strong>no</strong>nuclear cells (PBMCs), ileal lymph <strong>no</strong>des (IL LN), ileal Peyers Patch<br />

(IL PP) and papilla (PAP IL) of the E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplemented group (P) and the <strong>no</strong>n E.<br />

<strong>faecium</strong> supplemented control group (C) for the time po<strong>in</strong>ts 2 dpi and 28 dpi. 3C) FACS<br />

22

545<br />

546<br />

547<br />

548<br />

549<br />

550<br />

551<br />

552<br />

553<br />

554<br />

555<br />

556<br />

557<br />

558<br />

559<br />

560<br />

561<br />

562<br />

scatter plots of one female piglet derived from P at d2 pi as an example for the appearance of<br />

T helper cells, cytotoxic T cells and CD4 + CD8 + T cells <strong>in</strong> the PBMCs, IL LN, ILPP and PAP<br />

IL. All piglets were <strong>in</strong>fected with S. Typhimurium.<br />

FIGURE 4 Relative cell counts to the liv<strong>in</strong>g lymphocyte population of γδ T cells<br />

A) CD2 and γδ TCR positive cells B) γδ TCR positive (CD2 negative) cells <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong> peripher<br />

blood mo<strong>no</strong>nuclear cells (PBMCs), ileal lymph <strong>no</strong>des (IL LN), ileal Peyer’s patch (IL PP) and<br />

papilla (PAP IL) of piglets from E. <strong>faecium</strong> supplemented group (P) and the control group (C)<br />

2d and 28 d after challenge with S. Typhimurium.<br />

FIGURE 5 Relative cell counts to the liv<strong>in</strong>g lymphocyte population of B cells<br />

A) IgM positive cells (B cells) of one piglet representative for E.<strong>faecium</strong> supplemented group<br />

(P), 2 dpi <strong>in</strong> the ileal lymph <strong>no</strong>de (IL LN) and one piglet representative for control (C), 2 dpi<br />

<strong>in</strong> IL LN. B), C), D) IgM positive cells (B cells) of 12 piglets from P and of 12 piglets from C<br />

at the time po<strong>in</strong>ts 2 dpi (n=6) and 28 dpi (n=6) <strong>in</strong> B) mesenteric lymph <strong>no</strong>des (LN) of jejunum<br />

(Je LN) and ileum (IL LN), <strong>in</strong> C) peripher blood mo<strong>no</strong>nuclear cells (PBMCs) and <strong>in</strong> D) the<br />

ileal Peyer’s patch (IL PP) and papilla (PAP_IL). All piglets were <strong>in</strong>fected with S.<br />

Typhimurium.<br />

23

TABLE 1 – primary and secondary antibodies (AB) used for flow cytometry sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g*<br />

Primary AB Clone Isotype Labell<strong>in</strong>g Company<br />

CD2 MSA-4 IgG2a <strong>no</strong>ne VMRD<br />

CD4 74-12-4 IgG2b FITC Southern Biotech<br />

CD8β PG164A IgG2a <strong>no</strong>ne VMRD<br />

TcR1-N4 (δ) PGBL22A IgG1 <strong>no</strong>ne VMRD<br />

CD25 K231.3B2 IgG1 <strong>no</strong>ne Biozol<br />

IgM PIG45A IgG2b <strong>no</strong>ne VMRD<br />

Secondary AB Clone Isotype Labell<strong>in</strong>g Company<br />

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG1 pooled IgG1 APC Southern Biotech<br />

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG2b pooled IgG2b FITC Southern Biotech<br />

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG2a pooled IgG2a PE Southern Biotech<br />

* The references for each antibody are provided by the manufacturers <strong>in</strong> the datasheets.