NEWSPEAK: BRITISH ART NOW PART II EDUCATION PACK ...

NEWSPEAK: BRITISH ART NOW PART II EDUCATION PACK ...

NEWSPEAK: BRITISH ART NOW PART II EDUCATION PACK ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

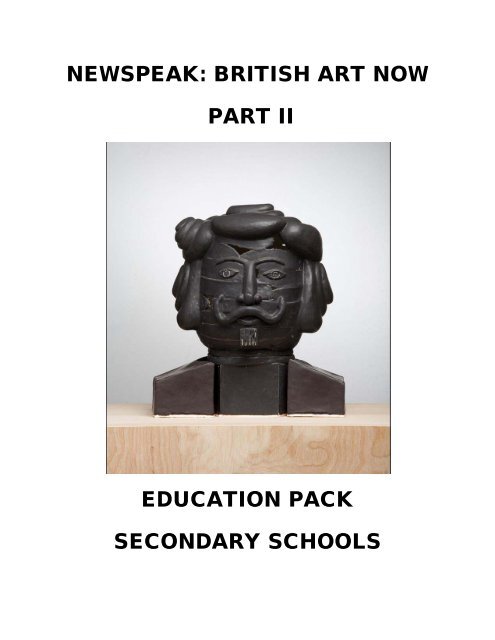

<strong>NEWSPEAK</strong>: <strong>BRITISH</strong> <strong>ART</strong> <strong>NOW</strong><br />

P<strong>ART</strong> <strong>II</strong><br />

<strong>EDUCATION</strong> <strong>PACK</strong><br />

SECONDARY SCHOOLS

1. Introduction<br />

Brief contextualization of works in the show<br />

2. Key Works<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Selected artists for this section include Juliana Cerqueira Leite Jonathan Wateridge,<br />

Tessa Farmer, Clarisse D'Arcimoles, Alexander Hoda, Maurizio Anzeri, Peter Linde<br />

Busk and Anthea Hamilton,<br />

3. Activities and Discussion Points<br />

Individual and group activities for students visiting the exhibition and topics for<br />

discussion.

INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>NEWSPEAK</strong>: <strong>BRITISH</strong> <strong>ART</strong> <strong>NOW</strong> P<strong>ART</strong> <strong>II</strong><br />

27 OCTOBER 2010 – 16 JANUARY 2011<br />

Newspeak: British Art Now Part <strong>II</strong> is the second installment of the Gallery’s museumscale<br />

survey of emergent British contemporary art, providing an expansive insight into<br />

the art being made in the UK today. Far from manifesting a visual language in decline,<br />

which the Orwellian title might suggest, the exhibition celebrates a new generation of<br />

artists for whom the stimulus of our hyper-intensified, codified, contemporary world<br />

provides a radical pathway to a host of new forms and images.<br />

From sculpture and painting, to installation and photography, artists here employ a<br />

hybrid of traditional and contemporary techniques and materials to create a new<br />

language with which to articulate the wikified world around them. In this melting pot,<br />

east merges with west, celebrity with classicism, fantasy with obsessive formalism. This<br />

explosion of new and vigorous forms is an exciting indicator of the ongoing and future<br />

strength of contemporary art in Britain.<br />

Newspeak: British Art Now - Part <strong>II</strong> features a selection of works by Alan Brooks,<br />

Alexander Hoda, Anna Barriball, Anne Hardy, Ansel Krut, Anthea Hamilton, Arif Ozakca,<br />

Caragh Thuring, Carla Busuttil, Caroline Achaintre, Clarisse D'Arcimoles, Dan Perfect,<br />

Dean Hughes, Dick Evans, Edward Kay, Gabriel Hartley, Gareth Cadwallader, Graham<br />

Durward, Graham Hudson, Henrijs Preiss, Idris Khan, Jaime Gili, James Howard,<br />

Jonathan Wateridge, Juliana Cerqueira Leite, Kate Groobey, Luke Gottelier, Luke<br />

Rudolf, Maaike Schoorel, Marcus Foster, Maurizio Anzeri, Mustafa Hulusi, Nicholas<br />

Hatfull, Nicholas Byrne, Nick Goss, Olivia Plender, Paul Johnson, Peter Linde Busk,<br />

Renee So, Robert Fry, Spartacus Chetwynd, Steve Bishop, Systems House, Tasha<br />

Amini, Tessa Farmer, Toby Ziegler, Tom Ellis, Ximena Garrido-Lecca.

JULIANA CERQUEIRA LEITE<br />

Juliana Cerqueira Leite Up 2008<br />

Plaster and acrylic polymer, polyurethane<br />

rigid foam 210 x 47 x 45 cm<br />

Juliana Cerqueira Leite Down 2008<br />

Plaster & acrylic polymer, polyeurethane rigid foam 210 x 69 x 65 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Juliana Cerqueira Leite is a Brazilian/American artist based in London. Primarily a<br />

sculptor, Juliana uses her body to investigate the ways through which intention can take<br />

physical form. Down and Up were both created in 2008 using solid blocks of clay (each<br />

210cm high by 90cm square), which Cerqueira Leite physically dug her way through.<br />

For one, Leite digs 'up', shaping the clay with her body as she goes, before making a<br />

plaster cast of the negative space; for the other, she digs 'down' – traces of knee, toe,<br />

and finger are visible, stretching the clay in apparent attempts to escape. Cerqueira<br />

Leite explores the extent to which the human body can become an artistic tool, literally<br />

performing her works into being.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

“My work is driven by an investigation into physicality and how we interact with the<br />

physical world,” says Juliana Cerqueira Leite. “For Up, I built a box that was as tall as I<br />

could reach, slightly larger than my body, and completely filled it with clay. The box was<br />

raised onto a steel platform so I could crawl under it. I dug upwards through the clay<br />

until my entire body fit inside the box and I could reach its top with my arms stretched<br />

above my head. The final piece is a plaster cast taken from the space I dug out and<br />

shows the minimum amount of space I could occupy. The wavy surface is formed by the<br />

negative grooves from the tips of my fingers pulling the clay downwards and pushing it<br />

out of the bottom of the box. The work is black because when I was inside the clay it<br />

was completely dark. I couldn’t see anything so this piece was made entirely by touch.”<br />

“The process shows me something about my body or form and the end result is always<br />

a surprise.<br />

For Down, I used the same sized box and amount of clay as in Up, but dug downwards<br />

from the top. I don’t really plan how I’ll carry out the<br />

tasks that I set myself and I thought I might dig like a<br />

dog, but discovered my body doesn’t work like that: I<br />

had to sit in the hole I was making and scoop around<br />

myself, lowering myself feet first into this space. As I<br />

got deeper I found myself using rock climbing<br />

techniques to suspend myself inside the clay. The<br />

spiral formation emerged through the subconscious<br />

movement of working in a circular way. You can see<br />

all the impressions of my knees, feet, and elbows. I<br />

cast this form in plaster, it’s one of the most readily available materials, historically so<br />

linked to sculpture and it’s important to me that it’s organic and non-toxic. The object<br />

isn’t solid but still very heavy; it’s installed as if it defies gravity.”

JONATHAN WATERIDGE<br />

Jonathan Wateridge Group Series No.2 - Space Program 2008<br />

Oil on canvas 292 cm x 390 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Jonathan Wateridge constructs scale models of his paintings, complete with ‘actors’,<br />

props and costumes. His fabricated worlds, akin to movie sets, are then painted on<br />

canvas in a style that recalls realist painters<br />

such as the 19 th century French artist<br />

Gustave Courbet, whose work A Burial at<br />

Ornans is pictured on the left. Despite the<br />

scenes by Wateridge being almost total<br />

fiction, they initially seem like<br />

documentations of real-life events.<br />

Wateridge draws on shared visual codes<br />

and cultural symbols to create an initial easy<br />

familiarity about the scenes depicted, which obscures the fictiveness of the moments he<br />

has captured on canvas. It is only after closer consideration that the viewer notices<br />

discrepancies. The artist’s works comment on how people are inundated with images<br />

today, whether through newspapers, T.V. or advertising and highlights our process of<br />

‘reading’ and often uncritically consuming images.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

“Astronauts have an almost symbolic status. They operate on the frontier of an effort to<br />

understand the unknown. They appeal to a child-like sense of awe and adventure yet<br />

are the ultimate display of a culture's economic power and political ideology. The title<br />

Space Program puts the emphasis more on earthly planning than it does the heroics of<br />

space manoeuvres. The ship is still under construction, these men are gathered in<br />

anticipation of future glory not in celebration of established deeds. Hence there's a<br />

certain tension in the gathering; there's pride but also reservation. Though you might<br />

initially believe the image, subtle but mischievous clues to the work’s fiction are<br />

introduced: for example, the milk bottle top or a mobile phone keypad on the ship;<br />

plumbing parts on the space suits; the astronauts are in fact friends dressed in<br />

costumes made in my studio. As soon as you are made aware of these elements,<br />

there's something mildly comic about the image but also darkly so in the sense that this<br />

would obviously be a completely doomed mission!”<br />

As a boy, I remember rifling through news magazines lying around the house and would<br />

see images, for example, of a gathering of politicians. I had no idea who these people<br />

were or what they were doing but somehow the images conveyed 'importance'. Even<br />

now when clearly I recognise politicians or dignitaries, they are sometimes rendered<br />

anonymous by my associative memories of the kind of picture they're in.<br />

I want the viewer to be able to buy in to the image enough to want to spend time with it,<br />

to elicit a certain level of recognition that then starts to fragment. In conjunction with a<br />

sense of fiction or fabrication, the notion of people and the 'kind of picture they're in' has<br />

become a primary concern in my work where subjects are distilled into a 'perfect<br />

memory' of the type of image represented.

TESSA FARMER<br />

Tessa Farmer Swarm 2004<br />

Mixed media Vitrine: 208.3 x 243.8 x 68.6 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Made from desiccated insect remains, dried plant roots, and other organic ephemera,<br />

Tessa Farmer’s tiny sculptures give a glimpse into the world of fairies. No sugar coated<br />

tale of Tinkerbells, Farmer’s Swarm envisions these fairies as a hybrid species of<br />

human and insect, fearsome skeletal fiends, consuming and torturing the insects<br />

swarming around them in an imagined Darwinian battle for survival. They are<br />

painstakingly hand crafted and adorned with real insect wings, standing less than 1 cm<br />

tall.<br />

The artist describes herself as being similar to a Victorian naturalist bringing a newly<br />

discovered species to public attention. Many of her tiny sculptural creatures are<br />

presented as though parts of the natural world that have yet to be classified. They’re<br />

ordinarily too small to view properly without a magnifying glass, forcing us to inspect<br />

them at close range. Presenting her ‘new’ species alongside ‘real’ flies and wasps blurs<br />

the boundaries between the fantastical and the natural, our eye accepts this fictive<br />

continuity, and reads the fairies as sensate, animate beings. In June 2007, Farmer<br />

began a residency with the Natural History Museum. Working with experts within the<br />

Department of Entomology, she devoted much of her research to the parasitic wasp,<br />

which habitually invades and devours other creatures in order to survive and prosper.<br />

This research has manifested in the narrative that she creates about her fairies who turn<br />

parasitic in later works. Her ‘narrator voice’ is wonderfully detached and scientific,<br />

creating the possibility of these works existing independently of her.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

I explore the realm of illusion and reality through sculptural manipulation of nature,<br />

weaving a fantasy drawn from literature, legends and my own imagination. I intend the<br />

work to question the limits of the viewer's imagination and instill a sense of wonder,<br />

magic and possibility. This bid to reignite childlike curiosity has witnessed the<br />

emergence of a species of miniature skeletal creatures resembling the human form,<br />

collectively named 'hell's angels and fairies’… Visually provocative they are macabre,<br />

yet strangely beautiful, combining elements of attraction and repulsion. Beautiful as they<br />

may seem to some, these are far removed from the benign gossamer beings of the<br />

Victorian era.

CLARISSE D’ARCIMOLES<br />

Clarisse d'Arcimoles<br />

Religieuse (Self-Portrait) 2009<br />

Archival inkjet print 27 x 42 cm<br />

Clarisse d'Arcimoles<br />

In The Bath (My Mother And My Sister) 2009<br />

Archival inkjet print<br />

24.5 x 35 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Clarisse d'Arcimoles presents original photographs alongside restaged versions of the<br />

same image in an attempt to reconnect with the past. Drawing from a collection of family<br />

snapshots, d’Arcimoles focuses our attention sharply on the concept of aging while<br />

ensuring a consistency of location. Fascinated with the irretrievability of the past and on<br />

photography’s strength in making memories tangible, her practice uses time as a<br />

collaborative partner, accepting its discrepancies and playing with the results. Each of<br />

these works consists of a photograph from her family album and a picture of the same<br />

person taken in 2009 in a scene that’s been exactly reproduced.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

“I called this series Un-possible retour, which means ‘a possible impossible return’,”<br />

D’Arcimoles says. “I grew up partly in French Guyana so in the photos I was re-staging,<br />

the location sometimes had changed or become inaccessible and the objects and<br />

surroundings could not always be found or re-made. But while the people had grown up,<br />

aged and changed, I could feel a certain sense of permanence in them.<br />

Un-possible retour is a way back to childhood, even if it is just for a short instant. We<br />

were all children once, and that is something that is always current within us. My work<br />

can be a game as well: you can play with the similarities and differences. By creating<br />

these kinds of comparisons, or rather confrontations, I felt like I was exploring time in its<br />

oddest form – as if there was a dialogue between the past and the present moment.<br />

Most of the photos I restage were taken in the 90s; my brother, sisters, and I were the<br />

last generation photographed with film cameras and to have family albums. Now<br />

everyone uses digital, and we don’t really print photos anymore. My project will probably<br />

have a different meaning and impact in a few years’ time because of this.”<br />

ABOUT Religieuse (Self-Portrait)<br />

“This picture of me was taken in South America on Christmas Eve; I was so happy, it<br />

was the first year I was allowed to celebrate Christmas Eve with my parents. The cake<br />

was my favourite one and still is. To achieve the photographs I had chosen, and<br />

especially the ones that pictured me as a child, I had to innovate with the relation<br />

between model and photographer. Indeed, I became the model and my inexperienced<br />

family members had to become photographers, under my instructions. Not only was I in<br />

a slightly uncomfortable position trying to reconstruct my identity as a child (both<br />

physically and emotionally) but I also had to teach my family how to use digital and<br />

manual cameras, trigger and flash kits!”

ALEXANDER HODA<br />

Alexander Hoda Pile Up 2008<br />

Polystyrene, latex, resin, rubber, found objects 345 x 248 x 205 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Alexander Hoda makes his sculptures by assembling found objects into a coherent<br />

unified form and then coating the entire surfaces with rubber. His figurative groupings<br />

suggest animals chained together or melting into each other. These fantastical beasts<br />

are driven by base needs such as mating, suckling or nurturing. There is a strong<br />

element of the grotesque and the abject in these works, whilst the artist also draws on<br />

classical sculpture for inspiration.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

“Pile Up was inspired by a knick-knack I bought on eBay, a stack of pigs piled one on<br />

top of the other; a bizarre but appealing thing. It was like they were emerging out of one<br />

form. I had also just visited the Uffizi in Florence where I saw Michelangelo’s<br />

The Captives, (shown left) a series of studies he made where only partial<br />

elements of figures appear emerging from stone blocks. I wanted to explore<br />

the relationship between these two references. There’s a sexual insinuation in<br />

the way the rubber gives an initial binding of the figures, a uniform coating, but<br />

also violence in enhancing the dynamics between the forms. With traditional<br />

figurative sculpture an artist literally hacks away at something to create or<br />

destroy a figure; sculpture is violent. Sculpture is a bodily experience, you are<br />

confronted by an object that inhabits the same space as you do.”<br />

“For Shoehorn (shown right) I wanted to have more of a scene, like the narratives within<br />

classicism and mythology, but my own. It’s like a freeze-frame<br />

of a moment… This is a way to ‘dress up’ the objects, to make<br />

them re-perform in a different environment, re-contextualise<br />

them with new meanings. The found objects and masks<br />

underneath the surfaces give the effect of an inflatable object<br />

that’s almost expanded to the point of collapse. In my work I<br />

am exploring relationships, desires, and urges, to perceive<br />

them in different contexts rather than something that’s<br />

conditioned to be guilt-laden or perverted.”

MAURIZIO ANZERI<br />

Maurizio Anzeri, Penny, 2009<br />

Embroidery on found photograph 24 x 13 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Maurizio Anzeri's obsession with found photographs taken from family albums began<br />

when he started visiting cemeteries in Italy and thinking about headstones as the last<br />

trace of the dead. Anzeri works with discarded portraits, which he brings back into<br />

existence with exquisite embroidery. A celebration of forgotten lives, his works are both<br />

beautiful and unnerving.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

The intimate human action of embroidery is a ritual of making and reshaping the stories<br />

and history of these people. I am interested in the relation between intimacy and the<br />

outer world<br />

I’ve been collecting old photographs for a long time. A few years ago I was doing ink<br />

drawings with them and out of curiosity I stitched into one. I work a lot with threads and<br />

hand stitching, and the link to photography was a natural progression. I put tracing<br />

paper over the photo and draw on the face until it develops. Sometimes the image<br />

comes straight away, suggested by a detail on a dress or in the background, but with<br />

the majority of them I spend a lot of time drawing. Once the drawing is done, I pierce the<br />

photo with a set of needle-like tools I invented and take the paper away; the holes are<br />

obsessively paced at the same distance to convey an idea of geometry. When I begin<br />

the stitching something else happens, drawing will never do what thread will – the light<br />

changes, and at some points you can lose the face, and at others you can still see<br />

under.<br />

There’s a dynamic in what happens between the photograph, the embroidery on top,<br />

and you standing in front looking at it. There are no rules other than I always leave one<br />

or both eyes open. Nothing is bigger than a face, it’s the best landscape we can look at.<br />

Like a costume, my work reveals something that is behind the face that suddenly<br />

becomes in front. It’s like a mask – not a mask you put on, but something that grows out<br />

of you. It’s what the photo is telling you and what you want to read in the photos. I get<br />

my ideas from many different sources: it could be theatre, or someone dressed up on<br />

the tube, a tribe in Papua New Guinea, or Versace. It’s never one specific thing.”<br />

Photographs from the 40s and 50s have a totally different quality from photos we’re<br />

used to today. We don’t recognise them as photographs now, they really look like<br />

watercolours or drawings. The images I use are anonymous, I find them everywhere;<br />

I’m really into flea markets and car boot sales, when you enter you have no idea what<br />

you’re going to encounter. Art history is very important to me, it’s all been done before<br />

but it’s never been done by you: if you don’t look into the past there is no chance to go<br />

into the future. The surrealist movement is important to my work, but I don’t become<br />

obsessed by it, it’s not dictating rules. I understand history in a formal respect, and think<br />

of past artists like travelling companions – making work is like going for a walk with<br />

them. At the end of the day it’s about humanity.

PETER LINDE BUSK<br />

Peter Linde Busk Great Perfected Being 2009<br />

Acrylics on linen 124 x 78 cm<br />

Peter Linde Busk<br />

And That Was The End Of The Singer And<br />

The Song 2010<br />

Acrylic, crayons, colour pencils on cotton duck<br />

canvas 175 x 110 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Danish-born Peter Linde Busk uses patterns, hatching and other systematic techniques<br />

to conceal or reveal a human-like form. His portraits evoke mental states, including<br />

melancholy, despair, fear, defeat and even insanity. Linde Busk was influenced by the<br />

COBRA movement, alongside outsider art, folk art and from literature, representations<br />

of the anti-hero.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

For some reason Great Perfected Being reminds me of The Notebooks of Malte Laurids<br />

Brigge by Rilke. I read this book while I was living in Paris for a month doing all the<br />

bohemian things a young artist does in Paris. I remembered Malte describing a man he<br />

encounters in the street on his walks around the city. This man has the most violent tics;<br />

his whole body jumps and his posture becomes distorted by the onslaught of these<br />

uncontrollable cramps. But still he tries to keep up his appearance. The distorted figure,<br />

as a way of expressing or signifying dysfunctional inner workings, is a key feature in my<br />

work. It also reminds me of Egon Schiele (I’m not sure that’s a good thing though) and a<br />

photograph I once saw by Josef Koudelka of a gypsy playing the violin. The character in<br />

the painting also appears to play the violin, only he doesn’t have one.”<br />

“I painted the background for And That Was The End Of The Singer And The Song in a<br />

very long session one night and then left it sulking in the corner of my studio until I did<br />

the black drawing on top. The figure looks a bit like a<br />

falling angel, or a dandy. I was probably thinking about<br />

an etching I had done and maybe Peter Doig’s<br />

incredible painting Man Dressed As Bat (shown left).<br />

The title is a quote from Verlaine. He wrote a poem<br />

about the rise and fall of Rimbaud, about how his genius<br />

and ambition led to arrogance and stubbornness and in<br />

the end to his decline. This was the first time I used a<br />

new gesso which is very matt, coarse and absorbent<br />

and I like the occasional watercolour-like effect which<br />

occurs. As with all my other paintings the area<br />

surrounding the character is very important. It’s not so much a space as an atmosphere,<br />

a mood I want to achieve where the character belongs, emerges from, or is subdued in.”

ANTHEA HAMILTON<br />

Anthea Hamilton The Piano Lesson 2007<br />

Mixed media 200 x 500 x 400 cm<br />

Anthea Hamilton The Waitress 2008<br />

Mixed media (wood, bread, clamp, rope, apricot, paint) 160 x 250 x 120 cm

ABOUT THE <strong>ART</strong>IST<br />

Hamilton creates her Dadaesque installations from impermanent materials such as fruit<br />

and more durable media such as wood. Her compositions reference art history and pop<br />

culture in diverse ways. She has described her sculptural installations as ‘performative<br />

spaces’ and there is a strong sense of theatricality in the works, which appear like sets<br />

inviting the viewer to take ‘centre-stage’. An often repeated motif is that of the cut-out<br />

leg – modeled on her own – which recalls the provocative playfulness of cabaret,<br />

drawing on the leg in its iconographic role as fetish object, whilst serving as a type of<br />

‘artist signature’ or self-portrait.<br />

<strong>ART</strong>IST STATEMENT<br />

“I was remaking film extracts of well-known Hollywood movies,” Anthea Hamilton says,<br />

“and these pieces, such as The Piano Lesson, started life as props. I wanted to make<br />

my own narratives, and the objects had a successful enough sense of movement or<br />

animation in themselves to render the need to make the film unnecessary. They<br />

suggest sets and characters, the cinematic or theatrical and are always composed to be<br />

seen from the front just as you would see a stage set. My work hints at particular eras,<br />

it’s not old-fashioned, but not contemporary either;<br />

they’re in their own time. This piece was particularly<br />

inspired by Fernand Leger’s 1921 painting Le Grand<br />

Déjeuner, (shown left) the large feminine wavy form<br />

is taken directly from the shape of the women’s hair.<br />

Borrowing from an artist’s palette offers a method for<br />

a rich, chromatic display. I was looking at basreliefs,<br />

architecture or ancient Egyptian cartouche<br />

characters and hieroglyphics: they look like pictures,<br />

but are conveying specific information.”<br />

“When it was originally exhibited The Waitress was made to be a backdrop for two other<br />

pieces I made. At the time I was looking at artists including Matisse, Calder, Gris, and<br />

Picasso’s later work. The guitar shapes look like a woman’s body, and also reference<br />

Cubist still life painting. Blue, like the cut-out leg, is a recurrent motif in my work. It’s the<br />

kind used for special effects in film and television. I don’t really like showing my work in<br />

conventional looking gallery spaces as it’s too removed from real life and the idea is that<br />

blue-screen blue is even more invisible or neutral than a white cube. I try to display the<br />

practical elements in my work: the clamps, for example, allow the viewer to see exactly<br />

how things are made, there’s no tricks. The composition looks like a woman lying on her<br />

side; her private parts are suggested by decorative pepper shakers, dried apricots and a<br />

German laugenbrot. I like using things that will perish; it gives a tempo to the work.”

ACTIVITIES FOR YOUR VISIT<br />

Below are some activities you can do in response to the exhibition. More<br />

activities are available to download from the website if you visit the schools<br />

section online<br />

Juliana Cerqueira Leite<br />

At the gallery:<br />

Ask students to sketch parts of the work, focusing on areas where they can see the<br />

physical traces of the artist’s body<br />

At school:<br />

Use plaster and alginate to create imprints of hands and feet. Below is an example of<br />

how this can be done.<br />

Jonathan Wateridge<br />

At the gallery:<br />

Ask students to study the work and point out discrepancies that reveal the fabricated<br />

nature of each image (e.g. milk bottle tops)<br />

At school:<br />

Students can create their own scenes using props, with friends posing in a tableau –get<br />

them to ‘freeze-frame’ in a few different poses and take some photographs of the<br />

various moments depicted. Then ask students to paint the fabricated scenes from the<br />

photographs taken.

Tessa Farmer<br />

At the gallery:<br />

Ask students to write two texts on Swarm; one using a scientific tone of voice to<br />

describe the creatures and the other using imaginative language to describe the world<br />

in which this hybrid species exists<br />

At school:<br />

Students can create their miniature species from leaves, or pom<br />

poms, pipe cleaners, googly eyes, twigs and anything else that<br />

comes to hand, to create their own “fairy world”. You could then<br />

hang them from some sort of frame using cotton to make them “fly”.<br />

Clarisse d'Arcimoles<br />

At the gallery:<br />

Ask students to study these images and describe how the person depicted has changed<br />

and whether any of the objects in the restaged snapshot differ from the original. Then<br />

ask them to draw a self portrait, followed by a portrait of themselves as imagined in the<br />

future. Ask them to think about objects in the image (walking stick? paint brush?) and<br />

whether they would be seated or standing, at work or relaxing somewhere<br />

At school:<br />

Ask students to bring in their own family snapshots and corresponding props. Recreate<br />

these images by restaging and photographing them. Or ask them to paint self-portraits<br />

in the present and as imagined in the future.<br />

Maurizio Anzeri<br />

At the gallery:<br />

Ask students to study these works and describe how the act of embroidery changes<br />

each image. They can then draw coloured lines over the below images if you print these<br />

out (on the next page)<br />

At school:<br />

Print out images of old photographs on quite thick paper. Cover these print outs with<br />

tracing paper. Students can design a pattern over the image on the tracing paper, and<br />

then use embroidery thread and a needle to pierce through the tracing paper, before<br />

embroidering directly onto the print outs. They can create their own versions of this work<br />

by doing so.

DISCUSSION POINTS<br />

CHOOSE YOUR FAVOURITE <strong>ART</strong> WORK<br />

1. Which work have you chosen? (title, name of artist, media used)<br />

2. What is the art made from?<br />

In this show artists have used a range of materials from found objects to rubber<br />

or embroidery– how do these materials impact the meaning of the work? The<br />

choices made by the artist reflect the kind of ideas they want to portray.<br />

3. What is the artwork about?<br />

Some art is intended to provoke a response or highlight certain issues. For<br />

example, Jonathan Wateridge creates fabricated scenes, Clarisse<br />

D’Arcimoles re-stages her family album -– how can we think about time and<br />

memory in relation to these works?<br />

4. If you could hang 3 works together in one room from this show, which<br />

works would you choose?<br />

Why would you choose to put them together – what links would you draw<br />

between the works? Might they address similar issues? Or share artistic<br />

techniques? Or look good formally when hung near each other (i.e. on a<br />

purely visual level)?