Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ecology<br />

farming<br />

IFOAM<br />

nr 1 // February 2011<br />

SEEDS<br />

FROM<br />

INDIA<br />

AND<br />

Yes, Organic<br />

can feed the world!<br />

<strong>But</strong> <strong>how</strong>?<br />

BUY<br />

DIFFERENT<br />

BUY 7IN1<br />

ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011<br />

1

FEBRUARY 2011 // NR 1<br />

mArket & economy<br />

12 Green banking<br />

Triodos bank’s trade finance for organic<br />

and fair trade export projects<br />

23 Coffee economics<br />

Some figures from the market and<br />

the chain<br />

educAtIon<br />

14 Schoolgardens<br />

Organic schoolgardens in Ghana<br />

are used as farmer field schools,<br />

and to feed the children<br />

28 Trainees on organic farms<br />

LOGO invites young people from<br />

Eastern Europe to do scholarships<br />

in organic farming<br />

IfoAm Issues<br />

16 The organic movement meets in<br />

South Korea<br />

The 17th IFOAM Organic World<br />

Congress will be held in Korea in<br />

September.<br />

country-reports<br />

8 The first Russian organic<br />

products chain<br />

Marina Goldinberg reports on chain<br />

development in Moscow Oblast<br />

food securIty<br />

18 How can organic feed the world?<br />

The theme of the BioFach Congress.<br />

IFOAM director Markus Arbenz<br />

explains <strong>how</strong> organic agriculture<br />

can feed the world’s growing<br />

population<br />

Agro-bIodIversIty<br />

30 Breeding for resilience<br />

How to breed robust, more stress<br />

tolerant cultivars in organic<br />

agriculture<br />

stAndArds &<br />

certIfIcAtIon<br />

34 Ecosocial<br />

A certification system In Latin<br />

America integrates organic<br />

standards with environmental,<br />

social and economic goals<br />

44 The IFOAM OGS<br />

Draws the line between what is<br />

organic and what not<br />

InnovAtIon In AgrIculture<br />

24 Organic greenhouses<br />

Mike Nichols from New Zealand travelled to<br />

Europe for a workshop and opens a debate<br />

about which system to choose: aquaponic or<br />

growing in the soil?<br />

Table<br />

of Con<br />

tents<br />

country reports<br />

37 Russia<br />

Short report about biodynamics<br />

in Russia<br />

42 Iran<br />

Rapid development of organic<br />

production after a difficult start<br />

orgAnIc & heAlth<br />

39 Buy ‘Seven in One’<br />

Food choice is one of the tools for<br />

supporting sustainability<br />

46 Seed, the life line<br />

Vanja Ramprasad report from India<br />

about the real green revolution<br />

And more....<br />

Editorial 5<br />

News 6<br />

Calendar 49<br />

Preview next issue 50<br />

2 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 3

World leader in seed for<br />

organic outdoor vegetables<br />

• Breeding<br />

• Seed production<br />

• Processing<br />

• Sales<br />

For the organic market<br />

Bejo Zaden B.V. • (+31) (0) 226 396 162 • www.bejo.com<br />

Working<br />

Working<br />

with<br />

with<br />

Nature<br />

Nature Nature Nature Nature Nature<br />

At different times<br />

In different places<br />

Bejo, a name that stands for quality<br />

Nuremberg, Germany<br />

16-19 February 2011<br />

hall 5, stand 114<br />

More information<br />

about our organic seed<br />

programme?<br />

www.bejo.com<br />

Denise Godinho Peter Brul<br />

Innovation & inspiration<br />

It is not a coincidence that the re-launch of Ecology &<br />

Farming is timed to coincide with BioFach 2011; the<br />

theme of this fair is also the title of our feature article in<br />

which we ask, “Yes, Organic can feed the world!<br />

<strong>But</strong> <strong>how</strong>?”<br />

The high level of attendance at BioFach in 2010, a<br />

year of economic crisis, with 43,669 organic trade visitors<br />

from 121 countries and 2,557 exhibitors from 87<br />

countries – indicates that there is enough passion in<br />

the organic world to feed the world. In this edition, the<br />

article by Markus Arbenz, IFOAM’s Executive Director,<br />

explores the ways in which organic produce can nourish<br />

the world and the challenges that we face on the<br />

way to achieving food security.<br />

Taking place every February, BioFach is certainly the<br />

place to do business, but it is also a celebration, an<br />

organic party, where people get inspired by what the<br />

organic industry s<strong>how</strong>s and shares together. At this<br />

BioFach we will also be celebrating the re-launch of<br />

Ecology & Farming: Over the last months a number of<br />

organic allies have dedicated their personal time and<br />

made in-kind and financial investments in order to<br />

breathe life back into IFOAM’s flagship publication. We<br />

firmly believe that it is a project worth fighting for and<br />

are happy to be now able to offer readers this first, now<br />

bi-monthly, 2011 edition of Ecology & Farming.<br />

As you look through this magazine, you will find contrasting<br />

stories from around the globe that cover the<br />

organic food chain from field to fork. The innovative<br />

School Garden Project (OSGP) in Ghana sets up organic<br />

school gardens that produce fruits and vegetables<br />

for the daily meals of schoolchildren. Creating synergies,<br />

these school gardens also serve as demonstration<br />

plots for Farmer Field Schools, where local farmers<br />

learn <strong>how</strong> to make compost and to farm organically.<br />

In India, the Foundation for Genetic Resource Energy,<br />

Ecology and Nutrition (GREEN) works with small and<br />

marginal farmers to preserve endangered species,<br />

varieties and breeds, through community seed banks<br />

and organic agriculture. Instead of prioritising productivity<br />

(to the detriment of genetic diversity) organic<br />

farmers use (and build) biodiversity by breeding crop<br />

varieties for quality, nutrition, resistance and yield.<br />

These are but two examples of the many stories that<br />

actors from all over the globe have to tell. They echo<br />

the full diversity of the organic movement which IFOAM<br />

represents. The organic industry is a very innovative<br />

movement. Around the world farmers, market gardeners,<br />

agronomists, traders, food processors and others<br />

face challenges and problems for which they find their<br />

own solutions. Ecology & Farming aims to continue<br />

to document these innovations in organic agriculture,<br />

developments in markets, and ways of cooperating<br />

so as to strengthen the organic movement in different<br />

places. It hopes to inspire professionals all over the<br />

world to pick up on new ideas and to develop their own<br />

solutions. We invite you to join us on our journey across<br />

the organic world!<br />

We hope you enjoy reading this first new issue and that<br />

you will be inspired to become a regular subscriber. If<br />

you have a story that you would like to share with us,<br />

we would be happy to hear from you.<br />

ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011<br />

introduction<br />

5

DENMARK<br />

Denmark is a small country, but it<br />

is a big player in the organic world.<br />

It has the highest per capita sales<br />

of organic products of any country<br />

in the world, at €138 per person per<br />

year. Sales of organic products in<br />

Denmark continued to rise again<br />

in 2010, despite the recession. One<br />

major reason for this success is the<br />

cooperation that exists between the<br />

organic sector and the main retailers.<br />

According to Henrik Hindborg, Marketing<br />

Manager at Organic Denmark,<br />

this is because consumers continue<br />

to search for quality products that<br />

are healthy and take animal and<br />

environmental protection aspects into<br />

// ORGANIC TEXTILES<br />

Bolstered by continued strong<br />

manufacturer demand even during recessionary<br />

times, organic cotton continued<br />

its steady growth in 2009-2010,<br />

according to the fifth annual Organic<br />

Farm and Fibre report by the Textile<br />

Exchange, the leading global organic<br />

cotton and sustainable textiles nonprofit<br />

organisation (formerly known<br />

as Organic Exchange). According to<br />

the report, production of organic cotton<br />

rose by 15%, from 209,950 metric<br />

tonnes (MT) in 2008-09 to 241,276<br />

MT (just over 1.1 million bales).<br />

Organic cotton now represents 1.1<br />

% of global cotton production and<br />

organic cotton was being grown on<br />

461,000 hectares in 2009-2010. There<br />

has been a veritable explosion in the<br />

production of global organic cotton<br />

in the last four years (a 539 % increase)<br />

since 2005-06, when only 37,000<br />

MT were produced. The organisation<br />

anticipates similar strong growth this<br />

year.<br />

With Tajikistan recently entering<br />

the market, organic cotton is now<br />

grown by approximately =274,000<br />

farmers in 23 countries in 2009-2010<br />

(up from 22 countries in 2008-09).<br />

India remained the top producing<br />

nation for 2009-10 for the third year<br />

account and the retailers recognise<br />

this. Highly educated people spend<br />

more than 20% of their food budget<br />

on organic produce, compared to the<br />

national average of 7.6 %. Organic<br />

products sell best in large cities like<br />

Copenhagen.<br />

This strong position is partly related<br />

to Denmark’s strong position track<br />

record in research into organic agriculture.<br />

In September 2010, the Danish<br />

Food Industry Agency received<br />

50 applications for its organic research<br />

and development programme:<br />

the applications exceeded the available<br />

funding (€12 million) by a factor<br />

of four. The final programme is a<br />

in succession, growing over 80 % of<br />

the organic cotton produced globally<br />

and increasing its production by 37<br />

% in the past year. Syria moves from<br />

third into second place, swapping<br />

places with Turkey. The other remaining<br />

countries (in descending order)<br />

are: China, United States, Tanzania,<br />

Uganda, Peru, Egypt, Mali, Pakistan,<br />

Burkina Faso, Israel, Benin,<br />

Paraguay, Greece, Tajikistan, Senegal,<br />

Nicaragua, South Africa, Brazil,<br />

and Zambia.<br />

According to LaRhea Pepper, Textile<br />

Exchange senior director, “Manufacturers,<br />

retailers and consumers, and<br />

most importantly, farmers, have all<br />

signalled their continued interest in<br />

supporting organic cotton production<br />

and the risks that came with it despite<br />

the recession.” She continued: “In<br />

addition, the strong growth is an indication<br />

of the work Textile Exchange<br />

is doing with brands and retailers<br />

that have strong strategic plans and<br />

engagement all the way to the farm.”<br />

Liesl Truscott, Textile Exchange farm<br />

engagement director and the lead<br />

author of the report, notes that the<br />

organic cotton sector cannot rest on<br />

its laurels despite the rapid growth.<br />

“As organic cotton grows in volume,<br />

combination of projects with a short<br />

term focus on integrating product<br />

development and longer term goals<br />

of knowledge building and dissemination<br />

about primary production,<br />

processing and marketing. A number<br />

of the projects contain elements for<br />

commercializing products and have<br />

market-oriented initiatives. Others<br />

are directed more towards primary<br />

production. All the selected projects<br />

have a strong focus on practical application<br />

through linking research,<br />

development and demonstration, and<br />

direct involvement of the stakeholders<br />

as partners in projects. More<br />

about the programme can be found at<br />

www.icrofs.org.<br />

we must continue to strengthen integrity<br />

in production, certification, and<br />

processing”.<br />

All 2008-2009 all the stocks of organic<br />

cotton were purchased as has<br />

most of the current year’s crop. As<br />

such, “brands interested in nailing<br />

down their supply need to build organic<br />

cotton supply security into their<br />

planning strategies now, preferably<br />

by implementing forward contracts,”<br />

stressed Truscott. According to the<br />

organisation’s Organic Cotton Market<br />

Report 2010, global retail sales<br />

of organic cotton and home textile<br />

products topped 4.3 billion US$ in<br />

2009. Data from the 2010 market will<br />

be available this spring and reported<br />

in Ecology and Farming.<br />

// SOLUTIONS FOR<br />

SALINIZATION?<br />

There is as much brackish water in<br />

the world as fresh water, both account<br />

for just around 1 % of the total<br />

volume of water on earth. There are<br />

1.5 billion ha of saline land which<br />

cannot be used for agricultural purposes.<br />

And 20% of the 230 million ha<br />

of irrigated land in arid and semi-arid<br />

areas is affected by increased salt<br />

content of the soil and /or water. This<br />

salinization is often irreversible. There<br />

is increasing competition for fresh<br />

water and with a growing world population<br />

this is only likely to increase.<br />

The challenge is to find ways of using<br />

more brackish water in agriculture<br />

// GLOBAL SALES OF<br />

ORGANIC FOOD AND<br />

DRINK RECOVERING<br />

The global market for organic food<br />

and drink is recovering from the<br />

financial crisis. After several years<br />

of double-digit growth, the market<br />

expanded by just 5 percent in 2009.<br />

Healthy growth rates are resuming<br />

as the ‘mainstreaming’ of organic<br />

products continues. A major driver<br />

of market growth in all geographic<br />

regions is increasing distribution by<br />

mainstream retailers.<br />

The European market for organic<br />

food and drink was the most affected<br />

by the financial crisis. Declining consumer<br />

spending power and the rationalisation<br />

of organic product ranges<br />

by food retailers caused the UK<br />

market to contract in 2009. The German<br />

market, the largest in Europe,<br />

s<strong>how</strong>ed no growth. However in some<br />

countries - including France, the Netherlands<br />

and Sweden - the organic<br />

market s<strong>how</strong>ed resilience, expanding<br />

and to find solutions for salizination.<br />

Salt tolerant crops might have a<br />

potential for the production of food,<br />

oils and energy. For many years Marc<br />

van Rijsselberghe has been working<br />

on organically producing salt tolerant<br />

crops on the Dutch island of Texel.<br />

He produces a range of food crops<br />

and wellness products. As an expert<br />

in producing and marketing these<br />

typical crops, he has just received a<br />

grant of € 2.5 million for research<br />

on the salt tolerance of crops. The<br />

research will be undertaken with<br />

experts from several universities. The<br />

next issue of Ecology and Farming<br />

will carry more about salt tolerant<br />

crops.<br />

by over 15 percent.<br />

Healthy growth is continuing in the<br />

North American market, which this<br />

year has overtaken the European<br />

market to become the world’s largest.<br />

Supply continues to fall short<br />

in many organic product categories,<br />

leading to imports from various<br />

countries. Latin America has become<br />

a major source of organic fruits,<br />

vegetables, meats, seeds, nuts and<br />

ingredients.<br />

The fresh produce category comprises<br />

most organic food and drink<br />

sales. Fruit and vegetables such as<br />

apples, oranges, carrots and potatoes<br />

are typical entry points for consumers’<br />

first organic purchases. Their<br />

fresh nature appeals to consumers<br />

seeking healthy and nutritious foods.<br />

Dairy products and beverages are the<br />

next most important organic product<br />

categories.<br />

The 3rd edition of the Global Organic<br />

Food and Drink Market Report<br />

gives a detailed analysis of the<br />

Exci<br />

ting<br />

News<br />

market for organic products in each<br />

geographic region. Regional reports<br />

contain information on market size,<br />

revenue forecasts, market drivers and<br />

restraints, regulations and standards,<br />

category analysis, sales channels<br />

breakdown, consumer behaviour,<br />

competitive analysis, retailer profiles<br />

and business opportunities.<br />

The report is a result of almost ten<br />

years of continuous research into the<br />

global organic food industry. Expert<br />

analysis and insights are provided<br />

to inform key business decisions<br />

and marketing plans. Future growth<br />

projections are given in terms of<br />

organic food production, market<br />

growth rates, and industry developments.<br />

Business opportunities in each<br />

geographic region are highlighted<br />

for the benefit of new entrants and<br />

exporters.<br />

Source: Organic Monitor: The global<br />

market for organic food and drink<br />

(December 2010)<br />

6 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 7

The Organic Corporation is the only player in<br />

Russia involved in the whole organic cycle:<br />

from production to retailing.<br />

The first Russian<br />

organic products chain<br />

by Marina GoldinberG<br />

Russian lifestyles are becoming less different from European ones. A healthy<br />

lifestyle, proper nutrition and environmental concerns are changing from<br />

being “fashion trends” into a way of life, at least in the bigger cities. The<br />

history of organic production in Russia is being written before our eyes.<br />

However, at present, one can hardly call it a triumphal story. The organic<br />

entrepreneurs, who have bet on increasing demand for healthy food, have<br />

gone through many disappointments.<br />

One of the challenges was low awareness among<br />

Russians about what organic produce is. According<br />

to experts, strong government support in agriculture,<br />

public education and training will be required<br />

in Russia to foster the development of organic sector.<br />

Also a uniform Russian organic standard needs to be<br />

established.<br />

Currently there is only one project in Russia that is<br />

involved in the full cycle of organic production - the<br />

Organic Corporation. It was founded in 2006 with the<br />

aim of developing the organic market in Russia. The<br />

corporation aims at promoting a careful and conscious<br />

attitude towards the health of the Earth and its people,<br />

to improve people’s physical and spiritual health and<br />

the ecological balance. Promoting organics is one of<br />

achieving this and encouraging people to share responsibility<br />

for the present and future. At present, the Organic<br />

Corporation has three main business areas: a distribution<br />

company, agricultural production and processing<br />

and a network of specialized stores.<br />

The Bio-Market stores are currently the only chain in<br />

Moscow with a complete range of organic products<br />

(more than 3,500 items). Some of the national chain<br />

supermarkets do have shelves with organic products,<br />

but their range is very limited; often just juices and groceries.<br />

This limited selection does not meet demand<br />

and cannot provide a proper balanced diet. People<br />

also need dairy products, fruits and vegetables. From<br />

the very beginning Bio-Market stores have carried a<br />

full range of organic products - including food, cosmetics,<br />

domestic items and products for children and the<br />

family. One of the objectives was to create a special<br />

atmosphere, emphasizing that “organic” is not just a<br />

label but a lifestyle. To support this idea, the interiors<br />

of the shops are made out of natural materials and<br />

decorated in sunny orange colours. Environmental<br />

friendliness is on display everywhere: for example, the<br />

shoppers are offered wicker baskets and cloth-bags.<br />

Bio-Market sales consultants are conversant with all the<br />

nuances of organics and eagerly share the secrets of<br />

a healthy lifestyle with the shoppers. One of the main<br />

attractions is a chocolate machine, in the centre of<br />

the floor space, where chocolatiers make chocolates<br />

from Belgian organic chocolate with a choice of fillings<br />

including praline, marzipan and marmalade. There is a<br />

The interiors of the shops are made out of<br />

natural materials and decorated in sunny<br />

orange colours.<br />

bakery with wooden mills, where grain is ground into<br />

flour on demand. In addition, the store on the Rublevsky<br />

Highway has a pleasant bio-cafeteria, where chefs<br />

cook both traditional Russian dishes (including the<br />

famous beetroot soup, Kiev cutlets, salad, coated herring,<br />

etc.) and European meals using organic products.<br />

The stores are taking on the feel of family clubs, where<br />

people come with their children and friends, to spend<br />

half a day in master classes or tasting sessions.<br />

In order to give people the opportunity to not only<br />

understand, but also feel, what organic products are<br />

Bio-Market regularly holds tasting sessions and culinary<br />

master-classes with chefs, confectioners and chocolatiers.<br />

Those who wish to try organic make-up can get a<br />

makeover at a beauty shop at the same store.<br />

Bio-Market stores also stage a variety of thematic<br />

events: “Perfect Health Days”, “Children’s events” (with<br />

entertainers), tea ceremonies, and a “Christmas Fair”.<br />

country-reports<br />

8 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 9

Bio-Market also has a number of nutritionists, ayurvedic<br />

doctors, paediatricians and other alternative health<br />

experts who are available for consultations. Bio-Market<br />

pays special attention to children: in the cafeteria there<br />

is a special menu for children and the store regularly<br />

has puppet s<strong>how</strong>s and parties during which Bio-Market<br />

staff involve children in making pastries, drawing pictures,<br />

doing origami, colouring chocolate bars with edible<br />

paint and making candies. Some buyers trust the store<br />

staff so much that they leave their children under the<br />

supervision of the animators for hours! In 2011, the<br />

company plans to launch an eponymous internet shop.<br />

However, retailing is not the only activity of the Organic<br />

Corporation but is the tip of the larger iceberg of the<br />

“full cycle of organic produce”. The Corporation aims<br />

to establish the first unique production chain in Russia,<br />

running from the seed to the counter. To this end the<br />

Organic Corporation has its own organic farm (Spartak,<br />

located near Moscow) with its own production and<br />

processing facilities and a distribution branch (the Ecoproduct<br />

Trading House).<br />

The Organic Corporation’s farm began conversion in<br />

2006, more or less from scratch. In 2010 the farm was<br />

certified by the Swiss certifier Bio Inspecta. Pest control<br />

is done solely by biological and physical methods.<br />

Much of the work is done manually, so as to not cause<br />

harm to the plants and soil. The farm has a number of<br />

cattle, which are allowed to graze freely in the summer,<br />

although because of the weather, the livestock is kept<br />

indoors during the winter. The organic standards, in<br />

terms of the area per head of cattle, are fully observed.<br />

The cattle are fed with organic roughage and concentrates,<br />

produced on the farm.<br />

The use of any hormones is strictly prohibited on the<br />

farm. Any livestock with a disease is kept apart from<br />

healthy animals, and treated with homeopathic and<br />

other natural remedies whenever possible. To preserve<br />

nutritional quality, the raw materials are processed as<br />

gently as possible. Chemical refining and deodorization,<br />

hydrogenation, irradiation, genetically modified<br />

ingredients and chemical and synthetic substances are<br />

completely banned.<br />

Swiss colleagues provided a good deal of assistance in<br />

helping develop the Spartak organic farm. At the beginning<br />

of the transition period to organic farming, a few<br />

organic farming specialists from Switzerland were invited<br />

to bring their expertise and to work in the company.<br />

Despite the vast differences with the Western European<br />

farms with which they were familiar, these new colleagues<br />

had no doubts about the potential of Spartak.<br />

And, despite the language barrier, mutual understanding<br />

and fruitful cooperation with the farm’s employees<br />

was surprisingly quickly reached.<br />

One of the key issues that had to be addressed was<br />

that of organic certification. In February 2008 in Nuremberg<br />

(Germany) during BioFach, the world’s largest<br />

international fair of organic products, the Organic Corporation<br />

reached an agreement on organic certification<br />

with the renowned Swiss company Bio Inspecta. Based<br />

on the agreement, the representatives of Bio Inspecta<br />

have regularly supervised all the activities taking place<br />

on Spartak’s premises; inspecting every stage of production<br />

- seeds, agricultural land and farming techniques,<br />

storage, processing and packaging. The inspectors<br />

carefully examine not only fodders and fertilizers,<br />

but any bag or other container that they may find on<br />

the farm. At the end of July 2009 an end of conversion<br />

inspection was carried out and resulted in the issuing of<br />

an international certificate of conversion, approving the<br />

organic status of Spartak farm and its dairy and vegetable<br />

products.<br />

In the summer of 2010, the first line of Russian organic<br />

dairy products, sold under the brand name EtoLeto<br />

– milk, yogurt, sour cream and cottage cheese - first<br />

appeared on the shelves of Moscow stores. The entire<br />

line of EtoLeto products is packaged in glass bottles,<br />

which better preserve the high quality of the product,<br />

are easy to use and are recyclable.<br />

The distribution business of the Organic Corporation,<br />

the Eco-product Trading House, plays an important role<br />

in developing the organic market in Russia. Its main<br />

objective is to increase the range of organic produce<br />

available in Russia and to make organic products available<br />

for people with an average income. Currently,<br />

the product range of the Eco-product Trading House<br />

includes more than 1,500 items, covering all commodity<br />

groups - imported foods, cosmetics, household items<br />

and the Corporation’s own produce. Since European<br />

producers are major suppliers of organic products to<br />

the Russian market, the warehouse of the company is<br />

located in Germany, which allows a fast response to<br />

changes in demand, and allows the import of goods in<br />

the required quantities in the shortest possible time. All<br />

the imports of products are carried out in strict compliance<br />

with Russian laws.<br />

One of the most important issues for the Organic Cor-<br />

poration is the question of the involvement of staff at<br />

all levels in the common cause and their adherence to<br />

basic principles of the Corporation: Health, Environment,<br />

Care and Fairness. Before starting work, every<br />

employee must learn about organic standards, the<br />

characteristics of organic production, the product range<br />

and become familiar with the company’s philosophy.<br />

The manufacturers of organic products often organize<br />

workshops and master-classes. Regular company<br />

visits are organised to the Spartak farm, allowing every<br />

employee of the Corporation the opportunity to have<br />

personal contact with organic farming and the livestock<br />

whose milk they sell. The Organic Corporation has<br />

seconded its employees to the organic enterprises in<br />

Europe and Canada in order to increase their knowledge<br />

and experience.<br />

The state of the world’s natural environment and peop-<br />

le’s increasing awareness about their health, means that<br />

interest in organic products will keep growing. Organic<br />

produce is not only relevant to our health, but also<br />

to that of our children. The question at stake is <strong>how</strong><br />

quickly and extensively this will occur. Even today we<br />

can already proudly say that the Organic Corporation<br />

has made a great contribution to the development of<br />

organic market in Russia.<br />

country-reports<br />

10 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 11

Organic and fair-trade:<br />

a growing market<br />

Trade finance:<br />

a crucial link<br />

in the sustainable<br />

value chain<br />

by nelleKe VeenSTra<br />

Recent and expected future growth rates for the organic and fair trade markets<br />

reflect a growing consumer awareness of global trade issues and a wish to<br />

consume sustainably, along ethical and environmental lines. In both Europe<br />

and the United States market demand for many product categories (e.g.<br />

soybeans, sugar and cocoa) is greater than local supply. This leads to ever<br />

increasing demand for imports from Latin America, Asia and also Africa.<br />

However, not all suppliers and farmers in these regions are able to fully grasp<br />

this market opportunity, particular due to a lack of access to (trade) finance.<br />

Long-term sustainable trading partnerships<br />

To tackle these challenges farmers need<br />

the support of committed buyers. For<br />

such buyers the quality of the product is<br />

just as important as the fairness to producers,<br />

business partners or to the environment.<br />

Buyers in the organic and fair trade<br />

market are committed to entering into<br />

long-term and sustainable trading partnerships<br />

with local sourcing companies<br />

that can meet their quality criteria.<br />

The single most important precondition<br />

for building a partnership is timely<br />

payment to farmers, at the time of the<br />

harvest. However, farmers’ cooperatives<br />

generally lack the necessary cash to<br />

bridge the period between harvesting<br />

and being paid by their buyers, and thus<br />

do not have the resources to guarantee<br />

timely payment to farmers. This is where<br />

the need for pre-finance arises. Seen from<br />

this perspective, trade finance is a key<br />

instrument for building sustainable trading<br />

partnerships.<br />

In most developing countries, agricultural<br />

lending is seen as high risk and is therefore<br />

avoided by the banking system. Where<br />

agricultural lending does exist, it is based<br />

on an over-reliance on hard collateral:<br />

land and buildings. Farmer cooperatives<br />

often do not have enough assets to cover<br />

their financing needs, especially during<br />

the cash-intensive harvest season. Value<br />

Chain Finance provides an alternative<br />

approach to traditional agricultural lending.<br />

Instead of relying on hard collateral,<br />

it relies on strong and committed value<br />

chains. Over the past ten years, this type<br />

of lending has been successfully pioneered<br />

by a few national and international<br />

financial institutions. Triodos Bank has<br />

been among the pioneers in this field for<br />

many years. In 2008 the bank launched a<br />

special earmarked fund to support value<br />

chain finance: the Triodos Sustainable<br />

Trade Fund.<br />

Access to finance<br />

The demand for this fund and this type<br />

of finance has been significant from the<br />

start. By the end of 2010, the fund was<br />

financing more than 30 producers’ organizations<br />

and sourcing companies from<br />

Africa, Latin America and Asia. These<br />

companies are involved in the export of<br />

various commodities and perishables,<br />

including coffee, cocoa, sugar, olive oil,<br />

cotton, nuts and herbs.<br />

One of the clients in the Triodos Sustainable<br />

Trade Fund’s portfolio is LATCO Inter-<br />

national from Bolivia. LATCO was founded<br />

in 2003 by Ray and Yoshiko Clavel. The<br />

company sources, processes and exports<br />

sesame seeds from some 1,000 smallholder<br />

farmers in the Santa Cruz area.<br />

Since sesame is not an indigenous crop,<br />

the founders spent a considerable amount<br />

of time and money on providing technical<br />

support to farmers to grow the crop and<br />

to convert to organic production.<br />

Harvest time for sesame runs from March<br />

until June. LATCO has to pay the farmers<br />

upon delivery of the sesame at the collection<br />

points, after which it is transported<br />

to LATCO’s processing plant. Here the<br />

sesame is sorted, cleaned, hulled and<br />

packed. Throughout the rest of the year<br />

LATCO ships the processed sesame to its<br />

customers in Japan, Europe and the USA.<br />

LATCO does not receive payment for its<br />

exported goods until final delivery has<br />

been made.<br />

However, the success of this value chain<br />

depends on the farmers, for whom<br />

sesame is their cash crop, receiving their<br />

About Triodos Bank<br />

Triodos Sustainable Trade Fund is one<br />

of the special purpose funds of Triodos<br />

Bank, which is one of the world’s leading<br />

sustainable banks with a network of offices<br />

in the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK,<br />

Spain and Germany. The bank has been<br />

active in the organic and fair trade sectors<br />

for many years, providing effective<br />

financial solutions for producers, export<br />

organizations, wholesalers and retail<br />

companies. Since its founding, in 1980,<br />

Triodos Bank has mobilized millions of<br />

Euros to support the fair trade and organic<br />

industries from ‘crop to shop’. For<br />

more information see: www.triodos.com<br />

and go to sustainable trade.<br />

money at the moment that they bring in<br />

the harvest. They cannot afford to wait<br />

for months while it is processed, stored<br />

and shipped. If they had to do this they<br />

would sell the sesame to local middlemen<br />

for a lower price in order to obtain much<br />

needed cash.<br />

This is where the value chain finance facility<br />

from Triodos Sustainable Trade Fund<br />

Market & econoMy<br />

comes in. LATCO receives a loan from<br />

the fund with which the farmers can be<br />

paid upon delivery. This bridges the gap<br />

until payments from overseas customers<br />

are received. These payments are then<br />

used to repay the loan from the Triodos<br />

Sustainable Trade Fund. In this way the<br />

loan follows the payment flow of the value<br />

chain, and has become a crucial link in<br />

establishing a sustainable partnership<br />

between LATCO’s customers, who are<br />

reputable long term buyers that provide<br />

the company, and its farmers, with a<br />

long term outlook on income generation.<br />

Another important effect of this sustainable<br />

value chain is that it enables LATCO<br />

to improve overall quality standards,which<br />

further strengthens the relationship with<br />

the overseas customers, and results in a<br />

higher price for the product. Together with<br />

the organic premium this contributes to<br />

an overall higher income for the farmer.<br />

http://www.triodos.com/en/about-triodosbank/what-we-do/our-expertise-overview/<br />

sustainable-trade/<br />

12 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 13

y inGe VoS<br />

Organic school<br />

gardens in Ghana<br />

The Ghana Organic Agriculture Network (GOAN)<br />

is implementing the Organic School Garden Project<br />

(OSGP) in Ghana, together with Agro Eco - Louis<br />

Bolk Institute. The project is funded by Oxfam Novib.<br />

The OSGP has developed organic gardens in 24<br />

schools in Ghana over the past three years. The<br />

gardens produce vegetables and fruits that are used in<br />

the pupils’ meals. The organic gardens are also being<br />

used as demonstration fields for Farmers Field Schools<br />

(FFS), to train local farmers in organic farming practices.<br />

The Organic School Garden Project started in 2008<br />

with 10 schools in 7 different districts. Each school has<br />

a 1-acre organic garden. The gardens produce organic<br />

vegetables and fruits for the pupils’ meals, providing<br />

them with healthy, safe and nutritious food (no pesticides<br />

or residues)<br />

which is also environmentally<br />

friendly.<br />

Crops grown in the<br />

gardens include leafy<br />

vegetables, cabbage,<br />

tomato, pepper,<br />

onion, aubergines,<br />

okra, carrots, water<br />

melon, citrus and<br />

pineapple.<br />

The Government of Ghana established the national<br />

Ghana School Feeding Programme (GSFP) a ten year<br />

programme established in 2006. Its aim is to provide<br />

balanced meals to school pupils at primary schools,<br />

but it has done little to stimulate the local production of<br />

ingredients required to prepare the meals. The OSGP<br />

complements the GFSP by stimulating the production<br />

side. It was set up after extensive consultation with the<br />

Director of Finance and Administration of the GFSP,<br />

who provided input into the design of the project.<br />

Each one acre organic school garden also serves as<br />

a demonstration farm for training adult farmers using<br />

the Farmer Field School (FFS) approach. Each FFS has<br />

trained around forty farmers, with another forty farmers<br />

attending open days and going on exchange visits). In<br />

total, the OSGP has trained 1920 farmers in 24 different<br />

communities within 3 years.<br />

The OSGP financially supports the schools in deve-<br />

loping their organic gardens, especially during the<br />

first year of operation, when garden tools need to be<br />

acquired. When the school garden is well established it<br />

can operate independently, providing organic vegetables<br />

and fruits to the school pupils.<br />

14 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011<br />

15<br />

education

The 17th IFOAM Organic World Congress,<br />

the place to be in September!<br />

The organic<br />

movement<br />

meets in<br />

South Korea<br />

The 17th IFOAM Organic World Congress, the first in Asia, will be held in<br />

the Paldang Region, Gyeonggi Province of the Republic of Korea, from the<br />

28th of September to the 1st of October 2011. The Organic World Congress<br />

(OWC) is the space where the organic movement comes to meet, exchange<br />

experiences and develop ideas and strategies for the development of organic<br />

agriculture worldwide.<br />

deniSe Godinho<br />

The theme of the conference, “Organic<br />

is Life”, reiterates the philosophy<br />

of organic farmers that emphasizes<br />

respect for all living things. The Organic<br />

World Congress (OWC) consists of a main<br />

conference with a systems values track<br />

and a research track, covering a wide<br />

range of topics. The programme is organized<br />

in partnership with the International<br />

Society of Organic Agriculture Research<br />

(ISOFAR). Besides the system values and<br />

research tracks, the congress will also<br />

feature artistic presentations and joint<br />

sessions incorporating presentations from<br />

practitioners and researchers on topics of<br />

common interest as well as well as open<br />

spaces to facilitate creative dialogue,<br />

inspire and initiate concrete action. The<br />

final programme for IFOAM’s Organic<br />

World Congress 2011 will be announced<br />

in June 2011.<br />

Just prior to the main conference, from<br />

the 26th to the 28th of September 2011,<br />

there will be various thematic pre-conferences<br />

in different locations around South<br />

Korea. These conferences will focus on<br />

aquaculture, cosmetics, ginseng, tea, textiles,<br />

urban agriculture and wine.<br />

Special funds have been set aside to facilitate<br />

participation from developing countries<br />

to the Organic World Congress. The<br />

level of sponsorship offered can in clude<br />

conference registration, accommodation<br />

and/or travel, will depend on the candidate’s<br />

in-kind contribution to the conference.<br />

Following the OWC, the 2011 IFOAM<br />

General Assemply (G.A.) will take place<br />

the Namyangju film studios, located in<br />

a beautiful green area in Namyangju<br />

City, from the 3rd to the 5th of October<br />

2011. The General Assembly convenes<br />

once every three years and takes place<br />

in conjunction with the IFOAM Organic<br />

World Congress (OWC). The IFOAM G.A.<br />

is the democratic decision-making forum<br />

of the international organic movement,<br />

where IFOAM’s World Board is elected<br />

for a three-year term. The G.A. provides<br />

strategic guidance to the World Board,<br />

which appoints official committees,<br />

working groups and task forces based<br />

on the motions and recommendations<br />

of IFOAM’s membership. IFOAM G.A.s<br />

are very dynamic and lively gatherings,<br />

inspiring the members, board and staff to<br />

work towards achieving IFOAM’s mission<br />

of leading, uniting and assisting the organic<br />

movement in its full diversity. IFOAM<br />

members are invited to participate in the<br />

G.A. by:<br />

submitting motions about strategic<br />

matters in writing before the G.A.;<br />

proposing and convincing candidates<br />

to run for the World Board;<br />

preparing and submitting a bid for<br />

hosting the 2014 OWC and G.A.;<br />

contributing to the participative<br />

processes at the G.A., i.e. motion<br />

bazaar, strategic consultations;<br />

voting at the G.A. (motions, World<br />

Board, bids).<br />

IFOAM Associates and Supporters are<br />

welcome to participate in the G.A.. Associates<br />

may ask for the floor and speak to the<br />

G.A., although they do not have the right<br />

to vote.<br />

Still at the G.A., a new IFOAM World Board<br />

will be elected; 10 positions are open to be<br />

filled. Election to the World Board means a<br />

challenging opportunity to work to further<br />

develop the worldwide organic movement.<br />

The World Board decides on all issues<br />

not yet determined by, and reports to, the<br />

General Assembly. World Board members<br />

raise funds for IFOAM; they contibute to<br />

the World Board’s decision-making; they<br />

provide strategic input to the development<br />

of IFOAM; they use personal and professional<br />

skills, relationships, and knowledge<br />

for the advancement of IFOAM; and they<br />

represent IFOAM at global events.<br />

All activities for the IFOAM World Board<br />

are voluntary, with no reimbursement for<br />

contribution of time, unless otherwise<br />

specified by World Board decisions. When<br />

necessary, travel and accommodation<br />

costs will be borne by IFOAM. Women,<br />

farmer representatives and people from the<br />

global South are especially encouraged<br />

to consider presenting their candidacies.<br />

Candidates will be presented in IFOAM’s<br />

Newsletter ‘In Action’ 60 days before the<br />

G.A. and to the General Assembly in South<br />

Korea.<br />

For information on OWC sponsorship of<br />

participants from developing countries,<br />

please contact sponsor@kowc2011.org.<br />

For more information on <strong>how</strong> to submit<br />

a motion to the G.A. (IFOAM members),<br />

apply for a World Board position (members<br />

and non-members), or submit a bid to host<br />

and organize the IFOAM Organic World<br />

Congress and General Assembly in 2014<br />

(IFOAM members), please contact Thomas<br />

Cierpka: t.cierpka@<strong>ifoam</strong>.org<br />

For additional information and deadlines<br />

go to: www.<strong>ifoam</strong>.org/kowc2011<br />

16 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 17<br />

ifoaM issues

y MarKuS arbenz<br />

BioFach special theme: Food security<br />

Yes, organic can<br />

feed the world!<br />

<strong>But</strong> <strong>how</strong>?<br />

So far, the world has managed to meet the challenge of food<br />

productivity. Today, there is a 25% global oversupply of food<br />

- measured in terms of the calorific production (after post harvest losses)<br />

needed to feed the world’s population. The challenge is ensuring that<br />

hungry people have access to this food. The strategy of ecologicalintensification,<br />

using organic principles and practices is a new paradigm<br />

for feeding the world while at the same time empowering the poor and<br />

mitigating against climate change and biodiversity loss.<br />

Why is it that we have enough food<br />

to feed the world’s current population<br />

(and an extra 1.5 billion people) but<br />

that world poverty and hunger is increasing<br />

and is predicted to continue to do<br />

so? Despite sufficient global food production,<br />

there are one billion hungry or starving<br />

people in the world, most of them<br />

living in rural areas. It is expected that<br />

the world will produce 70% more food by<br />

2050. The Food and Agriculture Organization<br />

(FAO) of the United Nations estimates<br />

that 80% of this will need to come from<br />

productivity increases and only 20% from<br />

bringing new land into production. Both<br />

strategies will have effects in terms of<br />

loss of biodiversity, degeneration of soils,<br />

water demand and, of course, climate<br />

change.<br />

The main causes of hunger are poverty<br />

and a lack of livelihood opportunities.<br />

Conventional, green revolution-based<br />

or industrial agriculture currently fails to<br />

feed 15% of the world’s population - so<br />

it’s clear that focusing solely on production<br />

does not solve global hunger. Often,<br />

smallholder farmers are pushed off their<br />

Talking about<br />

organic food and<br />

food production at<br />

BioFach...<br />

land by international investments, landgrabbing<br />

and bad governance. While<br />

globalization has opened up opportunities<br />

for many, it has also amplified the challenges<br />

facing humanity. More than ever,<br />

our planet and its poorest inhabitants<br />

are suffering the consequences of poorly<br />

thought through strategies. Poverty and<br />

hunger, climate change, the loss of genetic<br />

diversity, ecocide and land grabbing<br />

are some of the consequences of this - to<br />

which the world has to find effective answers.<br />

The IAASTD report clearly stated<br />

that ‘Business as usual is not option any<br />

more’. Addressing the global food security<br />

challenge is not a question of doing the<br />

same things more effectively, but about<br />

developing an appropriate and equitable<br />

strategy.<br />

“We need a paradigm shift<br />

- a new strategy based on<br />

ecosystem intensification<br />

for increasing the resilience<br />

of farms and using<br />

biodiversity wisely.”<br />

People before commodities:<br />

The IFOAM Food Security<br />

Campaign<br />

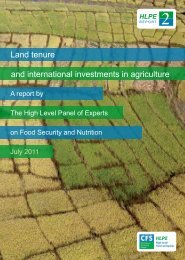

Agriculture is back on the agenda of international decision makers.<br />

Through targeted activities during the World Food Day and related<br />

summits and conferences, IFOAM has been bringing the message<br />

of ‘Sustainability through Organic Agriculture’ to the heart of the<br />

debate. IFOAM’s message is that Organic Agriculture is not merely<br />

a certification standard but a strategic option that can greatly contribute<br />

to improving security. IFOAM continues to carry this message<br />

to decision makers in the public or private sectors, at local, national<br />

or international levels.<br />

Sadly, the recently revived debate on<br />

agriculture and food security has been<br />

largely characterized by a renaissance of<br />

productivity-oriented strategies. Some of<br />

these rely on techno-scientific and largescale<br />

agribusiness options which involve<br />

substantial economies of scale, but which<br />

are neither ecologically and socially<br />

sustainable, nor efficient in land use. The<br />

proposed ‘second green revolution’ does<br />

not provide any convincing answers as to<br />

<strong>how</strong> deprived people will get access to<br />

healthy food and it neglects the key challenges<br />

of equipping the poor with access<br />

to resources, appropriate farming systems<br />

and personal skills. This is a extension of<br />

the type of thinking that created the problem<br />

in the first place and is incapable of<br />

ensuring that all people, at all times, have<br />

physical, social and economic access to<br />

enough safe and nutritious food to meet<br />

their dietary needs and food preferences<br />

enabling them to live active and healthy<br />

lives.<br />

Is ‘Organic’ just a certification standard<br />

for rich people?<br />

It is widely acknowledged that organic<br />

agriculture has brought tremendous<br />

benefits many of those involved in it. It<br />

currently achieves sales of over 50 billion<br />

US$ annually, which benefit millions of<br />

18 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 19<br />

food security

BioFach<br />

2011<br />

Spearheading the<br />

New Green Economy<br />

people along the value chain (not least<br />

small scale producers and consumers).<br />

Yet there is still a widespread misconception<br />

that organic agriculture cannot feed<br />

the world. In 2009, at a high-level expert<br />

forum on <strong>how</strong> to feed the world in 2050,<br />

Jacques Diouf, FAO Director General stated<br />

: While organic agriculture contributes<br />

to hunger and poverty reduction and<br />

should be promoted, it cannot by itself<br />

feed the rapidly growing population. He<br />

Organic operators are potential key players in the New Green Economy<br />

that has been envisaged by UNEP. A fast-growing community<br />

of organic consumers (the annual value of organic retail sales worldwide<br />

is US$ 50 Billion) are looking for agriculture products that<br />

are not just healthy and tasty, but also contribute to environmental<br />

sustainability and the food security of the families and communities<br />

that grow the produce. Organic standards and verification systems<br />

assure fair prices and support the resilience of organic producers<br />

to both climatic and economic shocks. Through ethical investment<br />

and consumption choices the entire value chain is contributing to<br />

enhanced food security and promoting products that have a smaller<br />

ecological footprint and improve the livelihoods of the producers.<br />

expressed the thoughts of many experts:<br />

that organic production is good for creating<br />

added value for those who can tap<br />

into the right market niches. <strong>But</strong> its broader<br />

applicability has not been appreciated<br />

and as a consequence, organic agriculture<br />

has rarely managed to be part of a broadbased<br />

vision for international organizations,<br />

governments or donor agencies. This<br />

is despite the impressive impacts that<br />

organic agriculture has had in recent years<br />

on the livelihoods of rural people, often<br />

in highly marginalized and fragile environments.<br />

The organic movement needs to<br />

make policy makers more aware of the<br />

potential of organic farming as a viable<br />

and proven strategy for developing and<br />

improving livelihoods.<br />

The need for a paradigm shift - a new<br />

strategy based on affordable production<br />

systems for the poor - is obvious. The<br />

answer to the question, <strong>how</strong> can organic<br />

agriculture meet the growing global<br />

demand for food can be summarized in<br />

one word: eco-intensification.<br />

Eco-intensification has several aspects. It<br />

involves intensifying the natural process<br />

of nutrient cycling, stimulating soil biology<br />

through composting, crop rotation, mixed<br />

cropping or agro-forestry. These practices<br />

enhance the health, vitality and productivity<br />

of farm ecosystems. Higher levels of<br />

organic matter in the soil enhance water<br />

retention and build robust soils that are<br />

resilient to erosion. Avoidance of toxic<br />

pesticides and the utilization of diverse<br />

species enhance (rather than inhibit)<br />

nature’s constant drive for balance, thereby<br />

enabling the ecosystem to regulate<br />

pests and diseases naturally. The farming<br />

system is managed through applying<br />

ecological knowledge and practices that<br />

stimulate and beneficially intensify the<br />

systems’ ecological functions.<br />

Eco-intensification often draws on the<br />

knowledge and practices of the world’s<br />

traditional farming systems that have nourished<br />

communities for hundreds, or even<br />

thousands, of years. The key to success<br />

“The reality is that conventional,<br />

green revolution-based<br />

or industrial agriculture fails<br />

to feed 15% of the world’s<br />

population - so it’s clear that<br />

focusing solely on production<br />

does not solve global hunger.”<br />

is to consciously work with, rather than<br />

against, nature and to support ecosystem<br />

services. In places where intensive<br />

agriculture is practised most farmers who<br />

convert to organic production achieve<br />

yields that are close to those of conventional<br />

farms, within a few years of conversion.<br />

In marginal areas with depleted<br />

soils or limited water resources the yields<br />

from organic production are often much<br />

greater. Thus organic production helps<br />

improve productivity in the areas where it<br />

is most needed.<br />

There is huge potential to significantly<br />

increase agricultural productivity and<br />

biodiversity by harnessing, developing<br />

and intensifying biological soil activities.<br />

Eco-intensification generally also involves<br />

more labour and better knowledge, thus<br />

contributing to more opportunities for<br />

landless poor people and improving the<br />

‘quality of work’.<br />

If the world is to nourish its people on<br />

the principles of eco-intensification, we<br />

need to learn much more about natural<br />

processes in order optimize diversified,<br />

locally adapted food production systems.<br />

This could not be achieved overnight but<br />

would involve a slow transition of learning<br />

and undoing the negative impacts<br />

of unsustainable<br />

farming of past<br />

decades. However,<br />

if humanity<br />

invests resources<br />

and effort in learning<br />

to better use<br />

the potential provided<br />

by nature,<br />

the existing land<br />

and water and<br />

human resources<br />

will be able to<br />

provide more than<br />

enough food to<br />

meet the requirements of an expanding<br />

human population. We are confident that<br />

organic agriculture can provide abundant<br />

food to feed a growing world population.<br />

The main bottleneck to such a vision<br />

becoming a reality is not the limitations<br />

of natural resources but a lack of political<br />

willingness and imagination.<br />

Eco-intensfication as a reality.<br />

Ethiopia and Egypt are two countries that<br />

are already adopting strategic elements<br />

advocated by the organic movement. In<br />

both countries, land has been regenerated<br />

with organic agriculture and peoplecentred<br />

approaches. This has resulted in<br />

thousands of people finding confidence<br />

in their farming abilities and being better<br />

able to feed their families. The Ethiopian<br />

government has recently put organic<br />

practices at the heart of its national agriculture<br />

development policies and Egypt<br />

has been dramatically reduced pesticide<br />

use after consultation with local organic<br />

farmers.<br />

Supporting small-scale farmers across the<br />

world strengthens the livelihoods of the<br />

poor and increases their access to food.<br />

To make this a reality, the right policies<br />

are needed at international, national and<br />

local levels, policies that require corporate<br />

social responsibility and support the<br />

capacity of the poor, through relevant<br />

research and advisory services in ecological<br />

intensification.<br />

20 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 21<br />

food security

Your Partner<br />

In Organic Potatoes,<br />

Vegetables and Fruits<br />

Im- & export of fresh and industrial organic potatoes,<br />

vegetables and fruits. Custom designed and reliable services<br />

for sourcing and marketing your organic products.<br />

The Netherlands<br />

Hall 7/7-625<br />

Project scale has a large<br />

influence on the cost price<br />

The economics<br />

of coffee<br />

by PeTer brul<br />

In 2010 more than 7 million tonnes of coffee were produced,<br />

by millions of farmers. Small scale farmers (with less than 10<br />

hectares) cultivate approximately 9 million hectares of coffee,<br />

while large scale farmers cultivate approximately 3 million hectares.<br />

Despite this 75% of the world’s coffee is produced by<br />

large scale farmers on plantations.<br />

Organic coffee accounts for around 0.5 % of the world market,<br />

and a large part of this produced by smallholders, rather than<br />

large scale farmers. The world’s supply of organic coffee in<br />

2010 was estimated at more than 200,00 tons of green coffee<br />

(up from 100,000 in 2007). More than 50% of this comes from<br />

Latin America. There are more than 300,000 organic coffee<br />

producers in more than 20 countries. Global demand has been<br />

estimated at 70,000 tons of green coffee in 2007 and more than<br />

150,000 in 2010, the lion’s share being in the USA and Europe.<br />

Organic (and fair trade) coffee production started in Chiapas,<br />

Mexico in the early 1980s. Most of the producers in Mexico<br />

and the other 25 organic coffee producing countries are smallholders,<br />

often working in cooperative structures. The niche<br />

markets of organic, fair trade and other sustainable labels, such<br />

as ‘Rainforest Alliance’ provide a way for them to survive. The<br />

cooperatives get a premium price, but there are also additional<br />

Costs per ton in small and large scale organic coffee projects (in US$)<br />

Annual coffee production: 50 tons/year 200 tons/year<br />

Certification 160 40<br />

Management 240 60<br />

Total 520 130<br />

costs related to the system. One can distinguish between fixed<br />

costs, that do not depend on the yield per hectare or per farm<br />

and variable costs, that are more related to the yield.<br />

The fixed costs of an organic coffee project involve those for<br />

field officers, certification, extra management, and extra processing<br />

costs, the variable costs relate to buying and storage. In<br />

smaller projects a large part of the organic premium need to go<br />

to cover the extra costs of certification scheme only a smaller<br />

amount goes to provide extra income to the farmers.<br />

Producer Countries<br />

The America’s Asia and Oceania Africa<br />

• Brazil • East Timor • Ethiopia:<br />

• Colombia<br />

washed and natural arabica<br />

• Peru<br />

• India<br />

• Kenya:<br />

• Costa Rica • Indonesia<br />

washed arabica<br />

• Mexico<br />

• Madagascar:<br />

• USA<br />

• Papua New Guinea robusta<br />

• Sri Lanka<br />

• Tanzania:<br />

robusta,<br />

• Thailand<br />

natural and washed arabica<br />

• Vietnam<br />

• Uganda:<br />

• China<br />

robusta,<br />

• Australia<br />

natural and washed arabica<br />

A 20% premium for organic coffee is considered normal, but<br />

this can increase or decrease in relation to supply and demand.<br />

The premium often increases as a percentage when coffee prices<br />

are low (30 to 40%) and decreases with high prices. The<br />

current organic premium for Arabica is about US$ 330 per ton<br />

and for Robusta it is about US$ 250 per ton.<br />

ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011<br />

Market & econoMy<br />

23

In early October Mike Nicholls visited the Netherlands to<br />

attend the first ISHS Symposium on Organic Greenhouse<br />

Horticulture at the University of Wageningen Greenhouse<br />

Research Centre at Bleiswijk. At this symposium it became<br />

clear that there is a huge difference in the definition of organic,<br />

which varies greatly from country to country. In fact the only<br />

common factor appeared to be that the inputs used in climate<br />

controllable greenhouses or tunnels must be derived solely<br />

from natural, non-chemical, sources.<br />

The first ISHS Symposium on Organic<br />

Greenhouse Horticulture<br />

Organic<br />

greenhouse<br />

horticulture<br />

symposium<br />

by MiKe niCholS<br />

Retail pack<br />

of ‘Wild<br />

Wonder’<br />

tomatoes.<br />

Harvesting<br />

at BiJo.<br />

Nico Vergote at Kruishouten with organic<br />

greenhouse tomatoes.<br />

For example, in Scandinavia, it is<br />

accepted that, provided the roots<br />

are still attached, plants can be grown in<br />

an organically derived nutrient solution<br />

and sold as organic. In the USA there are<br />

now two aquaponic operations certified<br />

as organic by the USDA. In the rest of<br />

Europe it is a requirement that all organic<br />

crops are grown in the soil. The situation<br />

becomes even more complex when one<br />

examines the way in which these crops<br />

are grown. In the Netherlands many<br />

greenhouse organic crops are produced<br />

in a very similar manner to conventional<br />

greenhouse crops in terms of heating and<br />

carbon dioxide inputs, whereas in Austria<br />

and Italy supplementary heating can only<br />

used to avoid crop damage from frost.<br />

Finally in some situations it is permissible<br />

to sterilise the soil with steam in order<br />

to control weeds, nematodes or fungi.<br />

This appears to be in direct opposition<br />

to the concept of developing a healthy<br />

soil, as steam leaves a virtual biological<br />

vacuum which can be invaded by any<br />

organism. This is not to suggest that the<br />

general standard of organically grown<br />

crops is poor—nothing is further from<br />

the case, but to emphasise the lack of<br />

a clear-cut policy on <strong>how</strong> organic crops<br />

can or can not be grown. It also raises<br />

the question of who should have the<br />

authority to make the decisions on what<br />

constitutes an organically grown crop. To<br />

date this has been the organic movement,<br />

often (later) backed up by minimum legal<br />

standards but it is debatable whether<br />

they (with their vested interests) are the<br />

appropriate group to determine the future<br />

direction of greenhouse organics. The<br />

Dutch experiences s<strong>how</strong> the difficulties<br />

of using a soil based system is very clear,<br />

but the current regulations there prevent<br />

exploring the obvious possible advantages<br />

of using a recirculating hydroponic<br />

system. The regulatory framework for<br />

The conference delegates visited the<br />

University of Wageningen Research<br />

greenhouses at Bleiswijk.<br />

organic greenhouses within Europe does<br />

not clarify matters, apart from a ban on<br />

hydroponics, the EC regulation contains<br />

no specific rules for greenhouses. There<br />

are also considerable differences between<br />

EU countries on the use of energy and<br />

also on the use of substrates. The lack of<br />

a level playing field is felt by many producers<br />

to lead to unfair competition.<br />

Highlights of current research<br />

The meeting commenced with an overview<br />

from Rob Meijer of the issues<br />

facing and current research into, organic<br />

greenhouse horticulture world-wide. This<br />

proved to be a near impossible task,<br />

but it provided a start in filling in some<br />

previously blank boxes. It s<strong>how</strong>ed that<br />

in Switzerland and Austria up to 14% of<br />

greenhouse production area was organic,<br />

but in most countries with significant<br />

greenhouse industries (e.g. the Nether-<br />

lands) only 2-3% was organic.<br />

Fabio Tittarelli (Italy) provided an insight<br />

into the outlook for vegetable nursery<br />

innovation in agriculture<br />

production for organic production. This<br />

sector faces the major constraint that<br />

peat—a major constituent of substrates<br />

is a non-renewable resource, and that<br />

peat bog exploitation is not sustainable<br />

in the long term. Valérie Gravel (Canada)<br />

explored the complex nutrient management<br />

of organic systems, presenting a<br />

case study of six organic soils that use a<br />

re-circulating system, with certified organic<br />

nutrients. Wim Voogt (Netherlands)<br />

demonstrated the difficulties of providing<br />

greenhouse crops with sufficient nutrients<br />

within a soil based non-recirculating<br />

system while also complying with the<br />

European Directives relating to annual<br />

N and P application levels. I presented<br />

my paper on organic hydroponics, which<br />

essentially flies directly in the face of conventional<br />

organic growing.<br />

Soil health is a key factor in ensuring crop<br />

productivity, and greenhouse production<br />

has its own distinct problems. Unlike field<br />

production, the opportunities for crop rotation<br />

are minimal, so alternative methods<br />

of controlling pathogens are needed. Soil<br />

suppressiveness is one possible means of<br />

reducing the activity of pathogens. André<br />

van der Wurff (Netherlands) demonstrated<br />

that suppressiveness was pathogendependant,<br />

at least for the fungi Verticillium<br />

and Pythium and for the nematode<br />

‘There are large differences between<br />

EU countries over what is permitted in<br />

organic glasshouses’<br />

Meloidogyne. Another possible solution<br />

for greenhouse crops is to use the “Köver”<br />

system. This was described by Willemijn<br />

24 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING ECOLOGY & FARMING | 1-2011 25

Fresh lettuce ready to be cut at BiJo. A “Wild Wonder” tomato variety.<br />

Cuijpers from the Louis Bolk Institute (Netherlands).<br />

The “Köver” system involves<br />

dividing each bed in the greenhouse into<br />

half with a physical barrier, and leaving<br />

half the bed fallow (or planted with an<br />

antagonistic crop), and then annually<br />

alternating the part of the bed planted with<br />

the main crop. In general the system was<br />

found to be impracticable, because yields<br />

of the crop plants fell, due to competition<br />

with the antagonistic plants. There is also<br />

considerable interest in the biological<br />

disinfection of the soil with grass and<br />

other fresh organic materials that can suppress<br />

persistent diseases and pests. This<br />

approach involves covering the soil with<br />

fresh organic matter and then with airtight<br />

plastic. The resulting anaerobic conditions<br />

offer an alternative to steam sterilisation,<br />

but the time lag between treatment and<br />

the next time the bed can be used is a<br />

major barrier. Steaming remains the most<br />

effective, and preferred treatment, but is<br />

expensive both in labour and in energy.<br />

The next session involved comparing<br />

different growing systems for organic<br />

glasshouse production. Wolfgang Palme<br />

(Austria) examined an initiative (near<br />

Vienna) for producing a range of Brassicas<br />

(Pak Choi, Mustard, and Tatsoi) in<br />

plastic houses without any heating. This<br />

approach seemed to offer some potential<br />

for the production of low energy organic<br />

crops. However when growth was poor<br />

26 1-2011 | ECOLOGY & FARMING<br />

(in mid-winter) high nitrate levels in the<br />

soil became a problem. Valérie Gravel<br />

(Canada) presented a paper on organic<br />

greenhouse tomato production using raised<br />

bed containers filled with either peat<br />

or coir (coco peat). This presentation was<br />

followed by one from her colleague, Martine<br />

Dorais, who demonstrated increased<br />

yields by using oxygen enriched irrigation<br />

water to increase the soil oxygen content.<br />

A key factor for the future successful production<br />

of organic greenhouse tomatoes<br />

will be the grafting of the scion (variety)<br />

onto the appropriate rootstock. To date<br />

the development of tomato rootstocks<br />

has been a fairly ad hoc procedure, but<br />

Jan Venema (University of Groningen,<br />

Netherlands) described a Dutch programme<br />

aimed at delivering a reliable screening<br />

method to identify biomarkers that<br />

can be used as generic tools to identify<br />

the best rootstocks. It must be remembered<br />

that the grafting of vegetables onto<br />

rootstocks is a fairly recent development,<br />

and there could well be interesting interactions<br />

between specific rootstocks and<br />

scions, similar to those that exist in fruit<br />

trees. Grafting is being developed to<br />

overcome a range of problems, including<br />

improving nutrient use efficiency, suboptimal<br />

temperatures and salinity, but one<br />

of the major problems with organic greenhouse<br />

production of fruiting vegetables<br />

is nematodes—particularly the Root Knot<br />

Nematode (RKN) or Meloidogne spp.<br />

Above-ground pathogens can also be a<br />

problem in organic systems, and Michael<br />

Raviv (Israel) demonstrated <strong>how</strong> the risk<br />

of bacterial canker on tomatoes (a major<br />