Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

Schwetzingen - Schlösser-Magazin

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

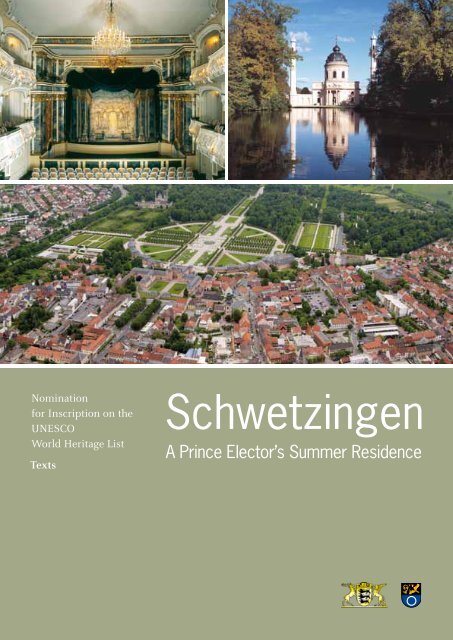

Nomination<br />

for Inscription on the<br />

UNESCO<br />

World Heritage List<br />

Texts<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

A Prince Elector’s Summer Residence

Editor: Wirtschaftsministerium Baden-Württemberg;<br />

Finanzministerium Baden-Württemberg;<br />

Stadt <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

All rights reserved (© 2009).<br />

Project Management<br />

and Contact: Staatliche <strong>Schlösser</strong> und Gärten Baden-Württemberg,<br />

Schlossraum 22, 76646 Bruchsal<br />

andreas.falz@ssg.bwl.de<br />

Informations: www.welterbeantrag-schwetzingen.de<br />

Redaction: Andreas Förderer, Petra Schaffrodt, Petra Pechacek<br />

Translation: Susanne Stopfel, Katherine Vanovitch, Michael Senior<br />

(List of Monuments)<br />

End-papers: Zeyher/Roemer 1809<br />

Jacket image: Bernd Hausner, Regierungspräsidium<br />

Stuttgart, Landesamt für Denkmalpflege<br />

Michael Amm, Stuttgarter Luftbild Elsässer<br />

Verso: Gesamtplan, Verdyck & Gugenhan, Landschaftsarchitekten<br />

Layout: Struve & Partner, Atelier für Grafik-Design,<br />

Sickingenstraße 1a, 69126 Heidelberg<br />

hs@struveundpartner.de

Nomination<br />

for Inscription on the<br />

UNESCO<br />

World Heritage List<br />

Texts<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

A Prince Elector’s Summer Residence

Contents<br />

I. Introduction 7<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

a) Elector Carl Theodor and his Palatinate – a World in Transition (Stefan Mörz) 9<br />

b) <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Summer Capital of the Electoral Palatinate<br />

(Ralf Richard Wagner) 14<br />

c) Musical Life at the Court of Elector Carl Theodor from 1743 to 1778<br />

(Bärbel Pelker) 21<br />

III. Architectural Features<br />

a) The Palace Theatre – the Ideal of an Eighteenth-Century Theatre<br />

and Opera House (Monika Scholl, Peter Thoma) 27<br />

b) The Bathhouse – Synthesis of the Arts and Refuge of Elector Carl Theodor<br />

(Ralf Richard Wagner) 32<br />

c) The Mosque – an Embodiment of Eighteenth-Century Taste and Thought<br />

(Susan Richter) 42<br />

d) The Arabic Insriptions of the Mosque – a Manifestation of Inter-<br />

Cultural Dialogue (Udo Simon) 51<br />

e) “… Beyond this lake, finally, there still stands a dilapidated Temple to Mercury,<br />

possibly the most excellent feature of this garden.”<br />

(Monika Scholl, Peter Thoma) 59<br />

IV. Palace Gardens: Role and Significance<br />

a) The Iconography of the <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> Palace Gardens<br />

(Michael Hesse, Hartmut Troll, Ralf Richard Wagner) 67<br />

b) The Collection and Cultivation of Exotic Plants<br />

(Jochen Martz, Hubert Wolfgang Wertz, Rainer Stripf) 79<br />

c) The Cultural Landscape of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> (Svenja Schrickel, Hartmut Troll) 90<br />

d) The 19th and 20th Centuries: Preserving the Palace Gardens as a<br />

Historic Monument (Hubert Wolfgang Wertz) 98

V. Science and Technology<br />

Contents<br />

a) On the Excavations in the <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> Palace Gardens.<br />

Elector Carl Theodor as a Trailblazer for Archaeological Research<br />

and Conservation (Andreas Hensen) 109<br />

b) The Urban Prospect of the Old Palace as a Retrospective Monument<br />

to Dynastic Authority (Achim Wendt) 114<br />

c) The Waterworks and Carl Theodor’s Scientific Experiments –<br />

Technical Monuments of the Highest Order (Kai Budde) 127<br />

VI. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Historical Context<br />

a) The Prince Electors and their <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> Estate 135<br />

1. A Summarized Political History (Stefan Mörz)<br />

2. History of the Town of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> (Joachim Kresin)<br />

3. The Genesis of the Palace Square (Joachim Kresin)<br />

b) History of the Palace 151<br />

1. The Origins of the Castle und the Palace (Peter Knoch, Robert Erb)<br />

2. The Palace Interior through the Ages (Wolfgang Wiese)<br />

3. The Palace’s Fortunes in the 19th and 20th Centuries<br />

(Claudia Baer-Schneider, Peter Thoma)<br />

c) History of the Palace Garden 180<br />

1. The Origins of the Palace Garden (Uta Schmitt)<br />

d) The Summer Residence – Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Responses 198<br />

1. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> and its Status as Reflected in Travel Accounts, Images<br />

and Literature (Susan Richter)<br />

2. The Schwetzinger Festspiele: the Legacy of the Summer Residence<br />

(Peter Stieber)<br />

VII. Appendices<br />

a) Biographies (Manuel Bechtold, Susan Richter, Ralf Richard Wagner,<br />

Hubert Wolfgang Werz, Joachim Kresin) 211<br />

1. Rulers (in chronological order)<br />

2. Artists (in alphabetical order)<br />

b) Chronology (Tanja Fischer) 231<br />

c) List of Monuments in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> (Annegret Kalvelage, Melanie Mertens) 234<br />

d) Bibliography (Stefan Moebus, Wolfgang Schröck-Schmidt) 253<br />

e) Overall Map 270

SCHWETZINGEN,<br />

BLICK VON SÜDEN<br />

Voltaire (François-Marie<br />

Arouet), 1768.<br />

„ “<br />

gest. von Barthélemy de La Rocque<br />

Before I die there is one duty I would discharge, and one comfort I crave: I yould see<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> again. That is the thought that fills my soul.

I. Introduction<br />

In the eighteenth century a magnificent<br />

country seat was created at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

under the Electors Palatine – a unique<br />

complex consisting of a town, palace and<br />

garden that has stood largely unchanged<br />

to the present day. In the Palatine summer<br />

residence of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, courtly life was<br />

geared towards pleasure and diversion – in<br />

contrast to the main residence of Mannheim,<br />

where the focus was on administration<br />

and display. It is this annual move of the<br />

entire court from Mannheim to the summer<br />

residence, for a stay of several months’<br />

duration, that explains the unique conditions<br />

at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>: a town wholly aligned with<br />

the palace but formally subordinate to it – a<br />

palace that seems huge compared to the town<br />

but at the same time quite unpretentious – a<br />

vast garden with a variety of buildings that<br />

maintains its status as an autonomous<br />

element.<br />

The more important a cultural monument,<br />

the more it is possible to discover about it.<br />

History, building history, art history, garden<br />

history, social history, the history of music, of<br />

the sciences, of ideas – invariably the visible,<br />

tangible remains refer to the past. And what<br />

was artificially divided up into disciplines and<br />

categories of research, because of the sheer<br />

complexity of history, retains its original unity<br />

in the cultural monument itself.<br />

This volume undertakes to illuminate the<br />

main aspects of the proposed nomination for<br />

inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage<br />

List from a number of different points of<br />

view:<br />

Part II considers the role of the summer<br />

residence, in particular the tribute it paid<br />

under Elector Carl Theodor to the performing<br />

arts, and especially to music. Part III and<br />

Part IV focus primarily on the structural<br />

and spatial design of the residence. They<br />

place the most significant buildings<br />

within their cultural history and provide<br />

a detailed description of aspects crucial to<br />

understanding the palace garden: its function,<br />

its design, its relationship to its surroundings<br />

and the continuity underlying its care.<br />

Part V takes a closer look both at references<br />

to the historical importance already being<br />

attached to the complex when it was the<br />

“summer capital of the Palatinate” and at the<br />

scientific principles reflected in the extensions<br />

carried out under Carl Theodor. The historical<br />

background essential to appreciating the<br />

garden, the palace and the village in context<br />

will be found in Part VI, along with an outline<br />

of the political situation in which the summer<br />

residence evolved and subsequent perceptions<br />

of the residence. This is followed in Part VII<br />

by guidance for the reader’s rapid orientation.<br />

The concluding Part provides a quick<br />

overview of the basic facts: short biographies<br />

of the rulers and the artists active at<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, a chronology of major events, a<br />

summarized description of the properties and<br />

objects inscribed on the list of monuments<br />

and a bibliography of publications on the<br />

town, palace and garden. The overall map<br />

with detailed captions included at the back<br />

is intended to give an idea of the property<br />

as a whole, and provide information to<br />

complement the essays.<br />

I.<br />

7

DER APOLLOTEMPEL<br />

Ivan Turgeniev in<br />

,Visionen‘,1864.<br />

gest. von Haldenwang<br />

„ “<br />

What is that park down there with avenues of smoothly pruned limes, with solitary firs cut into<br />

shapes like umbrellas and fans, with columned halls and temples in the taste of Pompadour,<br />

with statues of nymphs in Berni’s style, of Rococo tritons in the midst of shallow pools, held in by<br />

balustrades of crumbling marble? Can this be Versailles? No, it is not Versailles! A small palace,<br />

built in the Rococo style as well, peeks out from behind a group of oaks. The moon is half-veiled,<br />

only faint light descending – it is as if a thin haze is spread on the ground. Is it mist, is it moonlight?<br />

The eye cannot tell. A swan is slumbering on one of the ponds, his long white back gleaming<br />

like the snow of our steppes once it is frozen, and there in the blue shadows, glow-worms shimmer<br />

like diamonds on the bases of statues. “We are near Mannheim”, said Ellis, “this is the park of<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>.” We are in Germany, then”, I thought, and listened. All was quiet, only a solitary jet<br />

of water fell somewhere, unseen, softly splashing.

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> –<br />

Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

a)<br />

Elector Carl Theodor and his<br />

Palatinate – a World in Transition<br />

During the second half of the eighteenth<br />

century, the Elector Palatine’s court was one<br />

of the most interesting and glittering of<br />

Germany. Mannheim was one of the European<br />

centres of music, and visitors from all over the<br />

continent flocked to the “Palatine Athens”.<br />

The transformation of a country and city<br />

ravaged by more than a century of almost<br />

incessant wars into one of the places of<br />

Europe an educated person simply had to<br />

see, was the achievement of two electors, Carl<br />

Philipp and his successor Carl Theodor.<br />

A Glittering Court 1<br />

A thoroughly Baroque despot for whom<br />

”splendour was always more important<br />

than reform” 2 , Carl Philipp (1661-1742),<br />

who ruled from 1716 to 1742, had inherited<br />

the electorate from his brother at a rather<br />

advanced age. The new elector first moved the<br />

court back to the old residence in Heidelberg.<br />

In 1720 he chose Mannheim as his new<br />

capital. Here, in the wide plain by the Rhine,<br />

Carl Philipp, praised as “Palatine Aeneas”,<br />

could found a truly baroque residence, a<br />

palace that was to be one of the biggest<br />

in Germany, surrounded by the spiritual<br />

and temporal pillars of electoral might:<br />

monasteries, barracks and no fewer than 54<br />

aristocratic houses. Joined to the palace was<br />

the Jesuits’ college with its big church, a copy<br />

of Il Gesu in Rome, a visible symbol of the<br />

close symbiosis between the electoral house<br />

and the Catholic church. Protestant churches,<br />

by contrast, were relegated to the parts of<br />

town most distant from the Elector‘s home.<br />

As neither Carl Philipp nor any of his<br />

1 For the follwing pages: Stefan Mörz, Haupt- und Residenzstadt.<br />

Karl Theodor, sein Hof und Mannheim (= Kleine Schriften<br />

des Stadtarchivs Mannheim, Nr. 12), Mannheim 1998; Stefan<br />

Mörz, Aufgeklärter Absolutismus in der Kurpfalz während<br />

der Mannheimer Regierungszeit des Kurfürsten Karl Theodor<br />

1742-77 (= Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für geschichtliche<br />

Landeskunde in Baden-Württemberg, Reihe B, vol. 120),<br />

Stuttgart 1991.<br />

2 Hans Schmidt, Kurfürst Karl Philipp, Mannheim 1964, p. 88.<br />

numerous brothers had any male offspring,<br />

the Electorate fell into the hands of another<br />

collateral branch of the Palatine Wittelsbachs,<br />

the line of the dukes of Pfalz-Sulzbach (a poor<br />

and small territory in the Upper Palatinate).<br />

The elector’s heir was Carl Theodor (1724-<br />

1799), a young prince, orphaned at the age of<br />

four, who had been educated by his greatgrandmother<br />

in Brussels, a devout old lady<br />

who imbibed him with the creeds of the house<br />

of Sulzbach and of her age – Catholicism and<br />

absolutism in the French/Spanish style. His<br />

native tongue was French, and he did not<br />

learn German until he was about six. When<br />

he was brought to Mannheim in 1734, his<br />

education was taken over by the 70-year-old<br />

Elector, a thoroughly un-intellectual soldier,<br />

who was assisted by a rather wily Jesuit<br />

and an equally old courtier, the Marquis<br />

d‘Ittre (1683-1766). In 1742, Carl Theodor,<br />

shy and of fragile health, was married to the<br />

Elector‘s grand-daughter, Elisabeth Augusta<br />

(1721-1794), a lively and very strong-minded<br />

young woman three years his senior who<br />

was interested in music, theatre, hunting,<br />

amusements and not much else. The wedding<br />

of Carl Theodor and Elisabeth Augusta<br />

turned out to be the grandest court spectacle<br />

that Mannheim ever was to witness. Most<br />

members of the Wittelsbach family were<br />

I.<br />

Fig. 1: The territories of the<br />

Palatine Wittelsbachs in the<br />

18th century (From: Pfalzatlas<br />

bzw. Mörz 1991).<br />

9

II.<br />

10<br />

Fig. 2: Elector Carl Theodor<br />

(1724-1799), painting by<br />

Johann Georg Ziesenis, 1758<br />

(Heidelberg, Kurpfälzisches<br />

Museum).<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

present, the Elector-Archbishop Clemens<br />

August of Cologne (1700-1761) married the<br />

couple, the newly erected opera-house was<br />

used for the first time.<br />

When Carl Philip died the night before<br />

New Year’s Day of 1743, the 18-year-old Carl<br />

Theodor became Elector – and at first was<br />

governed by his old instructor d’Ittre. The<br />

War of the Austrian Succession ravaged<br />

many of the young elector’s territories, and<br />

in 1743, even the court’s summer sojourn in<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> had to be broken off because of<br />

approaching foreign troups. As tax revenues<br />

fell drastically due to the war, d’Ittre, a stern<br />

old gentleman, insisted on the strictest<br />

economy.<br />

However, when the war actions moved to<br />

more distant places, d’Ittre’s “miserly” ways<br />

became more and more unpopular with<br />

the courtiers and, first and foremost, the<br />

electress, convinced her husband to spend<br />

more to restore the splendour of the Palatine<br />

court. Carl Theodor shared the view then<br />

commonly held by many rulers (and their<br />

subjects) that an impressive court was most<br />

important to demonstrate their status and<br />

gain much-coveted “fame”. Thus he followed<br />

his wife’s wishes: D’Ittre was forced to hand<br />

in his resignation, and only weeks later the<br />

Elector gave orders for the completion of<br />

the huge Mannheim Palace. It was doubled<br />

in size and offered sufficient space for the<br />

display of the various collections as well as for<br />

the big library, new kitchens and the mews.<br />

By good fortune, the music-loving electress<br />

also encouraged her husband who, in this<br />

respect, was a kindred soul, to enlarge the<br />

court orchestra which was to become one of<br />

the wonders of the eighteenth-century world<br />

admired by many travellers – and by Mozart.<br />

From 1748, the court opera began to be used<br />

again permanently, and during the following<br />

decades a great number of “opere serie” were<br />

staged there, later to be complemented by<br />

“lighter” operatic pieces performed on the<br />

stage of the <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> theatre built in the<br />

1750s.<br />

While Carl Theodor and his wife looked to<br />

France as regards design and architecture<br />

and to Italy as regards music, the Palatine<br />

court was organized on the model of the<br />

imperial court in Vienna. After all, the elector<br />

was one of the most eminent Princes of the<br />

Empire. Thus, in the 1770s, about 750 servants<br />

and 250 guards were grouped in eight<br />

“departments”, dealing with the maintenance<br />

of the buildings and gardens, the court chapel<br />

and collections, the personal services to the<br />

elector, the court supply and kitchens, the<br />

stables and the pages, the court music, the<br />

court hunts and the personal services to the<br />

electress. An incredibly intricate “clock-work”<br />

of interdependent services helped to keep this<br />

huge organism going. Hardly anything could<br />

be left to spontaneous impulses, and even the<br />

elector was subject to rigid rules.<br />

And yet, ordinary people naturally envied<br />

this mass of well-clad and well-fed courtiers<br />

who enjoyed so many privileges. They hardly<br />

noticed that many of the lower retainers<br />

earned so little that they could never afford to<br />

marry, that they had to spend much of their

lives in small and crammed rooms which they<br />

shared with several others. What people saw<br />

were the string of entertainments that all the<br />

year round (reduced, but not stopped, during<br />

Lent) served to please and divert courtiers,<br />

visitors and, in many cases, the inhabitants of<br />

Mannheim and the neighbouring countryside,<br />

who could see the fireworks, listen to the<br />

music and follow the electoral barges on<br />

the Rhine from a distance – and, as many<br />

observers stated, were extremely keen on<br />

these pleasures. The entertainments also<br />

emphasized the “august” position of the<br />

Elector Palatine. Thus the celebrations for<br />

birth- and namedays of both the Elector and<br />

the Electress in November, December and<br />

January lasted for more than six days each<br />

time in the 1750s, including opera, theatre,<br />

gala-dinners and receptions, fireworks, balls,<br />

and often incredibly expensive hunts both<br />

”seated” and ”par force”. Every May, after<br />

holding reviews of the Palatine troops in the<br />

Rhine plain near Mannheim, that were of<br />

more ornamental than practical value, the<br />

Elector and his court moved to <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

which served as the summer-residence until<br />

September. After the de-facto-breakdown<br />

of his marriage in the 1760s, Carl Theodor<br />

gave the palace of Oggersheim which<br />

had been the property of a relative of the<br />

electoral couple, to the Electress. From then<br />

on, Elisabeth Augusta chose to spend her<br />

summers there. Thus the Palatine court had in<br />

fact two summer-residences which both saw<br />

accomplished entertainments staged by the<br />

Mannheim orchestra and opera, the French<br />

theatre company and the ballet.<br />

“The Spirit of our Century” Transforms the<br />

Court3 From the early 1760s, the Elector wanted<br />

his court and reign not only to shine with<br />

the gold of architectural ornaments and the<br />

3 Wolfgang von Hippel: “Die Kurpfalz zur Zeit Carl Theodors<br />

(1742-1799) – wirtschaftliche Lage und wirtschaftspolitische<br />

Bemühungen”, in: Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins,<br />

N.F. 109/2000, pp. 177-244. Mörz 1991, as above; Mörz 1998,<br />

as above; Stefan Mörz, “Das Ende der alten Zeit: Der Raum<br />

Ludwigshafen im 18. Jahrhundert”, in: Geschichte der Stadt<br />

Ludwigshafen, vol. 1, Ludwigshafen 2003, pp. 133-197.<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

glitter of perfect entertainments; he aspired<br />

to be admired as a ruler who knew about and<br />

appreciated the “spirit of the age” – of the Age<br />

of Enlightenment. Well-read and intelligent,<br />

he proved quite accessible to modern ideas.<br />

Twice he received Voltaire, the ”wise man of<br />

Ferney”, at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>.<br />

Carl Theodor also began to emancipate<br />

himself from personal ties that had previously<br />

often restricted him. In 1758 his old Jesuit<br />

confessor died. In 1761, after almost twenty<br />

years of marriage, the Electress gave birth<br />

to a son that died in the same night. It was<br />

now clear that she would never have children<br />

again. From then on, the electoral couple<br />

began to drift apart. Carl Theodor was tired<br />

of his wife’s tantrums and her open display<br />

of affection for her lovers. He now took to<br />

several mistresses himself and fathered at<br />

least a dozen illegitimate children whom he<br />

II.<br />

Fig. 3: Mannheim, copperplate<br />

by J. A. Baertels, 1758 (From:<br />

Walter, Stadtgeschichte<br />

Mannheim, Mannheim 1907,<br />

vol. 1).<br />

11

II.<br />

12<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

provided well for. Moreover, Carl Theodor<br />

and Elisabeth Augusta had never had much in<br />

common, and the world of the enlightenment<br />

remained largely alien to the Electress. Even<br />

in their shared appreciation of music and<br />

theatre great divergencies began to appear:<br />

While Elisabeth Augusta retained her love for<br />

the Italian opera and the French theatre, Carl<br />

Theodor was, unlike Frederick the Great, quite<br />

open for the development of the German<br />

“movement”. The French actors were sent<br />

away, and, in 1775, he had the first German<br />

opera performed at his court. A year later<br />

the Elector founded the Mannheim National<br />

theater, a thoroughly modern, new type of<br />

court-institution, open to anyone who bought<br />

a ticket. Even before, the opera and the<br />

so-called “musical academies”, concerts of the<br />

famous Mannheim orchestra in the palace’s<br />

Rittersaal, had been open to the public – albeit<br />

a public that had to be well-dressed, educated<br />

and carefully scrutinized by court-officials<br />

before they were admitted.<br />

The new spirit of the age transformed Carl<br />

Theodor’s splendid court in many more<br />

ways. Enlightened criticism of idle court-life<br />

was uttered in the Elector’s presence even<br />

by his leading minister, and gradually, the<br />

number of extravagant entertainments<br />

was reduced, while at the same time a<br />

comprehensive system of scholarly and<br />

scientific associations was established: The<br />

Academy of Sciences (1763), to which was<br />

later added a meteorological branch with<br />

the first-ever world-wide system of weatherobservation-posts;<br />

the Academy of Sculpture<br />

and Painting; A ”German Society” which was<br />

much favoured by Carl Theodor who tried to<br />

promote the purity and development of the<br />

German language. Attached to the scholarly<br />

associations were various institutions housed<br />

in the palace or nearby, such as the library<br />

and the collections of paintings, drawings,<br />

minerals, coins etc. all supervised by experts<br />

and open to the public.<br />

The <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> gardens also changed<br />

their appearence: an English section began<br />

to “embrace” the French garden laid out in<br />

front of the palace. This addition of a new<br />

part reflecting the trends of the age, while<br />

still preserving the old baroque invention, can<br />

be seen as the most attractive expression of<br />

Carl Theodor’s ambiguous attitude towards<br />

old-style French absolutism and enlightened<br />

despotism. In his <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> gardens, a<br />

wonderful synthesis was reached which in<br />

his governance eluded him. In the 1780s,<br />

even the latest, pre-romantic fashion was<br />

included in the lay-out of the new part of the<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> gardens. Carl Theodor, who<br />

took a close interest in the development of<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, opened the gardens to his<br />

subjects to allow them to refine their tastes<br />

and manners by looking at beautiful things.<br />

The same happened with the extensive<br />

gardens surrounding the Oggersheim palace<br />

which, however, quite in tune with the<br />

differences in outlook between Carl Theodor<br />

and Elisabeth Augusta, were all in the French<br />

taste.<br />

Enlightened openness, however, did not<br />

mean a renunciation of class distinctions:<br />

Throughout his reign, the Elector would only<br />

accept as accompanying ”Gentlemen of the<br />

Bedchamber” men of old aristocratic origin.<br />

Court-balls were open to the Mannheim<br />

bourgeoisie – but they were kept apart from<br />

the nobility by a silk string partitioning<br />

the Rittersaal. Similarly, the reduction of<br />

entertainments did not mean their immediate<br />

end. No less than 20 % of the total revenue<br />

of the electoral territories were still spent on<br />

the maintenance of the court. It has to be<br />

kept in mind, however, that the new academic<br />

institutions and collections also remained<br />

part of the “court-machine” and thus their cost<br />

was part of the aforementioned amount. It<br />

is also true that Carl Theodor refrained from<br />

builiding a new palace in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> and,<br />

instead, placed the emphasis there on the<br />

enlargement of the gardens. The enormous<br />

sums necessary for the construction of an<br />

“à-la-mode”-summer residence were spent<br />

near Düsseldorf, where the new palace

of Benrath also served as an assertion of<br />

the Palatine claims on the lower-rhenish<br />

dukedoms in the face of Prussian threats.<br />

The End of Courtly Splendour<br />

When, during the end-of-year-service at<br />

the court chapel of his Mannheim palace,<br />

Carl Theodor received the news that he had<br />

inherited Bavaria, his first thought was: “Now<br />

the good days are over”. Required by the treaty<br />

of mutual succession to reside in Munich, he<br />

left Mannheim and <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. Only his<br />

wife, relieved at no longer having to keep up<br />

appearances, stayed behind, and kept a small<br />

court at Mannheim and Oggersheim. There<br />

still were some balls in winter in Mannheim,<br />

and rural “fêtes” during the Oggersheim<br />

summer. However, the excellent orchestra and<br />

the best singers had left for Munich; great<br />

court entertainments were a thing of the past.<br />

The refounded Nationaltheater and the<br />

collections that remained at the palace in<br />

Mannheim continued to attract large numbers<br />

of visitors, and the <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> gardens<br />

were not only maintained but enlarged. It<br />

all came to end when revolutionary armies<br />

swept through the electoral lands in the<br />

1790s. The treasures of the palace were taken<br />

to Munich, the court officials fled, and in<br />

1802 the Palatinate as a country ceased to<br />

exist. Carl Theodor, who during the 1780s had<br />

unsuccessfully tried to swap Bavaria for the<br />

Austrian Netherlands to create a “Kingdom of<br />

Burgundy” and had thus become extremely<br />

unpopular with his Bavarian subjects, died at<br />

the a table in Munich in February 1799.<br />

(Stefan Mörz)<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

II.<br />

13

II.<br />

Fig. 1: ‘Kleine Pfalzkarte’ (Small<br />

Map of the Palatinate), etching<br />

by Egidius Verhelst after Christian<br />

Mayer, 1773 (Heidelberg,<br />

Kurpfälzisches Museum).<br />

14<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

b)<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Summer Capital<br />

of the Electoral Palatinate<br />

Does anyone in the 21st century still use the<br />

expression summer residence? Surprisingly,<br />

to this day there are summer residences,<br />

where respective heads of government<br />

regularly spend the summer months and<br />

from which they also govern. One European<br />

absolute monarchy, the Vatican, uses Castel<br />

Gandolfo as a summer residence. The Pope,<br />

whoever he may be, publishes government<br />

proclamations there and receives cardinals<br />

and statesmen. For the French Presidency,<br />

former incumbent François Félix Faure (in<br />

office 1895-1899) developed Rambouillet<br />

into a “résidence de campagne” in 1896. It<br />

still serves as the summer seat of the French<br />

President, who does real politics there.<br />

Right into the 20th century, upper-class<br />

British Prime Ministers used their own<br />

stately home as their summer residence.<br />

Beginning with the first Labour Prime<br />

Minister Ramsay MacDonald (in office 1924<br />

and 1929-1935), the rural retreat of Chequers<br />

became the official summer residence of the<br />

British government. 1 Queen Elizabeth II, who<br />

formally still rules over the United Kingdom,<br />

spends 12 weeks of every summer at Balmoral<br />

Castle in Scotland. In this way she also makes<br />

an appearance as the Queen of Scotland and<br />

signs Acts of Parliament into law there. But<br />

the best known modern summer residence<br />

is presumably Camp David, which serves the<br />

President of the United States of America.<br />

Summer residences in the 18th century<br />

The expression “summer residence” does not<br />

seem to have been in general usage in the<br />

German language in the 18th century, since<br />

it is not listed in Zedler’s Universallexikon 2 .<br />

Instead, we will examine related concepts<br />

such as “court”.<br />

“Court is the term for where the prince is<br />

found”, Zedler explains 3 . Meanwhile, we find a<br />

definition for “residence” in Moser’s Hofrecht:<br />

“The residence is the proper, permanent home<br />

of the regent in the place that is the true seat<br />

of court and the colleges. This is the regent’s<br />

true home, and in the determination of<br />

ceremony and the establishment of its rules,<br />

it is proper to observe the usual practice of a<br />

residence; whereas at recreational and rural<br />

seats, much is left aside or allowed to slip.” 4<br />

In his Zeremonialwissenschaft, Rohr writes:<br />

“Occasionally Great Lords take a special liking<br />

to certain places in the country, and not only<br />

erect splendid palaces and pretty rural and<br />

recreational mansions for their plaisir at<br />

those selfsame places, but also order their<br />

high ministers and most distinguished court<br />

and military officials to likewise build their<br />

own there, in part that they may have them<br />

close at any time when they may require<br />

their counsel, or their other services, and in<br />

1 Kindly suggested by Prof. Michael Hesse, Universität Heidelberg.<br />

Chequers is an Elizabethan country manor near Princes<br />

Risborough in Buckinghamshire. It was given to the British<br />

nation in 1917 by Lord Lee of Fareham.<br />

2 Zedler’s Universallexikon is the best-known 18th-century<br />

German reference work, comparable with the Encyclopédie<br />

française, the first modern lexicon.<br />

3 Johann Heinrich Zedler: Grosses vollständiges Universal-<br />

Lexicon aller Wissenschaften und Künste. Halle, Leipzig 1732<br />

ff, volume XIII, 1735, p. 405.<br />

4 Friedrich Carl von Moser: Teutsches Hof-Recht. Franckfurt,<br />

Leipzig 1754, volume II, p. 252.

part also that thereby the places, which they<br />

wish to be built up, are peopled and provided<br />

with nourishment and custom. … When they<br />

are at their country manors, a great part of<br />

ceremony is set aside, and a freer style of life<br />

is chosen.” 5<br />

More recently, historians have tended to<br />

assume that the expressions “court” and<br />

“residence” are interchangeable. “Court” can be<br />

characterized by three elements:<br />

1. the presence of an aristocratic courtly<br />

society,<br />

2. the expression of grandeur and material<br />

splendour,<br />

3. the refinement and exemplary conduct<br />

court society compared with social groups<br />

not present at court. 6<br />

The residence is the place where the court is<br />

located regularly for extended periods and<br />

which then serves as the seat of government.<br />

Hence, residences also have properties that<br />

enable them at any given time to fulfil the<br />

requirements expected of the exercise and<br />

exhibition of power.<br />

An important criterion of exercising power<br />

is access to communication. A ruler at his<br />

residence must be able to receive messages<br />

from anywhere swiftly and reliably and<br />

communicate his decisions equally quickly<br />

to as many places and people in his realm<br />

as possible. Residences must, therefore, be<br />

located conveniently for transport, such as by<br />

important roads or rivers. 7<br />

The Electoral summer residence at<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

This important aspect also applies to the<br />

summer residence at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. During<br />

the reign of Prince-Elector Carl Theodor von<br />

der Pfalz (*1724; reigned 1743-1799), the road<br />

to the Palatinate capital Mannheim, the<br />

5 Julius Bernhard von Rohr: Einleitung zur Ceremoniel-Wissenschaft<br />

der Grossen Herren. Berlin 1733. Edited by Monika<br />

Schlechte. Leipzig 1990, p. 83 f.<br />

6 Aloys Winterling: Der Hof der Kurfürsten von Köln 1688-1794.<br />

Eine Fallstudie zur Bedeutung “absolutistischer” Hofhaltung.<br />

Bonn 1986, p. 2.<br />

7 Egon Johannes Greipl: Macht und Pracht. Die Geschichte der<br />

Residenzen in Franken, Schwaben und Altbayern. Regensburg<br />

1991, p. 9.<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

principle seat of residence, was developed<br />

into a highway, and a stage-post for changing<br />

horses was installed in Rheinau, today a<br />

suburb of Mannheim. This causeway is the<br />

continuation of the northern transverse axis<br />

through the circular parterre in the palace<br />

gardens at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. The road to the<br />

Palatinate’s old capital at Heidelberg, which<br />

had been built in the 17th century during<br />

the reign of Elector Carl Ludwig (*1617;<br />

reigned 1649-1680), was upgraded in the 18th<br />

century and mulberry trees were planted<br />

alongside to support the silk industry. This<br />

axis between the Königstuhl, an elevation<br />

outside Heidelberg, and the Kalmit, a<br />

peak in the highlands of the Pfälzer Wald,<br />

provided a key fundamental constant for<br />

court astronomer Johann Christian Mayer<br />

(*1719; †1783) as he surveyed the Palatinate.<br />

It was honoured in both of Mayer’s Palatine<br />

maps, which are among the most exact in<br />

the 18th century. Parts of this axis still form<br />

Carl-Theodor-Strasse and Kurfürstenstrasse<br />

in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> and also the bed of the<br />

former railway link between Heidelberg and<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. Finally, the axis survives as a<br />

path for ramblers and in the form of a runway<br />

used by the US armed forces.<br />

Following an extended visit by Elector<br />

Carl Theodor to his possessions on the<br />

Lower Rhine, the Duchies of Jülich and<br />

Berg with their residence at Düsseldorf, the<br />

Palatine rulers established a permanent<br />

residence. It was not until the court’s return<br />

from Düsseldorf in September 1747 that<br />

Mannheim was chosen for this role. The<br />

event found expression in an extension of the<br />

Mannheim palace and of the palace gardens at<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, and the printing of a Palatine<br />

court calendar. 8<br />

8 Stefan Mörz: Haupt- und Residenzstadt – Carl Theodor, sein<br />

Hof und Mannheim. Mannheim 1998, p. 44 ff.<br />

II.<br />

15

II.<br />

16<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

The Palace Square<br />

The village of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> also underwent<br />

planned development befitting the Elector’s<br />

summer residence. Under the guidance of<br />

the director of works, Galli da Bibiena (*1668;<br />

†1748), a manifest was proclaimed on 16 July<br />

1748, according to which anyone “intending<br />

to build in this district shall enquire with<br />

Mister da Bibiena after where to build, and<br />

implement and perfect the proposed building<br />

in accordance with the prescribed line and the<br />

elaborated plan.” 9 The construction of twostorey<br />

stone houses was designed to grant the<br />

village of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> the appearance of a<br />

baroque residence city.<br />

Bibiena based the dimensions of the new<br />

palace square on those of the cour d’honneur.<br />

The square is exactly as wide and twice as<br />

long as the court of honour. Its west side<br />

opens entirely onto the palace, while its<br />

eastern side is closed except for the width of<br />

the former mulberry avenue. A visitor arriving<br />

from Heidelberg steps out of the narrow<br />

avenue (now Carl-Theodor-Strasse) onto the<br />

wide square, at the far end of which is the<br />

palace. The latter, then, is both the visual focus<br />

(point de vue) and the portal to the palace<br />

gardens concealed beyond. The situation<br />

in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> is quite the opposite of<br />

that in Versailles or the fan arrangement in<br />

Karlsruhe, where the roads determining the<br />

layout of the town originate with the palace<br />

and thereby underline its dominant position.<br />

In <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> it is the palace that provides<br />

the endpoint for the road from Heidelberg. 10<br />

The pronounced formal simplicity of the<br />

square’s architecture does not indicate a<br />

lack of artistic imagination; rather, it is an<br />

intentional device which serves to emphasize<br />

the rural character of the summer residence.<br />

The Schlossplatz is a magnificent example<br />

of a unified square design from the mid-18th<br />

century. It forms a part of the urban plan for<br />

the Elector’s summer residence, which follows<br />

9 Generallandesarchiv (GLA) Karlsruhe 221/47 of 16 July 1748.<br />

10 Wiltrud Heber and Anneliese Seeliger-Zeiss: Der Schwetzinger<br />

Schlossplatz und seine Bauten: Veröffentlichungen zur<br />

Heidelberger Altstadt. Heidelberg 1974, p. 2.<br />

an axis towards the palace and the park. As<br />

an “ante-room” to the cour d’honneur, the<br />

square is indispensable and absolutely must<br />

be preserved as it is to uphold the historical<br />

appearance of the palace complex. 11 Despite<br />

changes in following centuries (conversions<br />

and additions to buildings, replacement of<br />

the mulberry trees by lime and chestnut), the<br />

square’s character largely reflects its condition<br />

in the time of Carl Theodor.<br />

The character of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> as a residence<br />

is also reflected in the Marstall 12 , the<br />

Gesandtenhaus 13 and the Pagenhaus 14 .<br />

Becoming the Palatine’s Summer Capital<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> had already been regularly used<br />

as a summer residence during the reign of<br />

Elector Carl Philipp (*1661; reigned 1718-<br />

1742). The Elector only arrived in his Palatine<br />

lands after briefly presiding in Neuburg<br />

on the Danube over his domain there. Carl<br />

Philipp then set up home in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>,<br />

before settling into his capital at Heidelberg.<br />

When the residence was officially relocated<br />

to Mannheim in 1720, <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> served<br />

as the residence almost all year round, as the<br />

palace at Mannheim was not ready for use<br />

until 1731. Up until then the Palatine court<br />

only had the use of a provisional and cramped<br />

interim residence in the Palais Oppenheim<br />

on Mannheim’s market square. As a result,<br />

the periods spent in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> were<br />

generously extended. 15<br />

Following the final designation of Mannheim<br />

as both capital and residence of the<br />

11 Heber p. 5.<br />

12 The “Stables” were built in 1750 as barracks for the Generalissimus<br />

of the Palatine army, Prince Friedrich Michael von Pfalz-<br />

Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld, the brother-in-law of the Electress.<br />

Elector Carl Theodor purchased them in 1759 and used them as<br />

a stable and coach house. Following the addition of shops, they<br />

function today as a department store.<br />

13 The “Legation” in Zeyherstrasse is now a district court.<br />

Originally a private house for Privy Counsellor von Jungwirth,<br />

who was the Elector’s doctor, it was bought by Elector Carl<br />

Philipp in 1732. It was used as accommodation for foreign<br />

ambassadors and was provided with a business apartment for<br />

Oberbaudirektor Nicolas de Pigage.<br />

14 Pages were sons of nobility receiving their training at court.<br />

The “Page House” in Zeyherstrasse is now part of the tax<br />

authority.<br />

15 Hans Schmidt: Kurfürst Karl Philipp von der Pfalz als<br />

Reichsfürst. Mannheim 1963.

Palatine Electorate in 1748, during the reign<br />

of Elector Carl Theodor, the Palatine court<br />

would leave Mannheim in the spring in<br />

order to spend the summer in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>.<br />

There is clear evidence of this in the missives<br />

of the Saxon envoy. Saxony’s ambassador<br />

Count Andreas Riaucour regularly reported<br />

on the migration of the Palatine court to<br />

the country at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, as he did on<br />

30 April 1771: “Mgr. L’Electeur part demain<br />

pour Schwezingen avec les personnes qui<br />

ont été nommées pour l’accompagner à celle<br />

Campagne, ou il restera pendant l’été jusqu’a<br />

l’arriere saison”. 16 Or on 23 April 1772: “Leur<br />

A.S.E. sont arrivées a cette compagne hier<br />

martin avec les personnes qui ont l’honneur<br />

de les accompagner du nombre des quels je<br />

me trouve Msg. L’Electeur y passera tout les<br />

tems de la belle saison”. 17 <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> even<br />

has its own court regulations worked out for<br />

the aristocracy, as Riaucour reports: “La cour<br />

d’ici a fait imprimer et publier un Reglement<br />

pour la Noblesse d’ici par rapport aux jours de<br />

cour et des tables pendant la Campagne d’Eté<br />

à Schwezingen de l’equel j’ai l’honneur de<br />

joindre ici un Exemplairem mais la Noblesse<br />

n’en est pas tops content.” 18<br />

The date of the move depended on the<br />

weather, but continually took place around<br />

the end of April and October respectively. At<br />

the very latest, the court needed to be back in<br />

Mannheim for the Elector’s name day on 4<br />

November, the day of St. Charles Borromeo,<br />

as this was when the gala commenced with<br />

great ceremony. Once, due to a “vent de Nord”,<br />

as Riaucour recounts, one May the Elector<br />

even retraced his steps to Mannheim, which<br />

presumably was easier to heat than the<br />

summer residence at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. 19<br />

An enormous logistical effort was required to<br />

move the residence to the countryside for half<br />

16 Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Loc 2626 Vol XXIV of<br />

23 April 1771.<br />

17 Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Loc 2627 Vol XXV of<br />

23 April 1772.<br />

18 Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Loc 2626 Vol XXIII of<br />

1 May 1770.<br />

19 Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Loc 2627 Vol XXV of<br />

12 May 1772.<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

the year (May to October). Food and firewood<br />

were brought in as corvée, since even items<br />

for everyday usage were not stored at the<br />

summer residence, but had to be delivered<br />

from Mannheim or those villages and offices<br />

charged with its supply. The baggage train<br />

from Mannheim carried linen, furniture,<br />

crockery and people in great quantities to<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. The English music critic<br />

Charles Burney reports: “The number of those<br />

who follow the Elector to <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> of a<br />

summer approaches fifteen hundred, all living<br />

in this tiny place at the Prince’s expense”. 20<br />

These 1,500 people descending onto the<br />

market village of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> in one fell<br />

swoop cannot be verified by other sources,<br />

but is presumably realistic. The year 1776 saw<br />

639 people recorded in the court calendar,<br />

all of whom were in the employ of the<br />

Palatine court. 21 Most household servants<br />

were married. However, their families were<br />

not entitled to live at the palace and would<br />

have had to find accommodation in town.<br />

It can safely be assumed that their families<br />

would not wish to spend half the year apart<br />

on a regular basis, and would therefore<br />

20 Charles Burney, Tagebuch einer musikalischen Reise durch<br />

Frankreich und Italien, durch Flandern, die Niederlande und<br />

am Rhein bis Wien, durch Böhmen, Sachsen, Brandenburg,<br />

Hamburg und Holland 1770 – 1772, reprint Wilhelmshaven<br />

1980, p. 228.<br />

21 Stefan Mörz p. 82.<br />

II.<br />

Fig. 2: The summer residence<br />

of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, aerial<br />

photograph. East (top) to west<br />

(bottom): The town, the palace,<br />

the gardens (Photo: LAD<br />

Esslingen, 2005).<br />

17

II.<br />

18<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

join the flow to the summer residence at<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>.<br />

The 70 to 80 aristocratic courtiers in turn<br />

had their own servants to look after them,<br />

who naturally also required accommodation<br />

in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>. This explains the high<br />

count of 1,500 people regularly migrating to<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> for the summer. The palace’s<br />

fairly modest buildings lacked space for the<br />

entirety of court society as well as servants<br />

and officials. For the period of their stay in<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, court servants were paid the<br />

cost of board and lodging if they stayed in<br />

burgher houses in town.<br />

Those that were only required occasionally<br />

in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> were paid travel money.<br />

Thus not all members of the court orchestra<br />

were present in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> all the time,<br />

but were only summoned there for certain<br />

performances. Government offices also<br />

retained their seat in Mannheim. But since<br />

the Elector as an absolute ruler needed to<br />

have all documents placed before him, state<br />

officials were constantly forced to commute<br />

to <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, since the business of<br />

government could not be left on hold during<br />

the six-month stay at the residence. This all<br />

ensured busy traffic along the sturdy highway<br />

to Mannheim.<br />

Accommodation registers from the years 1758<br />

and 1762 have been preserved. 22 In 1758 234<br />

courtiers could not be accommodated in the<br />

palace itself and were paid 4,442 guilders<br />

from the court treasury to cover the cost<br />

of their lodgings. The list also mentions at<br />

which houses the courtiers stayed. The people<br />

of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> obviously profited from<br />

the presence of court society in many ways.<br />

Not only could they rent out rooms and sell<br />

wares, but also participate culturally. Thus<br />

Burney reports: “The Elector has concerts at<br />

his palace every evening, if there is nothing<br />

playing at his theatre. When this occurs, not<br />

only his subjects but also any strangers have<br />

free Entrée. ... To anyone walking through<br />

the streets of <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> of a summer, it<br />

22 GLA Karlsruhe, Pfalz Generalia 77/8506.<br />

must seem as if it were purely a colony of<br />

musicians, practising their profession at all<br />

times; for in one house he would hear a fine<br />

violinist, there in another is a flute, and here<br />

a most excellent oboist, there a bassoon, a<br />

clarinet, a violoncello or a concert of all the<br />

instruments together.” 23<br />

Summer Residences in France?<br />

The French philosopher Voltaire (*1694;<br />

†1778) wrote of his stay in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> in<br />

1753: “Je suis actuellement dans la maison<br />

de plaisance de Mgr l’Èlecteur palatin.” 24 The<br />

“maison de plaisance” would be translated<br />

into German as a “Lustschloss”. Krause takes<br />

the expression “maison de plaisance” to mean<br />

a country house defined by its use, i.e. the<br />

kind of pleasures one might enjoy in the<br />

country, but not as not the hereditary seat<br />

of the family, a working estate or a hunting<br />

lodge. It is seen as a satellite in physical<br />

proximity to the principal residence. 25<br />

In France during the period of the “Ancien<br />

régime”, there was no official summer<br />

residence. Versailles established itself as the<br />

permanent seat of the court under Louis XIV.<br />

So that he could withdraw from Versailles<br />

and the court, small satellite châteaux were<br />

built for the French king and selected guests,<br />

initially the Trianon-de-porcellaine which<br />

was later replaced by the Trianon-de-marbre,<br />

the Petit Trianon and Marly. But there<br />

were still the great French royal palaces<br />

at Fontainebleau, St Germain-en-Lay and<br />

Compiègne, all of which provided enough<br />

space to accommodate the entire court.<br />

However, these palaces were only used<br />

temporarily by the French royal court, for<br />

example for an outing or during a hunt. 26<br />

23 Charles Burney, p. 228 f.<br />

24 Henry Anthony Stavan: Kurfürst Karl Theodor und Voltaire.<br />

Mannheim 1978, p. 8.<br />

25 Katharina Krause: Die Maison de plaisance – Landhäuser in der<br />

Île-de-France (1660-1730), München 1996, p. 8 ff.<br />

26 The spacious royal châteaux also had an assembly room, where<br />

governing was done and the court was usually present in its<br />

entirety, including the ministers. However, one cannot observe<br />

the same continuity and regularity as for the German summer<br />

residence, including unbroken accommodation for many<br />

months.

This is clear from the memoires of the<br />

Duke of Saint-Simon, and from the letters<br />

of Liselotte von der Pfalz and Madame de<br />

Sévigné. 27<br />

In the 18th century the French court still did<br />

not cultivate this regular habit of moving<br />

the residence lock, stock and barrel to a<br />

summer seat. Much as French fashion, art<br />

and architecture dominated West European<br />

culture, summer residences were a German<br />

phenomenon. 28<br />

The Imperial Court<br />

Only within the boundaries of the Holy<br />

Roman Empire of the German Nation is there<br />

evidence for summer residences that meet<br />

the criteria identified above. Here, it was the<br />

traditions of the Hapsburg Imperial Court in<br />

Vienna that were followed. Recent research<br />

was able to prove that the cultural hegemony<br />

of France was accepted and strictly emulated,<br />

but ceremony was always oriented towards<br />

the Imperial Court, where the old Spanish-<br />

Burgundian ceremonies held sway. 29<br />

During the reign of Emperor Karl VI<br />

(1711-1740), for example, the residence was<br />

constantly changing. Between the end of<br />

April and mid-May, the Imperial Court moved<br />

from the Hofburg in Vienna to Laxenburg,<br />

set in a waterscape outside town. At the end<br />

of June, following another brief sojourn in<br />

the Hofburg, the court moved again to spend<br />

the hot summer months at the Favorita on<br />

the Wieden. It was not until mid-October that<br />

the court returned to Vienna again, where it<br />

remained for the entire winter.<br />

The two palaces which the Emperor occupied<br />

with some of his court in the spring and<br />

summer are fully-fledged residences. The only<br />

matter of significance is that, under Karl VI,<br />

all ceremonial events without exception were<br />

27 Sigrid von Massenbach (ed.): Die Memoiren des Herzogs von<br />

Saint-Simon 1691-1723. Frankfurt am Main1990. Helmuth<br />

Kiesel: Briefe der Liselotte von der Pfalz. Frankfurt am Main<br />

1981. Theodora von der Mühll: Madame de Sévigné: Briefe.<br />

Baden-Baden 1979.<br />

28 The other countries of Europe have not been included in this<br />

exposé.<br />

29 Henriette Graf: Die Residenz in München. Hofzeremoniell,<br />

Innenräume und Möblierung von Kurfürst Maximilian I. bis<br />

Karl VII. München 2002; Brigitte Langer: Pracht und Zeremoniell<br />

– die Möbel der Residenz München. München 2002.<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

performed as exactly as they would have been<br />

in the Hofburg. Imperial lords were invested<br />

with fiefs and state receptions were held, such<br />

as for Peter the Great, the Tsar of Russia. This<br />

in itself qualifies them as summer residences,<br />

distinguishing them from hunting lodges and<br />

any occasional visits a foreign prince may<br />

have paid to any other palace. 30<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> as a Typical Summer Residence<br />

This definition also applies to <strong>Schwetzingen</strong>.<br />

Carl Theodor consistently held ministerial<br />

conferences at <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> and received<br />

eminent guests, such as the bishops of Speyer<br />

(August Philipp, Count of Limburg-Styrum),<br />

Hildesheim (Friedrich Wilhelm of Westphalia)<br />

and Augsburg (Joseph, Landgrave of Hesse-<br />

Darmstadt), Princess Christine of Saxony,<br />

Princess-Elector Maria Antonia of Saxony,<br />

Duke Carl of Courland, the Electors of Mainz<br />

(Emmerich Josef von Breidbach-Bürresheim<br />

and Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal), the<br />

Elector of Trier (Clemens Wenzeslaus, Duke<br />

of Saxony), the Radziwiłł princes as well as<br />

relatives from Zweibrück and Bavaria.<br />

Even during the summer months in<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>, the Privy Conference, which<br />

was the assembly of Palatine ministers chaired<br />

by the Elector, met almost daily. Unless the<br />

conference was in recess, between mid-July<br />

and mid-August, ministers had to remain in<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> at all times or commute there<br />

from Mannheim. 31 Even during the holidays,<br />

the cabinet secretary was permanently on<br />

hand in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> to take care of the dayto-day<br />

running of government affairs together<br />

with Carl Theodor.<br />

This characteristic feature of a residence<br />

finds expression in the form of an assembly<br />

or conference room. Since <strong>Schwetzingen</strong><br />

Palace was rather modest and actually lacked<br />

space on the “belle étage” where the Electoral<br />

couple lived, the conference room also served<br />

30 Andreas Pécar: Die Ökonomie der Ehre. Der höfische Adel am<br />

Kaiserhof Karls VI. (1711-1740). Darmstadt 2003, p. 158 f.<br />

31 Kindly mentioned by Stefan Mörz, head of the town archives<br />

in Ludwigshafen.<br />

II.<br />

19

II.<br />

20<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

as an antechamber and games room. 32 The<br />

conference table, like all tables in the 18th<br />

century, consisted of two trestles and a top,<br />

which was covered with tapestry silk. This<br />

mobile furniture cold be quickly disassembled<br />

and replaced by games tables, so that the<br />

room could be used as a games room by<br />

court society in the evenings. The inventory<br />

officially lists the room as a conference<br />

room – a facility which would have been<br />

expendable in a palace that did not serve as a<br />

residence.<br />

Following the war and turmoil of the 17th<br />

century, almost all the European rulers were<br />

keen to construct further palaces in addition<br />

to their principal residence, not only to lend<br />

greater splendour to their rule with the aid of<br />

prestigious architecture, but also to include<br />

the broader surroundings into the projection<br />

of their princely status. And so the residence<br />

became a landscape, following the example of<br />

the “villeggiatura” in Renaissance Italy.<br />

We can conclude that from 1718 to 1778<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> was the place where the<br />

Palatine Elector’s court regularly spent the<br />

summer. By rights, <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> could<br />

be described as the summer capital of the<br />

Palatine Electorate. Capitals are national<br />

symbols. They can showcase the power of<br />

a state and become focal points for public<br />

culture. Above all, they are the results of<br />

historical development manifested in their<br />

architecture, just as <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> proudly<br />

represents a 60-year period in the 18th<br />

century 33 .<br />

(Ralf Richard Wagner)<br />

32 Indeed, in its present role as part of the palace museum it is<br />

furnished as a multi-functional room. The wall coverings are<br />

of red and gold silk moiré and prestigious portraits of Carl<br />

Theodor and Elisabeth Augusta hang on the walls with the<br />

official crest of the Palatinate.<br />

33 Bernd Roeck: Staat ohne Hauptstadt. Städtische Zentren im<br />

Alten Reich der Frühen Neuzeit. In: Hans-Michael Körner;<br />

Katharina Weigand (ed.): Hauptstadt. Historische Perspektiven<br />

eines deutschen Themas. München 1995, pp. 59-72.

c)<br />

Musical Life at the Court of<br />

Elector Carl Theodor from 1743<br />

to 1778<br />

With generous patronage from Elector Carl<br />

Theodor, who was a great music-lover, an<br />

abundance of first-rate musical activity,<br />

hardly equalled in all Europe, unfolded at<br />

the Palatine court. Christian Friedrich Daniel<br />

Schubart described the court as the “Germans’<br />

musical Athens” 1 , and its orchestra was held<br />

by contemporaries to be the best in Europe.<br />

Its legendary reputation was founded on its<br />

size, discipline, great technical skill, modern<br />

organizational methods with rewards for good<br />

performance, and the fact that no other court<br />

orchestra of the day boasted more individuals<br />

who were at once composers and virtuosi.<br />

The Structure of Musical Life at the Court 2<br />

Church music<br />

Thanks to the “Palatinate’s Court and Official<br />

Diary”, extant from 1748, a fairly clear and<br />

constant structure can be discerned for church<br />

music. It was governed by the calendar of<br />

high days and holy days 3 . On all Sundays<br />

and holidays, it seems, the sermon would be<br />

followed by the “Musical High Mass”, and<br />

in the evenings, before and after the holy<br />

blessing, the “Lauretan Litany was also sung<br />

through to music” 4 . As illustrated, for example,<br />

1 Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart: Deutsche Chronik, 53.<br />

Stück, 29. 9. 1774, p. 423.<br />

2 For further details: Bärbel Pelker: Zur Struktur des Musiklebens<br />

am Hof Carl Theodors in Mannheim, in: Mozart und<br />

Mannheim. Kongressbericht Mannheim 1991 (= Quellen<br />

und Studien zur Geschichte der Mannheimer Hofkapelle 2),<br />

edited by Ludwig Finscher, Bärbel Pelker and Jochen Reutter.<br />

Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 29-40.<br />

3 Further literature on the Court Diaries: Eduard Schmitt:<br />

Die Kurpfälzische Kirchenmusik im 18. Jahrhundert. Diss.<br />

Heidelberg 1958; Jochen Reutter: Die Kirchenmusik am<br />

Mannheimer Hof, in: Die Mannheimer Hofkapelle im Zeitalter<br />

Carl Theodors, edited by Ludwig Finscher. Mannheim 1992, pp.<br />

97-112; Johannes Theil: ... unter Abfeuerung der Kanonen. Gottesdienste,<br />

Kirchenfeste und Kirchenmusik in der Mannheimer<br />

Hofkapelle nach dem Kurpfälzischen Hof- und Staatskalender.<br />

Norderstedt 2008.<br />

4 Chur-Pfältzischer Hoff- und Staats-Calender, 1749, “Anmerckungen”,<br />

fol. A 2r. References such as “musically sung” and<br />

“Musical High Mass” presumably – not least in the light of the<br />

known repertoire – mean the performance of church compositions<br />

in concert form, calling for the participation of both<br />

departments of court music: the singers and the instrumentalists.<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

by the liturgical compositions of Carlo Grua<br />

and Ignaz Holzbauer, it was a kind of local<br />

custom to say Mass without the Benedictus<br />

and play the organ instead. On high days, such<br />

as the birthdays and name days of the Elector<br />

and his Lady Consort, High Mass took a<br />

particularly solemn form, and according to the<br />

description in the Court Diary a Te Deum was<br />

sung after the Elevation rather than playing<br />

the organ. Another feature of these high days<br />

was to accompany the Gloria, the Te Deum<br />

and the final blessing with canon firing from<br />

the ramparts of the fortress.<br />

An interesting hierarchy can be established<br />

for certain holidays. Apart from holy worship<br />

on the occasions mentioned above, Easter<br />

Week was the most important and also the<br />

most comprehensive liturgical event, and<br />

members of court were expected to dress<br />

in mourning for it. The ceremonial details<br />

were painstakingly set out every year in the<br />

Court Diary for all to note. One of the musical<br />

highlights was without any doubt the Good<br />

Friday oratorio, which was performed at<br />

about eight or nine o’clock in the evening<br />

with a large number of performers (solo<br />

singers, choir and orchestra). The tremendous<br />

significance of this performance is born out<br />

II.<br />

Fig. 1: Elector Carl Theodor<br />

with flute traverse (Photo:<br />

Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen,<br />

Mannheim).<br />

21

II.<br />

22<br />

II. <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> – Elector Carl Theodor’s Summer Residence<br />

both by the specially printed libretti and the<br />

fact that the title and composer have been<br />

preserved in all the relevant archive materials<br />

that have survived 5 , items that usually went<br />

unmentioned when church music was<br />

performed 6 .<br />

Three church holidays were distinguished by<br />

the fact that, in addition to the musical Mass,<br />

Evensong took the form of a second musical<br />

service: Epiphany on 6 January, Easter Sunday<br />

and Christmas Day. The calendar year was<br />

brought to an end by a solemn Thanksgiving,<br />

and the ceremonial Te Deum would be sung<br />

in the presence of the entire court.<br />

Secular Music<br />

Structuring the annual theatre and concert<br />

programme at the Elector’s court was far more<br />

difficult, especially as numerous visits by<br />

high-ranking personages, and the consequent<br />

effort invested in parading all the official<br />

magnificence of court, made it impossible<br />

to maintain an even rhythm. According<br />

to the court diaries, the basic skeleton for<br />

the calendar was formed by their lordships<br />

birthdays and name days and the Carnival<br />

period. From 1748 to 1762 there were eight<br />

official court festivals. There were the grand<br />

galas to honour the Elector and his wife, and<br />

also less splendid name days and birthdays<br />

for Prince Friedrich Michael von Zweibrücken<br />

(1724–1767) and his wife, Princess Maria<br />

Franziska, with a smaller gala held at court<br />

and either a ballet pantomime or a French<br />

play. From 1763 the festivities were cut<br />

back, and ultimately by 1769 the only major<br />

spectacles accompanied the name days of the<br />

Elector and his wife on 4 and 19 November.<br />

5 Riaucour-Akte 1748–1778 (Dresden, Hauptstaatsarchiv, Loc.<br />

2622–2628, 31 vols.), Traitteur-Akte (München, Bayerisches<br />

Hauptstaatsarchiv, Abt. III, Geheimes Hausarchiv, Korr. Akt 882<br />

V b) and Tagebuch des Freiherrn von Beckers 1770, 1775, 1776,<br />

1777 (München, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Kasten blau<br />

1/57 and Kasten blau 433/7 ½).<br />

6 List of oratorios performed in, inter alia: Friedrich Walter:<br />

Geschichte des Theaters und der Musik am Kurpfälzischen<br />

Hofe, Leipzig 1898, pp. 365-367; Karl Böhmer: Das Oratorium<br />

Gioas, re di Giuda in den Vertonungen von Johannes Ritschel<br />

(Mannheim 1763) and Pompeo Sales (Koblenz 1781), in:<br />

Mannheim – Ein Paradies der Tonkünstler? Kongressbericht<br />

Mannheim 1999 (= Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der<br />

Mannheimer Hofkapelle 8), edited by Ludwig Finscher, Bärbel<br />

Pelker, Rüdiger Thomsen-Fürst. Frankfurt am Main 2002, pp.<br />

227-251, esp. p. 250.<br />

Protocol on these days called for a “great gala<br />

at court” 7 . After the festive church service<br />

described earlier, an open table was kept.<br />

Until 1756 a major opera would be performed<br />

on the same day at around five in the evening.<br />

From 1757 the first day ended with a “Grand<br />

Apartement”, and the opera then became<br />

the central event of the second day. This<br />

arrangement gave rise to an additional, fourth<br />

day of celebrations, and the tone would be set<br />

on the following days by the “Gala Academy”<br />

(a big court concert lasting up to four hours)<br />

and the “Gala Comedy” (a French play<br />

combined with a ballet), a pattern upheld until<br />

1771. However, when the court galas were<br />

confined to the two name days, the festivities<br />

became even more intense, with the inclusion<br />

of a second opera.<br />

The Carnival period provided the second<br />

constant feature in musical life at the court.<br />

To begin with, the weekly programme, which<br />

usually began on 6 January, included: the<br />

“Grand Apartement”, two masque balls, a play<br />

and the opera on Sunday (although when the<br />

festivities reached their peak, the opera would<br />

be postponed as an exception until Monday,<br />

flanked by masque balls). Until 1752 the<br />

birthday opera for the Electress (17 January)<br />

was simultaneously the Carnival opera that<br />

year; from 1753 the festive opera performed<br />

on the Elector’s name day (4 November) was<br />

designated the Carnival opera for the following<br />

year. No year went by without the regular<br />

masque ball and opera, but they were joined<br />

from 1753 by the first “Musical Academy”,<br />

which was then retained as an annual feature.<br />

In the latter half of the fifties, the “Grand<br />

Apartement” was dropped, and from 1772 the<br />

play also went by the board. The definitive<br />

Carnival reglement was published every year<br />

in the “Mannheimer Zeitung” and circulated<br />

around the court and to the general public on<br />

little printed hand-outs 8 .<br />

7 Chur-Pfältzischer Hoff- und Staats-Calender, 1749, unpaginated.<br />

8 Illustration of two printed programmes with the “Reglement du<br />

Carneval”, in: Pelker: Zur Struktur des Musiklebens, p. 36. Count<br />

Riaucour (Riaucour-Akte, 1748–1778) and the Ministers of the<br />

Electorate regularly published announcements of the Carnival<br />

amusements, and these have been preserved from 1754 (München,<br />

Bayerisches Staatsarchiv, Gesandtschaft Wien, Gesandtschaft Berlin).

The Two-Season Structure: Winter and<br />

summer<br />

When the second court theatre opened at<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong> in summer 1753, the annual<br />

pattern of musical life at the court was<br />

radically restructured 9 . Up until this point,<br />

it had been the custom to launch the theatre<br />

season with a new opera to mark the birthday<br />

of the Elector’s wife on 17 January. With a<br />

second opera house available, musical life<br />

started to be divided into two seasons: winter<br />

in Mannheim from November to early May,<br />

and summer in <strong>Schwetzingen</strong> from early May<br />

until the end of October.<br />

The Winter Season in Mannheim<br />

The winter season bore all the traces of<br />

splendour and magnificence that the court<br />

liked to demonstrate in public. The supreme<br />

highlight was a new, grandiose opera which,<br />

until 1752, would remain the only opera of<br />

the winter season. Visitors attending the<br />

lavish name day celebrations for the Elector<br />

and Electress described above would arrive in<br />

Mannheim towards the end of October and<br />

usually remain until the end of the Carnival<br />

period, and this enabled them to obtain seats<br />

for the opera as early as possible. The upper<br />

circle of the opera house in the western wing<br />

of Mannheim Palace was open to members of<br />

the public 10 . The festive opera was famous for<br />

its exceedingly sumptuous sets and costumes:<br />

as the libretti show, there were at least eight<br />

backdrops, and after each Act there would be<br />

a ballet with its own independent plot, its own<br />

printed programme, „specially composed music<br />

and separate stage sets. These stately spectacles<br />

would involve more than a hundred performers.<br />

9 This conclusion is based above all both on the surviving libretti,<br />

which state on the title page what occasion to be marked<br />

by the festive opera, and on the envoys’’ reports, which are the<br />

most reliable source of dates and operatic performances in<br />

<strong>Schwetzingen</strong>; apart from the Riaucour file, the envoys’ reports<br />

by ministers of the Palatinate are relevant to the years 1748 to<br />