Les Arts Florissants - Barbican

Les Arts Florissants - Barbican

Les Arts Florissants - Barbican

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Pascal Gély<br />

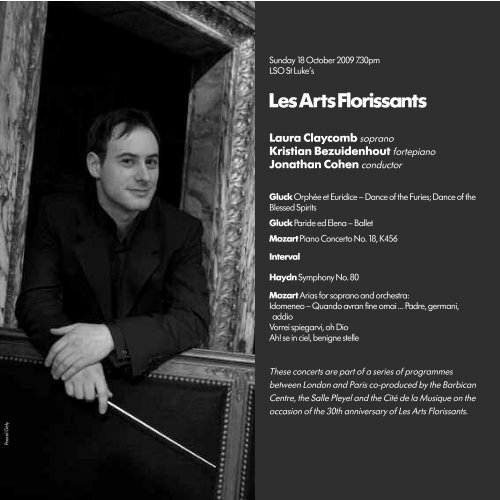

Sunday 18 October 2009 7.30pm<br />

LSO St Luke’s<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong><br />

Laura Claycomb soprano<br />

Kristian Bezuidenhout fortepiano<br />

Jonathan Cohen conductor<br />

Gluck Orphée et Euridice – Dance of the Furies; Dance of the<br />

Blessed Spirits<br />

Gluck Paride ed Elena – Ballet<br />

Mozart Piano Concerto No. 18, K456<br />

Interval<br />

Haydn Symphony No. 80<br />

Mozart Arias for soprano and orchestra:<br />

Idomeneo – Quando avran fine omai … Padre, germani,<br />

addio<br />

Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio<br />

Ah! se in ciel, benigne stelle<br />

These concerts are part of a series of programmes<br />

between London and Paris co-produced by the <strong>Barbican</strong><br />

Centre, the Salle Pleyel and the Cité de la Musique on the<br />

occasion of the 30th anniversary of <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong>.

introduction<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> at 30<br />

What a difference a generation makes. In the past 30 years, the world of Baroque music-making has been transformed.<br />

Musicians had for a while been acquiring the skills of playing old instruments and rediscovering former playing styles, but it<br />

was only during the 1970s that these made a major impact on the wider public. Of course there had been pioneers before<br />

this: a whole generation of enthusiasts and researchers had explored old repertory, and Arnold Dolmetsch had played his<br />

clavichord in candlelit London drawing rooms to the delight of George Bernard Shaw and Percy Grainger. But this was<br />

essentially an esoteric activity – until a new generation of players and conductors launched themselves into the re-creation of<br />

Baroque ensembles in the 1970s.<br />

William Christie’s achievement with his French group <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> from 1979 onwards has been an outstanding part of<br />

this revival, for it grew out of a repertory that many had thought inaccessible – the distant world of the French Baroque, with<br />

its rich and dense texts, its complex ornamentation and rhetoric, and its unfamiliar emotional language. What Christie and<br />

his young ensemble achieved in spectacular fashion was to show how, when performed with penetrating understanding and<br />

vivid communication, this music could be made as available and exciting as any on offer. From Charpentier (who gave the<br />

ensemble its name) and Lully through to Rameau, <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> lit up this music and brought it to life with unparalleled<br />

success.<br />

Christie’s ensemble has moved from the French Baroque into Handel and Purcell, Monteverdi and Landi, and beyond that to<br />

Haydn and Mozart. It has gained a huge following for its fresh insights into Haydn’s The Creation and Monteverdi’s Vespers,<br />

and its staged operas here at the <strong>Barbican</strong> – the fantastical, video-dominated production of Rameau’s <strong>Les</strong> Paladins and Luc<br />

Bondy’s severely intense staging of Handel’s Hercules – have been among the highlights of our output.<br />

So it is appropriate that this anniversary season celebrates the historic achievement of <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> with opera<br />

(Purcell’s immortal Dido and Aeneas), oratorio (Handel’s rarely performed Susanna) and the French choral motets that the<br />

group has made its own. And it is also entirely typical of its work with younger artists that for two of these anniversary<br />

concerts, William Christie hands the baton on to directors of the next generation, Jonathan Cohen and Paul Agnew. Like the<br />

great music of the past, <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> will continue to reinvent itself as it looks towards the next 30 years.<br />

Nicholas Kenyon<br />

Managing Director<br />

2

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong><br />

30th Anniversary<br />

Celebration<br />

William Christie and his ensemble present<br />

an exciting and diverse musical showcase<br />

celebrating their 30th anniversary<br />

Sun 18 Oct 09 7.30pm<br />

LSO St Luke’s<br />

Jonathan Cohen conducts<br />

Haydn’s Symphony No 80 and<br />

music by Mozart and Gluck.<br />

Returns only<br />

Sun 25 Oct 09 7pm<br />

A performance of Handel’s<br />

rarely-heard oratorio Susanna<br />

with soloists including William<br />

Burden, Alan Ewing and<br />

Sophie Karthäuser.<br />

Sun 8 Nov 09 7.30pm<br />

Union Chapel<br />

Talented British conductor and<br />

tenor Paul Agnew leads this<br />

performance of Monteverdi’s<br />

Sixth Book of Madrigals.<br />

Thu 26 Nov 09 7.30pm<br />

Grand Motets by Lully, Rameau,<br />

Desmarest and Campra with<br />

soloists including Patricia<br />

Petibon and Toby Spence.<br />

Watch video interviews and listen to music clips<br />

at www.greatperformers.org.uk<br />

Box Office 0845 120 7557<br />

The <strong>Barbican</strong> is<br />

provided by the<br />

City of London<br />

Corporation

programme note<br />

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87)<br />

Orphée et Euridice (1774)<br />

Dance of the Furies; Dance of the Blessed Spirits<br />

Elena ed Paride (1770)<br />

Ballet<br />

When the Emperor Francis I and his retinue heard Gluck’s<br />

Orfeo ed Euridice in Vienna’s Burgtheater on 5 October<br />

1762 they were doubtless expecting a lightweight pastoral<br />

entertainment. The occasion – the Emperor’s name-day –<br />

and the opera’s billing as an azione teatrale (‘theatrical<br />

action’) promised as much. What they got was a work of<br />

startling originality and emotional power that integrated<br />

chorus, soloists and ballet in dramatic complexes and broke<br />

down the clear-cut division between recitative and aria.<br />

Gluck’s librettist Ranieri de’ Calzabigi was a disciple of the<br />

French Enlightenment, and a passionate opponent of the<br />

artifices and excesses of Italian opera, as was the composer.<br />

Calzabigi took the archetypal myth of Orpheus’s descent to<br />

Hades to rescue Euridice and pared it down to essentials;<br />

Gluck’s music was correspondingly strong and direct, shorn<br />

of rococo frills and fripperies. The composer’s watchwords<br />

were dramatic truth and ‘beautiful simplicity’: no more<br />

pandering to the whims of overindulged and overpaid star<br />

singers. From the solemn opening chorus onwards, his music<br />

makes its effect with swift, shattering economy.<br />

In 1774 Gluck revised and expanded Orfeo as Orphée et<br />

Euridice, adding new arias and ballet numbers, including<br />

the ‘Dance of the Furies’, for dance-mad Paris, but diffusing<br />

the elemental force of the original. In Vienna the hero – part<br />

symbolic demigod, part human lover – had been sung by the<br />

castrato Gaetano Guadagni. The French deemed castratos<br />

an offence against nature, so Gluck duly reworked the role<br />

for the celebrated haute-contre (high tenor) Joseph Legros,<br />

in the process making Orpheus a more heroic figure.<br />

In the first scene of Act 2, Orpheus has subdued the Furies<br />

with the eloquence of his singing. After he has passed<br />

4<br />

through the gates of Hades, they revert to their true nature in<br />

a thrilling, torrential D minor dance. An inveterate recycler,<br />

Gluck lifted this ‘Air de Furies’ from his 1761 ballet Don Juan.<br />

It became one of his most famous movements, and a crucial<br />

influence on the Sturm und Drang (‘Storm and Stress’)<br />

symphonies of Haydn, Mozart and others. Stygian darkness<br />

yields to the pure, dazzling light of the Elysian Fields in the<br />

‘Dance of the Blessed Spirits’, an F major minuet of unearthly<br />

serenity. For Paris Gluck added, as a central trio, a sinuous<br />

D minor flute solo that leaves an aftertaste of sadness.<br />

A flop at its Viennese premiere in 1770, Gluck’s third socalled<br />

‘reform’ opera, Paride ed Elena, has always<br />

remained in the shadows. Where its predecessors, Orfeo<br />

and Alceste, are dramas of life and death, Paride ed Elena<br />

deals with Paris’s wooing of Helen. Cupid pulls the strings,<br />

while Athene appears as a malign dea ex machina with a<br />

prophecy of future carnage, which the lovers then blithely<br />

disregard. Paride ed Elena is even more static than Alceste,<br />

and suffers from having an all-soprano cast – prime reasons<br />

for its neglect. But much of the music is glorious. Variety<br />

comes from Gluck’s portrayal of the two national characters,<br />

Sparta and Troy. The Trojan Paris sings music in Gluck’s most<br />

ravishing vein, while Helen, far from being the sex-kitten of<br />

popular myth, maintains a certain Spartan aloofness until<br />

her final capitulation.<br />

Gluck magnified these national contrasts in the opera’s<br />

splendid choruses and ballet music. In the five-movement<br />

ballet sequence in Act 1, three brusque, angular dances for<br />

the Spartans alternate with two beguiling numbers for the<br />

Trojans: a gavotte that Gluck later recycled for the French<br />

version of Orfeo, and a dulcet minuet – something of a<br />

Gluck speciality.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91)<br />

Piano Concerto No. 18 in B flat major, K456 (1784)<br />

1 Allegro vivace<br />

2 Andante un poco sostenuto<br />

3 Allegro vivace<br />

Kristian Bezuidenhout fortepiano<br />

When Mozart departed the service of the hated Archbishop<br />

Colloredo of Salzburg in 1781, helped by history’s most<br />

famous kick up the backside, he was confident that fame<br />

and fortune in Vienna were his for the taking. For the next<br />

few years he was triumphantly vindicated in what he dubbed<br />

‘the land of the clavier’, earning a handsome living from<br />

teaching, publishing his works and giving concerts. Though<br />

Mozart spent almost as fast as he earned, he was for a time,<br />

at least, a shrewd business operator; and he promoted<br />

himself as both performer and composer in the magnificent<br />

series of piano concertos he premiered at his own<br />

subscription concerts, held during Lent and Advent and<br />

attended by the Viennese social and musical elite.<br />

Mozart entered the B flat Concerto, K456, in his thematic<br />

catalogue on 30 September 1784. While the evidence is not<br />

watertight, he seems to have intended the work not only for<br />

his own use but also for the blind pianist Maria Theresia<br />

Paradies to perform in Paris. Mozart probably introduced<br />

the concerto to the Viennese at a Lenten subscription concert<br />

on 13 February 1785. Three days later Leopold Mozart,<br />

visiting his son and daughter-in-law in their apartment in the<br />

most fashionable quarter of Vienna, described the event to<br />

his daughter Nannerl: ‘Your brother played a glorious<br />

concerto … I had the great pleasure of hearing all the<br />

interplay of the instruments so clearly that tears of sheer<br />

delight came to my eyes. When your brother left the stage the<br />

Emperor tipped his hat and called out “Bravo, Mozart!” and<br />

when he came on to play there was huge applause.’<br />

Like all Mozart’s Viennese concertos, K456 is a wonderful<br />

amalgam of keyboard virtuosity, symphonic organisation<br />

and vivid operatic characterisation. The opening Allegro<br />

programme note<br />

vivace begins with one of the composer’s favourite march<br />

gambits, though it is immediately apparent that these are toy<br />

soldiers. Mozart’s use of woodwind, as an independent<br />

group of ‘characters’, is especially piquant: and many of the<br />

movement’s playful, epigrammatic themes are fashioned as<br />

dialogues between wind and strings, and between the<br />

various members of the wind group. The diatonic chirpiness<br />

of the opening is offset by a louring chromatic passage in<br />

B flat minor, with the woodwind playing in gaunt octaves<br />

against stabbing accents from the strings. Typically, when<br />

Mozart brings back this passage in the solo exposition he<br />

makes it even more dramatic, with sweeping keyboard<br />

arpeggios.<br />

This momentary darkening of mood foreshadows the<br />

Andante second movement, a theme and five variations in<br />

Mozart’s favourite ‘pathetic’ key of G minor. The first three<br />

variations chart a gradual increase of tension; and in the<br />

third the forlorn piano entreats the implacable orchestra like<br />

some tragic operatic heroine. The fourth variation then turns<br />

to G major for a vision of pastoral innocence, coloured by<br />

luminous woodwind writing. The poignant coda equivocates<br />

between major and minor in a way it would be tempting to<br />

call Schubertian were it not equally characteristic of Mozart.<br />

Introspection is summarily banished by the finale, a<br />

boisterous 6/8 ‘hunting’ rondo whose main subject seems to<br />

mock the theme of the Andante. Midway through the<br />

movement Mozart springs the concerto’s biggest surprise,<br />

spiriting the music to an exotically remote B minor, and<br />

setting up a clash of metre, with the orchestra (first bassoon<br />

to the fore) playing in 2/4 against the soloist's 6/8 before<br />

roles are reversed.<br />

5

programme note<br />

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)<br />

Symphony No. 80 in D minor (1783–4)<br />

1 Allegro spiritoso<br />

2 Adagio<br />

3 Menuetto<br />

4 Finale: Presto<br />

During the 1780s Haydn led something of a double life as<br />

provincial Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Nicolaus<br />

Esterházy and an international celebrity whose symphonies,<br />

quartets and piano trios were in demand throughout<br />

northern Europe. Publishers in the 18th century liked to issue<br />

instrumental works in batches of three or six; and beginning<br />

with Nos 76–8 of 1782 – designed for an aborted visit to<br />

London – all Haydn’s later symphonies were written in sets<br />

for consumption beyond the Esterházy court. The triptych<br />

Nos 79–81 from 1783–4, published more or less<br />

simultaneously in Vienna, Paris and London, proved even<br />

more popular than the 1782 symphonies. With his by now<br />

shrewdly developed commercial sense, Haydn secured<br />

additional profit from sales to publishers in Lyon and Berlin,<br />

and, true to form, sold ‘exclusive’ manuscript copies to<br />

several patrons in Austria and Germany. Two of the<br />

symphonies (we do not know which) were performed at<br />

a concert of the Viennese Tonkünstler-Societät in March<br />

1785, in a programme that also included Mozart’s cantata<br />

Davide penitente.<br />

In sets of three or six symphonies and quartets it was<br />

customary to include one work in the minor key: Haydn’s No.<br />

83, ‘La poule’ in the Paris set (1785–6), and Mozart’s G minor<br />

Symphony No. 40 are cases in point. Whereas the flanking<br />

major-key symphonies of the 1783–4 triptych, Nos 79 and 81,<br />

are essentially popular in tone, the tensions inherent in the<br />

minor mode make No. 80 a more expressively complex work.<br />

No Haydn symphony movement juxtaposes the vehement<br />

and the flippant as disconcertingly as the opening Allegro<br />

spiritoso. For most of its course the exposition lives up to the<br />

expectations aroused by the turbulent opening theme,<br />

ground out by cellos and basses against frenzied violin<br />

6<br />

tremolos. Then, at the last moment, Haydn introduces a<br />

comically trivial Ländler tune that, but for its irregular<br />

phrasing (four plus three bars), could have drifted in from a<br />

Viennese beer garden. Despite a ferocious burst of activity<br />

from the main theme, the Ländler dominates the<br />

development, turning up in various remote keys (starting with<br />

D flat major) separated by quizzical silences. The<br />

recapitulation, as usual in late Haydn, radically reworks the<br />

events of the exposition, varying and developing the main<br />

theme before plunging to D major and giving the Ländler the<br />

last word, its phrasing now ‘normalised’ into four plus four<br />

bars. In the process a movement that had begun in strenuous<br />

Sturm und Drang mode ends in the utmost levity: just the kind<br />

of thing that offended po-faced North German critics during<br />

Haydn’s lifetime.<br />

The sonata-form Adagio, in B flat, also lives on extreme<br />

contrasts. Its serene, gracious opening melody is ruffled by<br />

an agitated tutti, with swirling sextuplets in second violins and<br />

violas. The development, beginning with the main theme in<br />

B flat minor and reaching an impassioned climax in G minor,<br />

rises to a higher pitch of dramatic intensity than any previous<br />

Haydn symphony slow movement. Back in D minor, the stern<br />

minuet (whose stalking theme distantly recalls the symphony’s<br />

opening) encloses a beautiful D major trio that sets an<br />

ancient Gregorian chant against a restless, chromatically<br />

inflected accompaniment. If the two middle movements are<br />

wholly serious, Haydn the humorist takes immediate control<br />

in the scintillating, quixotic finale. The syncopated opening,<br />

fashioned so that we do not initially hear it as syncopated, is<br />

one of the composer’s best rhythmic jokes.<br />

Programme notes © Richard Wigmore

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart<br />

Arias<br />

Idomeneo, K366 (1781) – Quando avran fine omai … Padre, germani, addio!<br />

Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio, K418 (1783)<br />

Ah! se in ciel, benigne stelle, K538 (1788)<br />

Laura Claycomb soprano<br />

Mozart retained a love for the female voice throughout his<br />

life, often transferring his affections for the vocal qualities of<br />

his sopranos and mezzos to affairs of the heart – real or<br />

imaginary. The three Mozart arias we hear tonight were<br />

inspired by two very particular voices. In Idomeneo, his first<br />

great opera seria, the part of Ilia (a Trojan princess,<br />

imprisoned by Idomeneo, the King of Crete, and in love with<br />

Idomeneo’s son, Idamante) was written for Dorothea<br />

Wendling, half of a renowned sisterly singing duo (Elisabeth<br />

Wendling took the role of Elettra in the same work). Mozart<br />

had written other vocal pieces for them but this was the first<br />

opportunity to write at length. The recitative and aria,<br />

‘Quando avran fine omai … Padre, gemani, addio!’, is<br />

dramatically positioned straight after the fraught overture, so<br />

it’s the very first vocal utterance we hear and it immediately<br />

sets the tone – of the torment Ilia is suffering (and the evident<br />

virtuosity of Dorothea Wendling), in a recitative that concisely<br />

brings us up to speed with the background to the story,<br />

combining storytelling with high emotion, the music echoing<br />

the twists and turns as hate and love are portrayed. The<br />

anxiety of the recitative turns to sad resolution in the aria, as<br />

Ilia faces up to that eternal conflict (just think of Dido and<br />

Aeneas), between heart and head, love for an individual and<br />

loyalty to one’s family. It’s hardly surprising that Dorothea<br />

pronounced herself very happy with the role.<br />

programme note<br />

The voice behind the aria ‘Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio!’ was that<br />

of Aloysia Weber, with whose family Mozart had lodged in<br />

1778 and to whom he had declared his love. Unfortunately it<br />

was not reciprocated (she married the painter and actor<br />

Joseph Lange in 1780, while Mozart subsequently married<br />

her younger sister, Constanze). The aria was one of two he<br />

wrote for Aloysia for a revival of the deservedly forgotten<br />

opera Il curioso indiscreto (which translates roughly as ‘The<br />

nosy parker’), by Pasquale Anfossi. By all accounts, the revival<br />

was a flop with the exception of Mozart’s contributions. He<br />

audibly plays to Aloysia’s strengths: a brilliant upper register,<br />

delicacy of ornamentation and the ability to sustain a musical<br />

line, all qualities that contribute to the characterisation of<br />

Clorinda who, denying her love for the Count, implores him<br />

to return to Emilia – her rival for his affections.<br />

Laura Claycomb’s final vocal offering this evening, ‘Ah! se in<br />

ciel, benigne stelle’, was also originally intended for Aloysia<br />

Lange (née Weber) and sets words by the Italian poet and<br />

librettist Metastasio (1698–1782), whose texts Mozart drew on<br />

throughout his life. The extended nature of the aria – the tone<br />

set by a far from inconsequential orchestral tutti – and its<br />

stratospheric and agile vocal writing, coupled with its<br />

heartwrending sentiments, once again bear testimony to<br />

Aloysia’s prodigious talents, and must surely have brought<br />

the house down when she premiered it in1788.<br />

Programme note © Sharona Volcano<br />

7

text and translation<br />

Quando avran fine omai … Padre, germani, addio!<br />

Recitative<br />

Quando avran fine omai l’aspre sventure mie?<br />

Ilia infelice! Di tempesta crudel misero avanzo,<br />

del genitor e de’ germani priva,<br />

del barbaro nemico misto col sangue<br />

il sangue vittime generose,<br />

a qual sorte più rea ti riserbano i Numi? …<br />

Pur vendicaste voi di Priamo<br />

e di Troia i danni e l’onte?<br />

Perì la flotta Argiva,<br />

e Idomeneo pasto forse sarà d’orca vorace …<br />

ma che mi giova, oh ciel!<br />

se al primo aspetto di quel prode Idamante,<br />

che all’onde mi rapì, l’odio deposi,<br />

e pria fu schiavo il cor,<br />

che m’accorgessi d’essere prigioniera.<br />

Ah qual contrasto, oh Dio!<br />

d’opposti affetti mi destate nel sen odio, ed amore!<br />

Vendetta deggio a chi mi dié la vita,<br />

gratitudine a chi vita mi rende …<br />

oh Ilia! oh genitor! oh prence! oh sorte!<br />

oh vita sventurata! oh dolce morte!<br />

Ma che? m’ama Idamante? …<br />

ah no; l’ingrato per Elettra sospira,<br />

e quell’Elettra meschina principessa, esule d’Argo,<br />

d’Oreste alle sciagure a queste arene fuggitiva,<br />

raminga, è mia rivale.<br />

Quanti mi siete intorno carnefici spietati? …<br />

orsù sbranate vendetta, gelosia, odio,<br />

ed amore sbranate sì quest’infelice core!<br />

Aria<br />

Padre, germani, addio!<br />

Voi foste, io vi perdei.<br />

Grecia, cagion tu sei.<br />

E un greco adorerò?<br />

8<br />

When will my bitter misfortunes be ended?<br />

Unhappy Ilia, wretched survivor of a dreadful tempest,<br />

bereft of father and brothers,<br />

the victims’ blood spilt and mingled<br />

with the blood of their savage foes,<br />

for what harsher fate have the gods preserved you?<br />

Are the loss and shame<br />

of Priam and Troy avenged?<br />

The Greek fleet is destroyed<br />

and Idomeneo perhaps will be a meal for hungry fish …<br />

But what comfort is that to me, ye heavens,<br />

if at the first sight of that valiant Idamante,<br />

who snatched me from the waves, I forgot my hatred,<br />

and my heart was enslaved<br />

before I realised I was a prisoner.<br />

O God, what a conflict of warring emotions<br />

you rouse in my breast, hate and love!<br />

I owe vengeance to him who gave me life,<br />

gratitude to him who restored it …<br />

O Ilia! O father, O prince, O destiny!<br />

O ill-fated life, O sweet death!<br />

But yet does Idamante love me?<br />

Ah no; ungratefully he sighs for Electra;<br />

and that Electra, unhappy princess, an exile from Argos<br />

and the torments of Oresetes, who fled,<br />

a wanderer, to these shores, is my rival.<br />

Ruthless butchers, how many of you surround me? …<br />

Then up and shatter, vengeance,<br />

jealousy, hate and love; yes, shatter my unhappy heart!<br />

Father, brothers, farewell!<br />

You are no more; I have lost you.<br />

Greece, you are the cause;<br />

and shall I love a Greek?

D’ingrata al sangue mio<br />

So che la colpa avrei;<br />

Ma quel sembiante, oh Dei!<br />

Odiare ancor non so.<br />

Padre, germani, addio, etc.<br />

Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio!<br />

Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio!<br />

Qual è l’affanno mio;<br />

Ma mi condanna il fato<br />

A piangere e tacer.<br />

Arder non può il mio core<br />

Per chi vorrebbe amore<br />

E fa che cruda io sembri,<br />

Un barbaro dover.<br />

Ah conte, partite, correte,<br />

Fuggite, lontano da me.<br />

La vostra diletta Emilia v’aspetta,<br />

Languir non la fate,<br />

È degna d’amor.<br />

Ah stelle spietate!<br />

Nemiche mi siete.<br />

Mi perdo s’ei resta, oh Dio, Mi perdo.<br />

Ah, conte, partite …<br />

Partite, correte, d’amor non parlate,<br />

È vostro il suo cor.<br />

Ah se in ciel, benigne stelle<br />

Ah se in ciel, benigne stelle,<br />

La pietà non è smarrita,<br />

O toglietemi la vita,<br />

O lasciatemi il mio ben.<br />

Voi, che ardete ognor sì belle<br />

Del mio ben nel dolce aspetto,<br />

Proteggete il puro affetto<br />

Che inspirate a questo sen.<br />

I know that I am guilty<br />

of abandoning my kin;<br />

but I cannot bring myself,<br />

O gods, to hate that face.<br />

Father, brothers, farewell, etc.<br />

I would like to explain to you, oh God,<br />

how great is my anguish!<br />

Fate, however, condemns me<br />

to weep and keep silent.<br />

My heart cannot burn<br />

for him who would desire love<br />

and a pitiless duty<br />

makes me appear cruel.<br />

Alas, Count, part from me, hurry,<br />

flee far from me.<br />

Your beloved Emilia awaits you,<br />

don’t keep her languishing,<br />

she is worthy of love.<br />

Alas, pitiless stars!<br />

You are hostile to me.<br />

I am lost if he remains, oh God! I am lost.<br />

Ah, Count, part from me.<br />

Part from me, hurry, do not talk of love,<br />

her heart is yours.<br />

Ah, kind stars, if Heaven<br />

has not abandoned mercy,<br />

then take my life from me,<br />

or let me keep my beloved.<br />

You, who always shine so brightly<br />

on my darling’s sweet face,<br />

protect the pure affection<br />

which you inspire in that heart.<br />

text and translation<br />

9

Pascal Gély<br />

about the performers<br />

About tonight’s performers<br />

Jonathan Cohen conductor<br />

Jonathan Cohen was born in<br />

Manchester in 1977. In demand as a<br />

cellist, conductor and keyboard player,<br />

his repertoire ranges from the Baroque<br />

to contemporary music.<br />

He began his solo career as a cellist,<br />

performing with the Orchestra of the<br />

Age of Enlightenment, Philharmonia<br />

Orchestra, Scottish Chamber<br />

Orchestra and The King’s Consort,<br />

and today he continues to give<br />

concerts as a cellist with the London<br />

Haydn Quartet.<br />

In recent years Jonathan Cohen has<br />

turned increasingly to conducting,<br />

studying with Nicholas Kraemer and<br />

Vladimir Jurowski and specialising in<br />

the Baroque and Classical repertoires.<br />

Building on his experience of early<br />

music (which goes back to his student<br />

10<br />

Laurence Mullenders<br />

years in Cambridge), he conducted 10<br />

performances of The Fairy Queen at<br />

the Théâtre d’Aix-la-Chapelle in 2006.<br />

He regularly assists William Christie<br />

(Idomeneo, The Creation, Rameau’s<br />

<strong>Les</strong> Paladins and Handel’s L’Allegro, il<br />

Penseroso ed il Moderato) and since<br />

2008 he has shared the conducting of<br />

several productions with him, notably<br />

Hérold’s Zampa and Purcell’s The<br />

Fairy Queen. He is also in regular<br />

demand as assistant conductor to<br />

Emmanuelle Haïm.<br />

This season Jonathan Cohen conducts<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> in Dido and<br />

Aeneas, Actéon and The Fairy Queen<br />

in Amsterdam, Paris and New York.<br />

Laura Claycomb soprano<br />

Native Texan Laura Claycomb, known<br />

for her delicacy, refinement and<br />

theatricality in high-flying repertoire, is<br />

one of the world’s foremost lyric<br />

coloraturas. Following concurrent<br />

degrees in Music and Foreign<br />

Languages at Southern Methodist<br />

University and a subsequent<br />

apprenticeship with San Francisco<br />

Opera, she made her European debut<br />

as Giulietta (I Capuleti e I Montecchi) in<br />

Geneva, reprising it in Paris, Los<br />

Angeles and Munich. She has<br />

subsequently garnered acclaim as<br />

Gilda (Rigoletto) in Houston, Toronto,<br />

Paris, Lausanne, Tel Aviv, Santiago de<br />

Chile and Bilbao; Cleopatra (Giulio<br />

Cesare) in Houston, Drottningholm<br />

and Montpellier; and the title-roles of<br />

Lucia di Lammermoor in Houston, Tel<br />

Aviv, Seoul and Moscow, and La Fille<br />

du Régiment in San Francisco, Turin,<br />

Houston and Rome. Other signature<br />

roles include Linda di Chamounix,<br />

Zerbinetta (Ariadne auf Naxos), Anne<br />

Trulove (The Rake’s Progress), Amanda<br />

(Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre),<br />

Morgana (Alcina), Adèle (Le comte<br />

Ory), Ophélie (Thomas’s Hamlet) and<br />

the creation of Queen Wealtheow in<br />

Elliot Goldenthal’s Grendel.<br />

She also regularly performs in concert<br />

with leading conductors and<br />

orchestras.

Fourth Symphony with Michael Tilson<br />

Thomas and the San Francisco<br />

Symphony, Le Grand Macabre under<br />

Esa-Pekka Salonen, a disc of Handel<br />

duets directed by Emmanuelle Haïm,<br />

Vaughan Williams’s Sir John in Love<br />

with Richard Hickox, two recordings<br />

of Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini, under<br />

Sir Roger Norrington and Sir Colin<br />

Davis, and recordings of lesser-known<br />

operas by Meyerbeer, Balfe, Pacini<br />

and Thomas.<br />

Marco Borggreve Her recordings include Mahler’s<br />

Kristian Bezuidenhout fortepiano<br />

Kristian Bezuidenhout was born in<br />

South Africa in 1979 and his teachers<br />

included Malcolm Bilson, Paul O’Dette<br />

and Robert Levin. He won First Prize<br />

and the Audience Prize in the 2001<br />

Bruges Fortepiano Competition.<br />

He regularly performs on fortepiano,<br />

harpsichord and modern piano in<br />

North America, Europe, Australia and<br />

Asia. Among the festivals at which he<br />

has appeared are those of Barcelona,<br />

Boston, Bruges, Esterhaza, Utrecht, St<br />

Petersburg, Vermont, Venice and West<br />

Cork. He is currently professor of the<br />

Eastman School of Music and in Basle.<br />

His recordings include solo fortepiano<br />

works and violin sonatas by Mozart,<br />

Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, and<br />

Bach concertos with Daniel Hope.<br />

Highlights of last season include a tour<br />

with Frans Brüggen and the Orchestra<br />

of the 18th Century, performing<br />

Mozart’s late piano concertos. This<br />

season he plays concertos with the<br />

Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, goes on<br />

tour with the Royal Concertgebouw<br />

Orchestra, conducted by Ton<br />

Koopman, performs and records<br />

Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Mark<br />

Padmore and takes part in the 2010<br />

Holland Festival, where he will be<br />

playing from Bach’s 48.<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong><br />

about the performers<br />

The renowned vocal and instrumental<br />

ensemble <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> was<br />

founded in 1979 by William Christie,<br />

and takes its name from an opera by<br />

Marc-Antoine Charpentier.<br />

Since the acclaimed production of Atys<br />

by Lully at the Opéra Comique in Paris<br />

in 1987, it has been in the field of opera<br />

where <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> has found<br />

most success. Notable productions<br />

include works by Rameau (<strong>Les</strong> Indes<br />

galantes in 1990 and 1999, Hippolyte<br />

et Aricie in 1996, <strong>Les</strong> Boréades in 2003,<br />

<strong>Les</strong> Paladins in 2004), Charpentier<br />

(Médée in 1993 and 1994), Handel<br />

(Orlando in 1993, Acis and Galatea in<br />

1996, Semele in 1996, Alcina in 1999,<br />

Hercules in 2004 and 2006), Purcell<br />

(King Arthur in 1995, Dido and Aeneas<br />

in 2006), Mozart (The Magic Flute in<br />

1994, Die Entführung aus dem Serail at<br />

the Opéra du Rhin in 1995) and<br />

Monteverdi (Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria<br />

at Aix-en-Provence in 2000, revived in<br />

2002, L’incoronazione di Poppaea in<br />

2005, and L’Orfeo at the Teatro Real<br />

de Madrid in 2008).<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> has an equally high<br />

profile in the concert hall, giving<br />

concert performances of operas<br />

(Zoroastre and <strong>Les</strong> fêtes d’Hébé by<br />

11

about the performers & player list<br />

Rameau, Idomenée by Campra,<br />

Jephté by Montéclair and L’Orfeo by<br />

Rossi), as well as secular chamber<br />

works (Actéon, <strong>Les</strong> plaisirs de<br />

Versailles and La descente d’Orphée<br />

aux Enfers by Charpentier and Dido<br />

and Aeneas by Purcell) and sacred<br />

music (grands motets by Rameau,<br />

Mondonville and Desmarest) and<br />

Handel oratorios.<br />

The ensemble has an impressive<br />

discography of over 70 CD recordings,<br />

most recently Haydn’s The Creation. Its<br />

most recent DVD is Il Sant’Alessio by<br />

Stefano Landi, filmed at the Théâtre de<br />

Caen, where, for the past 15 years, the<br />

ensemble has been artist-in-residence.<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> also tours widely<br />

within France, and is a frequent<br />

ambassador for French culture<br />

abroad, regularly appearing at the<br />

Brooklyn Academy, the Lincoln Center<br />

in New York, the <strong>Barbican</strong> Centre and<br />

the Vienna Festival.<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> receive financial<br />

support from the Ministry of Culture and<br />

Communication, the City of Caen and the<br />

Région Basse-Normandie. Their sponsor is<br />

Imerys. <strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong> are artists in<br />

residence at the Théâtre de Caen.<br />

12<br />

<strong>Les</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>Florissants</strong><br />

Musical Director<br />

William Christie<br />

Executive Manager<br />

Luc Bouniol-Laffont<br />

Tonight’s Conductor<br />

Jonathan Cohen<br />

Orchestra<br />

Violin I<br />

Nadja Zwiener leader<br />

Bernadette Charbonnier<br />

Martha Moore<br />

Benjamin Scherer<br />

Satomi Watanabe<br />

Violin II<br />

Catherine Girard<br />

Sophie Gevers-Demoures<br />

Michèle Sauvé<br />

George Willms<br />

Viola<br />

Galina Zinchenko<br />

Lucia Peralta<br />

Jean-Luc Thonnerieux<br />

Cello<br />

David Simpson<br />

Damien Launay<br />

Alix Verzier<br />

Double Bass<br />

Jonathan Cable<br />

Joseph Carver<br />

Flute<br />

Charles Zebley<br />

Serge Saitta<br />

Oboe<br />

Pier Luigi Fabretti<br />

Michel Henry<br />

Bassoon<br />

Claude Wassmer<br />

Philippe Piat<br />

Horn<br />

Helen MacDougall<br />

Benjamin Locher