SourCeBook oN remoTe SeNSiNg aND BioDiverSiTy iNDiCaTorS

SourCeBook oN remoTe SeNSiNg aND BioDiverSiTy iNDiCaTorS

SourCeBook oN remoTe SeNSiNg aND BioDiverSiTy iNDiCaTorS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

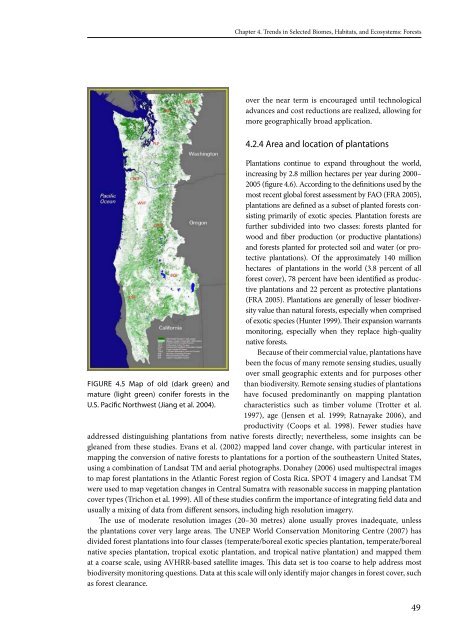

FIguRe 4.5 Map of old (dark green) and<br />

mature (light green) conifer forests in the<br />

u.S. Pacific Northwest (Jiang et al. 2004).<br />

Chapter 4. Trends in Selected Biomes, Habitats, and Ecosystems: Forests<br />

over the near term is encouraged until technological<br />

advances and cost reductions are realized, allowing for<br />

more geographically broad application.<br />

4.2.4 Area and location of plantations<br />

Plantations continue to expand throughout the world,<br />

increasing by .8 million hectares per year during 000–<br />

005 (figure 4.6). According to the definitions used by the<br />

most recent global forest assessment by FAO (FRA 005),<br />

plantations are defined as a subset of planted forests consisting<br />

primarily of exotic species. Plantation forests are<br />

further subdivided into two classes: forests planted for<br />

wood and fiber production (or productive plantations)<br />

and forests planted for protected soil and water (or protective<br />

plantations). Of the approximately 140 million<br />

hectares of plantations in the world (3.8 percent of all<br />

forest cover), 78 percent have been identified as productive<br />

plantations and percent as protective plantations<br />

(FRA 005). Plantations are generally of lesser biodiversity<br />

value than natural forests, especially when comprised<br />

of exotic species (Hunter 1999). Their expansion warrants<br />

monitoring, especially when they replace high-quality<br />

native forests.<br />

Because of their commercial value, plantations have<br />

been the focus of many remote sensing studies, usually<br />

over small geographic extents and for purposes other<br />

than biodiversity. Remote sensing studies of plantations<br />

have focused predominantly on mapping plantation<br />

characteristics such as timber volume (Trotter et al.<br />

1997), age (Jensen et al. 1999; Ratnayake 006), and<br />

productivity (Coops et al. 1998). Fewer studies have<br />

addressed distinguishing plantations from native forests directly; nevertheless, some insights can be<br />

gleaned from these studies. Evans et al. ( 00 ) mapped land cover change, with particular interest in<br />

mapping the conversion of native forests to plantations for a portion of the southeastern United States,<br />

using a combination of Landsat TM and aerial photographs. Donahey ( 006) used multispectral images<br />

to map forest plantations in the Atlantic Forest region of Costa Rica. SPOT 4 imagery and Landsat TM<br />

were used to map vegetation changes in Central Sumatra with reasonable success in mapping plantation<br />

cover types (Trichon et al. 1999). All of these studies confirm the importance of integrating field data and<br />

usually a mixing of data from different sensors, including high resolution imagery.<br />

The use of moderate resolution images ( 0–30 metres) alone usually proves inadequate, unless<br />

the plantations cover very large areas. The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre ( 007) has<br />

divided forest plantations into four classes (temperate/boreal exotic species plantation, temperate/boreal<br />

native species plantation, tropical exotic plantation, and tropical native plantation) and mapped them<br />

at a coarse scale, using AVHRR-based satellite images. This data set is too coarse to help address most<br />

biodiversity monitoring questions. Data at this scale will only identify major changes in forest cover, such<br />

as forest clearance.<br />

49