CalMagSpr05 ind.indd - CSUSB Magazine - California State ...

CalMagSpr05 ind.indd - CSUSB Magazine - California State ...

CalMagSpr05 ind.indd - CSUSB Magazine - California State ...

- TAGS

- csusb

- magazine.csusb.edu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

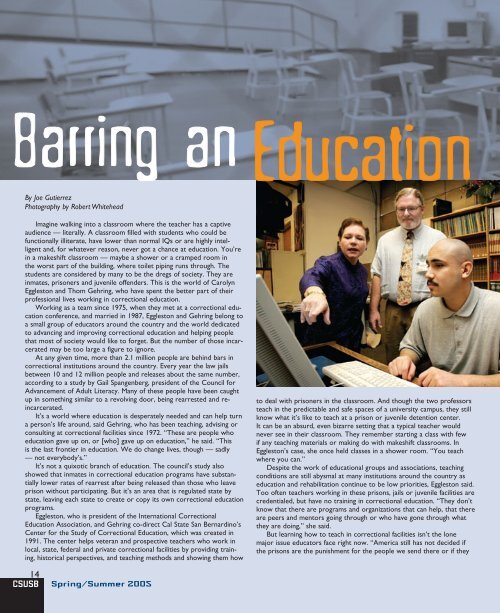

By Joe Gutierrez<br />

Photography by Robert Whitehead<br />

Imagine walking into a classroom where the teacher has a captive<br />

audience — literally. A classroom filled with students who could be<br />

functionally illiterate, have lower than normal IQs or are highly intelligent<br />

and, for whatever reason, never got a chance at education. You’re<br />

in a makeshift classroom — maybe a shower or a cramped room in<br />

the worst part of the building, where toilet piping runs through. The<br />

students are considered by many to be the dregs of society. They are<br />

inmates, prisoners and juvenile offenders. This is the world of Carolyn<br />

Eggleston and Thom Gehring, who have spent the better part of their<br />

professional lives working in correctional education.<br />

Working as a team since 1975, when they met at a correctional education<br />

conference, and married in 1987, Eggleston and Gehring belong to<br />

a small group of educators around the country and the world dedicated<br />

to advancing and improving correctional education and helping people<br />

that most of society would like to forget. But the number of those incarcerated<br />

may be too large a figure to ignore.<br />

At any given time, more than 2.1 million people are beh<strong>ind</strong> bars in<br />

correctional institutions around the country. Every year the law jails<br />

between 10 and 12 million people and releases about the same number,<br />

according to a study by Gail Spangenberg, president of the Council for<br />

Advancement of Adult Literacy. Many of these people have been caught<br />

up in something similar to a revolving door, being rearrested and reincarcerated.<br />

It’s a world where education is desperately needed and can help turn<br />

a person’s life around, said Gehring, who has been teaching, advising or<br />

consulting at correctional facilities since 1972. “These are people who<br />

education gave up on, or [who] gave up on education,” he said. “This<br />

is the last frontier in education. We do change lives, though — sadly<br />

— not everybody’s.”<br />

It’s not a quixotic branch of education. The council’s study also<br />

showed that inmates in correctional education programs have substantially<br />

lower rates of rearrest after being released than those who leave<br />

prison without participating. But it’s an area that is regulated state by<br />

state, leaving each state to create or copy its own correctional education<br />

programs.<br />

Eggleston, who is president of the International Correctional<br />

Education Association, and Gehring co-direct Cal <strong>State</strong> San Bernardino’s<br />

Center for the Study of Correctional Education, which was created in<br />

1991. The center helps veteran and prospective teachers who work in<br />

local, state, federal and private correctional facilities by providing training,<br />

historical perspectives, and teaching methods and showing them how<br />

14<br />

<strong>CSUSB</strong> Spring/Summer 2005<br />

to deal with prisoners in the classroom. And though the two professors<br />

teach in the predictable and safe spaces of a university campus, they still<br />

know what it’s like to teach at a prison or juvenile detention center.<br />

It can be an absurd, even bizarre setting that a typical teacher would<br />

never see in their classroom. They remember starting a class with few<br />

if any teaching materials or making do with makeshift classrooms. In<br />

Eggleston’s case, she once held classes in a shower room. “You teach<br />

where you can.”<br />

Despite the work of educational groups and associations, teaching<br />

conditions are still abysmal at many institutions around the country as<br />

education and rehabilitation continue to be low priorities, Eggleston said.<br />

Too often teachers working in these prisons, jails or juvenile facilities are<br />

credentialed, but have no training in correctional education. “They don’t<br />

know that there are programs and organizations that can help, that there<br />

are peers and mentors going through or who have gone through what<br />

they are doing,” she said.<br />

But learning how to teach in correctional facilities isn’t the lone<br />

major issue educators face right now. “America still has not decided if<br />

the prisons are the punishment for the people we send there or if they