Rural, Local Economic, and SME Cluster Development

Rural, Local Economic, and SME Cluster Development

Rural, Local Economic, and SME Cluster Development

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DRAFT

Proceedings<br />

<strong>Rural</strong>, <strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

2 nd Workshop <strong>and</strong> Meeting 2011<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> Research <strong>and</strong> Planning Group (RRPG)<br />

DRAFT

Page | ii<br />

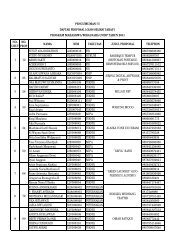

Workshop Proceedings of "<strong>Rural</strong> Research & Planning Group (RRPG) 2 nd Workshop<br />

And Meeting 2011 - <strong>Rural</strong>, <strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>, And <strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong>" was<br />

prepared by Centre for Participatory <strong>Development</strong> Planning Services – P5, Diponegoro<br />

University, in September 2011.<br />

Editor :<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

Editor Team :<br />

Iwan Rudiarto, Wiw<strong>and</strong>ari H<strong>and</strong>ayani<br />

Text <strong>and</strong> Design :<br />

Hasanatun Nisa Thamrin, Dwi Feri Yatnanto, Rizqa Hidayani<br />

Cover photo :<br />

Left picture : P5 Undip observation, <strong>SME</strong> in Kebumen Regency, Central Java Province<br />

Right picture : P5 Undip observation, one of rural area in Central Java Province<br />

Published by :<br />

Center for Participatory <strong>Development</strong> Planning Services<br />

(P5 UNDIP)<br />

Faculty of Engineering - Diponegoro University<br />

Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Building B, Second Floor, Room B-203 UNDIP Tembalang<br />

Semarang 50275 – Indonesia<br />

Tel / Fax: +62 24 7648 0583<br />

Email: p5_undip@yahoo.com<br />

Website: www.p5undip.org<br />

DRAFT<br />

Pusat Pelayanan Perencanaan Pembangunan Partisipatif<br />

(P5) UNDIP<br />

Semarang 2011 ISBN 978-602-99749-5-9

FOREWORD<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

Editor & Workshop Committee<br />

Dear distinguish readers <strong>and</strong> workshop<br />

participants, first of all let me introduce<br />

you to the substance of the 2 nd Meeting<br />

of RRPG 2011: International Workshop of<br />

“<strong>Rural</strong>, <strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong><br />

<strong>Development</strong>”. The workshop was held on<br />

September 19-20, 2011 that arranged by<br />

Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Planning, Diponegoro University in<br />

Semarang, Indonesia. It is also supported<br />

by Province Government of Central Java,<br />

Magister Program of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

<strong>Development</strong> <strong>and</strong> Center for Participatory<br />

Planning – P5 Diponegoro University, as<br />

well Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Department <strong>and</strong> Center for Innovative<br />

Planning <strong>Development</strong> of Universiti<br />

Teknologi Malaysia - UTM.<br />

The 2 nd Meeting of RRPG 2011 is a<br />

continuation program after the 1 st RRPG<br />

Meeting on October 2010 at UTM,<br />

Malaysia that toke the topic of “OVOP?”.<br />

RRPG or <strong>Rural</strong> Research <strong>and</strong> Planning<br />

Group is an open networking group that<br />

based on volunteerism, trust, <strong>and</strong> same<br />

interest to the research <strong>and</strong> planning of<br />

the rural area. We share our experience,<br />

knowledge, <strong>and</strong> idea that make better<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of rural challenge <strong>and</strong><br />

collaborate how to deal with it.<br />

The 2 nd RRPG meeting is followed by 31<br />

participants. They are from 6 countries<br />

citizenships mostly from Indonesia, 12<br />

universities, 3 CSO, 3 International NGO,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 4 government bodies. Now, with the<br />

global era where the activities are<br />

borderless, where the communication <strong>and</strong><br />

interaction are very easy, then a strong<br />

networking becomes an important asset<br />

to improve our quality of live.<br />

The workshop topic of rural, local<br />

economic, <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster development<br />

relates to RRPG substances concern on, as<br />

well regards to the recent substance<br />

challenge in Indonesia. The proceedings<br />

provides you with the substances of the<br />

workshop that divide the topics become<br />

four main categorizes. The first chapter it<br />

gives you the international perspective of<br />

rural <strong>and</strong> local economic development<br />

from 4 different countries. The second<br />

chapter discusses about the government<br />

policy <strong>and</strong> practices of local economic<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster development in<br />

Indonesia, both in National level <strong>and</strong><br />

provincial/local level. The third section<br />

presents the interesting cases in Indonesia<br />

<strong>and</strong> Malaysia. While the last section<br />

presents the specific substances cases i.e.<br />

tourism, social economic aspects, social<br />

capital, spatial perspective, etc.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Last but not least we would thanks to all<br />

partners who make the 2 nd meeting RRPG<br />

can be happen. Thus, we would like to<br />

take this opportunity to express our<br />

gratitude to all those who have<br />

contributed to this work. Especially, we<br />

would like to thank to Dr. rer.nat. Imam<br />

Buchori as head of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Planning Department, <strong>and</strong> Dr. Joesron<br />

Alie Syahbana as head of Master Program<br />

of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional <strong>Development</strong> who<br />

Page | iii

facilitated <strong>and</strong> support for all institutional<br />

requirements. We would like also to<br />

appreciate Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Ngah<br />

as head of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Department, <strong>and</strong> Prof. Dr. Amran as Head<br />

of Center for Innovative Planning<br />

<strong>Development</strong> that give many support to<br />

connect the RRPG networks, as well many<br />

thanks to our senior colleagues Prof.<br />

David Preston one of RRPG founder that<br />

give many ideas <strong>and</strong> inputs for the<br />

workshop contents.<br />

As well, we would like to thanks to Center<br />

for Participatory Planning – P5<br />

Diponegoro University for its facilitation<br />

Workshop Secretariat, <strong>and</strong> great thanks to<br />

the committee team i.e. Dr. sc. agr. Iwan<br />

Rudiarto, Wiw<strong>and</strong>ari H<strong>and</strong>ayani, Msc,<br />

Artiningsih, MSi, Rizqa Hidayani, ST., Dwi<br />

Feri Yatnanto, ST, Hassanatun Nisa<br />

Thamrin, ST., <strong>and</strong> all committee team for<br />

Page | iv<br />

their great efforts to make this second<br />

RRPG meeting happen. We also would<br />

like to thanks to FPESD Central Java<br />

Province, BAPPEDA Kabupaten Magelang,<br />

as well Bapak Kirno <strong>and</strong> all colleagues<br />

from FRK Borobudur for the field visit<br />

support in Borobudur area.<br />

Finally we also to give high gratitudes to<br />

all partners <strong>and</strong> participants for their<br />

support to the workshop. Hope you will<br />

enjoy the discussion of substances, <strong>and</strong><br />

have benefits from it.<br />

Thank you.<br />

Editor & Workshop committee,<br />

DRAFT<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya

FOREWORD<br />

Dr.rer.nat. Imam Buchori<br />

Head of Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Faculty of Engineering, Diponegoro University<br />

Your Excellency, Rector of Diponegoro<br />

University<br />

Your Excellency, Dean of Faculty of<br />

Engineering, Diponegoro University<br />

Distinguished Professors <strong>and</strong> Colleagues<br />

Ladies <strong>and</strong> Gentlemen<br />

Assalammualaikum warahmatullahi<br />

wabarakatuh<br />

First of all, let’s thanks to God that today<br />

we can meet in this room in order to<br />

attend the International Workshop on<br />

“<strong>Rural</strong>, <strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong><br />

<strong>Development</strong>”. We all know that without<br />

His blessing we cannot have this useful<br />

meeting.<br />

This workshop is the second Workshop<br />

<strong>and</strong> Meeting of <strong>Rural</strong> Research <strong>and</strong><br />

Planning Group (RRPG), following the first<br />

workshop conducted in Universiti<br />

Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) last year. We<br />

consider this event as an international<br />

workshop because it is attended by<br />

participants coming from six countries, i.e.<br />

Malaysia, Japan, UK, Germany, USA, <strong>and</strong><br />

Indonesia. About 15 papers will be<br />

presented there. This event is also<br />

adjusted as one of “dies natalis” or “the<br />

day of birth” activities of Diponegoro<br />

University (UNDIP).<br />

The RRPG was firstly initiated by UTM <strong>and</strong><br />

UNDIP in a meeting two years ago as a<br />

realization of Memor<strong>and</strong>um of Action<br />

(MoA) between the Head of Department<br />

of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning of UTM<br />

<strong>and</strong> that of UNDIP. The meeting decided<br />

to conduct an international workshop on<br />

“One Village One Product” by inviting<br />

participants from several countries, which<br />

in turn was considered as the first<br />

International Workshop <strong>and</strong> Meeting of<br />

RRGP.<br />

In this opportunity, I would like to express<br />

my gratitude to the works of the<br />

workshop committee, especially Mr. Holi<br />

Bina Wijaya, who has been hardly working<br />

in preparing everything to the success of<br />

this workshop. Special thanks to Professor<br />

Ibrahim Ngah from UTM as the founder of<br />

RRGP for his support to this event.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Finally, thank you for your attention <strong>and</strong><br />

wassalammualaikum warahmatullahi<br />

wabarakatuh.<br />

Head of Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Faculty of Engineering, Diponegoro University.<br />

Dr.rer.nat. Imam Buchori<br />

Page | v

FOREWORD<br />

Associate Professor Dr Ibrahim Ngah<br />

RRPG Representatif<br />

The RRPG would like to welcome all<br />

participants to the second workshop <strong>and</strong><br />

field study in Semarang. To cater for<br />

more diverse interests, we have chosen<br />

broader theme for this workshop: “<strong>Rural</strong>,<br />

<strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong><br />

<strong>Development</strong>”. We are glad to have more<br />

participants this year including those who<br />

have attended the first workshop last year<br />

in Malaysia <strong>and</strong> the new members from<br />

Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam <strong>and</strong> United<br />

Kingdom <strong>and</strong> other countries. RRPG aims<br />

to become an international platform for<br />

meeting <strong>and</strong> networking among those<br />

specialists/experts <strong>and</strong> practitioners in the<br />

field of rural development <strong>and</strong> planning.<br />

This includes exchange of knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

experiences, discussion on research<br />

findings <strong>and</strong> ideas, plan <strong>and</strong> organize<br />

activities for mutual benefit.<br />

The idea of forming RRPG came from a<br />

meeting in May 2010, together with<br />

Professor David Preston from Oxford, Pak<br />

Imam Buchori <strong>and</strong> Pak Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

from Universitas Diponegoro (UNDIP), Dr<br />

Suriati from Universiti Sains Malaysia<br />

(USM) <strong>and</strong> colleagues in Universiti<br />

Teknologi Malaysia (UTM). The first<br />

meeting <strong>and</strong> field study was held in UTM<br />

on October 4-5, 2010 attended by<br />

scholars from Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia<br />

<strong>and</strong> Bangladesh. The theme of the last<br />

year meeting was One Village One<br />

Product (OVOP) <strong>and</strong> we gained a good<br />

exposure on various experiences in the<br />

implementation of OVOP in a few<br />

countries in Asia <strong>and</strong> other related topics.<br />

We are glad that some members<br />

managed to maintain networking <strong>and</strong><br />

organized a few activities such as students<br />

exchange programs between UTM <strong>and</strong><br />

UNDIP including students’ visits, summer<br />

school <strong>and</strong> research collaboration.<br />

In this year meeting perhaps we can look<br />

further into possibility of research<br />

collaboration <strong>and</strong> writing of book<br />

chapters on topics which are of common<br />

interest or “cross border”. An example of<br />

the “cross border“ research topic is<br />

international migration which could be<br />

carried out collaboratively among<br />

researchers from the migrants place of<br />

origins <strong>and</strong> destinations.<br />

DRAFT<br />

On behalves of RRPG I would like to<br />

thanks UNDIP <strong>and</strong> members of organizing<br />

committee for hosting the meeting <strong>and</strong><br />

making excellent arrangement to enable<br />

this program successful. To exp<strong>and</strong> our<br />

networking all new participants will be<br />

added to the list of RRPG members. We<br />

would like to welcome <strong>and</strong> thanks all the<br />

participants for giving support to the<br />

success of RRPG.<br />

RRPG Representative,<br />

Associate Professor Dr Ibrahim Ngah<br />

Page | vii

TABLE OF CONTENT<br />

Foreword<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya. Workshop Committee iii<br />

Dr.rer.nat. Imam Buchori<br />

Head of Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Planning v<br />

Associate Professor Dr Ibrahim Ngah<br />

RRPG Representatif vii<br />

Table of Content viii<br />

Contributors x<br />

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1<br />

Introduction<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya 3<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

CURRENT EXPERIENCES AND<br />

RESULTING ISSUES 7<br />

Helping <strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Benefit<br />

<strong>Local</strong> And Regional Societies And<br />

Economies<br />

Prof. Dr. David Preston<br />

University of Oxford. United Kingdom 9<br />

The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm<br />

Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

Prof. Kunio Igusa.<br />

Asia Pacific University. Japan 13<br />

Challenges in <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Economic</strong><br />

Transformation in Malaysia<br />

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Ngah<br />

UTM. Malaysia 41<br />

The Other Side of <strong>Local</strong> Supporting<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> of <strong>Rural</strong> Areas in Java<br />

Dr. Joesron Alie Syahbana<br />

Page | viii<br />

UNDIP. Indonesia 47<br />

Recalibrating <strong>Cluster</strong> Theory for<br />

Developing Country : Examples from<br />

Indonesia<br />

Prof. Nicholas A Phelps<br />

University College London. United Kingdom 51<br />

CHAPTER 3<br />

LEARNING FROM LOCAL ECONOMIC<br />

AND CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT IN<br />

INDONESIA 69<br />

<strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong><br />

<strong>Development</strong> in Central Java Province<br />

Indonesia<br />

Anung Sugihantono<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> Develepment Forum. FPESD.<br />

Central Java Province. Indonesia 71<br />

<strong>Local</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in Central<br />

Java Province: Current Process.<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

UNDIP Indonesia 75<br />

DRAFT<br />

<strong>Local</strong> Innovative System (SIDa) for<br />

<strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong>.<br />

Agus Suryono<br />

Research <strong>and</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Board. Central<br />

Java Province. Indonesia 85<br />

CHAPTER 4<br />

IMPACT OF LED AND <strong>SME</strong><br />

CLUSTERING 97<br />

Salt Fish <strong>and</strong> Brown Sugar Maker, make<br />

Pang<strong>and</strong>aran Tourism Resort Alive?<br />

Dr. Uton Rustan <strong>and</strong> Ira Savitri<br />

B<strong>and</strong>ung Islamic University. Indonesia 99<br />

<strong>Development</strong> of Biofarmaka <strong>Cluster</strong><br />

Karanganyar Central Java<br />

Dr. Rustina Untari<br />

Soegijapranata University 113

<strong>Local</strong> Economy <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> <strong>Cluster</strong> in<br />

Seberang Prai, Penang State, Malaysia<br />

Colonius Atang, Sharifah Rohayah Sheikh<br />

Dawood, Suriati Ghazali, Narimah Samat.<br />

Universiti Sain Malaysia-USM. Malaysia 116<br />

CHAPTER 5<br />

KEY ELEMENTS OF CLUSTERING IN<br />

SPESIFIC SITUATIONS 130<br />

Simulating Farm Income in <strong>Rural</strong><br />

Mountain Area: a Spatial Perspective<br />

Dr. sc.agr. Iwan Rudiarto<br />

UNDIP. Indonesia 132<br />

Bonding/Bridging Social Capital: Is it a<br />

Choice or Necessity? A Case Study of<br />

Rebana <strong>Cluster</strong>, Central Java<br />

Sri Utami<br />

Semarang State University. Indonesia 147<br />

The Interplay Between Socioeconomic<br />

Structures <strong>and</strong> Actors in Industrial<br />

<strong>Cluster</strong>s: the Case of the Kotagede<br />

Silver H<strong>and</strong>icraft <strong>Cluster</strong> in Yogyakarta,<br />

Indonesia<br />

Poppy Ismalina, PhD<br />

Gajahmada University. Indonesia 160<br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | ix

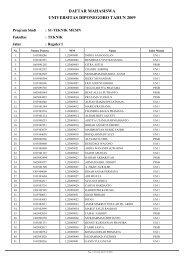

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

1. Professor Dr. David Preston<br />

d.a.preston@leeds.ac.uk<br />

Senior Research Associate, University of<br />

Oxford.<br />

United Kingdom.<br />

2. Professor Kunio Igusa<br />

kigusa@apu.ac.jp<br />

Graduate School of International<br />

Cooperation Policy<br />

College of International Management.<br />

Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University.<br />

Oita. Japan.<br />

3. Associate Professor Dr. Ibrahim Ngah<br />

b-ibrhim@utm.my<br />

Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Planning<br />

Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Skudai<br />

Johor Bahru. Malaysia<br />

4. Dr. Joesron Alie Syahbana, MSc<br />

yoesrona@yahoo.com<br />

Master Program of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

<strong>Development</strong>.<br />

Diponegoro University.<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

5. Professor Nicholas A Phelps<br />

n.phelps@ucl.ac.uk<br />

Bartlett School of Planning. University<br />

College London - UCL<br />

London. United Kingdom<br />

6. Anung Sugihantono<br />

anung_semarang@yahoo.com<br />

Secretary of FPESD (Forum<br />

Pengembangan Ekonomi dan Sumber<br />

Daya)<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>and</strong> Resource <strong>Development</strong><br />

Forum<br />

Jawa Tengah Province<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

7. Drs. Agus Suryono, MM<br />

agssmg@yahoo.com<br />

Chairman<br />

Board of Research <strong>and</strong> <strong>Development</strong> of<br />

Central Java Province<br />

Page | x<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

8. Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

h.wijaya@undip.ac.id<br />

Center for Participatory Planning<br />

Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Department<br />

Diponegoro University.<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

9. Dr. Ir. Uton Rustan Harun, MSc<br />

rustanuton@yahoo.com<br />

B<strong>and</strong>ung Islamic University<br />

Taman Sari 1. B<strong>and</strong>ung<br />

Indonesia.<br />

10. Colonius Atang<br />

collendong@gmail.com<br />

Research Officer<br />

School of Humanities. Universiti Sains<br />

Malaysia. Penang,<br />

Malaysia<br />

11. Poppy Ismalina, PhD.<br />

poppy_ismalina@yahoo.com<br />

Faculty of <strong>Economic</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Business,<br />

UGM<br />

Jogjakarta. Indonesia.<br />

12. Dr. sc.agr. Iwan Rudiarto, MSc<br />

irudiarto@yahoo.com<br />

Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Department.<br />

Diponegoro University.<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

13. Dr. Rustina Untari<br />

r.untari@gmail.com<br />

PUSBANGDAYA / Soegijapranata<br />

Catholic University<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

14. Sri Utami<br />

sriutami2008@gmail.com<br />

Semarang State University<br />

Semarang. Indonesia.<br />

DRAFT

DRAFT

DRAFT<br />

CHAPTER 1<br />

Introduction<br />

Page | 1

Page | 2<br />

DRAFT

INTRODUCTION<br />

Holi Bina Wijaya<br />

Editor<br />

h.wijaya@undip.ac.id<br />

<strong>Local</strong> economic development (LED) has<br />

become an important strategy especially in<br />

developing countries, since it promotes the<br />

use of local resources as a basis for<br />

economic development <strong>and</strong> employment<br />

promotion. The importance of LED mostly is<br />

due to its support for the betterment of<br />

local people through the use of local<br />

resources. It also promotes sustainable<br />

development. Many international agencies,<br />

like United Nations agencies, have adopted<br />

this approach for their programs.<br />

In many countries, local economic<br />

development has become an important<br />

mode of rural development. Traditionally,<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> rural industries are mainly<br />

the economic bases of rural areas. <strong>Rural</strong><br />

people have used their local resources <strong>and</strong><br />

skills to produce the local products. With<br />

these products they fulfill their needs <strong>and</strong><br />

support their life. This activity cycle has<br />

occurred for long time of rural growth.<br />

Until now, many rural development<br />

programs relate to poverty eradication. It is<br />

the challenge how to transform the<br />

development program that is not only to the<br />

poorest people, but also to promote the<br />

advance people’s economic status <strong>and</strong> rural<br />

competitiveness.<br />

The small <strong>and</strong> medium enterprise (<strong>SME</strong>)<br />

cluster links a group of <strong>SME</strong> production<br />

activities in the same area that has<br />

synergistic linkages between them. The idea<br />

of the <strong>SME</strong> cluster mostly focuses on the<br />

value chain of production activity among<br />

<strong>SME</strong>s <strong>and</strong> supporting entities of production,<br />

which encourage the collective efficiency<br />

<strong>and</strong> profit in the cluster. <strong>SME</strong> cluster is one<br />

of the LED approach in the operational<br />

business level.<br />

There are many experiences of the <strong>SME</strong><br />

cluster <strong>and</strong> LED practices. Some are<br />

successful, others not. The name <strong>and</strong><br />

approaches may vary in different contexts<br />

<strong>and</strong> countries, but there are some similarity<br />

of the idea <strong>and</strong> concept. Many components<br />

<strong>and</strong> context become relevant factors for<br />

better achievement. There are relevant<br />

studies <strong>and</strong> experiences to share, in order to<br />

learn how the <strong>SME</strong> cluster, local economic,<br />

<strong>and</strong> rural development work, <strong>and</strong> give<br />

benefits for the people while encourage<br />

sustainability of development.<br />

The workshop is the effort to give some<br />

options to the participants <strong>and</strong> readers to<br />

face with the development of rural <strong>and</strong> local<br />

economic context. It has the purposes i.e.<br />

• Conducting the discussion for<br />

•<br />

knowledge <strong>and</strong> idea sharing of rural<br />

<strong>and</strong> local economic development, as<br />

well <strong>SME</strong> clusters development.<br />

Sharing the experiences of good <strong>and</strong><br />

best practices of rural <strong>and</strong> local<br />

economic development, <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong>s<br />

clusters experiences from different<br />

•<br />

context <strong>and</strong> countries.<br />

Building <strong>and</strong> improving RRPG network<br />

for the development <strong>and</strong> knowledge<br />

sharing at the local, national, <strong>and</strong><br />

international level.<br />

DRAFT<br />

The contributors of this proceedings consist<br />

of the academicians, researchers, <strong>and</strong><br />

practitioners who have experiences <strong>and</strong><br />

competences to the development of rural,<br />

local economic, business clusters of <strong>SME</strong>s at<br />

Page | 3

local, national, or international levels. (see.<br />

Contributors, page-x). The idea <strong>and</strong><br />

information from different background<br />

perspectives will give us better<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the problems <strong>and</strong><br />

solutions.<br />

Regarding to the substance, there are some<br />

initial issues <strong>and</strong> questions that guide the<br />

workshop discussion, as well the readers, to<br />

explore the context, challenges, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

option of solutions of rural, local economic,<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster development challenges i.e.<br />

• The rural development is a significant<br />

part of national or regional<br />

•<br />

development.<br />

Is it true?, why?, how is it happen?<br />

What sort of rural areas do national<br />

governments prioritize compared with<br />

state/regional governments?<br />

The local economic <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> clusters<br />

are important as alternative ways for<br />

country development strategy.<br />

Are they? Where have they been<br />

•<br />

most/least successful?<br />

There are some similarity <strong>and</strong> difference<br />

of practice approaches.<br />

What are they? How is the process?<br />

• There some key elements <strong>and</strong> success<br />

factors to every practice situation.<br />

What are they in specific?<br />

• There are some interesting <strong>and</strong> realistic<br />

future research priorities regarding to<br />

the workshop topics<br />

What are they? What is the opportunity<br />

to carry out the work?<br />

These are open list of questions. Participants<br />

<strong>and</strong> readers could add more relevant issues<br />

<strong>and</strong> questions. The point is how important<br />

<strong>and</strong> realistic the topics to our interest work<br />

<strong>and</strong> life.<br />

The substances of paper follow to the three<br />

main stages. The writings in first part will<br />

provide current experiences <strong>and</strong> resulting<br />

issues from the international context<br />

perspectives, while the second part provides<br />

some main practices in Indonesia. The last<br />

part will present the specific cases <strong>and</strong> ideas<br />

Page | 4<br />

from the experience <strong>and</strong> perspective of<br />

contributors.<br />

In the first part David Preston will initiate the<br />

thought how cluster development benefit<br />

local <strong>and</strong> regional societies <strong>and</strong> economies.<br />

This idea is followed by three experiences<br />

from Japan, Malaysia, <strong>and</strong> Indonesia.. The<br />

popular concept of one village <strong>and</strong> one<br />

product - OVOP <strong>and</strong> its progress will be<br />

presented by Kunio Igusa. It has quiet long<br />

progress for almost 35 years, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

progress of process <strong>and</strong> result has been<br />

documented. Recently, the OVOP concept<br />

also has been adopted by some other<br />

countries. Ibrahim Ngah will present the<br />

rural transformation as a current<br />

development challenge in Malaysia. While<br />

the third case of rural growth issues in<br />

Indonesia will be presented by Joesron Alie<br />

Syahbana. The experiences <strong>and</strong> perspectives<br />

from three Asia countries are expected<br />

could give some general ideas <strong>and</strong> issues of<br />

the region. The last, Nicholas A. Phelps starts<br />

to initiate the idea to recalibrate cluster<br />

theory for developing country<br />

industrialization. He proposes the<br />

differentiation of industrial clusters in three<br />

types, i.e. traditional, transitional, <strong>and</strong><br />

modern. The first part papers will bring us<br />

the opportunity to explore the current<br />

practices from different context in the Asia<br />

region. It gives the reason <strong>and</strong> expected<br />

result of development, as well the<br />

opportunity to improve the underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

<strong>and</strong> concept of cluster development as part<br />

of rural <strong>and</strong> local economic development.<br />

DRAFT<br />

The presentations in second part provide us<br />

with some of the main practices<br />

onformation in Indonesia, especially in<br />

Central Java Province. Central Java Province<br />

is an appropriate model to represent the<br />

local economic <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster<br />

development in Indonesia. About 7 millions<br />

of 40 millions of <strong>SME</strong>s in Indonesia are<br />

located in Central Java. This province has<br />

become a reference of National agencies<br />

<strong>and</strong> other local governments to the local<br />

economic development practices. The

papers in this part provide the experience of<br />

local economic <strong>and</strong> cluster development<br />

National <strong>and</strong> Central Java. The specific<br />

programs of innovation system, regional<br />

economic development also become part of<br />

discussion.<br />

The last part of discussion provides us with<br />

some specific cases. These are relates with<br />

the type of business as regarding local<br />

resources business i.e. tourism, fish<br />

processing, biofarmaka, rebana, silver<br />

h<strong>and</strong>icraft etc. The other aspect is regarding<br />

to the factors those become critical<br />

influence factors <strong>and</strong> result of the local<br />

economy <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster. These things<br />

relate to the participation, socio economic<br />

structure, social capital, location <strong>and</strong> spatial<br />

aspect, <strong>and</strong> some other aspects relates to<br />

the production process.<br />

The thoughts <strong>and</strong> experiences sharing from<br />

the contributors are valuable inputs to bring<br />

us for the better underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the rural,<br />

local economy, <strong>and</strong> <strong>SME</strong> cluster, as well<br />

encourage the new opportunity to find the<br />

options of concept <strong>and</strong> solution for<br />

knowledge improvement <strong>and</strong> better<br />

development result.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 5

Page | 6<br />

DRAFT

DRAFT<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

Experience <strong>and</strong> Resulting<br />

Issues<br />

Page | 7

Page | 8<br />

DRAFT

HELPING CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT BENEFIT LOCAL AND<br />

REGIONAL SOCIETIES AND ECONOMIES<br />

Prof. Dr. David Preston<br />

Senior Research Associate. University of Oxford. United Kingdom<br />

E-mail: d.a.preston@leeds.ac.uk<br />

A common issue relating to cluster<br />

development (OVOP etc.) is the extent to<br />

which it is driven by the community or<br />

communities that make up the cluster.<br />

The World Bank describes communitydriven<br />

development as characteristic of<br />

projects that increase community control<br />

over the development process in a paper<br />

analyzing part of the Indonesian<br />

experience (Dasgupta <strong>and</strong> Beard 2007).<br />

This paper offers valuable insights into<br />

ways in which village development<br />

projects can be managed <strong>and</strong> controlled<br />

by elites yet still be of benefit to all sectors<br />

of village society, however much the elites<br />

retain control <strong>and</strong> ensure that they receive<br />

substantial benefits. However, three of the<br />

four communities which they studied are<br />

effectively urban neighborhoods <strong>and</strong> only<br />

Sekar Kamulyan (SE of B<strong>and</strong>ung) is a rural<br />

community. It is therefore important to<br />

consider how cluster development can<br />

best benefit societies <strong>and</strong> economies at a<br />

local <strong>and</strong> regional level.<br />

Reviewing some of the papers presented<br />

at the last Workshop in the context of a<br />

range of relevant publications, a series of<br />

challenges can be identified which need to<br />

be addressed to maximise the benefits of<br />

cluster development to households,<br />

communities <strong>and</strong> the broader regions of<br />

which they are part. We should also<br />

examine the extent to which there are<br />

common issues which this form of<br />

development faces in different South-East<br />

<strong>and</strong> South Asian countries. Other issues<br />

may also be emerging from current<br />

research <strong>and</strong> some of these will surely be<br />

discussed in our meetings here.<br />

Challenges in the social, economic,<br />

political <strong>and</strong> physical environment<br />

Social: There is a clear need to assess <strong>and</strong><br />

to find ways of strengthening social<br />

capital (social networks, associations etc.).<br />

The importance of social capital is<br />

frequently emphasized in the current<br />

literature. There is also a need to examine<br />

the degree of community cohesion <strong>and</strong><br />

inclusion – across race, political party,<br />

gender <strong>and</strong> class status. It is clearly a<br />

major element in one of the presentations<br />

on Bangladesh.<br />

<strong>Economic</strong>: Diversification of livelihoods to<br />

avoid excessive dependence on a small<br />

number of activities – to provide a cushion<br />

against hard times <strong>and</strong> environmental<br />

challenges (like volcanic ash clouds!) – is<br />

also important. So maybe clusters of<br />

complementary <strong>SME</strong>s are highly desirable<br />

only so long as they do not depend on<br />

satisfying relatively undifferentiated<br />

markets. For example, the dangers of<br />

dependence on tourism may be reduced if<br />

products are also sold via city retailers <strong>and</strong><br />

even overseas (using internet links) as well<br />

as direct sales to visitors.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Political: A greater degree of<br />

decentralised political control seems to be<br />

common in many of the countries where<br />

cluster development has been examined.<br />

In federal states, it may be difficult to<br />

Page | 9

David Preston - Helping <strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Benefit <strong>Local</strong> And Regional Societies And Economies<br />

ensure that the interests <strong>and</strong> priorities of<br />

regional political units (States in Malaysia)<br />

are included. Note that the important<br />

early progenitor of cluster development –<br />

One Village One Product (OVOP) – was<br />

based in the Japanese Prefecture of Oita<br />

<strong>and</strong> depended on regional rather than<br />

national support.<br />

The degree of dominance of the interests<br />

<strong>and</strong> priorities of high-level political actors<br />

must be examined if the dangers of topdown<br />

development are recognised. At a<br />

state level, what are essentially political<br />

issues <strong>and</strong> priorities – certainly in<br />

federated Malaysia – may be promoted<br />

that differ from those at a national<br />

government level.<br />

A further issue is frequently the extent<br />

that control has been devolved to the<br />

community <strong>and</strong>, within the community.<br />

Such devolution may ensure that the<br />

benefits of new initiatives are as widely<br />

shared as possible, as implied above as a<br />

social challenge.<br />

Physical: The development of <strong>SME</strong>s<br />

inevitably uses local common resources<br />

such as water <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>. It is necessary to<br />

safeguard access to natural assets/capital<br />

– forest, water, l<strong>and</strong> – especially important<br />

when traditional access (for native<br />

peoples) has been restricted or denied. It<br />

is important too to ensure that<br />

contamination of water (<strong>and</strong> to some<br />

extent air) by industrial production is<br />

regulated. An issue that is important to<br />

many people in some Malaysian villages<br />

where we have worked is how to make<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>oned l<strong>and</strong> available to village<br />

people. This may be particularly complex<br />

when many village people live much of<br />

the year far away <strong>and</strong> cannot use their<br />

l<strong>and</strong> in the way to which previous<br />

generations were accustomed.<br />

Page | 10<br />

Research challenges (a possible<br />

focus for debate during the<br />

meeting)<br />

o Little seems to have been published<br />

that evaluates the consequences of<br />

OVOP/<strong>SME</strong> etc. development on<br />

different categories of people (in<br />

particular according to gender <strong>and</strong><br />

age) in the area affected by such<br />

development. It would be good to<br />

hear what the group knows of such<br />

studies that have been carried out.<br />

o Can we assess the extent to which outmigration<br />

(for example of women from<br />

Java to Malaysia) mentioned by Hart<br />

(2004) from some rural areas has been<br />

checked by the development of new<br />

employment opportunities in rural<br />

areas?<br />

o It would be very useful to compare the<br />

results of such developments in<br />

different but perhaps comparable<br />

countries – maybe comparing<br />

Indonesia/Malaysia; Japan/Korea <strong>and</strong><br />

more generally S Asia <strong>and</strong> SE Asia. Is<br />

this something that the RRPG group<br />

could consider seeking funding to do?<br />

Future Challenges <strong>and</strong><br />

Opportunities<br />

DRAFT<br />

o Impact of new communications<br />

technologies (e.g. widespread fast<br />

Internet connectivity) on where <strong>and</strong><br />

what sort of industries can develop<br />

away from major urban centres.<br />

o Better communications by road, water<br />

etc may allow value chains to become<br />

shorter <strong>and</strong> perhaps more benefits to<br />

producers (Gibson <strong>and</strong> Olivia 2010)<br />

o New patterns of international cooperation<br />

creating broader areal<br />

synergies (using ASEAN, Asian<br />

<strong>Development</strong> Bank <strong>and</strong> even WTO as<br />

organisational models).

David Preston - Helping <strong>Cluster</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Benefit <strong>Local</strong> And Regional Societies And Economies<br />

Bibliography<br />

Ali, Abu Kasim <strong>and</strong> Mansor, Ahmad<br />

Ezanee (2006), Social capital <strong>and</strong><br />

rural community development in<br />

Malaysia. In Yokoyama, S <strong>and</strong><br />

Sakurai, T. (eds.) Potential of Social<br />

Capital for Community<br />

<strong>Development</strong> (Asian Productivity<br />

Organization: Tokyo), 141-171<br />

(accessible via www.apo-tokyo.org)<br />

Dasgupta, A <strong>and</strong> Beard, V.A. (2007)<br />

Community driven development,<br />

collective action <strong>and</strong> elite capture in<br />

Indonesia, <strong>Development</strong> <strong>and</strong> Change,<br />

38(2), 225-249.<br />

Tambunan, Tulus T H (2011) <strong>Development</strong><br />

of small <strong>and</strong> medium enterprises in a<br />

developing country. The Indonesian<br />

case, Journal of Enterprising<br />

Communities, People <strong>and</strong> Places in<br />

the Global Economy, 5(1), 68-82.<br />

Tremblay, D-G (2004) Networking, <strong>Cluster</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> Human Capital <strong>Development</strong>,<br />

Research Note 2006-08A, Université<br />

du Québec à Montréal.<br />

Gibson, J <strong>and</strong> Olivia, S (2010), The effect of<br />

infrastructure access <strong>and</strong> quality on<br />

non-farm enterprises in rural<br />

Indonesia, World <strong>Development</strong>, 38(5),<br />

717-726.<br />

Hart, G (2004), Power, labor <strong>and</strong><br />

livelihood: processes <strong>and</strong> change in<br />

rural Java: notes <strong>and</strong> reflections on a<br />

village revisited, Global Field Notes,<br />

University of California No. 2.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 11

Page | 12<br />

DRAFT

THE OVOP MOVEMENT AND ITS FARM RELATED<br />

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT<br />

Prof. Kunio Igusa<br />

Graduate School of International Cooperation Policy<br />

College of International Management. Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University. Japan.<br />

E-mail: kigusa@apu.ac.jp<br />

Presentation Tittle : The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial<br />

<strong>Development</strong><br />

Contents of Presentation :<br />

1. <strong>Economic</strong> Position of Oita <strong>and</strong> its <strong>Development</strong><br />

2. What’s the OVOP?<br />

3. Framework of Oita’s OVOP <strong>and</strong> its <strong>Development</strong><br />

4. New Trend of OVOP Mavement in Oita <strong>and</strong> Japan<br />

5. Introduction to the Cases of Neo-OVOP Activity in Oita<br />

• Ajimu-Wine Initiative<br />

• Management of Oyama Agriculture Cooperative<br />

• Caballeros Ham Studio Project<br />

• Collaborative Business of “Himeno-Kawahara” <strong>and</strong> “Azemichi Group”<br />

6. Conclusion<br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 13

Page | 14<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 15

Page | 16<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 17

Page | 18<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 19

Page | 20<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 21

Page | 22<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 23

Page | 24<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 25

Page | 26<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 27

Page | 28<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 29

Page | 30<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 31

Page | 32<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 33

Page | 34<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 35

Page | 36<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 37

Page | 38<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 39

Page | 40<br />

Kunio Igusa - The OVOP Movement <strong>and</strong> Its Farm Related Industrial <strong>Development</strong><br />

DRAFT

CHALLENGES IN RURAL ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN<br />

MALAYSIA<br />

Associate Professor Dr Ibrahim Ngah<br />

Department of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional Planning<br />

Universiti Teknologi Malaysia<br />

b-ibrhim@utm.my<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

This paper discusses the recent strategy of<br />

the Malaysian government to transform<br />

rural economy into a high income status, the<br />

issues <strong>and</strong> challenges. Since a couple of<br />

years, under the new Prime Minister Dato’<br />

SriMohd Najib bin Tun Hj. Abdul Razak, five<br />

major initiatives were launched i.e. 1<br />

Malaysia; Government Transformation<br />

Program (GTP), New <strong>Economic</strong> Model, Tenth<br />

Malaysia Plan <strong>and</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation<br />

Program (ETP). ETP is the government’s<br />

economic agenda in response to the goal of<br />

achieving high income developed nation by<br />

2020 that is both inclusive <strong>and</strong> sustainable.<br />

Based on the past trend of economic growth<br />

the logical path for achieving the goals is<br />

through the development of high value<br />

added secondary <strong>and</strong> tertiary sectors. The<br />

prospects for the rural sectors will be quite<br />

limited but some efforts have been taken to<br />

identify <strong>and</strong> nurture the growth of high<br />

value added activities of the rural sector. The<br />

author will examine the implication, issues<br />

<strong>and</strong> challenges for the rural sectors for the<br />

targeted economic transformation.<br />

RURAL CHANGE IN MALAYSIA<br />

Recent discussion on rural change in<br />

Malaysia has been dwelt with by Preston<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ngah (2011). During the past decades<br />

population growth continued to concentrate<br />

in a few urbanised region while rural areas<br />

experiencing outmigration. The share of<br />

rural population decrease from 73 per cent<br />

in 1970 to 37 per cent in 2007. Share of<br />

agriculture sector shrinking from 20 per cent<br />

in 1985 to 9 percent by 2007. National<br />

poverty rate fell from 49 per cent to less<br />

than 5 percent from 1970 to 2007. The<br />

percentage of households with piped water<br />

in rural areas had increased from 42 percent<br />

in 1980 to 90 per cent in 2005. Electricity<br />

supply was widely covered in rural areas of<br />

peninsular Malaysia in which all states<br />

recorded more than 90 per cent of<br />

households with electricity by 2000. Lower<br />

coverage of slightly less than 70 per cent<br />

was recorded in Sabah <strong>and</strong> Sarawak<br />

Changes on mobility of rural people were<br />

also remarkable with better quality of<br />

highways, increased ownership of vehicles<br />

<strong>and</strong> availability of public transport. More<br />

people are seeking works in distant<br />

metropolitan centres not only due to<br />

improved transportation but also general<br />

improvement in education levels. Non-farm<br />

works becoming more important in rural<br />

areas, including tourism.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Preston <strong>and</strong> Ngah (2011) visualized rural<br />

economic change in three dimensions<br />

(Figure 1). First the process of broadening<br />

involves new l<strong>and</strong> based activities such as<br />

protection <strong>and</strong> management of l<strong>and</strong><br />

resources, production of new crops which<br />

benefit local people as well as attract<br />

visitors. Second, re-grounding involves the<br />

use of existing <strong>and</strong> new human capital for<br />

off-farm activities such as offering transport<br />

for people <strong>and</strong> goods to nearby commercial<br />

Page | 41

centre, as well as activities such as home<br />

stay to diversify rural household income<br />

sources. Thirdly, deepening which is farming<br />

based including new farming methods such<br />

as organic or biodynamic using existing<br />

biodiversity in the form of wild plants, fish<br />

<strong>and</strong> other wild life with value added. The<br />

New l<strong>and</strong>-based work, park<br />

management<br />

New crops<br />

RURAL DEVELOPMENT<br />

PROGRAMMES<br />

The transformation of rural Malaysia was to<br />

large extent influenced by rural<br />

development initiatives undertaken by the<br />

government since independence in 1957.<br />

Ngah (2007) has made a comprehensive<br />

review of the rural development<br />

programmes <strong>and</strong> how it appears to improve<br />

living conditions of rural people, through<br />

improvement of rural economic activities,<br />

poverty eradication, provision of<br />

infrastructure <strong>and</strong> amenities. The summary<br />

of the strategies <strong>and</strong> programmes according<br />

Page | 42<br />

Ibrahim Ngah - Challenges in <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation in Malaysia<br />

Broadening<br />

Re-grounding<br />

process of change is dynamic <strong>and</strong> spread<br />

unevenly in space. Remote rural areas such<br />

as Sabah <strong>and</strong> Sarawak tended to be less<br />

connected by road <strong>and</strong> transportation.<br />

Places nearer to urban centres are more<br />

connected as well as better access to<br />

market.<br />

Deepening<br />

Using existing social capital<br />

Income from off-farm work<br />

Incomers with new ideas<br />

Organic/biodynamic production<br />

Short supply chain marketing<br />

Identified locality product<br />

Traditional product including wild plants<br />

<strong>and</strong> animals<br />

DRAFT<br />

to development periods from independence<br />

until now is shown in Figure 2. Two main<br />

strategies that produced huge impact are<br />

the new l<strong>and</strong> development <strong>and</strong> in-situ rural<br />

development. Entrepreneurial <strong>and</strong> SMI<br />

development are also focused for rural<br />

economic development. This includes the<br />

One District one Industry Program (SDSI)<br />

which was discussed in the previous RRPG<br />

meeting <strong>and</strong> also studies in detail by<br />

Professor Igusa team (see Igusa, 2009).<br />

Other initiatives under the Ministry of <strong>Rural</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> Regional <strong>Development</strong> include Training<br />

<strong>and</strong> Entrepreneur Supervision programme,<br />

Financial Support Scheme, <strong>Development</strong> of

Ibrahim Ngah - Challenges in <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation in Malaysia<br />

Business Premises, Marketing <strong>and</strong><br />

Promotion Programme, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> Tourism<br />

<strong>and</strong> Home stay.<br />

The recent strategy under New <strong>Economic</strong><br />

Model focus on achieving the goal of<br />

becoming a high income nation that is<br />

both inclusive <strong>and</strong> sustainable by 2020.<br />

Among the initiative is the New <strong>Economic</strong><br />

Transformation Programme.<br />

NEW ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION<br />

PROGRAMME<br />

The economic Transformation Program<br />

(ETP) is a comprehensive effort to<br />

transform Malaysia into a high-income<br />

nation by 2020. To achieved the vision of<br />

high-income nation, the target growth of<br />

the gross national income (GNI) is 6 per<br />

cent per annum with per capita GNI<br />

change from USD6,700 or RM23,700 in<br />

2009 to at least USD15,000 or RM48,000<br />

by 2020 (Malaysia, 2010). Under ETP, 12<br />

key economic growth areas were<br />

identified to be focused. These “12<br />

National Key <strong>Economic</strong> Areas (NKEAs)” are<br />

to receive priority for public investment<br />

<strong>and</strong> policy support. However, the main<br />

players <strong>and</strong> funding will come from<br />

private sector with public sector<br />

investment as catalyst to spark private<br />

sector participation.<br />

The identification of 12 NKEAs <strong>and</strong><br />

planning of ETP were based on labs1<br />

1<br />

A lab is an intense forum in which relevant<br />

participants (from private sector corporation <strong>and</strong><br />

public sector agencies) are brought together in a<br />

group with the objective of finding radical yet<br />

practical <strong>and</strong> specific solutions to problems.<br />

During the course of a lab, participants conduct<br />

brainstorming sessions to generate ideas, conduct<br />

analysis to determine the feasibility of those ideas<br />

<strong>and</strong> test <strong>and</strong> refine them with multiple<br />

stakeholders.<br />

discussion involving the key players in<br />

public <strong>and</strong> private sectors. The labs<br />

sessions establish detailed pelan,<br />

aspirations, strategies <strong>and</strong> actions,<br />

including requirement for funding,<br />

investment <strong>and</strong> labour for each NKEA.<br />

The ETP finally come out with 131 projects<br />

under 12 NKEAs which targeted for RM 1<br />

trillion expected impact to GNP <strong>and</strong> to<br />

create 3.3 million jobs.<br />

On the basis of the proposed projects, 24<br />

or 18 per cent of the projects are more<br />

related to rural sector (i.e. Palm oil <strong>and</strong><br />

agriculture), which expected to contribute<br />

12.9 per cent of GNI <strong>and</strong> 3.6 per cent of<br />

new jobs opportunities.<br />

The NKEAs under agriculture focus on<br />

selected activities which have high growth<br />

potential including aquaculture, seaweed<br />

farming, swiftlet nests, herbal products,<br />

fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetables <strong>and</strong> premium<br />

processed food (Table 2).<br />

The agriculture projects provides business<br />

opportunities such as snack industry,<br />

ornamental fish, aqua feed mill, herbal<br />

products distributors, poultry farming,<br />

mushroom farming, aqua export centre<br />

<strong>and</strong> packaged fruit production. Since the<br />

nature of business require high capital<br />

<strong>and</strong> technology not many rural people will<br />

be able to participate. Capital from big<br />

local <strong>and</strong> foreign companies is expected<br />

to undertake the businesses.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Page | 43

Table 1: Incremental GNI impact <strong>and</strong> new jobs created from 12 NKEAs in 2020<br />

Page | 44<br />

Ibrahim Ngah - Challenges in <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation in Malaysia<br />

NKEAs Projects<br />

GNI 2020<br />

(RM<br />

Billions)<br />

New jobs by 2020<br />

(Thous<strong>and</strong>s)<br />

% GNI<br />

Oil, Gas & Energy 12 131 52 11.0<br />

Palm Oil 8 125 42 10.5<br />

Financial services 10 121 275 10.2<br />

Wholesale & Retail 15 108 595 9.1<br />

Tourism 12 67 497 5.6<br />

Business services 8 59 246 5.0<br />

Electronics <strong>and</strong> electrical 11 53 157 4.5<br />

Communications <strong>and</strong> infrastructure 10 36 43 3.0<br />

Healthcare 6 35 181 2.9<br />

Education 13 34 536 2.9<br />

Agriculture 16 29 75 2.4<br />

Greater Kuala Lumpur/Klang Valley* 10 392 553 32.9<br />

131 1190 3252 100.0<br />

* Some portion of income from NKEAs are overlapping<br />

Source: Malaysia 2010:pp.28, 47-54<br />

Table 2: 16 entry points projects for the transformation of agriculture sectors:<br />

Agriculture Projects<br />

2020 GNI<br />

(RM Million)<br />

Jobs<br />

Created<br />

1 Exp<strong>and</strong>ing the production of swiftlet nests 4,541.2 20,800<br />

2 Unlocking value from Malaysia’s biodiversity through herbal<br />

products<br />

2,213.9 1,822<br />

3 Upgrading<br />

vegetables<br />

capabilities to produce premium fruit <strong>and</strong> 1,571.5 9,075<br />

4 Venturing into commercial scale seaweed farming in Sabah 1,410.6 12,700<br />

5 Farming through integrated cage aquaculture systems 1,383.0 10,072<br />

6 Scaling up <strong>and</strong> strengthening of paddy in other irrigated area 1,370.3 (9,618)<br />

7 Replicating integrated aquaculture model (IZAQs) 1,273.2 11,890<br />

8 Scaling up <strong>and</strong> strengthening paddy farming in Muda Area 1,033.6 (14,880)<br />

9 Securing foreign direct investment in agriculture 819.9 1,208<br />

biotechnology<br />

10 Strengthening the export capability of the processed food<br />

industry<br />

884.3 4,928<br />

11 Establishing a leadership position in regional breeding services 466.6 5,390<br />

12 Establishing dairy clusters in Malaysia 326.3 761<br />

13 Strengthening current anchor companies in cattle feedlots 182.9 2,000<br />

14 Rearing cattle in oil palm estates 150.0 3,600<br />

15 Investing in foreign cattle farming 116.5 NA<br />

16 Introducing fragrant rice variety for non-irrigated areas 100.1 NA<br />

Source: Malaysia, 2010 pp. 47<br />

DRAFT

CHALLENGES<br />

Issues of Inclusiveness<br />

• Projects proposed require big<br />

investment from private sector.<br />

• Most likely not many local people can<br />

participate in the projects.<br />

• <strong>Rural</strong> people are diverse such as some<br />

have l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> many others did not<br />

owned l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

• The strategy for rural transformation to<br />

be effective <strong>and</strong> inclusive should cover<br />

wide ranges of approaches that cover<br />

the various dimension of rural change.<br />

Labour Force<br />

Ibrahim Ngah - Challenges in <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation in Malaysia<br />

Although the proposed projects could<br />

create employment opportunities, but<br />

currently there has been shortage of<br />

manpower in the rural areas.<br />

Uneven Distribution of NKEAs Projects<br />

The nature of the proposed NKEAs projects<br />

tended to be urban based. It will create<br />

further concentration of economic activities<br />

in urban areas, particularly the Greater Kuala<br />

Lumpur region.<br />

Migration <strong>and</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> Depopulation<br />

Majority of the NKEAs projects are urban in<br />

nature <strong>and</strong> benefitted large metropolitan<br />

areas such as Kuala Lumpur<br />

Conurbation/greater Kuala Lumpur. It<br />

strengthened the process of convergences<br />

of the existing concentration of economic<br />

activities in core region, thus created<br />

polarisation effects <strong>and</strong> continuing<br />

depopulation of rural people.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Igusa, Kunia (2009), <strong>Rural</strong> Entrepreneurs <strong>and</strong><br />

SDSI Policy in Malaysia: How malaysian<br />

Type of OVOP Function, in Igusa <strong>and</strong><br />

Ab. Latif (ed) Workshop Proceedings<br />

One District One Industry, Ritsumeika<br />

Asia Pacific University <strong>and</strong> University<br />

Malaysia Kelantan<br />

Malaysia (2010), <strong>Economic</strong> Transformation<br />

Programme, A Road Map for Malaysia,<br />

Puterajaya: PEMANDU, Jabatan<br />

Perdana Menteri .<br />

Malaysia (2011), Population Distribution <strong>and</strong><br />

Basic Demographic Characteristics<br />

2010, Population <strong>and</strong> Housing Census<br />

of Malaysia 2010, Putrajaya:<br />

Department of Statistics.<br />

Malaysia (2011a), Preliminary Count report,<br />

Population <strong>and</strong> Housing Census of<br />

Malaysia 2010, Putrajaya: Department<br />

of Statistics.<br />

Ngah, I (2009), <strong>Rural</strong><strong>Development</strong> in<br />

Malaysia, in Ishak Yussof ed. Malaysia’s<br />

Economy, Past, Present & Future,<br />

Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Strategic<br />

Research Centre, pp. 23-60.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Preston, D. A <strong>and</strong> Ngah, I (2011) Change in<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> Malaysia, paper summitted to<br />

Journal of <strong>Rural</strong> Studies (under review)<br />

Page | 45

Page | 46<br />

DRAFT

THE OTHER SIDE OF LOCAL SUPPORTING ECONOMIC OF<br />

RURAL AREAS IN JAVA<br />

Dr. Joesron Alie Syahbana<br />

Master Program of Urban <strong>and</strong> Regional <strong>Development</strong><br />

Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia<br />

yoesrona@yahoo.com<br />

BEYOND THE REACH OF RURAL<br />

POOR’S WELFARE<br />

Most of active volcanos in Indonesia are<br />

located in Java Isl<strong>and</strong> which in one h<strong>and</strong>,<br />

they are related to the danger of natural<br />

disaster, in other h<strong>and</strong> created best farm<br />

l<strong>and</strong>s in Indonesia. No wonder, this smallest<br />

of five main isl<strong>and</strong>s in Indonesia has been<br />

high concentration population of Indonesia<br />

for many centuries. Recently, Java has been<br />

inhabited by more than 60 % of Indonesian<br />

population. So, intensive urbanization <strong>and</strong><br />

industrialization with their implications are<br />

going to be inevitable process in this isl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

In one side, both urbanization <strong>and</strong><br />

industrialization process are going to be<br />

economic engine for local <strong>and</strong> national<br />

economic growth, in other side when the<br />

existing small fertilized farm l<strong>and</strong>s in Java<br />

are not sufficient anymore to support local<br />

economic of rural areas, very small to small<br />

farmers <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>less farmers as well are<br />

hard to depend their future social welfare<br />

on both farm l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> agricultural<br />

activities.<br />

Those farmers are still hard to earn other<br />

incomes from non-agricultural activities<br />

(industrial <strong>and</strong> urban sectors) since most of<br />

rural-urban linkages which are expected to<br />

increase their social welfare are still<br />

rudimentary. In straight words, agricultural,<br />

social services, <strong>and</strong> other rural development<br />

program are still largely beyond the reach of<br />

the rural poor’s welfare in Java Isl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Therefore, it is unargumentable that rural<br />

areas in Java are going to be a source of<br />

mass poverty which any time widely spread<br />

over urban areas in many parts of national<br />

geographic areas <strong>and</strong> other parts of the<br />

world as well.<br />

Only with wide-ranging concepts of<br />

agricultural, industrial, rural development,<br />

rural - urban linkage development as well as<br />

its appropriate applications will effectively<br />

reduce the mass poverty as a main problem<br />

which is prevalent founded in most of rural<br />

areas of Java. It is different situation to<br />

introduce <strong>and</strong> to promote industrial<br />

revolution between urban <strong>and</strong> rural areas,<br />

even related to carefully green industrial<br />

revolution applications because of low<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard social welfare, sensitive physical<br />

environment, <strong>and</strong> improper institutional<br />

development.<br />

DRAFT<br />

Agricultural based-sectors’ role keep on<br />

tending to decrease in GNP, although some<br />

modernization ways of agricultural <strong>and</strong> rural<br />

industrial development have been injected.<br />

The problem is most of villagers or farmers<br />

are not ready to go in. Furthermore, sound<br />

is that for new generation of villagers,<br />

industrialization <strong>and</strong> urbanization sectors<br />

are much more attractive rather than to live<br />

longer in the rural areas with daily dirty <strong>and</strong><br />

muddy works in the farm l<strong>and</strong>s. So, mass<br />

migration (with poverty <strong>and</strong> low social<br />

welfare) would be more spread over urban<br />

areas in Indonesia, even overseas soon.<br />

Fortunately, a part of villagers are still very<br />

creative, innovative, <strong>and</strong> dynamic to create<br />

their supporting economies, however.<br />

Page | 47

Although a part of rural areas have succeed<br />

to escape from local depressed economies,<br />

another part of them are still in struggling,<br />

the other part are still found depend on<br />

“the other side of supporting economies”<br />

which some of them tend to be establish<br />

<strong>and</strong> to be a part of their specific supporting<br />

economies for many decades. Those rural<br />

types are not really poor, but what they are<br />

doing to support their local economies are<br />

just incompatible with Indonesian value<br />

system (even universal value system).<br />

However, only few studies, researches, <strong>and</strong><br />

development programs are interested or<br />

pay more attention to them. Sound like they<br />

were never touchable or considerable.<br />

The search for an appropriate combination<br />

of different policies <strong>and</strong> instruments for<br />

poverty-oriented rural development which<br />

arise some arguments <strong>and</strong> debates. The<br />

current debate is characterized by the<br />

following pairs of opposites: (i) accelerated<br />

economic growth versus general social<br />

development; (ii) effective promotion of<br />

local <strong>and</strong> regional projects versus countrywide<br />

programmes at sectoral <strong>and</strong> macro<br />

level; (iii) complex, integrated projects<br />

versus sectoral programmes geared to<br />

specific target groups; (iv) the strengthening<br />

of government organizational structures<br />

versus promotion of the self-organization of<br />

the beneficiaries; (v) the supply orientation<br />

of public services versus dem<strong>and</strong><br />

orientation; (vi) blueprint planning versus<br />

open planning processes (Gsänger, 1994).<br />

DEVELOPING BRIGHT SUPPORTING<br />

ECONOMIC<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> development in Java has played an<br />

important role in both national <strong>and</strong><br />

international development cooperation over<br />

the past decades. No wonder, nowadays<br />

some rural areas in Java have been rapidly<br />

developing not only affected by local <strong>and</strong><br />

national urbanization <strong>and</strong> industrialization<br />

but also the global one since they have<br />

been being linked by both national <strong>and</strong><br />

Page | 48<br />

Joesron Alie Syahbana - The Other Side of <strong>Local</strong> Supporting <strong>Economic</strong> of <strong>Rural</strong> Areas in Java<br />

global rural <strong>and</strong> urban linkages. Both the<br />

national <strong>and</strong> international flows of people,<br />

goods, resources, capital, knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

experiences become ever more important<br />

<strong>and</strong> increasingly present in all cities, though<br />

in differing proportions (Lynch, 2005).<br />

Each rural area in Java tends to have a<br />

specific non-agriculture business affected by<br />

both heritage <strong>and</strong> new concepts basedbusiness,<br />

traditional <strong>and</strong> current market<br />

influenced by wider rural-urban linkages.<br />

Supporting rural economic development in<br />

Java varies from place to place depend on<br />

local potencies <strong>and</strong> linkage with wider<br />

economic activities. Most of them naturally<br />

grow <strong>and</strong> develop, some are injected by the<br />

development concept from external<br />

institutions. <strong>Rural</strong> areas in surrounding<br />

Pekalongan, Jepara, Kudus, Surakarta,<br />

Yogyakarta, Tasikmalaya, Tegal, B<strong>and</strong>ung,<br />

Bogor, Malang, Magelang, <strong>and</strong> others have<br />

recognized as centers of small <strong>and</strong> medium<br />

scale industries in Java which have grown<br />

not only from after independence periods,<br />

but also long before independence periods.<br />

Even some of them are found naturally<br />

linked by traditional cluster system since<br />

their activities engage within arrays of<br />

internally <strong>and</strong> externally by linked industries<br />

<strong>and</strong> other important entities to compete<br />

with others (Porter, 1998).<br />

DRAFT<br />

Recently, some rural area successfully<br />

produce from st<strong>and</strong>ard to high quality<br />

products which a part of exported goods<br />

<strong>and</strong> even to be a part of both national <strong>and</strong><br />

global br<strong>and</strong>ed products. Generally, their<br />

products are related to high specific skill<br />

h<strong>and</strong>y-crafts made of woods, leather, metal,<br />

textiles, foods, <strong>and</strong> other materials order or<br />

requested by both national <strong>and</strong> global<br />

companies. Most of potential products of<br />