COUNTERSTROKE AT SOLTSY - Strategy & Tactics Press

COUNTERSTROKE AT SOLTSY - Strategy & Tactics Press

COUNTERSTROKE AT SOLTSY - Strategy & Tactics Press

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

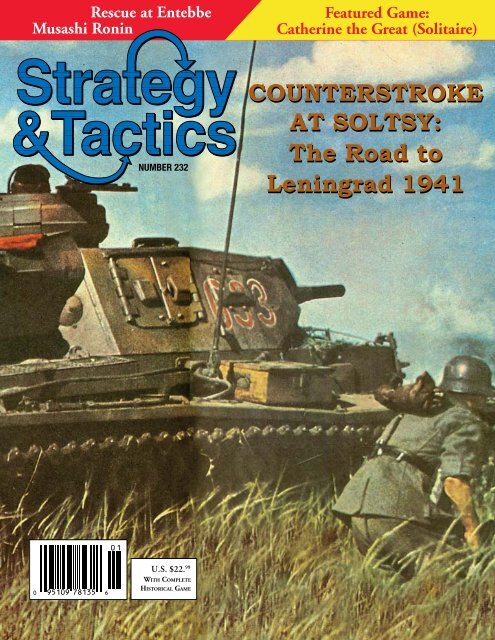

Rescue at Entebbe<br />

Musashi Ronin<br />

Number 232<br />

U.S. $22. 99<br />

Wi t h Co m p l e t e<br />

historiCal Ga m e<br />

Featured Game:<br />

Catherine the Great (Solitaire)<br />

<strong>COUNTERSTROKE</strong><br />

<strong>AT</strong> <strong>SOLTSY</strong>:<br />

The Road to<br />

Leningrad 1941<br />

strategy & tactics 1

War on Terror<br />

This is the third game in the Lightning series. Fight the war on terror with America’s<br />

cutting edge weapon systems! You have been charged with hunting down terrorists<br />

aiding regions around the world and toppling their corrupt governments. To accomplish<br />

this, you have been given command of the latest weapons and best personnel<br />

America has to offer. You get to command elements of the Air Force, Army, Navy,<br />

Marines, Special Forces and Propaganda Warfare. War on Terror is an ultra-low<br />

complexity card game for all ages. The focus is on fast card play, strategy, and fun<br />

interactive game play for 2-4 players. Includes 110 full color playing cards and one<br />

sheet of rules.<br />

D-Day<br />

June 6, 1944, the day that decided the fate of World War II in Europe. Now you command the<br />

Allied and Axis armies as each struggles to control the five key beaches along the Normandy<br />

coastline. If the Allied troops seize the beaches, Germany is doomed. But if the assault fails,<br />

Germany will have the time it needs to build its ultimate weapons. You get to make vital command<br />

decisions that send troops into battle, assault enemy positions, and create heroic sacrifices<br />

so others can advance to victory!<br />

MiDWay<br />

From June 4th to June 6th of 1942, a massive battle raged<br />

around the tiny Pacific island of Midway that changed the<br />

course of World War II. The victorious Imperial Japanese<br />

Navy was poised to capture the airfield on the island of<br />

Midway and thus threaten Hawaii and the United States.<br />

The only obstacle in their path was an outnumbered US<br />

fleet itching for payback for Pearl Harbor. You get to command<br />

the US and Japanese fleets and their squadrons of fighter planes, torpedo<br />

bombers and dive bombers in this epic battle!<br />

TiTle<br />

QTY Price TOTAl<br />

Lightning War on Terror $19.99<br />

Lightning midway $19.99<br />

Lightning D-Day $19.99<br />

Shipping Charges<br />

Ziplocks count as 2<br />

for 1 for shipping.<br />

1st item Adt’l items Type of Service<br />

$8 $2 UPS Ground/US Mail Domestic Priority<br />

15(20) 4 UPS 2nd Day Air (Metro AK & HI)<br />

14(10) 2(7) Canada, Mexico (Express)<br />

17(25) 7(10) Europe (Express)<br />

2<br />

20(25)<br />

#232<br />

9(10) Asia, Africa, Australia (Express)<br />

LighTning<br />

SerieS<br />

a Fa s t & ea s y pl ay i n G Gr o u p o F Ca r d Ga m e s<br />

SUB To Ta l<br />

TaX (Ca. RES.)<br />

$<br />

S&H<br />

$<br />

ToTal oRDER<br />

$<br />

PO Box 21598, Bakersfield CA 93390-1598<br />

• (661) 587-9633 •fax 661/587-5031<br />

• www.decisiongames.com

Leningrad<br />

TiTle<br />

QTY Price TOTAl<br />

Shipping Charges<br />

Easy to Play Games<br />

This great introductory game covers Army Group North’s drive to Leningrad<br />

during the summer of 1941. It features hidden values for the Soviet<br />

units that only become known when they are involved in combat. Surprise<br />

attacks are essential to the success of either side, and the arrival of reinforcements<br />

can dramatically shift the course of battle. Leningrad features enough<br />

surprises to ensure that each game will be different and exciting.<br />

Components: 100 counters, 11” x 17” mapsheet, 8-page rule book. $14. 00<br />

Across Suez<br />

On 6 October 1973, troops of the Egyptian Third Army performed a<br />

masterful surprise crossing of the Suez Canal, overwhelmed the emplaced<br />

Israeli defenders along the Bar Lev line, and established themselves in force<br />

in the Sinai. The Battle of Chinese Farm is an operational level game that<br />

simulates the great battle between the Egyptian Second and Third Armies and the Israeli Defense Force as they<br />

battle for Suez canal. Included are special rules for commandos, Egyptian Marines and paratroopers.<br />

Components: 80 counters, 1 mapsheet, 8-page rule book. $10. 00<br />

Leningrad $14.00<br />

Across Suez $10.00<br />

Captivation $25.00<br />

1st item Adt’l items Type of Service<br />

$8 $2 UPS Ground/US Mail Domestic Priority<br />

15(20) 4 UPS 2nd Day Air (Metro AK & HI)<br />

14(10) 2(7) Canada, Mexico (Express)<br />

17(25) 7(10) Europe (Express)<br />

20(25) 9(10) Asia, Africa, Australia (Express)<br />

Captivation<br />

Be the first player to move all your cones around the board and<br />

into your home. Captivation plays like backgammon, only better.<br />

Unlike backgammon, everyone moves in the same direction. Two<br />

cones of the same color on one space are safe, however a single<br />

cone can be captured. When you land on a space with only one<br />

cone of another player on it, you stack your cone on top of it and<br />

capture it. Until you move that cone again, his or her cone can’t<br />

move! A captivating family game for two to four players that can<br />

be played in 30-60 minutes.<br />

Components: mounted board, rules sheet, dice and 40 cones. $25. 00<br />

SUB To Ta l<br />

TaX (Ca. RES.)<br />

$<br />

S&H<br />

$<br />

ToTal oRDER<br />

$<br />

PO Box 21598, Bakersfield CA 93390-1598<br />

• (661) 587-9633 •fax 661/587-5031<br />

• www.decisiongames.com<br />

strategy & tactics 3

Editor-in-Chief: Joseph Miranda<br />

FYI Editor: Ty Bomba<br />

Design • Graphics • Layout: Callie Cummins<br />

Copy Editors: Ty Bomba, Jason Burnett, and Jay<br />

Cookingham.<br />

Map Graphics: Meridian Mapping<br />

Publisher: Christopher Cummins<br />

Advertising: Rates and specifications available<br />

on request. Write P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield CA<br />

93390.<br />

SUBSCRIPTION R<strong>AT</strong>ES are: Six issues per year—<br />

the United States is $99.97/1 year. Canada surface<br />

mail rates are $110/1 year and Overseas surface<br />

mail rates are $130/1 year. International rates are<br />

subject to change as postal rates change.<br />

Six issues per year-Newsstand (magazine only)the<br />

United States is $29.97/1 year. Canada surface<br />

mail rates are $36/1 year and Overseas surface<br />

mail rates are $42/1 year.<br />

All payments must be in U.S. funds drawn on a<br />

U.S. bank and made payable to <strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong><br />

(Please no Canadian checks). Checks and money<br />

orders or VISA/MasterCard accepted (with a<br />

minimum charge of $40). All orders should be sent<br />

to Decision Games, P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield<br />

CA 93390 or call 661/587-9633 (best hours to<br />

call are 9am-12pm PDT, M-F) or use our 24-hour<br />

fax 661/587-5031 or e-mail us from our website<br />

www.decisiongames.com.<br />

NON U.S. SUBSCRIBERS PLEASE NOTE: Surface<br />

mail to foreign addres ses may take six to ten<br />

weeks for delivery. Inquiries should be sent to<br />

Decision Games after this time, to P.O. Box 21598,<br />

Bakersfield CA 93390.<br />

STR<strong>AT</strong>EGY & TACTICS ® is a registered trademark<br />

for Decision Games’ military history magazine.<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong> (©2005) reserves all rights<br />

on the contents of this publication. Nothing may<br />

be reproduced from it in whole or in part without<br />

prior permission from the publisher. All rights<br />

reserved. All correspondence should be sent<br />

to decision Games, P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield<br />

CA 93390.<br />

STR<strong>AT</strong>EGY & TACTICS (ISSN 1040-886X) is published<br />

bi-monthly by Decision Games, 1649 Elzworth St. #1,<br />

Bakersfield CA 93312. Periodical Class postage paid<br />

at Bakersfield, CA and additional mailing offices.<br />

Address Corrections: Address change forms to<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong>, PO Box 21598, Bakersfield CA<br />

93390.<br />

4 #232<br />

ConTEnTS<br />

F E A T U R E S<br />

6 Counterstroke at Soltsy:<br />

July 1941 the Road to Leningrad<br />

The Blitzkrieg receives an early check as the Red Army<br />

takes on the Wehrmacht.<br />

by Vance von Borries<br />

20 Catherine the Great:<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> in the Age of Enlightenment<br />

In an era of limited wars and enlightened monarchs,<br />

the Russians build an empire.<br />

by Joseph Miranda

F E A T U R E S<br />

RULES<br />

R1 C<strong>AT</strong>hERinE ThE GRE<strong>AT</strong><br />

by Joseph Miranda<br />

ConTEnTS<br />

42 Entebbe: Turning point of Terrorism<br />

The Israelis strike back and turn the tide in the<br />

war on terrorism.<br />

by Kelly Bell<br />

52 miyamoto musashi:<br />

Legendary Swordsman<br />

Japan’s greatest samurai creates a legacy of<br />

both war and philosophy.<br />

by Ltc a Pope<br />

dEpARTmEnTS<br />

31 for your information<br />

the maccabees:<br />

Hammer of the Hebrews<br />

by Kelly Bell<br />

Codename Blue Peacock<br />

by Mark Lardas<br />

naval mine Warfare During the Cold<br />

War<br />

by Carl Schuster<br />

Peace in Cambodia: untaC<br />

by Peter Schutze<br />

37 ThE LonG TRAdiTion<br />

58 mEGA FEEdbACk<br />

number 232<br />

jan/feB 2006<br />

strategy & tactics 5

<strong>COUNTERSTROKE</strong> <strong>AT</strong> <strong>SOLTSY</strong>:<br />

July 1941<br />

on the Road to Leningrad<br />

6 #232<br />

Axis units are in italics; Allied units are in plain text.<br />

By Vance von Borries<br />

The objective was Leningrad. From the shores of<br />

the Baltic in East Prussia to the marshes around Lake<br />

Ladoga, Germany’s Army Group North, commanded<br />

by Field Marshal von Leeb, struggled over an immense<br />

battlefield. Operation BARBAROSSA, the invasion of<br />

the Soviet Union, opened on 22 June 1941 and Leningrad<br />

was to be wiped from the earth. To the Nazis, the<br />

city was a symbol of the revolutionary origins of the<br />

Bolsheviks whose destruction would be an immense<br />

propaganda victory. For the Soviets, the defense of<br />

Leningrad was a test of will. The merciless struggle<br />

would be fought on the many roads to Leningrad. And<br />

one of those roads ran through the small city of Soltsy.<br />

It was there the timetable of conquest was upset and<br />

Army Group North lost its momentum.<br />

Plans<br />

Army Group North included two infantry armies<br />

(16 th and 18 th ) and one Panzer Group (4 th , the equivalent<br />

of an army, with Col. Gen. E. Hoepner commanding).<br />

In accordance with original BARBAROSSA<br />

instructions, debate began over the path of future operations.<br />

The plan was prepared under the guidelines<br />

of the Army General Staff (OberKommando der Heer,<br />

OKH) and were finalized in Army Group North’s order<br />

of 8 July. That order assumed that a Finnish offensive<br />

along the shores Lake Ladoga and an advance of 3 rd<br />

Panzer Group from Army Group Center northeast via<br />

Nevel toward Velizh would occur shortly after 10 July.<br />

Those operations were supposed to tie down Soviet<br />

forces facing Army Group North’s flanks. With Leningrad<br />

cut off, 4 th Panzer Group would take the city.<br />

Sixteenth Army would advance on Kholm and send<br />

a flanking force against Velikie Luki to protect the

strategy & tactics 7

8 #232<br />

army group’s southeastern flank. Eighteenth Army’s<br />

mission was to conquer Estonia and capture the Soviet<br />

naval bases at Tallinn and Paldiski. Units of 4 th Panzer<br />

Group were to move directly north to occupy the Narva<br />

crossings near Kingisepp, thereby preventing a withdrawal<br />

of enemy units from Estonia. The weakness to<br />

the plan was that until 16 th Army could move up, 4 th<br />

Panzer Group would have to defend alone against enemy<br />

counterattacks from east of Lake Ilmen.<br />

On 8 July OKH issued a directive significantly<br />

changing the plan of Army Group North. Army Chief<br />

of Staff Gen. Franz Halder was concerned about Army<br />

Group Center’s battle of encirclement in the Smolensk<br />

area. There were insufficient mobile forces to complete<br />

the envelopment, so 3 rd Panzer Group would not<br />

move north after all.<br />

More, Hitler wanted 4 th Panzer Group to cut off<br />

Leningrad to the east and southeast. Halder, who at<br />

the time assumed Army Group North enjoyed a clear<br />

numerical superiority, readily agreed to the plan.<br />

That shifted the main effort of the offensive to the<br />

Novgorod-Volkhov-Shlisselburg line and was also intended<br />

as support for the Finnish attack from the north.<br />

The Army General Staff also ordered infantry divisions<br />

to move toward Leningrad to make the mobile<br />

units available for other tasks as soon as possible. In<br />

sum, OKH stopped the preparations for a direct assault<br />

on Leningrad and demanded the shift of the main effort<br />

to the army group’s right. Leningrad would not be<br />

taken by direct assault. Instead, it would be by-passed<br />

from the southeast, encircled, and placed under siege.<br />

Army Group North accepted the order without<br />

much comment. That can only be explained by von<br />

Mastermind at work: FM von Leeb plans the attack.<br />

Leeb’s belief the Soviets would continue to withdraw<br />

if attacked, as had been the case up until then. More,<br />

the army group staff believed Soviet forces southeast<br />

of Leningrad were the last units in the area capable of<br />

offering serious resistance. And von Leeb welcomed<br />

the opportunity to rest his hard-driving formations and<br />

bring up fresh troops. He even doubted the Soviets<br />

were determined to hold the approaches to Leningrad.<br />

The View from Moscow<br />

Stalin and the Red Army Staff (STAVKA) divided<br />

the Eastern Front from the Baltic to the Black Sea into<br />

three “Glavkom,” or Directions, a Soviet military term<br />

with no western equivalent. Each Direction—Northwestern,<br />

Western and Southwestern—was roughly the<br />

equivalent of a German Army Group. Marshal K.Y.<br />

Voroshilov was in command of the Northwestern Direction.<br />

Stalin needed people he could trust to command<br />

each Glavkom, and Voroshilov was exactly that<br />

kind of man. He was a crony of Stalin’s from the days<br />

of the Russian Civil War and for some time he had<br />

been the People’s Commissar (Minister) of Defense.<br />

When Voroshilov arrived in Leningrad on 10 July,<br />

he had, on paper, at least 30 divisions available for<br />

the defense of the Northwestern Front; however, only<br />

five of them were at full strength, the rest averaging<br />

only about a third of their authorized men and equipment.<br />

Accordingly, the Soviet defense was to rely on<br />

fortifications. The Luga Line was the first of several<br />

fortified systems defending the approaches to Leningrad.<br />

About 30,000 civilians worked around the clock<br />

to build it. At the moment when Army Group North<br />

encountered the outer defenses of the Luga Line, the<br />

Luga Operational Group, with regular Red Army divisions<br />

backed by militia, had some 300 kilometers to<br />

hold. Reinforcements were committed out of the reserves<br />

held in Leningrad.<br />

Directly in the path of 4th Panzer Group’s advance<br />

was Gen. Lt. V.I. Morozov’s 11th Army. It had been in<br />

action since the beginning of the invasion, and its one<br />

tank and six rifle divisions were understrength. Soviet<br />

rifle divisions were normally expected to hold combat<br />

frontages of six to eight kilometers, but the rifle<br />

divisions on the front line were required to hold three<br />

times that. On 10 July, Army Group North outnumbered<br />

the Northwestern Front by 2.4 to 1 in infantry,<br />

4 to 1 in guns, 5.8 to 1 in mortars, 1.2 to 1 in tanks,<br />

and 10 to 1 in aircraft. When the Germans attacked,<br />

the Soviets retreated immediately. That was mainly<br />

due to the fact they were overextended and heavily<br />

outgunned, but also because they were out of range<br />

of army command. It seemed disaster had struck once<br />

again for the Red Army. Morozov was left with only<br />

blocking forces to stop the German drive to Leningrad<br />

and Novgorod.

Opening Moves<br />

Fourth Panzer Group began its advance on 10 July<br />

with two motorized corps using divergent roads. Manstein’s<br />

56 th Motorized Corps (8 th Panzer and 3 rd Motorized<br />

Divisions) advanced on the right in the direction<br />

of Porkhov-Soltsy-Shimsk-Novgorod. On the left was<br />

Reinhardt’s 41st Motorized Corps with three mobile<br />

divisions (1 st Panzer, 6 th Panzer, 36 th Motorized) and<br />

one infantry division (269 th ). Reinhardt was moving<br />

up the Pskov-Luga-Leningrad axis. Fourth Panzer<br />

Group was determined to get to the starting positions<br />

for the Leningrad encirclement within four days. That<br />

represented an advance of about 300 kilometers (190<br />

miles), a preposterous distance for the time allowed.<br />

The Germans could succeed only if they encountered<br />

neither resistance nor difficult terrain.<br />

A further dilemma arose when Fourth Panzer<br />

Group found itself unable to protect its 200 kilometer<br />

long eastern flank and, as events would prove, not<br />

even its own rear. On the other hand, all five of the<br />

mobile divisions leading the advance were in excellent<br />

condition, perhaps the peak of their effectiveness<br />

for the war. The one exception was the SS Totenkopf<br />

Motorized Infantry Division. It had taken considerable<br />

casualties in heavy fighting on the Stalin Line fortifications<br />

at Sebezh. As a result, Totenkopf had to disband<br />

one of its three motorized infantry regiments and was<br />

not in position to advance with the rest of 56 th Motorized<br />

Corps. On 12 July, Army Group North ordered the<br />

SS division moved to Porchov for re-organization.<br />

Nonetheless, 56 th Motorized Corps advanced swiftly.<br />

On 11 July Porchov was taken by Gen. Maj. Curt<br />

Jahn’s 3rd Motorized Division. Following behind was<br />

Correlation of Forces, Morning, 15 July 1941<br />

Soviets Ratio Germans<br />

Personnel 50,500 1.6 – 1.0 30,700<br />

Tanks and assault guns 105 .5 – 1.0 192<br />

Artillery pieces 199 1.5 – 1.0 132<br />

Comparison of Soviet 70 th Rifle Division to<br />

German 8 th Panzer Div. at Soltsy<br />

Soviet<br />

70 th Rifle Div<br />

8 th Panzer. Div.<br />

Soviet Account<br />

likely # of<br />

Germans<br />

All Soviets at<br />

Soltsy, 15 July<br />

Soviet: German<br />

Ratio<br />

Personnel 15,333 16,120 14,900 30,000 2.0 – 1.0<br />

Tanks 16 201 186 56 .3 – 1.0<br />

Artillery 53 60 48 95 2.0 – 1.0<br />

Note 1: Estimated total then engaged<br />

Note 2: Germans likely had still fewer tanks due to mechanical breakdowns.<br />

Gen. Maj. Eric Brandenburger’s 8 th Panzer Division,<br />

which moved quickly toward Sitnya, some 20 kilometers<br />

west of Soltsy. But 56 th Motorized Corps achieved<br />

little breadth in its penetration. Each of these two divisions<br />

advanced with only one assault group to the front.<br />

Facing them were small blocking forces of Soviet armor<br />

and infantry from Gen. Maj. M.L. Chernyavsky’s<br />

1 Mechanized Corps. To the Soviet rear, the remains of<br />

Col. V.K. Gorbachev’s 202 Motorized Rifle Division,<br />

reinforced with NKVD Destroyer Detachments, organized<br />

the city of Sol’tsy for defense, mobilizing armed<br />

detachments of civilians.<br />

With considerable resistance developing along the<br />

Luga road, on 12 July Hoepner switched the three mobile<br />

divisions of Reinhardt’s corps to the northwest.<br />

He hoped for a breakthrough to Leningrad over the<br />

Ivanovskoye and the Koporye plateaus, where the terrain<br />

was open. That left only infantry on the road in<br />

front of Luga.<br />

Hoepner’s decision was clearly incompatible with<br />

the OKH orders of 8 July. Nonetheless, the episode<br />

provides a good example of the comparative independence<br />

panzer commanders had at that time in the<br />

war. Manstein later writes that the change of direction<br />

was: “…a particularly risky move when one<br />

considered that even though the enemy<br />

forces engaged by the corps to date had<br />

been outfought, they were far from annihilated…Be<br />

that as it may, we were still<br />

convinced that the corps would continue<br />

to find its safety in speed of movement.”<br />

strategy & tactics 9

10 #232<br />

Manstein Alone<br />

On 11 July, Manstein issued Corps Order #21. The<br />

8th Panzer Division would advance along the axis<br />

Porchov-Borovichi-Sukhlovo-Soltsy with the objective<br />

being the bridge over the Mshaga River. The 3 rd<br />

Motorized Division would advance along the axis<br />

Borovichi-Saklinye-Vsheli-Mal Utorgosh, with the<br />

objective being the bridge over the Mshaga River at<br />

Medved. SS Totenkopf would remain in corps reserve<br />

under Army Group control. Engineers would continue<br />

building and restoring bridges along the Usa and Shelon<br />

rivers.<br />

The advance toward Shimsk began briskly on 12<br />

July in sunny weather. At Borovichi, Soviet blocking<br />

forces were driven off by 1 st Lt. Fronhoefer’s battlegroup<br />

of 8 th Panzer Division (III /Panzer Regiment 10,<br />

Motorcycle Battalion 8, II/23 rd Flak Battalion), which had<br />

led the advance from Borovichi. It faced increasing<br />

opposition all the way to Sitnya, where it established a<br />

small bridgehead. That night Soviet infantry supported<br />

by tanks counterattacked but were thrown back.<br />

On 13 July, Manstein issued Corps Order #22, calling<br />

for a continued advance toward Novgorod. Fronhoefer<br />

again led. His battlegroup was immediately en-<br />

gaged by Soviet infantry and tanks. At about 3:00 pm<br />

Fronhoefer’s men broke through after destroying over<br />

40 tanks. They rolled forward and reached the railroad<br />

line just west of Soltsy. From there a motorized battalion<br />

reinforced with tanks drove swiftly east, then<br />

stopped for the night.<br />

Meanwhile, the rest of Fronhoefer’s group reached<br />

the western edge of Soltsy. There they drove back the<br />

Soviet 682 nd Motorized Rifle Regiment (of the 202 nd<br />

Motorized Division). The 645 th Rifle Regiment counterattacked<br />

and a Red Army bayonet charge threw the<br />

Germans back five kilometers. Later that evening the<br />

Germans attacked again and secured Soltsy along with<br />

a large quantity of supplies. Soviet supplies were, however,<br />

notoriously incompatible with German needs.<br />

On 14 July, 8 th Panzer Division continued along the<br />

north bank of the Shelon River. A German forward detachment<br />

got as far as the Mshaga River near Shimsk,<br />

but found the bridge there already blown. Manstein’s<br />

flanks were wide open, 40 kilometers to the left and 70<br />

kilometers to the right he had to detach units to screen<br />

them. 8 th Panzer Division was spread over 70 kilometers.<br />

The Battlefield<br />

The Soviet Union often presents a picture of open steppe and endless fields of grain, but northern Russia, including the Novgorod<br />

region (the area of this battle), is covered by vast woodlands and dense thickets, with numerous swamps interspersed. To the German<br />

soldiers it was a gloomy primeval forest. Around Lake Ilmen, the terrain blocked offensive operations except along the few cleared areas.<br />

Roads were poor to abysmal, were poorly mapped, and generally followed the river lines. They led through sand, bog, forest and swamp<br />

and favored the defense at every turn. Some soggy roads may never before have seen the passing of a motorized vehicle.<br />

Rivers could be the best-defined lines for advance since they were on the maps and were generally free of dense foliage. Because of<br />

the time and resources needed for engineers to build pontoons, the Germans tried their best to seize bridges by quick raids.<br />

Woodlands presented special tactical problems. Both sides had difficulty getting their heavy guns off the roads. Once deployed, the<br />

artillery found targets hard to pinpoint. Area fire could be effective, but it required many forward observers. Telephone landlines were<br />

impractical, and radios were in short supply in the Red Army. Once a target was identified, special fuses were required or most blast effects<br />

were lost in the mud. And the defenders found it difficult to entrench in the marshes.<br />

During 1941, German formations at all levels tended to bypass forests and swamps. Mechanized divisions occupied the roads and<br />

sought to fight in open terrain. Generally, that forced defending<br />

Soviet infantry to retreat into the depths of the forests. German<br />

infantry would pursue no farther than necessary to protect<br />

the Rollbahn (the main German supply routes), and that actually<br />

suited Soviet tactics. Soviet units sometimes took bear trails, following<br />

Suvorov’s principle: “Where [even] the deer does not go,<br />

there the Russian soldier will go.” That played into the Red Army<br />

strengths of concealment, ambush, preference for close-in fighting,<br />

and adaptability to the elements. Later in the war many of<br />

the by-passed formations would plague the Germans’ supply lines<br />

with guerilla warfare.<br />

It wasn’t as if the Germans lacked intelligence about the<br />

region. Many repatriated Volksdeutsch and Baltic refugees were<br />

available to give detailed information. Air reconnaissance was<br />

plentiful, and numerous German officers had served in the Baltic<br />

region during the First World War and in the Freikorps campaigns<br />

following. Even clandestine intelligence agents provided information.<br />

Yet German military intelligence casually disregarded much<br />

of it and processed little of the remainder. So the Wehrmacht was<br />

fighting in an ever-increasing fog of war.<br />

Into the east: Motorized columns clog the roads.

The German plan called for 3rd Motorized Division<br />

to cover the corps’ northern flank, but that unit was<br />

experiencing its own difficulties. The road system was<br />

composed largely of narrow dirt paths cutting through<br />

swamps with few bridges. A detachment under 1st Lt.<br />

Feldkeller managed to push its way forward, but ran<br />

into an aggressive Soviet defense. The time was ripe<br />

for a counterattack.<br />

Counterstroke<br />

Soviet reconnaissance had established that the road<br />

along the Shelon River was choked with columns of<br />

German tanks and other vehicles. In the Soviet view<br />

the arrogance of the “Hitlerites” was such that they<br />

neglected the security of their flanks and rear. Eleventh<br />

Army staff quickly came to the conclusion the<br />

situation was favorable for launching a counterblow,<br />

where a gap of 100 kilometers had formed between<br />

the 41st and 56th Motorized Corps. The catalyst, how-<br />

ever, was a message sent on 10 July from G.K. Zhukov<br />

of the Supreme High Command in Moscow. Zhukov<br />

severely criticized 11 th Army for failure to launch a<br />

major counterattack and hinted of the consequences of<br />

continued inaction.<br />

With that inducement, the Soviet Northwestern<br />

Front commander, Gen. Maj. P.P. Sobennikov, decided<br />

to exploit the developing gap between the enemy<br />

corps. [The Northwestern Front was a subordinate<br />

formation of the Northwestern Direction. ed.] He had<br />

two primary objectives: disrupting the German offensive<br />

toward Novgorod and smashing the 56 Motorized<br />

Corps. Voroshilov formalized the arrangement by<br />

directing 11 th Army to make strikes from converging<br />

directions to encircle and destroy the enemy. Units of<br />

11 th Army regrouped into northern and southern operational<br />

groups.<br />

continued on page 14<br />

strategy & tactics 11

12 #232<br />

The Armies<br />

The Red Army<br />

The June 22 nd 1941 German invasion of the USSR caught<br />

the Soviet Union’s “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army” at<br />

the worst possible time. It was still recovering from Stalin’s<br />

purges, in which thousands of officers at all levels of command<br />

were executed or exiled, effectively decapitating<br />

much of the Red Army. Soviet armies resembled their Western<br />

counterparts on paper, with corps controlling divisions<br />

and a plethora of support units the purge, however, as well<br />

as casualties, made it impossible to maintain that structure,<br />

so by the end of the year the Soviets eliminated the corps<br />

headquarters and made the divisions directly responsible to<br />

the army commander. In the field, units were often combined<br />

as “operational groups” for specific missions. That was an<br />

expedient, and it more or less worked until the Red Army<br />

could recover. At higher echelons, the armies were grouped<br />

into “fronts” (army groups) and those into “directions.”<br />

Then there was the reorganization of Soviet armor. During<br />

the 1930s, the Red Army had pioneered mobile warfare,<br />

creating mechanized corps of two tank and one motorized<br />

infantry division each. Those units had much potential, but<br />

the experience of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) caused<br />

the Soviet command to believe large-scale mechanized warfare<br />

would not work. So they broke up the tank divisions<br />

into independent brigades that were supposed to be used as<br />

infantry support units. Then, prior to the German invasion,<br />

the Red Army reformed the mechanized divisions and corps.<br />

All of which led to confusion. Units lacked combined arms<br />

training, logistics were poor, and staffs ranged from inexperienced<br />

to non-existent; however, the Soviets had many<br />

excellent tanks coming off the assembly lines, such as the<br />

T-34.<br />

The Soviet air force was intended to be a direct support<br />

force. Air divisions were assigned directly to fronts and<br />

armies. Despite large numbers of aircraft, the Red air force<br />

performed poorly in the first year of the war. That was due to<br />

a lack of trained pilots, poor logistics, bad command control,<br />

and a general dispersion of effort.

The Germans<br />

German panzer groups were independent<br />

mobile units. Unlike the numbered<br />

armies, the panzer groups were not<br />

supposed to be used to hold sectors of the<br />

front, but instead were employed as operational<br />

forces to gain the decision. In<br />

the 1941 campaign, they were frequently<br />

switched across the Eastern Front to exploit<br />

opportunities. As a result, the Germans<br />

made some incredible advances, but<br />

at the cost of wear and tear on the vehicles<br />

and men. Among other things, German tank replacement was minimal<br />

in 1941, as Hitler wanted to use new production to build up<br />

reserves rather than committing tanks piecemeal at the front.<br />

The panzer groups were initially composed of motorized corps<br />

(later redesignated panzer corps), each with several panzer (armored)<br />

and motorized divisions. As the war progressed, the panzer<br />

groups were redesignated panzer armies and ended up holding sectors<br />

of the front. They also received considerable infusions of nonmotorized<br />

formations, with a corresponding decline in mobility. A<br />

major German dilemma, which was never resolved during the war,<br />

was their lack of strategic reserves. Crises had to be met by switching<br />

divisions across the theater of operations or pulling units from<br />

other fronts.<br />

The Luftwaffe in 1941 was still at the highpoint of its effectiveness.<br />

Its operational air doctrine and high state of training allowed<br />

it to concentrate anywhere on the front. The Luftwaffe was<br />

an integral part of the blitzkrieg, striking deep into the enemy rear<br />

and covering deep-ranging panzer columns. But its strength was<br />

frequently dissipated when used as a “fire brigade,” bailing out<br />

ground forces with close support and air supply.<br />

strategy & tactics 13

14 #232<br />

Reinforcements were already moving into the Luga<br />

Line and some were transferred to 11 th Army: Col. L.V.<br />

Bunin’s 21 st Tank Division, Gen. Maj. A.Y. Fedyunin’s<br />

70 th “Order of Lenin” Rifle Division, and Col. V.Y.<br />

Tishinsky’s 237 th Rifle Division were all allocated to<br />

the Northern Operational Group. Those divisions were<br />

facing the Germans for the first time, though the 70 th<br />

at least had the experience of fighting the Finns in the<br />

1939-40 Winter War. The Soviets were gambling, as<br />

the overall correlation of forces was only marginally<br />

favorable. They had insufficient armor and Red Army<br />

tactics left something to be desired at that time in the<br />

war, but they would enjoy a high degree of surprise in<br />

a favorable battlefield position.<br />

The counterstroke at Soltsy began on 14 July with<br />

subsidiary moves to set the trap. The Northern Operational<br />

Group, built around the headquarters of the<br />

newly arrived 16 Rifle Corps, attacked from the line<br />

Gorodishche-Utorgosh with two divisions toward Sitnya<br />

and with one toward Soltsy. The Southern Group<br />

was built around Gen. Maj. A.S. Ksenofontov’s 22 nd<br />

Rifle Corps (formed in Estonia of 180 th and 182 nd<br />

Rifle Divisions), and included the remnants of 202 nd<br />

Motorized Division plus the recently reformed 183 rd<br />

Rifle Division. It deployed facing the exposed German<br />

southern flank for a push north to Sitnya. The plan was<br />

Waiting for the Soviets: German antitank gun crew.<br />

for the groups to launch converging thrusts to encircle<br />

and destroy enemy forces. In the skies above, Soviet<br />

aircraft would provide direct support.<br />

At 3:00 am on the 15 th , the following radio message<br />

arrived at 4 th Panzer Group headquarters: “Rear area<br />

services of 8 th Panzer Division, three kilometers east<br />

of Borovichi, are defending against enemy attack with<br />

machineguns and mortars.”<br />

Throughout the 15 th , similar reports were received<br />

at German command posts. The Soviets had launched<br />

a powerful attack from the north into the flank of 8 th<br />

Panzer Division, and simultaneously from the south<br />

over the Shelon. That meant the bulk of 8 th Panzer’s<br />

combat units, being located between Soltsy and the<br />

Mshaga, were cut off from the division’s rear echelons.<br />

Further, the Red Army had pushed up forces from the<br />

south to close the German supply route. At the same<br />

time, advance elements of the 3 rd Motorized Division<br />

came under renewed attack by the 237 th Rifle Division<br />

at Maloye Utorgosh. In hard fighting, the 3 rd ’s troops<br />

repulsed seven Soviet attacks, some in hand-to-hand<br />

fighting.<br />

Forming the hammer of the Soviet drive was 70 th<br />

Rifle Division, which enjoyed a favorable local ratio<br />

of force. By 6:00 am on 15 July all of the 70 th ’s

Comparative Unit Strengths, 1941<br />

Manpower AFV MG Mortars AA DF Guns Artillery MT<br />

German<br />

Panzer ‘41 division 15,600 165 1,067 30 74 75 70 2900<br />

Motorized division 16,400 821 712 93 28 71 38 2800<br />

Infantry division<br />

Soviet<br />

17,200 3 643 142 11 79 70 942<br />

Tank division 10,940 475 ? 852 (2) (2) (2) ?<br />

Motorized division 11,600 326 ? 1582 (2) (2) (2) ?<br />

Infantry division, May ‘41 14,400 293 491 150 4 69 32 685<br />

Infantry division, July ‘41 10,700 - 279 78 6 34 8 249<br />

Manpower = full strength<br />

AFV = total armored fighting vehicles, tanks, assault guns; includes armored cars and half tracks in certain units<br />

MG = machineguns; includes anti-aircraft machineguns and vehicle-mounted weapons<br />

Mortars = total mortars<br />

AA = anti-aircraft guns, 20mm and larger; multi-barreled weapons count each barrel<br />

DF Guns = all artillery direct fire weapons and antitank guns larger than 20mm; includes some self-propelled pieces<br />

Artillery = all howitzers and multiple rocket launchers; includes some self-propelled pieces<br />

MT = motor transport vehicles<br />

Notes<br />

1) This number is cited in several sources, but seems to assume the attachment of a tank or assault gun battalion to the division.<br />

The number of organic AFVs was probably 20-30.<br />

2) Total all “guns,” weapons 45mm and greater (except 50mm mortars).<br />

3) In some divisions, 16 light tanks and 13 armored cars.<br />

Note: the diagram of the German 56 th Motorized Corps includes the 290 th Infantry Division, which was detached prior to the<br />

operations described in this article.<br />

units were in position. A last minute reconnaissance<br />

led to the 68th Rifle Regiment going around Soltsy to<br />

put it into position to cut off 8th Panzer Division. Detecting<br />

that movement, a German battlegroup of two<br />

battalions of motorized infantry supported by tanks,<br />

immediately attacked and penetrated into the 68th ’s defensive<br />

zone. But suddenly the German column found<br />

its own rear and flanks under attack. According to the<br />

Soviet account, the Germans panicked, leaving behind<br />

15 destroyed tanks and 200 dead and wounded.<br />

With the preliminaries out of the way, the Soviet attack<br />

developed in its full fury, with 8th Panzer Division<br />

standing alone against 3rd and 21st Tank Divisions, 22nd ,<br />

52nd , and 80th Rifle Divisions, and 22nd Rifle Corps,<br />

consisting of 180th , 182nd and 183rd Rifle Divisions,<br />

and the 202nd Motorized Division. The battle raged<br />

west to Borovichi as the Soviets crossed the Shelon<br />

River and thrust from the north with the 70th and 237th Rifle Divisions and parts of 21st Tank Division.<br />

By late in the day, 8th Panzer Division had divided<br />

into three battlegroups:<br />

• the Shelon sector under Oberst Scheller ( Infantry<br />

Regiment 8, I and III/Panzer Regiment 10, II/Artillery<br />

Regiment 61, Recon Battalion 59, II/Nebelwerfer Regi-<br />

ment 52, 8<br />

strategy & tactics 15<br />

th Panzer Regiment);<br />

• the railroad bridge sector under Maj. Schmid ( Antitank<br />

Battalion 43, Pioneer Battalion 59, Flak Battalion<br />

92, minor units, 8th Panzer Regiment);<br />

• and well forward along the Shelon River a battlegroup<br />

under 1st Lt. Crisolli (II/ Panzer Regiment 10,<br />

Infantry Regiment 28, II and III/Artillery Regiment 80,<br />

II/Flak 23, minor units of the 8th Panzer Regiment).<br />

Scheller found himself under heavy attack with reports<br />

of the Soviets at the edge of Soltsy. From above,<br />

Soviet aircraft attacked road-bound columns. By midday<br />

panic had set in with some German units. That<br />

evening, Red Army infantry was entering Soltsy but,<br />

since it was starting to rain, at least the Soviet aircraft<br />

were grounded. For the night, the battlegroups of 8th Panzer Division organized an all-round defense.<br />

The next day, 16 July, 8th Panzer Division fought<br />

while fully surrounded. Early that morning it withdrew<br />

from most of Soltsy and established its main defense<br />

line along the road west of the north-south railroad.<br />

A battle still raged over Soltsy airfield where German<br />

tanks came under direct fire from enemy anti-tank and<br />

artillery batteries. German motorized units attacked<br />

twice but were thrown back. Red Army pressure on

16 #232<br />

the German flanks threw the defense into confusion as<br />

room to reorganize simply was not there. The Soviet<br />

Northern Group, in particular 70 th Rifle Division, attacked<br />

again and at times fighting was hand-to-hand.<br />

After 16 hours of hard fighting, 8 th Panzer Division<br />

was on the verge of defeat, cut off from its path of<br />

retreat. The Soviets also succeeded in penetrating between<br />

the 56 th Corps’ divisions. Late in the day the<br />

Germans evacuated their last footholds in Soltsy.<br />

Meanwhile, 3 rd Motorized Division reported it was still<br />

under heavy attack.<br />

The Luftwaffe made a showing on the 16 th despite<br />

difficult flying weather. German bombers struck Soviet<br />

railheads and engaged Red Army columns. Destroyer<br />

Group 26 also made an impact with its Bf-110<br />

fighter-bombers, whose pilots were trained in close air<br />

support of ground forces.<br />

But the Soviet air force was also busy, attacking<br />

day and night with four aviation divisions and the 1 st<br />

Long Range Bomber Corps, in all about 235 aircraft.<br />

A particularly successful raid occurred on the night of<br />

15-16 July when the 4 th Composite Aviation Division<br />

of Col. I.K. Samokhin attacked a concentration of German<br />

tanks. In five days of action (14-18 July), the Soviets<br />

conducted about 1,500 sorties in the Soltsy area,<br />

compared to about 960 German, the latter spread out<br />

over the entire Luga front. Soviet bombers included<br />

bridges in their target list, forcing the Germans to deploy<br />

anti-aircraft units at each—and the 88mm highvelocity,<br />

dual-purpose guns were needed to counter<br />

Soviet armor.<br />

Soviet bombing accuracy was poor and the Germans<br />

generally held the initiative in the air. The Soviets<br />

usually came off the worse in air-to-air action<br />

because their aircraft were nearly all obsolescent and<br />

their pilots poorly trained. Yet air losses were not great<br />

for either side. The Luftwaffe was overstretched, try-<br />

Red eagles: Soviet aircraft in a makeshift field.<br />

ing to meet too many requirements across an expanding<br />

front.<br />

Southern Thrust<br />

The Soviet Southern Operations Group enjoyed<br />

success on the 16th , at least at first. On the far left<br />

Col. I.I. Kuryshev’s 182 Rifle Division had attacked<br />

Porchov on the 15th , taking the eastern part of the city<br />

and beginning to encircle the rest. Like the rest of the<br />

Southern Group, that division was too weak, and by<br />

the evening of the 17th it had been driven well back<br />

along the road to Dno with German mechanized units<br />

pursuing. During the 18th the division fell apart and its<br />

command was taken over by Col. M.S. Nazarov.<br />

Col. S.I. Karapetyan’s 183rd Rifle Division covered<br />

the center-left flank of 22nd Corps operations. Over<br />

a three-day period the division continually attacked<br />

German columns retreating to the west toward Borovichi.<br />

Early morning 16 July, units of the 183rd Rifle<br />

Division forced the Shelon River with a surprise attack<br />

and crossed the Novgorod road. The attack succeeded<br />

in demolishing a German column.<br />

During that engagement, an important role was<br />

played by artillerymen of the 624th Howitzer Artillery<br />

Regiment, led by Capt. Y. Leninis. According to the<br />

Soviet account, he gathered all the guns on hand in the<br />

division into one group, which with accurate fire inflicted<br />

heavy losses on the Germans. The Germans retreated<br />

in disorder and the road along the Shelon filled<br />

with burning German equipment.<br />

Prominent on the German side in this fighting was<br />

the 1st Munitions Column bringing forward ammunition<br />

in spite of enemy artillery fire. The Germans reported<br />

a total of 60 vehicles lost. The 183rd Rifle Division<br />

was unable to follow up on its success, and a<br />

request for reinforcements brought only a commission<br />

to count captured equipment. The Germans responded<br />

to that attack by sending up a battalion of the SS Totenkopf,<br />

a motorized infantry battalion from 3rd Motorized<br />

Division, the 48th Pioneer Battalion, and a company of<br />

tanks. Those units managed to stop the Soviets at the<br />

river line from Borovichi to Ilemno.<br />

The 3rd Tank Division’s 5th Tank Regiment fought<br />

actively in the area of Dolzhitsy, Gorushka and Sukhlovo<br />

under the command of Maj. G.I. Segeda on the 17th .<br />

The tankers claimed they encircled and destroyed an<br />

enemy force composed of up to 240 motor vehicles<br />

loaded with ammunition and fuel. That was likely the<br />

German group that had pulled out of Soltsy the prior<br />

evening.<br />

Seven vehicles were captured, one of which contained<br />

chemical shells. Also captured were secret<br />

documents of the German General Staff concerning<br />

preparations for the utilization of poison gas in the war<br />

against the Soviet Union (which, were never carried<br />

out). That was a politically difficult loss for the Germans.<br />

As soon as OKH found out, they requested a full

German vs. Soviet Armored Fighting Vehicles, 1941<br />

German Type Gun MGs Weight Armor Speed HP/Wt Crew<br />

PzKw Ib tank - 2 6.6 tons 13mm 40k/h 15 2<br />

PzKw IIf tank 20/55 1 9.5 tons 35mm 40k/h 12.8 3<br />

PzKw IIIe tank 50/42 2 19.5 tons 50mm 40k/h 12.8 5<br />

PzKw IVe tank 75/24 2 23 tons 45mm 42k/h 13.0 5<br />

PzKw 38(t) tank 37/40 2 9.7 tons 25mm 42k/h 12.9 4<br />

StuG IIIb AG 75/24 - 22 tons 50mm 40k/h 14.9 4<br />

Sd Kfz 231 AC 20/55 1 8.2 tons 14.5mm 85k/h 18.3 4<br />

Sd Kfz 251/1 APC - 1 8.5 tons 12mm 50k/h 13.0 12 1<br />

Soviet Type Gun MGs Weight Armor Speed HP/Wt Crew<br />

BT-7 tank 45/46 2 13.8 tons 20mm 58k/h 32.6 3<br />

KV-1A tank 76.2/30 3 47.5 tons 100mm 35k/h 11.9 5<br />

T-26b tank 45/46 2 9.5 tons 20mm 30k/h 9.5 3<br />

T-28c tank 76.2/26 3 32 tons 55mm ? 15.6 6<br />

T-34/76a tank 76.2/30 1 28.2 tons 60mm 50k/h 9.1 4<br />

T-35 tank 76.2/30 2 5 45 tons 30mm 29k/h 11.1 10<br />

T-60a tank 20/50 1 6.4 tons 50mm 49k/h 13.3 2<br />

SMK tank 76.2/30 3 3 58 tons 60mm 24k/h 8.6 7<br />

BA-10 AC 45mm 1 5.2 tons 15mm 56k/h 16.3 4<br />

Notes<br />

Gun = main gun bore width in millimeters/length<br />

of gun in terms of number of calibers (that is, multiple<br />

of the bore width)<br />

MGs = number of machineguns<br />

Weight = weight when combat loaded<br />

Armor = maximum in millimeters (usually frontal)<br />

Speed = maximum road speed in kilometers per hour<br />

HP/Wt = horsepower/weight (tons) ratio, a measure<br />

of the vehicles maneuverability<br />

Crew = normal operating crew<br />

Type AC = armored car; AG = Assault gun; APC =<br />

Armored personnel carrier<br />

1) Includes transported infantry<br />

2) The T-35 also had 2 x 45mm guns mounted in<br />

separate turrets.<br />

3) The SMK also had 1 x 45mm gun mounted in a<br />

separate turret.<br />

Red armor rolls.<br />

strategy & tactics 17

18 #232<br />

report from Manstein about the loss of those top-secret<br />

documents.<br />

At the center of Soviet 22 Corps Col. I.I. Missan’s<br />

180th Rifle Division began the offensive a bit later.<br />

Moving in a northerly direction from Dno, it advanced<br />

25 kilometers to reach the Shelon River. There it joined<br />

the attack in progress and took its share of prisoners<br />

and equipment.<br />

The Germans fought desperately to break out of the<br />

encirclement. From 15 to 16 July, the 202nd Motorized<br />

Division claimed it destroyed more than 100 enemy<br />

trucks, around 50 tanks, and a great number of personnel.<br />

Turning Point<br />

On 17 July the Germans undertook urgent efforts<br />

to rescue their troops. SS Totenkopf was released from<br />

army group reserves and entered the Sitnya battle. One<br />

battalion helped 3rd Motorized Division smash a series<br />

of Soviet armored and infantry attacks at the village of<br />

Baranovo. All told, 3rd Motorized Division repelled 17<br />

attacks that day, a good measure of how Soviet battle<br />

coordination was breaking down. With the approach<br />

of Totenkopf, 8th Panzer Division concluded its breakout<br />

to the west. It completed its move out of the front<br />

line on the 18th and went into reserve.<br />

By 18 July the crisis was over. The 56th Motorized<br />

Corps was firmly established east of Sitnya on a line<br />

Dubrovo-Baranovo, generally facing east by northeast,<br />

and still pressed by attacks from 70th Rifle Division.<br />

The earlier danger to the southern flank was<br />

removed as 1st Corps (11th and 21st Infantry Divisions)<br />

moved up in support. With the 182nd Rifle Division<br />

breaking, and the 183rd Rifle Division almost caught<br />

in an encirclement, the Red Army was running out<br />

of steam. But the Soviets were not yet finished. They<br />

German infantry walks.<br />

sent in additional forces, among which were elements<br />

of 1st Mechanized Corps. They proved insufficient in<br />

the face of German regimental groups reinforced with<br />

armor. The 5th Motorcycle Regiment found itself surrounded<br />

at one point, but the arriving 202nd Division<br />

restored the situation. On the morning of the 19th , German<br />

troops entered Dno and Soviet troops were in full<br />

retreat. On 20 July the strategic initiative shifted north<br />

of the Shelon, and the Red Army was also retreating<br />

there. The struggle for Soltsy was over.<br />

Endgame<br />

Soltsy was one of the most outstanding Soviet<br />

counterblows in the first months of BARBAROSSA. It<br />

played an important role in slowing the pace of Army<br />

Group North’s drive toward Leningrad and Novgorod.<br />

The Red Army had won valuable time for the organization<br />

of the defense of Leningrad and the arrival<br />

of reserves, and for the improvement of combat skills<br />

and morale.<br />

Still, the Red Army derived no operational lessons<br />

from the battle. There was little in the way of coordination<br />

between the converging columns. Overall command<br />

and control was poor. Essentially, the operation<br />

devolved into a series of attacks in which each division<br />

attacked on making contact with the Germans.<br />

There was also little coordination between neighboring<br />

units. Casualties in the assault waves could be up<br />

to 50%, and most divisions burned out quickly. No<br />

Soviet casualty figures are available for the Battle of<br />

Soltsy but the casualties could not have been any less<br />

than that typical elsewhere. As an example, 70th Rifle<br />

Division entered the battle over-strength with 15,333<br />

men; a month later it recorded only a few hundred<br />

troops still on the roster.<br />

The Soviets credited themselves with inflicting a<br />

defeat on a picked enemy force, throwing the Germans<br />

back 40 kilometers and routing 8th Panzer Division.<br />

Eighth Panzer Division was indeed cut up and out of<br />

action for about a month. Parts of 3rd Motorized Division<br />

and the rear services of the 56th Motorized Corps<br />

also suffered. Overall, Army Group North stopped for<br />

three weeks before renewing its offensive. It was those<br />

weeks that provided enough time to save Leningrad.<br />

German losses were serious but not disastrous.<br />

Some 50 tanks were destroyed or seriously damaged,<br />

and operational armor was reduced to about 100 as<br />

of 20 July. Yet many of the damaged vehicles were<br />

repaired. Troop losses amounted to about 550 killed,<br />

wounded, and missing in 8th Panzer Division, 220 in<br />

the SS Totenkopf Division, and proportionately the<br />

same in 3rd Motorized Division. That was a loss rate<br />

of 110 men per division per day for the period 14 -18<br />

July, which was typical of heavy engagements. Divisional<br />

replacement pools were exhausted and Manstein<br />

considered his divisions to be exhausted. Gen. Paulus,<br />

chief quartermaster of OKH, informed Manstein

on the 26 th that replacements were indeed available—but<br />

they were far back on the road to Germany. Much more<br />

troublesome were the equipment losses in 8 th Panzer Division.<br />

They were high and difficult to replace. Germany<br />

was too short on mobile divisions to have a panzer division<br />

knocked out of action for a month.<br />

Then came the delegation of blame. In his postwar<br />

memoirs, Manstein was critical of Hoepner’s decision to<br />

withdraw the SS Totenkopf Division from the right flank of<br />

his corps after its earlier battles to the south. Manstein had<br />

indeed requested on 14 July a return of SS Totenkopf and<br />

that was refused by Hoepner. It is likely the army group<br />

commander felt he needed at least some reserve for the<br />

attack on Leningrad. Manstein later urged the insertion of<br />

his corps behind that of Reinhardt’s on the lower Luga, but<br />

that was forbidden by Hitler. The Führer even followed up<br />

with a visit to von Leeb’s Headquarters on 21 July, where<br />

he demanded Leningrad be “finished off speedily.”<br />

With the defeat of 56 th Motorized Corps and stalemate<br />

elsewhere along the Luga Line, German forces paused to<br />

gather strength for their next general offensive. Hitler directed<br />

that any farther advance toward Leningrad would<br />

have to wait until the infantry of 16 th Army had secured<br />

the eastern flank of the army group. Later he authorized<br />

units of 3 rd Panzer Group and the whole of 8 th Air Corps to<br />

move north from Army Group Center to assist Leeb in his<br />

renewed offensive, scheduled to begin 8 August. Notably,<br />

plans still included the encirclement of Leningrad from the<br />

southeast, and in the end, that was accomplished if only<br />

by a narrow margin. But Leningrad was never taken.<br />

The objective: Leningrad, with Soviet militia mobilizing.<br />

References<br />

Carell, Paul, Hitler Moves East, New York: Ballantine, 1963.<br />

Dieckhoff, G., 3.Infanterie-Division, Cuxhaven: Erich Borries D.und V.,<br />

1960.<br />

Erickson, John, The Road to Stalingrad, New York: Harper & Row, 1975;<br />

p.182.<br />

Glantz, Col. David M., Forgotten Battles of the German-Soviet War (1941-<br />

1945), Vol.I., self-published, 1999.<br />

Haupt, Werner, Army Group North, the Wehrmacht in Russia 1941 - 1945,<br />

Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1997.<br />

Haupt, Werner, Die 8.Panzer-Division im Zweitenweltkrieg, Freidberg: Podzun-<br />

Pallas- Verlag, 1987Yu.S. Krinov, Horst Boog, et al, Germany and<br />

the Second World War, Vol. IV, Oxford: Clarendon <strong>Press</strong>, 1998; pgs 541-<br />

542.<br />

Kislinsky, V.S., Net nechego dorozhe: Dokumentalnyy ocherk, Leningrad:<br />

Lenizdat, 1983.<br />

Kvaley, S.F., “202-ya strelkovaya diviya I ee komandir S.G. Shtykov,” Ha severo-zapadnomfronte,<br />

1941-1943, Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “Navka,” 1969<br />

Levi, S. (ed), Borba latyshskovo naroda v gody velikoy otechestvennoy<br />

voyny (1941-1945), Riga: Izdatelstvo “Zinatne,” 1970.<br />

Lubey, L. (ed), Borba za sovetskuyu pribaltiky v velikoy otechestvennoy<br />

voyne 1941-45, Book One, Riga: Izdatelstvo “Liyesma,” 1966.<br />

v.Manstein, Eric, Lost Victories, Chicago: Regnery, 1958<br />

Salisbury, Harrison E., The 900 Days, New York, 1969.<br />

Sydnor, Charles W., Soldiers of Destruction, Princeton: Princeton University<br />

<strong>Press</strong>, 1977.<br />

Istoriya ordena Lenina Leningradskogo voyennogo okruga, Moscow: Voyenizdat,<br />

1974.<br />

Luzhskiy rubezh god 1941-y, Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1983.<br />

“Combat in Russian Forests and Swamps,” Dept. of the Army Pamphlet No.20-<br />

231, dated July 1951; and “Terrain Factors in the Russian Campaign,” Dept.<br />

of the Army Pamphlet No.20-290, dated July 1951.<br />

strategy & tactics 19

20 #232<br />

C<strong>AT</strong>HERINE THE GRE<strong>AT</strong>:<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> in the Age of Enlightenment<br />

by Joseph Miranda<br />

The Age of Enlightenment, roughly the period from the<br />

Treaty of Westphalia (1648) to the outbreak of the wars of<br />

the French Revolution (1791), was characterized by strategic<br />

parameters that led to a formalistic style of warfare. Military<br />

objectives were limited by the necessity to maintain the balance<br />

of power. Yet despite the formalism, a power operating outside<br />

the mainstream of Europe was able to build a continent<br />

spanning empire—that was Russia.

War and Society<br />

The Treaty of Westphalia brought to an end the<br />

Thirty Years War (1618-48). That war had originally<br />

started as another round in what was becoming a seemingly<br />

endless series of religious conflicts in Europe,<br />

triggered by the rise of Protestantism in the early 16 th<br />

century. The issues Protestantism raised went beyond<br />

religion and included fundamental political disputes.<br />

Since the rise of the Carolingian Empire in the 8 th century<br />

AD, the European ideal was to form a united state<br />

ruling over the entire continent. The Holy Roman Empire<br />

was an attempt to bring about this universal state.<br />

The Holy Roman Empire, as wits frequently described<br />

it, was neither “holy,” nor “Roman,” nor much of an<br />

“empire.” Not since the Dark Ages had even the city<br />

of Rome been included within the empire’s boundaries<br />

and, in fact, the papacy frequently fought against various<br />

emperors, the latter coming from various German<br />

houses.<br />

By the 17 th century, the Holy Roman Empire was<br />

little more than a collection of states in central Europe,<br />

loosely organized around a fragmented Germany with<br />

the capital in Vienna and the throne in the hands of<br />

the Habsburg family. Challenging the empire, not<br />

merely militarily but ideologically, were the rising<br />

national states of Europe The protestant churches of<br />

Sweden and England, since they did not acknowledge<br />

the supremacy of the papacy in Rome, provided an<br />

ideological counterbalance to the centralizing and universal<br />

appeal of “empire.” And even Catholic France<br />

frequently put its national aspirations higher than any<br />

pan-Catholic or even Christian interests, frequently allying<br />

itself with the Moslem Ottoman Empire.<br />

All that came to a head with the Thirty Years War,<br />

which initially pitted Catholic Austria and Spain (representing<br />

the empire) against Protestant German states<br />

and then Denmark and Sweden. But the nature of<br />

the conflict changed with the intervention of France<br />

against the empire. French national interests demanded<br />

Europe not be consolidated under a single great<br />

empire. The war came to an end with the aforementioned<br />

Treaty of Westphalia. While the treaty did not<br />

end warfare in Europe, it did fundamentally change its<br />

nature.<br />

The Thirty Years War was fought with unprecedented<br />

disregard for the civilian populace, with pillaging<br />

and devastation a normal part of operations.<br />

Aside from the moral issues, the destruction of crops<br />

and cities undermined the civilian economies. That, in<br />

turn, undermined the power of the governments to collect<br />

taxes and maintain order. The European governments<br />

decided it was time to restrain their armies and<br />

minimize the destruction. It wasn’t simply a matter of<br />

altruism, but also of self-preservation. Out of control<br />

armies were as much a threat to the kings and princes<br />

as they were to the citizenry. For example, Albrecht<br />

Wallenstein, the imperial warlord of the Thirty Years<br />

War, had amassed more power than the Hapsburgs and<br />

might have set himself up as emperor were it not for<br />

his assassination in 1634<br />

There was also the growing professionalization of<br />

the armies. Up until the mid-17 th century, recruiting<br />

was a haphazard affair. Soldiers were drawn from mercenaries,<br />

quasi-professional regulars, and remnants of<br />

feudal levies. Countries such as Sweden showed that<br />

a regular military with a professional officer corps<br />

was the way of the future. A regular army had the advantages<br />

of superior discipline and training. Recruits<br />

needed to be exercised in the drills required to employ<br />

the complex tactics of the day. Officers were drawn<br />

from the nobility, and that had the added benefit of<br />

putting them to some good use.<br />

Politically, the states of Europe were becoming<br />

more centralized. Feudal relationships were disintegrating<br />

and being replaced by central government administrations<br />

with taxation and nation-wide laws. That<br />

meant governments could mobilize far more strength<br />

than they could in the past, and did not waste time and<br />

resources in civil war. All that was backed by new ideologies<br />

that justified centralized rule: the divine rights<br />

of kings as well as Hobbes’s Leviathan.<br />

With well disciplined armies and centralized states,<br />

the European governments had instruments with<br />

which they could conduct warfare as if it were a game<br />

of chess. And, not incidentally the army could be used<br />

to maintain the monarch’s power by suppressing any<br />

rebels.<br />

In a sense, what the Treaty of Westphalia recognized<br />

was that among European monarchs there was<br />

no issue worth mutual self-destruction. By limiting<br />

conflict to disputes over the balance of power all states<br />

could be assured of their continual existence. Yet the<br />

Age of Enlightenment was also an age of war—even<br />

if limited. But the wars were fought not to conquer<br />

entire countries or to establish a European-wide polity.<br />

For the most part, they were “civilized” affairs that<br />

resulted in the acquisition or loss of a border province<br />

or two.<br />

Balance of Power<br />

The central feature of both war and international<br />

politics in this era was the balance of power. Simply<br />

put, the balance ensured no one European state became<br />

strong enough to dominate the entire continent. Effectively,<br />

that meant the old ideal of empire was dead.<br />

Each state would keep its integrity and, while borders<br />

might fluctuate, only minor gains and losses of territory<br />

would be allowed. Even a monarch as powerful as<br />

Louis XIV of France (1643-1715) proved incapable of<br />

defeating the balance. In the War of the Spanish Succession<br />

(1701-14), his attempts to set a relative on the<br />

throne of Spain led to a European coalition marching<br />

against him. Ironically, what saved him in the end was<br />

strategy & tactics 21

22 #232<br />

the same balance. The other European states saw Britain<br />

as becoming too powerful, and so withdrew from<br />

the anti-French coalition.<br />

Consequently, military operations tended to be<br />

conducted with an eye toward the postwar settlement.<br />

What was gained on the battlefield could be traded for<br />

advantages at the peace talks, and even the loser might<br />

come home with something. For example, during the<br />

Seven Years War, a French objective was conquering<br />

the kingdom of Hanover in Germany. The reason was<br />

the British monarchy had strong links to Hanover, and<br />

Paris could hope to trade any of Hanover’s territory<br />

that French armies seized for, perhaps, the return of<br />

French colonial possession in America or India that<br />

had been conquered by the British. Similarly, the Russians’<br />

gains in their 1787-92 war against the Ottomans<br />

were largely given back to the Turks owing to the pressures<br />

other European capitals put on St. Petersburg.<br />

While there may have been little love for the Ottoman<br />

Empire in Europe, there was even less desire to see a<br />

powerful Russia dominating the east.<br />

All that underscored a more fundamental dilemma:<br />

how did one actually conquer a country in the 18 th century?<br />

Charles XII of Sweden tried. In the Great Northern<br />

War (1700-21), he led a Swedish army deep into<br />

Russia. While he won some initial victories, they led<br />

nowhere strategically because his foe, Russian Emperor<br />

Peter I (the Great) refused to capitulate. And Peter<br />

had plenty of room into which he could retreat, given<br />

the expanse of his empire. So the Swedes plunged<br />

deeper into Russia, finally marching into the Ukraine<br />

to link up with Cossacks who were in rebellion against<br />

St. Petersburg. Charles finally attacked Peter at the<br />

epic Battle of Poltava (28 June 1709), and went down<br />

to defeat. The Swedish army was largely annihilated,<br />

and only after much difficulty did Charles make it<br />

home. Poltava is one of the decisive battles of European<br />

history insofar as it ended Swedish supremacy in<br />

northern Europe and also brought the emerging Russian<br />

Empire to the forefront as a great power.<br />

The Swedes had been out of their depth from the<br />

start of the Great Northern War. Swedish power was<br />

based on the Baltic, with the Swedish Empire including<br />

not only the homeland but also Finland, Pomerania<br />

in northern Germany, and the Baltic states. Swedish<br />

naval domination of the Baltic gave them interior lines<br />

of communication. Effectively, they could reinforce<br />

any part of their empire by sea. Economically, Baltic<br />

trade gave them the wealth to maintain the empire and<br />

also consolidate political relationships with the littoral.<br />

By moving deep inland in Russia, Charles was cutting<br />

himself off from his economic and military base. Even<br />

if he had somehow managed to defeat Peter at Poltava,<br />

he would have still have faced the overarching<br />

dilemma of actually ruling Russia. The Swedes lacked<br />

both the infrastructure to administer the country and<br />

the army to maintain order internally.

The Rise of Russia<br />

Modern Russia really began with the rise of the<br />

Muscovite state that, until the end of the European<br />

middle ages, was little more than a vassal of the Mongol<br />

Khanate of the Golden Horde. But a powerful vassal<br />

it was and, by the early 16 th century, Moscovy had<br />

largely destroyed the remnants of Mongolian power<br />

west of the Urals. The Russians then continued to expand,<br />

absorbing the ancient states of Novgorod and<br />

Kiev, as well as sweeping deep into Siberia and Central<br />

Asia.<br />

Of course, when dealing with assorted Mongols<br />

and Asian peoples, the Russians had little concern<br />

for balance of power issues. Consequently, conquest<br />

tended to be complete, including extensive colonization<br />

of subjected peoples. In a sense, it was a clash of<br />

civilizations. The Russians were better organized, and<br />

they also had a military advantage. Traditionally, the<br />

peoples of the Asian steppes relied on horse-mobile<br />

armies that were capable of outmaneuvering enemies<br />

both strategically and tactically. But the rise of modern,<br />

disciplined Western armies equipped with gunpowder<br />

weapons returned the tactical ascendancy to the Europeans.<br />

They could easily smash a nomadic army on the<br />

battlefield. Strategically, the Russians used a combination<br />

of forts, military colonies and secured trade routes<br />

to limit the mobility of steppe armies as well as extend<br />

their own rule. Then there were the personality issues:<br />

the rise of Russia took place in the era of such great<br />

leaders as Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, while<br />

the steppe peoples failed to produce another Genghis<br />

Khan or Tamerlane.<br />

The constant eastern warfare gave the Russian military<br />

something of an edge when it came to the practical<br />

aspects of war. Commanders had to be good, or they<br />

would be annihilated. In the 18 th century, the Russian<br />

military proved adept at organizing mobile, combined<br />

arms columns to track down nomad foes. And Russian<br />

commanders such as Alexander Suvarov also became<br />

good at fighting and winning decisive campaigns.<br />

All that underscores the Russian divergence from<br />

contemporary European warfare. The Russians had<br />

a frontier into which to expand. The other European<br />

powers did not, at least not on the continent—hence<br />

their competition for colonies in the Americas and India.<br />

At home, the Europeans were forced into a limited<br />

form of warfare in which diplomacy and mutual preservation<br />

were overriding considerations. The Russians<br />

had more room to maneuver.<br />

Enter Catherine the Great<br />

Catherine, later known as the “Great” (see the sidebar<br />

on biographies), came to power at a unique time in<br />

European history. The year 1762 saw the beginning of<br />

the end of the Seven Years War, which pitted the great<br />

powers against each other both on the continent and<br />

around the world. Britain and Prussia emerged from<br />

the war as the leading powers of Europe, while France<br />

and Austria had their stars eclipsed by battlefield defeat<br />

and financial exhaustion. It was especially bad for<br />

France, which lost its colonies in the New World. [For<br />

more on the Seven Years War, see S&T nr. 231. ed.]<br />

Russia was in a position to assume the mantle of the<br />

primary continental power. And that Catherine did, by<br />

the usual method: war. During her reign (1762-96),<br />

continued on page 26<br />

strategy & tactics 23

24 #232<br />

The Players<br />

Abdulhamid I (1725-1789). Abdulhamid reigned as Sultan of<br />

the Ottoman Empire from 1774 to 1789, an era which saw<br />

Turkish fortunes on the decline. He lost wars to both Austria<br />

and Russia, the former power gaining Bukovina, and the latter<br />

the Crimea (an Ottoman vassal state) as well as a chunk<br />

of the Ukraine. His empire was saved from destruction only<br />

by the intervention of the other European powers, notably<br />

England, Sweden and Prussia, who did not want the Austro-<br />

Russian alliance becoming too powerful.<br />

Abdulhamid saw much of the problem with his empire<br />

was it had long since fallen behind the Europeans in various<br />

ways. He made some attempts to modernize the armed<br />

forces and to restrain the independent warlords, but it was a<br />

matter of too little too late.<br />

Frederick II (1712-86). Frederick, King of Prussia (1740-86) is<br />

generally known by his title, “the Great.” He is also known<br />

for personally commanding the Prussian Army in the War<br />

of the Austrian Secession (1740-44) and the Seven Years<br />

War (1756-63). Those wars resulted in Prussia gaining and<br />

holding the rich province of Silesia. More importantly for<br />

the history of Europe, Frederick established Prussia as the<br />

most important state in Germany and as a major power of<br />

the day.<br />

Frederick built up the Prussian army as a decisive instrument<br />

of warfare, emphasizing the military education of<br />

officers, severe training for the regiments, and the use of<br />