here. - Todd Matthews

here. - Todd Matthews

here. - Todd Matthews

- TAGS

- matthews

- wahmee.com

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

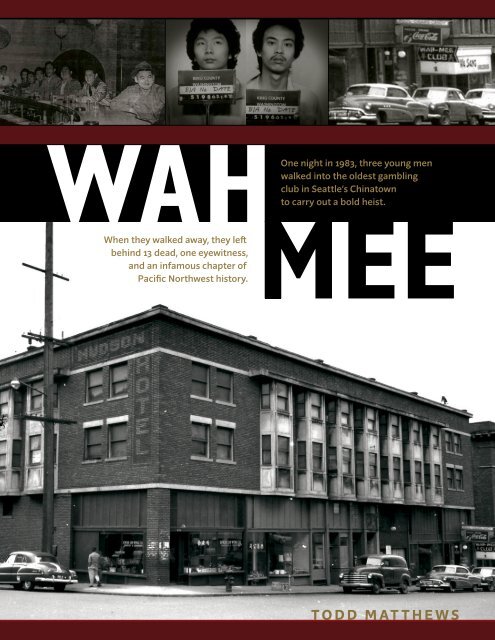

Wah Mee<br />

Copyright © 2011 by <strong>Todd</strong> <strong>Matthews</strong><br />

All Rights Reserved<br />

ISBN 978-0-615-53375-9<br />

This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America.<br />

Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork <strong>here</strong>in is<br />

prohibited without the expressed written permission of the author.<br />

Cover design by John Hubbard/EMKS, Finland<br />

Copyediting and Proofreading by Carrie Wicks<br />

First Edition, August 2011<br />

Second Edition, October 2012<br />

(new e-book cover, additional photographs, formatting changes)<br />

wahmee.com<br />

WAH MEE 2 TODD MATTHEWS

ONE<br />

If you want to know the w<strong>here</strong>abouts of the worst mass murder in the history of<br />

Seattle, visit the city’s Chinatown and listen for the frantic squawks of exotic birds<br />

from the pet store popular with the area’s children. Look for the old Chinese bakery<br />

on South King Street, w<strong>here</strong> pineapple buns, moon cakes, and sponge rolls are<br />

arranged in neat, glistening rows behind a storefront window. Walk along South<br />

King Street — past totems of pagoda-shaped pay phones and exhausted cooks<br />

dressed in greasy chef whites smoking cigarettes during all-too-brief breaks and<br />

surveying the neighborhood; through spacious Hing Hay Park, w<strong>here</strong> seniors<br />

practice Tai Chi most mornings — and turn down Maynard Alley South, w<strong>here</strong> a<br />

bright wind sock stretches high overhead, and seagulls caw at pigeons in a battle<br />

over scraps in the garbage-strewn alley. Oddly enough, nestled among these<br />

seemingly quaint and urban points of interest is the entrance to the Wah Mee Club<br />

— a historic Chinatown gambling club, and site of a dark piece of Pacific Northwest<br />

history.<br />

The Wah Mee Club was tucked away in a ground-floor space of the Nelson,<br />

Tagholm & Jensen Tenement, a hotel built in 1909 by three Scandinavian men who<br />

fled the economic turmoil in their homeland and wound up in Seattle. The hotel,<br />

with its 120 tiny rooms, was a hub for young men (and their prostitutes) en route<br />

to Alaska to seek their fortunes in the Gold Rush.<br />

WAH MEE 3 TODD MATTHEWS

For thirty years, between the 1920s and 1950, the Wah Mee was classy,<br />

cinematically noir, and very popular. “The Wah Mee Club was famous in Seattle,”<br />

writer Frank Chin observed. “You don’t speak with any real authority about Seattle<br />

of the ’30s, ’40s, or ’50s, if you can’t say when you first stepped into the electric,<br />

smoky — Wah Mee.”<br />

Indeed, the club thrived, as did most clubs in Chinatown and along nearby South<br />

Jackson Street. Historian and writer Paul de Barros, in his book on Seattle’s<br />

speakeasies, Jackson Street After Hours, writes, “Imagine a time when Seattle,<br />

which now rolls up its streets at 10 o’clock, was full of people walking up and down<br />

the sidewalk after midnight. When you could buy a newspaper at the corner of 14th<br />

and Yesler from a man called Neversleep — at three in the morning. When<br />

limousines pulled up to the 908 Club all night, disgorging celebrities and wealthy<br />

women wearing diamonds and furs. When ‘Cabdaddy’ stood in front of the Rocking<br />

Chair, ready to hail you a cab — that is, if he knew who you were.”<br />

According to de Barros, the more popular bottle clubs in and around Chinatown<br />

were the New Chinatown, Congo Club, Blue Rose, 411 Club, Ubangi, and the Wah<br />

Mee. All were hot spots for dancing, music, gambling, and booze. Many of these<br />

clubs dated back to the early 1920s. De Barros profiles many of these clubs in his<br />

book.<br />

The New Chinatown was located a few blocks from the Wah Mee, on Sixth<br />

Avenue South and South Main Street. According to de Barros, the club attracted<br />

and promoted much bootlegging. The outside featured a replica neon bowl with two<br />

“chopsticks” poking out from the bowl. Frequented by sailors and prostitutes, the<br />

New Chinatown was known as a place for the occasional brawl. Five bucks bought a<br />

bottle of home brew and an evening of some of the best live music being played in<br />

Seattle during the 1930s. Jazz music was indeed a hit at the New Chinatown; even<br />

the club’s bouncer, a burly and morbidly obese guy named “Big Dave” Henderson,<br />

sat down at the piano most nights.<br />

In 1940, the Congo Club opened in Chinatown, at Maynard and Sixth Avenues.<br />

In the front, the Congo Grill; tucked away past a swinging door, the actual club<br />

WAH MEE 4 TODD MATTHEWS

itself — complete with a ballroom and a circular bar.<br />

The Ubangi Club was a black-owned nightclub hosting some of the nation’s best<br />

jazz performers. The Ubangi — located on the east side of the building w<strong>here</strong> the<br />

Wah Mee was housed — was a huge and beautiful cabaret, w<strong>here</strong> Cab Calloway was<br />

known to perform when in town. The state liquor control board occasionally<br />

targeted the Ubangi. During raids, the club’s manager, Bruce Rowell, would sneak<br />

through the “secret doors” and stairways in the building and exit in the alley near<br />

the Wah Mee. “That’s how I got away from the Washington State liquor board, three<br />

times,” Rowell told de Barros. “Heh-heh-heh! When they came in, I’d go to the<br />

office, see, and say, ‘Let me get my overcoat.’ Then I’d zip down that little deal, you<br />

know, near the floor, and Sheeoop! I’m downstairs in the basement. Next thing I<br />

know, I’m coming out, go down to the Mar Hotel, get a room, take a bath, and go<br />

to bed! They’re all up t<strong>here</strong> lookin’ for me and I’m in the shower!”<br />

Another Chinatown club — formally named the Hong Kong Chinese Society Club<br />

— was located on Seventh Avenue South. Locals aptly nicknamed the club the<br />

“Bucket of Blood” because it was a raucous joint w<strong>here</strong> fights were common. It<br />

earned its nickname after someone was murdered following a police raid.<br />

In many of these Chinatown clubs, guests drank booze, listened to live jazz,<br />

danced, sought prostitutes, and threw down their bets at illicit casinos and on the<br />

daily lottery. The club scene during the 1930s was carefree. As jazzman Marshal<br />

Royal told de Barros, “They were different type of people . . . in Seattle. You had a<br />

lot of fun. They were nice, they were cordial. I’m not just speaking of black people.<br />

I’m talking about the Chinese guys that owned the cab companies and things. They<br />

were our buddies. Everybody was just in it for a family. Like the Mar boys, big-time<br />

tong people out of Fresno, we had a ball. After we finished our job, they would have<br />

a midnight picture at the Atlas Theatre, open all night long. You could go in t<strong>here</strong><br />

and tell the owner what picture you wanted and he’d have it for you two or three<br />

days later.”<br />

The Wah Mee Club fit nicely into this festive environment.<br />

In its earliest years, during the late 1920s, the Wah Mee Club was called the<br />

WAH MEE 5 TODD MATTHEWS

Blue Heaven. As its name implied, it was a decadent place for dancing, drinking,<br />

gambling, and partying. Its regulars had always been a “who’s who” of the Asian<br />

American community. The late John Okada, a Japanese American writer who wrote<br />

the novel No-No Boy, frequented the club. In his novel, Okada describes the<br />

atmosp<strong>here</strong> inside gambling clubs throughout Seattle’s Chinatown:<br />

Inside the door are the tables and the stacks of silver dollars and . . . no<br />

one is smiling or laughing, for one does not do those things when the twenty<br />

has dwindled to a five or the twenty is up to a hundred and the hunger has<br />

been whetted into a mild frenzy by greed.<br />

Okada based his novel’s key gambling club on the Wah Mee — a place he<br />

frequented during the 1940s. In No-No Boy, the Wah Mee is renamed “Club<br />

Oriental”; <strong>here</strong> is Okada’s description of the club:<br />

Halfway down an alley, among the forlorn stairways and innumerable<br />

trash cans, was the entrance to the Club Oriental. It was a bottle club,<br />

supposedly for members only, but its membership consisted of an ever-<br />

growing clientele. Under the guise of a private, licensed club, it opened its<br />

door to almost everyone and rang up hefty profits nightly. Up the corridor,<br />

flanked on both sides by walls of glass brick, they approached the polished<br />

mahogany door. Kenji poked the buzzer and, momentarily, the electric catch<br />

buzzed in return. They stepped from the filthy alley and the cool night into<br />

the Club Oriental with its soft, dim lights, its long curving bar, its deep<br />

carpets, its intimate tables, and its small dance floor.<br />

Another Wah Mee notable was restaurateur Ruby Chow, who would later become<br />

a King County Council member. Chow was easy to recognize at the Wah Mee Club,<br />

at barely five feet tall with a towering French roll. Writer Frank Chin rather<br />

humorously described her trademark hairdo as “the well-gardened and cultivated<br />

WAH MEE 6 TODD MATTHEWS

creation of hair that rises and rises in the shape of a huge popover over her head.<br />

[It] is the largest French roll ever to survive wind and snow, rain and the rest of the<br />

weather.”<br />

During the 1930s, the Wah Mee was open to people of all races. That changed<br />

somewhat a decade later, when Fay Chin and his friend Danny Woo were driving<br />

across the Ballard Bridge en route to the Ballard Elk’s Club to inquire about<br />

chartering an Elk’s Club in Chinatown. The two men instead decided to charter their<br />

own club and Chin ran with the idea. He sold fifty-dollar shares all over Chinatown,<br />

assumed the rent, paid a fee to the city, and took over the Wah Mee.<br />

When Chin and Woo took over, Chinese entered the Wah Mee through an<br />

entrance on South King Street; Caucasians and other races entered the club by way<br />

of the alley. A red sign with the club’s name (in English and Chinese characters) in<br />

neon once hung outside the alley-side entrance. A photograph by Elmer Ogawa, a<br />

freelance photographer and journalist who documented much of Chinatown’s festive<br />

street scene during the period, shows seven young Asian American men gat<strong>here</strong>d<br />

at the Wah Mee’s curvy bar. Everyone is smiling, a drink in front of each patron. A<br />

pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes sits upright among an array of ashtrays. Ornamental<br />

lanterns glow overhead. One young man wears a fedora, while a few others don<br />

leather bomber jackets. At the end of the bar, a waiter dressed in a white suit and<br />

black tie smiles with the customers.<br />

One Wah Mee regular, Windsor Olson, had fond memories of the club. “Back in<br />

the 1940s, my wife and I went to the Wah Mee,” Olson told me one evening not too<br />

long ago. We were sitting in his red minivan, parked in the alley and listening to the<br />

rain tap against the metal roof of the van. We stared through streaked windows at<br />

the club’s dark entryway: two sturdy double doors covered in fresh graffiti and<br />

laced closed with a heavy chain and a padlock.<br />

Olson — an older, well-dressed man who was still dapper in his mid-seventies<br />

and wore a pressed shirt, dark blazer, and slacks — was a retired private<br />

investigator who had snooped around hotels, bottle clubs, and brothels since the<br />

late 1940s. Over the years, he was hired to spy on crooks, keep tabs on unfaithful<br />

WAH MEE 7 TODD MATTHEWS

husbands, and generally tail the city’s undesirables. “I’ll tell you,” Olson<br />

commented, earlier that evening, “I’ll bet I drilled a hole in the wall of every room<br />

at the Edgewater Hotel at one time or another, for cameras and listening devices.”<br />

When I met Olson, he had the clean presence of a distinguished gentleman who<br />

had heard all of Seattle’s dirty secrets — twice — and walked away from them with<br />

a sense of mild interest. Corrupt cops and speakeasies and brothels didn’t shock<br />

Olson; rather, they helped shape Seattle’s history — as had the 1962 World’s Fair or<br />

early Pioneer Square. “I remember,” Olson continued, “t<strong>here</strong> was only one set of<br />

security doors back then. Once someone buzzed you in, t<strong>here</strong> was a three-foot<br />

Buddha on a pedestal just inside the entrance.” He paused to chuckle. “That<br />

Buddha’s belly had been rubbed so many times for good luck.”<br />

T<strong>here</strong> was, of course, gambling when Olson and his wife, Dorie, would visit the<br />

club. “But that was upstairs,” Olson insisted. “Not out in the open on the lower<br />

floor.” Indeed, one researcher reports the hotel rooms above the Wah Mee Club<br />

were demolished around 1940 to make room for a large casino.<br />

“T<strong>here</strong> were bagmen at the Wah Mee,” Olson continued. He was referring to<br />

police officers who looked the other way as long as they received a cut from club<br />

owners. “When I went to the club, the bagman was a cop named Tommy Smith. He<br />

was a drunk. One night, he comes into the Wah Mee, drunk as can be, and sits up<br />

at the bar. For some reason or another, he draws his weapon and he’s so drunk and<br />

clumsy, it flies across the floor of the club. The whole place is silent. That thing<br />

could have gone off and killed someone! He was crazy!”<br />

For Olson, though, the Wah Mee Club recalls dancing the night away with Dorie.<br />

He was then a young private investigator, just back from the war, and I imagine him<br />

swaggering into the place with his wife on his arm, a gun tucked safely away in his<br />

holster, and feeling for all the world as if he was a larger, but lesser known, part of<br />

Seattle.<br />

It’s likely that Olson sidled up to the bar next to the parents of Seattle<br />

photographer and journalist Ti Locke. On her blog, “Western Women,” Locke posted<br />

a scanned, creased, black-and-white photograph of her Chinese parents and four of<br />

WAH MEE 8 TODD MATTHEWS

their friends (one Chinese man, two Caucasian men, and a Caucasian woman)<br />

gat<strong>here</strong>d around a small, round table covered in cocktail napkins and highball<br />

glasses. Locke’s parents and the woman are toasting the photographer. The group<br />

is dressed impeccably: the men wear crisp suits and silk ties, handkerchiefs poking<br />

out from the breast pockets on their blazers; one woman wears a white designer<br />

hat similar to something worn during a day at the horse races; Locke’s mother has<br />

pinned a corsage to the right breast of her blouse. On the wall behind this happy<br />

group you can see the hand-painted belly, feet, and flowing robe of a Chinese<br />

Buddha. “My parents and their friends regularly tied one on when we came to<br />

Seattle — twice a year, to stock up on Chinese groceries,” writes Locke on her blog.<br />

“They’d leave me in the Milwaukee Hotel and go drinking and gambling at the Wah<br />

Mee Club. I was quite safe at the Milwaukee — the elders would check on me, leave<br />

peppermint Life Savers under my pillow. My parents would roll back to the hotel at<br />

dawn, giggling, smelling of cigarette smoke and booze. They’d check on me and<br />

have a nightcap.”<br />

Despite cooperation from “bagmen” cops, the Wah Mee experienced several<br />

crackdowns over several decades. The club’s operators grew paranoid of its<br />

members and began to lean more toward Chinese-only clientele who knew the<br />

management. As the Wah Mee Club went underground, Caucasian people like Olson<br />

were no longer welcome. Clubgoers, most of whom were semiaffluent restaurant<br />

owners and businessmen and -women in Seattle’s Chinese American community,<br />

danced to music played on a nickelodeon. It was a place w<strong>here</strong> hardworking<br />

Chinese Americans spent their off-hours drinking and sharing stories. And it was<br />

undoubtedly a place w<strong>here</strong> money changed hands. Lots of money. The Wah Mee<br />

was host to some of the highest-stakes gambling in Seattle. Winners went home<br />

with tens of thousands of dollars after a single night of gambling. Indeed, gambling<br />

was so popular at one point that, according to Jerry F. Schimmel, an authority on<br />

coin collecting and author of Chinese-American Tokens from the Pacific Coast, the<br />

Wah Mee Club issued its own brass tokens for gamblers — a 39-millimeter-wide<br />

gem with the club’s name written in raised Chinese characters. A coin collector in<br />

WAH MEE 9 TODD MATTHEWS

California posted a photograph of two of these Wah Mee Club tokens. Both<br />

appeared well worn and had cancellation punch marks and splotchy black stains.<br />

Both coins were auctioned off in April 2011 for $58. And the Wing Luke Museum in<br />

Seattle’s Chinatown includes two aluminum Wah Mee Club tokens in its collection of<br />

artifacts.<br />

The club was last raided in the early 1970s and then fell on hard times. Mark D.<br />

Simpson, a Seattle architect whose great-grandfather, Otto John Nelson, was one of<br />

the three original Scandinavian men to construct the building more than a century<br />

ago, told me his grandmother, Minnie Nelson Harris, and her brother, William “Billie”<br />

Nelson, sold the building to Paul Woo “in the early 1970s — but it might have been<br />

earlier.” Simpson has fond memories of the building. “I have a bunch of artifacts<br />

from the building, mostly related to gambling,” Simpson recalled. “I was under the<br />

impression that my grandmother from time to time tried to clean things up and<br />

kicked out the seedier folks, keeping some of the gambling stuff I now have. My<br />

grandmother was rather embarrassed about the stuff going on in a building she<br />

owned and managed, but was also proud that her father had built it, so she did not<br />

talk about it in detail. I, on the other hand, would love to know more about it and<br />

our family involvement in it.”<br />

Despite changes in ownership, the Wah Mee Club never moved. What did change<br />

was the name of the building that housed the club — from the “Nelson, Tagholm,<br />

Jensen Tenement” to the “Hudson Hotel” to the “Louisa Hotel.” In the early 1980s,<br />

the club’s space was leased by building owner Woo, who was a former president of<br />

the Chong Wa Benevolent Association, for $350 a month to Don Mar. Mar rented the<br />

space under a sublease to the Suey Sing Association, a fraternal group. At one<br />

point, a group of four business owners each contributed $15,000 to remodel the<br />

club. Most of the money was spent on security, not aesthetics. Up until the end of<br />

the club’s run in 1983, it seemed to have restored its character as a high-stakes<br />

gambling club — though, as one patron described it, the club was “comfortable, but<br />

not opulent.” Indeed, the Wah Mee — which opened Thursday, Friday, and Saturday<br />

evenings and stayed open until six in the morning — was one of Seattle’s best clubs<br />

WAH MEE 10 TODD MATTHEWS

for high-stakes gambling in the early 1980s. Gamblers could wager up to $1,000 at<br />

a time, and up to $10,000 moved through the club nightly; the house collected<br />

5 percent. Entire paychecks were laid down in a single night.<br />

From the outside, the club was unassuming and unobtrusive. If you didn’t know<br />

it was t<strong>here</strong>, you wouldn’t likely find the door by accident. Like most after-hours<br />

gambling clubs in Chinatown, security at the Wah Mee was tight. Four rows of glass<br />

bricks fronted the club entrance. Each glass brick was opaque except one — which<br />

served as a peephole for a club guard to identify a guest and decide whether or not<br />

to permit entrance. Admittance was limited strictly to members of the club and<br />

membership consisted mostly of restaurant owners, restaurant workers, affluent<br />

members of the Chinese community, and members of the Bing Kung Tong. Club<br />

members had to be admitted past two steel doors before entering the gaming and<br />

bar areas. The club’s office was equipped with a warning buzzer and a “panic bar”<br />

that would set off an alarm. Once inside, the club was spacious, divided by a low<br />

railing. A long, curved bar was on the north side of the room. The south part of the<br />

room served as the gaming area, with four mah-jongg and Pai Gow tables.<br />

In the eyes of some Chinatown residents, the Wah Mee Club of the early 1980s<br />

was like a B-grade cocktail lounge. Its history in the neighborhood bestowed it<br />

some level of respect, but it was also a dive. Its decor was functional, not flashy:<br />

guests could lounge on old couches flanked by throw pillows, plastic detergent<br />

drums served as trash cans, cheap plastic ashtrays sat on nearly every flat surface,<br />

and a few photos were tacked to the walls (a map of mainland China, a framed<br />

portrait of a racing horse, a Chinese lunar calendar).<br />

Ruby Chow and John Okada were early members of the club. But in the early<br />

1980s, the club’s clientele changed, though it still consisted of hardworking,<br />

financially comfortable members of Seattle’s Asian community. T<strong>here</strong> was John<br />

Loui, a onetime restaurant owner who had recently sold the Golden Crown<br />

restaurant and was looking to change careers and enter the import/export<br />

business. And t<strong>here</strong> were Moo Min Mar and his wife, Jean, who owned the<br />

Kwangtung Country restaurant in Redmond. They were a wealthy couple,<br />

WAH MEE 11 TODD MATTHEWS

philanthropists who were planning to build a school in their native Chinese village.<br />

Chinn Lee Law owned a repair garage in Chinatown and was a regular at the Wah<br />

Mee, even working sometimes as a dealer and security guard. Dewey Mar was<br />

famous for having brought Chinese films to Seattle’s Chinatown, and he operated<br />

the only such theater in the entire city.<br />

The Wah Mee Club closed for good in 1983. The rows of opaque glass blocks that<br />

front the entrance are now covered in a thick layer of dirt and grime — as well as<br />

the cryptic tag names of a range of graffiti artists: AJAR, DEAMS, UH UH UH, BACE.<br />

A large chunk of the club’s stucco facade has been gouged in two places,<br />

presumably by the many delivery trucks that park in the alley having accidentally<br />

backed into the front of the club. Decades passed without the building receiving a<br />

fresh coat of paint: the facade, once painted a rich forest green, turned to a bruised<br />

and weat<strong>here</strong>d reptilian crust; the red trim that boldly framed the glass blocks,<br />

heavy double doors, and lattice above the entrance faded to the pink color of dying<br />

coral. Any other property in such a sorry state of decay would be deemed derelict<br />

by neighbors and would draw the attention of city officials: Clean up your building<br />

or else! The Wah Mee Club is different. It helps that the empty club is tucked<br />

halfway down a narrow alley, out of sight. More than that, however, one horrific<br />

event nearly thirty years ago ensures it goes unbot<strong>here</strong>d. Indeed, outsiders who<br />

visit Chinatown for dim sum or shopping at Uwajimaya pass the club without<br />

caution or notice. Chinatown old-timers, however, can’t help but glance down<br />

Maynard Alley as they shuffle along South King Street.<br />

The building that once housed the Wah Mee Club remains active. A small<br />

number of businesses lease retail space along the building’s South King Street,<br />

South Seventh Street, and Maynard Alley South sides: Palace Decor and Gifts,<br />

whose shiny gold Chinese fan taped to the store window draws your attention; Mon<br />

Hei Chinese bakery; the Chinese Christian Mission Seattle Gospel Center Bookroom;<br />

the Chinese Chamber of Commerce; Sea Garden Chinese restaurant; and the<br />

mysteriously named Pacific International Corporation, whose shades seem to<br />

always be drawn. Liem’s Aquarium and Bird Shop, located in the alley right next<br />

WAH MEE 12 TODD MATTHEWS

door to the club, is still open for business. I once mailed a postcard to the Wah Mee<br />

Club, 507-A Maynard Alley South, only to have it returned with a United States<br />

Postal Service stamp reading “return to writer — address unknown.” No one has<br />

lived in the two floors of rooms above the street-level storefronts since they were<br />

condemned in the 1970s. Some windows are covered in plywood; other windows<br />

are coated in filth. Rusty fire escapes appear brittle; they hang off the side of the<br />

building like old bones. The City of Seattle’s Department of Planning and<br />

Development shows the building, which is technically sited at 665 South King<br />

Street, was “yellow-tagged” as hazardous after the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake.<br />

Repairs were made to the parapets and six chimneys, and the issue was resolved.<br />

Despite the century-old building’s sorry state, the King County Assessor valued it<br />

at $1.89 million in 2010. Property tax bills, which average close to $20,000<br />

annually, are mailed to Jack N. Woo (whose parents owned the Moon Temple<br />

restaurant in the Seattle neighborhood of Wallingford for more than thirty years;<br />

Woo’s father, Yuen Gam Woo, cofounded the Luck Ngi Musical Society, a Chinatown<br />

hub for Cantonese Opera) of Transpacific Corporation to a post office box in<br />

Bellevue, just across Lake Washington from Seattle. The club’s doors, padlocked for<br />

nearly three decades, hang slightly ajar. One person was curious enough to tie a<br />

rope to a camera, dangle it over the tops of the doors, snap a grainy photo inside<br />

the club, and post it to Flickr.com. It’s a photo that reveals a tangle of red-vinyl-<br />

topped barstools and overturned wooden chairs amassed in a messy pyre in front of<br />

the curving bar. A wide, heavy table blocks the entrance.<br />

A gambling tolerance policy kept the Wah Mee Club alive for years. When the<br />

club officially closed, it was at the hands of three young men who left thirteen dead<br />

bodies on the floor, and one lucky survivor to recount the horror.<br />

For more information and to purchase the complete e-book, visit<br />

wahmee.com.<br />

WAH MEE 13 TODD MATTHEWS

<strong>Todd</strong> <strong>Matthews</strong> is a journalist who has worked for a variety of newspapers and<br />

magazines in the Pacific Northwest.<br />

As a freelance writer for Seattle magazine, he received third-place honors<br />

(2007) from the Society of Professional Journalists for his feature article about the<br />

University of Washington’s Innocence Project and its work in helping to exonerate a<br />

Yakima man through DNA testing after he spent ten years in prison, and first-place<br />

honors (2007) for his feature article about Seattle’s bike messengers.<br />

As a freelance writer at Washington Law & Politics magazine, he received third-<br />

place honors (2001) from the Society of Professional Journalists for his prison<br />

interview with Prison Legal News founder Paul Wright, and second-place honors<br />

(2003) for his article about whistle-blowers in Washington State.<br />

In 2007, he received the award for Outstanding Achievement in Media from the<br />

Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for his work<br />

covering historic preservation in Tacoma for the Tacoma Daily Index, w<strong>here</strong> he is<br />

the editor.<br />

His work has also appeared in All About Jazz, City Arts Tacoma, Earshot Jazz,<br />

Homeland Security Today, Jazz Steps, Journal of the San Juans, Lynnwood-<br />

Mountlake Terrace Enterprise, Prison Legal News, Rain Taxi, Real Change, Seattle<br />

Business Monthly, Tablet, Washington CEO, and Washington Free Press.<br />

He is a graduate of the University of Washington and holds a bachelor’s degree<br />

in communications.<br />

WAH MEE 14 TODD MATTHEWS