'à es us e ct n s, es - Sexton Digtial Initiatives - Dalhousie University

'à es us e ct n s, es - Sexton Digtial Initiatives - Dalhousie University

'à es us e ct n s, es - Sexton Digtial Initiatives - Dalhousie University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

15 $ 15 $<br />

VOL.36 > N o 1 > 2011

The SocieTy for The STudy of ArchiTecTure in cAnAdA is a learned society<br />

devoted to the examination of the role of the built environment in Canadian society. Its membership includ<strong>es</strong><br />

stru<strong>ct</strong>ural and landscape archite<strong>ct</strong>s, archite<strong>ct</strong>ural historians and planners, sociologists, ethnologists, and<br />

specialists in such fields as heritage conservation and landscape history. Founded in 1974, the Society is currently<br />

the sole national society whose foc<strong>us</strong> of inter<strong>es</strong>t is Canada’s built environment in all of its manif<strong>es</strong>tations.<br />

the Journal of the Society for the Study of Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure in Canada, published twice a year, is a refereed journal.<br />

Membership fe<strong>es</strong>, including subscription to the Journal, are payable at the following rat<strong>es</strong>: Student, $30;<br />

Individual,$50; organization | Corporation, $75; Patron, $20 (pl<strong>us</strong> a donation of not l<strong>es</strong>s than $100).<br />

Institutional subscription: $75. Individuel subscription: $40.<br />

there is a surcharge of $5 for all foreign memberships. Contributions over and above membership fe<strong>es</strong> are welcome,<br />

and are tax-dedu<strong>ct</strong>ible. Please make your cheque or money order payable to the:<br />

SSAC > Box 2302, Station D, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

LA SociéTé pour L’éTude de L’ArchiTecTure Au cAnAdA <strong>es</strong>t une société savante qui se<br />

consacre à l’étude du rôle de l’environnement bâti dans la société canadienne. S<strong>es</strong> membr<strong>es</strong> sont archite<strong>ct</strong><strong>es</strong>,<br />

archite<strong>ct</strong><strong>es</strong> paysagist<strong>es</strong>, historiens de l’archite<strong>ct</strong>ure et de l’urbanisme, urbanist<strong>es</strong>, sociologu<strong>es</strong>, ethnologu<strong>es</strong><br />

ou spécialist<strong>es</strong> du patrimoine et de l’histoire du paysage. Fondée en 1974, la Société <strong>es</strong>t présentement la seule<br />

association nationale préoccupée par l’environnement bâti du Canada so<strong>us</strong> tout<strong>es</strong> s<strong>es</strong> form<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Le Journal de la Société pour l’étude de l’archite<strong>ct</strong>ure au Canada, publié deux fois par année, <strong>es</strong>t une revue dont l<strong>es</strong><br />

articl<strong>es</strong> sont évalués par un comité de le<strong>ct</strong>ure.<br />

La cotisation annuelle, qui comprend l’abonnement au Journal, <strong>es</strong>t la suivante : étudiant, 30 $; individuel, 50 $;<br />

organisation | société, 75 $; bienfaiteur, 20 $ (pl<strong>us</strong> un don d’au moins 100 $).<br />

Abonnement institutionnel : 75 $. Abonnement individuel : 40 $<br />

un supplément de 5 $ <strong>es</strong>t demandé pour l<strong>es</strong> abonnements étrangers. L<strong>es</strong> contributions dépassant l’abonnement<br />

annuel sont bienvenu<strong>es</strong> et dédu<strong>ct</strong>ibl<strong>es</strong> d’impôt. veuillez s.v.p. envoyer un chèque ou un mandat postal à la :<br />

SÉAC > Case postale 2302, succursale D, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

www.canada-archite<strong>ct</strong>ure.org<br />

The Journal of the Society for the Study of Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure in Canada is produced<br />

with the assistance of the Canada R<strong>es</strong>earch Chair on Urban Heritage. This<br />

issue was also produced with the financial assistance of the Canadian Forum<br />

for Public R<strong>es</strong>earch on Heritage.<br />

Le Journal de la Société pour l’étude de l’archite<strong>ct</strong>ure au Canada <strong>es</strong>t publié<br />

avec l’aide de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urbain.<br />

Ce numéro a a<strong>us</strong>si bénéficié de l’apport financier du Forum canadien<br />

de recherche publique sur le patrimoine.<br />

Publication Mail 40739147 > PAP Registration No. 10709<br />

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Government of Canada,<br />

through the Publications Assistance Program (PAP), toward our mailing costs.<br />

ISSN 1486-0872<br />

(supersed<strong>es</strong> | remplace ISSN 0228-0744)<br />

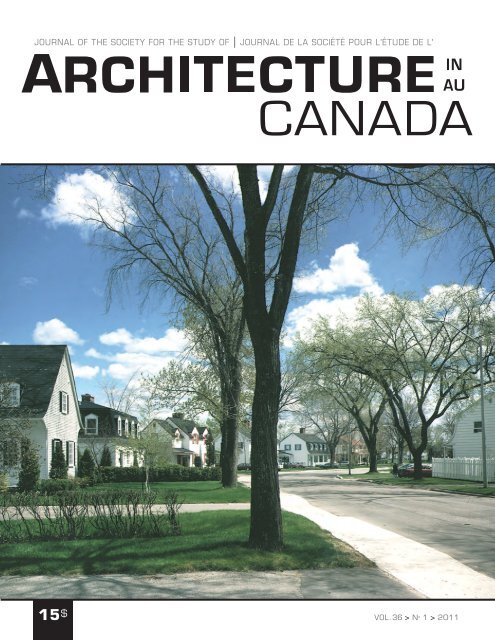

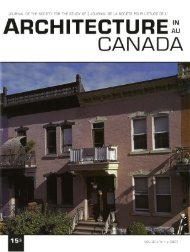

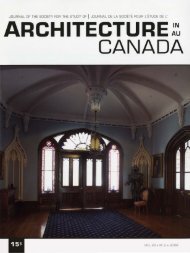

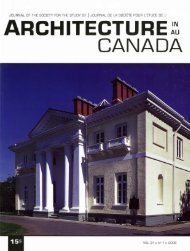

Cover | Couverture<br />

Workers' ho<strong>us</strong>ing and landscaping on rue Vaudreuil<br />

at the corner of rue Burma looking northeast, south Arvida<br />

(photo: Gabor Szilasi, 1995 (Centre Canadien d’Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure PH1995:0081)).<br />

JournAL edItor | rédACteur du JournAL<br />

Luc noppen<br />

Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urbain<br />

Université du Québec à Montréal<br />

C.P. 8888, succ. centre-ville<br />

Montréal, QC H3C 3P8<br />

t : 514 987-3000 x 2562 / f : 514 987-6881<br />

e : noppen.luc@uqam.ca<br />

ASSIStAnt edItor | AdJoInt à LA rédACtIon<br />

mArTin drouin<br />

e : drouin.martin@uqam.ca<br />

ASSIStAnt edItor | AdJoInt à LA rédACtIon<br />

peTer coffmAn<br />

e : petercoffman@dal.ca<br />

AdMInIStrAtIve ASSIStAnt | ASSIStAnte AdMInIStrAtIve<br />

heATher mcArThur<br />

206 Jam<strong>es</strong> Street<br />

Ottawa, ON K1R 5M7<br />

t : 613 204-6662<br />

e : foodnshelter@gmail.com<br />

edItIng, ProoFreAdIng, trAnSLAtIon | révISIon<br />

LInguIStIque, trAduCtIon<br />

micheLine giroux-AuBin<br />

grAPhIC deSIgn | ConCePtIon grAPhIque<br />

mAriKe pArAdiS<br />

PAge MAke-uP | MISe en PAgeS<br />

B grAphiSTeS<br />

PrIntIng | IMPreSSIon<br />

imprimerie r. m. héBerT inc.<br />

PreSIdent | PréSIdent<br />

peTer coffmAn<br />

School for Studi<strong>es</strong> in Art and Culture<br />

Carleton <strong>University</strong><br />

404 St. Patrick's Building<br />

Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6<br />

t : 613 520-2600 x 8797<br />

e : peter_coffman@carleton.ca<br />

vICe-PreSIdentS | vICe-PréSIdent(e)S<br />

Lucie K. moriSSeT<br />

Département d'étud<strong>es</strong> urbain<strong>es</strong> et touristiqu<strong>es</strong><br />

Université du Québec à Montréal<br />

C.P. 8888, succ. centre-ville<br />

Montréal, QC H3C 3P8<br />

t : 514 987-3000 x 4585 / f : 514 987-6881<br />

e : morisset.lucie@uqam.ca<br />

BArry mAgriLL<br />

8080 Dalemore Road<br />

Richmond, BC V7C 2A6<br />

t : 604 241-0787<br />

e : barrymagrill@shaw.ca<br />

treASurer | tréSorIer<br />

mArTin drouin<br />

Institut du patrimoine<br />

Université du Québec à Montréal<br />

C.P. 8888, succ. centre-ville<br />

Montréal, QC H3C 3P8<br />

t : 514 987-3000 x 5626<br />

e : drouin.martin@uqam.ca<br />

SeCretAry | SeCrétAIre<br />

nicoLAS miqueLon<br />

Parcs Canada<br />

25, rue Eddy (25-5-R)<br />

Gatineau, QC K1A 0M5<br />

t : 819 921-1043<br />

e : nicolas.miquelon@pc.gc.ca<br />

ProvInCIAL rePreSentAtIveS |<br />

rePréSentAnt(e)S deS ProvInCeS<br />

BernArd fLAmAn<br />

PWGSC – TPSGC<br />

201-1800 11th Avenue<br />

Regina, SK S4P 0H8<br />

t : 306 780 3280 / f : 306 780 7242<br />

e : bernard.flaman@pwgsc-tpsgc.gc.ca<br />

John Leroux<br />

<strong>University</strong> of New Brunswick<br />

351 Regent Street<br />

Frederi<strong>ct</strong>on, NB E3B 3X3<br />

t : 506 455-4277<br />

e : johnnyleroux@hotmail.com<br />

Ann howATT-KrAhn<br />

31 Vi<strong>ct</strong>ory Avenue<br />

Charlottetown, PEI C1A 5E9<br />

t : 902 368-1532<br />

e : ahowatt@upei.ca<br />

dAnieL miLLeTTe<br />

2636 Hemlock Street<br />

Vancouver, BC V6H 2V5<br />

t / f : 604 642-2432<br />

e : millette.daniel@yahoo.com<br />

KAyhAn nAdJi<br />

126 Niven Drive<br />

Yellowknife, NT X1A 3W8<br />

t / f : 867 920-6331<br />

e : kayhen@nadji-archite<strong>ct</strong>s.ca<br />

mAThieu pomerLeAu<br />

379, rue de Liège<br />

Montréal, QC H2P 1J6<br />

e : mathieu.pomerleau@gmail.com<br />

STeven mAnneLL<br />

Dire<strong>ct</strong>or, College of S<strong>us</strong>tainability<br />

Dalho<strong>us</strong>ie <strong>University</strong><br />

Box 1000-5410 Spring Garden Rd<br />

Halifax, NS B3J 2X4<br />

t : 902 494-6122<br />

e : steven.mannell@dal.ca<br />

cAndAce iron<br />

46 O'Shea Cr<strong>es</strong>., Lower Suite<br />

Toronto, ON M2J 2N5<br />

t : 416 494-0421<br />

e : candace@yorku.ca

a n a lY s e s | a n a lY s e s<br />

e s s aY s | e s s a i s<br />

> Lucie K. Morisset<br />

Non-Fi<strong>ct</strong>ion Utopia<br />

Arvida, Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle Made Real<br />

> Lyne Bernier<br />

La conversion d<strong>es</strong> églis<strong>es</strong> à Montréal<br />

État de la qu<strong>es</strong>tion<br />

> nichoLas Lynch<br />

“Converting” Space in Toronto<br />

The Adaptive Re<strong>us</strong>e of the Former Centennial<br />

Japan<strong>es</strong>e United Church to the “Church Lofts”<br />

> Martin Br<strong>es</strong>sani<br />

et Marc GriGnon<br />

Le patrimoine et l<strong>es</strong> plaisirs de la fi<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

> roBert shipLey and<br />

nicoLe McKernan<br />

A Shocking Degree of Ignorance Threatens<br />

Canada’s Archite<strong>ct</strong>ural Heritage<br />

The Case for Better Education To Stem the Tide<br />

of D<strong>es</strong>tru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

> steven ManneLL<br />

The Dream (and Lie) of Progr<strong>es</strong>s<br />

Modern Heritage, Regionalism,<br />

and Folk Traditions in Atlantic Canada<br />

> howard shuBert<br />

The Montreal Forum<br />

The Hockey Arena at the Nex<strong>us</strong> of Sport, Religion,<br />

and Cultural Politics<br />

contents | table d<strong>es</strong> matièr<strong>es</strong><br />

3<br />

41<br />

65<br />

77<br />

83<br />

93<br />

107<br />

VOL.36 > N o 1 > 2011

Archite<strong>ct</strong>ural and urban historian LuCie K.<br />

MOriSSet is a prof<strong>es</strong>sor in the Department of<br />

urban and tourism studi<strong>es</strong> at université du Québec<br />

à Montréal. She is a member of the university's<br />

institut du patrimoine, associate to the Canada<br />

r<strong>es</strong>earch Chair on urban Heritage and a r<strong>es</strong>earcher<br />

with Centre interuniversitaire d'étud<strong>es</strong> sur l<strong>es</strong><br />

lettr<strong>es</strong>, l<strong>es</strong> arts et l<strong>es</strong> traditions. Following on<br />

her work on the hermeneutics of built landscape<br />

and urban repr<strong>es</strong>entations, her current r<strong>es</strong>earch<br />

foc<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> on Quebec's patrimonial memory and the<br />

history of the province's heritage. She is currently<br />

finishing up a new monograph on Arvida for Pr<strong>es</strong>s<strong>es</strong><br />

de l'université du Québec.<br />

fig. 1. One Of the Old<strong>es</strong>t streets in ArvidA, in the heArt Of “the city built in 135 dAys,” bOulevArd tAschereAu,<br />

nOw knOwn As du sAguenAy. | PhOtOgrAPh by guillAume st-JeAn.<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011 > 3-40<br />

analYsis | analYse<br />

NoN-Fi<strong>ct</strong>ioN Utopia<br />

arvida, cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle Made Real 1<br />

> Lucie K. Morisset<br />

Une cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, that mil<strong>es</strong>tone<br />

in W<strong>es</strong>tern archite<strong>ct</strong>ural and urban<br />

history, was conceived by Tony Garnier<br />

in the first decad<strong>es</strong> of the 20 th century.<br />

The book was first published in<br />

1917 and went on to enjoy a phenomenal<br />

critical reception (fig. 3). Pevsner<br />

(Pioneers in the Modern Movement),<br />

Banham (Theory and D<strong>es</strong>ign in the<br />

First Machine Age), Giedion (Space,<br />

Time and Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure), and Alexander<br />

(A City is Not a Tree) have enshrined it<br />

as a classic in the evolution of urban<br />

planning: “Projet de cité idéale le pl<strong>us</strong><br />

complet depuis l<strong>es</strong> Salin<strong>es</strong> de Chaux”<br />

[the Saltworks of Chaux, published in<br />

L’archite<strong>ct</strong>ure considérée so<strong>us</strong> le rap‑<br />

port de l’art, d<strong>es</strong> mœurs et de la législa‑<br />

tion] de Ledoux, (1804) 2 Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle<br />

“pra<strong>ct</strong>ically provided a blueprint for a<br />

new type of urban centre d<strong>es</strong>igned<br />

around the possibiliti<strong>es</strong> of contemporary<br />

technology, new constru<strong>ct</strong>ion methods<br />

and efficient transportation.” 3 In<br />

the years immediately following its publication<br />

and before a seri<strong>es</strong> of reprints<br />

later in the century, cité was noted in<br />

1919 by Le Corb<strong>us</strong>ier, 4 but seems to have<br />

been most carefully considered in a<br />

1926 article in La constru<strong>ct</strong>ion moderne,<br />

in which Pierre Bourgeix noted its philosophy<br />

of urban d<strong>es</strong>ign. 5 However, it is<br />

as an archetypal precursor to integrated<br />

planning, 6 an approach that took hold<br />

in the wake of the Athens Charter (published<br />

in 1941), that Garnier’s influence<br />

has most readily been acknowledged.<br />

European r<strong>es</strong>earchers, having noted a<br />

citation of Garnier by Lewis Mumford,<br />

concluded that the Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle<br />

m<strong>us</strong>t have served as a model for the<br />

development of the Hiwassee Valley by<br />

3

4<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 2. OrthOgrAPhic view Of Pr<strong>es</strong>ent-dAy ArvidA (nOw PArt Of the city Of sAguenAy) As built between 1925<br />

And 1950, centred On its Aluminuum smelter. the fOrmer mOdel city is currently the site Of A mAJOr<br />

mOdernizAtiOn initiAtive led by riO tintO AlcAn, succ<strong>es</strong>sOr cOmPAny tO AlcAn, which succeeded AlcOA<br />

As mAnAger Of the smelter. | terrA metrics/gOOgle.<br />

the Tenn<strong>es</strong>see Valley Authority between<br />

1936 and 1940. As Mumford had collaborated<br />

on this proje<strong>ct</strong>, it was thought<br />

that he m<strong>us</strong>t have <strong>us</strong>ed Une cité ind<strong>us</strong>‑<br />

trielle, borrowing its “innovative”<br />

notion of regional planning (although<br />

regional planning was already part of<br />

the vocabulary at the national city planning<br />

conferenc<strong>es</strong> in the United Stat<strong>es</strong>,<br />

the first of which was held in 19097 ).<br />

But, as we shall see, another “cité<br />

neuve,” (“new city”) to <strong>us</strong>e Garnier’s<br />

vocabulary, was contemporary with<br />

the Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle and seems to share<br />

many of the featur<strong>es</strong> that in Garnier<br />

have been seen as revolutionary. It was<br />

hailed both for its planning and overall<br />

d<strong>es</strong>ign and recognized in the interwar<br />

period as “[an] example of significant<br />

advanc<strong>es</strong> a<strong>ct</strong>ually executed throughout<br />

the world,” “[an] entirely new city<br />

<strong>es</strong>tablished in the wildern<strong>es</strong>s.” 8 It made<br />

headlin<strong>es</strong> at the time and appeared in<br />

textbooks on both sid<strong>es</strong> of the Atlantic.<br />

No fewer than three university th<strong>es</strong><strong>es</strong>,<br />

two monographs, an <strong>es</strong>say, and even a<br />

novel took it as a subje<strong>ct</strong>, in addition<br />

to some fifty specialized archite<strong>ct</strong>ure,<br />

engineering, economics, and sociology<br />

articl<strong>es</strong> (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5). Late in the century,<br />

the Robert II encyclopedia featured<br />

the following entry:<br />

ArViDA. V. ind<strong>us</strong>trielle du Canada (Québec)<br />

sur le Saguenay, proche de Chicoutimi.<br />

14 500 hab. – <strong>us</strong>ine d’aluminium traitant<br />

la bauxite […], grâce à l’hydroéle<strong>ct</strong>ricité.<br />

(Arvida: ind<strong>us</strong>trial city in Quebec, Canada,<br />

on the Saguenay river near Chicoutimi.<br />

Population: 14,500. Aluminum smelter proc<strong>es</strong>sing<br />

bauxite […] <strong>us</strong>ing hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ricity.)<br />

Insofar as French Canadian clerical<br />

nationalist censorship in the twenti<strong>es</strong> and<br />

Arvida’s critical role in the Second World<br />

War (akin to that of the Secret City—Oak<br />

Ridge, Tenn<strong>es</strong>see) kept the Aluminum<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

fig. 3. bird’s eye view Of cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle drAwn by tOny gArnier,<br />

first Published in 1917. the city stAnds On A rOcky PlAteAu<br />

next tO A vAlley with An imPOsing dAm. | tOny gArnier, une cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, 1917.<br />

fig. 5. AeriAl view Of ArvidA frOm the sOuth lOOking nOrth,<br />

shOrtly After the secOnd wOrld wAr. | riO tintO AlcAn (mOntreAl).<br />

City off the world’s critical radar, the<br />

history of its contribution to urban<br />

d<strong>es</strong>ign has also remained incomplete.<br />

With recent works like The Company<br />

Towns, Company Towns in the Americas,<br />

Fordlandia and Duluth, U.S. Steel, and<br />

the Forging of a Company Town 9 from<br />

John S. Garner, John W. Reps, Margaret<br />

Crawford, and Jean-Pierre Frey10 arriving<br />

to enrich the critical corp<strong>us</strong> made up of<br />

such 20 th century classics as The City in<br />

History (1961) and The Making of Urban<br />

America (1965), it seems like a good<br />

time to revisit the adventure in archite<strong>ct</strong>ure<br />

and urban planning that was<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

Arvida, 11 the city created from scratch in<br />

the Canadian backcountry in 1925 and<br />

named from its founder’s nam<strong>es</strong>: ARthur<br />

VIning DAvis, pr<strong>es</strong>ident of the Aluminum<br />

Company of America and one of the last<br />

of the ind<strong>us</strong>trial utopians.<br />

Af ter Rober t Owen’s New L anark<br />

(Scotland, c. 1800), which was added<br />

to the UNESCO World Heritage List in<br />

2001 for having seen “the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

not only of well d<strong>es</strong>igned and equipped<br />

workers’ ho<strong>us</strong>ing but also public buildings<br />

d<strong>es</strong>igned to [addr<strong>es</strong>s] their spiritual<br />

as well as their physical needs,” 12 the<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 4. the Old<strong>es</strong>t street in ArvidA, OriginAlly cAlled rue rAdin, nOw knOwn<br />

As lA trAverse, where the city’s first hO<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> were built in 1926,<br />

seen ArOund 1930. | ville de sAguenAy.<br />

fig. 6. r<strong>es</strong>identiAl distri<strong>ct</strong> Of cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle. | tOny gArnier, une cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, 1917.<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>trial era gave new impet<strong>us</strong> to the<br />

age-old qu<strong>es</strong>t for living environments<br />

conducive to human fulfilment. As such,<br />

Tony Garnier belongs to a long line of<br />

thinkers stretching back to Hippodamos<br />

of Milet and Thomas More. This is the<br />

context in which our article intends to<br />

situate both the “cité neuve” of Arvida<br />

and Garnier’s Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle—mirror<br />

imag<strong>es</strong> in the history of urban planning.<br />

Indeed, the utopia given modern graphic<br />

form by Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle seems to have<br />

developed and taken root in a unique<br />

(and tangible) way in Arvida, which in<br />

turn can only be properly understood in<br />

5

6<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 7. “AeriAl PlAn Of the cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle PrOJe<strong>ct</strong> As Pr<strong>es</strong>ented At the exhibitiOns<br />

in rOme And PAris in 1901 And 1904.” | tOny gArnier, une cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, 1917.<br />

fig. 9. yOrkshiP villAge (cAmden), new Jersey, wAs nAmed <strong>us</strong>ing<br />

An AnAgrAm Of the nAme Of new yOrk shiPbuilding<br />

cOrPOrAtiOn. | ele<strong>ct</strong><strong>us</strong> dArwin lichtfield, Archite<strong>ct</strong> And tOwn PlAnner, 1914-1917.<br />

light of the history of ideas and ideals<br />

that inspired Garnier. The comparison<br />

exercise we propose here aims to better<br />

measure a contribution to a history<br />

of city planning that the literature has<br />

heretofore attributed more excl<strong>us</strong>ively<br />

to Garnier’s Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, while at<br />

the same time placing both model citi<strong>es</strong><br />

in a broader context. It also seeks<br />

to define the conditions of possibility<br />

that other ind<strong>us</strong>trial citi<strong>es</strong> lacked and<br />

Arvida poss<strong>es</strong>sed. After the experienc<strong>es</strong><br />

of Badin, North Carolina, and Alcoa,<br />

Tenn<strong>es</strong>see, that put the Aluminum<br />

Company of American at the forefront<br />

of developments in urban planning, it<br />

was particular ind<strong>us</strong>trial preconditions,<br />

like those Garnier himself imagined<br />

for his hydro-powered metallurgical<br />

city, that brought Arvida into being.<br />

For the first and undoubtedly the last<br />

time in the history of citi<strong>es</strong>, a particular<br />

conjun<strong>ct</strong>ion of idealism, expertise,<br />

and exceptional geography allowed<br />

what remained only a dream in Europe<br />

to come to fruition in Arvida, the town<br />

where reality went beyond fi<strong>ct</strong>ion.<br />

Utopias with historY<br />

As I noted, Garnier’s impa<strong>ct</strong> has generally<br />

been ass<strong>es</strong>sed according to the<br />

episteme of those who saw his work<br />

as a refle<strong>ct</strong>ion of their own thinking,<br />

fig. 8. PrOmOtiOnAl Pi<strong>ct</strong>ure And mAP Of PullmAn, illinOis. | PrivAte cOlle<strong>ct</strong>iOn.<br />

fig. 10. fOrd’s PrOJe<strong>ct</strong> At m<strong>us</strong>cle shOAls, AlAbAmA, As Published in scientific AmericAn<br />

in 1922.<br />

with a r<strong>es</strong>ulting tendency to foc<strong>us</strong> on<br />

certain relatively peripheral aspe<strong>ct</strong>s.<br />

Concrete buildings conjured link s<br />

between Garnier and Perret, and the<br />

open block d<strong>es</strong>ign <strong>us</strong>ed by reconstru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

d<strong>es</strong>igners were traced back to the<br />

Lyonnais archite<strong>ct</strong>’s urban ideas to<br />

produce a particular analytic framework<br />

(fig. 6). As we have mentioned,<br />

Garnier was also associated, following<br />

Bourdeix, with the origin of modern<br />

city planning principl<strong>es</strong> according to<br />

which “stri<strong>ct</strong> segregation into separate<br />

zon<strong>es</strong> for ind<strong>us</strong>try, r<strong>es</strong>idential and<br />

civic fun<strong>ct</strong>ions provided the formula for<br />

towns that would be both humane and<br />

economically produ<strong>ct</strong>ive” (fig. 7).<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

The European, and <strong>es</strong>pecially French,<br />

framework in which Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle<br />

has habitually been placed has it that<br />

its contribution to the history of urban<br />

planning li<strong>es</strong> in its <strong>us</strong>e of public space to<br />

promote r<strong>es</strong>idents’ wellbeing. In addition,<br />

Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle is noted for the<br />

fa<strong>ct</strong> that its urban and archite<strong>ct</strong>ural plan<br />

is entirely diagrammed out, an aspe<strong>ct</strong><br />

the 19th century utopias lack, even the<br />

renowned Garden City of Ebenezer<br />

Howard (1898). Urban historiography<br />

has further seen Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle’s<br />

interse<strong>ct</strong>ion with 20 th century modernity<br />

as personified in the conjun<strong>ct</strong>ion of<br />

metallurgy and hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ricity that<br />

calls it into being. Scholars pondered<br />

the astonishing realism of the proje<strong>ct</strong><br />

before eventually tagging it as an “ideal<br />

realism” more typical of utopianism than<br />

urban d<strong>es</strong>ign, 13 at least in its predominant<br />

1930s and 40s forms, and situating<br />

it in the lineage of Fourier’s phalansterian<br />

theori<strong>es</strong>. 14 After extensive r<strong>es</strong>earch,<br />

fuelled by the proje<strong>ct</strong>’s very realism,<br />

failed to turn up the intended site of<br />

the Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, many concluded<br />

that Garnier had meant only to propose<br />

an archetype rather than provide a<br />

specific solution—to ill<strong>us</strong>trate the philosophical<br />

or archite<strong>ct</strong>ural produ<strong>ct</strong>ions of<br />

its time. At b<strong>es</strong>t, this would make Cité<br />

Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle one of the last of the great<br />

dreams: “Tony Garnier,” it was said, “was<br />

the initiator of an entirely independent<br />

science of town planning and archite<strong>ct</strong>ure,<br />

which ended with him as well.” 15<br />

Th<strong>us</strong> apart from finding trac<strong>es</strong> of the<br />

Lyonnais archite<strong>ct</strong>’s ideas in his succ<strong>es</strong>sors<br />

or in fun<strong>ct</strong>ionalist urban d<strong>es</strong>ign, or<br />

seeking the “real” Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle in<br />

the southeastern France where Garnier<br />

exeget<strong>es</strong> following his own indications,<br />

went looking for it, scholars have paid<br />

little attention to the relationship<br />

between this utopia and its materialization<br />

in the real context of contemporary<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

planning. More specifically, as the<br />

above exampl<strong>es</strong> show, the relationships<br />

between Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle and<br />

town planning in its familiar Frontier<br />

Town America form—where we know<br />

Garnier for a time considered moving16<br />

—have scarcely been considered. In<br />

the United Stat<strong>es</strong> and Canada, ubiquito<strong>us</strong><br />

post-World War I ho<strong>us</strong>ing problems<br />

engendered a lively field of r<strong>es</strong>earch<br />

and pra<strong>ct</strong>ice—that of the town planner,<br />

precursor to the urban d<strong>es</strong>igner and<br />

heir to the Beaux-Arts archite<strong>ct</strong>s who<br />

created the City Beautiful. At the same<br />

time as Garnier was publishing his Une<br />

cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, the guiding principl<strong>es</strong><br />

of what was then called comprehensive<br />

city planning—“from street pattern up”<br />

as the expr<strong>es</strong>sion went—were being laid<br />

out in textbooks such as City Planning:<br />

The Essential Elements of a City Plan,<br />

Ind<strong>us</strong>trial Ho<strong>us</strong>ing and Rural Planning<br />

and Development, in the pag<strong>es</strong> of<br />

Landscape Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure, Archite<strong>ct</strong>ural<br />

Record, American Institute of Archite<strong>ct</strong>s<br />

Journal, Journal of the Town Planning<br />

Institute of Canada, Town Planning<br />

Review, Constru<strong>ct</strong>ion, and Archite<strong>ct</strong>ural<br />

Forum, and in the works of urban<br />

d<strong>es</strong>igners such as Thomas Adams, Morris<br />

Knowl<strong>es</strong>, and John Nolen.<br />

Although we find relatively few contemporary<br />

European exampl<strong>es</strong> of comprehensive<br />

and detailed city plans—with<br />

buildings, fun<strong>ct</strong>ions, and institutions<br />

all laid out and everything from the<br />

general plan to the shape of dwellings<br />

included—what in Garnier was<br />

an innovation was already relatively<br />

common in North American by the<br />

1910s. While specialized periodicals<br />

of the time maintained, at least until<br />

the war, a certain number of more fi<strong>ct</strong>ional<br />

than obje<strong>ct</strong>ive theoretical propositions,<br />

hands-on exampl<strong>es</strong> of real<br />

North American know-how were multiplying.<br />

One pioneering experiment was<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

Pullman City, Illinois, where, in 1880,<br />

George Pullman commissioned archite<strong>ct</strong><br />

Solon S. Beman and landscape archite<strong>ct</strong><br />

Nathan F. Barrett to produce an overall<br />

plan for the town where his workers—<br />

his “children” as he apparently called<br />

them—would build rail cars (fig. 8).<br />

Their work attra<strong>ct</strong>ed attention as far<br />

away as Garnier’s Europe: discovered<br />

by the crowds during the 1893 Chicago<br />

Columbian Exhibition nearby, Pullman<br />

City, which contained b<strong>us</strong>in<strong>es</strong>s<strong>es</strong>, parks,<br />

and a church, as well as row ho<strong>us</strong>ing for<br />

the prospero<strong>us</strong> ind<strong>us</strong>trialist’s “children,”<br />

was dubbed “The World’s Most Perfe<strong>ct</strong><br />

Town” at an 1896 exhibition in Prague.<br />

It is important to recall that—its historic<br />

citi<strong>es</strong> aside—most North American<br />

towns and citi<strong>es</strong> were founded in the late<br />

19th century and <strong>es</strong>pecially in the early<br />

decad<strong>es</strong> of the 20 th , and that, in order<br />

to play the role they did in opening up<br />

new Canadian and American territory,<br />

they needed to be planned carefully and<br />

holistically. They are called “planned<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>trial towns,” “company towns,”<br />

and sometim<strong>es</strong> “r<strong>es</strong>ource towns,” since<br />

they were generally built around the<br />

natural r<strong>es</strong>ourc<strong>es</strong> being exploited by<br />

compani<strong>es</strong> penetrating ever deeper<br />

into the hinterland—hence the need for<br />

worker ho<strong>us</strong>ing. “Most new towns built<br />

from now on,” wrote Garnier, “will foc<strong>us</strong><br />

on ind<strong>us</strong>try.” 17 The predi<strong>ct</strong>ion certainly<br />

held true for North America, where<br />

exampl<strong>es</strong> proliferate to negate any claim<br />

Garnier might have had to inventing,<br />

say, segregated urban fun<strong>ct</strong>ions: after<br />

Pullman City, the plans for Vandergrift,<br />

Pennsylvania (Frederick Law Olmsted<br />

and J.C. Olmsted, 1895), and Yorkship,<br />

New Jersey (Ele<strong>ct</strong><strong>us</strong> D. Lichtfield, 1914),<br />

to name but two, both segregate ind<strong>us</strong>trial,<br />

r<strong>es</strong>idential, and civic fun<strong>ct</strong>ions<br />

rationally within the urban setting,<br />

with circulation meticulo<strong>us</strong>ly mapped<br />

out between them (fig. 9).<br />

7

8<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 11. riverside Avenue in fOrdlAndiA. the henry fOrd m<strong>us</strong>eum, Published<br />

in greg grAndin, fOrdlAndiA…, P. 274.<br />

fig. 13. One Of the ecliPse PArk (belOit, wiscOnsin)<br />

hO<strong>us</strong>e mOdels As Published in 1918 by<br />

lAwrence veiller in A seri<strong>es</strong> Of Articl<strong>es</strong><br />

in the Archite<strong>ct</strong>urAl recOrd, entitled<br />

“ind<strong>us</strong>triAl hO<strong>us</strong>ing develOPments in<br />

AmericA.”<br />

With ind<strong>us</strong>trial development, the concept<br />

of model city became, in North America,<br />

an instrument of territorial conqu<strong>es</strong>t,<br />

with vast expans<strong>es</strong> of undeveloped land<br />

fuelling dreams of all kinds. From Robert<br />

Owen, who after New Lanark went on to<br />

found New Harmony in Indiana, to Frank<br />

Lloyd Wright with his mythic Broadacre<br />

City, the geographic potential of the territory<br />

excited the imaginations of those<br />

who credited agrarian settings (“nature”)<br />

with hygienic and even chara<strong>ct</strong>er-building<br />

virtu<strong>es</strong>. We th<strong>us</strong> see not only the sudden<br />

appearance of agrarian utopias, but also<br />

of urban creations, which, d<strong>es</strong>pite charg<strong>es</strong><br />

of paternalism levelled at them by certain<br />

historians, still shared many of the<br />

social aims of Garnier’s Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle.<br />

To take two l<strong>es</strong>s familiar exampl<strong>es</strong>: Baie-<br />

Comeau, Quebec, was first conceived<br />

in the 1920s by ind<strong>us</strong>trialist Robert R.<br />

McCormick and built in the 1930s as a<br />

pulp and paper town of some 2,000 r<strong>es</strong>idents,<br />

while Hershey Town, Pennsylvania<br />

(1924) was the chocolate-producing town<br />

created by ind<strong>us</strong>trialist Milton Hershey. It<br />

became a popular tourist attra<strong>ct</strong>ion and<br />

billed as “the sweet<strong>es</strong>t place on earth […],<br />

where the streets are lined with Hershey’s<br />

Kiss<strong>es</strong>-shaped street lights,” as well as a<br />

“model town [built] for employe<strong>es</strong> and<br />

their famili<strong>es</strong> so they have an attra<strong>ct</strong>ive<br />

place to live, work, and play.” 18 Starting<br />

at the beginning of the century, there is a<br />

concrete paradigm shift in North America<br />

fig. 12. eugene hAberer, bird’s eye view bAsed On the PrOPOsed shAwinigAn<br />

tOwnsite PlAn, 1901. | cité de l’énergie, shAwinigAn.<br />

that, above and beyond the foc<strong>us</strong> on<br />

detailed planning, also refle<strong>ct</strong>s Garnier’s<br />

Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle in the idea of the ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

town as an integrated organism that,<br />

rather than ignoring or fleeing ind<strong>us</strong>try,<br />

<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> it, as well as its modern corollari<strong>es</strong><br />

(transportation, habitat, and economy) as<br />

a lever for individual development and<br />

fulfilment. Town planning and ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

philanthropy join forc<strong>es</strong>.<br />

This idea of a new, modern ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

Arcadia did not survive the fragmentation<br />

of urban d<strong>es</strong>ign and the Athens Charter’s<br />

fun<strong>ct</strong>ionalism, but did find expr<strong>es</strong>sion<br />

in a certain number of communiti<strong>es</strong><br />

founded before the end of the Great<br />

War: Kistler, Pennsylvania (1918), Morgan<br />

Park, Minn<strong>es</strong>ota (1917), Kohler, Wisconsin<br />

(1913), and Fairfield, Alabama (1910) are<br />

some of the b<strong>es</strong>t known U.S. exampl<strong>es</strong> of<br />

company towns that inherited, through<br />

urban planning, this combination of<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>try and a supportive environment. 19<br />

That this idea should inspire the great<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>trialists of the period is hardly surprising.<br />

We find Henry Ford promoting his<br />

“seventy-five-mile-long-city” at M<strong>us</strong>cle<br />

Shoals, Alabama, next to a hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ric<br />

development, that would free up “one<br />

million workers” from local tr<strong>us</strong>ts, make<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

fig. 14. street in ArvidA tOdAy. | PhOtOgrAPh by lucie k. mOrisset. fig. 15. street in ArvidA tOdAy. | PhOtOgrAPh by guillAume st-JeAn.<br />

them rich, and in Ford’s words, provide<br />

an opportunity “to eliminate war from<br />

the world.” 20 Frank Lloyd Wright himself<br />

would say in 1922 of the seventy-fivemile-long<br />

city that it was “one of the b<strong>es</strong>t<br />

things” 21 he had ever heard of (fig. 10).<br />

Ford’s Alabama proje<strong>ct</strong> would founder on<br />

Congr<strong>es</strong>s’s ref<strong>us</strong>al to concede Tenn<strong>es</strong>see<br />

River exploitation and development<br />

rights to the company. 22 His next utopian<br />

proje<strong>ct</strong>, Fordlandia, was a<strong>ct</strong>ually built on<br />

a two million he<strong>ct</strong>are parcel of land that<br />

Ford acquired in Brazil. The would-be<br />

rubber-producing megalopolis also ill<strong>us</strong>trat<strong>es</strong><br />

a few gaps in Ford’s grasp of the<br />

reality of urban d<strong>es</strong>ign, as well as perhaps<br />

a certain as yet unr<strong>es</strong>olved discrepancy<br />

between theory and pra<strong>ct</strong>ice. Historians<br />

tend to attribute Ford’s failure in the for<strong>es</strong>ts<br />

of the Amazon to the geographic,<br />

social, and cultural disconne<strong>ct</strong> between<br />

Ford’s American world view and the<br />

tropical wildern<strong>es</strong>s environment, where<br />

his “typically American-as-apple-pie”<br />

wooden ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> produced, it is said, a<br />

most singular impr<strong>es</strong>sion (fig. 11). 23<br />

Although their numbers multiplied in<br />

North America, many of th<strong>es</strong>e town<br />

plans had only a marginal real-life impa<strong>ct</strong>,<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

leaving the landscape littered with, as<br />

one commentator harshly put it, “centr<strong>es</strong><br />

without citi<strong>es</strong>” and “citi<strong>es</strong> without centr<strong>es</strong>.”<br />

Beyond the urban utopias that had<br />

marked the preceding centuri<strong>es</strong> and left<br />

historical if not material trac<strong>es</strong>, the first<br />

years of the American 20th century seem<br />

to have been chara<strong>ct</strong>erized by a phenomenon<br />

of such proportions that a name had<br />

to be created for it: the “paper city.” This<br />

was the work of an ill<strong>us</strong>trator or town<br />

planner commissioned by a company or<br />

group of ind<strong>us</strong>trialists to produce a plan,<br />

not so much to provide workers with better<br />

conditions or found a town, but simply<br />

to entice inv<strong>es</strong>tors with an impr<strong>es</strong>sive layout.<br />

Shawinigan, Quebec, home of compani<strong>es</strong><br />

such as the Pittsburgh Redu<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

Company (later Aluminum Company of<br />

America), Shawinigan Water and Power<br />

Company, and Belgo Canadian Pulp<br />

Company, remained for the most part j<strong>us</strong>t<br />

such a paper city: the plans ordered by the<br />

Shawinigan Water and Power Company<br />

and magnificently repr<strong>es</strong>ented in a bird’seye<br />

view to impr<strong>es</strong>s the ele<strong>ct</strong>ricity-<strong>us</strong>ing<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>try never to that extent saw the light<br />

of day (fig. 12). Other comparable proje<strong>ct</strong>s<br />

ran up against changed material circumstanc<strong>es</strong><br />

with the rising pric<strong>es</strong> of the First<br />

World War: the plans for Allwood, New<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

Jersey, (1917) where ind<strong>us</strong>trialist and philanthropist<br />

William Lyall promised an ideal<br />

city in which both unskilled and skilled<br />

workers would have acc<strong>es</strong>s to hom<strong>es</strong>,<br />

parks, and community servic<strong>es</strong> d<strong>es</strong>igned<br />

by the most prominent town planners<br />

of the period (notably John Nolen,<br />

Morris Knowl<strong>es</strong>, William Somerville, and<br />

George B. Post), was th<strong>us</strong> famo<strong>us</strong>ly abandoned<br />

after the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion of only a few<br />

ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong>, funds having been exha<strong>us</strong>ted. 24<br />

Similarly, plans for Eclipse Park in Beloit,<br />

announced in 1917 by the Fairbanks<br />

Morse Company as a new city of 40,000,<br />

styled as the “Typically American Garden<br />

Village” and noted by critic Lawrence<br />

Veiller for its forty different models of<br />

luxurio<strong>us</strong> ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> (fig. 13), was reduced<br />

before constru<strong>ct</strong>ion began to a neighbourhood<br />

of about 300 ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> r<strong>es</strong>erved<br />

for white employe<strong>es</strong> only. Only 80 were<br />

eventually built. 25<br />

The situation of Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, which<br />

Garnier himself qualified as “imagination<br />

sans réalité” (“not real”), is th<strong>us</strong> hardly<br />

unique, at least in its stat<strong>us</strong> as paper city—<br />

insofar as the term can even be applied.<br />

By expanding the frame of reference<br />

beyond the heritage of European archite<strong>ct</strong>ural<br />

d<strong>es</strong>ign through which Garnier’s<br />

9

10<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 16. street in AlcOA, tenn<strong>es</strong>see, circA 1920. | blOunt cOunty geneAlOgicAl And histOricAl sOciety.<br />

fig. 17. lAyOut fOr ArvidA fA<strong>ct</strong>Ori<strong>es</strong> As built in 1929. the first fOur POtrOOms<br />

brOught On streAm cAn be seen b<strong>es</strong>ide the ele<strong>ct</strong>rOde fA<strong>ct</strong>Ory tO the<br />

sOuth. the slAg Ore PlAnt is At the lOwer right. within 15 yeArs, the<br />

smelter, cOnscriPted fOr the wAr effOrt, exPAnded tO OccuPy All the<br />

sPAce set Aside fOr it here. the slAg Ore (dry PrOc<strong>es</strong>s) PlAnt hAd by then<br />

been cOnverted tO A bAyer refinery. it wAs d<strong>es</strong>igned AccOrding tO PlAns<br />

by Archite<strong>ct</strong> JAm<strong>es</strong> curzey meAdOwcrOft And equiPPed with söderbergh<br />

POtrOOms, the mOst mOdern tyPe Of their time. | riO tintO AlcAn (mOntreAl).<br />

vision has traditionally been interpreted,<br />

we see it clearly as a creature of its time: a<br />

one-off encounter between social utopia,<br />

urban planning, and modern ind<strong>us</strong>try. It is<br />

true that as late as 1918, one of the “fathers”<br />

of ind<strong>us</strong>trial urban d<strong>es</strong>ign, Thomas<br />

Adams, known from the national city<br />

planning conferenc<strong>es</strong> where he served<br />

as the first secretary of the Garden City<br />

Association before emigrating from<br />

Great Britain to found the Town Planning<br />

Institute of Canada, wrote that “We have<br />

not failed to build whol<strong>es</strong>ome ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

communiti<strong>es</strong>; we have not tried to build<br />

them.” 26 Was this an implicit r<strong>es</strong>ponse to<br />

Garnier’s proposal? An indire<strong>ct</strong> acknowledgment<br />

that Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle was yet<br />

to come? Let <strong>us</strong> continue our explorations<br />

on either side of the Atlantic and<br />

outside the admittedly dated modernist<br />

historiography. Only a few years later,<br />

this “not real” city was nothing of the<br />

sort. It took form as what the French<br />

urban d<strong>es</strong>ign historian Pierre Lavedan<br />

would d<strong>es</strong>cribe in 1956 as “the aluminum<br />

city,” a full-fledged example of a “fa<strong>ct</strong>ory<br />

city,” with the layout “of the fre<strong>es</strong>t possible<br />

d<strong>es</strong>ign.” 27 This is the Canadian city<br />

of Arvida, long recognized in the United<br />

Stat<strong>es</strong> as the “most outstanding social<br />

achievement” 28 of one of the rich<strong>es</strong>t and<br />

most a<strong>ct</strong>ive ind<strong>us</strong>trialists in 20th century<br />

America: Arthur Vining Davis, pr<strong>es</strong>ident of<br />

the Aluminum Company of America from<br />

1910 to 1957, who also provided the anagram<br />

for its name out of the first two letters<br />

of his three nam<strong>es</strong>. This “Washington<br />

of the North” and “Jewel of the North<br />

Canada Steppe” was already a model city<br />

from its beginnings and quickly became<br />

“famo<strong>us</strong> as an example of community<br />

ho<strong>us</strong>ing” 29 (figs. 14-15). The promise made<br />

fig. 18. drAwing by JOhn richArd rOwe Of the shiPshAw POwer stAtiOn, nOw<br />

knOwn As chute-à-cArOn, Published in the mAgAzine Pencil POints<br />

in Aug<strong>us</strong>t 1929. it wAs the first POwer PlAnt built by the Aluminum<br />

cOmPAny Of cAnAdA. the PlAns were by the Pittsburgh Archite<strong>ct</strong>s bennO<br />

JAnssen And williAm yOrk cOcken. it wAs inAugurAted in 1931.<br />

in announcing its creation, expr<strong>es</strong>sed in<br />

the Journal of the Town Planning Institute<br />

of Canada as “an opportunity to create a<br />

town which will meet the ideal of perfe<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

which all town planners cherish,” was<br />

for once kept.<br />

Th<strong>us</strong> even as Ford was abandoning his<br />

seventy-five-mile-long-city for wont of<br />

hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ricity to power his ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

utopia, Davis was acquiring “1,340,000<br />

horsepower [100 000 kW] of probably<br />

the cheap<strong>es</strong>t hydro-ele<strong>ct</strong>ric power on the<br />

North American continent” 30 on Quebec’s<br />

Saguenay River. Fr<strong>es</strong>h from his experience<br />

in Alcoa, Tenn<strong>es</strong>see, where the Aluminum<br />

Company of America had, beginning in<br />

1919, built 700 ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> in three years<br />

and, as earlier in Badin, North Carolina,<br />

where he ca<strong>us</strong>ed a sensation by including<br />

ho<strong>us</strong>ing for black workers (fig. 16),<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

fig. 19. isle-mAligne POwer PlAnt As seen in 1938. PlAns by engineer w.s. lee.<br />

it wAs the Aluminum cOmPAny Of AmericA’s first in the sAguenAy–lAcsAint-JeAn<br />

AreA. | librAry And Archiv<strong>es</strong> cAnAdA.<br />

Davis wanted to break new ground, taking<br />

to new and even greater heights the<br />

company he had built into an enormo<strong>us</strong><br />

multinational and world’s larg<strong>es</strong>t producer<br />

of aluminum. Arvida was to be the<br />

company’s first aluminum plant in virgin<br />

territory, 31 a “longed-for opportunity<br />

to begin at the beginning,” 32 as the<br />

planning journal d<strong>es</strong>cribed it. As such, it<br />

was provided with an un<strong>us</strong>ual array of<br />

servic<strong>es</strong>: together with the school system<br />

and cultural, social, and sports a<strong>ct</strong>iviti<strong>es</strong><br />

extensively cited by commentators, it<br />

employed from the beginning a convincing<br />

reformist discourse and an egalitarian<br />

vision that disavowed the social<br />

and racial segregation typical of company<br />

towns. The Aluminum Company of<br />

America pr<strong>es</strong>ident’s attachment to Arvida<br />

has been well documented by historians<br />

and is att<strong>es</strong>ted by a number of contemporary<br />

sourc<strong>es</strong>: Edwin S. Fick<strong>es</strong>, the<br />

company’s chief engineer, sent to the<br />

Saguenay to oversee the city’s constru<strong>ct</strong>ion,<br />

recalled Davis’s unflinching d<strong>es</strong>ire<br />

to “make it a d<strong>es</strong>irable place in which<br />

to live at reasonable cost. Mr. Davis […]<br />

properly insisted that no pains should be<br />

spared to this end.” 33 Davis also said he<br />

wanted to build a tower from which he<br />

could look out over his model city. This is<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

hardly surprising: around the integrated<br />

smelter, where incidentally he aimed not<br />

only to reduce aluminum in some forty<br />

potrooms, but also to employ a new<br />

and experimental proc<strong>es</strong>s to extra<strong>ct</strong> and<br />

refine local bauxite (fig. 17), he had laid<br />

out a “new city” without precedent on<br />

North American soil, where everything,<br />

from streetlights to worker ho<strong>us</strong>ing, had<br />

been planned out and elegantly diagrammed<br />

to the last detail (fig. 18). The<br />

scale of this ind<strong>us</strong>trial utopia invariably<br />

evok<strong>es</strong> another: Garnier’s, and not merely<br />

in their shared hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ric plant, transoceanic<br />

port, and metallurgical produ<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

facility to refine local ore.<br />

“a city built in 135 days, without<br />

ever having known the slums and<br />

uglin<strong>es</strong>s of haphazard growth,<br />

and where the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

required no tearing down” 34<br />

– Harold Wake, arvida constru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

superintendent<br />

Located j<strong>us</strong>t upstream from the hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ric<br />

station that prefigured its creation,<br />

the most powerful in the world<br />

at the time (fig. 19), and n<strong>es</strong>tled around<br />

its smelter, Arvida was typical of North<br />

America company towns in that it was<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 20. birdseye view Of the “quArtier d<strong>es</strong> AnglAis” in kénOgAmi,<br />

ArOund 1920. | bibliOthèque et Archiv<strong>es</strong> nAtiOnAl<strong>es</strong> du québec.<br />

d<strong>es</strong>igned to ho<strong>us</strong>e workers for an ind<strong>us</strong>trial<br />

operation. In the immediate region,<br />

Arvida is a succ<strong>es</strong>sor to Val-Jalbert (1899),<br />

Kénogami (1912), Port-Alfred (1915),<br />

Riverbend (1923), and Dolbeau (1927)<br />

(fig. 20). But j<strong>us</strong>t as Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle stands<br />

apart from the utopias that preceded it,<br />

Arvida’s r<strong>es</strong>emblance to ordinary company<br />

towns ends there. It differs in its planning<br />

and r<strong>es</strong>ulting urban forms as well as in its<br />

layout and landscaping and in the way it<br />

came into being as a constru<strong>ct</strong>ion proje<strong>ct</strong><br />

unprecedented in method and scale to<br />

produce a genuine model city providing<br />

workers with an incomparable habitat—<br />

one of the high points of archite<strong>ct</strong>ural<br />

history. The town also stands out for its<br />

marvello<strong>us</strong> state of pr<strong>es</strong>ervation. It was<br />

meticulo<strong>us</strong>ly prote<strong>ct</strong>ed by its parent company,<br />

the Aluminum Company of America<br />

and its subsidiary the Aluminum Company<br />

of Canada, later Alcan, well beyond the<br />

1940s and 50s, when Arvida, world aluminum<br />

capital, would join the pantheon<br />

of ind<strong>us</strong>trial citi<strong>es</strong>, j<strong>us</strong>t as it became one<br />

of the most closely guarded secrets of<br />

the British Commonwealth and one of<br />

Canada’s b<strong>es</strong>t prote<strong>ct</strong>ed sit<strong>es</strong>, producing<br />

the very “flying vehicl<strong>es</strong>” imagined by<br />

Garner and crucial to the outcome of the<br />

Second World War.<br />

11

12<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 21. Attributed tO hJAlmAr e. skOugOr, cOlOur lithOgrAPh Of the ArvidA PlAn, 1925-1926. | ville de sAguenAy.<br />

fig. 22. scAle mOdel Of ArvidA, 1925-1926: this mOdel is like A three-dimensiOnAl trAnsPOsitiOn Of cité<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, with its r<strong>es</strong>identiAl AreA, dOwntOwn, smelter, hydrOele<strong>ct</strong>ric fAciliti<strong>es</strong>, And river.<br />

the “Old tOwn” (the ind<strong>us</strong>triAl tOwn Of kénOgAmi) is seen tO the left neAr the OutflOw Of A smAll<br />

ind<strong>us</strong>triAl building PrObAbly rePr<strong>es</strong>enting A PulP mill. | sOciété histOrique du sAguenAy, PhOtOgrAPh by PAul lAliberté.<br />

Arvida was <strong>es</strong>sentially built in three<br />

broad phas<strong>es</strong>: 1925 to 1935, 1936 to 1942,<br />

and the period up to 1950. Carved out<br />

of the natural surroundings it absorbed,<br />

it shar<strong>es</strong> more than a few similariti<strong>es</strong><br />

with Garnier’s Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle: the two<br />

proje<strong>ct</strong>s are both “total citi<strong>es</strong>,” from<br />

the street layout and fun<strong>ct</strong>ional zoning<br />

all the way down to the d<strong>es</strong>ign of<br />

each ho<strong>us</strong>e. Garnier and the Aluminum<br />

Company of America both conjured<br />

an urban centre glittering with lavish<br />

buildings and imposing avenu<strong>es</strong>, yet<br />

dedicated to the efficient operation of a<br />

prospero<strong>us</strong> metallurgical ind<strong>us</strong>try fuelled<br />

by massive hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ric development.<br />

Like Garnier’s “not real” creation,<br />

Arvida’s legacy includ<strong>es</strong> an outstanding<br />

documentary record pr<strong>es</strong>erving not j<strong>us</strong>t<br />

the plans for, but also the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

of the city. Arvida’s records are in fa<strong>ct</strong><br />

far more extensive. They include some<br />

2,000 sheets of plans; high-quality drawing;<br />

hundreds of films, photographs, brochur<strong>es</strong>,<br />

newspaper and journal article;<br />

meeting records; a number of th<strong>es</strong><strong>es</strong><br />

and historical r<strong>es</strong>earch papers; a variety<br />

of contemporaneo<strong>us</strong> reports; and a<br />

relatively abundant corr<strong>es</strong>pondence, all<br />

ho<strong>us</strong>ed in a dozen or more archival colle<strong>ct</strong>ions<br />

in Canada and the United Stat<strong>es</strong>.<br />

It is th<strong>es</strong>e records, along with the city<br />

as it exists today, that have served as<br />

our guid<strong>es</strong> through this epic of urban<br />

planning, of which this article maps out<br />

some of the high points. In addition to<br />

a lithographed and published overall<br />

plan in black and white and in colour<br />

(fig. 21), there is a model ill<strong>us</strong>trating<br />

the scale of the proje<strong>ct</strong>. It depi<strong>ct</strong>s a city<br />

harn<strong>es</strong>sing the river torrents and spreading<br />

out across the benchlands above the<br />

river, not far from the older settlements<br />

of Jonquière and Kénogami (fig. 22).<br />

Arvida, again like Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, would<br />

be conne<strong>ct</strong>ed to th<strong>es</strong>e settlements as<br />

well as to raw material produ<strong>ct</strong>ion and<br />

distribution networks by a railway running<br />

along the plain, linking the gigantic<br />

smelter to transoceanic port and lavish<br />

city, running like clockwork and lovely<br />

as a work of art.<br />

Is there any conne<strong>ct</strong>ion other than mere<br />

providence linking Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle to<br />

Arvida? What did Arvida’s creators know<br />

of their imaginary predec<strong>es</strong>sor’s author?<br />

the French conne<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

While Lyon in the 1910s was a hub for city<br />

planning ideas, 35 the flow and exchange<br />

of information between North America,<br />

Europe, and France was increasing in the<br />

days of Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle and Arvida, particularly<br />

in the specialized and relatively<br />

circumscribed field of town and city<br />

planning. One of the first to publish the<br />

lithographed plan for Arvida was in fa<strong>ct</strong> a<br />

German city planner, Werner Hegemann,<br />

who immigrated to New York City in 1933<br />

and whose transatlantic travels were the<br />

subje<strong>ct</strong> of an important <strong>es</strong>say. 36 Also<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

fig. 23. AeriAl view Of bAdin, nOrth cArOlinA, POst-1920, On the site PreviO<strong>us</strong>ly<br />

identified by the french cOmPAny And its subsidiAry, the sOuthern<br />

Aluminum cOmPAny, fOr An Aluminum smelter Of unPrecedented size.<br />

see the “quAdrAPlex<strong>es</strong>”, As they Are nAmed there, d<strong>es</strong>igned fOr the<br />

french cOmPAny, POssibly by new yOrk’s engineers PiersOn And gOOdrich.<br />

they becAme tyPicAl lOcAlly d<strong>es</strong>Pite being mOre chArA<strong>ct</strong>eristic Of the<br />

semidetAched hO<strong>us</strong>ing Of eurOPeAn ind<strong>us</strong>triAl tOwns. the Aluminum<br />

cOmPAny Of AmericA d<strong>es</strong>cribed them As “nOt gOOd As hO<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong>, nOr the<br />

tyPe thAt the cOmPAny wished tO PrOvide fOr its emPlOye<strong>es</strong>.” | AlcOA Archiv<strong>es</strong>,<br />

histOricAl sOciety Of w<strong>es</strong>tern PennsylvAniA Archiv<strong>es</strong>, librAry And Archiv<strong>es</strong> divisiOn, heinz histOry<br />

center, Pittsburgh (PA).<br />

fig. 24. OrthOgrAPhic view Of the mAriA elenA mine And tOwn, built in chile by<br />

the guggenheim brOthers AccOrding tO PlAns by hArry b. brAinerd And<br />

hJAlmAr e. skOugOr, 1926. | digitAl glObe/gOOgle.<br />

notable was the path followed by Thomas<br />

Adams 37 —the manager of Letchworth,<br />

the “first” Garden City—who, in addition<br />

to founding the Town Planning<br />

Institute of Canada (1914) and managing<br />

the New York Regional plan (1923-1930),<br />

also d<strong>es</strong>igned several new towns before<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

returning to Great Britain to found the<br />

Institute of Landscape Archite<strong>ct</strong>s (1937).<br />

The travels of French archite<strong>ct</strong> Jacqu<strong>es</strong><br />

Gréber are similarly familiar: known<br />

mainly in his own country as the master<br />

archite<strong>ct</strong> of the 1937 Paris International<br />

Exhibition, Gréber crisscrossed the<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 25. reduced PlAn fOr ecliPse PArk (belOit, wi), geOrge b. POst And sOns, As<br />

Published in 1918 by lAwrence veiller in the mAgAzine Archite<strong>ct</strong>urAl<br />

recOrd. the cOntOur street system, which wAs beginning tO sPreAd At the<br />

time, wAs <strong>us</strong>ed here. the PArt Of the PlAn tO the left Of the mOnumentAl<br />

centrAl Axis wAs never built: A shOPPing centre And PArking lOt ended<br />

uP OccuPying thAt AreA.<br />

fig. 26. “AirPOrt-dOcks fOr new yOrk,” hArry b. brAinerd, Archite<strong>ct</strong>: A PrOPOsAl fOr<br />

An intermOdAl POrt next tO the city tO fAcilitAte Acc<strong>es</strong>s tO intercity trAns-<br />

POrtAtiOn, PArticulArly the new AirPlAn<strong>es</strong>. | science And mechAnics, nOvember 1931.<br />

northeastern United Stat<strong>es</strong> from 1910<br />

on. 38 He was a ubiquito<strong>us</strong> ve<strong>ct</strong>or of contamination,<br />

turning his observations into<br />

a monumental work, published in 1920<br />

under the title “Archite<strong>ct</strong>ure in the United<br />

Stat<strong>es</strong>, with the curio<strong>us</strong> subtitle “Evidence<br />

of the expansion capability of the French<br />

13

14<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 27. Attributed tO hArry beArdslee brAinerd, “PersPe<strong>ct</strong>ive Of b<strong>us</strong>in<strong>es</strong>s distri<strong>ct</strong>, tOwn Of ArvidA PrOvince<br />

Of quebec, cAnAdA, 1926.” As in gArnier’s cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, the “mOst imPOrtAnt street OriginAt<strong>es</strong> At<br />

the trAin stAtiOn” And “the neighbOurhOOd ArOund the trAin stAtiOn is r<strong>es</strong>erved PrimArily fOr […]<br />

hOtels, dePArtment stOr<strong>es</strong>, etc., sO thAt the r<strong>es</strong>t Of the tOwn cAn be free Of tAll buildings.” | riO tintO<br />

AlcAn (sAguenAy).<br />

geni<strong>us</strong>.” 39 Although we find scarcely any<br />

signs of French urban d<strong>es</strong>ign proje<strong>ct</strong>s<br />

migrating to American soil, the chapter<br />

“Community Ho<strong>us</strong>ing: Garden Citi<strong>es</strong>,<br />

Worker Citi<strong>es</strong>” 40 disc<strong>us</strong>s<strong>es</strong> the “methodical<br />

organization” 41 of planning with r<strong>es</strong>pe<strong>ct</strong><br />

to certain aspe<strong>ct</strong>s that, as we shall see,<br />

are particularly significant to our story:<br />

thanks to powerful means of produ<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

in the service of flawl<strong>es</strong>s methods of<br />

organization, Americans have, in recent<br />

years, made enormo<strong>us</strong> strid<strong>es</strong> in the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

of economical ho<strong>us</strong>ing for large<br />

groups. they have mass-produced not the<br />

ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong> themselv<strong>es</strong>, but the materials for<br />

constru<strong>ct</strong>ing them, making it possible to<br />

standardize rationally without monotony. 42<br />

We note incidentally that Gréber,<br />

Adams, and Edward Bennett, coauthor<br />

of the 1909 Plan of Chicago (in which<br />

many have pointed out French influenc<strong>es</strong><br />

43 ), Noulan Cauchon, who would<br />

give a notable talk in Arvida itself, 44 and<br />

Frederick G. Todd, student of Frederick<br />

Law Olmsted and inaugural chair of the<br />

Arvida Planning Committee, with which<br />

he completed a number of landscape<br />

archite<strong>ct</strong>ure proje<strong>ct</strong>s in the 1940s, had, if<br />

not nec<strong>es</strong>sarily become fast friends, certainly<br />

met around the drafting table at<br />

Canada’s Federal Distri<strong>ct</strong> Commission, 45<br />

where they worked together planning<br />

the City of Ottawa.<br />

Could the idea found in Une cité ind<strong>us</strong>‑<br />

trielle, either prior or subsequent to<br />

Garnier’s publication, have followed such<br />

channels?<br />

In the relatively globalized sphere of<br />

r<strong>es</strong>ource ind<strong>us</strong>tri<strong>es</strong>, and <strong>es</strong>pecially aluminum—that<br />

“magic metal of the 20th century”<br />

whose lightn<strong>es</strong>s and condu<strong>ct</strong>ivity<br />

held such immense promise if only the<br />

tremendo<strong>us</strong> amounts of energy required<br />

for reducing the metal through ele<strong>ct</strong>rolysis<br />

could be secured—American<br />

and French inter<strong>es</strong>ts had crossed paths<br />

more than once. In 1915, the Aluminum<br />

Company of America took over faciliti<strong>es</strong><br />

in North Carolina built from 1911 under<br />

the stewardship of Adrien Badin, dire<strong>ct</strong>or<br />

of Compagnie d<strong>es</strong> produits chimiqu<strong>es</strong><br />

d’Alais et de la Camargue (later known<br />

as Pechiney). Badin had also been mayor<br />

of the first aluminum-producing town<br />

of Salindr<strong>es</strong>, where Pechiney was <strong>es</strong>tablished,<br />

some 250 kilometr<strong>es</strong> downstream<br />

from Lyon, at the same time that Garnier’s<br />

patron, Édouard Herriot, was mayor there,<br />

and also headed Aluminium Français, the<br />

cartel he had launched to bring together<br />

France’s five aluminum compani<strong>es</strong>, and its<br />

subsidiary Southern Aluminum Company,<br />

<strong>es</strong>tablished in the United Stated in 1912. 46<br />

The North Carolina town was named<br />

Badinville or Badin, and its similariti<strong>es</strong><br />

to Garnier’s Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle are striking,<br />

including, considering the change<br />

the proje<strong>ct</strong> underwent, 47 the location of<br />

its dam, hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ric station, aluminum<br />

smelter, and r<strong>es</strong>idential distri<strong>ct</strong> (fig. 23).<br />

Noteworthy aspe<strong>ct</strong>s include the townsite’s<br />

location on a plateau, its position<br />

above the smelter, its relationship to the<br />

nearby older settlement of Palmerville<br />

echoing Cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle’s “ville ancienne”<br />

(“old town”) repr<strong>es</strong>ented by Garnier<br />

and the granite min<strong>es</strong> acquired by the<br />

Southern Aluminum Company near the<br />

townsite. 48 (“There are also min<strong>es</strong> in the<br />

region,” 49 Garnier had written). A number<br />

of particulariti<strong>es</strong> still found in Badin also<br />

belong more to Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle and its<br />

European context than to town planning<br />

in the United Stat<strong>es</strong>: amongst them, the<br />

quadraplex<strong>es</strong> built by the French company<br />

to ho<strong>us</strong>e its employe<strong>es</strong>, <strong>us</strong>ual in Europe, 50<br />

but very uncommon in America, and<br />

pathways through lots, between ho<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong>,<br />

or, as Garnier wrote:<br />

[…] the built area m<strong>us</strong>t always be l<strong>es</strong>s<br />

than half the total surface area, the r<strong>es</strong>t<br />

of the lot becoming a public garden for ped<strong>es</strong>trians;<br />

that is, each building m<strong>us</strong>t leave<br />

on the unbuilt part of its lot an unimpeded<br />

passage from the street to the building<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011

situated at the back. this arrangement<br />

allows circulation through town in any dire<strong>ct</strong>ions<br />

independent of the streets which<br />

one no longer needs follow; the land of the<br />

town as a whole is like a large park, with no<br />

enclosing walls to limit the ground. 51<br />

Was Garnier familiar with the Aluminium<br />

Français undertaking together with<br />

France’s leading ind<strong>us</strong>trial compani<strong>es</strong>,<br />

which promised, specifically through this<br />

Yadkin River settlement, to make France<br />

the world’s leading aluminum producer,<br />

52 and has been d<strong>es</strong>cribed as “probably<br />

the larg<strong>es</strong>t, and most ambitio<strong>us</strong>,<br />

French Inv<strong>es</strong>tment in pre-World War I<br />

America” 53 ? Given that the Aluminum<br />

Company of America itself undertook<br />

to build in Badin a model city remarkable<br />

in many regards, and that Arthur<br />

Vining Davis and Adrien Badin communicated<br />

with each other, 54 is it possible<br />

to conje<strong>ct</strong>ure that the ideals of<br />

Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle circulated on the North<br />

American frontier—and made their way<br />

from Aluminium Français to Arvida?<br />

In addition to the likely interse<strong>ct</strong>ion<br />

of the spher<strong>es</strong> of influence of Adrien<br />

Badin, with his plans to relaunch the<br />

aluminum ind<strong>us</strong>try through a spe<strong>ct</strong>acular<br />

undertaking, and Paul Héroult, the<br />

well-known French inventor of the ele<strong>ct</strong>rolytic<br />

redu<strong>ct</strong>ion proc<strong>es</strong>s, who went to<br />

stay in Whitney to supervise the building<br />

of Badinville, and Garnier, who imagined<br />

the renewal of the planned city under<br />

the aegis of metallurgical ind<strong>us</strong>try and<br />

hydroele<strong>ct</strong>ricity, the similariti<strong>es</strong>, scale,<br />

and contemporaneity of Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle<br />

and its North Carolina co<strong>us</strong>in constitute<br />

convincing circumstantial evidence.<br />

It is likewise unlikely that Garnier was<br />

unaware of North American r<strong>es</strong>ource<br />

towns in general. Could the creators<br />

of Arvida, following as they did in the<br />

footsteps of the Aluminum Company of<br />

America’s settlement built on Badin’s<br />

JSSAC | JSÉAC 36 > N o 1 > 2011<br />

French foundations, likewise have had<br />

conta<strong>ct</strong> with Cité Ind<strong>us</strong>trielle?<br />

In addition to being built under the<br />

supervision of engineering superintendent<br />

Harold R. Wake, who until then had<br />

been managed the company’s real <strong>es</strong>tate<br />

servic<strong>es</strong> in Badin, Vi<strong>ct</strong>or J. Hultquist, who<br />

had performed with distin<strong>ct</strong>ion during<br />

the constru<strong>ct</strong>ion of Alcoa, Tenn<strong>es</strong>see, 55<br />

and Edwin Stanton Fick<strong>es</strong>, who is credited<br />

of a contribution to the town plan<br />

of Alcoa and who from 1901 did about<br />

everything for the company, from building<br />

plants to rethinking the aluminum<br />

produ<strong>ct</strong>ion proc<strong>es</strong>s, Arvida was in 1925-<br />

1926 the work of two main planners.<br />

One, Harry Beardslee Brainerd (1887-<br />

1977), was a New York-based archite<strong>ct</strong>,<br />

theorist, and town planner, known at<br />

the time for having drafted the plans<br />

for the Chilean ind<strong>us</strong>trial town of María<br />

Elena (fig. 24), and noted for his work<br />

developing and t<strong>es</strong>ting theori<strong>es</strong> of the<br />

nascent discipline of city planning in a<br />

number of thoroughfar<strong>es</strong> plans, reports,<br />

and other zoning primers and city plans,<br />

notably for Cleveland, Ohio. 56 During his<br />

town planning apprentic<strong>es</strong>hip with the<br />

firm of Murphy and Dana, he probably<br />

took part in the r<strong>es</strong>idential development<br />

of Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he<br />

became a consulting archite<strong>ct</strong> with the<br />

City Planning Commission in 1927. While<br />

at the New York firm of George B. Post<br />

and Sons, he undoubtedly helped d<strong>es</strong>ign<br />

the paper city of Eclipse Park (Beloit,<br />

Wisconsin) with its forty model dwellings<br />

and its urban layout combining a vast,<br />

solemn mall in the City Beautiful style<br />

and pi<strong>ct</strong>ur<strong>es</strong>que r<strong>es</strong>idential streets gracefully<br />

winding along the topographic contours<br />

(fig. 25), and was noted in 1931 for<br />

proposing an ingenio<strong>us</strong> system of airport<br />

docks for New York City (fig. 26). He had<br />

completed his archite<strong>ct</strong>ural education at<br />

New York’s Columbia <strong>University</strong> where<br />

the library catalogue shows a copy of<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 28. “ArvidA – b<strong>us</strong>in<strong>es</strong>s distri<strong>ct</strong>”: PlAn by hArry<br />

beArdslee brAinerd <strong>es</strong>tAblishing the<br />

dOwntOwn AreA between twO rAvin<strong>es</strong> And<br />

setting Out building dimensiOns And the<br />

ArrAngement Of rOAdwAys, including the<br />

“viAdu<strong>ct</strong> tO cAthedrAl.” | university Of OregOn<br />

librAry, cOlle<strong>ct</strong>iOn richArd hAvilAnd smythe.<br />

fig. 29. PlAn Of chicAgO, PrOPOsed bOulevArd. Jul<strong>es</strong><br />

guérin fOr dAniel hudsOn burnhAm et Al.,<br />

cOmmerciAl club Of chicAgO, 1909.<br />

Garnier’s Une cité ind<strong>us</strong>trielle, first edition,<br />

to which he would have had acc<strong>es</strong>s.<br />

He studied at Columbia under Harvey<br />

Wiley Corbett (1873-1954), who had<br />

graduated from École d<strong>es</strong> beaux-arts de<br />

Paris in 1900 and was th<strong>us</strong> a former colleague<br />

of Garnier, who had received the<br />

Prix de Rome there in 1901.<br />

15

16<br />

Lucie K. Morisset > aNalysis | aNalyse<br />

fig. 30. “PersPe<strong>ct</strong>iv<strong>es</strong>: tOwnsite hO<strong>us</strong><strong>es</strong>,” c2 And c3, Aluminum cOmPAny Of cAnAdA, 1927. | ville de sAguenAy.<br />

The other, Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor,<br />

Brainerd’s partner, is credited with the<br />

lithographed plan of Arvida as well as the<br />