Slaying dragons: limited evidence for unusual body size evolution ...

Slaying dragons: limited evidence for unusual body size evolution ...

Slaying dragons: limited evidence for unusual body size evolution ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

S. Meiri et al.<br />

Insular mean mass (log 10 scale)<br />

(a) (b)<br />

Continental mean mass (log 10 scale)<br />

evenly distributed between continental shelf, volcanic and<br />

continental plate islands (e.g. the Philippines, New Guinea,<br />

Tasmania, Hawaii and New Zealand). This suggests that release<br />

from predation on islands has often promoted gigantism in<br />

lizards and perhaps gigantism associated with flightlessness in<br />

birds (e.g. the New Zealand moas, Sylviornis; Russell, 1877;<br />

McNab, 1994), but perhaps a different mechanism drove<br />

gigantism among birds that retained their power of flight (e.g.<br />

high population density; Blondel, 2000).<br />

Size extremes in insular mammals show no departure from<br />

null expectations. However, mammals con<strong>for</strong>m to the island<br />

rule at the genus level, especially when fossil species are<br />

included. This pattern also emerges when we compare sister<br />

species, a better test of <strong>size</strong> <strong>evolution</strong> than comparing clade<br />

members ignoring their phylogenetic affinities.<br />

In all three taxa, deviations from a slope of 1 seem to stem<br />

from small (mammals and birds) or large (lizards) members of<br />

generally large-bodied <strong>for</strong>ms (e.g. small elephants, artiodactyls,<br />

ratites and ducks, large iguanas). Extinct mammals show the<br />

most drastic cases of dwarfism. However, many of the recently<br />

extinct insular lizards and birds are extremely large (Pregill,<br />

1986; Blondel, 2000) and extinction in these taxa was probably<br />

much more prevalent on islands than on mainlands, whereas<br />

extinctions of large mammals were common in mainland<br />

settings (Barnosky et al., 2004). Thus in early Holocene times<br />

there were giant insular birds in orders now exhibiting an<br />

overall tendency <strong>for</strong> small <strong>size</strong>s on islands. Indeed very large,<br />

recently extinct, insular birds include members of the Falconi<strong>for</strong>mes<br />

(e.g. Amplibuteo, Harpagornis moorei, Circus eylesi;<br />

Worthy et al., 2002; Suárez & Olson, 2007) and Strigi<strong>for</strong>mes<br />

(e.g. Tyto riveroi, Ornimegalonyx oteroi; Alcover & McMinn,<br />

1994), ratites (Dinornis, Aepyornis; Worthy et al., 2002),<br />

Anseri<strong>for</strong>mes (e.g. Cygnus falconeri and the ‘very large Hawaii<br />

goose’; Milberg & Tyrberg, 1993; Paxinos et al., 1999),<br />

Ciconii<strong>for</strong>mes (Threskiornis solitarius, perhaps a Pelecani<strong>for</strong>m;<br />

Mourer-Chauvire et al., 1995), Grui<strong>for</strong>mes (Diaphorapteryx<br />

hawkinsii, perhaps Aptornis; Holdaway, 1989; Raia, 2009),<br />

Galli<strong>for</strong>mes (e.g. Megavitiornis, perhaps Sylviornis; Steadman,<br />

2006) and Columbi<strong>for</strong>mes (Raphus cucullatus, Pezophaps<br />

solitaria, Natunaornis gigoura; Steadman, 2006; Worthy,<br />

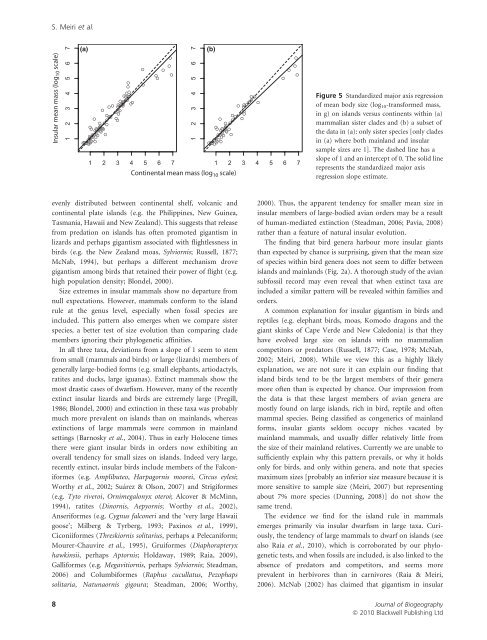

Figure 5 Standardized major axis regression<br />

of mean <strong>body</strong> <strong>size</strong> (log 10-trans<strong>for</strong>med mass,<br />

in g) on islands versus continents within (a)<br />

mammalian sister clades and (b) a subset of<br />

the data in (a): only sister species [only clades<br />

in (a) where both mainland and insular<br />

sample <strong>size</strong>s are 1]. The dashed line has a<br />

slope of 1 and an intercept of 0. The solid line<br />

represents the standardized major axis<br />

regression slope estimate.<br />

2000). Thus, the apparent tendency <strong>for</strong> smaller mean <strong>size</strong> in<br />

insular members of large-bodied avian orders may be a result<br />

of human-mediated extinction (Steadman, 2006; Pavia, 2008)<br />

rather than a feature of natural insular <strong>evolution</strong>.<br />

The finding that bird genera harbour more insular giants<br />

than expected by chance is surprising, given that the mean <strong>size</strong><br />

of species within bird genera does not seem to differ between<br />

islands and mainlands (Fig. 2a). A thorough study of the avian<br />

subfossil record may even reveal that when extinct taxa are<br />

included a similar pattern will be revealed within families and<br />

orders.<br />

A common explanation <strong>for</strong> insular gigantism in birds and<br />

reptiles (e.g. elephant birds, moas, Komodo <strong>dragons</strong> and the<br />

giant skinks of Cape Verde and New Caledonia) is that they<br />

have evolved large <strong>size</strong> on islands with no mammalian<br />

competitors or predators (Russell, 1877; Case, 1978; McNab,<br />

2002; Meiri, 2008). While we view this as a highly likely<br />

explanation, we are not sure it can explain our finding that<br />

island birds tend to be the largest members of their genera<br />

more often than is expected by chance. Our impression from<br />

the data is that these largest members of avian genera are<br />

mostly found on large islands, rich in bird, reptile and often<br />

mammal species. Being classified as congenerics of mainland<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms, insular giants seldom occupy niches vacated by<br />

mainland mammals, and usually differ relatively little from<br />

the <strong>size</strong> of their mainland relatives. Currently we are unable to<br />

sufficiently explain why this pattern prevails, or why it holds<br />

only <strong>for</strong> birds, and only within genera, and note that species<br />

maximum <strong>size</strong>s [probably an inferior <strong>size</strong> measure because it is<br />

more sensitive to sample <strong>size</strong> (Meiri, 2007) but representing<br />

about 7% more species (Dunning, 2008)] do not show the<br />

same trend.<br />

The <strong>evidence</strong> we find <strong>for</strong> the island rule in mammals<br />

emerges primarily via insular dwarfism in large taxa. Curiously,<br />

the tendency of large mammals to dwarf on islands (see<br />

also Raia et al., 2010), which is corroborated by our phylogenetic<br />

tests, and when fossils are included, is also linked to the<br />

absence of predators and competitors, and seems more<br />

prevalent in herbivores than in carnivores (Raia & Meiri,<br />

2006). McNab (2002) has claimed that gigantism in insular<br />

8 Journal of Biogeography<br />

ª 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd