Hispanic Hispanic los hispanos - The Sacramento Bee

Hispanic Hispanic los hispanos - The Sacramento Bee

Hispanic Hispanic los hispanos - The Sacramento Bee

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

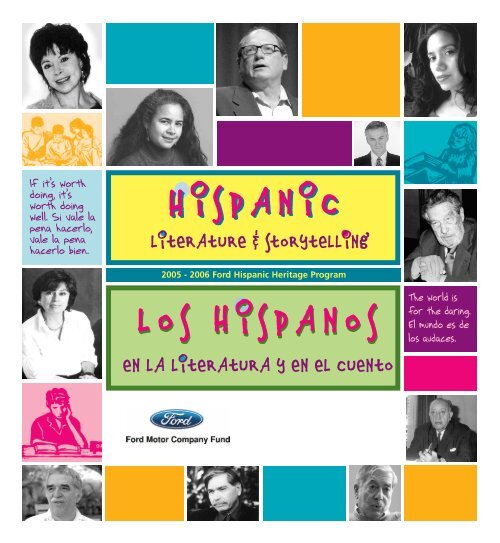

If it’s worth<br />

doing, it’s<br />

worth doing<br />

well. Si vale la<br />

pena hacerlo,<br />

vale la pena<br />

hacerlo bien.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong><br />

literature & storytelling<br />

2005 - 2006 Ford <strong>Hispanic</strong> Heritage Program<br />

<strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong><br />

en la literatura y en el cuento<br />

<strong>The</strong> world is<br />

for the daring.<br />

El mundo es de<br />

<strong>los</strong> audaces.

2<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

Introduction By Gloria Rodriguez<br />

As the writer Earl Shorris says, “Although anyone may<br />

speak two languages, no man or woman, no child, can<br />

dream in more than one.”<br />

In this publication you will find the stories of men and<br />

women who have written and in many cases continue<br />

to write in the beautiful Spanish of their native lands,<br />

and whose work has jumped the language barrier to<br />

appear in English translations, making them famous in<br />

this country and throughout the world. I invite you, the<br />

young readers of these pages, to enjoy their stories, to<br />

continue learning more about these authors and, hopefully,<br />

to dream in the language of your choice.<br />

Isabel Allende is one of my favorite authors. All her<br />

books, including <strong>The</strong> House of the Spirits, Of Love and<br />

Shadows and Eva Luna, which are based on life in Chile,<br />

her native country, are available in both the original<br />

Spanish and in English translations. So is <strong>The</strong> Infinite<br />

Plan, her first novel set in the United States with<br />

American characters. I particularly liked My Invented<br />

Country, in which she portrays the Chile of her youth<br />

and recalls how her grandfather inspired her to be a<br />

writer. Young readers will enjoy Zorro, a novel about<br />

the dashing and legendary character set in California,<br />

where Allende now makes her home.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are authors who were born in Latin America and<br />

now live in our country, writing in English. Cristina<br />

Garcia was born in Havana, Cuba, grew up and studied<br />

in New York City and<br />

has worked as a journalist<br />

in San Francisco,<br />

Miami and Los Angeles.<br />

She is “blessed with a<br />

poet’s ear for language,<br />

a historian’s fascination<br />

with the past and a<br />

musician’s intuitive<br />

understanding of the<br />

ebb and flow of emotion”,<br />

according to<br />

Michiko Kakutani,<br />

writing in <strong>The</strong> New York<br />

Times about Garcia’s<br />

first novel, Dreaming in<br />

Cuban, which I enjoyed<br />

very much. This is a<br />

novel of four women,<br />

both past and present,<br />

each with a different phi<strong>los</strong>ophy of life and personality<br />

yet bound together by their love of each other. It is<br />

written in a dream-like lyrical quality, and we become<br />

enraptured through the different voices. This leads us<br />

to the appreciation of community history and the<br />

forging of communal bonds, which are acquired first<br />

through the immediate family and then the larger<br />

gender and cultural group.<br />

Mexican American fiction writer Sandra Cisneros loves<br />

to engage in cultural controversy — and I love her for<br />

it! In one of her most well known books, National Book<br />

Award winner <strong>The</strong> House on Mango Street (1984), she<br />

Gloria Rodriguez (far right) with<br />

her family – Four generations of<br />

the Rodriguez family<br />

writes: “One day I’ll own my own house, but I won’t<br />

forget who I am or where I come from.” In 1997 she<br />

proved it by painting her historic San Antonio, Texas,<br />

house neon purple in violation of the city’s historic<br />

preservation code, claiming the bright color as a key<br />

part of her Mexican heritage. Sandra is part of the<br />

Smithsonian Institution exhibition “Our Journeys/Our<br />

Stories,” which is made possible by Ford Motor<br />

Company. This exhibition also highlights other Latino<br />

writers such as journalist John Quiñones.<br />

Dominican American novelist Julia Alvarez writes in<br />

Something To Declare, a collection of personal essays,<br />

quoting fiction writer Robert Stone’s observation that<br />

“writing is how we take care of the human family” and<br />

that ”it is through writing that I give myself to a much<br />

larger familia than my own.” I love Alvarez’s novels,<br />

especially Yo, because they symbolize the current generation<br />

of <strong>Hispanic</strong> American writers that are very much<br />

caught up with la familia. Born in New York City to<br />

Dominican parents, Alvarez writes scenes and sensibilities<br />

linked to her own history. Yo is a rambunctious<br />

story revisiting the Garcia family of her first book How<br />

the Garcia Girls Lost <strong>The</strong>ir Accents and talking about<br />

dual existence and conflicting experiences. As a writer<br />

inhabiting two cultures she transcends cultural boundaries<br />

through dominating her craft of writing.<br />

As you develop a taste for good writing, be sure to read<br />

Gabriel García Márquez. Among the Latin Americans<br />

who have won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he is the<br />

only one alive today. His famous novel, One Hundred<br />

Years of Solitude, the story of the Buendía family in the<br />

mythical town of Macondo, is a groundbreaking work<br />

in the style called magical realism that has been followed<br />

by many authors in Latin America and in other<br />

regions of the world.<br />

Fame and recognition beyond the borders of their<br />

birthplaces is not new for <strong>Hispanic</strong> authors. Latin<br />

America has been lavish in the creation of poets. Five<br />

men born in the 19th century are still remembered<br />

today as the leading figures of Modernism, the literary<br />

movement that paved the way for less elaborate forms<br />

of poetry. <strong>The</strong>y are José Martí (Cuba), José Asunción<br />

Silva (Colombia), Rubén Darío (Nicaragua), Amado<br />

Nervo (Mexico) and Leopoldo Lugones (Argentina.) I<br />

also love the poems of the Chileans Gabriela Mistral<br />

and Pablo Neruda, who together with Miguel Ángel<br />

Asturias, of Guatemala, are Nobel Prize winners.<br />

We have a rich <strong>Hispanic</strong> heritage in the United States,<br />

and Spanish literature, the old and the new, is a most<br />

important part of this legacy. We have an impressive<br />

diversity of voices, yet there exists a bond of recognition,<br />

a family camaraderie if you will! It is through literature<br />

that two worlds, two cultures, come together and<br />

strive for mutual understanding. While we may speak<br />

with different accents and use different expressions, we<br />

all share the experience of dual lives and the ability to<br />

communicate and, more importantly, to think and feel<br />

in more than one language. Poets and writers will not<br />

be confined by language, geography, or politics. We<br />

have much to learn from them.<br />

In one of his Versos Sencil<strong>los</strong>, José Martí put it very well,<br />

and I offer you his words in the original:<br />

Yo vengo de todas partes,<br />

y hacia todas partes voy:<br />

arte soy entre las artes,<br />

en <strong>los</strong> montes, monte soy.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Heritage Month<br />

This national celebration, which started in 1968 as a week-long remembrance, marks many important events<br />

that took place in September and October. It kicks off Sept. 15, a time when several Spanish-speaking nations<br />

gained their independence. It ends Oct. 15, following the Día de la Raza (Day of Our Race) on Oct. 12, a celebration<br />

of heritage for many Latin Americans.

Los Hispanos en la literatura y en el cuento 3<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN Por Gloria Rodriguez<br />

Como dice el autor Earl Shorris: “Aunque cualquiera<br />

puede hablar dos idiomas, ningún hombre, mujer o<br />

niño puede soñar en más de uno.”<br />

En las páginas siguientes leerán las historias de hombres<br />

y mujeres que han escrito, y muchos lo siguen haciendo,<br />

en la preciosa lengua española del país en que<br />

nacieron, cuyas obras han saltado la barrera del idioma<br />

al ser traducidas al inglés, haciéndo<strong>los</strong> famosos en este<br />

país y en todo el mundo. Invito a <strong>los</strong> jóvenes lectores de<br />

esta publicación a disfrutar de sus historias, a seguir<br />

aprendiendo sobre estos autores y, ojalá, a soñar en el<br />

idioma que más le guste a cada<br />

uno.<br />

Isabel Allende es uno de mis<br />

autores favoritos. Todos sus libros,<br />

como La casa de <strong>los</strong> espíritus, De<br />

amor y de sombra y Eva Luna,<br />

basados en la vida en Chile, su país<br />

natal, pueden encontrarse en su<br />

versión original en español y en<br />

traducciones al inglés. Otro tanto<br />

ocurre con El plan infinito, la<br />

primera novela de esta escritora<br />

cuya trama se desarrolla en <strong>los</strong><br />

Estados Unidos con personajes de<br />

este país. A mí me gustó especialmente<br />

Mi país inventado, un libro<br />

en el cual ella nos muestra el Chile de su juventud y<br />

recuerda que su abuelo fue su inspiración para llegar a<br />

ser escritora. A ustedes, jóvenes lectores, seguramente<br />

les gustará Zorro, una novela sobre el legendario personaje<br />

que tiene lugar en California, hoy el hogar de<br />

Isabel Allende.<br />

También hay autores nacidos en América Latina que<br />

ahora viven en nuestro país y escriben en inglés. Cristina<br />

García nació en La Habana, Cuba, se crió y estudió en la<br />

ciudad de Nueva York y trabajó como periodista en San<br />

Francisco, Miami y Los Ángeles. Me gustó mucho su<br />

libro, Dreaming in Cuban. Al comentarlo, Michiko<br />

Katukani escribió en el diario <strong>The</strong> New York Times, refiriéndose<br />

a la autora: “Tiene oído de poeta para el<br />

lenguaje, siente la fascinación del historiador por el<br />

pasado y posee la intuición del músico para el flujo y<br />

reflujo de <strong>los</strong> sentimientos emotivos.” En esta novela se<br />

cuenta la historia de cuatro mujeres, tanto del pasado<br />

como del presente, cada una con su propia fi<strong>los</strong>ofía de<br />

la vida y su propia personalidad pero unidas entre sí por<br />

el amor que se profesan. El libro, de una calidad lírica<br />

que recuerda el lenguaje de <strong>los</strong> sueños, nos fascina al<br />

presentar las diferentes voces de las cuatro protagonistas,<br />

lo cual nos permite apreciar la historia comunitaria<br />

y la formación de víncu<strong>los</strong> comunales que se<br />

adquieren primero en la familia inmediata, y más tarde<br />

en el grupo cultural más amplio.<br />

A Sandra Cisneros, escritora mexicano-americana dedicada<br />

a obras de ficción, le encantan las controversias<br />

culturales, ¡y a mí me encanta ella por eso mismo! En<br />

uno de sus libros más conocidos, que la hizo acreedora<br />

al premio National Book Award, titulado <strong>The</strong> House on<br />

Mango Street (1984), escribe: “Un día seré dueña de mi<br />

propia casa, pero no olvidaré quién soy ni de dónde<br />

vengo.” En 1997 demostró la verdad de esta afirmación<br />

al pintar de color morado brillante su casa en el distrito<br />

histórico de San Antonio,<br />

en Texas, contraviniendo<br />

las leyes de la ciudad<br />

sobre preservación histórica,<br />

porque dijo que ese<br />

color era parte fundamental<br />

de su herencia mexicana.<br />

Sandra figura en la<br />

exposición “Nuestros<br />

caminos, nuestras historias”<br />

en la Smithsonian<br />

Institution, patrocinada<br />

por Ford Motor Company.<br />

En esta exposición se<br />

destacan asimismo otros<br />

escritores latinos, como,<br />

por ejemplo, el periodista<br />

John Quiñones.<br />

La novelista dominicana-americana Julia Álvarez, en<br />

Something to Declare, que es una colección de ensayos<br />

personales, dice que “a través de la escritura me<br />

entrego a una familia mucho más grande que la mía”,<br />

recordando la observación del escritor de ficción Robert<br />

Stone en el sentido de que “a través de la escritura<br />

cuidamos de la familia humana”. Me gustan mucho las<br />

novelas de Álvarez, especialmente Yo, porque son<br />

emblemáticas de la actual generación de escritores <strong>hispanos</strong><br />

que se interesan profundamente en la familia.<br />

Nacida en la ciudad de Nueva York de padres dominicanos,<br />

Álvarez describe escenas y sensibilidades<br />

derivadas de su propia historia. La novela Yo es una<br />

divertida historia en la que figura nuevamente la familia<br />

García, que apareció en su primer libro, How the<br />

García Girls Lost <strong>The</strong>ir Accents, y en la cual la autora<br />

habla sobre una existencia doble y las experiencias conflictivas<br />

resultantes. Esta escritora, que habita dos culturas,<br />

ha logrado trascender las barreras culturales<br />

mediante su dominio del arte de escribir.<br />

A medida que ustedes adquieran el gusto por la lectura,<br />

no dejen de leer a Gabriel García Márquez. Es el único<br />

sobreviviente entre <strong>los</strong> latinoamericanos que han ganado<br />

el Premio Nóbel de Literatura. Su famosa novela<br />

Cien años de soledad, que cuenta la historia de la familia<br />

Buendía en el mítico pueblo de Macondo, sentó <strong>los</strong><br />

patrones del realismo mágico, estilo literario adoptado<br />

por muchos autores latinoamericanos y de otras<br />

regiones del mundo.<br />

No es nueva la fama y el reconocimiento que han logrado<br />

autores <strong>hispanos</strong> más allá de las fronteras de las tierras<br />

en que nacieron. América Latina ha sido pródiga en<br />

la producción de poetas. Hasta hoy subsiste el recuerdo<br />

de cinco poetas nacidos en el siglo 19 que fueron <strong>los</strong><br />

precursores del modernismo, el movimiento literario<br />

que abrió el camino a formas menos elaboradas de la<br />

poesía. El<strong>los</strong> son José Martí (Cuba), José Asunción Silva<br />

(Colombia), Rubén Darío (Nicaragua), Amado Nervo<br />

(México) y Leopoldo Lugones (Argentina). A mí me<br />

encantan también las poesías de la chilena Gabriela<br />

Mistral y su compatriota Pablo Neruda, quienes junto<br />

con el guatemalteco Miguel Ángel Asturias fueron<br />

ganadores del Premio Nóbel.<br />

En <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos tenemos un rico patrimonio cultural<br />

hispano, del cual la literatura en español, tanto la<br />

antigua como la moderna, forma una parte muy importante.<br />

Contamos con una impresionante diversidad de<br />

voces, y sin embargo existe un vínculo de reconocimiento<br />

entre ellas, podríamos decir que una camaradería de<br />

familia. La literatura hace que dos mundos y dos culturas<br />

se junten en busca de comprensión mutua.<br />

Aunque podamos hablar con acentos diferentes y usar<br />

expresiones distintas, todos nosotros compartimos la<br />

experiencia de vivir en dos culturas, así como la habilidad<br />

de comunicarnos, y, lo que es aún más importante,<br />

de pensar y sentir en más de un idioma. Los poetas y <strong>los</strong><br />

escritores no aceptan confines impuestos por el idioma,<br />

la geografía o la política. Tenemos mucho que aprender<br />

de el<strong>los</strong>.<br />

José Martí lo expresó muy bien en uno de sus Versos<br />

sencil<strong>los</strong>:<br />

Yo vengo de todas partes,<br />

y hacia todas partes voy:<br />

arte soy entre las artes,<br />

en <strong>los</strong> montes, monte soy..<br />

El Mes de la Hispanidad<br />

Esta conmemoración nacional, que comenzó en 1968 con una semana de duración, recuerda muchos acontecimientos<br />

importantes que ocurrieron en <strong>los</strong> meses de septiembre y octubre. El Mes de la Hispanidad comienza<br />

el 15 de septiembre, fecha en que varias naciones latinoamericanas obtuvieron su independencia. Concluye el<br />

15 de octubre, después del Día de la Raza, celebrado el 12 de octubre, que es una conmemoración del patrimonio<br />

cultural de muchos latinoamericanos.

4<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

Like writers, <strong>Hispanic</strong> Americans are a diverse group<br />

By Kathy Dahlstrom<br />

Isabel Allende grew up in Chile in the 1950s. Gary Soto's<br />

childhood home was next to a junkyard in Fresno,<br />

California. Colombian-born Laura Restrepo rarely went<br />

to school because her family traveled so much.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> authors come from many different backgrounds.<br />

And what they write about is just as varied.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir work ranges from personal experiences to<br />

news reports, from thoughtful poetry and whimsical<br />

fiction to the dark crime and mystery writing known<br />

as "Latin Noir."<br />

Sure, they are linked by language and the part of the<br />

world they or their ancestors came from. But with 22<br />

different countries of origin, the growing <strong>Hispanic</strong> or<br />

Latino population is one of the most diverse groups in<br />

the United States.<br />

While many are new to this country—and may not<br />

even be citizens—others trace their roots way back.<br />

Some are Americans because their land was taken over<br />

by the U.S. government.<br />

Under the Treaty of Hidalgo in 1848, which ended the<br />

Mexican War, Mexico handed over California, Utah,<br />

Nevada and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico<br />

and Arizona to the United States.<br />

Other <strong>Hispanic</strong>s came here for political freedom,<br />

better education opportunities, or better work.<br />

Some writers create their work in Spanish and it is<br />

then translated into English. Others tell stories in<br />

English or weave both languages together into colorful<br />

Spanglish.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Americans aren't even all the same race.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are White, Black, Native American, Asian and<br />

multi-racial.<br />

U.S. Census Bureau reports on the <strong>Hispanic</strong> population<br />

show a fast-growing but very diverse group.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Census predicts that Latinos/<strong>Hispanic</strong>s will be one<br />

quarter of the U.S. population by 2050, representing<br />

67 million people.<br />

In 2002 the Census Bureau reported <strong>Hispanic</strong>s had<br />

become the nation's largest minority group at 13.3<br />

percent of the population, and by June 2005 the<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> population had grown to 41.3 million. <strong>The</strong><br />

rate of population growth for <strong>Hispanic</strong>s was almost<br />

three times that for the total population in 2003-2004<br />

and accounted for about one-half of U.S. population<br />

growth since the year 2000.<br />

But within that group there is tremendous variety.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong>s are not a monolithic group. Among the<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> population, two-thirds (66.9 percent) were<br />

Mexican, 14.3 percent Central and South American, 8.6<br />

percent Puerto Rican, 3.7 percent Cuban and the<br />

remaining 6.5 percent were of other origins.<br />

U.S. <strong>Hispanic</strong>s tended to live in the West (44.2 percent)<br />

and South (34.8 percent) but many chose the<br />

Northeast (13.3 percent) and Midwest (7.7 percent).<br />

Nearly half of all <strong>Hispanic</strong>s lived in big cities, 34.4<br />

percent were under age 18 and two in five were<br />

foreign born.<br />

Al igual que <strong>los</strong> escritores, <strong>los</strong> hispanoamericanos<br />

conforman un grupo diverso<br />

Author & Journalist Jorge Ramos<br />

Por Kathy Dahlstrom<br />

Isabel Allende creció en Chile en la década de 1950.<br />

Gary Soto pasó su infancia en una casa situada junto a<br />

un depósito de chatarra en Fresno, California. Laura<br />

Restrepo, nacida en Colombia, rara vez asistió a la<br />

escuela cuando niña porque su familia viajaba muy<br />

frecuentemente.<br />

Hay autores <strong>hispanos</strong> cuyos antecedentes personales<br />

son tan diversos como <strong>los</strong> temas de sus obras, que van<br />

desde la narración de experiencias personales hasta<br />

el reportaje de noticias, desde la poesía y la ficción<br />

imaginativa hasta las oscuras historias de crimen y misterio<br />

conocidas como “el noir latino”.<br />

Ciertamente, a estos autores <strong>los</strong> une el idioma y la<br />

región del mundo en la cual el<strong>los</strong> o sus antepasados<br />

nacieron, pero hay que tener presente que la creciente<br />

población hispana o latina de <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos procede<br />

de 22 países diferentes y constituye por tanto<br />

uno de <strong>los</strong> grupos más diversos en este país.<br />

Si bien muchos <strong>hispanos</strong> han llegado recientemente a<br />

este país y muchos de el<strong>los</strong> quizás no han adquirido<br />

aún la ciudadanía, en cambio otros tienen antiguas<br />

raíces aquí. De acuerdo con el tratado de Hidalgo de<br />

1848, que puso fin a la guerra con México, este país<br />

entregó a <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos <strong>los</strong> estados de California,<br />

Utah, Nevada y partes de Colorado, Wyoming, Nuevo<br />

México y Arizona.<br />

La diversidad entre escritores <strong>hispanos</strong> también es<br />

manifiesta. Algunos escriben en español y sus obras<br />

luego son traducidas al inglés. Otros cuentan historias<br />

en inglés o combinan este idioma y el español en lo<br />

que se denomina “Spanglish”.<br />

No hay uniformidad ni siquiera en cuanto a la raza,<br />

porque <strong>los</strong> latinos en este país son blancos, afro latinos,<br />

americanos nativos y asiáticos, o pertenecen a<br />

más de un grupo racial.<br />

Informes de la Oficina del Censo de <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos<br />

muestran que la población hispana es un grupo de rápido<br />

crecimiento y sumamente diverso. La Oficina del<br />

Censo estima que en el año 2050 la población latina llegará<br />

a ser una cuarta parte de la población total del<br />

país, con 67 millones de personas. En 2002 esta oficina<br />

informó que <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong> habían llegado a ser la<br />

minoría más numerosa de la nación con el 13.3 por<br />

ciento de la población total. En junio de 2005 el total<br />

de <strong>hispanos</strong> ascendió a 41.3 millones. La tasa de crecimiento<br />

de la población hispana fue casi tres veces más<br />

alta que la de la población total en el período 2003-<br />

2004, y representó aproximadamente la mitad del crecimiento<br />

de la población del país desde el año 2000.<br />

Los <strong>hispanos</strong> no son un grupo monolítico sino que<br />

ofrecen una enorme variedad. Dos tercios de <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong><br />

(66.9 por ciento) son mexicanos, 14.3 por ciento<br />

proceden de América Central y América del Sur, 8.6<br />

por ciento son puertorriqueños, 3.7 por ciento son<br />

cubanos y el 6.5 por ciento restante tiene otros orígenes.<br />

Aunque <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong> tienden a vivir en el oeste<br />

de <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos (44.2 por ciento) y en el sur del<br />

país (34.8 por ciento), muchos eligieron el nordeste<br />

(13.3 por ciento) y la región central del oeste (7.7 por<br />

ciento). Casi la mitad de todos <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong> vive en las<br />

ciudades principales. El 34.4 por ciento eran menores<br />

de 18 años en la fecha de estos informes del censo, y<br />

dos de cada cinco habían nacido en el extranjero.

Los Hispanos en la literatura y en el cuento 5<br />

World of book publishing responds to <strong>Hispanic</strong> influence<br />

Seven publishers bid on Alisa<br />

Valdes-Rodriguez' first young<br />

adult novel—<strong>The</strong> Haters,<br />

which will come out next<br />

year. <strong>The</strong> popular "Latina<br />

chick lit" author reportedly<br />

sold the book about<br />

California high schoolers to<br />

Little Brown & Company for<br />

six figures.<br />

As America's face changes,<br />

so does its taste. Books by<br />

and about <strong>Hispanic</strong>s are selling<br />

like never before.<br />

According to the Association<br />

of American Publishers<br />

(AAP), U.S. <strong>Hispanic</strong>s have<br />

more than $700 billion in<br />

spending power. Latinos<br />

younger than 35 spend more<br />

than $300 billion a year.<br />

‘Reading opens<br />

up everything.<br />

Books<br />

for me led to<br />

my American<br />

dream.’<br />

Rene Alegria<br />

seeking out authors who represent the nation's growing<br />

diversity. AAP even named May "Latino Books<br />

Month." "Get Caught Reading/¡Ajá, leyendo!" posters<br />

feature Gloria Estefan, Maya and Miguel, Jorge Ramos,<br />

Dora the Explorer and others. Rene Alegria, publisher of<br />

Rayo/HarperCollins, calls the month-long celebration an<br />

"opportunity to highlight the breadth of talent within<br />

the Latino literary community." He hopes it will encourage<br />

reading throughout the <strong>Hispanic</strong> community and<br />

help non-Latinos find books they will enjoy.<br />

That's what Rayo—which means flash of lightning in<br />

Spanish—is doing. In 2000 when it started publishing<br />

books for and about <strong>Hispanic</strong>s, the Harper Collins group<br />

printed 12 titles in English and Spanish.<br />

Its goal is to have 75 books published a year by authors<br />

such as Isabel Allende, who grew up in Chile; Victor<br />

Villaseñor of Southern California; Mexico-born TV<br />

anchor Jorge Ramos of Miami and Chicano writer Luis<br />

Rodriguez of Los Angeles. This fall it will publish its first<br />

children's book, written by singer Gloria Estefan.<br />

"We walked to the library on Saturday. It was such an<br />

adventure," the Phoenix, Arizona, native recalled.<br />

"Reading opens up everything. Books for me led to my<br />

American dream."<br />

Another large publisher, Random House, plans to double<br />

the books in its Vintage Español line within five<br />

years. Its dozen Spanish titles include Sandra Cisneros'<br />

best-seller Caramelo and a Spanish translation of former<br />

President Bill Clinton's best-selling autobiography My<br />

Life (Mi vida).<br />

Simon and Schuster paired up with Spanish publisher<br />

Grupo Santillana to form Libros en Español. Penguin<br />

Ediciones publishes paperbacks by 20th century authors<br />

in Spanish.<br />

One Texas publisher has been promoting Latino authors<br />

for more than three decades. Arte Público Press at the<br />

University of Houston is well known for introducing<br />

new writers and searching out <strong>los</strong>t works.<br />

Major publishing houses are<br />

Alegria, whose Mexican-American family spoke Spanish<br />

at home, fell in love with books as a child.<br />

El mundo editorial responde a la influencia hispana<br />

Siete empresas editoriales presentaron ofertas para<br />

publicar <strong>The</strong> Haters, la primera novela para jóvenes<br />

adultos de Alisa Valdés-Rodríguez, que saldrá a la luz<br />

el año próximo. Se dice que esta popular autora del<br />

género conocido como “Latina chick lit” vendió su<br />

libro sobre estudiantes de la escuela secundaria en<br />

California a la editorial Little Brown & Company por<br />

un precio que alcanza seis cifras.<br />

A medida que va cambiando el rostro de <strong>los</strong> Estados<br />

Unidos, también cambia la afición por la lectura. Libros<br />

escritos por <strong>hispanos</strong> y sobre <strong>hispanos</strong> se están vendiendo<br />

más que nunca. Según la Association of<br />

American Publishers (AAP), entidad que agrupa a las<br />

editoriales de este país, <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong> en <strong>los</strong> Estados<br />

Unidos tienen un poder adquisitivo de más de 700 mil<br />

millones de dólares. Latinos menores de 35 años de<br />

edad gastan más de 300 mil millones de dólares al<br />

año.<br />

Las principales casas editoriales están en busca de<br />

autores que reflejen la creciente diversidad nacional.<br />

La AAP ha declarado a mayo “El mes del libro latino”.<br />

Afiches que leen “Get Caught Reading / ¡Ajá, leyendo!”<br />

muestran, entre otros, a Gloria Estefan, Maya y<br />

Miguel, Jorge Ramos y Dora la Exploradora.<br />

René Alegría, jefe editorial de Rayo/HarperCollins, dice<br />

que la celebración de un mes dedicado al libro latino<br />

brinda “una oportunidad para enfatizar el amplio talento<br />

de la comunidad literaria latina”. Además expresa<br />

la esperanza que servirá de estímulo a la lectura en<br />

la comunidad hispana y que ayudará a personas que<br />

no son de origen latino a encontrar libros de su agrado.<br />

Eso es precisamente lo que la editorial Rayo está<br />

haciendo. En el año 2000, cuando comenzó a publicar<br />

libros escritos por <strong>hispanos</strong> y sobre <strong>hispanos</strong>, este<br />

“La lectura abre todas las puertas.<br />

Los libros me guiaron para alcanzar<br />

mi sueño americano.”<br />

Rene Alegria<br />

grupo de la empresa Harper Collins lanzó 12 libros en<br />

inglés y español. Su meta es publicar un total de 75<br />

libros cada año por autores como Isabel Allende, quien<br />

creció en Chile; Víctor Villaseñor, residente en el sur de<br />

California; el presentador de televisión Jorge Ramos,<br />

nacido en México y actualmente residente en Miami; y<br />

el escritor chicano Luis Rodríguez, de <strong>los</strong> Ángeles. Este<br />

otoño Rayo publicará su primer libro para niños,<br />

escrito por la cantante Gloria Estefan.<br />

Alegría, cuya familia mexicano-americana hablaba<br />

español en el hogar, se enamoró de <strong>los</strong> libros cuando<br />

era niño. “Todos <strong>los</strong> sábados caminábamos hasta la<br />

biblioteca. Era una gran aventura”, recordó el editor,<br />

quien nació en Phoenix, Arizona. “La lectura abre<br />

todas las puertas. Los libros me guiaron para alcanzar<br />

mi sueño americano.”<br />

Otra gran editorial, Random House, tiene planes para<br />

doblar el número de libros que publica en su serie<br />

Vintage Español en <strong>los</strong> próximos cinco años. Entre la<br />

docena de libros en español que publica actualmente<br />

se encuentran el éxito de ventas de Sandra Cisneros<br />

titulado Caramelo, y una traducción al español de la<br />

autobiografía del ex presidente Bill Clinton, también<br />

de gran venta, titulada Mi vida.<br />

Por su parte, la editorial Simon and Schuster se ha<br />

unido con la editorial española Grupo Santillana y ha<br />

creado la entidad Libros en Español. Penguin Ediciones<br />

publica libros en rústica escritos en español por<br />

autores del siglo 20.<br />

Una casa editorial de Texas lleva más de tres décadas<br />

promoviendo a autores latinos. Arte Público Press, en<br />

la Universidad de Houston, es muy conocida por su<br />

labor de presentación de autores nuevos y por su<br />

búsqueda de obras perdidas.

6<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

Writers who have made their mark<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> writers are attracting readers around the world with stories of culture, heritage and experience.<br />

Here are some "hot" authors who are making a mark with their work in the United States and elsewhere.<br />

Escritores que dejan huella<br />

Escritores <strong>hispanos</strong> atraen hoy a lectores de todo el mundo con historias sobre su cultura, patrimonio nacional<br />

y experiencia. Los autores nombrados a continuación están de moda y sus obras han dejado huella en <strong>los</strong> Estados<br />

Unidos y otros países.<br />

Isabel Allende (1942-)<br />

Isabel Allende's<br />

Chilean grandfather<br />

spoke in proverbs,<br />

knew hundreds of<br />

folk tales and recited<br />

long poems from<br />

memory.<br />

"This formidable<br />

man gave me the<br />

gift of discipline<br />

and love for language;<br />

without<br />

them I could not<br />

devote myself to<br />

writing today," she<br />

wrote in her memoir<br />

My Invented<br />

Country.<br />

Actually, a letter to her nearly 100-year-old grandfather<br />

spurred Allende to write a powerful novel<br />

based on her family's history. Forced to leave her<br />

homeland after a military coup, the journalist had<br />

not written for years.<br />

That book, <strong>The</strong> House of the Spirits, led to other novels<br />

— including City of the Beast for young readers,<br />

Of Love and Shadows, Daughter of Fortune and a<br />

short story collection <strong>The</strong> Stories of Eva Luna. Now living<br />

in California, Allende has retold the story of Zorro<br />

in her latest book.<br />

Isabel Allende (1942-)<br />

El abuelo chileno de Isabel Allende hablaba en<br />

proverbios, sabía cientos de cuentos populares y<br />

recitaba de memoria largos poemas. “Este hombre<br />

formidable me dio el don de la disciplina y el amor<br />

por el lenguaje, sin <strong>los</strong> cuales hoy no podría dedicarme<br />

a la escritura”, escribió la autora de Mi país<br />

inventado.<br />

Isabel Allende<br />

La casa de <strong>los</strong> espíritus fue la primera de varias novelas,<br />

entre ellas La ciudad de las bestias, escrita para<br />

lectores jóvenes, De amor y de sombra, Hija de la fortuna<br />

y una colección de cuentos cortos,<br />

Cuentos de Eva Luna. El libro más<br />

reciente de Isabel Allende, quien hoy<br />

vive en California, se titula Zorro y es<br />

una nueva versión de la historia del legendario<br />

personaje.<br />

Oscar Hijue<strong>los</strong> (1951-)<br />

Oscar Hijue<strong>los</strong> was born in New York<br />

City, not Cuba. But it's hard to tell that<br />

from reading his books.<br />

<strong>The</strong> novels blend stories from his parents'<br />

homeland with his own experiences<br />

as a child of immigrants. He does<br />

it so well that his <strong>The</strong> Mambo Kings<br />

Play Songs of Love won a prestigious<br />

Pulitzer Prize for fiction.<br />

Hijue<strong>los</strong>, who has a master's degree in English and<br />

writing from <strong>The</strong> City College of New York, started<br />

out in advertising. He wrote short stories in his free<br />

time before writing his first novel, Our House in the<br />

Last World.<br />

Oscar Hijue<strong>los</strong> (1951-)<br />

Oscar Hijue<strong>los</strong> nació en la ciudad de Nueva York y<br />

no en Cuba, pero es difícil creerlo cuando se leen sus<br />

libros. Sus novelas se basan en historias de la patria<br />

de sus padres entremezcladas con su propia experiencia<br />

como hijo de inmigrantes. Tan bien logra su<br />

propósito que <strong>The</strong> Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love<br />

le hizo acreedor al prestigioso Premio Pulitzer para<br />

una obra de ficción.<br />

Hijue<strong>los</strong>, quien obtuvo una maestría en inglés y escritura<br />

en City College of New York, al comienzo trabajó<br />

en publicidad. En sus ratos libres escribía cuentos cortos<br />

hasta que completó su primera novela, Our House<br />

in the Last World.<br />

En el año 2000 ganó un Premio Patrimonio Cultural<br />

Hispano por usar su escritura “para explorar la<br />

compleja experiencia de inmigrantes <strong>hispanos</strong> en<br />

<strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos, documentando sus esfuerzos y<br />

sus sueños.”<br />

Laura Restrepo (1950-)<br />

Laura Restrepo<br />

Most of Laura Restrepo's novels are based on her<br />

reporting. She investigated many of the problems<br />

that show up in her books.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Colombian writer didn't attend school until she<br />

started college at 15. Her early education came from<br />

traveling with her family and reading books by great<br />

authors.<br />

At just 16 she taught literature in a school for boys<br />

from poor families. After college she protested<br />

against poverty and injustice in Colombia, Spain and<br />

Argentina, where she was in the underground resistance<br />

against the military dictatorship.<br />

La carta que Allende escribió a su abuelo cuando éste<br />

tenía casi 100 años de edad le sirvió de inspiración<br />

para escribir una emotiva novela basada en la historia<br />

de su familia. Obligada a salir de su patria después de<br />

un golpe militar, dejando atrás su profesión de periodista,<br />

Allende no había vuelto a escribir en varios<br />

años.<br />

Oscar Hijue<strong>los</strong><br />

In 2000 he won a <strong>Hispanic</strong> Heritage Award for using<br />

his writing "to explore the complex experience of<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> immigrants in America, thereby documenting<br />

their struggles and dreams."<br />

Returning to her homeland, she became a journalist<br />

writing about politics. After serving on a peace commission<br />

negotiating with rebel forces, she became<br />

critical of the government and her life was threatened.<br />

She was forced into exile in Mexico, where she<br />

wrote her first novel, La Isla de la Pasión.<br />

In 1989 she returned home to Colombia to continue<br />

her writing. She now lives in Bogota.

Los Hispanos en la literatura y en el cuento 7<br />

Laura Restrepo (1950-)<br />

Casi todas las novelas de Laura Restrepo nacen de sus<br />

reportajes porque ella había investigado como periodista<br />

muchos de <strong>los</strong> problemas que figuran en sus<br />

libros.<br />

Esta escritora colombiana no asistió a la escuela hasta<br />

que cumplió 15 años. Los viajes con su familia y la lectura<br />

de <strong>los</strong> mejores autores fueron la base de su<br />

temprana educación. A <strong>los</strong> 16 años de edad enseñó literatura<br />

en una escuela para varones de familias pobres.<br />

Después de completar sus estudios universitarios participó<br />

en manifestaciones de protesta contra la<br />

pobreza y la injusticia en Colombia, España y la<br />

Argentina. En este último país luchó en el movimiento<br />

de resistencia clandestina contra la dictadura militar.<br />

Al regresar a su patria emprendió la carrera periodística<br />

escribiendo sobre temas políticos. Fue miembro de<br />

una comisión de paz que negoció con fuerzas rebeldes<br />

y posteriormente criticó al gobierno. Recibió amenazas<br />

de muerte y se vio obligada a exiliarse en México,<br />

donde escribió su primera novela, La isla de la pasión.<br />

En 1989 regresó a Colombia para continuar escribiendo.<br />

Esmeralda Santiago (1948-)<br />

With each new book, Esmeralda Santiago reveals more<br />

about her life. <strong>The</strong> memoirs<br />

Almost a Woman, When I Was<br />

Puerto Rican and <strong>The</strong> Turkish<br />

Lover each add to her story.<br />

Until she was 13, Santiago lived<br />

a peasant life in Puerto Rico.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n her single mother moved<br />

the large family to Brooklyn,<br />

N.Y. <strong>The</strong> adjustment was not<br />

easy for the teen and her siblings.<br />

In When I Was Puerto Rican,<br />

Santiago recalled being told<br />

she was no longer Puerto Rican<br />

"because my Spanish was rusty,<br />

my gaze too direct, my personality<br />

too assertive. ... Yet in the<br />

United States, my darkness, my accented speech, my<br />

frequent lapses into confused silence between English<br />

and Spanish identified me as foreign, non-American.<br />

"In writing the book I wanted to get back to that feeling<br />

of 'Puertorican-ness' I had before I came here."<br />

Esmeralda Santiago (1948-<br />

Esmeralda Santiago revela un poco más de su vida con<br />

cada nuevo libro. Cada una de sus memorias,Casi una<br />

mujer, Cuando era puertorriqueña y El amante turco,<br />

agrega algo a la historia de su vida.<br />

Santiago vivió la vida de campesinos en Puerto Rico<br />

hasta que cumplió 13 años. Cuando tenía esa edad,<br />

su madre soltera se mudó con su numerosa familia a<br />

Brooklyn, en la ciudad de Nueva York. Para Esmeralda y<br />

sus hermanos no fue fácil hacer <strong>los</strong> ajustes necesarios.<br />

En Cuando era puertorriqueña la autora recuerda que<br />

se le decía que ella ya no era puertorriqueña “porque<br />

mi español no era muy bueno, mi mirada era demasiado<br />

directa, mi personalidad demasiado fuerte. Pero en<br />

<strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos, mi tez oscura, mi acento al hablar,<br />

mis frecuentes lapsos de silencio al confundirme entre<br />

el inglés y el español, me identificaban como extranjera,<br />

como no americana”.<br />

“Escribí el libro porque quería recuperar la sensación<br />

de ser puertorriqueña que tenía antes de venir aquí.”<br />

Además de escribir, esta talentosa actriz estudió artes<br />

dramáticas y danza en la escuela secundaria<br />

Performing Arts High School, de la ciudad de Nueva<br />

York. Tras completar estudios superiores en universidades<br />

comunitarias, ganó una beca a la Universidad de<br />

Harvard, de la que se graduó con honores.<br />

Antes de dedicarse a la escritura Santiago fundó junto<br />

con su esposo una compañía productora de películas.<br />

Uno de <strong>los</strong> proyectos recientes de la compañía es un<br />

documental sobre la vida de la autora.<br />

Victor Villaseñor (1940-)<br />

Schools around the country have their students read<br />

Victor Villaseñor's stories about his immigrant family.<br />

But the California author, who lives on the farm<br />

where he grew up, wasn't much of a student himself.<br />

Language and reading problems (later diagnosed as<br />

dyslexia) caused him to drop out of high school and<br />

move to Mexico. He was inspired by the art, music<br />

and literature he found in his parents' homeland.<br />

After many rejections, he sold his first novel Macho!<br />

His bestseller Rain of Gold, about his family, is now<br />

required reading in many U.S. school systems. He titled<br />

his account of childhood struggles with public schools<br />

Burro Genius: A Memoir.<br />

Victor Villaseñor (1940-)<br />

Muchas escuelas en todo el país hacen que sus estudiantes<br />

lean las historias de Víctor Villaseñor sobre su<br />

familia de inmigrantes. Pero este autor, que vive en el<br />

rancho en California donde creció, no era muy buen<br />

estudiante que se diga.<br />

Dificultades con el lenguaje y la lectura, que más tarde<br />

fueron diagnosticadas como dislexia, le obligaron a<br />

abandonar <strong>los</strong> estudios secundarios y mudarse a<br />

México. El arte, la música y la literatura de la patria de<br />

sus padres fueron su fuente de inspiración.<br />

Después que le fueron rechazados varios manuscritos,<br />

logró vender su primera novela, ¡Macho!. Su novela de<br />

gran venta, Lluvia de oro, que trata de su familia, es<br />

texto de lectura obligatoria en muchos sistemas escolares<br />

de <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos. Al relato de sus luchas<br />

infantiles con las escuelas públicas le puso por título<br />

Burro Genius: A Memoir.<br />

Victor Villaseñor<br />

In addition to writing, the talented actress studied<br />

drama and dance at New York City's Performing Arts<br />

High School. After attending community colleges, she<br />

won a scholarship to Harvard University where she<br />

graduated with honors.<br />

Before Santiago became a writer, she and her husband<br />

founded a film and media production company.<br />

One of its recent projects is a documentary of her life.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong>s in the News<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> writers like Laura Restrepo, Esmeralda Santiago and Victor Villaseñor draw on life experiences to create<br />

new works of art. What experiences, events or people in your community would tell about your life? In teams or<br />

alone, go through the newspaper and list experiences, events, people or places that help define life where you<br />

live. For each one, write a sentence explaining how it influences your life or that of your family.

8<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

Storytelling that is rich and varied<br />

‘With all<br />

these great<br />

storytellers<br />

around me,<br />

it's not a<br />

surprise<br />

that I like<br />

to tell<br />

stories,’<br />

Yuyi Morales<br />

Growing up in Mexico, Yuyi<br />

Morales heard many stories<br />

about death or the devil<br />

coming to the door to fetch<br />

someone. <strong>The</strong> targeted person<br />

would have to outsmart the<br />

intruder.<br />

In Morales' picture book Just a<br />

Minute: A Trickster Tale and<br />

Counting Book, Grandma<br />

<strong>Bee</strong>tle (based on the illustrator's<br />

own grandmother) cleverly<br />

delays death. When Señor<br />

Calavera (Mr. Skull) shows up<br />

at her door, she sweeps, boils<br />

tea and makes tortillas to keep<br />

from going with him.<br />

Morales said the story is<br />

"not about death, but life and<br />

grandparents and their love of<br />

children.”<br />

"I love the traditional stories,"<br />

explained the artist, who is now illustrating a<br />

Halloween story written by Puerto Rican author Marisa<br />

Montes. "I think they will just keep coming."<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> cultures are rich with traditional tales, which<br />

combine Spanish and African folk traditions with those<br />

of American native people such as Aztecs, Mayans and<br />

Tainos, the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean.<br />

Long before there were scientists, people made up stories<br />

to explain why things happen in the world. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

myths explained how the Earth was created, where thunder<br />

comes from, why there are seasons, and the like.<br />

For thousands of years, these stories were passed along<br />

by speaking, not reading. Written words didn't exist in<br />

the earliest human tribes or groups. <strong>The</strong> only way stories<br />

could be relayed was by telling them out loud.<br />

People who were good at telling stories were valued. It<br />

became their job to remember and tell the stories to<br />

others. <strong>The</strong>se stories were handed down from generation<br />

to generation.<br />

Oral storytelling is still alive today in many cultures,<br />

including our own. Antonio Sacre visits schools around<br />

the country, telling tales from his Cuban heritage and<br />

urging students to gather their own family stories.<br />

Storyteller Joe Hayes gathered enough stories from the<br />

Southwest to write 20 books.<br />

Many authors became writers because of wonderful stories<br />

they heard growing up.<br />

Yuyi Morales<br />

Morales recalls "family stories that sounded like folktales—very<br />

fantastic and hard to believe."<br />

Alma Flor Ada's grandmother and uncle were great<br />

storytellers. At bedtime her father told her stories he<br />

invented.<br />

Some stories from her Cuban childhood show up in the<br />

children's books Where the Flame Trees Bloom and<br />

Under the Royal Palms.<br />

"With all these great storytellers around me, it's not a<br />

surprise that I like to tell stories," said the author, who<br />

teaches at the University of San Francisco.<br />

Cuentos llenos de riqueza y variedad<br />

Durante su infancia en México, Yuyi Morales escuchó<br />

muchos cuentos sobre la muerte, o sobre el diablo que<br />

tocaba a la puerta en<br />

busca de una persona,<br />

quien tenía que<br />

engañar al intruso.<br />

En el libro ilustrado de<br />

Morales, Just a<br />

Minute: A Trickster<br />

Tale and Counting<br />

Book, el personaje llamado<br />

Grandma <strong>Bee</strong>tle,<br />

basado en la abuela de<br />

la autora, demora su<br />

muerte ocupándose en<br />

una multitud de quehaceres<br />

domésticos.<br />

Morales dice que su<br />

historia “no trata de la<br />

muerte, sino de la vida<br />

y del amor de <strong>los</strong><br />

abue<strong>los</strong> por sus nietos.” La artísta, que está ilustrando<br />

una historia de Halloween de la escritora puertorriqueña<br />

Marisa Montes, agrega: “Me encantan <strong>los</strong><br />

cuentos tradicionales. Creo que seguiré trabajando en<br />

el<strong>los</strong>.”<br />

La cultura hispana es rica en cuentos tradicionales, en<br />

<strong>los</strong> que se combinan tradiciones populares españolas y<br />

africanas con las de <strong>los</strong> aztecas, mayas y taínos, que<br />

son <strong>los</strong> pueb<strong>los</strong> indígenas del Caribe.<br />

Mucho antes de que hubiera científicos, la gente<br />

inventaba cuentos para explicar por qué suceden las<br />

cosas en el mundo. Estos cuentos, llamados mitos,<br />

explicaban cómo se creó la Tierra, de dónde viene el<br />

trueno, la razón de ser de las estaciones del año y<br />

otras cosas por el estilo.<br />

Durante miles de años estas historias se trasmitían<br />

hablando y no leyéndolas. Las tribus o grupos<br />

humanos más antiguos no conocían la escritura, de<br />

manera que la única forma de trasmitir un cuento era<br />

contándolo en alta voz. Las personas que sabían contar<br />

estas historias eran altamente valoradas porque su<br />

labor consistía en aprenderse <strong>los</strong> cuentos y narrar<strong>los</strong> a<br />

<strong>los</strong> demás. Así fue como estos mitos pasaron de generación<br />

en generación.<br />

La narrativa oral subsiste hoy en muchas culturas,<br />

incluyendo la nuestra. Antonio Sacre visita escuelas de<br />

todo el país contando cuentos basados en sus orígenes<br />

cubanos y alentando a <strong>los</strong> estudiantes a que obtengan<br />

sus propias historias familiares. El cuentista Joe Hayes<br />

reunió tantos cuentos del sudoeste de <strong>los</strong> Estados<br />

Unidos que ha escrito 20 libros.<br />

Muchas personas se hicieron escritores gracias a las maravil<strong>los</strong>as<br />

historias que escucharon cuando eran niños.<br />

Morales recuerda “historias familiares que parecían<br />

cuentos populares: fantásticos y difíciles de creer.”<br />

La abuela y el tío de Alma Flor Ada eran grandes narradores<br />

de cuentos. Cada noche antes de dormir, el<br />

padre de Alma Flor le contaba cuentos que él había<br />

inventado. Algunos de <strong>los</strong> cuentos que aprendió en su<br />

niñez en Cuba aparecen en <strong>los</strong> libros para niños de<br />

esta autora, como Allá donde florecen <strong>los</strong> framboyanes<br />

y Bajo las palmas reales. La autora, que es profesora<br />

en la Universidad de San Francisco, dice: “Con<br />

tantos buenos cuentistas a mi alrededor, no es sorprendente<br />

que me guste contar cuentos.”<br />

“Con tantos buenos cuentistas<br />

a mi alrededor,<br />

no es sorprendente que<br />

me guste contar cuentos.”<br />

Yuyi Morales

Los Hispanos en la literatura y en el cuento<br />

9<br />

Special works for kids<br />

Reading picture books to her young son<br />

helped Mexican-born Yuyi Morales learn<br />

English.<br />

Now parents around America are reading<br />

her stories to their youngsters.<br />

<strong>The</strong> California author and artist won a<br />

2004 Pura Belpré Award given to<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> writers and illustrators whose<br />

work "best portrays, affirms and celebrates<br />

the Latino cultural experience in<br />

an outstanding work of literature for<br />

children and youth."<br />

<strong>The</strong> award is named for a New York City<br />

children's librarian who shared folk<br />

tales she learned while growing up in<br />

Puerto Rico.<br />

To make sure the tales lived on, storyteller<br />

Belpré wrote them down. Her<br />

books retold the adventures of Martina,<br />

the beautiful Spanish cockroach; Perez<br />

the Mouse; the rainbow-colored horse;<br />

and Tiger and the Rabbit.<br />

Award-winner Julia alvarez<br />

After retiring in 1968, she<br />

continued with the New<br />

York Public Library as a storyteller<br />

and puppeteer in the<br />

federally funded South<br />

Bronx Project. A school and<br />

library children's room were<br />

named after her. She<br />

received the Mayor's Award<br />

for Arts and Culture the day<br />

before she died in 1982.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Pura Belpré awards are<br />

given every two years by the<br />

American Library<br />

Association. Winners are:<br />

2004 — Narrative: Before We<br />

Were Free, Julia Alvarez.<br />

2004 — Illustration: Just a<br />

Minute: A Trickster Tale and<br />

Counting Book, Yuyi<br />

Morales.<br />

2002 — Narrative: Esperanza Rising, Pam Muñoz Ryan.<br />

2002 — Illustration: Chato and the Party Animals,<br />

illustrated by Susan Guevara, written by<br />

Gary Soto.<br />

2000 — Narrative: Under the Royal Palms,<br />

Alma Flor Ada.<br />

2000 — Illustration: Magic Windows, Carmen<br />

Lomas Garza.<br />

1998 — Narrative: Parrot in the Oven: Mi Vida,<br />

Victor Martinez.<br />

1998 — Illustration: Snapshots from the Wedding,<br />

illustrated by Stephanie Garcia, written by<br />

Gary Soto.<br />

1996 — Narrative: An Island Like You: Stories of the<br />

Barrio, Judith Ortiz Cofer.<br />

1996 — Illustration: Chato's Kitchen, illustrated by Susan<br />

Guevara, written by Gary Soto.<br />

Libros especiales para niños<br />

Yuyi Morales nació en México. Más tarde aprendió inglés<br />

con la ayuda de libros ilustrados que ella leía a su hijo<br />

pequeño. Hoy en día en <strong>los</strong><br />

Estados Unidos muchos padres<br />

leen <strong>los</strong> cuentos de Yuyi<br />

Morales a sus hijos.<br />

Esta autora y artista, residente<br />

en California, ganó en<br />

2004 el Premio Pura Belpré,<br />

que se otorga a escritores e<br />

ilustradores <strong>hispanos</strong> cuyas<br />

obras “presentan, afirman y<br />

celebran la experiencia cultural<br />

latina creando una obra<br />

literaria excepcional para<br />

niños y jóvenes”.<br />

Este premio lleva el nombre<br />

de una bibliotecaria de Nueva<br />

York que trabajó en una biblioteca<br />

infantil de esa ciudad y que contaba <strong>los</strong> cuentos<br />

populares que había aprendido en su niñez en Puerto<br />

Rico. Para asegurar que sus cuentos perduraran, Pura<br />

Belpré <strong>los</strong> puso por escrito. En sus libros contó nuevamente<br />

las aventuras de Martina, la linda cucarachita<br />

española; las del Ratoncito Pérez; las del caballo del color<br />

del arco iris; y las aventuras de El tigre y el conejo.<br />

Después de retirarse en 1968 continuó trabajando en la<br />

Biblioteca Pública de Nueva York como cuentista y<br />

titiritera bajo el Proyecto South Bronx, financiado con<br />

fondos federales. En su honor, una escuela y una sala<br />

de una biblioteca infantil llevan su nombre. En 1982, el<br />

día antes de morir, recibió el Premio del Alcalde a las<br />

Artes y la Cultura.<br />

La Asociación Americana de Bibliotecas (American<br />

Library Association) otorga <strong>los</strong> premios Pura Belpré<br />

cada dos años. La lista de ganadores es la siguiente.<br />

2004 — Narrativa: Antes de ser libres,<br />

por Julia Álvarez.<br />

2004 — Ilustración: Just a Minute: A<br />

Trickster Tale and Counting<br />

Book, por Yuyi Morales.<br />

2002 — Narrativa: Esperanza renace, por<br />

Pam Muñoz Ryan.<br />

2002 — Ilustración: Chato y <strong>los</strong> amigos<br />

pachangueros, ilustrado por<br />

Susan Guevara y escrito por Gary<br />

Soto.<br />

2000 — Narrativa: Bajo las palmas reales,<br />

por Alma Flor Ada.<br />

2000 — Ilustración: Ventanas mágicas, por<br />

Carmen Lomas Garza.<br />

1998 — Narrativa: Parrot in the Oven: Mi Vida,<br />

por Víctor Martínez.<br />

1998 — Ilustración: Snapshots from the Wedding,<br />

ilustrado por Stephanie García y escrito por<br />

Gary Soto.<br />

1996 — Narrativa: Una isla como tú, historias del<br />

barrio, por Judith Ortiz Cofer.<br />

1996 — Ilustración: Chato y su cena, ilustrado por<br />

Susan Guevara y escrito por Gary Soto.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong>s<br />

in the News<br />

Books for children or young adults often tell stories through the eyes<br />

of kids that age. <strong>The</strong> author has to think like a child or teen to see<br />

how this would be different from the view of adults. You can practice<br />

this approach using stories in the newspaper. Find one that<br />

catches your interest today. Read it through carefully. <strong>The</strong>n rewrite<br />

it through the eyes of a boy or girl your age. Discuss with classmates<br />

how your story is different from the original.

10<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

Telling stories through journalism<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> and Latina are geared toward new immigrants<br />

as well as <strong>Hispanic</strong> Americans who were born here but<br />

want to know more about their heritage and culture.<br />

Mirta Ojita spoke only Spanish when she left Cuba at<br />

16 as part of the Mariel boatlift. But that didn't keep<br />

her from earning a scholarship to Florida Atlantic<br />

University, where she edited the student newspaper.<br />

She went on to work for the Miami Herald and New<br />

York Times, winning a Pulitzer Prize for her reporting<br />

on race in America.<br />

Ojita, whose latest work is a personal book on the<br />

1980 boatlift that helped 125,000 refugees leave Cuba<br />

for the United States, is one of many <strong>Hispanic</strong>s who<br />

have made a difference in the field of journalism.<br />

Among the best known are Maria Hinojosa of CNN,<br />

ABC's Elizabeth Vargas, Jorge Ramos of Univision and<br />

Ruben Salazar, a Los Angeles Times and television<br />

reporter who was killed during the L.A. riots in 1970.<br />

Newspapers have long been a way for people to express<br />

themselves. After the Mexican War in 1848, Spanish language<br />

newspapers sprang up in the southwestern part<br />

of the United States. <strong>The</strong>y not only told what was going<br />

on in the community and back home in Mexico, but<br />

also printed fictional stories, essays and poetry.<br />

Some larger papers even hired talented writers from<br />

Spain, Mexico and Latin America to work for them.<br />

Well-educated political refugees who came here from<br />

Central and South America often made their way into<br />

publishing. One of the most famous is José Martí, a<br />

Cuban freedom fighter whose journalism landed him in<br />

jail. While in exile in New York he wrote poetry, essays<br />

and even reported on the trial of President Garfield's<br />

assassin and a boxing prizefight.<br />

Today, <strong>Hispanic</strong> newspapers and radio and television<br />

stations are thriving, with more demand for news of<br />

interest to the growing number of <strong>Hispanic</strong>s in the<br />

United States. Researchers also have found that longtime<br />

residents don't always abandon their first language<br />

as they learn English.<br />

Newstands offer Spanish language versions of English<br />

newspapers. Magazines such as People en Español,<br />

To reflect the changing population, news operations<br />

have increased hiring of minority journalists. But the<br />

National Association of <strong>Hispanic</strong> Journalists would like<br />

to see more diverse newsrooms. Its Parity Project works<br />

with English-language news organizations to increase<br />

the percentage of Latinos in this field.<br />

According to UNITY, which represents journalists of<br />

color, newsrooms added 255 <strong>Hispanic</strong>s from 2000 to<br />

2005, but that number still represents only 4.29 percent<br />

of the workforce in newsrooms across the United States.<br />

Los relatos y el periodismo<br />

Cuando salió de Cuba a <strong>los</strong> 16 años de edad en el<br />

éxodo del Mariel, Mirta Ojita solo sabía español.<br />

Eso no le impidió ganarse una beca para asistir a la<br />

Universidad Florida Atlantic, donde fue editora del<br />

periódico estudiantil. Luego pasó a trabajar en <strong>los</strong><br />

diarios Miami Herald y New York Times y llegó a ganar<br />

un Premio Pulitzer por sus reportajes sobre la cuestión<br />

racial en <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos.<br />

Ojita, cuyo libro más reciente relata su historia personal<br />

sobre el éxodo del Mariel de 1980, cuando 125,000<br />

cubanos salieron de ese puerto en Cuba para venir a <strong>los</strong><br />

Estados Unidos como refugiados, es una entre muchos<br />

<strong>hispanos</strong> que han dejado huella en el periodismo.<br />

Entre <strong>los</strong> periodistas <strong>hispanos</strong> más conocidos se<br />

encuentran María Hinojosa, de CNN, Elizabeth Vargas,<br />

de ABC, Jorge Ramos, de Univisión, y Rubén Salazar,<br />

un reportero del diario Los Angeles Times y de la televisión,<br />

a quien mataron en <strong>los</strong> disturbios que tuvieron<br />

lugar en dicha ciudad en 1970.<br />

Los periódicos han servido por muchos años como<br />

medio de expresión para la gente. Después de la guerra<br />

entre México y Estados Unidos en 1848, periódicos<br />

en español aparecieron de repente en el sudoeste de<br />

este último país, que no solo reportaban lo que ocurría<br />

en las comunidades y en México, sino que además publicaban<br />

cuentos de ficción, ensayos y poesías. Algunos<br />

de estos periódicos, <strong>los</strong> más importantes, llegaron a<br />

contratar talentosos escritores españoles, mexicanos y<br />

latinoamericanos.<br />

Central y Sudamérica y con frecuencia se dedicaron al<br />

periodismo. Uno de <strong>los</strong> más famosos fue José Martí, un<br />

luchador por la libertad de Cuba que había sufrido el<br />

presidio por su labor como periodista. Exiliado en<br />

Nueva York, escribió poesías y ensayos, así como artícu<strong>los</strong><br />

sobre el juicio del asesino del Presidente Garfield y<br />

sobre una pelea de boxeo, entre otros reportajes.<br />

Hoy, <strong>los</strong> periódicos y las estaciones de radio y televisión<br />

en español están floreciendo, ya que va en aumento la<br />

demanda de noticias de interés para el creciente<br />

número de <strong>hispanos</strong> en <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos. Además,<br />

aún <strong>los</strong> <strong>hispanos</strong> que llevan muchos años de residencia<br />

en este país no siempre abandonan su idioma natal<br />

para aprender inglés, según varias investigaciones.<br />

En <strong>los</strong> puestos de venta se encuentran versiones en<br />

español de periódicos redactados en inglés. Revistas<br />

como People en Español, <strong>Hispanic</strong> y Latina están dirigidas<br />

a nuevos inmigrantes, pero también a hispanoamericanos<br />

que nacieron en <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos y<br />

que quieren saber más acerca de su herencia cultural.<br />

A fin de adaptarse a <strong>los</strong> cambios de población, las<br />

agencias de noticias han incrementado la contratación<br />

de periodistas pertenecientes a grupos minoritarios.<br />

No obstante, la Asociación de Periodistas Hispanos<br />

desearía que hubiera mayor diversidad en las salas de<br />

noticias. Esta asociación impulsa el Proyecto Paridad,<br />

que colabora con las organizaciones noticiosas en<br />

inglés para aumentar el porcentaje de latinos que trabajan<br />

en este campo.<br />

<strong>hispanos</strong>, afro americanos, asiáticos y americanos<br />

nativos – entre <strong>los</strong> años 2000 y 2005 el número de <strong>hispanos</strong><br />

en las salas de noticias se incrementó por 255,<br />

pero aún así esa cifra equivale solamente al 4.29 por<br />

ciento de la fuerza laboral en todas las salas de noticias<br />

en <strong>los</strong> Estados Unidos.<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong>s<br />

in the News<br />

Ruben Salazar<br />

Journalists tell the story of America. And as the U.S.<br />

population of <strong>Hispanic</strong> Americans grows, newspapers,<br />

magazines and TV stations are seeking more<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> and Latino journalists. As a class, talk about<br />

why it is important to the news media to recruit<br />

more <strong>Hispanic</strong>s. <strong>The</strong>n write a short newspaper editorial<br />

outlining how <strong>Hispanic</strong> journalists could enhance<br />

news coverage of America's communities.<br />

Photo by Los Angeles - Times<br />

En esa época, refugiados políticos de buena formación<br />

académica vinieron a este país procedentes de América<br />

Según la entidad UNITY – que representa a periodistas

Los Hispanos en la literatura y en el cuento 11<br />

A Classic Work, a Great Honor<br />

<strong>The</strong> year 2005 marks the 400th anniversary of<br />

the publication of Don Quixote de la Mancha.<br />

Many consider this story of an idealistic man<br />

who goes in search of adventure to be the first<br />

modern novel.<br />

In many countries around the world, Miguel de<br />

Cervantes' bestselling book was celebrated with<br />

plays, debates, exhibitions, concerts and films.<br />

In 2002 Don Quixote was voted the best book<br />

ever written by a group of 100 famous authors<br />

from 54 countries.<br />

Each year Premio Miguel de Cervantes (the<br />

Past Cervantes Prize winners are:<br />

La lista de ganadores es la siguiente:<br />

2004 — Rafael Sánchez Fer<strong>los</strong>io (Spain) (España)<br />

2003 — Gonzalo Rojas (Chile)<br />

2002 — José Jiménez Lozano (Spain) (España)<br />

2001 — Álvaro Mutis<br />

(Colombia)<br />

2000 — Francisco<br />

Umbral<br />

(Spain)<br />

(España)<br />

1999 — Jorge<br />

Edwards<br />

(Chile)<br />

1998 — José Hierro<br />

(Spain)<br />

(España)<br />

1997 — Guillermo<br />

Cabrera<br />

Infante<br />

(Cuba)<br />

1996 — José García Nieto (Spain) (España)<br />

1995 — Camilo José Cela (Spain) (España)<br />

1994 — Mario Vargas L<strong>los</strong>a (Peru (Perú))<br />

1993 — Miguel Delibes (Spain) (España)<br />

1992 — Dulce María Loynaz (Cuba)<br />

1991 — Francisco Ayala (Spain) (España)<br />

Miguel de Cervantes Prize) is awarded to an outstanding<br />

writer in the Spanish language. <strong>The</strong><br />

prize is named in honor of the author of Don<br />

Quixote.<br />

Like his character, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra<br />

(1547-1616) had many adventures during his life.<br />

As a Spanish soldier he was wounded and captured<br />

by the enemy. Despite his writing success,<br />

he had money troubles and spent years in jail.<br />

Established in 1975 by the Spanish Ministry of<br />

Culture, the Cervantes award winners list<br />

includes writers from many countries. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

receive a prize of 90,000 euros ($120,000).<br />

1989 — Augusto Roa Bastos (Paraguay)<br />

1988 — María Zambrano (Spain) (España)<br />

1987 — Car<strong>los</strong> Fuentes (Mexico, born in Panama)<br />

(México, nacido<br />

en Panamá)<br />

1986 — Antonio Buero<br />

Vallejo (Spain)<br />

(España)<br />

1985 — Gonzalo<br />

Torrente<br />

Ballester (Spain)<br />

(España)<br />

1984 — Ernésto Sábato<br />

(Argentina)<br />

1983 — Rafael Alberti<br />

(Spain) (España)<br />

1982 — Luis Rosales<br />

(Spain) (España)<br />

1981 — Octavio Paz (Mexico) (México)<br />

1980 — Juan Car<strong>los</strong> Onetti (Uruguay)<br />

1979 — Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina) and Gerardo<br />

Diego (Spain) (España)<br />

1978 — Dámaso Alonso (Spain) (España)<br />

1977 — Alejo Carpentier (Cuba)<br />

1976 — Jorge Guillén (Spain) (España)<br />

Una obra clÁsicA,<br />

un gran honor<br />

En este año 2005 se conmemora<br />

el 400 aniversario de la publicación<br />

de Don Quijote de la<br />

Mancha, obra maestra que<br />

cuenta la historia de un idealista<br />

que va en busca de aventuras<br />

y que muchos consideran<br />

la primera novela moderna del<br />

mundo.<br />

En muchos países del mundo<br />

se han hecho homenajes al<br />

famoso libro de Miguel de<br />

Cervantes mediante obras de<br />

teatro, debates, exposiciones,<br />

conciertos y películas. En 2002,<br />

un grupo de 100 autores<br />

famosos procedentes de 54<br />

países eligió a Don Quijote<br />

como el mejor libro que se ha<br />

escrito jamás.<br />

El Premio Miguel de Cervantes, en honor al autor de Don<br />

Quijote, se otorga anualmente a un destacado escritor en<br />

español.<br />

Al igual que su célebre personaje, Miguel de Cervantes<br />

Saavedra (1547-1616) tuvo muchas aventuras en su vida.<br />

Cuando prestaba servicios como soldado español fue herido y<br />

hecho prisionero por el enemigo. A pesar de su éxito literario,<br />

tuvo dificultades monetarias y pasó varios años en prisión.<br />

El Premio Cervantes fue establecido en 1975 por el Ministerio<br />

de Cultura de España. Escritores de muchos países han ganado<br />

este premio, que consiste en 90,000 euros (es decir, $120,000)<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong>s<br />

in the News<br />

Miguel de Cervantes' "Don Quixote" tells the story of a man<br />

who seeks adventure by doing good for others. In doing so<br />

he develops a special "code of honor" for himself to guide<br />

his behavior. In the newspaper, find a story about a person<br />

doing good for others. Write a paragraph describing a "code<br />

of honor" that might apply for this person. Discuss ideas as a<br />

class.<br />

1990 — Adolfo Bioy Casares (Argentina)

12<br />

<strong>Hispanic</strong> Literature & Storytelling<br />

<strong>The</strong> Nobel Prize Highest honors for <strong>Hispanic</strong> writers<br />

Often writers loved in their own countries are unknown in other places. Winning the Nobel Prize in Literature<br />

makes them famous around the world.<br />

Since 1901, the prize has honored authors from different languages and cultural backgrounds. It goes to less well<br />

known authors as well as those who have wide followings.<br />

Several <strong>Hispanic</strong> authors have won the Nobel Prize, which covers literary works including poetry, novels, short stories,<br />

plays, essays and speeches. <strong>The</strong> honors are given out in Stockholm by the Swedish Academy.<br />

El Premio Nobel Escritores <strong>hispanos</strong> obtienen <strong>los</strong> más altos honores<br />

Con frecuencia sucede que autores muy queridos en sus propios países son desconocidos en otros. Al ganar el Premio<br />

Nóbel de Literatura se hacen famosos en todo el mundo.<br />

A partir de 1901 este premio se ha concedido a autores que escriben en diferentes idiomas y que tienen antecedentes<br />

culturales diversos. El premio ha sido otorgado a autores menos conocidos, así como a otros que gozan de gran reputación.<br />