Vol. 2 Núm. 8 - Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales ...

Vol. 2 Núm. 8 - Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales ...

Vol. 2 Núm. 8 - Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

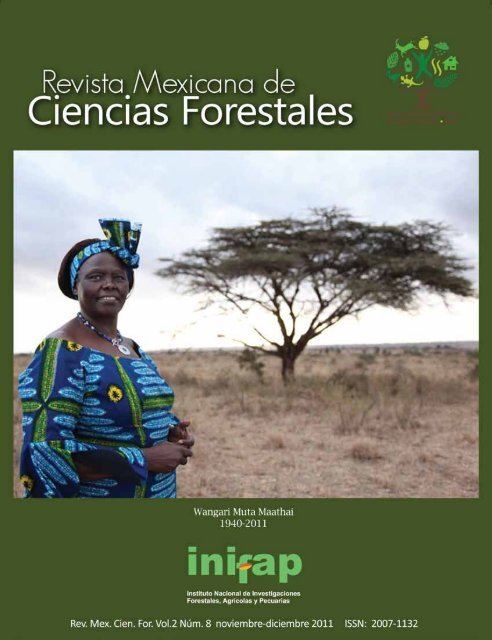

Editorial“Wangari Muta Maathai. Remembranza por su contribución al<strong>de</strong>sarrollo sostenible, la <strong>de</strong>mocracia y la paz”.«Un árbol tiene raíces en el suelo y ramas que rozan el cielo, recordándonos quepara prosperar <strong>de</strong>bemos saber nuestro origen. Al igual que los árboles, por muchoque lleguemos lejos, son nuestras raíces las que nos alimentan»Wangari Muta MaathaiWangari Muta Maathai, ganadora <strong>de</strong>l premio Nobel <strong>de</strong> la Paz 2004, falleció el domingo 25 <strong>de</strong> septiembre <strong>de</strong> 2011, justo cuando enla capital <strong>de</strong> México se clausuraba la más importante exposición forestal. Ese día lejos <strong>de</strong> guardarse un minuto <strong>de</strong> silencio, prevalecióun profundo silencio sobre tan lamentable <strong>de</strong>ceso. Hecho que en general fue compartido en el mundo -si quien hubieramuerto hubiese sido un futbolista millonario o una popular cantante aficionada a las drogas, los medios se hubieran volcadoen la noticia-. Sin embargo, su influencia se ha sentido en todo el orbe, la Revista Time la <strong>de</strong>claró Héroe <strong>de</strong>l Planeta, al sumar convalentía a su causa a miles <strong>de</strong> africanos y millones <strong>de</strong> volunta<strong>de</strong>s. Impulsó la participación colectiva, prepon<strong>de</strong>rantemente femenina,en torno a los proyectos <strong>de</strong> reforestación como un instrumento para mejorar la calidad <strong>de</strong> vida <strong>de</strong> las comunida<strong>de</strong>s rurales. Dedicósu vida a <strong>de</strong>fen<strong>de</strong>r el bosque, a otras mujeres y a la <strong>de</strong>mocracia. Pero sobre todo, ayudó a construir el concepto sostenible,formulado por otra mujer: Norman Brundtland. De hecho su activismo político estuvo ligado a su labor <strong>de</strong> conservación. En diversosforos preparatorios a la reunión <strong>de</strong> Johannesburgo, que marcaba los diez años <strong>de</strong> su similar <strong>de</strong> Río <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, seexpresaba la inquietud <strong>de</strong> no “africanizar” la cumbre. Qué lejos se estaba <strong>de</strong> imaginar que la solución a la crisis ambiental estaba en elcontinente <strong>de</strong> don<strong>de</strong> precisamente surgió el género humano.Michelle Bachelet, Directora Ejecutiva <strong>de</strong> ONU Mujeres, en homenaje a Wangari Muta Maathai <strong>de</strong>claró ese domingo25 septiembre: “Nos unimos a muchos en África y en todo el mundo para llorar su fallecimiento y para celebrar su vida como lí<strong>de</strong>rexcepcional, primera mujer africana en recibir el Premio Nobel <strong>de</strong> la Paz. La Profesora Maathai se <strong>de</strong>claró, con valentía y siendovíctima <strong>de</strong> acosos y ataques, a favor <strong>de</strong> la protección <strong>de</strong>l medio ambiente y <strong>de</strong>l progreso <strong>de</strong> los <strong>de</strong>rechos <strong>de</strong> las mujeres, <strong>de</strong> lalucha contra la <strong>de</strong>sertificación, la escasez <strong>de</strong> agua y el hambre en el medio rural.” Bachelet exaltó sobre todo su figura <strong>de</strong> lí<strong>de</strong>rextraordinaria que a través <strong>de</strong>l impulso <strong>de</strong> la reforestación empo<strong>de</strong>ró a miles <strong>de</strong> mujeres y alentó con pasión una nueva manera <strong>de</strong>pensar y actuar, que combina la <strong>de</strong>mocracia y el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo sostenible. Lí<strong>de</strong>r intrépida, fue don<strong>de</strong> nadie había osado ir y <strong>de</strong>safió aautorida<strong>de</strong>s a quienes pocos osaban <strong>de</strong>safiar. Rehusando ser intimidada, se mantuvo firme sobre la plena participación <strong>de</strong> las mujeresen la vida cívica y pública: hoy nos <strong>de</strong>ja un legado que permanecerá para siempre con nosotros. Sus i<strong>de</strong>as innovadoras sobre lacreación <strong>de</strong> empleo, gracias al restablecimiento medioambiental, forman parte <strong>de</strong> la agenda mundial <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>sarrollo en materia <strong>de</strong>trabajos y <strong>de</strong> una economía ver<strong>de</strong>s, en el contexto <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>sarrollo sostenible y <strong>de</strong> la erradicación <strong>de</strong> la pobreza. ParaBachelet, la Dra. Maathai inspirará, especialmente, la preparación para la Conferencia <strong>de</strong> la ONU sobre Desarrollo Sostenibleque se celebrará en Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro en junio <strong>de</strong> 2012.Madame Wangari fue una pionera <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> su época universitaria, cuando obtuvo la licenciatura en Biología en Atchison, Kansas,EE.UU. y al ampliar sus estudios en Pittsburgh, Alemania y en la Universidad <strong>de</strong> Nairobi, siendo en 1971, la primera mujer <strong>de</strong>África Central y Oriental en obtener un doctorado. Nació en Nyeri, Kenia, madre <strong>de</strong> tres hijos, diputada y ministra adjunta para Medioambiente, Recursos Naturales y Vida Silvestre. También en el ámbito privado, rompió con una sociedad que relega a la mujer. Sumarido, un antiguo parlamentario, se divorció <strong>de</strong> ella en 1980 con el argumento <strong>de</strong> que “era <strong>de</strong>masiada educada, con amplio caráctery éxito para po<strong>de</strong>r controlarla”. Su mayor contribución fue el Movimiento Cinturón Ver<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> Kenia, un proyecto que impulsó3

en 1977 y que combina la promoción <strong>de</strong> la biodiversidadcon la <strong>de</strong>l empleo a mujeres. Productos <strong>de</strong> esta iniciativa son30 millones <strong>de</strong> árboles plantados en su país y la ocupación<strong>de</strong> 50 mil mujeres pobres en diferentes viveros. Des<strong>de</strong> 1986,dicho movimiento originó una gran red panafricana que hallevado proyectos similares a países como Tanzaniay Etiopía. “Si uno <strong>de</strong>sea salvar el entorno, primero hay queproteger al pueblo. Si somos incapaces <strong>de</strong> preservar la especiehumana, ¿qué objeto tiene salvaguardar las especiesvegetales?”, <strong>de</strong>claró al resumir su filosofía, que expusomás <strong>de</strong> una vez en la tribuna <strong>de</strong> la se<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> la Organización<strong>de</strong> las Naciones Unidas (ONU).En su época como directora <strong>de</strong>l Departamento <strong>de</strong> AnatomíaVeterinaria en Nairobi (1976-1977), empezó su activida<strong>de</strong>n el Consejo <strong>Nacional</strong> <strong>de</strong> Mujeres <strong>de</strong> Kenia, organizaciónque presidió entre 1981 y 1987. Promotora <strong>de</strong> cancelarla <strong>de</strong>uda externa <strong>de</strong>l Tercer Mundo, <strong>de</strong>stacó como <strong>de</strong>cididaopositora al régimen dictatorial <strong>de</strong> Daniel Arap Moi, porlo cual, durante la década <strong>de</strong> 1990, se le <strong>de</strong>tuvo y encarceló.En 1997 fue candidata a la presi<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> Kenia, pero supartido retiró su candidatura días antes <strong>de</strong> las elecciones. Unaño <strong>de</strong>spués, li<strong>de</strong>ró la oposición a un proyecto gubernamental<strong>de</strong> construcción en la selva lo que <strong>de</strong>senca<strong>de</strong>nó una revueltapopular que fue duramente reprimida por el gobierno, actoque recibió el repudio nacional e internacional, en respuestaa su convocatoria. Su compromiso se recompensó conuna profusión <strong>de</strong> premios, como el <strong>de</strong> Mujeres <strong>de</strong>l Mundo<strong>de</strong> Women Aid (1989), el <strong>de</strong> la Fundación EcologistaGoldman (1991) –el llamado Nobel <strong>de</strong> los ecologistas–,el Premio África <strong>de</strong> Naciones Unidas (1991) o el Petra Kelly(2004). Para el Comité Nobel, la paz en la tierra <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong><strong>de</strong> la capacidad para asegurar el ambiente, y Maathaise sitúa al frente <strong>de</strong> la lucha en la promoción <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>sarrolloeconómico, cultural y ecológicamente viable <strong>de</strong> África,con una visión planetaria <strong>de</strong> lo sostenible que abraza la<strong>de</strong>mocracia, los <strong>de</strong>rechos humanos y, en particular, los <strong>de</strong>la mujer.Pensaba <strong>de</strong> forma global y actuaba en el ámbito local, elmovimiento Cinturón Ver<strong>de</strong>, es un programa que combinaexistencia comunitaria y protección ambiental, al propagar entrecampesinos la i<strong>de</strong>a básica <strong>de</strong> que plantar árboles mejora susvidas y la <strong>de</strong> sus hijos. Su quehacer en el mundo sub<strong>de</strong>sarrolladocombinó ciencia, compromiso social y política activa. Protegerbosques a través <strong>de</strong> la educación, la planificación familiar,la nutrición y la lucha contra la corrupción. Su propuestatambién compete el otorgamiento <strong>de</strong> la responsabilidad <strong>de</strong> unproceso <strong>de</strong> autogestión <strong>de</strong> las mujeres, que ni <strong>de</strong>recho a lapropiedad tenían en Kenia. Su lucha contribuyó a generar unasensibilización <strong>de</strong> la población sobre su <strong>de</strong>recho a oponerseal abuso <strong>de</strong>l po<strong>de</strong>r. La campaña contra la apropiaciónilegal <strong>de</strong> terrenos públicos y bosques, para su urbanización, legranjeó la enemistad <strong>de</strong>l presi<strong>de</strong>nte Daniel Arap Moi, quien lacalificó <strong>de</strong> “perturbada y amenaza a la seguridad <strong>de</strong>l país”.Y en otra vertiente, Wangari Muta Maathai es una expresión<strong>de</strong> la poesía africana, una oportunidad para apurar en laespiritualidad y la sabiduría <strong>de</strong> un continente que es, en símismo, erupción milenaria -selva, <strong>de</strong>sierto, ríos- almas que danzany veneran a sus antepasados. Pero también, muy lamentablemente,una tierra ultrajada por la violencia y el racismo. Empero, apesar <strong>de</strong>l intenso dolor y <strong>de</strong> las heridas continuas subsiste elcanto <strong>de</strong> sus poetas –y Wangari lo es–, que preservanla belleza, la religiosidad y el nativo que nos vuelve aenseñar a la nueva humanidad. En su misión llevó siempre elmejorar la situación <strong>de</strong> las mujeres rurales pobres. Creyó enla inmensa fuerza femenina y trabajó duro para movilizar a lasmujeres pobres. Esta creencia i<strong>de</strong>alizada, la experta enciencias ambientales Lalitha la i<strong>de</strong>ntifica en el poema“Las mujeres se siembran” <strong>de</strong> Halldis Moren:La mujer es la plantación <strong>de</strong> un árbol en el mundo.De rodillas, como si alguien en la oración,entre los restos <strong>de</strong> los muchos árbolesque la tormenta se ha roto.Ella <strong>de</strong>be intentarlo <strong>de</strong> nuevo, tal vez uno al finse <strong>de</strong>jará <strong>de</strong> crecer en paz.Ella ve las manos extendidas sobre la tierracomo si estuviera tratando <strong>de</strong> imponer la calmaPor su temor. Oh muerte! La Tierra, estar quieto,Estad quietos, así que mi árbol pue<strong>de</strong> crecer.En su conferencia nobel esta mujer africana, primera enrecibir el Premio, <strong>de</strong>clara que espera animar a mujeres y niñasa levantar la voz y tener más espacio para el li<strong>de</strong>razgo.Reconoce el trabajo <strong>de</strong> innumerables personas y grupos entodo el mundo. Quienes trabajan en silencio y, a menudo, sin elmenor reconocimiento, protegiendo el ambiente,promoviendo la <strong>de</strong>mocracia, <strong>de</strong>fendiendo los <strong>de</strong>rechoshumanos y garantizando la igualdad, sembrando semillas4

<strong>de</strong> paz, a todos ellos les obsequia el premio, no solo paraque se sientan representados, sino para que lo utilicen en promoversu misión y cumplir con las expectativas <strong>de</strong> este mundo,que será suyo. También agra<strong>de</strong>ce a sus conciudadanos“…que permanecieron tercamente con la esperanza <strong>de</strong> quela <strong>de</strong>mocracia pudiera hacerse realidad y su entorno gestionado<strong>de</strong> forma sostenible…” reconociéndose producto <strong>de</strong> esta lucha.Resalta Wangari en el Comité Nobel un reconocimiento <strong>de</strong>que la paz pasa obligadamente por el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo sostenible yeste se finca en la <strong>de</strong>mocracia, es una i<strong>de</strong>a cuyo momentoha llegado.Recuerda como fue testigo, <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> su infancia, <strong>de</strong> la<strong>de</strong>vastación <strong>de</strong> los bosques y la privatización <strong>de</strong> las tierras,que acaban con la biodiversidad local y sus funcionesecológicas. En 1977, cuando comenzó el Movimiento <strong>de</strong>lCinturón Ver<strong>de</strong>, en parte fue una respuesta a las necesida<strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> las mujeres rurales, la falta <strong>de</strong> leña, agua potable, unaalimentación equilibrada, vivienda y <strong>de</strong> ingresos. A lo largo<strong>de</strong> África, las mujeres son las cuidadoras primarias, conresponsabilidad significativa para el cultivo <strong>de</strong> la tierra yalimentar a sus familias. Son las primeras en tomar conciencia<strong>de</strong>l daño ambiental, que vuelve a los recursos escasos yoriginan que no puedan sostener a sus familias. Las respuestascapitalistas, como la introducción <strong>de</strong> la agricultura comercialy el comercio internacional controlado por el precio <strong>de</strong> lasexportaciones, no garantizan <strong>de</strong> forma razonable y justa elingreso <strong>de</strong> los agricultores a pequeña escala. Narra cómo llegóa enten<strong>de</strong>r que cuando el ambiente es <strong>de</strong>struido o saqueadose socava el futuro <strong>de</strong> las generaciones veni<strong>de</strong>ras.Así, la plantación <strong>de</strong> árboles se convirtió en una opciónnatural para hacer frente a necesida<strong>de</strong>s básicas inicialesi<strong>de</strong>ntificadas por las mujeres. A<strong>de</strong>más, la reforestaciónes simple, asequible y garantiza resultados rápidos y exitosos<strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> un plazo razonable. Esto mantiene el interés y elcompromiso. Así que, las mujeres plantaron más <strong>de</strong> 30 millones<strong>de</strong> árboles que proveen <strong>de</strong> combustible, alimentos, vivienday los ingresos para apoyar la educación <strong>de</strong> sus hijos y lasnecesida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>l hogar. La actividad también generóempleos y mejoró los suelos y las cuencas hidrográficas. Através <strong>de</strong> su participación, las mujeres adquieren po<strong>de</strong>rsobre sus vidas y la <strong>de</strong> sus familias, especialmente <strong>de</strong> suposición social y económica.Prosigue en su conferencia, el trabajo era difícil porquehistóricamente el pueblo había sido persuadido <strong>de</strong> que porsu condición <strong>de</strong> pobre, no solo carecía <strong>de</strong> capital, sino <strong>de</strong>lconocimiento y las habilida<strong>de</strong>s para hacer frente asus <strong>de</strong>safíos; y en cambio, estaba condicionado a creer quelas soluciones a sus problemas <strong>de</strong>bían venir <strong>de</strong> “afuera”.Sin embargo, las mujeres se percataban <strong>de</strong> que la solución<strong>de</strong> sus requerimientos <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> que su entorno esté sano ybien gestionado; siendo conscientes –en carne propia- <strong>de</strong> queun ambiente <strong>de</strong>gradado conduce a una lucha por los recursosescasos, que culmina en la guerra. Incluso intuían las injusticias <strong>de</strong>los acuerdos económicos internacionales. Con el fin <strong>de</strong> ayudara las comunida<strong>de</strong>s para enten<strong>de</strong>r estas relaciones, la galardonadaexplica como se <strong>de</strong>sarrolló un programa <strong>de</strong> educaciónciudadana, en el cual las personas i<strong>de</strong>ntifican sus problemas,las causas y posibles soluciones. Progresivamente, establecenconexiones entre sus propias acciones y los problemas <strong>de</strong>l mediosocial. Se enteran como afrontar problemas: la corrupción, laviolencia contra las mujeres y los niños, la interrupción yruptura <strong>de</strong> las familias; así como, la <strong>de</strong>sintegración <strong>de</strong> lasculturas y comunida<strong>de</strong>s. También i<strong>de</strong>ntifican el abuso<strong>de</strong> drogas y sustancias enervantes, especialmente entre losjóvenes, así como enfermeda<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>vastadoras y que ocurren enproporciones epidémicas, <strong>de</strong> particular preocupación son el SIDA,el paludismo y la <strong>de</strong>snutrición. Así mismo, llama la atención sobrela grave afectación humana por la <strong>de</strong>strucción generalizada<strong>de</strong> los ecosistemas, empero <strong>de</strong> manera prepon<strong>de</strong>rantepor la inestabilidad climática y la contaminación en los suelosy las aguas que acentúan una atroz pobreza. En el proceso,se <strong>de</strong>scubren parte <strong>de</strong> las soluciones, <strong>de</strong>scubren su potencialoculto encontrando amplias faculta<strong>de</strong>s para superar la inerciay entrar en acción. Llegan a reconocer que los habitantesrurales son los principales guardianes y beneficiarios <strong>de</strong>l medioambiente que los sostienen. Comunida<strong>de</strong>s enteras tambiénllegan a enten<strong>de</strong>r que, si bien, es necesario responsabilizar asus gobiernos, es igualmente importante, que en sus relacionescon los <strong>de</strong>más, ejemplifiquen los valores <strong>de</strong> li<strong>de</strong>razgo que<strong>de</strong>sean ver en sus propios dirigentes, es <strong>de</strong>cir, la justicia, laintegridad y la confianza. Aunque inicialmente las activida<strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong>l Movimiento <strong>de</strong>l Cinturón Ver<strong>de</strong> no se refirieron alos problemas <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>mocracia y la paz, pronto quedó claroque el manejo responsable <strong>de</strong>l ambiente era imposible sin unamplio espacio <strong>de</strong>mocrático. Por lo tanto, el árbol se convirtióen un símbolo <strong>de</strong> la lucha <strong>de</strong>mocrática en Kenia.5

esperanza y nuestro futuro. El enfoque holístico <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>sarrollo,como lo <strong>de</strong>muestra el Movimiento Cinturón Ver<strong>de</strong>, podría seradoptado y replicado en varias partes <strong>de</strong> África, y más allá.”Y volvió a su niñez cuando bebía agua <strong>de</strong> los ríos, jugabaentre las hojas <strong>de</strong> “arrurruz” y trataba <strong>de</strong> atraparrenacuajos. Ahora ese mundo <strong>de</strong> sus padres ya no es el <strong>de</strong> susnietos. Las corrientes se han secado, las mujeres caminanlargas distancias para conseguir agua, no siempre limpia, y losniños nunca sabrán lo que han perdido. “El <strong>de</strong>safío consiste enrestaurar la casa <strong>de</strong> los renacuajos y <strong>de</strong>volver a nuestros hijosun mundo bello y maravilloso”.En una entrevista esta noble científica social <strong>de</strong>claró: “Es acausa <strong>de</strong> la conducta inmoral, que hay contaminación en todaspartes; el aire, el agua, la tierra y los alimentos, se han vistogravemente corrompidos <strong>de</strong>bido a una conducta impropia.La contaminación se podría haber evitado. La fuertecaída <strong>de</strong> las virtu<strong>de</strong>s como el amor, la compasión y latolerancia es directamente responsable <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>gradaciónque uno ve hoy en día. De hecho, incluso se podría <strong>de</strong>cir queestos elementos tienen miedo <strong>de</strong>l hombre. La impurezase refleja en la contaminación exterior. La buena conducta <strong>de</strong>be serla base real para la vida. Sin embargo, el hombre mo<strong>de</strong>rnocarece totalmente <strong>de</strong> carácter y virtu<strong>de</strong>s. No es <strong>de</strong> extrañar lapaz y la felicidad se le escapan.”que los problemas primero se resolvían con la fuerza mental,también creía en la asociación humana y que la felicidad seencontraba en la unión. Una vez le preguntaban a un científicoque la conoció ¿cuál creía que era el secreto <strong>de</strong> esa fuente<strong>de</strong> inspiración interminable? Y él respondió: La profesoraMaathai retrata el amor en cada acción suya. El amor erael aliento mismo <strong>de</strong>l nudo <strong>de</strong> unión natural con la progeniever<strong>de</strong>. Cada lucha que acometió pone <strong>de</strong> relieve el amor puroe incondicional y sin mancha que formó la base <strong>de</strong> sus obrasaltruistas. Su vida y su obra representan la frase “El amor es el<strong>de</strong>sinterés y el yo es falta <strong>de</strong> amor ‘.Cuando recibió la llamada, con la que le comunicaron quehabía recibido el premio nobel, Wangari <strong>de</strong>tuvo el automóvilen un hotel que encontró <strong>de</strong> camino a uno <strong>de</strong> tantos pueblosque apoyaba con sus proyectos <strong>de</strong> conservación forestal ypidió permiso para plantar un árbol que celebrara elacontecimiento. Ese árbol fue un Tulipán Africano.Carlos Mallén RiveraEditor en JefeLa Dra.Wangari Maathai promovió iniciativas queincluyeron la protección <strong>de</strong> los ecosistemas tropicales <strong>de</strong> lacuenca <strong>de</strong>l Congo, siendo embajadora itinerante <strong>de</strong>esta región <strong>de</strong> acceso global para la diversidad biológicay penosamente amenazados por la tala ilegal, la exploraciónminera, la caza furtiva y el comercio <strong>de</strong> animales silvestres.En la construcción <strong>de</strong> su cruzada para proteger losbosques, la profesora Maathai se enteró <strong>de</strong> un plan <strong>de</strong>lgobierno para privatizar gran<strong>de</strong>s áreas <strong>de</strong> tierra en el bosqueKarura. Ella protestó en contra <strong>de</strong> un plan <strong>de</strong> industrialización<strong>de</strong>l Congo, como lo hizo por muchos otros proyectos <strong>de</strong> estetalante, incluso con el visto bueno <strong>de</strong> gobiernos y sociedad,<strong>de</strong>cía: “No po<strong>de</strong>mos <strong>de</strong>sarrollar nuestros países, si vamosa seguir la corrupción en ambos lados”. Ella tenía notabletolerancia, paciencia y perseverancia, tomó enormesriesgos personales para luchar por la justicia, así como porlos <strong>de</strong>rechos humanos y <strong>de</strong>l medio ambiente. Ella consi<strong>de</strong>róCarlos Galindo (2010) Flor <strong>de</strong> Tulipan africano.Spatho<strong>de</strong>a campanulata Deauv“The living conditions of the poor must be improved if wereally want to save our environment”Wangari Maathai, Premio Nobel <strong>de</strong> la Paz 2004.7

Wangari Muta Maathai. Dominio público.8

RESUMENMODELOS PARA ESTIMACIÓN Y DISTRIBUCIÓN DE BIOMASA DEAbies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham. EN PROCESO DE DECLINACIÓNBIOMASS ESTIMATION AND DISTRIBUTION MODELS OFAbies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham. IN DECLINEPatricia Flores-Nieves 1 , Miguel Ángel López-López 1 , Gregorio Ángeles–Pérez 1 ,María <strong>de</strong> Lour<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> la Isla-Serrano 2 y Germán Calva-Vásquez 3Actualmente, el gobierno fe<strong>de</strong>ral promueve el pago por captura <strong>de</strong> carbono en los bosques para mitigar el calentamiento global.Por ello, existe la necesidad <strong>de</strong> estimar la biomasa y tasas <strong>de</strong> captura <strong>de</strong> carbono en los bosques <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa. En este estudiose generaron mo<strong>de</strong>los para calcular la biomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste, <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y <strong>de</strong> acículas <strong>de</strong> árboles completos y <strong>de</strong> ramas <strong>de</strong>oyamel en rodales <strong>de</strong>l Cerro Tláloc, Texcoco, Estado <strong>de</strong> México. Para el caso <strong>de</strong> árboles completos, la biomasa estuvo en función <strong>de</strong>ldiámetro normal (DN), mientras que para ramas individuales fue una función <strong>de</strong>l diámetro basal (DB). El uso <strong>de</strong> los mo<strong>de</strong>los generadosa nivel árbol se recomienda para árboles con DN entre 12 y 105 cm, n cambio los mo<strong>de</strong>los a nivel <strong>de</strong> ramas se recomiendan paradiámetros basales entre 1 y 120 mm. El mo<strong>de</strong>lo para fustes fue <strong>de</strong> tipo potencial y los <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y follaje <strong>de</strong> árbolescompletos <strong>de</strong> tipo exponencial. Los coeficientes <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminación <strong>de</strong> los mo<strong>de</strong>los a nivel árbol indican que existe una consi<strong>de</strong>rablevariabilidad, principalmente, en las biomasas <strong>de</strong> ramas, lo que pue<strong>de</strong> ser consecuencia <strong>de</strong>l proceso <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación en la zona<strong>de</strong> estudio. La biomasa total <strong>de</strong> los árboles se distribuye en forma atípica entre los compartimentos aéreos: 97 % en los fustes, 3 % enma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y 0.07 % en follaje. Este patrón <strong>de</strong> distribución <strong>de</strong> biomasa refleja el efecto <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>terioro <strong>de</strong> los bosques<strong>de</strong> A. religiosa.Palabras clave: Fuste, rama, acículas, ecuación alométrica, oyamel, productividad primaria neta.ABSTRACTAt present, the fe<strong>de</strong>ral government promotes a payment for carbon sequestration by forests to mitigate global change. This is whythere exists a need for estimating biomass and carbon sequestration rates in Abies religiosa forests. In this study stem, branch woodand needle biomass estimation mo<strong>de</strong>ls were generated for whole A. religiosa trees and branches in stands at Cerro Tláloc, Texcoco,Estado <strong>de</strong> México. For whole trees biomass was a function of breast height diameter (BHD), and for individual branches, biomasswas a function of basal diameter (BD). Use of tree-level mo<strong>de</strong>ls is suitable for trees with BHD within the range of 12 and 105 cm,and branch-level mo<strong>de</strong>ls are recommen<strong>de</strong>d for BD within 1 and 120 mm. Stem mo<strong>de</strong>ls were potential while tree-level branchwood and foliage ones were exponential. Determination coefficients for whole-tree mo<strong>de</strong>ls show that there exists a large variability,especially for branch biomass, which is likely to be a result of the <strong>de</strong>cline process taking place in the study area. Total tree biomass isatypically distributed within aboveground tree components: 97 % corresponds to stems, 3 % to branch-wood and 0.07 % to foliage.This biomass distribution pattern may be a reflection of the <strong>de</strong>cline process affecting A. religiosa in the study area.Key words: Stem, branch, needle, allometric equation, Sacred-fir, net primary productivity.Fecha <strong>de</strong> recepción: 5 <strong>de</strong> febrero 2010Fecha <strong>de</strong> aceptación: 25 <strong>de</strong> julio <strong>de</strong> 20111Posgrado Forestal, Colegio <strong>de</strong> Posgraduados. Correo-e: floresnp@colpos.mx2Posgrado <strong>de</strong> Hidrociencias, Colegio <strong>de</strong> Posgraduados.3Facultad <strong>de</strong> Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, UNAM.

Rev. Mex. Cien. For. <strong>Vol</strong>. 2 Núm. 8INTRODUCCIÓNLa conversión <strong>de</strong> los bosques maduros en áreas abiertaspara diferentes usos económicos <strong>de</strong>l suelo, como agriculturao gana<strong>de</strong>ría, es un fenómeno que se ha presentado a lolargo <strong>de</strong> los últimos siglos (Herrera et al., 2001). Los bosquesestán <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> los ecosistemas naturales con mayorproducción primaria neta. Se calcula que producen <strong>de</strong>400 a 1,000 g m -2 año -1 <strong>de</strong> carbono, cantidad dos vecessuperior a la <strong>de</strong> los pastizales y varias veces mayor que la <strong>de</strong>los océanos (Waring y Schlesinger, 1985). Una parte <strong>de</strong> estaproducción se acumula como biomasa y humus, que constituyenla producción primaria neta. La otra parte se <strong>de</strong>stina a procesos<strong>de</strong> mantenimiento <strong>de</strong>l ecosistema, a través <strong>de</strong> la respiración(Escandón et al., 1999).Garzuglia y Saket (2003) <strong>de</strong>finen la biomasa aérea comola cantidad total <strong>de</strong> materia orgánica aérea presente en losárboles, e incluyen hojas, ramas, tronco principal y corteza.Para la estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa, el procedimiento más comúnconsiste en el muestreo <strong>de</strong>structivo <strong>de</strong> unos cuantos árbolespara <strong>de</strong>spués mo<strong>de</strong>lar el contenido <strong>de</strong> biomasa en función<strong>de</strong> variables fáciles <strong>de</strong> medir, para ello se utilizan métodos <strong>de</strong>regresión (Díaz et al., 2007).La biomasa se ha convertido en un elemento importante enlos estudios sobre los cambios que ocurren a escala mundial,dado el posible efecto atenuador (sumi<strong>de</strong>ro <strong>de</strong> carbono) quelos bosques pue<strong>de</strong>n tener al secuestrar los exce<strong>de</strong>ntes <strong>de</strong> losgases <strong>de</strong> efecto inverna<strong>de</strong>ro, <strong>de</strong> un modo temporal (biomasa)y permanente (suelo) y a las consecuencias que se <strong>de</strong>rivan <strong>de</strong>la modificación <strong>de</strong> las condiciones climáticas sobre lasalud, estructura y biodiversidad <strong>de</strong> un sistema forestal(Vidal et al., 2004).Las ecuaciones <strong>de</strong> biomasa permiten estimar, con bastanteexactitud, el peso <strong>de</strong> las especies forestales a partir <strong>de</strong> unnúmero reducido <strong>de</strong> parámetros <strong>de</strong> los árboles en pie (Lópezy Keyes, 1987; Castellanos et al., 1996; Rojo et al., 2005). Sinembargo, la disponibilidad <strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>los para coníferascomo Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham. es reducida. EnMéxico se han <strong>de</strong>sarrollado ecuaciones para Pinus montezumaeLamb. (Garcidueñas, 1987; Manzano et al., 2007; López-Lópezet al., 2009), Pinus cembroi<strong>de</strong>s Zucc. (López y Keyes, 1987), Pinuspatula Schltdl. et Cham. (Castellanos et al., 1996), Alnus glabrataFernald, Clethra hartwegii Britt., Rapanea myricoi<strong>de</strong>s (Schltdl.)Lun<strong>de</strong>ll, Quercus peduncularis Née, Liquidambar macrophyllaOerst e Inga sp. (Acosta et al., 2002), Hevea brasiliensis Müll.Arg. (Rojo et al., 2005) y para Abies religiosa (Avendaño et al., 2009).Los mo<strong>de</strong>los para el cálculo <strong>de</strong> la biomasa <strong>de</strong> árbolesestán influenciados por los cambios en la estructura, comoconsecuencia <strong>de</strong>l manejo, presencia <strong>de</strong> plagas y enfermeda<strong>de</strong>s,condiciones climáticas, <strong>de</strong> suelo o incluso factores genéticos.INTRODUCTIONThe conversion of old forests into open areas for differenteconomic land use such as agriculture or livestock farming hasoccurred during the last centuries (Herrera et al., 2001).Forests are one of the natural ecosystems with highest netprimary production. It has been calculated that they produce from400 to 1,000 g m -2 year -1 C, which is an amount twice higherthan grasslands and several more than that of oceans (Waringand Schlesinger, 1985). One part of production accumulates asbiomass and humus, which constitute the net primary production.The other part is bound to maintenance process of theecosystem, through respiration (Escandón et al., 1999).Garzuglia and Saket (2003) <strong>de</strong>fine aerial biomass as thetotal amount of aerial organic matter in trees, including leaves,branches main stem and bark. The most regular procedurefor biomass estimation is <strong>de</strong>structive sampling of some trees fora later mo<strong>de</strong>ling of biomass content in terms of easilymeasurable variables, in which regression methods are used(Díaz et al., 2007).Biomass has become an important element in studiesabout changes that occur world-wi<strong>de</strong>, from the possiblemitigating effect (carbon sink) of forests when they performthe sequestration of the exceeding greenhouse- effect gases,in a temporary (biomass) or permanent (soil) way and to theconsequences of the changing climate conditions upon health,structure and biodiversity of a forest system (Vidal et al., 2004).Biomass equations allow a rather accurate estimationof the weight of forest species from a small number ofstanding-tree parameters (López and Keyes, 1987; Castellanoset al., 1996; Rojo et al., 2005). However, the availability ofmo<strong>de</strong>ls for softwoods such as Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl.et Cham. is rather small. Some equations have been <strong>de</strong>velopedin Mexico for Pinus montezumae Lamb. (Garcidueñas, 1987; Manzanoet al., 2007; López-López et al., 2009), Pinus cembroi<strong>de</strong>s Zucc.(López y Keyes, 1987), Pinus patula Schltdl. et Cham. (Castellanoset al., 1996), Alnus glabrata Fernald, Clethra hartwegii Britt.,Rapanea myricoi<strong>de</strong>s (Schltdl.) Lun<strong>de</strong>ll, Quercus peduncularisNée, Liquidambar macrophylla Oerst e Inga sp. (Acosta et al.,2002), Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg. (Rojo et al., 2005), as wellas for Abies religiosa (Avendaño et al., 2009).Mo<strong>de</strong>ls for tree biomass are influenced by changes instructure, as a consequence of management, plagues anddiseases, climate, soil and even some genetic factors.Forest <strong>de</strong>cline is <strong>de</strong>fined as a multifactor sickness caused bybiotic and abiotic agents that generates a <strong>de</strong>crease of vigorand survival of trees (Granados et al., 2001 and Vázquez etal., 2004). Ciesla (1989) and Granados et al. (2001) point outthat there are symptoms related to this phenomenon, among10

Flores-Nieves et al., Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación y distribución...La <strong>de</strong>clinación forestal se <strong>de</strong>fine como una enfermedadmultifactorial causada tanto por agentes abióticos comobióticos, lo que implica la reducción <strong>de</strong>l vigor y supervivencia<strong>de</strong> los árboles (Granados et al., 2001 y Vázquez et al., 2004).Ciesla (1989) y Granados et al. (2001) y López et al. (2006) señalanque son varios los síntomas relacionados con dicho fenómeno,tales como la reducción <strong>de</strong>l crecimiento, <strong>de</strong>generación <strong>de</strong> lossistemas radicales, clorosis en el follaje, reducción <strong>de</strong>las reservas fotosintéticas, mortalidad <strong>de</strong> brotes y ramase incremento <strong>de</strong> la inci<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> ataques <strong>de</strong> insectos, que sepresentan <strong>de</strong> manera secuencial o simultánea. Alvarado et al.(1993) citan que pue<strong>de</strong> alterarse la forma cónica <strong>de</strong> la copa ygenerarse <strong>de</strong>foliación severa y muerte <strong>de</strong> ramas en las partesbajas <strong>de</strong>l árbol. Al momento <strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>lar las variables <strong>de</strong>los árboles o ecosistemas sujetos a este proceso <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación,se espera que todos los síntomas mencionados tengan un efectodirecto en los parámetros <strong>de</strong> los mo<strong>de</strong>los generados.El objetivo <strong>de</strong> este estudio fue aportar nuevos mo<strong>de</strong>los parala estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> los componentes aéreos<strong>de</strong> A. religiosa en bosques afectados por el proceso <strong>de</strong><strong>de</strong>clinación, como es el caso <strong>de</strong> algunos bosques cercanos alValle <strong>de</strong> México. Se preten<strong>de</strong> que las ecuaciones sirvan comoherramienta para la realización <strong>de</strong> estudios <strong>de</strong> productividadprimaria neta, captura <strong>de</strong> carbono y <strong>de</strong> distribución <strong>de</strong>biomasa en bosques que se encuentren en dicha condición.MATERIALES Y MÉTODOSÁrea <strong>de</strong> estudioEl presente trabajo se llevó a cabo en el Cerro Tláloc, en laregión fisiográfica conocida como Sierra Nevada, que se ubicaal oriente <strong>de</strong>l Estado <strong>de</strong> México (Figura 1). La elevación <strong>de</strong>lcerro es <strong>de</strong> 4,120 m y el área <strong>de</strong> estudio se localiza en lavertiente occi<strong>de</strong>ntal <strong>de</strong>l mismo, en dón<strong>de</strong> la especie dominantees A. religiosa.Clima.- A lo largo <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>clive occi<strong>de</strong>ntal <strong>de</strong>l Cerro Tláloc sedistinguen tres subtipos climáticos: en las áreas planas máscercanas a los lomeríos el clima es C (w 0) (w) b(i´); templadosubhúmedo con una precipitación media anual <strong>de</strong> 700 mm, conrégimen <strong>de</strong> lluvia en verano, temperatura media anual entre12 y 18 °C y con una oscilación térmica <strong>de</strong> 5 a 7 °C. En la zona<strong>de</strong> lomeríos, hacia las estribaciones <strong>de</strong> la Sierra <strong>de</strong> Río Fríoel clima es C (w 1) (w) b(i´); templado subhúmedo, con unaprecipitación media anual entre 800 y 900 mm, régimen <strong>de</strong> lluviasen verano, con temperatura media anual entre 12 y 18 °C y conuna oscilación térmica <strong>de</strong> 5 a 7 °C. En las la<strong>de</strong>ras montañosasel clima es <strong>de</strong> tipo C(w 2) (w) b(i´); templado subhúmedo, con unaprecipitación media anual entre 900 y 1,200 mm, régimen <strong>de</strong>lluvias en verano, temperatura media anual <strong>de</strong> 10 y 14 °C, conuna oscilación térmica <strong>de</strong> 5 a 7 °C. Las fluctuaciones climáticas se<strong>de</strong>ben a la orografía (Ortíz y Cuanalo, 1977).which are a reduction in growth, <strong>de</strong>generation of the rootsystem, foliage chlorosis, diminishment of photosyntheticreserves, shoot and branch mortality and an incrementof insect attack, all of which could act sequentially orsimultaneously. Alvarado et al. (1993) stated that the conic shapeof the crown can change and generate an intensive <strong>de</strong>foliationand <strong>de</strong>ath of the lower branches. At the time of mo<strong>de</strong>lingthe tree variables or ecosystems subjected to <strong>de</strong>cline, itis expected that all the aforementioned symptoms have adirect effect on the parameter of the generated mo<strong>de</strong>ls.The aim of this study was to provi<strong>de</strong> new mo<strong>de</strong>ls for biomassestimation of the aerial components of A. religiosa in forests in<strong>de</strong>cline, as some nearby Valle <strong>de</strong> Mexico are. It is expectedthat these equations might be useful to accomplish net primaryproductivity, carbon sequestration and of biomass distributionstudies in forests that are in this condition.MATERIALS AND METHODSStudy areaThe study here <strong>de</strong>scribed was carried out in Cerro Tláloc(Tlaloc Hill), in Sierra Nevada that lies at the East of Estado <strong>de</strong>México (Figure 1). The highest altitu<strong>de</strong> is 4,120 m and the studyarea is located in the western hillsi<strong>de</strong>, where A. religiosa is thedominant species.Climate.- Along the western fall of Cerro Tlaloc, three climatesubtypes can be found: in the closest plains to the hills, the type ofweather is C (w 0) (w) b(i´), which is a subhumid temperateclimate with 700 mm of annual mean precipitation,summer rainfall, annual average temperature between12 and 18 °C and a thermic oscilation from 5 to 7 °C. In the hillzone, nearby Río Frio Mountain Range, the weather is C (w 1)(w) b(i´) which is a subhumid temperate climate with 800-900 mmof annual mean precipitation, summer rainfall, annual averagetemperature between 12 and 18 °C and a thermic oscilation from5 to 7 °C. In the hillsi<strong>de</strong>s, the weather is of the C(w 2) (w) b(i´) type,which is a subhumid temperate climate with 900 and 1200 mmof annual mean precipitation, summer rainfall, annual averagetemperature between 10 and 18 °C and a thermic oscilationfrom 5 to 7 °C Climatic fluctuations are due to orography (Ortízand Cuanalo, 1977).Soils.- According to Mooser (1975), the edaphic material ofValle <strong>de</strong> México was the result of the volcanic activityof the Tertiary and Quaternary periods. The formations of themiddle Tertiary (Oligocene and Miocene) are located fromTláloc up to near San Pablo Ixayoc town. Soils are incipient,of coarse texture near the cineritic cone of Tláloc, and in theresting areas, they are black, <strong>de</strong>ep, of medium texture and richin organic matter and with medium texture (migajones o francos).11

Flores-Nieves et al., Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación y distribución...Mo<strong>de</strong>los para biomasa <strong>de</strong> árboles completosPara generar los mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> árboles completosse seleccionaron 10 individuos <strong>de</strong> diferentes dimensiones, queincluyeron la mayor variabilidad <strong>de</strong> diámetros presentes enla zona (12 a 105 cm). A los árboles ejemplares, se lesmidió el diámetro normal (DN) con una cinta diamétrica yposteriormente fueron <strong>de</strong>rribados.En seguida se le <strong>de</strong>terminó su altura total con unlongímetro <strong>de</strong> 50 m, se <strong>de</strong>sramó y el fuste fue seccionadoen trozas <strong>de</strong> dimensiones comerciales (2.55 m <strong>de</strong> longitud),con una usando una motosierra marca Truper con espada<strong>de</strong> 20”. Durante el troceo <strong>de</strong>l fuste se obtuvo una rodaja <strong>de</strong>aproximadamente cinco centímetros <strong>de</strong> espesor comomuestra <strong>de</strong> cada troza. A cada troza se le midieron losdiámetros inferior y superior con una cinta diamétrica marcaForestry Suppliers Metric Fabric Diameter Tape, mo<strong>de</strong>lo283D/160 cm, con el objeto <strong>de</strong> estimar su volumen. Eldiámetro <strong>de</strong> la base <strong>de</strong> cada una <strong>de</strong> las ramas <strong>de</strong>l árbol semidió con un vernier digital marca Mitutoyo.En campo se obtuvo el peso húmedo <strong>de</strong> cada una <strong>de</strong> lastrozas (cuando fue posible), mediante una báscula marcaOhaus <strong>de</strong> 100 kg <strong>de</strong> capacidad y 50 g <strong>de</strong> precisión.Cuando estas pesaban más <strong>de</strong> 100 kg en húmedo, solo se<strong>de</strong>terminó su volumen con la fórmula <strong>de</strong> Smalian:Don<strong>de</strong>:V = (B + b) / 2*LV = <strong>Vol</strong>umen <strong>de</strong> la troza (m 3 )B, b = Área <strong>de</strong> la sección mayor y menor <strong>de</strong> la troza (m 2 )L = Longitud <strong>de</strong> la troza (m)Las rodajas <strong>de</strong>l fuste se trasladaron en bolsas <strong>de</strong>polietileno al laboratorio <strong>de</strong>l Postgrado Forestal <strong>de</strong>l CampusMontecillo <strong>de</strong>l Colegio <strong>de</strong> Postgraduados, para secarlas a80 °C, hasta alcanzar peso constante en un horno <strong>de</strong> circulaciónforzada marca Felisa mo<strong>de</strong>lo F20. Posteriormente se <strong>de</strong>terminóla relación entre el peso seco y peso húmedo. Esta proporciónse aplicó al peso húmedo total <strong>de</strong> las trozas previamentepesadas en campo, para <strong>de</strong>terminar su biomasa.Cuando las trozas pesaron más <strong>de</strong> 100 kg, el cálculo <strong>de</strong>su biomasa se realizó <strong>de</strong> manera indirecta, a partir <strong>de</strong> laestimación <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>nsidad <strong>de</strong> la ma<strong>de</strong>ra. Las rodajas extraídas<strong>de</strong> cada troza se utilizaron para calcular la <strong>de</strong>nsidad <strong>de</strong> lama<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> la troza correspondiente.En el laboratorio, las rodajas (o muestras <strong>de</strong> ellas en el caso<strong>de</strong> rodajas muy gran<strong>de</strong>s) se impermeabilizaron con parafinapara obtener su volumen mediante el principio <strong>de</strong> Arquíme<strong>de</strong>s.Para ello se usaron recipientes con agua <strong>de</strong> tamaño a<strong>de</strong>cuadopower saw with a 20” bla<strong>de</strong>. During these operations, a 5 cm thickslice from each log was taken as a sample. To each log weremeasured the lower and upper diameters with a diametrictape, in or<strong>de</strong>r to estimate its volume. The diameter of the baseof each one of the branches was measured with a Mitutoyodigital vernier.In the field was obtained the fresh weight of each log (when itwas possible), with an Ohaus 100 kg scale and 50 g precision.When their wet weight was over 100 kg, volume was only<strong>de</strong>termined with the Smalian formula:Where:V = (B + b) / 2*LV = <strong>Vol</strong>ume of the long (m 3 )B, b = Area of the greatest and smallest section ofthe log (m 2 )L = Length of the log (m)Stem slices were kept into plastic bags and were taken to theForest Graduate Studies Laboratory at Montecillo Campusthat belongs to the Graduate Studies School (Colegio <strong>de</strong>Postgraduados), where they were dried at 80 °C, until theyreached a constant weight in a forced- circulation kiln marcay mo<strong>de</strong>lo. Y por cuánto tiempo Afterwards, the dry weight/wetweight relation was <strong>de</strong>termined. This ratio was applied to thetotal wet weight of the logs previously weighted at the field, inor<strong>de</strong>r to <strong>de</strong>termine biomass.When logs were weighed more than 100 kg, the<strong>de</strong>termination of biomass was carried out in an indirect way,from the estimation of wood <strong>de</strong>nsity. The slices taken fromeach log were used to calculate the wood <strong>de</strong>nsity of thecorresponding log.In the laboratory, the slices (or samples of them when sliceswere too big) were waterproofed with paraffin in or<strong>de</strong>r toget their volume by the Archime<strong>de</strong>s principle. For that ending,containers with water of a right size for the sample volume, whichwere placed on the 100 kg Ohaus scale of 50 g precision, whenbig samples are involved. When samples were small, a 2 kgOhaus and precision of tenth of gram was used. Once thevolume is had, weight was <strong>de</strong>termined in or<strong>de</strong>r to estimate their<strong>de</strong>nsity by the following formula:Where:δm = m/vδm = Density of wet wood (kg m -3 )m = Mass (kg)v = <strong>Vol</strong>ume (m 3 )13

Rev. Mex. Cien. For. <strong>Vol</strong>. 2 Núm. 8para el volumen <strong>de</strong> las muestras, se colocaron sobre unabáscula Ohaus <strong>de</strong> 100 kg <strong>de</strong> capacidad y 50 g <strong>de</strong> precisión,en el caso <strong>de</strong> muestras gran<strong>de</strong>s. En el caso <strong>de</strong> las muestraspequeñas se utilizó una balanza Ohaus <strong>de</strong> dos kilogramos <strong>de</strong>capacidad y un décimo <strong>de</strong> gramo <strong>de</strong> precisión. Una vezque se obtuvo el volumen se procedió a <strong>de</strong>terminar su peso,para estimar su <strong>de</strong>nsidad mediante la fórmula:Don<strong>de</strong>:δm = m/vδm = Densidad <strong>de</strong> la ma<strong>de</strong>ra en húmedo (kg m -3 )m = Masa (kg)v = <strong>Vol</strong>umen (m 3 )La biomasa <strong>de</strong> cada muestra o rodaja se <strong>de</strong>terminócolocando las muestras en un horno <strong>de</strong> secado <strong>de</strong> circulaciónforzada marca Felisa mo<strong>de</strong>lo F20 a 80 °C, para eliminar laparafina. Una vez conocidos la <strong>de</strong>nsidad <strong>de</strong> las rodajas y elvolumen <strong>de</strong> las trozas correspondientes, se calculó la biomasa<strong>de</strong> las trozas mediante la fórmula:Don<strong>de</strong>:Bt = δt * vtBt = Biomasa <strong>de</strong> troza (kg)δt = Densidad (kg m -3 )vt = <strong>Vol</strong>umen <strong>de</strong> la troza (m 3 )Con los datos <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> fustes se corrió un procedimiento<strong>de</strong> regresión, para generar un mo<strong>de</strong>lo <strong>de</strong> estimación <strong>de</strong>biomasa <strong>de</strong> ese compartimento en función <strong>de</strong>l diámetro normal.Don<strong>de</strong>:Bf = f (DN)Bf = Biomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste (kg)DN = Diámetro normal (cm)La biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y <strong>de</strong>l follaje se estimó apartir <strong>de</strong>l diámetro basal <strong>de</strong> la rama, para lo cual se utilizaronmo<strong>de</strong>los previamente elaborados por el procedimiento que se<strong>de</strong>scribe a continuación.Mo<strong>de</strong>los para biomasa a nivel <strong>de</strong> ramasEl mo<strong>de</strong>lo para estimar la biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramasindividuales se elaboró a partir <strong>de</strong> 35 ramas <strong>de</strong> diversosdiámetros basales (1 a 120 mm), proce<strong>de</strong>ntes <strong>de</strong> varios árboles<strong>de</strong>l área <strong>de</strong> estudio. A las ramas recolectadas se les <strong>de</strong>terminóThe biomass of every sample or slice was <strong>de</strong>termined byplacing the samples into a marca y mo<strong>de</strong>lo dryingforced-circulation kiln at 80 °C in or<strong>de</strong>r to remove theparaffin. Once the slice <strong>de</strong>nsity and the volume of theirlogs were known, the biomass of the logs was calculated by thefollowing formula:Where:Bt = δt * vtBt = Log biomass (kg)δt = Density (kg m -3 )vt = <strong>Vol</strong>ume of the log (m 3 )With the stem biomass data a regression was run to generatea biomass estimation mo<strong>de</strong>l of that compartment in terms ofthe normal diameter:Where:Bf = f (DN)Bf = Stem biomass (kg)DN = Normal diameter (cm)Branch wood and foliage biomass was estimated from thebasal branch diameter; thus, previously ma<strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>lswere used by the procedure was <strong>de</strong>scribed as follows.Mo<strong>de</strong>ls for biomass at a branch levelThe mo<strong>de</strong>l to estimate wood biomass of individual brancheswas <strong>de</strong>signed from 35 branches of different basaldiameters (1 to 120 mm), taken from several trees of the studyarea. To the collected branches, basal diameter was calculatedwith a Mitutoyo digital vernier caliper, and from them,leaves were pulled apart in the field, and were weighted by aOhaus ES100L scale in wet, wood and foliage separately. Whenbranches surpassed the capacity of the Felisa F20 dryingkiln, slices of wood were taken and several representativesamples, 10 at the most, were weighted in wet. This materialwas taken to the laboratory to be dried at a Felisa F20forced-circulation kiln at 80 y 70 °C, respectively, in or<strong>de</strong>rto <strong>de</strong>termine its moister content by the following equation:Where:CHm = (PHm - PSm) * 100) / PHmCHm =Moisture content of the sample or slice (%)PHm = Wet weight of the sample (g)PSm = Dry weight of the sample (g)14

Flores-Nieves et al., Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación y distribución...su diámetro basal con un vernier digital marca Mitutoyo yposteriormente fueron <strong>de</strong>shojadas en campo y se pesaronen húmedo la ma<strong>de</strong>ra y el follaje por separado, en unabalanza Ohaus ES100L. De la ma<strong>de</strong>ra, cuando las ramassuperaron la capacidad <strong>de</strong>l horno <strong>de</strong> secado marca FelisaF20, se tomaron rodajas, y <strong>de</strong>l follaje se obtuvo un máximo <strong>de</strong>10 muestras representativas que también fueron pesadas enhúmedo. El material se llevó al laboratorio para su secadoen un horno <strong>de</strong> circulación forzada marca Felisa F20 a 80y 70 °C, respectivamente, para <strong>de</strong>terminar su contenido <strong>de</strong>humedad mediante la ecuación:Don<strong>de</strong>:CHm = ((PHm - PSm) * 100) / PHmCHm = Contenido <strong>de</strong> humedad <strong>de</strong> la muestra orodaja (%)PHm = Peso húmedo <strong>de</strong> la muestra (g)PSm = Peso seco <strong>de</strong> la muestra (g)El contenido <strong>de</strong> humedad se aplicó al total <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong>las ramas y follaje para obtener su peso seco, a partir <strong>de</strong> supeso húmedo.Don<strong>de</strong>:Bcr = PHcr – (PHcr * CHcr / 100)Bcr = Biomasa <strong>de</strong>l compartimiento <strong>de</strong> la rama(ma<strong>de</strong>ra o follaje, kg)PHcr = Peso húmedo <strong>de</strong>l compartimiento <strong>de</strong> la rama(ma<strong>de</strong>ra o follaje, kg)CHcr = Contenido <strong>de</strong> humedad <strong>de</strong>l compartimiento<strong>de</strong> la rama (ma<strong>de</strong>ra o follaje, %)Moisture content was applied to the total branch wood andfoliage to get their dry weight from their wet weight.Where:Bcr = PHcr – (PHcr * CHcr / 100)Bcr = Biomass of compartment of the branch (woodor foliage, kg)PHcr = Wet weight of the branch compartment (woodor foliage, kg)CHcr = Moisture content of the branch compartment(wood or foliage, %)By non-linear regression, a mo<strong>de</strong>l was <strong>de</strong>signed to estimatebranch wood and foliage biomass, which were <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ntestimated variables, in terms of the basal diameter of the branch.Where:Bmr = f (Dbr)Bfr = f (Dbr)Bmr = Single branch wood biomass biomass (kg)Bfr = Branch needle biomass (kg)Dbr = Basal diameter of the branch (mm)RESULTS AND DISCUSIONFigures 2 and 3 show the mo<strong>de</strong>ls to estimate wood biomassof single branches (Bmr) and of branch needles (Bfr) ofAbies religiosa. Biomass prediction is according to the basaldiameter of branches (Dbr). Mo<strong>de</strong>ls are recommen<strong>de</strong>d forbranches of 1 to 120 mm in diameter.Mediante el uso <strong>de</strong> la regresión no lineal se procedió agenerar los mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimar la biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong>ramas y la <strong>de</strong> follaje, las cuales fueron las variables <strong>de</strong>pendientesestimadas, en función <strong>de</strong>l diámetro basal <strong>de</strong> la rama.Don<strong>de</strong>:Bmr = f (Dbr)Bfr = f (Dbr)Bmr = biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas individuales (kg)Bfr = biomasa <strong>de</strong> acículas <strong>de</strong> ramas (kg)Dbr = diámetro basal <strong>de</strong> rama (mm)Figura 2. Mo<strong>de</strong>lo <strong>de</strong> estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong>ramas individuales <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosaFigure 2. Mo<strong>de</strong>l to estimate wood biomass of Abies religiosasingle branches.15

Flores-Nieves et al., Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación y distribución...hecho explicaría el menor coeficiente <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminación <strong>de</strong>lmo<strong>de</strong>lo para estimar la biomasa foliar.Las figuras 4, 5 y 6 muestran los mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimarbiomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste, <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y <strong>de</strong> follaje paraárboles completos <strong>de</strong> A. religiosa. La predicción <strong>de</strong>biomasa estuvo en función <strong>de</strong>l DN. Los datos <strong>de</strong> biomasa<strong>de</strong> fuste se ajustaron al mo<strong>de</strong>lo potencial:Don<strong>de</strong>:Bf = 0.0173DN 2.7459Bf = Biomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste (kg)DN = Diámetro normal (cm)Los mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y follaje anivel árbol son <strong>de</strong> tipo exponencial, el <strong>de</strong> ramas:Don<strong>de</strong>:Bmra = 1.5842e 0.044DNBmra = Biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong>l conjunto <strong>de</strong> ramas<strong>de</strong>l árbol (kg)DN = Diámetro normal (cm)El mo<strong>de</strong>lo <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> follaje a nivel árbol:Don<strong>de</strong>:Bfa = 0.8413e 0.0398DNBfa = Biomasa <strong>de</strong> follaje a nivel árbol (kg)DN = Diámetro normal (cm)Estas ecuaciones son recomendables para valores <strong>de</strong> DNen el intervalo <strong>de</strong> 12 a 106 cm y son confiables para usarse encondiciones similares, en cuanto al grado <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación.These equations are advisable for DN values between 12 and106 cm and are reliable to be used un<strong>de</strong>r similar conditions, interms of <strong>de</strong>cline.The <strong>de</strong>termination coefficients for the biomass estimationmo<strong>de</strong>ls were 0.928 for the stem, 0.6176 for branch wood and0.588 for foliage. Even if the R 2 values reported by severalauthors are higher, it would have been good to get highernumbers in this study; however, the high mortality levels at stem,branch and foliage level caused by <strong>de</strong>cline in the area are thereasons why better results were not accomplished, specially inbranch and foliage (figures 5 and 6).In a Pinus patula study, Díaz (2007) reported R 2 values of0.9828 for stem biomass with a normal diameter interval from6.7 to 64.1 cm. This number in higher than that found for A.religiosa; however, the range of sizes of the stem consi<strong>de</strong>redin this study might have helped to reduce the R 2 value in theresearch.For total A. religiosa trees, Avendaño et al. (2009) foundR 2 = 0.99. Geron and Ruark (1988) estimated an R 2 of 0.62 forPinus radiata D. Don needle biomass. Navar et al. (2001) cite0.83 for R 2 of stem biomass, 0.66 for branch wood biomassand 0.38 for needle biomass of Pinus durangensis Ehren. andPinus cooperi Blanco. The <strong>de</strong>termination coefficients of thesestudies for the branch wood and needle biomass are low, ingeneral, and are coinci<strong>de</strong>ntal to those here documented. In thecase of pines, the low <strong>de</strong>termination coefficients for biomassmo<strong>de</strong>ls of branch wood and foliage can respond to the mortalityof branches causes by self-pruning, from the intolerantfeature of this taxonomic group; in regard to A. religiosa, atotally shadow-tolerant species, the scarce self-pruning doesnot explain the low <strong>de</strong>termination coefficients. Thus, it is onlyattributable to branch mortality, as a result of <strong>de</strong>cline to whichthis specie is subject in this study area and in other places of isnatural distribution area (Alvarado-Rosales et al. 2002, López1997, Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-et al. 2001).Los coeficientes <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminación para los mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong>estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa a nivel árbol fueron 0.928, 0.6176 y0.588 para fuste, ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y follaje, respectivamente.Aunque los valores <strong>de</strong> R 2 son superiores a los registrados poralgunos otros autores, hubiera sido <strong>de</strong>seable lograr valoresmás altos; sin embargo, los altos niveles <strong>de</strong> mortalidad a nivelfuste, ramas y follaje, estos a su vez causados por el proceso<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación en la zona, posiblemente originaron estosresultados, especialmente en los casos <strong>de</strong> ramas y follaje(figuras 5 y 6).Díaz (2007) en un estudio con Pinus patula consigna valores<strong>de</strong> R 2 = 0.9828 para biomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste cuyo diámetro normalFigura 4. Mo<strong>de</strong>lo para la estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> fustes <strong>de</strong>Abies religiosa.Figure 4. Biomass estimation mo<strong>de</strong>l for Abies religiosa stems.17

Rev. Mex. Cien. For. <strong>Vol</strong>. 2 Núm. 8varió en un intervalo <strong>de</strong> 6.7 a 64.1 cm. Esta cifra es mayor ala <strong>de</strong>terminada para A. religiosa; sin embargo, el intervalo <strong>de</strong>dimensiones <strong>de</strong> fuste cubierto en dicho estudio quizá tambiéncontribuyó a disminuir el valor <strong>de</strong> R 2 .Biomass distribution in the treeFigure 7 shows the biomass distribution of the aerial partsof the tree. In the stem is the greatest part of biomass (97%),while in branches is only stored 3% of biomass and 0.07% infoliage. This biomass distribution pattern is atypical of theshadow-tolerant species like A. religiosa. In fact, as these speciesare tolerant to shadow even in the lower branches, it is expectedthat they keep a larger proportion of biomass in these organs,compared to intolerant species.Figura 5. Mo<strong>de</strong>lo para la estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra<strong>de</strong>l conjunto <strong>de</strong> ramas <strong>de</strong> árboles <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa.Figure 5. Biomass estimation mo<strong>de</strong>l for Abies religiosa wood ofthe group of branches.Para árboles completos <strong>de</strong> A. religiosa, Avendaño et al.(2009) obtuvieron una R 2 = 0.99. Geron y Ruark (1988)estimaron una R 2 <strong>de</strong> 0.62 para biomasa <strong>de</strong> acículas en Pinusradiata D. Don. Navar et al. (2001), citan una R 2 <strong>de</strong> 0.83 parabiomasa <strong>de</strong> fuste, 0.66 para biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramasy 0.38 para biomasa <strong>de</strong> acículas <strong>de</strong> Pinus durangensis Ehren. yPinus cooperi Blanco. Los coeficientes <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminaciónencontrados en estos estudios para los casos <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong>ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y acículas son bajos, en general, coinci<strong>de</strong>ncon los aquí documentados. Para el caso <strong>de</strong> los pinos,los bajos coeficientes <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminación para mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong>biomasa <strong>de</strong> ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas y follaje pue<strong>de</strong>n respon<strong>de</strong>r ala mortalidad <strong>de</strong> ramas ocasionada por la autopoda, dado alcarácter intolerante <strong>de</strong> este grupo taxonómico; en el caso <strong>de</strong> A.religiosa, especie tolerante a la sombra, la reducida autopodano explica los bajos coeficientes <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminación. Por lo tantosolo es atribuible a la mortalidad <strong>de</strong> ramas, que resulta <strong>de</strong>lfenómeno <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación, al que actualmente está sujeta estaespecie en la zona <strong>de</strong> estudio y en otros sitios <strong>de</strong>l área <strong>de</strong>su distribución natural (Alvarado-Rosales y Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-Tejeda,2002; López, 1997; Hernán<strong>de</strong>z et al., 2001).Figura 6. Mo<strong>de</strong>lo para la estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> acículas<strong>de</strong> árboles <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa.Figure 6. Biomass estimation mo<strong>de</strong>l for Abies religiosa needles.Navar et al. (2001) estimated that the stem of Pinusdurangensis gathers 64 % and that of Pinus cooperi 67% ofthe total biomass of the tree, branch wood 22.5 and 22.4 %,and foliage 13.5 y 10.6%, respectively. In both species, biomassdistribution is even more extreme, compared to that obtainedfor A. religiosa.Distribución <strong>de</strong> biomasa en el árbolLa Figura 7 muestra la distribución <strong>de</strong> la biomasa en loscomponentes aéreos <strong>de</strong>l árbol. En el fuste está la mayorparte <strong>de</strong> la biomasa (97%), mientras que en las ramas solo seacumula 3% <strong>de</strong> la biomasa y en el follaje 0.07%. Este patrón<strong>de</strong> distribución <strong>de</strong> biomasa es atípico <strong>de</strong> especies tolerantesa la sombra como lo es A. religiosa. En efecto, estas especies, porsu tolerancia a la sombra, conservan, incluso ramas bajas, aúnen condiciones <strong>de</strong> sombra, por lo que la expectativa es queFigura 7. Distribución <strong>de</strong> biomasa en árboles <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa<strong>de</strong>l Cerro Tláloc, Texcoco, Edo. <strong>de</strong> México.Figure 7. Distribution of biomass of Abies religiosa trees ofTlaloc Hill, Texcoco, Edo. <strong>de</strong> México.18

Flores-Nieves et al., Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación y distribución...tengan una proporción más gran<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> biomasa en estosórganos, en comparación con las especies intolerantes.Para Pinus durangensis y Pinus cooperi, Navar et al. (2001)estimaron que el fuste contiene 64 y 67% <strong>de</strong> la biomasa total<strong>de</strong>l árbol, la ma<strong>de</strong>ra <strong>de</strong> ramas 22.5 y 22.4 % y el follaje 13.5y 10.6%, respectivamente. En ambas especies, la distribución<strong>de</strong> biomasa es todavía más extrema, comparada con la que seobtuvo para A. religiosa.No obstante, son congruentes con la apariencia actual<strong>de</strong>l arbolado en el área <strong>de</strong> estudio. Avendaño et al. (2009),mencionan que en los árboles <strong>de</strong> oyamel 81.3 % <strong>de</strong> la biomasase acumula en los fustes, 6.9% en ramas y 8.6 % en follaje.El valor <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> ramas es similar al <strong>de</strong>terminado enel presente estudio, pero la proporción <strong>de</strong> biomasa foliar esclaramente menor. La diferencia en el patrón <strong>de</strong> distribución <strong>de</strong>biomasa, probablemente, resulta <strong>de</strong>l efecto <strong>de</strong>l fenómeno<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación.CONCLUSIONESLos mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong>sarrollados en el presente estudio son aplicablesa los árboles <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa en proceso <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación.La estructura <strong>de</strong> copa <strong>de</strong> los árboles <strong>de</strong> A. religiosa en dichacondición en el área <strong>de</strong> interés muestra señales <strong>de</strong> alteración.Esto aumenta la variabilidad <strong>de</strong> la biomasa <strong>de</strong> copas y dificultasu mo<strong>de</strong>lación.El patrón <strong>de</strong> distribución <strong>de</strong> biomasa en los componentesaéreos <strong>de</strong> árboles <strong>de</strong> A. religiosa en el área <strong>de</strong> estudioes atípico, en comparación con individuos sin <strong>de</strong>clinación, enrespuesta a la alta mortalidad <strong>de</strong> follaje y ramas.AGRADECIMIENTOSAl CONACYT por la beca otorgada al primer autor para sus estudios <strong>de</strong>Maestría en Ciencias y por el financiamiento a través <strong>de</strong>l proyecto 61559,2006. A la Línea Prioritaria <strong>de</strong> Investigación 8 (LPI-8) <strong>de</strong>l Colegio <strong>de</strong>Postgraduados, por el financiamiento parcial al estudio.REFERENCIASAcosta M., M., J. J. Vargas H., A. Velázquez M. y J. Etchevers B. 2002. Estimación<strong>de</strong> la biomasa aérea mediante el uso <strong>de</strong> relaciones alométricasen seis especies arbóreas en Oaxaca, México. Agrociencia. 36:725-736.Alvarado R., D., L. I. De Bauer and A. J. Galindo. 1993. Decline of sacred fir(Abies religiosa) in a forest park south of Mexico City. Environ. Pollut.80: 115–121.Alvarado-Rosales, D. and T. Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-Tejeda. 2002. Decline of Sacred-firin the Desierto <strong>de</strong> los Leones <strong>Nacional</strong> Park. In: Fenn, M. E., L. I.<strong>de</strong> Bauer, T. Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-T. (Eds.) Urban air pollution and forests.Resources at risk in the Mexico City air basin. Springer. NewYork, NY. USA. pp. 243-260.Avendaño H., D., M. Acosta M., F. Carrillo A. y J. Etchevers B. 2009. Estimación<strong>de</strong> biomasa y carbono en un bosque <strong>de</strong> Abies religiosa. FitotecniaMexicana. 32 (3): 233-238.Castellanos F., J., A. Velázquez M., J. J. Vargas H., C. Rodríguez F. y A. M. FierrosG. 1996. Producción <strong>de</strong> biomasa en un rodal <strong>de</strong> Pinus patula Schl.et Cham. Agrociencia. 30: 123-128.19Nevertheless, they are consistent with the present look of thetrees in the study area. Avendaño et al. (2009) reported thatin firs, 81.3 % of biomass is stored in the stem, 6.9% in branchesand 8.6% in foliage. The branch biomass value is similar to that<strong>de</strong>termined in the actual study, but the foliar biomass is clearlylower. The difference in the biomass distribution pattern, isprobably, the result of the effect of <strong>de</strong>cline.CONCLUSIONSThe mo<strong>de</strong>ls here presented are applicable to Abies religiosa in<strong>de</strong>cline. The crown structure of the trees in the study area bearsigns of distortion. This increases the variability of the biomass ofcrowns and makes mo<strong>de</strong>ling, difficult.The biomass distribution pattern of the aerial parts ofA. religiosa trees in the study area is atypical, compared toindividuals without <strong>de</strong>cline, as a reaction to the highmortality o foliage and branches.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTo CONACYT for the scholarship granted to the first author for his Master inScience studies and for the financial support provi<strong>de</strong>d to the 61559, 2006project. To the Priority Research Line No. 8 (LPI-8) of the Graduate StudiesSchool for having partially sponsored this studyEnd of the English versionCiesla, W. M. 1989. Aerial photos for assessment on forest <strong>de</strong>cline. Amultinational overview. Journal of Forestry. 87 (2): 37-41.Díaz F., R., M. Acosta M., F. Carrillo A., E. Buendía R., E. Flores A. y J. EtcheversD. 2007. Determinación <strong>de</strong> ecuaciones alométricas para estimarbiomasa y carbono en Pinus Patula Schl. et. Cham. Ma<strong>de</strong>ra yBosques 13(1): 25-34.Escandón C., J., J. B. H. J. <strong>de</strong> Jong., S. Ochoa O., I. March M. y M. A. Castillo.1999. Evaluación <strong>de</strong> dos métodos para la estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasaarbórea a través <strong>de</strong> datos LANDSAT TM en Jusnajab La Laguna,Chiapas, México: estudio <strong>de</strong> caso. Boletín <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Instituto</strong> <strong>de</strong>Geografia Núm.40: 71-84.Garcidueñas M., A. R. 1987. Producción <strong>de</strong> biomasa y acumulación <strong>de</strong>nutrientes en un rodal <strong>de</strong> Pinus montezumae Lamb. Tesis <strong>de</strong> Maestríaen Ciencias. Colegio <strong>de</strong> Postgraduados. Texcoco, Edo. <strong>de</strong> México.México. 243 p.Geron C., D. and G. Ruark A. 1988. Comparison of constant and variableallometric ratios for predicting foliar biomass of various trees ingeneral. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research. 18(10):1298-1304.Garzuglia, M. and M. Saket. 2003. Wood volume and woody biomass: reviewof FRA 2000 estimates. Forest Resources Assessment WP 68. Foodand Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome. Italy.30 p.Granados S., D. y G. F. López R. 2001. Declinación forestal. Revista Chapingo.Ciencias <strong>Forestales</strong> y <strong>de</strong>l Ambiente 7(1): 5-13.Hernán<strong>de</strong>z T., T., R. M. Cox, J. Malcolm, M. L. <strong>de</strong> la Isla B, J. Vargas H., A.Velázquez M. y D. Alvarado R. 2001 Impacto <strong>de</strong>l ozono sobreel polen <strong>de</strong> Pinus hartwegii Lindl. Rev. Cien. For. en Mex. 26: 5-18.Herrera A., M. A., I. <strong>de</strong>l Valle J. y O. Alonso S. 2001. Biomasa <strong>de</strong> la vegetaciónherbácea y leñosa pequeña y necromasa en bosques tropicalesprimarios y secundarios <strong>de</strong> colombia. In: Memorias <strong>de</strong>lSimposio Internacional Medición y Monitoreo <strong>de</strong> la Captura <strong>de</strong>Carbono en Ecosistemas <strong>Forestales</strong>. Valdivia, Chile.18 p.

Rev. Mex. Cien. For. <strong>Vol</strong>. 2 Núm. 8López L., M. A. 1997. Efectos <strong>de</strong>l ambiente aéreo y <strong>de</strong>l suelo sobre el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo<strong>de</strong> síntomas <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>clinación <strong>de</strong> oyamel. Terra 15: 287-293.López-L., M. A., R. Reich M., C. Aguirre-Bravo. and A. Velázquez M. 2009. Pinegrowth and nutrient status as related to pine/al<strong>de</strong>r ratio in mixedstands. Journal of Biological Sciences. 9(7): 637-647.López-López M.. A., A. Velázquez M., J. Acosta M. y E. Estañol B. 2006. Biomassdistribution in <strong>de</strong>clining sacred-fir seedlings. Interciencia 31(6): 451-455.López R., C. y R. Keyes. 1987. Mo<strong>de</strong>los para estimación <strong>de</strong> biomasa <strong>de</strong> Pinuscembroi<strong>de</strong>s Zucc. In: Memorias <strong>de</strong>l II Simposio <strong>Nacional</strong> sobrePinos Piñoneros. México, D. F. México. pp: 211-220.Manzano M., D., M. A. López L., F. Manzano M. y E. Pineda H. 2007.Productividad primaria neta <strong>de</strong> una plantación <strong>de</strong> recuperación<strong>de</strong> suelos. In: Memorias <strong>de</strong>l VIII Congreso Mexicano <strong>de</strong> Recursos<strong>Forestales</strong>. Morelia, Mich., México. 11 p.Mooser, F. 1975. Historia geológica <strong>de</strong> la Cuenca <strong>de</strong> México. In: Departamento<strong>de</strong>l Distrito Fe<strong>de</strong>ral (Eds). Memorias <strong>de</strong> las obras <strong>de</strong>l sistema <strong>de</strong>ldrenaje profundo <strong>de</strong>l Distrito Fe<strong>de</strong>ral. Tomo 1. Talleres Gráficos <strong>de</strong>la Nación. México, D. F. México. pp. 7-38.Navar , J., N. González. y J. Graciano. 2001. Ecuaciones para estimar componentes<strong>de</strong> biomasa en plantaciones forestales <strong>de</strong> Durango. México. In:Memorias <strong>de</strong>l Simposio Internacional Medición y Monitoreo <strong>de</strong>la Captura <strong>de</strong> Carbono en Ecosistemas <strong>Forestales</strong>. Valdivia,Chile. pp. 1– 12.Ortíz S., C. y H. Cuanalo <strong>de</strong> la Cerda. 1977. Levantamiento fisiográfico <strong>de</strong>l área <strong>de</strong>influencia <strong>de</strong> Chapingo. Colegio <strong>de</strong> Postgraduados. Escuela <strong>Nacional</strong><strong>de</strong> Agricultura, Chapingo, Edo. <strong>de</strong> Méx., México. 83 p.Palma T., A. 1996. Tipología <strong>de</strong>l uso forestal <strong>de</strong> la tierra <strong>de</strong> la región norte <strong>de</strong> laSierra Nevada y su cartografía. Tesis <strong>de</strong> Maestría. Colegio <strong>de</strong>Postgraduados. Montecillo. Edo. <strong>de</strong> México. México. 103 p.Rojo M., G. E., J. Jasso M., J. J. Vargas H., D. J. Palma L. y A. Velázquez M.2005. Biomasa aérea en plantaciones comerciales <strong>de</strong> hule(Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) en el estado <strong>de</strong> Oaxaca, México.Agrociencia 39: 449-456.Vázquez S., L., J. Tamarit C. y J. Quintanar O. 2004. Caracterización <strong>de</strong> la<strong>de</strong>clinación <strong>de</strong> bosques <strong>de</strong> encino en “Sierra <strong>de</strong> los Lobos”Guanajuato, México. Polibotánica. 17: 1-14.Vidal, A., J. Benítez Y., J. Rodríguez., R. Carlos. y H. Gra. 2004. Estimación <strong>de</strong>la biomasa <strong>de</strong> copa para árboles en pie <strong>de</strong> Pinus caribaea varcaribaea en la E.F.I. La Palma <strong>de</strong> la provincia <strong>de</strong> Pinar <strong>de</strong>l Río,Cuba. Quebracho. Revista <strong>de</strong> Ciencias <strong>Forestales</strong> (11): 60-66.Waring E., H. and W. H. Schlesinger. 1985. Forest ecosystems. Aca<strong>de</strong>mic Press.Orlando, FL. USA. 340 p.20

CARACTERÍSTICAS MORFOLÓGICAS DE PLÁNTULAS DE DOS ESPECIESFORESTALES TROPICALES PROPAGADAS EN CONTENEDORES BIODEGRADABLESY CHAROLAS STYROBLOCKMORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF SEEDLINGS OF TWO TROPICAL FOREST SPECIESPROPAGATED IN BIODEGRADABLE CONTAINERS AND STYROBLOCK TRAYSRESUMENH. Jesús Muñoz Flores 1 , J. Jesús García Magaña 1 , Víctor Manuel Coria Ávalos 1 ,Gabriela Orozco Gutiérrez 1 y Yadira Yolanda Muñoz Vega 2La función <strong>de</strong> los envases utilizados en la propagación <strong>de</strong> especies forestales es contener el sustrato que abastece a las raíces <strong>de</strong> agua,aire, nutrimentos minerales y provee <strong>de</strong> soporte físico a la planta durante su permanencia en el vivero. El objetivo <strong>de</strong> este trabajo fueevaluar la factibilidad técnica <strong>de</strong> utilizar contenedores bio<strong>de</strong>gradables (<strong>de</strong> fibra <strong>de</strong> coco), en comparación con charolas Styroblock <strong>de</strong> 60y 77 cavida<strong>de</strong>s para la producción <strong>de</strong> Enterolobium cyclocarpum y Tabebuia rosea. Se aplicó un diseño completamente al azar, con seistratamientos y cuatro repeticiones. A los tres meses <strong>de</strong> estancia en vivero, los individuos <strong>de</strong> E. cyclocarpum en los contenedores <strong>de</strong> fibra<strong>de</strong> coco lograron una altura <strong>de</strong> 24.8 cm, que fue significativamente superior (Pr > F= F= F = F =