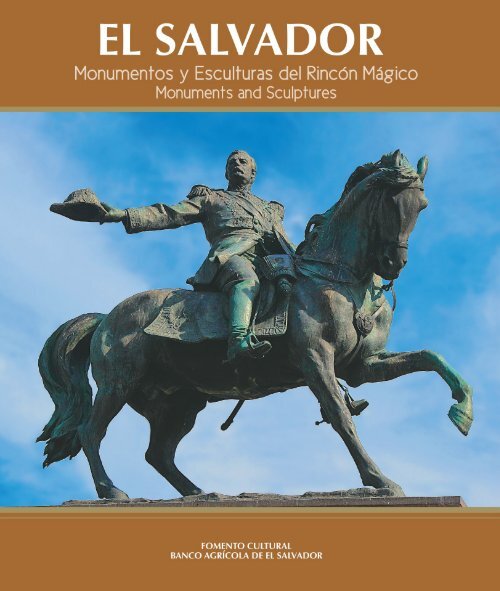

Monumentos y Esculturas

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Sergio Restrepo<br />

Presidente Junta Directiva<br />

President Board of Directors<br />

Rafael Barraza<br />

Presidente Ejecutivo<br />

Executive President<br />

Coordinador general - General coordination<br />

Cecilia Gallardo<br />

Joaquín Rivas<br />

Escritora - Investigación histórica<br />

Writer - History research<br />

Elena Salamanca<br />

Coordinación editorial - Editorial coordination<br />

Lissette de Schilling<br />

Fotografía - Photography<br />

Federico Trujillo<br />

Asistente de fotografía - Photography asistant<br />

Nelson Crisóstomo<br />

Diseño gráfico, diagramación<br />

Graphic design, layout<br />

Georgina Cubías<br />

Traducción - Translation<br />

Elsa Cea de Flores<br />

Supervisión de producción digital y proceso de impresión<br />

Digital production and printing process supervisión<br />

Lissette de Schilling<br />

Producción digital final<br />

Final digital production<br />

Visión Corporativa<br />

El Banco Agrícola agradece el valioso apoyo de las siguientes personas,<br />

instituciones, empresas y organizaciones que contribuyeron a esta edición:<br />

Joaquín Aguilar, Antonio Mena, Arturo Mc Entee Bustamante, Nick Mahomar,<br />

María Ester Méndez de Anargyros, Claude Cohen y Federico Paredes,<br />

especialista en Cabezas de jaguar.<br />

Secretaría de Cultura de la Presidencia<br />

Ana Magdalena Granadino, Secretaria de Cultura.<br />

Roberto Góchez, Director del Museo Nacional de Antropología.<br />

Museo de Arte<br />

Roberto Galicia, Director Ejecutivo.<br />

Marcela Ávalos de Cerna, Directora de Registro y Documentación.<br />

Violeta Renderos, Directora de Programas Educativos y Biblioteca.<br />

Museo de Arte Popular<br />

Madeleine Imberton, Directora.<br />

Marizta Reyes, Coordinadora de Catálogo y Atención al Público.<br />

Teatro de Santa Ana<br />

Marta Sayes, Directora.<br />

Alcaldía de San Salvador<br />

Héctor Ismael Sermeño, Departamento de Recuperación del Centro Histórico.<br />

Hotel Crown Plaza San Salvador, Mapfre La Centroaméricana, El Salvador.<br />

730.9<br />

E49<br />

sv<br />

El Salvador: monumentos y esculturas del rincón mágico = Monuments and<br />

sculptures / cordinación editorial Lissette de Schilling; investigación histórica<br />

y texto Elena Salamanca; diseño gráfico Georgina Cubías; coordinación general<br />

Cecilia Gallardo, Joaquín Rivas; traducción Elsa Cea de Flores; fotos Federico<br />

Trujillo, Nelson Crisóstomo. -- 1 a ed. -- San Salvador, El Salv.: Banco Agrícola,<br />

2013.<br />

156 p.: il., col.; 34x29<br />

Texto inglés-español<br />

El Salvador : monumentos y esculturas... 2013<br />

Impresión - Printing<br />

Artes Gráficas Publicitarias S. A. de C. V.<br />

Empastado - Binding<br />

Librería y Papelería La Ibérica S. A. de C. V.<br />

BINA/jmh<br />

ISBN 978-99923-879-8-6 ( tapa dura )<br />

1. Escultura-El Salvador--Historia. 2. <strong>Monumentos</strong>-El Salvador. I. Schilling,<br />

Lissette, cordinación editorial. II. Salamanca, Elena, investigación histórica y<br />

texto. III. Título.<br />

© 2013. Banco Agrícola. Derechos Reservados.<br />

Queda prohibida, como lo establece la ley, la reproducción parcial o total de este<br />

libro sin previo permiso por escrito del editor, con excepción de breves fragmentos<br />

que pueden usarse en reseñas en los distintos medios de comunicación, siempre<br />

que se cite la fuente.<br />

Tan cerca y tan lejos,<br />

Negra Álvarez.<br />

2 3

CONTENIDO<br />

content<br />

Presentación<br />

Foreword<br />

7<br />

Nación de Mármol y Bronce<br />

Nation of Marble and Bronze<br />

77<br />

Introducción<br />

Introduction<br />

10<br />

Imaginarios Populares<br />

Popular Imaginaries<br />

109<br />

Huella ancestral<br />

Ancestral Legacy<br />

17<br />

Universos Personales<br />

Universe of Artists<br />

121<br />

Así en la tierra como en el cielo<br />

Heaven in our Souls<br />

39<br />

Bibliografía<br />

Bibliography<br />

154<br />

4 5

PRESENTACIÓN<br />

FOREWORD<br />

La escultura es una de las tradiciones más jóvenes en el arte<br />

salvadoreño. Es por ello que el Programa de Fomento Cultural de<br />

Banco Agrícola hace un esfuerzo por rescatar y reconocer este arte,<br />

y entrega a la sociedad salvadoreña “<strong>Esculturas</strong> y monumentos del<br />

Rincón Mágico”, libro que ofrece un recorrido visual e histórico, por<br />

las obras de arte que han configurado el rumbo de la escultura en<br />

El Salvador.<br />

En esta nueva edición, se recogen los periodos de la evolución<br />

escultórica nacional, desde los primeros pobladores de Mesoamérica,<br />

hasta los impetuosos y comprometidos artistas contemporáneos.<br />

Presentamos a la escultura en sus dimensiones: espiritual, estética,<br />

humana, política, espacial e histórica. Podremos apreciar obras y<br />

artistas de relevancia histórica de gran altura estética, que han<br />

realizado un aporte a su entorno, tanto en sus temáticas como en la<br />

innovación de materiales.<br />

A pesar de las adversidades formativas que enfrentan los escultores<br />

en El Salvador, muchos de ellos se han convertido en incansables<br />

luchadores de la forja, el modelado y la talla, en arduos transformadores<br />

de la identidad de su generación y de su tiempo. La piedra, el bronce,<br />

la madera, el hierro y el barro se transforman en sus manos en una<br />

herencia inigualable.<br />

Una vez más Banco Agrícola se asoma a la historia del arte de<br />

El Salvador y se enorgullece de presentar esta nueva edición que<br />

contribuye al acervo cultural de la nación.<br />

Sculpturing is one of the youngest traditions in Salvadorean Art. It<br />

is for this reason that the Cultural Promotion Program of Banco<br />

Agrícola, makes an effort to rescue and recognize this art. It delivers<br />

to the Salvadorean Society “Sculptures and Monuments of the Rincón<br />

Mágico”, a book that offers a visual and historical tour through out<br />

the work of art that has configured the course of the sculpture in<br />

El Salvador.<br />

This new edition, lists the periods of the national sculpture evolution,<br />

since the first settlers of Mesoamérica, up to the impetuous and<br />

committed contemporary artists.<br />

We present the sculpture in its dimensions: spiritual, aesthetic, human,<br />

political, spatial, and historical. We can appreciate the work throughout<br />

history of our artists, taking in count the relevance of great aesthetic<br />

heights, who have contributed to their environment, both in its themes<br />

and innovation.<br />

Despite the adversities faced by the sculptors in El Salvador, many of<br />

them have turned into tireless fighters of the forging, modeling, and<br />

carving, in arduous transformers of the identity of their generation and<br />

their time. The stone, bronze, wood, iron, and clay are transformed in<br />

their hands in a unique heritage.<br />

Once again Banco Agrícola looks at the history of art of El Salvador<br />

and is proud to present this new edition that contributes to the cultural<br />

heritage of the nation.<br />

Rafael Barraza<br />

Presidente Ejecutivo / Executive President<br />

La Ofrenda.<br />

Leonidas Ostorga.<br />

6 7

8 9<br />

Caballos,<br />

Guillermo Perdomo.<br />

Piedra reconstruida/<br />

Reconstructive Stone<br />

33x18x5 cms.

INTRODUCCIÓN<br />

La comprensión de cómo nos relacionamos con la tercera dimensión<br />

está presente en nuestra vida cotidiana: desde las obras de arte que<br />

contemplamos en el espacio público hasta las maravillosas figuras que<br />

salen de las manos de nuestros artesanos.<br />

El Salvador está vivo, es un país que crea sus propias dinámicas; en ella<br />

están como tesoros conservados por la voluntad de vivir sus edificios<br />

de esplendor, sus recuerdos y sus monumentos.<br />

La escultura monumental constituye los inicios de la identidad nacional,<br />

con una imagen clásica, grecolatina, pues entre el siglo XIX e inicios<br />

del XX no hay un lenguaje propio ni rasgos identitarios definidos de<br />

salvadoreñidad. En esta época predomina lo épico sobre lo religioso<br />

colonial; y hace alusión a historias con representaciones míticas de la<br />

cultura grecolatina, como la Victoria, la Minerva, la República, Apolo y<br />

sus musas, entre otras, que incluso permean en la creación de Pascasio<br />

González, escultor de finales del siglo XIX e inicios del XX.<br />

obedecerá a las inquietudes e investigaciones de los artistas. Entre<br />

ellos destacan José Mejía Vides, Salarrué, Violeta Bonilla, Benjamín<br />

Saúl, Enrique Salaverría, Rubén Martínez, Titi Escalante y la apertura<br />

de técnicas y nuevos lenguajes como los de Verónica Vides, Patricia<br />

Salaverría, Guillermo Perdomo, entre otros artistas de finales del siglo XX<br />

y principios del XXI.<br />

El desarrollo de la escultura en El Salvador, ha sido, sin embargo, lento.<br />

Durante el siglo XX ha quedado demostrado que la búsqueda por una<br />

tradición escultórica nacional depende de muchas aristas: económicas,<br />

formativas, sociales y culturales.<br />

A pesar del ímpetu de sus artistas, nuestra escultura no se caracteriza<br />

por una extensa tradición. A diferencia de otras artes, como la literatura<br />

y pintura, la escultura ha tenido escenarios menos favorables, y su<br />

nacimiento, desarrollo y actual apogeo han sido marcados con fuerza<br />

y estoicismo por nuestros artistas.<br />

en El Salvador, y con temple y fuerza vocacional han triunfado y<br />

desarrollado riquísimas y fundacionales obras de arte.<br />

La escultura es uno de los vehículos para conocer y entender nuestra<br />

identidad. A través de ella y durante siglos, los ciudadanos han<br />

conocido su historia y la de sus pueblos. Son las obras de arte las que<br />

perdurarán sobre nosotros, pues el material sobre el que se realiza la<br />

escultura es, por lo general, imperecedero.<br />

La huella de la historia de la escultura de El Salvador será, finalmente,<br />

una escultura. Morirán los hombres, pero no morirán sus estatuas. Y las<br />

estatuas son su memoria.<br />

Paralela a la difusión de monumentos, en los cementerios ilustrados, los<br />

nichos mortuorios y los mausoleos perpetúan una idea del fallecido,<br />

un recuerdo imperecedero, porque el mármol y el bronce sobreviven<br />

a la carne.<br />

Hasta la década de 1920, irrumpe Valentín Estrada con su creación<br />

inicialmente ficticia del indio Atlacatl y con un posterior estudio de<br />

la cultura nahua en la década de 1950, que lo lleva a crear su propio<br />

lenguaje escultórico y trabajar con los mitos propios de la identidad<br />

Nahua-pipil, que ahora podemos ver en espacios públicos de nuestro<br />

país. Estas esculturas cumplen a cabalidad el elemento más importante<br />

de la creación artística: la identificación de la gente. Con estos mitos y<br />

su aparición en espacios urbanos y naturales las esculturas consiguen la<br />

afinidad, el interés y hasta el amor de los ciudadanos.<br />

A partir de Estrada, reconocido como el primer escultor salvadoreño,<br />

se abre una etapa de escultura de autor donde la obra, íntima o pública,<br />

Precisamente, la adversa coyuntura en la que nuestros escultores han<br />

realizado su obra permite admirar el valor de su trabajo.<br />

La falta de formación académica en las artes y de especialización<br />

en las disciplinas, ha sido durante años, la mayor dificultad. En 1811,<br />

cuando se funda la primera escuela de dibujo en San Salvador, no está<br />

contemplada la enseñanza de la escultura. Los imagineros sacros que<br />

poblaron con su arte las iglesias y casas del país durante la Colonia<br />

eran, en su mayoría, de origen guatemalteco. Cien años después, en<br />

1911, el pintor Carlos Alberto Imery funda la Escuela de Artes Aplicadas<br />

en San Salvador; esto permite a los salvadoreños realizar pequeños<br />

y perecederos ejercicios escultóricos. Hasta la década de 1960 es<br />

que, finalmente, se profesionaliza la enseñanza de la escultura con la<br />

fundación de la Dirección Nacional de Bellas Artes y la llegada del<br />

maestro español Benjamín Saúl; esta escuela desparece en la década<br />

de 1980.<br />

Este panorama no ha menguado el ímpetu de nuestros artistas,<br />

que durante más de un siglo, se han batido contra la adversidad<br />

Elena Salamanca<br />

Escritora - Historiadora<br />

10<br />

José Simeón Cañas,<br />

Rubén Martínez.<br />

11

INTRODUCTION<br />

The comprehension of how we relate with nature is present in our daily<br />

life: from the work of art, we contemplate in the public space until the<br />

marvelous figures that emerge from the hands of our artisans.<br />

El Salvador is alive, is a country that creates its own dynamics; in it are<br />

as preserved treasures by the will to live, the splendor of its buildings,<br />

its memories and its monuments.<br />

The monumental sculpture constitute the beginnings of the national<br />

identity, with a Greco-Roman classic image, between the centuries XIX<br />

and beginnings of XX there is no own language nor identity features<br />

defined of salvadoranity. Predominates at this time the epic over<br />

the colonial religious; and makes reference to histories with mythic<br />

representations of the Greco-Roman culture, such as the Victoria, the<br />

Minerva, the Republica, Apolo, and its muses, among others that even<br />

permeate in the creation of Pascasio González, sculptor in late XIX<br />

century and early XX.<br />

Parallel to the diffusion of monuments, in the illustrate cemeteries, the<br />

mortuary niches and the mausoleums perpetuate an idea of deceased,<br />

an imperishable memory, because marble and bronze survive the flesh.<br />

Until the 1920´s, Valentín Estrada bounces into the history of sculpture<br />

with his initially fictitious creation of the Indian Atlacatl and with a<br />

later study of the nahua culture in 1950´s; which lead him to create his<br />

own sculptor language and to work with own myths of the Nahuapipil<br />

identity, that now we can see in public spaces in our country.<br />

These sculptures fully comply with the most important element of the<br />

artistic creation; the identity of the people. With these myths and their<br />

appearance in urban and natural spaces the sculptures find the affinity,<br />

interest, and even the love of citizens.<br />

Starting from Estrada, recognized as the first Salvadorean sculpture,<br />

it opens a stage of sculpture for the author where all it’s masterpiece,<br />

intimate or public, will obey to the inquiries and investigations of the<br />

artists. Among them stand José Mejía Vides, Salarrué, Violeta Bonilla,<br />

Benjamín Saúl, Enrique Salaverría, Rubén Martínez, and Titi Escalante;<br />

joined with the opening of techniques and new languages such as<br />

the ones from Verónica Vides, Patricia Salaverría, Guillermo Perdomo,<br />

among other artists from the late XX century.<br />

The development of the sculpture in El Salvador, has been however,<br />

slow. During the XX century it has been demonstrated that the search<br />

for a national sculptural tradition depends of many edges: economics,<br />

training, social, and cultural.<br />

Despite the impetus of its artists, our sculpture is not characterized<br />

by a large tradition. Differentiating from other arts, such as literature,<br />

and paint, sculpture has had less favorable scenarios, and its beginning,<br />

development, and current height has been marked with strength and<br />

stoicism by our artists.<br />

Definitively, eventhough adverse situations, we are allowed to admire<br />

the work of our scutures.<br />

The lack of academic training in arts and specialization in the disciplines<br />

has been for years a dificulty. In 1811, when the first school of drawing<br />

is funded in San Salvador, it does not include instruction in sculpturing.<br />

Churches and houses were covered with Sacral imagery during the<br />

Colony, were mostly from Guatemala. Hundred years afterwards, in<br />

1911, the artist Carlos Alberto Imery founded the School of drawing<br />

and painting, wich later become the Escuela Nacional de Artes Gráficas<br />

in San Salvador; this allows the Salvadoreans to perform small and<br />

perishable sculptural exercises. Until the 1960´s, finally, with the arrival<br />

of the Spanish master Benjamín Saúl, the teaching of sculpturing is<br />

professionalized with the founding of the Direction of Fine Arts and it<br />

disappeared in the 1980´s.<br />

This context has not diminish the impetus of our artists, who more<br />

than a century, have fought against adversities in El Salvador, and with<br />

resilience and vocational strength have succeeded and developed<br />

riches and foundational works of art.<br />

The sculpture is one of the vehicles to know and understand our<br />

identity. Through it and during centuries, the citizens have known<br />

their history and that of their towns. The work of art will remain<br />

over us, since the material over which the sculpture is made, is in<br />

general imperishable.<br />

The trace in the history of sculpture of El Salvador will be finally,<br />

a sculpture. Men will die, but not their statues. And the statues are<br />

their memory.<br />

Elena Salamanca<br />

Writer – Historian<br />

La Volcaneña,<br />

Titi Escalante.<br />

12 13

Este incensario del periodo posclásico muestra el rostro como<br />

depósito de lo sagrado: nariz perforada y orejas con expansiones,<br />

relacionadas a las actividades ceremoniales.<br />

This post-classic censer show the face as deposit of the sacred:<br />

pierced nose and ears with expansions, related to the ceremonial<br />

activities.<br />

14 15

Grupo de esculturas prehispánicas,<br />

Museo Nacional de Antropología Dr. David J. Guzmán.<br />

Group of prehispanic sculptures,<br />

Museo Nacional de Antropología David J. Guzmán.<br />

HUELLA ANCESTRAL<br />

Ancestral Legacy<br />

16 17

De la tierra, de arcilla y piedra, está hecha nuestra memoria.<br />

O<br />

ur memory is done from soil, clay, and stone<br />

Lo que quedó de los que estuvieron antes que nosotros, de<br />

los primeros pobladores del actual El Salvador, es huella tangible:<br />

esculturas, monumentales, ceremoniales y cotidianas cuentan lo que<br />

pasó. En qué creían los primeros hombres, cómo convivían con la<br />

naturaleza y enfermedades, cómo amaban y quiénes eran.<br />

El Salvador es habitado alrededor del año 1,200 a. C. Entre sus<br />

pobladores más destacados están los nahuapipiles, que viajaron<br />

desde el centro de México a través de la costa Pacífica. En sus<br />

ciudades erigieron esculturas monumentales, como las estelas y las<br />

cabezas de Jaguar. En sus templos, representaban a sus dioses en<br />

arcilla y piedra, tocaban flautas con formas de animales y cuerpos<br />

humanos, y representan, con toda su crudeza, la enfermedad, la salud<br />

y la fertilidad.<br />

Los estudios arqueológicos, históricos y artísticos nos permiten<br />

llamar pintura o escultura precolombina a estas manifestaciones. Lo<br />

sagrado y lo humano no se encuentran en estratos estrictamente<br />

separados, como ahora, cada momento vital tiene un profundo valor<br />

ritual y simbólico.<br />

Mucho de este trabajo escultórico tiene influencias mayenses o<br />

toltecas. La forma de las piedras, el color de la cerámica y demás<br />

elementos que encontramos en la escultura precolombina son también<br />

resultado del comercio, la migración y el contacto con otros pueblos,<br />

como los mayas instalados en la actual Honduras.<br />

La mayoría de las piezas que incluimos en este estudio y que<br />

interpretamos como esculturas, provienen del occidente y la zona<br />

central del país. Son piezas paradigmáticas del pasado nacional. Varias<br />

de ellas pertenecen a la colección del Museo Nacional de Antropología,<br />

Dr. David J. Guzmán (MUNA); como el hacha ceremonial ornitomorfa y<br />

la flauta tallada en hueso, que son parte de la Lista roja de bienes en<br />

peligro de Centroamérica y México, que las protege como patrimonio<br />

mesoamericano. También incluimos hallazgos recientes como la<br />

tradición de cabezas de jaguar, encontradas en los últimos años en la<br />

zona occidental del país,<br />

What remains from the ones who were before us, from the<br />

first settlers of the current El Salvador, is a tangible trace. Monumental,<br />

ceremonial, and everyday sculptures, tell what happened, what the<br />

first men believed in, how they co-existed with nature and diseases,<br />

how they loved and who they were.<br />

El Salvador is inhabited around 1,200 BC. Between its most prominent<br />

population are the nahuapipiles, who traveled from the center of México<br />

through the Pacific Coast. In its cities erected monumental sculptures,<br />

as the wakes and heads of Jaguar. In its temples, represented their<br />

gods in clay and stone, playing flutes in shapes of animals and human<br />

bodies, and represented, with all its rawness, sickness, health, and<br />

fertility.<br />

The arqueological, historic, and artistic studies allow us to call a paint<br />

or sculpture pre-Columbian to these manifestations. The sacred and<br />

the human are not found in stratus strictly separated, as of now, each<br />

vital moment has a profound ritual and symbolic value.<br />

Much of this sculptural work has Mayans or Totelcs influences. The<br />

shape of the stones, the color of the clay and other elements we<br />

found in the pre-Colombian sculpture are also the result of the<br />

commerce, migration, and contact with other towns; as the Mayans<br />

installed in the current Honduras.<br />

The majority of the pieces we includ in this study and we interpret<br />

such as sculptures, come from the west and the central zone of<br />

the country. These are paradigmatic pieces from our national past.<br />

Many of them belong to the collection of the Museo Nacional de<br />

Antropología, Dr. David J. Guzmán (MUNA); such as the ceremonial<br />

ornitomorfa hatch and the flute carved, which are part of the Red list<br />

of goods in danger in Central America and México, which protects<br />

them as Mesoamerican heritage. We also include recent findings<br />

such as the tradition of heads of jaguar, found during the latest<br />

years in the west area of the country.<br />

Dios de la primavera Xipetotec, nuestro señor el desollado.<br />

El culto del Xipetotec se expandió en el actual El Salvador<br />

en el periodo posclásico, que va de los años 900 a 1524 d. C.<br />

Esta escultura fue encontrada en la Laguna Seca, en Chalchuapa.<br />

Dios de la primavera Xipetotec, our lord the flayed. The cult of<br />

the Xipetotec was expanded in the current El Salvador in the post<br />

classic-period, which goes from 900 to 1524 AC. This sculpture<br />

was found in the Laguna Seca, Chalchuapa.<br />

18 19

LO SAGRADO Y LA NATURALEZA<br />

La fauna y los elementos naturales como la tierra, el fuego, viento y el<br />

agua, han sido representados en la escultura precolombina.<br />

Los animales adquieren una doble significación para los pueblos<br />

originarios: representan lo sagrado y a la vez su fuente de alimentación.<br />

En el plano sagrado, plumas, pieles, colmillos, entre otros, eran parte de la<br />

indumentaria para enfrentarse a la vida o la guerra y honrar a sus dioses.<br />

Muchos animales como los monos, jaguares y ciertas aves tenían valor<br />

sagrado, personificando dioses; con esto, los pueblos de Mesoamérica<br />

coinciden con la cultura griega, la cual tenía una corte de dioses que<br />

adoptaban apariencias zoomorfas o se representaban en forma alegórica<br />

de animal.<br />

La insistente presencia de animales, radica en la creencia del “nahual”, un<br />

animal que acompañaba a los seres humanos en su tránsito por el mundo<br />

terrenal.<br />

THE SACRED AND THE NATURE<br />

Wildlife and natural elements such as earth, fire, wind, and water have<br />

been represented in the pre-Colombian sculpture.<br />

The animals acquire a double significance for native towns. They<br />

represent the sacred and at the same time their source of feeding. In the<br />

sacred plane, feathers, fur, fangs, among others, were part of the clothing<br />

to face life or war and honor their gods.<br />

Many animals, such as monkeys, jaguars and certain birds had a sacred<br />

value; which would personify their gods. With this, the towns of<br />

Mesoamerica are equal with Greek culture; in which a court of gods,<br />

adopted zoomorphic looks or represented an animal in an allegoric shape.<br />

The persistent presence of animals, were a belief of the “nahual”, an<br />

animal that would accompany human beings in their passage through<br />

the underworld.<br />

Vaso Ceremonial, periodo clásico. Los cánones estéticos precolombinos no<br />

siempre han comulgado con los occidentales. En este incensario del periodo<br />

clásico observamos un rostro humano deformado: con ojos de tornado y la<br />

lengua de fuera, que puede denotar la imagen del Dios del Sol.<br />

Ceremonial Glass, classic period. The pre-Colombian aesthetic canons not<br />

always have agreed with the western. In this censers of the classic period we<br />

observ a human face distorted: with eyes turned and the tongue out, that may<br />

denote the image of the God of the Sun.<br />

20 21

Cabezas de jaguar. Estas esculturas monumentales de talla directa<br />

en piedra pertenecen a la tradición llamada Cabeza de jaguar,<br />

y fueron encontradas en 2002 en el occidente de El Salvador.<br />

Su nombre proviene de la semejanza con el animal; los 45 monumentos<br />

encontrados, hasta la fecha en el país, poseen rasgos comunes, como el<br />

hocico, dientes de gran tamaño, nariz en forma de “u” invertida y ojos<br />

arremolinados.<br />

Los monumentos de la tradición Cabeza de jaguar solían erigirse en grupos<br />

de tres, según demuestran los hallazgos localizados en Ataco, Ahuachapán<br />

y en Tapalshucut, Izalco. Este grupo monumental encontrado en Izalco<br />

estaba, además, custodiado por dos estelas. Actualmente, estas cabezas<br />

de jaguar pertenecen al acervo del Museo Nacional de Antropología.<br />

Los estudios del arqueólogo Federico Paredes, investigador de esta<br />

tradición, señalan que las esculturas monumentales eran usadas por<br />

los gobernantes como estrategias para apuntalar su poder. También<br />

se relacionaron con rituales religiosos y chamánicos. Algunas de estos<br />

monumentos podían ser usados como ofrendas funerarias en las tumbas<br />

de otros personajes importantes de la sociedad.<br />

Cabezas de Jaguar. These monumental sculptures come from direct<br />

carving in stone and belong to the tradition called Cabezas de Jaguar.<br />

These were found in 2002, at the west of El Salvador.<br />

Their name comes from the similarity with the animal. The 45 monuments<br />

found in the country up to this date have common features; such as the<br />

snout, big teeth, nose in the shape of an inverted “u” and eyes with<br />

whirled motives.<br />

The monuments of the tradition Cabezas de Jaguar used to be erected in<br />

groups of three, according to the findings located in Ataco, Ahuachapán,<br />

and Tapalshucut, Izalco. These monumental groups were also guarded by<br />

two stelas. Currently, these heads of Jaguar belong to the collection of<br />

the Museo Nacional de Antropología, where they have not been exhibited.<br />

The studies of the archeologist Federico Paredes, investigator of this<br />

tradition, point out that monumental sculpture used by the governors<br />

as a strategy to show their power. They were also related with religious<br />

and shamanic rituals. Some of these monuments could be used as funeral<br />

offerings in the tombs of other important characters of society.<br />

22 23

Hacha ceremonial con forma de cabeza de<br />

ave tallada en piedra de adesita, con intensa<br />

coloración roja.<br />

Elaborada en jade, esta placa representa<br />

un sacerdote de rodillas con máscara<br />

ceremonial en forma de ave.<br />

Ceremonial hatch in a shape of a head of<br />

bird carved in andesite stone with intense<br />

red coloring.<br />

Elaborated in jade, this plate represents<br />

a priest on his knees with a ceremonial<br />

mask in the shape of a bird.<br />

24 25

Flauta.<br />

Esta flauta ha sido tallada con detalle de una calavera.<br />

Pertenece al periodo clásico y por su valor ha sido incluida,<br />

desde el año 2010, en la Lista roja de bienes culturales en<br />

peligro de Centroamérica y México.<br />

Placa de Jade.<br />

En esta pieza se encuentra tallada un águila, animal relacionado<br />

con el sol, es decir, con las deidades. Fue esculpida en el<br />

periodo clásico y fue encontrada en Tazumal en 1944.<br />

Incensario.<br />

Representa a un hombre disfrazado de jaguar. Muchos pueblos<br />

nahuas de Mesoamérica utilizaban las pieles del jaguar en sus ritos<br />

ceremoniales y para adentrarse en los rigores de la guerra; en<br />

las batallas aztecas conocidas como “guerras floridas aztecas”,<br />

los guerreros usaban la piel de jaguar como indumentaria, tal y<br />

como ilustra con realismo este incensario del periodo clásico.<br />

Garra de jaguar.<br />

Pertenece a un conjunto escultórico que no fue encontrado<br />

integramente. Su modelado es realista e imponente. El jaguar se<br />

asociaba políticamente a la guerra y el poder.<br />

Flute.<br />

This flute has a skull carved in it, with detail. Belongs to<br />

the classic period and due to its value, it has been included<br />

since the year 2010, in the Red List of cultural goods in<br />

danger of Central America and México.<br />

Jade plaque.<br />

In this piece we found an eagle carved, animal related with<br />

the sun; meaning, with the deities. It was carved during the<br />

classic period and found in Tazumal in 1944.<br />

Censer.<br />

Represents a man disguised as jaguar. Many Nahua towns from<br />

Mesoamerica used the skin of the jaguar in their ceremonial<br />

rites to venture into the rigors of war; in Azteca battles, known<br />

as “guerras floridas aztecas”. The warriors used the skin of the<br />

jaguar as clothing, to illustrate with realism the censer of the<br />

classic period.<br />

Paw of jaguar.<br />

Belongs to a sculptural group, which was not found complete. It’s<br />

modeling is realistic and impressive. The jaguar was associated<br />

politically to war and power.<br />

26 27

El disco del jaguar.<br />

Es una de las piezas más conocidas de nuestro<br />

pasado precolombino. Proviene del periodo clásico y<br />

fue tallado en basalto. Fue encontrado en Cara Sucia,<br />

en Santa Ana, en 1892.<br />

Jaguar disk.<br />

This is one of the most famous pieces of our Pre-<br />

Colombian period. It comes from the classic period<br />

and was carved in basalt. It was found in Cara Sucia,<br />

Santa Ana, in 1892.<br />

Huehuetéotl, dios viejo del fuego,<br />

es relacionado con los origenes, el fuego y el hogar<br />

Pertenece al periodo postclásico del 900-1524 d. C.<br />

El pedernal excéntrico es una pieza única en El Salvador. Tallada en<br />

pedernal, representa a un rey ataviado en su trono. Fue encontrado en<br />

el sector La Campana, en el sitio Arqueológico San Andrés y data del<br />

periodo clásico, en el siglo VIII d. C. Hay pocos ejemplos de su tipo en<br />

el mundo mesoamericano, su uso es ceremonial.<br />

Flint Scentric. This is a unique piece in El Salvador. Carved in flint, it<br />

represents a king dressed in his throne. It was found in La Campana,<br />

at the archeological site of San Andrés and dates the classic period<br />

of the VIII century AC. There are few samples of its type in the<br />

Mesoamerican world, its used in ceremonies.<br />

Huehuetéotl, old god of fire,<br />

is related with the origins, the fire, and home.<br />

Belongs to the post classic period from 900-1524 AC.<br />

28<br />

29

Estela de Tazumal. Elaborada en piedra, es una de las piezas más<br />

antiguas estudiadas por los arqueólogos en El Salvador, su hallazgo<br />

se realizó en 1892 y actualmente se exhibe en el Museo Nacional de<br />

Antropología. Mide 2.65 por 1.15 metros y pertenece al periodo clásico.<br />

Estela de Tazumal. Elaborated in stone, it is one of the eldest pieces<br />

studied by the archeologists in El Salvador; it was found in 1892<br />

and currently is exhibited in the National Museum of Anthropology.<br />

Measures 2.65 by 1.15 meters and belongs to the classic period.<br />

Máscara de rostro humano tallada en serpentina verde.<br />

Pertenece al periodo clásico y está relacionada a los cultos funerarios.<br />

Mask of human face carved in green serpentine.<br />

Belongs to the classic period and is related to the funeral cults.<br />

30 30<br />

31

Figurilla de cerámica con cuerpo zoomorfo y rostro humano, se<br />

trata de una ocarina, un instrumento de viento modelada en el<br />

periodo posclásico y encontrada en el actual Tonacatepeque,<br />

San Salvador.<br />

Clay figure with zoomorphic body and human face, is a ocarina,<br />

an instrument of wind modeled in the post classic-period and<br />

found in Tonacatepeque, San Salvador.<br />

Las figuras animales van a preponderar en el periodo clásico, como<br />

esta vasija de cerámica que representa a un roedor comiendo.<br />

The animal figures will predominate in the classic period, such<br />

as this clay vessel that represents a rodent eating.<br />

Vasija de cerámica plomiza que representa un tacuazín;<br />

encontrada en el actual territorio de La Paz.<br />

Su cerámica oscura es parte del estilo Usulután.<br />

Modelada en el periodo preclásico, 2500 a.C. al 250 d.C.<br />

Ceramic vessel of colored lead represents a tacuazín;<br />

found in the current territory of La Paz.<br />

Its dark clay is part of the Usulután style.<br />

Modeled in the pre classic-period, 2500 B.C. to 250 A.C.<br />

32 33

Esta figurilla de cerámica es conocida popularmente como “Perrito de Cihuatán” aunque<br />

los colmillos de su rostro pueden denotar a una figura más bien felina. Procede del actual<br />

territorio de San Salvador, y se remonta al periodo posclásico, es decir fue elaborada<br />

apenas siglos antes del contacto con los españoles. Las figuras con ruedas han sido<br />

localizadas únicamente en México y El Salvador.<br />

This clay figure is known popularly as “Perrito de Cihuatán” although the fangs on its face<br />

could denote a more feline figure. Comes from the current territory of San Salvador, and<br />

dates back form the post classic period, which means it was elaborated barely centuries<br />

before the contact with the Spaniards. The figures with wheels have been located only in<br />

México and El Salvador.<br />

34 35

FERTILIDAD<br />

FERTILITY<br />

SALUD Y ENFERMEDAD<br />

HEALTH AND SICKNESS<br />

En El Salvador se han localizado figuras con forma del cuerpo femenino,<br />

la mayoría hace referencia a la maternidad: la lactancia, el embarazo y<br />

el parto.<br />

Muchas de estas figurillas que aluden a la maternidad datan del<br />

periodo preclásico; mientras que las que representan la fertilidad son<br />

del periodo clásico y son comúnmente llamadas Bolinas.<br />

Las bolinas evocan a las esculturas femeninas de la fertilidad de<br />

las tribus originarias de África, en ellas, la mujer desnuda en franca<br />

exageración de proporciones (pechos y nalgas enormes, caderas<br />

anchas y muslos gordísimos) provoca al cuerpo para demostrar su<br />

prestancia a la reproducción.<br />

In El Salvador they have located figures in the shape of a feminine<br />

body, the majority make reference to maternity: breast feeding,<br />

pregnancy and birth.<br />

Many of these figures make allusion to the maternity from the preclassic<br />

period; while the ones representing fertility, are from the<br />

classic period and are commonly called Bolinas.<br />

The Bolinas evoke the feminine sculptures of fertility from the tribes<br />

of Africa; in them, nude woman on frank exaggeration of proportions<br />

(huge breasts and buttocks, wide hips and fat thighs) provokes the<br />

body to demonstrate their poise to reproduction.<br />

La figura humana es uno de los modelos principales de la escultura<br />

precolombina: representa hechos históricos o sobrenaturales o los<br />

estados del cuerpo como la salud, la enfermedad o la vejez. Si en<br />

Occidente, el cuerpo desnudo es un enemigo y debe cubrirse, para<br />

los pobladores originales de América es más bien una extensión de<br />

lo sagrado. El cuerpo humano se representa en silbatos, estatuillas<br />

pequeñas, estelas, vasijas e incensarios.<br />

Uno de los elementos más destacados en la escultura precolombina<br />

es la representación de “lo feo”. Las concepciones estéticas de<br />

occidente están mayormente inclinadas a la belleza y se interpreta<br />

estética como “lo bonito”. En la escultura precolombina podemos ver<br />

lo desagradable, como el rastro de la enfermedad, muestra de ello<br />

son las llagas, pústulas y enfermedades como el labio leporino o la<br />

hidrocefalia.<br />

The human figure is one of the main models of the pre-Colombian<br />

sculpture. It represents historic or supernatural facts or the stages of<br />

the body such as health, sickness, or oldness. In the west, the nude<br />

body is an enemy and must be covered, but for the original settlers<br />

in America, it is rather an extension of the sacred. The human body<br />

is represented in whistles, small statues, stele, vessels, and censers.<br />

One of the most prominent elements in the pre-Colombian sculpture<br />

is the representation of “the ugly”. The aesthetic conceptions of the<br />

west are greatly inclined in the beauty and the aesthetic is interpreted<br />

as “the pretty”. In the pre-Colombian sculpture, we can see the<br />

unpleasant as the trace of the disease; sample of this are the sores,<br />

pustules and diseases such as the cleft lip or hydrocephalus.<br />

El hijo que la mujer sostiene en sus brazos le toca un seno en espera de su alimento.<br />

Esta figurilla de cerámica bicroma pertenece al periodo preclásico.<br />

Embarazo y parto se identifican en escultura bolina: Su vientre está hinchado y su<br />

vulva expuesta. Pertenece al periodo preclásico y fue encontrada en la Laguna de<br />

Cuscachapa, Chalchuapa.<br />

Silbato de cerámica que representa a un hombre con labio leporino. Pertenece al<br />

periodo clásico y fue encontrada en Cara Sucia, Ahuachapán.<br />

La hidrocefalia está representada en esta vasija de cerámica. En el periodo clásico<br />

los artistas estudiarán las representaciones físicas de la enfermedad.<br />

The son which the woman is holding in her arms touches her breast waiting to be fed. This<br />

figure of bichrome clay belongs to the pre-classic period.<br />

Pregnancy and birth are identified in Bolinas sculpture: The womb is swollen and the<br />

vulva is exposed. Belongs to the pre-classic period and was found in the Laguna de<br />

Cuscachapa, Chalchuapa.<br />

Whistle of clay, which represents a man with cleft lip. Belongs to the classic period<br />

and was found in Cara Sucia, Ahuachapán<br />

The hydrocephalus is represented in this vessel of clay. In the classic period the<br />

artists will study the physical representations of the diseased.<br />

36 37

Altar mayor de la Iglesia de la Santa Cruz de Roma, de Panchimalco.<br />

Panchimalco fue, durante la Colonia, un pueblo de Indigenas, y su iglesia, erigida en el siglo<br />

XVIII, representa el barroco religioso más difundido en las iglesias salvadoreñas. Su estilo<br />

es menos suntuoso que el guatemalteco o mexicano.<br />

El altar mayor fue tallado en madera y revestido con hoja pan de oro. La riqueza de la<br />

escultura religiosa del barroco se vio influida también por las figuras propias de la región,<br />

como las frutas o los rostros aindiados de sus ángeles. En el altar mayor de Panchimalco,<br />

en otros de sus altares y el artesonado de la iglesia, pueden distinguirse frutas como el<br />

cacao, de poderosa presencia en la económica colonial.<br />

La iglesia de Panchimalco es patrimonio cultural salvadoreño desde 1975.<br />

The main altar of the Church of Santa Cruz de Roma, in Panchimalco.<br />

Panchimalco was, during the Colony, a town of Indians, and its church, erected in XVIII<br />

century, represents the religious baroque most widespread in the Salvadorian churches.<br />

Its style is less sumptuous than the Guatemalan or Mexican.<br />

The main altar was carved in wood and coated with gold leaf sheet. The richness of the<br />

religious sculpture of the baroque was influenced also by its own religious figures, such<br />

as fruits or the Indian looking faces of its angels. In the high altar of Panchimalco, other<br />

theirs altars, and the coffered ceiling of the church, fruit can be distinguished as cocoa<br />

fruits of powerful economic presence in the colonial.<br />

The church of Panchimalco is Salvadorean cultural heritage since 1975.<br />

ASI EN LA TIERRA COMO EN EL CIELO<br />

Heaven in our Souls<br />

38 39

El Salvador del Mundo, patrono de El Salvador.<br />

Esta escultura de madera policromada es conocida<br />

como “La Imperial”, pues según la tradición popular<br />

fue donada en el siglo XVI, por el emperador Carlos V,<br />

nieto de los Reyes Católicos.<br />

El Salvador del Mundo, Patron of El Salvador.<br />

This sculpture; made of polychrome wood, is known<br />

as “La Imperial” according to the popular tradition<br />

because it was donated in the XVI century, by the<br />

emperor Carlos V, grandson of the Catholic Kings.<br />

ESCULTURA SACRA<br />

A caballo y sobre banderas, los santos patronos de la conquista<br />

española en América, la Virgen María y el apóstol Santiago,<br />

dirigían a solados y misioneros en el Nuevo Mundo. La conquista<br />

fue una empresa económica, política y religiosa. Los reinos<br />

europeos de entonces eran estados teocéntricos: la vida giraba<br />

alrededor del Dios cristiano y sus representaciones piadosas y<br />

milagrosas: Vírgenes, santos, mártires y el ejército celestial.<br />

A partir del estado de colonización del Nuevo Mundo, en 1521,<br />

contingentes de misioneros viajaban a América en grupos de<br />

doce, para ejecutar la otra colonización: la del evangelio. Ellos<br />

establecieron el cambio cultural más importante del politeísmo<br />

al monoteísmo; y para que el cambio politeísta no fuera brusco,<br />

se establecieron santos patronos por cada pueblo fundado.<br />

Muchas imágenes de santos patronos, cristos adoloridos y<br />

vírgenes milagrosas, vinieron inicialmente del reino de España; en<br />

los siglos posteriores los misioneros enseñaron a tallar y nuevas<br />

imágenes fueron hechas por los propios indígenas.<br />

En El Salvador, no se establecieron talleres de tallado conocidos<br />

como sucedió en Guatemala de la Asunción, actual Antigua<br />

Guatemala. Sin embargo, la talla indígena ha perdurado en los<br />

altares mayores y los artesonados barrocos de las iglesias del<br />

siglo XVIII de pueblos de indigenas como Panchimalco, San<br />

Vicente, Metapán, Chalchuapa, o Jicalapa, entre otras.<br />

Nunca se conoceran los nombres de estos prodigiosos<br />

escultores, primeros artífices de la fe. Durante la Colonia e<br />

incluso hasta entrado el siglo XX, el trabajo del imaginero sacro<br />

es anónimo.<br />

La imaginería sacra que se conserva en El Salvador ha sobrevivido<br />

desastres naturales como terremotos, huracanes, tempestades<br />

y desastres humanos como incendios, saqueos, y olvido. El<br />

arte sacro ha sido tan importante en nuestro país, que mucha<br />

de la imaginería popular actual tiene sus raíces en la escultura<br />

devocional, como reflejo de su fuertísima influencia en la<br />

formación de la identidad cultural salvadoreña.<br />

SACRED SCULPTURE<br />

Carried by horse and on the flags, the patron saints of the<br />

Spanish conquest in America, the Virgin Mary and the Apostle<br />

James, led soldiers and missionaries into the New World. The<br />

conquest was an economic, political and religious enterprise.<br />

The European kingdoms of the time were theocentric states:<br />

life revolved around the Christian God and godly and miraculous<br />

performances: virgins, saints, martyrs and heavenly host.<br />

Starting from the colonization of the New World in 1521,<br />

contingents of missionaries traveled to America in groups<br />

of twelve, to run the other colonization: the gospel. They<br />

established the most important cultural shift from polytheism<br />

to monotheism, and in order for that change to be accepted,<br />

they established patron saints for every town they founded.<br />

Many images of patron saints, Christ and the miraculous Virgin,<br />

initially came from the kingdom of Spain; in later centuries<br />

missionaries taught to carve and new images were made by the<br />

Indians themselves.<br />

In El Salvador, there were no carving workshops such as those<br />

that existed in Guatemala de la Asunción, now Antigua Guatemala.<br />

However, indigenous carving has been present on major altars<br />

and baroque coffered churches of the XVIII century, in many<br />

indigenous villages, such as Panchimalco, San Vicente, Metapán,<br />

Chalchuapa, Jicalapa, among others.<br />

The names of these prodigious sculptors, artisans of the faith,<br />

are not known. During the colonial period and even into the<br />

twentieth century, the work of Sacred Imagery is anonymous.<br />

The sacred imagery preserved in El Salvador has survived natural<br />

disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, storms and human<br />

disasters such as fires, looting, and neglect. Sacred art has been<br />

so important in our country, that much of the current popular<br />

imagery has its roots in devotional sculpture, reflecting its<br />

extremely strong influence on the formation of the Salvadoran<br />

cultural identity.<br />

40 41

Esta imagen de la Virgen de la<br />

Inmaculada Concepción, ha sido<br />

tallada con maestría en madera<br />

policromada, y viste, además, su<br />

traje real, vestido blanco y manto<br />

azul. La corona y sus aretes son<br />

de oro. S. XVII. (1.10 Mts.)<br />

Se trata de una de las imágenes<br />

y dogmas religiosos más<br />

difundidos en América. Su imagen<br />

fue popular desde los siglos XVII<br />

y XVIII en España, y ganó muchos<br />

devotos en América. El dogma,<br />

establece que la Virgen María fue<br />

concebida sin pecado original.<br />

La Inmaculada Concepción fue la<br />

patrona de España desde el siglo<br />

XVII y es además la santa patrona<br />

de Nicaragua.<br />

La Purísima, del siglo XVII. Esta imagen fue tallada según los cánones<br />

estéticos de su época. Muchas imágenes sacras obedecen además a<br />

profundos estudios de anatomía, donde las proporciones son parte<br />

de la justa belleza de la escultura. (50 cms.)<br />

La Purísima, of the XVII century. This image was carved according<br />

to the aesthetic canons of its time. Many sacred images obey also to<br />

more profound studies of anatomy, where the proportions are part of<br />

the beauty of the sculpture. (50 cms.)<br />

Virgen del Rosario, del siglo XVII. Muchos indígenas aprendieron de<br />

los misioneros la talla en madera. De esta manera, se establecieron<br />

dos tipos de escultura religiosa colonial: la talla primitivista y la talla<br />

de altura estética o preciosista. Esta virgen del Rosario pertenece a<br />

la talla primitivista, y fue elaborada en un tamaño pequeño, para ser<br />

venerada en un altar familiar. (47 cms.)<br />

Virgin of the Rosary, of the XVII century. Many Indians learned from<br />

the missioners the carving of wood. This way, two types of colonial<br />

religious sculptures were established: the primitive sculpting and the<br />

sculpting in stetic height. This Virgin of the Rosary belongs to the<br />

primitive sculture, and was elaborated in a small size, to be venerated<br />

in a family altar. (47 cms.)<br />

This image of the Virgin of the<br />

Immaculate Conception has<br />

been carved with mastery in<br />

polychrome wood and dresses,<br />

also, her royal robe, white dress<br />

and blue mantle. The crown and<br />

the earrings are of gold. S. XVII.<br />

(1.10 Mts.)<br />

It is about one of the images and<br />

religious dogmas more spread in<br />

America. The image was popular<br />

since the XVII and XVIII centuries in<br />

Spain, and won many devotees in<br />

America. The dogma, establishes<br />

that the Virgin Mary was conceived<br />

without original sin.<br />

The Immaculate Conception was<br />

the patron of Spain of the XVII<br />

century and is also the Holy Patron<br />

of Nicaragua.<br />

42 43

Virgen Niña del siglo XIX, (30 Cms.). Este tipo de imágenes<br />

sacras perdió popularidad en el avance del tiempo, por lo que se<br />

trata de una obra peculiar que arroja la riqueza de su época.<br />

Girl Virgin of the XIX century, (30 Cms.). This type of sacred<br />

images lost popularity in its time; therefore it is about a peculiar<br />

work yielding the richness of its time.<br />

44 45

La imaginería fue un intenso<br />

movimiento cultural: Los santos<br />

patronos no pertenecían solo a<br />

las iglesias, se colocaban en las<br />

casas en los altares familiares, en<br />

signo devocional.<br />

Los misioneros fundaron<br />

cofradías para evangelizar a<br />

grandes grupos poblacionales,<br />

que también difundieron la<br />

devoción por la escultura sacra.<br />

Solo en el siglo XVIII, a la llegada<br />

del obispo de Guatemala Pedro<br />

Cortez y Larraz, había en el<br />

actual El Salvador, alrededor de<br />

700 cofradías, cada una de ellas<br />

con su santo patrono asignado<br />

y por tanto con su obligatoria<br />

imagen devocional.<br />

The imagery was an intense<br />

cultural movement: patron<br />

saints belonged not only<br />

to the churches, they were<br />

placed in homes on family<br />

altars, as a sign of devotion.<br />

San José y el niño, tallado en madera y<br />

coronado con plata, S. XVIII. (29 Cms.).<br />

Saint Joseph and the child, carved in<br />

wood and crowned with silver, XVIII<br />

century (29 Cms.).<br />

Missionaries founded<br />

Confraternities in order to<br />

evangelize large population<br />

groups, which also spread<br />

the devotion to the sacred<br />

sculpture. In the XVIII century,<br />

at the arrival of the bishop<br />

of Guatemala Pedro Cortez<br />

and Larraz, the actual El<br />

Salvador, had about 700<br />

Confraternities, each one with<br />

their patron saint assigned and<br />

therefore with its mandatory<br />

devotional image.<br />

Cristo crucificado para altar familiar. De pequeño formato, en madera<br />

policromada; pertenece al siglo XVII. (60 Cms.)<br />

Crist crucified for family altar. Of small size, in polychrome wood,<br />

belongs to the XVII century. (60 Cms.)<br />

Arcángel Miguel, madera policromada, figura de vestir, Siglo XIX. (1.38 metros).<br />

Archangel Michael in polychrome wood, dressed figure, of the XIX century. (1.38 meters).<br />

46 47

Muchas de las maneras de evangelizar en la Colonia fueron<br />

vinculadas a los “misterios bíblicos” como el del nacimiento<br />

de Jesús, expresado en estas imágenes de la Virgen María<br />

embarazada y San José en su tránsito a Belén. Imágenes del<br />

siglo XVIII.<br />

Many of the ways to evangelize in the Colony were linked to the<br />

“biblical mysteries” such as the birth of Jesús, expressed in these<br />

images of the Virgin Mary pregnant and San José in their path to<br />

Bethlehem. Images of the XVIII century.<br />

La Posada. San José y la Virgen María, misterio para altar familiar<br />

del siglo XVIII. (1.50 Mts.)<br />

The Hostel. Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary, mystery for family altar from<br />

the XVIII century. (1.50 Mts.)<br />

San José y la Virgen María, misterio para altar familiar del siglo XIX.<br />

(0.80 Mts.)<br />

Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary, mystery for family altar from<br />

the XIX century. (0.80 Mts.)<br />

48 49

Niño Dios dormido, tallado en el siglo XVIII.<br />

God child asleep, carved in the XVIII century.<br />

Cristo flagelado o Jesús cautivo en madera policromada del siglo XVIII. Pertenece a la Lista roja de bienes<br />

culturales en peligro de Centroamérica y México. Museo Nacional de Antropología David J. Guzmán.<br />

Jesus Christ scourged or captive in polychrome wood from the XVIII century. Belongs to the red list of<br />

cultural goods in danger from Central America and Mexico. Museo Nacional de Antropología David J. Guzmán.<br />

50 51

Ángel doliente, Cementerio de San Miguel.<br />

Angel suffering, San Miguel Cementery.<br />

52 53

MONUMENTOS FUNERARIOS<br />

Paralela a la fundación de los héroes en las plazas, otra arquitectura<br />

monumental se gestaba en los cementerios. Ángeles contritos,<br />

vírgenes dolientes, viudas desconsoladas, cristos y columnas truncadas<br />

que evidenciaban una vida joven terminada en exabrupto, convertían a los<br />

cementerios salvadoreños de finales del siglo XIX e inicios del siglo XX en<br />

ciudades, recuerdos monumentales, y perecederos testimonios del<br />

dolor por la pérdida de los seres amados.<br />

Los monumentos funerarios son el reflejo de las ciudades, donde<br />

encontramos a los héroes convertidos en hombres agonizantes.<br />

La monumentalidad de la plaza los inscribía en la vida pública y el<br />

mausoleo en la posteridad.<br />

En los cementerios de las principales ciudades de El Salvador se<br />

erigieron mausoleos, capillas y conjuntos escultóricos de manufactura<br />

italiana y estilo grecorromano, de influencia neoclásica, para recordar<br />

a los fallecidos.<br />

Este apogeo cultural, de espíritu europeo, permitió la migración<br />

de artistas y maestros artesanos a Latinoamérica. La capacidad<br />

económica fruto de la bonanza del café permitió que artistas como<br />

Francesco Durini, Alberto y Antonio Ferracuti y Martin Barsanti, artífices<br />

de la monumentalidad de San Salvador y Santa Ana a inicios del siglo<br />

XX, importaran desde las canteras de Carrara, esculturas de belleza y<br />

calidad que tradujeran los sentimientos de los dolientes salvadoreños.<br />

El mausoleo y la muerte alcanzaron puntos artísticos invaluables en<br />

El Salvador; la majestuosidad del monumento fúnebre representaba<br />

también el poder económico del fallecido y una valoración estética<br />

de los ciudadanos de entonces.<br />

El surgimiento de esta nueva tradición estética era el reflejo<br />

bonancible de la economía cafetalera producto de las exportaciones<br />

exitosas del “grano de oro”. Muchas de estos monumentos funerarios<br />

son testimonio de una época de esplendor en El Salvador.<br />

FUNERARY MONUMENTS<br />

Parallel to the foundation of the heroes in the plazas, another<br />

monumental architecture was brewing in the cemeteries. Salvadorean<br />

cemeteries turn at the end of the XIX century and beginning of the XX<br />

century in cities of the dead, monumental memories and perishable<br />

testimonies of grief for the loss of loved ones. Angels contrite,<br />

mourner virgins, widows bereaved, Christs, and broken columns<br />

showed a young life ended in outburst.<br />

The funerary monuments are the reflection of the cities, where we<br />

found the heroes turned into agonizing men. The monumentality of<br />

the plaza inscribed them in public life and the mausoleum for posterity.<br />

To remember the fallen, the cemeteries of the main cities of El Salvador<br />

become mausoleums that erected, chapels and Italian manufacturing<br />

sculptures and Greco-Roman Style of Neoclassic influence were<br />

created fisically.<br />

The cultural peak, of eurorean spirit, allowed the migration of artists<br />

and artisan masters to Latino America. The economic capacity, as a<br />

result of the boom from the coffee, allowed artists like Francesco<br />

Durini, Alberto and Antonio Ferracuti, and Martin Barsanti, makers of the<br />

monumentality of San Salvador and Santa Ana at the beginning of the<br />

XX century. Imported from the quarries of the Carrara, sculptures of<br />

beauty and quality translate the feelings of the Salvadorean mourners.<br />

The mausoleum and death reached invaluable artistic sites in<br />

El Salvador. The majesty of the funeral monument represented also<br />

the economic power of the fallen and an aesthetic appreciation of the<br />

citizens of the time.<br />

The emergence of this new aesthetic tradition was the fair reflection<br />

of the economy as a result of the successful exportation of the “gold<br />

grain”. Many of these funeral monuments are testimony of a time of<br />

splendor in El Salvador.<br />

El ángel de la muerte arrebata de su sueño a las hermanitas<br />

María Matilde Gregoria y Sara Natalia Francisca Gregoria Aguilar.<br />

Tallado con intenso dramatismo, representa una de las historias más<br />

tristes y comunes de la época: muchos niños morían antes de llegar a sus<br />

primeros años de vida. Este mausoleo fue erigido en la década de 1920 y<br />

es el único en mármol rosa en el cementerio<br />

Los Ilustres, en San Salvador, realizado en Marsella, Francia.<br />

The angel of death takes away the sleep of the little sisters<br />

María Matilde Gregoria and Sara Natalia Francisca Gregoria Aguilar.<br />

Carved with intense drama, represents one of the saddest and common<br />

histories of the time: many children would die before reaching their first<br />

years of life. This mausoleum was erected in the 1920’s and is the only one<br />

in pink marble in the cemetery called Los Ilustres in San Salvador,<br />

made in Marsella, Francia.<br />

54 55

El mausoleo de Manuel Calvo, nacido en Cádiz, España, en 1835 y<br />

fallecido en San Miguel en 1898, es uno de los más impresionantes<br />

del Cementerio de San Miguel.<br />

Conocido durante su vida como “el benefactor de los desvalidos”,<br />

fue el principal donante del hospicio y del hospital de San Miguel.<br />

Su mausoleo fue aprobado por una junta municipal el mismo año<br />

de su muerte. Es un conjunto escultórico compuesto por una<br />

urna funeraria rodeada de medallones y poemas, a cuyos pies<br />

descansan seis niños, que representan a los huérfanos y enfermos<br />

socorridos por él.<br />

The mausoleum of Manuel Calvo, born in Cádiz, Spain, in 1835 and<br />

died in San Miguel in 1898, is one of the most impressive of the<br />

Cemetery at San Miguel.<br />

Known during his life as the “benefactor of the helpless”, was<br />

the main donor of the hospice and the hospital of San Miguel.<br />

The municipal board approved his mausoleum the same year of<br />

his death. It is a sculptural set composed by one funerary urn,<br />

surrounded by medallions and poems, at his feet lie six children<br />

who represent the orphans and the sick helped by him.<br />

Grupo escultórico que representa a los<br />

niños socorridos por Manuel Calvo<br />

en el siglo XIX.<br />

Sculptural Group that represents<br />

the children helped by Manuel Calvo<br />

in the XIX century.<br />

56 57

Virgen doliente llora sobre el mausoleo de la familia Charlaix<br />

en el cementerio de San Miguel.<br />

La combinación del mármol negro del fondo destaca el<br />

mármol blanco de la escultura, diseño de la Marmolería La<br />

Colonial, propiedad de los hermanos Ferracuti, realizado en<br />

1947. En él se encuentran enterrados miembros de la familia<br />

desde finales del siglo XIX hasta mediados del siglo XX.<br />

Las imágenes que decoraban los mausoleos eran encargadas<br />

por catálogo a las canteras italianas, por lo general de Carrara.<br />

Sorrow Virgin cries over the mausoleum of the Charlaix<br />

family at the cemetery of San Miguel.<br />

The combination of the black marble at the bottom of<br />

sculpture highlights the white marble, design of the Marble<br />

Store La Colonial, property of the Ferracuti brothers, made<br />

in 1947. In it, we find members of the family buried since the<br />

end of the XIX century until mid XX.<br />

The images that decorated the mausoleums were ordered<br />

by catalog to the Italian quarries, in general from the Carrara.<br />

58 59

Mausoleo Marcelino Arguello cementerio de San Miguel. Fallecido<br />

en 1889, su mausoleo de mármol fue importado y erigido a la<br />

entrada del cementerio. Una niña que sostiene en la mano una<br />

corona luctuosa y unos ángeles rodean su urna funeraria. El<br />

mausoleo es un recuerdo de su esposa y sus hijos.<br />

Mausoleum Marcelino Arguello cemetery of San Miguel. Dead in<br />

1889, his mausoleum of marble was imported and erected at the<br />

entrance of the cemetery. A girl holds in her hand a mournful<br />

crown and angels surround his funeral urn. The mausoleum is a<br />

memory of his wife and children.<br />

60 61

Detalle del cuello de la túnica del ángel del mausoleo de la familia Bustamante.<br />

Neck detail tunic angel from Bustamante family mausoleum.<br />

Filigranado de la túnica de un Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, esculpido en la década de 1950.<br />

Filigree of the tunic of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, sculpted in the 1950’s.<br />

Mausoleo de José María Peralta (1808-1883)<br />

gobernó El Salvador entre 1859 y 1861.<br />

En este conjunto escultórico destacan los<br />

medallones tallados en mármol a modo de<br />

retrato de los miembros de la familia Peralta.<br />

Guirnalda de flores de la escultura “La Novia”, Lidia S. Cristales de López,<br />

Cementerio de Los Ilustres.<br />

Garland of flowers of the sculpture “the Bride”, Lidia S. Cristales de López,<br />

Cemetery of Los Ilustres.<br />

Pie del ángel de la muerte del mausoleo de las hermanitas Aguilar.<br />

Angel of Death´s foot, from the mausoleum of the Aguilar little sisters.<br />

Mausoleum of José María Peralta (1808-1883)<br />

governed El Salvador between 1859 and 1861.<br />

In this sculptural set the medallions<br />

are highlighted carved in marble as a<br />

portrait of the members of the Peralta family.<br />

62 63

La escultura de Lidia S. Cristales de López, quien murió en 1924, es<br />

uno de los mausoleos de mayor preciosismo del Cementerio de<br />

Los Ilustres de San Salvador. La representa con su traje de novia a la<br />

usanza de la época.<br />

El mausoleo fue encargado por su viudo, el médico César Emilio López,<br />

a la compañía de los hermanos Antonio y Alberto Ferracuti, quienes<br />

se constituyeron como los líderes en el diseño de los monumentos<br />

funerarios de El Salvador de las décadas de 1920 a 1960.<br />

The sculpture of Lidia S. Cristales de López, who died in 1924, is one<br />

of the most precious mausoleums of the Cemetery Los Ilustres from<br />

San Salvador. Is presented with her bride gown in the style of the time.<br />

The mausoleum was commissioned by his widower, doctor César<br />

Emilio López, to the company of the brothers Antonio and Alberto<br />

Ferracuti, who were constituted as the leaders in the design of the<br />

funerary monuments of El Salvador from the 1920’s to 1960’s.<br />

Este monumento funerario de la familia de Eugenio Aguilar está<br />

dedicado a la maternidad: La mujer sostiene a una niña pequeña y se<br />

erige sobre la urna funeraria familiar. Constituye uno de los patrimonios<br />

más antiguos del Cementerio de Los Ilustres, pertenece a la década<br />

de 1860, y es anterior al apogeo del mármol funerario de las décadas<br />

1900 a 1940 en este cementerio.<br />

This funerary monument of the family of Eugenio Aguilar is dedicated<br />

to the maternity. The woman is holding a little girl and is erected<br />

over the family urn. Constitutes one of the eldest heritages of the<br />

Cemetery Los Ilustres, belongs to the 1860’s, and is before the boom<br />

of the funerary marble from the 1900´s to 1940’s in this cemetery.<br />

64 65

Este mausoleo de inicios del siglo XX es un conjunto neoclásico que incluye a las<br />

tres virtudes teologales: Fe, Esperanza y Caridad representada por ángeles.<br />

This mausoleum from the beginning of XX century is a neoclassic set, which includes<br />

the three theological virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity represented by angels.<br />

La escultura de la tumba de la familia Maestre, fue tallada magistralmente en<br />

mármol rosa en la década de 1920, refleja el preciso momento del tránsito de la<br />

muerte a la vida eterna. Cementerio de Chalchuapa, departamento de Santa Ana.<br />

The sculpture of the thumb of the Maestre Family, was carved magisterially<br />

in pink marble in the 1920’s, reflects the precise moment of the passage from<br />

death to eternal life. Cemetery of Chalchuapa, city of Santa Ana.<br />

66 67

Mausoleo de Tomás Regalado, Cementerio Santa Isabel, Santa Ana.<br />

Los restos del antiguo presidente de El Salvador Tomás Regalado (1861-1906) se encuentran<br />

en el mausoleo de mayor proporción y riqueza del cementerio de Santa Ana.<br />

En su luto, su viuda encargó un homenaje monumental. Diseñado y construido por el<br />

maestro italiano Francesco Durini, el mausoleo tiene una profunda relación con las<br />

aspiraciones políticas de Regalado y refleja los valores clásicos de la justicia. Fue erigido<br />

en mármol, bronce y granito en 1908, dos años después de la muerte del caudillo, acaecida<br />

en Guatemala el 11 de julio de 1906.<br />

El mausoleo es una capilla de influencia neoclásica rodeada de esculturas de mármol y<br />

bronce, entre las que sobresalen la Justicia y la Libertad. A sus costados, las palmas,<br />

símbolo cristiano de la vida eterna, custodian la entrada a la capilla.<br />

Mausoleum of Tomás Regalado, cemetery of Santa Isabel, Santa Ana<br />

Los remains of the former president of El Salvador Tomás Regalado (1861-1906) are found<br />

in the mausoleum of greater proportion and wealth of the cemetery of Santa Ana.<br />

In her grief, his widow commissioned a monumental tribute. Designed and constructed<br />

by the Italian master Francesco Durini, the mausoleum has a profound relation with the<br />

political aspirations of Regalado and reflects the classical values of justice. It was erected<br />

in marble, bronze and granite in 1908, two years after the death of the caudillo (leader),<br />

occurred in Guatemala on July 11th 1906.<br />

The mausoleum is a chapel of Neoclassic influence, it is surrounded by marble and bronze<br />

sculptures, among which Justice and Freedom stand out. On the sides, palms, Christian<br />

symbol of eternal life, guard the entrance to the chapel.<br />

68 69

Mausoleo de la familia Durán, Cementerio de Ahuachapán, cuyas esculturas denotan los<br />

valores familares: Industria, trabajo, agricultura y comercio.<br />

Mausoleum of the Durán Family, Cementery of Ahuachapán, whose sculptures denote the<br />

family values: Industry, work, agriculture, and commerce.<br />

Esta escultura representa, con un tren rodeado de trigo, la industria. La familia Durán fue una de las más destacadas en la vida económica<br />

y política de Ahuachapán a inicios de siglo XX. Es el único mausoleo encontrado cuyas alegorías no se relacionan con valores cristianos<br />

ni con el pesar y la tristeza, sino con representaciones de mujeres grecorromanas.<br />

This sculpture, with a train surrounded by wheat, represented the industry. The Durán Family was one of the most prominent families in<br />

the economic and politic life of Ahuachapán at the beginning of the XX century. It is the only mausoleum found with allegories that are<br />

not related to Christian values or sorrow and sadness, but with representations of the Greco Roman women.<br />

70 71

LO PROFANO<br />

LO PROFANO<br />

El beso de la vida y la pasión por lo terrenal son también representadas<br />

en El Salvador a inicios del siglo XX. Muchas esculturas de mármol que<br />

vinieron al país fueron destacadas en el espacio público a lo largo de la<br />

nación. La escultura monumental alegórica, desparece en su mayoría y<br />

es a inicios del siglo XX definitoria para construir el imaginario nacional.<br />

En 1911, se inaugura en San Salvador el Paseo Independencia, una<br />

alameda que constaba con un paseo escultórico, destacado por<br />

figuras profanas: leones rampantes, esfinges, mujeres que encargan<br />

la libertad y la república.<br />

En Santa Ana y San Miguel, estas esculturas representan las ideas<br />

estéticas de la época basada en la mitología grecorromana y en la<br />

historia clásica. De esta manera, El Salvador de inicios del siglo XX<br />

configura su fisonomía con intenciones neoclásicas.<br />

The kiss of life and passion for the earthly are also represented in<br />

El Salvador at the beginning of the XX century. Many marble sculptures<br />

that came to the country were prominent in public spaces throughout<br />

the nation. The allegoric monumental sculptures almost disappear<br />

completely and it is at the beginning of the XX century that the<br />

construction of the national imagination is definitory.<br />

In 1911, it is inaugurated in San Salvador The Paseo Independencia; an<br />

avenue, which had a sculptural ride, highlighted by secular figures:<br />

rampant lions, sphinxes, women who entrust the freedom, and the<br />

republic.<br />

In Santa Ana and San Miguel, these sculptures represent the aesthetic<br />

ideas of the time based in the Greco-Roman mythology and the<br />

classic history. This way, El Salvador at the beginning of the XX<br />

century, configures its physiognomy with Neo-Classic intentions.<br />

Apolo y las musas de la comedia y la tragedia colocadas en el Teatro de Santa Ana. El Teatro<br />

se inagura en 1910 y representa la obra arquitectónica más hermosa y moderna de su época.<br />

Las esculturas son talladas en Piedra Santa, Italia, y traídas al país por el italiano Martín Barsanti.<br />

Apollo and the muses of comedy and tragedy placed in The Theatre of Santa Ana. The<br />

Theatre was inaugurated in 1910 and represents the most beautiful and modern architectonic<br />

work of its time. The sculptures are carved at Piedra Santa, Italy and brought to the country<br />

by the Italian Martín Barsanti.<br />

Esfinge, Zacatecoluca, departamento de La Paz.<br />

Sphinx, Zacatecoluca, La Paz province.<br />

72 73

Estas esculturas, de corte grecorromano y talladas en mármol, se<br />

encuentran en los jardines de la alcaldía de San Miguel. Representan las<br />

Cuatro estaciones y los cinco continentes.<br />

These sculptures, of Greco-Roman cut and carved in marble, are found<br />

in the gardens of the town hall office of San Miguel. They represent<br />

the four seasons and the five continents.<br />

Fueron colocadas en el parque central de San Miguel en 1921. Miden 1.50<br />

metros de altura y son representaciones alegóricas con gran riqueza<br />

en su talla. Entre las décadas de 1920 y finales del siglo XX, una de<br />

ellas, América, fue robada. En el año 2004, la alcaldía las restauró y las<br />

trasladó a sus jardines.<br />

They were placed in the Central Park at San Miguel in 1921. They<br />

measure 1.50 meters high and are rich allegoric representations in<br />

its size. Between the 1920’s and the end of the XX century, one of<br />

them, America, was stolen. In 2004, the town hall restored them and<br />

transferred them to its gardens.<br />

Es muy probable que estas esculturas hayan sido creadas en Italia,<br />

como el resto de la estatuaria, fúnebre y profana, que vino a El Salvador<br />

desde 1880 hasta 1940.<br />

It is probably that these sculptures have been created in Italy, like the<br />

rest of the statuary, funerary and profane, that came to El Salvador<br />

from 1880 until 1940.<br />

Invierno. Coronada con los frutos de la estación y la antorcha de la libertad.<br />