Mapping Madrid. IED Madrid. PhotoEspaña 2009

Catálogo de la exposición de Tete Álvarez en el Palacio de Altamira de Madrid. Textos: Pablo Jarauta. Pedro Medina

Catálogo de la exposición de Tete Álvarez en el Palacio de Altamira de Madrid. Textos: Pablo Jarauta. Pedro Medina

- TAGS

- arte contemporáneo

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

Ciclo Miradas sobre la arquitectura<br />

<strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong>, Gabinete de Exposiciones del Palacio de Altamira<br />

12 de junio – 24 de julio de <strong>2009</strong>

Istituto Europeo di Design<br />

Presidente | President: Francesco Morelli<br />

Istituto Europeo di Design <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

Director | Director: Riccardo Marzullo<br />

Director científico | Science Director: Francisco Jarauta<br />

Subdirector | Deputy Director: José Piquero<br />

Secretaria de dirección | Director’s Assistant: Maiko Arrieta<br />

Director de <strong>IED</strong> Master | <strong>IED</strong> Master Director: Dario Assante<br />

Director de <strong>IED</strong> Empresas | <strong>IED</strong> Business Director: Manuel Jiménez<br />

Responsable de Comunicación | Communications Manager: Marisa Santamaría<br />

EXPOSICIÓN | EXHIBIT<br />

Comisarios | Curators: Javier Maseda y Pedro Medina<br />

Coordinadora | Coordinator: Elena Velasco<br />

Desarrollo técnico de la web | Technical website development: Blogestudio<br />

Desarrollo técnico de la instalación | Technical installation development: Jarl Einar Ottestad<br />

y Anders Restad<br />

CATÁLOGO | CATALOGUE<br />

Editor | Publisher: Pedro Medina<br />

Diseño y maquetación | Design and layout: Natalia López<br />

Creatividad <strong>IED</strong> | <strong>IED</strong> Creative Department: Javier Maseda, Josina Llera, Thiago Esquivel, Raquel<br />

García y Natalia López<br />

Traductora | Translator: Joanna Porter<br />

Fotografías de sala | Room photographs: Marta Orozco<br />

Publica | Published by: Istituto Europeo di Design <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

Palacio de Altamira. C/ Flor Alta, 8. 28004 <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

iedmadrid.com<br />

abreelojo.com<br />

Agradecimientos | Acknowledgements: Daniel Caiza, Eduardo Caiza, Ana Díaz, David Fonseca,<br />

Marta García, Pablo Jarauta, Miguel Matorras, Juana Muñoz, Raúl Ortega, Irene Porras,<br />

Ximo Salvà, Iván Vidal y Jaime Yaguana<br />

© de | of: Ciudades líquidas. <strong>Madrid</strong> y Transurbancia: Tete Álvarez<br />

© de los textos | of the texts: sus autores y el Istituto Europeo di Design | the authors and<br />

Istituto Europeo di Design<br />

ISBN: 978-84-937060-3-6

Índice<br />

14<br />

26<br />

48<br />

56<br />

66<br />

¿Para qué un mapa?<br />

Why a Map?<br />

Cartografías de la realidad. Mirada, fotografía<br />

y mapa<br />

Cartographies of Reality. Gaze, Photography<br />

and Map<br />

Ciudad líquida. <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

Ciudad líquida. <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

Transurbancia<br />

Transurbancia<br />

mappingmadrid.com<br />

mappingmadrid.com

¿Para qué un mapa?<br />

Pablo Jarauta<br />

I. Todo empezó el día en que un hombre decidió<br />

observar los alrededores. Empeñado en reconocer<br />

su entorno más inmediato, este observador<br />

antediluviano escogió un punto elevado y comenzó<br />

a girar sobre sí mismo. En primer lugar,<br />

divisó los cobertizos de su aldea. Luego, el huerto,<br />

con sus hortalizas y sus endebles frutales.<br />

Más allá, pudo ver el río, y un poco más lejos, las<br />

robustas cabezas del ganado. Siguió el observador<br />

con los ojos bien abiertos hasta que topó<br />

con una gran montaña. Cegado por esta imponente<br />

imagen, decidió dar el día por terminado.<br />

A la mañana siguiente, el observador regresó al<br />

punto elevado y reinició el examen visual de sus<br />

alrededores. Primero, contempló a los niños de<br />

la aldea corriendo desbocados tras un conejo.<br />

Después, una charca plagada de ranas. Se abrió<br />

entonces ante sus ojos una llanura que no tenía<br />

fin. El observador se sorprendió: una delgada<br />

línea unía el cielo con la tierra, impidiéndole<br />

ver más allá. Había dado con el horizonte. Extrañado,<br />

regresó a la aldea, encendió un fuego<br />

y reflexionó durante horas. Había identificado<br />

todos los elementos de su entorno, pero aquella<br />

reverberada línea le ocultaba las cosas más lejanas.<br />

El observador había encontrado el límite de<br />

su visión: al igual que una montaña, el horizonte<br />

también velaba su mirada.<br />

“El mapa ha entrado en la época de la sospecha, ha perdido su<br />

inocencia. Ya no podemos, hoy en día, contemplar una historia de la<br />

cartografía sin una dimensión antropológica, atenta a la especificidad<br />

de los contextos culturales, y teórica, que refleje la naturaleza misma<br />

del objeto, sus poderes intelectuales e imaginarios”<br />

(Christian Jacob, L’Empire des cartes,)<br />

En el intento por formarse una imagen del mundo,<br />

el observador había descubierto que sus alrededores<br />

abundaban en misterios y enigmas,<br />

que existían límites y zonas incógnitas. Los<br />

elementos de su entorno no bastaban para representar<br />

el mundo en el que vivía, hacían falta<br />

nuevos lugares regidos por nuevas lógicas. De<br />

tal modo, el observador decidió que si bien no<br />

podía ver más allá del horizonte, sí que podía<br />

nombrarlo. Regresó nuevamente al punto elevado<br />

y de frente a la llanura fue señalando con el<br />

14 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

15

dedo diferentes puntos en el horizonte, asignando<br />

un nombre a cada uno de ellos. Estos nombres<br />

señalaban lugares que no existían pero que<br />

explicaban el entorno del observador: paraísos,<br />

avernos, islas, dioses, monstruos, abismos... que<br />

daban cuenta del curso de los ríos, de los ciclos<br />

del día y la noche, de la relación con la naturaleza,<br />

del origen y el destino. El observador había<br />

completado su imagen del mundo: a los elementos<br />

de su entorno había sumado una interminable<br />

lista de nombres, de lugares inexistentes<br />

que terminaron por configurar sus creencias,<br />

sus costumbres, su relación con el mundo.<br />

II. Esta pequeña historia sobre cómo un observador<br />

cualquiera construyó su mapa del mundo<br />

esconde un esquema que podría sernos de<br />

gran utilidad a la hora de comprender el papel<br />

que juegan las producciones cartográficas hoy<br />

en día. Se trata de un esquema muy simple que<br />

ha estado presente a lo largo de toda la historia<br />

de la cartografía y que atiende al hecho<br />

de habitar una esfera y a la imposibilidad de<br />

una imagen total y directa de nuestro mundo.<br />

Ciertamente, el hecho de habitar una superficie<br />

curva privó a nuestro observador de una<br />

imagen de su mundo, esférico e inaprensible.<br />

Para salvar esta dificultad y ante la necesidad<br />

de una imagen total que explicara el funcionamiento<br />

de su entorno y, en definitiva, de todo<br />

el universo, el observador tuvo que construir<br />

la imagen que quedaba más allá del horizonte,<br />

la primera frontera. Observar los alrededores,<br />

construir el afuera: he ahí el fundamento de<br />

todo mapa, sus entrañas, su razón última.<br />

III. Podría decirse que la tarea de representar el<br />

espacio es tan antigua como la de imaginarlo. En<br />

otras palabras, los mapas son tan antiguos como<br />

las utopías. El primer hombre que trazó un dibujo<br />

de su aldea ya tenía utopías: en su cabeza dormían<br />

despiertos incontables nombres que señalaban<br />

la existencia de lugares imaginarios. Mientras<br />

dibujaba frágiles diagramas de las murallas<br />

de su ciudad, de sus ríos y sus campos, el mundo<br />

se llenó de nombres que anunciaban por doquier<br />

lugares de luces y sombras. Estos nombres no<br />

tardaron en saltar del lenguaje al mapa, pues se<br />

habían consolidado como piezas fundamentales<br />

en el proceso de la elaboración de una imago<br />

mundi. Las utopías, esa construcción del afuera<br />

cartográfico, forman parte del mundo tanto como<br />

la tierra y el mar. Recordemos brevemente lo que<br />

de la Atlántida nos cuenta Platón: “Hubo terribles<br />

temblores de tierra y cataclismos. Durante un día<br />

y una noche horribles, todo nuestro ejército fue<br />

tragado de golpe por la Tierra, y del mismo modo<br />

la Atlántida se abismó en el mar y desapareció.<br />

He ahí por qué todavía hoy ese mar de allí es difícil<br />

e inexplorable, debido a sus fondos limosos y<br />

muy bajos que la isla, al hundirse, ha dejado” (Timeo<br />

24c-25a). Las utopías construyen el mundo,<br />

se hunden dejando fondos limosos, huella geológica<br />

de un lugar inexistente.<br />

“Observar los alrededores,<br />

construir el afuera: he ahí<br />

el fundamento de todo<br />

mapa, sus entrañas,<br />

su razón última”<br />

IV. En este sentido, la construcción del afuera<br />

transforma por completo la naturaleza de<br />

la producción cartográfica. En este esquema<br />

o proceso los instrumentos necesarios para el<br />

establecimiento de una imagen del mundo no<br />

coinciden con los utilizados en la representación<br />

de nuestro entorno. La escala, los cálculos,<br />

el cartabón o el cuadrante quedan ensombreci-<br />

dos por meros nombres de lugares inexistentes,<br />

por mares sin orillas, por objetos y seres<br />

prodigiosos… incluso por una proyección de<br />

nosotros mismos. Estos elementos tan propios<br />

de la utopía como de la cartografía hacen del<br />

mapa un proyecto sobre el mundo. No se trata<br />

ya de representar fielmente un territorio, sino<br />

de cómo queremos que sea. En el mapa se citan<br />

ciencia y literatura, observación e imaginación,<br />

se dan por igual distintos procedimientos<br />

que lo encaminan hacia una voluntad de completar<br />

el gran mosaico del mundo, de comprender<br />

nuestras formas de vida, de aprender a relacionarnos<br />

con la alteridad a partir de nuestro<br />

entorno. En un mapa la representación se torna<br />

proyecto, va más allá del objeto y se sumerge<br />

en la inmensidad de la superficie terrestre, en<br />

la curva sin fin del horizonte, en lo inagotable<br />

de nuestros sueños. Recordando de nuevo las<br />

palabras de C. Jacob, la condición necesaria<br />

para el nacimiento de la cartografía no es tanto<br />

la convicción de su materialidad, sino la convicción<br />

de la posibilidad de su materialización.<br />

Los mapas nacieron como proyecto, nacieron<br />

como el lugar natural de las utopías, pues éstas<br />

solamente existen en su representación.<br />

V. Ahora bien, podríamos pensar que actualmente<br />

estas historias han quedado desfasadas<br />

por una pretensión cartográfica encaminada<br />

hacia la objetividad, la precisión o la neutralidad,<br />

que ya no queda sitio en este mundo para<br />

las utopías, pues no hay rincón de la Tierra que<br />

no haya sido descubierto, clasificado o explotado.<br />

Vivimos en un mundo conocido, hemos<br />

dispuesto en el cielo ojos electrónicos que escrutan<br />

el territorio, que nos localizan, que hacen<br />

de la representación del mundo un asunto<br />

aséptico, casi funcional. Ahora que lo conocemos<br />

todo, que podemos viajar rápida y cómodamente<br />

por todo el orbe, podría parecer que<br />

los mapas han perdido su componente utópico<br />

entregándose enteramente a una lógica de la<br />

objetividad, que los mapas solo sirven para<br />

orientarnos, para desplazarnos sin riesgos de<br />

un lugar a otro, para encontrar una calle, una<br />

tienda o un hospital.<br />

“Los mapas son un reflejo<br />

de la cultura que los ha<br />

realizado, en ellos pueden<br />

encontrarse, aunque sea<br />

en los espacios en blanco,<br />

en sus silencios, los<br />

diferentes proyectos de<br />

cada época”<br />

Sin embargo, es precisamente este exceso de<br />

precisión y objetividad de nuestros días el que<br />

nos exige un retorno a los inicios de la cartografía,<br />

a nuestro observador, a los tiempos en<br />

los que poco o nada se conocía, al momento<br />

utópico de la construcción del mundo. Como<br />

señalara en su día John B. Harley, la cartografía<br />

raras veces es lo que los cartógrafos dicen<br />

que es. Los mapas no son objetivos, precisos<br />

o neutrales, esconden poderes intelectuales e<br />

imaginarios que los sitúan como una valiosa<br />

producción cultural. Los mapas son un reflejo<br />

de la cultura que los ha realizado, en ellos pueden<br />

encontrarse, aunque sea en los espacios en<br />

blanco, en sus silencios, los diferentes proyectos<br />

de cada época. Hoy en día nos vemos ante<br />

la imperiosa necesidad de crear nuevos proyectos<br />

sobre el mundo, nuevas representaciones<br />

que den cuenta de las fracturas existentes<br />

en este mundo pretendidamente homogéneo.<br />

En esta dirección, los mapas seguirán siendo<br />

el mejor lugar para nuestras utopías.<br />

16 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 17

Why a Map?<br />

Pablo Jarauta<br />

I. It all began the day man decided to observe<br />

his surroundings. Determined to recognise his<br />

most immediate environment, this antediluvian<br />

observer chose an elevated place and began to<br />

turn around. Initially, he saw the huts in his village.<br />

Then he saw the vegetable plot, with its<br />

feeble fruit trees. In the distance he could see the<br />

river, and, a bit further, the robust heads of cattle.<br />

The observer kept his eyes open and continued<br />

to look into the far-off distance, where he could<br />

see a huge mountain. Unable to see beyond this<br />

overwhelming view, he decided to stop for the<br />

day. On the next morning, the observer returned<br />

to the elevated spot and continued to examine<br />

his surroundings. First, he contemplated the<br />

children in the village, running excitedly after a<br />

rabbit. Next, he noticed a pond full of frogs, and<br />

it was at this point that an endless plain opened<br />

up before his eyes. The observer was surprised:<br />

a thin line connected the sky and the earth, making<br />

it impossible for him to see beyond it. He<br />

had found the horizon. Puzzled, he returned to<br />

the village, lit a fire, and thought about it for<br />

hours. He had identified all of the elements in<br />

his surroundings, but that shimmering line concealed<br />

the most distant things. The observer<br />

had found the limits of his vision: like a mountain,<br />

the horizon veiled his gaze.<br />

“The map has entered a phase of suspicion; it has lost its innocence.<br />

Today, we can no longer contemplate a history of cartography without<br />

taking into account its anthropological dimension, subject to its<br />

specific cultural contexts, and its theoretical dimension, which reflects<br />

the nature of the object itself, its intellectual and imaginary powers”<br />

(Christian Jacob, L’Empire des cartes)<br />

In his attempt to build an image of the world, the<br />

observer had discovered that his surroundings<br />

were full of mysteries and enigmas, that there<br />

were limits and unknown areas. The elements<br />

around him were not enough to represent the<br />

world in which he lived; it was necessary to<br />

find new places ruled by new propositions. So<br />

the observer decided that, whilst he could not<br />

see beyond the horizon, he could at least name<br />

it. He returned to the elevated place and, fac-<br />

18 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

19

ing the plain, he pointed his finger at different<br />

parts of the horizon, giving each a name. These<br />

names referred to places that did not exist but<br />

which explained the observer’s surroundings:<br />

paradises, underworlds, islands, gods, monsters,<br />

abysses..., all of which revealed the course<br />

of the rivers, the day and night cycle, the relationship<br />

with nature, and its origin and destiny.<br />

The observer had completed his picture of the<br />

world: to each element of his surroundings he<br />

had attached an endless list of names, of nonexistent<br />

places which eventually defined his<br />

beliefs, his customs and his relationship with<br />

the world.<br />

II. This tale, about how a random observer built<br />

his own map of the world, conceals a pattern<br />

that could be very useful to us in our attempt<br />

to understand the role played by cartographic<br />

productions today. It is a very simple pattern<br />

which has existed since the early days of cartography,<br />

and which is connected to the fact<br />

of inhabiting a sphere, and the impossibility<br />

of obtaining a total and direct view of our<br />

world. Undoubtedly, the fact that our observer<br />

lived on a curved surface prevented him from<br />

obtaining a complete view of his world; its<br />

spherical nature made it impossible to grasp.<br />

To overcome this difficulty, and, in the face of<br />

a need for a total view which could explain the<br />

workings of his surroundings, of the universe,<br />

ultimately, the observer had to build the image<br />

which lay beyond the horizon, the first frontier.<br />

To observe his surroundings, to build the outside<br />

world: here lie the foundations of any map,<br />

its core, its ultimate raison d’être.<br />

III. It could be said that the task of representing<br />

space is as old as the task of imagining<br />

it. In other words, maps are as old as Utopias.<br />

The first man to draw his village was displaying<br />

Utopian behaviour: in his mind countless<br />

names that pointed at the existence of imaginary<br />

places lay in slumber. As he drew fragile<br />

diagrams of his village’s walls, of its rivers and<br />

fields, the world was filled with names which<br />

heralded places of light and shadow. These<br />

names soon went beyond language to the map,<br />

becoming essential pieces in the creation of<br />

an imago mundi. Utopia, that building of the<br />

cartographic outside, is as much a part of the<br />

earth as the land and the sea. Let us briefly remember<br />

what Plato told us about Atlantis: “But<br />

afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes<br />

and floods; and in a single day and night of<br />

misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank<br />

into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like<br />

manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.<br />

For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable<br />

and impenetrable, because there is a<br />

shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused<br />

by the subsidence of the island” (Timaeus 24c-<br />

25a). The world is built on Utopias, which sink,<br />

leaving limestone beds, the geological trace of<br />

an inexistent place.<br />

“To observe his<br />

surroundings, to build<br />

the outsider world: here<br />

lie the foundations of<br />

any map, its core, its<br />

ultimate raison d’être”<br />

IV. In this sense, the building of the outside<br />

completely transforms the nature of cartographical<br />

production. In this pattern of pro-<br />

cess, the instruments needed for the creation of<br />

a view of the world do not coincide with those<br />

used to represent our surroundings. The scale,<br />

the calculations, the triangle and the quadrant<br />

are overshadowed by names of inexistent<br />

places, by shoreless seas, by prodigious beings<br />

and objects … even by a projection of ourselves.<br />

These elements, as representative of Utopia<br />

as of cartography, render the map a project on<br />

the world. It is no longer a case of faithfully<br />

representing a territory, but of thinking about<br />

what we want it be like. In the map, science and<br />

literature, observation and imagination, come<br />

together; it pools together a range of procedures<br />

that lead it toward a desire to complete<br />

the great mosaic of the world, of understanding<br />

our forms of life, of learning how to relate with<br />

the otherness of our surroundings. In a map,<br />

representation turns into project; it goes beyond<br />

the object and sinks into the immensity of<br />

the surface of the earth, into the endless curve<br />

of the horizon, into our inexhaustible dreams.<br />

Returning again to the words of C. Jacob, the<br />

necessary condition for the birth of cartography<br />

was not so much the certainty of its materiality,<br />

but the certainty of the possibility of its<br />

materialisation. Maps emerged as a project, as<br />

the natural place for Utopias, as these only exist<br />

in their representation.<br />

V. We could think that, nowadays, these stories<br />

have been rendered obsolete by a cartographic<br />

desire which aims for objectivity, precision and<br />

neutrality; or that there is no space left for Utopias<br />

in this world, as there is no corner of the<br />

Earth which has not been discovered, classified<br />

and exploited. We live in a known world; we<br />

have dotted the sky with electronic eyes that<br />

scrutinise the land, locating us, rendering the<br />

representation of the world an aseptic, almost<br />

functional, task. Now that we know everything,<br />

and that we can travel easily and comfortably<br />

all over the world, it would seem that maps<br />

have lost their Utopian component, giving<br />

themselves over entirely to a logic of objectivity;<br />

that maps only serve to show us the way, to<br />

furnish us with safe directions from one place<br />

to another, to find a street, a shop or a hospital.<br />

“Maps are the reflection<br />

of the culture which<br />

produces them, and<br />

show, even in their<br />

blank spaces, in their<br />

silences, the various<br />

projects of each time”<br />

However, it is not precisely our time’s excess<br />

of precision and objectivity that demands a<br />

return to the early days of cartography, to our<br />

observer, to the time when little or nothing was<br />

known to the Utopian moment when the world<br />

was constructed. As John B. Harley pointed<br />

out, cartography is rarely what cartographers<br />

say it is. Maps are not precise and neutral objectives:<br />

they hide intellectual and imaginary<br />

powers which lend them the status of valuable<br />

cultural products. Maps are the reflection of<br />

the culture which produces them, and show,<br />

even in their blank spaces, in their silences, the<br />

various projects of each time. Today, we find<br />

ourselves facing a pressing need to create new<br />

projects about the world, new representations<br />

which reflect the fractures of our supposedly<br />

homogeneous world. In this sense, maps will<br />

continue to be the best place for our Utopias.<br />

20 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 21

22 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 23

Cartografías de la realidad<br />

Mirada, fotografía y mapa<br />

Pedro Medina<br />

“El mapa es abierto, es conectable en todas sus dimensiones,<br />

desmontable, reversible, susceptible de recibir constantemente<br />

modificaciones […] Haced mapas y no fotos ni dibujos”<br />

(Gilles Deleuze y Felix Guattari, Rizoma)<br />

Objetividad y representación<br />

Realizar un mapa no ha sido históricamente<br />

una tarea neutra, siempre conlleva una mirada.<br />

Todo mapa ha surgido como consecuencia<br />

de una determinada ideología o bajo criterios<br />

con frecuencia arbitrarios que condicionan<br />

las formas de representar el mundo.<br />

En esta ocasión, el diseño de una cartografía<br />

se liga a un medio: la fotografía, tan subjetiva<br />

como cualquier otro lenguaje artístico, pero<br />

que popularmente se identifica con un medio<br />

que documenta el mundo como mayor objetividad<br />

que otros. Al hacerlo, pronto surge la<br />

tradicional cuestión de fondo sobre la relación<br />

entre objetividad y realidad.<br />

Estas consideraciones aún lastran diagnósticos<br />

sobre un lenguaje que era emergente,<br />

como aquellos maravillosos textos de Walter<br />

Benjamin en los que reflexionaba sobre cómo<br />

duplicar el mundo, retratándolo con mayor<br />

fidedignidad. Benjamin llegó a hablar de un<br />

“museo imaginario” basado en la afirmación<br />

de Godard a propósito de Le Carabiniers: “coleccionar<br />

fotografías es coleccionar el mundo”.<br />

Sin embargo, los nuevos comportamientos<br />

artísticos han transformado esta función, pasando<br />

a reflejar irónicamente el mundo o a<br />

constatar “la irrealidad de la realidad” –como<br />

afirmaba Kate Linker–. Obviamente, estas nuevas<br />

prácticas encuentran cabida en evidentes<br />

revisiones del problema de la representación.<br />

Un muy breve balance de lo ocurrido desde el<br />

asentamiento de la fotografía dentro del sistema<br />

del arte a mediados de los ochenta, destaca<br />

principalmente la reivindicación “artística” de<br />

la fotografía documental y el asentimiento<br />

de lo que podría denominarse “nuevos comportamientos<br />

fotográficos”, procedentes de<br />

prácticas artísticas alejadas del uso purista del<br />

medio en las vanguardias artísticas –como es<br />

el caso de Man Ray–, pero sobre todo en aquellas<br />

manifestaciones conceptuales de los años<br />

sesenta, que suponían un paso más dentro de<br />

esa polémica en torno al estatuto artístico de la<br />

fotografía latente prácticamente desde sus orígenes,<br />

debido a su carácter no aurático, derivado<br />

de su reproductibilidad, y de esa supuesta<br />

objetividad mayor que otros medios privilegiados<br />

todavía por creencias de tipo romántico.<br />

Su uso documental para registrar obras de<br />

arte efímeras, junto con las expresiones<br />

conceptuales, transformó a la fotografía en<br />

un medio para la experimentación que daba<br />

lugar a nuevas formas y prácticas, así como<br />

a una reflexión sobre la misma fotografía y<br />

su rol respecto a la sociedad y el arte, convirtiéndose<br />

en el camino para alzar la idea a<br />

la categoría de objeto, al tiempo que el lugar<br />

idóneo para prácticas escenográficas nuevas,<br />

aunque su principal papel seguía siendo<br />

como medio.<br />

Pero dejando de lado la relevante aparición<br />

de una “nueva forma artística”, que procede<br />

de la crisis de los géneros artísticos tradicionales,<br />

y que encuentra precisamente en la<br />

fotografía un campo idóneo para desarrollar<br />

las potencialidades icónicas de la imagen, en<br />

el contexto de esta exposición se privilegia<br />

su dimensión como documento o archivo de<br />

la realidad.<br />

La propuesta de <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> enlazaría<br />

con posturas que fomentan la procesualidad<br />

misma, como fenómeno de representación<br />

y como constancia de aquellas manifesta-<br />

26 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 27

ciones de carácter temporal condenadas a<br />

desaparecer o que se conciben precisamente<br />

en su estar in progress. Es, pues, el lenguaje<br />

fundamental y el instrumento que constata<br />

lo ocurrido.<br />

A la consustancial reproducción mecánica<br />

implícita en el propio concepto de fotografía,<br />

lo que facilita la recepción masiva de la<br />

obra y la democratización de su producción,<br />

ahora aparece la posibilidad de la utilización<br />

de nuevos medios, más proclives a la interacción<br />

y la creación de piezas colectivas, donde<br />

la participación se vuelve algo natural en esa<br />

transformación del espectador en usuario, lo<br />

que aporta un enriquecedor poliperspectivismo.<br />

De esta forma, esa característica de imagen<br />

multiplicable adquiere ahora una dimensión<br />

mayor, al mismo tiempo que se potencia<br />

una relación de pertenencia con la obra que<br />

tiene más que ver con la colaboración en el<br />

proceso y la emoción activada en el mismo<br />

que con la posesión física de la obra.<br />

Por otro lado, nos encontramos con el mapa<br />

como un formato que también se percibe<br />

ingenuamente como algo objetivo, pero que<br />

–como aparece al inicio de este texto y sobre<br />

todo en ¿Para qué un mapa? de Pablo Jarauta–<br />

conviene observar como otro medio más<br />

para contar una historia y hacer evidentes<br />

formas de ver el mundo.<br />

Al margen del relato construido por Pablo<br />

Jarauta, quisiera aportar un par de notas,<br />

sobre todo para establecer su relación con<br />

el ámbito de la ciudad, un contexto en el<br />

que se generan relaciones y donde se acumulan<br />

formas de habitar, pero que indudablemente<br />

hoy debe ampliarse más allá del<br />

propio espacio físico. Ante este hecho, cabe<br />

preguntarse ¿cómo representar entonces<br />

esta realidad?<br />

“Realizar un mapa no<br />

ha sido históricamente<br />

una tarea neutra,<br />

siempre conlleva una<br />

mirada. Todo mapa<br />

ha surgido como<br />

consecuencia de una<br />

determinada ideología<br />

o bajo criterios con<br />

frecuencia arbitrarios<br />

que condicionan las<br />

formas de representar<br />

el mundo”<br />

Jean Baudrillard parte precisamente de<br />

la cartografía como paradigma de una referencialidad<br />

perdida, llegando incluso a<br />

afirmar en Cultura y simulacro que “el territorio<br />

ya no precede al mapa ni le sobrevive.<br />

En adelante será el mapa el que preceda al<br />

territorio –precisión de los simulacros– y el<br />

que lo engendre”.<br />

Al respecto, conviene recordar las matizaciones<br />

que realizaba André Corboz en El territorio<br />

como palimpsesto, al comparar dos<br />

maneras de relacionarse con el territorio (la<br />

contemplación del paisaje y el mapa): “El<br />

mapa se diferencia del territorio precisamente<br />

a través de actos de selección. Como práctica<br />

creativa el mapa no reproduce sino que<br />

descubre realidades previamente invisibles<br />

o inimaginables […] La construcción de los<br />

mapas desata potencialidades, rehace el territorio<br />

una y otra vez, cada vez con nuevas y<br />

diferentes consecuencias”.<br />

¿Y cómo se produce esto hoy día? Quizás con<br />

los nuevos medios se pueda dar esa feliz coincidencia<br />

de mapa e imperio –diría Borges<br />

en el famoso relato sobre el Arte de la Cartografía–,<br />

de georrepresentación y cosmovisión<br />

podríamos decir nosotros.<br />

Esta situación debería llevarnos a un posicionamiento<br />

que impida que sucumbamos a la<br />

fascinación por la forma expresiva, estableciendo<br />

un mínimo análisis sobre el mundo en<br />

el que vivimos para preguntarnos ¿por qué<br />

acudimos a este tipo de representación?, ¿es<br />

pertinente para poder hablar sobre la experiencia<br />

de nuestra época? Parece coherente<br />

con los tiempos que corren alejarse de posturas<br />

que adopten el autoritarismo que profesa<br />

quien cree en una verdad y pensar más bien<br />

en un mundo lábil, donde todo se vuelve posibilidad<br />

y no necesidad.<br />

A pie de calle, enseguida aparecen términos<br />

coincidentes como “global, tecnificado, acelerado,<br />

injusto, en el que nada permanece, sin<br />

valores…”, aunque se puede resumir como un<br />

mundo marcado por la comunicación planetaria,<br />

más que sin valores, en construcción<br />

hacia otros nuevos (sostenibilidad, igualdad<br />

de géneros y razas…) y, sobre todo, un mundo<br />

que ha devenido moda, es decir, donde ni<br />

convicciones, ni instituciones, ni productos<br />

están dados de una vez para siempre, siendo<br />

el reino de lo efímero.<br />

Este primer acercamiento al universo que nos<br />

rodea no tiene valor de prueba, por no ser una<br />

muestra suficientemente contrastada, no obstante,<br />

sí parece coincidir con buena parte de<br />

reconocidos diagnósticos de nuestra época.<br />

Remontándonos un poco en el tiempo, podríamos<br />

hablar de la sentencia de Nietzsche<br />

en su paradigmático Der Fall Wagner, donde<br />

toda décadence literaria está caracterizada<br />

por una condición: “la vida ya no habita en el<br />

todo”. Extraemos de Nietzsche y de todos sus<br />

epígonos que la realidad se vuelve fragmentaria,<br />

constatando que no hay un valor central<br />

en la época que le dé sentido, como ocurría,<br />

por ejemplo, en la Edad Media, donde el dios<br />

cristiano era medida de todas las cosas y el<br />

gótico o el románico eran las formas que hacían<br />

visible una relación homogénea y unívoca<br />

con el mundo.<br />

“La propuesta de<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

enlazaría con posturas<br />

que fomentan la<br />

procesualidad misma,<br />

como fenómeno<br />

de representación y<br />

como constancia de<br />

aquellas manifestaciones<br />

de carácter temporal<br />

condenadas a<br />

desaparecer”<br />

Por otro lado, partiendo del análisis de la ciudad<br />

como la gran forma de rastrear la vida<br />

–en la línea de Georg Simmel–, destaca un<br />

autor como Marshall Berman, quien constata<br />

que “todo lo sólido se desvanece en el aire”;<br />

por tanto, no hay certezas ni puntos de refe-<br />

28 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 29

encia a los que poder aferrarnos con seguridad.<br />

La vida así ha ganado en incertidumbre,<br />

pero también en posibilidad.<br />

“Hay que desentrañar<br />

una maraña confusa<br />

de hechos cuya<br />

complejidad creciente<br />

reclama diversos relatos<br />

que hagan visibles las<br />

rápidas metamorfosis<br />

de nuestro tiempo”<br />

Pero para no extendernos en este punto, concluiré<br />

con la sentencia de Zygmunt Bauman,<br />

quien ha enunciado, con extraordinaria fortuna<br />

mediática, que habitamos en un mundo<br />

caracterizado por una “modernidad líquida”.<br />

A través de varios textos ha definido el espacio<br />

actual como una “sociedad de la incertidumbre”,<br />

donde todo es “líquido”, inconsistente,<br />

evanescente, no hay tiempo ya para<br />

que unas condiciones de vida y de acción<br />

lleguen a convertirse en costumbre, siendo<br />

la precariedad el signo de nuestro tiempo.<br />

Y ante esta realidad, Bauman aboga por un<br />

espacio público global, donde se realice un<br />

análisis general de los problemas a escala<br />

mundial y donde se haga presente una responsabilidad<br />

planetaria.<br />

La reconstrucción de esta historia permite<br />

repensar algunos conceptos y uno que se<br />

vuelve necesario en este contexto es el de<br />

“habitar”, entendiendo por el mismo las condiciones<br />

en las que se desarrolla la vida cotidiana<br />

y la acción colectiva construida simultáneamente<br />

por distintos ciudadanos. Ya no<br />

es posible un habitar armonioso, pero quizás<br />

en la confluencia de puntos de vista se pueda<br />

encontrar un nuevo atractivo en el mundo<br />

gracias a la curiosidad.<br />

Éste es el panorama y, por tanto, habrá que<br />

atender al sistema de formas que determinan<br />

el proyecto para averiguar el conjunto de<br />

ideas al que atañen, estudiando si lenguaje y<br />

época se corresponden al ofrecer aquello que<br />

debería ser su última finalidad: proporcionar<br />

un espacio que habitar.<br />

De vuelta una vez más sobre el lenguaje, podríamos<br />

acudir a un término que recientemente<br />

utilizó Juan A. Álvarez Reyes para una<br />

exposición sobre animación contemporánea.<br />

Se trata de “fantasmagoría”, que no solo es<br />

el título de la primera pieza de animación<br />

de la historia del cine, realizada en 1908 por<br />

Emil Cohl, probablemente inspirado por el<br />

fantasmagore Étienne Gaspar Robertson. La<br />

ilusión óptica avanzaba como espectáculo en<br />

un París cuyo origen moderno describió Benjamin<br />

a través de las sugerentes luces de la<br />

metrópoli, sus pasajes, los flâneurs, la prensa,<br />

la aparición de la fotografía… es decir, “fantasmagorías”<br />

–como las denominó Benjamin–<br />

que servían para sintetizar los imaginarios de<br />

la segunda mitad del siglo xix.<br />

Igual que entonces, ahora hay que desentrañar<br />

una maraña confusa de hechos cuya complejidad<br />

creciente reclama diversos relatos<br />

que hagan visibles las rápidas metamorfosis<br />

de nuestro tiempo. De esta forma, podríamos<br />

considerar la imagen (fotográfica) definida<br />

no por su permanencia sino por su condición<br />

de elemento en continua transformación, teniendo<br />

muy en cuenta la superposición de<br />

planos y miradas, para preguntarnos si de<br />

esta forma es capaz de configurar un paisaje<br />

diferente de nuestro entorno.<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

¿Qué significa, pues, representar hoy el<br />

mundo? <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> se concibió con<br />

la intención de crear una nueva manera de<br />

generar un mapa, donde lo participativo se<br />

alza sobre lo impuesto como supuestamente<br />

objetivo, entendiendo la fotografía como<br />

un medio privilegiado y democrático para<br />

acercarnos a nuestra realidad. Además, cobra<br />

también relevancia cierta idea de deriva,<br />

como concepto de transición entre la geografía<br />

física de la urbe y una topología interior<br />

e intersubjetiva, con el fin de hacer posibles<br />

nuevos espacios creativos.<br />

La idea original y desarrollo se debe a Javier<br />

Maseda, quien propuso un proyecto que<br />

consistía en construir el mapa de PHotoEspaña y<br />

de <strong>Madrid</strong> a través de la colaboración ciudadana<br />

en una web bajo el lema “Danos tu visión de<br />

PHotoEspaña <strong>2009</strong>”, reflexionando así sobre<br />

el evento y la ciudad que acogen la exposición.<br />

De esta forma, en www.mappingmadrid.com,<br />

web desarrollada por Blogestudio, se empieza<br />

a construir un escenario colectivo e in progress<br />

con las imágenes tomadas por cualquier<br />

persona, debiendo estar todas geolocalizadas,<br />

es decir, el usuario que participa en la web sube<br />

su fotografía y la dirección del lugar en el que<br />

ha sido tomada.<br />

El resultado es una cartografía visible online<br />

en la que se pueden apreciar distintos puntos<br />

de vista sobre un mismo espacio, convirtiendo<br />

<strong>Madrid</strong> en un collage de imágenes y acciones.<br />

Pero lo principal es la relación entre mirada<br />

y lugar fotografiado, construida a través<br />

de un proyecto que destaca por su carácter<br />

participativo y, por tanto, por una autoría que<br />

finalmente es colectiva.<br />

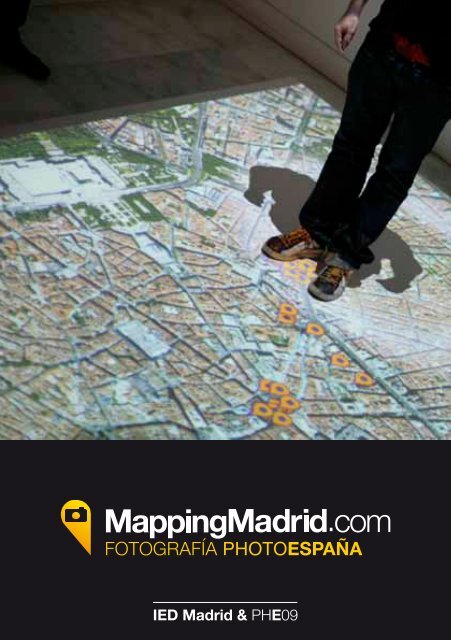

El siguiente paso era convertir esta web en<br />

una instalación en el Palacio de Altamira, estableciéndose<br />

como premisa que el visitante<br />

se sintiera parte de la obra y no un mero<br />

espectador de la misma. La instalación, realizada<br />

junto a Jarl Einar Ottestad y Anders<br />

Restad, consiste en una proyección cenital<br />

de la ciudad de <strong>Madrid</strong> sobre la que aparecen<br />

indicadores con los lugares que han sido fotografiados.<br />

El visitante interactúa con esta proyección<br />

convertido en un ratón de ordenador<br />

humano, que activa el mapa de <strong>Madrid</strong> para<br />

adentrarse en el mismo y acercarse entonces<br />

a las fotografías presentes en la web. De esta<br />

manera, el espectador no siente que esté frente<br />

a la exposición, como si le fuera ajena, sino<br />

dentro de la misma, continuando así el carácter<br />

participativo de la web.<br />

“<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

se concibió con la<br />

intención de crear<br />

una nueva manera de<br />

generar un mapa, donde<br />

lo participativo se<br />

alza sobre lo impuesto<br />

como supuestamente<br />

objetivo, entendiendo la<br />

fotografía como un medio<br />

privilegiado y democrático<br />

para acercarnos<br />

a nuestra realidad”<br />

30 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 31

Asimismo, la visualización de las piezas fotográficas<br />

sobre el mapa viene completada<br />

por otra proyección. En ella se pueden contemplar<br />

las fotos de forma más inmediata<br />

por medio de una galería en la que se potencia<br />

la percepción de “recorrido” a la hora<br />

de seleccionar las fotografías presentes en<br />

la web.<br />

El resultado es obvio: la propia dinámica expositiva<br />

genera la sensación de pertenencia<br />

a una obra colectiva en la que el espectadorusuario<br />

es quien la crea y la activa, construyendo<br />

un mapa personal y compartido en el<br />

que podemos contemplar distintas visiones<br />

de <strong>Madrid</strong> y de PHotoEspaña, por lo general<br />

alejadas de visiones más institucionalizadas,<br />

demostrando una frescura muy atractiva.<br />

“La propia dinámica<br />

expositiva genera la<br />

sensación de pertenencia<br />

a una obra colectiva en la<br />

que el espectador-usuario<br />

es quien la crea y la activa,<br />

construyendo un mapa<br />

personal y compartido<br />

en el que podemos<br />

contemplar distintas<br />

visiones de <strong>Madrid</strong> y<br />

de PHotoEspaña”<br />

De esta manera, se entrelazan conceptos<br />

como los de ciudad, cartografía y mirada, una<br />

percepción cuya importancia puede recorrerse<br />

en la historia, pero que sigue estando de<br />

gran actualidad, como demuestra buena parte<br />

de la producción teórica actual, desde las<br />

teorías comunicacionales en red de Manuel<br />

Castells a esa vuelta a lo ciudadano aunque<br />

entendido como ciberespacio, es decir, un ámbito<br />

metaurbano universalizado, tal y como lo<br />

postula Paul Virilio.<br />

Sobre esta unión de cartografía y representación<br />

física de la imagen generada por los<br />

usuarios-fotógrafos, vuelve a actuar el espectador-usuario,<br />

generando un flujo de ida y<br />

vuelta desde el que entender el funcionamiento<br />

de los nuevos medios unido a la percepción<br />

de un entorno que es nuestro, porque vivimos<br />

en él y también lo construimos.<br />

Algunas de estas consideraciones estaban<br />

presentes en el ciclo de conferencias celebrado<br />

el pasado mayo, poco antes de inaugurar<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong>, titulado La ciudad<br />

híbrida, que congregó a varios expertos,<br />

bajo la dirección de José Luis de Vicente,<br />

para reflexionar sobre “visualización urbana<br />

y mapeado colaborativo”. Como afirma J.L.<br />

de Vicente: “ha nacido la ciudad en tiempo<br />

real, donde los ciudadanos modifican sobre<br />

la marcha sus patrones de comportamiento,<br />

y la función y significado de los lugares se<br />

reconfigura constantemente”. Parece que<br />

estuviera hablando de la exposición de la<br />

que nos ocupamos, y es que algunos de los<br />

contenidos impartidos fueron precisamente:<br />

mapeado colaborativo (la ciudad subjetiva<br />

representada por sus ciudadanos) o<br />

gobernanza 2.0 (democracia participativa y<br />

tecnologías digitales).<br />

Sin duda, desde aquí podríamos sacar muchas<br />

derivas sobre los actuales sistemas políticos y<br />

la necesidad de participación ciudadana, desde<br />

las teorías de Toni Negri a otras centradas<br />

en aspectos de mercado de la obra de arte,<br />

como puede ser actualmente el grupo sueco<br />

Pirate Bay, pasando evidentemente por otras<br />

en las que se atienden las razones comunicativa<br />

y poiética del arte, cuyas referencias pueden<br />

ser nombres clásicos como Kant, Habermas o<br />

Danto y su concepto de “mundo del arte”.<br />

Pero más allá de esta dimensión orientada a la<br />

praxis, en <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> se da un paso más<br />

dentro del terreno de la representación y de la<br />

idea de construcción de un mapa. Ello se debe<br />

a la última parte de la exposición dentro del Gabinete<br />

de Exposiciones del Palacio de Altamira,<br />

que consiste en los tres fragmentos de la ciudad<br />

líquida de <strong>Madrid</strong> y la Transurbancia, realizadas<br />

por Tete Álvarez, un conjunto de fragmentos de<br />

ciudades con la capacidad de construir un nuevo<br />

relato sobre el mapa y la realidad global.<br />

“Densidad y fluidez<br />

hacen posible tomar<br />

el mapa como base<br />

cartográfica para<br />

iniciar una exploración<br />

de la ciudad, un<br />

itinerario en el que el<br />

ejercicio de perderse,<br />

la desorientación, sea<br />

una nueva forma de<br />

reencuentro ante<br />

lo desconocido”<br />

La vinculación entre lugar y fotografía es una<br />

constante en la obra de Tete Álvarez, como<br />

puede comprobarse en series como Confines<br />

o Desterritorios. En este caso, las piezas comprendidas<br />

bajo el título genérico de Ciudades<br />

líquidas. <strong>Madrid</strong> amplían el mapa a una<br />

dimensión que envuelve al espectador. Esta<br />

fragmentación y cambio de escala procede<br />

de un plano de <strong>Madrid</strong> de los años cincuenta;<br />

que puede contemplarse en su totalidad precisamente<br />

en la esquina superior izquierda de la<br />

Transurbancia presente en la misma sala.<br />

Lo primero que impresiona de estas obras es su<br />

majestuosidad que, no obstante, tiene algo de familiar.<br />

Los contornos de estos mapas son aún reconocibles<br />

y cubren las paredes como si fueran<br />

un antiguo tapiz que se ajusta perfectamente<br />

al espacio, pero que nos descubre otra realidad<br />

cuando nos acercamos a él: todos los elementos<br />

se vuelven líquidos; experiencia que incluso se<br />

asemeja a aquellas superficies de agua poco profundas<br />

que podemos ver en Google Earth.<br />

Empiezan a relacionarse entonces términos<br />

como mirada cenital, planimetría urbana,<br />

fragmento o labilidad, puesto que el punto de<br />

partida va a ser –igual que en la Transurbancia–,<br />

las imágenes satelitales y procesos que<br />

las transforman, en este caso en un líquido<br />

denso, que diluye ya no la foto sino el antiguo<br />

mapa del casco histórico de <strong>Madrid</strong>.<br />

Como cuenta Tete Álvarez: “Densidad y fluidez<br />

hacen posible tomar el mapa como base<br />

cartográfica para iniciar una exploración de la<br />

ciudad, un itinerario en el que el ejercicio de<br />

perderse, la desorientación, sea una nueva forma<br />

de reencuentro ante lo desconocido”. Pero,<br />

sin duda, esta metamorfosis del mapa en algo<br />

líquido enlaza directamente con diagnósticos<br />

sobre esta época, como aquella metáfora del<br />

mundo contemporáneo que ha popularizado<br />

Zygmunt Bauman, que ya comentábamos con<br />

anterioridad; estableciéndose esta relación no<br />

32 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 33

solo literalmente, sino sobre todo gracias a que<br />

comparten aquel sentimiento de incertidumbre<br />

y fugacidad que impera entre nosotros.<br />

Como confiesa Óscar Fernández: “La metáfora<br />

de lo líquido y del fluir define la experiencia<br />

urbana actual. Tanto es así que está minando<br />

todos los resortes de la ciudad, haciendo que<br />

la propia idea de urbe se desmorone y sea sustituida<br />

por núcleos de población más o menos<br />

informes. Lo más interesante de este proceso<br />

hacia lo líquido es que está afectando incluso<br />

a las viejas ciudades. Mientras la memoria de<br />

los lugares se fija cada vez más gracias al fenómeno<br />

turístico, la realidad de estos lugares<br />

se diluye cada vez más rápido. Resulta de ello<br />

una nueva forma de turismo-nostalgia que<br />

visita el recuerdo de lugares históricos. Solamente<br />

su recuerdo porque, en realidad, éstos<br />

nunca existieron o, como mucho, hace mucho<br />

tiempo que han dejado de ser lo que nos cuentan<br />

de ellos”.<br />

Ésta es una reflexión que se complementa perfectamente<br />

con la otra obra presente. Como<br />

decíamos, también reclama dos distancias o<br />

formas de acercamiento a la misma, activando<br />

cada una de ellas procesos de reconocimiento<br />

diferentes. En el caso de la Transurbancia, se<br />

hace más evidente aquel acercamiento cenital<br />

que entroncaría con sentencias como la de Michel<br />

de Certeau en La invención de lo cotidiano,<br />

según la cual la mirada ha dejado de ser humana<br />

para ser como el ojo de Dios que todo lo ve, ahora,<br />

situados en el piso 110 del World Trade Center,<br />

toda la ciudad se convierte en un panóptico.<br />

Esta mirada cenital es la que experimenta en<br />

primera persona el visitante a <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

en la primera instalación y que en la Transurbancia<br />

se convierte en un crisol de fotografías<br />

satelitales que configuran una imagen<br />

más compleja. Como explica Tete Álvarez: “La<br />

mirada cenital no es una mirada actuante en<br />

el espacio que intenta dominar, sino que se<br />

circunscribe a un ámbito simbólico. La “transurbancia”<br />

es el método que propone Stalker<br />

(colectivo de investigación urbana) para atravesar,<br />

recorrer y mapear los terrain vague”. Se<br />

trata de cartografiar una (otra) configuración<br />

urbana construida a partir de lo que Manuel<br />

Castells llama una nueva lógica espacial basada<br />

en flujos de información, frente a la lógica<br />

de la organización social arraigada en<br />

la historia de los lugares y territorios locales<br />

inmediatos. Otra cartografía que permita realizar<br />

una deriva, entendida como “técnica de<br />

paso ininterrumpido a través de ambientes<br />

diversos” y que gracias a los flujos nos desplace<br />

de un lugar a otro.<br />

En un mundo de homogeneización de comportamientos<br />

culturales y estructuras arquitectónicas,<br />

como plantea Marc Augé con sus<br />

“no-lugares” o Rem Koolhaas con su “ciudad<br />

genérica”, lo que queda es un interesante laboratorio<br />

donde no se desprecia el movimiento<br />

hacia la similitud a través de un tapiz de diferencias<br />

que pueda establecer una visión de<br />

conjunto sin perder una identidad que ahora<br />

cobra significado en su relación con las demás.<br />

Partiendo de este contexto, la propuesta de<br />

Tete Álvarez consiste en la visión que se construye<br />

a través de un cúmulo de superposiciones<br />

donde gráfica y fotografías satelitales de<br />

grandes ciudades del mundo se unen, siendo<br />

su eje el recorrido de los trenes de cercanías<br />

de <strong>Madrid</strong>. Este collage plantea dos visiones:<br />

una, primera, de conjunto, que nos permitiría<br />

ver la península de la India rodeada de agua,<br />

y otra, mucho más cercana, que desencadena<br />

procesos de identificación y nuevas formas de<br />

concepción de un espacio al aparecer ahora<br />

relacionado con otras realidades.<br />

Podemos reconocer las planimetrías regulares<br />

de metrópolis europeas junto a la trama<br />

urbana difusa de otras grandes ciudades “no<br />

racionalizadas” y entregadas a un tipo de<br />

extensión más natural y caótica. Distintas<br />

escalas y épocas se entrelazan, pudiendo reconocer<br />

El Vaticano, Caracas o <strong>Madrid</strong>, entre<br />

otros muchos lugares, pero cobra mayor significación<br />

en aquellos momentos en los que se<br />

cruzan elementos inesperados o con un aire<br />

de familia, como ocurre cuando coinciden un<br />

río y una autopista “reales” junto a la gráfica<br />

de los trenes de cercanías de <strong>Madrid</strong>.<br />

Como es obvio, la construcción de nuevas correspondencias<br />

y significados se multiplica<br />

a medida que nos sumergimos en la imagen,<br />

teniendo como principales protagonistas la<br />

India (como forma y por el mapa de ferrocarriles<br />

de la misma) y <strong>Madrid</strong> (presente como<br />

plano histórico, en fotos satelitales y con el<br />

protagonismo de la red de sus trenes de cercanías),<br />

pero esencialmente lo que surge en esta<br />

confluencia de flujos y espacios es la metáfora<br />

del viaje como gran imagen.<br />

Parece coherente, al considerar la realidad<br />

como algo fugaz y “en tránsito”. Aparece una<br />

vez más una forma de representar acorde con<br />

el análisis que hicimos de las características<br />

esenciales del momento actual, un universo<br />

que está redefiniendo continuamente las relaciones<br />

entre colectivos e identidades, para<br />

establecer un foro donde experimentar estas<br />

transformaciones y discutir sobre las mismas<br />

desde diversos puntos de vista.<br />

Esto abre las posibilidades de lo que se podría<br />

denominar “estéticas migratorias” o<br />

centradas en la idea de viaje, precisamente<br />

porque el hombre contemporáneo es viajero<br />

por antonomasia, un sujeto desarraigado, sin<br />

destino, condenado a vagabundear sin cesar<br />

en busca de unas certezas que este mundo<br />

no le puede dar. Quizás solamente nos queda<br />

asumir el tránsito que aporta imprevisibilidad,<br />

la dispersión de los caminos, la asimetría<br />

de todos los recorridos y el mestizaje de<br />

costumbres y lenguajes.<br />

En conjunto esperamos que <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

haya colaborado a reflexionar sobre el lenguaje<br />

elegido para narrar esta realidad, descubriendo<br />

que todas estas representaciones<br />

hacen evidente la riqueza que albergan muchos<br />

fragmentos de subjetividad, ofreciendo<br />

una breve muestra de cómo la idea de mapa<br />

puede redefinirse a través de nuevos medios y<br />

acciones colaborativas.<br />

Se ha apostado, pues, por la imagen electrónica<br />

como el medio capaz de reflejar la<br />

fugacidad de este momento, aprehendiendo<br />

por un instante el discurrir indefinido de la<br />

vida y el naufragio de un sujeto que busca<br />

un discurso que plasme la experiencia de un<br />

universo que ya no es refugio. La metáfora<br />

del viaje se torna entonces un mecanismo<br />

idóneo con el que percibir la experiencia<br />

contemporánea, y esta exposición vuelve<br />

a ella para reposar por un momento en un<br />

lugar: <strong>Madrid</strong>, en el que permanecer bajo su<br />

condición de obra abierta, susceptible a más<br />

miradas e interpretaciones.<br />

34 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 35

Cartographies of Reality<br />

Gaze, Photography and Map<br />

Pedro Medina<br />

“The map is open; it is connectable in all of its dimensions; it is<br />

detachable, reversible, and susceptible to constant modifications […]<br />

make maps, not photographs and drawings”<br />

(Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Rhizome)<br />

Objectivity and Representation<br />

Historically, producing a map has not been<br />

a neutral task; it always entailed a gaze. All<br />

maps have emerged as a consequence of a<br />

certain ideology, or by following often arbitrary<br />

criteria, which condition the means of<br />

representing the world.<br />

On this occasion, the design of a map is<br />

linked to a specific medium: photography.<br />

This format is as subjective as any other artistic<br />

language, but has generally been seen as<br />

a medium capable of documenting the world<br />

with greater objectivity than others. In doing<br />

so, it is never long before we come up against<br />

the eternal background issue regarding the<br />

relationship between objectivity and reality.<br />

These considerations are still weighed down<br />

with diagnoses on a language which was still<br />

emerging, as could be seen in those wonderful<br />

texts by Walter Benjamin in which he reflected<br />

on a way to duplicate the world, in order<br />

to portray it more accurately. Benjamin went<br />

as far as speaking of an “imaginary museum”,<br />

based on Godard’s claim regarding Le Carabiniers:<br />

“collecting photographs is to collect the<br />

world”. However, new artistic behaviours have<br />

transformed this role, and have moved on to<br />

presenting an ironic view of the world, or on to<br />

establishing “the irreality of reality” –in words<br />

of Kate Linker. Obviously, these new practices<br />

are reflected in the clear revisions to the theme<br />

of representation.<br />

A very brief outline of what has happened<br />

since photography became an established discipline<br />

within the art system, in the mid-1980s,<br />

reveals, mainly, the “artistic” reividincation of<br />

documentary photography and the consolidation<br />

of what could be defined as “new photographic<br />

behaviours”, originating from artistic<br />

practices which had little to do with the purist<br />

use of the medium in artistic Avant-Garde<br />

trends –as is the case of Man Ray-, and, more<br />

strikingly, in the conceptual expression of<br />

the 1960s. These disciplines took the controversy<br />

regarding photography’s art status to<br />

another level, which had been undermining<br />

the medium almost since its origins, given its<br />

non-auratic nature, its susceptibility to reproduction<br />

and its alleged greater objectivity in<br />

comparison with other media which still enjoy<br />

the advantages of the romantic notions that<br />

surround them.<br />

Its documentary role in capturing ephemeral<br />

works of art, along with conceptual expression,<br />

transformed photography into a medium<br />

for experimentation, giving rise to new<br />

forms and practices, as well as the ability to<br />

reflect upon itself; it also has a role pertaining<br />

to society and art, paving the way to grant<br />

ideas the status of objects, at the same time as<br />

it became the ideal setting for new scenographies,<br />

although its main function continued to<br />

be as a medium.<br />

However, leaving aside the relevant emergence<br />

of a “new art form”, which had its origins in the<br />

crisis suffered by traditional art genres, revealing<br />

photography to be an ideal field for the development<br />

of the iconic potential of the image,<br />

in this exhibition it is its dimension as document<br />

or archive of reality that is most examined.<br />

The proposal contained in <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

is linked to positions which encourage<br />

36 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 37

processuality itself, as a representation phenomenon<br />

and as proof of those temporary expressions<br />

which are doomed to disappear, or<br />

which have actually been conceived as being<br />

in progress. It is, therefore, the essential language,<br />

and the instrument which documents<br />

what has taken place.<br />

In addition to the mechanical reproduction<br />

that is inherent to photography, and which<br />

facilitates mass reception of the work and the<br />

democratisation of its production, we are now<br />

seeing new media that are better suited to interaction<br />

and to the creation of group pieces,<br />

in which participation is the most natural element<br />

in our transformation from viewers into<br />

users, which lends the process an enriching<br />

sense of polyperspectivism. In this way, the<br />

idea of reproducible images acquires a greater<br />

dimension, whilst, simultaneously, the sense<br />

of ownership toward the work is increased in<br />

a way which has more to do with taking part in<br />

the process and the emotion it activates, than<br />

with the physical possession of the work.<br />

On the other hand, we find that the map is another<br />

format which is seen, naively, as something<br />

objective, but which –as is stated at the<br />

beginning of this text, and, above all, in Pablo<br />

Jarauta’s Why a Map?– it is worth observing as<br />

just another way of telling a story and revealing<br />

different views of the world.<br />

Leaving aside the Pablo Jarauta’s narrative,<br />

I would like to contribute a couple of notes,<br />

mainly to establish the map’s connection with<br />

the realm of the city, a context where relationships<br />

are constructed and where ways of living<br />

are accumulated, but which today must, without<br />

a doubt, expand beyond the physical space<br />

itself. In the face of this, one could wonder how<br />

are we, then, to represent this reality?<br />

“Historically, producing<br />

a map has not been a<br />

neutral task; it always<br />

entailed a gaze. All<br />

maps have emerged<br />

as a consequence of<br />

a certain ideology, or<br />

by following often<br />

arbitrary criteria,which<br />

condition the means of<br />

representing the world”<br />

Jean Baudrillard took cartography as his starting<br />

point, seeing it as a paradigm of lost referentiality,<br />

even going as far as to claim, in Culture<br />

and Simulacrum, that “territory no longer<br />

precedes, nor survives, the map. Henceforth<br />

it will be the map that precedes territory –the<br />

precision of simulacra– and that engenders it”.<br />

In this respect, it is worth remembering the<br />

clarifications made by André Corboz in The<br />

Territory as Palimpsest when he compared<br />

two ways of relating to territory (the contemplation<br />

of landscape and the map): “The map<br />

is differentiated from the territory precisely by<br />

means of acts of selection. As a creative practice<br />

the map does not reproduce, and instead<br />

discovers realities which were previously invisible<br />

or unimaginable […] The construction<br />

of maps unleashes potentials; it rebuilds the<br />

territory again and again, with new and different<br />

consequences each time”.<br />

And how is this produced today? Perhaps the<br />

new media will make it possible to arrive at<br />

that happy coincidence of map and empire –as<br />

Borges said in his famous story on the Art of<br />

Cartography– and, as we could say, of geo-representation<br />

and cosmovision.<br />

This situation should lead us to a position<br />

which prevents us from succumbing to the<br />

fascination for the expressive form, establishing<br />

a minimum analysis on the world in<br />

which we live, in order to ask ourselves why<br />

did we resort to this sort of representation?<br />

Is it necessary in order to speak about the<br />

experience of our time? It would seem consistent<br />

with the times we live in to distance<br />

ourselves from attitudes which adopt the authoritarianism<br />

professed by those who believe<br />

in a single truth, and instead think about a<br />

fluid world, where everything becomes possibility<br />

instead of necessity.<br />

It was not long before words such as “global,<br />

technified, accelerated, unjust, where nothing<br />

stays the same, lacking in values”, etc. entered<br />

everyday language, although they can be summarised<br />

by the idea of a world defined through<br />

planetary communication which, rather than<br />

lacking values, is building new ones (sustainability,<br />

equality between the sexes and the races,<br />

etc.), and, above all, a world which has been<br />

taken over by trends, i.e., where no conviction,<br />

institution or product can be around forever,<br />

in what is a sort of kingdom of the ephemeral.<br />

This first view of the universe around us does<br />

not have any value as proof, as it is not sufficiently<br />

measured against any other evidence,<br />

but it does seem to coincide with a great many<br />

of the accepted diagnoses of our era. If we go<br />

back in time, we could speak of Nietzsche’s<br />

statement in his paradigmatic Der Fall Wagner,<br />

where all literary décadence is characterised<br />

by the condition: “life no longer inhabits<br />

the whole”. Thanks to Nietzsche and all his<br />

epigones, we realise that reality has become<br />

fragmented, that there is no central value<br />

which lends meaning to our era, as it did, for<br />

example, in the Middle Ages, where the Christian<br />

God was the measure for everything, and<br />

where Gothic and Romanic styles were the<br />

forms which lent visibility to a homogeneous<br />

and univocal relationship with the world.<br />

On the other hand, starting from the analysis<br />

of the city as the most important way of tracing<br />

life –according to Georg Simmel’s arguments–<br />

it is worth noting an author such as Marshall<br />

Berman who stated that “all that is solid melts<br />

into air”; therefore, there are no certainties<br />

or reference points which we can safely hold<br />

onto. Consequently, life has increased in uncertainty,<br />

but also in possibility.<br />

“The proposal contained<br />

in <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> is<br />

linked to positions which<br />

encourage processuality<br />

itself, as a representation<br />

phenomenon and as<br />

proof of those temporary<br />

expressions which are<br />

doomed to disappear”<br />

In order not to expand too much on this point,<br />

I will conclude with the words of Zygmunt<br />

38 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> · <strong>IED</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> & PHE09 39

Bauman, who stated, with excellent timing,<br />

that we inhabit a world defined by a “liquid<br />

modernity”. In his works he has labelled the<br />

current space a “society of uncertainty”, where<br />

everything is “liquid”, inconsistent, evanescent,<br />

and where there is no longer time for<br />

conditions of life and action to become established;<br />

precariousness, ultimately, is the sign<br />

of our time. In the face of this reality, Bauman<br />

advocates a global public space in which to<br />

analyse the problems that affect us all, driven<br />

by a sense of planetary responsibility.<br />

“We face the need to<br />

untangle the confusing<br />

mass of facts whose<br />

increasing complexity<br />

demands a range of<br />

narratives which will<br />

lend visibility to the<br />

swift metamorphoses<br />

of our time”<br />

The reconstruction of this history allows us to<br />

rethink a series of concepts, one of which, the<br />

notion of “inhabiting”, is particularly important<br />

in this context. It refers to the conditions<br />

in which daily life takes place, and to the collective<br />

action constructed simultaneously by a<br />

variety of citizens. It is no longer possible to<br />

aspire to harmonious inhabiting, but it is possible<br />

that the confluence of opinions will help<br />

us find a new desirability in the world, driven<br />

by curiosity.<br />

This is the present situation, and, therefore, it<br />

is necessary to deal with the network of forms<br />

that define the project, in order to discover the<br />

group of ideas to which they refer, determining<br />

whether or not language and era are matched<br />

with regards to what should be their ultimate<br />

purpose: to provide a space to be inhabited.<br />

Returning to language, we could resort to a<br />

term recently used by Juan A. Álvarez Reyes in<br />

reference to an exhibition on contemporary animation.<br />

The term is “phantasmagoria”, which<br />

was the title of the first piece of animation in<br />

the history of cinema, produced in 1908 by Emil<br />

Cohl –who was probably inspired by the fantasmagore<br />

Étienne Gaspar Robertson. Optical illusions<br />

had become a spectacle in a Paris whose<br />

modern origins were described by Benjamin<br />

through the suggestive lights of the metropolis,<br />

its landscapes, its flâneurs, the press, the advent<br />

of photography, etc. In other words, its “phantasmagoria”<br />

–as Benjamin called them–, which<br />

concentrated the collective imagination of the<br />

second half of the 19 th century.<br />

Now, the same as before, we face the need to<br />

untangle the confusing mass of facts whose<br />

increasing complexity demands a range of<br />

narratives which will lend visibility to the swift<br />

metamorphoses of our time. In this way, we<br />

could consider the (photographic) image to be<br />

defined not by its permanence but by its nature<br />

as an element undergoing constant transformation,<br />

keeping in mind the superposition of<br />

perspectives and approaches, in order to ask<br />

ourselves whether this medium is capable of<br />

configuring a different view of our surroundings.<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong><br />

What does it mean, then, to represent the<br />

world today? <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Madrid</strong> was conceived<br />

with the aim of finding a new way of creating<br />

a map, in which the action of the participants<br />

is more important than supposedly objective<br />

approaches, in an interpretation of photography<br />

as a privileged and democratic medium,<br />

capable of bringing us closer to our reality.<br />

In addition, the idea of being adrift becomes<br />

more relevant, as a concept for the transition<br />

between the physical geography of the city<br />

and an interior and inter-subjective topology,<br />