Il caso Jane Eyre - Università degli Studi di Teramo

Il caso Jane Eyre - Università degli Studi di Teramo

Il caso Jane Eyre - Università degli Studi di Teramo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

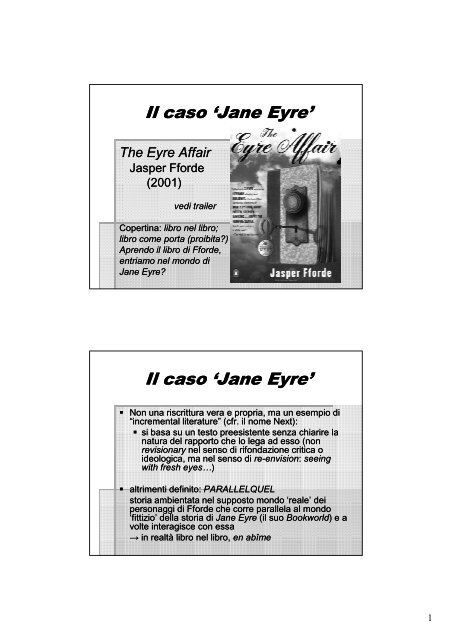

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

The <strong>Eyre</strong> Affair<br />

Jasper Fforde<br />

(2001)<br />

ve<strong>di</strong> trailer<br />

Copertina: libro nel libro;<br />

libro come porta (proibita?)<br />

Aprendo il libro <strong>di</strong> Fforde Fforde, ,<br />

entriamo nel mondo <strong>di</strong><br />

<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>?<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Non una riscrittura vera e propria, ma un esempio <strong>di</strong><br />

“incremental<br />

incremental literature literature” ” (cfr. il nome Next):<br />

si basa su un testo preesistente senza chiarire la<br />

natura del rapporto che lo lega ad esso (non<br />

revisionary nel senso <strong>di</strong> rifondazione critica o<br />

ideologica, ma nel senso <strong>di</strong> re-envision re envision: : seeing<br />

with fresh eyes… eyes…)<br />

altrimenti definito: PARALLELQUEL<br />

storia ambientata nel supposto mondo ‘reale’ dei<br />

personaggi <strong>di</strong> Fforde che corre parallela al mondo<br />

‘fittizio’ della storia <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> (il suo Bookworld Bookworld) ) e a<br />

volte interagisce con essa<br />

→ in realtà libro nel libro, en abîme<br />

1

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Perché <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>?<br />

“The most important thing about JE is that it is an<br />

excellent read, full of romance and fab characters and<br />

a burning buil<strong>di</strong>ng at the end […] The other point is<br />

that it is a very familiar piece of work - I think most<br />

people have a good idea that it is a romantic Victorian<br />

novel even if they haven't actually read it.<br />

It gave me problems too. I was stalled on the writing<br />

for about three years as I couldn't see how I could<br />

commit literary heresy and put words into <strong>Jane</strong>'s<br />

mouth. I got round the problem by skirting it<br />

completely, coward that I am - I think I gave her only<br />

two lines - and short ones at that!<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

"I used `<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>' not only because it's been a<br />

firm favourite of mine for a long time but because<br />

she is such a wonderful heroine, […] She broke<br />

the mould of female heroines.<br />

I of course imme<strong>di</strong>ately realized that this story<br />

couldn't exist in our world, so rather than change<br />

the plot to fit our world, I thought I would change<br />

the world to fit the plot plot." ." (da da un’intervista<br />

un’intervista)<br />

2

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Romanzo <strong>di</strong>stopico / utopico<br />

Distopia: un fantastico 1985 (un anno dopo il 1984 <strong>di</strong><br />

G. Orwell) in cui la guerra <strong>di</strong> Crimea è ancora in atto e<br />

la tentacolare Goliath Corporation domina il mondo<br />

Utopia: una società in cui la letteratura è un cult<br />

fandom fandom: : scambio <strong>di</strong> figurine; contrasti su paternità opere<br />

<strong>di</strong> Shakespeare; partecipazione accalorata a spettacoli<br />

<strong>di</strong> Shak.; il Will Will-Speak Speak; ; elenchi telefonici pieni <strong>di</strong><br />

omonimi <strong>di</strong> Milton e Tennyson Tennyson, , ecc.→ cultura alta è<br />

<strong>di</strong>ventata popular culture (cancellazione alto/basso)<br />

continui crimini contro <strong>di</strong> essa ( (fiction fiction infractions infractions: : furti <strong>di</strong><br />

manoscritti, falsificazioni, violazioni del <strong>di</strong>ritto d’autore,<br />

trasposizioni infedeli…) vengono commessi<br />

quoti<strong>di</strong>anamente.<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Romanzo postmoderno<br />

Mix <strong>di</strong> generi: sci-fi, sci fi, fantasy, detective story, horror,<br />

paro<strong>di</strong>a (scomparsa del confine alto/basso) [già <strong>Jane</strong><br />

<strong>Eyre</strong> era un mix]<br />

“I either either use ‘Swiss Army knife’ as a genre, you know, ‘The<br />

Swiss Army knife’ of books, fulfilling any need you can<br />

think of, or I call it deconstructional post post-modernism, modernism, which<br />

doesn’t mean anything at all but sounds vaguely<br />

academic. Or infernal nonsense” (cit. in Wells 2007: 199)<br />

Serialità: primo episo<strong>di</strong>o <strong>di</strong> una saga che vede<br />

protagonista la detective letteraria Thursday Next<br />

(next next = prossima puntata?)<br />

3

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Interme<strong>di</strong>alità<br />

Interme<strong>di</strong>alità: (testo ‘esteso’ e updated sul web)<br />

Contaminazione <strong>di</strong> co<strong>di</strong>ci; “ “Reme<strong>di</strong>ation<br />

Reme<strong>di</strong>ation” ” ( (Grusin Grusin-Bolter Bolter) ) /<br />

“Ra<strong>di</strong>ant Ra<strong>di</strong>ant textualities” (J. McGann)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Intertestualità: pastiche; citazioni; paro<strong>di</strong>a intramural<br />

(Linda Hutcheon Hutcheon, , 2000): in<strong>di</strong>rizzata ad altri testi o<br />

aspetti della letteratura per compiere operazione<br />

metaletteraria<br />

metaletteraria, , e quin<strong>di</strong>…<br />

Autoriflessività<br />

Autoriflessività: : riflessione sulla letteratura<br />

<strong>Il</strong> Caso <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> fa parte <strong>di</strong> quei romanzi che “generano<br />

riflessioni e riman<strong>di</strong> che non si esauriscono nel rapporto<br />

tra due testi, ma contengono sempre anche una<br />

riflessione sulla scrittura, sui suoi rapporti con la<br />

letteratura del passato passato, , sull’intreccio tra verità e finzione<br />

su cui si fonda la narrazione” (Splendore 1991: 61).<br />

4

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

<strong>Il</strong> romanzo…<br />

“[…] mentre guarda dentro l’opera e il tempo dell’autore<br />

evocato, guarda anche nel proprio tempo e con<strong>di</strong>zione<br />

<strong>di</strong> testo testo, , offrendo un <strong>di</strong>scorso allargato al genere e alle<br />

responsabilità del critico e dell’autore. <strong>Il</strong> centro vero <strong>di</strong><br />

questi romanzi è dunque la <strong>di</strong>scussione intorno alla<br />

letteratura letteratura, , o intorno alle varie fasi della costruzione<br />

letteraria, dal momento germinale della prima immagine<br />

nella mente dell’autore a quello della ricezione”. (Ibidem Ibidem)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>: : il ‘<strong>caso</strong>’ poliziesco <strong>di</strong>venta<br />

‘<strong>caso</strong> <strong>di</strong> indagine letteraria’<br />

2 sensi<br />

Indagine:<br />

1) Su ‘presunta’ minaccia alla<br />

letteratura rappresentata da<br />

me<strong>di</strong>a e mercato (paranoie<br />

riguardo a fine della letteratura<br />

e morte del libro): riflessione<br />

sullo statuto del letterario<br />

2) All’interno dei meccanismi del letterario (vera e<br />

propria auto auto-riflessività) riflessività)<br />

5

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

1) Riflessione sullo statuto del letterario:<br />

“Siamo nel 1985 1985: : quin<strong>di</strong>ci anni appena ci separano<br />

dall’inizio d’un nuovo millennio. Per ora non mi pare<br />

che l’approssimarsi <strong>di</strong> questa data risvegli alcuna<br />

emozione particolare. Comunque non sono qui per<br />

parlare <strong>di</strong> futurologia, ma <strong>di</strong> letteratura.”<br />

(Italo Calvino, Lezioni Americane. Sei proposte per il nuovo<br />

millennio millennio, , 1993 [1985])<br />

Dichiarazione <strong>di</strong> Calvino <strong>di</strong> volersi occupare dello<br />

‘stato’ della letteratura alle soglie del nuovo millennio:<br />

coincidenza?<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

<strong>Il</strong> romanzo riflette<br />

a) sul valore della letteratura classica quale parte <strong>di</strong><br />

patrimonio e memoria culturale in un mondo in<br />

cui:<br />

proliferano adattamenti, riscritture, rilavorazioni<br />

postmoderne <strong>di</strong> ogni tipo (copie/simulacri<br />

all’infinito)<br />

dominano altri me<strong>di</strong>a: metamorfosi e me<strong>di</strong>amorfosi<br />

del testo (ve<strong>di</strong> citazione*) citazione*<br />

sono <strong>di</strong>sponibili testi canonici in formato<br />

elettronico: il che consente <strong>di</strong> bypassare il<br />

problema della chiusura e unicità del testo a<br />

stampa e <strong>di</strong> scaricarlo, copiarlo, mo<strong>di</strong>ficarlo, farlo a<br />

pezzi → il portale della prosa come computer?<br />

(ve<strong>di</strong> citazione**)<br />

6

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

* “It is imperative that the groundwork is still taught in<br />

schools of course, but on the plus side we do have the<br />

“De Caprio Caprio” ” factor that will always bring a younger<br />

au<strong>di</strong>ence to Shakespeare; how many juveniles would<br />

have gone to see Baz Luhrman’s Romeo and Juliet<br />

without De Caprio in it, or (in another generation) Hamlet<br />

without Mel Gibson? New technology changes the way<br />

we do things but not who or what we are. Being told<br />

stories is one of Mankind’s most enduring fascinations<br />

and technology might change the ways in which we are<br />

told them (video, streamed images, etc.) but not the<br />

need need”. ”. (Fforde Fforde in White 2002)<br />

“[…] adaptations are a potential source of innovation and<br />

creativity because they transform – reproduce – they<br />

transmit in light of contemporary assumptions,<br />

circumstances, and ideologies” (Lanier Lanier 2002: 88)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

**“Certi ** “Certi personaggi sono <strong>di</strong>ventati in qualche modo<br />

collettivamente veri perché la comunità ha fatto su <strong>di</strong><br />

essi, nel corso dei secoli o <strong>degli</strong> anni, <strong>degli</strong> investimenti<br />

passionali. Ma, qualcuno oggi ci <strong>di</strong>ce, anche i personaggi<br />

letterari rischiano <strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong>ventare evanescenti, mobili,<br />

incostanti, e <strong>di</strong> perdere quella loro fissità che ci imponeva<br />

<strong>di</strong> non negarne i destini. Siamo entrati nell’ nell’era era<br />

dell’ipertesto […] Su Internet trovate programmi con cui<br />

potete scrivere collettivamente delle storie, partecipando<br />

a narrazioni <strong>di</strong> cui è possibile mo<strong>di</strong>ficare l’andamento,<br />

all’infinito all’infinito. . E se potete fare questo con un testo che,<br />

insieme a un gruppo <strong>di</strong> amici virtuali state inventando,<br />

perché non farlo anche per i testi letterari esistenti,<br />

acquistando programmi grazie ai quali potrete cambiare<br />

le gran<strong>di</strong> storie che ci stanno ossessionando magari da<br />

millenni?” (U. Eco 2002, pp. 17-19 17 19) ) [→ cfr. la presunta riscrittura<br />

del finale nel Caso <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>]<br />

7

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

<strong>Il</strong> romanzo cerca perciò <strong>di</strong> rispondere alla domanda:<br />

cosa accade ai libri quando si trasgre<strong>di</strong>sce la loro presunta<br />

inviolabilità migrandone in un’altra epoca o libro fatti e<br />

personaggi?<br />

Fforde stesso ruba dai classici “fuori copyright” e opera<br />

cambiamenti: violazione del testo originale<br />

[Trasgressione della cornice testuale e rapimento dei<br />

personaggi: reificazione dei furti metaforici]<br />

E’ quin<strong>di</strong> anche:<br />

b) riflessione sulla letteratura<br />

postmoderna<br />

postmoderna: : auto auto-paro<strong>di</strong>a paro<strong>di</strong>a<br />

(tra gli altri esempi: Cronoguar<strong>di</strong>a<br />

flessione e fusione <strong>di</strong> tempo e<br />

spazio)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

“On August 19th 1985 <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> was kidnapped from<br />

the pages of Charlotte Brontë's masterpiece of<br />

Victorian fiction, only to return three weeks later,<br />

apparently unharmed. The story behind these strange<br />

events became known<br />

as 'The <strong>Eyre</strong> Affair'<br />

and featured a woman<br />

named Thursday Next<br />

of SpecOps SpecOps-27 27 (the<br />

literary Detective<br />

<strong>di</strong>vision of the Special<br />

Operations Network<br />

based in Swindon).”<br />

(www.thursdaynext.com)<br />

8

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Personificazione <strong>di</strong> minacce: 1) Jack Schitt<br />

Figura caricaturale del malvagio<br />

Longa manus della Goliath Corporation: multinazionale<br />

tentacolare che domina il mondo, anche quello della<br />

cultura con le sue pubblicità ubique e le sue<br />

sponsorizzazioni ( (brand brand, , logo…) logo…<br />

Pensa al portale come fonte inestimabile <strong>di</strong> riproducibilità<br />

e serialità, fonti <strong>di</strong> lucro e potere: “Anything Anything That The<br />

Human Imagination Can Think Up, We Can Riproduce. I<br />

Look At The Portal as Less Of a Gateway to A million<br />

World’s, But More Like A Three Dimensional Photocopier.<br />

With It We Can Make Anything We Want, Even Another<br />

Portal”<br />

↔ Fforde ha più volte confessato la speranza <strong>di</strong> veder<br />

funzionare i propri testi da ‘gateway’, cioè da porta <strong>di</strong><br />

accesso, al capitale culturale<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

2) Acheron Hades<br />

Importanza del nome: fiume Acheronte / hacker<br />

Compie “an an act of artistic barbarism so monstruous<br />

that I am almost ashamed of it myself” myself (mutazione<br />

genetica del testo)<br />

Nella sua autobiografia, Degeneration for pleasure<br />

and profit (nelle epigrafi) <strong>di</strong>chiara <strong>di</strong> farlo per pura<br />

fame <strong>di</strong> notorietà e guadagno. Dice a Mycroft Mycroft: :<br />

“Look what the papers say about me! […] HADES 74 74<br />

WEEKS AT TOP OF “MOST “MOST-WANTED WANTED LIST”<br />

a) minaccia delle logiche del mercato, del marketing<br />

9

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

b) minaccia della teoria e critica accademica<br />

Acheron è ex ex-professore professore carismatico, poi <strong>di</strong>ventato<br />

pericoloso: manipolazione dei testi per eccesso<br />

interpretativo?<br />

[Continue frecciatine al mondo accademico da parte <strong>di</strong><br />

Fforde (ve<strong>di</strong> la descrizione del <strong>di</strong>partimento del<br />

LiteraTec= versione paro<strong>di</strong>ata <strong>degli</strong> stu<strong>di</strong> letterari<br />

istituzionalizzati)]<br />

→ Da post post-strutturalismo strutturalismo e decostruzionismo,<br />

preconizzazione <strong>di</strong> serie <strong>di</strong> lutti (uccisioni?) in<br />

letteratura<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

“La fine del nuovo è stato quasi il motto del postmoderno. […]<br />

Molti “critici” hanno fatto e stanno ancora facendo questo. Sono<br />

<strong>di</strong>ventati guar<strong>di</strong>ani dell'esistente. Hanno cercato <strong>di</strong> annientare le<br />

generazioni successive, <strong>di</strong>cendo che tutto ormai era morto. Che<br />

non c'era più nessuno. Che nessun grande scrittore sarebbe più<br />

nato.[…] Gli ultimi trenta trenta anni del Novecento sono stati tutto un<br />

ratificare fini e morti. C’è stato un interminabile lavoro del lutto da<br />

parte <strong>di</strong> un’intera un’intera cultura che si autocondannava autocondannava a una con<strong>di</strong>zione<br />

terminale. Niente più reazione e invenzione! D'ora in avanti si<br />

potrà solo avere un rapporto ironico con l’arte della parola, e con<br />

la sua grandezza ormai tutta passata. Tutto questo ci ha lasciato<br />

in retaggio un’ un’ideologia ideologia terminale, <strong>di</strong> chiusura del futuro. Quella in<br />

cui oggi prosperano le macchine. Tutto questo è stato preparato<br />

da quella mostruosa miscela <strong>di</strong> ideologie che si è formata negli<br />

ultimi decenni, e che è stata tutta un inno alla clonazione clonazione, , e che si<br />

è saldata in modo incre<strong>di</strong>bile con la macchina pubblicitaria e con i<br />

biopoteri biopoteri. . Una vita senza alterità, senza fecondazione, senza<br />

nuovi inizi. È questa la clonazione. (C. Benedetti, 2007)<br />

→ tematizzazione ironica dei cloni in Fforde: Dodo 1.1, Felix8…)<br />

Felix8…<br />

10

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

2) Indagine all’interno dei meccanismi del<br />

letterario<br />

autore riesce a esaminare molto da vicino i<br />

meccanismi <strong>di</strong> funzionamento del romanzo (del<br />

romanzo in generale e <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> in particolare)<br />

grazie al portale della prosa (computer?) inventato<br />

dallo zio Mycroft (Microsoft?), che consente <strong>di</strong><br />

accedere fisicamente al bookworld (entrare nel libro)<br />

[nel libro successivo, <strong>Il</strong> pozzo della trame perdute perdute, , vera e propria<br />

officina della scrittura, giocattolo aperto e smontato, con ven<strong>di</strong>tori <strong>di</strong><br />

trame 3x2, <strong>di</strong> verbi, antefatti o note a pié <strong>di</strong> pagina… pagina…]<br />

→ REIFICAZIONE dei meccanismi <strong>di</strong> funzionamento<br />

<strong>di</strong> scrittura, lettura, e relazione scrittore scrittore-lettore lettore (finale)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

3 incursioni all’interno del romanzo:<br />

1) Da parte <strong>di</strong> Thursday Next Next: : grazie soltanto all’aiuto<br />

della sua immaginazione; aveva nove anni ed era in<br />

visita con gli zii a Haworth (capitolo 6): provoca la<br />

caduta <strong>di</strong> Rochester da cavallo<br />

2) Da parte del rapitore <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> (capitolo 29,<br />

“<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>”) grazie al portale della prosa<br />

3) Da parte <strong>di</strong> Thursday Next <strong>di</strong> nuovo, ma questa volta<br />

anche lei grazie al portale della prosa, per restituire<br />

<strong>Jane</strong> a Rochester e alla sua storia, e per acciuffare<br />

Acheron Hades (capitoli 32-34 32 34)<br />

*Anche escursioni da parte <strong>di</strong> Rochester nella ‘realtà’<br />

11

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Rapporto tra le due <strong>di</strong>mensioni:<br />

Thursday Next / <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><br />

Thursday Thursday, , detective letteraria, ex ex-studentessa studentessa <strong>di</strong><br />

Acheron Hades<br />

somiglia molto a <strong>Jane</strong> nelle fattezze (donna<br />

or<strong>di</strong>naria) e nel carattere (donna in<strong>di</strong>pendente,<br />

determinata, non teme <strong>di</strong> esprimere sue opinioni):<br />

“When she turned I could see that her face was plain<br />

and outwardly unremarkable, yet possessed of a<br />

bearing that showed inner strength and resolve. […] I<br />

had realized not long ago that I myself was no beauty<br />

[…] but in that young woman I could see how those<br />

principles could be inverted. I felt myself stand more<br />

upright and clench my jaw in a subconscious mimicry<br />

of her pose” (<strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> Affair Affair, , 66-67): 66 67): IDENTIFICAZIONE<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

vive una storia sentimentale molto simile, ma questa<br />

volta è Rochester a inviare un legale per interrompere<br />

le nozze dell’ex dell’ex-fidanzato: fidanzato: rovesciamento paro<strong>di</strong>co<br />

a volte incontra Rochester, dentro e fuori dal<br />

bookworld <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>, , e in qualche modo sostituisce<br />

<strong>Jane</strong> quando lei non c’è (riempie le sue assenze)<br />

come <strong>Jane</strong>, anche lei è ‘scrittrice’:<br />

scrive un’autobiografia (ve<strong>di</strong> alcune epigrafi <strong>di</strong> cap.)<br />

al posto <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong>, ‘riscrive’ alcuni episo<strong>di</strong> (fa cadere<br />

Rochester da cavallo; la sua caccia ad Acheron fa sì<br />

che Thornfiled vada in fumo e Bertha muoia; è lei a<br />

chiamare <strong>Jane</strong> nascosta sotto la sua finestra) e il finale<br />

del romanzo vittoriano:<br />

→ sovrapposizione <strong>di</strong> Thursday / <strong>Jane</strong> / C. Bronte<br />

12

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Dal momento che la narrazione <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> è in 11°<br />

°<br />

persona, dopo che <strong>Jane</strong> viene rapita (appena dopo<br />

aver spento l’incen<strong>di</strong>o al letto <strong>di</strong> Rochester) le pagine<br />

del romanzo <strong>di</strong>ventano bianche (‘carta bianca a… a…’) ’)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Meccanismi de de-autorializzanti<br />

autorializzanti postmoderni<br />

l’ l’autrice autrice Charlotte Bronte non è quasi mai menzionata,<br />

prevale <strong>Jane</strong> in quanto narratrice: “ritorno del narratore”<br />

non come soggettività piena e centro prospettico<br />

onnisciente del romanzo ottocentesco, ma come<br />

semplice funzione scritturale (Splendore): quando <strong>Jane</strong><br />

sparisce, le pagine <strong>di</strong>ventano bianche (dov’è l’Autore?)<br />

con l’entrata <strong>di</strong> Thursday, l’autore non è più centro unico,<br />

si sdoppia, moltiplica, fornendo la possibilità <strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong>verse<br />

<strong>di</strong>rezioni o conclusioni della storia (due possibili finali:<br />

quello che avrebbe potuto essere e quello che è stato)<br />

Espe<strong>di</strong>ente funzionale alla problematizzazione del rapporto<br />

arte-realtà arte realtà: : autore non è più depositario <strong>di</strong> Verità e il<br />

testo non è più inteso ingenuamente come specchio del<br />

Reale<br />

13

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Artificialità della letteratura<br />

1. autore mette in evidenza meccanismi artificiali <strong>di</strong><br />

costruzione e quasi casualità del plot letterario letterario, , affidato<br />

a un’ un’autorità autorità scritturale con<strong>di</strong>visa, <strong>di</strong>sseminata; cui è<br />

negata l’in<strong>di</strong>vidualità che era la forza del narratore sette-<br />

ottocentesco<br />

2. attira attenzione ‘<strong>di</strong>etro le quinte’, quinte’ , si assicura cioè che il<br />

lettore non <strong>di</strong>mentichi mai che c’è qualcuno<br />

<strong>di</strong>etro/dentro il testo<br />

3. interrompe l’immersione del lettore violando<br />

costantemente il confine tra realtà e finzione<br />

(meccanismi <strong>di</strong> straniamento), e spesso invitandolo ad<br />

affiancarlo nel proce<strong>di</strong>mento narrativo o a scegliere tra<br />

<strong>di</strong>verse soluzioni possibili → il lettore entra nell’opera e<br />

può riscriverla come vuole<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

‘Reificazione’ dell’atto <strong>di</strong> lettura:<br />

grazie al processo solitamente astratto <strong>di</strong> accesso<br />

immaginativo al testo ( (Imagino Imagino-transference<br />

transference), ), e anche in<br />

base al <strong>di</strong>verso contesto storico e ideologico nel quale ci<br />

si trova ( (lettura lettura situata situata), ), ogni lettore si trova a ‘riscrivere’<br />

il proprio testo, come se riempisse dei gap lasciati vuoti<br />

da scrittura plurale, ambigua, sempre percorribile in<br />

molteplici sensi e quin<strong>di</strong> ‘scrivibile’ (R. Barthes) Barthes<br />

“When I set up a character (I hope) I set them up so the<br />

reader fills in the blanks – to be honest, most of the hard<br />

work is done by the reader; I just throw up a few flags to<br />

guide them down the course” (Fforde Fforde, , da un’intervista):<br />

un’intervista :<br />

→ invita anche I suoi lettori a interagire e a fornire I<br />

propri significati all’interno <strong>di</strong> un forum interattivo<br />

14

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

‘invitato’ a entrare nel testo, il lettore finisce per<br />

appropriarsi <strong>di</strong> parole e significati<br />

“I lettori sono i miei vampiri. […] s’appropriano delle<br />

parole man mano che si depositano sul foglio” (I.<br />

Calvino)<br />

→ (cfr. le pagine <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> che <strong>di</strong>ventano<br />

bianche)<br />

lettore ‘bracconiere’ del testo (de Certeau 1984): rende il<br />

testo “habitable habitable like a rented apartment” apartment<br />

soggetto attivo, responsabile <strong>di</strong> una ‘produzione’<br />

secondaria [FANDOM: lettori ‘avanzati’, producono testi<br />

in cui espandono, riscrivono, ricontestualizzano i testi<br />

che amano e che fanno circolare all’interno <strong>di</strong> comunità<br />

altamente partecipative ( (Jenkins Jenkins 1992): cfr. la comunità<br />

<strong>di</strong> fanatici letterari del romanzo <strong>di</strong> Fforde Fforde]<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Quando <strong>Jane</strong> viene restituita al romanzo, ironicamente<br />

le prime parole che compaiono sono:<br />

"In the name of all the elves in Christendom, is that <strong>Jane</strong><br />

<strong>Eyre</strong>?" he demanded. "What have you done with me,<br />

witch, sorceress? Who is in the room besides you?<br />

Have you plotted to drown me?"<br />

"I will fetch you a candle, sir; and, in Heaven's name, get<br />

up. Somebody has plotted something something: : you cannot too<br />

soon find out who and what it is." (ch ch. . XV)<br />

riferimento alla ‘trama’ criminale fuori dal bookworld tesa<br />

a cambiare la ‘trama’ narrativa che Fforde sta esaminando – e<br />

rimaneggiando! – attraverso incursioni <strong>di</strong> Acheron e Thursday<br />

15

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

La questione del supposto finale cambiato<br />

Le incursioni <strong>di</strong> Thursday fanno fanno sì che il finale cambi,<br />

un finale che però Fforde immagina <strong>di</strong>verso da quello<br />

che noi in effetti conosciamo: immagina che il<br />

romanzo originale finisse con <strong>Jane</strong> che si rassegnava<br />

a seguire St. John Rivers in In<strong>di</strong>a ma senza sposarlo<br />

L’amicizia e la gratitu<strong>di</strong>ne verso Rochester (che una<br />

volta le ha salvato la vita) induce Thursday a decidere<br />

<strong>di</strong> aiutarlo a coronare il suo sogno d’amore con <strong>Jane</strong> e<br />

a sod<strong>di</strong>sfare sod<strong>di</strong>sfare tutti i lettori scontenti del finale con St.<br />

John Rivers<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Rochester <strong>di</strong>ce che lui ha sempre o<strong>di</strong>ato quel<br />

finale<br />

Thursday <strong>di</strong>ce: “No one likes the en<strong>di</strong>ng”; the<br />

book might have been more satisfactory “if<br />

<strong>Jane</strong> had returned to Thornfield Hall and<br />

married Rochester.”<br />

Un altro personaggio <strong>di</strong>ce che è “a bit of an<br />

anti anti-climax” climax”<br />

Si suggerisce anche che “millions of others are<br />

<strong>di</strong>sappointed”<br />

16

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Lettore americano in visita a Haworth:<br />

“I had trouble with the end of <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>” [..] she<br />

agrees to go with this drippy St. John Rivers guy<br />

but not to marry him, they depart from In<strong>di</strong>a and<br />

that’s the end of the book? Hello? What about a<br />

happy en<strong>di</strong>ng? […] the book cries out for a<br />

strong resolution, to tie up the narrative and<br />

finish the tale. I get the feeling from what she<br />

wrote that she just kinda pooped out” (TEA, 65)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

gli psicologi <strong>di</strong>cono che cambiare la trama è una tipica<br />

risposta psicologica a un testo narrativo quando i<br />

lettori considerano possibili alternative agli eventi<br />

giocosamente vengono sollevate anche questioni<br />

circa:<br />

l’ambivalenza e l’ l’ambiguità ambiguità della conclusione del<br />

romanzo <strong>di</strong> Charlotte Bronte (la tensione tra la lettura<br />

femminista e quella romantica) che produce un<br />

<strong>di</strong>alogo ininterrotto tra questo classico e i lettori <strong>di</strong><br />

ogni tempo<br />

la preferenza della linea romantica da parte della<br />

massa e delle trasposizioni successive<br />

17

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

l’effettiva influenza delle convenzioni <strong>di</strong> genere e la<br />

<strong>di</strong>pendenza dalle norme legate ad esso perché la<br />

lettura ci sod<strong>di</strong>sfi: orizzonte <strong>di</strong> attesa<br />

l’ l’investimento investimento passionale che la lettura del romance<br />

prevede e la dose cospicua <strong>di</strong> identificazione tra la<br />

lettrice e la relazione eroe eroe-eroina eroina che avviene nell’atto<br />

della lettura e che ci fa credere <strong>di</strong> poter<br />

interagire/interferire con essi<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

In realtà INGANNO<br />

<strong>Il</strong> finale non cambia<br />

sulla pagina che era<br />

<strong>di</strong>ventata bianca<br />

ricompaiono le stesse e<br />

identiche parole che<br />

conosciamo da sempre<br />

[vs. le parole scritte sulle<br />

pagine mostrate più volte nel film del 1944!]<br />

18

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Quale potrebbe essere lo scopo del<br />

giocoso inganno da parte dell’autore?<br />

Due spiegazioni antitetiche antitetiche:<br />

1. sfida ogni possibile contenimento del romanzo nel<br />

genere romance e lo valorizza come letteratura <strong>di</strong><br />

qualità; siccome la popolarità <strong>di</strong> cui gode nel<br />

romanzo non può essere attribuita al lieto fine, ci<br />

deve essere qualcosa <strong>di</strong> intrinseco intrinseco al testo stesso stesso. .<br />

Cfr. le parole della guida <strong>di</strong> Haworth: “the sheer<br />

exuberance of the writing easily outweighs any of its<br />

small shortcomings”<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

2. anche se la lettura del finale proposta come<br />

originale da Fforde sarebbe quella che la critica<br />

del Novecento avrebbe preferito (perché più<br />

congeniale al carattere <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> e alle sue<br />

esternazioni in merito alla sua in<strong>di</strong>pendenza),<br />

Fforde ristabilisce l’or<strong>di</strong>ne convenzionale facendo<br />

sì che Thursday scriva e sia inscritta a sua volta<br />

in una trama sentimentale convenzionale<br />

Secondo Erica Hateley (“The End of the <strong>Eyre</strong><br />

Affair” 2007) anche qui, come in <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>:<br />

“[…] tensions are reproduced only to be safely<br />

contained within a conservative model of<br />

romantic closure.”<br />

19

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Attenua questa seconda interpretazione il fatto che<br />

Fforde usa stratagemmi che sdrammatizzano e<br />

paro<strong>di</strong>zzano l’atmosfera gotica del romanzo canonico<br />

e i suoi eccessi sentimentali/melodrammatici<br />

la voce camuffata <strong>di</strong> Thursday che grida “<strong>Jane</strong>, <strong>Jane</strong>… <strong>Jane</strong>…” ”<br />

al posto <strong>di</strong> un’invocazione telepatica o soprannaturale;<br />

ragazzina che dal futuro piomba dritta sulla strada del<br />

suo eroe, che aveva ignorato <strong>Jane</strong>, e lo fa cadere da<br />

cavallo;<br />

aristocratico dal fascino byroniano che, in assenza <strong>di</strong><br />

<strong>Jane</strong>, raggranella qualche soldo come cicerone per<br />

poter sostenere le spese onerose del castello;<br />

una Bertha che, finalmente libera, finisce per scatenare<br />

la sua ira su Acheron Hades uccidendolo con un paio <strong>di</strong><br />

forbici d’argento (non è più lei la vampira ma lui)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

“[…] half of my work is done when a reader has completed<br />

their first twenty or thirty years of life. I take things from<br />

their memory and how they perceive them and then merge<br />

them together in new and unexpected ways.” (Fforde Fforde cit. in<br />

White 2002)<br />

“[…] the incongruous juxtaposition of low comedy and high<br />

eru<strong>di</strong>tion eru<strong>di</strong>tion” rende The <strong>Eyre</strong> Affair “a silly book for smart<br />

people: postmodernism played as a howling farce”<br />

(M.C. Shaar, recensione sull’Independent<br />

sull’ Independent)<br />

Script de de-familiarizzanti, familiarizzanti, stranianti (incongruenti per stile e<br />

registro) <strong>di</strong>sorientano il lettore ingabbiato in una limitativa<br />

lettura <strong>di</strong> genere: frustrano il suo orizzonte cognitivo<br />

/emozionale/<strong>di</strong> attesa<br />

20

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Inoltre:<br />

liberano il testo da se<strong>di</strong>mentazioni interpretative<br />

accademiche che possono averne occluso le<br />

irriducibili aperture, l’ambivalenza e l’ambiguità<br />

(l’inelu<strong>di</strong>bile tensione tra possibili <strong>di</strong>fferenti letture) che<br />

continuano ad affascinare il lettore <strong>di</strong> ogni epoca<br />

“The <strong>Eyre</strong> Affair is both a satirical deflation of the<br />

model and a supreme tribute to its continuing appeal<br />

and fascination” (M. Rubik, “Invasions into Literary texts…”,<br />

2007)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

“The point of using the classics classics... ... is that I always felt<br />

the classics had become stuffy through being<br />

academized […] <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> is a study text and it<br />

should have never been made a study text”<br />

(Fforde Fforde, , cit. in Wells 2007: 198)<br />

→ unica seria seria minaccia alla letteratura percepita<br />

dall’autore è forse l’atrofizzazione<br />

l’ atrofizzazione del testo<br />

letterario nelle mani <strong>di</strong> chi da secoli lavora per<br />

mantenerne lo status <strong>di</strong> ‘monumento’ canonico<br />

21

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Thursday Next si pente <strong>di</strong> aver alterato il finale <strong>di</strong> <strong>Jane</strong><br />

<strong>Eyre</strong> contravvenendo alla sua formazione, ma il 99%<br />

della popolazione ne è contento contento. . Gli unici che continuano<br />

a esprimere rimostranze sono i membri della purista<br />

Brönte Federation<br />

Parole consolatorie del presidente <strong>di</strong> un gruppo<br />

<strong>di</strong>ssidente in forte contrasto con la federazione:<br />

“Charlotte <strong>di</strong>dn’t leave the book to them, Miss Next” said a<br />

man dressed in a linen suit who had a large blue<br />

Charlotte Bronte rosette stuck incongruously to his lapel.<br />

“The federation are a bunch of stuffed shirts. Allow me to<br />

introduce myself. Walter Branwell, chairman of the<br />

federation splinter group ‘Bronte Bronte for the People.” People (361) 361)<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

“Until <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> was kidnapped I don’t think anyone […]<br />

realized quite how popular she was. It was as if a living<br />

national embo<strong>di</strong>ment of England’s literary heritage had<br />

been torn from the masses”.<br />

(300)<br />

pezzo vivente della memoria collettiva popolare oltre che<br />

testo sacro del canone<br />

letteratura come qualcosa <strong>di</strong> immateriale, <strong>di</strong> fluido, <strong>di</strong><br />

mutevole, <strong>di</strong> vivo<br />

“L’opera letteraria è una <strong>di</strong> queste minime porzioni in cui<br />

l’universo si cristallizza in una forma, in cui acquista un<br />

senso, non fisso, non definitivo, non irrigi<strong>di</strong>to in<br />

un’immobilità mortale, ma vivente come un organismo”<br />

(Calvino, Lezioni americane americane)<br />

22

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Solo olo a partire dalla metà del Settecento, la critica e<br />

l’estetica ne hanno fatto la riserva <strong>di</strong> una casta<br />

sacerdotizia allontanandola dagli interessi e dai<br />

bisogni della gente comune. Deve tornare a vivere in<br />

comunità<br />

società utopica creata da Fforde è società in cui il<br />

letterario crea “identità e comunità” comunità”, , facendosi moneta<br />

corrente <strong>degli</strong> scambi tra la gente comune, ma a quei<br />

livelli <strong>di</strong> fandom ai quali attualmente si assiste soltanto<br />

per serie televisive o letteratura <strong>di</strong> genere<br />

<strong>Il</strong> <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>caso</strong> ‘ ‘<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’ <strong>Eyre</strong>’<br />

Rapporto high culture / popular culture<br />

<strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> prima <strong>di</strong> trovare posto sul pie<strong>di</strong>stallo<br />

marmoreo del canone, era popolarissimo<br />

bestseller <strong>di</strong> qualità<br />

Definizione (U. Eco, 2002)<br />

romanzo a vocazione popolare che fa uso <strong>di</strong> alcune<br />

strategie ‘colte’<br />

o “romanzo ‘colto’ che per qualche misteriosa ragione<br />

<strong>di</strong>venta popolare” perché “piace anche se ha qualche<br />

pregio artistico, e impegna il lettore con problemi o<br />

proce<strong>di</strong>menti che una volta erano appannaggio della sola<br />

arte <strong>di</strong> élite”. → Anche <strong>Il</strong> <strong>caso</strong> <strong>Jane</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> lo è?<br />

23