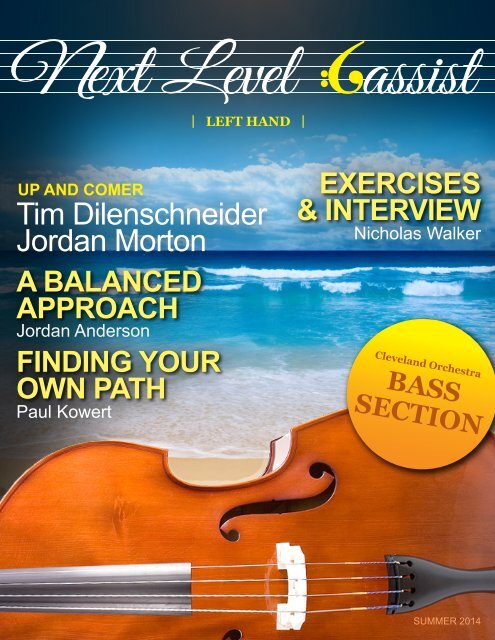

Next Level Bassist Left Hand

Summer 2014 edition of Next Level Bassist. Left hand techniques and exercises by Nicholas Walker, Jordan Anderson, Paul Kowert. Section Spotlight on Cleveland Orchestra. Up and Comers Tim Dilenschneider and Jordan Morton

Summer 2014 edition of Next Level Bassist. Left hand techniques and exercises by Nicholas Walker, Jordan Anderson, Paul Kowert. Section Spotlight on Cleveland Orchestra. Up and Comers Tim Dilenschneider and Jordan Morton

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

| <strong>Left</strong> hand |<br />

Up and Comer<br />

Tim Dilenschneider<br />

Jordan Morton<br />

A balanced<br />

approach<br />

Jordan Anderson<br />

finding your<br />

own path<br />

Paul Kowert<br />

exercises<br />

& interview<br />

Nicholas Walker<br />

Cleveland Orchestra<br />

bass<br />

section<br />

summer 2014

Contents<br />

Summer 2014<br />

Feature Story<br />

5 A Balanced Approach<br />

jordan anderson<br />

9 Spotlight: Cleveland Orchestra<br />

Bass Section<br />

10 Up and Comer<br />

tim dilenschneider<br />

13 Exercise Piece<br />

nicholas walker<br />

18 Up and Comer<br />

jordan morton<br />

21 Finding Your Own Path<br />

Paul Kowert<br />

26 Interview with Nicholas Walker<br />

Contributors<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

PUBLISHER / FOUNDER<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

editor<br />

Edward Paulsen<br />

SALES<br />

Karen Han<br />

Layout designer<br />

2 NOV/DEC SUMMER 2013 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

Publisher’s Note<br />

It is no secret in the bass community that there have been a lot of innovations in<br />

left hand technique. It seems that in the past decade, the double bass has shed<br />

the stereotypes of being the clumsy and slow moving grandfather of the string<br />

section, and stepped into the spotlight. Developments in string technology, bass<br />

setup approaches, and the expanded use of thumb position all over the bass have<br />

allowed us to explore new possibilities in all styles and genres.<br />

Among the most innovative bass players in the 20 th century, few have shaped so<br />

many minds as Francois Rabbath and Edgar Meyer. In Nicholas Walker’s expansive<br />

article, he seeks to incorporate the highly structured teachings of Rabbath and the<br />

still-mysterious but infinitely intriguing thumb position concepts that Edgar Meyer<br />

has been teaching to a select few in recent years. Given that there are only a few places<br />

to find this information, I think this article and the additional materials on our website<br />

might be one of the most important resources for double bass in the last 100 years.<br />

As a student at the Curtis Institute of Music, I consider myself very fortunate that Jordan<br />

Anderson was one of my colleagues and an incredible influence. His chocolate-like tone,<br />

his incredible consistency, and great attitude towards working hard encouraged me to<br />

play my personal best. In addition to his principal position with the Seattle Symphony,<br />

he has an incredible track record as a teacher - sending student after student on to study<br />

at the Curtis Institute of Music and other conservatories and the music of the future.<br />

His perspective on practicing and technique is a must-read for aspiring conservatory<br />

students, orchestra professionals, or anyone looking to create music at the highest levels.<br />

Paul Kowert has enjoyed a rare and singular career to date as the bassist for the<br />

Punch Brothers, and part of the trio Haas Kowert Tice. His in-depth exploration of<br />

Edgar Meyer’s technique as well as his incredibly brave decision to embrace a career<br />

in bluegrass and folk music are an inspiration to anyone who has ever felt the pull of<br />

a non-classical career within a conservatory setting. His open-eyed and inclusive<br />

approach to practicing should be experienced by every classical player.<br />

We are also extremely pleased to feature the incredible bass section of the Cleveland<br />

Orchestra, one of the most venerated orchestras in the world. The glory of playing with<br />

a group of that caliber is evident in the comments submitted by the wonderful section<br />

members. Finally, we are instituting a new “Up and Coming” column, featuring the<br />

talented and hard working Tim Dilenschneider. Tim recently graduated from the Curtis<br />

Institute of Music, was accepted to the New World Symphony, and is an A-list substitute<br />

for the Philadelphia Orchestra. Tim was a student of mine in high school, and has been a<br />

participant in two years of Wabass Institute and Wabass Intensive.<br />

I hope that in reading this issue of <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Bassist</strong>, you will be filled with inspiration<br />

to experiment and innovate. We are in the dawn of a new era of discovery, and every<br />

single one of us can take part. This journal is all about open minded sharing of knowledge,<br />

and I would like each and every one of you to share your thoughts as we all head to the<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong>.<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Publisher <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

3

CARLO CARLETTI WILLIAM TARR PAUL TOENNIGES SAMUEL ALLEN DANIEL HACHEZ<br />

PIETRO MENEGHESSO LORENZO & THOMASSO CARCASSI PAUL CLAUDOT GIOVANNI LEONI<br />

ARMANDO PICCAGLIANI GAND & BERNARDEL STEFAN KRATTENMACHER JAMES COLE<br />

FRATELLI SIRLETTO ALASSANDRO CICILIATTI AKOS BALAZS SAMUEL SHEN G.B. CERUTI<br />

PAOLO ROBERTI CHRISTIAN PEDERSEN PAUL HART CHRISTOPHER SAVINO JAY HAIDE<br />

ANDREW CARRUTHERS GUNTER VON AUE BARANYAI GYORGY CARLO CARLETTI WILLIAM TARR<br />

PAUL TOENNIGES SAMUEL ALLEN DANIEL HACHEZ PIETRO MENEGHESSO LORENZO &<br />

THOMASSO CARCASSI PAUL CLAUDOT GIOVANNI LEONI ARMANDO PICCAGLIANI GAND<br />

& BERNARDEL STEFAN KRATTENMACHER JAMES COLE FRATELLI SIRLETTO ALASSANDRO<br />

roBertson reCital Hall<br />

2013 Bass ColleCtion<br />

partial<br />

4 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

www.RobertsonViolins.com<br />

Tel 800-284-6546 | 3201 Carlisle Blvd. NE | Albuquerque, NM USA 87110

Jordan Anderson<br />

A Balanced Approach<br />

Like a lot of people from my generation and before, I started<br />

learning to play bass using the Simandl method. However, I<br />

found this approach to learning the bass musically stale and<br />

unrewarding. Not too much later on in my studies, I was introduced<br />

to the Rabbath method by my private bass teacher Nancy Bjork.<br />

Immediately, I felt a musical connection with the exercises and noticed<br />

a fingering system that allowed for many more left hand options that<br />

Simandl never explored. Nancy then introduced me to Paul Ellison<br />

and sent me off to Domaine Forget, a camp where he was teaching.<br />

At Domaine, Paul continued to emphasize the Rabbath philosophy of<br />

having fewer positions by anchoring the thumb. This could encompass<br />

a range of notes by extending above and below the typical Simandl<br />

position. Paul also stressed the importance of drawing the sound<br />

starting from your back, pronation in the bow hand and learning<br />

to torque the bow into the string at the tip.<br />

I also met Hal Robinson at Domaine Forget,<br />

and he started showing me some of his own<br />

approaches to the Rabbath method and use of<br />

the left hand pivot. He also opened up my<br />

approach to vibrato, as well as his approach<br />

to drawing a big, round and focused<br />

sound, always with musicality in mind.<br />

One of the big impressions Hal left on<br />

me was to never forget about the musical<br />

side of practicing. He said even during<br />

slow practice one should be aware of the<br />

phrasing and expression at all times. Hal<br />

also brought to light some fresh applications<br />

for my thumb in the left hand and the<br />

right hand. Eventually I started to come<br />

up with my own concepts. When Edgar<br />

Meyer came on the scene, he really blew the<br />

lid right off standard, traditional bass technique.<br />

His approach allowed a lot of people to re-imagine<br />

what they could do with the bass from a technical<br />

and musical standpoint.<br />

The Rabbath books were very useful as a student.<br />

I went through the Simandl and Storch-Hrabe books, but I don’t use<br />

them any longer. I don’t feel like they offer any new information to me<br />

as a professional or have much bearing on the technique I promote to<br />

my students. If my students are required to play excerpts from those<br />

books at auditions, we usually change most of the fingerings that are<br />

printed. Perhaps the most important book-based resources I recommend<br />

are Boardwalkin’ and Strokin’ by Hal Robinson (available from<br />

Robertson and Sons Violin Shop). However, probably the one thing<br />

I use more than books is plain, old, meat-and-potatoes scales and<br />

arpeggios. That’s the foundation of my bass playing. I know there are<br />

scale books out there that offer fingerings but I have a routine that<br />

I have customized for myself. As far as etudes, I don’t have any real<br />

reference books. So after scales and arpeggios, my advanced students<br />

look to the Bach cello suites for their technique building and my<br />

beginning and intermediate students look to scales, arpeggios, and<br />

isolated excerpts from the solo literature.<br />

Practicing<br />

On a day with a lot of practice time, I start with long bows, metronome<br />

set to 60. I try to sustain each bow as long as possible - maybe 6 clicks<br />

per bow. I go back and forth on each string to really see how long I<br />

can sustain notes. I whittle it down to 5, 4, 3 clicks per bow before<br />

changing up. When I’m down to 2 clicks each, I’ll subdivide the bow<br />

into different segments. I’ll try to draw a down bow for 2 clicks and<br />

then an up bow that stays in the lower half of the bow. I then move this<br />

exercise further out to the tip for the same effect in the upper half of<br />

the bow. My goal is to control the bow through the most basic, simple<br />

legato strokes. Then I’ll go down to one click per up bow and one click<br />

per down bow. This time I break the bow into lower<br />

third, middle third and upper third. My next step<br />

is string crossings, using the same basic system<br />

as the long tones. I don’t go much faster than<br />

1 click per bow. I’ll start with a quarter note<br />

down bow on the E string, slurred to a<br />

quarter note on the A string. Then a legato<br />

up bow quarter on the A string, slurred<br />

back to the E string. I’ll repeat this 2-string<br />

exercise between A and D, and D and G.<br />

I will then repeat the whole series in the<br />

upper half, but starting up bow on the G<br />

string and slurring to the D string,<br />

eventually working my way back to the E string. I even<br />

try the same exercise attempting to slur E string to D<br />

string by temporarily rolling the bow over the A string<br />

and back as well as A string to G string and back. This<br />

exercise can be reversed as well to start up bow on the<br />

G string slurring to the A string and back while staying<br />

in the upper half of the bow. At this point, my right arm<br />

is feeling very good, my body is feeling prepared, with my<br />

feet grounded and my back engaged. Finally, I’ll start to add<br />

the left hand.<br />

With scales and arpeggios I like to relate the keys of the pieces I’m<br />

working on to the scales I practice each day. If the piece I’m working<br />

on involves E minor, then I’ll practice that scale/arpeggio as well as<br />

the relative major (G Major), and the parallel major (E Major). I start<br />

these with the metronome still set to 60, and I always begin without<br />

using vibrato. I usually start with 2 clicks per note (half notes). I’ll<br />

work my way through the scale, and then go back afterwards and add<br />

vibrato. Then I begin to slur two notes in the scale at one click per<br />

note, and finally move to separate bows on each quarter note. I can’t<br />

always make it through all the scales every day, because I usually have<br />

time constraints on what I need to practice for the day. In a perfect<br />

world, I would have enough time to start my scales in half notes, and<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

5

get down to sixteenth notes or sextuplets,<br />

separate on/off the string and slurred, at the<br />

fastest, every day. In a nutshell, the object is<br />

to start out slowly and work your way up to<br />

a routine where you’re playing very quickly<br />

and effortlessly through any key.<br />

When it comes to students, I don’t like to<br />

force them to try and do what works for me.<br />

I show them what I do, but it is always with<br />

the information about why I arrived at that<br />

particular practice solution to solve a problem<br />

I had, or to tackle a concept I wanted to<br />

master. What really matters is identifying<br />

what works for an individual, because everyone<br />

is different. That said, there is a common<br />

thread amongst warm-up routines. It’s all<br />

about being loose, being warm, being agile,<br />

and being strong. I like to push my students<br />

to do what I do only if they don’t already have<br />

a good warm-up system of their own. For<br />

example, I have more trust in an advanced<br />

student preparing for a college audition than<br />

a beginning student who is having position<br />

problems. I’ll push my philosophy and<br />

routine more strictly on a student with<br />

remedial needs than someone who already<br />

has strong concepts.<br />

I’m also an advocate of extremely slow practice<br />

for both new material and repertoire I’ve<br />

known for a long time. Any orchestral excerpt<br />

that has consecutive fast notes, such as the<br />

March at letter K in the 4 th movement of<br />

Beethoven’s 9 th Symphony, is a good example<br />

of repertoire that will benefit from extremely<br />

slow practice. Besides hooked bowings in the<br />

middle, it is mainly characterized by constant<br />

eighth note motion, which you can slow<br />

down to make the practice meditative and<br />

careful. Other candidates for slow practice are<br />

the Trio from Beethoven’s 5 th Symphony, the<br />

Badinerie from Bach’s 2 nd Orchestral Suite,<br />

the outer movements of Mendelssohn’s 4 th<br />

Symphony or Mozart’s 35 th Symphony. Mozart<br />

35 has some slurs in the 4 th movement, but<br />

because of the extreme tempo this can still be<br />

achieved at half tempo. The same can be said<br />

of the 4 th movement of Brahms 2 nd Symphony.<br />

The D minor triplet section from the first<br />

movement of Koussevitsky is a good solo<br />

example that works for ultra slow practice.<br />

This is in contrast to orchestral excerpts like<br />

#40 from Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben, and<br />

Verdi’s Othello where excessively slow<br />

practice makes the bowings challenging<br />

and complicates the issue.<br />

In terms of preparation for the day of<br />

an audition, recital, or any other sort<br />

of performance, I have a physical and<br />

mental warm-up as follows:<br />

If you know what you’re going to play that<br />

day, or if you’ve just been given a list of<br />

material to play and have 30 minutes to warm<br />

up before performing, I recommend starting<br />

with the last piece, excerpt or movement<br />

you’ll be playing in the presentation. I will<br />

then work backwards, starting with the last<br />

movement or excerpt at half tempo (or<br />

whatever is practical based on the piece).<br />

Slow movements and excerpts don’t necessarily<br />

benefit from this approach, so one must use<br />

common sense to determine how best to<br />

practice in a relaxed and focused manner.<br />

Work through the repertoire backwards with<br />

the intention of timing your warm-up to end<br />

very close to the moment when you will be<br />

heading out on stage. The last thing you do<br />

should be the beginning of your program,<br />

so your mind is on the beginning of your<br />

presentation, and you are focused completely<br />

on the task at hand.<br />

My mental warm up involves being able to<br />

clearly visualize myself in every aspect of the<br />

Lemur Music<br />

“Everything for the Double Bass”<br />

Full Service Lutherie Shop, Bass<br />

Showroom, and On-Line Store<br />

Dozens of Basses, Strings,<br />

Bows, Rosins, Gig Bags,<br />

Stands, Accessories, Pickups,<br />

Speakers, Amps, Music &<br />

Recordings, plus hundreds of<br />

items you always dreamed of<br />

finding...all in one place.<br />

32240 Paseo Adelanto<br />

Suite A<br />

San Juan Capistrano, CA<br />

92675<br />

lemur@lemurmusic.com<br />

800-246-BASS<br />

www.lemurmusic.com<br />

6 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

eventual performance. I try to imagine holding the bass and preparing<br />

to walk out onto the stage. (Or whatever setting I know I will be in) I<br />

feel my nerves relaxing as I place the heavy bass and end pin securely<br />

into the floor. I imagine getting the stool into position. I ask myself<br />

some questions: How does the bow feel in my right hand? How does<br />

my left hand lay into position on the board? I then create in my mind<br />

a confident performance while all along breathing in a controlled<br />

manner and enjoying the unfolding phrases. Finally I will see the<br />

finish of my performance and feel the satisfaction of ending on a good<br />

note, including hearing the audience applause and then walking off the<br />

stage. This mental exercise can be very powerful in relieving yourself<br />

of any anxiety from what is about to happen.<br />

Every time I pick up the bass, I am attempting to manage the challenges<br />

in my playing. I think that if you have a strategy for dealing<br />

with them, you are much less likely to view them as challenges. It’s all<br />

about body management. A good example is nerves. Everyone out<br />

there deals with nerves. If you have a plan to deal with them, there’s<br />

a much better chance you can control them. Whether the problems<br />

manifest mentally or physically, or both, being clearheaded, being<br />

focused on the task at hand, and having lots of preparation are vital.<br />

As a young player in high school, playing bass came easy to me, and<br />

like a lot of professionals it spoke to me early on. But at a certain point<br />

in everyone’s career, you eventually hit a wall. This is usually because<br />

you’ve seen someone else do something incredible with the bass and<br />

you want to do what they’re doing and find that you can’t. Hearing<br />

Hal Robinson or Edgar Meyer play often left me wondering how they<br />

do that!? The light bulb moment comes when you realize that they<br />

worked their asses off, they had a strategy, and went through a lot of<br />

preparation to get there.<br />

Having an organized approach to daily practicing is the most<br />

important thing. There is dumb, bad, excessive practice, but for the<br />

most part people simply need to practice to grow. They need to learn<br />

the notes, have something to say with the music and ultimately be<br />

prepared to present that music in a setting outside the practice room.<br />

That was a big challenge I overcame as a high school and college<br />

student, trying to get to the next level where I could start taking on<br />

the traits of what we call a “seasoned or professional player.” In other<br />

words, having control in as many out-of-the-practice-room situations<br />

as possible.<br />

One of the things that has really helped me with intonation is working<br />

with a drone. In high school my orchestra teacher told me that I needed<br />

to work on my intonation. She used to hammer a single note out on<br />

the piano while I played my scales against the pitches she played. She<br />

would yell, “Flat!” Or “Sharp!” at the top of her lungs until I adjusted<br />

properly. These things hurt to hear, but I took it as a challenge. I<br />

worked and worked until I got it so she would never have to say that<br />

again. Nowadays, I’ll play a pitch on a tuner that is relevant to the key<br />

I’m playing in. Sometimes I have to change it as the piece modulates.<br />

If you really want to geek out you can have two tuners playing tones a<br />

fifth apart to strengthen that key foundation. It’s especially important<br />

in playing scales and really learning what playing in tune sounds like.<br />

Not only do you train your ear, but you hear the tendencies of where<br />

certain notes want to lie in a given key. When you start applying that<br />

to pieces, you begin to contemplate which step in the scale you are<br />

playing in a melody and what instrument you are accompanying (or<br />

being accompanied by). Having a drone on is basically recreating the<br />

effect of playing with another instrument, and when I started to do<br />

this I would find my ability to adjust pitch in ensemble playing was<br />

much stronger. That is one thing I really push on my students - it’s not<br />

just about playing the notes, it’s about knowing what’s going on around<br />

you. If you reduce bass playing to “1 on the D string in first position is<br />

E,” and you ask 10 students to execute that, it could potentially sound<br />

like 10 different pitches. Put on an E drone (or an A or a B) and given<br />

that you have decent pitch to begin with, you can find exactly where to<br />

put that note. The students of mine that have a good ear can solve a lot<br />

of intonation issues this way. The other advantage is teaching one how<br />

to play in tune when your strings go out of tune, because you’re not<br />

always basing your idea of a note on its distance from the nut or some<br />

other landmark on the fingerboard. It helps train your left hand and<br />

your ear simultaneously.<br />

Approach to a good position is so crucial. My goal is to make playing<br />

the bass as easy as possible. Even at its easiest, playing the bass can be<br />

uncomfortable and problematic. The human body wasn’t meant to play<br />

the bass. Starting with stance - if you stand, find a comfortable stance<br />

with feet shoulder width apart and knees not locked. If you are sitting<br />

on a stool, position your butt towards the edge of the stool on your sit<br />

bones. Stool height at the highest should allow your right leg to place<br />

the entire sole of your shoe on the ground comfortably without cutting<br />

off blood circulation to your feet. Knees should be 90 degrees apart<br />

with left foot grounded like the right foot or grounded comfortably<br />

on a foot stool or well-placed rung. Begin relaxing your body piece by<br />

piece - relax your shoulders, neck, chin, tongue, eyelids, chest, even<br />

your butt. I think a lot of people carry stress in their butts. Let your<br />

arms hang and analyze what you look like in this resting moment. I try<br />

to point out to my students the gentle curve in the fingers, slight bend<br />

at the elbow, relaxed wrist, thumb that isn’t actively bent or straightened<br />

- these are the features of a healthy approach to the bass. If you<br />

can keep your thumb relaxed when you put it behind the neck, or onto<br />

the frog of the bow, keep curves in your fingers and joints so you’re at<br />

least starting at zero tension. I know people have wildly different bow<br />

grips but I think a good starting point is the same relaxed posture as<br />

your resting hand.<br />

I always have my students thinking of ways to make bass playing<br />

easier. What’s easier than the body at rest? Take what our body does<br />

naturally and lay it on top of the bass. Control over the bass and<br />

consistency all stem from this sense of relaxation - from there, the<br />

priority can now become practicing. These are simple concepts that<br />

perhaps add up to a philosophy. The students I’ve had with a lot of<br />

success have listened to these ideas, but the work they put in and<br />

rewards they have received were really their own.<br />

Someone who plays completely relaxed like Francois Rabbath is an<br />

inspiration as well as virtuoso, but may have trouble doing orchestral<br />

work exclusively. The fundamental of relaxation is not practical in all<br />

settings - you couldn’t play a true orchestral fortissimo spicatto stroke<br />

with spaghetti arms. If you aren’t approaching the stroke with extra<br />

tension, you can activate the muscle where necessary to make the<br />

sound you want. This is where Hal Robinson is such a great example<br />

- he has eliminated any extraneous tension and can also provide as<br />

much power as is necessary for a particular passage. I would never call<br />

Hal’s playing rigid in any regard, but there are certain parts of his body<br />

that at the moment of a stroke become firm, and then release when<br />

they’re no longer needed.<br />

Figuring out how to torque into the string, using the rotation of your<br />

forearm along with hand and index finger (pronation), applying your<br />

bow and arm weight to the string, using your left hand and forearm<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

7

to pivot - these things should not cause you<br />

to tighten your neck, your face, or any other<br />

part of your body. You have to dissect the<br />

motion and see what is helping you execute it<br />

and what isn’t. Good players are able to adjust<br />

their body to the needs of a passage, a bow<br />

stroke, or a musical requirement - they aren’t<br />

“tense” or “loose” all the time. You have to be<br />

able to turn on and off the mechanisms.<br />

Searching for a bass<br />

My hunt for an instrument took a long time. I<br />

had a nice English bass that was a wonderful<br />

tool as well as being in beautiful condition.<br />

It helped me through college and helped me<br />

win a couple of auditions. After 8 years in a<br />

professional orchestra I wanted to take that<br />

step up to a higher caliber instrument, so I<br />

sold the English bass on the assumption that<br />

I would find its replacement quickly. It took<br />

me 3 years to find the bass that I’m playing<br />

now. I played a lot of different basses along<br />

the way. Aaron Robertson is a dear friend of<br />

mine, whom I met around age 18 at Domaine<br />

Forget, about 19 years ago. After I sold my<br />

English bass, Aaron graciously allowed me<br />

to play on his very fine Italian bass while I<br />

searched. It was very, very good but at the<br />

same time I got a bit spoiled. In a world of<br />

incredibly expensive instruments, it makes for<br />

some frustrating times. The market for fine<br />

basses is very tight because everybody owns<br />

them and no one wants to sell them. Every<br />

once in a while, there will be the miraculous<br />

“sleeping beauty bass in a closet” that surfaces<br />

but mostly they are few and far between.<br />

There are always buyers ready and waiting for<br />

something to become available.<br />

3 years went by waiting and trying various<br />

instruments. Then Aaron contacted me to<br />

let me know he had something I might want.<br />

He sent it up to Seattle and when I opened<br />

the shipping trunk I knew it was the one. At<br />

first this fine Italian bass sounded good, but<br />

Aaron and I knew we could get more out of<br />

the bass. I could tell that some small adjustments<br />

would let it get there. Robertsons had<br />

done a fabulous job on it. The bass looked<br />

beautiful and sounded good. The bass bar<br />

needed adjustment, and Aaron had suggested<br />

a different bridge size. It turned out to be only<br />

a few tweaks away from humming the way we<br />

thought it would. It was a really long search,<br />

but in the end it was completely worth it.<br />

My advice in a bass search is that patience is<br />

your greatest virtue. The end goal is to find<br />

the bass that will thoroughly satisfy. Aaron<br />

helping me be patient and find the instrument<br />

was a huge asset to me in that time.<br />

The takeaway<br />

I’ve been doing long bow open string exercises<br />

since my senior year in high school. I<br />

went into great detail about practicing the<br />

open strings since then. That is one thing I’ve<br />

been doing every day for the last 20 years or<br />

so. Take the time at the beginning of every<br />

practice session, even if you don’t have time<br />

to do your full hour of scales and things will<br />

do so much for your playing. If you think<br />

of your right arm as your voice, the priority<br />

becomes clear. The left hand then can add to<br />

that expressive capability. The first question<br />

an audition committee asks is “What type of<br />

voice does this person have?” It’s the vehicle<br />

for communicating your expressive ideas. I<br />

prioritize right hand first, left hand second.<br />

It’s not a matter of the right hand being more<br />

important, but it gets more attention at the<br />

beginning my daily practicing to be sure.<br />

Going from really slow strokes to progressively<br />

faster, only focusing on the open strings<br />

without the left hand, will set the tone for the<br />

whole practice session. Having a controlled<br />

right hand and clear sound production allows<br />

you to then devote more time and attention<br />

exclusively to the left hand. You need to have<br />

a voice before you start moving the notes<br />

around. ■<br />

Faculty<br />

terell Stafford, Chair,<br />

Instrumental Studies Department<br />

Eduard Schmieder,<br />

L. H. Carnell Professor of Violin,<br />

Artistic Director for Strings<br />

luis Biava*, Music Director,<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

Double Bass<br />

Joseph conyers*<br />

John Hood*<br />

Robert Kesselman*<br />

anne Peterson<br />

*Current member of<br />

The Philadelphia Orchestra<br />

PRogRamS<br />

B.m.: Performance<br />

B.m.: composition<br />

B.m.: music Education<br />

B.m.: music History<br />

B.m.: music theory<br />

B.m.: music therapy<br />

m.m.: Performance<br />

m.m.: composition<br />

m.m.: music Education<br />

m.m.: music History<br />

m.m.: music theory<br />

m.m.: String Pedagogy<br />

m.m.t.: music therapy<br />

D.m.a.: Performance<br />

Ph.D.: music Education<br />

Ph.D.: music therapy<br />

Professional Studies certificate<br />

EnSEmBlE oPPoRtunitiES<br />

> temple university Symphony orchestra<br />

> opera orchestra<br />

> Sinfonia chamber orchestra<br />

> contemporary music Ensemble<br />

> Early music Ensemble<br />

> String chamber Ensembles<br />

For more information, please contact:<br />

215-204-6810 or music@temple.edu<br />

www.temple.edu/boyer<br />

8 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

Philadelphia, PA

Spotlight<br />

cleveland Orchestra Bass Section<br />

The Cleveland Orchestra is in many ways a peerless orchestra in the<br />

United States. As the smallest city to maintain a “Big Five” orchestra<br />

(a fabled rank that also includes Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and<br />

New York), it is also notable for sustaining an extremely high level<br />

of musicianship and artistry in spite of extremely trying economic<br />

realities in its community. Forever indebted to the legacy established<br />

by George Szell beginning in the 1940s, the Cleveland Orchestra<br />

continues to produce definitive recordings and scintillating performances<br />

heard in Cleveland and at many performances that the<br />

orchestra undertakes on tour throughout the world.<br />

Speak to any bassist from the Baby Boomer generation, and they<br />

will likely cite recordings by Cleveland and Szell as some of the most<br />

influential and impassioned they have ever heard. More specifically,<br />

they may say, the recordings of Mozart, Haydn, early Beethoven<br />

are almost unique in their clarity. Section bassist Derek Zadinsky<br />

identifies some of the advantages of the orchestra’s home venue,<br />

Severance Hall: “It is very easy for us to hear every player in the<br />

section onstage, so any discrepancies always become immediately<br />

clear.” At a time when the Philadelphia Orchestra made recordings in<br />

gymnasiums, TCO was finely tuning the most delicate inner workings<br />

of the ensemble. “The blend of sound in this ensemble is part of what<br />

makes the Cleveland Orchestra so unique,” says Zadinsky. “Playing in<br />

this orchestra can sometimes feel more like playing chamber music<br />

because our principal players are so easy to follow.”<br />

• Maestro George Szell carefully crafting the end of Beethoven<br />

Symphony 5, Mvmt 2<br />

There is a tremendous range of color and dynamics in this orchestra,<br />

which many have attributed to Severance Hall. Some whispers even<br />

implicate the practice rooms at the nearby Cleveland Institute of<br />

Music, where the live acoustics of the rooms help attune aspiring<br />

students to the resonant and intimate nature of Severance. As a<br />

graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, Derek Zadinsky certainly<br />

noticed a transition. “I quickly found that the kind of playing that<br />

works best in Severance Hall is different from what I had been familiar<br />

with. The smaller size and resonant acoustics of the hall allow the<br />

section and orchestra to effectively play down to the quietest whisper.”<br />

While many auditioning bassists may take pains to attempt to recreate<br />

or simulate the playing style of a committee they are playing for, it<br />

is important to note Zadinsky’s heritage and current employer. No<br />

amount of second-guessing can substitute for confident and wellprepared<br />

playing, which Derek brought to his 2011 audition.<br />

That said, the fundamental philosophy of the section, according to<br />

Zadinsky is to “pay very close attention to all the composer’s markings,<br />

and frequently discuss exact strokes and rhythmic placement.” When<br />

tackling the immense complexity of Mahler or the deceptive simplicity<br />

of Mozart, Cleveland’s bass section places the highest priority on<br />

rhythmic unity and precision. Veteran player Scott Haigh says, “I think<br />

our section is committed to playing a vital function within the orchestra,<br />

but not a dominating one. Clarity, beautiful intonation, good<br />

rhythm, and balance with the other section is our style, yet we can<br />

rock out a section solo when called for.” Haigh also enjoys the variety<br />

of repertoire the orchestra plays, which allows them to maintain their<br />

flexibility. “Over the past few years I have enjoyed Baroque music in<br />

a more authentic style, but still using a modern orchestra setup. The<br />

conductors who specialize in this style are so much better than they<br />

used to be in working with modern orchestras. They seem to get the<br />

right string sound without having to change to gut strings, etc.” While<br />

many orchestras deal with uncooperative or difficult acoustics in their<br />

home concert space, the Cleveland Orchestra has developed its unique<br />

sonic pallette from playing in one of the best acoustics in the world.<br />

Severance Hall is certainly not the only ally of this venerable orchestra.<br />

The Cleveland Orchestra is notable for one of the most extensive touring<br />

schedules of any major orchestra, especially from a city the size<br />

of Cleveland. While local citizens have much to be proud of, patrons<br />

from New York to Nebraska have opportunities to see performances.<br />

The orchestra also performs several weeks in the winter in Miami<br />

(no small benefit to musicians in notoriously cold Cleveland!), which<br />

Zadinsky describes as “coming to feel like a second home. The world<br />

is our oyster!” The orchestra’s challenge on these tours is to maintain<br />

the standard of precision while accommodating the huge variety of<br />

halls in which they play for perhaps one night only. Says Zadinsky<br />

“We are able to perform concerts that are equally musically compelling<br />

in a wide range of acoustics, from Carnegie Hall in New York to<br />

the Musikverein in Vienna.” Each concert is unique and exciting from<br />

many perspectives.<br />

No article on the Cleveland Orchestra bass section would be complete<br />

without some links to videos. While there are not many videos of the<br />

orchestra performing live, the immortal recording legacy of the group<br />

is preserved well on the internet.<br />

• Interview with Max Dimoff over a recording of<br />

Bach Cello Suite 1 - Minuets 1 and 2<br />

• The Cleveland Orchestra playing Richard Strauss’ Ein<br />

Heldenleben - this video begins just before the famous #77<br />

excerpt. Minute marker 1 has a great shot of Peter Seymour,<br />

frequentsection guest and founding member of the Project Trio<br />

playing all over the bass! 1:25 is a great section shot as well.<br />

• A more complete rehearsal of Beethoven’s 5 th Symphony with Szell.<br />

The information and process on display here are incredible<br />

resources to anyone aspiring to be an orchestra player<br />

or a conductor.<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

9

Tim Dilenschneider is a 2014 graduate<br />

of the Curtis Institute of Music and a<br />

newly appointed fellow of the New World<br />

Symphony Orchestra. He is a substitute<br />

bass for the Philadelphia Orchestra and<br />

a Wabass Institute alum.<br />

UP &<br />

COMER<br />

Tim Dilenschneider<br />

10 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

Describe your background<br />

My teachers, who have supported me throughout my career, have<br />

been instrumental in my development as a musician. Hal Robinson<br />

and Edgar Meyer at Curtis, Ranaan Meyer during high school, and<br />

even my elementary school teacher Mrs. Zoshak, have all helped me<br />

so much.<br />

I started playing the bass when I was eight years old. My third grade<br />

teacher Mrs. Zoshak started me on bass and encouraged me, even<br />

after I broke the first school instrument I was using. Fortunately, she<br />

replaced it right away so I could keep playing! I remember the day in<br />

third grade when my parents and I first learned about the Curtis Institute<br />

of Music, a school we’d never heard of before. Mrs. Zoshak saw<br />

something in my early playing and mentioned Curtis to my parents<br />

and me. She’s followed me throughout my musical career, and I’ve<br />

really appreciated her continued support. She recently saw me perform<br />

with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Carnegie Hall and even came to<br />

my final performance at the Curtis Institute of Music. These types of<br />

relationships are really important.<br />

At this point in my career, I consider Ranaan Meyer, Hal Robinson,<br />

and Edgar Meyer to have been my life changing teachers. They have<br />

driven me to be a better musician, and seeing them perform, teach,<br />

and continue to learn themselves, gives me perspective on what being<br />

a musician is all about. Growth comes not only from experience, but<br />

also sharing the experience with others. Without their knowledge<br />

and support, I wouldn’t be half the musician I am today.<br />

Do you have specific memories of<br />

breakthrough moments as a musician?<br />

Three major moments come to mind as highlights of my career. As<br />

part of Curtis On Tour, we opened for the Dresden Music Festival<br />

in Germany in May 2012. We performed an all-Brahms program in<br />

Die Frauenkirche, the only church to survive the shelling of Dresden<br />

in World War II. It was amazing just to play in this historical church.<br />

Playing Brahms Academic Festival Overture, the Double Concerto,<br />

and the Symphony No. 2 under Robert Spano was an incredibly<br />

powerful experience. That trip was my first time leaving the country,<br />

which makes it very memorable. I remember vividly being on stage<br />

playing Brahms 2, looking out into the audience which was only a<br />

few feet away. I was looking out while we were playing, smiling at<br />

someone and seeing them smile back. The audience was on the edge<br />

of their seats listening intensely to the music. It was great to see the<br />

musical appreciation that is so strong there, and it made playing so<br />

much more fun.<br />

The other memorable experience was back in 2007 at Interlochen,<br />

when I was in high school. This was the moment that I realized that<br />

playing in orchestra could be so much fun. I was playing in the World<br />

Youth Symphony Orchestra under Jung-Ho Pak, and the repertoire<br />

was Mahler’s Symphony No. 2. It was my first time ever playing a<br />

major symphony, one that I spent a long time preparing the bass part<br />

and making sure I had the music down cold. Usually at Interlochen<br />

you rehearse something for two weeks and perform it, but for this<br />

work we spent four weeks rehearsing. It was a lot of hard work that<br />

really paid off. I remember a moment when there was a Grand<br />

Pause and everything echoed through the hall. I thought that was so<br />

awesome and I knew then that I wanted to do that forever. This took<br />

my personal enjoyment to a whole new level. The fact that you can<br />

have a career playing incredible music still excites and motivates me.<br />

My final and most recent memorable experience was my first<br />

performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Performing with the<br />

Philadelphia Orchestra has always been a goal of mine ever since I<br />

started playing the bass. I grew up in the area and have been going<br />

to see them since I was a young child. I was really excited to work<br />

alongside all the talented members of the orchestra especially my<br />

teacher, Hal Robinson. It was truly an unforgettable experience and<br />

I learned a lot in the process. I was fortunate to play under the baton<br />

of Yannick Nezet-Seguin, performing Bruckner’s 9th Symphony and<br />

Barber’s Adagio for Strings, which really showcased the unbelievable<br />

string sound of the Philadelphia Orchestra.<br />

Describe your warm-up routine<br />

Personally I’m not really one to have a set warm-up routine. I was<br />

never really big on scales, never too fond of etudes, and neither were<br />

my teachers growing up. When I first pick up the bass for the day,<br />

many times I will just experiment on the bass. I’ll throw on a drone,<br />

or use my open D string, and warm up my fingers. I improvise a bit,<br />

get the blood flowing. It’s nice to walk into a practice room without<br />

feeling like you have to be completely serious right away. Once I start<br />

to open up my excerpts or solos, whatever I’m working on at the time,<br />

I first attack those sections or moments I know that I struggle with. I<br />

like to start off my practice sessions breaking trouble spots down to<br />

their simplest forms, just the left or right hand to start, maybe playing<br />

a passage on one note, working on the bow stroke, or slowly adding<br />

speed. I don’t have a set time for my warm-up, and it changes day to<br />

day based on the way my practice went the day before. If I discovered a<br />

new trouble spot the day before, where perhaps my right hand isn’t as<br />

clear as my left, I’ll break it down at the beginning of the next day and<br />

make sure I separate hands to work it back into context.<br />

Any specific thoughts on left hand<br />

approaches? Thumb position or otherwise?<br />

I have messed around with Edgar Meyer’s concepts in thumb position.<br />

I have found it helpful in a lot of situations and not in others. I found<br />

that if I zoned in on the idea that you need to use some strange fancy<br />

fingering to impress people, it was counterproductive. I remember<br />

when I came to Curtis, and I would always feel like I needed to play a<br />

certain way or incorporate the “thumbage” as Hal and Edgar call it. I<br />

found that sometimes I was making it harder on myself to try and do<br />

complicated fingerings when a simpler solution existed. Everyone will<br />

play a passage differently based on hand size or body build. “Thumbage”<br />

is a great tool to have, and sometimes it can solve tricky problems.<br />

I think it’s a personal thing and as you develop your technique you<br />

learn when and how to use techniques to get the best outcome.<br />

What do you hope to be doing<br />

10 years in the future?<br />

It’s my dream to play in a high caliber professional orchestra. I’ve<br />

always loved being in orchestra, playing on stage with a big section<br />

and having a great time playing music. There’s nothing as rewarding<br />

as working with extremely gifted friends and colleagues. On top of<br />

playing in an orchestra, I would really enjoy giving back and helping<br />

the next generation of bass players by teaching. It’s something I’ve<br />

always wanted to do and I’ve been very lucky to have such great<br />

teachers in my life helping me. I feel like I need to give back by<br />

creating another generation of students who will pass that good<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 11

Essential excerpts from the<br />

Orchestral Literature<br />

Meticulously edited with fingerings, bowings, and<br />

philosophical concepts from Hal Robinson, Principal<br />

Bass of the Philadelphia Orchestra. On Sale Now.<br />

Honed and refined<br />

for 25 years in<br />

Robinson's studio<br />

Available<br />

exclusively through<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Publishing<br />

The Quad <br />

Volume 1 <br />

Edited by Hal Robinson<br />

© 2014 Ranaan Meyer Entertainment<br />

Featured in<br />

Volume 1:<br />

R. Strauss<br />

Don Juan<br />

Mozart<br />

Symphony No. 35<br />

Beethoven<br />

Symphony No. 9<br />

Orchestral Solos<br />

Smetana<br />

Bartered Bride<br />

will on as well. It still blows my mind to think that I can make a<br />

living performing. I feel so lucky when I have the opportunity to<br />

“go to work”.<br />

How have you chosen<br />

which auditions to take?<br />

I’m still relatively new to taking professional auditions. I’ve only<br />

taken a few professional and/or substitute auditions. Now that I’ve<br />

graduated, I’m looking at all the positions as they become available. I<br />

make sure before deciding to take an audition that I have an adequate<br />

amount of time to prepare. If it’s right in the middle of a lot of<br />

obligations that I can’t move or eliminate, I would rather not take the<br />

audition. When I choose to take something on, I like to give it my all<br />

and not cram it into an already busy schedule and hope for the best.<br />

That’s not a good formula for success.<br />

What’s your approach to<br />

dealing with nerves?<br />

Nerves are something I continue to struggle with to this day. I’m<br />

not sure they’ll ever entirely go away. Since I’m new to professional<br />

auditions, I’m sure there are more struggles ahead, but each experience<br />

helps me grow and learn more about my tendencies. One way I work<br />

on this issue is putting myself out there by volunteering to play for<br />

other people in bass classes, or performing a piece on a collaborative<br />

recital, or asking fellow musicians to listen in the practice room. The<br />

most important thing is to play the repertoire you’re struggling with<br />

for others so you have some experience. With experience comes<br />

confidence, and I believe confidence is the key to settling nerves.<br />

The auditions I’ve had the most success with, tend to be less formal.<br />

When the committee is visible, and perhaps talking to you before<br />

you play, I feel much more comfortable. I feel like being able to speak<br />

to someone before playing has always helped me. Even answering<br />

simple questions like where I went to school, what instrument I’m<br />

playing on - talking helps me shake out the nerves, and allows me<br />

to feel more like myself. This isn’t the case with most professional<br />

auditions so getting more experience with these will be important.<br />

I’ve already learned a lot in the first few I’ve taken.<br />

Do you want to discuss beta blockers?<br />

I have tried beta blockers, and I definitely don’t see anything wrong<br />

with people using them. I have used them in settings like recitals or<br />

concerts for which I’m particularly stressed. I don’t think that they<br />

create a performance advantage. I think that they help more with<br />

settling nerves and giving you the opportunity to perform at your<br />

own personal best. It’s not a musical steroid that allows you to play<br />

10 times better than you do in the practice room, it just makes you<br />

capable of showing what you can do. I’m all for them!<br />

When it comes to auditions, are there<br />

any solos or excerpts you hope<br />

you’ll get to play?<br />

I love being able to play pretty much any excerpt where I can express<br />

myself as a musician, rather than being a simple metronome. I like<br />

the excerpts that I can mess around with musically, and make my<br />

own. The Beethoven 9 recits, Bottesini Concerto No. 2, Otello soli -<br />

12 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

Exercises in Shifting <strong>Hand</strong>-Settings and<br />

Raising Awareness of Non-Playing Fingers<br />

Major and minor triads: move symetrical Major and minor triad fingerings by half steps.<br />

Maintain the structure of hand-setting trough the friction of shifting. Practice these ascending<br />

and descending in various combinations: low-mid-high-mid; HMLM, etc.<br />

<br />

<br />

3<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

<br />

3<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

Nicholas Walker<br />

Shifting chromatic Major and minor triads.<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3 +<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3 +<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

Major triad<br />

3 + 1 + 3<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

3 + etc.<br />

II<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

+<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

II<br />

3 +<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3 +<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

+ 1 + 3<br />

<br />

<br />

I II<br />

<br />

+ <br />

etc.<br />

Dominant Harmony: diminished seven symetrical fingerings. Maintain<br />

the structure of hand-setting trough the friction of shifting. Also play these<br />

exercises in close position (chromatic position), with 2 in place of 1 and 3<br />

in place of 2.<br />

<br />

(alternate fingering:)<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

I<br />

II<br />

<br />

<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

I<br />

II 3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

Variation I: Shift: + replaces 2 ascending, 2 replaces + descending. Match pitch on the same string with a new finger.<br />

+<br />

I<br />

1<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

Variation II: Shift: + replaces 2 ascending, 2 replaces + descending. Match pitch on a different string with a new finger.<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

+<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

2<br />

I<br />

II<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

I<br />

II<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

+ 2<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2 + 1<br />

<br />

II<br />

Variation III: Shift: + replaces 2 ascending, 2 replaces + descending. New pitch (with +) after shift.<br />

+<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+ 2<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 2<br />

<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

+<br />

<br />

Variation IV: Shift: + replaces 2 ascending, 2 replaces + descending. New pitch (with 2 ascending and with 1 descending) after shift.<br />

2<br />

<br />

<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1 + 2<br />

<br />

II I II I<br />

Copyright © 2010<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

<br />

I<br />

2 +<br />

<br />

Continued on Page 15<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 13

these are all great examples of what I hope I’ll get asked to play in an<br />

audition because everybody plays them differently. It’s a great opportunity<br />

to show what I’m capable of as a musician. Additional excerpts<br />

that I enjoy playing are Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4 movements 1<br />

and 4, Brahms Symphony No. 1 movement 1, Mahler Symphony No.<br />

2 movement 1, and Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra Variation<br />

H. Right now I’m working on the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra list.<br />

I’m really enjoying learning and working on some opera excerpts that<br />

I had never known before.<br />

How about excerpts you really don’t like?<br />

Some of my least favorite excerpts to play would include the Haydn<br />

88 4 th movement, and Symphonie Fantastique movement 1. Those<br />

are some of the excerpts that I don’t enjoy playing as much. Lists of<br />

complete works still terrify me a bit, because there are no specified<br />

excerpts and I feel like the committee may be trying to throw a few<br />

curveballs. I get concerned that the committee is trying to cut people<br />

from the audition rather than encouraging people to do their best. I<br />

hope for an audition environment where people are rooting for the<br />

candidates that will add to the quality of the section.<br />

How do you find a great teacher?<br />

Branch out through summer festivals - I went to Interlochen, BUTI,<br />

Aspen, PMF, Wabass Institute, and Strings International. Cast a wide<br />

net. I took lessons from as many teachers as I could. This process lasted<br />

from the end of middle school through high school. Once you find<br />

someone you like, don’t be afraid to approach them about your desire<br />

to work with them, or get more lessons from them. You have to put<br />

yourself out there sometimes to find your way into someone’s studio,<br />

but the guidance and the bond you form can shape your career.<br />

Final thoughts?<br />

Take in everything you can from your teachers. They’re your best<br />

source of information and should be your best friends. Supportive<br />

parents make things possible and great teachers develop you as<br />

a musician. ■<br />

Ranaan Meyer Publishing<br />

Hal Robinson The Quad Volume 1<br />

Available Now<br />

Harvie S 10 Duets<br />

Tchaikovsky/arr. Timothy Pitts Souvenir de Florence<br />

Ranaan Meyer Originals, including Just One Dance,<br />

Emily, and My Irish Mother<br />

Coming Soon: Transcriptions, originals, and chamber<br />

music for double bass and other instruments.<br />

14 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

2<br />

Tonic Harmony: minor seven/major six fingerings. Maintain the<br />

structure of hand setting trough the friction of shifting.<br />

<br />

3<br />

minor triad<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

3<br />

1<br />

Major triad<br />

+<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

4-3 triad<br />

3<br />

2<br />

4-2 triad<br />

+<br />

Variation V: Shift: + replaces 3 ascending, 3 replaces + descending. Match pitch on the same string with a new finger.<br />

<br />

+<br />

1<br />

+<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

+<br />

<br />

3 + 2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3 + 2<br />

<br />

<br />

I II I II I II I II I<br />

I II I<br />

Variation VI: Shift: + replaces 3 ascending, 3 replaces + descending. Match pitch on a different string with a new finger.<br />

+<br />

3 3 + 2 II<br />

<br />

+<br />

2<br />

3 + <br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3 + 2<br />

<br />

II I II I II I II I<br />

I<br />

Variation VII: Shift: + replaces 3 ascending, 3 replaces + descending. New pitch (with +) after shift.<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

2<br />

<br />

+<br />

3 + + 3 + 2 II<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

+ 2 <br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

+ 2 + 3<br />

+ 2<br />

<br />

3 + 2 +<br />

<br />

II<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

Variation VIII: Shift: + replaces 3 ascending, 3 replaces + descending. New pitch (with 2 ascending and with 2 or 1 descending) after shift.<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

3<br />

<br />

<br />

3<br />

<br />

I<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

3<br />

+ <br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

3<br />

+ 2 <br />

II<br />

+<br />

3 + 2 + 2 +<br />

I II I II I<br />

3 + 2 <br />

II<br />

+<br />

+<br />

3 + 1 <br />

I II I<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

1<br />

<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

3<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

Dominant to Tonic Harmony: diminished seven symetrical fingerings resolve to tonic hand setings. Remember to prepare the new hand-setting<br />

arrival finger on/in the string within the current hand-setting before the shift to the new hand-setting. Note this is the same diminished arpeggio<br />

as that on the previous page, though here requires a different spelling.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

Listen for this scale<br />

minor triad<br />

3<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

3<br />

+<br />

1<br />

dim triad<br />

2<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

4-3 triad<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

Variation IX: Shifting dominant to tonic hand-settings - LMHL (low mid high low). The lowest note of each triad forms the scale).<br />

Also play these variations LMHM, HMLH, HMLM, MHML, MLMH, etc. and experiment with mixing them together in one variation.<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

1 + 2 1 1 +<br />

<br />

<br />

II I II I<br />

dim triad<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

3<br />

<br />

minor triad<br />

1 + 2 1 1 +<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

II I II I<br />

4-2 triad<br />

dim triad<br />

3 + 2 3 2<br />

+ 1<br />

II<br />

I<br />

3 +<br />

II<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

II<br />

<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

1<br />

etc.<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

dim triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

+<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

I<br />

I<br />

4-3 triad<br />

3<br />

Major triad<br />

dim triad<br />

2 1 1 + 3 1 1 +<br />

<br />

<br />

I II I<br />

+ 2 1<br />

<br />

+ 2<br />

<br />

II<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

<br />

I<br />

II<br />

I<br />

2 1<br />

<br />

II<br />

4-3 triad<br />

2<br />

<br />

Major triad Major triad dim triad<br />

1 + 3 1 3<br />

+ 1 3 2<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

2<br />

<br />

<br />

Major triad<br />

I<br />

+<br />

I<br />

dim triad<br />

3<br />

2<br />

II<br />

2<br />

+ 1<br />

dim triad<br />

1<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

1 + 2 3<br />

<br />

+ 1 + 2<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

II I<br />

<br />

II I II<br />

II<br />

I<br />

+ 2 1<br />

<br />

<br />

I<br />

minor triad<br />

II<br />

<br />

4-2 triad<br />

3<br />

+<br />

2<br />

4-2 triad<br />

2<br />

+<br />

I<br />

3 2<br />

<br />

2 3 + 1 3 2 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

+<br />

I<br />

minor triad<br />

3<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

II<br />

+<br />

<br />

I<br />

I<br />

2<br />

dim triad<br />

<br />

<br />

dim triad<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

II<br />

II<br />

+<br />

I<br />

II<br />

2<br />

<br />

I<br />

<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 15

Exercise in Estabishing Three Different <strong>Hand</strong>-Settings Centering on Each Pitch of a C Major Scale: Be certain each hand-setting is<br />

fully prepared before continuing to the second note of each slur. Experiment with playing the slured pitches with measured, separate bows,<br />

as well as a grace note flourish around the target pitch. Match the target pitches from one grouping to another between hand settings.<br />

Play this exercise in all keys. To augment this exercise, add diatonic pitches on the 3rd string as well.<br />

3<br />

<br />

1 + 1 3 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-2 1 + 1 2 + 1 2 1 + 2 1 + 1 2<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

3 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-+ 1 3 + 1 3<br />

+ 3 1 + 1<br />

<br />

1 <br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

1 + 1 3 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-3 1 + 1 3 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 + 1 3<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-1+<br />

<br />

<br />

1 3 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-+ 1 2 + 1 3<br />

+ 2 1 + 1<br />

<br />

1 <br />

<br />

1 + 1 2 + 1<br />

2 1 + 1<br />

<br />

3 1 + <br />

-3 1 + 1 3 + 1 3<br />

+ 3 1 + 1 3<br />

<br />

1 <br />

-1+<br />

<br />

<br />

1 2 + 1<br />

2 1 + 1<br />

3 1 + <br />

-+ 1 3 +<br />

1 + 1<br />

1 3 1 + 3 <br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

1 1 3 +<br />

1 + 1<br />

+ 1 3 1 + 3 <br />

<br />

<br />

-2 1<br />

<br />

+ 1 2 + 1<br />

2 1 + 1 2<br />

-1<br />

2 1 + <br />

1 3 +<br />

1 + 1<br />

+ 1 3 1 + 3 <br />

<br />

<br />

-+<br />

3<br />

+ 1<br />

1 + 1 3 1 + 3 1 <br />

<br />

1<br />

1 3<br />

-+ 1<br />

+ -+ 1 3 1 + 3 1 <br />

-3 1 +<br />

<br />

1 3 +<br />

1 + 1 3<br />

2 3 2 + 3 <br />

-1+ 1 3<br />

-+ 1 3 1 + 3 1 -+ 1<br />

<br />

-+ 1<br />

(* use 3rd or 2nd finger)<br />

<br />

+ 1 3 + 1 + 1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

3<br />

2<br />

2<br />

1 <br />

<br />

1 + 1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

+ 1 3<br />

2<br />

<br />

1 <br />

+<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1 + 1<br />

-3<br />

2<br />

1 + 1 3 -+ 1 3 1 + 3 1 -+ 1 3<br />

2 2 2 2<br />

<br />

<br />

-1+<br />

<br />

<br />

1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

+ 1 3<br />

+<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1 + 1<br />

2<br />

1 <br />

-+ 1 2 + 1<br />

2 1 + 1<br />

2 1 + <br />

<br />

1<br />

1 2<br />

+ 1<br />

+ 1<br />

+ + 1 2 1 + 2 1 -3 2<br />

1 1 3 2 1 + 3 2<br />

<br />

3<br />

2<br />

+<br />

1<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

-1+ 1 2<br />

+ 1 2 1 + 2 1 + 1<br />

-+ 1 3 + 2<br />

1 3 2 1 + 3 1 2<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

1<br />

1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

+ 1<br />

+ + 1 3 1 2<br />

+ 32 1 <br />

<br />

<br />

-2 1 + 1<br />

<br />

2 +<br />

1 + 1 2<br />

1 2 1 + 2 <br />

<br />

<br />

1 3<br />

+ 1<br />

-1+ 2<br />

+ 1 3 2 1 + 32 1 <br />

<br />

<br />

-+ <br />

1 3<br />

2<br />

+ 1 3 2 1 + 32 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

16 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

4<br />

Ex. A Rabbath's Crab Approach<br />

xxxx<br />

Nicholas Walker<br />

& Rex Surany<br />

<br />

+ 1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

1 2 3 +<br />

<br />

<br />

3 2 1 + 3 2 1<br />

+ 3 2 1<br />

+ 3 2 1<br />

<br />

+ 3 2 1<br />

+ 3 2 1 + 3 2 1 + 3<br />

<br />

2 1 + 3<br />

2 1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

Ex. B, 2-2 , +-+<br />

<br />

<br />

+ 1<br />

<br />

2 -2 +<br />

<br />

x xxxx<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

1 2 -2 +<br />

<br />

<br />

2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2 1 + -+ 2<br />

<br />

<br />

1 + -+ 2<br />

1 + -+ 1<br />

<br />

<br />

Ex. C, 1-1<br />

xxxx xxxx<br />

<br />

+ 1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

1 -1 2 +<br />

<br />

<br />

2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2 1 -1 + 2<br />

<br />

<br />

1 -1 + 2<br />

1 -1 + 1<br />

<br />

<br />

xxxx x<br />

Ex. D, +-+ , 2-2<br />

<br />

<br />

+ -+<br />