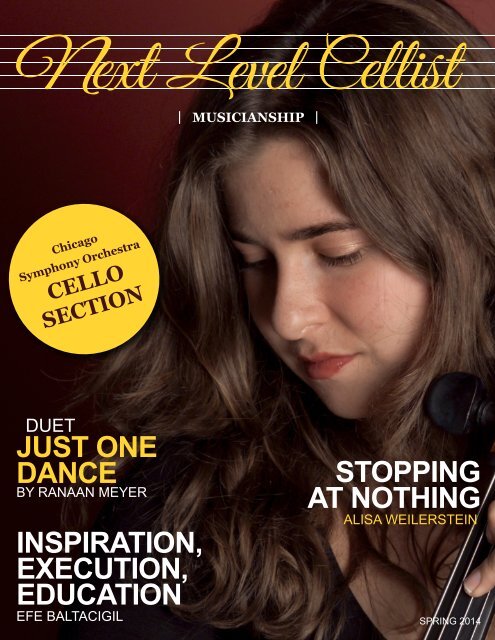

Next Level Cellist Musicality Issue

Featuring articles by Alisa Weilerstein and Efe Baltacigil, a spotlight on the Chicago Symphony Cello section, and a duet by Ranaan Meyer

Featuring articles by Alisa Weilerstein and Efe Baltacigil, a spotlight on the Chicago Symphony Cello section, and a duet by Ranaan Meyer

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

| MUSICIANSHIP |<br />

Chicago<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

CELLO<br />

SECTION<br />

DUET<br />

JUST ONE<br />

DANCE<br />

BY RANAAN MEYER<br />

INSPIRATION,<br />

EXECUTION,<br />

EDUCATION<br />

EFE BALTACIGIL<br />

STOPPING<br />

AT NOTHING<br />

ALISA WEILERSTEIN<br />

SPRING 2014

Contents<br />

Spring 2014<br />

Feature Story<br />

5 Just One Dance<br />

RANAAN MEYER<br />

6 Stopping at Nothing<br />

ALISA WEILERSTEIN<br />

10 Spotlight: Chicago Symphony Orchestra<br />

Cello Section<br />

11 Inspiration, Execution, Education<br />

EFE BALTACIGIL<br />

Contributors<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

PUBLISHER / FOUNDER<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

EDITOR / SALES<br />

Karen Han<br />

LAYOUT DESIGNER<br />

2 NOV/DEC SPRING 2014 2013 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST BASSIST

Publisher’s Note<br />

What an incredible feeling it is to be writing to you, the<br />

newest members of the <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals family. I<br />

started <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Bassist a year ago to bring double<br />

bass players together, and to help share wisdom and<br />

experience with everybody. The goal of <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

Journals is really to create a community among people<br />

who have one very important thing in common.<br />

For cellists, it’s playing one of the most versatile and beautiful instruments<br />

humanity has ever created. I am personally so excited to spend time speaking<br />

with, learning from, and even inspiring cellists, our brothers and sisters from<br />

the low end!<br />

Our first issue is about musicality - the art of conveying our emotions and<br />

statements through our instruments, the essence of why we all put in the long<br />

hours and spend so much time focused on self-improvement. Hopefully, we<br />

can all remember that very first moment when we got swept away by the music<br />

we were playing, fully committing to the sound of the group and the notes<br />

coming out of the instrument. It’s the adrenaline of an amazing performance,<br />

or the quiet pleasure of accomplishing something we knew was impossible only<br />

weeks ago.<br />

I am so excited by the content of this journal. Alisa Weilerstein has had such<br />

a stellar career, and her explanation of the “impulse” is information that is of<br />

critical importance to every single musician. While not everyone shares her<br />

incredible musical background, we can all benefit from the wisdom of her<br />

perspective. Efe Baltacigil, a great friend and an unbelievable cellist, shares his<br />

thoughts on the fundamental building blocks of musical sensitivity, as well as<br />

the story of a musical family that is making quite an impression on the world.<br />

We are also including a regular feature from the bass journal, a spotlight on a<br />

great cello section. This time around, we heard from the Chicago Symphony’s<br />

Brant Taylor on his 16 years as a member of the cello section which is an<br />

11-person force of nature! As we all aspire to play with the best musicians<br />

we can find, it helps to know that life at the top is wonderful and fulfilling.<br />

I am so excited to be including a page of my latest composition, a duet for cello<br />

and bass called Just One Dance. As a celebration of the launch of this journal, I<br />

hope this duet will unite the low strings and allow us all to share in the wisdom<br />

that every player brings to the table. I am truly honored to be in the company<br />

of so many new people in the cello world - may we all inspire one another and<br />

never lose the impulse!<br />

RANAAN MEYER<br />

Publisher <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

3

JOSEPH HILL RAYMOND J. MELANSON JOSEPH CHAROTTE-MILLOT ANNE COLE<br />

NICOLAS GILLES CARLO ANTONIO TESTORE ANTOINE CAUCHE DIDIER NICOLAS<br />

BOYD POULSEN PAUL HART JAMES B. MIN CARLO CARLETTI GIOVANNI TONONI<br />

GUY COLE RENATO SCROLLAVEZZA CHRISTOPHER SANDVOSS LAWRENCE WILKE<br />

AMEDÉE DIEUDONNE DIDIER NICOLAS E.H. ROTH JOSEPH HILL W.H. HAMMIG<br />

EDWARD DANIEL TETSUO MATSUDA PAOLO ANTONIO TESTORE GAETANO COLAS<br />

BRONEK CISON DANIEL HACHEZ ANDRANIK GAYBARYAN CHRISTIAN PEDERSEN<br />

STANLEY KIERNOZIAK GIOVANNI TONONI DAVID TECCHLER WILLIAM FORSTER<br />

GUNTER VON AUE DIDIER NICOLAS JOHANNES CUYPERS J.B. VUILLAUME SACQUIN<br />

robertson reCital Hall<br />

2014 Cello ColleCtion<br />

partial<br />

4 SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

www.RobertsonViolins.com<br />

Tel 800-284-6546 | 3201 Carlisle Blvd. NE | Albuquerque, NM USA 87110

Want more? The complete version of this duet is available by clicking here.<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

5

at<br />

ALISA WEILERSTEIN<br />

6 SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

I<br />

have been inspired for as long as I can remember to play music.<br />

I was the driving force behind my decision to play the cello as<br />

a child. My parents are chamber musicians and were constantly<br />

practicing and rehearsing with colleagues in the house (my father was<br />

the first violinist of the Cleveland Quartet for 20 years). The Cleveland<br />

quartet rehearsed in my home until I was 7 years old, and on top of<br />

that my parents were constantly taking me to concerts and allowing<br />

me to be around musicians. My mother tells me, when I was about<br />

2 years old, I would constantly listen to her practicing. At one point<br />

she was practicing the Beethoven 32 Variations, and I would become<br />

extremely unhappy if she spent less time than I wanted practicing<br />

that piece. I would throw tantrums because I wanted to listen to the<br />

incredible music. When I was three, it became clear that I had<br />

perfect pitch, and I would play games with my mother where she<br />

would play chords on the piano and I would try to name all the notes<br />

- it was very easy for me, a game I could always win. When I was four,<br />

I started to ask, and eventually demand, a cello and a cello teacher. Six<br />

months later I had my first cello, and I don’t remember questioning<br />

for a moment that this was what I would do with my life, I just loved<br />

it from the start.<br />

In the first months, I would do perhaps 30 minutes of formal practice<br />

a day, but once I was finished with my Suzuki pieces or simple music,<br />

I would take the cello into my bedroom and play around with it for<br />

hours. It was my dream at that time to play the Dvorak cello concerto,<br />

even though I could barely pronounce the word cello! I would try to<br />

teach myself how to do it, and I ended up with some funny physical<br />

habits that I took years to undo. It was the philosophy of my parents<br />

and my teacher that I should love the instrument first, and worry<br />

about the mechanics later.<br />

I developed my sense of musical imagery very early. It started for me<br />

when I was hearing music as images and characters. The way that my<br />

parents rehearsed, they were always discussing what characters or<br />

colors they were trying to communicate. I got right away that all the<br />

practice wasn’t just aimed at technical perfection. When I first started<br />

to play the cello, I was thinking about that already.<br />

My parents are chamber music players, and so the communication<br />

between players and the inspiration one receives from colleagues<br />

was something I really got from them. They have a huge amount<br />

of personality in their own playing, and I think I was naturally,<br />

subconsciously drawn to that. They encouraged all these things<br />

in me when I started playing.<br />

I remember once I had worked with a teacher for one lesson at around<br />

age 8. I played for my parents, and they told me to try and show me<br />

what I had learned from the teacher. I did, and I was very focused<br />

on the technical side of my playing, which I might not have been fully<br />

aware of at the time. I’ll never forget the horrified look on my parents’<br />

faces! My dad worked with me relentlessly until I got my natural<br />

impulse back. Of course, the mechanics of playing are extremely<br />

important, but only if they are married to the music. I’ll never forget<br />

the look they gave me when I played without the impulse.<br />

What is the Impulse?<br />

The impulse is your own natural, primal response to music. It’s how<br />

it affects you emotionally, and rhythmically. The impulse is movement,<br />

because the heart of music is rhythm. The response to rhythm is<br />

harmony, how something makes you feel on the most basic level.<br />

If you’re really in touch with your impulse, you already know how<br />

to phrase. Of course, that has to be refined with training, by listening<br />

and understanding.<br />

At the risk of repeating myself, it’s about really marrying technique<br />

and music on the deepest level, so you can still be in touch with your<br />

impulse even if you’re working through mechanics, even with physical<br />

problems. Ultimately the goal is to communicate something naturally<br />

without any hindrances. That’s what technique is for. I would never<br />

advocate going easy on technical training - I had an extremely rigorous<br />

technical training - but you must never lose sight of the fact that it’s in<br />

pursuit of a larger goal. I advocate practicing in a very mindful way,<br />

investing all elements of music making into every note that you play,<br />

even if it’s open strings or a vibrato exercise. That’s my philosophy.<br />

The aspect of teaching that I find most interesting is the task of finding<br />

out what will reach a person. This idea that you can’t separate technique<br />

and music at any time is central to me. Even when practicing<br />

scales, you have to think about the harmony, phrasing, quality of<br />

sound, different colors that you want to produce. For some people,<br />

these points are obvious, but for others this concept is being uttered<br />

for the first time. Even for the people who know this, it’s good to have<br />

that nagging reminder to always practice mindfully.<br />

It seems to be a universal concern that people don’t know what<br />

to do in the practice room. This invariably comes out while they’re<br />

performing, whether because they feel uncomfortable, or because<br />

certain concepts in their minds aren’t able to come out in their playing.<br />

It takes hard work for all of us to do this, and I find it very helpful<br />

for students to hear that this is a shared challenge for musicians, not<br />

an embarrassing or shameful personal shortcoming.<br />

In my own practice, the best example is found in slow practice with<br />

the metronome. Even when I’m trying to make sure the mechanics<br />

of a passage are back in place, I’m always thinking about the structure<br />

and phrasing - even if I’m focused on intonation. I’ll be looking for<br />

new colors, new things to learn or to say through the piece. It’s a very<br />

disciplined approach to practicing. Once you’re beyond the point of<br />

learning the notes and where everything goes, I think that practicing<br />

at 2/3rds tempo gives you the strength and reflexes to play the piece<br />

and allows you to keep a slightly relaxed yet focused mind.<br />

Starting young gave me some advantages learning my instrument. I<br />

don’t think anything was conscious when I was a young child wanting<br />

to learn the Dvorak concerto. It started as the ultimate goal! When I<br />

really started to learn it, I was about 12. Taking a focused approach<br />

to learning the music, I found that the better I got, the more I realized<br />

I didn’t know. When I first started to learn the Dvorak, I was surprised<br />

at how quickly some things came to me. I had waited my whole 12-<br />

year life to learn this piece that everyone had told me would be too<br />

difficult, and now I found that I could play most of the notes! Later,<br />

when I was performing it a lot, I began to appreciate the depth and<br />

layers to the piece. I caught some of those things early on, but my<br />

understanding of its structure and musical complexity continues<br />

to develop even now. Every performer should endeavor to remain<br />

a student, and to look for the lessons in everything he or she plays.<br />

If you are hoping to achieve real success in music, try to absorb as<br />

much as possible. I went to a lot of concerts, listened to a lot of recordings,<br />

and studied a lot of scores on the path to my career. The other<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

7

side, of course, is to have incredible drive and<br />

focus. I feel blessed that I have found motivation<br />

since I was a little kid - I don’t know why<br />

it has been that way, but it has.<br />

This life has tremendous benefits, but it can<br />

be very tiring and difficult, not to mention<br />

lonely at times. Returning from a hugely<br />

successful concert to an empty hotel room,<br />

with everyone you know asleep, and then<br />

three hours later having to fly to the next city<br />

- these are challenges that not everyone is cut<br />

out for, and it wouldn’t make all people happy.<br />

Luckily, this life makes me incredibly happy,<br />

but it’s vital that one should know all aspects<br />

of the performing lifestyle.<br />

It takes a tremendous amount of practice and<br />

focused hard work, and a great deal of curiosity<br />

to succeed at the highest level. You need to<br />

be able to read about the repertoire you study,<br />

and absorb a great deal of music. Since I don’t<br />

have the luxury of practicing six hours a day<br />

like I did as a student, I have to accomplish in<br />

two hours what I might have done with much<br />

more time before. I was forced to learn this<br />

mindful practice by the rigors of my schedule,<br />

so that I can perform at my top level on<br />

relatively little practicing.<br />

My practicing varies so much depending<br />

on the repertoire. I’m most often carrying<br />

three concerti and two recital programs on<br />

any given day. As I write this, I am currently<br />

playing one very demanding recital and three<br />

different concerti, as well as two chamber<br />

music projects. I have to prioritize, on a<br />

given day, which repertoire gets priority.<br />

From there, I look at what I already know<br />

well, and what is less familiar. Looking at<br />

programs ahead, I try to identify the music I<br />

feel is “uncomfortably fresh,” so I take out my<br />

scores and sort them. I start with 15 minutes<br />

of scales, played meditatively, to warm up. I<br />

then take 15 minutes to attack many of the<br />

most difficult spots, those places that still feel<br />

uncomfortable. Almost always, I do this at<br />

2/3rds of the tempo, practicing the difficult<br />

passages as if they were written to be played<br />

at the slower tempo - I have to execute all<br />

of the phrasing, colors, and shapes while<br />

maintaining a slower tempo. I will then hit<br />

the places in my concerti that need ironing<br />

out - of course, these vary from day to day<br />

and something may feel good one day and<br />

the day after become an issue. For virtuosic<br />

passages, I like working in rhythms, imposing<br />

a different rhythm on a passage to help me<br />

retain it more quickly. Sometimes this is<br />

effective, other times it isn’t! Of course, usually<br />

by this time in the practice session, I have to<br />

throw the cello back into my case and run off<br />

to a flight.<br />

I rarely record my practicing - I feel that<br />

doing so makes me more tense in practicing.<br />

The idea is that by not recording, you can be<br />

private enough to even get away from your<br />

own extremely critical ears. I know that my<br />

ear will be more critical than anyone else. It’s<br />

especially important after a demanding run<br />

of concerts that I have some time to quietly sit<br />

down with the instrument, not have anyone<br />

around me, and feel at liberty to experiment.<br />

There are exceptions to this in my own<br />

experience. I was recently learning the Eliott<br />

Carter Cello concerto, which is written in a<br />

very difficult language to familiarize oneself<br />

with. I was trying to really connect with it,<br />

and I recorded myself playing it several times.<br />

This was a very unusual approach for me -<br />

I found it to be very helpful, but it’s not<br />

something I would adopt as a norm.<br />

© Photo Jean-Baptiste Millot<br />

© Photo Uwe Arens<br />

Famous <strong>Cellist</strong>s<br />

Playing Pirastro Strings<br />

© Photo Aloisia Behrbohm<br />

© Photo Andreas Malkmus<br />

© Photo Christian Steiner<br />

Strings Handmade in Germany<br />

www.pirastro.com<br />

8 SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

© Photo Andreas Malkmus

The Well-Traveled Musician<br />

I think a big reason why I enjoy splitting my time evenly between<br />

the North America and Europe is that I get so many different<br />

perspectives and thoughts from both cultures. My own approach<br />

is really the result of osmosis, thanks to having had contact with<br />

so many unique musicians. Musicians are capable of learning so<br />

much from interaction with other great artists. This is one of the<br />

most important components of anyone’s musical education. I feel<br />

like I’m an eternal student, trying to take in as much as possible.<br />

One of the things I’ve always hated is labels. I’ve found that no musician<br />

falls into a particular category, and you can always find something else<br />

when you’re looking for it. One comment on my playing has always<br />

stood out and made me happy: “You don’t really have a school, I can’t<br />

tell where you’ve been trained.” Sounding like a mishmash of traditions<br />

to me is a comment on forming your individual voice. How do you go<br />

about forming this voice? Get your hands on everything - old recordings,<br />

new recordings, different nationalities, different artists! No matter<br />

where you come from, we do communicate in a universal language.<br />

It doesn’t matter what your background, it’s what you do with<br />

the information.<br />

I try to practice what I preach and listen to a great variety of recordings.<br />

I do go through periods where I don’t listen to a large quantity if I’m<br />

too busy, or if I’m developing a relationship with a new piece. Most<br />

of the time, though, I mix the old and the new because it’s important<br />

to reflect on the past and find new sources of inspiration. Like many<br />

professional players, I don’t have much time to attend concerts and<br />

find out what’s currently out there.<br />

These days I’m not listening to that many cellists. I’m listening to a lot<br />

of symphonic recordings, with both living and deceased conductors.<br />

I’ve always listened to a lot of Claudio Abbado recordings with the<br />

Berlin Philharmonic and Vienna, and his passing has been a reason<br />

to reflect on them again. I listen to a lot of Bernstein and Barenboim<br />

as well - these are minds that I respect so much. It’s always been<br />

fascinating to contemplate how you structure a Mahler symphony, or<br />

how you make sense of 9 Beethoven symphonies, or Wagner operas.<br />

I was scared by Wagner in my early twenties but now I’m absolutely<br />

entranced by it.<br />

When I’m listening to cellists, I listen to Casals and Jacqueline du Pre,<br />

Rostropovich, Piatigorsky, Yo-Yo Ma, and of course the cellists of my<br />

generation. It’s very interesting for me to hear different perspectives.<br />

I’ve always been in love with Casals’ recordings of the Bach suites.<br />

In terms of stylistic differences, they seem “outdated” in some ways,<br />

but I find them to be the most honest and intelligent recordings of<br />

the works. Jacqueline du Pre had such a short career, but she really<br />

recorded every concerto that was major at the time - every great<br />

Romantic concerto she performed is an excellent resource. Rostropovich<br />

takes me right back to when I was studying the Shostakovich concerti,<br />

Prokofiev Sinfonia Concertante, and Britten Cello Symphony. We<br />

almost owe him above anyone else for his recordings of the 20 th century<br />

cello repertoire. Beyond the classical world, I’m a big fan of Bjork, and<br />

I think the Beatles are geniuses. I listen to bossa nova, Venezuelan folk<br />

music, some Argentinian folk music, and Portuguese fado.<br />

The Future for <strong>Cellist</strong>s<br />

<strong>Cellist</strong>s today still don’t fully pursue their instruments as being as<br />

versatile as a violin. They’re not fully convinced that it is a true<br />

solo instrument. This is despite the fact that cellists agree that our<br />

instrument covers the range of the human voice and as such, it is a<br />

very relatable instrument. Honestly, I believe that it’s the chameleon<br />

of instruments, and it can really be anything we want it to be. Students<br />

especially need to embrace that fact and pursue it.<br />

One skill I would love to see my fellow musicians cultivate to a high<br />

degree is the performance mentality. I find a lot of performance<br />

anxiety in students today. I remember I was around 7, and I was<br />

preparing to do a small recital at the Cleveland Institute of Music.<br />

I was all dressed up and ready to go with my fractional sized cello.<br />

My mom looked at me and said “There’s no reason to be nervous<br />

because you’re very talented and you’re very prepared.” I think about<br />

that to this day, even though it’s so basic. We forget this in the throes<br />

of our doubts and the stress of trying to absorb everything we’re told.<br />

Knowing that, and really believing that to your core, for me was<br />

really powerful.<br />

Ultimately, any musician’s primary job is to communicate. We are so<br />

lucky to have this incredible language that touches everyone if we do it<br />

right. We can convey these ideas and emotions to touch everyone all at<br />

once, yet in an individual way. The Prokofiev Sinfonia Concertante is<br />

one of my favorite vehicles for this, because it’s a playground of voices<br />

and colors. Someone asked me once: Alisa, there are so many notes,<br />

and it’s so weird! The 2nd movement is twice as long as the others,<br />

and there are all these crazy characters. What do you imagine?<br />

To me, it’s like a big ballet - I think Romeo and Juliet is all over it.<br />

That piece in particular seems to me like a sequence of paintings, with<br />

colors and images that alternate being vivid, bucolic, wild. For me, as<br />

an artist to delve into that, it’s so much fun. I really enjoy performing<br />

it, and I hope that I can share that experience with audiences.<br />

A Note on My Gear<br />

I found something that really works in most halls - as a soloist you<br />

need to be able to project in 3,000 foot concert halls as well as recital<br />

halls. I use Jargar forte A and D strings - they are not a common string<br />

in the US - and I use Spirocore medium tension G and C strings. I<br />

have a 1790 William Forester cello and an Emile Ouchard bow. I have<br />

used the same cello since I was 16. I use Bernardel rosin, and I am<br />

a very heavy rosin user (ask anyone I know!). The only reason I use<br />

different rosins is when I forget mine, which happens much more<br />

often than I’d like to admit.<br />

For bow rehairs, I am very particular about the hair I get on my bow,<br />

when I have the luxury of choice. One of the strenuous aspects of this<br />

lifestyle is not always having control over who performs these services<br />

or where I can get them done. I’ve had jobs done is various cities when<br />

I just need it done, but if possible I like to go to Gregory Wylie in New<br />

York. I’ve also gone to Salchow, who has done a fantastic job. The<br />

single greatest rehair I’ve ever had done in my life was done in Vienna<br />

by Christina Eriks, and it actually lasted me more than a month, which<br />

is extraordinary for me!<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

9

SPOTLIGHT<br />

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CELLO SECTION<br />

When a great cello section plays in perfect ensemble together, there’s<br />

almost nothing in the world more exciting. Working with talented<br />

colleagues elevates your own playing, and it doesn’t get more talented<br />

than the men and women of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra cello<br />

section! With an impressive 11 musicians anchoring an already stellar<br />

orchestra, we want to recognize great musicianship and find out what<br />

makes this one of the best jobs in the country.<br />

In an orchestra as dynamic and precise as the Chicago Symphony,<br />

each section holds a key to creating the magic that audiences and<br />

record buyers count on from the group. Section member Brant Taylor<br />

has been playing with the orchestra for 16 years, and takes pride that<br />

the section is “widely regarded by our colleagues as one of the best<br />

sections in the orchestra. One of my section’s valuable contributions to<br />

the CSO is rhythmic stability.” Precision of rhythm is one of the most<br />

crucial elements in a successful ensemble, and in many ways this is the<br />

distinguishing point between a “good” interpretation and a “great” one.<br />

The CSO section is unquestionably armed with a great deal of experience.<br />

Veteran players bring wisdom and perspective from their time in<br />

the Grant Park, Milwaukee, Fort Worth, Florida, and Winnipeg Symphonies,<br />

to name a few. Brant Taylor describes his initial impression of<br />

playing with the Chicago Symphony: “I remember being swept up by<br />

the tremendous energy and sound of the CSO in concert, particularly<br />

in big works like Mahler symphonies and Strauss tone poems. Imagine<br />

a car that has an extra gear that other cars don’t have.” Small wonder<br />

that a 2008 Gramophone survey of the world’s greatest orchestras<br />

placed the CSO at #5, and first of all American orchestras.<br />

Many musicians share the credit for their recognition with a string<br />

of strong leaders in front of the orchestra from Pierre Boulez, Riccardo<br />

Muti, Daniel Barenboim, to Bernard Haitink. The orchestra<br />

has escaped the fate of some peer orchestras, not languishing during<br />

lengthy searches for music directors. These maestri are “musicians that<br />

value elegance and refinement,” says Taylor. This rare musicianship has<br />

allowed the CSO to sink its teeth in traditionally difficult repertoire<br />

for symphony orchestras, the more nimble and transparent works of<br />

composers like Mozart and Schubert. The orchestra also finds new<br />

inspiration by tackling less familiar works, bringing to life rare gems<br />

introduced by Muti thanks to his diverse tastes and experiences.<br />

in person to experience the true power of their performances. The<br />

unpredictability, the spontaneous moments driven by each person in<br />

the orchestra are rarely matched by any orchestra in the world. When<br />

contemplating the philosophy of the cello section, Taylor theorizes,<br />

“We play the way we play, and the combination of what we all have to<br />

offer as individuals makes a result greater than the sum of its parts.” ■<br />

SELECTED VIEWING:<br />

• Verdi Requiem, live in concert with Riccardo Muti<br />

This video has lots of great closeup shots of the action<br />

throughout the orchestra. Be sure to check out 58:45 - The<br />

opening of the Offertory is a great feature of this dynamic<br />

section in action.<br />

• Mahler Symphony No. 6, Bernard Haitink<br />

The orchestra performs at Royal Albert Hall with such an<br />

incredible range of colors and timbres and the legendary<br />

brass sound augmented by more horns than one can count.<br />

Great cello moments at 9:35, 21:25, and an incredibly<br />

menacing moment at 1:04:45. If you only have time for the<br />

highlights reel, don’t miss the hammer strike, start at 1:06:30<br />

for the buildup!<br />

CHICAGO PERFORMS. SO WILL YOU.<br />

Perhaps one of the most impressive elements of the cello section is the<br />

diversity of playing backgrounds represented by its members. Coming<br />

from all over the world, each player was selected to enhance the<br />

greater whole of the ensemble. Says Taylor, “I treat the section like a<br />

large chamber ensemble. I did not have to modify or compromise my<br />

artistic personality in any way to play in my section.” All great orchestras<br />

are at their core a collection of great artists, who make individual<br />

and group decisions spontaneously in concerts. No player reaches<br />

the level of the CSO without forming strong artistic opinions, and the<br />

sensitivity and adaptation that takes place, even in a single phrase,<br />

create unique results in every performance.<br />

This artistic melting pot is the essence of live music, and it is the<br />

reason an orchestra like the Chicago Symphony needs to be seen<br />

10 SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

Efe Baltacigil<br />

Inspiration, Execution, Education<br />

I’ve been thinking for weeks about what I would say about this.<br />

I think there are 2 ways to look at this. One would be the technical<br />

and objective way, and the other would be the reactive and inspired<br />

dimension, which is hard to explain.<br />

INSPIRATION<br />

Part of being a human being is having an individual voice and a desire<br />

to express yourself. We musicians are fortunate to have means beyond<br />

words to do this. It’s inevitable, once you start to play an instrument,<br />

that you should eventually want to say something with it. I think that<br />

string players in particular are lucky, because we have a great deal of<br />

flexibility and variety in our tone colors, our articulations, and the way<br />

we use time.<br />

I grew up in a very musical family, and was always drawn to music<br />

thanks to inspiration from them. My father is a bass player, and I<br />

grew up listening to him play the Bottesini Concerto and Grand Duo<br />

and other virtuosic repertoire. From the age of 3 or 4 on, my mother<br />

gave me a tiny handheld radio when I went to bed, and would put<br />

on Istanbul’s classical music station. These days, I am proud that my<br />

two younger brothers are also extremely accomplished musicians. My<br />

middle brother Fora has held double bass positions in the Minnesota<br />

Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the New York Philharmonic;<br />

my youngest brother Poyraz is studying at my alma mater, the Mimar<br />

Sinan University conservatory, and is doing some wonderful things<br />

on the cello and winning concerto competitions. What was really<br />

spectacular about Fora was his progress at a young age, studying with<br />

our father. I may be exaggerating, but it seemed like he had only been<br />

playing a few weeks before he started playing things I didn’t think were<br />

possible on a bass. It may have been a lucky break that my father took<br />

a trip to the US when I was a child and brought back an Edgar Meyer<br />

CD called Work in Progress from the airport. He played the CD for<br />

us, and for the first time we heard a bass playing Wieniawski’s violin<br />

music, and it was incredible! We listened to that CD day and night.<br />

Fora went on to study with Edgar at Curtis, as well as with Hal<br />

Robinson, and I’m sure that having this early childhood hero to<br />

aspire to allowed Fora to do some of the incredible things he’s done.<br />

I was very lucky to play beside Fora last year in front of the Berlin<br />

Philharmonic - we performed the Bottesini Grand Duo, and I played<br />

the violin part on cello, with Sir Simon Rattle conducting. This was<br />

an incredible honor for me, especially because we did it at the end of<br />

the orchestra’s European tour, in Istanbul and Izmir in front of 20,000<br />

people. It was really a dream come true for us, and sharing a stage with<br />

my younger brother was unbelievable. It can do a lot for your success<br />

to surround yourself with gifted musicians and keep exposing yourself<br />

to inspirational people.<br />

Two musicians alive today are particularly special to me. If you’re ever<br />

able to attend a rehearsal with either of them, you must take that opportunity,<br />

because the rehearsals are where the ideas and inspiration<br />

come alive. One is the fantastic conductor, Sir Simon Rattle. The way<br />

he rehearses is inspired - he’ll make you play a phrase, and you’ll<br />

realize that you’ve played it so much better than you’ve ever imagined.<br />

He can bring you to that 150% level you didn’t think you had. The<br />

other musician who does this extremely well is Yo-Yo Ma. Whether it’s<br />

chamber music or solo playing, he can look in your eyes and it brings<br />

you to this level of musicianship that includes you in his mastery.<br />

Ma also inspires this incredibly generous musical feeling. You end up<br />

playing on a level that you never could have imagined reaching. There<br />

is a talent to sharing your music making and understanding, and these<br />

two are perfect examples. They are both very self-sufficient people, and<br />

very happy with what they have achieved. They may have experienced<br />

struggles, but they are mostly struggles to achieve greater things<br />

musically and in life. I think that’s the key to being happy with what<br />

you are doing, to always be challenging yourself to do better at the<br />

things you love and care about. I think those are very important<br />

qualities to have to try and make better music.<br />

It’s truly difficult to say what it is Rattle and Ma are doing to be so<br />

inspirational. What’s very obvious is the love that they both have for<br />

every single note and the space between each note. You feel as though<br />

they’re focused on that in-between space, something you can’t quite<br />

perceive. It drives you to seek the immense beauty in each tiny<br />

increment of time. When you play with someone so committed,<br />

it’s hard not to give in to that passion and feel it yourself. You end<br />

up striving to do better yourself, and you end up doing it almost<br />

subconsciously, playing to the limits of your ability. They invite you<br />

to share in a common, powerful love for music making.<br />

It is true that some people from an early age find music comes easily,<br />

while others struggle and find it unnatural. Some people didn’t choose<br />

to begin learning music, they were forced to by parents or educators.<br />

It makes sense to me that not everyone feels phrases internally right<br />

away. Others desperately need music to express the things they have<br />

to say. It’s a wonderful outlet for emotions, and a very important part<br />

of many people’s lives. If you find yourself trying to teach somebody<br />

who doesn’t have that emotional connection, I think that helping them<br />

make one is more productive and important than any technique work.<br />

Looking forward to the rest of their lives, you will be helping them<br />

move many steps closer to fulfillment playing with other enthusiastic<br />

colleagues of any skill level. If you can help a person achieve that<br />

Yo-Yo Ma/Simon Rattle level of inspiration, you will have done an<br />

extraordinary thing!<br />

EXECUTION<br />

As a musician, you will collect knowledge from almost everyone you<br />

interact with. At one of my first cello lessons in Istanbul, my teacher<br />

Ihsan Kartal told me never to accent the end of a phrase.<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 11

ODE TO JOY<br />

Never hit the last D,<br />

always finish it humbly<br />

and respectfully.<br />

Some 27 years later, I still remember that<br />

moment, and he was so right! The only time<br />

I allow this to happen is when I’m told to do<br />

it by the composer. It’s very important that<br />

you have part of your mind on these tiny<br />

details. The little rules and bits of information<br />

accumulate over time, and hopefully combine<br />

with a good environment of friends and<br />

fellow musicians that you can use to stay<br />

connected to inspiration. The world we’re<br />

living in, with cell phones and computers,<br />

Facebook and other distractions, can get<br />

in the way of focusing on the purity of an<br />

individual phrase. In a way, music is a therapy<br />

to prevent yourself getting carried away by<br />

the world around you.<br />

While in high school in Istanbul I met a<br />

German cellist named Werner Thomas-<br />

Mifune for whom I played the Saint-Saens<br />

concerto. What was supposed to be a<br />

30 minute lesson ended up being almost<br />

2 hours long! He talked about the importance<br />

of the distances between the notes. He made<br />

distinctions between how you would play<br />

a half step versus a whole step. This lesson<br />

moved me so much that I couldn’t even fall<br />

asleep for about a week! That first phrase is<br />

a great example of how half steps and whole<br />

steps create this simple scale down that is<br />

filled with complex feeling and character. The<br />

minute you put this under a microscope and<br />

look at the notes you start to appreciate the<br />

differences between these intervals, you can<br />

begin to feel intimacy with the phrase.<br />

to singing, that ideal we’re always trying to<br />

emulate. The larger the interval, the more<br />

effort is required to sing it, and therefore<br />

the more attention and love we can put into<br />

playing it. It’s a crucial part of phrasing.<br />

If you truly understand the nuance that<br />

comes from these intervals, you can slow<br />

down your perception of the music and<br />

experience this wonderful close-up view.<br />

You start to appreciate what the composer<br />

had to say. You can’t live in this close-up<br />

world all the time, you have to go back to<br />

real time to get a larger picture, but it’s an<br />

essential part of learning and developing<br />

your musical vocabulary. There are tensions<br />

between notes, and if you can even halfway<br />

understand those distances, it will drastically<br />

affect your phrasing.<br />

Another of the incredibly powerful tools we<br />

have as musicians is the manipulation of time.<br />

Time, and the way you use it, expand or<br />

compress it, is essential to mastering classical<br />

music, especially when it’s very detailed and<br />

written out. However you control it and<br />

which sections you focus on create the style<br />

of music you are playing. Classical, Romantic,<br />

Modern, Baroque, all are affected by the way<br />

you take or give time. [Editor’s note: for a<br />

more detailed discussion of time, check out<br />

John Patitucci’s article Groove and Inspiration<br />

in <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Bassist.]<br />

My teacher at Curtis, Peter Wiley, really kept<br />

beyond execution, and that’s why it’s so<br />

important that you find inspiration<br />

in your life.<br />

Finally, I believe an invaluable tool for<br />

becoming a great musician is improvisation.<br />

It probably sounds scary if it’s unfamiliar,<br />

but ultimately, improvising and classical<br />

music are both just types of music. It doesn’t<br />

matter what genre you’re playing, in the end<br />

hopefully you’re trying to make music. It all<br />

comes down to the same core. If you can learn<br />

to do that, regardless of what your medium<br />

is (bow, pizzicato, cello, voice, whatever!),<br />

then you’re doing the best you can. As long<br />

as you can move the person that’s hearing<br />

you emotionally, then mission accomplished.<br />

The more easily and more readily you can get<br />

into that zone, the more successful you will<br />

become and the more success you can have.<br />

A WORD ABOUT SOUND<br />

AND EDUCATION<br />

One of my great advantages growing up was<br />

being around two phenomenal bass players,<br />

my father and brother. Why does it matter?<br />

I think it’s very important - the bass is by<br />

definition the foundation of music. It holds<br />

the whole harmony, and that is often a job we<br />

cellists have to perform as well. Even when<br />

you play the melody, if you’re not aware of<br />

where your feet are meant to be grounded,<br />

you will sound like you don’t know where<br />

you’re headed. I think<br />

it’s an essential part<br />

of musicianship, the<br />

sense of direction.<br />

It gives you a good<br />

compass when you are<br />

aware of the bass line.<br />

Consider why the line moves in the directions<br />

it moves, and why the color of one whole step<br />

is used instead of a half step. When you begin<br />

to contemplate why it was written a certain<br />

way, you start to care deeply about the music,<br />

become one with what the composer is trying<br />

to say. Whole steps and half steps are only a<br />

tiny part of the big picture of music - when<br />

you expand to look at other intervals, you<br />

can start to think about how the music relates<br />

Mi - Re - Do (whole steps) followed by a half step to Si and back to Do<br />

my focus on slowing the music down and<br />

finding the meaning. He really drilled me on<br />

left hand and right hand subtleties, like using<br />

a different quality of vibrato on each note,<br />

and playing different notes with different bow<br />

speeds to shape the phrase. There is a limitless<br />

potential on the cello for realizing phrases,<br />

and all the etudes and exercises in the world<br />

can’t come close to the complexity of playing<br />

one phrase of music with meaning. It goes<br />

I had a lot of wonderful<br />

teachers of harmony,<br />

theory, and counterpoint at Curtis. They<br />

all encouraged me to understand (or at least<br />

try to) what was going on harmonically in the<br />

music I was performing or hearing. A good<br />

entry point is Bach’s cello suites, because they<br />

are complex but still have only one or two<br />

lines going at once.<br />

I think it helps a great deal to be familiar<br />

12 SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

with the sound of the double bass, and its warm depth. It’s a quality<br />

of sound I look for in every new instrument I try, just as important<br />

as a singing A string. You want that fulfillment all around you when<br />

you play the low notes of a string quartet or solo line, or in the cello<br />

section. We spend a good amount of time in first position, and it’s<br />

vital to have a complete and well informed bass sound concept.<br />

BEING A COMPLETE MUSICIAN<br />

<strong>Cellist</strong>s have a unique set of roles to play in any genre. We can be the<br />

foundation of the music, then support the melody, then play melodies<br />

of our own, sometimes in a very short span of time. Not only that,<br />

but we sometimes move from string quartet to cello section<br />

to soloist in front of an orchestra almost as quickly.<br />

You have to be musically sensitive, because you won’t<br />

make any friends in your string quartet by playing like<br />

you’re performing the Dvorak Cello Concerto!<br />

You have to switch certain things, and be capable of<br />

taking a supporting role. In truth, you have to recognize<br />

that there are even moments in your concerto when<br />

your job is to accompany the violins or the flute with<br />

the melody. It all comes down to being familiar with the<br />

score in all settings. It’s a good thing to know what the<br />

second flute, for instance, is doing at all times. If you<br />

aren’t familiar with that, you lack the ability to know<br />

what the composer really meant for your own role.<br />

I spend time looking at free scores from IMSLP all the<br />

time. Recently, I was able to use the original manuscript<br />

in Beethoven’s hand for a recent performance of his 6 th<br />

Symphony. It’s all readable, although it takes a few pages<br />

to get used to the handwriting. You can see his thought<br />

process, mistakes, his scribblings! If you really want to<br />

do well, it’s a good idea to learn what’s going on. Week<br />

in and week out I study the scores of the repertoire<br />

to get a little bit closer to understanding. Having this<br />

knowledge of other instruments’ parts gives me wonderful<br />

guidance, it keeps me from being a fish out of water.<br />

A CHALLENGE<br />

I would like to encourage every musician out there to get a little<br />

more deeply in touch with his or her musicianship with this exercise.<br />

Imagine you are being asked by a radio station to program 45 minutes<br />

of your favorite classical music as a guest DJ. What would it be? What<br />

would it say about your tastes, your interest in different composers<br />

or ensembles? Once you are able to do this, try making a 45 minute<br />

definitive mix of your favorite music of any genre. I guarantee it’s<br />

challenging, because it was really quite hard for me to do it. I was<br />

asked by a Seattle radio station to do exactly this, and you can see my<br />

responses here. Listening is crucial, loving music even more so. Find<br />

what makes you inspired and capture that same feeling when you sit<br />

at the instrument. Anybody can make their musical ambitions reality,<br />

by working hard and keeping an open mind.<br />

SPRING 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 13