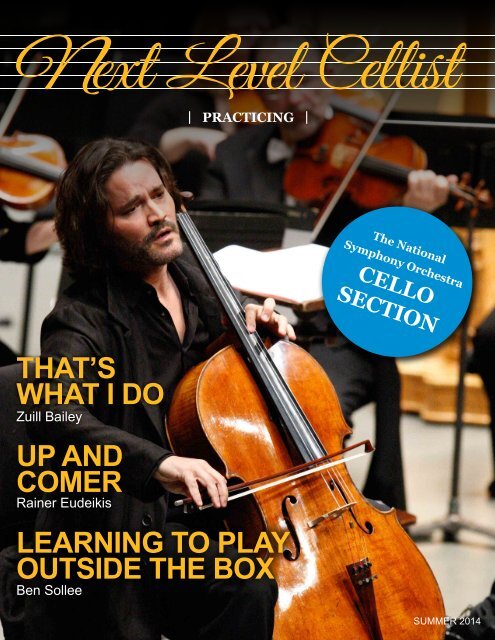

Next Level Cellist Practicing Issue

Articles by Zuill Bailey, Ben Sollee, Rainer Eudeikis, and the National Symphony cello section

Articles by Zuill Bailey, Ben Sollee, Rainer Eudeikis, and the National Symphony cello section

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

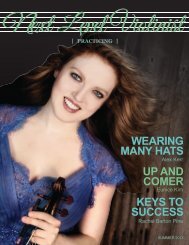

| practicing |<br />

The National<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

cello<br />

section<br />

That’s<br />

what I do<br />

Zuill Bailey<br />

Up and<br />

comer<br />

Rainer Eudeikis<br />

Learning to play<br />

outside the box<br />

Ben Sollee<br />

summer 2014

Contents<br />

Summer 2014<br />

Feature Story<br />

5 Up and Comer<br />

Rainer Eudeikis<br />

9 Spotlight:<br />

the national symphony orchestra<br />

cello section<br />

10 Learning to Play Outside the Box<br />

ben sollee<br />

13 That’s What I Do<br />

Zuill Bailey<br />

Contributors<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

PUBLISHER / FOUNDER<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

editor<br />

Edward Paulsen<br />

SALES<br />

Karen Han<br />

Layout designer<br />

2 NOV/DEC SUMMER 2013 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST CELLIST

Publisher’s Note<br />

It gives me so much joy to write to you from the digital pages of this second<br />

issue of <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Cellist</strong>. When selecting the contributors to this issue, I<br />

was seeking people who were masters of their instruments, and for practicing<br />

I wanted to find out what processes or discoveries led them to that mastery.<br />

As you will see, many of the answers turned out to stem from their teaching<br />

experience. I’ve met a musician or two who believes teaching is the “opposite”<br />

of practicing, but for many of us the art of instruction unlocks the secrets to<br />

those things that come naturally to us.<br />

I have always found myself drawn to the technique of identifying trouble spots in<br />

the repertoire I am working on, extracting the hardest moments and practicing<br />

them separately. What this takes for granted is that some of the music poses no<br />

problems and I simply play through it. Only when I am teaching the piece to another<br />

person might I have to analyze the passages that pose no obstacle to me, and at the<br />

end of the day, I am stronger and more capable for having broken those down too.<br />

In addition to the time you spend honing your skills in the practice room, find some<br />

time to help others in their journey. Sharing our knowledge with others makes us<br />

better players, better musicians, and better humans.<br />

The content of Zuill Bailey’s article is so deeply inspiring to me. Beyond the<br />

tremendous accomplishments he has made as a musician, he is a truly generous<br />

and compassionate man, and I think we should all aspire to the level of commitment<br />

he has made to serving communities outside the “classical music mainstream.”<br />

I found his discussion of technique development and the incredible standards of<br />

practice he maintains to be fascinating, and I hope you will too.<br />

Ben Sollee is such a unique artist, and I believe that he is on the forefront of a<br />

musical revolution that I am humbly proud to join in. Ben’s understanding of his<br />

craft, his thoughtful approach to teaching others to do what he does, and the path<br />

he has taken to his career are all great examples to live by, as well as an excellent<br />

resource. There’s no reason to get pigeon-holed into one category of musicians<br />

or another, and Ben’s broad set of influences show that nothing is irrelevant to<br />

the path towards success.<br />

I am so grateful to the National Symphony cello section for their input on our<br />

section spotlight. We should all be jealous of this group of players, almost all of<br />

whom spent a considerable portion of their careers working directly under Maestro<br />

Rostropovich. Orchestras have traditions and legacies, and you will read from a<br />

section with one of the most prestigious pedigrees in the business. Finally we are<br />

featuring Rainer Eudeikis in a new column for Up and Coming players. Rainer<br />

has had unbelievable success in the audition world, having just finished his career<br />

at the Curtis Institute of Music to head to Utah as the new Principal Cello of the<br />

Utah Symphony. His input is invaluable for anyone wishing to develop a career<br />

in orchestral cello playing.<br />

We are all part of a great musical family, and we can go our farthest by working<br />

together. I hope the practicing information you find here will serve to take you as<br />

far as your imagination can carry you, and well beyond. I’ll look forward to seeing<br />

you on the <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong>!<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Publisher <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

3

JOSEPH HILL RAYMOND J. MELANSON JOSEPH CHAROTTE-MILLOT ANNE COLE<br />

NICOLAS GILLES CARLO ANTONIO TESTORE ANTOINE CAUCHE DIDIER NICOLAS<br />

BOYD POULSEN PAUL HART JAMES B. MIN CARLO CARLETTI GIOVANNI TONONI<br />

GUY COLE RENATO SCROLLAVEZZA CHRISTOPHER SANDVOSS LAWRENCE WILKE<br />

AMEDÉE DIEUDONNE DIDIER NICOLAS E.H. ROTH JOSEPH HILL W.H. HAMMIG<br />

EDWARD DANIEL TETSUO MATSUDA PAOLO ANTONIO TESTORE GAETANO COLAS<br />

BRONEK CISON DANIEL HACHEZ ANDRANIK GAYBARYAN CHRISTIAN PEDERSEN<br />

STANLEY KIERNOZIAK GIOVANNI TONONI DAVID TECCHLER WILLIAM FORSTER<br />

GUNTER VON AUE DIDIER NICOLAS JOHANNES CUYPERS J.B. VUILLAUME SACQUIN<br />

robertson reCital Hall<br />

2014 Cello ColleCtion<br />

partial<br />

4 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

www.RobertsonViolins.com<br />

Tel 800-284-6546 | 3201 Carlisle Blvd. NE | Albuquerque, NM USA 87110

Up and Comer<br />

at<br />

Rainer<br />

Eudeikis<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

5

Origins<br />

I began my cello studies when I was six<br />

years old in the Dallas/Ft. Worth area. I<br />

studied with several different teachers over<br />

the first so many years, some from the Fort<br />

Worth Symphony. Just before high school I<br />

moved to Colorado, where I had some other<br />

teachers but eventually settled with Jurgen de<br />

Lemos, who was then Principal <strong>Cellist</strong> of the<br />

Colorado Symphony, and had previously been<br />

a member of the New York Philharmonic<br />

under Leonard Bernstein. It was around this<br />

time I started seriously buckling down and<br />

doing some work on orchestral excerpts.<br />

From there I went to the University of<br />

Michigan in Ann Arbor to study with<br />

Richard Aaron. I learned a great deal there,<br />

further organized my approach to cello playing<br />

and refined my practice techniques. Even<br />

today, much of the practicing I do is directly<br />

inspired by techniques I learned from him.<br />

After completing my undergraduate studies<br />

I moved to Indiana University to study with<br />

Eric Kim, who was Principal <strong>Cellist</strong> with<br />

the Cincinnati Symphony for 20 years. I had<br />

met Eric in Aspen when I spent a couple of<br />

summers there, and I knew he would be a<br />

great teacher for me. While studying at IU<br />

I developed further as a musician and it was<br />

under Eric Kim’s guidance that I really started<br />

to hone my approach to orchestral excerpts.<br />

I think my first audition was for a section<br />

position in the Detroit Symphony in early<br />

2012. I didn’t advance then, but I kept taking<br />

auditions over the next couple of years. I came<br />

to Curtis in Fall of 2013 to pursue an Artist<br />

Diploma (studying with Peter Wiley and<br />

Carter Brey), and won the first two auditions<br />

I took that year.<br />

How did you decide which<br />

auditions you were going to<br />

take? Were you going for a<br />

named chair, like principal<br />

or assistant principal, or were<br />

you just shooting for a job?<br />

Well initially I was just shooting for a job.<br />

Even before the audition in Detroit, I had<br />

applied for some other section auditions<br />

and was not invited. Interestingly, I wasn’t<br />

invited to a section audition held by the Utah<br />

Symphony a few years ago! As my preparation<br />

improved and I started to advance in auditions,<br />

I mainly focused on title chairs, with the<br />

exception of truly top-tier orchestras. Most<br />

of the musicians whom I’ve looked up to over<br />

my life have been principal players, and that’s<br />

what I wanted for myself.<br />

You mentioned a little bit about the prep<br />

work that you were doing for this audition.<br />

Could you elaborate? Did you change<br />

something when you started winning?<br />

I think Utah and Pittsburgh were my seventh and eighth auditions<br />

for professional orchestras. Every audition that I take requires me to<br />

revisit many of the same excerpts. Each time I have to work them back<br />

up from where I left off (or below that if it has been awhile since my<br />

last audition), but each time you work something up, it gets better,<br />

almost by default. Personally, my performance improved as I got used<br />

to the bizarre and stressful environment of the audition stage. You’re<br />

walking on this long carpet to mask any shoe noise (to prevent gender<br />

bias supposedly), there’s a giant screen in front of you, and you’re<br />

often playing sideways across the stage. The whole scenario can be<br />

disorienting and leave you feeling vulnerable. Over time, I’ve learned<br />

to transform that feeling of vulnerability into one of excitement to “get<br />

another shot.” It’s a skill that requires time and experience, for me anyway.<br />

I can think of some people who have won amazing jobs on their<br />

first audition, (and good for them!) but I certainly wasn’t one of them.<br />

Can you describe your warm up routine?<br />

I do between 30 minutes and an hour depending on how I’m feeling<br />

on a given day. I do scales, arpeggios in different inversions, sixths,<br />

thirds, octaves, and a variation on a Cossman exercise. I might throw<br />

in part of an etude if I feel like it. After I’ve gone through all of that,<br />

I spend time on a lyrical passage, whether it’s the Swan, a movement<br />

of Bach, or the cello solos from Brahms’ C Minor Piano Quartet or<br />

Piano Concerto No. 2. I’ll pick something like that and try to work on<br />

my tone and phrasing concepts. It’s nice to make a little music after<br />

spending an hour on pure mechanics.<br />

What’s your approach to nervousness?<br />

I used to be a shaker and a sweater, and it’s one of those things that<br />

just changed for me over time the more I performed or auditioned.<br />

When it comes to preparing for the moment of truth, I’m really into<br />

visualization. When I practice, I try to remind myself that nerves are<br />

something you really can’t fix until you’ve taken a few auditions.<br />

You try to remember what it was like, what it will be like when you’re<br />

onstage auditioning/performing again. It’s a pretty vivid experience<br />

and you learn, by doing it, how your body fights against you and how<br />

you can sabotage yourself mentally. I’ll play for my teachers and peers,<br />

and that’s helpful. Ultimately it comes down to taking as many auditions<br />

as you can, improving cellistically and mentally, and hoping you<br />

win as a result.<br />

Now that you’ve got a gig, what’s next?<br />

What are you practicing for, how often<br />

are you practicing now?<br />

I still have to be practicing quite a bit. I played my grad recital at<br />

Curtis a couple of weeks ago so I was preparing for that. I had a<br />

recording session recently. At this exact moment, I’m working on the<br />

cello part for Mahler Symphony no. 5 because I’m headed up to Utah<br />

next week to play with them. In the immediate future, mostly I’m just<br />

going to be trying to master all of the parts for the coming season with<br />

the Utah Symphony. I do play in as many side projects as I can, and<br />

I’m trying to line up some performances over the summer. Hopefully<br />

I can get some other projects going in Utah, but I’ll have to wait until<br />

I’m settled there to to get working on that.<br />

Do you have teaching aspirations? Are your<br />

side projects education based or are they more<br />

performance related?<br />

They are mostly performance related, but I do teach. I’ve taught a<br />

number of students, ranging in age from nine or ten years old to my<br />

only current student here in Philly who’s in his 60s. I do really enjoy<br />

teaching and I think having a handful of students while I pursue a<br />

performance career would be rewarding. I’ve done some things here<br />

at Curtis, like the All-City Orchestra’s Curtis residency. I’ve done a<br />

lot of teaching work in Colorado, too. My mom, in addition to being<br />

a professional clarinetist, is the Executive Director of the Colorado<br />

Youth Symphony so I’ve done a lot of chamber music coaching and<br />

teaching private students and working with youth orchestra cello<br />

6 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

sections and things like that. I’m looking forward to any teaching<br />

opportunities that may present themselves in Salt Lake City.<br />

Talk about some of the major moments<br />

you had developing as a cellist.<br />

There have been plenty of epiphanies along the way - it could be a<br />

small thing related to technique or performance mindset, but I wasn’t<br />

one of those kids who when I was very little just decided, I’m going to<br />

be a musician and that is all. My level of inspiration really hit a new<br />

high when I got to Indiana and was working with Eric Kim. I haven’t<br />

met many people who can give you goosebumps playing orchestral<br />

excerpts during your lesson. He’s definitely that guy, he’s the man!<br />

When I was with him I realized that I would like to model my own<br />

career after his. Honestly, that’s what helped me to choose Utah over<br />

the section position in Pittsburgh, because his only gigs were all<br />

principal jobs. He kind of climbed his way to the top, principal gig<br />

after principal gig. If I could do that too eventually, that would be great.<br />

Do you think that ultimately you’re going to<br />

use it as a platform to be a pedagogue?<br />

Someday sure, but not in the near future. Now and again you see the<br />

established principal cellist who decides to leave their position to<br />

teach, and I guess everybody needs a change at some point. You can<br />

only do something for so long and have it stay fresh. For me right now<br />

though it’s all fresh!<br />

What advice would you give to somebody who<br />

is on the path right now? What kept you going?<br />

If you do anything, record yourself. You can learn more in 30 minutes<br />

sitting in a practice room with a recording device than you might in<br />

3 hours without one. That has often been the case for me. Teachers<br />

and peers can of course offer valuable feedback, but you can get to the<br />

point where you teach yourself quite well. You just need to be able to<br />

hear yourself from a different perspective. I do that quite a lot, just<br />

put the phone on the stand. It doesn’t even have to be good quality!<br />

In fact, if you can make your phrasing and articulations super clear so<br />

that you can hear them on a crappy recording, then you know you are<br />

doing enough. As for what kept me driven through the process, it’s all<br />

a mix of disappointment and success, both make you want to go back<br />

at it. There’s that feeling when you’re sitting in the room and you know<br />

everybody who’s playing in your round and everyone’s sweating and<br />

biting their nails and fidgeting. Then the personnel manager comes<br />

out and says your name - that’s such a high, it can be a very powerful<br />

feeling! There aren’t many things like that, aside from actually winning<br />

the gig in the end. That’s even better. When luck isn’t on your side and<br />

you’re rejected, no one can turn that into a good feeling, especially for<br />

me. Later, though, you take that and you build on it and you do better<br />

the next time. I would add that I’ve seen plenty of rejection to get to<br />

this point in my life. Utah had this principal audition in April of 2013<br />

and I was in the semi finals for that. They took one guy to the finals<br />

and didn’t hire. I was disappointed, but I knew they were going to have<br />

© Photo Jean-Baptiste Millot<br />

© Photo Uwe Arens<br />

Famous <strong>Cellist</strong>s<br />

Playing Pirastro Strings<br />

© Photo Aloisia Behrbohm<br />

© Photo Andreas Malkmus<br />

© Photo Christian Steiner<br />

Strings Handmade in Germany<br />

www.pirastro.com<br />

© Photo Andreas Malkmus<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST<br />

7

the audition again. I thought that I had played pretty well, and was<br />

really excited to get another crack at it six months down the road.<br />

Do you have any excerpts or solos that you feel<br />

extremely comfortable with?<br />

If I had to pick a few, I’d say the theme and variations from Beethoven<br />

Symphony No. 5, the trio from Beethoven Symphony No. 8 and<br />

Smetana’s Bartered Bride Overture. Bartered Bride is my number one,<br />

I love seeing that on the list. There’s also the finale from Don Quixote,<br />

if it’s a principal audition. At the same time, if I see Prokofiev Symphony<br />

No. 5 or even La Mer, which is on every audition, I know I have to<br />

nail it but it doesn’t mean that it feels 100% comfortable at all times.<br />

Those are some that I may curse under my breath if I see that they’re<br />

on the round.<br />

Do you want to finish up with some general<br />

thoughts about the audition experience or what<br />

people need to get ahead?<br />

One thing that I have noticed at almost every audition I’ve taken is,<br />

if you’re in a warmup room and they’re not particularly well insulated<br />

for sound, you’re sure to hear what everyone else is practicing before<br />

they go in to play. One thing that I always hear without fail is someone<br />

blasting through Mendelssohn’s Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s<br />

Dream. It’s loud and really fast and it just sounds like they have no<br />

idea what’s going on in the piece. I always aim to play it slower. I’d<br />

rather come in slightly under tempo and be asked to play faster if they<br />

want it that way. Always aim to demonstrate your understanding and<br />

appreciation for the unique characters of the excerpts thatyou’re playing.<br />

You have to remember that the excerpts are not etudes, though<br />

they can feel like it. They’re all extracted from real music! I prefer the<br />

word “sample” to “excerpt.” It may be a trivial difference in vocabulary<br />

but I think they carry different connotations. One thing that Eric Kim<br />

told me that really stuck was that the way you feel inside when you’re<br />

playing will be reflected in your sound on the outside. It’s very hard<br />

to master your inner feelings, especially in a situation where you’re<br />

nervous and everything is on the line. If you can do that, though, even<br />

just a little bit, it really makes a huge difference and can put you ahead<br />

of the pack. ■<br />

8 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

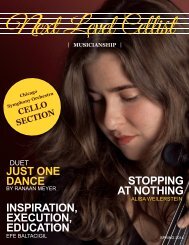

Spotlight<br />

the national Symphony Orchestra Cello Section<br />

The National Symphony Orchestra doesn’t make a big deal about this,<br />

but it was actually formed in 1930 by a cellist named Hans Kindler.<br />

The second music director, Howard Mitchell, was also a cellist. It is<br />

no wonder that the early influence of these leaders ultimately led to<br />

Mstislav Rostropovich, one of the most famous cellists ever to live,<br />

taking the reins from 1977 to 1994 and cementing the orchestra’s<br />

legacy as one of the finest ensembles in the country. Today, the<br />

10 members of the National Symphony cello section represent the<br />

perfect fusion of tradition and mastery, carrying forward the legacy of<br />

Rostropovich and representing the United States at the highest level.<br />

Several cellists in the National Symphony cello section were fortunate<br />

to work under Rostropovich during his 17 year tenure as music director,<br />

and reverentially recall the influence of his presence. Says Janet<br />

Frank, “He had an amazing sense for colors and he taught us to look<br />

for an appropriate sound in anything we play. His visual descriptions<br />

of what kind of sound he wanted were priceless.” Steven Honigsberg<br />

recalls, “He liked to tell us: his string sections must be like colors on<br />

a canvas. We must not always play with the same color or sound.” As<br />

a group so thoroughly attuned to color, one could expect conflicts of<br />

personality. On the contrary, says Frank, “Each of us contributes to<br />

both the section and the orchestra to the extent of our individual<br />

musical understanding. The merging of musical backgrounds gives<br />

our section the energy it demonstrates as a unit.” Principal David<br />

Hardy adds, “Many of us were hired by Rostropovich; so right off the<br />

bat we had access to what many people consider to be one the finest<br />

cellists of the last 50 years. Slava molded our sound production and it<br />

turned our section into a unified whole.”<br />

much about the greatness and depth of human emotion. I liken it<br />

to eating the finest caviar or drinking the finest wine.”<br />

The members of the National Symphony cello section bring an<br />

enormous body of experience to their performances, but they maintain<br />

a good deal of pragmatism in terms of the differences between<br />

great orchestras. Many believe, as Mark Evans does, that “orchestras<br />

a constantly evolving and changing.” Blatt elaborates, “their styles<br />

will change with new leadership. Some orchestras tour more or play<br />

different literature.” As principal David Hardy explains “Our section<br />

is very active musically outside the orchestra. Most of us are deeply<br />

involved in chamber music… we play solo recitals, concerti, and<br />

almost all of us teach. This activity keeps us musically fresh.”<br />

Pride in one’s work is also a common theme to these men and women.<br />

Loran Stephenson says that by remaining “collegial and flexible, we<br />

have a certain pride in the overall product.” Robert Blatt states, Since<br />

I joined the NSO in 1968, it has gone through a great many changes<br />

and tremendous growth. It has become a truly great orchestra and the<br />

cello section is one of the best anywhere.” Perhaps the most common<br />

sentiment in the cello section is summed up by Rachel Young - “I am<br />

a proud member of this section.” ■<br />

When asked about their favorite repertoire to play in the orchestra,<br />

most of the cello section mentioned Mahler. Given the orchestra’s<br />

love and understanding of color, Mahler represents the perfect fit.<br />

The section also gravitates towards those composers known for<br />

writing complex scores - Britten, Shostakovich, or Messiaen. That may<br />

be explained by Honigberg’s comment “Coasting is not appreciated<br />

by other members of your section.” Janet Frank agrees: “Each member<br />

does his best to do as well as he can to make a piece of music happen,<br />

to get the notes off the page. It is a matter of pride for the section not<br />

to have the conductor stop to rehearse us separately from the rest<br />

of the orchestra.” While many musicians struggle to find enjoyment<br />

in contemporary or challenging musical scores, perhaps these great<br />

musicians experience an elusive pleasure - performing with a stellar<br />

ensemble that does justice to even the most difficult scores.<br />

Winning an audition to join the National Symphony Orchestra is<br />

an enormous accomplishment, but getting the job is the first step to a<br />

successful career. After joining the orchestra, many of these extremely<br />

talented players found themselves adapting their playing to meet the<br />

demands and stylistic heritage of the section and the orchestra. Robert<br />

Blatt says that his playing has changed “gradually and often. Each new<br />

music director and section leader has different priorities and styles.”<br />

Mark Evans believes that “The key is to keep an open mind. Personal<br />

bowing style, fingering choices and even phrasing can be influenced<br />

to a great degree by colleagues.” These changes are a necessary<br />

by-product of working with talented musicians on both sides of the<br />

podium. Says Honigberg, “The orchestral canon has taught me so<br />

MORE than 170 artist-teachers and<br />

scholars comprise an outstanding<br />

faculty at a world-class conservatory<br />

with the academic resources of a<br />

major research university, all within<br />

one of the most beautiful university<br />

campus settings.<br />

STRING FACULTY<br />

Atar Arad, Viola<br />

Joshua Bell, Violin (adjunct)<br />

Sibbi Bernhardsson, Violin,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Bruce Bransby, Double Bass<br />

Emilio Colon, Violoncello<br />

Jorja Fleezanis, Violin,<br />

Orchestral Studies<br />

Mauricio Fuks, Violin<br />

The Pacifica Quartet performs<br />

as quartet-in-residence.<br />

Simin Ganatra, Violin,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Edward Gazouleas, Viola<br />

Grigory Kalinovsky, Violin<br />

Mark Kaplan, Violin<br />

Alexander Kerr, Violin<br />

Eric Kim, Violoncello<br />

Kevork Mardirossian, Violin<br />

Kurt Muroki, Double Bass<br />

Stanley Ritchie, Violin<br />

Masumi Per Rostad, Viola,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Peter Stumpf, Violoncello<br />

Joseph Swensen, Violin<br />

Brandon Vamos, Violoncello,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Stephen Wyrczynski, Viola (chair)<br />

Mimi Zweig, Violin and Viola<br />

music.indiana.edu<br />

2015 AUDITION DATES<br />

Jan. 16 & 17 | Feb. 6 & 7 | Mar. 6 & 7<br />

SUMMER 2014 APPLICATION NEXT LEVEL DEADLINE CELLIST Dec. 1, 20149

Learning to Play<br />

Outside the Box<br />

Ben Sollee

“Growing up in Kentucky, it was<br />

an interesting place both<br />

geographically and culturally”<br />

- there are a lot of people passing through, but not necessarily staying<br />

there. You grow used to extracting what you can from these experiences<br />

- Kentucky is known for distilling, after all! I picked up the cello in<br />

public schools, studying with a focus on classical music for the most<br />

part. I also had my social/family life, which was a very different scene.<br />

I would play fiddle tunes with my fiddler, and R&B music with my<br />

dad, or sing with my mother. For the longest time I lived those two<br />

lives on the cello. Once I started touring, I was experiencing different<br />

places, working with different musicians, and executing different<br />

things I needed to do. I found myself needing to be able to play a bit<br />

of everything. One of the best experiences for this was playing on<br />

the radio show “Woodsongs Old-Time Radio Hour.” On that show, I<br />

played in the house band with the host of the show, Michael Jonathan,<br />

and participated in over 200 broadcasts. We had artists come through<br />

from Time for Three, to Chris Thile, Bo Detta, Mike Seeger, and<br />

basically sit on the banks of the river, and play, and watch them come<br />

by, asking lots of questions. Having that resource for me was huge.<br />

I gained so many perspectives on the music industry. I learned that<br />

there’s no set book of rules or bill of rights for music, or for studying<br />

music. It’s about incorporating more and more into your playing,<br />

learning to comfortably speak in all different vernaculars. That’s really<br />

a big part of how I planted the seeds for where I’m going.<br />

Younger folks I’m meeting now might not have the same experience<br />

with a radio show, but they’re getting this knowledge from Youtube,<br />

where they’re looking at videos and being guided to new music and<br />

information. I think technology is playing a big role in the school<br />

for diversity right now. I think that’s the biggest thing I have found<br />

in reflecting on my college degree education. There was very little<br />

diversity from a study standpoint - it was more about specializing<br />

than diversifying. I was lucky to have the outside school of music to<br />

draw upon.<br />

My public school teachers were a husband and wife duo. Helen<br />

Kennison started me on cello, as one of 8 string players. We met in<br />

the utility closet of the gymnasium, and I was the only cellist. She<br />

really encouraged me to play where my passion led me. Her husband,<br />

Kevin Kennison, was a jazz arts teacher, and he ran the big band<br />

for the School of Performing Arts. He was very involved in making<br />

arrangements of popular songs for the orchestra. We played K.C. and<br />

Jojo’s “All My Life,” and R. Kelly’s “I Believe I Can Fly,” among others.<br />

He did a great job of arranging things and creating roles for people<br />

in the ensemble. He was one of the first guys who said “I can see you<br />

like to jam, so here’s the trombone part from jazz band. You can read<br />

those, so let’s get you playing with the band. We don’t really have cello<br />

parts for the jazz band, but that doesn’t mean you can’t play along.”<br />

Through them, I had some other school music experiences, playing<br />

in All-State Jazz Band. I snuck in on a blind audition as a bass player,<br />

even though I was playing the cello. I brought some heat down on the<br />

school for that, but it was a great experience for me.<br />

I had some wonderful private teachers early on as well. I studied with<br />

the cello professor at the University of Kentucky, Benjamin Karp, a<br />

wonderful player. He really struggled with how to incorporate my<br />

interests in other styles - he along with all my teachers could really<br />

only contextualize these interests with their classical studies. Teachers<br />

always liked the fact that I was experimenting but didn’t know how<br />

to unite it with their teaching. One person I worked with was a crazy<br />

guy named Michael Fitzpatrick. He was very open to things like jazz<br />

tonalities. He wasn’t a jazzer but he improvised. He was open to helping<br />

me sing along with the cello, improvise chords. I studied in college<br />

with my professor at Louisville named Paul York. He’s a pretty bangin’<br />

cellist, and I learned a lot from him. He put a lot of tools in my toolbag<br />

as a cellist. Even though he too had difficulty including my outside<br />

interests, he was the first guy to say, “Iisten, you have a responsibility<br />

because of your talent to learn. If you don’t like some of what I teach<br />

you, you can leave it on the table.” He gave me a vastly improved<br />

comfort in my bow arm. I think this has a lot to do with why I can<br />

go out and tour and tour and not sustain injuries.<br />

All the study and all the intense play result in a lot of physical<br />

problems for students of classical music. You see it a little in jazz,<br />

but you don’t see that in Indian music where people play for hours and<br />

hours a day. This culture of self-injury is really confined to classical<br />

music and particularly string players, so as an at risk person I’m<br />

grateful that Paul gave me the comfort I need in my bow arm.<br />

Right Arm Mechanics<br />

I take a very biometric approach to my right arm and sound production.<br />

It’s important to understand the muscle groups of the arm, shoulders,<br />

and back. <strong>Cellist</strong>s should always use the bigger muscle groups to do<br />

the work, and everything else (forearm, wrist finger movements)<br />

happen as a result of the big movements. To grow accustomed to these<br />

motions, spend a lot of time in the lower half of the bow, really moving<br />

from the shoulder blade and pulling the arm back so that those muscles<br />

are supporting the arm.<br />

From there, switch to letting your elbow open and then letting your<br />

wrist open. The bow is only one stick, but in your mind it can be divided<br />

into three parts - not by the length of the bow, but by the length of<br />

your arm.<br />

Some warmup exercises that encompass this include practicing with<br />

a drop of water going down your shoulder. The idea is that you want<br />

to use big muscles to put the weight into the bow, and just push that<br />

weight around. Make sure that a drop of water on your shoulder can<br />

roll all the way down your arm and onto the stick of the bow. I use that<br />

visualization when I’m warming up, if I’m experiencing a new type of<br />

pain, or especially if I’m teaching somebody this tool with the bow.<br />

People will struggle with getting the feeling of opening and closing,<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 11

and we’ll go to the water drop exercise and it’ll be resolved right away.<br />

I picked up a lot of techniques and practice styles from Eugene<br />

Friesen. He came from a classical background, but incorporates a lot<br />

of other styles in. He has a great book called “Improvisation for Classical<br />

Musicians.” What’s great about it is that he takes some very physical<br />

approaches and gives some great guidelines for getting around the<br />

instrument. He identifies the idea of playing in a zone as opposed<br />

to playing scales linearly - you play the notes from a scale that are<br />

available to you in a given position. It takes some of the mental stress<br />

away from “how do I get to that note to play it?” and puts some of the<br />

power in your fingers to lead the way. He also discusses using patterns,<br />

which is something I subscribe to a lot these days. It’s very important<br />

for teaching music.<br />

Singing while playing<br />

There is a lot of experimentation going on right now - people are<br />

deciding they want to try and play all sorts of music, even if they don’t<br />

know how to do it. I think there are some techniques from the guitar<br />

and piano world that are bleeding over. They’re mechanics that aren’t<br />

necessarily obvious next to the spectacle of someone singing and playing.<br />

There are two specific mechanics that can be set up to run themselves<br />

so the performer can focus on the performance: one is the idea<br />

of “strum bowing” which I picked up from Tracy Silverman. It’s a way<br />

of taking the acoustic guitar strumming pattern and applying it to the<br />

bow. These guitarists don’t think “down up up down down up down<br />

up” - they’re just moving their hand and adding accents! As string<br />

players, we’re taught to focus on our bowing all the time, which<br />

uses our brain power and pulls a lot of our attention. Getting<br />

rid of thinking of downs and ups and letting your body move<br />

in a mechanical way frees up mind power and helps you<br />

subdivide the rhythm. Your hand is always strumming.<br />

This is separate from the idea of chopping and scraping,<br />

which is getting to be a larger force in music making.<br />

The other thing is using chords on your instrument.<br />

Once you start thinking of the instrument laterally<br />

and not just linearly, you’re setting up these areas of<br />

comfort, where you can move one or two fingers and<br />

get significant changes in sound and color. You’re<br />

creating structure for your hand so you don’t have to<br />

think about where notes are. All these instruments<br />

people started singing on earlier were accessible<br />

because of frets, a basic map on the instrument.<br />

These instruments are easier to sing with because<br />

they take some of the focus and brain power off<br />

the musician who is accompanying him or<br />

herself.<br />

Getting<br />

students to strum comfortably, getting them to accent different<br />

patterns, then getting them to vocalise while they’re doing this is<br />

really key. It’s important not to try and add vocalization later. You can<br />

simply sing the accents you’re playing. This technique has been shown<br />

in workshops to get cellist singing and playing in under an hour.<br />

A lot of classical players, such as adults trying to play fiddle tunes, feel<br />

like they need to unlearn things. Personally, it’s difficult for me to say<br />

what’s best for this. I was never a classical player who transitioned. I<br />

was always going home after school and improvising, jamming with<br />

my parents or playing with bands. There was never a junction point for<br />

me. I don’t think there’s much to be unlearned. It’s a different culture<br />

- if anything you’re experiencing culture shock most of the time! For<br />

many classical players, strumming with the bow doesn’t even register.<br />

Many players already have all the skills to do this, they just have to<br />

learn something completely new to them. It’s like learning to eat spicy<br />

Indian food, or learning to cook a new cuisine. It’s different but all the<br />

techniques are there.<br />

I<br />

12 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

That’s<br />

What<br />

Do<br />

Zuill Bailey<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 13

Becoming a great musician begins at home. I grew up in a<br />

“perfect storm” environment. My parents were educators in<br />

the music world, and they did everything possible within that<br />

environment and behind the scenes to enrich my life. I grew up in the<br />

Washington DC area, and my early concept of the cello was sculpted<br />

by Mstislav Rostropovich, who was the music director of the National<br />

Symphony Orchestra from 1977 to 1994. The Suzuki method was<br />

a new phenomenon at the time as well, and that was where I began<br />

playing the cello at the age of 4. I was placed in a community where<br />

music and the arts weren’t taken for granted. Music was an outlet for<br />

creativity, a social meeting ground, and during my formative years I<br />

was absolutely immersed in it.<br />

The cello has been the key to opening doors to all the things that make<br />

me who I am. The cello is not the end-all but it has given me the opportunity<br />

to explore myself and the world. I do nothing for publicity,<br />

the things that I do are based on making a difference for others. It’s not<br />

about what I think people will believe in, or how I might draw attention<br />

to myself. I do things that are personally driven, because I feel like<br />

I’ve known who I am for a long time. To know who you are is to know<br />

what you want, and to believe in yourself. One needs to focus on that,<br />

and to share it with others to help them find themselves.<br />

As a cultural director, sculpting the path of a region, or as an Artistic<br />

Director, I want to give artists a platform to express themselves. I also<br />

try to create a platform that teaches them how to find themselves,<br />

based on my childhood - safe and supportive environments for young<br />

people. The greatest thing one can do is teach, because it teaches you<br />

how to keep exploring which works to improve oneself. The recording<br />

process to me is an education in and of itself. It’s a way to explore a<br />

particular project, but it’s also a document... a snapshot of your process.<br />

A recording is something that you share, where you invest your<br />

lifeblood, to preserve where you were at that time in your life.<br />

There was a pivotal moment when I was 12 that allowed me to become<br />

an active and communicative participant in life. At that time following<br />

my concerto debut, I vividly remember two things. I remember<br />

playing, which I did at the time mostly with my eyes shut. I remember<br />

opening my eyes and looking out into the concert hall. Everyone I<br />

could see had their eyes closed. As I reminisce, I remember thinking<br />

“Wow, music has helped them to escape.” My role in the hall at that<br />

moment, amongst the people on stage, was to give the audience a very<br />

special place outside of their lives. Backstage at the same concert, a<br />

man in a suit came up to me and gave me some advice. “If you can<br />

find something you love to do in this life, and you can live your life<br />

doing it, you’ll never work a day in your life.” This is a generic saying,<br />

but if you love what you do, it’s not work. I thought about it for about<br />

5 seconds, and I realized that music and communication was what<br />

I wanted to do with my life. From that point on, all I wanted to do<br />

was to figure out how to make that possible. Of course, that involves<br />

practicing huge amounts daily. I learned during that point in my life<br />

that it’s not “Practice makes perfect,” it’s “Practice makes permanent.”<br />

I realized after several years of repetition in practicing, that I had to be<br />

very careful because everything I practiced, if I practiced it wrong,<br />

was perfectly wrong.<br />

I have a very unusual feature about my body - my left hand is much<br />

larger than my right hand. In fact, my hand was even larger than my<br />

teacher’s hand. Every time he would give me a fingering or a bowing<br />

lesson, I would question it. This wasn’t because I was questioning him,<br />

but it didn’t feel right to my hand. He was taken aback by this, by the<br />

audacity of a then 15 year old student questioning his teacher. What<br />

he didn’t understand was that I wanted it to feel right and natural.<br />

He made a deal with me, that I could do any fingering that I wanted,<br />

unless I missed, and then I would have to use his teachings. From<br />

that day forward, I started formulating an understanding of the cello<br />

based on what I could learn from studying the piece from my unique<br />

perspective. Such a big part of this formula was also going to see the<br />

National Symphony every weekend, with incredible musicians like<br />

Yo-Yo Ma, Janos Starker, Rostropovich, Franz Helmerson, Gary<br />

Hoffman, Paul Tortelier - every week was someone else at that level.<br />

I didn’t just watch, I was absorbing during those formative years. I<br />

came up with a different approach to the cello - it wasn’t just a melding<br />

of historical styles, it was also trying to understand why we do the<br />

things we do. I didn’t want to be part of the grapevine effect because it<br />

didn’t work for me. When I started recording, I started getting many<br />

more questions about how I did what I did. <strong>Cellist</strong>s are very community<br />

driven, and they do share. This is why we have cello festivals,<br />

publications - this is why a lot of cellists throughout history have been<br />

community organizers (ie. David Finckel, Ralph Kirshbaum). Ludwig<br />

Masters, a publisher under the umbrella of Kalmus, asked me if I<br />

would publish editions to document the approach that fits me, in the<br />

hopes of benefitting future cellists. I have six editions out now, and<br />

I am slowly but surely working through the cello repertoire. That’s a<br />

legacy thing, so people will understand not just sonically what I was<br />

linked to in my life, but physically what I was doing as a cellist.<br />

I was only in Suzuki for about four years. What I remember distinctly<br />

was the physicality and how the teachers emphasized the use of the<br />

ears. I remember being so specific about how to hold the instrument<br />

and the bow. I remember holding everything in my hands and arms in<br />

a certain way, and then trying to copy the sound I was hearing to make<br />

a nice sound on my own. I learned to use my ears to get to that goal.<br />

I remember trying to vibrate, and wanting it so badly that I would<br />

literally shake my cello! I was always trying to make a nice beautiful<br />

vibrato, but nobody was teaching that, they were basically teaching<br />

the structure of the instrument only. After 4 years, my parents (being<br />

musicians themselves) really wanted me to read music.<br />

Following Suzuki, I started studying with a cellist from the National<br />

Symphony who began putting me through the structure of etudes -<br />

Schroder, Popper, Piotti, Sevcik, concerti and of course Bach. This<br />

helped me see what all these tools were being sharpened for - Suzuki is<br />

a great way to teach children. In my opinion, this is the way children<br />

learn how to speak. It’s mimicking and the teacher’s job is to ensure<br />

that there is enunciation. Repetition helps to refine the execution, and<br />

just as a child watches an adult repeat a word to clarify, Suzuki teaches<br />

you to refine your playing by hearing a phrase or a measure multiple<br />

times. I was lucky to have been in an area with really wonderful teachers<br />

who put a sound in my ear. We would begin repertoire while doing<br />

etudes, but when a problem occured in a piece technically, my teacher<br />

would go back into the etude books and find the specific etude to<br />

remedy the problem. I was studying all the music and technical works<br />

at the same time. During my study of the Saint Saens concerto, I was<br />

given a Popper etude that I worked on for a while until I could see how<br />

applying a certain technique made a musical effect possible in the concerto.<br />

My teacher studied with Orlando Cole, a master teacher at Curtis.<br />

Cole had his own process which was passed along to me through<br />

my teacher. I was fortunate at age 18 to study with Cole myself, and<br />

it was interesting to see how the original source of this information<br />

14 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

differed and resembled my experience.<br />

I began to awaken as a cellist in my early<br />

teens. I started to recognize what I was<br />

playing. I began making these Olympian tests<br />

for myself. If you looked at my book, my goal<br />

was to pass off an etude each week. That was<br />

where the idea of “practice makes permanent”<br />

really came into play. I had to learn all these<br />

techniques which were all new to me. It’s kind<br />

of like riding a bike. When you’re attempting<br />

to learn a skill, it’s very foreign until it works,<br />

and then it’s familiar from that day forward.<br />

That was a funny time in my life - learning<br />

spiccato, double stops, marcato, detache,<br />

and all the other terms and their execution.<br />

Popper was huge for me, but it was not the<br />

end-all...music was the end-all. During my<br />

high school years, I didn’t perform all the<br />

etudes using that method, because my teacher<br />

felt some were redundant, and we were<br />

pulling them out as needed to address other<br />

concerns.<br />

One thing that became an issue was that I<br />

had to find a way to make my left hand<br />

more efficient. For a long time, my fingers<br />

seemed to each have a different driver. I<br />

would put one down and the others would<br />

release and go all over the place. I also dealt<br />

with collapsed knuckles. I justified this<br />

because Rostropovich had collapsed joints<br />

when he played. Someone told me that when I<br />

played like Rostropovich, no one was going to<br />

mention it! It was very hard to keep my hand<br />

unified. The person who probably has the<br />

most gorgeous left hand around is Lynn Harrell.<br />

It’s magic watching his left hand work.<br />

Watch for the efficiency - every action is both<br />

a reaction and a preparation. When I saw him<br />

play in the mid-80s, it was a revolution. When<br />

I heard his playing, that was the kind of playing<br />

I heard in my head. It was vocal playing,<br />

not cello playing. The connection between the<br />

notes that I always wished to hear was like the<br />

singing I did around the house. I had never<br />

heard someone so beautifully sing on the cello<br />

before I heard Lynn Harrell play. I’m very on<br />

top of all my students that I come in contact<br />

with, “be very aware of your left hand!”<br />

When I first moved to El Paso I played golf. I<br />

was ok, but not great. I would practice these<br />

strokes before I would take the swing. I was<br />

playing with an older gentleman one day, and<br />

he would just walk up and hit it - BAM! And<br />

I’d go up and try 4 test swings and then hit it.<br />

I asked him why he didn’t test, and he told me<br />

that he only had enough energy for one round<br />

of golf that day. Since I was hitting four or five<br />

times per shot, I was playing 4 or 5 times the<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 15

ounds he was. I thought this was something<br />

I could try to apply to the cello, and try to<br />

find a way to play with the least impact on my<br />

body, with maximum efficiency. This is one<br />

of the main ways to eliminate fatigue. This is<br />

how I choose fingerings. My goal is that you<br />

won’t hear the technique. Our job as musicians<br />

is to put in all this hard work behind the<br />

scenes to remove the sounds of “technique”<br />

in the music. I don’t want to hear great cello<br />

playing, I want to hear great music.<br />

As I progressed through my<br />

life from recordings as a teen<br />

to now, I don’t hear my cello<br />

playing as much as I hear the<br />

music. I don’t want to hear a<br />

fingering - if I hear how I’m<br />

doing something it’s a problem.<br />

The other aspect that was a<br />

problem for me was that I<br />

was a very strong, energetic<br />

young man, and I put that into<br />

my playing. When I was 18, a<br />

teacher told me that my career<br />

was going to be officially over<br />

by my late 20s. He told me to<br />

refine my playing, and let my<br />

body play for me. This concept<br />

of “pulling” sound rather than<br />

“pushing” sound, this vocabulary<br />

helped me understand<br />

that I was working way too<br />

hard. If you let the music come<br />

out and don’t force it, it’s freer<br />

and more beautiful. At 18, I<br />

began working at using the big<br />

muscle groups. I experimented<br />

with posture, endpin lengths,<br />

use of the Stahlhammer (bent)<br />

endpin, chairs, etc. just to<br />

make sure I was not headed<br />

for injury. I needed to give the<br />

amount of energy necessary<br />

for a passage and no more.<br />

During that time period, the<br />

mannerisms and affectations in<br />

my playing disappeared. Before that I jumped<br />

around and moved - the more I showed, the<br />

more I felt. I wanted to hear it in my sound<br />

instead. That led me to contemplate what kind<br />

of sound I wanted. Do you want a sound that<br />

is overly expressive? Do you want refinement?<br />

What does refinement mean? Who in the past<br />

has represented this ideal to you?<br />

The moment you start to realize that, you<br />

gravitate towards those musicians from the<br />

past. You develop a sense of self and what you<br />

want. A perfect example of a beautiful posture<br />

and a natural approach to the instrument is<br />

Leonard Rose. He massages the sound out<br />

with each hand, everything is flexible. When<br />

he pulls a down bow, his hand sinks into the<br />

bow. The stick moves into the first knuckle<br />

and the palm comes down, pulling down. On<br />

the upbow, the hand lifts like a paintbrush.<br />

The endpin for Leonard Rose and Lynn<br />

Harrell is exemplified by the ability to stand<br />

up at any moment. This was present in Janos<br />

Starker’s pedagogy and he always enforced it.<br />

Bach for Cello<br />

Six Suites<br />

for Violoncello Solo<br />

BWV 1007-1012<br />

The most popular edition<br />

of the Cello Suites with fingering<br />

and bowing by A. Wenzinger<br />

BA 320<br />

Scholarly critical performing<br />

edition consisting of 7 volumes<br />

(music volume, text booklet,<br />

facsimiles of the 5 sources)<br />

Urtext · BA 5216<br />

„It is a very innovative publication,<br />

setting a new standard for performance<br />

studies for the next century.“<br />

(Bach Bibliography)<br />

Bärenreiter<br />

www.baerenreiter.com<br />

Concerto<br />

in A minor<br />

However you sit playing the cello, you need to<br />

be able to stand up at any given moment. You<br />

can’t contort yourself and still pull the maximum<br />

beauty of sound. I found that position<br />

in my early 20s. Before that, I was all over the<br />

map - endpin at 4 feet long, or 4 inches long...<br />

all different ways. Now when I hear someone<br />

play, based on their sound production, I can<br />

probably tell you how they are sitting - this<br />

is based on tension in the sound, release in<br />

sound, and also how the left hand is working.<br />

If the left hand is tight, it’s because the body<br />

is tight too. If your right hand is clawing the<br />

for Violoncello, Strings<br />

and Basso continuo<br />

after BWV 593<br />

BA 5136<br />

Arranged by Joachim F. W. Schneider<br />

Piano reduction · BA 5136-90<br />

Johann Sebastian Bach’s famous concerto<br />

for organ BWV 593 is an arrangement<br />

of Antonio Vivaldi’s concerto op. 3 no. 8<br />

from L’Estro Armonico for two solo violins,<br />

strings and basso continuo.<br />

Our new edition, in turn, is an arrangement<br />

of this organ concerto and has been<br />

scored for violoncello solo, strings and<br />

basso continuo. It was commissioned<br />

for Sol Gabetta.<br />

Idiomatic arrangement for cello<br />

Welcome addition<br />

to the cello concerto repertoire<br />

bow, your left hand will be tight. If one hand<br />

is relaxed the other will be as well.<br />

My warmup routine (and this is at 41 years<br />

old) is all about sound. You have to have a<br />

gorgeous warm sound as a cellist - if you don’t<br />

have that, what do you have?! I tune, and<br />

while I’m tuning I’m starting to release and<br />

think about my bow. I slowly start to put<br />

my fingers down on the strings, and gradually<br />

introduce vibrato. This is partially to warm<br />

my fingers up and partially to open my ears.<br />

I start working on pitch<br />

bending to start opening my<br />

NEW<br />

ears further, and shift to hear<br />

the things between the notes.<br />

I slide around slowly here and<br />

there, maneuvering my way<br />

up the fingerboard into thumb<br />

position and start working on<br />

opening my hand up to feel<br />

comfortable in higher ranges.<br />

Mostly, I’m trying to play<br />

beautiful notes. I’m also playing<br />

on all different sides of my<br />

fingers. When you looked at<br />

Rostropovich’s callouses, there<br />

was a line from the bottom of<br />

his fingers all the way to the top.<br />

It wasn’t just at the end of the<br />

fingers that he played. He used<br />

every single part of the whole<br />

last half inch of his finger to<br />

produce the sounds he wanted<br />

to produce. I employ some<br />

spiccatos and bow exercises.<br />

These were more important to<br />

me when I was younger and<br />

trying to sharpen these tools.<br />

That’s not my first priority at<br />

this point. I do scales when<br />

I’m warming up. The scale is<br />

the perfect way to work on<br />

your playing. You’re working<br />

on intonation, vibrato, sound<br />

production, shifting, moving<br />

around the instrument, trying<br />

to make the strings even. All music really<br />

comes down to is broken down scales. I’ll play<br />

scales in whatever keys the pieces I’m playing<br />

contain in 3 or 4 octaves, very slowly. I’m very<br />

aware of my left hand’s efficiency. I’m not a<br />

big believer in extensions, because I believe<br />

that they are variable. It comes down to theory<br />

vs. practice. When I’m on stage, depending<br />

on lots of things, the most important thing is<br />

that my hand is relaxed. It’s vital that what I’ve<br />

practiced is the same whether it’s cold in the<br />

room, hot, humid, dry, whatever the situation.<br />

I’ve found in my experience that extensions<br />

16 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST

vary. When I’m practicing my scales, I typically open it by tilting my<br />

hand back slightly. It’s the equivalent of playing in thumb position and<br />

vibrating on the D or A strings, and then bringing that hand straight<br />

back into first position or second position with your thumb still up,<br />

and then positioning the thumb back behind the neck. Your hand<br />

remains flexible in the knuckles and all the other joints, rather than<br />

squaring it off. Those reaches stop being extensions, which pertain to<br />

a square hand. When I put down my second finger a half step higher<br />

than normal, my hand is already in motion to curl back into a comfortable<br />

ball. My hand is never fully open for more than a millisecond<br />

this way. So many times when you’re playing in first position, your<br />

hand is squared off with the fingers perpendicular to the strings, you<br />

will encounter issues as you shift up the neck. If you practice in the<br />

low positions with your fingers angled back as they would be in thumb<br />

position (as exemplified by Feuermann), you’ll have freedom in your<br />

hand. I ask students to vibrate and move their arms around (without<br />

collapsing the finger) and it helps them to add flexibility even at the<br />

knuckle. I prefer students to work on this every day.<br />

For posture, I like to stand behind students and lay a hand on their<br />

shoulders to reduce tension there. When they are vibrating, I’ll touch<br />

their elbow to drop that and it increases the beauty of that motion and<br />

makes it more expansive.<br />

In my teens, I spent about 25-30 minutes a day just experimenting<br />

on the instrument. I was exploring how I could push the limits on the<br />

cello - sonically and technically. I just wanted to see based on recordings<br />

that I listened to, if I could find a way to emulate the sound on<br />

my own cello. My teacher at the time gave me the freedom to try and<br />

do these things however possible. I try to pass this on to my students,<br />

telling them if I don’t notice what they’re doing, then do it. Everyone’s<br />

vibrato and sound are different. I just don’t want to see a problem that’s<br />

going to be a bigger problem later.I used to record myself practicing<br />

to help understand more about my playing. These days, because I play<br />

under pressure so often, and because I have done a great number of<br />

recordings in my career, I now know what it sounds like externally<br />

based on what I’m doing on the cello. That’s a practiced place that<br />

I wasn’t in 5 or 6 years ago. I was going back and forth, playing and<br />

listening all the time. Technologically speaking, things have changed<br />

so much recently. Now, I’ll put my iPad on the stand and film myself<br />

playing so I can decide whether the vibrato is too wide or the shift<br />

is too much, or if it looks like I’m not playing comfortably. I find in<br />

cello playing if it looks awkward, it will sound awkward. If something<br />

sounds off in a recording, I can guarantee I will see some contortion in<br />

the cellist’s playing. The body, as it gets older, will shut down because it<br />

can’t sustain that kind of physicality.<br />

I think practicing in front of a mirror is a really good idea because it<br />

gets you out of your own playing. I also prefer players who don’t stare<br />

down at their instruments while playing, because looking straight<br />

ahead frees up the body and allows your ears to capture some of the<br />

ambient quality of the sound. Instead of crouching in, you want to<br />

project the sound out. If your chest is open (only possible with your<br />

head up), then you can play open and your sound can ring out. I<br />

always ask the student after they play what they thought, how they felt,<br />

what can they do better. Usually in group settings, we go around and<br />

ask what the other students have observed, and this is very beneficial<br />

for discovering ways to improve. Any time I show students a video of<br />

their playing, they fix posture issues immediately. They don’t know<br />

that they’re doing these things most of the time. That’s the role a<br />

mirror can play when you’re by yourself.<br />

I have a studio at the University of Texas El Paso, and I typically give<br />

masterclasses on every trip I make for performing. I recorded the Bach<br />

Cello Suites six years ago, and I spent a lot of time trying to figure<br />

out how to do that. You don’t want to just throw it together. I bought<br />

every edition I could possibly find, and most of those were out of<br />

print. I ended up with about 50 editions. They were all over the map<br />

with technical and musical decisions. In Bach there are no musical<br />

directions! I created an interpretation, and then I let go of the editions<br />

for about 2 years. I became very accustomed to playing all 6 suites in<br />

one sitting. I started performing these in preparation for recording,<br />

and after that it became an event to celebrate the CD, which continued<br />

to be a part of my life. As I played all the Bach, students would<br />

come backstage afterwards and ask how I had done this or that. They<br />

would reference the recording, they would even give me their music<br />

so I could write in the fingering or bowing, and they would write me<br />

to let me know that it had worked. It helped me to realize that what<br />

I was doing was effective, and I realized that these solutions weren’t<br />

available in other editions. I went back to the sources I used, and I<br />

found that most of my decisions were my own, not documented in the<br />

other music. Around that time, Kalmus approached me about making<br />

some editions, which is quite rare these days. There are no cellists of<br />

note for the past 25 years that have made editions - we keep spinning<br />

the ones from the 50’s, or we occasionally see a new scholarly edition<br />

from Baerenreiter or elsewhere. These are often not performance<br />

based editions. It took me 2.5 years to document the Cello Suites.<br />

Pablo Casals refused to write down his fingerings and bowings for<br />

Bach because they changed, and I agree with him. The way I justified it<br />

was to include in the editions how I played the Bach in the recordings.<br />

When people buy the recording, they will have a way to follow along<br />

and see what I was doing in that specific instance. It may not be what I<br />

do now, but it’s what I was doing on the recording. Everywhere I went,<br />

people bought the recording and the score. Kalmus asked me to record<br />

and document the other pieces that I play often. This has included the<br />

Dvorak, Saint Saens, Elgar, Rococo Variations, Schelomo. I’m working<br />

my way through the basic core repertoire, and I have enlisted the assistance<br />

of Tim Janoff of the Internet Cello Society to write an introduction<br />

at the beginning of each edition to let cellists know of the history<br />

of these pieces. They should know why these pieces are important in<br />

history, how they were created and for whom they were created.<br />

Growing up, there weren’t any editions that included that information.<br />

I tried to make these editions very helpful, and making it clear that<br />

these are performance editions of how I present the works in concert.<br />

Kalmus has the original plates, and I asked them to have the original<br />

cello part printed into the piano part, so that when someone buys<br />

these editions they can have the piano part as their scholarly reference<br />

to see what the composer wrote, and contrast that with the performance<br />

edition which is designed to work when playing in front of<br />

2000 people.<br />

A conversation I have with students is that being open to a life in<br />

music and having a career with the cello is not simply playing the<br />

Dvorak concerto or playing the Bach Cello suites in recital. Being a<br />

cellist involves doing it all. I didn’t know this growing up. I aspired<br />

to be what I thought I saw great cellists doing. A life in music is so<br />

multi-faceted and it can be so fulfilling if you make it so. We of course<br />

want to be better musicians, but what is it for? Yes, we want to play<br />

well, and of course it’s for us, but we have a responsibility to educate<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST 17

and stimulate the audiences to be our audiences.<br />

I had a student recently say that he was graduating, and he told me he wanted to do what I do. I asked him what he thought I did. His answer<br />

was “Play concerts.” I was shocked! The concerts are one sliver of what a person can do. If it were all based on concerts alone, it would be very<br />

limited. On every trip I take, I get off the plane, and the first thing I ask is “How can I help?” I perform in prisons, libraries, nursing homes,<br />

anywhere that will have me. I have played in a neonatal ICU for the mothers and the young babies, using the power of music to soothe and heal.<br />

I give classes at the local universities for the cellists there. I perform free concerts for Rotary Clubs and other service organizations. This is all in<br />

addition to playing the Elgar concerto, for instance with a Symphony Orchestra. During the five days I am in a particular city, I can play a piece<br />

twice on paper, but then again about 17 times around that. I even do “Show and Tell” projects at area elementary schools so the kids can learn<br />

about the basic fundamentals of the cello. Many students feel like they simply cannot run at this pace, but this is the reality of what I do.<br />

What drives me is seeing how music changes people. That’s why I get on a plane every day, and wake up in a different place every day, to see that<br />

one moment where people can escape through the power of music.<br />

Music<br />

DEPARTMENT of<br />

The String Area and The UTEP Symphony Orchestra<br />

congratulate<br />

Mr. Zuill Bailey<br />

for his many significant<br />

achievements and for his<br />

consummate service to UTEP and our musical<br />

community.<br />

Stephanie Meyers, String Area Coordinator<br />

Violin, Viola<br />

Stephen Nordstrom<br />

Violin, Viola<br />

Zuill Bailey<br />

Cello<br />

Erik Unsworth<br />

String Bass<br />

Lowell E. Graham<br />

Director of Orchestral Activities<br />

18 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL CELLIST