VERSANT

A travel magazine design project by Hannah Mintek with photography by Corinne Thrash

A travel magazine design project

by Hannah Mintek with photography by Corinne Thrash

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

February 2017<br />

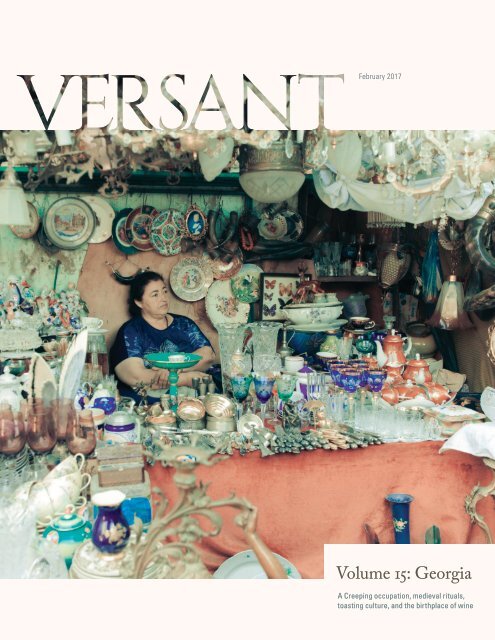

Volume 15: Georgia<br />

A Creeping occupation, medieval rituals,<br />

toasting culture, and the birthplace of wine

Contributors<br />

Front cover photo<br />

A local merchant at the Dry Bridge open<br />

air antique market. See page 68 for the<br />

Last Look from around Tbilisi’s old town.<br />

Back cover photo<br />

Sunset in the Caucasian Mountains,<br />

upper Svaneti. See page 38 for our main<br />

feature: Medieval Mountain Hideaway.<br />

versant<br />

EDITOR IN CHIEF Sarah Ramsson<br />

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Tara Harris<br />

SENIOR EDITOR Laura Linderman<br />

MANAGING EDITOR Jamie Weed<br />

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sandy Smiertka<br />

ART DIRECTOR Hannah Mintek<br />

PHOTO DIRECTOR Corinne Thrash<br />

Corinne Thrash<br />

Artist, commercial photographer,<br />

and videographer<br />

based in Seattle, Corinne<br />

Thrash specializes in travel<br />

and marine photography. This<br />

month for Versant, Thrash<br />

has gone above and beyond<br />

in exploring the terrain of<br />

the Caucasus and the lives of<br />

Georgians. Spending nearly<br />

three weeks tirelessly shooting<br />

everything from the caves of<br />

Orthodox Christian monks to<br />

the incredible wine history of<br />

Georgia, her work executes an<br />

incredible range of diversity.<br />

Be sure to explore her main<br />

photo essay, Youth of Tbilisi,<br />

page 61, capturing a modernizing<br />

era of young adults; an<br />

intimate chance to reflect on<br />

the changing tides in Georgia’s<br />

development. Discover<br />

more of Thrash’s work:<br />

corinnethrash.com<br />

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS<br />

Annetta Black<br />

Haley Sweetland Edwards<br />

Jonathan Hirshon<br />

Brook Larmer<br />

Stosh Mintek<br />

Simon Ostrovsky<br />

Paul Salopek<br />

Corinne Thrash<br />

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS<br />

Hannah Mintek<br />

Corinne Thrash<br />

DESIGN DIRECTOR Hannah Mintek<br />

INK, 68 JAY ST., STE. 315,<br />

SEATTLE, WA 98103<br />

TEL: +1 206 802 8495<br />

FAX: +1 206 555 1882<br />

EDITORIAL@<strong>VERSANT</strong>.COM<br />

<strong>VERSANT</strong>.COM<br />

WEBMASTER Kylie Della<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

MANAGING DIRECTOR<br />

Ambar de Kok Mercado<br />

U.S. GROUP PUBLISHING DIRECTOR<br />

Jenn Woodham<br />

INTERNATIONAL ADVERT DIRECTOR<br />

Ana Raab<br />

VP STRATEGY AND BUSINESS<br />

Dave Lohman<br />

COMMERCIAL DIRECTOR<br />

Sam To<br />

VP, SPECIAL PROJECTS<br />

Liz Ungar<br />

DIRECTOR, SPECIAL PROJECTS<br />

Jane Courage<br />

STRATEGIC ACCOUNTS DIRECTOR<br />

Carole Mouawad<br />

U.S. TERRITORY MANAGER<br />

Houssam Nassif<br />

PRODUCTION MANAGER<br />

Casey Milone<br />

PRODUCTION CONTROLLER<br />

Faye Ziegeweid<br />

Haley Edwards<br />

A correspondent at TIME,<br />

Edwards previously was an editor<br />

at the Washington Monthly<br />

where she wrote about policy<br />

and regulation. As a freelance<br />

reporter Edwards has covered<br />

stories around the Middle<br />

East and the Caucasus. Her<br />

installment of Getting Your<br />

Bearings this month comes<br />

from her personal experience<br />

of having lived and traveled<br />

throughout Georgia for<br />

two years. She has a passion<br />

for baby goats, world travel,<br />

and Georgian cheese bread.<br />

Paul Salopek<br />

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist<br />

and National Geographic<br />

Fellow Paul Salopek is<br />

retracing on foot our ancestors’<br />

migration out of Africa<br />

and across the globe. His<br />

21,000-mile odyssey began in<br />

Ethiopia and will end seven<br />

years later at the tip of South<br />

America. Now three years<br />

into his sojourn Salopek has<br />

passed through the cradle of<br />

culture in the Caucasus. His<br />

article Ghost of the Vine will<br />

leave you wanting to toast to<br />

peace and your ancestors.<br />

Simon Ostrovsky<br />

Soviet-born American<br />

documentary filmmaker<br />

and journalist best known<br />

for his coverage of the 2014<br />

crisis in Ukraine for VICE<br />

News and Selfie Soldiers, a<br />

2015 documentary. Ostrovsky<br />

won an Emmy Award in 2013<br />

for his work with VICE.<br />

In this issue, Ostrovsky’s<br />

article “The Russians are<br />

Coming: Georgia’s Creeping<br />

Occupation” explores Russia’s<br />

need for control in the<br />

Caucasus and its strain along<br />

separatist borders of Georgia.<br />

Versant is produced monthly by INK. All material is<br />

strictly copyrighted and all rights are reserved. No<br />

part of this publication may be reproduced in whole<br />

or part without the prior written permission of the<br />

copyright holder. This is a graphic design project of<br />

Hannah Mintek and is not a publication in circulation.<br />

No money was exchanged for this magazine.<br />

Contact: hannahmintek@gmail.com<br />

2 • versant

06 Getting Your Bearings<br />

08 Talk the Talk<br />

09 Experience: Vardzia<br />

14 Tradition: The Georgian Supra<br />

22 Politics: Russia is Coming<br />

30 Culture: Ghost of the Vine<br />

38 History: Medieval Mountain Hideaway<br />

56 Make: Salt of the Earth<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

58 From the Road: Jack and Bebu<br />

61 Perspective: Youth of Tbilisi<br />

68 Last Look

gamarjobaT<br />

Gamarjobat and Welcome!<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

As we seek to discover meaning and universal truths throughout our<br />

travels we may wonder if some places will touch our hearts more greatly<br />

than others. Georgia did that for me. In all of my journeys I have never<br />

been met with such depth of culture, passion, love, and intensity for<br />

life than in my time here.<br />

To say that Georgia is like no other country perhaps is to sound ignorant,<br />

but what you are likely to experience here is truly like no other.<br />

From its green valleys spread with vineyards to its ancient cathedrals<br />

and watchtowers perched on fantastic mountain overlooks, Georgia<br />

(Saqartvelo) is one of the most beautiful countries on earth and a marvelous<br />

canvas for walkers, horse riders, cyclists, skiers, rafters and<br />

travelers of every kind. Equally special are its proud, high-spirited, cultured<br />

people: Georgia claims to be the birthplace of wine, where guests<br />

are considered blessings, and hospitality is the very essence of life.<br />

A deeply complicated history has given Georgia a fascinating backdrop<br />

of architecture and arts, from cave cities to the history of silk<br />

road trading to the inimitable canvases of Pirosmani. Tbilisi, the<br />

capital, is still redolent of an age-old Eurasian crossroads. But this is<br />

also a country moving forward in the 21st century, with spectacular<br />

contemporary buildings, an impressive road renewal project<br />

under way, and ever-improving facilities for the visitors who<br />

are a growing part of its future.<br />

We welcome you to discover the incredible mark<br />

that Georgia could leave on your heart<br />

and memory.<br />

— Hannah Mintek

Getting Your Bearings<br />

GEORGIA: Getting Your Bearings<br />

The Basics<br />

Gotta Have Faith<br />

The Lay of the Land<br />

Georgia is a strip of land in the Caucasus<br />

region of Eurasia, just south of Russia between<br />

the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, north of<br />

Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. It’s a little<br />

bigger than West Virginia and home to about<br />

4.6 million people.<br />

The Georgian Orthodox Church, which has<br />

its own patriarch, Ilia Meore, was the national<br />

religion for more than 1,500 years prior to the<br />

Communist era, when it was all but eliminated.<br />

But since the fall of the Soviet Union, the<br />

church has enjoyed a huge resurgence. Today,<br />

84 percent of the population is Orthodox.<br />

Georgia is hemmed in by mountains: the<br />

Greater Caucasus to the north, the Lesser<br />

Caucasus to the south, and the Likhi Range<br />

right down the middle. These mountain ranges<br />

make Georgia a patchwork of different climates.<br />

Western Georgia is mostly subtropical,<br />

covered in lush, green rainforests. On average,<br />

it rains there twice as much as it does<br />

in Seattle. But Eastern Georgia is drier, like<br />

California’s Central Valley.<br />

6 • versant

By Haley Sweetland Edwards<br />

White People<br />

Not the Peach State<br />

Gift of Gab<br />

The term “Caucasian” can be traced back to a<br />

19th-century German anthropologist named<br />

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Upon visiting<br />

Georgia, Blumenbach claimed to have discovered<br />

the origins of mankind. He labeled<br />

the race of white men “Caucasian,” after the<br />

nearby Caucasian Mountain range. Nowadays,<br />

Georgians have embraced the idea that they<br />

lent their genes to the whole of Europe. A<br />

popular tourism slogan around Georgia claims,<br />

“Europe started here.”<br />

Georgia the country is often confused with<br />

Georgia the US state, although the names<br />

are completely unrelated. The US state got<br />

its name from King George II, while the<br />

country’s name is derived from the Persian<br />

word Gurjistan, meaning “the land of the<br />

foreigners.” The people of Georgia are barely<br />

aware of the confusion, though; they call their<br />

country Sakartvelo.<br />

Most Georgians speak Georgian, or one of the<br />

three languages closely related to it — Svan,<br />

Megrelian, or Laz. All four belong to a family<br />

of “linguistic isolates,” meaning they have<br />

virtually no relationship to any other language.<br />

Georgian is also one of the oldest living languages<br />

in the world.<br />

versant.com • 7

Language<br />

Talk the Talk: Georgian Language<br />

Georgian (Kartuli) is the official language<br />

of Georgia and the country’s most widely<br />

spoken language, used on street signs and in<br />

all aspects of everyday life. There are about<br />

4.1 million people who speak Georgian on a<br />

daily basis: approximately 3.9 million living<br />

in Georgia and the rest living abroad, notably<br />

in Russia. Georgian (Kartuli) is related<br />

to three other languages, all spoken within<br />

Georgia and Northeastern Turkey: Megreli,<br />

Svan, and Laz. There are 15 common dialects<br />

of Georgian reaching as far as Turkey,<br />

Azerbaijan, Armenia and Iran.<br />

Important notes:<br />

There are no capital letters in Georgian.<br />

It is phonetically regular.<br />

It is an unstressed language — each syllable<br />

receives equal weight.<br />

Georgian distinguishes between aspirated<br />

and non-aspirated (ejective) consonants for<br />

t, p, k, ch, and ts.<br />

Diphthongs do not exist in Georgian.<br />

Alphabet: Georgian uses one of the world’s<br />

12 unique alphabets, Mkhedruli — “that of<br />

the warrior.”<br />

ა a<br />

ბ b<br />

გ g<br />

დ d<br />

ე e<br />

ვ v<br />

ზ z<br />

თ t<br />

ი i<br />

კ k’<br />

ლ l<br />

მ m<br />

ნ n<br />

ო o<br />

პ p’<br />

ჟ zj<br />

რ r<br />

ს s<br />

ტ t’<br />

უ u<br />

ფ p<br />

ქ k<br />

ღ gh<br />

ყ q’<br />

შ sh<br />

ჩ ch<br />

ც ts<br />

ძ dz<br />

წ ts’<br />

ჭ ch’<br />

ხ kh<br />

ჯ j<br />

ჰ h<br />

1 ერთი ehr-tee<br />

2 ორი oh-ree<br />

3 სამი sah-mee<br />

4 ოთხი oht-khee<br />

5 ხუთი khoo-tee<br />

6 ექვსი ehk-vsee<br />

7 შვიდი shvee-dee<br />

8 რვა rvah<br />

9 ცხრა tskhrah<br />

10 ათი ah-tee<br />

Yes (formal) დიახ dee-akh<br />

Ok კარგი k’ahr-gee<br />

No არა ah-rah<br />

Maybe ალბათ ahl-baht<br />

Where? სად? sahd?<br />

Hello გამარჯობა gah-mahr-joh-bah<br />

How are you? როგორა ხართ? roh-goh-rah khahrt?<br />

Fine, thank you. კარგად, გმადლობთ. k’ahr-gahd, gmahd-lohbt.<br />

Nice to meet you. სასიამოვნოა. sah-see-ah-mohv-noh-ah.<br />

Please თუ შეიძლება too sheh-eedz-leh-bah<br />

Thank you. გმადლობთ. gmahd-lohbt.<br />

Excuse me. უკაცრავად. oo-k’ahts-rah-vahd.<br />

I’m sorry. ბოდიში. boh-dee-shee<br />

Goodbye. ნახვამდის. nakh-vahm-dees.<br />

Help! დამეხმარეთ! dah-meh-khmah-reht!<br />

Good morning. დილა მშვიდობისა. dee-lah mshvee-doh-bee-sah.<br />

Good night. ღამე მშვიდობისა. ghah-meh mshvee-doh-bee-sah.<br />

Now ახლა ahkh-lah<br />

Later მერე meh-reh<br />

I don’t understand. ვერ გავიგე. vehr gah-vee-geh.<br />

Where is the toilet? სად არის ტუალეტი? sahd ah-rees t’oo-ah-leh-t’ee?<br />

I want… მე მინდა… meh meen-dah…<br />

What is your name? რა გქვიათ? rah gkvee-aht?<br />

My name is… მე მქვია… meh mkvee-ah…<br />

Do you speak English? ინგლისური იცით? eeng-lee-soo-ree ee-tseet?<br />

How much/many…? რამდენი…? rahm-deh-nee…?<br />

Stop to let me off. გამიჩერეთ. gah-mee-cheh-reht.<br />

It is delicious. გემრიელია. gehm-ree-eh-lee-ah.<br />

I don’t want anymore. მეთი არ მინდა. meti ar meen-dah.<br />

Cheers. გაუმარჯოს. gau-mar-jos.<br />

Here’s to you. გაგიმარჯოს. ga-gi-mar-jos.<br />

wine ღვინო ghvee-no<br />

water წყალი ts’q’ah-lee<br />

8 • versant

visit<br />

vardzia<br />

by Annetta Black<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash

Experience<br />

In desperate circumstances people are often driven to perform feats<br />

of mythical proportions. In the late 1100s the medieval kingdom of<br />

Georgia was resisting the onslaught of the Mongol hordes, the most<br />

devastating force Europe had ever seen. Queen Tamar ordered the<br />

construction of this underground sanctuary in 1185, and the digging<br />

began, carving into the side of the Erusheli mountain, located in the<br />

south of the country near the town of Aspindza.<br />

When completed this underground fortress extended 13 levels and<br />

contained 6000 apartments, a throne room and a large church with an<br />

external bell tower. It is assumed that the only access to this stronghold<br />

was via a hidden tunnel whose entrance was near the banks of<br />

the Mtkvari river. The outside slope of the mountain was covered with<br />

fertile terraces, suitable for cultivation, for which an intricate system of<br />

irrigation was designed. With such defenses, natural and man made,<br />

the place must have been all but impregnable to human forces. Alas,<br />

the glorious days of Vardzia didn’t last for very long. Though safe from<br />

the Mongols, mother nature was a different story altogether. In 1283,<br />

only a century after its construction, a devastating earthquake literally<br />

ripped the place apart. The quake shattered the mountain slope<br />

and destroyed more than two-thirds of the city, exposing the hidden<br />

innards of the remainder.<br />

However despite this, a monastery community persisted until 1551<br />

when it was raided and destroyed by Persian Sash Tahmasp.<br />

Since the end of Soviet rule Vardzia has again become a working<br />

monastery, with some caves inhabited by monks (and cordoned off<br />

to protect their privacy). About three hundred apartments and halls<br />

remain visitable and in some tunnels the old irrigation pipes still bring<br />

drinkable water.<br />

10 • versant

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

versant.com • 11

THE GEORGIAN<br />

SUPRA<br />

Learning the delicate art of eating and toasting<br />

by Jonathan Hirshon<br />

In the deeply traditional culture of Georgia, a Supra (Georgian: სუფრა) is an age-old Georgian<br />

feast and an important part of Georgian social culture. Georgian wine flows freely and several to<br />

several dozens of courses of food come out throughout the night, often followed by dancing and<br />

signing. A supra can commonly go until 2 or 3 in the morning. Broadly, it is a traditionalized feast<br />

ideally characterized by an extremely abundant display of traditional foodstuffs.<br />

The supra is also an occasion for ritualized imbibing. Drinking wine or liquor at a supra is<br />

accompanied by ceremonial toasts, which are directed by the toastmaster, who combines the<br />

consumption of alcohol with specialized, emotional and articulate spoken word. Knowing the<br />

history and etiquette of a supra will ensure survival of the fittest when visiting Georgia.<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash

“A successful tamada must possess great rhetorical<br />

skill and be able to consume a large amount of<br />

alcohol without showing signs of drunkenness.”

A tamada giving the opening toast at a supra.<br />

Dishes begin to stack as guests arrive.<br />

Every supra follows the same set of rules,<br />

but the level of formality depends on<br />

the occasion. Supras can be held almost<br />

anywhere, including restaurants, gardens,<br />

schools, graveyards and, perhaps<br />

most commonly, at homes. Most often,<br />

guests sit at a table, which is covered<br />

with small plates of food that continue<br />

to be brought out and refreshed<br />

throughout the course of the supra.<br />

There are two types of supra: a festive<br />

supra (ლხინის სუფრა), called a keipi,<br />

and a sombre supra (ჭირის სუფრა),<br />

called a kelekhi, that is always held after<br />

burials.<br />

In Georgian, “supra” means “tablecloth”.<br />

It’s likely related to the Arabic<br />

sofra (ةرفس) and Turkish sofra, which<br />

are both words for traditional eating<br />

surfaces. Large public meals are never<br />

held in Georgia without a supra; when there are no tables, the supra<br />

is laid on the ground, typically seen during excursions to churches.<br />

At a supra, toasting is a high art and Georgians have elevated it<br />

to a degree not seen many other places in the world. What follows<br />

is how that toasting process, contest and history are all showcased<br />

during a supra.<br />

Regardless of size and type, a supra is always led by a tamada, or<br />

toastmaster, who introduces each toast during the feast. The tamada<br />

is elected by the banqueting guests or chosen by the host. A successful<br />

tamada must possess great rhetorical skill and be able to consume<br />

a large amount of alcohol without showing signs of drunkenness.<br />

During the meal, the tamada will propose a toast, and then speak<br />

at some length about the topic. The guests raise their glasses, but do<br />

not drink. After the tamada has spoken, the toast continues, usually<br />

in a counter-clockwise direction (to the right).<br />

The next guest who wishes to speak raises their glass, holds forth,<br />

and then drains their glass. If a guest does not wish to speak, they may<br />

drink from their glass after some words that particularly resonate for<br />

him or her. Eating is entirely appropriate during toasts, but talking is<br />

frowned upon. Once everyone who wishes to speak on the theme has<br />

done so, the tamada proposes a new toast, and the cycle begins again.<br />

While some of the more important toasts require drinking your<br />

glass to the bottom as a sign of respect (bolomde in Georgian), the traditions<br />

of the Georgian table space the drinking out over the course<br />

of the meal.<br />

Here are the rules. You cannot drink until the tamada (toastmaster)<br />

has made his toast and drinks. Only then, and usually in order<br />

around the table, can other revelers repeat the toast and drink. Never<br />

propose a different toast unless you are<br />

given permission: that is an offense to<br />

the tamada.<br />

If the toast is made to you as a visitor,<br />

to America or England, to the President<br />

or the Queen, or in any way bears<br />

directly upon your presence, you must<br />

wait to drink until everyone else has<br />

gone before you. Your toast in response<br />

should be one of thanks.<br />

Occasionally you will hear the<br />

tamada say “Alaverdi” to someone. This<br />

means that one guest has been chosen to<br />

elaborate the tamada’s toast. All other<br />

present their drink to this same theme.<br />

Georgians take traditional toasting<br />

very seriously. There is a structure and<br />

balance to a Georgian toast.<br />

Toasts are made with either wine<br />

(usually) or brandy (occasionally, either<br />

local or imported), and nothing else — toasting with beer can be considered<br />

an insult, though the patriarch recently deemed it to be ok.<br />

If you are being toasted, you are supposed to wait until the tamada<br />

has finished, then stand up and thank the toaster. Then, you should<br />

wait until everyone else is done before drinking your wine in one go. If<br />

the tamada says Alaverdi to you, you should elaborate on his toast. If a<br />

large ram or goat’s horn (called the khantsi) is brought out during the<br />

meal and filled with wine, then an honored guest — perhaps you — is<br />

supposed to drink it to the bottom.<br />

If someone else is being toasted, the easiest advice is to wait until<br />

everyone else is drinking to drink your wine. Other than that, it’s<br />

good advice to be quiet while the tamada is talking, and remember<br />

the various other rules of etiquette in Georgia, some of which are not<br />

putting feet on the furniture and not chewing gum in public.<br />

The proper response to Georgian toasts is “gaumarzos”, meaning<br />

literally ‘to your victory’; pragmatically it is equivalent to ‘cheers.’<br />

Immediately after the toast, people clink glasses with the tamada.<br />

Normally, when a foreigner is present, the tamada starts with a toast<br />

to long-lasting friendship with him or her.<br />

Traditions and national values are frequently mentioned. Every foreigner<br />

is paid the compliment of being a good representative of his<br />

or her country, and is assumed to be proud of this. The second toast<br />

could be to the guests’ home countries, to their families or family in<br />

general. Toasting mothers is mandatory, as is friendship, deceased<br />

relatives, existing and future children, peace, love, and the hostess.<br />

The tamada can combine topics into one toast, or split topics into<br />

several toasts. The more people present, the more formal the toasts.<br />

At evenings with close friends, the toasts are often quite witty and<br />

versant.com • 17

Tradition<br />

short. The course of toasting follows a variable thematic canon, which<br />

is accommodated to the specific occasion.<br />

The toast to the hostess, (normally the one who has prepared the<br />

meal) is usually the penultimate or last toast, and has certain implications<br />

for ‘opening up the closing’ of the evening.<br />

When such a toast is about to be offered, frequent attempts to delay<br />

its delivery can be observed, since this toast would end the evening.<br />

The time-order of the entire evening is thus reflected in the pattern<br />

of toasting. To a certain extent, every evening is prestructured by the<br />

pattern of toasting.<br />

Important toasts are marked by a shift of position. Whereas the<br />

tamada and all the other men rise to their feet, the women remain<br />

seated. Additionally, the relevance of a specific toast is indicated by<br />

the appropriate quantity of wine that is to be drunk in one gulp after<br />

its deliverance, and by the drinking-vessel used (glass vs. horn).<br />

Drinking a lot of alcohol is considered a necessary component of<br />

displaying masculinity. Since the tamada is required to empty his<br />

drinking-vessel completely after every toast, he must possess a high<br />

tolerance to alcohol — particularly on special occasions, when drinking-vessels<br />

are commonly made out of bull horns.<br />

Joyous Supra — ლხინის სუფრა<br />

Funeral Supra — ხელეჰი<br />

The pattern of marriage toasting is different from the pattern<br />

appropriate for toasting the birth of a child. Education, rhetorics,<br />

and a good sense of humor can all be demonstrated while<br />

delivering a toast. On a typical lxinis supra (happy banquet)<br />

with guests, the thematic sequence of toasting progresses<br />

approximately in the following fashion:<br />

• to our acquaintance and friendship<br />

• to the well-being of the guests, relatives and friends<br />

• to the family of the guests<br />

• to the parents and the older generation,<br />

• to the dead and the saints, (wine is poured<br />

onto a piece of bread for this toast)<br />

• to existing and yet unborn children,<br />

• to the women present at the table,<br />

• to love,<br />

• to the guests’ mothers,<br />

• to peace on earth,<br />

• to the hostess,<br />

• to the tamada himself.<br />

The following order for toasts is typical for a funeral supra:<br />

to the tamada:<br />

• to the person who has died<br />

• to his or her spouse (if dead)<br />

• to the person’s parents (if dead)<br />

• to the person’s grandparents (if dead)<br />

• to the person’s other dead relatives<br />

• to people from Georgia who died in the war<br />

• to Georgians who died abroad<br />

• to families who have no descendants<br />

• to the spouse of the deceased (if living)<br />

• to the children of the deceased (if living)<br />

• to the surviving parents<br />

• to the surviving siblings<br />

• to the surviving relatives<br />

• to the surviving friends and neighbors<br />

• to the other members of the supra<br />

• to people who have been good to<br />

the family of the deceased.<br />

18 • versant

“To be a good tamada demands close<br />

observation of the surrounding social world.”<br />

Talking stops when the tamada begins to give a toast. To continue<br />

talking is considered impolite. At a supra, informal talking is hardly<br />

possible, because the themes to be talked about are prestructured to a<br />

certain degree in accordance with the canonic order of toasting.<br />

Discussions keep getting interrupted by a toast. The tamada manages<br />

to start the toasting by suddenly raising his glass and calling a<br />

formula, or xalxo (folks), or some personal form of address. Anyone<br />

speaking is then expected to stop in order to listen to the tamada.<br />

The toast normally stands out distinctly from other talking activity by<br />

gestures, intonation, position shifting, and addressing.<br />

Although the toasts are well-known over generations, there is never<br />

one toast like the other. The tamada produces performances that are<br />

similar rather than identical, as is typical for oral genres. Changes<br />

from one concrete performance to the next are determined by the<br />

preferences of the individual speaker, his perception of the audience’s<br />

taste, and sometimes by the audience’s open reaction. The audience is<br />

constantly taken into consideration.<br />

There is no formal teaching in how to give a toast; one trains to<br />

become a good toast giver by listening to the toasts given at the table.<br />

People talk about the toasts delivered during an evening later on. The<br />

evaluation of special toasts is also a common theme. Criteria of judgment<br />

include the manner of delivery, the balance of traditional and<br />

creative performance features, the fluency of speaking, and the sensitive<br />

finding of social qualities to praise.<br />

When a marriage is discussed, one necessarily also talks about the<br />

excellence and originality of the toasts presented on that occasion.<br />

Excellence is judged by the perfect fulfillment of the generic norms,<br />

while originality is judged by the creativity used within the given<br />

procedure. Both should be optimally matched.<br />

Praise to the people present and to those absent is a central function<br />

of the toasts. Since praise is a social endeavor, the tamada has to<br />

be a good social observer. The person who is the subject of the toast<br />

is honored by the whole group; thus, the genre helps to establish and<br />

re-establish social bonds and norms. To be a good tamada demands<br />

close observation of the surrounding social world.<br />

By praising known and unknown qualities of living and deceased<br />

people, a good tamada shows that he is more than simply a man of<br />

words. He is the one who makes people see new dimensions of the<br />

subject, and who keeps the memory of the deceased alive.<br />

The tamada has to guarantee that the dinner ends with good feelings<br />

among all the participants, a goal which is highly valued and<br />

respected by Georgians.<br />

Formulae are used in every toast, and there is a fixed set that provides<br />

a stock for every tamada, for example, “me minda shemogtavazot,<br />

sadghegrzelo” (I want to offer you a toast), “kargad qopna” (to their<br />

well-being), “ janmrteloba vusurvot” (I wish them health), “bedniereba<br />

vusurvot” (I wish them good luck), “mshoblebs dagilocavt sul qvelas”<br />

(I bless all your parents/best wishes for all your parents), “ghmertma<br />

gaumarjos sul qvelas” (God shall give all of them his favor).<br />

However, a toast that consists only of formulaic phrases is considered<br />

to be a poor one. A good tamada combines traditional and creative<br />

phrases. He can give voice to his own individuality, and at the same<br />

time be sensitive to the audience’s pleasure.<br />

Men gather for a funeral supra to honor the<br />

passing of a member of their community.<br />

versant.com • 19

Photo © Corinne Thrash

A ritualized toast-competition, called alaverdi, is often established<br />

between the men at the table. The tamada talks about a specific topic,<br />

and the other men must modify this topic in the subsequent toasts.<br />

When one alaverdi round is completed the tamada must decide who<br />

will open the next round. His decision should be based on the criteria<br />

of the toast’s originality, its formulation, and the approval it received<br />

from the table. Table rhetoric is an important sign of Georgian masculinity.<br />

Men who cannot take part are considered insufficient, weak,<br />

or unmanly.<br />

In the special form of alaverdi toasting competition, the tamada<br />

symbolically grants other men his power of speech. Whomever he<br />

hands the drink-horn or the glass to becomes temporarily the tamada,<br />

and as such, the center of attraction of the dinner-party. He is then<br />

expected to vary and elaborate on the topic already determined by<br />

the head-tamada.<br />

In formal contexts, the competition is about ‘who is the best.’ The<br />

head-tamada, taking into consideration the approval of the people<br />

present, judges who was best. In the next round, the winner is given<br />

the right to speak as the second tamada. It is frequently very obvious<br />

that the head-tamada himself was the best, and he laboriously tries to<br />

remain in that position.<br />

The audience at the table can express their appreciation of specific<br />

toasts by paying compliments, clapping, or making non-verbal gestures<br />

(however, this does not occur in the following example). In alaverdidrinking,<br />

it becomes especially apparent that the power of words is a<br />

sign of masculinity in Georgian culture.<br />

Two women ‘vakhtanguri’ at a wedding, symbolically<br />

drinking wine from a pair of high heels.<br />

versant.com • 21

Politics<br />

In July 2015, Russian backed forces moved the boundary fence between<br />

Russian-occupied South Ossetia and Georgia — placing more Georgian<br />

territory under Russian control. Georgians refer to this as the creeping<br />

occupation, and several people who unfortunately live in the area now<br />

have a different citizenship.<br />

Simon Ostrovsky traveled to Georgia to see how the country is<br />

handling Russia’s quiet invasion, and meet those getting caught in<br />

the crossfire.<br />

“I am 82 years old. For over 80 years I’ve been a citizen of Georgia.<br />

And now they’ve made me a Russian citizen. I don’t know who’s to<br />

blame. The Russians say it’s their territory. I will never leave Georgia.<br />

They can kill me, they can hang me if they like.”<br />

We’re outside the village of Bershueti, which is on Georgian territory<br />

right next to the demarcation line between Georgia and South<br />

Ossetia, and just yesterday two shepherds were actually captured by<br />

troops from the other side.<br />

South Ossetia is one of two regions of Georgia that Russia took<br />

over in a war in 2008. This summer Russia took things a step further.<br />

It posted fresh border markers and made claim to a mile-long section<br />

of a major U.S.-backed BP operated oil pipeline. Now Russia has the<br />

capability to sabotage its operation any time it wants to. Moscow now<br />

controls about a quarter of Georgia’s total territory. They arrest anyone<br />

who strays across this new de facto border. Georgians are calling it<br />

the Creeping Occupation.<br />

The entire world considers the land on both sides of this fence to<br />

belong to Georgia. Only Russia considers the land on one side to be<br />

part of an independent country, known as South Ossetia. But the<br />

fence ends, which is why it is not entirely clear for the local villages<br />

herding their sheep where they are allowed to go and where they’re<br />

not supposed to be.<br />

A young shepherd from the area agreed to take us around.<br />

Could you tell us what happened to Murazi yesterday?<br />

“Yes, Murazi [was taken] over there to Tskhinvali [the capital of<br />

the de facto state].”<br />

Two Georgians, Ivane Sekhniashvili and Murazi Javakhishvili,<br />

were out shepherding a herd in late October when armed men seized<br />

The Russians<br />

Are Coming:<br />

Georgia’s Creeping Occupation<br />

by Simon Ostrovsky

them in this area on November 3rd. Nobody has heard from them<br />

since, but everyone assumed they had been taken to jail in the rebel<br />

capital Tskhinvali.<br />

We were being watched. In South Ossetia alone, Russia has built 19<br />

border bases, and one of them is a mere 40 miles from Georgia’s capital,<br />

Tbilisi. Our guide was getting nervous about being interviewed<br />

so close to the territory separation fence and one of the Russian border<br />

bases, so we headed down into the nearby village to meet the detained<br />

shepherd’s family.<br />

“He was on his way to the pasture. He was on our side of the border,<br />

still far from it,” Meri Javakhishvili said (the wife of one of the detained<br />

shepherds). “They took him to the other side and photographed him<br />

there. I don’t know exactly who took him, but there are Russians over<br />

there, and I believe they got him. I don’t know what to do. I can’t<br />

imagine what steps to take, what’s necessary. If you ask around the<br />

village there is no harder working person than my husband,” Meri says<br />

as she wipes the tears from her cheeks. “He didn’t have bad relations<br />

with the Russians when there was peace between us. On the contrary,<br />

they always treated each other with respect.”<br />

These detentions are a huge issue for people living along the new<br />

de facto borderline. According to rebel South Ossetia’s own statistics<br />

more than 320 people have been detained so far for what they call<br />

“In South Ossetia alone, Russia<br />

has built 19 border bases.”<br />

“illegal crossings”. But Russia’s border creation policy is causing other<br />

problems as well.<br />

One of the consequences of the so-called “borderization policy” is<br />

that it doesn’t always follow the boundaries even of villages. This barbed<br />

wire fence was put right in the middle of the village of Khurvaleti, and<br />

it in fact even goes through the yard of a Georgian resident who has<br />

ended up on the other side.<br />

Russian forces on break as they deploy troops<br />

to build the next installment of fencing.

Signs against the newly constructed fence warn<br />

residents and other wanderers to keep clear.<br />

“I’ve lived here for 80 years,” says Dato Vanishvili. “I am 82 years<br />

old. For over 80 years I’ve been a citizen of Georgia. And now they’ve<br />

made me a Russian citizen [with this fence]. What kind of life is this<br />

to live? Why am I being hassled like this? They put this fence up in<br />

one month’s time. Where am I to go? I barely managed to build this<br />

house in my lifetime. If I leave they will take the roof off and destroy<br />

the whole house. If I try to cross the borderline they will arrest me,<br />

take me to Tskhinvali and fine me, and how am I supposed to pay<br />

them? If they don’t fine me they would throw me in jail. Bless the<br />

[Georgian] police officers, they have helped me a lot, otherwise I’d be<br />

dead. The other day they brought me a loaf of bread. They passed it to<br />

“The war really put people in a<br />

difficult situation. It’s not only<br />

this village, all of Georgia is<br />

going backwards.”<br />

me like this [demonstrating reaching through the barbed wire fence].<br />

I don’t know who’s to blame. The Russians say it’s their territory. But<br />

for 80 years it wasn’t theirs, so how can it be theirs now? How am I<br />

to leave my house now? Who would I leave this house to? I finally<br />

finished building it [after all these years]. I will never leave Georgia.<br />

They can kill me, they can hang me if they like.”<br />

“We know that the Russian Federation of South Ossetians erected<br />

the fences; Georgians call it the Creeping Occupation,” says Kestutis<br />

Jankauskas (Ambassador of the European Union Monitoring Mission).<br />

“The other side calls it building the state border infrastructure. These<br />

things impede people’s daily lives. Can’t they visit their graveyards?<br />

They sometimes cannot do that because the graveyard is across [the<br />

border]. Then people cannot have irrigation [for their farms] which<br />

they used to have in previous years. They cannot visit relatives, so it<br />

has a direct impact on their daily lives. In some parts it’s hundreds of<br />

families effected. [With regard to the recent incident of two shepherds<br />

being detained] usually people spend one or two nights in detention<br />

and they pay a fine of about 2,000 rubles and they are released within<br />

about 48 hours; [in about 90% of the cases].”<br />

But by now the shepherds had been missing for three days. We went<br />

to check with the family to see if they had heard any news. “Everybody<br />

is hoping for the best,” said David Javakhishvili (a son of one of the<br />

detained shepherds). “[A fine of 2,000 rubles] may not be much for<br />

some people, but for people who are struggling it’s definitely a lot. The<br />

war really put people in a difficult situation. It’s not only this village,<br />

all of Georgia is going backwards.”<br />

We are now on a patrol with the European Union Monitoring<br />

Mission. They are a delegation from the European Union which goes<br />

around and checks up on all of the activities around the South Ossetian<br />

border, and they are going to show us around today to tell us what’s<br />

been happening recently.<br />

“In front of us you can see the IDP camp, Nadarbazevi,” says Gino<br />

Colazio (an EU Monitor). “And to the left of the Nadarbazevi camp<br />

we have a newly installed green sign. And on the right side of the IDP<br />

camp you can see another new green sign, which is just 500 meters<br />

(1,640 feet) from the [main] highway. We are very close to the Baku-<br />

Supsa pipeline.” This is the southernmost point that the Russians and<br />

24 • versant

Putin’s face was graffitied on the side of dumpsters<br />

throughout Tbilisi after the war in 2008.<br />

South Ossetians have claimed. It’s just a couple hundred yards from<br />

the main highway that goes through Georgia, and it’s also south of<br />

the Baku-Supsa pipeline, which was a major U.S.-backed project.<br />

Back in 1999 when the 560 million dollar Baku-Supsa pipeline was<br />

inaugurated the U.S. hailed it as a major breakthrough for the independence<br />

of Georgia and the oil-producing Azerbaijan. “President<br />

Clinton, on behalf of the entire administration, played an especially<br />

important role so that this large-scale project could develop,” stated<br />

then-President of Georgia, Eduard Shevardnadze.<br />

For now, Russia has simply marked the area as its own, but if it were<br />

to disrupt the pipeline or the main highway it would be a catastrophe<br />

for Georgia. Georgia used to be a staunch U.S. ally. They even named<br />

one of the major streets of the capital after George W. Bush. But after<br />

the war with Russia in 2008 it seems like their pro-western resolve<br />

may be wavering. [The Georgian government] still goes through the<br />

motions of being in the western camp, placing EU flags on everything,<br />

sending Georgian troops out on NATO missions around the<br />

world, but their response to Russia’s expanding territorial claims inside<br />

Georgia have been so weak that some people think Georgia’s current<br />

leadership may have actually sold out to Russia.<br />

Speaking of NATO, the alliance was about to open a facility in<br />

Georgia, so we went there to meet top officials and ask them what<br />

they were going to do about Russia’s expanding border along Georgia’s<br />

South Ossetian state. All of the country’s top political leadership<br />

including the Prime Minister, the President, as well as the Defense<br />

Minister are here, and they have invited NATO’s top commander, the<br />

Secretary General, to attend as well. So with this gathering NATO is<br />

trying to show that it is still committed to a relationship with Georgia<br />

even though the Russian troops are just about 100 kilometers away<br />

from here installing more fencing.<br />

With Russian troops so close Georgia’s leader felt that it was important<br />

to say the training center wasn’t a threat to them. “I would like to<br />

point out that the activities of the training center are not in any way<br />

directed against any of the neighboring countries,” states Georgia’s<br />

Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili. “Moreover, it will serve for regional<br />

security, stability and peace-building.”<br />

“This [new NATO facility] is something that was planned and decided<br />

upon well before the events [of new borderlines being drawn along<br />

South Ossetia by Russian troops],” stated Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary<br />

“Some people think Georgia’s<br />

current leadership may have<br />

actually sold out to Russia.”<br />

General of NATO. “This is part of what we call the Comprehensive<br />

Package, the increased cooperation between NATO and Georgia.”<br />

Even NATO’s leader doesn’t want to anger Russia.<br />

Our correspondent asked Tinatin Khidasheli, the Defense Minister<br />

of Georgia, why Georgian forces have taken no action against the<br />

recent territorial claims that the Russian and South Ossetian forces<br />

have been making near major Georgian infrastructure. “Georgia is<br />

taking every responsible action for the security of its country, and<br />

responsible for not allowing war on its own territory. These are diplomatic<br />

actions that we are taking and it is the actuation of the world<br />

versant.com • 25

Politics<br />

community for the Georgian cause, and we are not going to allow<br />

Russia to provoke us into another war.” Upon being pressed to respond<br />

to critics who claim she (and others in the administration) have a pro-<br />

Russian policy, Khidasheli countered by saying “I’m not responsible for<br />

every craziness that I hear. There is no human being in this country<br />

you will find (and you can go out in the street and ask my name) who<br />

will say [that our policy is pro-Russian].”<br />

All of the Georgian officials that we spoke to seemed to be pushing<br />

the line that it was dangerous to provoke Russia by reacting to its latest<br />

moves, but not everybody in Georgia sees things that way. We’ve<br />

come to the National Movement headquarters. They are the avowedly<br />

anti-Russian party, which is now in opposition. “The Georgian Defense<br />

Minister represents the fraction of their coalition who is rhetorically<br />

the most pro-western, so they play a fig leaf role in that,” says Giga<br />

Bokeria, Foreign Secretary of the United National Movement. “We<br />

welcome the NATO training facility. After the Russian invasion in<br />

Ukraine and after there is [now] finally an awakening to Putin’s challenge<br />

there were certain steps made by the European Alliance and<br />

generally the west, and one of its steps with respect to Georgia was<br />

this [NATO] center, which is good but not sufficient. But you cannot<br />

have a concept in which your goal is to say “we are just doing nothing<br />

and we are good guys, and our western friends will tell us ‘well<br />

good, you are not creating another headache for us’”. Repeating every<br />

day, day in and day out “Russia will crush you, Russia will crush you”<br />

makes no point, we all know that this is a danger and that Georgia will<br />

Khurvaleti IDP camp, stuck between Russian-occupied Ossetia<br />

and Georgia’s main highway. Above: two of the camp’s residents.

“Repeating every day, day in and day out “Russia will crush you, Russia<br />

will crush you” makes no point, we all know that this is a danger and<br />

that Georgia will never be able on its own to win a war against Russia.”<br />

never be able on its own to win a war against Russia. We don’t want<br />

the war. What we should do is [put] this issue high on the international<br />

agenda, and this is completely not right now. Secondly, on the<br />

ground there should be much more reserved but resistance by law<br />

enforcement towards kidnappings, towards movement of the occupation<br />

[border] line.”<br />

So what has Georgia’s ‘go softly’ approach towards Russia actually<br />

achieved? I invited the Minister of Reconciliation, Paata Zakareishvili,<br />

to the borderlands to ask him. His job is to make the ethnic minorities<br />

living under Russian control want to return to Georgia. “The Russian<br />

occupation forces behave, from time to time, in a provocative way in<br />

order to increase tensions in Georgian society and to direct the world’s<br />

attention to the idea that there are a lot of problems in Georgia. Thank<br />

God, we have been able to refrain from reacting to these provocations.<br />

We’ve been in power for three years now. During this time, Russia has<br />

not been able to draw us into a situation that would lead to escalation.”<br />

Recently Zakareishvili said that Vladimir Putin, the Commanderin-Chief<br />

of the Russian forces, is not an enemy of Georgia. When<br />

questioned about this considering that Russia currently occupies about<br />

a quarter of Georgian territory he stated, “I said that a man cannot<br />

be the enemy of a state. That’s totally different. A man cannot be the<br />

enemy of a state. Only a state can be the enemy of a state.” In response<br />

to questions of Georgian civilians having their land divided by a border<br />

fence Zakareishvili said, “What you saw is more of a positive than a<br />

negative. Under [the last president of Georgia], Saakashvili, that person<br />

might not be living there. He might not even be alive.”<br />

Finally we got some good news. The rebels were releasing the<br />

Georgian shepherds to the Georgian authorities. They were brought to<br />

A solitary refugee’s grave sits in an abandoned<br />

farm near the border fence Russia has installed.<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash

Dato Vanishvili, a Georgian citizen whose land<br />

is now divided between the two governments.<br />

“So the question is, did Russia build the new fences to keep Georgians<br />

out or Russians and their ethnic Ossetian allies in?”<br />

a police station to give a statement about their four-day ordeal. “Their<br />

border was over on that side. I was close to their side,” says Murazi<br />

Javakhishvili. “[The soldiers] came and told us, ‘Come quickly, come<br />

with us!’ ‘What did we do?’ I asked. We hadn’t done anything. We<br />

weren’t on their territory. We were right next to it. And they came<br />

with dogs and automatic guns. Not follow them? Of course we had<br />

to follow them. On that road they drove like they were hauling sand<br />

instead of people. I told them to go slowly. ‘Don’t throw me out,’ I<br />

said. What can we do? It was what it was. We suffered. In old age<br />

they put me through this. I have a good grandchild. He gives me<br />

hope and inspires me to keep living. We were close, we had to follow<br />

the herd when they suddenly swarmed us like bandits. And they<br />

told us, ‘Come quickly, come quickly!’ How could I not have gone?<br />

What could I do?”<br />

Hundreds of people like Murazi Javakhishvili are rounded up by<br />

Russian border guards every year. But according to separatist South<br />

Ossetia’s own KGB most of these arrests are of South Ossetians and<br />

Russians picked up by the Russian border guards for trying to come<br />

into Georgia. So the question is, did Russia build the new fences to<br />

keep Georgians out or Russians and their ethnic Ossetian allies in?

Photo © Corinne Thrash

Ghost<br />

of the<br />

Vine<br />

In Georgia, science probes the<br />

roots of winemaking<br />

by Paul Salopek<br />

Meet Maka Kozhara: a wine expert. Young, intelligent, friendly.<br />

Kozhara sits in an immense cellar in a muddy green valley in the<br />

Republic of Georgia. The cellar lies beneath an imitation French<br />

château. The vineyards outside, planted in gnarled rows, stretch away for<br />

miles. Once, in the late 19th century, the château’s owner, a Francophile,<br />

a vintner and eccentric Georgian aristocrat, pumped barrels of homebrewed<br />

champagne through a large outdoor fountain: a golden spray<br />

of drinkable bubbles shot into the air.<br />

“It was for a party,” Kozhara says. “He loved wine.”

Culture<br />

Traditional winemaking vessels are still in use<br />

at Pheasant’s Tears Winery in Sighnaghi.<br />

Kozhara twirls a glass of wine in her hand. She holds the glass up<br />

to the ceiling light. She is interrogating a local red — observing what<br />

physicists call the Gibbs-Maranoni Effect: How the surface tension of<br />

a liquid varies depending on its chemical make-up. It is a diagnostic<br />

tool. If small droplets of wine cling to the inside of a glass: the wine<br />

is dry, a high-alcohol vintage. If the wine drips sluggishly down the<br />

glass surface: a sweeter, less alcoholic nectar. Such faint dribbles are<br />

described, among connoisseurs, as the “legs” of a wine. But here in<br />

Georgia wines also possess legs of a different kind. Legs that travel.<br />

That conquer. That walk out of the Caucasus in the Bronze Age.<br />

The taproots of Georgia’s wine are muscular and very old. They<br />

drill down to the bedrock of time, into the deepest vaults of human<br />

memory. The earliest settled societies in the world — the empires of<br />

the Fertile Crescent, of Mesopotamia, of Egypt, and later of Greece<br />

and Rome — probably imported the secrets of viticulture from these<br />

remote valleys, these fields, these misty crags of Eurasia. Ancient<br />

Georgians famously brewed their wines in clay vats called kvevri.<br />

Today, these bulbous amphoras are still manufactured. Vintners still<br />

fill them with wine. The pots dot Georgia like gigantic dinosaur eggs.<br />

They are under farmers’ homes, in restaurants, in parks, in museums,<br />

outside gas stations. Kvevri are a symbol of Georgia: a source of pride,<br />

unity, strength. They deserve to appear on the national flag. It has<br />

been said that one reason why Georgians never converted en masse to<br />

Islam (Arabs invaded the region in the seventh century) was because<br />

of their attachment to wine. Georgians refused to give up drinking.<br />

Kozhara pours me a glass. It is her winery’s finest vintage, ink-dark,<br />

dense. The liquid shines in my hand. It exhales an aroma of earthy<br />

tannins. It is a scent that is deeply familiar, as old as civilization, that<br />

goes immediately to the head.<br />

“Wine” — Kozhara declares flatly — “is our religion.”<br />

To which the only possible response is: Amen.<br />

“We aren’t interested in proving that winemaking was born in<br />

Georgia,” insists David Lordkipanidze, the director of the Georgia<br />

National Museum, in Tbilisi. “That isn’t our goal. There are much<br />

better questions to ask. Why did it start? How did it spread across<br />

the ancient world? How do you connect today’s grape varieties to the<br />

wild grape? These are the important questions.”<br />

Lordkipanidze oversees a sprawling, multinational, scientific effort<br />

to unearth the origins of wine. The Americans have NASA. Iceland has<br />

BjÖrk. But Georgia has the “Research and Popularization of Georgian<br />

Grape and Wine Culture” project. Archaeologists and botanists from<br />

Georgia, geneticists from Denmark, Carbon-14 dating experts from<br />

Israel, and other specialists from the United States, Italy, France and<br />

Photographs © Corinne Thrash

A family’s home in western Georgia is decorated<br />

with generations of wine making tools.<br />

Canada have been collaborating since early 2014 to explore the primordial<br />

human entanglements with the grapevine.<br />

Patrick McGovern, a molecular archaeologist from the University<br />

of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and a member of this intellectual<br />

posse, calls wine perhaps the most “consequential beverage” in the<br />

story of our species.<br />

“Imagine groups of hunter-gatherers meeting for the first time,”<br />

McGovern says. “Wine helps to bring people together. It’s social lubrication.<br />

Alcohol does this.”<br />

Human beings have been consuming alcohol for so long that 10<br />

percent of the enzymes in our livers have evolved to metabolize it into<br />

energy: a sure sign of tippling’s antiquity. The oldest hard evidence of<br />

intentional fermentation comes from northern China, where chemical<br />

residues in pottery suggest that 9,000 years ago our ancestors quaffed<br />

a dawn cocktail of rice, honey and wild fruit.<br />

Grape wines came a bit later. McGovern surmises that their innovation<br />

was accidental: wild grapes crushed at the bottom of a container,<br />

their juices gone bad, partly digested by airborne yeasts. For thousands<br />

of years, the fermentation process remained a mystery. This gave<br />

wine its otherworldly power. “You have a mind-altering substance that<br />

comes out of nowhere,” McGovern says, “and so this drink starts to<br />

feature at the center of our religions. It became embedded in life, in<br />

family, in faith. Even the dead started to be buried with their wine.”<br />

From the beginning, wine was more than a mere intoxicant. It was<br />

an elixir. Its alcohol content and tree resins, added in ancient times as<br />

wine preservatives, had anti-bacterial qualities. In ages when sanitation<br />

was abysmal, drinking wine — or mixing it with water — reduced<br />

disease. Wine saved lives.<br />

“Cultures that made the first wines were productive, rich,” says<br />

Mindia Jalabadze, a Georgian archaeologist. “They were growing<br />

wheat and barley. They had sheep, pigs, and cattle — they bred them.<br />

Life was good. They also hunted and fished.”<br />

Jalabadze is talking about a Neolithic culture called Shulaveri-<br />

Shomu whose mound sites in Georgia arose during a wet cycle in the<br />

southern Caucasus and date back to first inklings of agriculture, before<br />

the time of metal. The villagers used stone tools, tools of bone. They<br />

crafted gigantic pots the size of refrigerators. Such vessels — precursors<br />

to the fabled kvevri — held grains and honey, but also wine. How<br />

can we know? One such pot is decorated with bunches of grapes.<br />

Biochemical analyses of the pottery, carried out by McGovern, shows<br />

evidence of tartaric acid, a telltale clue of grape brewing. These artifacts<br />

are 8,000 years old. Georgia’s winemaking heritage predates<br />

other ancient wine-related finds in Armenia and Iran by centuries.

Photo © Corinne Thrash

This year, researchers are combing the sites of Shulaveri-Shomu for<br />

prehistoric grape pips.<br />

One day, I visit the remains of a 2,200-year-old Roman town in<br />

central Georgia: Dzalisa. The beautiful mosaic floors of a palace are<br />

holed, bizarrely pocked, by clay cavities large enough to hold a man.<br />

They are kvevri. Medieval Georgians used the archaeological ruins<br />

to brew wine. South of Tbilisi, on a rocky mesa above a deep river<br />

gorge, lies the oldest hominid find outside Africa: a 1.8-million-yearold<br />

repository of hyena dens that contain the skulls of Homo erectus.<br />

In the ninth or tenth centuries, workers dug a gigantic kvevri into the<br />

site, destroying priceless pre-human bones.<br />

Georgia’s past is punctured by wine. It marinates in tannins.<br />

For more than two years, I have trekked north out of Africa. More<br />

than 5,000 years ago, wine marched in the opposite direction, south<br />

and west, out of its Caucasus cradle.<br />

“Typical human migrations involved mass slaughter,” says Stephen<br />

Batiuk, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto. “You know,<br />

migration by the sword. Population replacement. But not the people<br />

“Wine” — Kozhara declares flatly — “is our religion.”<br />

Kvevri buried beneath the bricks are filled with<br />

grape juice and ferment for months to years.

Giorgi checks the modernized kvevri system<br />

he and his partner designed for preparing wine.<br />

who brought wine culture with them. They spread out and then lived<br />

side-by-side with host cultures. They established symbiotic relationships.”<br />

Batiuk is talking about an iconic diaspora of the classical world: the<br />

expansion of Early Trans-Caucasian Culture (ETC), which radiated<br />

from the Caucasus into eastern Turkey, Iran, Syria, and the rest of the<br />

Levantine world in the third millennium B.C.<br />

Batiuk was struck by a pattern: Distinctive ETC pottery pops up<br />

wherever grape cultivation occurs.<br />

“These migrants seemed to be using wine technology as their contribution<br />

to society,” he says. “They weren’t ‘taking my job.’ They were<br />

showing up with seeds or grape cuttings and bringing a new job—viticulture,<br />

or at least refinements to viticulture. They were an additive<br />

element. They sort of democratized wine. Wherever they go, you see<br />

an explosion of wine goblets.”<br />

ETC pottery endured as a distinctive archaeological signature for<br />

700 to 1,000 years after leaving the Caucasus. This boggles experts<br />

such as Batiuk. Most immigrant cultures become integrated, absorbed,<br />

and vanish after just three generations. But there is no mystery here.<br />

On a pine-stubbled mountain above Tbilisi, a man named Beka<br />

Gotsadze home-brews wine in a shed outside his house.<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash

“ It became embedded<br />

in life, in family, in faith.<br />

Even the dead started<br />

to be buried with wine.”<br />

Gotsadze: big, affable, red-faced. His is one of tens of thousands of<br />

ordinary Georgian families who still squeeze magic from Vitis vinifera<br />

for their own enjoyment. He uses clay kvevri buried in the earth;<br />

the hill under his house is his incubator. He pipes coils of household<br />

tap water around the jars to control the fermentation. He employs<br />

no chemicals, no additives. His wines steep in the darkness the way<br />

Georgian wine always has: the grapes mashed together with their<br />

skins, their stems.<br />

Gotsadze says, “You put it in the ground and ask God: ‘Will this<br />

batch be good?’” He says: “Every wine producer is giving you his heart.<br />

My kids help me. They are giving you their hearts. The bacteria that<br />

ferment? They came on the wind! The clouds? They are in there. The<br />

sun is in there. The wine holds everything!”<br />

Gotsadze took his family’s wines to a competition in Italy once, to<br />

be judged. “The judge was amazed. He said, ‘Where have you been<br />

hiding all this time?’ I said, ‘Sorry, you know, but we’ve been a little<br />

busy over here, fighting the Russians!’”<br />

And at his raucous dinner table, a forest of stemmed glasses holds<br />

the dregs of tavkveri rosé, chinuri whites, saperavi reds. The eternal ETC<br />

thumbprint is there.

Photo © Corinne Thrash

Medieval<br />

Mountain<br />

Hideaway<br />

In the Svaneti region of Georgia’s Caucasus<br />

Mountains, the ways of the Middle Ages live on.<br />

By Brook Larmer

Roads wind by sharp cliffs to Mestia in Upper<br />

Svaneti. Previous page: the village of Cholashi.<br />

The men gather at dawn near the stone tower, cradling knives in callused hands. After<br />

a night of snowfall — the first of the season in Svaneti, a region high in Georgia’s<br />

Caucasus Mountains — the day has broken with icy clarity. Suddenly visible above<br />

the village of Cholashi, beyond the 70-foot-high towers that form its ancient skyline,<br />

is the ring of 15,000-foot peaks that for centuries has kept one of the last living<br />

medieval cultures barricaded from the outside world.<br />

Silence falls as Zviad Jachvliani, a burly former boxer with a salt-and-pepper beard,<br />

leads the men — and one recalcitrant bull — into a yard overlooking the snowdusted<br />

valley. No words are needed. Today is a Svan feast day, ormotsi, marking the<br />

40th day after the death of a loved one, in this case Jachvliani’s grandmother. The<br />

men know what to do, for Svan traditions — animal sacrifices, ritual beard cutting,<br />

blood feuds — have been carried out in this wild corner of Georgia for more than a<br />

thousand years. “Things are changing in Svaneti,” Jachvliani, a 31-year-old father of<br />

three, says. “But our traditions will continue. They’re part of our DNA.”<br />

In the yard he maneuvers the bull to face east, where the sun has crept above the<br />

jagged crown of Mount Tetnuldi, near the Russian border. Long before the arrival of<br />

The men gather at dawn near the stone tower, cradling knives in callused hands. After<br />

a night of snowfall — the first of the season in Svaneti, a region high in Georgia’s<br />

“Things are changing in<br />

Svaneti,” Jachvliani says. “But<br />

our traditions will continue.<br />

They’re part of our DNA.”<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

Caucasus Mountains — the day has broken with icy clarity. Suddenly visible above<br />

the village of Cholashi, beyond the 70-foot-high towers that form its ancient skyline,<br />

is the ring of 15,000-foot peaks that for centuries has kept one of the last living<br />

medieval cultures barricaded from the outside world.<br />

Silence falls as Zviad Jachvliani, a burly former boxer with a salt-and-pepper beard,<br />

leads the men — and one recalcitrant bull — into a yard overlooking the snow-dusted<br />

valley. No words are needed. Today is a Svan feast day, ormotsi, marking the 40th<br />

day after the death of a loved one, in this case Jachvliani’s grandmother. The men<br />

know what to do, for Svan traditions — animal sacrifices, ritual beard cutting, blood<br />

feuds — have been carried out in this wild corner of Georgia for more than a thousand<br />

years. “Things are changing in Svaneti,” Jachvliani, a 31-year-old father of three, says.<br />

“But our traditions will continue. They’re part of our DNA.”<br />

In the yard he maneuvers the bull to face east, where the sun has crept above the<br />

jagged crown of Mount Tetnuldi, near the Russian border. Long before the arrival<br />

of Christianity in the first millennium, Svans worshipped the sun, and this spiritual<br />

force — along with its derivative, fire — still figures in local rituals. As the men with<br />

knives gather in front of him, Jachvliani pours a shot of moonshine on the ground, an<br />

offering to his grandmother. His elderly uncle chants a blessing. And then his cousin,<br />

cupping a candle against the wind, lights the hair on the bull’s forehead, lower back,<br />

and shoulders. It is the sign of the cross, rendered in fire.<br />

versant.com • 41

History<br />

After the blessing, the men lasso one of the bull’s legs with a rope and, heaving in<br />

unison, truss the bellowing beast over the branch of an apple tree. Jachvliani grabs<br />

its horns, while another villager, unsheathing a sharpened dagger, kneels down next<br />

to the bull and, almost tenderly, feels for the artery in its neck.<br />

Over the course of history many powerful empires — Arab, Mongol, Persian,<br />

Ottoman — sent armies rampaging through Georgia, the frontier between Europe<br />

and Asia. But the home of the Svans, a sliver of land hidden among the gorges of<br />

the Caucasus, remained unconquered until the Russians exerted control in the mid-<br />

19th century. Svaneti’s isolation has shaped its identity — and its historical value.<br />

In times of danger, lowland Georgians sent icons, jewels, and manuscripts to the<br />

mountain churches and towers for safekeeping, turning Svaneti into a repository of<br />

early Georgian culture. The Svans took their protective role seriously; an icon thief<br />

could be banished from a village or, worse, cursed by a deity.<br />

In their mountain fastness the people of Svaneti have managed to preserve an even<br />

older culture: their own. By the first century B.C. the Svans, thought by some to be<br />

descendants of Sumerian slaves, had a reputation as fierce warriors, documented in<br />

the writings of the Greek geographer Strabo. (Noting that the Svans used sheepskins<br />

to sift for gold in the rivers, Strabo also fueled speculation that Svaneti might have<br />

“Nowhere else can you find<br />

a place that carries on the<br />

customs and rituals of the<br />

European Middle Ages.”<br />

been the source of the golden fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts.) By the time<br />

Christianity arrived, around the sixth century, Svan culture ran deep — with its own<br />

language, its own densely textured music, and complex codes of chivalry, revenge,<br />

and communal justice.<br />

If the only remnants of this ancient society were the couple of hundred stone towers<br />

that rise over Svan villages, that would be impressive enough. But these fortresses,<br />

built mostly from the 9th century into the 13th, are not emblems of a lost civilization;<br />

they’re the most visible signs of a culture that has endured almost miraculously<br />

through the ages. The Svans who still live in Upper Svaneti — home to some of the<br />

highest and most isolated villages in the Caucasus — hold fast to their traditions of<br />

singing, mourning, celebrating, and fiercely defending family honor. “Svaneti is a<br />

living ethnographic museum,” says Richard Bærug, a Norwegian academic and lodge<br />

owner who’s trying to help save Svan, a largely unwritten language many scholars<br />

believe predates Georgian, its more widely spoken cousin. “Nowhere else can you<br />

find a place that carries on the customs and rituals of the European Middle Ages.”<br />

What happens, though, when the Middle Ages meet the modern world? Since<br />

the last years of Soviet rule a quarter century ago, thousands of Svans have migrated<br />

to lowland Georgia, fleeing poverty, conflict, natural disasters — and criminal<br />

gangs. In 1996, when UNESCO bestowed World Heritage status on the highest<br />

cluster of Svan villages, Ushguli, the lone road that snakes into Svaneti was so terrorized<br />

by bandits that few dared to visit. Security forces busted the gangs in 2004.<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

42 • versant

Photo © Corinne Thrash

And now the government is implementing a plan to turn this medieval mountain<br />

zone into a tourist magnet.<br />

Svaneti arguably has seen more change in the past few years than in the past<br />

thousand. It’s not just the vans full of foreign backpackers discovering the region’s<br />

pristine trekking routes. In 2012 the government installed power lines to light up even<br />

the remotest villages. The road that links most villages of Upper Svaneti will soon<br />

be paved all the way to Ushguli. Frenzied construction has transformed the sleepy<br />

regional hub of Mestia into a faux Swiss resort town lined with clapboard chalets<br />

and bookended by hyper modern government buildings and an airport terminal<br />

out of The Jetsons. Meanwhile on the flanks of Mount Tetnuldi, directly across<br />

the river from Jachvliani’s home in Cholashi, one of Georgia’s largest ski resorts is<br />

beginning to take shape.<br />

Perhaps it makes some kind of karmic sense that the mountains and stone towers<br />

that kept outsiders at bay for all these centuries should now be enlisted to lure them<br />

in. But will all this change save the isolated region — or doom it?<br />

Bavchi Kaldani, the old family patriarch in Adishi, speaks in a hoarse whisper,<br />

but his words — in the abrupt cadences of Svan — land with force: “If I stop, I’ll die.”<br />

Even at age 86, with gnarled hands and a stooped back, Kaldani insists on carrying<br />

on the hard labor of Svan village life: chopping wood with a heavy ax, scything grass<br />

for his animals’ winter rations, and repairing his family’s stone tower.<br />

“My family has lived here for<br />

more than 1,200 years,” he<br />

says. “How could I let my<br />

village disappear?”<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

It’s a measure of the precariousness of mountain life that Kaldani too was once<br />

tempted to leave Svaneti. Raised in a machubi — a traditional stone dwelling for<br />

extended families, livestock included — he remembers when Adishi bustled with 60<br />

families, seven churches, and dozens of sacred artifacts. Clan leaders from across<br />

Svaneti rode days on horseback to pray before the village’s leather bound Adishi<br />

Gospels, dating from 897. Disaster always loomed, however, and Kaldani struggled to<br />

stockpile enough for the bitter winters, which even today cut off Adishi from the rest<br />

of Svaneti. Yet nothing prepared him for the deadly avalanches of 1987. He kept his<br />

family safe in the base of their stone tower, but dozens of others died across Svaneti<br />

that winter — and the exodus began.<br />

As more Svan families emigrated to lowland Georgia, Adishi became a ghost town.<br />

At one point only four families remained — Kaldani and his wife, the village librarian,<br />

among them. Kaldani’s sons, who had also abandoned Adishi, persuaded their<br />

parents to join them one winter on the arid plains. They lasted four months before<br />

rushing back to Adishi. “My family has lived here for more than 1,200 years,” he says.<br />

“How could I let my village disappear?”<br />

Going about his chores in his traditional woolen cap, Kaldani embodies the<br />

persistence of Svan culture — and the peril it faces. He is one of the few remaining<br />

fully fluent speakers of Svan. He is also one of the last village mediators, who have<br />

versant.com • 47

Photo © Corinne Thrash

History<br />

long been called upon to adjudicate disputes ranging from petty theft to long-running<br />

blood feuds. The obligation to defend family honor, though slightly tempered<br />

today, led to so many vendettas in early Svan society that scholars believe the stone<br />

towers were built to protect families not just from invaders and avalanches but<br />

also from one another.<br />

In the chaos after the fall of the Soviet Union, blood feuds returned with a vengeance.<br />

“I never rested,” Kaldani says. In some cases, after negotiating a blood price<br />