VERSANT

A travel magazine design project by Hannah Mintek with photography by Corinne Thrash

A travel magazine design project

by Hannah Mintek with photography by Corinne Thrash

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

And now the government is implementing a plan to turn this medieval mountain<br />

zone into a tourist magnet.<br />

Svaneti arguably has seen more change in the past few years than in the past<br />

thousand. It’s not just the vans full of foreign backpackers discovering the region’s<br />

pristine trekking routes. In 2012 the government installed power lines to light up even<br />

the remotest villages. The road that links most villages of Upper Svaneti will soon<br />

be paved all the way to Ushguli. Frenzied construction has transformed the sleepy<br />

regional hub of Mestia into a faux Swiss resort town lined with clapboard chalets<br />

and bookended by hyper modern government buildings and an airport terminal<br />

out of The Jetsons. Meanwhile on the flanks of Mount Tetnuldi, directly across<br />

the river from Jachvliani’s home in Cholashi, one of Georgia’s largest ski resorts is<br />

beginning to take shape.<br />

Perhaps it makes some kind of karmic sense that the mountains and stone towers<br />

that kept outsiders at bay for all these centuries should now be enlisted to lure them<br />

in. But will all this change save the isolated region — or doom it?<br />

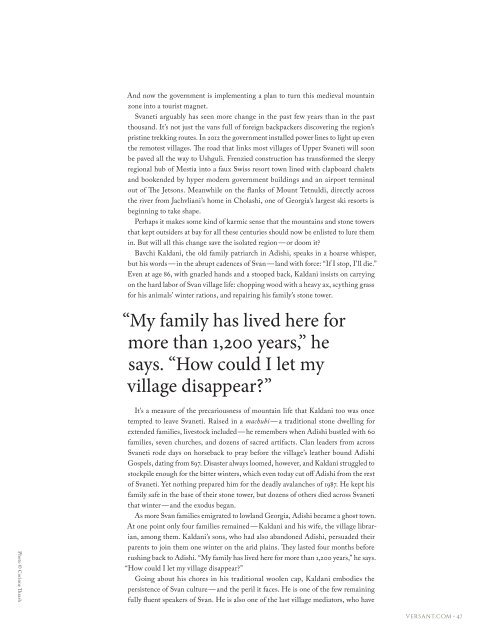

Bavchi Kaldani, the old family patriarch in Adishi, speaks in a hoarse whisper,<br />

but his words — in the abrupt cadences of Svan — land with force: “If I stop, I’ll die.”<br />

Even at age 86, with gnarled hands and a stooped back, Kaldani insists on carrying<br />

on the hard labor of Svan village life: chopping wood with a heavy ax, scything grass<br />

for his animals’ winter rations, and repairing his family’s stone tower.<br />

“My family has lived here for<br />

more than 1,200 years,” he<br />

says. “How could I let my<br />

village disappear?”<br />

Photo © Corinne Thrash<br />

It’s a measure of the precariousness of mountain life that Kaldani too was once<br />

tempted to leave Svaneti. Raised in a machubi — a traditional stone dwelling for<br />

extended families, livestock included — he remembers when Adishi bustled with 60<br />

families, seven churches, and dozens of sacred artifacts. Clan leaders from across<br />

Svaneti rode days on horseback to pray before the village’s leather bound Adishi<br />

Gospels, dating from 897. Disaster always loomed, however, and Kaldani struggled to<br />

stockpile enough for the bitter winters, which even today cut off Adishi from the rest<br />

of Svaneti. Yet nothing prepared him for the deadly avalanches of 1987. He kept his<br />

family safe in the base of their stone tower, but dozens of others died across Svaneti<br />

that winter — and the exodus began.<br />

As more Svan families emigrated to lowland Georgia, Adishi became a ghost town.<br />

At one point only four families remained — Kaldani and his wife, the village librarian,<br />

among them. Kaldani’s sons, who had also abandoned Adishi, persuaded their<br />

parents to join them one winter on the arid plains. They lasted four months before<br />

rushing back to Adishi. “My family has lived here for more than 1,200 years,” he says.<br />

“How could I let my village disappear?”<br />

Going about his chores in his traditional woolen cap, Kaldani embodies the<br />

persistence of Svan culture — and the peril it faces. He is one of the few remaining<br />

fully fluent speakers of Svan. He is also one of the last village mediators, who have<br />

versant.com • 47