Ammaia-Uma-cidade-romana-LR

Ammaia-Uma-cidade-romana-LR

Ammaia-Uma-cidade-romana-LR

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

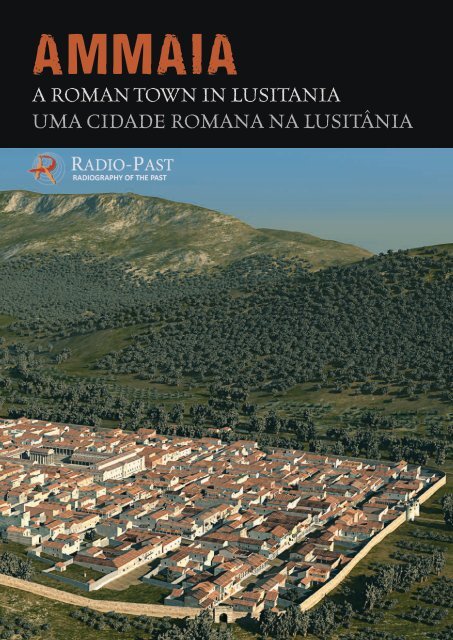

AMMAIAA ROMAN TOWN IN LUSITANIAUMA CIDADE ROMANA NA LUSITÂNIA

Radiography of the past.Exploring “the invisible” inarchaeological sitesMost people think that archaeology is equal to“excavations” and that everything in archaeologyis about “finding”. Nothing could be further fromthe truth: archaeology is all about understandingand in some ways the closest parallel for our jobis with police investigative procedures.In addition to, and sometimes instead of, excavationmany other instruments and approachesare available to researchers for the reconstructionof ancient landscapes and townscapes.Aerial photography, for instance, has been usedby archaeologists since the origin of photographyitself, to “spot” from the air traces of buriedarchaeological features 1 . Equally, survey andsurface artefact collection are applied mainlyto detect the presence of human settlement,mostly in the countryside and in green-fieldareas. Relatively more recently (the first experimentswere performed in the 1940s) differentgeophysical survey techniques have been appliedto detect subsoil archaeological features. A lotof information can also be found in historicaldocuments and archives, in ancient sources andhistorical cartography.This wide range of research methodologies cantoday be defined as “archaeological diagnostics”:as in medicine, we can make a diagnosisassessing the state of the art (medical history),analysing the phenomena and evidence visiblefrom outside (symptomatology), applyinginstrumental diagnostics and finally resolvingto excavation (surgery) only when and wherereally needed, with the least “invasive” approachpossible.In this way, we can collect a lot of informationabout what is still buried under the ground, andin the best cases, once all these data are piecedtogether, we have something comparable to a“radiography” of the subsoil features 2 .The integration of all these techniques hasbrought archaeology in the third millenniumtoward a restraint from excavations, as excavationsare not only costly and time-consuming butRadiografia do passado.A exploração do «invisível»em sítios arqueológicosA maioria das pessoas pensa que arqueologia é sinónimode «escavações» e associa-a ao ato de «descobrir».Nada poderia estar mais longe da verdade: aarqueologia implica compreender e, neste sentido, épossível estabelecer uma comparação muito próximaentre o trabalho dos arqueólogos e os procedimentosda investigação policial.Para além de (e por vezes em vez de) escavações,os investigadores dispõem de muitos outros instrumentose abordagens que lhes permitem reconstituirantigas paisagens rurais e urbanas. A fotografiaaérea, por exemplo, é utilizada pelos arqueólogosdesde a origem da própria fotografia para «detetar»a partir do ar a presença de vestígios arqueológicossoterrados 1 . Da mesma forma, a prospeção e arecolha de artefactos à superfície do terreno aplicam--se para detetar a presença de antigas instalaçõeshumanas, sobretudo em zonas rurais. Mais recentemente(referimo-nos aqui a experiências realizadasa partir da década de 1940), diferentes técnicas deprospeção geofísica têm sido utilizadas para detetarvestígios arqueológicos no subsolo. É ainda possívelencontrar muita informação em documentos earquivos históricos, fontes documentais antigas ena cartografia histórica.Este vasto leque de instrumentos de investigaçãoenquadra-se atualmente no âmbito do chamado «diagnósticoarqueológico»: à semelhança do que sucedena medicina, é possível proceder a um diagnósticoonde se avalia o «estado da arte» (historial clínico),se analisam vestígios visíveis a partir do exterior(sintomatologia), se aplica o diagnóstico instrumentale, finalmente, se opta pela escavação (cirurgia), apenasquando e onde esta for estritamente necessária,recorrendo a uma abordagem o menos «invasiva» possível.Deste modo, podemos recolher muita informaçãosobre o que ainda se encontra soterrado e, uma vezreunidos todos estes dados, proceder, nos casos maisbem-sucedidos, a uma «radiografia» das realidadesocultas no subsolo 2 .A integração de todas estas técnicas conduziu aarqueologia, neste terceiro milénio, a uma contençãonas campanhas de escavação. As escavações3

– most problematically – each monument that isbrought to light requires specialized, costly andoften environmentally unsustainable restorationinterventions.To explore the new possibilities made possible bythe technological and methodological improvementsachieved in the last 20 years, the Europeanfunded project Radio-Past was launched onApril 1 st 2009, with the aim of exploring new possibilitiesfor integration of these “non-invasive”approaches, but also to develop effective waysto visualise these data.It is essential, in fact, that specialists can disseminatethis knowledge to the wider public.Another important objective of the project isto find ways to evaluate and manage this specialcategory of archaeological sites, wherevisitors are confronted with “invisible” ancientsettlements.The “consortium” of partners within the projectis composed of four academic institutions (theuniversities of Évora – Portugal, Ghent – Belgiumand Ljubljana – Slovenia, and the British Schoolat Rome – UK), with three SMEs (Eastern Atlassão caras, morosas e, sobretudo, cada monumentotrazido à luz do dia requer outras intervenções especializadas,de conservação e restauro, dispendiosase muitas vezes pouco sustentáveis do ponto de vistaambiental.Com vista a explorar as novas potencialidades suscitadaspelos desenvolvimentos tecnológicos emetodológicos dos últimos vinte anos, o projetoRadio‐Past, financiado pela União Europeia, foi lançadoa 1 de Abril de 2009 com o objetivo não só deinvestigar novas possibilidades para a integraçãodestas abordagens «não-invasivas», mas também dedesenvolver modos eficazes de visualizar os dadosobtidos.Com efeito, é essencial que os investigadores possamdivulgar este conhecimento junto de um públicomais alargado. Um outro importante objetivo desteprojeto é encontrar modos de valorizar e gerir estacategoria especial de sítios arqueológicos, ondeos visitantes são confrontados com povoamentosantigos «invisíveis».O «consórcio» de parceiros reunidos neste projetoé composto por quatro instituições académicas (asuniversidades de Évora, em Portugal; de Ghent,14

2– Germany, 7reasons – Austria and Past2Present– The Netherlands).The partners have selected several “test sites”where they have gathered to cooperate in fieldwork,experimentation and training activities.The cooperative process of interpretation andthe discussion of the scientific aspects amongspecialists of different fields have brought spectacularresults.Here, we will guide you through the “underworld”of <strong>Ammaia</strong>, trying to make you experience the“invisible” reality of a Roman town in Lusitania.Enjoy the ride!C.C.na Bélgica; de Liubliana, na Eslovénia; e a BritishSchool at Rome, do Reino Unido) e três PME (a alemãEastern Atlas, a austríaca 7reasons e a holandesaPast2Present).Os parceiros procederam à seleção de diversos «sítiosde ensaio», onde se reuniram para colaborar no trabalhode campo e em atividades de experimentaçãoe formação. O processo de cooperação entre especialistasde diferentes domínios, na interpretação ediscussão dos aspetos científicos, trouxe resultadosextraordinários.Aqui, guiá-lo-emos através do «submundo» de<strong>Ammaia</strong> com o intuito de lhe proporcionar a vivênciada realidade «invisível» de uma <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong>na Lusitânia.Desfrute desta aventura!C.C.5

<strong>Ammaia</strong> in the context ofLusitaniaWhile many archaeological discoveries in the widerregion of <strong>Ammaia</strong>, and especially in the Tagusbasin, prove human occupation during the StoneAge, the area received important new impulsesduring the later Bronze Age. Near the end of thesecond millennium BC new Indo-European populationsentered the Iberian Peninsula. Of these,the Lusitani tribes settled in the Beira region andparts of Spanish Extremadura, while the Conii tribessettled in the Alentejo, the southern part of theSpanish Extremadura and the Algarve. The area,where <strong>Ammaia</strong> would later be founded, was situatedin the contact zone of both populations. Thesubsequent arrival in several waves, around 500 and250 BC, of Celtic populations, baring iron weaponsand tools, brought new blood to the region.This coincides with an increasing Mediterraneaninfluence, and contact with the more developedcultures of the Tartessian, Phoenician, Greek andCarthaginian colonists that had settled along thesouthern Iberian coasts. This period also marks achange in the settlement pattern of the region.Existing settlements of the indigenous Iron agepopulations are gradually abandoned and replacedby larger, fortified towns as a response to the growingsocio-economic, politic and military instability,such as that caused by the military campaignsof the Romans in the Iberian Peninsula after theSecond Punic War (218 – 201 BC).After the defeat of the Carthaginians, the Romanpresence in the coastal areas of the eastern andsouthern part of the Iberian Peninsula was definitivelyestablished. During the next two centuries,the Romans gradually annexed the entire Peninsula.For the <strong>Ammaia</strong> region, this must have takenplace between 178 BC, when the first Roman armyunder command of L. Postumius Albinus arrivedin the region, and 138 BC, when Decimus JuniusBrutus conquered Olisipo (Lisbon) and Moron (nearSantarém) and consolidated the Roman presencesouth of the Tagus River. The definitive integrationof this area south of the Tagus River is dated to72 BC, after the Sertorian rebellion.During the first decades of Roman military control,existing indigenous settlements continued to be<strong>Ammaia</strong> no contexto daLusitaniaEmbora muitos dados arqueológicos da região envolventede <strong>Ammaia</strong> e, em particular, da bacia do Tejo,atestem a ocupação humana durante a Pré-História, aárea conheceu importantes transformações durante oBronze Final. Em fins do segundo milénio a.C., novaspopulações indo-europeias chegaram à PenínsulaIbérica, entre as quais se identificam os Lusitanos, quese estabeleceram na região da Beira e na Extremaduraespanhola, e os Cónios, que ocuparam o Alentejo,as áreas meridionais da Extremadura espanhola eo Algarve. A área do futuro território de <strong>Ammaia</strong>situava-se na zona de contacto entre ambas as populações.Entre 500 a 250 a.C., a chegada de distintasvagas de populações célticas, portadoras de armas eferramentas de ferro, trouxe novo sangue à região.Este período coincide com uma crescente influênciado Mediterrâneo e o contacto com as culturas maisdesenvolvidas de tartéssios e colonos fenícios, gregose cartagineses, estabelecidos ao longo da costa sulda Península Ibérica. Este período regista tambémuma mudança no padrão de povoamento da região.Os anteriores povoados indígenas da Idade do Ferroforam progressivamente abandonados e substituídospor povoados fortificados de maiores dimensões emresposta à crescente instabilidade socioeconómica,política e militar, designadamente as campanhas militares<strong>romana</strong>s na Península Ibérica depois da SegundaGuerra Púnica (218-201 a.C.).Após a derrota dos Cartagineses, a presença <strong>romana</strong>nas regiões costeiras a leste e sul da Península Ibéricaestabeleceu-se definitivamente. Ao longo dos doisséculos seguintes, os Romanos apoderaram-se progressivamentede toda a Península. No que respeitaà região de <strong>Ammaia</strong>, esta ocupação terá tido lugarentre 178 a.C. – quando o primeiro exército romano,sob o comando de Lúcio Póstumo Albino, chegou àregião –, e 138 a.C., quando o general Décimo JúnioBruto conquistou Olisipo (Lisboa) e Moron (pertode Santarém), consolidando a presença <strong>romana</strong> asul do rio Tejo. A integração definitiva desta regiãoconsumou-se em 72 a.C., depois da guerra Sertoriana.Durante as primeiras décadas de controlo militarromano, os povoados indígenas continuaram ocupados,sendo a presença <strong>romana</strong> bastante limitada. Estasituação alterou-se sensivelmente na primeira metade7

inhabited and actual Roman presence was ratherlimited. This changed when, around the mid-firstcentury BC, the first Roman immigrants arrived tosettle here permanently. This settlement led to afull territorial and political reorganization underAugustus, consolidated by the foundation of properRoman towns from 27 BC onwards. The provinceof Lusitania was thus created, covering an areathat takes in most of present-day Portugal (exceptthe North) and a part of neighbouring SpanishExtremadura. As capital the new colonial city ofEmerita Augusta (Mérida) was chosen 4 whilemany other important towns were developed, suchas the central Lusitanian towns of Pax Iulia (Beja),Olisippo (Lisbon), Norba Caesarina (Cáceres) andEbora Liberalitas Iulia (Évora) 3 .Probably around the beginning of our era the Romanadministration decided to found also a new midsizedtown in the area of the Serra de São Mamede,near the new road system of central Lusitania thatconnected the capital Emerita Augusta with theAtlantic coast 5 . The town of <strong>Ammaia</strong> was born,probably settled by immigrants as well as membersof the indigenous populations of this region. Likeother towns in the province, <strong>Ammaia</strong> undoubtedlyfunctioned as an urban and political-administrativecentre from where the surrounding lands could begoverned efficiently.The urban settlement of <strong>Ammaia</strong> thus became partof a major change in the Iberian Peninsula thatcame with the spread of new Roman self-governingcommunities that created new foci of power inthe region. This new framework was facilitated bythe gradual ceding of self-governing status (municipium)to all free communities in the provinceof Lusitania between the reign of Augustus andthe late first century AD. These new arrangementsprecipitated also major changes in the pattern ofrural settlement across the region, reaching significantdensities by the Flavian period (late firstcentury AD).The Roman town of <strong>Ammaia</strong> was the geographiccentre of a territory of almost 4000 km 2 , situatedsouth of the Tagus River and extending on bothsides of the present-day Portuguese-Spanish border.It comprised other smaller population centres inthe territory, such as Abelterium (Alter do Chão),and Vicus Camalocensis (near Crato), which mainlydo século I a.C., época em que os primeiros imigrantesitálicos chegaram para aqui se instalarem. No principadode Augusto, regista-se uma ampla reorganizaçãoterritorial e política, consolidada pela fundação deverdadeiras <strong>cidade</strong>s <strong>romana</strong>s a partir do ano 27 a.C. Foiassim criada a província da Lusitania, abarcando umaárea geográfica que compreendia boa parte do atualterritório português (excluindo o Norte) e parte davizinha Extremadura espanhola. A capital da provínciaestabeleceu-se na nova colonia de Emerita Augusta(atual Mérida) 4 e desenvolveram-se outros centrosimportantes, como as <strong>cidade</strong>s lusitanas de Pax Iulia(Beja), Olisippo (Lisboa), Norba Caesarina (Cáceres)e Ebora Liberalitas Iulia (Évora) 3 .Provavelmente por volta dos inícios da nossa Era, aadministração <strong>romana</strong> decidiu fundar uma nova <strong>cidade</strong>de dimensão média na área da Serra de São Mamede,junto à nova rede viária da Lusitania central, queestabelecia a ligação entre a capital Emerita Augustae a costa atlântica 5 . Assim nasceu a <strong>cidade</strong> de<strong>Ammaia</strong>, possivelmente estabelecida por imigrantese pelas populações indígenas. À semelhança de outras<strong>cidade</strong>s da província, sem dúvida que <strong>Ammaia</strong> funcionavacomo centro urbano político-administrativo quegeria eficazmente o território circundante.O aglomerado urbano de <strong>Ammaia</strong> tornou-se, portanto,parte integrante da grande transformação operadana Península Ibérica pelos romanos: comunidadesautónomas fundadas de raiz que passaram a constituiros novos centros de poder na região. Este novoenquadramento foi potenciado pela concessão gradualdo estatuto municipal (municipum) a todas ascomunidades livres da província da Lusitania, entreo principado de Augusto e os finais do século I d.C.Esta nova configuração implicou também importantesalterações no padrão do povoamento rural em toda aregião, atingindo densidades significativas no períodoflaviano (finais do século I d.C.).A <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong> de <strong>Ammaia</strong> era o lugar central de umterritório com quase 4.000 km 2 , a sul do rio Tejo, quese estendia a ambos os lados da atual fronteira entrePortugal e Espanha. Este território abrangia outrosnúcleos populacionais menores, como Abelterium(Alter do Chão) e Vicus Camalocensis (na zona doCrato), que entretanto haviam emergido nos principaisentroncamentos da rede viária, bem como umaextensa mancha de assentamentos rurais responsáveispela exploração do território. Alguns destes núcleos8

4 5emerged on the main crossroads of the road network.Furthermore, an extensive network of rural farms wasresponsible for the exploitation of the landscape.Some were relatively small and served to supply thetown with the necessary goods for its daily subsistence,such as food, building stone, wood and metal.Others, located further away from the urban centre,developed into large villa estates, such as at Torrede Palma. Most of these large villa estates producedgoods, such as olive oil, wine and horses, partly forexport to external markets. Architecturally they wereexponents of the Roman Mediterranean way of life,richly decorated with marble and mosaics and oftenincorporating bathing facilities in addition to residentialand industrial or artisanal functions. Besidescrop cultivation and livestock farming (cattle, sheep,pigs), another important economic activity in thestudy area was the mining of mineral resources,mainly iron and lead. Remains of these extractiveactivities are plentiful in the territory of <strong>Ammaia</strong>.More valuable minerals such as gold (near the Tagus)and rock crystal, for the manufacture of glass andjewellery, were mined as well. The importance ofrock crystal is illustrated by two references in theNaturalis Historia by Pliny the Elder, to the presenceof the mineral in the hills around <strong>Ammaia</strong>.This system of the well-organized town and marketcentre of <strong>Ammaia</strong> and its rural and industrialhinterland flourished deep into the fourth century.From the fifth century onwards the decline andfinal collapse of the Roman economic system andthe invasion of Germanic peoples (Sueves, Vandals,Alans) resulted in a gradual abandonment of theurban centres of Lusitania. While some, like Méridaknew continuity under the subsequent Visigothicrule, that from the year 585 incorporated the entirePeninsula, many others like <strong>Ammaia</strong> declined graduallyand were sometimes completely abandoned.F.V.eram relativamente modestos, servindo para abastecera <strong>cidade</strong> dos bens necessários à subsistência diária,como alimentos, pedra para construção, madeira emetal. Outros, mais distantes do centro urbano, transformaram-seem grandes propriedades rurais (villae),como é o caso de Torre de Palma. Na sua grande maioria,estas villae dedicavam-se à produção de azeite,vinho ou à criação de cavalos, em parte destinados àexportação. Em termos arquitetónicos, eram expoentesdo modo de vida mediterrâneo romano, ricamenteornamentadas com mármore e mosaicos e, em geral,incluíam instalações para banhos, a par da área residenciale das estruturas ligadas às funções laborais ede manufatura. Para além da agricultura e da criaçãode gado (bovino, ovino e suíno), a exploração dosrecursos minerais, principalmente ferro e chumbo,constituía outra atividade económica importante,sendo abundantes os vestígios da extração mineirano território de <strong>Ammaia</strong>. Também os minerais maisvaliosos foram explorados, como o ouro (perto doTejo) e o cristal de rocha, para o fabrico de vidro ejoalharia. A importância do cristal de rocha é ilustradapor duas referências à presença deste mineral na serrade São Mamede, incluídas na Naturalis Historia dePlínio o Velho.O modelo estabelecido em <strong>Ammaia</strong>, uma <strong>cidade</strong> bemorganizada dotada de mercado e de um territóriorural e industrial, floresceu ao longo do século IV.A partir do século V, o declínio e o derradeiro colapsodo sistema económico romano, bem como a invasãode povos germânicos (Suevos, Vândalos, Alanos),ditaram o progressivo abandono dos centros urbanosda Lusitania. Enquanto algumas <strong>cidade</strong>s, comoMérida, se mantiveram sob o subsequente domíniovisigodo, que a partir do ano 585 se apoderou de todaa Península Ibérica, muitas outras, à semelhança de<strong>Ammaia</strong>, entraram gradualmente em declínio e foram,em alguns casos, completamente abandonadas.F.V.9

The discovery of <strong>Ammaia</strong>and its history according toancient sourcesThe site of the former Roman town of <strong>Ammaia</strong>is located in the municipality of Marvão, in thedistrict of Portalegre in the Alto Alentejo. Thearchaeological evidence of this now-abandonedtown-site lies on the hillside immediately southof the small “street-village” of São Salvador deAramenha, in the valley of the Rio Sever.The standing ruins still visible above-ground hadalready attracted the attention of Portugueseand Spanish historians in the sixteenth century,when the monuments of the ancient towns weredespoiled to procure readily available buildingstones. In 1710 the then-still-standing southerngate of <strong>Ammaia</strong> was transferred to the neighbouringvillage of Castelo de Vide, where it stayed inuse until 1891 6 . During the later nineteenthcentury and the early twentieth century, the firstexcavations revealed some of the town’s necropoleisand many intact Roman burial gifts foundtheir way into private and public collections.Until that period, archaeologists and historiansbelieved that the ruins near São Salvadorda Aramenha belonged to the Roman town ofMedobriga and that the remains of <strong>Ammaia</strong> werelocated underneath the modern town of Portalegre,more than 10km to the south. It was not until1935, when Leite de Vasconcelos published a paperon the discovery of an honorific inscription dedicatedto the Emperor Claudius (IRCP 615), thatthe Roman remains near São Salvador da Aramenhawere identified as those of <strong>Ammaia</strong>. Shortly after,the site was declared a National Monument (1949)and in 1994 the central area of the Roman townreceived the protected status of archaeologicalpark. Since then, archaeological fieldwork andexcavations have been taking place in <strong>Ammaia</strong>almost continuously, the operations organised bythe Fundação Cidade de <strong>Ammaia</strong>, in partnershipwith the Portuguese universities of Coimbra andÉvora (the latter, still “scientific” coordinator of thesite), in collaboration with several foreign universities,such as Ghent (Belgium), Louisville (USA),Cassino (Italy) and Dublin (Ireland).A descoberta de <strong>Ammaia</strong>e a sua história segundofontes antigasO sítio arqueológico da antiga <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong> de<strong>Ammaia</strong> encontra-se no concelho de Marvão, distritode Portalegre, na região do Alto Alentejo. Os vestígiosarqueológicos desta <strong>cidade</strong>, hoje abandonada,situam-se na encosta a sul da pequena vila de SãoSalvador da Aramenha, no vale do rio Sever.A parte ainda visível das suas ruínas chamou a atençãode eruditos portugueses e espanhóis logo noséculo XVI, quando as <strong>cidade</strong>s antigas foram saqueadaspara obter pedra de construção. Em 1710, oentão ainda conservado arco da Porta Sul de <strong>Ammaia</strong>foi transferido para a vila vizinha de Castelo de Vide,onde permaneceu em uso até 1891 6 . Entre finsdo século XIX e o início do século XX, as primeirasescavações revelaram algumas das necrópoles da<strong>cidade</strong> e muitas das ainda intactas oferendas funerárias<strong>romana</strong>s vieram a integrar coleções públicase privadas.Até essa data, arqueólogos e historiadores acreditavamque as ruínas próximas de São Salvador daAramenha pertenciam à <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong> de Medobriga,e que os vestígios de <strong>Ammaia</strong> se encontravam soba moderna <strong>cidade</strong> de Portalegre, mais de dez quilómetrosa sul. Somente em 1935, quando Leite deVasconcelos publicou um artigo sobre a descobertade uma inscrição honorífica dedicada ao ImperadorCláudio (IRCP 615), foram as ruínas <strong>romana</strong>s próximasde São Salvador da Aramenha identificadas comoa antiga <strong>cidade</strong> de <strong>Ammaia</strong>. Pouco depois, o local foiclassificado como Monumento Nacional (1949) e, em1994, a área central da <strong>cidade</strong> recebeu a proteçãolegal que hoje detém. Desde então, os trabalhosarqueológicos de campo e as escavações têm decorridoem <strong>Ammaia</strong>, de um modo contínuo, organizadospela Fundação Cidade de <strong>Ammaia</strong> em parceria comas universidades portuguesas de Coimbra e Évora(assumindo esta última a coordenação científica dosítio) e com várias universidades estrangeiras, taiscomo Ghent (Bélgica), Louisville (EUA), Cassino(Itália) e Dublin (Irlanda).As primeiras escavações concentraram-se essencialmentenas áreas onde as ruínas visíveis indicavamclaramente a presença de vestígios romanos 7 .11

7Early excavations have focused essentially onareas where visible ruins indicated the presenceof subsurface Roman remains 7 . These areasincluded parts of the city wall and the southerngate (Porta Sul) with associated monumentalsquare and residential buildings, parts of a publicEssas áreas incluíam parte da muralha da <strong>cidade</strong> ea entrada meridional (Porta Sul), com a sua praçapública monumental e edifícios residenciais, parte deum complexo de banhos públicos (Termae) e partedo complexo do fórum, onde o núcleo do pódio dotemplo, construído em opus caementicium (o típico12

athhouse (Termas), and parts of the forum complexwhere the caementicium (the typical Romanconcrete) core of the temple podium was stillpresent above ground. In addition, a residentialarea underneath an abandoned farmhouse(Quinta do Deão) that now hosts the museum,betão romano), ainda era visível acima do solo. Alémdisso, procedeu-se à escavação integral de uma árearesidencial situada sob um edifício abandonado daQuinta do Deão, que agora alberga o museu monográfico,e de uma pequena área suburbana situadaentre a <strong>cidade</strong> e o rio Sever. Em 2001, a par das escavações,tiveram início outros tipos de investigação,nomeadamente um extenso programa de pesquisageoarqueológica, levando à descoberta dos aquedutosromanos 8 , à delineação hipotética do circuitoda muralha 18, à compreensão da relação entre a<strong>cidade</strong> e a paisagem circundante e à identificaçãode alguns recursos básicos da economia urbana, taiscomo as pedras usadas nas construções, os mineraise os metais.<strong>Uma</strong> nova etapa da investigação teve início em 2009,com o lançamento do projeto Radio-Past, que selecionou<strong>Ammaia</strong>, como um dos principais laboratóriosabertos para testar a integração de abordagens não--destrutivas. Um levantamento «integral» da <strong>cidade</strong>e dos seus subúrbios permitiu a reconstituição dodesenho urbano, com a delimitação da sua rede deruas e a definição das características planimétricas dosseus principais monumentos e áreas habitacionais 18.Enquanto parte integrante da nova agenda de investigação,o estudo das diversas categorias de artefactos(cerâmicas finas e comuns, ânforas, moedas,vidros, etc.) e a reavaliação dos registos das antigasescavações conduziram a um novo entendimentoda história de <strong>Ammaia</strong> distinto do anteriormenteconhecido. <strong>Ammaia</strong> não conheceu grande projeçãona literatura antiga: praticamente não é citada, comexceção de uma indicação das suas coordenadasastronómicas em Ptolemeu (II, 5, 8) e de uma brevemenção da serrania próxima (a Ammaeensia Iuga)na enciclopédica obra de Plínio o Velho, como localonde foi encontrado um cristal de rocha de dimensãoexcecional (N.H. XXXVII, 24; XXXVII, 127). Mas ofamoso erudito não refere <strong>Ammaia</strong> na sua lista decivitates da Lusitânia, contida no livro IV, 117-118da sua Naturalis Historia.A análise do registo arqueológico até agora produzidopermite estabelecer que a fundação de <strong>Ammaia</strong> sedeu durante o principado de Augusto, possivelmentenos últimos anos do século primeiro a.C., ou logono início da nossa Era. A sua fundação resulta claramentede um projeto bem definido, destinado a estabelecerum ponto de povoamento que funcionasse13

and a small suburban area between the town andthe River Sever were fully excavated. Starting as2001, other types of investigation have paralleledthe traditional excavations, and an extensiveprogram of geo-archaeological research hasstarted, leading to the discovery of the Romanaqueducts 8 , the hypothetical delineation ofthe wall circuit 18, the comprehension of therelationship between the town and countryside,and to the identification of primary resources forthe economy of the town, such as stones, mineralsand metals.As we saw, in 2009, with the launch of the projectRadio-Past which selected <strong>Ammaia</strong> as one ofthe main open-labs for testing the integrationof non-destructive approaches, a new season ofresearch has started and a “total” survey of thetown and its suburbium has allowed the reconstructionof the town layout, with the delineationof the street-grid and the definition ofthe characteristics of its main monuments andhousing sectors 18.The study of several categories of finds (fine andcoarse wares, amphorae, coins, glasses, etc.)and the re-processing of old excavation records,integrated within the new research agenda, havebrought to a new understanding of the historyof <strong>Ammaia</strong>, which is otherwise not very detailedin the ancient sources. On the contrary, <strong>Ammaia</strong>never reached the headlines in ancient literature:it is never cited in ancient sources, with theexception of an indication of its astronomicalcoordinates in Ptolemy (II, 5, 8) and a briefmention in Pliny the Elder’s encyclopaedia of themountain range (the Ammaeensia Iuga) where apiece of rock crystal of outstanding dimensionwas found (N.H. XXXVII, 24; XXXVII, 127). Butthe famous scholar fails to name <strong>Ammaia</strong> in thelist of civitates of Lusitania contained in the bookIV, 117-118 of the Naturalis Historia.The above mentioned analysis of the archaeologicalrecord collected so far allows us to proposefor <strong>Ammaia</strong> a foundation during the Principate ofAugustus, possibly in the last years of the firstcentury BC or the very beginning of the new Era.The foundation is clearly framed in a well-definedproject, intended to create a settlement thatcould serve as “central place” for the exploitationcomo «lugar central» na exploração da terra e dosseus recursos naturais, e como ponto de confluênciada rede de estradas que ligavam o interior e o litoralda Lusitânia, a qual terá certamente orientado odesenho da <strong>cidade</strong>.Nesta fase, não é possível determinar o estatutojurídico da povoação. <strong>Uma</strong> inscrição de 44/45 d.C.atribuiu a <strong>Ammaia</strong> a designação de «civitas» (IRCP,615: civitas Ammaiensis), e uma outra de 166refere-a como «municipium» (IRCP, 616: municipesAmmaienses: 9 ), o que permite aferir comsegurança que a <strong>cidade</strong> terá alcançado primeiro adignidade de civitas e posteriormente o estatutomunicipal. A elevação ao estatuto de municipiumlatino teria assim ocorrido no espaço de tempo compreendidoentre a segunda metade do século I d.C.e a primeira metade do II.<strong>Ammaia</strong> é tradicionalmente integrada no ConventusPacensis, uma das três circunscrições administrativasem que se dividia a Lusitânia, segundo Plínio, sendoas restantes o Conventus Emeritensis e o ConventusScallabitanus 3 . No entanto, têm sido avançadaspropostas, ainda provisórias, para a redefinição defronteiras e a consequente inclusão de <strong>Ammaia</strong> noConventus Emeritensis.Os estudos de artefactos arqueológicos parecemdemonstrar que a <strong>cidade</strong> floresceu durante os séculosII e III d.C. No decorrer do IV, foram renovadosalguns monumentos e, ainda que alguns setores nãoaparentem ter sido muito «dinâmicos», o período814

of the land and its natural resources and as junctionalong the road-network connecting innerand coastal Lusitania, which helped to designthe layout of the town in detail.At this stage we cannot establish the originalpolitical status of this settlement. However, aninscription of 44/45 AD qualifies <strong>Ammaia</strong> as a“civitas” (IRCP, 615: civitas Ammaiensis), andone of 166 AD defines it “municipium” (IRCP,616: municipes Ammaienses: 9 ). Therefore weare sure that the town achieved first the “civitas”status and later the municipal one. The elevationto the status of Latin municipium would have,therefore, happened during the period betweenthe second half of the first and the first half ofthe second century AD.<strong>Ammaia</strong> is traditionally included in the ConventusPacensis, one of the three administrative compartmentsin which Lusitania is divided by Pliny,the other being the Conventus Emeritensis andthe Conventus Scallabitanus 3 , but tentativeproposals for the re-definitions of the bordersand a re-allocation of <strong>Ammaia</strong> in the ConventusEmeritensis have been advanced.The study of finds seems to prove that the townflourished during the second and third centuries.In the course of the fourth century, fewmonuments were renovated and even if some sectorsdo not appear to be very “lively”, the LateImperial phase is still very perceptible. After thefifth century, the city seems to have graduallyfallen into abandonment, as the inhabited areasgradually shrank: recent excavations have shownthat some parts were already covered by floodsand slope deposits during the Late Antiqueperiod, and that some constructions, presumablyprivate buildings, invaded the public spaces.Ancient sources inform us that when the Arabsconquered the region in the last quarter of theninth century, the Muladi chieftain Ibn Marwânsettled on the nearby and strategically wellsituatedstronghold which was named Marvãoafter him, and boasted that he was Lord of the“Fortaleza de Amaia”. At that time, the Romansite was presumably totally abandoned.C.C.tardio do Império Romano é ainda bastante percetível.Depois do século V, a <strong>cidade</strong> parece ter caídogradualmente no abandono à medida que as áreashabitadas diminuíam progressivamente. Escavaçõesrecentes têm revelado que algumas zonas da <strong>cidade</strong>haviam já sido cobertas por sedimentos e depósitosde vertente durante a Antiguidade Tardia, e que algumasconstruções, provavelmente edifícios privados,tinham invadido os anteriores espaços públicos.No último quartel do século IX, quando os árabesconquistaram a região, a literatura antiga relata ainstalação do chefe muladi Ibn Maruán na vizinhae estratégica fortaleza de Marvão, que a si deve onome, vangloriando-se de ser o Senhor da «Fortalezade Amaia». Presume-se que à época a <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong>se encontrasse já totalmente abandonada.C.C.915

Data collection. Strategiesand approachesOne of the most important elements of theRadio-Past project was to test the viability ofnon-intrusive survey methodologies throughtheir application, within a control project, to asingle complex site. The Roman town of <strong>Ammaia</strong>fulfilled this criterion perfectly and enabled arange of prospection and survey techniques to beemployed, tested, and refined. From the outset,our project aimed to explore the potential ofa fully integrated strategy and to utilise thesetechniques in a considered and complementarymanner. To this end, geomorphological and topographicalsurvey preceded more intensive geophysicalsurvey and ground-truthing during thecourse of three years of fieldwork campaigns.Recolha de dados.Estratégias e abordagensUm dos aspetos mais importantes do projeto Radio-Past era a possibilidade de testar a viabilidade da aplicaçãode metodologias de prospeção não-invasivas,no âmbito de um projeto-piloto, a um único sítioarqueológico complexo. A <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong> de <strong>Ammaia</strong>preenchia estes requisitos na perfeição e permitia quevárias técnicas de prospeção e levantamento fossemempregues, testadas e aperfeiçoadas. Desde o início,o nosso projeto teve como objetivo explorar opotencial de uma estratégia plenamente integrada eutilizar estas técnicas de forma ponderada e complementar.Para este fim, o levantamento geomorfológicoe topográfico precedeu uma prospeção geofísica maisintensiva e algumas sondagens no decurso de três anosde trabalhos de campo.16

10GeomorphologyGeo-archaeological research has been a centralpart of the research strategy applied to the site of<strong>Ammaia</strong> since the inception of the project in 2001as it was deemed essential to fully understand thegeomorphology and geology, of both the site itselfand its wider context, before further work could beundertaken. This approach would thereby enabletraditional field observations, intensive archaeologicalsurvey and excavation results to be coherentlyintegrated with aerial photographic analysis,micro-topographic studies and a thorough understandingof the nature of the subsoil and site formationprocesses. This strand of fieldwork activityhad its origins prior to the beginning of the Radio-Past project. It was undertaken collaboratively andin direct cooperation between different disciplines,with the aim of applying to the study of the siteGeomorfologiaDesde o lançamento do projeto, em 2001, a investigaçãogeoarqueológica tem constituído um aspeto centralda estratégia de investigação no sítio de <strong>Ammaia</strong>, jáque se considerou essencial compreender a geomorfologiae a geologia tanto do próprio sítio, como do seuentorno, antes de prosseguir com mais aprofundadostrabalhos. Este tipo de abordagem permitiria que astradicionais observações de campo, o levantamentoarqueológico intensivo e os resultados das escavaçõesfossem integrados de modo coerente na análise defotografia aérea, nos estudos de microtopografia e nosólido conhecimento da natureza do subsolo e dos processosde formação do sítio. Esta vertente do trabalhode campo teve a sua origem antes do início do projetoRadio-Past, tendo sido levada a cabo em estreita colaboraçãoentre as diferentes disciplinas com o propósitode aplicar ao estudo do sítio uma abordagem coerente,17

a coherent approach, which fully integrated geologicaland geomorphological observations withinhistorically derived research-questions.Field survey campaigns, undertaken between2001 and 2004 by teams from the Universitiesof Ghent (Belgium) and Cassino (Italy), aimedat defining the extent of the archaeologicallysignificant area. This involved tracing the wallcircuit of the roman town 18 and understandingthe geomorphological essentials, such as sitelocation-preference and erosion history. A secondphase of geo-archaeological research undertakenbetween 2004–2010 concentrated on the exploitationof natural resources such as water, minerals,and stone, within the wider territory of theRoman town.Finally, during the final fieldwork campaign of2011 the focus of activity returned to the site ofthe ancient town itself. As a result of the intensivegeophysical prospection undertaken in thepreceding years, a need was identified to furtherinvestigate the nature of the soil and its erosionhistory in relation to evidence from geophysicalsurvey of near-surface archaeological structures,such as walls, streets and floors.18articulando plenamente as observações geológicas egeomorfológicas com as questões de índole históricacolocadas pela investigação.As campanhas de prospeção do terreno, realizadasentre 2001 e 2004 por equipas da Universidade deGhent (Bélgica) e Cassino (Itália), pretenderam delimitara extensão da área de interesse arqueológico.Para o efeito, foi necessário identificar o circuito dasmuralhas da <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong> 18 e compreender oselementos geomorfológicos essenciais, tais como ascircunstâncias que determinaram a sua implantaçãoe o historial de erosão. A segunda fase da investigaçãogeoarqueológica, realizada entre 2004 e 2010,concentrou-se na análise da exploração dos recursosnaturais existentes no território da <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong>,tais como a água, minerais e pedra.Finalmente, durante a última campanha de 2011, aatenção centrou-se de novo no sítio da antiga <strong>cidade</strong>.Em resultado do levantamento geofísico extensivolevado a cabo nos anos anteriores, sentiu-se a necessidadede continuar a investigar a natureza do solo e ohistorial de erosão em correlação com os dados da prospeçãogeofísica de estruturas arqueológicas de escassaprofundidade, tais como paredes, ruas e pavimentos.Deteção RemotaRemote SensingNos últimos anos, na sequência dos significativosIn recent years, as a result of significant technologicalprogresses in Light Detection and Ranging deteção e alcance de luz (LiDAR – Light Detection andprogressos tecnológicos registados nos sistemas de(LiDAR), large-scale three-dimensional (3D) data Ranging), têm sido progressivamente disponibilizadosdados tridimensionais (3D) de larga escala parahas become increasingly widely available for thestudy of archaeological landscapes and features. o estudo de elementos e paisagens arqueológicas.LiDAR provides coordinate data through a GPSdevice and inertial sensors in the aeroplane usedto conduct the survey, alongside elevation informationgenerated by laser scanner, which togetherprovide an effective way of acquiring accurate 3Dinformation of natural and/or anthropogenic landscapefeatures. The main advantages of LiDAR overconventional surveying methods lie in the highprecision of the data, relatively short time neededto scan large areas and low price per unit of area,especially if compared with traditional, manual,methods of data acquisition (GPS or total stationsurveys). LiDAR scans provide a vast amountof data points that result in information rich,complex point clouds. However, even with a lowunit-price per square kilometre for commercially 11

12available LiDAR data, it still requires a major outlayin terms of logistics and financial input to producethe high-density datasets necessary for thestudy of intra-urban landscapes. This is especiallytrue for comparatively small-scale surveys suchas that planned for the townscape of the projecttest-site of <strong>Ammaia</strong> where equipment, logistics,and running-costs become a larger proportion ofthe overall budget.As part of the project, the Institute for Systemsand Robotics at the Instituto Superior Técnico(Lisbon, Portugal) aimed to develop a small autonomousrobotic helicopter to perform high accuracythree-dimensional surveys of extant structures andthe topography of the site, with the objective ofproducing accurate data sets with the requiredspatial resolution 11. Recent advances in sensortechnology and ever-increasing computationalcapacity are steadily affording Unmanned AerialVehicles (UAVs) higher degrees of robustness andreliability when operating in uncertain and possiblyremote environments. Our project aimed totest the utility of such an approach for the purposeof recovering data relating to specificallyarchaeological questions rather than relying onoften unsatisfactory or unavailable, repurposed,commercially available data.Some low altitude aerial photography wasapplied. Test with an helium balloon over theO sistema LiDAR faculta coordenadas através de umrecetor GPS e de sensores inerciais instalados no aviãousado na prospeção, a par de informação altimétricagerada por leitura de scanner a laser. No seu conjunto,constitui um modo eficaz de aquisição de informaçãoexata em 3D sobre as características naturais e/ouantropogénicas da paisagem. As principais vantagensdeste sistema face a métodos de prospeção mais convencionaissão a elevada precisão dos dados recolhidos,o curto período de tempo necessário para prospetaráreas bastantes extensas e o baixo custo por unidadede área, sobretudo se comparado com métodos manuaistradicionais de aquisição de dados (via GPS ou EstaçãoTotal). As leituras LiDAR fornecem uma enorme quantidadede dados que resultam em nuvens de pontos cominformação rica e complexa. Todavia, apesar do baixocusto unitário por km 2 dos dados LiDAR disponíveisno mercado, este sistema ainda requer um enormeesforço em termos de logística e recursos financeirospara produzir os conjuntos de dados de alta densidadenecessários ao estudo das paisagens intraurbanas. Esteaspeto é especialmente pertinente no caso de levantamentosde escala comparativamente pequena, tal comoo previsto para a paisagem urbana do sítio de teste em<strong>Ammaia</strong>, onde o equipamento, a logística e as despesasdecorrentes da sua aplicação absorveram a maior fatiado orçamento global do projeto.No âmbito deste projeto, o Instituto de Sistemase Robótica do Instituto Superior Técnico (Lisboa,Portugal) procurou desenvolver um pequeno helicópterotelecomandado autónomo para executar levantamentostridimensionais de alta precisão em estruturasexistentes e na topografia do sítio. O objetivo seriaproduzir conjuntos de dados precisos com alta resoluçãoespacial de imagem 11. Os recentes avançosna tecnologia de sensores e a progressiva capa<strong>cidade</strong>computacional têm vindo a conferir aos Veículos AéreosNão Tripulados (VANT) níveis crescentes de robustez efiabilidade em operações efetuadas em ambientes instáveise eventualmente remotos. O nosso projeto visoutestar a utilidade deste tipo de abordagem na recuperaçãode dados relacionados com questões específicasda arqueologia, em lugar de depender das bases dedados disponíveis no mercado, em geral insatisfatórias,de difícil acesso e elaboradas com outros propósitos.Também se tiraram algumas fotografias aéreas de baixaaltitude. Os ensaios com um balão de hélio sobre osítio urbano e, sobretudo, com um balão estacionário19

13urban site and most of all with an helikite configurationover the Roman granite quarry atPitaranha allowed some detailed mapping offeatures visible above ground 12.At the same time, topographical research and datacollectionfocused on ground-based TLS (TerrestrialLaser Scanning) systems for the recording of standing-remainsand to the extensive use of GPS as atopographical survey method. High point-densitysurveys of the extant temple-podium located inthe forum of the Roman town and Porta Sul wereconducted in collaboration with The DiscoveryProgramme (Rep. Ireland) which allowed us to producehighly accurate visualisations of these monumentsand to explore their construction through adynamic digital environment 13.Topographical surveyThe topographical survey of the site was undertakenwith a Differential Global PositioningSystem. This system was set to sample at a constantrate as it was carried across the site by operatorswearing a back-pack. In this way a dense,but also rapid, dataset could be collected, allowingus to produce a topographic model accurateto within a few centimetres.Artefact surveyArtefact survey or analytical survey is a tool usedby landscape archaeologists, which collects physicalinformation about the location, distributionand organisation of past human activities acrossa landscape. Archaeological field survey is a formof non-intrusive prospection, where the density ofarchaeological material on the surface is measuredby systematic counting 14. Ploughing and otheragrarian activities disturb archaeological layersunder the ground and expose archaeological material(pottery, glass, building material, slag etc.) bybringing it up to the surface.sobre a pedreira de granito <strong>romana</strong> de Pitaranha, permitiramfazer parte do mapeamento detalhado doselementos visíveis à superfície do terreno 12.Em simultâneo, a investigação e recolha de dadostopográfica empregou um sistema de digitalização alaser a partir do solo TLS (Terrestrial Laser Scanning)para efetuar o registo dos vestígios ainda conservados,bem como o uso extensivo de GPS como método deprospeção topográfica. Os levantamentos com altadensidade de pontos do ainda visível pódio do templo,situado no fórum da <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong>, bem comoda Porta Sul, foram conduzidos em colaboração como projeto The Discovery Programme (República daIrlanda), o que permitiu visualizar estes monumentoscom alta precisão e explorar a sua construção atravésde um ambiente digital dinâmico 13.Levantamento topográficoO levantamento topográfico do sítio arqueológicoutilizou um Sistema Diferencial de PosicionamentoGlobal (Differential Global Positioning System). Estesistema foi programado para recolher informação a umritmo constante, e foi executado por operadores quepercorreram todo o sítio, transportando o equipamentoem mochilas. Deste modo, foi possível reunir, numcurto espaço de tempo, um denso conjunto de dadosque permitiu produzir um modelo topográfico com umnível de precisão de poucos centímetros.Prospeção de artefactosA prospeção de artefactos, ou levantamento analítico,é uma ferramenta utilizada na Arqueologia Espacialque recolhe informação física sobre a localização,distribuição e organização das atividades humanas dopassado numa dada paisagem. A prospeção arqueológicade terreno é uma estratégia não-invasiva, atravésda qual a densidade do material arqueológico existenteà superfície do terreno é sistematicamente registada econtabilizada 14. A lavoura e outras atividades agrícolasperturbam as camadas arqueológicas do subsolo,trazendo à superfície o material arqueológico (cerâmica,vidro, material de construção, escória, etc.).A articulação dos dados resultantes da coleta de artefactoscom outro tipo de informação não constitui umprocesso linear. Este tipo de levantamento funcionaem complementaridade com a deteção remota. Nossítios arqueológicos complexos, que foram habitados aolongo de séculos, não é possível estabelecer qualquer20

Integration of artefact survey results with otherdata is not straightforward. Artefact survey iscomplementary to remote sensing. On complexsites that were used for centuries, we cannotassume any direct relationship between structuralremains, visible using remote sensing, andthe surface record of artefact distribution. This isbecause the formation of the surface record oncomplex sites is an extremely complex process orpalimpsest of processes. We can summarize it sayingthat what we see through surface-collectionis a result of the process of building, use, abandonment,and post-abandonment transformationsoften operating side by side and making the surfacepopulation a complex palimpsest of differentnatural and cultural transformations.In <strong>Ammaia</strong>, the main objective of the fieldwalkingtest was to provide a comparative data set whichwould enable us to study the variation in formationprocesses that formed the surface record and theirrelationship to features detected by remote sensing.We are especially interested in the relationshipbetween the town and its immediate environment,and thus to a better understanding of suburbandevelopment around formally constituted towns.Traditionally Mediterranean field-survey on complexsites has often been limited to countingceramic sherds and building material within aregular grid with further study conducted onlyon diagnostic sherds. However, it is extremelycorrelação direta entre os vestígios estruturais visíveisna deteção remota e a distribuição dos artefactos pelasuperfície. Esta circunstância deve-se à extrema complexidadedo processo de formação do registo de superfícieem sítios arqueológicos deste tipo. Podemos resumir aquestão dizendo que o registo das recolhas de superfícieresulta de transformações decorrentes de processos deconstrução, utilização, abandono e pós-abandono, muitasvezes ocorridos em simultâneo, tornando a amostrade superfície num complexo palimpsesto de diferentestransformações naturais e culturais.Em <strong>Ammaia</strong>, o grande objetivo da prospeção desuperfície (fieldwalking) foi estabelecer uma basede dados comparativa que possibilitasse o estudo davariação nos processos de formação que geraram oregisto superficial, bem como a sua correlação com oselementos identificados por deteção remota. É particularmenteinteressante o estudo da relação entre a<strong>cidade</strong> e a sua zona envolvente, de modo a obtermosuma melhor compreensão do desenvolvimento dossubúrbios em <strong>cidade</strong>s formalmente estabelecidas.A tradicional prospeção de campo de sítios arqueológicoscomplexos nas áreas mediterrâneas limita--se à recolha e contagem de fragmentos cerâmicos emateriais de construção recolhidos no interior de umaquadrícula previamente estabelecida, limitando-se oestudo subsequente aos fragmentos mais significativos.No entanto, é extremamente difícil reconhecerno trabalho de campo os fragmentos de cerâmicacom bom potencial de diagnóstico, em particular no14

difficult to recognise diagnostic sherds in thefield, especially for often-inexperienced studentswho form the bulk of the usual workforce. On theother hand, we believe that simple counts do notgive enough information about the processes thatformed the surface distribution. We experimentedwith different sampling methods. At <strong>Ammaia</strong> however,our strategy consisted of a combination ofsubsurface sampling using shovel-pits and drysieving of material with traditional surface-surveyin areas which had been recently ploughed.In order to interpret the processes behind theassemblages we believe that it is insufficient tocount only the absolute number of sherds andinvestigate distributions of single classes of material,rather it is necessary to compare the compositionsof whole assemblages.The results do not simply reveal functional divisionswithin the town, rather they should be seenas material residues of long-term daily practices.By identifying waste streams through which refuseenters the archaeological record and the ploughsoilassemblage we can address questions aboutthe organisation of waste disposal and attitudestowards rubbish. In this way we can begin tounderstand ancient towns as places in which peoplelived, and not just as architectural settings.Care must however be taken, as the spatial distributionof artefacts at long-term habitationsites may not represent other activities besidestheir disposal. A direct comparison between surface-collectionand geophysical survey or aerial-photographycan therefore be problematic.Interpreting surface distributions in terms of functionalactivities, and thus inferring the function ofstructures visible on a geophysics plan, is overlysimplistic, especially for complex townscapes.Geophysical surveysOne of the primary outcomes of the project wasthe completion of magnetic gradiometry datacollectionacross the site of <strong>Ammaia</strong>, to revealfor the first time the intra-mural plan of thetown 18. We also undertook targeted collectionof earth-resistance data to better understandaspects of the magnetic plan. As part of undertakingthese field surveys we developed networksof contact with topographical surveyors fromcaso dos estudantes, muitas vezes inexperientes, queconstituem o grosso da mão-de-obra habitual nestestrabalhos. Por outro lado, não nos parece que assimples contagens forneçam informação suficientesobre os processos formativos do registo de superfície.Experimentaram-se diferentes métodos de amostragem.Todavia, a nossa estratégia em <strong>Ammaia</strong> consistiunuma combinação de amostras de «subsuperfície»obtidas através de sondagens limitadas de teste ecrivagem a seco com a tradicional prospeção de superfície,em áreas recentemente lavradas.Para interpretar as condicionantes das amostras reunidas,consideramos que a simples contagem do númeroabsoluto de fragmentos e a observação da distribuiçãode determinadas classes de artefactos são insuficientes.A nosso ver, é necessário comparar as composiçõesdos conjuntos no seu todo.Os resultados obtidos não revelam somente divisõesfuncionais no interior da <strong>cidade</strong>, e devem ser sobretudovistos como resíduos materiais de práticas quotidianasde longa duração. Se identificarmos os fluxos de resíduosatravés dos quais os detritos entram no registoarqueológico e na associação de conjuntos do solo arável,podemos ensaiar a abordagem a questões como aorganização da eliminação de resíduos ou o tratamentodos detritos. Podemos assim começar a entender as<strong>cidade</strong>s antigas como lugares habitados por pessoas,e não apenas como configurações arquitetónicas.Todavia, devemos ser cautos, uma vez que a distribuiçãoespacial de artefactos em habitats de longaduração pode não indicar nada mais do que a sua simplesdispersão. A comparação direta entre a recolha àsuperfície e a prospeção geofísica ou fotografia aéreapode, portanto, ser difícil. Interpretar a distribuiçãosuperficial com base nas presumidas atividades funcionaise, desse modo, aferir a função das estruturasvisíveis no levantamento geofísico, é uma abordagemdemasiado simplista, em particular no caso de paisagensurbanas complexas.Prospeções geofísicasUm dos mais importantes resultados do projeto foia conclusão da recolha de dados por gradiometriamagnética em todo o sítio de <strong>Ammaia</strong>, que viriarevelar pela primeira vez a planta intramuros da<strong>cidade</strong> 18. Também efetuámos uma recolha seletivade dados de resistividade elétrica para melhor compreenderalguns aspetos da planta magnética. No âmbito22

the technical college in Portalegre, and with theSpanish Institute for Archaeology in Merída. Thegeomagnetic survey used a man-portable twinsensorarray to enable relatively rapid coverageover a variety of terrain which included pasture,heavily overgrown areas and land under activecultivation. The earth-resistance survey used atwin-probe array as this has been demonstrated tobe highly effective for the recovery of near-surfacearchaeological remains. This array was configuredwith two parallel 0.5m probe-separation arrays inorder to increase the rapidity of the survey, andan additional measurement was taken across theouter probes to provide a collocated 1m probeseparationarray capable of measuring resistanceat a greater depth than the 0.5m arrays.Both the magnetic (gradiometer) and earth-resistancesurveys carried out in the intramural area of<strong>Ammaia</strong> were based on a gridded collection strategy.This method relies on the establishment of aregular grid across the site (in this case 20x20msquares) within which measurements of geophysicalproperties are recorded at regular intervals.For the gradiometric survey these intervals were0.25x0.5m, the earth-resistance survey was undertakenat a slightly coarser (though higher thannormal) resolution of 0.5x0.5m but with the addedbenefit of a concurrent, secondary survey at aresolution of 0.5x1.0m which provided informationabout archaeological remains existing at adestas prospeções no terreno, desenvolvemos redes decolaboração com topógrafos do Instituto Politécnicode Portalegre e com o Instituto de Arqueologia deMérida, em Espanha. A prospeção geomagnética usouum dispositivo portátil de sensores duplos para permitiruma rápida cobertura de vários tipos de terreno,como áreas de pasto, áreas com densa cobertura vegetale zonas de cultivo ativo. A prospeção de resistividadeelétrica usou uma série de sondas duplas, dadaa sua comprovada eficácia no registo de vestígiosarqueológicos próximos da superfície. Este aparelho foiconfigurado com dois conjuntos paralelos de sondas,separadas a uma distância de 0,5 m, a fim de aumentaro ritmo da prospeção. Realizou-se uma mediçãoadicional com o uso de sondas externas, criando-seum aparelho com uma distância de 1 m entre sondas,capaz de medir a resistividade a uma maior profundidadedo que o dispositivo de 0,5 m.Tanto a prospeção magnética (gradiómetro) como a deresistividade elétrica, ambas realizadas na área intramurosde <strong>Ammaia</strong>, tiveram por base uma quadrículade referência. Este método consiste na projeção sobreo terreno de uma retícula de quadrados (neste caso de20 x 20 m), dentro da qual as medições das propriedadesgeofísicas são registadas a intervalos regulares.Para o levantamento gradiométrico, estes intervalosmediam 0,25 x 0,5 m. A prospeção de resistividadeelétrica utilizou uma resolução ligeiramente menoscerrada (porém mais elevada do que a habitual) de0,5 x 0,5 m, mas com a vantagem acrescida de uma15

slightly greater depth below the ground surfacethan the gradiometric technique.With a team from Eastern Atlas (a Berlin-basedgeophysical survey company partner in the project),we also completed gradiometer survey ofapproximately 15 hectares of extramural landusing a six-sensor cart linked to a real-time GPSpositioning device 16. This technology currentlyrepresents one of the main strands of “state-ofthe-art”development in archaeological geophysicalprospection techniques and methodologies, itsapplication at the site of <strong>Ammaia</strong> represented anopportunity to both deepen our understanding ofthe practical functioning of this technology andto allow Eastern Atlas an opportunity to furtherdevelop their technology. These extra-mural surveyshave provided some answers to questionswhich it was not possible to answer from theintra-mural survey alone and have provided additionaldetail to support interpretations of thetown-plan. Principally, the results of the extramuralgradiometer surveys have enabled us tolocate areas of occupation or activity between thetown and the Sever river, confirming that this areawas actively used and occupied in Antiquity (seepp. 44-47). To the north of the site, the surveysconfirmed the presence of a road leading to thenorth and also the lack of structures in the areapreviously thought to be a theatre.The undertaking of high-resolution GroundPenetrating Radar (GPR) survey at the site wasalso conducted by the partner team of GhentUniversity. Multi-sensor arrays were used to map,in extremely high-detail, buried structures 23.As part of this work we were also able to surveythe main road (the N359) from Portalegre, whichruns through the middle of the site 29. As GPRis the only technique capable of reliably penetratingasphalt surfaced roads, this techniqueenabled us to survey an area which on many siteswould have to be written off as unavailable forsurvey. We have therefore succeeded in collectingdata from a critical area across the centre ofthe site, coinciding with the supposed southernand northern corners of the wall-circuit, andalso gained information and an insight into theconditions of preservation, and ability of GPRto recover meaningful archaeological data, fromsegunda prospeção, em simultâneo, cuja resoluçãofoi de 0,5 x 1 m, gerando informações sobre vestígiosarqueológicos existentes a uma profundidade umpouco maior relativamente à linha de superfície do quea permitida pela técnica gradiométrica.Com uma equipa da Eastern Atlas (empresa de prospeçãogeofísica sediada em Berlim e entidade parceiraneste projeto), também concluímos um levantamentogradiométrico de aproximadamente 15 hectares deterreno extramuros, utilizando um veículo com seissensores ligado a um dispositivo GPS de posicionamentoem tempo real 16. Atualmente, esta tecnologiarepresenta uma das principais vertentes de ponta noque respeita a técnicas e metodologias de prospeçãogeofísica em arqueologia. A sua aplicação no sítio de<strong>Ammaia</strong> representou não só a possibilidade de aprofundarmoso nosso conhecimento sobre o funcionamentoprático desta tecnologia, como a oportunidade de aEastern Atlas continuar a desenvolvê-la. Estas prospeçõesextramuros forneceram algumas respostas aquestões a que a prospeção intramuros por si só nãopermitia responder e acrescentaram novos pormenoresàs interpretações da planificação urbana. Os resultadosdos levantamentos gradiométricos extramuros, em particular,permitiram-nos localizar áreas de ocupação eatividade entre a <strong>cidade</strong> e o rio Sever, o que confirmaque esta área foi ativamente utilizada e ocupada naAntiguidade (ver pp. 44-47). Na região setentrional dosítio, as prospeções confirmaram a presença de umaestrada de ligação ao norte, bem como a ausência deestruturas numa área em que se pensava ter existidoum teatro.A realização da prospeção com georadar de altaresolução (GPR – Ground Penetrating Radar) no sítioarqueológico também foi conduzida por uma equipada Universidade de Ghent, parceira neste projeto.Usaram-se veículos multisensores para mapear, comextremo detalhe, as estruturas soterradas 23. <strong>Uma</strong>parte desta tarefa consistiu na prospeção da área daestrada procedente de Portalegre (N359) que atravessao sítio 29. Dado que o GPR é a única técnica capazde penetrar com fiabilidade em estradas revestidas aasfalto, esta técnica permitiu-nos examinar uma áreaque em muitos sítios arqueológicos teria sido excluídapor não ser passível de estudo. Fomos, portanto, bem--sucedidos na recolha de dados sobre uma área críticasituada no centro da <strong>cidade</strong>, coincidente com as esquinassul e norte do circuito das muralhas, e reunimos,24

16 17beneath modern roads. This latter applicationhas obvious wider implications for cultural managementstrategies beyond this particular site.Ground truthingTesting of the survey results was achieved througha number of methods employed to directly observearchaeological conditions under the ground. Inpart, the shovel-pitting described above as part ofthe artefact survey gave a small window into theploughsoil horizon, though this should perhapsnot really be seen as a means to ground-truth thesurvey as it only confirmed the situation withinthe uppermost c. 15cm of the ploughsoil.In contrast, the augering survey undertaken as apart of the geomorphological research at <strong>Ammaia</strong>also provided a means of confirming the locationof buried structures and, as a by-product, enabledthe retrieval of small quantities of archaeologicalmaterial within the samples taken 17.The most effective means of corroborating thehypotheses derived from the geophysical surveysremained full-excavation. Two campaigns wereundertaken as a complement to the non-intrusivesurveys of the Radio-Past project. Firstly an areaof the forum, adjacent to the temple podium,and a section of the cryptoporticus to its northwere excavated in 2010-2011 (see pp. 32-35).Secondly additional work was undertaken in 2011at the public baths which had been the focus ofexcavation in the preceding years.P.S.J.além disso, informações e novos conhecimentos sobreas condições de preservação e a utilização de GPR narecuperação de dados arqueológicos significativosocultos sob estradas modernas. Esta aplicação temobviamente implicações mais vastas nas estratégias degestão cultural que ultrapassam este sítio específico.Verificação de dados no terreno (sondagens)O teste aos resultados da prospeção empregou váriosmétodos cuja utilização visava observar diretamenteas condições do subsolo. Em parte, as sondagens deteste anteriormente descritas no âmbito do levantamentode vestígios artefactuais abriram uma pequenajanela sobre a camada de solo arável, facto que noentanto não deve ser encarado como meio de verificaçãoda prospecção, dado que apenas serviu paraobservar as condições e potência da camada de soloarável mais próxima da superfície (c. 15 cm).Em contraste, os trabalhos de perfuração e sondagemlevados a cabo no âmbito da investigação geomorfológicaem <strong>Ammaia</strong> também constituíram um meio deconfirmação da localização das estruturas soterradase, consequentemente, permitiram recuperar pequenasquantidades de material arqueológico juntamente comas amostras recolhidas 17.O meio mais eficaz de corroborar as hipóteses levantadaspelas prospeções geofísicas continua a ser a escavaçãoem área. Foram realizadas duas campanhas comocomplemento das prospeções não-invasivas realizadasno âmbito do projeto Radio-Past. Numa primeira fase,entre 2010-2011, escavou-se uma área do fórum, adjacenteao pódio do templo, e uma secção do criptopórtico,a norte (ver pp. 32-35). Posteriormente, em 2011,realizaram-se trabalhos de escavação adicionais nastermas, já anteriormente sujeitas a outras intervenções.P.S.J.25

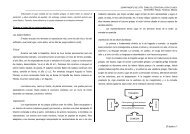

Legendriver SeverriversRoman wallsRoman walls hypotheticalcontour (5m)GPRMAGRES (0.5m) 0 2

Sever5Meters50 100 150 20018

19The newest resultsThe integration of fieldwork, targeted excavations,remote sensing, survey and geophysical prospectionresults has enabled the production of an understandingof the general layout of the Roman town.We have been able to propose an hypotheticalwall circuit, the position of which is sure alongthe southern and eastern side, to sketch the mainroad network in the suburbs and to locate somenecropoleis and some industrial or productive sectorsof the outskirts 18, 35. The surface enclosedin the wall-circuit of our proposal was surely notall urbanised: the slope of the Malhadais hill istoo steep to allow building, but we think that thehilltop was included for strategic reasons.We traced the two main aqueducts providingwater to the urban centre and we determinedOs resultados mais recentesA integração dos resultados obtidos com o trabalhode campo, as escavações seletivas, a deteçãoremota e a prospeção geofísica conduziram à delimitaçãoda planta geral da <strong>cidade</strong> <strong>romana</strong>.Conseguimos delinear o traçado hipotético dasmuralhas, com segurança nos tramos sul e oriental,bem como esboçar a rede viária principal dossubúrbios e localizar algumas necrópoles e setoresindustriais ou produtivos da periferia 18, 35. Asuperfície delimitada pelo circuito das muralhasagora proposto decerto não estaria completamenteurbanizada: a encosta da colina de Malhadais édemasiado íngreme para permitir a construção, maspensa-se que o topo da colina terá sido incluídopor motivos estratégicos.Localizámos os dois principais aquedutos que28

the street grid in which the town was laid out.We know that some of the main streets of thetown were flanked by porticoes. On the basis ofcomparative research and of the architecturalpieces found on the site, we can reconstructthem as segments of arcades lining some sides ofa few blocks 20. These arrangements are partiallydecorative and partially functional means to add“decor” to urban road axes and at the same timeto offer comfort to passers-by and shelter forpedestrians. These arcades, in fact, elevate theurban axes to the level of “showpiece streets”and they are a very clear example of how, inancient towns, streets were not simply regardedas pathways connecting one place to another.Rather, the function of these covered passagewaysis to create public space for business andsocial activities in whatever weather condition.forneciam água ao centro urbano e delineámos arede de ruas em torno da qual a <strong>cidade</strong> foi planificada.Sabemos que algumas das ruas principaiseram ladeadas por pórticos. Por comparação comoutras <strong>cidade</strong>s <strong>romana</strong>s conhecidas, associada aoselementos arquitetónicos encontrados no sítio, épossível reconstituí-los como segmentos de arcadascontínuas, correndo ao longo das fachadasde alguns dos edifícios 20. Estas estruturas sãosimultaneamente decorativas e funcionais, conferindo«décor» aos eixos viários urbanos e, aomesmo tempo, proporcionando conforto e abrigoaos transeuntes. Com efeito, estes pórticos dotamos eixos urbanos de uma forte qualidade estéticae constituem um claro exemplo de que as ruas dasantigas <strong>cidade</strong>s não eram simples caminhos entreum lugar e outro. Pelo contrário, estes pórticosdestinavam-se a gerar espaços públicos onde se29

20Substantially, these arcades make you feel as ifyou are inside a town and not outside a building.In <strong>Ammaia</strong>, rows of tabernae are often presentalong the inner sides of these porticoes.Even if with uncertainty, for these porticoes wecan propose a reconstruction for the first phasewith a one-storey single pitched roof, with tilesand roof tiles, supported by rows of granite columnscomposed of several drums (an earlier phasewith wooden installations can be conceived), upto a height of around 3.02m (c. 10 Roman feet).In the following phases, we can expect thesearcades to be affected by transformations, implyingalso enlargements of the portico’s width andoften conversion into enclosed spaces, with theconstruction of walls between the columns orpillars and the infilling of the bays.We can re-enact now the main public monuments:the forum, the public baths, the squareat the southern gate, and understand the plan ofmost of the blocks, with houses of different typesand shops. Of course, the image we have thanksto our research is a “synchronical” one, meaningthat different phases, related to transformationsand changes which have affected thesebuildings, sometimes during several centuries ofoccupation, are all “squashed” into one plan. Inmost cases we cannot understand the real evolutionsof these buildings, but in some examples,mostly the 3-dimensional information collectedby means of GPR survey, integrated with somepoderiam realizar atividades comerciais e sociais,independentemente das condições meteorológicas.Na realidade, estas arcadas dão a sensação de seestar no interior de uma <strong>cidade</strong>, e não no exteriorde um edifício. Em <strong>Ammaia</strong>, era frequente existiremtabernae (lojas) alinhadas sob estes pórticos.Ainda que com algum grau de incerteza, numa primeirafase, podemos reconstituir os pórticos comoestruturas elevadas até ao nível de um primeiroandar, com telhado de uma só água, suportadas porfiadas de colunas de granito com fustes compostospor vários tambores (é admissível a existência deuma fase anterior com postes de madeira), com umaaltura total de 3,02 m (c. 10 pés romanos).Em fases posteriores, é possível que estas arcadastenham sofrido transformações, nomeadamente oalargamento do vão entre colunas e frequentementea sua conversão em espaços fechados através daconstrução de paredes entre as colunas.Podemos agora reconstituir os principais edifíciospúblicos: o fórum, os banhos públicos, a praçajunto à Porta Sul, bem como identificar a plantada maioria dos quarteirões, que incluíam casasde diferentes tipologias e lojas. É evidente quea imagem de que dispomos graças à investigaçãoconduzida é «sincrónica», ou seja, as diferentesfases decorrentes das transformações e alteraçõesque afetaram estes edifícios, por vezes ao longo devários séculos de ocupação, estão todas «amalgamadas»numa única planta. Na maioria dos casos,não conseguimos definir as diferentes fases destas30

focused stratigraphic ground-truthing and higherresolution earth-resistance survey, the definitionof a certain phasing in the transformationof urban houses is possible. Most blocks of theurban grid seem to be partly or sometimes fullyoccupied by housing complexes, even if commercialand artisanal functions (tabernae, workshops,etc.) are also present in many insulaewhere some are no doubt directly associated withthe domestic functions 21.In different sectors we have been able not only todistinguish easily all essential walls, floors andeven columns, but also other meaningful linearstructures, such as local aqueducts or drainagesystems, and the associated basins, fountains,impluvia or cisterns, and sometimes even ovens,cooking installations and hypocausts, the “heatingsystems” of Antiquity.What we can see through the “radiography of thesubsoil” is a town carefully planned, accordingto a regular grid. Not all the blocks have thesame dimensions though. The two central rowsof blocks are bigger, as in the very centre of thisgrid the big complex of the forum, the monumentalcentre of the town was located 18.Of this “heart of the city” not much is preserved,only the almost unrecognizable concrete core ofthe main temple is still standing, but much moreis known now thanks to excavations and geophysicalsurvey: let’s go and walk through it!C.C.estruturas. Mas em alguns, sobretudo graças àinformação tridimensional obtida por georadar, emconjunto com algumas sondagens estratigráficase prospeções geofísicas seletivas de alta resolução,foi possível identificar algum faseamento natransformação das habitações. A maior parte dosquarteirões parece ter sido parcial ou totalmenteocupada por complexos habitacionais. Ainda quese tenham detetado em muitas insulae atividadescomerciais e artesanais (tabernae, oficinas, etc.),parte delas está sem dúvida diretamente relacionadacom funções domésticas 21.Em diferentes sectores foi possível não só distinguirclaramente todas as paredes, pavimentos e mesmocolunas, como também identificar outras estruturaslineares significativas, como aquedutos, sistemas dedrenagem e respetivos reservatórios, fontes, impluviaou cisternas e, por vezes, até mesmo fornos, cozinhase hipocaustos, os «sistemas de aquecimento»da Antiguidade.O que podemos ver através da «radiografia dosubsolo» é uma <strong>cidade</strong> cuidadosamente planeadasegundo uma malha regular. No entanto, nem todosos quarteirões têm as mesmas dimensões. As duasfiadas centrais são maiores, dado que o grande complexodo fórum – o centro monumental da <strong>cidade</strong>– se situava no centro desta malha urbana 18.Deste «coração da <strong>cidade</strong>» pouco se conserva, apenaso já quase irreconhecível núcleo de betão do pódiodo templo principal. Todavia, sabemos hoje muitomais graças às escavações e à prospeção geofísica.Venha conhecê-lo!C.C.21