Sequentielle Verteilungsspiele ¨Uberblick Das Ultimatumspiel ...

Sequentielle Verteilungsspiele ¨Uberblick Das Ultimatumspiel ...

Sequentielle Verteilungsspiele ¨Uberblick Das Ultimatumspiel ...

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

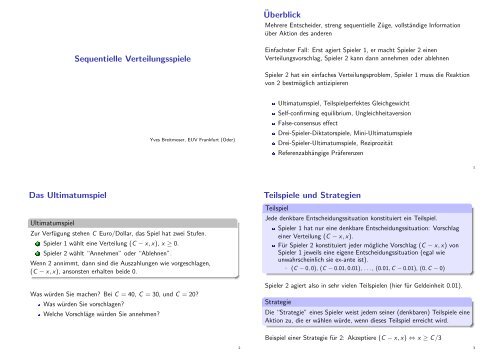

ÜberblickMehrere Entscheider, streng sequentielle Züge, vollständige Informationüber Aktion des anderen<strong>Sequentielle</strong> <strong>Verteilungsspiele</strong>Einfachster Fall: Erst agiert Spieler 1, er macht Spieler 2 einenVerteilungsvorschlag, Spieler 2 kann dann annehmen oder ablehnenSpieler 2 hat ein einfaches Verteilungsproblem, Spieler 1 muss die Reaktionvon 2 bestmöglich antizipierenYves Breitmoser, EUV Frankfurt (Oder)<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>, Teilspielperfektes GleichgewichtSelf-confirming equilibrium, UngleichheitaversionFalse-consensus effectDrei-Spieler-Diktatorspiele, Mini-<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>eDrei-Spieler-<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>e, ReziprozitätReferenzabhängige Präferenzen1<strong>Das</strong> <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong><strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>Zur Verfügung stehen C Euro/Dollar, das Spiel hat zwei Stufen.1 Spieler 1 wählt eine Verteilung (C − x, x), x ≥ 0.2 Spieler 2 wählt “Annehmen” oder “Ablehnen”.Wenn 2 annimmt, dann sind die Auszahlungen wie vorgeschlagen,(C − x, x), ansonsten erhalten beide 0.Was würden Sie machen? Bei C = 40, C = 30, und C = 20?Was würden Sie vorschlagen?Welche Vorschläge würden Sie annehmen?Teilspiele und StrategienTeilspielJede denkbare Entscheidungssituation konstituiert ein Teilspiel.Spieler 1 hat nur eine denkbare Entscheidungssituation: Vorschlageiner Verteilung (C − x, x).Für Spieler 2 konstituiert jeder mögliche Vorschlag (C − x, x) vonSpieler 1 jeweils eine eigene Entscheidungssituation (egal wieunwahrscheinlich sie ex-ante ist).◮ (C − 0, 0), (C − 0.01, 0.01), . . . , (0.01, C − 0.01), (0, C − 0)Spieler 2 agiert also in sehr vielen Teilspielen (hier für Geldeinheit 0.01).StrategieDie “Strategie” eines Spieler weist jedem seiner (denkbaren) Teilspiele eineAktion zu, die er wählen würde, wenn dieses Teilspiel erreicht wird.Beispiel einer Strategie für 2: Akzeptiere (C − x, x) ⇔ x ≥ C/323

Teilspielperfektes Ggw: EinkommensmaximierungStrategieprofilEin Strategieprofil ist eine Kollektion von (vollständigen) Strategien aller Spieler.Welche Strategieprofile sind plausibel? Vielleicht folgende:Teilspielperfektes Gleichgewicht: EinkommensmaximierungEin Strategieprofil ist ein TSP-Ggw, wenn es so gestaltet ist, dass jeder Spieler injedem Teilspiel sein Einkommen maximiert – unter der Annahme, dass allefolgenden Aktionen so ablaufen, wie in dem Strategieprofil angekündigt.Konsequenz: In TSP-Ggws durchschaut Spieler 1 mögliche Bluffs (leereDrohungen) von Spieler 2Bluff: “Ich mache etwas unsinniges, wenn Du . . . machst.”Bspw. “Ich lehne das Angebot ab wenn x < C/3” obwohl erEinkommensmaximierer istDenn dies widerspräche der Einkommensmaximierung in diesen Teilspielenund ist in TSP-Ggws allein dadurch ausgeschlossen.Die TSP-Ggws bei Geldeinheit 0.01Für Spieler 2 folgt aus EinkommensmaximierungAnnehmen des Vorschlags (C − x, x) falls x > 0Er ist indifferent bei x = 0, dann kann er annehmen oder ablehnenIm TSP-Ggw antizipiert Spieler 1 die Strategie von 2, und daher folgt fürihn aus EinkommensmaximierungMach den Vorschlag (C − x, x) für das kleinste x, das 2 annimmtEs gibt nun zwei (reine) TSP-Ggws bei EinkommensmaximierungSpieler 2 nimmt x = 0 an, und 1 schlägt (C − 0, 0) vorSpieler 2 lehnt x = 0 ab, und 1 schlägt (C − 0.01, 0.01) vor45<strong>Das</strong> TSP-Ggw bei Stetigkeit (Geldeinheit → 0)<strong>Das</strong> erste Gleichgewicht bleibt erhaltenSpieler 2 nimmt x = 0 an, und 1 schlägt (C − 0, 0) vorGibt es aber auch ein Gleichgewicht, wo 2 x = 0 ablehnt?Aus Einkommensmaximierung folgt ja, dass 2 alle (C − ε, ε) mit ε > 0annimmtWas ist dann die optimale Strategie von 1?Es gibt keine! Für jedes ε > 0, das 1 vorschlagen könnte, gibt es noch einbesseres ε ′ = ε/2, das 1 mehr bringt und das 2 auch annehmen würdeDa es keinen optimalen Vorschlag gibt, gibt es auch keinen Vorschlag der dieOptimalitätsbedingung des TSP-Ggws erfülltAlso gibt es kein solches TSP-Ggw, d.h. keines, in dem 2 den Vorschlagx = 0 ablehntBei Stetigkeit nimmt 2 den Vorschlag x = 0 im eindeutigen TSP-Ggw an(Der Unterschied ist aber minimal, ob 0.01 oder 0 ist praktisch egal)Was passiert in den Experimenten?Übliches experimentelles DesignJeder Teilnehmer spielt das Spiel 10 mal, mit wechselnden Partnern, aberimmer in der gleichen Rolle (immer Proposer oder immer Responder)Übliche ErgebnisseDie Vorschläge x sind im allgemeinen im Bereich 40%–50% von CKleinere Vorschläge werden mit recht hoher Häufigkeit abgelehntDaher sind die empirisch optimalen Vorschläge auch im Bereich 40%–50%<strong>Das</strong> gilt in allen entwickelten Ländern bei C von 10–30 DollarBei höheren C (bspw. Wocheneinkommen) werden auch geringere Vorschägeakzeptiert, aber nur selten unter 20%In Entwicklungsländern sind 50 Dollar schon Monatseinkommen, dann sinkendie Ablehnungsraten noch etwasDer Median-Vorschlag bleibt aber bei 40%–50% von C (meistens), mglw.wegen Risikoaversion auf Seiten des Proposers (bei diesen hohen Summen)67

Erfahrung (Cooper/Dutcher, 2011, Meta-Analyse)The dynamics of responder behavior in ultimatum games 529Alternative KonzepteWenn es keine Konvergenz zum TSP-Ggw gibt, dann nutzen die Personenvielleicht ein “einfacheres” GleichgewichtskonzeptBspw. Nash-Gleichgewicht: Beide Akteure legen ihre Strategien gleichzeitig festSpieler 1 auf ein AngebotSpieler 2 auf eine Liste der Angebote, die er annehmen würdeWenn das Angebot kommt, überlegt er nicht mehr, was gut wäre, sondernschaut nur auf seine Liste (gedanklich)Fig. 1 Acceptance rate as a function of experience. Note: The numbers above the bars give the number ofobservations for that barMit Erfahrung sinkt die Annahme schlechter Angebote (< 20%) und steigtdie Annahme guter Angebote (≥ 20%), aber beides nur leichtOptimaler Vorschlag bleibt im Bereich 40%–50%Keine Konvergenz zum TSP-Ggw bei Einkommensmaximierungin acceptance rates for high offers is small and would be hard to identify with fewerobservations. The magnitude of the decrease for small offers is larger, but given theinfrequency of low offers we would once again struggle to identify the effect withouta sizable dataset.Because the effects shown in Fig. 1 are subtle, it is particularly important to establishstatistical significance. The regression analysis shown in Table 2 does so. Theseregressions use all observations in the dataset (rather than only using Rounds 1–10).The dependent variable is a dummy for whether the offer was accepted. Since this is abinary variable we use a probit model. It is critical that we control for session effects.Only 15 of the 44 sessions in our dataset (4 of 7 papers) last more than ten rounds.Without controls for session effects, changes due to experience are confounded withany idiosyncratic features of the 15 long sessions. All of the regressions thereforeinclude session dummies. Parameter estimates for these dummies are not reportedin Table 2 as they are of little economic importance and take up a lot of space. Fullcopies of the regression output are available upon request. Standard errors are correctedfor clustering at the individual responder level.The primary independent variables are a dummy for “late” rounds and the (truncated)percentage of the pie offered to the responder. Late rounds are defined asRound 6 and later. More than 2/3 of the subjects are in sessions that have only tenrounds, so a late round corresponds to the second half of a modal session. 19 TheSelf-Confirming EquilibriumDie Idee (TSP-Ggw ist zu streng) wurde in Lern-Modellen weiterentwickeltAnnahme: Menschen lernen die Strategien der anderen nur durch “direkteErfahrung” kennen (keine Introspektion, und keine Beschreibung inZeitungen, Romanen, Filmen, etc.)Dann konvergiert die Gesellschaft zu einem Ggw, in dem jeder einzelne dieStrategien der anderen nur unvollständig kennt/antizipiert – nur entlang des“Gleichgewichtspfades” – und auf diesen Belief spielen sie eine beste AntwortDiese Ggws heißen “Self-Confirming” Ggws und sind (leicht) schwächer alsNash-Ggws, da Spieler falsche Beliefs abseits des Ggw-Pfades haben können19 We have experimented with moving the breakpoint for late rounds to different time points. As long asthe shift is small (i.e. a couple of rounds) there is little qualitative effect.Was spricht für und gegen Nash und SC Ggws als Erklärung für dieErgebnisse der <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>ePro Theoretisch können sie erklären, warum 40% vorgeschlagen undangenommen werden, ohne dass Altruismus im Spiel ist, und warum bspw.20% abgelehnt werden, ohne dass Missgunst im Spiel istCon Praktisch scheint mangelhafte Antizipation der Reaktion auf Vorschlägeunter 40% nicht vorzuliegen (siehe nächstes Experiment); und dieseablehnenden Reaktionen wirken nicht wie “Auf dem falschen Fuß erwischt”810Jedes Ergebnis des <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>s kann sich in einem Nash-Ggw ergebenBeliebiges Ergebnis (C − x, x) ergibt sich wenn 1 das vorschlägt und 2 sich darauffestlegt, nur das anzunehmen; 1 kann nicht profitabel abweichen, denn 2 ist(gedanklich) darauf festgelegt, alles andere abzulehnen – plausibel?Da es viele Nash-Gleichgewichte gibt, gibt es KoordinationsproblemeWenn sie unterschiedliche Ggws spielen, kommt es zur AblehnungAblehnungen sind Missverständnisse, Spieler 2 auf dem falschen Fuß erwischtBellemare, Kröger und van Soest (2008)Umfangreiches Experiment zu Diktatorspielen (N = 511) und<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>en (N = 712)Teilnehmer sind repräsentativ für die holländische BevölkerungEntscheidungssituation Wahl aus 8 Aufteilungen von 10 Euro (kein 50-50)(10, 0), (8.5, 1.5), (7, 3), (5.5, 4.5),(4.5, 5.5), (3, 7), (1.5, 8.5), (0, 10)<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong> Responder kann annehmen oder ablehnen, soll für jedenmöglichen Vorschlag angeben, was er täte (Strategiemethode)Zusätzlich Abfrage der “Beliefs” der Proposer: Mit welchenAnnahme-/Ablehungswahrscheinlichkeiten rechnen Sie?911

MEASURING INEQUITY AVERSION 825Die Angebote: Diktator vs. UltimatumTABLE IIResponderstrategien OBSERVED CHOICE SEQUENCESim FOR RESPONDERS <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>IN THE ULTIMATUM GAME a0 150 300 450 550 700 850 1000 NThreshold Behavior (N = 177)1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 170 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 280 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 300 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 890 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 120 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1FIGURE 1.—Distributions of amounts offered in the ultimatum game and the dictator game.Angebote sind höher im <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong> (stochastische Dominanz)zeigt, dass strategische Gedanken (Vermeidung von Ablehnung) im U-Spielrelevant sind; die Proposer geben dort nicht aus reiner NächstenliebePlateau Behavior (N = 145)0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 200 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 220 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 610 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 60 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 80 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 70 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 20 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 40 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 110 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 10 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 10 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 10 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1Aggregate Acceptance Rates0.05 015 032 093 091 068 058 055a The table columns present the acceptance decision (coded as 1 if accepted) for all 8 possible offers. N denotesthe number of observations. There were 335 responders in the ultimatum game. The responses of 13 participants whoanswered in an inconsistent way are omitted from the table.In beiden Spielen sind die Angebote recht nah an 50-50826 C. BELLEMARE, S. KRÖGER, AND A. VAN SOESTSubjektiv geschätzte Annahmewahrscheinlichkeiten12the frequencies in the final column. Choice sequences were grouped into twocategories. 11 The biggest group (52.8%) was the group of threshold players,whoaccepted any proposal above a certain amount. The second group (43.3%) wasplateau players, who accepted offers in a range excluding both the minimumand maximum amounts that could be offered. The width of the plateau is informativeof the degree of inequity aversion to both one’s own and the otherplayer’s disadvantage, as subjects rejected offers giving them either much loweror much higher amounts than the proposer. Plateau response behavior in theMEASURING INEQUITY AVERSIONultimatum game has been reported by Huck (1999), Güth, Schmidt, and Sutter835(2003), Tracer (2004), Bahry and Wilson (2006), and Hennig-Schmidt, Li, andThreshold (52.8%), Plateau (43.3%, lehnen Angebote zu eigenen Gunsten ab)Angebote der Männer, nach Alter und Bildung1311 A small group (3.9%, 13 responders) exhibited what we call inconsistent behavior, with nosystematic response pattern. A table containing their responses appears in the online appendix.These responses were left out of the empirical analysis. Estimates of the model including themgave very similar results.FIGURE 2.—Proposers’ anticipated acceptance probabilities in the ultimatum game collectedusing the accept and reject framing.Sind immer zu nah an der 50%-Linie (Unsicherheit), Plateaus antizipiertYang (2008). 12 These studies indicated that broad subject pools and the presenceof strong social norms are the most important reasons for nonmonotonicresponse behavior. 13The sizeable fraction of plateau responders had an immediate consequencefor the aggregate acceptance rates, presented at the bottom of Table II. TheMgl. Erklärung: acceptance Loss-Aversion rates increased bzw. from “losses 5% for loom low offers largertothan abovegains”90% for proposals(Gewinn durch aroundAkzeptanz the equal split, vonbut x Euro then declined wirkt kleiner to justals above Verlust 55% when durchthe Ablehnung complete von xEuro man amount erwartet was offered weniger to the Ablehnungen, responder. wenn nach Ablehnung gefragt wird)Figure 2 presents the means of the subjective acceptance probabilities forAccept-Framing (“Mit welcher W-keit wird x akzeptiert”) führt zu geringerensubjektiven W-keiten als Reject-Framing (“Mit welcher W-keit wird x abgelehnt”)14FIGURE 5.—Predicted distributions of amounts offered. Predicted offers by proposers in theultimatum and dictator game for four groups of nonworking men (group 1: 54 years,low educated).Junge, gebildete Männer geben am wenigsten; Alterseffekt größer als Bildungseff.Figure 6 presents the predicted acceptance probabilities of responders in theultimatum game. All subgroups had similar acceptance probabilities of offersbelow 550 CP, in line with the parameter estimates which revealed no signif-15

Anwendung der UngleichheitsaversionTeilspielperfektheit bei NutzenmaximierungEin Strategieprofil ist ein TSP-Ggw, wenn es so gestaltet ist, dass jederSpieler in jedem Teilspiel sein Nutzen maximiert.Diktatorspiel: Man präferiert (8, 2) über (10, 0) wenn8 − α(8 − 2) > 10 − α(10 − 0) ⇔ 4α > 2 ⇔ α > 1/2<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>: Man präferiert (0, 0) über (2, 8) wenn0 − 0 > 2 − β(8 − 2) ⇔ 6β > 2 ⇔ β > 1/3So ist beides kompatibel.Ist diese Nutzenfunktion die einzige, die zu beidem passt? Ganz und garnicht, aber es ist eine sehr einfache.Übliche Parameterverteilung nach Fehr und SchmidtIn einer Population gibt es “üblicherweise” vier verschiedene Typen:Einkommensmaximierer 30%: α = 0, β = 0Schwache U-Aversion 30%: α = 0.25, β = 0.5Mittlere U-Aversion 30%: α = 0.6, β = 1Starke U-Aversion 10%: α = 0.6, β = 4<strong>Das</strong> stimmt natürlich nie genau, bspw. im Diktatorspiel, aber es ist etwas,womit man arbeiten könnte.Stimmt es zumindest ungefähr in allen Spielen, die den Diktator- und<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>en ähneln?Bardsley/List Taking Games: NeinErinnerung: Die passen zu keinem Modell strikter NutzenmaximierungDana et al. Diktatorspiele (“fair aussehen”): NeinOkay, diese Spiele sind auch recht harte Brocken. Passt es denn sonst?2021Engelmann und Strobel (2004): Taxation Games(Steuersatz-Spiele)Diktatorspiele mit drei Spielern: Hier muss man mehr als den eigenenNutzen und die Nutzendifferenz abwägen. Sie sind Spieler 2.TreatmentF E Fx ExA B C A B C A B C A B CSp. 1 8.2 8.8 9.4 9.4 8.4 7.4 17 18 19 21 17 13Sp. 2 5.6 5.6 5.6 6.4 6.4 6.4 10 10 10 12 12 12Sp. 3 4.6 3.6 2.6 2.6 3.2 3.8 9 5 1 3 4 5Verteilung der Entscheidungen (in Prozent)84 10 6 40 23 37 87 6 6 40 17 43Potentielle EntscheidungskriterienU-Avers × × × ×Effizienz × × × ×Es sieht so aus, als würden sich die Leute recht gleichmäßig aufteilen,wenn sie zwischen Gleichheit und Effizienz wählen müssen.Weiter geht’s . . .Engelmann und Strobel (2004): Neid-SpieleSie sind weiter Spieler 2.TreatmentN Nx Ny NyiA B C A B C A B C A B CSp. 1 16 13 10 16 13 10 16 13 10 16 13 10Sp. 2 8 8 8 9 8 7 7 8 9 7.5 8 8.5Sp. 3 5 3 1 5 3 1 5 3 1 5 3 1Verteilung der Entscheidungen (in Prozent)70 27 3 83 13 3 77 13 10 60 17 23Potentielle EntscheidungskriterienU-Avers × × or × × ×Effizienz × × × ×Einer ist immer neidisch – nun dominiert Effizienz. Die Nutzen sindmöglicherweise recht komplizierte Mischungen/Abwägungen zwischenGleichheit und Effizienz.Einmal noch . . .2223

Engelmann und Strobel (2004): Weitere SpieleSie sind weiter Spieler 2.TreatmentR P EyA B C A B C A B CSp. 1 11 8 5 14 11 8 21 17 13Sp. 2 12 12 12 4 4 4 9 9 9Sp. 3 2 3 4 5 6 7 3 4 5Verteilung der Entscheidungen (in Prozent)27 20 53 60 7 33 40 23 27Potentielle EntscheidungskriterienU-Avers × × ×Effizienz × × ×Falk, Fehr und Fischbacher (2003)22 ECONOMIC INQUIRYMini-<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>: Spieler 1 kann nur aus zwei möglichen UltimatenwählenFIGURE 1The Mini-Ultimatum GamesEs kann auch passieren, dass sich die Mehrheit gegenUngleichheitsaversion und Effizienz entscheidet.Selbst eine Mischung der beiden kann nicht alles erklären. Ist es vielleichtetwas ganz anderes?24 ECONOMIC INQUIRYErgebnisse FIGURE 2TABLE 124Rejection Rate of the (8/2)-Offeracross GamesECONOMIC INQUIRYExpected Payoffs for the Proposersfrom Different OffersFIGURE 2Expected ExpectedTABLE payoff Percentage 1Rejection Rate of the (8/2)-Offerpayoff Expected of of thePayoffs alternative for of the(8/2)-Proposersacross Games Game the 8/2-offer fromoffer DifferentproposalsOffers(5/5)-game 4.44 Expected 5.00 Expected31payoff Percentage(2/8)-game 5.87 payoff 1.96 of of the alternative 73 of (8/2)-(10/0)-gameGame7.29the 8/2-offer1.11offer100proposals(5/5)-game 4.44 5.00 31(2/8)-game 5.87 1.96 73the rejection rate from 18% to roughly 45%(10/0)-game 7.29 1.11 100in the (5/5)-game suggests that intentionsdrivenpunishment behavior is a major factor.Thus, ithe seems rejection that reciprocity rate from 18% is actually to roughly 45%driven by both in the outcomes (5/5)-game and intentions. suggests that intentionsdrivenwe takepunishment a look at the behavior proposers’ is a major fac-Finally,(4 subjects) in the (10/0)-game. 7 The nonparametricCochran Q-test confirms that thetor. Thus, the varying it seemsacceptance that reciprocity rate is actuallybehavior. Givenof the (8/2)-offerdifferences in rejection rates across the fourdriven by theboth expected outcomes return andfromintentions.Je günstiger die Alternative für denthis Responder, offer alsogames are significant (p < 0001). It alsoFinally, varied desto we across take weniger games. a lookTable zufrieden at the1proposers’ ist(4 subjects) in the (10/0)-game. 7 The shows non-thaparametric 2) the difference between thebehavior. Given the varying acceptance rateit was least profitable to proposeconfirms er mit (8, that Cochran Q-test confirms that (8/2) the in the (5/5)-game and most profitable in(5/5)-game and the other three games isof the (8/2)-offer the expected return fromdifferences in rejection rates across the the four (10/0)-game. The expected payoff of thestatistically Es geht significant also nicht (p < nur 0001). umPair-wiseAuszahlungen this offer also varied across games. Table 1games are significant (p < 0001). It alternative also offers exhibits the reverse order.comparisons that rejection rateshows that it was least profitable 8to proposeFFF: Scheinbar confirms that interpretieren the difference die between Spieler Thistheindicates u.a. that given the rejection behaviorofisthe responders, the payoff-maximizingin the (5/5)-game is significantly higher than(8/2)diein theIntention(5/5)-gamedes and mostProposersprofitable in(5/5)-game and the other three gamesin (Wählt the (2/8)-game statisticallyer (8,(p 2) = significantaus 017, Freundlichkeit two-sided) (p < 0001). and Pair-wiseoder aus the Egoismus?)(10/0)-game. The expected payoff of thechoice is (5/5) in the (5/5)-game, (8/2) in thethat the difference comparisons between confirm the that (2/8)- theandalternative offers exhibits the reverse order.rejection (2/8)-game, rate8and also (8/2) in the (10/0)-game.the (10/0)-game in the is(5/5)-game also highly is significantly (p =This indicates that given the rejection behaviorof the responders, the payoff-maximizinghigher The than last column in Table 1 shows that the017, two-sided). in the The (2/8)-game difference (p between = 017, two-sided) thevastandmajority of the proposers made indeed(2/8)- and that the (8/2)-game the difference is, however, between onlychoice is (5/5) in the (5/5)-game, (8/2) in thethe (2/8)- theandpayoff-maximizing choice in each game.(weakly) significant if one is willing to apply(2/8)-game, and also (8/2) in the (10/0)-game.9the (10/0)-game is also highly significant Although (p = this proposer behavior is consistentthewith the assumption that the majoritya one-sided017, test two-sided). (p = 068, The one-sided). difference TheThe last column in Table 1 shows that thebetweendifference between (2/8)- and the the (8/2)- (8/2)-game and the (10/0)-vast majority of the proposers made indeedis, however, of only the proposers maximized their expectedgame is clearly not significant (p = 369, two-the payoff-maximizing choice in each game. 9Ablehnungswahrscheinlichkeit von (8, 2) hängt am Wert der Alternative(8, 2) wird auch abgelehnt, wenn die Alternative (8, 2) ist – reine U-AversionÄhnliche Ergebnisse in Brandts and Sola (2001, GEB). Aber . . .2426y is (5/5). This game is therefore called the(5/5)-game. Game (b) is called the (2/8)-gamebecause the alternative offer y is to keep 2points and to give 8 points to R. Note that inthe (2/8)-game P has only the choice betweenan offer that gives P much more than R (i.e.,8/2) and an offer that gives P much less thanR (i.e., 2/8). 4 In game (c) P has in fact noalternative at all, that is, he is forced to pro-Charness und Rabin (2002)the case of an x- and for the case of a y-offer,without knowing what P had proposed. 5At the beginning subjects were randomlyassigned the P or the R role, and they keptthis role in all four games. Subjects faced thegames in a varying order, and in each gamethey played against a different anonymousopponent. They were informed about theoutcome of all four games, that is, about theSehrpose ähnliche the offer (8/2). Spiele We call it(mit the (8/2)-game. den experimentellen choice of their opponents, Ergebnissen only after they had an den Ästen):Finally, in game (d) the alternative offer is made their decision in all games. This procedurenot only avoids income effects but also(10/0), hence it is termed the (10/0)-game.To get sufficient data we employed the strategymethod, that is, responders had torules out that subjects’ behavior is influencedspec-Pl. 2Pl. by 1 previous decisions of their opponents. Pl. 1ify complete strategies in the game-theoreticsense. Thus, every responder hadOut to : indicate 41% 5. In In: principle, 59% it is possible that the strategy Out : 73% methodhis action at both decision nodes, that is, for induces different responder behavior relative to a situationwhere Pl. responders 2 have to decide whether 7.5, to7.5 acceptL : 100% R : 0%5, 54. The payoff structure of this game is similar to the a given, known, offer. However, Brandts and CharnessIn : 27%Pl. 2so-called best-shot game, which was first studied by Harrisonand Hirshleifer (1989) and subsequently by Pras-L : 91% cating that the strategy R : 9% method does not induce differentL : 88% (2000) and Cason and Mui (1998) report evidence indinikarR : 12%and Roth (1992).behaviors.8, 2 0, 08, 2 0, 08, 2 0, 0Mit ganz anderen Ergebnissen(8, 2) wird nur sehr selten abgelehntselbst neben der (7.5., 7.5), wo dieser Vorschlag besonders egoistisch wirktWert der Alternative spielt fast keine RolleOhne Alternative (Spiel ganz links) verschwindet die Ungleichheitsaversion!Einziger methodischer Unterschied zu FFF: dort waren die Rollenvorgegeben, hier (CR) wurden sie erst nach der Entscheidung ausgelostWie soll man die Unterschiede zu FFF (45% Ablehnung von (2, 8)) undzum Standard-<strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong> (75% Ablehnung von (2, 8)) erklären?2527

Bereby-Meyer und Niederle (2005)Drei-Spieler <strong>Ultimatumspiel</strong>, Spieler 1 macht den Vorschlag zur Aufteilungvon 10 Dollar, Spieler 2 kann annehmen oder akzeptieren, Spieler 3 kannnur zuschauen, bekommt vielleicht jedoch etwas ab.Ergebnisse180 Y. Bereby-Meyer, M. Niederle / J. of Economic Behavior & Org. 56 (2005) 173–186TRP Spieler 1 schlägt Aufteilung zwischen sich und 2 vor, bei Ablehnung erhältSpieler 3 eine Auszahlung von 10, 5 oder 0 Dollar (je nach Treatment).PRP Spieler 1 schlägt Aufteilung zwischen 2 und 3 vor, bei Ablehnung erhält erselbst (1) eine Auszahlung von 10, 5 oder 0 Dollar (je nach Treatment).178 Y. Bereby-Meyer, M. Niederle / J. of Economic Behavior & Org. 56 (2005) 173–186Table 1Possible payoff distributions after a 10 − x proposal for the TRP-$10 and PRP-$10TRPPRPAccept Reject Accept RejectProposer x 0 0 10Responder 10 − x 0 10 − x 0Third party 0 10 x 0distributions. Consider the TRP game where the third party receives the rejection payoff. Ifthe responder accepts the offer, then the payoffs are (x,10 − x,0) for (proposer, responder,third party); if she rejects the offer, the payoffs are (0,0,10). In the PRP games where theproposer receives the rejection payoff, the responder decides between (0,10 − x,x) in caseof acceptance and (10,0,0) in case of rejection.Referenzabhängiger Outcome based models of difference Altruismusaversion such as of Fehr and Schmidt (1999) andBolton and Ockenfels (2000) make further predictions depending on the size of the rejectionIdee: Personen haben Erwartungen an die Interaktion, sind zufrieden (altruistisch)payoff.wenn Thedie utility Erwartungen function oferfüllt Fehr and werden, Schmidt unzufrieden involves a(missgünstig) comparison of sonst the subjects’ ownpayoff x i to the payoff of all the other subjects, where subjects have a stronger distaste forDie “Erwartung” (Referenzpunkt) betrifft das erwartete Einkommentheir payoff falling behind than being ahead. Specifically,Absoluter Referenzpunkt 1 ∑π a : Erwartete Auszahlung 1 ∑ bei “normalem” VerlaufU i (x) = x i − { α i max{x j − x i , 0}−β i max{x i − x j , 0}22j≠ij≠iu a πi + α · π(π i , π j ) =j , falls π i ≥ π aπwhere β i ≤ α i ,0≤ β i + β · πi ≤ 1 and j , falls πα weighs the i < πdisadvantageous aand β the advantageousMit inequality. α > β hat das den beschriebenen Effekt.Bolton and Ockenfels (2000) have players (∑who compare ) how their payoff relates to theRelativer average payoff: Referenzpunkt: U i (x)=v i (x i Gegnerische , σ i ) where σ i Auszahlung xj ,x i equalsxi / ∑ x j if ∑ x j > 0 and 1/notherwise. They also{ assume that v i is increasing and concave in x i , v i2 =0σ i =1/n and v i22 accept β. Derall Unterschied proposals, the zureason Fehr-Schmidt-Ungleichheitsaversion being that the difference between 0ist,anddass 10 isdiese alwaysNutzenfunktionen larger than the difference unstetig between am Referenzpunkt 10 − x and x. For sind. a rejection payoff of $5,Bolton and Ockenfels (2000) predict no rejection since a share of 0 is less than (10 − x)/10,Diese 1