World Journal of Diabetes (World J Diabetes

World Journal of Diabetes (World J Diabetes

World Journal of Diabetes (World J Diabetes

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011 January 15; 2(1): 1-18<br />

P/D1 cells <strong>of</strong> fundus <strong>of</strong> the stomach Epsilon cells <strong>of</strong> the pancreas Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus<br />

Vagal afferent endings<br />

Ghrelin<br />

Leukocytes, Macrophages,<br />

T and B cells Cardiovascular system Respiratory system CNS<br />

↓ Immune response<br />

↓ TNF, IL-6, HMGB1<br />

↓ Inflammation and sepsis<br />

Akt/eNOS<br />

↓ Ischemia/reperfusion<br />

injury Atherosclerosis<br />

www.wjgnet.com<br />

↓ Immune response<br />

↓ TNF, IL-6, HMGB1<br />

↓ Sepsis-induced lung injury<br />

ISSN 1948-9358 (online)<br />

GH, Corticosteroids,<br />

dopamine, insulin,<br />

leptin, etc .<br />

↑ Appetite<br />

↓ Depression<br />

↑Learning<br />

and memory

Contents<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

ORIGINAL ARTICLES<br />

DREAM 2020<br />

1 Relationship between gut and sepsis: Role <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

Das UN<br />

8 Excessive 5-year weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome development in<br />

healthy middle-aged adults<br />

Lin YC, Chen JD, Chen PC<br />

16 Continuous positive airway pressure to improve insulin resistance and glucose<br />

homeostasis in sleep apnea<br />

Steiropoulos P, Papanas N<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com I<br />

Monthly Volume 2 Number 1 January 15, 2011<br />

January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Contents<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

APPENDIX<br />

ABOUT COVER<br />

AIM AND SCOPE<br />

FLYLEAF<br />

EDITORS FOR<br />

THIS ISSUE<br />

NAME OF JOURNAL<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

LAUNCH DATE<br />

March 15, 2010<br />

SPONSOR<br />

Beijing Baishideng BioMed Scientific Co., Ltd.,<br />

Room 903, Building D, Ocean International Center,<br />

No. 62 Dongsihuan Zhonglu, Chaoyang District,<br />

Beijing 100025, China<br />

Telephone: 0086-10-8538-1892<br />

Fax: 0086-10-8538-1893<br />

E-mail: baishideng@wjgnet.com<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com<br />

EDITING<br />

Editorial Board <strong>of</strong> <strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong>,<br />

Room 903, Building D, Ocean International Center,<br />

No. 62 Dongsihuan Zhonglu, Chaoyang District,<br />

Beijing 100025, China<br />

Telephone: 0086-10-5908-0038<br />

Fax: 0086-10-8538-1893<br />

E-mail: wjd@wjgnet.com<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com<br />

PUBLISHING<br />

Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited,<br />

Room 1701, 17/F, Henan Building,<br />

No.90 Jaffe Road, Wanchai,<br />

Hong Kong, China<br />

Fax: 00852-3115-8812<br />

Telephone: 00852-5804-2046<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

Volume 2 Number 1 January 15, 2011<br />

I Acknowledgments to reviewers <strong>of</strong> <strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

I Meetings<br />

I-V Instructions to authors<br />

Das UN. Relationship between gut and sepsis: Role <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011; 2(1): 1-8<br />

http://www.wjnet.com/1948-9358/full/v2/i1/1.htm<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong> (<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong>, WJD, online ISSN 1948-9358, DOI: 10.4239),<br />

is a monthly, open-access, peer-reviewed journal supported by an editorial board <strong>of</strong> 323<br />

experts in diabetes mellitus research from 38 countries.<br />

The major task <strong>of</strong> WJD is to report rapidly the most recent results in basic and<br />

clinical research on diabetes including: metabolic syndrome, functions <strong>of</strong> α, β, δ and<br />

PP cells <strong>of</strong> the pancreatic islets, effect <strong>of</strong> insulin and insulin resistance, pancreatic islet<br />

transplantation, adipose cells and obesity, clinical trials, clinical diagnosis and treatment,<br />

rehabilitation, nursing and prevention. This covers epidemiology, etiology, immunology,<br />

pathology, genetics, genomics, proteomics, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacogenetics,<br />

diagnosis and therapeutics. Reports on new techniques for treating diabetes<br />

are also welcome.<br />

I-III Editorial Board<br />

Responsible Assistant Editor: Na Liu Responsible Science Editor: Hai-Ning Zhang<br />

Responsible Electronic Editor: Na Liu Pro<strong>of</strong>ing Editorial Office Director: Hai-Ning Zhang<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>ing Editor-in-Chief: Lian-Sheng Ma<br />

E-mail: baishideng@wjgnet.com<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com<br />

SUBSCRIPTION<br />

Beijing Baishideng BioMed Scientific Co., Ltd.,<br />

Room 903, Building D, Ocean International Center,<br />

No. 62 Dongsihuan Zhonglu, Chaoyang District,<br />

Beijing 100025, China<br />

Telephone: 0086-10-8538-1892<br />

Fax: 0086-10-8538-1893<br />

E-mail: baishideng@wjgnet.com<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com<br />

ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION<br />

One-Year Price 216.00 USD<br />

PUBLICATION DATE<br />

January 15, 2011<br />

CSSN<br />

ISSN 1948-9358 (online)<br />

PRESIDENT AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF<br />

Lian-Sheng Ma, Beijing<br />

STRATEGY ASSOCIATE EDITORS-IN-CHIEF<br />

Undurti Narasimha Das, Ohio<br />

Min Du, Wyoming<br />

Gregory I Liou, Georgia<br />

Zhong-Cheng Luo, Quebec<br />

Demosthenes B Panagiotakos, Athens<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com II<br />

EDITORIAL OFFICE<br />

Hai-Ning Zhang, Director<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

Room 903, Building D, Ocean International Center,<br />

No. 62 Dongsihuan Zhonglu, Chaoyang District,<br />

Beijing 100025, China<br />

Telephone: 0086-10-5908-0038<br />

Fax: 0086-10-8538-1893<br />

E-mail: wjd@wjgnet.com<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com<br />

COPYRIGHT<br />

© 2011 Baishideng. All rights reserved; no part <strong>of</strong> this<br />

publication may be commercially reproduced, stored<br />

in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or<br />

by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,<br />

recording, or otherwise without the prior permission<br />

<strong>of</strong> Baishideng. Authors are required to grant <strong>World</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Diabetes</strong> an exclusive license to publish.<br />

SPECIAL STATEMENT<br />

All articles published in this journal represent the<br />

viewpoints <strong>of</strong> the authors except where indicated<br />

otherwise.<br />

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS<br />

Full instructions are available online at http://www.<br />

wjgnet.com/1948-9358/g_info_20100107165233.<br />

htm. If you do not have web access please contact<br />

the editorial <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

ONLINE SUBMISSION<br />

http://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358<strong>of</strong>fice<br />

January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Online Submissions: http://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358<strong>of</strong>fice<br />

wjd@wjgnet.com<br />

doi:10.4239/wjd.v2.i1.1<br />

Relationship between gut and sepsis: Role <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

Undurti N Das<br />

Undurti N Das, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Kakinada<br />

533003, India<br />

Undurti N Das, UND Life Sciences, Shaker Heights, OH 44120,<br />

United States<br />

Author contribution: Das UN contributed solely to this paper.<br />

Correspondence to: Undurti N Das, MD, FAMS, Jawaharlal<br />

Nehru Technological University, Kakinada 533003,<br />

India. Undurti@hotmail.com<br />

Telephone: +912162315548 Fax: +919288330316<br />

Received: September 19, 2010 Revised: December 22, 2010<br />

Accepted: December 29, 2010<br />

Published online: January 15, 2011<br />

Abstract<br />

Ghrelin is a growth hormone secretagogue produced<br />

by the gut, and is expressed in the hypothalamus<br />

and other tissues as well. Ghrelin not only plays an<br />

important role in the regulation <strong>of</strong> appetite, energy balance<br />

and glucose homeostasis, but also shows antibacterial<br />

activity, suppresses proinflammatory cytokine<br />

production and restores gut barrier function. In<br />

experimental animals, ghrelin has shown significant<br />

beneficial actions in preventing mortality from sepsis.<br />

In the critically ill, corticosteroid insufficiency as a result<br />

<strong>of</strong> dysfunction <strong>of</strong> the hypothalamicpituitaryadrenal<br />

axis is known to occur. It is therefore possible that both<br />

gut and hypothalamus play an important role in the<br />

pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> sepsis by virtue <strong>of</strong> their ability to produce<br />

ghrelin, which, in turn, could be a protective phenomenon<br />

to suppress inflammation. It remains to be<br />

seen whether ghrelin and its analogues are <strong>of</strong> benefit in<br />

treating patients with sepsis.<br />

© 2011 Baishideng. All rights reserved.<br />

Key words: Ghrelin; Sepsis; Cytokines; Inflammation;<br />

Critically ill; Insulin<br />

Peer reviewers: Vladimir N Uversky, Senior Research Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,<br />

Center for Computational Biology & Bioinformatics,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Indiana<br />

University School <strong>of</strong> Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, United<br />

States; Joseph Fomusi Ndisang, PharmD, PhD, Assistant Pro<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011 January 15; 2(1): 1-7<br />

ISSN 1948-9358 (online)<br />

© 2011 Baishideng. All rights reserved.<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

fessor, College <strong>of</strong> Medicine, Epartment <strong>of</strong> Physiology, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Saskatchewan, 107 Wiggins Road, Saskatoon, SK, Canada<br />

Das UN. Relationship between gut and sepsis: Role <strong>of</strong> ghrelin.<br />

<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011; 2(1): 17 Available from: URL: http://<br />

www.wjgnet.com/19489358/full/v2/i1/1.htm DOI: http://dx.doi.<br />

org/10.4239/wjd.v2.i1.1<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Ghrelin, a peptide hormone that serves as the endogenous<br />

ligand <strong>of</strong> the growth hormone secretagogue receptor,<br />

is secreted mainly by P/D1 cells lining the fundus <strong>of</strong><br />

the human stomach, and the epsilon cells <strong>of</strong> the pancreas<br />

that stimulate hunger [1] . Ghrelin is also secreted from the<br />

small intestine and the colon. It is expressed in the hypothalamus,<br />

pituitary, and several peripheral tissues suggesting<br />

that it could have diverse physiological functions [25] .<br />

Ghrelin regulates growth hormone secretion, and plays an<br />

important role in the regulation <strong>of</strong> appetite, energy balance<br />

and glucose homeostasis. It regulates gastrointestinal,<br />

cardiovascular, and immune functions, and bone physiology<br />

[612] . Ghrelin levels increase before meals, decrease<br />

after meals, and serve as the counterpart <strong>of</strong> leptin, which<br />

induces satiation when present at higher levels. Bariatric<br />

procedures lead to a reduction in the amount <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

produced, which causes the satiation that could explain<br />

the weight loss occurring after gastric bypass surgery.<br />

Receptors for ghrelin are expressed by the neurons in the<br />

arcuate nucleus and the ventromedial hypothalamus [13] that<br />

have a regulatory role in insulin secretion and participate<br />

in the pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> type 2 diabetes mellitus, thus<br />

implying that ghrelin has a role in insulin resistance. The<br />

ghrelin receptor is a G proteincoupled receptor. Ghrelin<br />

is essential for cognitive adaptation to changing environments<br />

and the process <strong>of</strong> learning [14] , and activates endothelial<br />

nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [15,16] . Obestatin, which<br />

is derived from the same gene as ghrelin, has opposite ac<br />

tions to that <strong>of</strong> ghrelin on energy homeostasis and gastroin<br />

testinal function, thus adding complexity to the role <strong>of</strong> ghre<br />

lin in various physiological and pathological situations [17] .<br />

1 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

positive result <strong>of</strong> intensive insulin therapy on the critically<br />

ill could be attributed to the prevention <strong>of</strong> sepsis, multiple<br />

organ failure and need for prolonged invasive organ<br />

support and intensive care. These results suggest that reduced<br />

stimulation <strong>of</strong> pituitary function seen in prolonged<br />

critically ill patients needs to be corrected to reverse the<br />

paradoxical ‘wasting syndrome’, and that maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

strict normoglycemia with insulin is important to increase<br />

the chances <strong>of</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> these patients. It is now believed<br />

that, from an endocrinological point <strong>of</strong> view, the<br />

acute phase and the later phase <strong>of</strong> critical illness manifest<br />

themselves differently. When the disease process becomes<br />

prolonged, there is a uniformlyreduced pulsatile secretion<br />

<strong>of</strong> anterior pituitary hormones, with proportionally<br />

reduced concentrations <strong>of</strong> peripheral anabolic hormones.<br />

During critical illness, prolonged activation <strong>of</strong> the HPA<br />

axis can result in hypercortisolemia and hypocortisolemia;<br />

both can be detrimental to recovery from critical illness.<br />

Recognition <strong>of</strong> adrenal dysfunction in critically ill patients<br />

is difficult because a reliable history is not available, and<br />

laboratory results are difficult to interpret [43,44] . For instance,<br />

the acute phase <strong>of</strong> critical illness is characterized<br />

by an actively secreting pituitary, but the concentrations <strong>of</strong><br />

most peripheral effector hormones are low, partly due to<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> targetorgan resistance. In contrast,<br />

in prolonged critical illness, predominantly hypothalamic<br />

suppression <strong>of</strong> the (neuro)endocrine axes occurs, leading<br />

to the low serum levels <strong>of</strong> the respective targetorgan hormones.<br />

The adaptations in the acute phase are considered<br />

to be beneficial for shortterm survival. In the chronic<br />

phase, however, the observed (neuro)endocrine alterations<br />

contribute to the general wasting syndrome. With<br />

the exception <strong>of</strong> intensive insulin therapy, and perhaps<br />

hydrocortisone administration for a subgroup <strong>of</strong> patients,<br />

no hormonal intervention has proven to affect outcome<br />

beneficially [45] . In this context, the recently described beneficial<br />

actions <strong>of</strong> ghrelin in the critically ill may have important<br />

clinical implications.<br />

GHRELIN IN SEPSIS<br />

Experimental studies<br />

In the rat model <strong>of</strong> septic shock which was made by<br />

caecal ligation and perforation, infusion <strong>of</strong> ghrelin 10<br />

nmol/kg at the time <strong>of</strong> operation through the femoral<br />

vein, followed by a sc (subcutaneous) injection at 8 h after<br />

operation, revealed that, compared to that <strong>of</strong> the septic<br />

shock group, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) <strong>of</strong> rats<br />

in the ghrelintreated group increased by 33 % (P < 0.01);<br />

the values <strong>of</strong> +LVdp/dtmax and LVdp/dtmax increased<br />

by 27 % and 33 %, respectively (P < 0.01), but LVEDP<br />

decreased by 33 % (P < 0.01). The plasma glucose concentration<br />

and myocardial ATP content increased by<br />

53% and 22 %, respectively, whereas plasma lactate concentration<br />

decreased by 40% in the ghrelintreated rats (P<br />

< 0.01). The plasma ghrelin level in rats with septic shock<br />

was 51% higher than that <strong>of</strong> rats in the sham group,<br />

and was negatively correlated with MABP and blood<br />

glucose concentration (r = 0.721 and 0.811, respectively,<br />

P < 0.01). The mortality rates were 47% (9/19) in rats<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Das UN. Ghrelin and sepsis<br />

with septic shock and 25% (3/12) in rats <strong>of</strong> the ghrelintreated<br />

group, respectively, suggesting that treatment with<br />

ghrelin could at least partially correct the abnormalities <strong>of</strong><br />

hemodynamics and metabolic disturbance in septic shock<br />

<strong>of</strong> rats [46] .<br />

In an extension <strong>of</strong> these studies, it was noted that<br />

even endotoxininduced shock and mortality could be<br />

significantly decreased by ghrelin treatment in rats [47] .<br />

Early and late (12 h after lipopolysaccharide injection)<br />

treatment with ghrelin markedly increased the plasma<br />

glucose concentration, and decreased the plasma lactate<br />

concentration. This action on the part <strong>of</strong> ghrelin in increasing<br />

plasma glucose levels (resulting in hyperglycemia)<br />

may suggest that it could be harmful in the setting <strong>of</strong><br />

sepsis or critical illness, since hyperglycemia is believed to<br />

accentuate inflammation. In the initial stages <strong>of</strong> sepsis,<br />

hyperglycemia (reactive hyperglycemia) as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

the enhanced production <strong>of</strong> hypercortisolemia occurs,<br />

whereas in the later stages, hypoglycemia sets in, partly<br />

due to hypocortisolemia [48,49] . It was reported that during<br />

the early phase <strong>of</strong> sepsis, plasma glucose levels increased,<br />

whereas plasma insulin and glucagon levels remained<br />

unchanged, but corticosterone levels increased 2.5fold<br />

over control values. At later stages <strong>of</strong> sepsis, plasma<br />

glucose levels returned to normal, whereas insulin, glucagon,<br />

and corticosterone levels increased significantly i.e.<br />

40fold, 6.5fold, and 6fold respectively [48,49] . Therefore,<br />

the initial rise and subsequent decline in blood glucose<br />

correlated well with a corticosterone followed by an insulindependent<br />

phenomenon. Thus, blood glucose levels<br />

in sepsis depend to a large extent on the balance between<br />

corticosterone and insulin levels, and the stage <strong>of</strong> sepsis [49] .<br />

Hence, the ability <strong>of</strong> ghrelin to enhance plasma glucose<br />

levels could, especially in the later stages <strong>of</strong> sepsis, prevent<br />

hypoglycemia that is detrimental and ghrelin may therefore<br />

be useful in later stages <strong>of</strong> sepsis. Furthermore, ghrelin<br />

and insulin seem to have both positive and negative feedback<br />

control over each other [5052] , suggesting that ghrelin<br />

may be involved in maintaining glucose homeostasis,<br />

under both normal conditions and sepsis.<br />

Early treatment with ghrelin significantly attenuated<br />

the deficiency in myocardial ATP content, but late treatment<br />

with ghrelin had no effect on myocardial ATP content.<br />

The plasma ghrelin level was significantly increased<br />

in the rats with endotoxin shock, and it increased further<br />

after ghrelin administration. Exposure <strong>of</strong> rat gastric mucosa<br />

in vitro to lipopolysaccharide (1.0 to 100 µg/mL) triggered<br />

the release <strong>of</strong> ghrelin from mucosa tissue in a dose<br />

and timedependent manner [47] . These results suggest that<br />

lipopolysaccharide directly stimulates gastric mucosa to<br />

synthesize and secrete ghrelin, that may result in a decrease<br />

in endotoxininduced target organ damage.<br />

Ghrelin suppresses production <strong>of</strong> pro-inflammatory<br />

cytokines<br />

Ghrelin-inhibited proinflammatory cytokine production,<br />

mononuclear cell binding, and nuclear factorkappaB<br />

activation in human endothelial cells in vitro, and endotoxininduced<br />

cytokine production in vivo, by interacting<br />

with growth hormone secretagogue receptors and thus,<br />

3 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Das UN. Ghrelin and sepsis<br />

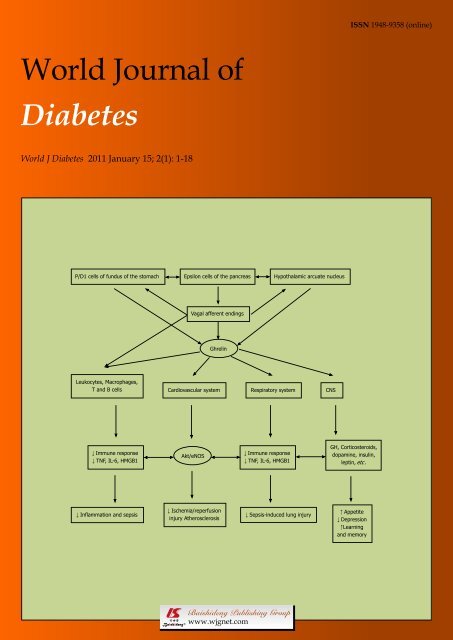

P/D1 cells <strong>of</strong> fundus <strong>of</strong> the stomach Epsilon cells <strong>of</strong> the pancreas Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus<br />

ghrelin behaves as an endogenous anti-inflammatory mo-<br />

lecule [53] . These anti-inflammatory actions <strong>of</strong> ghrelin may<br />

explain why it is able to improve cachexia in heart fai<br />

lure and cancer, and to ameliorate the hemodynamic and<br />

metabolic disturbances in septic shock (Figure 1). By<br />

virtue <strong>of</strong> its anti-inflammatory action, ghrelin could play<br />

a modulatory role in atherosclerosis as well, especially in<br />

obese patients, in whom ghrelin levels are reduced. In a rat<br />

model <strong>of</strong> polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation<br />

and puncture, though ghrelin levels decreased at early (at<br />

5 h after ligation and puncture) or late sepsis (20 h after<br />

ligation and cecal puncture) its receptor was markedly<br />

elevated in early sepsis. Moreover, ghrelininduced relaxation<br />

in resistance blood vessels <strong>of</strong> the isolated small<br />

intestine increased significantly during early sepsis, but<br />

was not altered in late sepsis. GHSR1a expression in<br />

smooth muscle cells was significantly increased at mRNA<br />

and protein levels with stimulation by LPS at 10 ng/mL,<br />

suggesting that GHSR1a expression is upregulated, and<br />

vascular sensitivity to ghrelin stimulation is increased in<br />

the hyperdynamic phase <strong>of</strong> sepsis [54] as a compensatory<br />

phenomenon to septic process. Furthermore, ghrelin improved<br />

tissue perfusion in severe sepsis by downregulating<br />

endothelin1 involving a NFkappaBdependent pathway<br />

[55] .<br />

These experimental results are supported by the report<br />

that during postoperative intraabdominal sepsis seen in<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Vagal afferent endings<br />

Ghrelin<br />

Leukocytes, Macrophages,<br />

T and B cells Cardiovascular system Respiratory system CNS<br />

↓ Immune response<br />

↓ TNF, IL6, HMGB1<br />

↓ Inflammation and sepsis<br />

Akt/eNOS<br />

↓ Ischemia/reperfusion<br />

injury Atherosclerosis<br />

↓ Immune response<br />

↓ TNF, IL6, HMGB1<br />

↓ Sepsisinduced lung injury<br />

GH, Corticosteroids,<br />

dopamine, insulin,<br />

leptin, etc .<br />

↑ Appetite<br />

↓ Depression<br />

↑Learning<br />

and memory<br />

Figure 1 Scheme showing various actions <strong>of</strong> ghrelin and their possible clinical importance. Ghrelin seems to be <strong>of</strong> benefit in suppressing inflammation and<br />

sepsis; protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial damage; protects lungs from sepsis-induced damage, enhances appetite, relieves depression and<br />

enhances learning and memory. GH: growth hormone; CNS: central nervous system.<br />

patients, both ghrelin and leptin plasma levels were elevated<br />

and positively correlated with both inflammatory cytokines<br />

(TNFα, IL-6) and CRP. However, this hormonal<br />

reaction does not seem to be specific to sepsis since a significant<br />

increase in both ghrelin and leptin was observed<br />

to occur during an uncomplicated postoperative response,<br />

although to a lesser extent than was shown in sepsis [56] .<br />

Ghrelin stimulates vagus nerve<br />

Ghrelin stimulates the vagus nerve. Since plasma levels <strong>of</strong><br />

ghrelin were significantly reduced in sepsis; and ghrelin<br />

administration improved organ perfusion and function, it<br />

was hypothesized that ghrelin decreases pro-inflammatory<br />

cytokines in sepsis by means <strong>of</strong> activation <strong>of</strong> the vagus<br />

nerve. This is so since the vagus mediator, acetylcholine,<br />

has potent antiinflammatory actions and suppresses<br />

TNFα, IL6 and HMGB1 production by stimulating the<br />

alpha7 subunitcontaining nicotinic acetylcholine receptor<br />

(alpha7nAChR) [57,58] . As predicted, experimental studies revealed<br />

that vagotomy prevented ghrelin’s downregulatory<br />

effect on TNFα and IL-6 production, thus confirming<br />

that ghrelin downregulates proinflammatory cytokines<br />

in sepsis through activation <strong>of</strong> the vagus nerve [59] . It was<br />

reported that ghrelin has sympathoinhibitory properties<br />

that are mediated by central ghrelin receptors, involving<br />

a NPY/Y1 receptordependent pathway [60] . Ghrelin also<br />

inhibited the production <strong>of</strong> HMGB1 by activated macro<br />

4 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Ghrelin<br />

Gut<br />

Disruption<br />

<strong>of</strong> gut<br />

barrier<br />

function<br />

phages, and also showed antibacterial activity [61] that may<br />

explain its beneficial action in sepsis and other inflammatory<br />

conditions [6264] . It is important to note that ghrelin<br />

ameliorated gut barrier dysfunction [65] , an abnormality that<br />

is seen in patients with sepsis.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Absorption<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

endotoxin<br />

CRH, ACTH,<br />

corticosterone<br />

Melanocortins<br />

It is evident from the preceding discussion that ghrelin<br />

has anti-inflammatory, para-sympathetic stimulatory and<br />

sympathoinhibitory effects that may underlie its beneficial<br />

actions in sepsis and other inflammatory conditions.<br />

In addition, ghrelin seems to be <strong>of</strong> significant benefit<br />

in improving cachexia in heart failure and cancer, and<br />

the ameliorization <strong>of</strong> the hemodynamic and metabolic<br />

disturbances in septic shock (Figure 1). The ability <strong>of</strong><br />

ghrelin to suppress the synthesis and release <strong>of</strong> proinflammatory<br />

cytokines such as TNF-α, IL6 and HMGB1<br />

suggests that it may find its use in the management <strong>of</strong><br />

other inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis,<br />

lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, but this remains to be<br />

determined. The fact that ghrelin is capable <strong>of</strong> restoring<br />

gut barrier function and possess antimicrobial action suggests<br />

that it may be useful in the management <strong>of</strong> cirrhosis<br />

<strong>of</strong> the liver where gut barrier function is compromised,<br />

leading to endotoxin absorption into the circulation. Since<br />

failure <strong>of</strong> gut barrier function is also one <strong>of</strong> the initial<br />

abnormalities seen in sepsis, ghrelin is eminently suited<br />

to be employed in its therapy, either by itself, or in combination<br />

with other therapies. These actions <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Infection/Injury/Surgery<br />

Activation <strong>of</strong> neutrophils,<br />

T cells and macrophages<br />

Elimination <strong>of</strong> invading pathogens<br />

Excess TNFα, IL6, MIF,<br />

HMGB1<br />

Excess free radicals,<br />

eicosanoids and nitric oxide<br />

Hypoglycemia, hypotension and<br />

decreased tissue perfusion<br />

Sepsis and septic shock<br />

Stimulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> gut<br />

Ghrelin<br />

Das UN. Ghrelin and sepsis<br />

↑ Vagal nerve<br />

stimulation and<br />

acetylcholine<br />

release<br />

Figure 2 Scheme showing the actions <strong>of</strong> ghrelin that are relevant to its potential benefit in sepsis. CRH: corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH:<br />

adrenocorticotropic hormone.<br />

suggest that ghrelin has the potential to be <strong>of</strong> significant<br />

benefit in sepsis and other critically ill patients (Figure<br />

2). Obviously, large scale human studies are need before<br />

ghrelin comes into the clinic in the management <strong>of</strong> sepsis.<br />

Ghrelin has been shown to have the ability to alter<br />

nerve cell connections and synaptic plasticity [66,67] in the<br />

melanocortin system, implying that ghrelin regulates me<br />

tabolic control by a central action. Melanocortins are kno<br />

wn to have anti-inflammatory actions [68,69] suggesting that<br />

modulation <strong>of</strong> the melanocortin system could be yet another<br />

means by which ghrelin could bring about its anti<br />

inflammatory action. It has, in fact, been reported that<br />

ghrelin inhibited POMC neurons [70] , and stimulated the<br />

hypothalamopituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in<br />

the release <strong>of</strong> corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH),<br />

adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and corticosterone,<br />

suggesting a hypothalamic site <strong>of</strong> action [71] . Thus,<br />

ghrelin could be producing its anti-inflammatory actions<br />

by inducing the release <strong>of</strong> CRH, ACTH and corticosterone.<br />

Ghrelin might also help prevent the stressinduced<br />

depression and anxiety [72,73] that is common in patients<br />

with sepsis and the critically ill. Ghrelin may thus be <strong>of</strong><br />

significant benefit in the management <strong>of</strong> sepsis and the<br />

critically ill, provided that clinical trials confirm the anticipated<br />

benefits.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Dr UN Das was in receipt <strong>of</strong> the Ramalingaswami Fellow-<br />

5 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Das UN. Ghrelin and sepsis<br />

ship <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Biotechnology, India, during<br />

the tenure <strong>of</strong> this study.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1 Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa<br />

K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide<br />

from stomach. Nature 1999; 402: 656-660<br />

2 Sato T, Fukue Y, Teranishi H, Yoshida Y, Kojima M. Molecular<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> hypothalamic ghrelin and its regulation by<br />

fasting and 2-deoxy-d-glucose administration. Endocrinology<br />

2005; 146: 2510-2516<br />

3 Iglesias MJ, Piñeiro R, Blanco M, Gallego R, Diéguez C,<br />

Gualillo O, González-Juanatey JR, Lago F. Growth hormone<br />

releasing peptide (ghrelin) is synthesized and secreted by<br />

cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2004; 62: 481-488<br />

4 Volante M, Allìa E, Gugliotta P, Funaro A, Broglio F, Deghenghi<br />

R, Muccioli G, Ghigo E, Papotti M. Expression <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

and <strong>of</strong> the GH secretagogue receptor by pancreatic islet<br />

cells and related endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab<br />

2002; 87: 1300-1308<br />

5 Ueberberg B, Unger N, Saeger W, Mann K, Petersenn S. Expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> ghrelin and its receptor in human tissues. Horm<br />

Metab Res 2009; 41: 814-821<br />

6 Wang DH, Hu YS, Du JJ, Hu YY, Zhong WD, Qin WJ. Ghrelin<br />

stimulates proliferation <strong>of</strong> human osteoblastic TE85 cells<br />

via NO/cGMP signaling pathway. Endocrine 2009; 35: 112-117<br />

7 Tesauro M, Schinzari F, Caramanti M, Lauro R, Cardillo C.<br />

Metabolic and cardiovascular effects <strong>of</strong> ghrelin. Int J Pept<br />

2010; 2010: 864342<br />

8 Zhang GG, Teng X, Liu Y, Cai Y, Zhou YB, Duan XH, Song<br />

JQ, Shi Y, Tang CS, Yin XH, Qi YF. Inhibition <strong>of</strong> endoplasm<br />

reticulum stress by ghrelin protects against ischemia/reperfusion<br />

injury in rat heart. Peptides 2009; 30: 1109-1116<br />

9 Schwenke DO, Tokudome T, Kishimoto I, Horio T, Shirai<br />

M, Cragg PA, Kangawa K. Early ghrelin treatment after<br />

myocardial infarction prevents an increase in cardiac sympathetic<br />

tone and reduces mortality. Endocrinology 2008; 149:<br />

5172-5176<br />

10 Himmerich H, Sheldrick AJ. TNF-alpha and ghrelin: opposite<br />

effects on immune system, metabolism and mental health.<br />

Protein Pept Lett 2010; 17: 186-196<br />

11 Dixit VD, Yang H, Cooper-Jenkins A, Giri BB, Patel K, Taub<br />

DD. Reduction <strong>of</strong> T cell-derived ghrelin enhances proinflammatory<br />

cytokine expression: implications for age-associated<br />

increases in inflammation. Blood 2009; 113: 5202-5205<br />

12 Hattori N. Expression, regulation and biological actions <strong>of</strong><br />

growth hormone (GH) and ghrelin in the immune system.<br />

Growth Horm IGF Res 2009; 19: 187-197<br />

13 Mondal MS, Date Y, Yamaguchi H, Toshinai K, Tsuruta T,<br />

Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Identification <strong>of</strong> ghrelin and its<br />

receptor in neurons <strong>of</strong> the rat arcuate nucleus. Regul Pept<br />

2005; 126: 55-59<br />

14 Atcha Z, Chen WS, Ong AB, Wong FK, Neo A, Browne ER,<br />

Witherington J, Pemberton DJ. Cognitive enhancing effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> ghrelin receptor agonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;<br />

206: 415-427<br />

15 Xu X, Jhun BS, Ha CH, Jin ZG. Molecular mechanisms <strong>of</strong><br />

ghrelin-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation.<br />

Endocrinology 2008; 149: 4183-4192<br />

16 Shimizu Y, Nagaya N, Teranishi Y, Imazu M, Yamamoto H,<br />

Shokawa T, Kangawa K, Kohno N, Yoshizumi M. Ghrelin<br />

improves endothelial dysfunction through growth hormoneindependent<br />

mechanisms in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun<br />

2003; 310: 830-835<br />

17 Nogueiras R, Pfluger P, Tovar S, Arnold M, Mitchell S,<br />

Morris A, Perez-Tilve D, Vázquez MJ, Wiedmer P, Castañeda<br />

TR, DiMarchi R, Tschöp M, Schurmann A, Joost HG, Williams<br />

LM, Langhans W, Diéguez C. Effects <strong>of</strong> obestatin on<br />

energy balance and growth hormone secretion in rodents.<br />

Endocrinology 2007; 148: 21-26<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

18 Lall S, Tung LY, Ohlsson C, Jansson JO, Dickson SL. Growth<br />

hormone (GH)-independent stimulation <strong>of</strong> adiposity by<br />

GH secretagogues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 280:<br />

132-138<br />

19 Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity<br />

in rodents. Nature 2000; 407: 908-913<br />

20 Hewson AK, Dickson SL. Systemic administration <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

induces Fos and Egr-1 proteins in the hypothalamic arcuate<br />

nucleus <strong>of</strong> fasted and fed rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2000; 12:<br />

1047-1049<br />

21 Dickson SL, Leng G, Robinson ICAF. (1993). Systemic administration<br />

<strong>of</strong> growth hormone-releasing peptide activates<br />

hypothalamic arcuate neurons. Neuroscience 1993; 54: 303-306<br />

22 Dickson SL, Luckman SM. Induction <strong>of</strong> c-fos messenger ribonucleic<br />

acid in neuropeptide Y and growth hormone (GH)releasing<br />

factor neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus following<br />

systemic injection <strong>of</strong> the GH secretagogue, GH-releasing peptide-6.<br />

Endocrinology 1997; 138: 771-777<br />

23 Hewson AK, Tung LY, Connell DW, Tookman L, Dickson<br />

SL. The rat arcuate nucleus integrates peripheral signals provided<br />

by leptin, insulin, and a ghrelin mimetic. <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2002;<br />

51: 3412-3419<br />

24 Jerlhag E, Egecioglu, E, Dickson SL, Andersson M, Svensson<br />

L, Engel JA. Ghrelin Stimulates Locomotor Activity and Accumbal<br />

Dopamine-Overflow via Central Cholinergic Systems<br />

in Mice: Implications for its Involvement in Brain Reward.<br />

Addict Biol 2004; 11: 45-54.<br />

25 Jerlhag E, Egecioglu E, Dickson SL, Douhan A, Svensson<br />

L, Engel JA. Ghrelin administration into tegmental areas<br />

stimulates locomotor activity and increases extracellular concentration<br />

<strong>of</strong> dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. Addict Biol<br />

2007; 12: 6-16<br />

26 Hewson AK, Tung LY, Connell DW, Tookman L, Dickson<br />

SL. The rat arcuate nucleus integrates peripheral signals<br />

provided by leptin, insulin, and a ghrelin mimetic. <strong>Diabetes</strong><br />

2002; 51: 3412-3419<br />

27 Kobeissy FH, Jeung JA, Warren MW, Geier JE, Gold MS.<br />

Changes in leptin, ghrelin, growth hormone and neuropeptide-Y<br />

after an acute model <strong>of</strong> MDMA and methamphetamine<br />

exposure in rats. Addict Biol 2008; 13: 15-25<br />

28 Wurst FM, Rasmussen DD, Hillemacher T, Kraus T, Ramskogler<br />

K, Lesch O, Bayerlein K, Schanze A, Wilhelm J,<br />

Junghanns K, Schulte T, Dammann G, Pridzun L, Wiesbeck<br />

G, Kornhuber J, Bleich S. Alcoholism, craving, and hormones:<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> leptin, ghrelin, prolactin, and the pro-opiomelanocortin<br />

system in modulating ethanol intake. Alcohol Clin<br />

Exp Res 2007; 31: 1963-1967<br />

29 Santos M, Bastos P, Gonzaga S, Roriz JM, Baptista MJ, Nogueira-Silva<br />

C, Melo-Rocha G, Henriques-Coelho T, Roncon-<br />

Albuquerque R Jr, Leite-Moreira AF, De Krijger RR, Tibboel<br />

D, Rottier R, Correia-Pinto J. Ghrelin expression in human<br />

and rat fetal lungs and the effect <strong>of</strong> ghrelin administration in<br />

nitr<strong>of</strong>en-induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Res<br />

2006; 59: 531-537<br />

30 Volante M, Fulcheri E, Allìa E, Cerrato M, Pucci A, Papotti M.<br />

Ghrelin expression in fetal, infant, and adult human lung. J<br />

Histochem Cytochem 2002; 50: 1013-1021<br />

31 Nunes S, Nogueira-Silva C, Dias E, Moura RS, Correia-Pinto<br />

J. Ghrelin and obestatin: different role in fetal lung development?<br />

Peptides 2008; 29: 2150-2158<br />

32 Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome.<br />

N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1334-1349<br />

33 Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> sepsis. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 138-150<br />

34 Heidecke CD, Hensler T, Weighardt H, Zantl N, Wagner H,<br />

Siewert JR, Holzmann B. Selective defects in T lymphocyte<br />

function in patients with lethal intraabdominal infection.<br />

Am J Surg 1999; 178: 288-292<br />

35 Wu R, Dong W, Zhou M, Zhang F, Marini CP, Ravikumar<br />

TS, Wang P. Ghrelin attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung<br />

injury and mortality in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;<br />

176: 805-813<br />

6 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

36 Hassig A, Kremer H, Liang WX, Stampfli K. The role <strong>of</strong><br />

the Th-1 to Th-2 shift <strong>of</strong> the cytokine pr<strong>of</strong>iles <strong>of</strong> CD4 helper<br />

cells in the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> autoimmune and hypercatabolic<br />

diseases. Med Hypotheses 1998; 51: 59-63<br />

37 Van den Berghe G. Endocrinology in intensive care medicine:<br />

new insights and therapeutic consequences. Verh K<br />

Acad Geneeskd Belg 2002; 64: 167-187; discussion 187-188<br />

38 van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx<br />

F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers<br />

P, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill<br />

patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1359-1367<br />

39 Das UN. Is insulin an antiinflammatory molecule? Nutrition<br />

2001; 17: 409-413<br />

40 Das UN. Insulin and the critically ill. Crit Care 2002; 6: 262-263<br />

41 Das UN. Is insulin an endogenous cardioprotector? Critical<br />

Care 2002; 6: 389-393<br />

42 Das UN. Current advances in sepsis and septic shock with<br />

particular emphasis on the role <strong>of</strong> insulin. Med Sci Monit 2003;<br />

9: RA181-RA192<br />

43 Johnson KL, Rn CR. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal<br />

axis in critical illness. AACN Clin Issues 2006; 17: 39-49<br />

44 Gauna C, van den Berghe GH, van der Lely AJ. Pituitary<br />

function during severe and life-threatening illnesses. Pituitary<br />

2005; 8: 213-217<br />

45 Vanhorebeek I, Langouche L, Van den Berghe G. Endocrine<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> acute and prolonged critical illness. Nat Clin Pract<br />

Endocrinol Metab 2006; 2: 20-31<br />

46 Chang L, Du JB, Gao LR, Pang YZ, Tang CS. Effect <strong>of</strong><br />

ghrelin on septic shock in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2003; 24:<br />

45-49<br />

47 Chang L, Zhao J, Yang J, Zhang Z, Tang C. Therapeutic<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> ghrelin on endotoxic shock in rats. Eur J Pharmacol<br />

2003; 473: 171-176<br />

48 Maitra SR, Wang S, Braithwaite CE, El-Maghrabi MR. Alterations<br />

in glucose-6-phophatase gene expression in sepsis. J<br />

Trauma 2000; 49: 38<br />

49 Li J, Zhang H, Wu F, Nan Y, Ma H, Guo W, Wang H, Ren J,<br />

Das UN, Gao F. Insulin inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha<br />

induction in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion: role <strong>of</strong> Akt<br />

and endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation. Crit<br />

Care Med 2008; 36: 1551-1558<br />

50 Saad MF, Bernaba B, Hwu CM, Jinagouda S, Fahmi S, Kogosov<br />

E, Boyadjian R. Insulin regulates plasma ghrelin concentration.<br />

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 3997-4000<br />

51 Yada T, Dezaki K, Sone H, Koizumi M, Damdindorj B,<br />

Nakata M, Kakei M. Ghrelin regulates insulin release and<br />

glycemia: physiological role and therapeutic potential. Curr<br />

<strong>Diabetes</strong> Rev 2008; 4: 18-23<br />

52 Sun Y, Asnicar M, Smith RG. Central and peripheral roles <strong>of</strong><br />

ghrelin on glucose homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology 2007; 86:<br />

215-228<br />

53 Li WG, Gavrila D, Liu X, Wang L, Gunnlaugsson S, Stoll<br />

LL, McCormick ML, Sigmund CD, Tang C, Weintraub NL.<br />

Ghrelin inhibits proinflammatory responses and nuclear factor-kappaB<br />

activation in human endothelial cells. Circulation<br />

2004; 109: 2221-2226<br />

54 Wu R, Zhou M, Cui X, Simms HH, Wang P. Upregulation <strong>of</strong><br />

cardiovascular ghrelin receptor occurs in the hyperdynamic<br />

phase <strong>of</strong> sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004; 287:<br />

H1296-H302<br />

55 Wu R, Dong W, Zhou M, Cui X, Hank Simms H, Wang P.<br />

Ghrelin improves tissue perfusion in severe sepsis via downregulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> endothelin-1. Cardiovasc Res 2005; 68: 318-326<br />

56 Maruna P, Gürlich R, Frasko R, Rosicka M. Ghrelin and<br />

leptin elevation in postoperative intra-abdominal sepsis. Eur<br />

Surg Res 2005; 37: 354-359<br />

57 Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani<br />

M, Ochani K, Yang LH, Hudson L, Lin X, Patel N, Johnson<br />

SM, Chavan S, Goldstein RS, Czura CJ, Miller EJ, Al-Abed Y,<br />

Tracey KJ, Pavlov VA. Modulation <strong>of</strong> TNF release by choline<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Das UN. Ghrelin and sepsis<br />

requires alpha7 subunit nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated<br />

signaling. Mol Med 2008; 14: 567-574<br />

58 Yoshikawa H, Kurokawa M, Ozaki N, Nara K, Atou K,<br />

Takada E, Kamochi H, Suzuki N. Nicotine inhibits the production<br />

<strong>of</strong> proinflammatory mediators in human monocytes<br />

by suppression <strong>of</strong> I-kappaB phosphorylation and nuclearkappaB<br />

transcriptional activity through nicotinic acetylcholine<br />

receptor alpha7. Clin Exp Immunol 2006; 145: 116-123<br />

59 Wu R, Dong W, Cui X, Zhou M, Simms HH, Ravikumar TS,<br />

Wang P. Ghrelin down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines<br />

in sepsis through activation <strong>of</strong> the vagus nerve. Ann Surg<br />

2007; 245: 480-486<br />

60 Wu R, Zhou M, Das P, Dong W, Ji Y, Yang D, Miksa M,<br />

Zhang F, Ravikumar TS, Wang P. Ghrelin inhibits sympathetic<br />

nervous activity in sepsis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab<br />

2007; 293: E1697-E1702<br />

61 Chorny A, Anderson P, Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado M. Ghrelin<br />

protects against experimental sepsis by inhibiting highmobility<br />

group box 1 release and by killing bacteria. J Immunol<br />

2008; 180: 8369-8377<br />

62 Wu R, Dong W, Zhou M, Zhang F, Marini CP, Ravikumar<br />

TS, Wang P. Ghrelin attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung<br />

injury and mortality in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;<br />

176: 805-813<br />

63 Wang W, Bansal S, Falk S, Ljubanovic D, Schrier R. Ghrelin<br />

protects mice against endotoxemia-induced acute kidney<br />

injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2009; 297: F1032- F1037<br />

64 Shah KG, Wu R, Jacob A, Blau SA, Ji Y, Dong W, Marini<br />

CP, Ravikumar TS, Coppa GF, Wang P. Human ghrelin ameliorates<br />

organ injury and improves survival after radiation<br />

injury combined with severe sepsis. Mol Med 2009; 15: 407-414<br />

65 Wu R, Dong W, Qiang X, Wang H, Blau SA, Ravikumar TS,<br />

Wang P. Orexigenic hormone ghrelin ameliorates gut barrier<br />

dysfunction in sepsis in rats. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 2421-2426<br />

66 Carlini VP, Monzon ME, Varas MM, Cragnolini AB, Schioth<br />

HB, Scimonelli TN, de Barioglio SR. Ghrelin increases anxiety-like<br />

behavior and memory retention in rats. Biochem Biophys<br />

Res Commun 2002; 299: 739-743<br />

67 Diano S, Farr SA, Benoit SC, McNay EC, da Silva I, Horvath B,<br />

Gaskin FS, Nonaka N, Jaeger LB, Banks WA, Morley JE, Pinto<br />

S, Sherwin RS, Xu L, Yamada KA, Sleeman MW, Tschöp MH,<br />

Horvath TL. Ghrelin controls hippocampal spine synapse<br />

density and memory performance. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9:<br />

381-388<br />

68 Getting SJ, Gibbs L, Clark AJ, Flower RJ, Perretti M. POMC<br />

gene-derived peptides activate melanocortin type 3 receptor<br />

on murine macrophages, suppress cytokine release, and inhibit<br />

neutrophil migration in acute experimental inflammation.<br />

J Immunol 1999; 162: 7446-7453<br />

69 Ichiyama T, Zhao H, Catania A, Furukawa S, Lipton JM.<br />

alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone inhibits NF-kappaB<br />

activation and IkappaBalpha degradation in human glioma<br />

cells and in experimental brain inflammation. Exp Neurol<br />

1999; 157: 359-365<br />

70 Cowley MA, Smith RG, Diano S, Tschop M, Pronchuk N,<br />

Grove KL. The distribution and mechanism <strong>of</strong> action <strong>of</strong> ghrelin<br />

in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit<br />

regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron 2003; 37: 649-661<br />

71 Wren AM, Small CJ, Fribbens CV, Neary NM, Ward HL, Seal<br />

LJ, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. The hypothalamic mechanisms <strong>of</strong><br />

the hypophysiotropic action <strong>of</strong> ghrelin. Neuroendocrinology<br />

2002; 76: 316-324<br />

72 Lutter M, Sakata I, Osborne-Lawrence S, Rovinsky SA,<br />

Anderson JG, Jung S, Birnbaum S, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist<br />

JK, Nestler EJ, Zigman JM. The orexigenic hormone ghrelin<br />

defends against depressive symptoms <strong>of</strong> chronic stress. Nat<br />

Neurosci 2008; 11: 752-753<br />

73 Himmerich H, Sheldrick AJ. TNF-alpha and ghrelin: opposite<br />

effects on immune system, metabolism and mental health.<br />

Protein Pept Lett 2010; 17: 186-196<br />

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Herholdt A E- Editor Liu N<br />

7 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Online Submissions: http://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358<strong>of</strong>fice<br />

wjd@wjgnet.com<br />

doi:10.4239/wjd.v2.i1.8<br />

ORIGINAL ARTICLES<br />

Excessive 5-year weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome<br />

development in healthy middle-aged adults<br />

Yu-Cheng Lin, Jong-Dar Chen, Pau-Chung Chen<br />

Yu-Cheng Lin, The Department <strong>of</strong> Occupational Medicine, En<br />

Chu Kong Hospital, New Taipei City, 23742, Taiwan, China<br />

Yu-Cheng Lin, School <strong>of</strong> Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University,<br />

New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan, China<br />

Jong-Dar Chen, Department <strong>of</strong> Family Medicine, Shin Kong<br />

Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Taipei 111, Taiwan, China<br />

Yu-Cheng Lin, Pau-Chung Chen, Institute <strong>of</strong> Occupational Medicine<br />

and Industrial Hygiene, College <strong>of</strong> Public Health, National<br />

Taiwan University, Taipei 100, Taiwan, China<br />

Author contributions: Lin YC collected and analyzed data; Lin<br />

YC and Chen JD interpreted data; Lin YC drafted the article;<br />

Chen JD revised critically for important intellectual content; and<br />

Chen PC finally approved the version to be published.<br />

Correspondence to: Pau-Chung Chen, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Occupational Medicine and Industrial Hygiene, College <strong>of</strong> Public<br />

Health, National Taiwan University, No. 17, Xu-Zhou Road, Taipei<br />

10020, Taiwan, China. pchen@ntu.edu.tw<br />

Telephone: +886-02-3366-8088 Fax: +886-02-2341-8570<br />

Received: August 31, 2010 Revised: December 1, 2010<br />

Accepted: December 8, 2010<br />

Published online: January 15, 2011<br />

Abstract<br />

AIM: To quantitatively examine the impacts <strong>of</strong> an easyto-measure<br />

parameter - weight gain - on metabolic<br />

syndrome development among middle-aged adults.<br />

METHODS: We conducted a five-year interval observational<br />

study. A total <strong>of</strong> 1384 middle-aged adults not<br />

meeting metabolic syndrome (MetS) criteria at the initial<br />

screening were included in our analysis. Baseline data<br />

such as MetS-components and lifestyle factors were<br />

collected in 2002. Body weight and MetS-components<br />

were measured in both 2002 and 2007. Participants<br />

were classified according to proximal quartiles <strong>of</strong><br />

weight gain (WG) in percentages (%WG ≤ 1%, 1% <<br />

%WG ≤ 5%, 5% < %WG ≤ 10% and %WG > 10%,<br />

defined as: control, mild-WG, moderate-WG and severe-<br />

WG groups, respectively) at the end <strong>of</strong> the follow-up.<br />

Multivariate models were used to assess the association<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

<strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011 January 15; 2(1): 8-15<br />

ISSN 1948-9358 (online)<br />

© 2011 Baishideng. All rights reserved.<br />

between MetS outcome and excessive WG in the total<br />

population, as well as in both genders.<br />

RESULTS: In total, 175 (12.6%) participants fulfilled<br />

MetS criteria within five years. In comparison to the control<br />

group, mild-WG adults had an insignificant risk for<br />

MetS development while adults having moderate-WG<br />

had a 3.0-fold increased risk for progression to MetS<br />

[95% confidence interval (CI), 1.8-5.1], and this risk<br />

was increased 5.4-fold (95% CI, 3.0-9.7) in subjects<br />

having severe-WG. For females having moderate- and<br />

severe-WG, the risk for developing MetS was 3.6 (95%<br />

CI, 1.03-12.4) and 5.5 (95% CI, 1.4-21.4), respectively.<br />

For males having moderate- and severe-WG, the odds<br />

ratio for MetS outcome was respectively 3.0 (95% CI,<br />

1.6-5.5) and 5.2 (95% CI, 2.6-10.2).<br />

CONCLUSION: For early-middle-aged healthy adults<br />

with a five-year weight gain over 5%, the severity <strong>of</strong><br />

weight gain is related to the risk for developing metabolic<br />

syndrome.<br />

© 2011 Baishideng. All rights reserved.<br />

Key words: Excess weight gain; Metabolic syndrome;<br />

Middle-aged adults; Follow-up; Worker population<br />

Peer reviewers: Yoshinari Uehara, MD, PhD, Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Cardiology, Fukuoka University Faculty <strong>of</strong> Medicine, 7-45-1<br />

Nanakuma, Jonan-ku, Fukuoka 814-0180 Japan; Mark A Sperling,<br />

MD, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics, Children's Hospital <strong>of</strong> Pittsburgh<br />

<strong>of</strong> UPMC, 4401 Penn Avenue, Division <strong>of</strong> Endocrinology,<br />

Faculty Pavilion -8th Floor, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, United States;<br />

Narattaphol Charoenphandhu, MD, PhD, Department <strong>of</strong> Physiology,<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Science, Mahidol University, Rama VI Road,<br />

Bangkok 10400, Thailand<br />

Lin YC, Chen JD, Chen PC. Excessive 5-year weight gain<br />

predicts metabolic syndrome development in healthy middleaged<br />

adults. <strong>World</strong> J <strong>Diabetes</strong> 2011; 2(1): 8-15 Available from:<br />

URL: http://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v2/i1/8.htm DOI:<br />

http://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v2.i1.8<br />

8 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

INTRODUCTION<br />

Measuring body weight is noninvasive, inexpensive and<br />

reliable both in terms <strong>of</strong> clinical and self-health monitoring<br />

[1] . Analyses from the general population have<br />

revealed excessive weight gain (WG) as an important risk<br />

factor for developing metabolic syndrome (MetS) [2,3] . MetS<br />

is also becoming an important concern in workplaces [4-6]<br />

for its impacts on both the health condition [7] and productivity<br />

[8] <strong>of</strong> employees. Excessive WG is common in<br />

the early-middle-aged population [9,10] who account for<br />

the majority <strong>of</strong> the workforce. However, there was a lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> a comprehensive follow-up survey for examining the<br />

possible quantitative association between WG severity<br />

and the risk for MetS development in the early-middleaged<br />

worker population. Improving our knowledge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

impacts <strong>of</strong> WG on MetS development is helpful to health<br />

promotion in workplaces. Since periodic routine health<br />

checkups are compulsory for employees at many worksites<br />

in Taiwan, we had an opportunity to conduct a workplacebased<br />

follow-up observation for MetS development. We<br />

used this approach to evaluate the impacts <strong>of</strong> excessive<br />

WG on MetS development among early-middle-aged employees.<br />

MATERIALS AND METHODS<br />

Participants<br />

A flowchart <strong>of</strong> the experimental protocol is shown below<br />

in the Figure 1. In 2002 and 2007, 1648 eligible employees<br />

<strong>of</strong> an electronic manufacturing company underwent compulsory<br />

health checkups in accordance with the Labor<br />

Health Protection Regulation <strong>of</strong> the Labor Safety and Health Act.<br />

The final analysis <strong>of</strong> this follow-up study only included<br />

subjects who did not fulfill MetS criteria in 2002. In total,<br />

256 employees were excluded from the study because they<br />

had been screened previously for MetS. Final records from<br />

a total <strong>of</strong> 1384 workers (338 female and 996 male workers,<br />

aged 18 to 58 years with a mean age <strong>of</strong> 32.3 years) made<br />

up the cohort for the study and for the endpoint analysis.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the employees <strong>of</strong> this electronics manufacturing<br />

company were residents <strong>of</strong> northern Taiwan.<br />

The health examination was open to all registered<br />

employees during every working day within a one-month<br />

period. All <strong>of</strong> the employees were recommended to avoid<br />

vigorous physical exercise for three days before their<br />

health examination. The subjects’ identities were anonymous<br />

and were not linked to the data. This analytical<br />

study, limited to health checkup records, followed the<br />

ethical criteria for human research and the study protocol<br />

(TYGH09702108) was reviewed and approved by the<br />

Ethics Committee <strong>of</strong> the Tao-Yuan General Hospital,<br />

Taiwan.<br />

Demographics, lifestyle data, and biological<br />

measurements<br />

In 2002, the examinees completed a questionnaire about<br />

their baseline personal history, including their lifestyle<br />

factors.<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Lin YC et al . Excessive weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome<br />

A total 1648 eligible employees completed a questionnaire about their<br />

baseline personal, occupational and lifestyle history; received physical<br />

checkups including Mets components and body weight, in 2002<br />

1384 workers not fulfilling Mets criteria in 2002 were<br />

followed up for Mets components and body weight, in 2007<br />

175 workers fulfilled Mets<br />

criteria in 2007<br />

Figure 1 Flowchart <strong>of</strong> experimental protocol.<br />

256 workers were excluded<br />

from the study because being<br />

screened Mets in 2002<br />

1209 workers did not fulfill<br />

Mets criteria in 2007<br />

Physical examinations and blood tests were performed<br />

on all participants in both 2002 and 2007. The participants<br />

arrived at the health care unit <strong>of</strong> the factory in the morning,<br />

between 07:30 and 09:30 h, after an overnight 8<br />

h fast. The physical examination records included measurements<br />

<strong>of</strong> waist circumference, weight, height and<br />

blood pressure. All the measuring apparatuses were rou<br />

tinely calibrated. Waist circumference was measured midway<br />

between the lowest rib and the superior border <strong>of</strong><br />

the iliac crest. After being seated for 5 min, sitting blood<br />

pressure was measured with the dominant arm using digital<br />

automatic sphygmomanometers (model HEM 907,<br />

Omron, Japan) two times with a 5 min interval; the mean<br />

<strong>of</strong> these readings was used in the data analysis. After the<br />

physical examination, participants were placed in a reclined<br />

position, and venous blood (20 mL) was taken from an<br />

antecubital vein <strong>of</strong> the arm for subsequent tests. Blood<br />

specimens were centrifuged immediately thereafter, and<br />

were frozen and shipped on dry ice to a central clinical<br />

laboratory in the Tao-Yuan General Hospital (certified<br />

by ISO 15189 and ISO 17025). Glucose, triglyceride and<br />

high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol analyses were<br />

conducted by a Hitachi autoanalyzer model 7150 (Hitachi,<br />

Tokyo, Japan).<br />

Weight gain evaluation<br />

Weight gain (WG) was calculated as a percentage by the<br />

formula: [(body weight 2007 - body weight 2002)/body weight<br />

2002] and was represented as %WG. Participants were classified<br />

into four subgroups according to their proximal<br />

quartiles <strong>of</strong> increased weight gain (%WG ≤ 1%, 1% <<br />

%WG ≤ 5%, 5% < %WG ≤ 10% and 10% > %WG,<br />

defined as: control, mild-WG, moderate-WG and severe-<br />

WG groups, respectively) at end <strong>of</strong> the follow-up examination.<br />

Metabolic syndrome<br />

The MetS designation was made if three or more <strong>of</strong> the<br />

following five criteria were fulfilled: central obesity (waist<br />

9 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

the two genders. Also, as shown at the bottom <strong>of</strong> Table<br />

1, 12.6 % <strong>of</strong> total population developed MetS within five<br />

years; this value was 8.8% for female and was significantly<br />

higher for male workers, at 14.2%.<br />

Among the four WG subgroups (Table 2), the baseline<br />

measurements <strong>of</strong> body weight, body mass index, waist circumstance<br />

and most lifestyle factors were not significantly<br />

different, except that workers who had moderate and<br />

severe weight gain tended to snack before sleeping. The<br />

mean age <strong>of</strong> the severe-WG subgroup was lower than<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the other subgroups and the severe-WG subgroup<br />

was healthier than other subgroups at beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

experiment in terms <strong>of</strong> the baseline MetS-component<br />

measures. Table 2 also shows that the five-year occurrence<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> MetS were significantly higher in the moderate-<br />

and severe-WG subgroups.<br />

Since the baseline measurements were significantly<br />

different between the two genders, Table 3 presents the<br />

baseline data for the MetS-components according to the<br />

severity <strong>of</strong> weight gain for both genders. For the earlymiddle-aged<br />

females, the subjects showing severe-WG<br />

were younger than those in other WG groups. Although<br />

the majority <strong>of</strong> baseline characteristics were similar, females<br />

who gained a moderate or severe amount <strong>of</strong> weight<br />

tended to snack between meals and before sleeping (Table<br />

3). In our male adults, the severe WG group was the youngest<br />

and had better MetS-component baseline data than<br />

the other subgroups. Males who gained a moderate or<br />

severe amount <strong>of</strong> weight were inclined to snack before<br />

sleeping.<br />

Table 4 presents the changes <strong>of</strong> MetS-component<br />

factors and the occurrence <strong>of</strong> MetS among four WG<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Lin YC et al . Excessive weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome<br />

Table 2 Summary <strong>of</strong> baseline characteristics <strong>of</strong> variables for the total population and five-year occurrence rates <strong>of</strong> metabolic<br />

syndrome according to the severity <strong>of</strong> weight gain (N = 1384)<br />

Baseline data WG within 5 years<br />

Control Mild Moderate Severe<br />

%WG ≤ 1% 1% < %WG ≤ 5% 5% < %WG ≤ 10% %WG > 10%<br />

n = 341 n =337 n =387 n =391<br />

Measurements; mean (standard deviation)<br />

Age (year) b<br />

33.5 (6.8) 33.3 (6.4) 32.4 (6.4) 29.7 (5.7)<br />

Body weight (kg) 64.4 (10.5) 63.9 (11.8) 63.6 (11.0) 62.9 (10.3)<br />

Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) 23.3 (2.8) 23.1 (3.0) 23.0 (3.2) 22.6 (2.9)<br />

Waist (cm) 76.0 (8.2) 75.8 (8.9) 75.8 (9.1) 74.5 (8.0)<br />

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) a<br />

118.9 (14.5) 116.4 (14.4) 117.0 (15.0) 115.7 (13.3)<br />

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) b<br />

73.3 (9.4) 71.7 (9.3) 71.5 (9.8) 70.2 (7.8)<br />

Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) a<br />

95.8 (15.1) 94.5 (7.9) 93.9 (7.4) 92.8 (19.5)<br />

Triglycerides (mg/dL) b<br />

115.4 (118.8) 105.5 (65.0) 98.8 (55.9) 89.9 (52.2)<br />

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)<br />

Prevalent rates (%)<br />

Lifestyle factors<br />

49.2 (11.0) 50.6 (12.7) 50.8 (12.6) 51.6 (10.7)<br />

Physical exercise; > 3 times a week 34.90% 30.90% 31.30% 31.30%<br />

Habitual drinker 6.20% 7.10% 8.50% 3.90%<br />

Having snacks before sleeping (≥ third a week) b<br />

34.00% 35.90% 44.20% 43.30%<br />

Having snacks between meals (≥ third a week) 46.60% 43.60% 47.00% 48.90%<br />

Ever been a smoker (yes vs no) 31.10% 29.70% 33.10% 34.80%<br />

MetS development within 5 years 9.10% b<br />

9.50% b<br />

15.80% b<br />

16.00% b<br />

a P < 0.05; b P < 0.01; An ANOVA was conducted, adjusting for age, using a Tukey’s test. A trend test was conducted for categorical variables. WG: weight<br />

gain; HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol.<br />

subgroups for each gender. For our early-middle-aged<br />

females, the changes in the factors for central obesity<br />

and in Low-HDL levels were significantly less favorable<br />

in workers who gained moderate or severe amounts <strong>of</strong><br />

weight and the development <strong>of</strong> MetS was found to be<br />

significantly higher in these subgroups than in others. For<br />

the male adults in our study, the moderate- and severs-<br />

WG subgroups showed significantly more unfavorable<br />

changes in nearly all MetS-components and had higher<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> MetS within five years than mild-WG and control<br />

subgroups.<br />

After controlling for the confounding factors <strong>of</strong> initial<br />

age, MetS-components and lifestyle factors, a multivariate<br />

analysis was conducted and the results are shown in Table<br />

5. The risk <strong>of</strong> developing MetS in subjects with moderate-<br />

and severe-WG was 3.0-times [95% confidence interval<br />

(CI), 1.8-5.1] and 5.4-times (95% CI, 3.0-9.7) greater<br />

than with the control group. For female workers with<br />

moderate- and severe-WG, the risk <strong>of</strong> developing MetS<br />

was 3.6-times (95% CI, 1.03-12.4) and 5.5-times (95%<br />

CI, 1.4-21.4) higher than the control group. Females who<br />

had been smokers had an increased risk (6.7 times higher,<br />

95% CI, 1.2-36.7) <strong>of</strong> developing MetS than those who<br />

had never smoked. The risk <strong>of</strong> developing MetS in male<br />

adults with moderate- and severe-WG was 3.0-times [95%<br />

confidence interval (CI), 1.6-5.5] and 5.2-times (95% CI,<br />

2.6-10.2) greater than the control group.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

In this five-year interval follow up, approximately half<br />

<strong>of</strong> healthy middle-aged adults had a WG <strong>of</strong> over 5%,<br />

11 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

Lin YC et al . Excessive weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome<br />

Table 3 Summary <strong>of</strong> baseline characteristics <strong>of</strong> variables for female and male adults according to the severity <strong>of</strong> weight gain<br />

and a quarter <strong>of</strong> the overall sample had a WG <strong>of</strong> more<br />

than 10%. Major clinical manifestations in adults, such<br />

as cardiovascular complications and diabetes, have been<br />

associated with excess WG [10,15] . In a preventive sense, our<br />

analyses show that the development <strong>of</strong> MetS, a precursor<br />

<strong>of</strong> diabetes [16,17] , is significantly quantitatively associated<br />

with a five-year WG exceeding 5% in healthy early-middleaged<br />

adults <strong>of</strong> both genders (Table 5).<br />

Waist circumference is an important factor for MetS.<br />

It is likely that weight gain contributes to increases in<br />

waist circumference. However, for the general population,<br />

the body weight measurement is less rigorous than waist<br />

measurement which has a specific anatomic definitions [18]<br />

and ,therefore, present study investigated changes in<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Female N = 388<br />

Baseline data WG within 5 years<br />

Control Mild Moderate Severe<br />

%WG ≤ 1% 1% < %WG ≤ 5% 5% < %WG ≤ 10% %WG >10%<br />

n = 105 n = 100 n = 99 n = 84<br />

Measurements; mean (standard deviation)<br />

Age (year) 33.6 (8.7) 33.0 (7.4) 33.1 (8.1) 31.1 (7.0)<br />

Body weight (kg) 55.3 (7.3) 53.0 (7.5) 53.5 (8.3) 55.3 (8.8)<br />

Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) b<br />

23.9 (2.7) 23.8 (2.8) 23.3 (3.0) 22.6 (2.8)<br />

Waist (cm) 68.8 (5.9) 67.8 (6.4) 68.1 (7.9) 69.5 (7.2)<br />

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 112.2 (13.8) 109.7 (12.1) 113.2 (14.6) 110.6 (12.9)<br />

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 68.9 (9.0) 67.7 (8.8) 69.8 (9.6) 67.7 (8.1)<br />

Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) 94.0 (9.1) 94.7 (8.6) 94.2 (7.0) 91.9 (7.4)<br />

Triglycerides (mg/dL) 79.4 (38.3) 73.4 (33.6) 74.0 (33.1) 73.2 (51.9)<br />

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)<br />

Prevalent rates (%)<br />

Lifestyle factors<br />

53.2 (11.6) 57.1 (12.9) 56.4 (14.4) 55.6 (10.2)<br />

Physical exercise; ≥ 3 times a week 25.70% 26.00% 23.20% 27.40%<br />

Habitual drinker 1.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00%<br />

Having snacks before sleeping (≥ third a week) 28.60% 26.00% 44.40% 27.40%<br />

Having snacks between meals (≥ third a week) 59.00% 55.00% 74.70% 54.80%<br />

Ever been a smoker (yes vs no) 6.70% 3.00% 4.00% 7.10%<br />

Male N = 996<br />

Baseline data WG within 5 years<br />

Control Mild Moderate Severe<br />

%WG ≤ 1% 1% < %WG ≤ 5% 5% < %WG ≤ 10% %WG > 10%<br />

n = 236 n = 237 n = 288 n = 235<br />

Measurements; mean (standard deviation)<br />

Age (year) b<br />

33.4 (5.7) 33.5 (6.0) 32.2 (5.7) 29.2 (5.0)<br />

Body weight (kg) b<br />

68.5 (9.0) 68.6 (10.1) 67.1 (9.6) 65.6 (9.5)<br />

Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) 22.2 (2.8) 21.6 (2.8) 21.8 (3.5) 22.4 (3.1)<br />

Waist (cm) b<br />

79.3 (7.0) 79.2 (7.5) 78.4 (7.9) 76.3 (7.5)<br />

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) b<br />

121.8 (13.8) 119.2 (14.3) 118.2 (14.9) 117.6 (13.0)<br />

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) b<br />

75.2 (8.9) 73.4 (8.9) 72.0 (9.8) 71.1 (7.6)<br />

Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) 96.6 (17.1) 94.4 (7.6) 93.8 (7.5) 93.2 (22.3)<br />

Triglycerides (mg/dL) b<br />

131.5 (137.6) 119.1 (70.2) 107.3 (59.5) 95.9 (51.1)<br />

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) a<br />

Prevalent rates (%)<br />

Lifestyle factors<br />

47.4 (10.3) 47.9 (11.5) 48.8 (11.3) 50.1 (10.5)<br />

Physical exercise; ≥ 3 times a week 39.00% 32.90% 34.00% 32.80%<br />

Habitual drinker 8.50% 10.10% 11.50% 9.40%<br />

Having snacks before sleeping (≥ third a week) a 36.40% 40.10% 44.10% 48.90%<br />

Having snacks between meals (≥ third a week) 41.10% 38.80% 37.50% 46.80%<br />

Ever been a smoker (yes vs no) 41.90% 40.90% 43.10% 44.70%<br />

a P < 0.05, b P < 0.01, An ANOVA was conducted, adjusting for age, using a Tukey’s test. A trend test was conducted for categorical variables; WG: weight<br />

gain; HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol.<br />

weight. Nevertheless, we treated waist circumference as a<br />

confounder in the multivariate analysis (Table 5) because<br />

it has a decisive influence on the development <strong>of</strong> metabolic<br />

syndrome. On the other hand, occupational and<br />

lifestyle factors naturally affect dietary behaviors and thus<br />

affect body weight changes [19] and other factors <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis<br />

which are important in MetS development,<br />

including total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol,<br />

uric acid and insulin. Our present study focused<br />

on body weight changes, and although we controlled<br />

some occupational, lifestyle and baseline metabolic factors<br />

(not shown in tables), the detailed impact <strong>of</strong> these factors<br />

needs to be clarified by other investigations.<br />

Findings from both our study (Table 4) and other<br />

12 January 15, 2011|Volume 2|Issue 1|

follow-up observations [20] indicate that the adults without<br />

excess WG have stable or improved serum levels <strong>of</strong><br />

HDL and glucose, while the adults gaining excess weight<br />

over several years have dramatically greater changes in<br />

triglyceride levels than other groups. HDL levels demonstrated<br />

improving trends in our middle aged sample population.<br />

This dissimilar to earlier findings in an elderly<br />

population [21] , but similar to what was shown in other<br />

follow-up observations for healthy Asian adults [22] . Discussing<br />

these findings in an earlier article [12] ; we suggested<br />

that our relative young healthy workers might not yet<br />

have reached their HDL concentration plateau so had the<br />

potential to increase their HDL concentration within our<br />

WJD|www.wjgnet.com<br />

Lin YC et al . Excessive weight gain predicts metabolic syndrome<br />

Table 4 Summary <strong>of</strong> five-year changes in metabolic syndrome-components for female and male adults and the occurrence rates <strong>of</strong><br />

metabolic syndrome according to the severity <strong>of</strong> weight gain<br />

Female N = 388<br />

Follow-up changes (%) WG within 5 years<br />

Control Mild Moderate Severe<br />

%WG ≤ 1% 1% < %WG ≤ 5% 5% < %WG ≤ 10% %WG > 10%<br />

n = 105 n = 100 n = 99 n = 84<br />

△Central obesity b<br />

8.50% 16.00% 22.60% 32.80%<br />

△High blood pressure 22.90% 28.70% 28.50% 37.00%<br />

△Hyperglycemia -3.40% -4.20% -3.10% 1.30%<br />

△Hypertriglyceridemia b<br />

-0.40% 8.00% 15.60% 24.30%<br />

△Low-HDL cholesterol b<br />

-14.40% -17.70% -5.90% -6.00%<br />

MetS Development within 5 years b<br />

5.70% 3.00% 14.10% 13.10%<br />

Male N = 996<br />

Follow-up changes (%) WG within 5 years<br />

Control Mild Moderate Severe<br />

%WG ≤ 1% 1% < %WG ≤ 5% 5% < %WG ≤ 10% %WG > 10%<br />

n = 236 n = 237 n = 288 n = 235<br />

△Central obesity b<br />

10.00% 3.00% 21.20% 40.50%<br />

△High blood pressure a<br />

21.00% 20.00% 21.20% 19.00%<br />

△Hyperglycemia -8.00% -11.00% -5.10% -2.40%<br />

△Hypertriglyceridemia b<br />

2.00% 2.00% 8.10% 11.90%<br />

△Low-HDL cholesterol b<br />

-34.00% -24.00% -24.20% -7.10%<br />

MetS development within 5 years 10.60% 12.20% 16.30% 17.00%<br />

a b<br />

P < 0.05; P < 0.01; An ANOVA was conducted, adjusting for age, using Tukey’s test. Δ: Differences between 2007 and 2002; minus indicates decreasing<br />