Marketing - Pearson

Marketing - Pearson

Marketing - Pearson

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Preface<br />

The Twelfth Edition—Creating More<br />

Value for You!<br />

The goal of Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong>, twelfth edition, is to introduce new marketing students to<br />

the fascinating world of modern marketing in an innovative yet practical and enjoyable way.<br />

Like any good marketer, we’re out to create more value for you, our customer. We’ve poured<br />

over every page, table, figure, fact, and example in an effort to make this the best text from<br />

which to learn about and teach marketing.<br />

Today’s marketing is all about creating customer value and building profitable customer<br />

relationships. It starts with understanding consumer needs and wants, deciding which target<br />

markets the organization can serve best, and developing a compelling value proposition by<br />

which the organization can win, keep, and grow targeted consumers. If an organization does<br />

these things well, it will reap the rewards in terms of market share, profits, and customer equity.<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> is much more than just an isolated business function—it is a philosophy that<br />

guides the entire organization. The marketing department cannot create customer value and<br />

build profitable customer relationships by itself. This is a companywide undertaking that<br />

involves broad decisions about who the company wants as its customers, which needs to satisfy,<br />

what products and services to offer, what prices to set, what communications to send,<br />

and what partnerships to develop. <strong>Marketing</strong> must work closely with other company departments<br />

and with other organizations throughout its entire value-delivery system to delight customers<br />

by creating superior customer value.<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong>: Creating Customer Value<br />

and Relationships<br />

From beginning to end, Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong> develops an innovative customer-value and<br />

customer-relationships framework that captures the essence of today’s marketing.<br />

Five Major Value Themes<br />

The twelfth edition builds on five major value themes:<br />

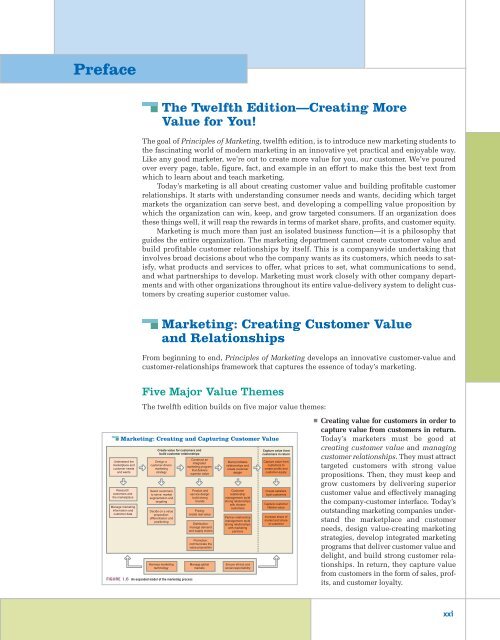

<strong>Marketing</strong>: Creating and Capturing Customer Value<br />

Understand the<br />

marketplace and<br />

customer needs<br />

and wants<br />

Research<br />

customers and<br />

the marketplace<br />

Manage marketing<br />

information and<br />

customer data<br />

Create value for customers and<br />

build customer relationships<br />

Design a<br />

customer-driven<br />

marketing<br />

strategy<br />

Select customers<br />

to serve: market<br />

segmentation and<br />

targeting<br />

Decide on a value<br />

proposition:<br />

differentiation and<br />

positioning<br />

Harness marketing<br />

technology<br />

FIGURE 1.6 An expanded model of the marketing process<br />

Construct an<br />

integrated<br />

marketing program<br />

that delivers<br />

superior value<br />

Product and<br />

service design:<br />

build strong<br />

brands<br />

Pricing:<br />

create real value<br />

Distribution:<br />

manage demand<br />

and supply chains<br />

Promotion:<br />

communicate the<br />

value proposition<br />

Manage global<br />

markets<br />

Build profitable<br />

relationships and<br />

create customer<br />

delight<br />

Customer<br />

relationship<br />

management: build<br />

strong relationships<br />

with chosen<br />

customers<br />

Partner relationship<br />

management: build<br />

strong relationships<br />

with marketing<br />

partners<br />

Ensure ethical and<br />

social responsibility<br />

Capture value from<br />

customers in return<br />

Capture value from<br />

customers to<br />

create profits and<br />

customer equity<br />

Create satisfied,<br />

loyal customers<br />

Capture customer<br />

lifetime value<br />

Increase share of<br />

market and share<br />

of customer<br />

■ Creating value for customers in order to<br />

capture value from customers in return.<br />

Today’s marketers must be good at<br />

creating customer value and managing<br />

customer relationships. They must attract<br />

targeted customers with strong value<br />

propositions. Then, they must keep and<br />

grow customers by delivering superior<br />

customer value and effectively managing<br />

the company-customer interface. Today’s<br />

outstanding marketing companies understand<br />

the marketplace and customer<br />

needs, design value-creating marketing<br />

strategies, develop integrated marketing<br />

programs that deliver customer value and<br />

delight, and build strong customer relationships.<br />

In return, they capture value<br />

from customers in the form of sales, profits,<br />

and customer loyalty.<br />

xxi

xxii Preface<br />

FIGURE 2.8<br />

Return on marketing<br />

Source: Adapted from Roland T.<br />

Rust, Katherine N. Lemon, and<br />

Valerie A. Zeithamal, “Return<br />

on <strong>Marketing</strong>: Using Consumer<br />

Equity to Focus <strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Strategy,” Journal of <strong>Marketing</strong>,<br />

January 2004, p. 112.<br />

This innovative customer-value framework is introduced at the start of Chapter 1 in a<br />

five-step marketing process model, which details how marketing creates customer value and<br />

captures value in return. The framework is carefully explained in the first two chapters, providing<br />

students with a solid foundation. The framework is then integrated throughout the<br />

remainder of the text.<br />

■ Building and managing strong, value-creating brands. Well-positioned brands with<br />

strong brand equity provide the basis upon which to build customer value and profitable<br />

customer relationships. Today’s marketers must position their brands powerfully and<br />

manage them well.<br />

■ Managing return on marketing to recapture value. In order to capture value from customers<br />

in return, marketing managers must be good at measuring and managing the return on their<br />

marketing investments. They must ensure that their marketing dollars are being well spent.<br />

In the past, many marketers spent freely on<br />

Measuring and Managing Return<br />

on <strong>Marketing</strong> Investment<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> investments<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> returns<br />

Improved customer value and satisfaction<br />

Increased customer<br />

attraction<br />

Increased customer<br />

retention<br />

Increased customer lifetime values<br />

and customer equity<br />

Return on marketing investment<br />

Cost of marketing<br />

investment<br />

big, expensive marketing programs, often<br />

without thinking carefully about the financial<br />

and customer response returns on their<br />

spending. But all that is changing rapidly.<br />

Measuring and managing return on marketing<br />

investments has become an important<br />

part of strategic marketing decision making.<br />

■ Harnessing new marketing technologies.<br />

New digital and other high-tech marketing<br />

developments are dramatically changing<br />

how marketers create and communication<br />

customer value. Today’s marketers must<br />

know how to leverage new computer,<br />

information, communication, and distribution<br />

technologies to connect more effectively<br />

with customers and marketing partners<br />

in this digital age.<br />

■ <strong>Marketing</strong> in a socially responsible way around the globe. As technological developments<br />

make the world an increasingly smaller place, marketers must be good at marketing<br />

their brands globally and in socially responsible ways that create not just short-term value for<br />

individual customers but also long-term value for society as a whole.<br />

Important Changes and Additions<br />

We’ve thoroughly revised the twelfth edition of Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong> to reflect the major<br />

trends and forces impacting marketing in this era of customer value and relationships. Here are<br />

just some of the major changes you’ll find in this edition.<br />

■ This new edition builds on and extends the innovative customer-value framework from previous<br />

editions. No other marketing text presents such a clear and comprehensive customervalue<br />

approach.<br />

■ The integrated marketing communications chapters have been completely restructured to<br />

reflect sweeping shifts in how today’s marketers communicate value to customers.<br />

■ A newly revised Chapter 14—Communicating Customer Value—addresses today’s shifting<br />

integrated marketing communications model. It tells how marketers are now adding a<br />

host new-age media—everything from interactive TV and the Internet to iPods and cell<br />

phones to reach targeted customers with more personalized messages.<br />

■ Advertising and public relations are now combined in Chapter 15, which includes<br />

important new discussions on “Madison & Vine” (the merging of advertising and entertainment<br />

to break through the clutter), return on advertising, and other important topics.<br />

A restructured Chapter 16 now combines personal selling and sales promotion.<br />

■ The new Chapter 17—Direct and Online <strong>Marketing</strong>—provides focused new coverage of<br />

direct marketing and its fastest-growing arm, marketing on the Internet. The new chapter<br />

includes a section on new digital direct-marketing technologies, such as mobile<br />

phone marketing, podcasts and vodcasts, and interactive TV.

Appendix 2<br />

MARKETING BY THE NUMBERS<br />

■ We’ve revised the pricing discussions in Chapter 10—Pricing: Understanding and<br />

Capturing Customer Value. It now focuses on customer-value-based pricing—on understanding<br />

and capturing customer value as the basis for setting and adjusting prices. The<br />

revised chapter includes new discussions of “good-value” and “value-added” pricing strategies,<br />

dynamic pricing, and competitive pricing considerations.<br />

■ In line with the text’s emphasis on measuring and managing return on marketing, we’ve added<br />

a new Appendix 2: <strong>Marketing</strong> by the Numbers. This comprehensive<br />

new appendix introduces students to the marketing financial analysis that<br />

helps to guide, assess, and sup-<br />

432 Part 3 Designing a Customer-Driven <strong>Marketing</strong> Strategy and <strong>Marketing</strong> Mix<br />

Madison & Vine: The New Intersection<br />

Real <strong>Marketing</strong> of Advertising and Entertainment<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> decisions are coming under increasing scrutiny, and marketing managers must be<br />

accountable for the financial implications of their actions. This appendix provides a basic<br />

Welcome to the ever-busier intersection of Madison &<br />

introduction to marketing financial analysis. Such analysis guides marketers in making sound 15.1 Vine, where the advertising industry meets the enter-<br />

marketing decisions and in assessing the outcomes of those decisions.<br />

tainment industry. In today’s cluttered advertising environment,<br />

The appendix is built around a hypothetical manufacturer of high-definition consumer Madison Avenue knows that it must find new ways to engage ad-<br />

electronics products—HDX-treme. This company is launching a new product, and we will weary consumers with more compelling messages. The answer?<br />

discuss and analyze the various decisions HDX-treme’s marketing managers must make Entertainment! And who knows more about entertainment than the<br />

before and after launch.<br />

folks at Hollywood & Vine? The term “Madison & Vine” has come to<br />

HDX-treme manufactures high-definition televisions for the consumer market. The com- represent the merging of advertising and entertainment. It takes one<br />

pany has concentrated on televisions but is now entering the accessories market. of two primary forms: advertainment or branded entertainment.<br />

Specifically, the company is introducing a high-definition optical disc player (DVD) using The aim of advertainment is to make ads themselves so entertain-<br />

the Blu-ray format.<br />

ing, or so useful, that people want to watch them. It’s advertising by<br />

The appendix is organized into three sections. The first section deals with the pricing invitation rather than by intrusion. There’s no chance that you’d<br />

considerations and break-even and margin analysis assessments that guide the introduction watch ads on purpose, you say? Think again. For example, the Super<br />

of HDX-treme’s new-product launch. The second section begins with a discussion of estimat- Bowl has become an annual advertainment showcase. Tens of miling<br />

market potential and company sales. It then introduces the marketing budget, as illuslions of people tune in to the Super Bowl each year, as much to watch<br />

trated through a pro forma profit-and-loss statement followed by the actual profit-and-loss the entertaining ads as to see the game.<br />

statement. Next, the section discusses marketing performance measures, with a focus on help- And rather than bemoaning TiVo and other DVR systems, many<br />

ing marketing managers to better defend their decisions from a financial perspective. In the advertisers are now using them as a new medium for showing useful<br />

final section, we analyze the financial implications of various marketing tactics, such as or entertaining ads that consumers actually volunteer to watch. For<br />

increasing advertising expenditures, adding sales representatives to increase distribution, example, TiVo recently launched Product Watch, a service offering<br />

lowering price, or extending the product line.<br />

special on-demand ads to subscribers from companies such as Kraft<br />

At the end of each section, quantitative exercises provide you with an opportunity to Foods, Ford, Lending Tree, and Pioneer Electronics. Longer than tra-<br />

apply the concepts you learned in that section to contexts beyond HDX-treme.<br />

ditional 30-second spots, these ads allow consumers to research<br />

products before buying them or simply to learn something new. Kraft,<br />

for instance, offered 20 different cooking videos creating meals using<br />

Pricing, Break-Even, and Margin Analysis its products. And Pioneer sponsored a four-minute video ad on the<br />

ins and outs of buying a plasma-screen high-definition television.<br />

Pricing Considerations<br />

Interestingly, a recent study found that DVR users aren’t necessarily<br />

skipping all the ads. According to the study, 55 percent of DVR<br />

users take their finger off the fast-forward button to watch a commer-<br />

Determining price is one of the most important marketing mix decisions, and marketers<br />

cial that is entertaining or relevant, sometimes even watching it more<br />

have considerable leeway when setting prices. The limiting factors are demand and costs.<br />

than once. “If advertising is really entertaining, you don’t zap it,” notes<br />

Demand factors, such as buyer perceived value, set the price ceiling. The company’s costs<br />

an industry observer. “You might even go out of your way to see it.”<br />

set the price floor. In between these two factors, marketers must consider competitors’<br />

Beyond making their regular ads more entertaining, advertisers<br />

prices and other factors such as reseller requirements, government regulations, and com-<br />

are also creating new advertising forms that look less like ads and<br />

pany objectives.<br />

more like short films or shows. For example, as part of a $100 million<br />

Current competing high-definition DVD products in this relatively new product category<br />

campaign to introduce its Sunsilk line of hair care products in the Welcome to Madison & Vine. As this book cover suggests, in today’s<br />

were introduced in 2006 and sell at retail prices between $500 and $1,200. HDX-treme plans<br />

United States, Unilever is producing a series of two-minute short pro- cluttered advertising environment, Madison Avenue must find new ways<br />

to introduce its new product at a lower price in order to expand the market and to gain margrams<br />

that resemble sitcom episodes more than ads.<br />

to engage ad-weary consumers with more compelling messages. The<br />

ket share rapidly. We first consider HDX-treme’s pricing decision from a cost perspective.<br />

answer? Entertainment!<br />

Then, we consider consumer value, the competitive environment, and reseller requirements. The series, titled “Sunsilk Presents Max and Katie,” will run on<br />

the TBS cable network. The miniepisodes present a humorous<br />

Fixed costs<br />

Costs that do not vary with<br />

production or sales level.<br />

Determining Costs<br />

Recall from Chapter 10 that there are different types of costs. Fixed costs do not vary with production<br />

or sales level and include costs such as rent, interest, depreciation, and clerical and<br />

management salaries. Regardless of the level of output, the company must pay these costs.<br />

Whereas total fixed costs remain constant as output increases, the fixed cost per unit (or average<br />

fixed cost) will decrease as output increases because the total fixed costs are spread across<br />

look at the hectic life of a 20-something woman—not coincidentally,<br />

the Sunsilk target audience. In all, Unilever will produce<br />

85 miniepisodes of “Max and Katie,” with 65 intended<br />

for TBS and the rest to be available online, on cell phones,<br />

through e-mail, and at displays in stores. The woman at whom<br />

Sunsilk will be aimed “has grown up being marketed to her<br />

whole life,” says a Unilever marketing manager. “She’s open to<br />

advertising, if it’s entertaining to her.”<br />

Similarly, Procter & Gamble produced a series of 90-second advertising<br />

sitcoms called “At the Poocherellas,” shown on Nick at Night,<br />

featuring a family of dogs and promoting its Febreze brand. Each<br />

miniepisode includes the expected commercial break, which lasts<br />

A-11<br />

Execution style<br />

The approach, style, tone,<br />

words, and format used for<br />

executing an advertising<br />

message.<br />

MESSAGE EXECUTION The advertiser now must turn the big idea into an actual ad execution<br />

that will capture the target market’s attention and interest. The creative team must find the<br />

best approach, style, tone, words, and format for executing the message. Any message can be<br />

presented in different execution styles, such as the following:<br />

■ Slice of life: This style shows one or more “typical” people using the product in a normal setting.<br />

For example, two mothers at a picnic discuss the nutritional benefits of Jif peanut butter.<br />

port marketing decisions in this<br />

age of marketing accountability.<br />

The Return on <strong>Marketing</strong> section<br />

in Chapter 2 has also been<br />

revised, and we’ve added return<br />

on advertising and return on selling<br />

discussions in later chapters.<br />

■ Chapter 9 contains a new section<br />

on managing new-product<br />

development, covering new<br />

■<br />

customer-driven, team-based,<br />

holistic new-product development<br />

approaches.<br />

Chapter 5 (Consumer Behavior)<br />

provides a new discussion on<br />

“online social networks” that<br />

tells how marketers are tapping<br />

digital online networks such as<br />

YouTube, MySpace, and others<br />

to build stronger relationships<br />

between<br />

customers.<br />

their brands and<br />

The twelfth edition also includes new and expanded material on a wide range of other<br />

topics, including managing customer relationships and CRM, brand strategy and positioning,<br />

SWOT analysis, data mining and data networks, ethnographic consumer research, marketing<br />

and diversity, generational marketing, buzz marketing, services marketing, supplier satisfaction<br />

and partnering, environmental sustainability, cause-related marketing, socially responsible<br />

marketing, global marketing strategies, and much, much more.<br />

Countless new examples have been added within the running text. All tables, examples,<br />

and references throughout the text have been thoroughly updated. The twelfth edition of<br />

Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong> contains mostly new photos and advertisements that illustrate key<br />

points and make the text more effective and appealing. All new or revised company cases and<br />

many new video cases help to bring the real world directly into the classroom. The text even<br />

has a new look, with freshly designed figures. We don’t think you’ll find a fresher, more current,<br />

or more approachable text anywhere.<br />

Real Value through Real <strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Preface xxiii<br />

Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong> features in-depth, real-world examples and stories that show concepts in<br />

action and reveal the drama of modern marketing. In the twelfth edition, every chapter-opening<br />

vignette and Real <strong>Marketing</strong> highlight has been updated or replaced to provide fresh and relevant<br />

insights into real marketing practices. Learn how:<br />

■ NASCAR creates avidly loyal fans by selling not just stock car racing but a high-octane,<br />

totally involving experience<br />

■ Best Buy builds the right relationships with the right customers by going out of its way to<br />

attract and keep profitable “angel” customers while exorcizing unprofitable “demons”<br />

■ Nike’s “Just do it!” marketing strategy has matured as this venerable market leader has moved<br />

from maverick to mainstream

xxiv Preface<br />

chapter<br />

7<br />

Previewing the Concepts<br />

So far, you’ve learned what marketing is<br />

and about the importance of understanding<br />

consumers and the marketplace environment.<br />

With that as background, you’re<br />

now ready to delve deeper into marketing<br />

strategy and tactics. This chapter looks<br />

further into key customer-driven marketing<br />

strategy decisions—how to divide up<br />

markets into meaningful customer groups<br />

(segmentation), choose which customer<br />

groups to serve (targeting), create market<br />

offerings that best serve target customers<br />

(differentiation), and position the offerings<br />

in the minds of consumers (positioning).<br />

Customer-Driven<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> Strategy<br />

Creating Value<br />

for Target Customers<br />

L<br />

■ Harrah’s, the world’s largest casino operator, maintains a vast customer database and uses<br />

CRM to manage day-to-day customer relationships and build customer loyalty<br />

■ Dunkin’ Donuts targets the “Dunkin’ Tribe”—not the Starbucks snob but the average Joe<br />

Part 3: Designing a Customer-Driven <strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Strategy and Integrated <strong>Marketing</strong> Mix<br />

ast year, Dunkin’ Donuts paid dozens of faithful customers in Phoenix,<br />

Chicago, and Charlotte, North Carolina, $100 a week to buy coffee at<br />

Starbucks instead. At the same time, the no-frills coffee chain paid Starbucks<br />

customers to make the opposite switch. When it later debriefed the two groups, Dunkin’<br />

says it found them so polarized that company researchers dubbed them “tribes”—<br />

each of whom loathed the very things that made the other tribe loyal to their coffee<br />

shop. Dunkin’ fans viewed Starbucks as pretentious and trendy, whereas Starbucks loyalists<br />

saw Dunkin’ as plain and unoriginal. “I don’t get it,” one Dunkin’ regular told<br />

researchers after visiting Starbucks. “If I want to sit on a couch, I stay at home.”<br />

William Rosenberg opened the first Dunkin’ Donuts in Quincy, Massachusetts, in<br />

1950. Residents flocked to his store each morning for the coffee and fresh doughnuts.<br />

Rosenberg started franchising the Dunkin’ Donuts name, and the chain grew<br />

rapidly throughout the Midwest and Southeast. By the early 1990s, however,<br />

Dunkin’ was losing breakfast sales to morning sandwiches at McDonald’s and<br />

Then, the chapters that follow explore<br />

the tactical marketing tools—the Real Four<strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Burger King. Starbucks Staples: and other high-end Positioning cafes began Made sprouting up, bringing more<br />

competition. Sales slid as the company clung to its strategy of selling sugary dough-<br />

Ps—by which marketers bring these strategies<br />

to life.<br />

These days, nuts by Staples the dozen. really is riding the easy button. But<br />

As an opening example of7.2 only five years In the ago, mid-1990s, things weren’t however, so easy Dunkin’ for the office- shifted its focus from doughnuts to coffee in<br />

segmentasupply<br />

superstore—or the for hope its customers. that promoting The ratio a more of customer frequently comconsumed<br />

item would drive store traffic.<br />

tion, targeting, differentiation, plaints and posi- to compliments was running an abysmal eight to one at<br />

The coffee push worked—coffee now makes up 62 percent of sales. And Dunkin’s<br />

tioning at work, let’s look at Staples Dunkin’ stores. The company’s slogan—“Yeah, we’ve got that”—had<br />

sales are growing at a double-digit clip, with profits up 35 percent over the past two<br />

Donuts. Dunkin’, a largely Eastern become U.S. laughable. Customers griped that items were often out of<br />

years. Based on this recent success, Dunkin’ now has ambitious plans to expand<br />

coffee chain, has ambitiousstock plans and said to the sales staff was unhelpful to boot.<br />

After weeks of into focus a groups national and coffee interviews, powerhouse, Shira Goodman, on a par with Starbucks, the nation’s largest cof-<br />

expand into a national powerhouse, on a<br />

Staples’ executive VP fee for chain. marketing, Over the had next a revelation. three years, “Customers Dunkin’ plans to remake its nearly 5,000 U.S.<br />

par with Starbucks. But Dunkin’ wanted isan no easier shopping experience,” she says. That simple reve-<br />

stores and to grow to triple that number in less than 15 years.<br />

Starbucks. In fact, it doesn’t want lation tohas be. resulted It in one of the most successful marketing cam-<br />

But Dunkin’ is not Starbucks. In fact, it doesn’t want to be. To succeed, it must<br />

targets a very different kind of paigns customer in recent history, built around the now-familiar “Staples: That<br />

was easy” tagline. But have Staples’ its own positioning clear vision turnaround of just took which a lot customers more it wants to serve (what segments<br />

with a very different value proposition.<br />

than simply bombarding and targeting) customers and with how a new (what slogan. positioning Before it or value proposition). Dunkin’ and<br />

Grab yourself some coffee and read could on. promise customers a simplified shopping experience, Staples<br />

Starbucks target very different customers, who want very different things from their<br />

had to actually deliver one. First, it had to live the slogan.<br />

When it launched<br />

favorite<br />

in 1986,<br />

coffee<br />

Staples<br />

shop.<br />

all<br />

Starbucks<br />

but invented<br />

is strongly<br />

the office-<br />

positioned as a sort of high-brow “third<br />

supply superstore. place”—outside Targeting small and the medium-size home and businesses, office—featuring it couches, eclectic music, wireless<br />

aimed to sell everything Internet for the access, office under and one art-splashed roof. But by walls. the mid- Dunkin’ has a decidedly more low-brow,<br />

1990s, the marketplace “everyman” was crowded kind of with positioning. retailers such as Office<br />

Depot, not to mention Target, Wal-Mart, and a slew of other online<br />

With its makeover, Dunkin’ plans to move upscale—a bit but not too far—to<br />

and offline sellers. Partly as a result of that competition, Staples’<br />

same-store sales fell rebrand for the first itself time as in a quick 2001. but appealing alternative to specialty coffee shops and fast-<br />

Customer research food chains. conducted A prototype by Goodman Dunkin’ and store her in team Euclid, Ohio, outside Cleveland, features<br />

revealed that although shoppers expected Staples and its competitors<br />

to have everything in stock, they placed little importance on<br />

price. Instead, customers overwhelmingly requested a simple,<br />

182<br />

straightforward shopping experience. “They wanted knowledgeable<br />

and helpful associates and hassle-free shopping,” Goodman says.<br />

The “Staples: That was easy” tagline was the simple—yet inspired—<br />

outgrowth of that realization.<br />

The slogan, however, was kept under wraps until the company<br />

could give its stores a major makeover. Staples removed from its inventory<br />

some 800 superfluous items, such as Britney Spears backpacks,<br />

that had little use in the corporate world. Office chairs, which had been<br />

displayed in the rafters, were moved to the floor so customers could try The “Staples: That was easy” marketing campaign has played a major<br />

them out. Staples also added larger signs and retrained sales associ- role in repositioning Staples. But marketing promises count for little if<br />

ates to walk shoppers to the correct aisle. Because customers revealed not backed by the reality of the customer experience.<br />

that the availability of ink was one of their biggest concerns, the company<br />

introduced an in-stock guarantee on printer cartridges. Even The Easy Button soon birthed a string of humorous and popular<br />

communications were simplified—a four-paragraph letter sent to television commercials, which premiered in January 2005 and also<br />

prospective customers was cut to two sentences.<br />

aired during the Super Bowl a month later. In one spot, called “The<br />

Only when all of the customer-experience pieces were in place did Wall,” an emperor uses the button to erect a giant barrier as maraud-<br />

Staples begin communicating its new positioning to customers. It ers approach; another shows an office worker causing printer car-<br />

took about a year to get the stores up to snuff, Goodman says, but tridges to rain down from above. Online, Staples created a download-<br />

“once we felt that the experience was significantly easier, we able Easy Button toolbar, which took shoppers directly from their<br />

changed the tagline.”<br />

desktops to Staples.com, and billboards reminded commuters that<br />

For starters, the company hired a new ad agency, McCann- an Easy Button would be helpful in snarled traffic.<br />

Erickson Worldwide, which had also created MasterCard’s nine-year- As a result of the advertising onslaught, customers began asking<br />

old “Priceless” campaign. A group of McCann copywriters and art about buying real Easy Buttons, so Staples again took the cue. It<br />

directors held a marathon brainstorming session to find ways to illus- began selling $5 three-inch red plastic buttons that when pushed say<br />

trate the concept of “easy.” As the creative session dragged on, the “That was easy.” Staples promised to donate $1 million in button<br />

group’s creative director mentioned how nice it would be if she could profits to charity each year, and by mid-2006, it had sold its millionth<br />

just push a button to come up with a great ad, so they could go to button. By selling the Easy Button as a sort of modern-day stress ball,<br />

lunch. The Easy Button was born. “It took an amorphous concept Staples has turned its customers into advertisers. Homegrown<br />

and made it tangible,” Goodman says.<br />

movies starring the button have appeared on video-sharing site<br />

(continues)<br />

rounded granite-style coffee bars, where workers make espresso drinks face-to-face<br />

with customers. Open-air pastry cases brim with yogurt parfaits and fresh fruit, and<br />

a carefully orchestrated pop-music soundtrack is piped throughout.<br />

Yet Dunkin’ built itself on serving simple fare to working-class customers. Inching<br />

upscale without alienating that base will prove tricky. There will be no couches in the<br />

new stores. And Dunkin’ renamed a new hot sandwich a “stuffed melt” after customers<br />

complained that calling it a “panini” was too fancy. “We’re walking that [fine]<br />

line,” says Regina Lewis, the chain’s vice president of consumer insights. “The thing<br />

about the Dunkin’ tribe is, they see through the hype.”<br />

Dunkin’s research showed that although loyal Dunkin’ customers want nicer<br />

stores, they were bewildered and turned off by the atmosphere at Starbucks. They<br />

groused that crowds of laptop users made it difficult to find a seat. They didn’t like<br />

Starbucks’ “tall,” “grande,” and “venti” lingo for small, medium, and large coffees.<br />

And they couldn’t understand why anyone would pay as much as $4 for a cup of<br />

coffee. “It was almost as though they were a group of Martians talking about a group<br />

of Earthlings,” says an executive from Dunkin’s ad agency. One customer told<br />

researchers that lingering in a Starbucks felt like “celebrating Christmas with people<br />

you don’t know.” The Starbucks customers that Dunkin’ paid to switch were equally<br />

uneasy in Dunkin’ shops. “The Starbucks people couldn’t bear that they weren’t<br />

special anymore,” says the ad executive.<br />

Valuable Learning Aids<br />

Objectives<br />

After studying this chapter, you should<br />

be able to<br />

1. define the four major steps in designing a<br />

customer-driven market strategy: market<br />

segmentation, market targeting,<br />

differentiation, and positioning<br />

2. list and discuss the major bases for<br />

segmenting consumer and business markets<br />

3. explain how companies identify attractive<br />

market segments and choose a market<br />

targeting strategy<br />

4. discuss how companies position their<br />

products for maximum competitive<br />

advantage in the marketplace<br />

■ Tiny nicher Bike Friday creates<br />

customer evangelists—<br />

delighted customers who<br />

can’t wait to tell others<br />

about the company<br />

■ Apple Computer founder<br />

■<br />

Steve Jobs used dazzling customer-<br />

driven innovation to<br />

first start the company and<br />

then to remake it again 20<br />

years later<br />

Staples held back its nowfamiliar<br />

“Staples: That was<br />

easy” repositioning campaign<br />

for more than a year.<br />

First, it had to live the slogan.<br />

■ Ryanair—Europe’s original,<br />

largest, and most profitable<br />

low-fares airline—appears<br />

to have found a radical new<br />

pricing solution: Fly free!<br />

■ The NBA has become one of today’s hottest global brands, jamming<br />

down one international slam dunk after another<br />

■ Dove—with its Campaign for Real Beauty campaign featuring<br />

candid and confident images of real women of all types—is<br />

on a bold mission to create a broader and healthier view of<br />

beauty<br />

These and countless other examples and illustrations throughout<br />

each chapter reinforce key concepts and bring marketing to life.<br />

A wealth of chapter-opening, within-chapter, and end-of-chapter learning devices help students<br />

to learn, link, and apply major concepts:<br />

■ Previewing the Concepts. A section at the beginning of each chapter briefly previews<br />

chapter concepts, links them with previous chapter concepts, outlines chapter learning<br />

objectives, and introduces the chapter-opening vignette.<br />

■ Chapter-opening marketing stories. Each chapter begins with an engaging, deeply developed<br />

marketing story that introduces the chapter material and sparks student interest.<br />

■ Real <strong>Marketing</strong> highlights. Each chapter contains two highlight features that provide an<br />

in-depth look at real marketing practices of large and small companies.<br />

■ Reviewing the Concepts. A summary at the end of each chapter reviews major chapter<br />

concepts and chapter objectives.<br />

■ Reviewing the Key Terms. Key terms are highlighted within the text, clearly defined<br />

in the margins of the pages in which they first appear, and listed at the end of each<br />

chapter.<br />

■ Discussing the Concepts and Applying the Concepts. Each chapter contains a set of discussion<br />

questions and application exercises covering major chapter concepts.<br />

■ Focus on Technology. Application exercises at the end of each chapter provide discussion<br />

on important and emerging marketing technologies in this digital age.<br />

■ Focus on Ethics. Situation descriptions and questions highlight important issues in marketing<br />

ethics at the end of each chapter.<br />

183

Company Case Saturn: An Image Makeover<br />

Things are about to change at Saturn. The General Motors From the beginning, Saturn set out to break through the<br />

brand had only three iterations of the same compact car for GM bureaucracy and become “A different kind of car. A dif-<br />

the entire decade of the 1990s. But Saturn will soon introferent kind of company.” As the single-most defining charduce<br />

an all-new lineup of vehicles that includes a midacteristic of the new company, Saturn proclaimed that its<br />

sized sport sedan, an eight-passenger crossover vehicle, a sole focus would be people: customers, employees, and<br />

two-seat roadster, a new compact, and a hybrid SUV. communities. Saturn put significant resources into cus-<br />

Having anticipated the brand’s renaissance for years, Saturn tomer research and product development. The first Saturn<br />

executives, employees, and customers are beside themg<br />

cars were g made “from gscratch,”<br />

without any allegiance to<br />

selves with glee.<br />

the GM parts bin or suppliers. The goal was to produce not<br />

But with all this change, industry observers are wonder- only a high-quality vehicle, but one known for safety and<br />

ing whether Saturn will be able to maintain the very charac- innovative features that would “wow” the customer.<br />

teristics that have distinguished the Video brand since Case its incep- Harley-Davidson<br />

Saturn’s focus on employees began with an unprecetion.<br />

Given that Saturn established itself based on a very dented contract with United Auto Workers (UAW). The con-<br />

Few brands engender such intense loyalty as that found in the hearts of<br />

narrow line of compact vehicles, many believe that the tract was so simple, it fit in a shirt Harley’s pocket. Web It established site, customers pro- can book a trip to Milwaukee to visit the<br />

Harley-Davidson owners. Why? Because the company’s marketers spend<br />

move from targeting one segment of customers to targeting gressive work rules, with special Harley factory emphasis in the company’s given tohometown<br />

or turn a Las Vegas vacation<br />

a great deal of time thinking about customers. They want to know who<br />

multiple segments will be challenging. Will a newly posi- benefits, work teams, and the concept into “an of authentic empowerment. Harley-Davidson At adventure.”<br />

their customers are, how they think and feel, and why they buy a Harley.<br />

tioned Saturn still meet the needs of one of the most loyal the retail end, Saturn selected dealers After viewing based the on video carefully featuring Harley-Davidson, answer the follow-<br />

That attention to detail has helped build Harley-Davidson into a $5 billion<br />

cadres of customers in the automotive world?<br />

crafted criteria. It paid service personnel ing questions and about sales marketing associ- strategy.<br />

company with more than 900,000 Harley Owners Group (HOG) members<br />

ates a salary rather than commission. 1. List This several would products help that creare<br />

included in Harley-Davidson’s busi-<br />

and 1,200 dealerships worldwide.<br />

A NEW KIND OF CAR COMPANY<br />

ate an environment that would reverse ness portfolio. the common Analyze cus- the portfolio using the Boston Consulting<br />

Harley sells much more than motorcycles. The company sells a feel-<br />

In 1980, GM recognized its inferiority to the Japanese big tomer perception of the dealer as a nemesis. Group growth-share matrix.<br />

ing of independence, individualism, and freedom. To support that<br />

three (Honda, Toyota, and Datsun) with respect to compact Finally, in addition to customer and employee relations,<br />

lifestyle, Harley-Davidson offers clothes and accessories both for riders 2. Which strategies in the product/market expansion grid is Harleyvehicles.<br />

The Japanese had a lower cost structure, yet built Saturn focused on social responsibility. Human resources<br />

and those who simply like to associate with the brand. Harley further Davidson using to grow sales and profits?<br />

better cars. In an effort to offer a more competitive economy policies gave equal opportunities to women, ethnic minori-<br />

extends the brand experience by offering travel adventures. Through 3. List some of the members of Harley’s value-delivery network.<br />

car, GM actually turned to the enemy. It entered into a joint ties, and people with disabilities. Saturn designed environ-<br />

venture with Toyota to build small cars. Soon, a Toyota mentally responsible manufacturing processes, even going<br />

plant in Northern Focus California on Technology<br />

was turning out Corollas on beyond legal requirements. The company also gave heavy<br />

one assembly line while making very similar Chevy Novas philanthropic support to various causes. All of these actions<br />

on a Television second. is Meanwhile, hitting the small in a screen—the long-term mobile effort phones to make that better more than earned 1. Saturn Explain a why number younger of Gen awards Yers might recognizing be more likely its environ- to adapt new<br />

small 80 cars, percent GM gave of adults the green now carry. light to Networks Group 99, are a now secretive producing mentally mobile and socially phone technologies responsible as actions. compared to other demographic<br />

task “mobisodes,” force that two-minute resulted episodes in formation produced of exclusively the Saturn for mobile groups.<br />

Corporation phones. Services in 1985. such as Verizon’s Vcast let you watch TV or stream con-<br />

(case continues)<br />

2. What other macroenvironmental and microenvironmental forces<br />

tent for a monthly fee. Who will subscribe to this? Certainly the younger might affect the growth of mobile TV?<br />

segment of the Generation Y demographic—the growing 57 percent of<br />

3. How can other marketers use mobile marketing to communicate<br />

U.S. teens, ages 13 to 17 years, who now own mobile phones. Although<br />

with and promote to consumers?<br />

this is below the percentage of all adults owning mobile phones, this<br />

group displays the most intense connectivity to their phones and the most<br />

interest in new features.<br />

Focus on Ethics<br />

In February, 2005, R.J. Reynolds began a promotion that included direct- public advocacy groups, and the alcohol distillers themselves. The attormail<br />

pieces to young adults on their birthdays. The campaign, entitled ney generals and advocacy groups said the promotion endorsed heavy<br />

“Drinks on Us,” included a birthday greeting as well as a set of drink drinking. The distillers were angry because their brands were used with-<br />

coasters that included recipes for many drinks. The drink recipes, which out permission. In addition, the distillers argued that the promotion vio-<br />

were for mixed drinks of high alcohol content, included many distiller lates the alcohol industry advertising code, which prohibits marketing that<br />

brands such as Jack Daniels, Southern Comfort, and Finlandia Vodka. encourages excessive drinking.<br />

With the recipe on one side of the coaster, the flip side included a tag line 1. What prominent environmental forces come into play in this situation?<br />

such as “Go ’til Daybreak, and Make Sure You’re Sittin.” Shortly after its<br />

2. Is this promotion wrong? Should R.J. Reynolds stop the promotion?<br />

release, the promotion came under attack from several attorney generals,<br />

■ Company Cases. All new or revised company cases for class or written<br />

discussion are provided at the end of each chapter. These cases<br />

challenge students to apply marketing principles to real companies in<br />

real situations.<br />

■ Video Shorts. Short vignettes and discussion questions appear<br />

at the end of every chapter, to be used with the set of 4- to 7minute<br />

videos that accompany this edition.<br />

■ <strong>Marketing</strong> Plan appendix. Appendix 1 contains a sample marketing<br />

plan that helps students to apply important marketing<br />

planning concepts.<br />

■ <strong>Marketing</strong> by the Numbers appendix. A new Appendix 2 introduces students<br />

to the marketing financial analysis that helps to guide, assess, and<br />

support marketing decisions.<br />

More than ever before, the twelfth edition of Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong> creates<br />

value for you—it gives you all you need to know about marketing in<br />

an effective and enjoyable totallearning package!<br />

A Valuable Supplements Package<br />

A successful marketing course requires more than a well-written book. Today’s classroom<br />

requires a dedicated teacher and a fully integrated teaching system. A total package of teaching<br />

and learning supplements extends this edition’s emphasis on creating value for both the<br />

student and instructor. The following aids support Principles of <strong>Marketing</strong>.<br />

Supplements for Instructors<br />

The following supplements are available to adopting instructors.<br />

Instructor’s Manual with Video Case Notes (ISBN: 0-13-239003-5)<br />

The instructor’s handbook for this text provides suggestions for using features and elements of<br />

the text. This Instructor’s Manual includes a chapter overview, objectives, a detailed lecture<br />

outline (incorporating key terms, text art, chapter objectives, and references to various pedagogical<br />

elements), and support for end-of-chapter material. Also included within each chapter<br />

is a section that offers barriers to effective learning, student projects/assignments, as well<br />

as an outside example, all of which provide a springboard for innovative learning experiences<br />

in the classroom. Video Case Notes, offering a brief summary of each segment, along with<br />

answers to the case questions in the text, as well as teaching ideas on how to present the material<br />

in class are also offered in the Instructor’s Manual.<br />

Visit the Instructor’s Resource Center Online (www.prenhall.com/irc) for these addtional<br />

elements:<br />

■ “Professors on the Go!” serves to bring key material upfront in the manual, where an<br />

instructor who is short on time can take a quick look and find key points and assignments<br />

to incorporate into the lecture, without having to page through all the material provided<br />

for each chapter.<br />

■ Annotated Instructor’s Notes, which serve as a quick reference for the entire supplements<br />

package. Suggestions for using materials from the Instructor’s Manual, PowerPoint slides,<br />

Test Item File, Video Library, and online material are offered for each section within every<br />

chapter.<br />

■ More Quantitative Exercises, based on the concepts covered in Appendix 2: <strong>Marketing</strong> by<br />

the Numbers. An additional set of exercises are offered here, not found in the textbook.<br />

Suggested answers are provided as well.<br />

Test Item File (ISBN: 0-13-239004-3)<br />

Preface xxv<br />

Featuring more than 3,000 questions, 175 questions per chapter, this Test Item File has been<br />

written specifically for the twelfth edition. Each chapter consists of multiple-choice, true/false,

chapter<br />

Previewing the Concepts<br />

478<br />

17<br />

In the previous three chapters, you<br />

learned about communicating customer<br />

value through integrated marketing communication<br />

(IMC) and about four specific<br />

elements of the marketing communications<br />

mix—advertising, publicity, personal<br />

selling, and sales promotion. In this<br />

chapter, we’ll look at the final IMC element,<br />

direct marketing, and at its fastestgrowing<br />

form, online marketing. Actually,<br />

direct marketing can be viewed as more<br />

than just a communications tool. In many<br />

ways it constitutes an overall marketing<br />

approach—a blend of communication and<br />

distribution channels all rolled into one.<br />

As you read on, remember that although<br />

this chapter examines direct marketing as<br />

a separate tool, it must be carefully integrated<br />

with other elements of the promotion<br />

mix.<br />

To set the stage, let’s first look at Dell,<br />

the world’s largest direct marketer of<br />

computer systems and the number-one PC<br />

maker worldwide. Ask anyone at Dell and<br />

they’ll tell you that the company owes its<br />

incredible success to what it calls the Dell<br />

Direct Model, a model that starts with<br />

direct customer relationships and ends<br />

with the Dell customer experience. Says<br />

one analyst, “There’s no better way to<br />

make, sell, and deliver PCs than the way<br />

Dell does it, and nobody executes [the<br />

direct] model better than Dell.”<br />

Direct and Online<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Building Direct Customer<br />

Relationships<br />

When 19-year-old Michael Dell began selling personal computers out of<br />

his college dorm room in 1984, competitors and industry insiders<br />

scoffed at the concept of direct computer marketing. Yet young Michael<br />

proved the skeptics wrong—way wrong. In little more than two decades, he has<br />

turned his dorm-room mail-order business into the burgeoning, $56 billion Dell<br />

computer empire.<br />

Dell is now the world’s largest direct marketer of computer systems and the<br />

number-one PC maker worldwide. In the United States, Dell is number-one in desktop<br />

PC sales, number-one in laptops, number-one in servers, and number-two (and<br />

gaining) in printers. In fact, Dell flat out dominates the U.S. PC market, with a<br />

33.5 percent market share, compared with number-two HP’s 19.4 percent and<br />

number-three Gateway’s 6.1 percent. Dell has produced a ten-year average annual<br />

return to investors of 39 percent, best among all Fortune 100 companies. Investors<br />

have enjoyed explosive share gains of more than 28,000 percent since Dell went<br />

public fewer than 20 years ago.<br />

What’s the secret to Dell’s stunning success? Anyone at Dell can tell you without<br />

hesitation: It’s the company’s radically different business model—the direct model.<br />

“We have a tremendously clear business model,” says Michael Dell, the company’s<br />

41-year-old founder and chairman. “There’s no confusion about what the value<br />

proposition is, what the company offers, and why it’s great for customers.” An industry<br />

analyst agrees: “There’s no better way to make, sell, and deliver PCs than the way<br />

Dell does it, and nobody executes [the direct] model better than Dell.”<br />

Dell’s direct-marketing approach delivers greater customer value through an<br />

unbeatable combination of product customization, low prices, fast delivery, and<br />

award-winning customer service. A customer can talk by phone with a Dell representative<br />

at 1-800-Buy-Dell or log onto www.dell.com on Monday morning; order a<br />

fully customized, state-of-the-art PC to suit his or her special needs; and have the<br />

machine delivered to his or her doorstep or desktop by Wednesday—all at a price<br />

that’s well below competitors’ prices for a comparably performing PC. Dell backs its<br />

products with high-quality service and support. As a result, Dell consistently ranks<br />

among the industry leaders in product reliability and service, and its customers are<br />

routinely among the industry’s most satisfied.<br />

Dell customers get exactly the machines they need. Michael Dell’s initial idea was<br />

to serve individual buyers by letting them customize machines with the special features<br />

they wanted at low prices. However, this one-to-one approach also appeals<br />

strongly to corporate buyers, because Dell can so easily preconfigure each computer

to precise requirements. Dell routinely preloads machines with a company’s own<br />

software and even undertakes tedious tasks such as pasting inventory tags onto<br />

each machine so that computers can be delivered directly to a given employee’s<br />

desk. As a result, more than 85 percent of Dell’s sales come from business, government,<br />

and educational buyers.<br />

The direct model results in more efficient selling and lower costs, which translate<br />

into lower prices for customers. “Nobody, but nobody, makes [and markets]<br />

computer hardware more efficiently than Dell,” says another analyst. “No unnecessary<br />

costs: This is an all-but-sacred mandate of the famous Dell direct business<br />

model.” Because Dell builds machines to order, it carries barely any inventory—<br />

less than three days’ worth by some accounts. Dealing one-to-one with customers<br />

helps the company react immediately to shifts in demand, so Dell doesn’t get stuck<br />

with PCs no one wants. Finally, by selling directly, Dell has no dealers to pay. As a<br />

result, on average, Dell’s costs are 12 percent lower than those of its leading PC<br />

competitor.<br />

Dell knows that time is money, and the company is obsessed with “speed.”<br />

According to one account, Dell squeezes “time out of every step in the process—<br />

from the moment an order is taken to collecting the cash. [By selling direct, manufacturing<br />

to order, and] tapping credit cards and electronic payment, Dell converts<br />

the average sale to cash in less than 24 hours.” By contrast, competitors selling<br />

through dealers might take 35 days or longer.<br />

Objectives<br />

After studying this chapter, you should<br />

be able to<br />

1. define direct marketing and discuss its<br />

benefits to customers and companies<br />

2. identify and discuss the major forms of<br />

direct marketing<br />

3. explain how companies have responded to<br />

the Internet and other powerful new<br />

technologies with online marketing<br />

strategies<br />

4. discuss how companies go about conducting<br />

online marketing to profitably deliver more<br />

value to customers<br />

5. overview the public policy and ethical issues<br />

presented by direct marketing<br />

479

480 Part 3 Designing a Customer-Driven <strong>Marketing</strong> Strategy and Integrated <strong>Marketing</strong> Mix<br />

Direct marketing<br />

Direct connections with<br />

carefully targeted individual<br />

consumers to both obtain an<br />

immediate response and<br />

cultivate lasting customer<br />

relationships.<br />

Such blazing speed results in more satisfied customers and still lower costs. For example, customers<br />

are often delighted to find their new computers arriving within as few as 36 hours of placing an order.<br />

And because Dell doesn’t order parts until an order is booked, it can take advantage of ever-falling component<br />

costs. On average, its parts are 60 days newer than those in competing machines, and, hence,<br />

60 days farther down the price curve. This gives Dell a 6 percent profit advantage from parts costs alone.<br />

As you might imagine, competitors are no longer scoffing at Michael Dell’s vision of the future. In<br />

fact, competing and noncompeting companies alike are studying the Dell direct model closely.<br />

“Somehow Dell has been able to take flexibility and speed and build it into their DNA. It’s almost like<br />

drinking water,” says the CEO of another Fortune 500 company, who visited recently to absorb some<br />

of the Dell magic to apply to his own company. “I’m trying to drink as much water here as I can.”<br />

Still, as Dell grows larger and as the once-torrid growth in the sales of PCs slows, the Dell direct<br />

model is facing challenges. After years of rocketing revenue and profit numbers, Dell’s recent growth<br />

has slowed. Although Dell still dominates in selling PCs, servers, and peripherals to business markets,<br />

it appears to be stumbling in its attempts to sell an expanding assortment of high-tech consumer electronics<br />

products to final buyers. Some analysts suggest that Dell’s vaunted direct model may not work<br />

as well for selling LCD TVs, handhelds, MP3 players, digital cameras, and other personal digital<br />

devices—products that consumers want to see and experience first-hand before buying. In fact, Dell<br />

plans to add retail stores to help bolster the consumer side of its business.<br />

Slowing growth has led some analysts to ask, “Is the much-feared Dell Way running out of gas?” No<br />

way, says Dell. There’s no question, the company admits, that Dell isn’t the high-flying growth company<br />

it once was—you can’t expect a $56-billion-a-year giant to grow like a full-throttle start-up. But<br />

Dell continues to dominate its PC markets, and other companies would kill for Dell’s “disappointing”<br />

growth numbers—sales last year grew 13.6 percent, and profits were up 17.4 percent. “We still have<br />

an outrageous track record,” says Dell CEO Kevin Rollins. “Our [direct] model still works very well,”<br />

Michael Dell agrees. “We wouldn’t trade ours for anyone else’s!” he says. “In the past ten years our<br />

sales are up about 15 times, earnings and the stock price are up about 20 times. Not too shabby!”<br />

It’s hard to argue with success, and Michael Dell has been very successful. By following his<br />

hunches, at the tender age of 41 he has built one of the world’s hottest companies. In the process,<br />

he’s become one of the world’s richest men, amassing a personal fortune of more than $17 billion. 1<br />

Many of the marketing and promotion tools that we’ve examined in previous chapters were<br />

developed in the context of mass marketing: targeting broad markets with standardized messages<br />

and offers distributed through intermediaries. Today, however, with the trend toward<br />

more narrowly targeted marketing, many companies are adopting direct marketing, either as a<br />

primary marketing approach or as a supplement to other approaches. In this section, we<br />

explore the exploding world of direct marketing.<br />

Direct marketing consists of direct connections with carefully targeted individual consumers<br />

to both obtain an immediate response and cultivate lasting customer relationships.<br />

Direct marketers communicate directly with customers, often on a one-to-one, interactive<br />

basis. Using detailed databases, they tailor their marketing offers and communications to the<br />

needs of narrowly defined segments or even individual buyers.<br />

Beyond brand and relationship building, direct marketers usually seek a direct, immediate,<br />

and measurable consumer response. For example, as we learned in the chapter-opening<br />

story, Dell interacts directly with customers, by telephone or through its Web site, to design<br />

built-to-order systems that meet customers’ individual needs. Buyers order directly from Dell,<br />

and Dell quickly and efficiently delivers the new computers to their homes or offices.<br />

The New Direct-<strong>Marketing</strong> Model<br />

Early direct marketers—catalog companies, direct mailers, and telemarketers—gathered customer<br />

names and sold goods mainly by mail and telephone. Today, however, fired by rapid<br />

advances in database technologies and new marketing media—especially the Internet—direct

■ The new direct marketing<br />

model: Companies such as<br />

GEICO have built their entire<br />

approach to the marketplace<br />

around direct marketing: just<br />

visit geico.com or call 1-800-<br />

947-auto.<br />

Chapter 17 Direct and Online <strong>Marketing</strong>: Building Direct Customer Relationships 481<br />

marketing has undergone a dramatic transformation. According to the head of the Direct<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> Association, “In recent years, the dramatic growth of the Internet and the increasing<br />

sophistication of database technologies have [created] an extraordinary expansion of<br />

direct marketing and a seismic shift in what it is, how it’s used, and who uses it.” 2<br />

In previous chapters, we’ve discussed direct marketing as direct distribution—as marketing<br />

channels that contain no intermediaries. We also include direct marketing as one element<br />

of the promotion mix—as an approach for communicating directly with consumers. In actuality,<br />

direct marketing is both these things.<br />

Most companies still use direct marketing as a supplementary channel or medium for<br />

marketing their goods and messages. Thus, Lexus markets mostly through mass-media advertising<br />

and its high-quality dealer network but also supplements these channels with direct<br />

marketing. Its direct marketing includes promotional CDs and other materials mailed directly<br />

to prospective buyers and a Web page (www.lexus.com) that provides consumers with information<br />

about various models, competitive comparisons, financing, and dealer locations.<br />

Similarly, most department stores sell the majority of their merchandise off their store shelves<br />

but also sell through direct mail and online catalogs.<br />

However, for many companies today, direct marketing is more than just a supplementary<br />

channel or medium. For these companies, direct marketing—especially in its most recent<br />

transformation, online marketing—constitutes a complete model for doing business. More<br />

than just another marketing channel or advertising medium, this new direct model is rapidly<br />

changing the way companies think about building relationships with customers.<br />

Rather than using direct marketing and the Internet only as supplemental approaches,<br />

firms employing the direct model use it as the only approach. Companies such as Dell,<br />

Amazon.com, eBay, and GEICO have built their entire approach to the marketplace around<br />

direct marketing.<br />

Growth and Benefits of Direct <strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Direct marketing has become the fastest-growing form of marketing. According to the Direct<br />

<strong>Marketing</strong> Association, U.S. companies spent $161 billion on direct marketing last year,<br />

accounting for whopping 48 percent of total U.S. advertising expenditures. These expenditures<br />

generated an estimated $1.85 trillion in direct marketing sales, or about 7 percent of<br />

total sales in the U.S. economy. And direct marketing-driven sales are growing rapidly. The<br />

DMA estimates that direct marketing sales will grow 6.4 percent annually through 2009, compared<br />

with a projected 4.8 percent annual growth for total U.S. sales. 3

482 Part 3 Designing a Customer-Driven <strong>Marketing</strong> Strategy and Integrated <strong>Marketing</strong> Mix<br />

Direct marketing continues to become more Web oriented, and Internet marketing is<br />

claiming a fast-growing share of direct marketing spending and sales. The Internet now<br />

accounts for only about 16 percent of direct marketing-driven sales. However, the DMA predicts<br />

that over the next five years Internet marketing expenditures will grow at a blistering<br />

18 percent a year, three times faster than expenditures in other direct marketing media.<br />

Internet-driven sales will grow by 12.6 percent.<br />

Whether employed as a complete business model or as a supplement to a broader integrated<br />

marketing mix, direct marketing brings many benefits to both buyers and sellers.<br />

Benefits to Buyers<br />

For buyers, direct marketing is convenient, easy, and private. Direct marketers never close<br />

their doors, and customers don’t have to battle traffic, find parking spaces, and trek through<br />

stores to find products. From the comfort of their homes or offices, they can browse catalogs<br />

or company Web sites at any time of the day or night. Business buyers can learn about products<br />

and services without tying up time with salespeople.<br />

Direct marketing gives buyers ready access to a wealth of products. For example, unrestrained<br />

by physical boundaries, direct marketers can offer an almost unlimited selection to<br />

consumers almost anywhere in the world. For example, by making computers to order and<br />

selling directly, Dell can offer buyers thousands of self-designed PC configurations, many<br />

times the number offered by competitors who sell preconfigured PCs through retail stores. And<br />

just compare the huge selections offered by many Web merchants to the more meager assortments<br />

of their brick-and-mortar counterparts. For instance, log onto Bulbs.com, “the Web’s<br />

no. 1 light bulb superstore,” and you’ll have instant access to every imaginable kind of light<br />

bulb or lamp—incandescent bulbs, fluorescent bulbs, projection bulbs, surgical bulbs, automotive<br />

bulbs—you name it. No physical store could offer handy access to such a vast selection.<br />

Direct marketing channels also give buyers access to a wealth of comparative information<br />

about companies, products, and competitors. Good catalogs or Web sites often provide more<br />

information in more useful forms than even the most helpful retail salesperson can. For example,<br />

the Amazon.com site offers more information than most of us can digest, ranging from<br />

top-10 product lists, extensive product descriptions, and expert and user product reviews to<br />

recommendations based on customers’ previous purchases. And Sears catalogs offer a treasure<br />

trove of information about the store’s merchandise and services. In fact, you probably<br />

wouldn’t think it strange to see a Sears salesperson referring to a catalog in the store while trying<br />

to advise a customer on a specific product or offer.<br />

Finally, direct marketing is interactive and immediate—buyers can interact with sellers<br />

by phone or on the seller’s Web site to create exactly the configuration of information, products,<br />

or services they desire, and then order them on the spot. Moreover, direct marketing<br />

gives consumers a greater measure of control. Consumers decide which catalogs they will<br />

browse and which Web sites they will visit.<br />

Benefits to Sellers<br />

For sellers, direct marketing is a powerful tool for building customer relationships. Using<br />

database marketing, today’s marketers can target small groups or individual consumers and<br />

promote their offers through personalized communications. Because of the one-to-one nature<br />

of direct marketing, companies can interact with customers by phone or online, learn more<br />

about their needs, and tailor products and services to specific customer tastes. In turn, customers<br />

can ask questions and volunteer feedback.<br />

Direct marketing also offers sellers a low-cost, efficient, speedy alternative for reaching<br />

their markets. Direct marketing has grown rapidly in business-to-business marketing, partly in<br />

response to the ever-increasing costs of marketing through the sales force. When personal sales<br />

calls cost an average of more than $400 per contact, they should be made only when necessary<br />

and to high-potential customers and prospects. Lower-cost-per-contact media—such as telemarketing,<br />

direct mail, and company Web sites—often prove more cost effective. Similarly,<br />

online direct marketing results in lower costs, improved efficiencies, and speedier handling of<br />

channel and logistics functions, such as order processing, inventory handling, and delivery.<br />

Direct marketers such as Amazon.com or Dell also avoid the expense of maintaining a store<br />

and the related costs of rent, insurance, and utilities, passing the savings along to customers.<br />

Direct marketing can also offer greater flexibility. It allows marketers to make ongoing<br />

adjustments to its prices and programs, or to make immediate and timely announcements and

Chapter 17 Direct and Online <strong>Marketing</strong>: Building Direct Customer Relationships 483<br />

offers. For example, Southwest Airlines’ DING! application takes advantage of the flexibility<br />

and immediacy of the Web to share low-fare offers directly with customers: 4<br />

■ Southwest Airlines “DING!” application takes advantage of flexibility and<br />

immediacy of the Web to share low-fare offers directly with customers.<br />

Customer database<br />

An organized collection of<br />

comprehensive data about<br />

individual customers or<br />

prospects, including<br />

geographic, demographic,<br />

psychographic, and<br />

behavioral data.<br />

When Jim Jacobs hears a “ding” coming from his desktop computer, he thinks about<br />

discount air fares like the $122 ticket he recently bought for a flight from Tampa to<br />

Baltimore on Southwest Airlines.<br />

Several times a day, Southwest sends<br />

Jacobs and hundreds of thousands of<br />

other computer users discounts through<br />

an application called DING! “If I move<br />

quickly,” says Jacobs, a corporate<br />

telecommunications salesman who lives<br />

in Tampa, “I can usually save a lot of<br />

money.” The fare to Baltimore underbid<br />

the airline’s own Web site by $36, he<br />

says. DING! lets Southwest bypass the<br />

reservations system and pass bargain<br />

fares directly to interested customers.<br />

Eventually, DING! may even allow<br />

Southwest to customize fare offers based<br />

on each customer’s unique characteristics<br />

and travel preferences. For now,<br />

DING! gets a Southwest icon on the customer’s<br />

desktop and lets the airline build<br />

relationships with customers by helping<br />

them to save money. Following its DING!<br />

launch in early 2005, Southwest experienced<br />

its two biggest online sales days<br />

ever. In the first 13 months, two million<br />

customers downloaded DING! and the<br />

program produced more than $80 million<br />

worth of fares.<br />

Finally, direct marketing gives sellers access to buyers that they could not reach through<br />

other channels. Smaller firms can mail catalogs to customers outside their local markets and<br />

post 1-800 telephone numbers to handle orders and inquiries. Internet marketing is a truly<br />

global medium that allows buyers and sellers to click from one country to another in seconds.<br />

A Web surfer from Paris or Istanbul can access an online L.L. Bean catalog as easily as someone<br />

living in Freeport, Maine, the direct retailer’s hometown. Even small marketers find that<br />

they have ready access to global markets.<br />

Customer Databases and Direct <strong>Marketing</strong><br />

Effective direct marketing begins with a good customer database. A customer database is an<br />

organized collection of comprehensive data about individual customers or prospects, including<br />

geographic, demographic, psychographic, and behavioral data. A good customer database<br />

can be a potent relationship-building tool. The database gives companies “a snapshot of how<br />

customers look and behave.” Says one expert, “A company is no better than what it knows<br />

[about its customers].” 5<br />

Many companies confuse a customer database with a customer mailing list. A customer<br />

mailing list is simply a set of names, addresses, and telephone numbers. A customer database<br />

contains much more information. In consumer marketing, the customer database might contain<br />

a customer’s demographics (age, income, family members, birthdays), psychographics<br />

(activities, interests, and opinions), and buying behavior (buying preferences and the recency,<br />

frequency, and monetary value—RFM—of past purchases). In business-to-business marketing,<br />

the customer profile might contain the products and services the customer has bought;<br />

past volumes and prices; key contacts (and their ages, birthdays, hobbies, and favorite foods);<br />

competing suppliers; status of current contracts; estimated customer spending for the next<br />

few years; and assessments of competitive strengths and weaknesses in selling and servicing<br />

the account.

484 Part 3 Designing a Customer-Driven <strong>Marketing</strong> Strategy and Integrated <strong>Marketing</strong> Mix<br />

Direct-mail marketing<br />

Direct marketing by sending<br />

an offer, announcement,<br />

reminder, or other item to a<br />

person at a particular<br />

address.<br />

Some of these databases are huge. For example, casino operator Harrah’s Entertainment<br />