Economic Valuation of Environmental Impacts in ... - ARCHIVE: Defra

Economic Valuation of Environmental Impacts in ... - ARCHIVE: Defra

Economic Valuation of Environmental Impacts in ... - ARCHIVE: Defra

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong><br />

<strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged<br />

Areas<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al Report<br />

Submitted to<br />

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs<br />

3 rd January 2006<br />

<strong>Economic</strong>s For The Environment Consultancy Ltd (eftec) 16 Percy Street London W1T<br />

1DT, tel: 02075805383, fax: 02075805385, eftec@eftec.co.uk, www.eftec.co.uk

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

This report has been prepared by<br />

Ms Helen Johns, eftec<br />

Ms Ece Ozdemiroglu, eftec<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Nick Hanley, Stirl<strong>in</strong>g University<br />

Dr Sergio Colombo, University <strong>of</strong> Stirl<strong>in</strong>g / IFAPA Junta de Andalusia<br />

Dr Alistair Hamilton, Stirl<strong>in</strong>g University<br />

Dr Tony Hyde, Socio-<strong>Economic</strong> Research Services<br />

The fieldwork for this report was undertaken by Carrick James Market Research and Socio-<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> Research Services.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary work on the forecast changes to upland attributes by eftec was reviewed and<br />

expanded by Cumulus Consultants Ltd. <strong>in</strong> association with the Institute for European<br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> Policy and the Countryside and Community Research Unit. This work is<br />

quoted extensively <strong>in</strong> Section 2.<br />

The study team would like to thank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ian Bateman (University <strong>of</strong> East Anglia) who,<br />

as the peer reviewer, provided valuable comments at various stages <strong>of</strong> the work, and Dr<br />

Stavros Georgiou (CSERGE, University <strong>of</strong> East Anglia), who moderated the focus groups. The<br />

study team would also like to thank the Steer<strong>in</strong>g Group for their valuable comments<br />

throughout the study.<br />

eftec January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

Executive Summary<br />

E.1 Introduction<br />

This report summarises the methodology and f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> a study to estimate the economic<br />

value <strong>of</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> environmental features associated with the Severely Disadvantaged<br />

Areas <strong>in</strong> England, which could arise from changes to the Government support for agriculture<br />

<strong>in</strong> Less Favoured Area.<br />

Severely Disadvantaged Areas (SDAs) and Disadvantaged Areas (DAs) together comprise the<br />

English Less Favoured Areas (LFA). These are areas where farm<strong>in</strong>g is more difficult because<br />

<strong>of</strong> poor climate, soils and terra<strong>in</strong>. These lead to lower yields and higher production and<br />

transportation costs. LFAs are located ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> upland hill-farm<strong>in</strong>g areas. They <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

almost all <strong>of</strong> the upland areas <strong>in</strong> the North <strong>of</strong> England (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Penn<strong>in</strong>es, Lake District<br />

and North York Moors), the Peak District, some (from an English perspective) <strong>of</strong> the English-<br />

Welsh border, Exmoor, Dartmoor, and parts <strong>of</strong> Cornwall. Farm<strong>in</strong>g plays a crucial role <strong>in</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the dist<strong>in</strong>ctive landscape <strong>of</strong> such areas.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>strument for support <strong>of</strong> upland farm<strong>in</strong>g, the Hill Farm Allowance (HFA), is currently<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g revised as part <strong>of</strong> the new Rural Development Regulation which covers the period<br />

2007-2013. The ultimate policy objective <strong>of</strong> this revision is to generate the maximum public<br />

benefit provided by upland farmers.<br />

The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal stages <strong>of</strong> this study can be summarised as follows:<br />

• Identify a number <strong>of</strong> different policy scenarios which could arise <strong>in</strong> relation to the<br />

revision <strong>of</strong> the HFA (<strong>in</strong>itially identified by the eftec team and later expanded upon by<br />

Cumulus et al. (2005), which was subsequently used <strong>in</strong> the economic analysis);<br />

• Predict the likely effects – predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> quantity rather than<br />

quality - on fourteen different upland environmental attributes <strong>of</strong> these different policy<br />

scenarios;<br />

• Estimate the economic value <strong>of</strong> the changes <strong>in</strong> some <strong>of</strong> these attributes through a stated<br />

preference survey (the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal method be<strong>in</strong>g choice experiment);<br />

• Estimate the economic value <strong>of</strong> the changes <strong>in</strong> the rest <strong>of</strong> the attributes through benefit<br />

transfer; and;<br />

• Aggregate the economic values per attribute to estimate the total welfare change for<br />

different LFA policy revision scenarios.<br />

The economic valuation aspect <strong>of</strong> this study has been accomplished by means <strong>of</strong> a stated<br />

preference survey <strong>of</strong> the six Government Office Regions conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g SDAs (North West, North<br />

East, Yorkshire and Humber, West Midlands, East Midlands and South West), as well as one<br />

survey <strong>in</strong> a region not conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g SDAs (the South East). The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal valuation method<br />

used was the choice experiment approach, but the survey also conta<strong>in</strong>ed an element <strong>of</strong><br />

cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation.<br />

E.2 Upland attributes and policy scenarios<br />

The long list <strong>of</strong> upland attributes considered for <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> the survey was: heather<br />

moorland and bog, improved grassland, rough grassland, hay meadows, bracken, gorse,<br />

arable & set aside land, broadleaf and mixed woodland, coniferous woodland, field<br />

boundaries (hedgerows and drystone walls), cultural heritage, water quantity, water<br />

quality, and greenhouse gas emissions. Of these, heather moorland and bog, rough<br />

grassland, broadleaf and mixed woodland, field boundaries and cultural heritage were<br />

chosen as the five attributes to be used <strong>in</strong> the choice experiment. Cultural heritage may be<br />

taken to <strong>in</strong>clude the visual presence <strong>in</strong> the landscape <strong>of</strong> traditional farm build<strong>in</strong>gs; less<br />

visual aspects may be the presence <strong>of</strong> animals on the hill, traditional breeds, or traditional<br />

farm<strong>in</strong>g practices such as shepherd<strong>in</strong>g with sheep dogs. Given the shortlist <strong>of</strong> attributes<br />

eftec i January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

chosen, only changes to quantity, rather than quality, <strong>of</strong> the attributes (except for cultural<br />

heritage) were considered.<br />

Four different possible policy scenarios were identified and described. These are<br />

summarised as follows:<br />

Scenario 0 – Basel<strong>in</strong>e: there is no change <strong>in</strong> the strategic aims, structure and level <strong>of</strong><br />

upland support. Support rema<strong>in</strong>s focused on ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g upland farm<strong>in</strong>g systems with<br />

environmental enhancement be<strong>in</strong>g a secondary objective. In other words the Hill Farm<br />

Allowance scheme rema<strong>in</strong>s the same as it is presently.<br />

Scenario 1 - Environment-agri: the strategic policy aims to reflect the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

environmental and conservation objectives over production and the ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>of</strong> upland<br />

farm<strong>in</strong>g regimes. The same amount <strong>of</strong> LFA-type support still exists, but is targeted more<br />

towards achiev<strong>in</strong>g environmental goals.<br />

Scenario 2 - Environment only: the strategic aims for upland support are focused solely on<br />

achiev<strong>in</strong>g environmental goals. It is assumed that exist<strong>in</strong>g support is ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed, but it is<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to the agri-environment scheme budget and r<strong>in</strong>g-fenced for the uplands.<br />

The LFA scheme disappears.<br />

Scenario 3 – Abandonment-<strong>in</strong>tensification: under this scenario, upland support is<br />

withdrawn entirely. Exist<strong>in</strong>g fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> £27 million per year disappears and is ‘lost’ from<br />

the uplands. On many farms dom<strong>in</strong>ated by poorer, higher ground, farm<strong>in</strong>g would be<br />

completely abandoned.<br />

CAP reform and <strong>Environmental</strong> Stewardship are assumed to have been implemented <strong>in</strong> all<br />

scenarios.<br />

The possible effect <strong>of</strong> each scenario on the fourteen attributes <strong>in</strong> the long list was<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by Cumulus et al. (2005). However it should be emphasised that these need to<br />

be considered not as def<strong>in</strong>itive predictions, but as examples <strong>of</strong> possible outcomes. Further<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on attributes and scenarios can be found <strong>in</strong> Section 2 <strong>of</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> report.<br />

E.3. <strong>Valuation</strong> Methodology<br />

Two stated preference techniques are used <strong>in</strong> the report: choice experiment and<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation. The potential for benefits transfer is explored for upland attributes<br />

that could not (or need not) be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the stated preference survey.<br />

A choice experiment approach is used for the ma<strong>in</strong> part <strong>of</strong> the survey to elicit will<strong>in</strong>gness to<br />

pay (WTP) estimates for the five attributes <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the survey, namely: heather<br />

moorland and bog, rough grassland, broadleaf and mixed woodland, field boundaries and<br />

cultural heritage. The survey questionnaire consisted <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g sections: (A)<br />

attitudes, op<strong>in</strong>ions and uses; (B) choice experiment valuation section for SDAs <strong>in</strong> the<br />

respondent’s own GOR; (C) cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation question about SDAs <strong>in</strong> the rest <strong>of</strong> England;<br />

and (D) follow-up and socio-economic questions.<br />

In the choice experiment section, respondents were asked to choose their most preferred<br />

option <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the six choice sets they were given. Each choice set conta<strong>in</strong>ed three<br />

options: the current policy (basel<strong>in</strong>e) and alternatives A or B, which on the whole reflected<br />

the possible outcomes <strong>of</strong> Scenarios 1-3 with randomly allocated price tags (<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong><br />

annual tax payments <strong>of</strong> the household). In the six GORs with SDAs, respondents were<br />

presented <strong>in</strong>formation about and asked to make their choices for the SDAs <strong>in</strong> their own<br />

region. Respondents <strong>in</strong> the South East were asked the same question, but for attributes <strong>in</strong><br />

all SDAs <strong>in</strong> England.<br />

eftec ii January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

A cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation question was also added (<strong>in</strong> all questionnaires except the South<br />

East) to gauge respondents’ WTP for a s<strong>in</strong>gle improvement scenario for SDAs <strong>in</strong> all other<br />

regions except their own.<br />

The survey design underwent focus group and pilot survey stages before the ma<strong>in</strong> survey<br />

was undertaken. <strong>Valuation</strong> workshops were also undertaken after the survey as part <strong>of</strong><br />

validity test<strong>in</strong>g and to exam<strong>in</strong>e issues such as respondents’ understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the choice<br />

experiment tasks, the scope <strong>of</strong> the geographical area and environmental change, and<br />

generally the motivations beh<strong>in</strong>d their choices.<br />

Further details <strong>of</strong> the valuation methodology and <strong>in</strong>itial test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire can be<br />

found <strong>in</strong> Section 3. This study is the first <strong>of</strong> its k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the UK <strong>in</strong> that it exam<strong>in</strong>es (a<br />

selection <strong>of</strong>) the <strong>in</strong>dividual upland attributes separately identified but jo<strong>in</strong>tly provided,<br />

rather than as a bundle under the general head<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> ‘landscape’. Other studies that look<br />

at <strong>in</strong>dividual attributes on their own or together as landscape are also reviewed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

report (see Section 4).<br />

The other n<strong>in</strong>e attributes <strong>in</strong> the long list which had not been <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the choice<br />

experiment were considered for their suitability for benefit transfer. Of the n<strong>in</strong>e, only hay<br />

meadows were found to be a suitable candidate for transfer <strong>of</strong> amenity benefits, from their<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Environmental</strong> Landscape Features (ELF) model (IERM/SAC, 2001).<br />

Greenhouse gas emissions could be used for benefit transfer if forecasts for how they may<br />

change under the different policy scenarios were quantitative. Other features either had<br />

not been previously valued (e.g. bracken, gorse), or had been valued, but were too<br />

complex as goods to be transferable (e.g. water quality). Section 5 conta<strong>in</strong>s a detailed<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> the suitability <strong>of</strong> the evidence from current literature for benefits transfer.<br />

E.4. Results <strong>of</strong> the Stated Preference Survey<br />

Questions on attitudes and habits showed that respondents <strong>in</strong> general considered<br />

environmental policy to be important compared to other policy areas, but did not consider<br />

protect<strong>in</strong>g the countryside to be the most press<strong>in</strong>g environmental issue. A quarter <strong>of</strong><br />

respondents were members <strong>of</strong> an environmental, recreational, heritage or farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

organisation. A substantial majority <strong>of</strong> respondents were familiar with the SDAs <strong>in</strong> their<br />

area and visited them for recreational purposes.<br />

Overall, 84% percent <strong>of</strong> respondents said that they visited the countryside, and 79% SDAs,<br />

for recreational purposes (these are the sums <strong>of</strong> those visit<strong>in</strong>g for recreational purposes<br />

only and those who visit for both work and recreation). There was therefore a high level <strong>of</strong><br />

awareness and experience <strong>of</strong> SDAs amongst respondents.<br />

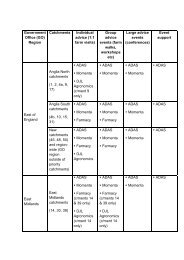

Table E.1 shows the WTP estimates from the choice experiment survey for each GOR region<br />

(except for the North East, for which WTP figures were not derived).<br />

WTP results for which the confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals <strong>in</strong>clude zero are not significantly different<br />

from zero at the 5% level. The South East and North West show the highest number <strong>of</strong><br />

significant results. For further detail on the analysis <strong>of</strong> average WTP responses us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

different econometric models, see Section 7 and Annex 5.<br />

The analysis <strong>of</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation question <strong>in</strong> the surveys for the six regions with<br />

SDAs revealed an average WTP across all six regions <strong>of</strong> £49–105 per household per year for a<br />

change from a ‘worst case’ to a ‘best case’ scenario.<br />

eftec iii January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

Table E.1: WTP results (£ per household per year per 1% improvement for the first four<br />

attributes) derived from the choice experiment for each region (except the North East).<br />

NW YH WM EM SW SE<br />

Model used 1 : A&S A&S AO A&S AO A&S<br />

HMB 0.78 0.30 0.80 1.04 0.92 0.81<br />

(0.45-1.11) (-0.06-0.65) (0.42-1.18) (-0.03-2.31) (0.37-1.54) (0.36-1.25)<br />

RG 0.74 0.31 0.25 0.08 -0.06 0.50<br />

(0.45-1.05) (0.01-0.60) (-0.05-0.53) (-0.99-0.91) (-0.56-0.39) (0.14-0.86)<br />

BMW 0.61 0.15 0.43 0.97 0.39 1.21<br />

(0.30-0.91) (-0.16-0.48) (0.07-0.81) (0.03-2.46) (-0.01-0.78) (0.81-1.66)<br />

FB 0.00 0.04 0.02 0.06 -0.04 0.06<br />

(-0.03-0.04) (0.01-0.08) (-0.02-0.05) (-0.06-0.18) (-0.11-0.02) (0.02-0.11)<br />

CH<br />

(small 2 )<br />

1.03<br />

(-1.84-4.14)<br />

3.08<br />

(-0.24-6.71)<br />

-0.40<br />

(-4.27-3.03)<br />

7.92<br />

(-1.96-22.62)<br />

5.48<br />

(-0.11-11.59)<br />

0.81<br />

(-3.22-4.96)<br />

CH<br />

(big 3 )<br />

4.89<br />

(1.52-8.43)<br />

11.93<br />

(8.47-15.44)<br />

6.56<br />

(2.49-10.73)<br />

22.51<br />

(11.84-37.24)<br />

7.68<br />

(1.24-15.03)<br />

15.79<br />

(11.47-20.64)<br />

Figures <strong>in</strong> brackets are the 95% confidence <strong>in</strong>terval. Note that if the confidence <strong>in</strong>terval spans zero<br />

then the WTP is not significantly different from zero.<br />

HMB = heather moorland and bog, RG = rough grassland, BMW = mixed and broadleaf woodland, FB =<br />

field boundaries, CH = cultural heritage.<br />

1<br />

A&S = attributes and socio-economic variables; AO = attributes only<br />

2<br />

from “rapid decl<strong>in</strong>e” to “no change”<br />

3<br />

from “rapid decl<strong>in</strong>e” to “much better conservation”<br />

E.5. Validity Test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

With regards to stated preference studies, there are three types <strong>of</strong> validity which should be<br />

considered: content, construct and convergent validity. Content validity assesses whether a<br />

study asked the right questions <strong>in</strong> a clear, understandable, sensible and appropriate manner<br />

with which to obta<strong>in</strong> a valid estimate <strong>of</strong> the WTP measure under <strong>in</strong>vestigation. Construct<br />

validity exam<strong>in</strong>es whether the relationships between choices or WTP estimates and factors<br />

likely to affect those are <strong>in</strong> accordance with expectations based on economic theory.<br />

Convergent validity exam<strong>in</strong>es whether the quantitative results are broadly comparable with<br />

the results <strong>of</strong> other studies valu<strong>in</strong>g similar goods.<br />

The validity tests <strong>in</strong>volve the analysis <strong>of</strong> responses about attitudes towards the survey,<br />

econometric analysis <strong>of</strong> the WTP function and comparison <strong>of</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs aga<strong>in</strong>st prior<br />

expectations and comparison <strong>of</strong> the results from this study to previous studies from the<br />

literature. Section 7 <strong>of</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> report presents all three types <strong>of</strong> validity test<strong>in</strong>g. Here it<br />

suffices to summarise the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> these assessments.<br />

Content validity<br />

• Income non-response: the <strong>in</strong>come non-response rate was relatively high, particularly <strong>in</strong><br />

Yorkshire and Humber and the East Midlands. This precluded the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>come as an<br />

explanatory factor <strong>in</strong> the regression models <strong>of</strong> four regions.<br />

• Protest bids: the number <strong>of</strong> protest bids was also relatively high, and <strong>in</strong> the case <strong>of</strong> the<br />

North East, may have been the ma<strong>in</strong> reason for the model to return <strong>in</strong>significant<br />

coefficients for all upland attributes. Protest bids were at similar levels for both<br />

sections <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire while genu<strong>in</strong>e zero WTPs were noticeably higher for<br />

Section C (CV) than Section B (CE). This should be expected, as respondents are more<br />

likely to value SDAs <strong>in</strong> their own region than elsewhere <strong>in</strong> the country.<br />

• Attitudes: 69% <strong>of</strong> the survey respondents found the survey easy to understand while only<br />

20% found it difficult to understand.<br />

Construct validity<br />

• The most important f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the construct validity analysis is that for both regression<br />

models (an attributes only model and an attribute plus socio-economic variables model)<br />

for each region, the coefficient on tax is both negative and significant at the 5% level.<br />

eftec iv January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

This <strong>in</strong>dicates that respondents were not mak<strong>in</strong>g random or arbitrary choices, but<br />

considered the cost <strong>of</strong> options before mak<strong>in</strong>g their choices.<br />

• Income was not found to be a significant determ<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>of</strong> WTP <strong>in</strong> the choice experiment<br />

for the three regions where it could be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the regression models. This could be<br />

largely due to the high non-response rate, particularly as <strong>in</strong>come was shown to be a<br />

significant determ<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>of</strong> WTP <strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation question, where all regions<br />

were pooled together for the analysis.<br />

• In all regions except the North East, at least two upland attributes positively affect<br />

respondents’ choices.<br />

• In general, other characteristics affect respondents’ choices as one would expect:<br />

people who consider environmental policy to be important, people who are members <strong>of</strong><br />

environmental or recreational clubs, more educated people, and people who visit SDAs<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten (except <strong>in</strong> the North West, where many people visit them for work) are all<br />

more likely to be will<strong>in</strong>g to pay for upland landscape improvements.<br />

• Age, gender and rural/urban location, however, do not appear to consistently affect<br />

choices.<br />

Convergent validity<br />

• Comparison with the mean WTP estimate range supplied by the ELF model (suitably<br />

adjusted for appropriate comparison) shows that this study’s regional WTP estimates are<br />

broadly similar for rough grassland, broadleaf and mixed woodland and field boundaries,<br />

but dissimilar (generally higher) for heather moorland and bog.<br />

• Other studies valu<strong>in</strong>g landscapes which cover roughly comparable areas to those valued<br />

by respondents <strong>in</strong> this study show similar (or <strong>in</strong> one case higher) WTP for improvements<br />

<strong>in</strong> landscape attributes.<br />

E.6: Aggregation<br />

The study results <strong>in</strong>dicate a fair degree <strong>of</strong> heterogeneity between regions. The differences<br />

appear to be greater than could be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by socio-economic factors alone. Therefore<br />

we would suggest that there is some regional difference which cannot presently be<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>ed, which <strong>in</strong> particular may give rise to a significant degree <strong>of</strong> transfer error <strong>in</strong> a<br />

potential benefits transfer exercise. For this reason, we do not th<strong>in</strong>k it advisable to conduct<br />

a benefits transfer exercise from the South East results to the other two non-SDA regions <strong>of</strong><br />

England.<br />

For the purposes <strong>of</strong> aggregation, the valuation results should be aggregated across<br />

attributes, across the relevant population, and across time.<br />

Aggregat<strong>in</strong>g across attributes yields estimates for the compensat<strong>in</strong>g surplus (CS) for each<br />

region. This is the change <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come from an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s orig<strong>in</strong>al level that keeps the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual at the orig<strong>in</strong>al utility level given a new quantity level for a good. The CS<br />

estimates <strong>in</strong> this study therefore represent a measure <strong>of</strong> welfare <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong><br />

respondents’ average WTP to move from the state <strong>of</strong> the world given <strong>in</strong> Scenario 0 to the<br />

state <strong>of</strong> the world given <strong>in</strong> Scenarios 1 to 3.<br />

These CS estimates are then aggregated across the relevant regional populations (Table<br />

8.4) and across time (Table 8.8, E.2) through discount<strong>in</strong>g. Values found for the only<br />

transferable attribute (hay meadows) are also added. Table E.2 shows the f<strong>in</strong>al benefit<br />

estimate aggregated across attributes, population and time.<br />

eftec v January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

Table E.2: Aggregation <strong>of</strong> benefits across attributes, population and time<br />

Scenario 1<br />

Scenario 2<br />

Scenario 3<br />

Env-agri<br />

Env only<br />

Aband-<strong>in</strong>tern<br />

Estimated annual net benefit <strong>of</strong> eventual change (£ per year)<br />

Choice experiment<br />

attributes –<br />

256,830,000<br />

301,860,000<br />

-14,690,000<br />

compensat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(132,480,000 – (169,600,000 – (-50,740,000 –<br />

surplus (Table 8.4)<br />

Hay meadows<br />

421,700,000) 486,490,000)<br />

22,500,000)<br />

(Table 8.7) 62,000 156,000 -94,000<br />

Estimated discounted benefit over the period 2007-2013 (£ million)<br />

Choice experiment<br />

897<br />

1,054<br />

-51<br />

attributes<br />

(463 – 1,473) (592 – 1,699)<br />

(-177 – +79)<br />

Hay meadows 0.2 0.5 -0.3<br />

TOTAL 897<br />

1,055<br />

-51<br />

(463 – 1,473) (593 – 1,700)<br />

(-177 – +79)<br />

Figures <strong>in</strong> brackets <strong>in</strong>dicate 95% confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals.<br />

E.7 Conclusions<br />

This study is one <strong>of</strong> two <strong>in</strong>terl<strong>in</strong>ked studies seek<strong>in</strong>g to generate monetary valuation<br />

evidence to <strong>in</strong>form changes to Government support for agriculture <strong>in</strong> the LFAs (the other<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g Cumulus et al., 2005). The revision <strong>of</strong> this policy will affect land use management <strong>in</strong><br />

the SDAs, and as a result the current quality and quantity <strong>of</strong> various upland attributes or<br />

features. Cumulus et al. (2005) establish the basel<strong>in</strong>e changes <strong>in</strong> these attributes due to<br />

CAP and other currently planned reforms, and analyse the potential changes <strong>in</strong> the upland<br />

attributes under three policy revision options. The policy options presented <strong>in</strong> that report<br />

and used <strong>in</strong> this study are not def<strong>in</strong>itive predictions but possible outcomes. The conclusions<br />

<strong>of</strong> this study should be <strong>in</strong>terpreted with that caveat <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

The objective <strong>of</strong> this study was specifically to provide monetary estimates <strong>of</strong> the relative<br />

economic value <strong>of</strong> upland attributes <strong>in</strong> each GOR with SDAs so that the allocation <strong>of</strong> funds<br />

can benefit from this <strong>in</strong>formation (e.g. more fund<strong>in</strong>g for the protection or improvement <strong>of</strong><br />

upland attributes valued more highly by the GOR population). Some <strong>of</strong> this <strong>in</strong>formation is<br />

collected through a choice experiment survey applied separately <strong>in</strong> each GOR with SDAs (as<br />

well as <strong>in</strong> the South East GOR) while some is estimated through benefits transfer. It was not<br />

possible to provide any quantitative monetised estimates for the changes <strong>in</strong> a number <strong>of</strong><br />

attributes due to lack <strong>of</strong> data.<br />

Individual preferences for upland attributes are only one part <strong>of</strong> the evidence needed to<br />

<strong>in</strong>form the policy revision. The conclusions presented here are based only on the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong><br />

this study and may not necessarily be the conclusions reached at the end <strong>of</strong> the policy<br />

appraisal process which should consider other evidence (e.g. expert op<strong>in</strong>ion).<br />

On the basis <strong>of</strong> the stated preference survey, we can make the follow<strong>in</strong>g general<br />

conclusions:<br />

• On the whole, people are will<strong>in</strong>g to pay to contribute to the improvements <strong>in</strong> Severely<br />

Disadvantaged Areas and upland attributes associated with them. The exception to this<br />

are the results for the North West GOR which displayed a significant negative constant<br />

term <strong>in</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the regression models (that which considered the upland attributes<br />

alone), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that respondents <strong>in</strong> the North West may actually prefer the current<br />

policy option to scenarios <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g alleged improvements. This fits <strong>in</strong> with attitud<strong>in</strong>al<br />

responses from the North West, and the fact that the policy cost (<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> annual<br />

tax payments) attribute showed the most negative coefficient <strong>in</strong> the North West,<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g an unwill<strong>in</strong>gness to pay. The North West results, along with the high<br />

will<strong>in</strong>gness to pay <strong>of</strong> South Eastern respondents, to some extent <strong>in</strong>dicates that people<br />

either value what they do not already have <strong>in</strong> abundance, or that people <strong>in</strong> the North<br />

eftec vi January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

West are less will<strong>in</strong>g to pay alone for what they consider to be a national asset (the<br />

Lake District).<br />

• There are large variations <strong>in</strong> the values <strong>in</strong>dividuals place on landscape features across<br />

different regions that are not possible to expla<strong>in</strong> fully on the basis <strong>of</strong> socio-economic<br />

differences between populations.<br />

• Notwithstand<strong>in</strong>g the regional differences, on the whole, changes <strong>in</strong> the cultural<br />

heritage (if a large improvement) and policy cost attributes seem to have played a role<br />

<strong>in</strong> the choices respondents made. The consistently large coefficients for a large<br />

improvement <strong>in</strong> cultural heritage could be purely because a large discrete change (from<br />

“rapid decl<strong>in</strong>e” to “much better conservation”) was on <strong>of</strong>fer. If we had been able to<br />

measure the cultural heritage attribute quantitatively, and hence vary it cont<strong>in</strong>uously,<br />

it may not have been as consistently important <strong>in</strong> affect<strong>in</strong>g respondents’ choices. That<br />

said, it was clear from the focus groups, valuation workshops and reasons respondents<br />

gave for be<strong>in</strong>g will<strong>in</strong>g to pay for landscape improvements that cultural heritage is<br />

someth<strong>in</strong>g that is highly valued. Therefore, the implications <strong>of</strong> any agricultural or<br />

environmental improvement scheme on this attribute should be considered carefully.<br />

• In terms <strong>of</strong> the other attributes, woodland was the next most likely to affect<br />

respondents’ choices, followed by heather moorland and bog, rough grassland and field<br />

boundaries; the latter did not appear to be highly valued. It is possible that<br />

respondents saw field boundaries as an attribute which could be rebuilt or replanted,<br />

and which was not gone forever if lost.<br />

• There is evidence <strong>of</strong> preference heterogeneity with<strong>in</strong> each region.<br />

• There is evidence (from the cont<strong>in</strong>gent valuation question <strong>in</strong> the survey) that<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> one GOR with SDAs are likely to value the SDAs <strong>in</strong> the rest <strong>of</strong> England,<br />

albeit to a lesser extent than they do the SDAs <strong>in</strong> their own region. However, this<br />

result is derived from a context where respondents were asked to choose between the<br />

upper and lower ranges which attributes took under the choice experiment;<br />

respondents would presumably have been will<strong>in</strong>g to pay much less if they had been<br />

asked to pay for a much smaller improvement.<br />

• On the basis <strong>of</strong> the South East survey, there is also evidence that those who live <strong>in</strong><br />

regions without SDAs are likely to have positive preferences for the improvement <strong>of</strong><br />

upland attributes <strong>in</strong> the SDAs. However, due to significant but not completely<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>able differences <strong>in</strong> preferences across GORs, we cannot transfer the results <strong>of</strong><br />

the South East to London and East <strong>of</strong> England GORs which also do not have SDAs.<br />

• A f<strong>in</strong>al piece <strong>of</strong> evidence for non-use values comes from the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that many<br />

respondents <strong>in</strong> SDA GORs who said that they never visited SDAs were nevertheless<br />

will<strong>in</strong>g to pay for improvements.<br />

On the basis <strong>of</strong> the choice experiment and benefits transfer results, the “environment only”<br />

scenario (Scenario 2) appears to yield the greatest benefits. This is because it provides<br />

superior quantities <strong>of</strong> all attributes except rough grassland, which was not valued<br />

particularly highly by respondents. On the basis <strong>of</strong> the quantitative assessment by Cumulus<br />

et al. (2005), Scenario 3 (“Abandonment-<strong>in</strong>tensification”) was likely to generate<br />

disbenefits. The economic assessment <strong>in</strong> this study also comes up with a negative benefit<br />

estimate for this scenario, i.e. a disbenefit. However, it should be noted that this estimate<br />

is not significantly different from zero for any <strong>of</strong> the regions. Scenario 1 (“Environmentagri”)<br />

gives a benefit which is about 85% <strong>of</strong> that <strong>in</strong> Scenario 2.<br />

Other policy scenarios can be analysed us<strong>in</strong>g the results <strong>of</strong> the choice experiment as long as<br />

the magnitude <strong>of</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> the attributes forecast for the scenarios is with<strong>in</strong> the set up<br />

changes covered by the choice experiment. The economic value <strong>of</strong> any changes smaller or<br />

larger than the set covered <strong>in</strong> the experiment cannot be estimated us<strong>in</strong>g the results <strong>of</strong> this<br />

study.<br />

eftec vii January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

This page is left <strong>in</strong>tentionally blank<br />

eftec viii January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 1<br />

1.1<br />

1.2<br />

POLICY BACKGROUND ............................................................................... 1<br />

STUDY OUTLINE ..................................................................................... 1<br />

2. THE UPLAND ATTRIBUTES AND THEIR FORECAST CHANGES ...........................5<br />

2.1<br />

2.2<br />

2.3<br />

UPLAND ATTRIBUTES ................................................................................ 5<br />

POLICY SCENARIOS .................................................................................. 9<br />

ATTRIBUTE LEVEL CHANGES RESULTING FROM POLICY SCENARIOS ..................................11<br />

3. VALUATION METHODOLOGY ................................................................ 17<br />

3.1<br />

3.2<br />

3.3<br />

INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................17<br />

CONCEPTUAL BASIS.................................................................................18<br />

IMPLEMENTING THE STATED PREFERENCE SURVEY ...................................................20<br />

4. VALUATION OF LANDSCAPE – LITERATURE REVIEW.................................... 26<br />

4.1<br />

4.2<br />

4.3<br />

4.4<br />

OVERVIEW..........................................................................................26<br />

REVIEW STUDIES....................................................................................26<br />

INDIVIDUAL VALUATION STUDIES ....................................................................27<br />

ISSUES ARISING .....................................................................................28<br />

5. VALUATION OF ATTRIBUTES NOT INCLUDED IN THE CHOICE EXPERIMENT........ 30<br />

5.1<br />

5.2<br />

BENEFITS TRANSFER USING THE ENVIRONMENTAL LANDSCAPE FEATURES MODEL .....................30<br />

OTHER ATTRIBUTES ................................................................................31<br />

6. STATED PREFERENCE SURVEY: SUMMARY AND NON-MONETARY RESULTS ........ 33<br />

6.1<br />

6.2<br />

6.3<br />

MAIN QUESTIONNAIRE SUMMARY ....................................................................33<br />

SOCIO-ECONOMIC REPRESENTATIVENESS OF THE SAMPLE ............................................34<br />

ATTITUDES, OPINIONS AND OTHER INFORMATION ...................................................37<br />

7. VALIDITY TESTING ............................................................................ 40<br />

7.1<br />

7.2<br />

7.3<br />

7.4<br />

7.5<br />

CONTENT VALIDITY.................................................................................40<br />

CONSTRUCT VALIDITY: WTP FUNCTIONS ...........................................................45<br />

CONVERGENT VALIDITY: COMPARISON WITH PREVIOUS STUDIES .....................................52<br />

VALUATION WORKSHOP FINDINGS ..................................................................54<br />

VALIDITY TESTING - SUMMARY......................................................................54<br />

8. WILLINGNESS TO PAY RESULTS, AGGREGATION, POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND<br />

CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................... 56<br />

8.1<br />

8.2<br />

8.3<br />

WTP RESULTS .....................................................................................56<br />

AGGREGATION......................................................................................58<br />

CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................62<br />

REFERENCES ............................................................................................. 64<br />

Annexes<br />

(<strong>in</strong> separate documents)<br />

ANNEX 1 – FINAL FOCUS GROUP PROTOCOL<br />

ANNEX 2 – FOCUS GROUP REPORT<br />

ANNEX 3 - PILOT SURVEY REPORT<br />

ANNEX 4 - FINAL QUESTIONNAIRE<br />

ANNEX 5 – TECHNICAL ANNEX<br />

ANNEX 6 – VALUATION WORKSHOP PROTOCOL<br />

ANNEX 7 - VALUATION WORKSHOP – RESULTS AND DISCUSSION<br />

ANNEX 8 - PEER REVIEWER REPORT<br />

eftec ix January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

This page is left <strong>in</strong>tentionally blank<br />

eftec x January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

1. Introduction<br />

1.1 Policy Background<br />

This report covers the research, design and data analysis stages <strong>of</strong> a study to estimate the<br />

economic values <strong>of</strong> environmental features associated with the Severely Disadvantaged<br />

Areas <strong>in</strong> England, and the likely changes <strong>in</strong> these features that could result from the<br />

redesign <strong>of</strong> the Less Favoured Area policy.<br />

Severely Disadvantaged Areas (SDAs) and Disadvantaged Areas (DAs) together comprise the<br />

English “Less Favoured Areas”, a land classification <strong>in</strong>stigated at the EU level <strong>in</strong> 1975. All<br />

uplands are covered by the LFA. Farmers <strong>in</strong> Less Favoured Areas receive compensatory<br />

allowances for the fact that the nature <strong>of</strong> the surround<strong>in</strong>g physical landscape results <strong>in</strong><br />

higher production and transportation costs, as well as to acknowledge the role farmers play<br />

<strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the landscape and rural communities. SDAs are <strong>of</strong>ten remote upland hillfarm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

areas which face particular difficulty <strong>in</strong> this respect. They <strong>in</strong>clude almost all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

upland areas <strong>in</strong> the North <strong>of</strong> England (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Penn<strong>in</strong>es, Lake District and North York<br />

Moors), the Peak District, some <strong>of</strong> the English-Welsh border, and Exmoor and Dartmoor.<br />

The policy on support for upland farmers, i.e. the Hill Farm allowance (HFA), is currently<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g revised as part <strong>of</strong> the new Rural Development Regulation which covers the period<br />

2007-2013. However, what the new policy will be, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g for the Severely Disadvantaged<br />

Areas, is currently not known. Consequently, despite some prelim<strong>in</strong>ary work <strong>in</strong> this area,<br />

the implications for agricultural practice and hence the landscape and environment are also<br />

not known with any great certa<strong>in</strong>ty. Notwithstand<strong>in</strong>g the current uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, the ultimate<br />

policy objective <strong>of</strong> the LFA revision is to reward susta<strong>in</strong>able land management and the<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> public benefits.<br />

1.2 Study Outl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

1.2.1 Study objectives<br />

The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal objective <strong>of</strong> this study is to estimate the changes <strong>in</strong> external environmental<br />

values <strong>in</strong> the SDA associated with the land use changes that are expected to follow from<br />

potential revisions <strong>of</strong> the LFA. Other studies exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the possible economic effects <strong>of</strong><br />

policy design will consider the estimation <strong>of</strong> the social benefits <strong>of</strong> hill farm<strong>in</strong>g and analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>ancial position <strong>of</strong> farmers <strong>in</strong> the SDAs.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> different environmental and landscape features associated with SDAs are<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the study (referred to as ‘upland attributes’ <strong>in</strong> this report). It is assumed that<br />

each <strong>of</strong> these attributes could potentially be changed – for better or worse – by any changes<br />

<strong>in</strong> support to upland farm<strong>in</strong>g. Given the current uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, as mentioned above, different<br />

scenarios <strong>of</strong> policy change are also exam<strong>in</strong>ed. Thus, the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal stages <strong>of</strong> the study can be<br />

summarised as follows:<br />

• Identify a number <strong>of</strong> different policy scenarios which could arise <strong>in</strong> relation to the<br />

revision <strong>of</strong> the LFA;<br />

• Predict the likely effects – predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> quantity rather than<br />

quality - on fourteen different upland environmental attributes <strong>of</strong> these different policy<br />

scenarios;<br />

• Estimate the economic value <strong>of</strong> the changes <strong>in</strong> some (see Section 1.2.2 below) <strong>of</strong> these<br />

attributes through a stated preference survey (the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal method be<strong>in</strong>g choice<br />

experiment);<br />

eftec 1 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

• Estimate the economic value <strong>of</strong> the changes <strong>in</strong> the rest <strong>of</strong> the attributes (where<br />

possible) through benefits transfer; and<br />

• Aggregate the economic values per attribute to estimate the total welfare change for<br />

different LFA policy revision scenarios.<br />

The overall objective <strong>of</strong> the study is to provide evidence for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g the allocation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g upland support with<strong>in</strong> each region, at the current level. It is not about<br />

undertak<strong>in</strong>g, say, a cost benefit analysis to decide whether LFA support should be abolished<br />

or the funds allocated to LFA should be decreased or <strong>in</strong>creased. In order to <strong>in</strong>form the<br />

allocation decisions (both between different environmental attributes and across the<br />

regions with SDAs), the relevant <strong>in</strong>formation is the relative economic value associated with<br />

each upland attribute. This regional focus has <strong>in</strong>fluenced the design <strong>of</strong> the stated<br />

preference study, and <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g the results for <strong>in</strong>dividual upland attributes (<strong>in</strong> Sections 6<br />

and 7) and the aggregated estimates (Section 8), this objective should be kept <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

1.2.2 Scope<br />

The scope <strong>of</strong> the project can be thought <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong>: environmental impacts,<br />

geographical coverage and regional level disaggregation.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> environmental impacts, the long list <strong>of</strong> fourteen upland attributes to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong><br />

the study was decided jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the project team and the Steer<strong>in</strong>g Group. These<br />

attributes, which are described <strong>in</strong> more detail <strong>in</strong> Section 2.1, are:<br />

• heather moorland and bog*;<br />

• improved grassland;<br />

• rough grassland*;<br />

• hay meadows;<br />

• bracken;<br />

• gorse;<br />

• arable & set aside land;<br />

• broadleaf and mixed woodland*;<br />

• coniferous woodland;<br />

• field boundaries*;<br />

• cultural heritage*;<br />

• water quantity;<br />

• water quality; and<br />

• greenhouse gas emissions.<br />

The attributes marked with an asterisk are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the stated preference questionnaire.<br />

This selection was suggested by the study team on the basis <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial research and<br />

focus group f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and approved by the Steer<strong>in</strong>g Group prior to the pilot survey.<br />

The overall geographical scope <strong>of</strong> the study is the SDAs <strong>in</strong> England, namely <strong>in</strong> six<br />

Government Office Regions (GORs) (see Fig 1.1): the North West, North East, Yorkshire and<br />

the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, and the South West. SDAs <strong>in</strong> other parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

UK and Disadvantaged Areas are explicitly excluded.<br />

The stated preference study was designed and implemented separately <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

above mentioned GORs <strong>in</strong> order to estimate the economic value <strong>of</strong> SDAs with<strong>in</strong> each region<br />

as expressed by the population <strong>of</strong> that region. In addition, we also <strong>in</strong>vestigated the<br />

economic value <strong>of</strong> the attributes <strong>of</strong> the SDAs as held by the population liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> GORs which<br />

do not conta<strong>in</strong> SDAs. In order to save time and budget, <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> undertak<strong>in</strong>g a stated<br />

preference survey <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the three GORs without SDAs, we implemented a survey <strong>in</strong> one<br />

<strong>of</strong> those, namely, the South East GOR. The aim was to transfer the results from the South<br />

East to the two other regions without SDAs (London and the East). The results <strong>of</strong> the<br />

surveys show that such a transfer is not advisable given the regional differences. This is<br />

eftec 2 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

further discussed <strong>in</strong> Section 8. Respondents <strong>in</strong> the six SDA-GORs were also asked a less<br />

detailed question about their value for SDAs <strong>in</strong> the regions <strong>of</strong> England other than their own.<br />

The feasibility <strong>of</strong> estimat<strong>in</strong>g (through benefits transfer) the economic values for the<br />

attributes excluded from the stated preference study us<strong>in</strong>g the evidence <strong>in</strong> the current<br />

literature is discussed <strong>in</strong> Section 5.<br />

Fig 1.1: Map <strong>of</strong> England show<strong>in</strong>g the Severely Disadvantaged Areas <strong>in</strong> p<strong>in</strong>k and GOR<br />

borders <strong>in</strong> green.<br />

1.2.3 Study and report structure<br />

A schematic show<strong>in</strong>g the study structure is given <strong>in</strong> Figure 1.2. The ‘policy – impact –<br />

economic values’ structure forms the basis <strong>of</strong> the study. The impact analysis was<br />

undertaken by Cumulus et al. (2005) and their f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on the upland attributes <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest<br />

eftec 3 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

<strong>in</strong> the survey and the possible land use changes brought about by different potential policy<br />

scenarios are summarised <strong>in</strong> Section 2. Section 3 describes the conceptual bases <strong>of</strong> the<br />

valuation methodologies used and the stages <strong>in</strong> their practical implementation. Section 4<br />

discusses the literature review conducted as <strong>in</strong>itial research for the stated preference<br />

survey and the benefits transfer exercise. Section 5 discusses the estimation <strong>of</strong> value<br />

changes <strong>of</strong> the upland attributes which were not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the choice experiment. Section<br />

6 discusses the ma<strong>in</strong> survey results, and Section 7 the validity test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> these results.<br />

Section 8 aggregates the survey results with these results to ga<strong>in</strong> estimates <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

value change, discusses the policy implications and outl<strong>in</strong>es the conclusions.<br />

CE<br />

SDA<br />

GORs<br />

(residents<br />

for own<br />

GOR)<br />

Policy<br />

scenarios<br />

Policy Impact <strong>Economic</strong><br />

Values<br />

1 non-SDA<br />

GOR<br />

(nonresidents<br />

for other<br />

GORs)<br />

CV<br />

SDA<br />

GORs<br />

(residents<br />

for other<br />

GORs)<br />

Impact<br />

analysis<br />

SP survey<br />

Aggregation<br />

Workshops<br />

Upland<br />

attributes<br />

Benefits<br />

transfer<br />

Figure 1.2: Flowchart show<strong>in</strong>g the structure <strong>of</strong> the study. Blue ellipses <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

processes, while green boxes <strong>in</strong>dicate components <strong>of</strong> economic valuation. Italics <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts. CE and CV are short for Choice Experiment and Cont<strong>in</strong>gent <strong>Valuation</strong> – the two<br />

valuation methods used (see Section 3 for details).<br />

eftec 4 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

2. The Upland Attributes and Their Forecast Changes<br />

This Section presents the upland attributes exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the study, <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> their<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ition and current trends (Section 2.1), and how they may be expected to change under<br />

four potential policy scenarios. The policies themselves are outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 2.2, and the<br />

expected changes <strong>in</strong> attribute levels <strong>in</strong> Section 2.3.<br />

Although eftec performed preparatory work on the current trends and forecasts <strong>in</strong> attribute<br />

levels at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this study, this work was reviewed and extended <strong>in</strong> a parallel<br />

study by Cumulus et al. (2005). Consequently, the Cumulus report is used as the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> this report. For full details on current trends and forecasts <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

attributes, the reader is referred to Cumulus et al. (2005).<br />

2.1 Upland Attributes<br />

2.1.1 Attribute long list<br />

The long list <strong>of</strong> upland attributes for use <strong>in</strong> the study was decided jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the project<br />

team and steer<strong>in</strong>g group. These attributes were chosen as they are most likely to be<br />

affected by changes <strong>in</strong> LFA policy.<br />

For those attributes that are essentially a habitat type, care has been taken to standardise<br />

the def<strong>in</strong>itions as much as possible to fit with other studies and allow use <strong>of</strong> other data. In<br />

particular, reference has been made to UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UKBAP) broad habitat<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itions 1 and the Countryside Survey (Ha<strong>in</strong>es-Young et al., 2000). Differences <strong>in</strong><br />

def<strong>in</strong>itions are discussed later. Note that <strong>in</strong> the uplands, particularly <strong>in</strong> unfenced areas<br />

used for extensive graz<strong>in</strong>g, many <strong>of</strong> these habitats can occur together <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tricate<br />

mosaic.<br />

A description <strong>of</strong> the long list <strong>of</strong> attributes follows (numbered A1-A14).<br />

A1. Heather moorland and bog: Calluna vulgaris (heather) dom<strong>in</strong>ates heather moorland,<br />

although the extent <strong>of</strong> that dom<strong>in</strong>ation varies from very high <strong>in</strong> dry heath (typically<br />

on well-dra<strong>in</strong>ed nutrient-poor acid soils) to lower <strong>in</strong> wet heath (found on wetter,<br />

peaty soils). In areas <strong>of</strong> high ra<strong>in</strong>fall and over flatter areas and <strong>in</strong> hollows, bog<br />

habitat may be found. This high conservation value habitat is <strong>of</strong>ten characterised by<br />

a high cover <strong>of</strong> Sphagnum mosses. These habitats are all typically used as extensive<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g, particularly for sheep. All <strong>of</strong> these habitats can be found over peat or peaty<br />

podsol soils, and peat erosion is <strong>of</strong>ten a problem when the habitat is over-grazed or<br />

subject to nutrient enrichment.<br />

A2. Improved grassland: This usually occurs on fertile soils, is dom<strong>in</strong>ated by fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

plant species preferred by livestock, and is used ma<strong>in</strong>ly for either pasture or silage.<br />

Improved grassland is typically found on the valley floors, or on the less steep slopes.<br />

These areas will be enclosed to keep <strong>in</strong> (or keep out) graz<strong>in</strong>g animals. Many<br />

improved grassland areas would have previously consisted <strong>of</strong> smaller fields, but <strong>in</strong><br />

places these have been amalgamated to make it easier to manage (apply<strong>in</strong>g fertiliser<br />

and herbicides, plough<strong>in</strong>g and re-seed<strong>in</strong>g) and to reduce boundary ma<strong>in</strong>tenance.<br />

A3. Rough grassland: This def<strong>in</strong>ition applies to areas typically used for extensive<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g, usually by sheep, and <strong>in</strong> this study is taken to <strong>in</strong>clude acid grasslands<br />

(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g grass dom<strong>in</strong>ated moorland) and calcareous grasslands. In areas <strong>of</strong> poor soil<br />

quality (acidic, nutrient poor), acid grasslands may <strong>of</strong>ten conta<strong>in</strong> some heather, or<br />

may be <strong>in</strong>termixed with heather moorland. As with heather, the colour <strong>of</strong> this<br />

1 see http://www.ukbap.org.uk/habitats.aspx<br />

eftec 5 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

habitat changes with season (and with mix <strong>of</strong> species) – <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g and summer green<br />

is predom<strong>in</strong>ant, but <strong>in</strong> autumn and w<strong>in</strong>ter some plants die back to give a ‘white<br />

moor’ appearance. In contrast, calcareous grassland is found on richer soils, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

subdivided <strong>in</strong>to fields and is typically grazed a lot shorter than the poorer quality<br />

acid grassland.<br />

A4. Hay meadows: Typically found on soils that are neither too acidic nor too alkal<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

these grasslands reflect a land use that is much less important than previously. Hay<br />

meadows are periodically cut for a supply <strong>of</strong> hay, but are managed without the<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts associated with improved grassland. This management encourages and<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s high plant diversity, and this is therefore a high conservation value<br />

habitat.<br />

A5. Bracken dom<strong>in</strong>ated: Bracken (Pteridium aquil<strong>in</strong>um) is recognised as a pest species<br />

<strong>in</strong> many open upland habitats, as it is not eaten by livestock and can be hard to<br />

control once established. Spread <strong>of</strong> bracken can be encouraged on moorland by<br />

<strong>in</strong>appropriate management (e.g. burn<strong>in</strong>g), and the historic reduction <strong>in</strong> cattle on the<br />

hill is also thought to have assisted its spread. Bracken also harbours sheep ticks<br />

which spread Lyme disease and loup<strong>in</strong>g ill.<br />

A6. Gorse dom<strong>in</strong>ated: Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is a prickly legum<strong>in</strong>ous shrub with<br />

conspicuous yellow flowers, usually found on lighter (not deep peat) soils on moors<br />

and rough grassy habitats. Like bracken, gorse is considered an <strong>in</strong>vasive species <strong>in</strong>to<br />

some habitats and control is <strong>of</strong>ten attempted by burn<strong>in</strong>g, but it recovers well after<br />

fire. However, gorse can provide a good habitat for nest<strong>in</strong>g birds, and new growth<br />

can be eaten by brows<strong>in</strong>g animals.<br />

A7. Arable/set aside: In the uplands this land use is found only on the flatter/gently<br />

slop<strong>in</strong>g and more fertile areas. Crops may be grown <strong>in</strong> rotation with improved<br />

grassland, sometimes to provide supplementary or w<strong>in</strong>ter feed for livestock. Under<br />

agri-environment schemes, some fields may be left as stubbles or have a reduced<br />

cropp<strong>in</strong>g area due to uncultivated buffer strips, beetle banks or field corners.<br />

A8. Broadleaf and mixed woodland: In upland areas this habitat may consist <strong>of</strong> a mix <strong>of</strong><br />

native species, or be dom<strong>in</strong>ated by one. In different parts <strong>of</strong> the country different<br />

species may dom<strong>in</strong>ate or be <strong>of</strong> higher conservation importance. Broadleaf woodland<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten newly established by plant<strong>in</strong>g young trees (usually with a stake for support<br />

and a plastic tube for protection). The spread <strong>of</strong> established woodland can be<br />

assisted by reduced graz<strong>in</strong>g and ground preparation (e.g. scarification). The most<br />

common species found naturally establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> upland areas is birch (Betula spp).<br />

Note that this habitat category is taken to <strong>in</strong>clude woodland habitats that may<br />

conta<strong>in</strong> native conifers such as yew (Taxus baccata) and juniper (Juniperus<br />

communis).<br />

A9. Coniferous woodland: The species used <strong>in</strong> forestry plantations are usually exotic,<br />

with probably the commonest be<strong>in</strong>g sitka spruce (Picea abies). Although there are<br />

still many rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g examples <strong>of</strong> unsightly rectangular blocks on hillsides, guidel<strong>in</strong>es<br />

now dictate that modern coniferous forestry plantations are planted <strong>in</strong> a more<br />

landscape-friendly fashion. This <strong>in</strong>cludes hav<strong>in</strong>g irregular boundaries, with the sides<br />

<strong>of</strong> watercourses be<strong>in</strong>g left unplanted, and a m<strong>in</strong>imum area <strong>of</strong> native broadleaf trees<br />

also planted, most likely around the outside/lower part <strong>of</strong> the plantation to reduce<br />

visible impact.<br />

A10. Field boundaries: Included <strong>in</strong> this attribute are hedges, stone walls, ditches, banks<br />

and l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> trees, but not modern fences. Field boundaries prevent the passage <strong>of</strong><br />

animals and demarcate fields, as well as be<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>of</strong> the visual landscape. In many<br />

upland areas, field boundaries are made up <strong>of</strong> traditional dry-stone walls. However,<br />

hedges can also be common and these can be a valuable habitat for many species.<br />

Hedges and stone walls are costly to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> and have <strong>of</strong>ten been replaced or<br />

supplemented by modern fences, and there has also been a move towards bigger<br />

field sizes result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> boundaries altogether.<br />

eftec 6 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

A11. Cultural heritage: This attribute may be taken to <strong>in</strong>clude the visual presence <strong>in</strong> the<br />

landscape <strong>of</strong> traditional farm build<strong>in</strong>gs. Less visual aspects may be the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

animals on the hill, traditional breeds, or traditional farm<strong>in</strong>g practices such as<br />

shepherd<strong>in</strong>g with sheep dogs.<br />

A12. Water quantity: This attribute may be taken to mean a range <strong>of</strong> conditions from<br />

drought to excess <strong>of</strong> water lead<strong>in</strong>g to flood<strong>in</strong>g, either <strong>in</strong> upland catchments or<br />

further down the river system. The important parameter <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whether<br />

flood<strong>in</strong>g occurs is not overall precipitation but the frequency and severity <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual precipitation events, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with variables such as soil moisture. It is<br />

thought that such flood<strong>in</strong>g is also exacerbated by lack <strong>of</strong> suitable vegetation <strong>in</strong> the<br />

uplands to slow down the flow <strong>of</strong> water <strong>in</strong>to the rivers.<br />

A13. Water quality: Water quality <strong>in</strong> the uplands is determ<strong>in</strong>ed to a great extent by<br />

agricultural pollution. This pollution, referred to as DWPA (diffuse water pollution<br />

from agriculture) consists <strong>of</strong> nitrogen, phosphorous, organic wastes, pesticides,<br />

veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>es, micro-organisms and silt. The relative contributions <strong>of</strong> these<br />

different pollutants varies by agricultural activity and <strong>in</strong>tensity, and therefore also<br />

by farm type and geographical region.<br />

A14. Greenhouse gas emissions: There are several ma<strong>in</strong> gasses that contribute to the<br />

greenhouse effect, with probably the most important be<strong>in</strong>g carbon dioxide. In order<br />

to summarise the overall effect and make comparisons possible, a given quantity <strong>of</strong><br />

each greenhouse gas is usually converted to a carbon equivalent value which<br />

summarises its ‘global warm<strong>in</strong>g potential’. The habitat or activity <strong>in</strong> question can<br />

either be a greenhouse gas ‘source’ or ‘s<strong>in</strong>k’. In the uplands, certa<strong>in</strong> activities can<br />

be a source (e.g. carbon released by peat erosion, methane from livestock), or can<br />

be a s<strong>in</strong>k (e.g. via good condition ‘active’ bog habitat or through tree growth, both<br />

<strong>of</strong> which sequester carbon).<br />

2.1.2 Estimates <strong>of</strong> current trends<br />

For all habitat type attributes, estimates <strong>of</strong> recent rates <strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong> the extent <strong>of</strong> these<br />

habitats were made. This was done us<strong>in</strong>g the data classified as ‘<strong>Environmental</strong> Zone 3’ from<br />

the Countryside Survey 2000 (CS2000), which is essentially the upland areas <strong>of</strong> England and<br />

Wales. As can be seen <strong>in</strong> Figure 2.1, Zone 3 corresponds very closely with the area <strong>of</strong><br />

England classified as SDA, but with the important addition <strong>of</strong> the uplands <strong>of</strong> Wales. As the<br />

data for England only is not readily available it was decided that the Zone 3 estimates <strong>of</strong><br />

habitat changes were acceptable as a broad-brush representation for the whole country.<br />

For most habitat types the amount <strong>of</strong> habitat loss/ga<strong>in</strong> between 1990 and 1998 (f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

column, Table 2.1) were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the ma<strong>in</strong> report <strong>of</strong> the CS2000 (Ha<strong>in</strong>es-Young et al.,<br />

2000), however for bracken and field boundaries Zone 3 <strong>in</strong>formation was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the<br />

survey website 2 . There are some def<strong>in</strong>ition differences between the habitats as def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><br />

this study, those <strong>in</strong> the CS2000, and those <strong>in</strong> the Land Cover 2000 data set supplied by<br />

<strong>Defra</strong>. Table 2.1 compares these habitat def<strong>in</strong>itions and <strong>in</strong>dicates where habitat types were<br />

amalgamated. For example, ‘Heather Moorland and Bog’ <strong>in</strong> this study corresponds to ‘Dwarf<br />

Shrub Heath’ and ‘Bog’ from CS2000. In this case the areas and changes <strong>in</strong> area were<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ed to calculate a revised s<strong>in</strong>gle percentage change. A similar process was necessary<br />

with the ‘L<strong>in</strong>ear Boundary Features’ <strong>of</strong> CS2000. These data were re-analysed to give a rate<br />

<strong>of</strong> change for all boundary types (walls, hedges, l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> trees/shrubs, bank<strong>in</strong>gs) except<br />

fences.<br />

2 See http://www.cs2000.org.uk/M01_tables/<strong>in</strong>dex.htm<br />

eftec 7 January 2006

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Severely Disadvantaged Areas<br />

A B<br />

Figure 2.1: Map A shows the LFA Severely Disadvantaged Areas <strong>in</strong> England (p<strong>in</strong>k<br />

shad<strong>in</strong>g). Map B shows the area covered by <strong>Environmental</strong> Zone 3, as used by CS2000.<br />

Note that this Zone, whilst substantially correspond<strong>in</strong>g to the SDAs <strong>in</strong> England, also<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes much <strong>of</strong> Wales.<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> Hay Meadow, this attribute is considered a part <strong>of</strong> the Neutral Grassland<br />

CS2000 category, and even though this habitat conta<strong>in</strong>s two sub-habitats (neutral grassland<br />

and herb-rich), neither seemed to correspond closely to Hay Meadow. The change <strong>in</strong> area<br />

figure <strong>of</strong> -15 % quoted is therefore a compromise derived from the data for these two<br />

categories, and reflects an ongo<strong>in</strong>g loss <strong>of</strong> this habitat type. Quantitative estimates <strong>of</strong> rates<br />

<strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong> gorse area over the English SDA are not available. It has therefore been<br />

decided to adopt a current rate <strong>of</strong> change <strong>of</strong> zero, consider<strong>in</strong>g gorse as be<strong>in</strong>g controlled by<br />

brows<strong>in</strong>g animals and other management measures.<br />