The Bilingual Brain: Bilingual Aphasia

The Bilingual Brain: Bilingual Aphasia

The Bilingual Brain: Bilingual Aphasia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Brain</strong> and Language 79, 201–210 (2001)<br />

doi:10.1006/brln.2001.2480, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>: <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Aphasia</strong><br />

Franco Fabbro<br />

IRCCS ‘‘E. Medea’’ and University of Udine, Udine, Italy<br />

Since most people in the world know more than one language, bilingual aphasia is an important<br />

line of research in clinical and theoretical neurolinguistics. From a clinical and ethical<br />

viewpoint, it is no longer acceptable that bilingual aphasics be assessed in only one of the<br />

languages they know. <strong>Bilingual</strong> aphasic patients should receive comparable language tests in<br />

all their languages. In the present work, language recovery of 20 bilingual Friulian–Italian<br />

aphasics was investigated. Thirteen patients (65%) showed a similar impairment in both languages<br />

(parallel recovery), four patients (20%) showed a greater impairment of L2, while three<br />

patients (15%) showed a greater impairment of L1. Despite the many hypotheses advanced to<br />

account for nonparallel recovery, none of them seems to provide satisfactory explanations.<br />

<strong>The</strong> study of bilingual aphasics with parallel impairment of both languages allows us to verify<br />

the hypothesis whereby grammatical disorders in aphasia depend on the specific structure of<br />

each language. As far as rehabilitation programs for multilingual aphasics are concerned, several<br />

questions have been raised, many of which still need a satisfactory answer. © 2001 Academic<br />

Press<br />

Key Words: bilingual aphasia; language assessment; language recovery; language treatment.<br />

Describing <strong>Bilingual</strong>ism<br />

According to current linguistic, psychological, and neurolinguistic approaches, the<br />

term ‘‘bilingual’’ refers to all those people who use two or more languages or dialects<br />

in their everyday lives (Grosjean 1994). In this presentation, dialects are subsumed<br />

under the term ‘‘language.’’ Actually, at the linguistic level no objective criteria to<br />

distinguish between languages and dialects have been proposed so far (Pinker 1994),<br />

and at the neurolinguistic level the question whether the structural distance between<br />

two languages or two dialects or between a language and a dialect may affect their<br />

respective cerebral representation is still under debate (Paradis, 1995).<br />

Several neuropsychological studies suggest that it is not correct to consider bilingual<br />

subjects as ‘‘two monolinguals in one person’’ (Grosjean, 1989). Indeed, bilinguals<br />

do not necessarily need to have a perfect knowledge of all the languages they<br />

know to be considered as such. <strong>The</strong> extremist view of the ‘‘perfect’’ bilingual derives<br />

from a language culture which is essentially monolingual. <strong>Bilingual</strong>s acquire and use<br />

their languages for different purposes, in different domains of life and with different<br />

people. For example, a Canadian born in Quebec may acquire Quebecois as mother<br />

tongue (L1) and use it with his or her family and friends; standard French as a second<br />

language (L2), being the official language of education; and English as a third (L3)<br />

language, the latter not being used everyday but, for example, to write scientific<br />

manuscripts or give lectures at international congresses. Irrespective of the degree<br />

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Franco Fabbro, Neurolinguistic Unit, Scientific Institute<br />

‘‘E.Medea,’’ 33078 San Vito al Tagliamento (PN), Udine, Italy. E-mail: fabbro@sv.Lnf.it.<br />

201<br />

0093-934X/01 $35.00<br />

Copyright © 2001 by Academic Press<br />

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

202 FRANCO FABBRO<br />

of knowledge this person has of these three languages, he or she should definitely<br />

be considered a bilingual.<br />

Given these methodological premises, at present more than half of the world population<br />

is multilingual (Grosjean 1982, 1994). As a direct consequence, multilingual<br />

individuals suffering from developmental or acquired speech or language disorders<br />

do not represent isolated and exceptional cases—as one might be inclined to think<br />

when reading the specialized literature—but rather the majority of clinical cases<br />

(Paradis, 1998a).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Assessment of <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Aphasia</strong><br />

A systematic assessment of all the languages known by an aphasic patient is an<br />

essential prerequisite for both clinical procedures (diagnosis, rehabilitation program,<br />

assessment of progress in recovery, etc.) and neurolinguistic research on multilingualism.<br />

For this reason, Michel Paradis and associates (Paradis & Libben, 1987;<br />

Paradis, 2001a) developed the <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Aphasia</strong> Test (BAT), which consists of three<br />

main parts: part A for the evaluation of the patient’s multilingual history (50 items),<br />

part B for the systematic and comparable assessment of language disorders in each<br />

language known by the subject (472 items in each known language), and part C for<br />

the assessment of translation abilities and interference detection in each language<br />

pair (58 items each). <strong>The</strong> BAT is currently available in 65 languages (part B) and<br />

160 language pairs (part C). Parts B and C of this test have not been simply translated<br />

into different languages, but rather adapted across languages. For example, when<br />

adapting the BAT verbal auditory discrimination test into Friulian, English items<br />

were not simply translated. In fact, for each item the authors had to find four Friulian<br />

words that differed from each other by only one initial phoneme and could also be<br />

easily represented by a picture. Thus, the English stimuli ‘‘mat, cat, bat, hat’’ became<br />

‘‘cjoc, çoc, poc, toc’’ (drunk, log, chicory, piece).<br />

<strong>The</strong> persons administering the test are not required to make any judgment: they<br />

simply write down the answers given by the patient, which will then be processed<br />

by means of a computerized program indicating for each part (B and C) the absolute<br />

number and the percentage of correct answers for each linguistic skill (comprehension,<br />

repetition, judgment, lexical access, propositionizing, reading, and writing) and<br />

for each linguistic level (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, and semantics).<br />

For some parts of the test, such as spontaneous speech, description of a short story<br />

illustrated by pictures, and spontaneous writing, a thorough neurolinguistic analysis<br />

on the basis of strict, objective criteria is required. Assessment of bilingual aphasics<br />

by the BAT provides a quantification and classification of language disorders for<br />

each language, thus allowing a direct comparison of performances in the different<br />

languages known by the patient. Before the BAT, bilingual aphasia was studied using<br />

different test instruments; for this reason it was very hard to compare different studies<br />

(cf. Paradis, 1983, 1993). <strong>The</strong>refore, previous findings should be seen as a useful<br />

starting point for a more thorough and systematic neurolinguistic analysis (Fabbro,<br />

1997).<br />

As pointed out by Grosjean (1989, 1998) and stipulated in the implementation<br />

manual (Paradis & Libben, 1987), when assessing residual language abilities in bilingual<br />

aphasics, a series of methodological precautionary steps should be taken: each<br />

language should be assessed on a separate day and the code-switching habits of the<br />

patient before pathological onset should be thoroughly described, e.g., asking relatives<br />

and friends for relevant information. Indeed, in some bilingual communities<br />

code switching is sociolinguistically accepted and quite common during everyday<br />

conversation (e.g., among English–French bilinguals in Montreal, Canada), whereas

BILINGUAL APHASIA 203<br />

it hardly ever occurs in other bilingual environments (e.g., Friulian–Italian bilinguals<br />

in Friuli, cf. Francescato & Salimbeni, 1976). If the patient exhibits frequent pathological<br />

switching and/or mixing, L1 should be assessed by a person not knowing the<br />

patient’s L2 and, vice versa, L2 should be assessed by someone not knowing L1, so<br />

as to avoid confusing any pathological behavior with deep-rooted habits. On the other<br />

hand, assessment of translation abilities should be made by someone knowing all the<br />

languages at issue.<br />

Clinical Aspects of <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Aphasia</strong><br />

Several clinical studies have shown that bilingual aphasics do not necessarily manifest<br />

the same language disorders with the same degree of severity in both languages.<br />

For this reason, it is no longer ethically acceptable to assess aphasic patients in only<br />

one of their languages (Paradis 1995). In addition, the clinical assessment of both<br />

monolingual and bilingual aphasics should take into account three different phases<br />

in time: (1) the acute phase, which generally lasts 4 weeks after onset; (2) the lesion<br />

phase, which lasts for several weeks and perhaps even up to 4–5 months postonset;<br />

and (3) the late phase, beginning a few months after onset and continuing for the<br />

rest of the patient’s life (Alexander, 1989; Fabbro, 1999a).<br />

During the acute phase a regression of the diaschisis occurs, i.e., a regression of<br />

the functional impairment effects in structurally unaffected cerebral regions of the<br />

ipsilateral and/or contralateral hemisphere which are functionally connected to the<br />

brain area where the damage occurred. <strong>The</strong>se effects were highlighted by tests based<br />

on the quantitative assessment of the regional glucose metabolism by means of positron<br />

emission tomography (Cappa, 1988). During the acute phase, several dynamic<br />

language disorders were observed, such as temporary mutism with preserved comprehension<br />

in both languages (Aglioti & Fabbro, 1993; Fabbro & Paradis, 1995b), severe<br />

word-finding difficulties alternately in one language with concurrent relative fluency<br />

in the other language and good comprehension in both (the so-called alternating antagonism;<br />

cf. Paradis, Goldblum, & Abidi 1982; Nilipour & Ashayeri, 1989), and<br />

severe impairment of the language acquired during childhood with complete preservation<br />

of the one learned at school (‘‘selective aphasia’’; cf. Paradis & Goldblum,<br />

1989). <strong>The</strong> study of these dynamic phenomena is also useful for setting up theoretical<br />

neurofunctional models of brain functioning in multilinguals (Green, 1986; Paradis,<br />

1993a), though it does not allow us to draw unequivocal conclusions about the relationship<br />

between linguistic functions and neuroanatomical structures.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lesion phase is the period of greatest interest for brain–behavior relationships<br />

because during this period language disorders can be more clearly correlated with<br />

the site and extent of the lesion. Since such disorders are also more stable, it is far<br />

more convenient to carry out a complete assessment of the patients’ residual language<br />

abilities in this phase by taking into account all the languages he or she knew before<br />

the insult. Aphasic disorders may or may not vary across languages in one and the<br />

same patient; they may be classified as typical of a single aphasic syndrome, though<br />

with different degrees of symptomatic severity according to the language (Fabbro &<br />

Paradis, 1995b; Yiu & Worral, 1996). On the other hand, the hypothesis of the existence<br />

of a clinical picture of differential aphasia (Albert & Obler, 1978; Silverberg &<br />

Gordon, 1979), namely a type of aphasia in one language (e.g., Wernicke’s aphasia)<br />

and another type (e.g., Broca’s aphasia) in another language, still lacks sufficient<br />

corroborating data (Paradis, 1998b).<br />

In the late phase different patterns of recovery can be observed in multilingual<br />

patients. Sometimes, this phase may hardly differ from the previous one since recovery<br />

or even improvement do not always occur. Language recovery phenomena are

204 FRANCO FABBRO<br />

thought to be due to the ‘‘takeover’’ of linguistic functions by the contralateral hemisphere<br />

or by undamaged areas within the same hemisphere (Bychowsky, 1919/1983;<br />

Cappa, 1998). Improvement in communication skills may probably depend on the<br />

application of explicit compensatory strategies (Paradis, 1994; Paradis & Gopnik,<br />

1997). Recovery, either spontaneous or following rehabilitation, may continue also<br />

during the late phase, though generally less intensively than during the lesion phase.<br />

Patients should be periodically reassessed so as to reexamine recovery patterns and<br />

possibly revise the rehabilitation program. <strong>The</strong> most common patterns of recovery,<br />

described by Pitres (1895) in the first monograph on bilingual aphasia ever published,<br />

are (1) parallel recovery, when both languages are recovered simultaneously;<br />

(2) selective recovery, when only one language slowly comes back and the other is<br />

never recovered; and (3) successive recovery, when one language improves before<br />

the other(s).<br />

Language Recovery in Polyglot Aphasics<br />

When bilinguals or polyglots suffer a brain insult affecting language areas, they<br />

may lose the ability to use all languages they knew and exhibit the same type of<br />

aphasia in all languages. Subsequent recovery may be parallel in all languages. In a<br />

study on the literature of bilingual aphasia published in 1977, Paradis stated that 40%<br />

of the reported cases of polyglot aphasics exhibited parallel recovery of languages.<br />

It should be noted, however, that these statistics are based on clinical case histories<br />

which have been published and, thus, are the most atypical. Paradis put forward the<br />

hypothesis that this type of recovery is even more frequent because descriptions of<br />

single clinical cases of polyglot aphasics with parallel language recovery are very<br />

rare, since neurologists and neuropsychologists tend to describe ‘‘exceptional’’ cases<br />

only, as they can more easily be published (Paradis, 1977). This is one of the reasons<br />

why over 10 years ago Paradis started an international project on bilingual aphasia<br />

in Canada, which is still operative and sees the participation of numerous researchers<br />

from all over the world. This study also includes bilingual aphasic patients with any<br />

type of language disorders so as to have a large number of subjects and, thus, more<br />

reliable statistical data.<br />

In some cases, aphasia affects only one of the languages known by the patient. In<br />

his study of 1895, Pitres was the first to draw attention to the fact that the dissociation<br />

of the languages affected by aphasia was not an exceptional phenomenon, but rather<br />

ordinary. Pitres described seven clinical cases of patients exhibiting differential recovery<br />

of the two languages they spoke. On the basis of the frequency of dissociation,<br />

Pitres put forward hypotheses on the causes that might determine a better recovery<br />

in one language. He suggested that patients tended to recover the language that was<br />

most familiar to them prior to the insult. This hypothesis was subsequently called<br />

Pitres’ rule. In proposing his theory, Pitres referred to a work by Ribot in which it<br />

was claimed that, in the case of memory disorders, the general rule held that the new<br />

deteriorates earlier than the old. Subsequently, numerous neurologists compared and<br />

contrasted the so-called Pitres’ rule (recovery of the most familiar language) with<br />

‘‘Ribot’s law’’ (recovery of the native language), but it should be noted that none of<br />

the two authors ever formulated a ‘‘rule’’ on language recovery in bilingual aphasics.<br />

In his work, Pitres proposed a reasonable explanation of language recovery in<br />

aphasics. He maintained that the recovery pattern could occur only if the lesion had<br />

not destroyed language centers, but only temporarily inhibited them through pathological<br />

inertia. In Pitres’ opinion, the patient generally recovered the most familiar<br />

language because the neural elements subserving it were more firmly associated. If<br />

the patient had become aphasic owing to ‘‘functional inertia’’ of the language areas,

BILINGUAL APHASIA 205<br />

these inhibitory pathological phenomena should have affected to a greater extent the<br />

languages that exhibited weaker associations between the neural elements subserving<br />

them. <strong>The</strong>se hypotheses were both supported and opposed. To date, no unequivocal<br />

evidence supports a rule applicable to all clinical cases.<br />

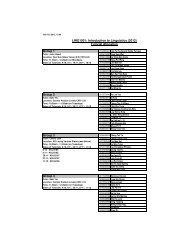

Language Recovery in 20 Friulian–Italian <strong>Bilingual</strong> Aphasics<br />

In recent years I have had the opportunity to assess 20 right-handed bilingual aphasics<br />

using the <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Aphasia</strong> Test—BAT (Paradis and Libben 1987, 1999) in the<br />

two versions of Friulian (Paradis & Fabbro, 1993) and Italian (Paradis & Canzanella,<br />

1989). Table 1 shows patients’ percentages of correct tasks in the BAT linguistic<br />

levels both in L1 and L2. All the patients presented with aphasia following a left<br />

hemisphere lesion. Seventeen patients were native Friulians and three patients were<br />

native Italians (OM, AS, and CM in Table 1). For all patients L2 was learned between<br />

5 and 7 years of age. Before the insult all patients used both languages in their everyday<br />

lives. <strong>The</strong>y could write and read only in Italian.<br />

A battery of standardized neuropsychological tests for the assessment of orientation<br />

in time and space, attention, detection of agnosia, apraxia, verbal and spatial<br />

short-term memory deficits, and verbal long-term memory deficits was administered<br />

to all patients (Spinnler & Tognoni, 1987). Furthermore, patients received a standard<br />

neurologic examination and a neuroimaging study was performed with CT scan or<br />

MRI to define the characteristics of the lesion (site, extent, and type, see Table 1).<br />

Eighteen patients (except for KB and CM) also received the Italian version of the<br />

Aachener Aphasie Test—AAT (Luzzati et al., 1992) to determine the type of aphasia<br />

which had affected each patient (see Table 1).<br />

Thirteen patients (65%) showed a similar impairment in both languages (parallel<br />

recovery) (subjects 1–13, Table 1), four patients (20%) showed a greater impairment<br />

of L2 (subjects 14–17, Table 1), while three patients (15%) showed a greater impairment<br />

of L1 (subjects 18–20, Table 1). <strong>The</strong>se percentages are in line with a recent<br />

review on language recovery in polyglot aphasics (Paradis, 2001b). Several factors<br />

have been proposed to explain parallel language recovery vs differential recovery in<br />

bilinguals. <strong>The</strong> native language, the most familiar to the patient at the time of the<br />

insult, the most socially useful or the most affectively loaded, or, still, the language<br />

of the environment do not recover first or best. Nor does it seem to be a matter of<br />

whether the two languages were acquired and used in the same context as opposed<br />

to different contexts, at different times of development (Paradis 1977, 1998, 2001b).<br />

Still, the type of aphasic syndrome, the type of lesion (tumor, infarction, or cerebral<br />

hemorrhage) or the site of the lesion (cortical vs subcortical, frontal lobe vs temporal<br />

lobe, etc.) do not seem to be directly responsible for parallel language recovery vs<br />

differential recovery. So far, empirical studies have not provided tenable explanations<br />

for the presence of parallel recovery in some bilingual aphasic patients and of differential<br />

recovery in others.<br />

Grammatical Errors in <strong>Bilingual</strong> Aphasic Patients<br />

Grammatical deficits in aphasia are dependent on the way the system can break<br />

down and, therefore, on the structure of the language system. When the system is<br />

placed under stress it can only break down at those junctures allowed by the system<br />

(Paradis, 1988). Given this assumption, if inflectional morphology is vulnerable, a<br />

language with this feature will show outstanding signs of agrammatism (Alajouanine,<br />

1968). Grammatical disorders typical of aphasia are dependent on the structure of<br />

each language. <strong>The</strong>ir various manifestations are only trivially (and predictably) differ-

206 FRANCO FABBRO<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Linguistic Levels (Percentages of Correct Answers)<br />

Morphol-<br />

Phonology ogy Syntax Lexicon Semantics Total<br />

Aphasic<br />

Subjects S A Edu TL Ls Ass Sy L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2<br />

1 (KB) F 15 8 I FT 96 TM 95 95 65 69 88 93 91 95 93 87 86 88<br />

2 (CB) F 71 5 I BG 4 B 81 76 52 43 51 55 61 66 42 55 57 59<br />

3 (EM) M 56 11 H BG 28 B 79 82 13 69 50 56 65 68 47 42 51 63<br />

4 (OR) M 63 5 I BG-I 3 W-B 75 78 43 43 53 50 63 68 50 71 57 62<br />

5 (PB) M 39 18 Tu Th 3 A-B 96 95 91 78 75 77 90 92 82 92 87 86<br />

6 (DC) M 50 13 H BG 1 B 82 85 56 73 58 57 73 68 76 50 69 67<br />

7 (AT) F 77 5 I T 1 B 71 67 26 17 58 50 61 60 53 55 54 50<br />

8 (DD) M 48 13 I FT 3 B 51 62 0 68 66 56 66 72 57 77 47 66<br />

9 (FV) M 67 5 I BG 2 W-A 81 73 52 21 58 59 67 69 60 60 64 56<br />

10 (ATM) M 62 5 I Ins 1 B-A 95 82 78 86 95 90 97 92 96 95 92 89<br />

11 (OM) M 72 8 I T 1 G 76 76 65 65 69 70 74 74 74 74 71 72<br />

12 (AS) M 51 19 I BG 7 B 87 79 78 78 78 71 81 81 77 77 80 77<br />

13 (CM) F 25 13 H PT 13 A 93 100 95 65 89 91 91 87 100 95 94 87<br />

14 (LM) F 67 5 Tu Th 1 TM 95 95 86 56 91 80 93 88 100 82 93 80**<br />

15 (LT) F 54 5 I BG 1 A 89 89 86 65 86 78 89 88 88 73 88 78**<br />

16 (LV) M 54 8 I P 4 G 61 39 56 17 44 39 59 51 62 55 56 40***<br />

17 (AM) M 48 17 H BG-FT 1 G 48 45 13 4 55 51 55 53 53 53 45 41**<br />

18 (RT) M 53 5 I PT 24 TS 67 89 17 17 50 54 67 76 73 87 55 64**<br />

19 (VD) F 78 8 I PT 1 W 59 62 30 60 60 56 68 72 65 77 56 65**<br />

20 (AL) M 77 5 I F 1 G 48 61 0 39 36 38 30 49 12 26 25 42*<br />

Note. S sex; A age; Edu years of education; TL type of lesion (tumor, infarction, hemorrhage); LS lesion site (F: frontal lobe; T: temporal lobe;<br />

P: parietal lobe; BG: basal ganglia; Th: thalamus; Ins: insula); Ass interval between the onset of the lesion and language assessment; Aphasic Syndrome (B:<br />

Broca’s aphasia; W: Wernicke’s aphasia; G: global aphasia; A: anomic aphasia; TM: transcortical motor aphasia; TS: Transcortical Sensory <strong>Aphasia</strong>). Bold entries<br />

are related to the language that showed a significantly better recovery.<br />

* p 0.7.<br />

** p .05.<br />

*** p .01.

BILINGUAL APHASIA 207<br />

ent in different languages. Grammatical disorders observed in aphasics speaking different<br />

languages are such only at the surface level, but their nature seems to have a<br />

universal character and follow the rule whereby aphasia impairs all grammatical aspects<br />

of a language, even if at varying degrees of severity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> study of bilingual aphasics with parallel impairment of both languages allows<br />

us to confirm the hypothesis whereby grammatical disorders in aphasia depend on<br />

the language structure. <strong>The</strong>refore, in ‘‘agrammatic’’ patients who know two morphology-rich<br />

languages such as Friulian and Italian grammatical errors will probably be<br />

similar in both languages and will be different only at the junctures where the two<br />

languages differ. With regard to the first four patients shown in Table 1 the percentage<br />

of morphosyntactic errors in obligatory contexts in L1 and L2 was calculated over<br />

a 5-min spontaneous speech sample (see Table 2). <strong>The</strong>y all presented nonfluent aphasia<br />

with parallel recovery of the two languages. A comparison of errors made by<br />

patients in the two languages revealed that the most significant difference was the<br />

percentage of omissions of obligatory pronouns in Friulian (38.25%) vs Italian<br />

(1.25%). This is probably due to the peculiar grammatical structure of the two languages,<br />

as in Friulian the subject is always accompanied by an obligatory pronoun<br />

(Il frut al bef, literally: <strong>The</strong> boy he drinks), whereas in Italian the subject can be<br />

omitted (‘‘the child drinks’’ or ‘‘drinks’’). <strong>The</strong>refore, in Italian aphasic patients can<br />

TABLE 2<br />

Percentage of Morphosyntactic Errors in Obligatory Contexts<br />

(during a 5-Min Sample of Spontaneous Speech)<br />

1 (KB)<br />

2 (CB) 3 (EM) 4 (OR)<br />

L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2 L1 L2<br />

OFGM<br />

Articles 4 4 7 15 80 29 — 1<br />

Prepositions — — 5 3 16 27 5 5<br />

Conjunctions — — 5 — 4 7 10 —<br />

Obl. Pron. 38 — 43 3 42 — 30 2<br />

Aux. Verbs 15 — 18 10 40 100 26 24<br />

Full Verbs 2 — 3 1 16 25 2 1<br />

SBGM<br />

Verbs 3 1 5 3 — — 3 11<br />

Adjectives — 1 7 2 — — — —<br />

Nouns — — 2 — — 2 — —<br />

SFGM<br />

Articles — 2 — — 30 4 — 3<br />

Prepositions — 4 — — 8 27 1 7<br />

Conjunctions — — — — — — — —<br />

Obl. Pron 1 2 1 — — — — 2<br />

Aux. Verbs — — — — 13 — — —<br />

AGMIC<br />

Articles — 2 3 — — — 3 2<br />

Prepositions — — — 6 — — 3 2<br />

Conjunctions — — — — — — 2 —<br />

Obl. Pron. — 5 — — — — — —<br />

Aux. Verbs — — — — — — — —<br />

Note. OFMG Omission of free grammatical morphemes; SBGM Substitutions<br />

of bound grammatical morphemes; SFGM Substitutions of free<br />

grammatical morphemes; AGMIC Addition of grammatical morphemes<br />

in inappropriate contexts. Bold entries refer to the number of omissions of<br />

bound grammatical morphemes in L1.

208 FRANCO FABBRO<br />

easily avoid structures requiring obligatory pronouns while in Friulian they cannot<br />

(Fabbro & Frau 2001).<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis of morphosyntactic errors made by the first four patients with nonfluent<br />

aphasia confirms the hypothesis that the so-called agrammatism is—as suggested<br />

by Miceli and Mazzucchi (1990)—a theoretical construct and not a natural category.<br />

In both languages these patients made omissions of free-standing grammatical morphemes<br />

and substitutions of bound grammatical morphemes (errors that are reported<br />

to be typical of agrammatism), but also a small percentage of errors came from substitutions<br />

and additions of free grammatical morphemes, which are considered specific<br />

to paragrammatism.<br />

Rehabilitation of <strong>Bilingual</strong> Aphasics<br />

A consistent rehabilitation program for aphasic monolinguals and bilinguals requires<br />

a systematic assessment of language disorders. As far as rehabilitation programs<br />

for multilingual aphasics are concerned, several questions have been raised,<br />

many of which still need a satisfactory answer, namely (1) Is it enough to rehabilitate<br />

one language in bilingual aphasics or do all languages known by the patient have to<br />

be treated? (2) If the decision is taken to rehabilitate one language only, what are<br />

the criteria behind this choice? (3) Does rehabilitation in one language also have<br />

beneficial effects on the untreated languages? (4) Do potentially beneficial effects<br />

transfer to structurally similar languages (Italian and Spanish) only or also to structurally<br />

distant languages (Italian and Japanese)? (Paradis, 1993b).<br />

Unfortunately, research on language rehabilitation in bilingual aphasics is still at<br />

an early stage (cf. Fabbro, 1999b). So far researchers have mainly analyzed individual<br />

cases and, generally, they have not carried out a proper pre- and postrehabilitation<br />

assessment of language disorders. Indeed, very few research studies assessed the<br />

patients’ linguistic abilities before and after rehabilitation with a test equivalent in<br />

both languages. Conclusions drawn from these research studies are thus still speculative,<br />

and further studies are needed if more detailed information is to be acquired.<br />

At present, only one language is generally rehabilitated, especially if the patient<br />

shows mixing or switching phenomena, so as not to confuse the patient and waste<br />

time. Should two languages be simultaneously rehabilitated, sessions would increase<br />

from three to six per week; similarly six languages would require nine sessions, and<br />

so on. With regard to the selection criteria, no clear-cut answers are provided: Some<br />

researchers claim that the mother tongue is preferable, others claim that it is the least<br />

impaired language which should be treated, others, still, claim that the language that<br />

is worst impaired should be targeted.<br />

In the case of the bilingual aphasic patients I observed, selection of the language<br />

to be rehabilitated was based on two parameters: (a) a systematic assessment of the<br />

patient’s linguistic disorders through the BAT in the languages the patient knew and<br />

(b) an interview with the patient and his/her relatives was carried out during which<br />

neurolinguistic data were collected (neurological data, results of the BAT in the languages<br />

known by the patients, etc.) and sociolinguistic issues concerning the patient<br />

and his or her family were discussed (which language they preferred to rehabilitate<br />

both for affective and for business reasons).<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, except for highly complex neurolinguistic situations (for instance, aphasia<br />

with paradoxical recovery of one language), the choice of the language to rehabilitate<br />

depends on the patient and his or her family’s decision, since it was proven that<br />

generally the benefits of rehabilitation in one language tend to extend to the untreated<br />

languages (Fredman, 1975; Junqué, Vendrell, Vendrell-Brucet, & Tobeña, 1989).<br />

This ‘‘mass effect’’ does not seem to be due to the degree of structural similarity

BILINGUAL APHASIA 209<br />

between languages since it is effective not only in the case of structurally similar<br />

languages, but also with structurally different languages (Fabbro, De Luca, & Vorano,<br />

1997).<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Aglioti, S., & Fabbro, F. (1993). Paradoxical selective recovery in a bilingual aphasic following subcortical<br />

lesions. NeuroReport, 4, 1359–1362.<br />

Albert, M. L., & Obler, L. K. (1978). <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bilingual</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>. New York: Academic Press.<br />

Alajouanine, T. (1963). L’aphasie et le langage pathologique. Paris: J. B. Baillère.<br />

Alexander, M. P. (1989). Clinical-anatomical correlations of aphasia following predominantly subcortical<br />

lesions. In F. Boller & J. Grafman (Eds.), Handbook of neuropsychology (Vol. 2, pp. 47–66). Amsterdam:<br />

Elsevier.<br />

Bychowsky, Z. (1919/1983). Concerning the restitution of language loss subsequent to a cranial gunshot<br />

wound in a polyglot aphasic. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Readings on aphasia in bilinguals and polyglots<br />

(pp. 130–144). Montreal: Didier.<br />

Cappa, S. F. (1998). Spontaneous recovery from aphasia. In B. Stemmer & H. A. Whitaker (Eds.),<br />

Handbook of neurolinguistics (pp. 536–547). San Diego: Academic Press.<br />

Chlenov, L. G. (1948/1983). On aphasia in polyglots. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Readings on aphasia in<br />

bilinguals and polyglots (pp. 445–454). Montreal: Didier.<br />

Fabbro, F. (1997). <strong>Bilingual</strong> aphasia research is not a tabula rasa. Aphasiology, 12, 138–141.<br />

Fabbro, F. (1999a). <strong>Aphasia</strong> in multilinguals. In F. Fabbro (Ed.), Concise encyclopedia of language<br />

pathology (pp. 335–340). Oxford: Pergamon Press.<br />

Fabbro, F. (1999b). <strong>The</strong> neurolinguistics of bilingualism. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.<br />

Fabbro, F., De Luca, G., & Vorano, L. (1996). Assessment of language rehabilitation with the BAT in<br />

four multilingual aphasics. Journal of the Israeli Speech, Hearing and Language Association, 19,<br />

46–53.<br />

Fabbro, F., & Frau, G. (2001). Manifestations of aphasia in Friulian. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 14,<br />

255–279.<br />

Fabbro, F., & Paradis, M. (1995). Differential impairments in four multilingual patients with subcortical<br />

lesions. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Aspects of bilingual aphasia (pp. 139–176). Oxford, UK: Pergamon<br />

Press.<br />

Francescato, G., & Salimbeni, F. (1976). Storia, lingua e società in Friuli. Udine: Casamassima.<br />

Fredman, M. (1976). <strong>The</strong> effect of therapy given in Hebrew on the home language of the bilingual or<br />

polyglot adult in Israel. British Journal of Disorders of Communication, 10, 61–69.<br />

Green, D. (1986). Control, activation, and resource: A framework and a model for the control of speech<br />

in bilinguals. <strong>Brain</strong> and Language, 27, 210–223.<br />

Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with two languages. An introduction to bilingualism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard<br />

Univ. Press.<br />

Grosjean, F. (1989). Neurolinguists, beware! <strong>The</strong> bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. <strong>Brain</strong><br />

and Language, 36, 3–15.<br />

Grosjean, F. (1994). Individual bilingualism. In R. E. Asher (Ed.), <strong>The</strong> encyclopaedia of language and<br />

linguistics (pp. 1656–1660). Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.<br />

Grosjean, F. (1998). Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. <strong>Bilingual</strong>ism, Language<br />

and Cognition, 1, 131–149.<br />

Junqué, C., Vendrell, P., & Vendrell, J. (1995). Differential impairments and specific phenomena in 50<br />

Catalan-Spanish bilingual aphasic patients. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Aspects of bilingual aphasia<br />

(pp. 177–210). Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.<br />

Luzzati, C., Willmes, K., & De Bleser, R. (1992). Aachener Aphasie-Test, Versione Italiana. Firenze:<br />

Organizzazioni Speciali.<br />

Nilipour, R., & Ashayeri, H. (1989). Alternating antagonism between two languages with successive<br />

recovery of a third in a trilingual aphasic patient. <strong>Brain</strong> and Language, 36, 23–48.<br />

Ojemann, G. A., & Whitaker, H. A. (1978). <strong>The</strong> bilingual brain. Archives of Neurology, 35, 409–412.<br />

Paradis, M. (1977). <strong>Bilingual</strong>ism and aphasia. In H. Whitaker & H. A. Whitaker (Eds.), Studies in<br />

neurolinguistics (Vol. 3, pp. 65–121). New York: Academic Press.

210 FRANCO FABBRO<br />

Paradis, M. (Ed.) (1983). Readings on aphasia in bilinguals and polyglots. Montreal: Didier.<br />

Paradis, M. (1988). Recent developments in the study of agrammatism: <strong>The</strong>ir import for the assessment<br />

of bilingual aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 3, 127–160.<br />

Paradis, M. (1993a). Linguistic, psycholinguistic, and neurolinguistic aspects of ‘interference’ in bilingual<br />

speakers: <strong>The</strong> activation threshold hypothesis. International Journal of Psycholinguistics, 9,<br />

133–145.<br />

Paradis, M. (1993b). <strong>Bilingual</strong> aphasia rehabilitation. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Foundations of aphasia rehabilitation<br />

(pp. 413–419). Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.<br />

Paradis, M. (1994). Neurolinguistic aspects of implicit and explicit memory: Implications for bilingualism<br />

and SLA. In N. Ellis (Ed.), Implicit and explicit language learning (pp. 393–419). London:<br />

Academic Press.<br />

Paradis, M. (1995). Introduction: <strong>The</strong> need for distinctions. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Aspects of bilingual<br />

aphasia (pp. 1–9). Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.<br />

Paradis, M. (1998). Language and communication in multilinguals. In B. Stemmer & H. A. Whitaker<br />

(Eds.), Handbook of neurolinguistics (pp. 418–431). San Diego: Academic Press.<br />

Paradis, M. (2001a). (in press). Assessing bilingual aphasia. In B. Uzzell & A. Ardila (Eds.), Handbook<br />

of cross-cultural neuropsychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.<br />

Paradis, M. (2001b). <strong>Bilingual</strong> and polyglot aphasia. In R. S. Berndt (Ed.), Handbook of neuropsychology<br />

(2nd ed.) (pp. 69–91). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science.<br />

Paradis, M., & Canzanella, A. (1989). Test per l’afasia in un bilingue, Italian Version. Hillsdale, NJ:<br />

Erlbaum.<br />

Paradis, M., & Fabbro, F. (1993). Test pe afasie in t’un bilenghist, Friulian Version. Hillsdale, NJ:<br />

Erlbaum.<br />

Paradis, M., & Libben, G. (1987). <strong>The</strong> assessment of bilingual aphasia. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.<br />

Paradis, M., & Libben, G. (1999). Valutazione dell’afasia bilingue. Bologna: EMS.<br />

Paradis, M., & Goldblum, M. C. (1989). Selective crossed aphasia in a trilingual aphasic patient followed<br />

by reciprocal antagonism. <strong>Brain</strong> and Language, 36, 62–75.<br />

Paradis, M., Goldblum, M. C., & Abidi, R. (1982). Alternate antagonism with paradoxical translation<br />

behavior in two bilingual aphasic patients. <strong>Brain</strong> and Language, 15, 55–69.<br />

Paradis, M., & Gopnik, M. (1997). Compensatory strategies in genetic dysphasia: Declarative memory.<br />

Journal of Neurolinguistics, 10, 173–186.<br />

Pitres, A. (1895). <strong>Aphasia</strong> in polyglots. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Readings on aphasia in bilinguals and<br />

polyglots (pp. 26–49). Montreal: Didier.<br />

Pinker, S. (1994). <strong>The</strong> language instinct. London: Penguin Books.<br />

Silverberg, R., & Gordon, H. W. (1979). Differential aphasia in two bilingual individuals. Neurology,<br />

29, 51–55.<br />

Spinnler, H., & Tognoni, G. (1987). Standardizzazione e taratura italiana di test neuropsicologici. <strong>The</strong><br />

Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences, Suppl. 8, 5–120.<br />

Yiu, E. M., & Worrall, L. E. (1996). Sentence production ability of a bilingual Cantonese–English<br />

agrammatic speaker. Aphasiology, 10, 505–522.